Abstract

Electronegative LDL (LDL(−)) is a minor subfraction of modified LDL present in plasma. Among its atherogenic characteristics, low affinity to the LDL receptor and high binding to arterial proteoglycans (PGs) could be related to abnormalities in the conformation of its main protein, apolipoprotein B-100 (apoB-100). In the current study, we have performed an immunochemical analysis using monoclonal antibody (mAb) probes to analyze the conformation of apoB-100 in LDL(−). The study, performed with 28 anti-apoB-100 mAbs, showed that major differences of apoB-100 immunoreactivity between native LDL and LDL(−) concentrate in both terminal extremes. The mAbs Bsol 10, Bsol 14 (which recognize the amino-terminal region), Bsol 2, and Bsol 7 (carboxyl-terminal region) showed increased immunoreactivity in LDL(−), suggesting that both terminal extremes are more accessible in LDL(−) than in native LDL. The analysis of in vitro-modified LDLs, including LDL lipolyzed with sphingomyelinase (SMase-LDL) or phospholipase A2 (PLA2-LDL) and oxidized LDL (oxLDL), suggested that increased amino-terminal immunoreactivity was related to altered conformation due to aggregation. This was confirmed when the aggregated subfractions of LDL(−) (agLDL(−)) and oxLDL (ag-oxLDL) were isolated and analyzed. Thus, Bsol 10 and Bsol 14 immunoreactivity was high in SMase-LDL, ag-oxLDL, and agLDL(−). The altered amino-terminal apoB-100 conformation was involved in the increased PG binding affinity of agLDL(−) because Bsol 10 and Bsol 14 blocked its high PG-binding. These observations suggest that an abnormal conformation of the amino-terminal region of apoB-100 is responsible for the increased PG binding affinity of agLDL(−).

Keywords: Antibodies, Atherosclerosis, Cholesterol Metabolism, Low Density Lipoprotein (LDL), Proteoglycan Structure, Aggregated LDL, Apolipoprotein B Immunoreactivity, Electronegative LDL

Introduction

Apolipoprotein B-100 (apoB-100)6 is the major apolipoprotein in LDL, present as a single copy per lipoprotein particle. Its large size (4536 amino acids) and the tight association with lipids made the study of its structure a major challenge. Computerized homology alignments and characterization of secondary structure for amphipathic domains indicate that apoB-100 has a supramolecular structure where five domains with α or β structure are arranged in the following order from the amino- to the carboxyl-terminal: N-βα1-β1-α2-β2-α3-C (1). This so called pentapartite structure has been used widely as model for the structure of apoB-100. However, an important structural feature of apoB-100 is its low conformational stability (2). ApoB-100 can be viewed as a dynamic, flexible molecular string that is able to adopt different conformations according to the size of the lipid droplet to which it is attached (2).

The structure of apoB-100 determines many important characteristics of LDL, such as binding affinity to receptors that mediate the cellular uptake, susceptibility to enzymatic or oxidative modifications, or propensity to particle aggregation and binding to arterial wall proteoglycans (PGs) (3). Therefore, an altered structure of apoB-100 is expected to affect the metabolic fate of LDL driving it as a main player in atherogenesis.

An in vivo modified LDL subfraction present in plasma, named electronegative LDL (LDL(−)) due to its increased negative charge, has been identified and characterized by several groups. LDL(−) represents 1 to 10% of total LDL but an increased proportion of LDL(−) has been observed in hypercholesterolemia (4), hypertriglyceridemia (5), diabetes (6), and severe renal disease (7). In these pathologic situations, there is a modified apoB-100 structure (8–10). In vitro studies have shown that LDL(−) has atherogenic properties because it induces inflammatory cytokine production, cytotoxicity, and apoptosis in vascular and blood cells (11–14). ApoB-100 in LDL(−) possesses impaired affinity to the LDL receptor (15, 16). Moreover, LDL(−) has higher affinity to arterial PG than native LDL (17). Some of these atherogenic characteristics of LDL(−) are likely related to an altered structure of the LDL particle and specifically to changes of the apoB-100 conformation. Relatively little is known concerning apoB-100 structure in LDL(−), and different studies have led to contradictory conclusions. Some studies have described that LDL(−) presents alterations of apoB-100 conformation, particularly, secondary structure loss (18, 19). In contrast, secondary structure analysis by circular dichroism performed by our group did not find clear differences between LDL(−) and native LDL (16, 17). In the present study, we analyzed possible alterations in the exposure of specific apoB-100 epitopes with the aim of revealing apoB-100 conformation differences between LDL(−) and native LDL. Specifically, we analyzed the immunoreactivity of LDL(−) and native LDL with a panel of 28 well-characterized anti-apoB-100 mAbs. Results showed important differences in the conformation of apoB-100 in LDL(−) affecting both the amino- and carboxyl-terminal ends. These changes were related to aggregation of LDL particles and modulated the affinity to arterial PGs.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

All reagents were purchased from Sigma unless otherwise stated.

Isolation of LDL Subfractions

The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee, and all volunteers gave informed consent. Human LDL (density range, 1.019–1.050 g/ml) was isolated from plasma of healthy normolipemic volunteers by sequential ultracentrifugation in KBr gradients at 4 °C in the presence of 1 mm EDTA and 2 μm butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT). LDL was subfractionated into native electropositive LDL (LDL(+)) and LDL(−) by stepwise anion-exchange chromatography, as described (20). LDL(−) or oxidized LDL (oxLDL) were subjected to gel-filtration chromatography to separate aggregated (agLDL) and nonaggregated (nagLDL) fractions. Gel-filtration chromatography was performed using two on-line connected Superose 6 columns in an AKTA-FPLC system (GE Healthcare), as described previously (21). One ml of LDL(+), LDL(−), or oxLDL at 1 g protein/liter was loaded into the columns and was eluted with buffer 10 mm Tris, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 2 μm BHT, pH 7.4, at a flow of 1 ml/min. Chromatographic fractions were collected and concentrated by centrifugation with Amicon microconcentrators (10,000 MWCO, Amicon Ultra-4, Millipore).

Modification of LDL

Oxidation of LDL

LDL was oxidized by incubation of PBS-dialyzed LDL(+) (0.25 g protein/liter) with CuSO4 (10 μm) at room temperature overnight. To stop the reaction, oxLDL was dialyzed against buffer A (10 mm Tris, 1 mm EDTA, pH 7.4) containing 20 μm BHT.

Lipolysis of LDL

LDL(+) was lipolyzed with secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2) or with sphingomyelinase (SMase), as described (22, 23). Briefly, LDL(+) (0.5 g protein/liter) was incubated for 2 h at 37 °C with sPLA2 from bee venom (15 μg/liter) or SMase from Staphylococcus aureus (20 units/liter) in 5 mm HEPES, 5 mm CaCl2, 2 mm MgCl2, 140 mm NaCl, pH 7.4, with 45 g/liter fatty acid-free BSA and 2 μm BHT. Afterward, enzymatic reactions were stopped with EDTA 10 mm and lipolyzed LDLs were reisolated by ultracentrifugation and dialyzed against buffer A containing 2 μm BHT.

Aggregation of LDL by Intense Agitation

LDL(+) (1 g protein/liter in buffer A) was vortexed for 10 s with a Table vortex (Vortex-Genie-2, Scientific Industries) at full speed.

Characterization of LDL

Total cholesterol, triglyceride, apoB-100 (Roche Diagnostics), phospholipids, and nonesterified fatty acids (Wako Chemicals) were measured in LDLs by commercial methods adapted to a Hitachi 917 autoanalyzer (20). Total protein content was determined by the bicinchoninic acid method (Pierce). Phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin were quantified by normal phase HPLC in a Gold System chromatograph (Beckman) after lipid extraction as described (22). The oxidative level of LDL was estimated by measuring the absorbance at 234 nm of the phosphatidylcholine peak (which corresponds to oxidized phosphatidylcholine) and expressed as the 205/234 nm ratio (24). LDL aggregation level was determined by measuring the absorbance at 450 nm and by nondenaturing acrylamide gradient gel electrophoresis as described (5).

Anti-apoB-100 Monoclonal Antibodies

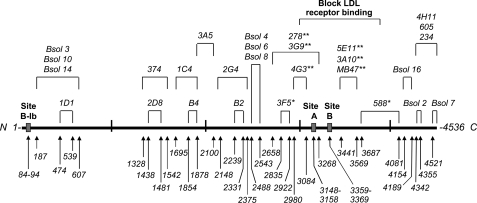

Anti-apoB-100 mAbs were obtained by immunizing mice with human LDL or apoB-100 (Bsol series). The specificity of these mAbs and the identification of their epitopes have been described previously (25, 26). An epitope map is shown below (see Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Map of apoB-100 epitopes recognized by mAbs that have been used in the present study. The primary sequence of apoB-100 is represented as a thick solid line. The position recognized by each mAb (25, 26) and the PG binding sites (39, 40) are indicated and expressed as apoB-100 residues. *, mAb partially blocks binding of LDL to the LDL receptor, and **, mAb totally blocks binding. N, N-terminal; C, C-terminal.

Competitive Immunoassay for apoB-100

The competitive immunoassay to determine the reactivity of the anti-apoB-100 mAbs with LDLs was performed as described previously (27). Briefly, Immulon 2 HB polystyrene microtiter strips (Thermo Labsystems) were coated overnight with 50 μl of LDL(+) (25 mg protein/liter). Wells were washed three times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 and three times with PBS and blocked with PBS containing 1% BSA (PBS-BSA). Anti-apoB-100 mAbs, appropriately diluted in PBS-BSA (50 μl), were mixed with 50 μl of serial dilutions (in PBS-BSA) of tested LDLs, incubated for 2 h, and 50 μl of the mixture was transferred to the LDL-coated, BSA-blocked microtiter wells. After an overnight incubation, the wells were washed as above and incubated for 2 h with 50 μl of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (GE Healthcare) or anti-rat IgG for antibodies B2 and B4 (Kirkegaard Perry Laboratories). After washing as above, 50 μl of tetramethylbenzidine substrate was added to the wells, and absorbance at 655 nm was measured after 30 min of incubation.

The assay was based on the competition between LDL(+) immobilized in wells and different concentrations of the tested sample for each antibody at its optimal dilution previously determined as described (28). Maximum binding (Bmax) was determined in wells in which no competing antigen was added. The results are expressed as B/Bmax ratio. Each value is the mean of two measurements (C.V. < 10%). In each immunoassay, LDL(+) was studied in parallel with the other samples as a control.

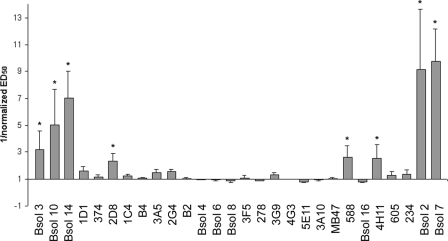

Immunoreactivity is usually expressed as ED50, which represents the protein concentration required for 50% inhibition of the maximum binding of mAbs. The LDL(−) ED50 value for each mAb was normalized to its LDL(+) ED50 value (LDL(−)/LDL(+)), considering that ED50 of LDL(+) is 1. Fig. 2 represents the inverse of normalized ED50 (1/normalized ED50) to show positive values when the immunoreactivity of LDL(−) was increased compared with LDL(+) and negative values when reactivity was decreased.

FIGURE 2.

Immunoreactivity of LDL(−) with anti-apoB-100 mAbs relative to LDL(+). LDL(+) and LDL(−) were isolated from total LDL of normolipemic subjects, and their immunoreactivities were evaluated by competitive immunoassay with 28 anti-apoB-100 mAbs. The immunoreactivity of LDL(−) particles was expressed as 1/normalized ED50 values, where ED50 represents the LDL protein concentration required for 50% inhibition of maximum binding of mAbs. 1/ED50 values of LDL(−) in each experiment have been normalized to its respective LDL(+), which was assigned a value of 1 for each mAb. Results are expressed as means ± S.E. (n = 3). *, statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) of LDL(−) reactivity versus LDL(+).

Inhibition of LDL-PG Binding by mAbs

LDLs (100 μl at 0.3 g protein/liter) (LDL(+), nagLDL(−), and agLDL(−)) were incubated with IgG purified mAbs (Bsol 10, Bsol 14, Bsol 2, and Bsol 7) at a molar ratio of 1:1 (apoB-100:mAb) at 20 °C for 2 h. Then, PG binding affinity was determined by analytical PG affinity chromatography as described (17). Briefly, LDL was bound to the human aortic PG column using buffer PG-A (10 mm HEPES, 2 mm CaCl2, 2 mm MgCl2, pH 7.4) and eluted with a linear gradient of NaCl using buffer PG-B (buffer PG-A plus 250 mm NaCl) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min in an AKTA-FPLC system (GE Healthcare).

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± S.D., except error bars in Fig. 2 that indicate means ± S.E. Differences between LDL subfractions were tested with a Student t test for paired data applying the correction of Welch, using the SPSS 15.0 statistical package.

RESULTS

Immunoreactivity of LDL(−)

The composition of LDL(+) and LDL(−) subfractions was similar to that reported previously (20, 21) (data not shown). To identify specific regions of apoB-100 that may undergo conformation changes between LDL(+) and LDL(−), a panel of 28 well characterized anti-apoB-100 mAbs was used to determine whether individual apoB-100 epitopes are differentially exposed among LDL subfractions. The analysis was performed with a solid-phase competitive immunoassay with specific mAbs for epitopes that range from the amino- to the carboxyl-terminal end of apoB-100 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 2 shows the immunoreactivity of LDL(−) for all of the mAbs compared with LDL(+). LDL(−) showed different immunoreactivity than LDL(+) for some mAbs, which are located at the two extremes of apoB-100 primary structure. In all cases, these mAbs had higher immunoreactivity to LDL(−) than to LDL(+) (positive 1/normalized ED50 values), thereby suggesting that the corresponding epitopes are more exposed in the LDL(−) subfraction. The mAbs with the highest immunoreactivity to LDL(−) (>3-fold compared with LDL(+)) were Bsol 10, Bsol 14 (amino-terminal end; βα1 region), Bsol 2 and Bsol 7 (carboxyl-terminal end; α3 region). These mAbs were assayed in a further 9 independent experiments, and significant differences (p = 0.016, 0.009, 0.006, and 0.001 for Bsol 10, Bsol 14, Bsol 2, and Bsol 7, respectively) between LDL(+) and LDL(−) immunoreactivities were confirmed.

Immunoreactivity of in Vitro Modified LDLs

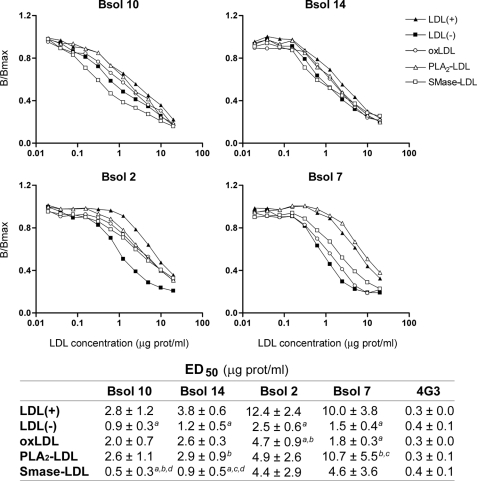

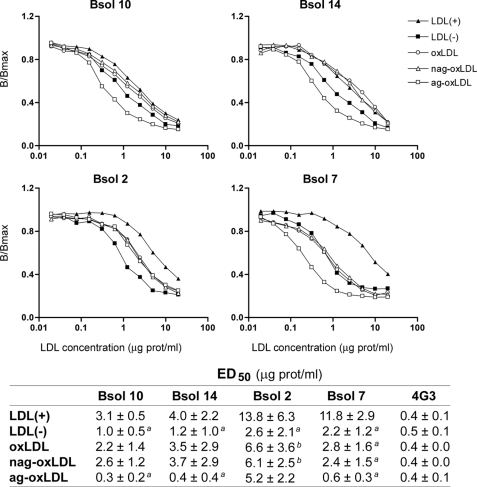

LDL(−) has been suggested to originate from different modifications, including oxidation or sPLA2 and SMase lipolysis (29). To assess whether the differences of apoB-100 conformation in LDL(−) are due to these modifications, the immunoreactivity of some mAbs was evaluated in in vitro modified LDLs. The modified LDLs analyzed were oxLDL, sPLA2-treated LDL (PLA2-LDL) and SMase-treated LDL (SMase-LDL). Biochemical characterization of each modified LDL is shown in the supplemental data (supplemental Table 1S and Fig. 1S). Antibodies used were those with higher immunoreactivity for LDL(−): Bsol 10, Bsol 14, Bsol 2, and Bsol 7. In parallel, 4G3 was also analyzed as a control, as it did not differentiate between LDL(+) and LDL(−).

The immunoreactivity of the modified LDLs is shown in Fig. 3. The graphs show a representative experiment, and the inserted table shows ED50 mean values of three independent samples. Antibodies Bsol 10 and Bsol 14, which recognize an epitope(s) between apoB-100 residues 187 and 607, showed a similar behavior. SMase-LDL had equal (Bsol 14) or even increased (Bsol 10) immunoreactivity compared with LDL(−), whereas the immunoreactivity of Bsol 10/14 with oxLDL and PLA2-LDL was intermediate between that of LDL(+) and LDL(−). The mAbs specific for the apoB-100 carboxyl-terminal region recognize different epitopes: residues close to 4355 (Bsol 2) and residues 4521–4536 (Bsol 7). Bsol 2 reacted similarly with all the in vitro-modified LDLs, and this immunoreactivity was midway between that of LDL(+) and LDL(−). In contrast, Bsol 7 reacted differently with each modified LDL; immunoreactivity of sPLA2-LDL was similar than that of LDL(+), SMase-LDL presented a level intermediate between that of LDL(+) and LDL(−), and oxLDL reactivity was close to that of LDL(−).

FIGURE 3.

Immunoreactivity of in vitro modified LDLs with mAbs Bsol 10, Bsol 14, Bsol 2, and Bsol 7. LDLs were modified with different treatments as indicated under “Experimental Procedures.” The different modified LDLs analyzed were oxLDL, PLA2-LDL, and SMase-LDL. Immunoreactivity of LDL(+) and LDL(−) subfractions was studied in parallel, and 4G3 mAb was analyzed as a control. Graphs show a representative experiment, and the table shows the mean ED50 values of three independent experiments. a, p < 0.05 versus LDL(+); b, p < 0.05 versus LDL(−); c, p < 0.05 versus oxLDL; d, p < 0.05 versus PLA2-LDL.

Overall, the modification that best reproduced the abnormal immunoreactivity of LDL(−) was SMase-LDL. The main characteristic of this enzymatic treatment is to induce particle aggregation (23); then, a possible explanation for the immunological changes observed in LDL(−) could reside in this physical alteration. Hence, the next step was to study the immunoreactivity of aggregated LDL.

Immunoreactivity of Aggregated LDL(−)

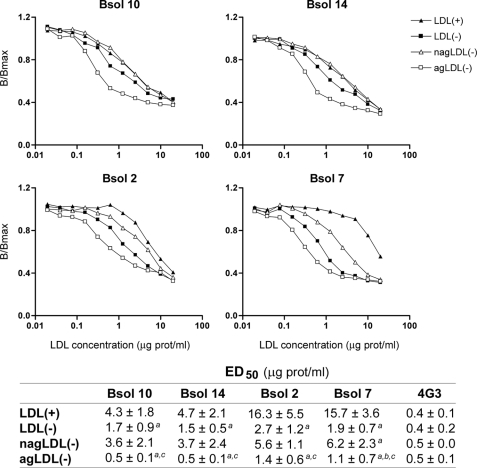

Vortexed LDL presented the same immunoreactivity as LDL(+) (data not shown), indicating that aggregation per se is not responsible for altered immunoreactivity. Because this in vitro modification did not reproduce the immunoreactivity found in SMase-treated LDL, we studied the behavior of in vivo aggregated LDL. In a recent study, we reported that a minor subfraction of in vivo aggregated LDL present in blood is exclusively associated with LDL(−) (21). Therefore, LDL(−) was subfractionated into agLDL(−) and nagLDL(−), and the immunoreactivity of both fractions was assessed.

agLDL(−) presented the highest immunoreactivity with the four tested mAbs (Fig. 4). Bsol 10 and Bsol 14 did not differentiate between nagLDL(−) and LDL(+), whereas nagLDL(−) immunoreactivity was intermediate between that of LDL(+) and LDL(−) with Bsol 2 and Bsol 7. The intermediate immunoreactivity of total LDL(−) between agLDL(−) and nagLDL(−) is explained by the fact that it is a mixture of aggregated and nonaggregated particles (21).

FIGURE 4.

Immunoreactivity of aggregated and nonaggregated LDL(−) fractions with mAbs Bsol 10, Bsol 14, Bsol 2, and Bsol 7. agLDL(−) and nagLDL(−) subfractions were isolated from total LDL(−) by gel-filtration chromatography as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Immunoreactivity of both LDL(−) subfractions, total LDL(−) and LDL(+) were analyzed in parallel. 4G3 mAb was analyzed as a control. Graphs show a representative experiment, and the table shows the mean ED50 values of three independent experiments. a, p < 0.05 versus LDL(+); b, p < 0.05 versus LDL(−); c, p < 0.05 versus nagLDL(−).

However, agLDL(−) could not be responsible for all the characteristics of LDL(−) because Bsol 2 and Bsol 7 competition assays also showed increased immunoreactivity of nagLDL(−) compared with LDL(+). Hence, nagLDL(−) should have conformation changes in addition to those due to aggregation. It has been reported that Bsol 7 shows preferential reactivity for in vitro oxidized LDL (30, 31), and this was confirmed in the current work. Likewise, Bsol 2 that recognizes an adjoining epitope (Fig. 3) also showed increased reactivity with oxLDL. Therefore, epitopes expressed in oxLDL were studied in detail.

Immunoreactivity of Aggregated oxLDL

LDL oxidation promotes particle aggregation (32). To discriminate between conformation alterations owing to aggregation or to oxidation of LDL(−), oxLDL was subfractionated into ag-oxLDL and nag-oxLDL, and their respective immunoreactivities were evaluated. Interestingly, nag-oxLDL was equally immunoreactive as LDL(+) with Bsol 10 and Bsol 14 (Fig. 5). Thus, the epitopes recognized by Bsol 10 and Bsol 14 are more exposed only in aggregated particles, such as ag-oxLDL and agLDL(−), but not in nonaggregated oxidized particles.

FIGURE 5.

Immunoreactivity of aggregated and nonaggregated oxLDL fractions with mAbs Bsol 10, Bsol 14, Bsol 2, and Bsol 7. LDL was oxidized by copper (10 μm CuSO4), and then ag-oxLDL and nag-oxLDL subfractions were isolated by gel-filtration chromatography as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Immunoreactivity of oxLDL subfractions were studied in parallel with total oxLDL, LDL(+), and LDL(−). 4G3 mAb was analyzed as a control. Graphs show a representative experiment, and the table shows the mean ED50 values of three independent experiments. a, p < 0.05 versus LDL(+); b, p < 0.05 versus LDL(−).

Bsol 7 was more reactive with ag-oxLDL, showed similar reactivity with nag-oxLDL, total oxLDL, and LDL(−), and was less reactive with LDL(+). Consequently, the epitope recognized by Bsol 7 is more exposed in oxLDL than in LDL(+), and this is independent of the increased reactivity due to the aggregation process. In contrast, both subfractions of oxLDL had the same immunoreactivity with Bsol 2, which was intermediate between LDL(+) and LDL(−); therefore, Bsol 2 appears to recognize apoB-100 conformational changes that are common to aggregated and nonaggregated oxLDL particles. However, the oxLDL conformation for Bsol 2 epitope does not completely reproduce the LDL(−) conformation because LDL(−) presented a higher immunoreactivity to Bsol 2 than did oxLDL.

It has been described that oxLDL changes its immunoreactivity to Bsol 7 with increasing incubation time (30). Therefore, we analyzed the effect of increased storage time on LDL(−) immunoreactivity. The Bsol 7 reactivity did not change during storage at 4 °C (LDL(−) ED50, 1.9, 1.8, and 2.1 μg protein/ml, at 1, 2, and 4 weeks, respectively). Likewise, storage of LDL(−) at 4 °C did not alter the immunoreactivities of the other mAbs assessed (Bsol 10, Bsol 14, Bsol 2, and 4G3) (data not shown).

Inhibition by mAbs of LDL-PG Binding

Immunoreactivity differences between LDL(−) and LDL(+) could be related to specific LDL(−) functional properties. We have therefore evaluated the effects of these anti-apo-B100 mAbs on the high PG binding affinity of LDL(−). In a previous work, we reported that high binding affinity of LDL(−) to PG depended on its aggregation level, as the particles with highest PG-affinity were more aggregated (17). Our results confirm the complementary point of view that agLDL(−) particles had the highest binding affinity (Fig. 6A). Compared with LDL(+) and nagLDL(−), which presented a narrow well defined peak, agLDL(−) showed a broad peak that eluted at a higher ionic strength.

FIGURE 6.

Affinity chromatography on human aortic PG column of LDL(+), nagLDL(−), and agLDL(−). agLDL(−) and nagLDL(−) were isolated from total LDL(−) by gel-filtration chromatography as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A, LDL(+), nagLDL(−), and agLDL(−) were analyzed on a PG column and eluted with a linear gradient of NaCl (dashed line). B, effect of the mAbs Bsol 10 and Bsol 14 on the PG binding affinity of agLDL(−). LDLs were preincubated with anti-apoB-100 mAbs (at a molar ratio of apoB-100:mAb 1:1) before analysis on the PG column. Figures show a representative chromatogram of three independent experiments.

LDL(+), nagLDL(−), and agLDL(−) were incubated with the four mAbs that were demonstrated to have increased LDL(−) immunoreactivity, and changes in LDL-PG binding were determined. Fig. 6B shows that the PG binding of agLDL(−) was inhibited by the presence of Bsol 10 and Bsol 14, changing the peak shape to one that is similar to the peaks obtained with LDL(+) or nagLDL(−). No inhibitory effect on agLDL(−)-PG binding was observed with Bsol 2 or Bsol 7 (data not shown). LDL(+) and nagLDL(−) presented a similar behavior, with no effect of the four mAbs tested (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

LDL(−) presents atherogenic properties such as impaired LDL receptor affinity (16) and high PG binding (17), which could be a consequence of an altered particle organization. These alterations suggest a different apoB-100 conformation. Recently, our group has detected by two-dimensional NMR differences in the apoB-100 conformation between LDL(+) and LDL(−) particles that affect the basicity of its solvent-exposed lysines (33). These differences could be responsible for the partial loss of affinity of LDL(−) to the LDL receptor. Nevertheless, the information regarding the conformation of apoB-100 in LDL(−) is scarce and contradictory. Some studies (18, 19), but not all (16, 17), have described differences in the secondary structure determined by circular dichroism or distinct global conformation by tryptophan fluorescence. These discrepancies could be attributed to the relative low specificity of such techniques in a macromolecular structure as complex as the LDL particle.

In the present study, the conformation of apoB-100 in LDL subfractions has been analyzed with a sensitive and specific assay that determines the reactivity of mAbs to different apoB-100 epitopes. Twenty-eight mAbs that react along the apoB-100 molecule were tested. We found that the immunoreactivity of LDL(−) to several mAbs was different compared with native LDL. The main differences were located at both extremes of apoB-100 primary structure; the amino-terminal region of apoB-100 in LDL(−) reacted strongly to mAbs Bsol 3, Bsol 10, and Bsol 14, and the carboxyl-terminal end presented the highest increase of immunoreactivity to Bsol 2 and Bsol 7. Some mAbs that recognize other epitopes of the protein sequence, such as 2D8, 588, and 4H11, also bound with higher immunoreactivity to LDL(−) although to a lesser extent than the previous. Overall, our results suggest an altered apoB-100 conformation in LDL(−) that is primarily manifested in the amino-terminal and carboxyl-terminal domains.

In all of the cases where immunoreactivity differences were found, the mAbs were more reactive to LDL(−) than to LDL(+). This could be due to more exposed epitopes on the surface of LDL(−). Interestingly, mAbs with the highest reactivity to LDL(−) were produced using delipidated and resolubilized apoB-100 (Bsol series) as immunogen (28), instead of total LDL. This suggests that apoB-100 in LDL(−) could have carboxyl- and amino-terminal extremes exposed or unfolded as may have solubilized apoB-100. These results are in agreement with data reported by Parasassi et al. (18) who found a decreased fluorescence emission of tryptophan residues of LDL(−), and the authors suggested an exposure to the aqueous environment of these residues in LDL(−) that would be buried in the protein core in LDL(+).

To ascertain whether the altered apoB-100 conformation in LDL(−) was shared with LDLs that had been modified in vitro by mechanisms that have been implicated in the in vivo generation of LDL(−), the immunoreactivity of differently treated LDLs (oxLDL, PLA2-LDL, and SMase-LDL) was determined. SMase-LDL reproduced the best LDL(−). The abnormal reactivity of the amino-terminal region appears to be related to an altered conformation shared by different aggregated particles because Bsol 10 and Bsol 14 recognize with increased reactivity SMase-LDL, ag-oxLDL, and agLDL(−). The exception is vortexed LDL, in which no chemical modification is present. SMase-LDL, ag-oxLDL, and agLDL(−) are known to present alterations in their surface phospholipids, including higher content of ceramide or lysophosphatidylcholine and lower content of sphingomyelin or phosphatidylcholine (16, 21, 23, 34). Taken together, these results indicate that the mechanism inducing aggregation should involve some modification in the lipid composition that would promote increased exposure of amino-terminal epitopes to solvent. Antibodies specific for the carboxyl-terminal end were less specific, as they recognized, with variable reactivity, epitopes present in different modified LDLs.

Our results suggest that differences in mAb reactivity between LDL(+) and LDL(−) are not mainly due to oxidative modification. Abnormal amino-terminal domain conformation of LDL(−) is not related to oxidation since nag-oxLDL did not show increased immunoreactivity. The observation that Bsol 7 binds to LDL(−) and oxLDL with similar reactivity suggests that LDL(−) could present epitopes generated by incipient oxidation. Bsol 7 has been shown to increase its reactivity with oxLDL during the first 6 h of oxidation and then, reactivity diminishes gradually upon prolonged incubation with copper ions (30). Thus, even though we did not detect evidence of increased lipoperoxidation in this study and in others (20), it cannot be ruled out that LDL(−) could have suffered some kind of oxidative process affecting apoB-100 as has been described (35). In our study, LDL(−) had also increased immunoreactivity to Bsol 7, but, in contrast to oxLDL, it did not change with increased storage time (1, 2, and 4 weeks) at 4 °C. This observation suggests that if oxidation does contribute to the increased Bsol 7 reactivity, it is oxidation that occurs in vivo and not during isolation and storage of the LDL.

Different parts of apoB-100 structure have been related to important LDL metabolic functions. One is the LDL receptor-binding site (residues 3359–3369, site B) (36). LDL(−) shows impaired binding to the LDL receptor (16). If the decreased affinity of LDL(−) for the LDL receptor is due to an altered conformation of apoB-100 in the region of the LDL receptor binding site, such a change is not detected by our mAbs that are specific for epitopes in this region of apoB-100 primary structure (residues 2980–3780) (37). Another possibility is that the decreased affinity of LDL(−) for the LDL receptor could be the result of an abnormal ionization state of lysines that are directly implicated in binding (33). A third possibility is that the altered conformation in the carboxyl-terminal domain of apoB-100 of LDL(−) that is detected with mAbs Bsol 2 and Bsol 7 may be responsible for the defective binding of LDL(−) to the LDL receptor. The increased Bsol 2 and Bsol 7 immunoreactivity of LDL(−) would be consistent with a major alteration of the carboxyl-terminal structure of apoB-100 in LDL(−) and with the idea that the α3 helical domain, composed of the last 500 amino acids of apoB-100, is flexible and may adopt different conformations (2). The apoB-100 α3 helical domain has been proposed to be a negative regulator of LDL binding to the LDL receptor by limiting access to the apoB-100 LDL receptor- and PG binding sites (36, 38). Thus, in LDL(−), the carboxyl terminus may sterically hinder the interaction of the apoB-100 LDL receptor binding site with the LDL receptor.

Concerning LDL binding to PG, the two main responsible sites described are located in the receptor-binding area: site A (residues 3148–3158) and site B (residues 3359–3369) (39). Although we did not find different reactivity between LDL(+) and LDL(−) for epitopes in this region of the apoB-100 primary structure, we did observe that, LDL(−) binds with higher affinity to arterial PGs, mainly due to the agLDL(−) fraction as was reported previously (17). LDL(+) and nagLDL(−) show a narrow and well defined peak in PG affinity chromatography, suggesting a single binding site. In contrast, the broad shape of the agLDL(−) peak could indicate the existence of several binding sites to PGs. This suggests that such increased binding could be mediated by alternative sites exposed in agLDL(−). Another PG binding site in the amino-terminal region of apoB, the site B-Ib (residues 84–94), has been described that is sufficient for the interaction of apoB-48 or carboxyl-truncated forms of apoB-100 with PGs (40). It has been proposed that this site is not functional in native LDL because a region of the carboxyl-terminal area (residues 3687–4081) covers this site, rendering it inaccessible to PGs (41). The altered conformation of the apoB-100 carboxyl-terminal region in LDL(−), which is manifested by the increased immunoreactivity of the Bsol 2, Bsol 7, 588, and 4H11 epitopes, may permit the unmasking of the B-Ib PG binding site. In addition, Bsol 10 and Bsol 14 epitopes in the amino-terminal region of apoB-100 in LDL(−) are highly exposed and this would concur with the site B-Ib being accessible and resulting in increased PG binding affinity for agLDL(−). This hypothesis is supported by the finding that, in presence of Bsol 10 and Bsol 14, the peak of agLDL(−) eluted at lower ionic strength and its shape changed to a narrow peak, similar to that of LDL(+) and nagLDL(−). Thus, the agLDL(−) peak would be formed by two components, one that would bind to site B and elutes close to the LDL(+) peak (the left side of the peak) and a second one that would bind to site B-Ib and elutes at higher ionic strength (the right side of the peak). Bsol 10 and Bsol 14 would block the binding to site B-Ib, allowing only the interaction to site B. Therefore, our data support the idea that site B-Ib plays a major role in the increased binding of agLDL(−) to PGs.

Taken together, our results suggest that LDL(−) presents a different apoB-100 conformation compared with LDL(+). The altered immunoreactivity of epitopes in the amino-terminal region of apoB-100 in LDL(−) can largely be attributed to particle aggregation or a change in conformation that is coincident with particle aggregation. In contrast, aggregated LDL(−) particles are only partially responsible for the increased immunoreactivity of epitopes in the carboxyl terminus of apoB-100 in LDL(−), suggesting that other physiochemical properties of LDL(−) also influence apoB-100 conformation. Most importantly, we present compelling evidence that the altered apoB-100 conformation leads to unmasking of an amino-terminal apoB-100 PG-binding site in agLDL(−). The increased affinity of agLDL(−) for PGs is an important component of its atherogenic properties.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Michèle Geoffrion for the help in setting up the competitive immunoassays. Wihuri Research Institute is maintained by the Jenny and Antti Wihuri Foundation. The antibodies B2 and B4 were kindly provided by J. C. Fruchart (Institut Pasteur, Lille, France) and MB47, by L. K. Curtiss (Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA).

This work was supported by Spanish Ministry of Health (Instituto de Salud Carlos III/Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (ISCIII/FIS)) Grants PI06/0500 and PI09/0160 and from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (Grant T6110).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table 1S and Fig. 1S.

- apoB-100

- apolipoprotein B-100

- agLDL

- aggregated LDL

- BHT

- butylated hydroxytoluene

- LDL(−)

- electronegative LDL

- LDL(+)

- native electropositive LDL

- mAb

- monoclonal antibody

- nagLDL

- nonaggregated LDL

- oxLDL

- oxidized LDL

- PG

- proteoglycan

- sPLA2

- secretory phospholipase A2

- PLA2

- phospholipase A2

- SMase

- sphingomyelinase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Segrest J. P., Jones M. K., De Loof H., Dashti N. (2001) J. Lipid Res. 42, 1346–1367 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Johs A., Hammel M., Waldner I., May R. P., Laggner P., Prassl R. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 19732–19739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hevonoja T., Pentikäinen M. O., Hyvönen M. T., Kovanen P. T., Ala-Korpela M. (2000) Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1488, 189–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sánchez-Quesada J. L., Otal-Entraigas C., Franco M., Jorba O., González-Sastre F., Blanco-Vaca F., Ordóñez-Llanos J. (1999) Am. J. Cardiol. 84, 655–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sánchez-Quesada J. L., Benítez S., Otal C., Franco M., Blanco-Vaca F., Ordóñez-Llanos J. (2002) J. Lipid Res. 43, 699–705 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sánchez-Quesada J. L., Pérez A., Caixàs A., Rigla M., Payés A., Benítez S., Ordóñez-Llanos J. (2001) J Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 86, 3243–3249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ziouzenkova O., Asatryan L., Akmal M., Tetta C., Wratten M. L., Loseto-Wich G., Jürgens G., Heinecke J., Sevanian A. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 18916–18924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Marcel Y. L., Hogue M., Weech P. K., Davignon J., Milne R. W. (1988) Arteriosclerosis 8, 832–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ziegler O., Méjean L., Igau B., Fruchart J. C., Drouin P., Fiévet C. (1996) Diabetes Metab. 22, 179–184 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Reade R., Equagoo V., Cachera C., Duriez P., Dracon M., Bard J. M., Fievet C., Bertrand M., Tacquet A., Fruchart J. C. (1989) Am. J. Nephrol. 9, 110–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Benítez S., Bancells C., Ordóñez-Llanos J., Sánchez-Quesada J. L. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1771, 613–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Benítez S., Camacho M., Bancells C., Vila L., Sánchez-Quesada J. L., Ordóñez-Llanos J. (2006) Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1761, 1014–1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen C. H., Jiang T., Yang J. H., Jiang W., Lu J., Marathe G. K., Pownall H. J., Ballantyne C. M., McIntyre T. M., Henry P. D., Yang C. Y. (2003) Circulation 107, 2102–2108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Demuth K., Myara I., Chappey B., Vedie B., Pech-Amsellem M. A., Haberland M. E., Moatti N. (1996) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 16, 773–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Avogaro P., Bon G. B., Cazzolato G. (1988) Arteriosclerosis 8, 79–87 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Benítez S., Villegas V., Bancells C., Jorba O., González-Sastre F., Ordóñez-Llanos J., Sánchez-Quesada J. L. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 15863–15872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bancells C., Benítez S., Jauhiainen M., Ordóñez-Llanos J., Kovanen P. T., Villegas S., Sánchez-Quesada J. L., Oörni K. (2009) J. Lipid Res. 50, 446–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Parasassi T., Bittolo-Bon G., Brunelli R., Cazzolato G., Krasnowska E. K., Mei G., Sevanian A., Ursini F. (2001) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 31, 82–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Asatryan L., Hamilton R. T., Isas J. M., Hwang J., Kayed R., Sevanian A. (2005) J. Lipid Res. 46, 115–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sánchez-Quesada J. L., Camacho M., Antón R., Benítez S., Vila L., Ordóñez-Llanos J. (2003) Atherosclerosis 166, 261–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bancells C., Villegas S., Blanco F. J., Benítez S., Gállego I., Beloki L., Pérez-Cuellar M., Ordóñez-Llanos J., Sánchez-Quesada J. L. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 32425–32435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Benítez S., Camacho M., Arcelus R., Vila L., Bancells C., Ordóñez-Llanos J., Sánchez-Quesada J. L. (2004) Atherosclerosis 177, 299–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Oörni K., Hakala J. K., Annila A., Ala-Korpela M., Kovanen P. T. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 29127–29134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bancells C., Benítez S., Villegas S., Jorba O., Ordóñez-Llanos J., Sánchez-Quesada J. L. (2008) Biochemistry 47, 8186–8194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pease R. J., Milne R. W., Jessup W. K., Law A., Provost P., Fruchart J. C., Dean R. T., Marcel Y. L., Scott J. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 553–568 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang X., Pease R., Bertinato J., Milne R. W. (2000) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 20, 1301–1308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang X., Bucala R., Milne R. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 7643–7647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Milne R. W., Theolis R., Jr., Verdery R. B., Marcel Y. L. (1983) Arteriosclerosis 3, 23–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sánchez-Quesada J. L., Benítez S., Ordóñez-Llanos J. (2004) Curr. Opin Lipidol. 15, 329–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zawadzki Z., Milne R. W., Marcel Y. L. (1989) J. Lipid Res. 30, 885–891 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zawadzki Z., Milne R. W., Marcel Y. L. (1991) J. Lipid Res. 32, 243–250 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hoff H. F., Whitaker T. E., O'Neil J. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 602–609 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Blanco F. J., Villegas S., Benítez S., Bancells C., Diercks T., Ordóñez-Llanos J., Sánchez-Quesada J. L. (2010) J. Lipid Res. 51, 1560–1565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Witztum J. L., Horkko S. (1997) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 811, 88–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sevanian A., Bittolo-Bon G., Cazzolato G., Hodis H., Hwang J., Zamburlini A., Maiorino M., Ursini F. (1997) J. Lipid Res. 38, 419–428 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Boren J., Lee I., Zhu W., Arnold K., Taylor S., Innerarity T. L. (1998) J. Clin. Invest. 101, 1084–1093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Milne R., Théolis R., Jr., Maurice R., Pease R. J., Weech P. K., Rassart E., Fruchart J. C., Scott J., Marcel Y. L. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264, 19754–19760 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chatterton J. E., Phillips M. L., Curtiss L. K., Milne R., Fruchart J. C., Schumaker V. N. (1995) J. Lipid Res. 36, 2027–2037 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gustafsson M., Borén J. (2004) Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 15, 505–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Goldberg I. J., Wagner W. D., Pang L., Paka L., Curtiss L. K., DeLozier J. A., Shelness G. S., Young C. S., Pillarisetti S. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 35355–35361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Flood C., Gustafsson M., Richardson P. E., Harvey S. C., Segrest J. P., Borén J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 32228–32233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.