Abstract

Purpose

Hand-foot syndrome (HFS) is a dose-limiting toxicity of capecitabine for which no effective preventative treatment has been definitively demonstrated. This trial was conducted on the basis of preliminary data that a urea/lactic acid–based topical keratolytic agent (ULABTKA) may prevent HFS.

Patients and Methods

A randomized, double-blind phase III trial evaluated 137 patients receiving their first ever cycle of capecitabine at a dose of either 2,000 or 2,500 mg/m2 per day for 14 days. Patients were randomly assigned to a ULABTKA versus a placebo cream, which was applied to the hands and feet twice per day for 21 days after the start of capecitabine. Patients completed an HFS diary (HFSD) daily. HFS toxicity grade (Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events [CTCAE] v3.0) was also collected at baseline and at the end of each cycle. The primary end point was the incidence of moderate/severe HFS symptoms in the first treatment cycle, based on the patient-reported HFSD.

Results

The percentage of patients with moderate/severe HFS symptoms was not different between groups, being 13.6% in the ULABTKA arm and 10.2% in the placebo arm (P = .768 by Fisher's exact test). The odds ratio was 1.37 (95% CI, 0.37 to 5.76). Cycle 1 CTCAE skin toxicity was higher in the ULABTKA arm but not significantly so (33% v 27%; P = .82). No significant differences were observed in other toxicities between groups.

Conclusion

These data do not support the efficacy of a ULABTKA cream for preventing HFS symptoms in patients receiving capecitabine.

INTRODUCTION

Palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia, also known as hand-foot syndrome (HFS) is a widely recognized dose-limiting toxicity of certain chemotherapy agents, specifically capecitabine, infusional fluorouracil, and liposomal doxorubicin.1 This cutaneous adverse effect of chemotherapy, first described almost 30 years ago, has become an increasingly important adverse effect, because these drugs are being commonly used. Despite this, the pathogenesis of this disorder remains unknown. No effective preventative treatment has been definitively established, thus necessitating chemotherapy dose reduction in severe cases.

Data from various phase II and III trials with capecitabine have shown that the incidence of grade 1 to 3 HFS is in the range of 43% to 71%. Grade 3 HFS has been observed in 5% to 24% of these patients.2–7 Despite proposed antidotes for this toxicity,8–10 the only known effective measure has been interruption of chemotherapy and/or dose reduction,11,12 which might compromise the antitumor effect of this chemotherapy.

A small pilot study examined the efficacy of Cotaryl cream (urea, 12%; lactic acid, 6%) for the treatment of capecitabine-associated HFS. Results of this study13 were reported at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology in 2004. The study included patients with advanced breast cancer on capecitabine who were treated with a urea/lactic acid–based cream after developing symptoms of HFS. The authors reported that the patients had resolution of their symptoms in 2 to 3 days and could complete their chemotherapy without interruption or delay. They reported that the cream also benefited patients when it was used for prophylaxis, concluding that the urea/lactic acid–containing preparation that they used was an excellent choice for the prevention and treatment of capecitabine-induced HFS. No adverse effects were reported with the application of this cream.

This proposed benefit for the use of a urea/lactic acid–based cream was supported by other research. Urea is extensively used in dermatology for a wide variety of conditions, including eczema and xerosis. Urea has keratolytic and hydrating properties, which are considered to be useful for the effective treatment of hyperkeratosis and xerotic dermatosis.14 No serious adverse effects have been noted, except for skin irritation with higher doses. Lactic acid is an alpha hydroxy acid commonly used in over-the-counter cosmetic products at concentrations ranging from 5% to 8%. Lactic acid is also thought to have keratolytic and moisturizing properties.15–17 At higher concentrations, it is used as a chemical peel. The notation that hyperkeratosis of the skin has been seen in biopsy specimens of patients with HFS18,19 supported a role for a topical urea/lactic acid preparation.

On the basis of HFS being a prominent clinical problem and on these pilot data,13 this trial was designed to evaluate the potential efficacy and toxicities of a urea/lactic acid–based cream as a means of preventing HFS.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

To be eligible for this trial, patients must have been scheduled to receive capecitabine at a dose of 2,000 mg/m2 per day (1,000 mg/m2 twice a day) or 2,500 mg/m2 per day (1,250 mg/m2 twice a day) for 14 days, with a minimum of four planned cycles, at 21-day intervals. They could not have previously received capecitabine. Patients with pre-existing neuropathy of grade > 2 or those with other dermatologic conditions affecting the hands or feet were not eligible. Patients could not have been planning to use other agents to try to prevent capecitabine-caused HFS. The following topical agents were specifically not permitted to be used during the study because they contain urea or lactic acid: Aqua Care Medicated Calamine lotion (0.3%), Coppertone Waterproof Ultra Protection Sunblock, Dr. Scholl's Smooth Touch deep moisturizing cream, Depicure So Smooth Cream, Dove Moisturizing Cream Wash, Cetaphil Moisturizing Cream, and Vaseline Intensive Care lotion.

All participants provided written informed consent for participating in this trial, which was monitored by local internal review boards as mandated by United States federal regulations. Patients were stratified before random assignment on the basis of age (< 50 years v 50 to 60 years v > 60 years), sex, capecitabine dose (2,000 mg/m2/d v 2,500 mg/m2/d), cancer type (breast v other), and type of therapy (adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy v metastatic disease). Patients were then randomly assigned by using a dynamic allocation method that balances the marginal distributions of the stratification factors.20

Initially, this was designed as a four-arm, phase III, randomized clinical trial involving a two-by-two factorial design to test whether the urea/lactic acid–based cream and/or oral pyridoxine (vitamin B6) could decrease the incidence and severity of capecitabine-caused HFS. However, during the conduct of this study, results from another randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study21 were presented, reporting that pyridoxine is not effective for the prevention of HFS symptoms in patients receiving capecitabine. Therefore, after 72 patients had been accrued, the vitamin B6 and corresponding oral placebo arms were closed, and the study was amended to a two-arm, phase III, randomized clinical trial.

All treatments assignments were blinded to the patients and clinical investigators, with only the North Central Cancer Treatment Group (NCCTG) randomization office, the pharmacists, and the study statisticians having access to the drug assignments for individual patients.

The topical urea/lactic acid (12%/6%) preparation was manufactured at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, and contained the ingredients present in Cotaryl cream, because this product is not available in the United States. Vanicream (PSI Pharmaceutical Specialties, Rochester, MN) was used as the placebo emollient cream.

Participants were instructed to apply one-half to 1 teaspoon of the cream twice a day over their palms and soles on initiation of capecitabine. Study treatment must have started within 3 days of initiation of capecitabine therapy. All patients were provided information regarding the initial signs and symptoms of HFS.

A patient self-reported hand-foot syndrome diary (HFSD) was completed daily while applying the cream. The HFSD was developed in a manner analogous to that used to develop a validated hot flash diary.22 Patients rated skin severity symptoms individually in their hands and in their feet. Definitions of symptoms, which were based on Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v3.0, were provided to patients. A copy of the diary is provided in Appendix Table A1 (online only). Physicians also determined HFS grades for symptoms by using the CTCAE v3.0 criteria (Table 1).

Table 1.

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v3.0

| Grade | Criteria |

|---|---|

| 1 | Minimal skin changes of dermatitis (eg, erythema) without pain |

| 2 | Skin changes (eg, peeling, blisters, bleeding, edema) or pain, not interfering with function |

| 3 | Skin changes with pain, interfering with function |

Patients completed a symptom experience diary (SED) at baseline and weekly while on study. Symptoms from the SED were scored on a scale of 0 to 10 (10 was as bad as possible). Individual queried symptoms are listed in the lower section of Table 2.

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | Urea/Lactic Acid Group (n = 67) |

Placebo (n = 60) |

P | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | Score | SD | No. | % | Score | SD | ||

| Age, years | .974 | ||||||||

| < 50 | 11 | 16 | 9 | 15 | |||||

| 50-60 | 19 | 28 | 17 | 28 | |||||

| > 60 | 37 | 55 | 34 | 57 | |||||

| Sex | .572 | ||||||||

| Female | 52 | 78 | 49 | 82 | |||||

| Capecitabine dose level, mg/m2 | .827 | ||||||||

| 2,000 per day (1,000 twice per day) | 56 | 84 | 51 | 85 | |||||

| 2,500 per day (1,250 twice per day) | 11 | 16 | 9 | 15 | |||||

| Tumor type | .216 | ||||||||

| Breast | 40 | 60 | 43 | 72 | |||||

| Colon | 7 | 10 | 7 | 12 | |||||

| Lung | 20 | 30 | 10 | 17 | |||||

| Therapy type | .627 | ||||||||

| Adjuvant | 11 | 16 | 8 | 13 | |||||

| Metastatic | 56 | 84 | 52 | 87 | |||||

| Race | .610 | ||||||||

| White | 64 | 96 | 59 | 98 | |||||

| Black or African American | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Asian | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Not reported or not available | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Mean baseline symptom scores (higher is better) from SED | |||||||||

| Numbness/tingling in palms of hands | 95.7 | 13.84 | 92.5 | 18.35 | .315 | ||||

| Numbness/tingling in soles of feet | 94.8 | 14.91 | 91.9 | 14.93 | .090 | ||||

| Pain in fingers/hands | 99.4 | 2.95 | 98.7 | 4.33 | .305 | ||||

| Pain in soles of feet | 99.3 | 5.02 | 97.9 | 6.74 | .050 | ||||

| Redness in fingers and hands | 98.8 | 3.70 | 98.9 | 4.93 | .337 | ||||

| Redness in soles of feet | 99.0 | 3.54 | 98.9 | 4.89 | .465 | ||||

| Swelling in fingers and hands | 99.7 | 1.71 | 98.1 | 7.89 | .281 | ||||

| Swelling in soles of feet | 99.7 | 1.71 | 97.9 | 7.50 | .151 | ||||

| Blisters on the fingers and hands | 100.0 | 0.00 | 99.6 | 2.65 | .282 | ||||

| Blisters on soles of feet | 99.8 | 1.23 | 99.6 | 2.65 | .908 | ||||

| Peeling on fingers and hands | 99.8 | 1.23 | 99.3 | 3.71 | .465 | ||||

| Peeling on soles of feet | 99.7 | 2.46 | 98.6 | 5.49 | .125 | ||||

| Difficulty with hand function | 91.7 | 19.10 | 93.8 | 18.15 | .566 | ||||

| Difficulty with walking due to problems in soles of feet | 98.6 | 7.21 | 98.6 | 7.18 | .860 | ||||

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; SED, symptom experience diary.

All other adverse events were measured by using the CTCAE criteria at baseline and weekly. Rash (hand-foot skin reaction) and diarrhea were the only specific symptoms that were queried at each cycle.

As noted above, the initial four-arm, two-by-two factorial design was collapsed into a two-arm, randomized parallel group design, after results from another study21 reported that vitamin B6 was ineffective. An exploratory analysis of clinical data collected before the change in design did not show any significant effect of vitamin B6 or its interaction with urea/lactic acid cream. The final statistical analysis focused on the comparison of urea/lactic acid cream treatment versus placebo. The primary end point of this clinical trial was the incidence of moderate to severe HFS symptoms in the first treatment cycle based on the patient-reported HFSD. Secondary end points included the incidence of moderate to severe HFS symptoms based on the physician-determined HFS grading (CTCAE), times to grade ≥ 2 patient-reported HFS, and physician-determined HFS. Other toxicities were measured by CTCAE, and symptom experience was measured by the SED. Fisher's exact tests and χ2 tests were used for comparisons of binary and other categorical response. The Kaplan-Meier curve was used to profile the time to grade ≥ 2 HFS, and a longitudinal plot was used for describing the daily trend of patient experience of HFS during the first cycle. Statistical significance was considered as a P value < 5%; however, P values were not adjusted for multiplicity induced by multiple secondary analyses. Therefore, it is important to interpret the significant findings from the secondary analysis as exploratory. A sample size of 132 patients (66 for each arm) was determined to provide 80% power to detect an effect size of 25% (50% for placebo group v 25% for active treatment group) at the 5% significance level with a two-sided Fisher's exact test.

RESULTS

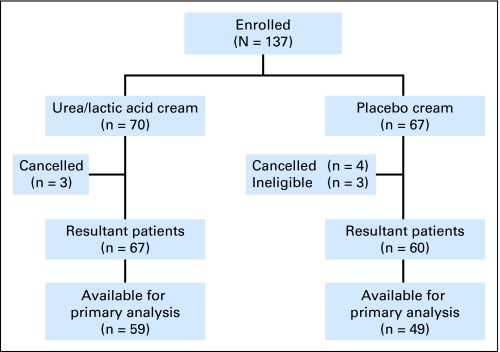

A total of 137 patients were enrolled at 51 institutions between June 23, 2006, and January 23, 2009. Patient flow in this study is illustrated in a CONSORT diagram (Fig 1). The two study arms were well balanced with regard to baseline characteristics (Table 2). Eight patients on the active therapy arm did not provide data for the primary analysis because they did not fill out the HFS diary in cycle 1 (one patient), refused study treatment and did not complete the HFS diary noting that they did not like the cream (one patient), had adverse events causing them to come off the study before completing the HFS diary (three patients), and for other reasons (three patients). For the placebo arm, 11 were excluded because two refused further treatment (one decided to try hospice and one requested a different therapy), two had adverse events, and seven went off for other reasons.

Fig 1.

CONSORT diagram.

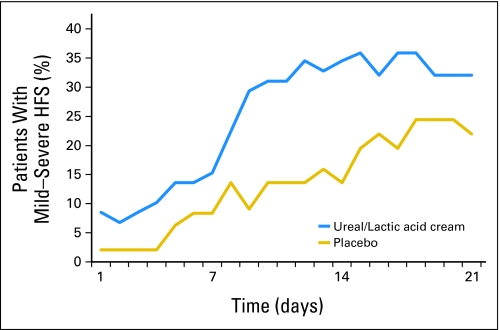

The efficacy results will first be presented for the initial 3-week cycle of therapy, because the primary end point related to this time frame. Table 3 and Figure 2 illustrate the patient-reported HFS per study arm. With regard to the specific primary end point, the difference between the two study arms is not statistically significant (P = .768); in fact, the incidence of moderate to severe HFS was higher (13.6%) in the urea/lactic cream arm than in the placebo control arm (10.2%). The odds of experiencing moderate to severe HFS for patients in the urea/lactic acid-based topical keratolytic agent arm is 1.37 (95% CI, 0.37 to 5.76) times that for patients in the placebo arm. Cycle 1 provider-reported CTCAE HFS grade (Table 4) was also higher in the urea/lactic acid arm, but not significantly so (P = .82). The majority of patients experienced grade 1 CTCAE HFS toxicity (17 v 11), with equal numbers of grades 2 (four of four) and 3 (one of one) in each arm.

Table 3.

Maximum Severity of HFS Symptoms for Cycle 1

| HFS Severity | Location |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hands |

Feet |

Combined |

|||||||||||||

| Urea/Lactic Acid |

Placebo |

P | Urea/Lactic Acid |

Placebo |

P | Urea/Lactic Acid |

Placebo |

||||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | P | |||

| Missing | 8 | 11 | 8 | 11 | 8 | 11 | |||||||||

| None | 35 | 59 | 36 | 73 | .727 | 38 | 64 | 34 | 69 | .324 | 32 | 54 | 31 | 63 | .747 |

| Mild | 18 | 31 | 11 | 22 | .727 | 14 | 24 | 10 | 20 | .324 | 19 | 32 | 13 | 27 | .747 |

| Moderate | 5 | 9 | 1 | 2 | .727 | 6 | 10 | 3 | 6 | .324 | 6 | 10 | 3 | 6 | .747 |

| Severe | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | .727 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | .324 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | .747 |

Abbreviation: HFS, hand-foot syndrome.

Fig 2.

Percentages of patients experiencing any symptoms of hand-foot syndrome (HFS), measured by the patient-reported daily diary, during cycle 1, by study arm.

Table 4.

Maximum CTCAE HFS Grade

| HFS Severity | Urea/Lactic Acid(n = 67) |

Placebo(n = 60) |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | ||

| 0 | 45 | 67 | 44 | 73 | .822 |

| 1 | 17 | 25 | 11 | 18 | .822 |

| 2 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 7 | .822 |

| 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | .822 |

Abbreviations: CTCAE, Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events; HFS, hand-foot syndrome.

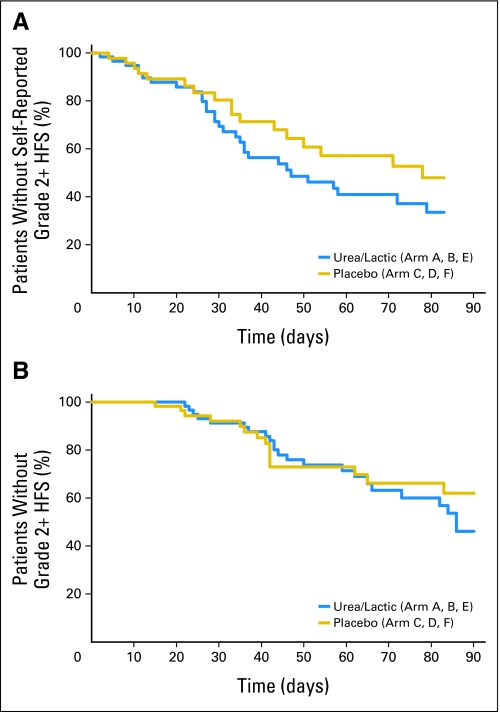

Regarding data generated throughout the four planned cycles of therapy, Figure 3A shows the time to moderate (grade 2) or worse HFS symptoms by patient report. The median time to grade 2 HFS was 47 days for the urea/lactic acid group versus 78 days for the placebo groups (P > .192, log-rank test). Physician-determined HFS grading is illustrated in Figure 3B, showing similar findings (P > .564, log-rank test).

Fig 3.

Times to grade 2 or worse symptoms of hand-foot syndrome (HFS) symptoms based on patient-reported daily diary data (A) or health care provider–determined Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events criteria (B).

Data on HFS symptoms from the patient-reported SED were consistent with what is observed in Table 3 and in Figures 2 and 3. Overall, during the 12 weeks on study (four cycles of capecitabine), the only significant difference in symptoms between groups was in redness in hands, with the urea/lactic acid group having more symptoms (P = .035). When looking at data regarding individual weeks as opposed to the whole study period, there were individual weeks that demonstrated that patients in the urea/lactic acid arm experienced (P < .05) more numbness/tingling in hands/fingers, redness in the hands and soles of feet, swelling in fingers/hands and soles of feet, difficulty with hand function, and peeling fingers/hands and soles of feet.

No significant differences were observed in toxicities between the two groups across all visits for either toxicities determined by the patient-completed SEDs or by health care provider–determined CTCAE toxicities. The overall incidence of diarrhea (grades 1 to 3) was 41%, with 18% having grade 1and 23% having grade 2 or 3 toxicity.

Patient-reported compliance with twice daily application of the cream during cycle 1 was 97% in the urea/lactic acid arm and 100% in the placebo arm (P = .193), for the patients who finished the first cycle and provided data.

DISCUSSION

Although the data from this trial do not suggest any benefit for the urea/lactic acid–based cream, they do not rule out the possibility that the cream actually caused some skin toxicity. Urea and lactic acid both have keratolytic and exfoliating properties, and the application of such creams has been associated with “smarting” or a sharp sensation and irritation, which, by report, typically lasts for about 5 minutes post application. It is possible that irritation such as this may have caused the trend for more reported HFS symptoms in the active therapy arm.

It is evident that more participants in the urea/lactic acid group reported HFS symptoms on day 1 (Fig 2) than did those in the placebo group. Patients were instructed to complete the HFS diary on day 1, which is the day they began capecitabine and the study creams. Therefore, one possible rationale for the differences in day 1 symptoms is that the urea/lactic acid cream caused skin irritation that patients associated with HFS. The baseline data in Table 2 did not suggest more hand-foot symptoms in the treatment group before starting any study cream, supporting that there was not a difference in the two arms before treatment initiation.

Although there was no striking evidence of difference in the patients dropped from the primary (first cycle) analysis, the proportions (12% and 18% for the active and placebo groups) could be a potential source of bias and thus exert an influence on the primary end point analysis.

One might question selecting data from cycle 1 rather than from all four cycles as the primary end point. The rationale for choosing the data from cycle 1 was that the dropout rate following this time point was likely to be higher, given the nature of the disease and potential disease progression on therapy. Additionally, it was thought that the results of the first cycle would likely reflect the outcome of subsequent cycles. This was borne out in the analysis of data from cycles 2 to 4, which basically replicated the data from the first cycle, thereby providing further confirmation of the primary analysis.

One might also ask whether this study should have had more power to look for smaller differences, noting that the study was designed to have at least 80% power to detect a difference of 25% at the 5% significance level. It is conceivable that the study may be underpowered for a smaller difference (eg, 15% to 24%) which might be considered to be clinically meaningful. Nonetheless, since the trends were going in the wrong direction (placebo was looking better than the active agent), the chance that twice our sample size would have shown a significant difference in favor of the active therapy arm was low.

The incidence of HFS and diarrhea in this study, while being in the range of that seen in other reports,2,4–7,23 was at the lower end of what is seen in the literature. This is probably because most of the patients (84%) received capecitabine at a dose of 2,000 mg/m2 as opposed to the higher dose of 2,500 mg/m2. The incidence of grade 3 HFS symptoms was also quite low in this trial, with an overall incidence of 1.6%. This contrasts with other trials2–6 in which grade 3 HFS symptoms were seen in 13% to 24% of patients. The reason for this may be that this trial was strict about having patients discontinue capecitabine and contact their health care provider if they experienced grade 2 HFS symptoms or diarrhea, thereby averting grade 3 events in the vast majority of patients. Study nurses were in close contact with the study patients. This supports the importance of patient education, active surveillance, and communication.

To date, the only established treatment for HFS is treatment modification (dose reduction or discontinuation). This strategy has been demonstrated to be effective in the management of HFS.24 Nonetheless, several published practice guidelines25 and research studies recommend the use of urea and lactic acid (or keratolytic) agents for HFS caused by capecitabine and newer targeted therapies, including sorafenib,26 sunitinib,27 lapatinib,28 and regorafenib.29 Additionally, many over-the-counter topical emollients contain urea, and patients are commonly educated to apply such creams when initiating capecitabine. Results of this study, however, raise concerns with regard to the wisdom of this advice.

In total, the use of urea/lactic acid for prevention of HFS in patients receiving capecitabine therapy cannot be supported on the basis of the results of this trial. Further studies are warranted to determine the best approach to prevent and manage this adverse effect.

Appendix

The following are additional institutions and participants in the North Central Cancer Treatment Group Study N05C5: St. Vincent Regional Cancer Center Community Clinical Oncology Program (CCOP), Green Bay, WI: Anthony J. Jaslowski, MD; Geisinger Medical Center CCOP, Danville, PA: Albert M. Bernath Jr, MD; Altru Cancer Center, Grand Forks, ND: Todor Dentchev, MD; Mayo Clinic Florida, Jacksonville, FL: Kurt A. Jaeckle, MD; Duluth Clinic CCOP, Duluth, MN: Daniel A. Nikcevich, MD; Iowa Oncology Research Association CCOP, Des Moines, IA: Robert J. Behrens, MD; Meritcare Hospital CCOP, Fargo, ND: Preston D. Steen, MD; Siouxland Hematology Oncology Associates CCOP, Sioux City, IA: Donald B. Wender, MD; Toledo Community Hospital Oncology Program CCOP, Sylvania, OH: Rex B. Mowat, MD; Wichita CCOP, Wichita, KS: Shaker R. Dakhil, MD; Northern Indiana Cancer Research Consortium, South Bend, IN: Robin T. Zon, MD; Upstate Carolina CCOP, Spartanburg, SC: James D. Bearden III, MD; Cedar Rapids Oncology Project CCOP, Cedar Rapids, IA: Martin Wiesenfeld, MD; Dayton Clinical Oncology Program, Dayton, OH: Howard M. Gross, MD; Montana Cancer Consortium CCOP, Billings, MT: Benjamin T. Marchello, MD; Medcenter One Health System, Bismarck, ND: Edward J. Wos, MD; CentraCare Clinic, St. Cloud, MN: Donald J. Jurgens, MD; Sioux Community Cancer Consortium, Sioux Falls, SD: Loren K. Tschetter, MD; Columbus CCOP, Columbus, OH: John P. Kuebler, MD; Missouri Valley Cancer Consortium CCOP, Omaha, NE: Gamini S. Soori, MD; Natalie W. Bryant Cancer Center, Tulsa, OK: Alan M. Keller, MD; Lehigh Valley Hospital, Allentown, PA: Suresh G. Nair, MD.

Table A1.

Hand-Foot Syndrome Diary

| Day of Week | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | Day 6 | Day 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date (month/day) | ____/____ | ____/____ | ____/____ | ____/____ | ____/____ | ____/____ | ____/____ |

| Palms of hands symptoms(check one for each day) | ___none | ___none | ___none | ___none | ___none | ___none | ___none |

| ___mild | ___mild | ___mild | ___mild | ___mild | ___mild | ___mild | |

| ___moderate | ___moderate | ___moderate | ___moderate | ___moderate | ___moderate | ___moderate | |

| ___severe | ___severe | ___severe | ___severe | ___severe | ___severe | ___severe | |

| Soles of feet symptoms(check one for each day) | ___none | ___none | ___none | ___none | ___none | ___none | ___none |

| ___mild | ___mild | ___mild | ___mild | ___mild | ___mild | ___mild | |

| ___moderate | ___moderate | ___moderate | ___moderate | ___moderate | ___moderate | ___moderate | |

| ___severe | ___severe | ___severe | ___severe | ___severe | ___severe | ___severe |

NOTE. Date of the start of this week __/___/___ should be the first day of starting capecitabine. Grading of hand-foot syndrome symptoms are as follows: None, no changes from your usual; Mild, minor skin changes (such as redness), but no pain; Moderate, skin changes (such as peeling, blisters, bleeding, or swelling) or mild pain, but no limitation of your movement; Severe, skin changes or pain that interfere with the normal movement of your hands (such as holding things) or feet (such as walking).

Footnotes

Supported by National Cancer Institute Community Clinical Oncology Program Grant No. CA-37404 and in part by Public Health Service Grants No. CA-25224, CA-35195, CA-35113, CA-35267, CA-35448, CA-35269, CA-35101, CA-37417, CA-35103, CA-35415, CA-35431, CA-35119, CA-52352, CA-35090, CA-35103, CA-63849, CA-67575, CA-03011, CA-114558, CA-67753, and CA-95968, by the National Institutes of Health mentorship Grant CA-124477, and by Roche Pharmaceuticals, Basel, Switzerland.

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

Clinical trial information can be found for the following: NCT00296036.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Rui Qin, Smitha P. Menon, Charles L. Loprinzi

Financial support: Kendrith M. Rowland Jr, Eduardo R. Pajon Jr, Charles L. Loprinzi

Administrative support: Kendrith M. Rowland Jr, Eduardo R. Pajon Jr, Charles L. Loprinzi

Provision of study materials or patients: Kendrith M. Rowland Jr, Sachdev Thomas, Robert Delaune, Diana Christian, Eduardo R. Pajon Jr, Jeffrey L. Berenberg, Charles L. Loprinzi

Collection and assembly of data: Sherry L. Wolf, Rui Qin, Daniel V. Satele, Charles L. Loprinzi

Data analysis and interpretation: Sherry L. Wolf, Rui Qin, Daniel V. Satele, Charles L. Loprinzi

Manuscript writing: Sherry L. Wolf, Rui Qin, Daniel V. Satele,Charles L. Loprinzi

Final approval of manuscript: Sherry L. Wolf, Rui Qin, Smitha P. Menon, Kendrith M. Rowland Jr, Sachdev Thomas, Robert Delaune, Diana Christian, Eduardo R. Pajon Jr, Daniel V. Satele, Jeffrey L. Berenberg, Charles L. Loprinzi

REFERENCES

- 1.Clark AS, Vahdat LT. Chemotherapy-induced palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome: Etiology and emerging therapies. Support Cancer Ther. 2004;1:213–218. doi: 10.3816/SCT.2004.n.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blum JL, Dieras V, Lo Russo PM, et al. Multicenter, phase II study of capecitabine in taxane-pretreated metastatic breast carcinoma patients. Cancer. 2001;92:1759–1768. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20011001)92:7<1759::aid-cncr1691>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fumoleau P, Largillier R, Clippe C, et al. Multicentre, phase II study evaluating capecitabine monotherapy in patients with anthracycline- and taxane-pretreated metastatic breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:536–542. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oshaughnessy JA, Blum J, Moiseyenko V, et al. Randomized, open-label, phase II trial of oral capecitabine (Xeloda) vs. a reference arm of intravenous CMF (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and 5-fluorouracil) as first-line therapy for advanced/metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:1247–1254. doi: 10.1023/a:1012281104865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reichardt P, Von Minckwitz G, Thuss-Patience PC, et al. Multicenter phase II study of oral capecitabine (Xeloda(“)) in patients with metastatic breast cancer relapsing after treatment with a taxane-containing therapy. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1227–1233. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller KD, Chap LI, Holmes FA, et al. Randomized phase III trial of capecitabine compared with bevacizumab plus capecitabine in patients with previously treated metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:792–799. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmoll HJ, Cartwright T, Tabernero J, et al. Phase III trial of capecitabine plus oxaliplatin as adjuvant therapy for stage III colon cancer: A planned safety analysis in 1,864 patients. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:102–109. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chin SF, Tchen N, Oza AM, et al. Use of “Bag Balm” as topical treatment of palmer-plantar erythrodysesthsia syndrome (PPES) in patients receiving selected chemotherapeutic agents. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2001;20(suppl):409a. abstr 1632. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopez AM, Wallace L, Dorr RT, et al. Topical DMSO treatment for pegylated liposomal doxorubicin-induced palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1999;44:303–306. doi: 10.1007/s002800050981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagore E, Insa A, Sanmartín O. Antineoplastic therapy-induced palmar plantar erythrodysesthesia (‘hand-foot') syndrome: Incidence, recognition and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2000;1:225–234. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200001040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blum J, Jones S, Buzdar A, et al. Capecitabine (Xeloda) in 162 patients with paclitaxel-pretreated MBC: Updated results and analysis of dose modifications. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37 abstr 693. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cassidy J, Twelves C, Van Cutsem E, et al. First-line oral capecitabine therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: A favorable safety profile compared with intravenous 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:566–575. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pendharkar D, Goyal H Batra Cancer Center. Novel and effective management of capecitabine induced hand foot syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(suppl):751. abstr 8105. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ademola J, Frazier C, Kim SJ, et al. Clinical evaluation of 40% urea and 12% ammonium lactate in the treatment of xerosis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3:217–222. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200203030-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kneedler JA, Sky SS, Sexton LR. Understanding alpha-hydroxy acids. Dermatol Nurs. 1998;10:247–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Scott EJ, Yu RJ. Control of keratinization with alpha-hydroxy acids and related compounds: I. Topical treatment of ichthyotic disorders. Arch Dermatol. 1974;110:586–590. doi: 10.1001/archderm.110.4.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Scott EJ, Yu RJ. Alpha hydroxy acids: Procedures for use in clinical practice. Cutis. 1989;43:222–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milano G, Etienne-Grimaldi MC, Mari M, et al. Candidate mechanisms for capecitabine-related hand-foot syndrome. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66:88–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03159.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsuruta D, Mochida K, Hamada T, et al. Chemotherapy-induced acral erythema: Report of a case and immunohistochemical findings. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:386–388. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2000.00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pocock SJ, Simon R. Sequential treatment assignment with balancing for prognostic factors in the controlled clinical trial. Biometrics. 1975;31:103–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee S, Lee S, Chun Y, et al. Pyridoxine is not effective for the prevention of hand foot syndrome (HFS) associated with capecitabine therapy: Results of a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(suppl):494s. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.1807. abstr 9007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sloan JA, Loprinzi CL, Novotny PJ, et al. Methodologic lessons learned from hot flash studies. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:4280–4290. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.23.4280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abushullaih S, Saad ED, Munsell M, et al. Incidence and severity of hand-foot syndrome in colorectal cancer patients treated with capecitabine: A single-institution experience. Cancer Invest. 2002;20:3–10. doi: 10.1081/cnv-120000360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scheithauer W, Blum J. Coming to grips with hand-foot syndrome: Insights from clinical trials evaluating capecitabine. Oncology (Williston Park) 2004;18:1161–1168. discussion 1173-1176, 1181-1184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wood L, Lemont H, Jatoi A, et al. Practical considerations in the management of hand-foot skin reaction caused by multikinase inhibitors. Community Oncol. 2010;7:23–29. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tate L, Laferriere N, Lentini G, et al. 12414, A Phase III randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of sorafenib as adjuvant treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma after surgical resection or local ablation. Leverkusen, Germany: Bayer HealthCare, AG, D-51368; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Cancer Institute; 2006. E2805, Phase III Randomized Study of Adjuvant Sunitinib Malate Versus Sorafenib in Patients With Resected Renal Cell Carcinoma. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perez E. GlaxoSmithKline, North Central Cancer Treatment Group (NCCTG), Breast International Group (BIG); 2008. N063D/BIG 2-06, ALTTO: Adjuvant Lapatinib and/or Trastuzumab Treatment Optimisation Study—A randomised, multi-centre, open-label, phase III study of adjuvant lapatinib, trastuzumab, their sequence and their combination in patients with HER2/ErbB2 positive primary breast cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 29.D-51368 Leverkusen, Germany: Bayer HealthCare AG; 2010. 14387: A Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Phase III Study of Regorafenib Plus BSC Versus Placebo Plus BSC in Patients With Metastatic Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Who Have Progressed After Standard Therapy. [Google Scholar]