Abstract

This spectroscopic study examined the steady-state and kinetic parameters governing the cross-bridge effect on the increased Ca2+ affinity of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-cardiac troponin C (HCM-cTnC) mutants. Previously, we found that incorporation of the A8V and D145E HCM-cTnC mutants, but not E134D into thin filaments (TFs), increased the apparent Ca2+ affinity relative to TFs containing the WT protein. Here, we show that the addition of myosin subfragment 1 (S1) to TFs reconstituted with these mutants in the absence of MgATP2−, the condition conducive to rigor cross-bridge formation, further increased the apparent Ca2+ affinity. Stopped-flow fluorescence techniques were used to determine the kinetics of Ca2+ dissociation (koff) from the cTnC mutants in the presence of TFs and S1. At a high level of complexity (i.e. TF + S1), an increase in the Ca2+ affinity and decrease in koff was achieved for the A8V and D145E mutants when compared with WT. Therefore, it appears that the cTnC Ca2+ off-rate is most likely to be affected rather than the Ca2+ on rate. At all levels of TF complexity, the results obtained with the E134D mutant reproduced those seen with the WT protein. We conclude that strong cross-bridges potentiate the Ca2+-sensitizing effect of HCM-cTnC mutants on the myofilament. Finally, the slower koff from the A8V and D145E mutants can be directly correlated with the diastolic dysfunction seen in these patients.

Keywords: Actin, Biophysics, Calcium, Cardiac Muscle, Cardiac Hypertrophy, Contractile Protein, Fluorescence, Genetic Diseases, Myosin, Troponin

Introduction

Some forms of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)2 can be inherited as autosomal dominant diseases and have been implicated in sudden cardiac death in the young and in athletes (1). Mutations that cause this disease have been found in 13 myofilament proteins, including cardiac troponin T (cTnT) and troponin I (cTnI) (2, 3), but only a few mutations occur in cardiac troponin C (cTnC) (4, 5). Most cardiac troponin (cTn) mutations linked to HCM affect the relaxation properties of the heart by reducing the intraventricular relaxation time, which decreases the degree of ventricular filling during diastole (5). However, the mechanisms governing this impaired relaxation are largely unknown.

TnC consists of two domains that are connected by a flexible linker (6). The cTnC C terminus has two EF-hands (helix-loop-helix motifs) containing high affinity Ca2+-binding sites III and IV (KCa ∼ 107 m−1). The C-domain sites bind Ca2+ and Mg2+ competitively (KMg ∼ 103 m−1), which helps to maintain cTnC attached to the thin filament (TF). In the cTnC N-domain, site I is inactive, and site II binds Ca2+ with a lower affinity (∼105 m−1) (7). The N-domain is considered the “regulatory domain” as Ca2+ binding to site II is specific and triggers muscle contraction. The N-domain also contains the N-helix, an additional 14-residue modulatory helix at the N terminus.

Our group has characterized the effects of all five known cTnC mutations (A8V, L29Q, C84Y, E134D, and D145E) associated with HCM (5). Consistent with other HCM cTn mutations, three of the five cTnC mutations (A8V, C84Y, and D145E) were associated with an increase in the Ca2+ sensitivity of force development in skinned cardiac fibers (respectively, +0.36, +0.27, and +0.24 pCa units). The A8V and D145E cTnC mutants also had the ability to increase the Ca2+ activated maximal force compared with the WT when reconstituted into cardiac skinned fibers (4). However, the Ca2+ affinity of TFs containing fluorescently labeled cTnC mutants did not recapitulate the increased Ca2+ sensitivity observed in skinned fibers (8). We proposed that the D145E mutant influences the regulation of contraction by impairing the ability of cTnC to bind Ca2+ at site IV (8). In support of this premise, we previously demonstrated that the D145E mutation decreased the amount of cTnC α-helicity in the Ca2+-Mg2+-loaded condition using circular dichroism. In addition, the D145E cTnC mutant did not show any fluorescent changes that normally coincide with Ca2+ binding to the C-terminal domain (8). Only one prior report identified a mutation in cTnC (L29Q), which was found in an HCM patient (9). However, it remains unresolved whether this mutation is truly malignant because the in vitro and in situ results from four different groups do not all coincide (10–13).

Myofilament protein-protein interactions have substantial effects on the Ca2+ affinity of cTnC. Within the cTn complex, Ca2+ binding to cTnC increases ∼10-fold in comparison to isolated cTnC, primarily as a result of its interaction with cTnI (7, 14–16). When cTn interacts with the TF, the Ca2+ affinity is reduced; however, the addition of myosin subfragment 1 (S1) to TFs increases the Ca2+ affinity again ∼10-fold (17, 18). It is widely accepted that HCM myofilament mutations and strong cross-bridges modulate the Ca2+ affinity and the rate of Ca2+ dissociation from cTnC (18–21). It is expected that these factors will influence cardiac muscle relaxation by prolonging the Ca2+ and force transients (5, 22–27), which can be correlated with the diastolic dysfunction seen in patients and animal models of hypertrophy.

This study examines the effects of the A8V, E134D, and D145E HCM-cTnC mutants on the kinetics of Ca2+ dissociation from cardiac TFs. To fully recapitulate the effects of A8V and D145E cTnC on the Ca2+ sensitivity of TFs, we increased the system's complexity by including myosin S1. Mechanistic studies such as this one provide new insights into how cardiomyopathic mutations impart myofilament dysfunction and may lead to the identification of specific targets for future therapeutic interventions.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mutation, Expression, Purification, and Labeling of Proteins

Mutagenesis, expression, and purification of cTnCs (WT, A8V, C84Y, E134D, and D145E) followed previous methods (4, 8). For cTn measurements, WT, A8V, E134D, and D145E cTnC were fluorescently labeled with IAANS at Cys-35 and Cys-84 (14). cTnC-C84Y was labeled only at Cys-35 with cTnC-C84S used as a control for the C84Y mutant (14). For TF measurements, Cys-35 was mutated to Ser in WT, A8V, E134D, and D145E cTnC to confine the IAANS label to Cys-84 (14). cDNAs cloned in our laboratory from human cardiac tissue were used for the expression and purification of cTnI (28) and cTnT (29). Porcine cardiac tropomyosin (Tm) and myosin were isolated from left ventricles (11). Myosin S1 was prepared from rabbit skeletal myosin (30), and F-actin was prepared from rabbit skeletal muscle acetone powder (31).

Multiprotein Complex Formation

Fluorescent ternary cTn complexes (8, 14) and fluorescent TFs (i.e. F-actin:Tm:cTn in a 7:1:1 ratio) (11) were prepared using IAANS-labeled cTnC as described previously.

Determination of Apparent Ca2+ Affinities of cTn and TFs

Ca2+ binding to labeled cTn complexes (0.5 μm) and TFs (0.05 g of protein/liter) containing HCM-cTnC mutants were measured as previously described (8) by monitoring the peak emission intensity (450 nm) from the IAANS-labeled proteins excited at 330 nm in standard buffer (μ ∼ 185) containing 2 mmol/liter EGTA, 5 mmol/liter nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA), 1.25 mmol/liter MgCl2 (0.45 mmol/liter free [Mg2+]), 120 mmol/liter MOPS, 90 mmol/liter KCl, and 1 mmol/liter DTT in pH 7.0 at 21 °C.

Determination of Apparent Ca2+ Affinities of TFs in the Presence of Myosin S1

To determine the optimal myosin S1 concentrations to be employed, IAANS-labeled WT TFs (0.05 g protein/liter) were titrated with S1 (prepared in standard buffer) to determine the concentration of S1 that caused the half-maximal change in fluorescence from TFs (data not shown). This S1 concentration was 0.02 g of protein/liter (∼1.58 myosin heads per seven actins within the TF) and was used during measurements for the apparent Ca2+ affinity of labeled TFs in the presence of myosin S1 in standard buffer, as mentioned above for cTn. The apparent Ca2+ affinity of labeled TFs (0.05 g/liter) in the presence of S1 (0.02 g/liter) and ATP was measured in the following buffer: 2 mmol/liter EGTA, 5 mmol/liter NTA, 4.64 mmol/liter MgCl2 (∼0.49 mmol/liter free [Mg2+]), 4.8 mmol/liter ATP (∼3.14 MgATP2−), 120 mmol/liter MOPS, 46.5 mmol/liter KCl, 1 mmol/liter DTT, 15.3 mmol/liter phosphocreatine, and 15 units/ml creatine kinase, pH 7.0, at 21 °C (μ ∼ 215). The fluorescence data were fitted to a version of the Hill equation using the software suite of SigmaPlot 11.0, and the Ca2+ affinities are reported as the pCa50 (i.e. −log[Ca2+]free) ± S.E.

Determination of Ca2+ Dissociation Rates (koff)

Measurements were performed using a BioLogic (Claix, France) model μSFM-20 stopped-flow instrument outfitted with a Berger ball mixer. The data were captured and digitized on a Jasco 6500 spectrofluorometer at 21 °C. The estimated dead time was ∼1.7 ms. The rates of conformational changes induced by Ca2+ removal with EGTA from labeled cTn and TFs were measured by monitoring the fluorescence arising from IAANS-labeled cTnC within the various complexes. IAANS was excited at 330 nm using a xenon bulb, and emission was monitored at 444 nm using monochromators set to 10-nm bandwidths. Each koff represents an average of at least seven traces, fit with a single exponential and repeated 4–6 times. In Ca2+ dissociation experiments monitoring IAANS-labeled cTn and TFs, protein samples were prepared in standard buffer containing 1.778 mm CaCl2 (pCa ∼ 5.59) and mixed with an equal volume of the same buffer in which Ca2+ was omitted and 12 mm EGTA was added. After mixing, the [cTn], [TF], and pCa were 0.5 μm, 0.15 g/liter, and 7.48, respectively. In experiments monitoring TFs in the presence of S1 and ATP, protein samples were prepared in the following buffer: 2.25 mmol/liter EGTA, 5.63 mmol/liter NTA, 5.55 mmol/liter MgCl2 (∼0.53 mmol/liter free [Mg2+]), 5.8 mmol/liter ATP (∼3.84 mmol/liter MgATP2−), 45 mmol/liter KCl, 135 mmol/liter MOPS, 1.984 mmol/liter CaCl2 (pCa ∼ 5.61), 18.5 mmol/liter phosphocreatine, and 15 units/ml creatine kinase, pH 7.0, at 21 °C (μ ∼ 240). Samples were then mixed with an equal volume of the following buffer: 20 mmol/liter EGTA, 5 mmol/liter NTA, 4.91 mmol/liter MgCl2, 45 mmol/liter KCl, 120 mmol/liter MOPS, and 5.19 mmol/liter ATP, pH 7.0 at 21 °C (μ ∼ 240). After mixing, the [cTn], [TF], and pCa were 0.15 g/liter, 0.11 g/liter, and 7.39, respectively.

In experiments monitoring TFs in the presence of myosin S1 (rigor), measurements were performed on an Applied Photophysics (Leatherhead, Surrey, UK) model SX17MV stopped-flow apparatus. IAANS was excited using a xenon bulb with the monochromator set to 330 nm, and the emission recorded with a 435 nm long-pass filter (slit widths were 5 nm). Protein samples were prepared in standard buffer with 1.806 mm CaCl2 (pCa ∼ 5.55) and mixed with an equal volume of the same buffer in which Ca2+ and KCl were omitted and 22 mm EGTA was added. After mixing, the [cTn], [TF], and pCa were 0.25 g/liter, 0.11 g/liter, and 7.49, respectively.

Skinned Fiber Measurements

The skinned-fiber measurements were performed according to Landstrom et al. (4). Briefly, the skinned cardiac fibers were mounted using stainless steel clips connected to a force transducer and immersed in relaxation solution (pCa 8.0). The fiber was stretched just enough to remove slack, and then stretched to 1.2× its length. This results in estimated sarcomere lengths between 2.2 and 2.3 μm. Skinned porcine papillary fibers depleted of cTnC were reconstituted with cTnC (WT, A8V, E134D, or D145E) containing the additional mutation C35S and the IAANS probe at Cys-84. After cTnC reconstitution, the Ca2+ sensitivity and the maximal force recovery were evaluated. Recently our group has shown by Western blot analysis that 14.0 ± 5.3% of the endogenous cTnC remains in the TF after CDTA extraction, and incubation of fibers with WT or mutant cTnC is able to restore the full complement of cTnC back into the muscle fibers (32).

Preparation of Buffered Calcium Solutions

Methods for solving the free and bound metal ion equilibria in our solutions containing EGTA, NTA, and ATP were provided by the computer program pCa Calculator (33). In steady-state measurements, the program corrected for dilutions that occurred during the addition of incremental amounts of CaCl2.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as the average ± S.E. of 4–6 experiments (unless otherwise stated). Significant differences were determined using an unpaired Student's t test (SigmaPlot Version 11.0), with significance defined as p < 0.05.

RESULTS

The pCa50 (i.e. the −log[Ca2+]free which yields the half-maximum response) values for cTn and TFs containing the cTnC mutants are reported in Table 1. To further investigate the mechanisms underlying the increased Ca2+ sensitivity of the myofilament, we added S1 to TFs and measured the apparent Ca2+ affinities in the presence and absence of ATP (summarized in Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Apparent Ca2+ affinities, Hill coefficients, and Ca2+ off rates of IAANS-labeled cTnC mutants in complex

Values are given as the mean ± S.E.

| Incorporated cTnC | Measurement | System |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cTn | TF | TF + S1 + ATPa | TF + S1b | ||

| WT | pCa50 | 6.69 ± 0.01c | 6.13 ± 0.02c | 6.12 ± 0.01 | 6.52 ± 0.02 |

| nHill | 1.17 ± 0.02c | 1.28 ± 0.05 | 1.61 ± 0.03 | 1.50 ± 0.07 | |

| koff (s−1) | 18.95 ± 0.60 | 95.78 ± 6.68 | 139.12 ± 6.93 | 6.93 ± 0.41 | |

| kon (108m−1sec−1)d | 0.94 | 1.30 | 1.84 | 0.23 | |

| A8V | pCa50 | 6.58 ± 0.01c,e | 6.27 ± 0.02c,e | 6.25 ± 0.02e | 6.75 ± 0.01e |

| nHill | 0.99 ± 0.01c,e | 1.46 ± 0.09e | 1.79 ± 0.04e | 2.47 ± 0.14e | |

| koff (s−1) | 16.31 ± 0.69e | 79.80 ± 10.34e | 75.28 ± 6.41e | 5.51 ± 0.16e | |

| kon (108m−1s−1)d | 0.62 | 1.46 | 1.34 | 0.31 | |

| E134D | pCa50 | 6.69 ± 0.01c | 6.11 ± 0.02c | 6.08 ± 0.01e | 6.48 ± 0.03 |

| nHill | 1.14 ± 0.02c | 1.29 ± 0.04 | 1.57 ± 0.04 | 1.14 ± 0.05e | |

| koff (s−1) | 19.67 ± 0.67 | 112.13 ± 15.42 | 146.74 ± 6.17 | 7.13 ± 0.17 | |

| kon (108m−1s−1)d | 0.97 | 1.43 | 1.74 | 0.21 | |

| D145E | pCa50 | 6.81 ± 0.01c,e | 6.21 ± 0.02c,e | 6.15 ± 0.01 | 6.66 ± 0.02e |

| nHill | 1.11 ± 0.01c,e | 1.42 ± 0.06e | 1.67 ± 0.01 | 1.30 ± 0.04e | |

| koff (s−1) | 14.60 ± 0.95e | 129.18 ± 11.97e | 129.17 ± 4.87 | 5.60 ± 0.11e | |

| kon (108m−1s−1)d | 0.95 | 2.08 | 1.84 | 0.25 | |

| WT-C84S | pCa50 | 6.77 ± 0.01c | |||

| nHill | 0.77 ± 0.01c | ||||

| koff (s−1) | 22.65 ± 1.90 | ||||

| kon (108m−1s−1)d | 1.33 | ||||

| C84Y | pCa50 | 6.76 ± 0.01c | |||

| nHill | 0.79 ± 0.01c | ||||

| koff (s−1) | 24.58 ± 0.21 | ||||

| kon (108m−1s−1)d | 1.40 | ||||

a TF plus myosin S1 and MgATP2−.

b TF plus myosin S1.

c Data are from Pinto et al. (8).

d kon values are estimated from Kd = koff/kon.

e p < 0.05 compared to WT (n = 3–5).

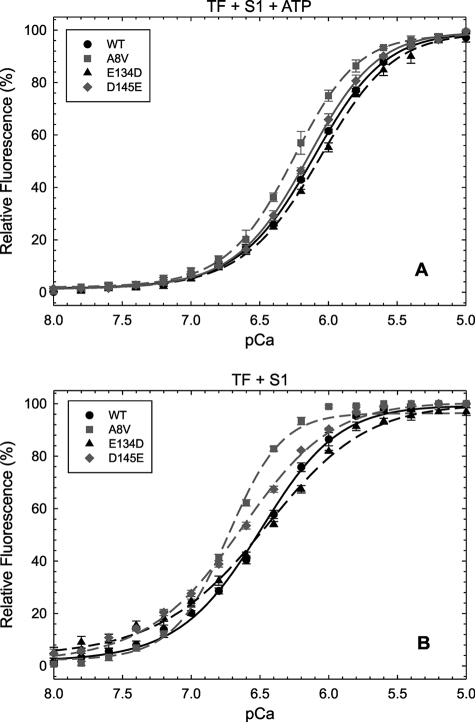

The ΔpCa50 (i.e. mutant pCa50-WT pCa50) for TFs (alone) containing the A8V mutant was +0.14, and essentially the same ΔpCa50 was observed for this mutant in TFs interacting with S1 and ATP (i.e. the conditions conducive to the formation of cycling cross-bridges) (Fig. 1A and Table 1). Therefore, there was no enhancement of the A8V cTnC Ca2+ affinity upon inclusion into a more complex system. However, when experiments were performed with S1 in the absence of ATP (i.e. the condition leading to rigor cross-bridge formation), a significantly greater increase in the ΔpCa50 (+0.23) of the mutant occurred (Fig. 1B and Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

Ca2+ dependent changes in fluorescence arising from IAANS-labeled cTnC mutants in TFs interacting with S1. Shown are the effects of labeled cTnC mutants in TFs interacting with S1 under conditions that favor weakly (+ATP) (A) and strongly (−ATP) (B) bound cross-bridges on the Ca2+ dependence of fluorescence. Relative fluorescence values (%) are plotted as a function of pCa (−log [Ca2+]free). Data are reported as the mean ± S.E. (n = 4 - 5).

The addition of S1 and ATP to TFs containing D145E cTnC did not significantly change its Ca2+ affinity compared with the WT protein (ΔpCa50 = + 0.03) (Fig. 1A and Table 1). When S1 was added in the absence of ATP, an increase in the Ca2+ affinity was observed (ΔpCa50 = +0.14) (Fig. 1B and Table 1). TFs containing E134D cTnC largely reproduced the Ca2+ affinities of WT TFs in all of the tested systems (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Only TFs containing A8V cTnC interacting with S1 and ATP displayed a significant increase in cooperativity (nHill) compared with the WT protein (Table 1). TFs containing E134D and D145E cTnC interacting with S1 in the absence of ATP displayed a significant decrease in nHill; however, the A8V mutant led to an increased nHill value over the WT control (Table 1).

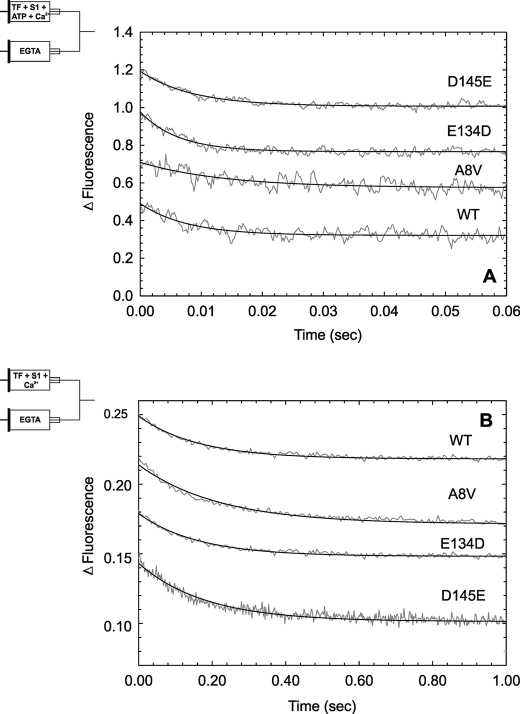

The A8V, D145E, and E134D cTnC mutants were examined for their abilities to affect the kinetics of Ca2+ dissociation from TFs in the presence and absence of S1. All of the data were obtained by measuring the Ca2+-dependent conformational changes that occur in IAANS-labeled cTnC. Figs. 2 and 3 demonstrate typical traces for each mutant and WT protein at increasing levels of thin filament complexity and cross-bridges. For steady-state and fast-kinetic measurements of the cTn complex, we used the double IAANS-labeled cTnC configuration. In the cTn complex, A8V (koff = 16.31/s) and D145E (koff = 14.60/s) cTnC showed a statistically significant decrease in the Ca2+ dissociation rate compared with WT (koff = 18.95/s) (Fig. 2A and Table 1). In contrast, these two mutants displayed opposite effects on the Ca2+ affinity, as previously reported (8), with the Ca2+ affinity of A8V cTnC lower than that of the WT, whereas with D145E cTnC, the Ca2+ affinity was higher (see pCa50 values in Table 1). An estimate of the on rate (kon) implies a slower rate of Ca2+ association to cTn reconstituted with A8V cTnC (Table 1). The measured off-rate of E134D cTnC was 19.67/s, similar to that obtained for WT cTn. We also attempted to evaluate the Ca2+ off-rate from the cTn complex containing C84Y cTnC and compare it to its respective control (C84S cTnC). In this case, the Ca2+ off-rate was monitored using the fluorescent label attached only to Cys-35. However, because the probe does not produce any measurable Ca2+-dependent changes in fluorescence beyond the level of cTn, we were unable to analyze this protein in more complex systems. No significant differences were observed in either the pCa50 or koff values when compared with the control (C84S cTnC) (Table 1).

FIGURE 2.

Time course of Ca2+ dissociation from IAANS-labeled HCM-cTnC mutants incorporated into cTn or TFs. A, Ca2+ dissociation traces from WT and HCM-cTnCs incorporated into cTn complexes are shown. The increase in IAANS fluorescence is from cTnC double-labeled (C35IAANS and C84IAANS). B, shown are Ca2+ dissociation traces from WT and HCM-cTnCs incorporated into TFs, monitored by a decrease in IAANS fluorescence from mono-cysteine cTnC (C84IAANS). In A and B, proteins equilibrated in pCa ∼ 5.59 were mixed with EGTA buffer to obtain pCa ∼ 7.48. The signals are an average of 7–10 experimental runs, and the solid line shows the fit to a single exponential equation. The experimental conditions are described in detail under “Experimental Procedures.” The signals are offset along the ordinate for easier viewing. The means ± S.E. are shown in Table 1 (n = 3–5).

FIGURE 3.

Time course of Ca2+ dissociation from HCM-cTnC mutants incorporated into TFs in the presence of myosin S1. A, Ca2+ dissociation traces from WT and HCM-cTnCs incorporated into TFs under conditions that favor cycling cross bridges (S1 + MgATP2−) are shown. B, Ca2+ dissociation traces from WT and HCM-cTnCs incorporated into TFs under conditions that favor rigor bridges (S1 without ATP) are shown. The Ca2+ dissociation is monitored as a decrease in IAANS fluorescence from TFs containing mono-cysteine (C84IAANS) HCM-cTnC mutants. TFs and S1 equilibrated in pCa ∼5.61 were mixed with EGTA buffer to obtain pCa ∼7.39. The signals are an average of 7–10 experimental runs, and the solid line shows the fit to a single exponential equation. The experimental conditions are described in detail under “Experimental Procedures.” The signals are offset along the ordinate for easier viewing. The means ± S.E. are shown in Table 1 (n = 3–5).

When pre-formed cTn complexes were mixed with other TF proteins (i.e. Tm and actin), the A8V and D145E mutations produced opposing effects on the rate of Ca2+ dissociation from cTnC (Fig. 2B). The koff for TFs containing A8V cTnC was 79.80/s, which was statistically slower than TFs containing WT cTnC, whereas the koff for TFs containing D145E cTnC was faster than WT TFs (129.18/s versus 95.78/s) (Table 1). Since both mutations increased the cTnC Ca2+ affinity in TFs suggests that the on-rate for the D145E mutant may be ∼1.5× faster than the WT (Table 1). TFs containing E134D cTnC did not show any significant differences in pCa50 or koff when compared with WT TFs.

Fig. 3A shows experiments that measure the rate of cTnC Ca2+ dissociation from TFs in the presence of S1 and ATP. A8V cTnC (75.28/s) was the only mutant that showed a slower koff for Ca2+ compared with the WT protein (139.12/s) (Table 1). Fig. 3B shows the rate of cTnC Ca2+ dissociation from TFs in the presence of S1 and the absence of ATP. The Ca2+ dissociation was slower (∼20%) for TFs containing A8V and D145E cTnC when compared with the WT (Fig. 3B and Table 1). In the presence of S1 (±ATP), TFs containing the E134D mutant were not statistically different from the WT controls.

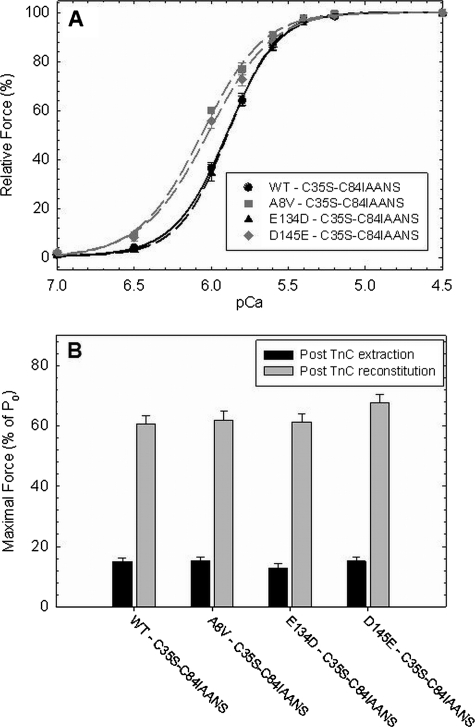

Fig. 4 shows the effect of HCM-cTnC mutants labeled with IAANS at Cys-84 on the Ca2+ sensitivity of force development and the recovery of maximal force in skinned cardiac fibers. These experiments were performed to determine whether the labeled cTnCs affect the Ca2+ binding properties in a more physiological system. To address discrepancies between the Ca2+ affinity measured in the reconstituted TF system and the Ca2+ sensitivity values measured in reconstituted skinned fibers, the WT, A8V, E134D, and D145E IAANS-labeled cTnCs were incorporated into skinned cardiac fibers, and the pCa versus force relationships were obtained. The labeled A8V (pCa50 = 6.07 ± 0.01) and D145E (pCa50 = 6.03 ± 0.03) cTnC mutants significantly increased the Ca2+ sensitivity of force (+0.17 and +0.13 pCa units, respectively) compared with the WT control (pCa50 = 5.90 ± 0.01) (Fig. 4A and Table 2). The pCa50 of the labeled E134D cTnC mutant was the same as that observed for the labeled WT control (Table 2). The recovered maximal force was not significantly different among all fibers reconstituted with the labeled HCM-cTnC mutants and the WT (Fig. 4B and Table 2).

FIGURE 4.

Ca2+ sensitivity of force development and maximal force recovery in reconstituted skinned cardiac fibers. cTnC-depleted fibers were reconstituted with WT- or HCM-cTnCs containing C35S-C84-IAANS and the Ca2+ dependence of force (A) and maximal force recovery (B) were measured. The mean maximal force/cross-sectional area was measured before cTnC extraction in pCa 4.0 is 46.61 ± 0.87 kN/m2. Note that the relative maximal force was measured after native cTnC extraction (before incubation with exogenous cTnC) and after reconstitution with WT- or HCM-cTnCs. The means ± S.E. are shown in Table 2 (n = 6 - 7).

TABLE 2.

Summary of the skinned-fiber data

| cTnC | pCa50 | ΔpCa50a | nHill | % Maximal force recovered | No. experiments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT − C35S-C84IAANS | 5.90 ± 0.01 | 2.66 ± 0.20 | 60.7 ± 2.6 | 6 | |

| A8V − C35S-C84IAANS | 6.07 ± 0.01b | +0.17 | 2.19 ± 0.11 | 62.0 ± 2.8 | 6 |

| E134D − C35S-C84IAANS | 5.89 ± 0.02 | −0.01 | 2.86 ± 0.19 | 61.4 ± 2.5 | 7 |

| D145E − C35S-C84IAANS | 6.03 ± 0.03b | + 0.13 | 2.12 ± 0.11b | 67.6 ± 3.0 | 6 |

| WTc | 5.66 ± 0.01 | 2.74 ± 0.19 | 59.1 ± 2.3 | 8 | |

| A8Vc | 6.02 ± 0.01b | +0.36 | 2.68 ± 0.18 | 72.4 ± 2.7b | 9 |

| E134Dc | 5.68 ± 0.01 | +0.02 | 2.82 ± 0.16 | 58.4 ± 2.1 | 7 |

| D145Ec | 5.90 ± 0.01b | +0.24 | 2.73 ± 0.17 | 70.3 ± 1.4b | 8 |

a ΔpCa50 = HCM cTnC pCa50 − WT cTnC pCa50.

b p < 0.05 compared to their respective WT (X ± S.E.).

c Data are from Landstrom et al. (4).

DISCUSSION

The A8V and D145E HCM-associated mutations increase the apparent Ca2+ affinity of cTnC in several functional assays; however, the mechanisms by which the mutations affect the cTnC Ca2+ affinity are different. The A8V mutation does not directly increase the Ca2+ affinity of cTnC or the cTn complex (8). Inclusion of A8V cTnC into TFs causes an increase in the Ca2+ affinity. However, the Ca2+ affinity did not approach the Ca2+ sensitivity seen in skinned fibers until the addition of S1 under conditions that favor rigor cross-bridges. We propose that by affecting protein-protein interactions within the TF and imposing a heightened sensitization response to cross-bridges, the A8V mutation primarily increases the Ca2+ sensitivity by indirect effects on cTnC. On the other hand, the D145E mutation both directly and indirectly increases the Ca2+ affinity of cTnC by, 1) directly increasing the Ca2+ affinity of isolated cTnC, 2) altering the response to protein-protein interactions within the cTn complex (indirect), and 3) altering the response to strong cross-bridge binding (indirect).

In a previous report, the ΔpCa50 values for skinned fibers reconstituted with A8V and D145E cTnC were +0.36 and +0.24, respectively (cf. Table 2) (4, 8). In the present study we incorporated the WT and HCM-cTnC mutants containing the C35S substitution and C84-IAANS label into skinned cardiac fibers. The trend toward increased Ca2+ sensitivity of force development persisted as in our previous report (Fig. 4 and Table 2, lines 1–4), but the ΔpCa50 values (Table 2, lines 5–8) were slightly reduced in comparison to the previous results, which used the unlabeled cTnC mutants (4). Clearly, the C35S mutation and the IAANS label interfere with the functional profile of these mutants. However, as shown in Fig. 1B and Table 1, the ΔpCa50 values obtained in the presence of rigor cross-bridges in solution (+0.23 for A8V and +0.14 for D145E) more closely approached the ΔpCa50 values seen in skinned fibers (+0.17 for A8V and +0.13 for D145E) reconstituted with the labeled cTnC mutants. Most of the mutations in Tm, cTnT, and cTnI that are related to HCM or dilated cardiomyopathy require the other TF proteins (i.e. actin-Tm-Tn) to better reproduce the changes in the Ca2+ sensitivity observed in fibers or reconstituted systems (34). Therefore, our data are consistent with the above because we show that HCM mutations in cTnC that affect the function of the N-domain regulatory site need a higher level of complexity (i.e. the interaction between thick and thin filaments) to better match the ΔpCa50 values of tension obtained in skinned fibers.

Here we report for the first time the effects of IAANS-labeled cTnC mutants on the Ca2+ off-rates from reconstituted filaments and the Ca2+ sensitivity of force development in reconstituted skinned cardiac fibers. However, these systems are not without limitations such that in the absence of an animal model, reconstituted systems do not have the ability to modify the regulation of transcription factors involved in the hypertrophic signaling pathway, thereby preventing one from observing differences due to changes in Ca2+ handling, protein isoform switching, cardiac hypertrophy, and diastolic function.

Despite these limitations, our kinetic data coincide with the results of Davis et al. (17) as our data follow the same trends. Davis et al. (17) used a cTnC triple mutant (C35S, T53C, and C84S) with a single probe at Cys-53, the N-capping residue for helix C. The major differences between the data from the two groups lie in the measured Ca2+ off-rate of WT cTnC in cTn and in TFs + S1. The Ca2+ off-rates measured with the triple mutant configuration were twice as fast as our values measured from cTn and TFs + S1, e.g. 41.9/s for cTn and 13.0/s for TFs + S1 (17), compared with 18.95 and 6.93/s in our experiments. It is difficult to determine which configuration is best-suited for performing these measurements. Nevertheless, measurements performed with unlabeled native cTn purified from cardiac muscle showed a Ca2+ off-rate of 19.6/s from site II of cTnC (35), which correlates well with the value of 18.95/s reported here for cTn containing the recombinant WT protein.

In the cTn complex, the A8V mutant was the only case showing a decrease in the estimated kon (0.62 × 108 m−1·s−1 compared with 0.94 × 108 m−1·sec−1 for the WT) while also displaying a statistically significant lower off-rate (16.31/s compared with 18.95/s for the WT) (Table 1). These results contradict the expectation that the koff should be faster as it had a lower Ca2+ affinity (i.e. lower pCa50 value). When A8V cTnC was evaluated in reconstituted TFs, the pCa50 was increased, and the koff was reduced in a similar proportion compared with the WT (Table 1); thus, the estimated Ca2+ on rate was similar to the WT. On the other hand, with D145E cTnC, the koff and pCa50 increased in TFs compared with the WT. The calculated kon is 60% greater than the WT control and leads to the conclusion that the increase in the on rate prevents a large (e.g. >+0.08 pCa units) net alteration in the overall Ca2+ affinity.

We are learning that a more complete contractile apparatus better recapitulates the cellular phenotype produced by mutations in regulatory proteins (11, 20, 32, 34). As shown by Güth and Potter (18) and others (36, 37), when ADP is added to the solution, the equilibrium shifts toward strongly bound cross-bridge states, and the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity increases. Others (18, 36–39) have shown that adding Pi to the solution shifts the equilibrium toward detached cross-bridge states and a decrease in the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity. Therefore, we added S1 to TFs in the presence and absence of ATP to investigate the effects of two different cross-bridge states on the Ca2+ affinity of TFs containing the HCM mutants.

The values for the Ca2+ affinity of TFs in the presence of S1 and ATP (i.e. conditions of cycling cross-bridges) were not very different from the values seen with TFs alone (cf. Table 1). It is possible that our solution measurements performed under no external load generate a higher population of weakly bound cross-bridges in comparison to the estimated 55% of strong bridges under isometric conditions in muscle fibers (38); therefore, with ATP present, we may simply recapitulate the effects of TFs alone. The koff measured from WT TFs in the presence of S1 and ATP (139.12/s) was ∼1.5 times faster than TFs alone (95.78/s). Although these measurements were performed at high ionic strength (∼210 mm), we have seen that under such conditions, cycling cross-bridges (by measuring the specific ATPase activity) do exist and, therefore, may affect the kinetics of calcium binding (data not shown). Based on the above observations, alterations in the kinetics of Ca2+ binding to the N-terminal domain of cTnC can occur without affecting the Ca2+ affinity.

Steady-state measurements of WT TFs + S1 in the absence of ATP revealed an increase in the Ca2+ affinity over that measured in the presence of ATP (+0.4 pCa units, cf. Table 1). As discussed earlier, this result is expected as strong cross-bridges exert a substantial influence on the cTnC N-domain Ca2+ binding affinity. However, TFs containing the A8V and D145E HCM-cTnC mutants were clearly affected more than WT by the presence of strong cross-bridges (+0.50 and +0.51 pCa units, respectively; cf. Table 1). From these data it appears that the Ca2+ sensitivity of myofilaments containing A8V cTnC is dependent on two parameters; that is, the intrinsic properties of the TF and the effect of strong cross-bridges. These two factors apparently act synergistically to yield the level of Ca2+ sensitization seen in the reconstituted filaments i.e. TF, TF +S1 (±ATP), and presumably also in skinned fibers.

In isolated cTnC and cTn, the D145E mutation led to a consistent increase in the Ca2+ affinity compared with the WT (8). The ΔpCa50 for TFs (alone) and TFs + S1 + ATP containing the D145E mutant decreased in comparison to the D145E cTn complex (Table 1). Therefore, at this higher level of complexity, there was no enhancement of the cTnC Ca2+ affinity. However, when experiments were performed with S1 in the absence of ATP, strong cross-bridges further potentiated the Ca2+-sensitizing effect and better approached the ΔpCa50 values obtained in skinned fibers (Tables 1 and 2). The location of the D145E mutation in the C-domain of cTnC is in close proximity to regions of cTnT that convey the cross-bridge influence on cTnC Ca2+ binding (40). In addition, it has been shown that at low Ca2+ concentrations, the D145E cTnC mutant has a much lower affinity than WT for the cTnI128–180 peptide (41).

Incorporating the A8V and D145E mutants into TFs in the presence of strong cross-bridges decreased the cTnC Ca2+ off-rate by ∼20% when compared with the WT control. It is possible that a slower cTnC Ca2+ off-rate is a major contributor to the clinical diastolic dysfunction seen in these patients (22, 27, 42, 43). In support of this premise, an animal model engineered with the HCM-linked R145G cTnI mutation increases the Ca2+ sensitivity of contraction and causes a delay in the decay phase of the Ca2+ transient that is analogous to a decrease in the Ca2+ off-rate (44). It will be important to confirm this by developing animal models bearing HCM-linked cTnC mutations.

At the level of cTn, there was no significant change in the Ca2+ binding properties in complexes containing the C84Y mutant and its respective control (WT-C84S). The E134D cTnC mutant was also analyzed for its Ca2+ binding properties, and it was found that in cTn, TFs, and TFs + S1, the pCa50 and koff values were very similar to the WT counterparts. In addition, the Ca2+ sensitivity of force development, maximal force, and ATPase activation were unaltered (4, 8). These observations may indicate that this mutation is not responsible for the clinical presentation of HCM in the proband. Notably, the patient was found to be genotype-negative for eight other screened genes (4).

Assigning pathogenicity to the E134D mutation is hindered by a lack of family segregation studies and linkage analysis (4). Although such information can be extremely valuable, it is often difficult to obtain. Therefore, together with Hershberger et al. (45), we reason that integration of molecular, clinical, and functional data can contribute to identifying the significance of mutations. We note that the L29Q cTnC mutation allegedly associated with HCM was also identified in a single patient; however, the functional studies reported by two groups (11, 12) suggests that this is a benign mutation. Based on the above, it is possible that other mutations were present in the patient such that, in combination with the E134D mutation, they had synergistic effects (46). Finally, the E134D mutation may disrupt other functional parameters of muscle contraction not studied here, e.g. sarcomeric protein phosphorylation (47).

In the context of structure, the A8V and D145E mutations are present in two different domains of cTnC, but they share strikingly similar functional characteristics. The mechanisms of increased Ca2+ sensitivity for these two mutants differs with regard to the influence of the other thin filament proteins and cross-bridges. Interestingly, A8V is located in the N-helix, which is known for its modulatory role in skeletal TnC Ca2+ binding (48, 49). Previous studies have shown that the N-helix can influence Ca2+ binding to the carboxyl-terminal sites III and IV. These effects on Ca2+ affinity were detected after the truncation of the first 14 N-terminal residues of cTnC, and the results suggested that an interdomain interaction or influence by the N-helix exists (49, 50). Molecular modeling using the PDB file 1J1E indicates that the N-helix is uniquely situated between Ca2+ binding sites II and IV. The N-helix residue Lys-6 is 6.8 Å away from the side chain of Glu-66, located in site II. Moreover, residue Lys-142 in site IV is 6.3 Å away from residue Met-1 in the N-helix (40). Because the N-helix is connected to the rest of the N-domain through a flexible loop (amino acids 11–13), it may be inherently flexible and capable of adopting a range of conformations. Therefore, the N-helix may assist in modulating Ca2+ binding to both domains. Because the D145E mutation is located in such close proximity to the N-helix, it may manifest its functional changes in a similar manner as the A8V mutation, which is located within the N-helix. Further experiments need to be conducted to examine the importance of the charged and non-polar residues located in the N-helix and whether the N-helix may serve as an interface for communication between Ca2+ binding sites II and IV.

The main conclusion from this study is that the A8V and D145E mutants alter the Ca2+ sensitivity of myofilaments through different routes. A8V cTnC has a greater Ca2+ affinity than WT cTnC when incorporated into TFs, and this effect is enhanced by the formation of strong cross-bridges. On the other hand, the D145E mutation directly affects the Ca2+ affinity in the isolated state and in the cTn complex; however, within TFs, the increase in Ca2+ affinity is less dramatic and is enhanced by the formation of strong cross-bridges. Kinetically, the most significant differences observed with the mutants occur in the measured Ca2+ off-rate rather than the on rate. This suggests that the A8V and D145E mutations are capable of altering the muscle relaxation properties by contributing to the occurrence of impaired function during diastole in HCM. This type of study provides insight into the mechanism by which HCM mutations alter function and may be useful for further development of tailored therapeutic interventions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Hector Barrabin and Helena Scofano for use of the Applied Photophysics stopped-flow apparatus and D. M. Araujo for preparation of S1 used in the stopped-flow rigor experiments.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants AR050199, HL042325, and NS064821 (to J. D. P.). This work was also supported by postdoctoral fellowships from the American Heart Association AHA 0825368E (to J. R. P.) and AHA 09POST2300030 (to M. S. P.) and Brazilian agencies Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa Carlos Chagas Filho do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ) (to M. M. S.) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (to M. M. S. and D. P. R., both affiliated with the Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia de Biologia Estrutural e Bioimagem).

- HCM

- hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- Tn

- troponin

- cTn

- cardiac Tn

- TF

- thin filament

- S1

- subfragment 1

- IAANS

- iodoacetamido)anilino]naphthalene-6-sulfonic acid

- NTA

- nitrilotriacetic acid

- Tm

- tropomyosin.

REFERENCES

- 1. Maron B. J. (2007) Cardiol. Clin. 25, 399–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marian A. J. (2008) Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 23, 199–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alcalai R., Seidman J. G., Seidman C. E. (2008) J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 19, 104–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Landstrom A. P., Parvatiyar M. S., Pinto J. R., Marquardt M. L., Bos J. M., Tester D. J., Ommen S. R., Potter J. D., Ackerman M. J. (2008) J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 45, 281–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Willott R. H., Gomes A. V., Chang A. N., Parvatiyar M. S., Pinto J. R., Potter J. D. (2010) J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 48, 882–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Herzberg O., James M. N. (1985) Nature 313, 653–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Holroyde M. J., Robertson S. P., Johnson J. D., Solaro R. J., Potter J. D. (1980) J. Biol. Chem. 255, 11688–11693 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pinto J. R., Parvatiyar M. S., Jones M. A., Liang J., Ackerman M. J., Potter J. D. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 19090–19100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hoffmann B., Schmidt-Traub H., Perrot A., Osterziel K. J., Gessner R. (2001) Hum. Mutat. 17, 524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schmidtmann A., Lindow C., Villard S., Heuser A., Mügge A., Gessner R., Granier C., Jaquet K. (2005) FEBS J. 272, 6087–6097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dweck D., Hus N., Potter J. D. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 33119–33128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Neulen A., Stehle R., Pfitzer G. (2009) Basic Res. Cardiol 104, 751–760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liang B., Chung F., Qu Y., Pavlov D., Gillis T. E., Tikunova S. B., Davis J. P., Tibbits G. F. (2008) Physiol. Genomics 33, 257–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Putkey J. A., Liu W., Lin X., Ahmed S., Zhang M., Potter J. D., Kerrick W. G. (1997) Biochemistry 36, 970–978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Johnson J. D., Collins J. H., Robertson S. P., Potter J. D. (1980) J. Biol. Chem. 255, 9635–9640 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Potter J. D., Gergely J. (1975) J. Biol. Chem. 250, 4628–4633 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Davis J. P., Norman C., Kobayashi T., Solaro R. J., Swartz D. R., Tikunova S. B. (2007) Biophys. J. 92, 3195–3206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Güth K., Potter J. D. (1987) J. Biol. Chem. 262, 13627–13635 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang Y., Kerrick W. G. (2002) J. Appl Physiol. 92, 2409–2418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tikunova S. B., Liu B., Swindle N., Little S. C., Gomes A. V., Swartz D. R., Davis J. P. (2010) Biochemistry 49, 1975–1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zot A. S., Potter J. D. (1989) Biochemistry 28, 6751–6756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Miller T., Szczesna D., Housmans P. R., Zhao J., de Freitas F., Gomes A. V., Culbreath L., McCue J., Wang Y., Xu Y., Kerrick W. G., Potter J. D. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 3743–3755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Knollmann B. C., Blatt S. A., Horton K., de Freitas F., Miller T., Bell M., Housmans P. R., Weissman N. J., Morad M., Potter J. D. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 10039–10048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lang R., Gomes A. V., Zhao J., Housmans P. R., Miller T., Potter J. D. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 11670–11678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Iorga B., Blaudeck N., Solzin J., Neulen A., Stehle I., Lopez Davila A. J., Pfitzer G., Stehle R. (2008) Cardiovasc. Res. 77, 676–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stehle R., Solzin J., Iorga B., Poggesi C. (2009) Pflugers Arch. 458, 337–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li Y., Charles P. Y., Nan C., Pinto J. R., Wang Y., Liang J., Wu G., Tian J., Feng H. Z., Potter J. D., Jin J. P., Huang X. (2010) J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 49, 402–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang R., Zhao J., Potter J. D. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 30773–30780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Potter J. D. (1982) Methods Enzymol. 85, 241–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Weeds A. G., Taylor R. S. (1975) Nature 257, 54–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pardee J. D., Spudich J. A. (1982) Methods Enzymol. 85, 164–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dweck D., Reynaldo D. P., Pinto J. R., Potter J. D. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 17371–17379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dweck D., Reyes-Alfonso A., Jr., Potter J. D. (2005) Anal. Biochem. 347, 303–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Robinson P., Griffiths P. J., Watkins H., Redwood C. S. (2007) Circ. Res. 101, 1266–1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Robertson S. P., Johnson J. D., Potter J. D. (1981) Biophys. J. 34, 559–569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cooke R., Pate E. (1985) Biophys. J. 48, 789–798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kawai M., Güth K., Winnikes K., Haist C., Rüegg J. C. (1987) Pflugers Arch. 408, 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Regnier M., Morris C., Homsher E. (1995) Am. J. Physiol. 269, C1532–1539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Linari M., Caremani M., Piperio C., Brandt P., Lombardi V. (2007) Biophys. J. 92, 2476–2490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Takeda S., Yamashita A., Maeda K., Maéda Y. (2003) Nature 424, 35–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Swindle N., Tikunova S. B. (2010) Biochemistry 49, 4813–4820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tardiff J. C., Hewett T. E., Palmer B. M., Olsson C., Factor S. M., Moore R. L., Robbins J., Leinwand L. A. (1999) J. Clin. Invest. 104, 469–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Knollmann B. C., Potter J. D. (2001) Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 11, 206–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wen Y., Pinto J. R., Gomes A. V., Xu Y., Wang Y., Wang Y., Potter J. D., Kerrick W. G. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 20484–20494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hershberger R. E., Pinto J. R., Parks S. B., Kushner J. D., Li D., Ludwigsen S., Cowan J., Morales A., Parvatiyar M. S., Potter J. D. (2009) Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2, 306–313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Girolami F., Ho C. Y., Semsarian C., Baldi M., Will M. L., Baldini K., Torricelli F., Yeates L., Cecchi F., Ackerman M. J., Olivotto I. (2010) J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 55, 1444–1453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Solaro R. J. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 26829–26833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chandra M., da Silva E. F., Sorenson M. M., Ferro J. A., Pearlstone J. R., Nash B. E., Borgford T., Kay C. M., Smillie L. B. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 14988–14994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Smith L., Greenfield N. J., Hitchcock-DeGregori S. E. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 9857–9863 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Grabarek Z., Leavis P. C., Gergely J. (1986) J. Biol. Chem. 261, 608–613 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]