Abstract

A diet lacking folic acid and choline and low in methionine (folate/methyl deficient diet, FMD diet) fed to rats is known to produce preneoplastic nodules (PNNs) after 36 weeks and hepatocellular carcinomas (tumors) after 54 weeks. FMD diet-induced tumors exhibit global hypomethylation and regional hypermethylation. Restriction landmark genome scanning analysis with methylation-sensitive enzyme NotI (RLGS-M) of genomic DNA isolated from control livers, PNNs and tumor tissues was performed to identify the genes that are differentially methylated or amplified during multistage hepatocarcinogenesis. Out of the 1250 genes analysed, 2 to 5 genes were methylated in the PNNs, whereas 5 to 45 genes were partially or completely methylated in the tumors. This analysis also showed amplification of 3 to 12 genes in the primary tumors. As a first step towards identifying the genes methylated in the PNNs and primary hepatomas, we generated a rat NotI–EcoRV genomic library in the pBluescriptKS vector. Here, we describe identification of one methylated and downregulated gene as the rat protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type O (PTPRO) and one amplified gene as rat C-MYC. Methylation of PTPRO at the NotI site located immediate upstream of the trancription start site in the PNNs and tumors, and amplification of C-MYC gene in the tumors were confirmed by Southern blot analyses. Bisulfite genomic sequencing of the CpG island encompassing exon 1 of the PTPRO gene revealed dense methylation in the PNNs and tumors, whereas it was methylation free in the livers of animals on normal diet. Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) analysis showed significant decrease in the expression of PTPRO in the tumors and in a transplanted rat hepatoma. The expression of PTPRO mRNA in the transplanted hepatoma after demethylation with 5-azacytidine, a potent inhibitor of DNA methyltransferases, further confirmed the role of methylation in PTPRO gene expression. These results demonstrate alteration in methylation profile and expression of specific genes during tumor progression in the livers of rats in response to folate/methyl deficiency, and further implicate the potential role of PTPRO as a novel growth regulatory gene at least in the hepatocellular carcinomas.

Keywords: DNA methylation, DNA amplification, folate deficiency, hepatocellular carcinoma, PTPRO, 5-azacytidine

Introduction

Folic acid has been long known to exhibit the potential to prevent cancer. Epidemiological studies have also linked reduced folate intake to different types of cancer (Choi and Mason, 2000). Previous studies have shown that moderate folate deficiency can promote tumor induction by chemical carcinogens (Cravo et al., 1992; Rogers et al., 1993) or it can act as a complete carcinogen without prior initiation (Duthie, 1999; Van Den Veyver, 2002). Rats are known to be less sensitive to folate deficiency than humans as they can efficiently synthesize methionine from choline due to higher activity of hepatic choline oxidase and betaine–homocysteine methyl transferase (McKeever et al., 1991). The low activity of choline oxidase in humans increases dependence on dietary folate for the synthesis of methionine and for the conversion of folate into metabolically active forms. For these reasons, induction of folate/methyl deficiency in rats requires diets devoid of folate and choline, and low in methionine. It is also well established that this diet deficient in choline and methionine results in the development of hepatocellular carcinomas in rats (Mikol et al., 1983; Ghoshal et al., 1987). This is, therefore, considered an ideal animal model to study multistage hepatocarcinogenesis in that it mimics the metabolic alterations caused by genetic and/or nutritional deficiencies in folate/choline/methionine in humans (Wainfan et al., 1988, 1989; James and Yin, 1989; James et al., 1992; Pogribny et al., 1995, 1997). The advantage of this model is that one can study progressive preneoplastic and neoplastic changes during dietary deficiency in the absence of any exogenous xenobiotic agents. Accordingly, the rat model of folate/methyl deficiency is an ideal system to elucidate the biochemical mechanisms by which nutritional imbalance can lead to human cancers. In this animal model of multistage tumorigenesis, tumor progression occurs slowly and permits tissue sampling during the preneoplastic stage and after tumor development.

Aberrant DNA methylation is a well-known phenomenon in oncogenesis. Decreased genomic methylation (hypomethylation) responsible for activating proto-oncogenes has been observed in a variety of human cancers including cancers of the colon, stomach, uterine cervix, prostrate, thryroid and breast (Choi and Mason, 2000). Alternatively, hypermethylation has been implicated in the transcriptional repression of many tumor suppressor genes. Interestingly, folate/methyl-deficient (FMD) diet can induce regional hypermethylation in a background of genome-wide hypomethylation. Feeding animals with FMD diet has been shown to cause progressive hypomethylation of the p53 coding region followed by increased de novo DNA methyltransferase activity and hypermethylation at selected sites during the later stages of tumorigenesis (Pogribny et al., 1997). We were thus interested in using this animal model to identify genes silenced due to methylation during tumor progression as they could have potential growth suppressive functions.

Several genome-scanning strategies have been successfully used for the identification of cancer genes (Gray and Collins, 2000). Loss of function, as indicative of tumor suppressor genes, or gain of function, as seen in oncogenes, can be assayed by techniques that measure either the copy numbers of a sequence such as cytogenetic techniques using fluorescently labeled probes (Kallioniemi et al., 1992) or high throughput genotyping techniques using microsatellite markers (Canzian et al., 1996). Alternatively, varying transcript levels are detected by array-based assays (Golub et al., 1999) or serial analysis of gene expression, SAGE (Velculescu et al., 1995). These procedures are, either alone or in combination with other approaches, successful in the identification of tumor suppressor genes. The use of methylation as a tag in the search for novel cancer genes has been hampered by the lack of a scanning method that allows the unbiased and reproducible search for changes in DNA methylation patterns. Restriction landmark genome scanning (RLGS) is based on two-dimensional gel electrophoresis that, if used in combination with methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes, allows genome-wide search for methylation changes. RLGS can be applied to any genomic DNA without prior knowledge of sequence data. Cloning of RLGS fragments is achieved through the use of boundary libraries of plasmid clones (Smiraglia et al., 1999). Recently, RLGS was used for the evaluation of aberrant DNA methylation in human malignancies, resulting in the identification of multiple novel target sequences for aberrant methylation. Further, this work demonstrated the existence of non-random patterns of aberrant DNA methylation in human malignancies and identified tumor-type-specific methylation events (Costello et al., 2000). RLGS cannot, however, be efficiently used to study preneoplastic lesions in human malignancies due to the requirement for highly purified, high molecular weight genomic DNA. The development of animal models, in particular rodent models, have, however, allowed the study of early events in tumor development.

We used the FMD rat model of hepatocarcinogenesis in combination with RLGS-M to identify novel cancer genes that become methylated or amplified in the early stages of tumor development. This study led to the identification of protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type O (PTPRO) as a gene silenced in rat hepatocellular carcinomas due to promoter methylation. Protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) are important enzymes involved in the modulation of signal transduction pathways. Although the function of PTPRO is not well studied, it plays a role in terminal differentiation, apoptosis and cell cycle arrest (Seimiya and Tsuruo, 1998; Aguiar et al., 1999), which are some of the hallmarks of a tumor suppressor. We focused the present investigation to the methylation and silencing of PTPRO gene in primary rat hepatomas induced by folate deficiency and in a transplanted rat hepatoma, and its re-activation by a DNA hypomethylating agent.

Results

RLGS-M as a tool to study changes in CpG island methylation

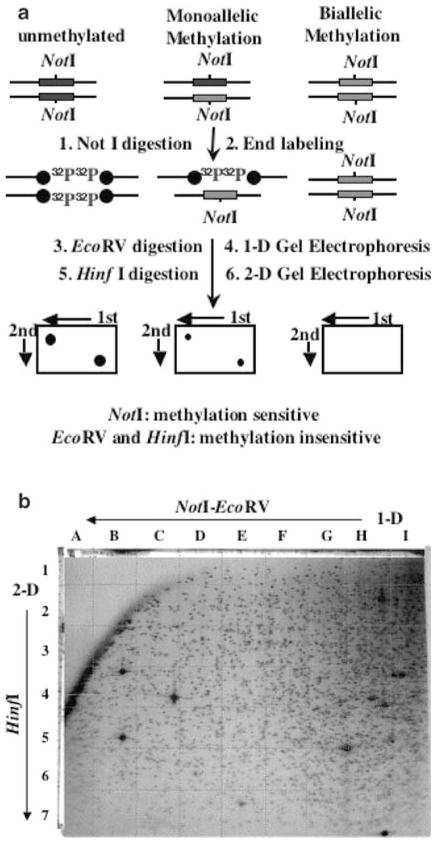

Methylation-sensitive RLGS-M has been used for a decade to study methylation patterns in genomic DNA. NotI sites are located predominantly in the CpG islands and becomes resistant to the enzyme upon methylation of the cytosine within CpG (Hayashizaki et al., 1993). We used this technique to explore genome-wide changes in the methylation profile during folate-induced hepatocarcinogenesis in rats. For this purpose, we digested genomic DNA with NotI that cleaves DNA only if its restriction site is unmethylated, followed by labeling with [γ-32P]ATP at the cleaved end (the restriction landmark). Next, DNA was digested with EcoRV that cleaves DNA frequently to generate smaller DNA fragments that were then separated in the first dimension (Figure 1a). The fractionated DNA was further digested in gel with a third restriction enzyme, HinfI, to obtain even smaller DNA fragments that were subjected to electrophoresis in a second dimension (see Materials and methods for details). The dried gel exposed to X-ray film resulted in numerous 32P-labeled spots, corresponding to distinct genomic DNA fragments generated by NotI digestion. Figure 1b shows a representative RLGS-M profile from rat genomic DNA using NotI, EcoRV and HinfI as restriction enzymes. NotI being a methylation-sensitive enzyme will fail to cleave DNA if that site is methylated, thus resulting in loss of the corresponding RLGS fragment of an unmethylated DNA. Thus, a comparison of spots between normal and tumor samples will be an indication of changes in methylation status.

Figure 1.

RLGS technique. (a) A schematic representation of the RLGS technique. DNA (unmethylated or methylated DNA at one or both alleles) are digested with NotI (cuts only unmethylated DNA) followed by endlabeling with (32P-γ)ATP, EcoRV digestion and separation in agarose tube gel (first dimension). DNA is further digested in gel with HinfI followed by electrophoresis in polyacrylamide slab gel (second deminsion). The dried gel is subjected to autoradiography. (b) Rat master RLGS profile using the NotI–EcoRV–HinfI enzyme combination. Directions for the first dimension and second dimension separations are indicated. The grids dividing the profile into rows (1–7) and columns (A–I) are also shown

RLGS analysis of DNA from the control liver, preneoplastic nodule and the hepatic tumors from rats on FMD diet

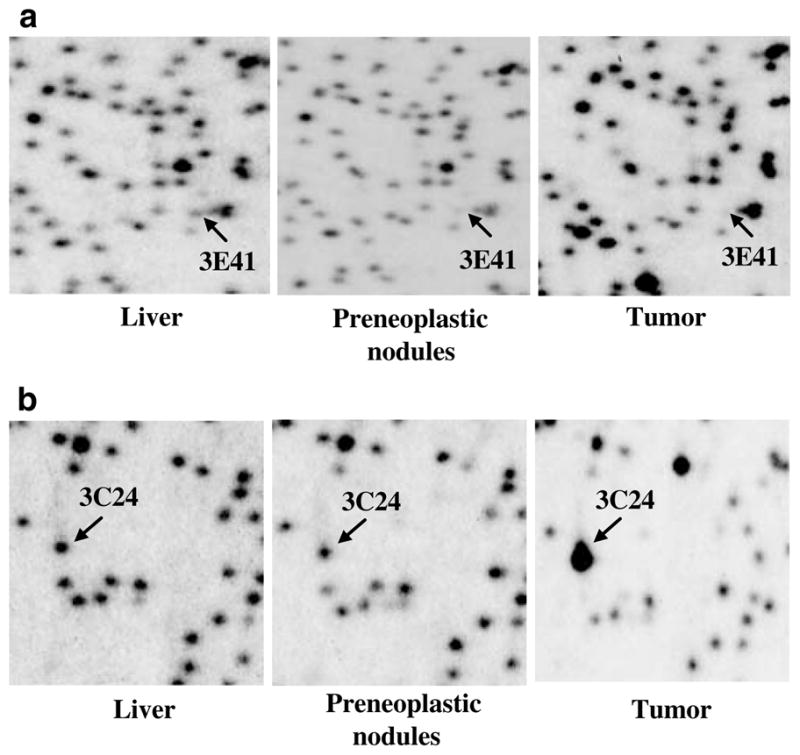

We have used RLGS-M analysis in rat tumors induced by FMD diet containing suboptimal levels of methionine and devoid of choline and folic acid (James and Yin, 1989; James et al., 1992). Rats developed liver tumors with preneoplastic nodules (PNNs) apparent at 36 weeks and primary hepatomas at 54 weeks on FMD diet. Genomic DNA was isolated from the livers of animals on normal diet (36 and 54 weeks), PNNs and tumors, and processed for RLGS analysis. Three normal liver tissues (from age-matched rats on normal diet) were used as controls and compared to three prenoplastic tissues (36 weeks on FMD diet) and four liver tumors (54 weeks FMD diet). Initially, we compared the RLGS gels from three control livers in order to identify polymorphic fragments. Twenty six fragments out of the total 1250 analysed showed variation in intensity among the normal livers. These fragments were excluded from the subsequent analysis. Next, we compared the RLGS-M profiles of PNNs and primary hepatomas to the total number of nonpolymorphic fragments. As shown previously for human malignancies, RLGS-M fragment loss is indicative of DNA hypermethylation (Costello et al., 2000; Dai et al., 2001; Rush et al., 2001, 2002). We analysed 1224 nonpolymorphic RLGS-M fragments in all gels and determined the number of methylated fragments for the preneoplastic and tumor groups (Table 1). We identified a total of 73 fragments that were lost (methylated) and 24 that were enhanced (hypomethylated or amplified) at least in one PNN or tumor. Six of these fragments (2D18, 4D27, 4D34, 3E41, 4E19 and 4E27) were methylated (or partially methylated) in at least one of the PNN profiles. All these fragments were methylated in at least one of the tumor samples. Figures 2a and b show small segments of the RLGS profiles from the normal, PNNs and tumors with arrows depicting examples of RLGS fragments gained or lost. In the present study, we focused on two spots: 3E41 that was lost in all tumors analysed and 3C24 that was amplified in all tumors analysed. Interestingly, 24 new RLGS fragments appeared in the preneoplastic and tumor profiles that could be an indication of hypomethylation of NotI sites that are methylated in the normal tissue.

Table 1.

Number and frequency of lost and enhanced RLGS fragments in PNNs and tumors from rats on FMD diet

| PNNs |

Tumor |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 218L | 217R | 217L | 208R | 203R | 204R | 204L | |

| Methylated fragments | |||||||

| Number | 5 | 2 | 2 | 45 | 5 | 25 | 11 |

| Percent of total fragments analysed | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 3.6 | 0.4 | 2.0 | 0.9 |

| Enhanced fragments | |||||||

| Number | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 12 | 9 |

| Percent of total fragments analysed | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.7 |

Intensity of 1250 spots from each sample (PNNs and tumors) were analysed. Only the spots that were not altered (nonpolymorphic) among the normal livers were considered

Figure 2.

Rat RLGS profiles from normal liver, PNN and tumor. Sections from RLGS profiles derived from control, PNN (36 weeks on FMD diet) and tumor (54 weeks on FMD diet). Chromosomal DNA isolated from the livers of rats on normals diet, livers bearing PNNs and tumors of animals on the deficient diet were subjected to RLGS-M analysis following the protocol described in Figure 1a. (a) Arrows indicate the position of the lost spot (3E41) in the PNN and tumor RLGS-M profile. (b) Arrows indicate RLGS spot (3C24) that was enhanced in the tumor profile

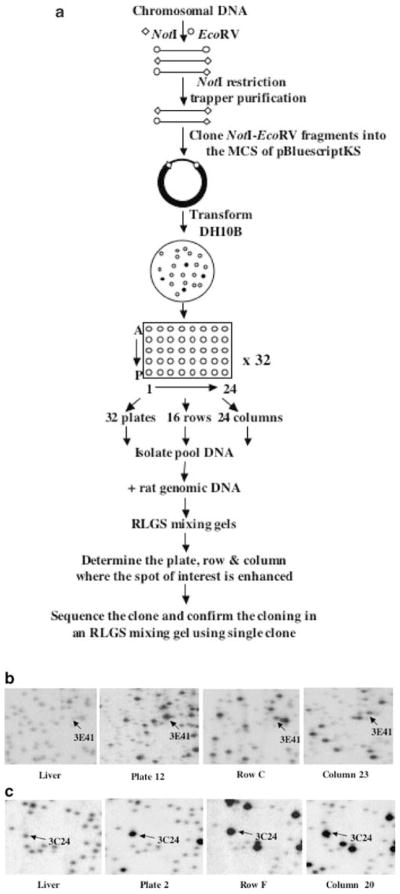

Construction of a NotI–EcoRV boundary library from rat genomic DNA and its use as a tool to clone RLGS fragments

While RLGS-M allows a genome-wide scan without prior knowledge of the sequence, it is necessary to determine the sequence of the methylated or enhanced RLGS fragments for future analysis. To facilitate the cloning, we created a NotI–EcoRV boundary library in a plasmid vector in order to establish a resource that specifically fits the needs of RLGS clone analysis. The construction of the rat library and cloning of the spots are schematically represented in Figure 3a. The starting material for the construction of the NotI–EcoRV boundary library was 500 μg of rat kidney genomic DNA isolated from male rats of three different strains (ACI, Fisher and Sprague–Dawley). This DNA was digested with NotI and EcoRV, and the resulting fragments were used for the NotI restriction trapper purification (Hayashizaki et al., 1992). This purification step greatly reduced the amount of EcoRV–EcoRV fragments and enriched restriction fragments containing a NotI site. As pointed out earlier by Hayashizaki et al. (1992), the selectivity of this procedure is based on the NotI restriction digest to release the NotI–EcoRV fragments from the NotI restriction trapper. The genomic fragments were ligated into the pBluescriptKS vector and cloned in DH10B-competent Escherichia coli. According to blue/white selection, <5% of the clones were non-recombinant. The average insert size in this library is about 3 kb. A total of 15 360 recombinant clones were picked into 40 microtiter plates, each with 384 wells. We selected 32 plates and isolated plasmid DNA from all the 96 clones as a pool from each plate. Next, we cultured clones from each row and column from 32 plates and isolated plasmid DNA as a pool corresponding to each column and row. For each plate, row and column pool, we ran RLGS mixing gels. RLGS mixing gels show the genomic rat RLGS profile in the background and exhibit enhanced signals for RLGS fragments for which a plasmid clone was present in the respective pool. The analysis of these mixing gels allows one to obtain a plate, row and column address for a plasmid clone that represents the RLGS fragment of interest. Figures 3b and c show examples of RLGS mixing gels for RLGS fragments 3E41 and 3C24, respectively.

Figure 3.

Cloning of RLGS spots. (a) Flow chart depicting the steps involved in the generation of a rat methylation (NotI–EcoRV) library, cloning and identification of spots of interest on the RLGS profile. (b) RLGS mixing gels with pooled DNA clones from rat NotI–EcoRV library. The RLGS fragment (3E41) was found in mixing gels from plate 12, row C and column 23. A corresponding section from normal liver is shown for comparison. (c) RLGS mixing gels with pooled DNA clones from a rat NotI–EcoRV library. Enhanced RLGS fragment (3C24) was found in mixing gels from plate 2, row F and column 20. A corresponding section from normal liver is shown for comparison

Cloning of RLGS fragments identifies the rat PVT1 (MYC activator) gene and protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor-type O (PTPRO)

We proceeded to isolate two clones from the NotI–EcoRV library corresponding to RLGS fragments 3E41 and 3C24. A clone corresponding to the RLGS fragment 3E41, which was lost either partially or totally in all PNN and tumor profiles, was found in plate 12, row C and column 23 (see Figure 3b). Sequence analysis identified homology to the rat PTPRO mRNA (Accession no: NM_017336). Similarly, a clone corresponding to the RLGS fragment 3C24, enhanced in all tumor profiles, was found in plate 2, row F and column 20 (Figure 3c). Sequence analysis of 3C24 showed homology to exon 1 of human MYC activator (PVT1) gene (Accession no: HUMPVT1A), which is located about 110 kb downstream of C-MYC.

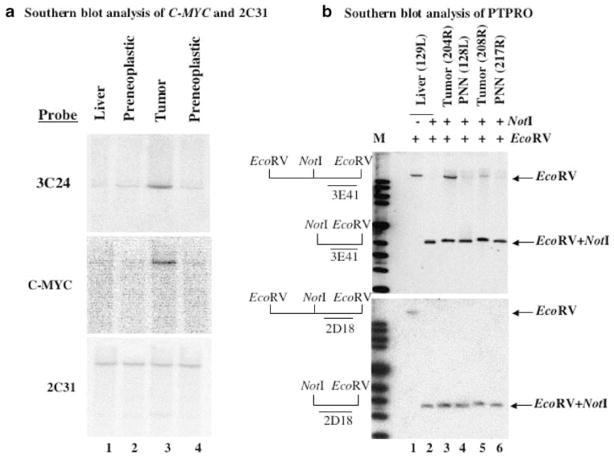

C-MYC is amplified in primary rat hepatomas

Clone 2F20 (PVT1) represented an enhanced RLGS fragment in the rat tumors that could be the result of DNA amplification and copy number gain or of hypomethylation of a usually methylated repeat sequence. Since the identified sequence was located near the known C-MYC proto-oncogene, we tested the hypothesis that rat tumor contains an amplicon spanning C-MYC and PVT1. Genomic DNAs from the normal rat liver, two PNNs and one tumor were digested with EcoRI. Southern blot analysis using the insert sequence of clone 2F20 (PVT1) showed the same band with stronger intensity in the tumor DNA and thus confirmed that the enhancement seen in the RLGS gel was due to DNA amplification and not due to hypomethylation (Figure 4a, top panel). Next, we used a rat C-MYC probe and showed that C-MYC was also amplified in this tumor (Figure 4a, middle panel). Reprobing the blot with the insert of a clone (2C31) that was not amplified in the tumors demonstrated equal loading of DNA in each lane (Figure 4a, bottom panel). Both PVT1 and C-MYC were amplified to a similar degree in all other tumors (203R, 204R, 204L, 208R), suggesting that both sequences are within the same amplicon and that C-MYC was the target gene for amplification. Since C-MYC is a well-characterized oncogene and the purpose of this study was to identify potential tumor suppressor genes silenced due to promoter methylation, we focused on the potential suppression of the PTPRO gene that was found to be methylated by RLGS-M and Southern blot analyses (see below).

Figure 4.

Southern blot analysis of clones corresponding to RLGS fragments 3E41 and 3C24. (a) Southern blot analysis of enhanced RLGS fragment 3C24. EcoRI-digested genomic DNA from normal liver, two preneoplastic lesions and one tumor were hybridized to 32P-labeled random-primed RLGS fragments 3C24, C-MYC and 2C31. (b) Genomic DNA from normal rat liver was digested with EcoRV alone or both NotI and EcoRV and hybridized with inserts from clones 3E41 (upper panel) and 2D18 (lower panel) (lanes 1 and 2). Similarly, genomic DNAs from PNNs and tumors were digested with EcoRV and NotI and hybridized with the same probes (upper and lower panels, lanes 3–6)

PTPRO promoter is methylated in both PNNs and primary hepatomas of rats

As a first step to demonstrate that the loss of 3E41 (PTPRO) in the tumors is indeed due to methylation at the NotI site located in the immediate upstream promoter region, we performed Southern blot analysis of genomic DNAs isolated from the livers of animals on FMD diet for 36 (PNNs) and 54 (tumors) weeks, respectively. Pathological examinations revealed that PNNs and tumors were formed in the livers at 36 and 54 weeks, respectively. The isolated DNA was digested with NotI and EcoRV and probed with 32P-labeled 3E41 insert. The liver DNA cleaved with EcoRV alone generated a high molecular weight fragment (Figure 4b, upper panel, lane 1). Upon digestion with both enzymes, this fragment was completely converted to a low molecular weight DNA fragment indicating that the NotI site, located between two EcoRV sites, was completely unmethylated in the liver (Figure 4b, upper panel, lane 2). In contrast, PNN and tumor DNA isolated from different rats digested with both enzymes showed the existence of the high (methylated) and the low molecular weight (unmethylated) bands on Southern blot analysis (Figure 4b, upper panel, lanes 3–6). The intensity of the upper fragment varied among tumors, indicating variable degree of methylation at the NotI site. As these primary tumors were formed in the livers of animals, we did not expect complete methylation of the NotI site because of their contamination by the surrounding normal tissues. It is well established that only one or a few cells in the population are first transformed, which then divide to propagate to the tumor cells. It is, therefore, likely that a substantial number of cells in the population will have the PTPRO NotI site unmethylated. Only in cell lines and transplanted tumors complete methylation is expected due to clonal expansion of the malignant cells. The higher level of methylation was observed in the tumor (204R) that was robust in size implicating higher number of tumor cells in the population. Occurrence of methylated PTPRO in PNNs demonstrates that PTPRO methylation is an early event in hepatocarcinogenesis induced by FMD diet. To demonstrate complete NotI digestion in the samples and equal DNA loading, the same blot was also probed with a 32P-labeled 2D18 insert whose RLGS fragment intensity was same in control livers and tumors. A single low molecular weight band of equal intensity was obtained after digestion with both EcoRV and NotI (Figure 4b, lower panel, lanes 2–6), demonstrating complete NotI digestion. From these results, it is evident that the loss of spot 3E41 in the tumor was indeed due to methylation at the NotI site located immediately upstream of the transcription start site (Figure 7a) and this event occurred at an early stage of hepatocarcinogenesis.

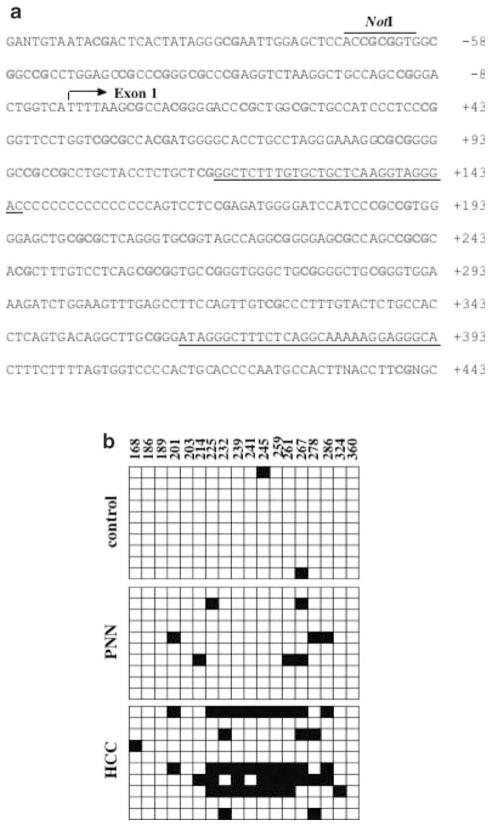

Figure 7.

Bisulfite sequencing of exon 1 of rat PTPRO gene. (a) Nucleotide sequence of 3E41 clone corresponds to the rat PTPRO gene. The NotI site located in the immediate promoter and lost upon methylation in PNN and tumors is indicated. The arrow indicates the transcription start site. The underlined sequence corresponds to the position of the second set of nested PCR primers (rPTP-BS-F2 and rPTP-BS-R2) used to amplify CpG island of PTPRO gene from the bisulfite-converted genomic DNA. (b) Sequence analysis of PTPRO exon 1 methylation. Genomic DNAs from control livers, PNNs and tumors were treated with sodium bisulfite, and the CpG island of rat PTPRO was amplified using nested primers. The PCR products were cloned in TA vector and 10 individual clones were randomly selected for DNA sequence determination. Each row of boxes represents a clone of the particular sample. As indicated in the figure, the sequence included 18 CpGs between +168 and +360 with respect to the transcription start site. The numbers on top represent the positions of CpGs with respect to the transcription start site. The filled and open boxes represent methylated and unmethylated CpGs at a specific position in the particular clone. The numbers above each box denote positions of cytosines with respect to the transcription initiation (+1) site

Reduced expression of PTPRO mRNA in the hepatomas of animals on FMD diet correlates with methylation status of its CpG island

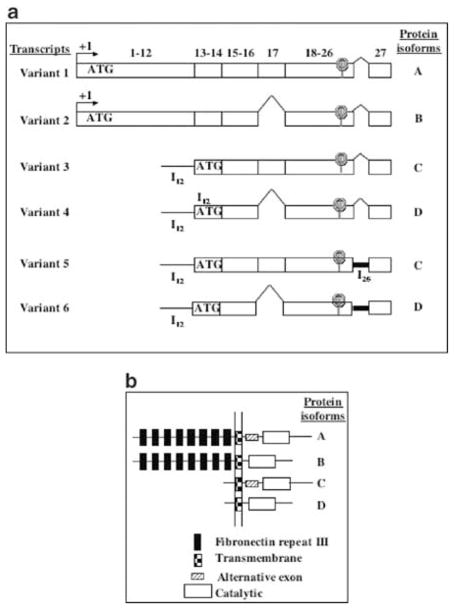

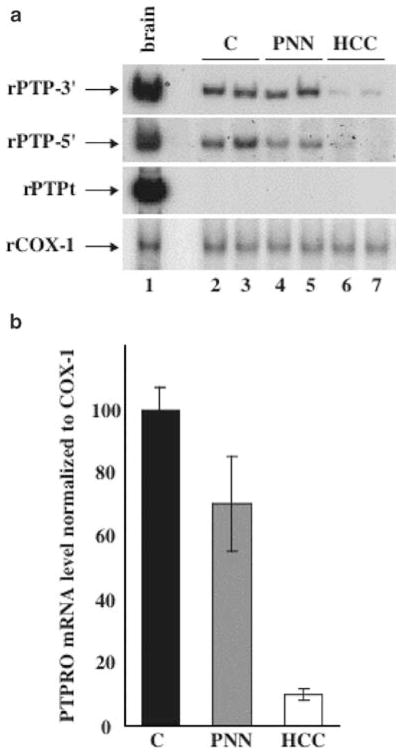

There are two major mRNA variants of human PTPRO identified so far (Figure 5a, variants 1 and 2 vs variants 3, 4, 5 and 6). We will refer to these as PTPRO (full-length) and PTPROt (truncated) variants. The polypeptides encoded by these two transcripts differ exclusively in the length of their N-terminal extracellular domains (Figure 5b, isoforms A and B vs C and D). Some other isoforms of PTPRO might be generated in a tissue-specific manner due to alternative splicing of these two primary transcripts resulting in the long (Figure 5a, variants 1, 3 and 5) or short (variants 2, 4 and 6) isoforms. The full-length transcripts are expressed abundantly in the brain and kidney (Wiggins et al., 1995; Tagawa et al., 1997), whereas the truncated transcripts are highly expressed in the human lymphocytes (Aguiar et al., 1999). Variable levels of PTPRO are expressed in different tissues or cell types (Seimiya et al., 1995; Aguiar et al., 1999). To investigate whether methylation of PTPRO gene correlates with its expression, we isolated RNA from the liver, PNNs and tumors and synthesized cDNA from the RNA samples. An aliquot of the cDNA was subjected to semiquantitative PCR with primers common to all isoforms (rPTP-3′) or specific for the two major isoforms, full-length PTPRO (rPTP-5′) and PTPROt (rPTPt). RNA loading was normalized to cytochrome c oxidase 1 (rCOX-1). Brain, known to express relatively high levels of PTPRO, was used as a positive control (Figure 6a, lane 1). The primers rPTP-5′ and rPTP-3′ both detected expression of PTPRO in the livers and PNNs albeit at a lower level compared to the brain. The expression in the tumors was, however, markedly lower than that in the livers and PNNs (Figure 6a, panels 1 and 2, compare lanes 6 and 7 with lanes 2–5). Very similar levels of COX-1 in each sample showed that the differential expression in the livers and tumors was not due to unequal input of cDNA (Figure 6a, panel 4). Quantitative analyses of the data showed that the expression of PTPRO was reduced by almost 80% in the tumors compared to the control livers and PNNs (Figure 6b). As these are primary tumors, we do not expect complete repression of PTPRO expression due to heterogeneous population of cells (as was obvious from the Southern blot analysis). The third set of primers specific for PTPROt (rPTPt) was designed with the sense primer spanning intron 12 that codes for a unique 5′-untranslated region (the primer was designed based on homology between the unique 5′-UTR of human PTPROt and mouse PTPφ, a mouse homolog of human PTPROt). The specific product for this primer set was amplified in the brain and human B cells (data not shown) but not in livers. RT–PCR with 32P-labeled primers upto 35 cycles and prolonged exposure did not show presence of the rPTPt-specific product in the liver (Figure 6a, panel 3), demonstrating that the liver does not express the truncated form of PTPRO. These results demonstrate that the rat liver indeed expresses PTPRO although at a lower level than the brain and is downregulated during FMD diet-induced hepatocarcinogenesis, which correlated inversely with the methylation status of the NotI site located in the immediate promoter of the gene.

Figure 5.

The different PTPRO variants. (a) Transcript variants of human PTPRO. Schematic representation of the different known isoforms of human PTPRO. The numbers on top represent exons. (b) Four different isozymes of PTPRO are encoded by six different mRNA variants

Figure 6.

RT–PCR analysis of rat PTPRO. (a) Total RNA isolated from control livers, PNNs and tumors as well as from brain was converted to cDNA using random hexamers as primers using RT–PCR kit (Perkin-Elmer). The cDNA was then used for PCR with primers common to all PTPRO isoforms (panel 1, rPTP-3′), specific for full-length PTPRO (panel 2, rPTP-5′), truncated rat PTPRO (panel 3, rPTPt) or rat COX-1 (panel 4, rCOX-1). (b) Quantitative analysis of the rat PTPRO expression in tumors. The 32P-signal in each PCR product obtained with the rPTP-5′ primers was determined from the PhosphorImager analysis (Molecular Dynamics) and quantitated by a volume analysis program (Molecular Dynamics)

Next, we investigated the methylation status of each CpG dinucleotide that spans the exon 1 of PTPRO by bisulfite genomic sequencing. To avoid PCR bias, CpG island of PTPRO was amplified from the bisulfite-converted chromosomal DNA isolated from the liver, PNNs and tumors by nested PCR with gene-specific primers that do not harbor any CpG (Figure 7a). The amplified product was then cloned in a TA vector. A total of 10 randomly selected clones were then subjected to automated sequencing. The results demonstrated that PTPRO exon 1 was essentially methylation-free in the liver, whereas dense methylation was observed in the tumors (Figure 7b). Some of these CpGs were methylated even in the DNA from PNNs implicating that de novo methylation of PTPRO exon1 was an early event in FMD diet-induced hepatocarcinogenesis. The Southern blot analysis (Figure 4b) had also demonstrated that the NotI site located in the immediate upstream promoter of PTPRO was methylated in the PNNs and tumors. We can thus conclude that the gene promoter and exon 1 were partially methylated at least in the PNNs and tumors we analysed. Further, it has been recently demonstrated that exonic CpG islands are more prone to methylation and that methylation may initiate in the exon and then spread to other regions including the promoter (Nguyen et al., 2001).

PTPRO gene is also suppressed in a transplanted rat hepatoma and is induced upon treatment with 5-azacytidine (5-AzaC)

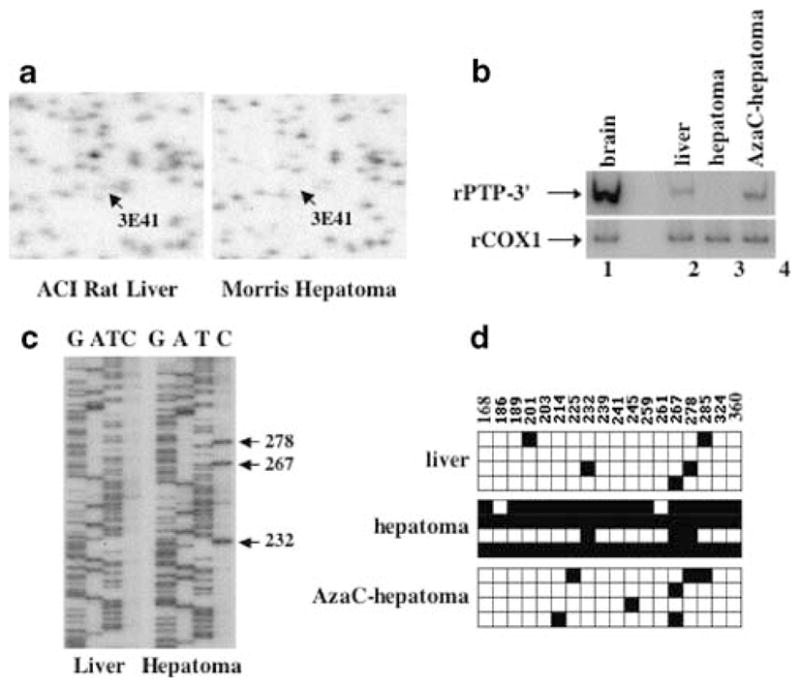

Recent studies in our laboratory have used an animal model to study promoter methylation and silencing of metallothionein-I (MT-I) gene (Ghoshal et al., 2000; Majumder et al., 2002). This model consists of a transplanted rat hepatoma, Morris hepatoma 3924A, which was initially chemically induced with methyl-methane sulfonate and subsequently maintained in our laboratory as a transplant (Duceman et al., 1981; Rose et al., 1981a, b). We next sought to determine whether the PTPRO gene is also methylated and suppressed in this transplanted rat hepatoma induced by a chemical carcinogen compared to the liver of the rat bearing the tumor (host liver). We performed RLGS-M analysis with the NotI enzyme of genomic DNA isolated from the liver and hepatoma of the same animal (Figure 8a). This study revealed that the PTPRO promoter was methylation-free in the livers and was indeed methylated at the NotI site in the transplanted rat hepatoma.

Figure 8.

Induction of PTPRO in Morris hepatoma upon 5-AzaC treatment. (a) RLGS sections from ACI rat liver and Morris hepatoma (transplated into ACI rats) depicting loss of spot corresponding to PTPRO. DNAs isolated from the transplanted hepatomas from the ACI rats and 5-AzaC treated tumor-bearing rats and the host livers were subjected to RLGS-M analysis as described in Figure 1a. (b) Total RNA was isolated from the brain, liver of ACI rats, Morris hepatoma 3924A and 5-AzaC-treated hepatoma and subjected to RT–PCR analysis with primers common to all PTPRO isoforms (rPTP-3′) or rat COX-1. (c) Sequencing of the CpG island of rat PTPRO amplified from bisulfite-treated DNA of the host liver and hepatoma with rPTP-BS-F2 (see Materials and methods). Arrows indicate positions of methylated CpGs in the hepatoma. (d) Bisulfite sequence analysis of PTPRO in the liver of ACI rats, Morris hepatoma 3924A and 5-AzaC-treated hepatoma. CpG island of rat PTPRO was amplified and cloned from liver, hepatoma and 5-AzaC-treated hepatoma as described (see Materials and methods). Four clones selected at random were subjected to automated sequencing. Each row of boxes represents an individual clone from the sample. Filled and open boxes represent methylated and unmethylated CpGs, respectively, within a particular clone. The positions of each cytosine methylated/unmethylated with respect to +1 site are represented above each box

Treatment of the tumor bearing rats with 5-AzaC, a potent inhibitor of DNA methyltransferases, 3 weeks after tumor transplantation resulted in significant regression of the tumor compared to the saline-injected tumors (Majumder et al., 2002). As a first step to determine whether the expression of PTPRO in this transplanted tumor is regulated by methylation, we performed radioactive semi-quantitative RT–PCR analysis of RNA isolated from the liver, Morris hepatoma and 5-AzaC treated hepatoma with primers common to all forms of PTPRO (rPTP-3′). The data showed that expression of PTPRO was repressed in Morris hepatoma and was induced after treatment with 5-AzaC (Figure 8b), suggesting that the gene was methylated in the tumor.

To demonstrate that the silencing of PTPRO in the hepatoma was indeed because of methylation of the CpG island and that its expression only after 5-AzaC treatment was due to demethylation of the promoter, we performed bisulfite genomic sequencing of the DNA isolated from liver, Morris hepatoma and 5-AzaC treated hepatoma. The bisulfite-converted DNA was amplified with nested primers (see Methods and materials). The PCR product was sequenced either directly or after cloning into the TA vector. Four clones were selected at random for automated sequencing. We observed that the PTPRO CpG island located in the exon 1 was methylation-free in the liver, while all the CpG sites within the sequence analysed were methylated in the Morris hepatoma (Figures 8c, d). Upon treatment with 5-AzaC, all sites were either completely or partially demethylated (Figure 8d). Partial demethylation is indicated by a particular site being methylated in one clone and unmethylated in another (Figure 8d, CpG 267 in AzaC-hepatoma). These results combined with RLGS analysis clearly showed that PTPRO promoter and exon 1 were indeed methylated in the transplanted hepatoma and its demethylation resulted in the activation of PTPRO. In contrast to the primary tumors (generated from the propagation of a primary tumor), PTPRO expression was abolished (as it could not be detected by highly sensitive semi-quantitative RT–PCR) and the gene promoter was completely methylated in a transplanted tumor. This is because the hepatoma was transplanted in rats for many generations leading to expansion of highly proliferative tumor cells. Activation of PTPRO after demethylation of its CpG island with 5-AzaC clearly demonstrates the role of DNA methylation in controlling its expression in rat hepatocellular carcinomas.

Discussion

Epidemiological and clinical studies have clearly demonstrated that folate deficiency in humans increases the risk for certain types of cancers, such as colorectal, liver, lung, breast, brain and esophageal cancers (Glynn et al., 1996; Duthie 1999; Van Den Veyver, 2002). Premalignant dysplasia of cervical, bronchial and colonic epithelial cells could be reversed by folate supplementation implying that folate deficiency may have a causal role in the process (Lashner et al., 1989; Rosenberg and Mason, 1989; Butterworth et al., 1991). Elucidation of the molecular mechanisms underlying folate deficiency and predisposition to cancer is, therefore, of critical importance for cancer prevention. It has been shown that FMD diet induces genome-wide hypomethylation as well as increased DNA methyltransferase activity followed by regional CpG island hypermethylation (Pogribny et al., 1995, 1999). The present study was undertaken to explore genome-wide changes in the methylation pattern by RLGS-M analysis and to identify some of the genes that are hypermethylated or hypomethylated/amplified during carcinogenesis in the livers of rats on FMD diet. The present study has shown that methylation is responsible for silencing of PTPRO in rat hepatomas. Bisulfite genomic sequencing revealed that exon 1 of PTPRO was methylated in the tumors and some of these sites were also methylated in PNNs. This is consistent with the finding that methylation of exonic CpG islands generally occurs early in tumorigenesis and subsequently extends to the promoter region (Nguyen et al., 2001). It would be interesting to extend these findings to human hepatocellular carcinomas and determine whether PTPRO is similarly silenced.

Studies performed to date on DNA methylation in vivo focused on this modification after the tumors have already developed. With the FMD diet, tumor progression can be followed stepwise; thus it would be possible to discern how ‘methyl’ deficiency alters methylation status of different genes that may contribute to carcinogenesis. The only information published to date is in regard to alterations in the methylation status of the p53 tumor suppressor gene in response to folate/methyl deficiency (Pogribny et al., 1995, 1997). As more than one tumor suppressor gene containing CpG islands may be methylated in a single tumor (Toyota et al., 1999), it is important to identify the genes that have potential growth inhibitory characteristics at different stages of tumor development. It is logical to assume that the proteins encoded by one or more of these genes are involved in the initiation of tumorigenesis, as the growth regulatory genes were methylated in the preneoplastic stage. RLGS analysis revealed that de novo DNA methylation occurs early during the preneoplastic stage and extends to additional genes during tumor progression.

Although it has been reported that C-MYC expression is upregulated at an early stage in the livers of rats on FMD diet (Wainfan and Poirier, 1992), the mechanism has not been explored. To our knowledge, this is the first report that C-MYC gene is amplified in this rat model of FMD diet-induced hepatocarcinogenesis. Likewise, C-MYC amplification and overexpression in rat hepatomas has been reported earlier (Hayashi et al., 1984; Suchy et al., 1989). Gene amplification induced by folate deficiency has also been previously reported in an in vitro model (Melnyk et al., 1999). Global hypomethylation in centromeric repeat sequences of ICF syndrome patients, as a consequence of mutations in DNMT3B, is involved in genomic instability (Hansen et al., 1999; Xu et al., 1999). It is, therefore, conceivable that in addition to regional hypermethylation of a few genes, a methyl-deficient diet could also cause hypomethylation of certain sequences that leads to rearrangements of chromosomal segments, chromosomal instability and DNA amplification.

The reversible phosphorylation on tyrosine residues is an extremely rapid and significant post-translational modification of proteins that is used in signaling pathways for the regulation of cell growth and differentiation. PTPs exert both positive and negative effects on signaling pathways and play crucial physiological roles in a variety of mammalian tissues and cells. The protein tyrosine phosphatase PRL-3 gene is highly upregulated in metastatic colorectal cancers (Saha et al., 2001). Overexpression of PRL-3 has been found to enhance growth of human embryonic kidney fibroblasts (Matter et al., 2001) and overexpression of PRL-1 or PRL-2, close relatives of PRL-3, can transform mouse fibroblasts and hamster pancreatic epithelial cells in culture and promote tumor growth in nude mice (Diamond et al., 1994; Cates et al., 1996). In contrast, overexpression of LAR (a transmembrane receptor-like protein tyrosine phosphatase) in cultured mammalian cells did not affect cell adhesion; rather, it induced caspase-dependent apoptosis (Weng et al., 1998). In addition, several protein kinases including tyrosine kinases are established oncogenes (Chen et al., 2002). It is, therefore, conceivable that phosphatases, which can alter the function of kinases and also revert their action, may function as tumor suppressors. Interestingly, PTEN, a mixed function phosphatase has been characterized as a tumor suppressor (Dahia, 2000) and recently rPTPη (rat homolog of human DEP-1), a receptor type PTP, has been demonstrated to be a tumor suppressor (Trapasso et al., 2000). It is noteworthy that expression of the PTPRO variant, PTP-U2 (full length), is augmented during phorbol ester-induced differentiation of monoblastic leukemia (U937) cells and its ectopic expression results in apoptosis after terminal differentiation that requires phosphatase activity (Seimiya and Tsuruo, 1998). Similarly, overexpression of the smaller isoform, PTPROt, expressed abundantly in naïve B lymphocytes but downregulated in B-cell lymphomas results in cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 phase (Aguiar et al., 1999). These observations coupled with the present data prompted us to postulate that silencing of PTPRO in the liver can facilitate tumor promotion either by relaxing cell cycle arrest, preventing contact inhibition or developing resistance to apoptosis, all of which are hallmarks of cancer cells. In addition to these characteristics of PTPRO that are typical of tumor suppressors, the suppression of its expression by promoter methylation is consistent with that reported for established tumor suppressors (Cheng et al., 2001; Hirao et al., 2002; Roman-Gomez et al., 2002; Watanabe et al., 2001).

There are several reports on the loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in the region of 12p12–13 in different human cancers (Kibel et al., 2000; Wilkens et al., 2000; Sanchez-Cespedes et al., 2001). The p27/KIP1 gene, which is localized in this region was thought to be the target of these 12p12–13 alterations. Analysis of this gene in tumors did not, however, show any alterations (Cave et al., 1995; Takeuchi et al., 1996). Interestingly, human PTPRO is located in chromosome 12, specifically to the region 12p12.3, which makes PTPRO an important candidate for a tumor suppressor gene. We have not demonstrated unequivocally that PTPRO is a tumor suppressor by growth retardation of cells overexpressing PTPRO or by a nude mice model, which is beyond the scope of the present study. The focus of this extensive investigation was to show that the PTPRO gene was suppressed by promoter methylation and was re-activated by a DNA hypomethylating agent in rat hepatomas relative to the liver. Further, this is the first demonstration that this gene is suppressed at the early stages of tumorigenesis, particularly in response to simple dietary manipulations. The present study also revealed altered methylation patterns of several other genes. The identity of these genes and their potential role in carcinogenesis will be the first step to unravel the signaling pathway of nutrient–gene interaction.

Materials and methods

Animals and diets

Male weaning F344 rats were housed (two/cage) in temperature-controlled (24°C) room with a 12 h/light/dark cycle, and provided free access to water and NIH-31-pelleted diet. The dietary regimen was followed as described earlier (James and Yin, 1989; James et al., 1992). Care and provision of experimental animals were provided by NCTR (Division of Veterinary Services). Cage changes and diet administration were provided by trained personnel through an NCTR contract with Bionetics, Inc. Semipurified diets were obtained in pellet form from Dyets, Inc. (Bethlehem, PA, USA). When the animals reached 50 g of body weight (approximately 4 weeks of age), the animals were divided into two groups. The rats were randomly assigned either to the methionine–choline–folate-deficient diet (6% casein and 6% gelatin without supplemental methionine, choline or folate) or to the control diet that was identical to the deficient diet but supplemented with 4 g of L-methionine, 3mg of folic acid and 4.2 g of choline per kilogram of diet. It has been shown that folate deficiency in addition to choline deprivation and low methionine levels increases the severity of methyl-group deficiency in the semipurified diet formulation (Roman-Gomez et al., 2002). PNNs are formed within 36 weeks and hepatocellular carcinoma formed within 54 weeks of initiation of methyl-deficient diet. DNA and RNA were isolated from the livers containing PNNs as well as tumors.

RLGS

Genomic DNA was isolated from control, preneoplastic and hepatoma tissues and subjected to RLGS analysis following the protocol of Okazaki et al. (1995). Briefly, 5–10 μg high molecular weight genomic DNA was incubated in the presence of DNA polymerase (0.5 U), ddTTP, ddATP, dCTPαS and dGTPαS to fill in randomly broken ends. Next, the DNA was digested with 20U of NotI (New England Biolabs), endlabeled with [α-32P]dGTP and [α-32P]dCTP using Sequenase (1.3U) and subsequently digested with EcoRV that cleaves DNA more frequently. The restriction sites of NotI are predominantly located in the CpG islands and it cleaves only unmethylated DNA, whereas EcoRV cuts DNA irrespective of its methylation status. A total of 1.5 μg labeled DNA was separated by size in a 0.8% agarose gel. A third digestion with 750U HinfI was performed in gel to fragment the DNA further. The first dimension gel was connected to a 5% acrylamide gel and the DNA fragments separated in a second dimension. The gel was dried and exposed to X-ray film and analysed.

Analysis of RLGS gel

Rat genomic DNA was used to create a rat master RLGS profile. This RLGS profile was divided into seven rows (1–7) and nine columns (A–I) dividing the whole RLGS profile into evenly sized sections (Figure 1b). Within each section, RLGS fragments were numbered consecutively to enable each RLGS fragment in the profile to be identified by the section name and fragment number. Initially, the RLGS profiles derived from the three control livers were compared to each other to identify the polymorphic RLGS fragments in rat DNA and to eliminate these from the final analysis. The RLGS gels of the PNNs and the tumor samples were then compared with one of the controls to identify fragments that were lower (loss) or higher (gain) in intensity when compared with the control.

Southern blot analysis

Genomic DNA digested with either NotI, EcoRV or both was separated on a 0.8% agarose gel, transferred to a Zetaprobe (BioRad) membrane and hybridized to 32P-labeled DNA probes. The washed membrane was subjected to autoradiography as well as phosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics) analysis.

Bisulfite genomic sequencing

Preparation of genomic DNA, treatment with sodium bisulfite and amplification of the rat PTPRO gene were performed according to the protocol optimized in our lab (Ghoshal et al., 2000; Majumder et al., 1999a, b). The nested primers used for the amplification of the rat PTPRO gene are the following:

rPTP-BS-F1: ATGGGGTATTTGTTTAGGGAAAGG

rPTP-BS-R1:TTCCTTATTCAATAAAACCCTTTCCCT

rPTP-BS-F2: GGTTTTTTGTGTTGTTTAAGGTAGGGAT

rPTP-BS-R2: TACCCTCCTTATTACCTAAAAAAACCCTAT.

The PCR reaction mix contained PCR buffer (Qiagen), 0.2mM dNTP (Boehringer Mannheim), 25 pmol of each primer and Taq DNA polymerase (Qiagen). The cycling conditions were as follows: 35 cycles of 1 min each at 94, 55, and 68°C (ramp 3 min) and a final extension at 68°C for 7 min. The amplified DNA was digested with ApoI to check complete conversion of unmethylated cytosines to uracils. The amplified DNA was either sequenced with fmol DNA Sequencing System (Promega) or cloned into TA vector using the TA cloning kit (Invitrogen). Clones were selected at random for automated sequencing.

RT–PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the guanidinium isothiocyanate–acid phenol method (Chomczynski and Sacchi, 1987). Reverse transcription was carried out with random hexamers and M-MuLV reverse transcriptase from 2 μg of total RNA following the protocol provided in the GeneAmp RNA PCR kit (Perkin-Elmer). One-tenth of the RT reaction was subsequently used for radioactive semi-quantitative PCR for each of the genes of interest. The reaction mix contained PCR buffer, 1.5mM MgCl2, 0.2mM dNTP, 2 pmol of 32P-labeled primers and Taq polymerase. The cycling conditions were as follows: 30 s each at 94, 54.6 (i) or 51.5°C (ii, iii and iv), and 72°C for 25 cycles. The PCR products were seperated on a native polyacrylamide gel (6% acrylamide) and identified by autoradiography. 32P-signal obtained by PhosphorImager analysis was quantitated using Imagequant program (Molecular Dynamics). The gene-specific primers used for amplification of the respective cDNA are as follows:

-

rPTP-5′: F-5′-GGCGTGGTACTACAACTTTC-3′

R-5′-GACCATCCAGTGTAGCATTCTCG-3′

-

rPTP-3′: F-5′-TAAAGAAGAGGAAACTGACG-3′

R-5′-GTCCCTGGGTGGCAATGTAC-3′

-

rPTPt: F-5′-ATGATTCAAAGGCAATATAAA-3′

R-5′-AAGGATGCAAAATTGACAAA-3′

-

rCOX-1: F-5′-CCCCCTGCTATAACCCAATATCAG-3′

R-5′-TCCCTCCATGTAGTGTGTGTAGCGAGTCAG-3′.

Maintenance of Morris hepatoma in rats and 5-AzaC treatment

Morris hepatoma 3924A was grown in ACI rats by transplanting a 0.5 × 2–3mm slice of the solid tumor into their hind leg, as described previously (Ghoshal et al., 2000). For 5-AzaC treatment, rats were injected i.p. with the drug (5 mg/kg body weight) dissolved in physiological saline or with saline alone (control). The animals were killed when the control tumor grew to 15–20 g size (4–6 weeks). Tumor growth was significantly reduced in 5-AzaC treated rats.

Acknowledgments

Tasneem Motiwala and Kalpana Ghoshal contributed equally to this work. The present study was supported, in part, by the Grants ES10874 and CA86978 (STJ).

Abbreviations

- FMD diet

folate/methyl-deficient diet

- PNN

preneoplastic nodule

- RLGS-M

restriction landmark genome scanning with methylation-sensitive enzymes

- PTPRO

protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type O

- 5-AzaC

5-azacytidine

- RT–PCR

reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction

References

- Aguiar RC, Yakushijin Y, Kharbanda S, Tiwari S, Freeman GJ, Shipp MA. Blood. 1999;94:2403–2413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth C, Hatch KD, Gore H, Meuller H, Krumdieck CL. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;94:2. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/35.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canzian F, Salovaara R, Hemminki A, Kristo P, Chadwick RB, Aaltonen LA, de la Chapelle A. Cancer Res. 1996;56:3331–3337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cates CA, Michael RL, Stayrook KR, Harvey KA, Burke YD, Randall SK, Crowell PL, Crowell DN. Cancer Lett. 1996;110:49–55. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(96)04459-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cave H, Gerard B, Martin E, Guidal C, Devaux I, Weissenbach J, Elion J, Vilmer E, Grandchamp B. Blood. 1995;86:3869–3875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YQ, Zhou YQ, Fu LH, Wang D, Wang MH. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:1811–1819. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.11.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng CW, Wu PE, Yu JC, Huang CS, Yue CT, Wu CW, Shen CY. Oncogene. 2001;20:3814–3823. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SW, Mason JB. J Nutr. 2000;130:129–132. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.2.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello JF, Fruhwald MC, Smiraglia DJ, Rush LJ, Robertson GP, Gao X, Wright FA, Feramisco JD, Peltomaki P, Lang JC, Schuller DE, Yu L, Bloomfield CD, Caligiuri MA, Yates A, Nishikawa R, Su Huang H, Petrelli NJ, Zhang X, O’Dorisio MS, Held WA, Cavenee WK, Plass C. Nat Genet. 2000;24:132–138. doi: 10.1038/72785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cravo ML, Mason JB, Dayal Y, Hutchinson M, Smith D, Selhub J, Rosenberg IH. Cancer Res. 1992;52:5002–5006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahia PL. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2000;7:115–129. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0070115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Z, Lakshmanan RR, Zhu WG, Smiraglia DJ, Rush LJ, Fruhwald MC, Brena RM, Li B, Wright FA, Ross P, Otterson GA, Plass C. Neoplasia. 2001;3:314–323. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond RH, Cressman DE, Laz TM, Abrams CS, Taub R. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:3752–3762. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.6.3752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duceman BW, Rose KM, Jacob ST. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:10755–10758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duthie SJ. Br Med Bull. 1999;55:578–592. doi: 10.1258/0007142991902646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoshal AK, Rushmore TH, Farber E. Cancer Lett. 1987;36:289–296. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(87)90022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoshal K, Majumder S, Li Z, Dong X, Jacob ST. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:539–547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn SA, Albanes D, Pietinen P, Brown CC, Rautalahti M, Tangrea JA, Taylor PR, Virtamo J. Cancer Causes Control. 1996;7:214–223. doi: 10.1007/BF00051297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub TR, Slonim DK, Tamayo P, Huard C, Gaasenbeek M, Mesirov JP, Coller H, Loh ML, Downing JR, Caligiuri MA, Bloomfield CD, Lander ES. Science. 1999;286:531–537. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JW, Collins C. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:443–452. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.3.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen RS, Wijmenga C, Luo P, Stanek AM, Canfield TK, Weemaes CM, Gartler SM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14412–14417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K, Makino R, Sugimura T. Gann. 1984;75:475–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashizaki Y, Hirotsune S, Hatada I, Tamatsukuri S, Miyamoto C, Furuichi Y, Mukai T. Genomics. 1992;14:733–739. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(05)80176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashizaki Y, Hirotsune S, Okazaki Y, Hatada I, Shibata H, Kawai J, Hirose K, Watanabe S, Fushiki S, Wada S, Sugimoto T, Kobayakawa K, Kawara T, Katsuki M, Shibuya T, Mukai T. Electrophoresis. 1993;14:251–258. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150140145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirao T, Bueno R, Chen CJ, Gordon GJ, Heilig E, Kelsey KT. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:1127–1130. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.7.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James SJ, Cross DR, Miller BJ. Carcinogenesis. 1992;13:2471–2474. doi: 10.1093/carcin/13.12.2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James SJ, Yin L. Carcinogenesis. 1989;10:1209–1214. doi: 10.1093/carcin/10.7.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallioniemi A, Kallioniemi OP, Sudar D, Rutovitz D, Gray JW, Waldman F, Pinkel D. Science. 1992;258:818–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1359641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kibel AS, Faith DA, Bova GS, Isaacs WB. J Urol. 2000;164:192–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lashner BA, Heidenreich PA, Su GL, Kane SV, Hanauer SB. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:255–259. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)90058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumder S, Ghoshal K, Datta J, Bai S, Dong X, Quan N, Plass C, Jacob ST. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:16048–16058. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111662200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Majumder S, Ghoshal K, Li Z, Bo Y, Jacob ST. Oncogene. 1999a;18:6287–6295. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumder S, Ghoshal K, Li Zand Jacob ST. J Biol Chem. 1999b;274:28584–28589. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matter WF, Estridge T, Zhang C, Belagaje R, Stancato L, Dixon J, Johnson B, Bloem L, Pickard T, Donaghue M, Acton S, Jeyaseelan R, Kadambi V, Vlahos CJ. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;283:1061–1068. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeever MP, Weir DG, Molloy A, Scott JM. Clin Sci (Colch) 1991;81:551–556. doi: 10.1042/cs0810551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnyk S, Pogribna M, Miller BJ, Basnakian AG, Pogribny IP, James SJ. Cancer Lett. 1999;146:35–44. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(99)00213-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikol YB, Hoover KL, Creasia D, Poirier LA. Carcinogenesis. 1983;4:1619–1629. doi: 10.1093/carcin/4.12.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen C, Liang G, Nguyen TT, Tsao-Wei D, Groshen S, Lubbert M, Zhou JH, Benedict WF, Jones PA. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1465–1472. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.19.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki Y, Okuizumi H, Sasaki N, Ohsumi T, Kuromitsu J, Hirota N, Muramatsu M, Hayashizaki Y. Electrophoresis. 1995;16:197–202. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150160134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogribny I, Yi P, James SJ. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;262:624–628. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogribny IP, Basnakian AG, Miller BJ, Lopatina NG, Poirier LA, James SJ. Cancer Res. 1995;55:1894–1901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogribny IP, Miller BJ, James SJ. Cancer Lett. 1997;115:31–38. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)04708-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers AE, Zeisel SH, Groopman J. Carcinogenesis. 1993;14:2205–2217. doi: 10.1093/carcin/14.11.2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman-Gomez J, Castillejo JA, Jimenez A, Gonzalez MG, Moreno F, Rodriguez Mdel C, Barrios M, Maldonado J, Torres A. Blood. 2002;99:2291–2296. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.7.2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose KM, Bell LE, Siefken DA, Jacob ST. J Biol Chem. 1981a;256:7468–7477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose KM, Stetler DA, Jacob ST. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981b;78:2833–2837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.5.2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg IH, Mason JB. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:502–503. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)90091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush J, Heinonen K, Mrozek K, Wolf BJ, Abdel-Rahman M, Szymanska J, Peltomaki P, Kapadia F, Bloomfield CD, Caligiuri MA, Plass C. Blood. 2002;99:1874–1876. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.5.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush LJ, Dai Z, Smiraglia DJ, Gao X, Wright FA, Fruhwald M, Costello JF, Held WA, Yu L, Krahe R, Kolitz JE, Bloomfield CD, Caligiuri MA, Plass C. Blood. 2001;97:3226–3233. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.3226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S, Bardelli A, Buckhaults P, Velculescu VE, Rago C, St Croix B, Romans KE, Choti MA, Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Science. 2001;294:1343–1346. doi: 10.1126/science.1065817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Cespedes M, Ahrendt SA, Piantadosi S, Rosell R, Monzo M, Wu L, Westra WH, Yang SC, Jen J, Sidransky D. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1309–1313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seimiya H, Sawabe T, Inazawa J, Tsuruo T. Oncogene. 1995;10:1731–1738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seimiya H, Tsuruo T. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21187–21193. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.21187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smiraglia DJ, Fruhwald MC, Costello JF, McCormick SP, Dai Z, Peltomaki P, O’Dorisio MS, Cavenee WK, Plass C. Genomics. 1999;58:254–262. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchy BK, Sarafoff M, Kerler R, Rabes HM. Cancer Res. 1989;49:6781–6787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagawa M, Shirasawa T, Yahagi Y, Tomoda T, Kuroyanagi H, Fujimura S, Sakiyama S, Maruyama N. Biochem J. 1997;321:865–871. doi: 10.1042/bj3210865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi S, Mori N, Koike M, Slater J, Park S, Miller CW, Miyoshi I, Koeffler HP. Cancer Res. 1996;56:738–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyota M, Ahuja N, Ohe-Toyota M, Herman JG, Baylin SB, Issa JP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8681–8686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapasso F, Iuliano R, Boccia A, Stella A, Visconti R, Bruni P, Baldassarre G, Santoro M, Viglietto G, Fusco A. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:9236–9246. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.24.9236-9246.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Van Den Veyver IB. Annu Rev Nutr. 2002;22:255–282. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.010402.102932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velculescu VE, Zhang L, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Science. 1995;270:484–487. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wainfan E, Dizik M, Stender M, Christman JK. Cancer Res. 1989;49:4094–4097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wainfan E, Kilkenny M, Dizik M. Carcinogenesis. 1988;9:861–863. doi: 10.1093/carcin/9.5.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wainfan E, Poirier LA. Cancer Res. 1992;52:2071s–2077s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Nakamura M, Yonekawa Y, Kleihues P, Ohgaki H. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2001;101:185–189. doi: 10.1007/s004010000343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng LP, Yuan J, Yu Q. Curr Biol. 1998;8:247–256. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70106-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins RC, Wiggins JE, Goyal M, Wharram BL, Thomas PE. Genomics. 1995;27:174–181. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkens L, Bredt M, Flemming P, Kubicka S, Klempnauer J, Kreipe H. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;114:867–874. doi: 10.1309/BMTT-JBPD-D13H-1UVD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu GL, Bestor TH, Bourc’his D, Hsieh CL, Tommerup N, Bugge M, Hulten M, Qu X, Russo JJ, Viegas-Pequignot E. Nature. 1999;402:187–191. doi: 10.1038/46052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]