Abstract

In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, triacylglycerol mobilization for phospholipid synthesis occurs during growth resumption from stationary phase, and this metabolism is essential in the absence of de novo fatty acid synthesis. In this work, we provide evidence that DGK1-encoded diacylglycerol kinase activity is required to convert triacylglycerol-derived diacylglycerol to phosphatidate for phospholipid synthesis. Cells lacking diacylglycerol kinase activity (e.g. dgk1Δ mutation) failed to resume growth in the presence of the fatty acid synthesis inhibitor cerulenin. Lipid analysis data showed that dgk1Δ mutant cells did not mobilize triacylglycerol for membrane phospholipid synthesis and accumulated diacylglycerol. The dgk1Δ phenotypes were partially complemented by preventing the formation of diacylglycerol by the PAH1-encoded phosphatidate phosphatase and by channeling diacylglycerol to phosphatidylcholine via the Kennedy pathway. These observations, coupled to an inhibitory effect of dioctanoyl-diacylglycerol on the growth of wild type cells, indicated that diacylglycerol kinase also functions to alleviate diacylglycerol toxicity.

Keywords: Diacylglycerol, Phosphatidate, Phospholipid, Triacylglycerol, Yeast, Diacylglycerol Kinase

Introduction

In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the lipids PA2 and DAG are essential intermediates in the synthesis of membrane phospholipids and the storage lipid TAG (1–3). In the de novo pathway, PA is the precursor to the major phospholipids (e.g. PC, PE, PI, and PS) that are synthesized by way of CDP-DAG (1). Alternatively, PA is converted to DAG (catalyzed by PAH13-encoded PA phosphatase), which is then utilized by acyltransferase enzymes (principally those encoded by DGA1 and LRO1) to synthesize TAG (1–6). The DAG generated by the PA phosphatase reaction may also be utilized for the synthesis of the phospholipids PC and PE by way of the Kennedy pathway when cells are supplemented with choline and ethanolamine, respectively (1, 4). In addition to their roles in lipid synthesis, PA and DAG are signaling molecules that affect various aspects of cell physiology that include activation of cell growth, membrane proliferation, transcription, and vesicular trafficking (7–16).

PAH1-encoded PA phosphatase (4) and DGK14-encoded DAG kinase (17, 18) have emerged as key regulators of the cellular levels of PA and DAG in S. cerevisiae. PA phosphatase is a cytoplasmic enzyme that associates with the nuclear/ER membrane to catalyze the formation of DAG from PA (4, 19). DAG kinase is a unique CTP-dependent nuclear/ER membrane-associated enzyme that catalyzes the formation of PA from DAG (17, 18). Cells bearing pah1 mutations have an increase in PA content and exhibit an aberrant expansion of the nuclear/ER membrane (4, 20, 21). Moreover, the elevation of PA in pah1 mutant cells is associated with the derepression of phospholipid synthesis gene expression (20, 21), which occurs when Opi1p repressor function is inhibited because of an association of the repressor with PA at the nuclear/ER membrane (22, 23). By contrast, the overexpression of PA phosphatase activity causes the loss of PA, the repression of phospholipid synthesis gene expression, and inositol auxotrophy (24). DAG kinase counterbalances the role that PA phosphatase plays in lipid metabolism and cell physiology (17, 18). The overexpression of DAG kinase causes an increase in PA content, the derepression of phospholipid synthesis genes, and the abnormal nuclear/ER membrane expansion (17) like the phenotypes exhibited by pah1 mutants (20, 21). Nevertheless, the overexpression of DAG kinase activity complements the inositol auxotrophy caused by the overexpression of PA phosphatase activity (17). The loss of DAG kinase activity complements the phenotypes caused by the loss of PA phosphatase activity (e.g. dgk1Δ pah1Δ mutations) (17, 18). In contrast, cells bearing the dgk1Δ mutation alone do not exhibit any remarkable phenotypes (17).

In S. cerevisiae, the synthesis of TAG, which is derived from PA via DAG, occurs during vegetative growth, and it accumulates in lipid droplets at the stationary (quiescent) phase (2, 3, 25–28). TAG synthesis is important to cell physiology because it controls the metabolic flux of fatty acids into membrane phospholipids, prevents the toxicity caused by free fatty acids, and provides metabolites for sporulation and cell cycle progression (2, 3, 25–27, 29, 30). The hydrolysis of TAG (principally mediated by the TGL3- and TGL4-encoded TAG lipases) is equally important to cell physiology because it generates free fatty acids for initiation of membrane phospholipid synthesis, and this allows cells to exit the stationary phase and resume vegetative growth (2, 3, 31–34). In fact, mutants (tgl3Δ and tgl4Δ) defective in TAG lipase activity are severely retarded in their ability to resume growth from the stationary phase because de novo fatty acid synthesis is not sufficient for membrane biogenesis (3, 31).

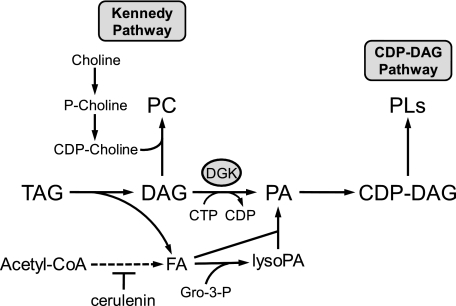

In this work, we addressed the hypothesis that DAG kinase activity is required for phospholipid synthesis in growth resumption from the stationary phase. This notion was based on the fact that the most direct route for de novo membrane phospholipid synthesis following the hydrolysis of TAG is through the DAG kinase reaction (Fig. 1). Using dgk1Δ mutant cells, we showed that the resumption of growth from the stationary phase is controlled by DAG kinase activity, in particular when de novo fatty acid synthesis was inhibited. Moreover, in wild type cells, the resumption of growth was accompanied by the induction of DAG kinase activity. We also showed that choline supplementation could bypass the requirement of DAG kinase for growth resumption, thereby linking the Kennedy pathway for phospholipid synthesis to the mobilization of TAG.

FIGURE 1.

Mobilization of TAG for the synthesize phospholipids to resume growth from stationary phase. The pathways shown for the mobilization of TAG for the synthesis of phospholipids (PLs) include the relevant steps discussed in this work. Although not shown in the figure, the fatty acid derived from TAG is converted to fatty acyl-CoA before it is incorporated into PA. The reaction catalyzed by DAG kinase (DGK) is indicated in the figure. Gro-3-P, glycerol-3-P.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Growth medium components were purchased from Difco. Restriction endonucleases, modifying enzymes, and Vent DNA polymerase were from New England Biolabs. The DNA purification kit was from Qiagen. Cerulenin, nucleotides, nucleoside 5′-diphosphate kinase, choline, phosphocholine, CDP-choline, ethanolamine, Triton X-100, fatty acid methyl ester standards, and protease inhibitors (phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, benzamidine, aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin) were from Sigma. Oligonucleotides were prepared by Genosys Biotechnologies, Inc. The Yeast Maker yeast transformation kit was purchased from Clontech. Radiochemicals were purchased from PerkinElmer Life Sciences. Lipids were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids. Silica gel thin layer chromatography plates were from EM Science.

Strains and Growth Conditions

The bacterial and yeast strains used in this work are listed in Table 1. Yeast cells were grown in YEPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose) or in synthetic complete (SC) medium containing 2% glucose at 30 °C as described previously (35, 36). For selection of yeast cells bearing plasmids, appropriate amino acids were omitted from SC medium. Plasmid maintenance and amplifications were performed in Escherichia coli strain DH5α. E. coli cells were grown in LB medium (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 1% NaCl, pH 7.4) at 37 °C, and ampicillin (100 μg/ml) was added to select for the bacterial cells carrying plasmids. For growth on solid media, plates were prepared with supplementation of either 2% (yeast) or 1.5% (E. coli) agar.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | F− φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 deoR recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rk−mk+) phoA supE44 l−thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 | Ref. 36 |

| S. cerevisiae | ||

| BY4742 | MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 | Ref. 69 |

| RS453 | MATaade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-52 | Ref. 70 |

| SS1144 | dgk1Δ::HIS3 derivative of RS453 | Ref. 17 |

| SS1147 | dgk1Δ::HIS3 pah1Δ::TRP1 derivative of RS453 | Ref. 17 |

| SF1111 | dgk1Δ::HIS3 spo14Δ::LEU2 derivative of RS453 | This study |

| PMY201 | nte1Δ::KanMX4 derivative of BY4742 | Euroscarf |

| SF1112 | dgk1Δ::HIS3 nte1Δ::KanMX4 derivative of RS453 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pRS416 | Single copy E. coli/yeast shuttle vector with URA3 | Ref. 71 |

| pSF211 | DGK1 inserted into pRS416 | This study |

| pSF212 | DGK1(D177A) derivative of pSF211 | This study |

| pΜΕ913 | Plasmid containing the spo14Δ::LEU2 deletion cassette | Ref. 44 |

For growth resumption from stationary phase, cultures (three isolates per strain) were grown for 48 h in SC medium to reach stationary phase, harvested by centrifugation, and diluted with fresh SC medium to an absorbance of ∼0.1 (for growth curves) or ∼1.0 (for lipid and enzyme analyses). Dilution of cells to the higher cell density facilitated the extraction and analysis of lipids and enzymes and allowed cells to enter logarithmic growth in a shorter amount of time. By the 5 h time point, the cultures entered the logarithmic phase of growth. The fatty acid synthesis inhibitor cerulenin (37, 38) and the cell-permeable analog dioctanoyl-DAG (39) were added to cultures from stock solutions (1 and 10 mg/ml, respectively) made in ethanol. Control experiments showed that the small amount of ethanol that was introduced into the culture medium did not affect growth. For growth curves, cultures (200 μl) were incubated in 96-well plates, and the absorbance (600-nm filter) of the cultures was monitored with a Thermomax plate reader. Generation times were calculated from the growth curves according to the modified Gompertz equation (40). For viability assays, cells grown in SC medium containing 10 μg/ml cerulenin were collected by centrifugation and resupended in YEPD medium to the same cell density, and serial dilutions were inoculated onto YEPD agar plates and incubated at 30 °C for 4 days. For dry cell weight determination, cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed twice with distilled water, and incubated at 80 °C until a constant weight was obtained.

DNA Manipulations, Amplification of DNA by PCR, and DNA Sequencing

Standard methods were used to isolate plasmid and genomic DNA and for the manipulation of DNA using restriction enzymes, DNA ligase, and modifying enzymes (36). Yeast (41) and E. coli (36) transformations were performed by standard protocols. PCRs were optimized as described by Innis and Gelfand (42). DNA sequencing was performed by GENEWIZ, Inc. using Applied Biosystems BigDye version 3.1. The reactions were then run on Applied Biosystems 3730xl DNA Analyzer.

Plasmid Construction

The plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1. A 2.4-kb DNA fragment that contains the entire DGK1 (17) coding sequence (0.873 kb), the 5′-untranslated region (1 kb), and the 3′-untranslated region (0.5 kb) was amplified from the genomic DNA of S. cerevisiae strain BY4742. This fragment was digested with XbaI/HindIII and inserted into plasmid pRS416 at the same restriction enzyme sites to construct plasmid pSF211. Plasmid pSF212 is a derivative of pSF211 whereby the DGK1(D177A) mutation (17) was constructed by PCR mutagenesis. All plasmid constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

Construction of the dgk1Δ spo14Δ and dgk1Δ nte1Δ Mutants

Deletion of the SPO14 and NTE1 genes in the dgk1Δ mutant was performed by the method of one-step gene replacement (43). The spo14Δ::LEU2 deletion cassette was released from plasmid pME913 (44) by digestion with NotI/XhoI, whereas the nte1Δ::KanMX4 deletion cassette in BY4742 nte1Δ was amplified by PCR. Each deletion cassette was used to transform the dgk1Δ mutant to construct the dgk1Δ spo14Δ and dgk1Δ nte1Δ mutants, respectively. The dgk1Δ spo14Δ mutants were selected on SC-leucine plates, and the dgk1Δ nte1Δ mutants were selected on YEPD plates containing 200 μg/ml Geneticin. Disruptions of SPO14 and NTE1 were confirmed by PCR analysis of genomic DNA using primers that flanked the respective insertions.

Lipid Extractions

Lipids were extracted from yeast cells by the method of Bligh and Dyer (45). In brief, cells were harvested and washed twice with distilled water. 5 ml of CHCl3, MeOH, 0.1 n HCl (1:2:0.8, v/v/v) were added, and the cell suspension was homogenized by vortexing (2 × 1 min) with glass beads. Then 1.5 ml of CHCl3, 1.5 ml of 0.1 n HCl, and 150 μl of 0.1 n NaCl were added, and the samples were centrifuged for 3 min at 1,500 × g. The aqueous phase was discarded, and 2.5 ml of MeOH, 2.5 ml of 0.1 n HCl, and 150 μl of 0.1 n NaCl were added to the chloroform phase. The samples were centrifuged for 3 min at 1,500 × g, the aqueous phase was discarded, and the chloroform phase was dried over anhydrous MgSO4. The samples were transferred to fresh tubes and dried in vacuo. Finally, the dried lipid extracts were resuspended in chloroform and used for lipid analysis.

Determination of TAG

The mass of TAG was determined by HPLC analysis of lipid extracts using a Waters 2695 Alliance system. A 4.6 × 100-mm Waters Spherisorb column coupled to a SEDEX 55 evaporative light scattering detector was used. The analysis was run at 45 °C using a tertiary solvent gradient (46). A triolein standard curve was constructed and used for the quantification of TAG.

Determination of DAG

For determination of DAG in the growth medium, a portion of the medium (5 ml) was extracted three times with an equal volume of hexane, the extracts were combined, and the solvent was removed by rotary evaporation. Nonanoic acid was added as an internal standard for quantification, and the extracts were transmethylated by heating at 70 °C with a mixture of 0.5 n HCl in methanol (3 ml) and toluene (0.5 ml) for 2 h. The fatty acids methyl esters were extracted three times with petroleum ether and analyzed by gas chromatography using a Thermo Scientific TR-FAME column (0.25 μm × 60 m) and a flame ionization detector. Helium was the carrier gas (26 p.s.i.). The column temperature was first held constant at 140 °C for 5 min, followed by an increase in temperature to 240 °C at a rate of 4 °C/min. The injector temperature was 240 °C, and the detector temperature was 250 °C. Fatty acid methyl esters were identified by reference to authentic standards analyzed under the same conditions.

For determination of DAG in cells treated with dioctanoyl-DAG, cultures were harvested, washed twice with distilled water, and then washed twice with hexane to remove any dioctanoyl-DAG that might be associated with the cell surface. Lipids were extracted from the cells and separated by TLC using the solvent system hexane/diethyl ether/glacial acetic acid (80:20:2, v/v/v). The developed plates were sprayed with a solution of primulin (0.05% in acetone/water, 8:2, v/v) and viewed under UV light, and the spot corresponding to DAG was scrapped off and transferred to a 10-ml screw cap test tube (47). Margaric acid was added as an internal standard, and the lipid was directly transmethylated as described above. Fatty acid methyl esters were extracted three times with diethyl ether and analyzed by gas chromatography.

Labeling and Analysis of Neutral Lipids and Phospholipids

For neutral lipid analysis, cells were grown to stationary phase in the presence of [2-14C]acetate (1 μCi/ml), harvested and washed with water, and then resuspended to an A600 nm of 1.0 in fresh medium without [2-14C]acetate. Neutral lipids were analyzed by TLC using the solvent system hexane/diethyl ether/glacial acetic acid (80:20:2, v/v/v). For phospholipid analysis, cells were grown to stationary phase in the presence of 32Pi (10 μCi/ml) and then diluted to an A600 nm of 1.0 in fresh medium containing 10 μCi/ml 32Pi. Phospholipids were analyzed by two-dimensional TLC using chloroform/methanol/ammonium hydroxide/water (45:25:2:3, v/v/v/v) as the solvent system for dimension one and chloroform/methanol/glacial acetic acid/water (32:4:5:1, v/v/v/v) as the solvent system for dimension two. The identity of the labeled lipids on TLC plates was confirmed by comparison with standards after exposure to iodine vapor. Radiolabeled lipids were visualized by phosphorimaging analysis, and the relative quantities of labeled lipids were analyzed using ImageQuant software.

Labeling and Analysis of CDP-Choline Pathway Intermediates and PC

Cells were grown to stationary phase and then diluted to an A600 nm of 1.0 in fresh medium containing 1 mm [methyl-14C]choline (0.2 μCi/ml). The CDP-choline pathway intermediates and PC were extracted from whole cells by a chloroform/methanol/water extraction, followed by separation of the aqueous and chloroform phases (45). The aqueous and chloroform phases that contained the CDP-choline pathway intermediates and PC, respectively, were dried in vacuo and then dissolved in 100 μl of methanol/water (1:1, v/v) and 100 μl of chloroform, respectively. The CDP-choline pathway intermediates and PC were subjected to TLC on silica gel plates using the solvent systems methanol, 0.6% sodium chloride, ammonium hydroxide (10:10:1, v/v/v) and chloroform, pyridine, 88% formic acid, methanol, water (60:35:10:5:2, v/v/v/v/v), respectively. The positions of the labeled compounds on the chromatograms were determined by phosphorimaging and compared with standards. The quantities of labeled lipids were analyzed using ImageQuant software.

Preparation of Cell Extracts and Protein Determination

All steps were performed at 4 °C. At the indicated time intervals, cultures were harvested by centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 5 min. The resulting cell pellets were washed once with water and resuspended in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) buffer containing 0.3 m sucrose, 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm 2-mercaptoethanol, and a mixture of protease inhibitors (0.5 mm phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, 1 mm benzamidine, 5 μg/ml aprotinin, 5 μg/ml leupeptin, and 5 μg/ml pepstatin). The cell suspensions were mixed with glass beads (0.5-mm diameter) and disrupted using a Mini BeadBeater-16 (Biospec Products) as described previously (48). Unbroken cells and glass beads were removed by centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was used as the cell extract. Protein concentration was measured by the method of Bradford (49) using bovine serum albumin as the standard.

DAG Kinase Assay

DAG kinase activity was measured by following the incorporation of the γ-phosphate of water-soluble [γ-32P]CTP (30,000 cpm/nmol) into chloroform-soluble PA as described by Han et al. (18). The reaction mixture contained 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mm Triton X-100, 0.1 mm dioleoyl-DAG, 1 mm CTP, 1 mm CaCl2, 10 mm 2-mercaptoethanol, and enzyme protein in a total volume of 0.1 ml. The [γ-32P]CTP was synthesized enzymatically from CDP and [γ-32P]ATP with nucleoside 5′-diphosphate kinase (50) as described by Han et al. (18). All enzyme assays were conducted in triplicate at 30 °C, and they were linear with time and protein concentration. The average S.D. value of the DAG kinase assay was ±10%. One unit of activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzed the formation of 1 pmol of product/min, and the specific activity was defined as units/mg protein.

Analysis of Data

Statistical analysis of the data was performed with SigmaPlot software. p values of <0.05 were taken as a significant difference.

RESULTS

dgk1Δ Mutant Cells Fail to Resume Growth from Stationary Phase in the Presence of Cerulenin and Fail to Metabolize TAG

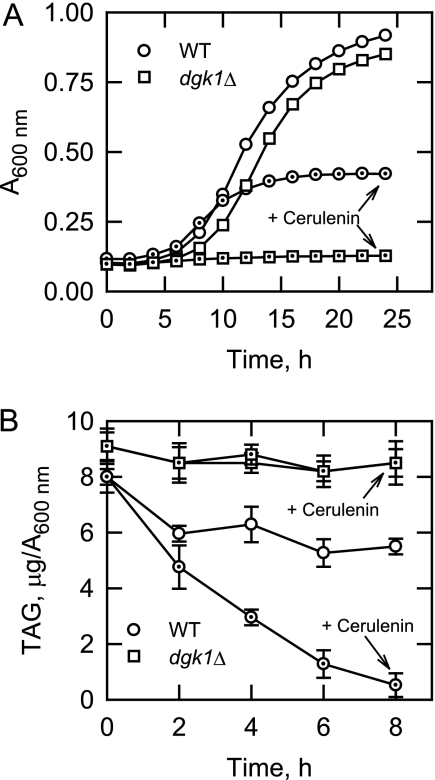

Cells that resume logarithmic growth from the stationary phase are initially dependent on the hydrolysis of TAG to produce precursor fatty acids for membrane phospholipid synthesis (2, 3, 25, 31, 51). Due to the fact that the DGK1-encoded DAG kinase utilizes DAG to produce PA, the phospholipid precursor used for de novo phospholipid synthesis via the CDP-DAG pathway (Fig. 1) (23), we questioned what effect the dgk1Δ mutation would have on the resumption of growth from the stationary phase. Wild type and dgk1Δ mutant cells were first grown to the stationary phase and then diluted with fresh growth medium for the resumption of logarithmic growth. The lag period before the resumption of logarithmic growth was extended by 1.5 h for dgk1Δ mutant cells when compared with that of the wild type control cells (Fig. 2A). However, once the cells resumed growth, the generation times (1.87 ± 0.03 and 1.90 ± 0.03 h, respectively) for both wild type and dgk1Δ cultures were similar (Fig. 2A). To accentuate the requirement of TAG hydrolysis in growth resumption (31–33), the effect of the fatty acid synthesis inhibitor cerulenin (37, 38) was examined. In the absence of de novo fatty acid synthesis, the growth of wild type cells was diminished (as reflected in an increase in generation time from 1.87 ± 0.03 to 3.12 ± 0.05 h and decrease in maximum cell number), whereas dgk1Δ mutant cells failed to resume logarithmic growth (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

dgk1Δ mutant cells fail to resume growth from stationary phase in the presence of cerulenin and fail to metabolize TAG. Wild type and dgk1Δ mutant cells were grown to stationary phase in SC medium and then diluted in fresh medium without and with 10 μg/ml cerulenin where indicated. A, growth after the transfer to fresh medium was monitored with a plate reader. Each data point represents the average of three independent cultures. The generation times for wild type cells grown in the absence and presence of cerulenin were 1.87 ± 0.03 and 3.12 ± 0.05 h, respectively, and the generation time for dgk1Δ mutant cells grown in the absence of cerulenin was 1.90 ± 0.03 h. B, cells were harvested at the indicated time points, lipids were extracted, and the amount of TAG was determined by HPLC. Each data point represents the average of three experiments ± S.D. (error bars) The symbols for the dgk1Δ cells grown in the absence of cerulenin are hidden behind those for dgk1Δ cells grown in the presence of cerulenin. The dot inside the symbols is where cerulenin was present in the growth medium.

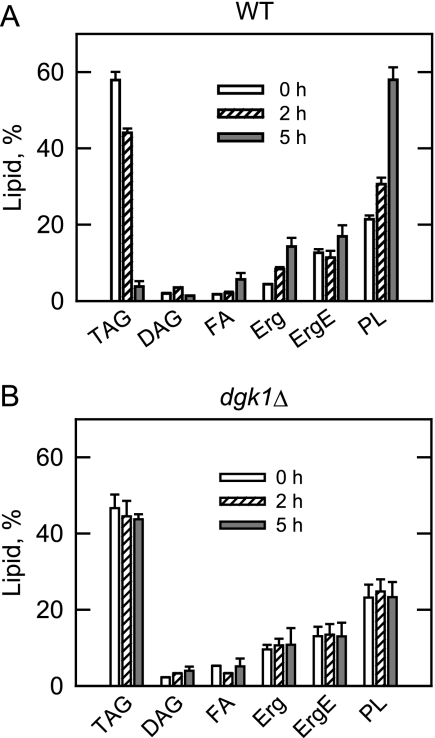

The amount of TAG in wild type and dgk1Δ mutant cells was examined as the cells resumed growth from the stationary phase (Fig. 2B). In wild type cells, the amount of TAG declined by 26–30% between 2 and 8 h following the transfer of cells to fresh growth medium, but in the presence cerulenin, greater than 90% of TAG was metabolized by 8 h. These results are consistent with previous studies (31). In contrast to wild type cells, the amount of TAG in dgk1Δ mutant cells grown in the absence or presence of cerulenin declined by only 5% and remained constant during this time period. Pulse-chase experiments were performed with [2-14C]acetate to examine the effects of cerulenin on the metabolism of lipids during growth resumption from stationary phase. For wild type cells, the time-dependent decline in TAG content (93% by 5 h) correlated with time-dependent increases in the amounts of fatty acids (70% by 5 h), ergosterol (70% by 5 h), and phospholipids (64% by 5 h) (Fig. 3A). With respect to the changes in ergosterol levels, analysis of the pah1Δ mutant cells has indicated coordinate changes with PA metabolism (4). In addition, the amount of DAG first increased (45% by 2 h) and then decreased (60% by 5 h) following transfer to fresh growth medium (Fig. 3A). However, in dgk1Δ mutant cells, there was only a small decrease (6% by 5 h) in TAG, an increase in DAG (45% by 5 h), and little change in other lipids following transfer to fresh growth medium (Fig. 3B). The lack of TAG mobilization for phospholipid synthesis correlated with the lack of cellular growth in the presence of cerulenin (Fig. 2A). Overall, these data supported the conclusion that the DGK1 gene was essential for growth resumption in yeast compromised for de novo fatty acid synthesis.

FIGURE 3.

dgk1Δ mutant cells fail to utilize TAG for phospholipid synthesis in the presence of cerulenin. Wild type (A) and dgk1Δ (B) cells were grown to stationary phase in SC medium in the presence of [2-14C]acetate (1 μCi/ml) to uniformly label cellular lipids. The cells were then washed to remove the label and resuspended in fresh medium that contained 10 μg/ml cerulenin. At the indicated time points, cells were harvested, and lipids were extracted and separated by one-dimensional TLC. The 14C-labeled lipids were visualized by phosphorimaging and were quantified by ImageQuant analysis. The percentages shown for the individual lipids were normalized to the total 14C-labeled chloroform-soluble fraction. The values reported are the average of three separate experiments ± S.D. (error bars). Erg, ergosterol; ErgE, ergosterol ester; FA, fatty acids; PL, phospholipids.

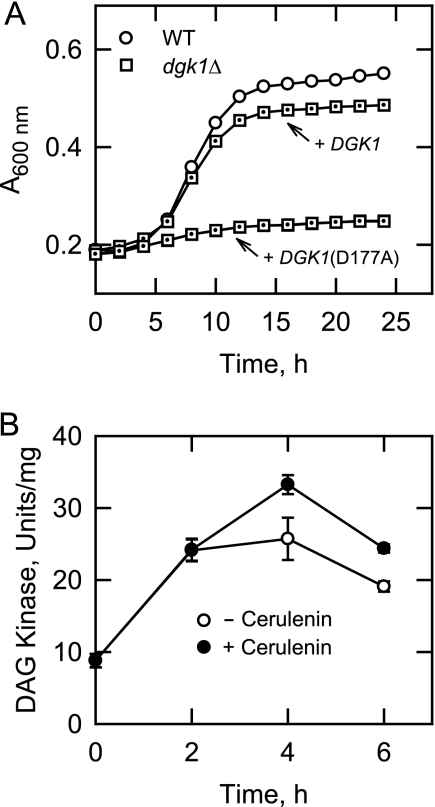

DAG Kinase Activity Is Required for the Resumption of Growth from Stationary Phase in the Presence of Cerulenin, and Enzyme Activity Is Induced during Growth Resumption

We questioned if the loss-of-growth phenotype of dgk1Δ mutant cells was specifically due to the loss of DAG kinase activity or due to the loss of another function associated with the DGK1 gene product. To address this question, we examined the effect of the DGK1(D177A) allele that encodes a catalytically inactive DAG kinase (17, 18) on growth resumption. dgk1Δ cells transformed with a low copy plasmid bearing the wild type DGK1 and DGK1(177A) alleles were subjected to the growth regime described above whereby the resumption of growth from stationary phase was examined in the presence of cerulenin. Whereas the wild type DGK1 allele complemented the loss-of-growth phenotype of the dgk1Δ mutant, the DGK1(D177A) mutant allele did not complement the mutant phenotype (Fig. 4A). This result indicated that DAG kinase activity was required for the growth resumption in the medium containing cerulenin.

FIGURE 4.

DAG kinase activity is required for the resumption of growth from stationary phase in the presence of cerulenin, and enzyme activity is induced during growth resumption. A, Wild type, dgk1Δ, and dgk1Δ expressing the wild type DGK1 and DGK1(D177A) mutant alleles from single copy plasmids were grown to stationary phase in SC medium and then diluted in fresh medium containing 10 μg/ml cerulenin. Growth after the transfer to fresh medium was monitored with a plate reader. Each data point represents the average of three independent cultures. The dot inside the symbols is where the DGK1 alleles were expressed in the dgk1Δ mutant. The symbols for the dgk1Δ cells are hidden behind those for dgk1Δ bearing the DGK1(D177A) allele. The generation times for wild type and dgk1Δ cells expressing the DGK1 allele were 6.5 ± 1.1 and 6.9 ± 1.6 h, respectively. B, wild type cells were grown to stationary phase in SC medium and then resuspended in fresh medium without and with 10 μg/ml cerulenin where indicated. At the indicated time points, cells were harvested, cell extracts were prepared, and DAG kinase activity was measured. Each data point represents the average of triplicate enzyme determinations from a minimum of two independent experiments ± S.D. (error bars).

Due to the fact that DAG kinase activity was required for growth resumption from stationary phase in the presence of cerulenin, we questioned whether the expression of activity was regulated during this process in wild type cells. To address this question, stationary phase wild type cells were diluted in fresh growth medium without and with cerulenin; cell extracts were prepared and used for the analysis of DAG kinase activity by following the incorporation of the γ-phosphate of CTP into PA in the presence of DAG. Following the transfer of cells to fresh growth medium, there was a time-dependent increase in the level of DAG kinase activity in both the presence (3.7-fold) and absence (3.0-fold) of cerulenin (Fig. 4B).

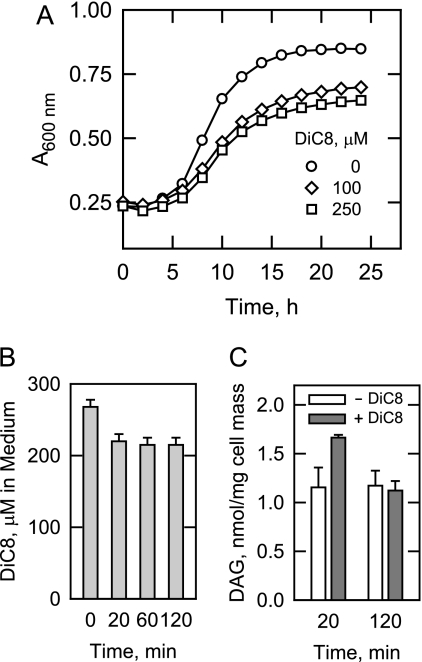

Dioctanoyl-DAG Inhibits Growth of Wild Type Cells

Due to the fact that dgk1Δ mutant cells cannot convert DAG to PA and that the level of DAG was elevated (45%) in cells supplemented with cerulenin, we questioned whether DAG might be toxic to cell growth. Using the approach used to show DAG toxicity in the yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe (39), we supplemented stationary phase wild type cells with cell-permeable dioctanoyl-DAG upon transfer to fresh growth medium. At a concentration of 100 μm, dioctanoyl-DAG inhibited the resumption of logarithmic growth with an increase in generation time and a decrease in maximum cell number (Fig. 5A). Increasing the concentration to 250 μm and above (not shown) did not enhance the inhibitory effect of dioctanoyl-DAG (Fig. 5A). This was attributed to the fact that dioctanoyl-DAG was not readily taken up by the cells because 80% of the compound remained in the growth medium 2 h after its addition (Fig. 5B). Analysis of the cellular DAG revealed that the dioctanoyl-DAG, which could not be detected inside cells, was remodeled to DAG containing the normal complement of yeast fatty acids (e.g. 16:0, 16:1, 18:0, and 18:1) and that the cellular DAG content increased by only 30% following the supplementation with dioctanoyl-DAG (Fig. 5C). By 2 h, the level of DAG in cells with and without dioctanoyl-DAG supplementation was the same (Fig. 5C).

FIGURE 5.

Dioctanoyl-DAG inhibits growth of wild type cells. A, Wild type cells were grown to stationary phase in SC medium and then diluted in fresh medium containing the indicated concentrations of dioctanoyl-DAG (DiC8). Growth after the transfer to fresh medium was monitored with a plate reader. Each data point represents the average of three independent cultures. The generation times for wild type cells grown in the absence and presence of 100 or 250 μm dioctanoyl-DAG were 3.12 ± 0.05 and 5.98 ± 0.05 h, respectively. B, at the indicated time points, the amount of dioctanoyl-DAG remaining in the growth medium of cells incubated with 250 μm dioctanoyl-DAG was determined. C, at the indicated time points, the amount of DAG in cells incubated with 10 μg/ml cerulenin and 250 μm dioctanoyl-DAG was determined. The values shown in B and C are the average of three separate experiments ± S.D. (error bars).

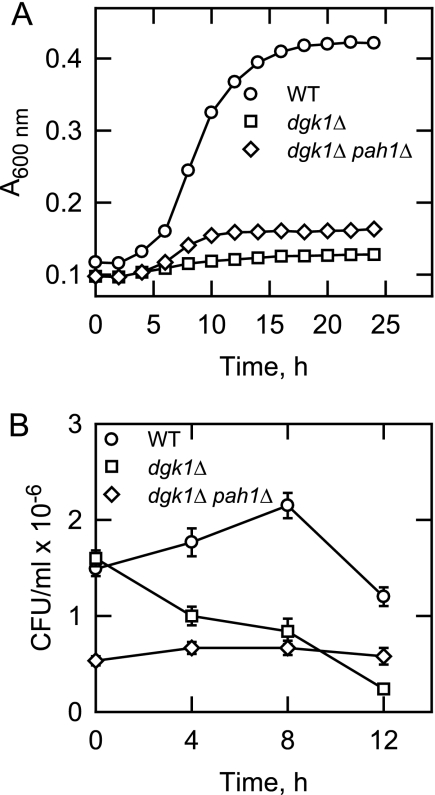

Deletion of PAH1 Partially Restores Growth of dgk1Δ Mutant Cells in the Presence of Cerulenin and Restores the Mobilization of TAG

The PAH1 gene codes for the PA phosphatase enzyme that is responsible for producing the DAG used for the synthesis of TAG and for the synthesis of PC and PE via the Kennedy pathway (4, 52). The enzyme also plays a major role in controlling the cellular concentrations of its substrate PA and product DAG (4). Because the substrate for the PA phosphatase reaction is the product of the DAG kinase reaction and vice versa, we questioned if the deletion of PAH1 in the dgk1Δ mutant would affect the resumption of growth from the stationary phase in the presence of cerulenin. The pah1Δ mutation had a small but significant effect on the ability of dgk1Δ cells to resume logarithmic growth (Fig. 6A). The generation time for the dgk1Δ pah1Δ mutant was 11.9 ± 1.8 h when compared with a generation time of 46.8 ± 12.2 for the dgk1Δ single mutant. Under this condition, the PA required for phospholipid synthesis was presumably made by way of the de novo pathway. In addition, the viability of dgk1Δ mutant cells, which was reduced upon dilution to fresh growth medium containing cerulenin, was stabilized by the pah1Δ mutation (Fig. 6B). The initial viability of the stationary phase dgk1Δ pah1Δ double mutant was low when compared with wild type and dgk1Δ mutant cells (Fig. 6B). These cells had very reduced TAG (due to the pah1Δ mutation) and little reserve of lipid precursors for phospholipid synthesis upon the mobilization of TAG (see below).

FIGURE 6.

Deletion of PAH1 partially restores the growth and viability of dgk1Δ mutant cells grown in the presence of cerulenin. A, Wild type, dgk1Δ, and dgk1Δ pah1Δ mutant cells were grown to stationary phase in SC medium and then diluted in fresh medium containing 10 μg/ml cerulenin. Growth after the transfer to fresh medium was monitored at A600 nm. Each data point represents the average of three independent experiments. The generation times for wild type and dgk1Δ pah1Δ mutant cells were 3.60 ± 0.06 and 11.9 ± 1.8 h, respectively. B, at the indicated time intervals, cells incubated in SC medium containing 10 μg/ml cerulenin (as described for A) were collected by centrifugation and resupended in YEPD medium to the same cell density, and serial dilutions were inoculated onto YEPD agar plates and incubated at 30 °C for 4 days to determine viable cell numbers. CFU, colony-forming unit. Each data point represents the average of three experiments ± S.D. (error bars).

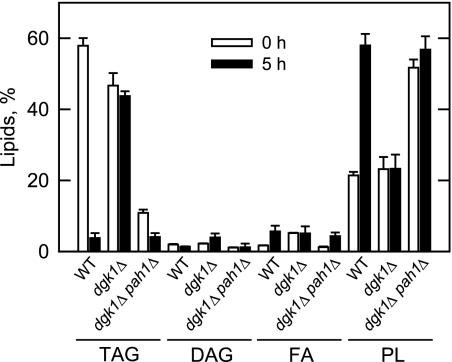

The effect of the dgk1Δ pah1Δ double mutation on the mobilization of TAG for phospholipid synthesis was examined. As described previously (4, 17), the dgk1Δ pah1Δ double mutation caused a reduction in TAG (77–81%) and an increase in phospholipids (55–58%) of stationary phase cells when compared with wild type and dgk1Δ cells (Fig. 7). Moreover, the DAG content in the dgk1Δ pah1Δ mutant was 43–50% lower when compared with wild type and dgk1Δ cells (Fig. 7). Upon resumption of logarithmic growth (e.g. 5 h after transfer to fresh growth medium), the small amount of TAG in dgk1Δ pah1Δ cells declined by 62%, and the amounts of fatty acids and phospholipids increased by 72 and 10%, respectively (Fig. 7). In contrast to dgk1Δ cells where the level of DAG increased by 45%, the amount of DAG in dgk1Δ pah1Δ cells remained fairly constant (Fig. 7). That the TAG stores in the dgk1Δ pah1Δ double mutant were much reduced when compared with wild type cells at the time of transfer to fresh growth medium may provide an explanation of why the mutant cells did not resume a more robust level of growth.

FIGURE 7.

Effect of the dgk1Δ pah1Δ mutations on the mobilization of TAG upon growth resumption from stationary phase in the presence of cerulenin. dgk1Δ pah1Δ mutant cells were grown to stationary phase in SC medium in the presence of [2-14C]acetate (1 μCi/ml) to uniformly label cellular lipids. The cells were then washed to remove the label and resuspended in fresh medium that contained 10 μg/ml cerulenin. At the indicated time points, cells were harvested, and lipids were extracted and separated by one-dimensional TLC. The 14C-labeled lipids were visualized by phosphorimaging and quantified by ImageQuant analysis. The percentages shown for the individual lipids were normalized to the total 14C-labeled chloroform-soluble fraction. The values reported are the average of three separate experiments ± S.D. (error bars). Data from Fig. 3 for Wild type and dgk1Δ mutant cells are included in the figure for comparison. For the clarity of the figure, the values for ergosterol and ergosterol ester are not shown. FA, fatty acids; PL, phospholipids.

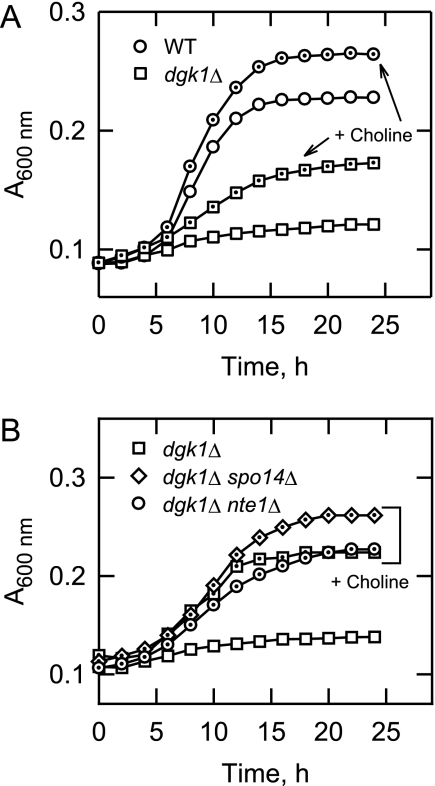

Choline Supplementation Partially Restores Growth of dgk1Δ Mutant Cells in the Presence of Cerulenin and Restores the Mobilization of TAG

We questioned whether the loss of DAG kinase function could be overcome by the addition of choline to the growth medium. The rationale for this experiment was that DAG would be consumed, and at the same time, PC would be synthesized. Choline is the water-soluble precursor used for PC synthesis via the CDP-choline branch of the Kennedy pathway (Fig. 1) (1, 53, 54). In this pathway, choline is transported into the cell and phosphorylated with ATP to form phosphocholine, which is then activated with CTP to produce CDP-choline (1, 53, 54). The CDP-choline then reacts with DAG to form the major membrane phospholipid PC (1, 53, 54). The supplementation of 1 mm choline to growth medium containing cerulenin allowed dgk1Δ mutant cells to resume growth from the stationary phase (Fig. 8A). Growth in the presence of 1 mm choline was not to the same extent as that observed for wild type cells grown without choline (generation times of 9.20 ± 0.15 and 3.60 ± 0.06 h, respectively) (Fig. 8A), and higher concentrations of choline (5 and 10 mm) did not have a further effect on growth resumption. Choline also stimulated the resumption of growth for wild type cells (Fig. 8A), indicating a beneficial effect of PC synthesis via the Kennedy pathway.

FIGURE 8.

Choline supplementation restores growth of dgk1Δ mutant cells in the presence of cerulenin, and the choline-mediated growth resumption does not require the SPO14- and NTE1-encoded phospholipases. A, Wild type and dgk1Δ mutant cells were grown to stationary phase in SC medium and then resuspended in fresh medium containing 10 μg/ml cerulenin and 1 mm choline where indicated. Growth after the transfer to fresh medium was monitored with a plate reader. Each data point represents the average of three independent cultures. The dot inside the symbols is where choline was present in the growth medium. The generation times for wild type, wild type plus choline, and dgk1Δ plus choline were 3.60 ± 0.06, 3.12 ± 0.05, and 9.20 ± 0.15 h, respectively. B, dgk1Δ, dgk1Δ spo14Δ, and dgk1Δ nte1Δ mutant cells were grown to stationary phase in SC medium and then resuspended in fresh medium containing 10 μg/ml cerulenin and 1 mm choline where indicated. Growth after the transfer to fresh medium was monitored with a plate reader. Each data point represents the average of three independent cultures. The dot inside the symbols is where choline was present in the growth medium. The generation times for dgk1Δ, dgk1Δ spo14Δ, and dgk1Δ nte1Δ mutant cells grown with choline were 9.20 ± 0.15, 11.2 ± 2.0, and 14.6 ± 1.0 h, respectively.

In the CDP-DAG pathway for phospholipid synthesis, PI, PS, PE, and PC are synthesized from CDP-DAG via PA (1). Because dgk1Δ cells cannot synthesize PA from DAG, we questioned whether cells supplemented with choline produced PA via PC turnover catalyzed by the SPO14-encoded phospholipase D (55). The dgk1Δ spo14Δ double mutant was constructed and examined for its ability to resume growth from stationary phase in the presence of choline and cerulenin. That this mutant resumed growth indicated that phospholipid synthesis was not dependent on the phospholipase D-mediated turnover of PC (Fig. 8B).

PC is also metabolized by the NTE1-encoded phospholipase B to produce fatty acids and glycerophosphocholine (56). This activity is induced by choline supplementation and may be specific for the PC synthesized via the Kennedy pathway (56–58). We addressed the possibility that this phospholipase B was required for dgk1Δ mutant cells to resume growth from stationary phase when cultured in the presence of choline and cerulenin. Deletion of NTE1 in the dgk1Δ mutant background (i.e. dgk1Δ nte1Δ) did not affect the ability of dgk1Δ cells to resume growth (Fig. 8B). This indicated that the phospholipase B did not provide fatty acids for phospholipid synthesis.

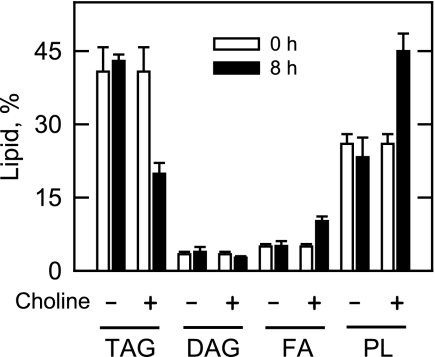

The resumption of logarithmic growth coincided with a reduction in the amount of TAG (50% by 8 h) and increases in the amounts of fatty acids (50% by 8 h) and phospholipids (41% by 8 h) when compared with cells grown without choline (Fig. 9). That the TAG in dgk1Δ cells was not mobilized to the same extent observed in wild type cells (Figs. 2B and 3A) may provide an explanation of why choline did not fully restore the growth to the level observed for wild type cells (Fig. 8A).

FIGURE 9.

Choline supplementation restores the utilization of TAG for phospholipid synthesis in dgk1Δ mutant cells grown in the presence of cerulenin. dgk1Δ mutant cells were grown to stationary phase in SC medium in the presence of [2-14C]acetate (1 μCi/ml) to uniformly label cellular lipids. The cells were then washed to remove the label and resuspended in fresh medium containing 10 μg/ml cerulenin and 1 mm choline where indicated. At the indicated time points, cells were harvested, and lipids were extracted and separated by one-dimensional TLC. The 14C-labeled lipids were visualized by phosphorimaging and quantified by ImageQuant analysis. The percentages shown for the individual lipids were normalized to the total 14C-labeled chloroform-soluble fraction. The values reported are the average of three separate experiments ± S.D. (error bars). For the clarity of the figure, the values for ergosterol and ergosterol ester are not shown. FA, fatty acids; PL, phospholipids.

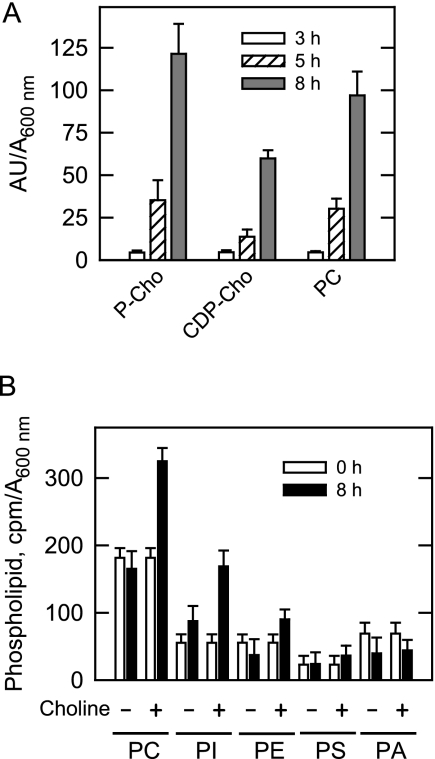

To confirm that the exogenous choline was incorporated into cellular PC via the Kennedy pathway, dgk1Δ cells grown with cerulenin were labeled with [methyl-14C]choline, followed by the extraction and analysis of the pathway intermediates and PC. The incorporation of labeled choline into phosphocholine, CDP-choline, and PC occurred in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 10A). The phospholipid composition was examined by labeling cells with 32Pi. The 32Pi will be incorporated into phospholipids synthesized by both the Kennedy and CDP-DAG pathways (59). The supplementation of choline to dgk1Δ mutant cells grown with cerulenin resulted in increases in the amounts of PC (49% by 8 h), PI (48% by 8 h), PE (58% by 8 h), and PS (36% by 8 h) when compared with cells not supplemented with choline (Fig. 10B). These data indicated that choline supplementation allowed cells to synthesize phospholipids by both pathways because PI and PS are only derived from CDP-DAG (1). Under this growth condition, the fatty acids derived from TAG would be used to synthesize PA for CDP-DAG-dependent phospholipid synthesis.

FIGURE 10.

Kennedy pathway intermediates and phospholipid composition in choline-supplemented dgk1Δ mutant cells grown in the presence of cerulenin. A, dgk1Δ mutant cells were grown to stationary phase in SC medium and then resuspended in fresh medium containing 10 μg/ml cerulenin and 1 mm [methyl-14C]choline (0.2 μCi/ml). At the indicated time points, cells were harvested, and the CDP-choline pathway intermediates and phosphatidylcholine were extracted and separated by one-dimensional TLC. The 14C-labeled compounds were visualized by phosphorimaging, and the amount of label (in arbitrary units (AU)) incorporated into each compound was quantified by ImageQuant analysis. The values reported are the average of three separate experiments ± S.D. P-Cho, phosphocholine; CDP-Cho, CDP-choline. B, dgk1Δ mutant cells were grown to stationary phase in SC medium in the presence of 32Pi (10 μCi/ml) to uniformly label cellular phospholipids. The cells were then resuspended in fresh medium containing 32Pi (10 μCi/ml), 10 μg/ml cerulenin, and 1 mm choline where indicated. At the indicated time points, cells were harvested, and phospholipids were extracted and separated by two-dimensional TLC. The 32P-labeled phospholipids were visualized by phosphorimaging, and the amount of label (cpm) incorporated into each phospholipid was determined by scintillation counting. The values reported are the average of three separate experiments ± S.D. (error bars).

Ethanolamine, the water-soluble precursor of PE synthesized by the CDP-ethanolamine branch of the Kennedy pathway (1), also permitted dgk1Δ cells to resume growth from stationary phase in the presence of cerulenin and also caused the mobilization of TAG for phospholipid synthesis (data not shown). However, the extent of growth with ethanolamine and the mobilization of TAG were not as great as those observed for choline supplementation (data not shown). Moreover, the effects of choline and ethanolamine on the resumption of growth of dgk1Δ mutant cells were neither synergistic nor additive (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

For yeast cells to resume vegetative growth from the stationary phase, they need a supply of lipid precursors (e.g. fatty acids) for the synthesis of membrane phospholipids (2, 3, 31–34). The initiation of this process requires the TGL3- and TGL4-mediated hydrolysis of TAG that is stored in lipid droplets (2, 3, 31–34). In the absence of TAG hydrolysis (e.g. in tgl3Δ tgl4Δ mutants), the resumption of vegetative growth is delayed until a steady state level of de novo fatty acid synthesis ensues (3, 31). In the absence of de novo fatty acid synthesis, stationary phase cells do not resume growth without TAG hydrolysis (3, 31). In this work, we discovered that DGK1-encoded DAG kinase activity was required in this process. Cells bearing a dgk1Δ mutation exhibited a lag in resuming growth from stationary phase, and in the presence of cerulenin, dgk1Δ mutant cells failed to resume growth and lost viability. The requirement of DGK1 in the process was attributed to DAG kinase activity because cells that expressed a catalytically inactive form of the enzyme had the same lack-of-growth phenotype as dgk1Δ mutant cells when cultured with cerulenin. The requirement of DAG kinase activity was further supported by the observation that in wild type cells, the level of DAG kinase activity was induced during growth resumption. The elucidation of this regulation (e.g. genetic and/or biochemical) will require additional studies.

Our experiments were conducted in the presence of cerulenin to accentuate the effects of the dgk1Δ mutation on growth resumption and lipid metabolism. The mobilization of TAG was defective in the absence of DGK1 under this condition. These results supported the hypothesis that the metabolism of TAG occurred through the sequence TAG → DAG → PA and that the PA derived from the DAG kinase reaction was used for membrane phospholipid synthesis to initiate cell growth. In addition, our work showed that in the presence of choline, PC could be synthesized via TAG-derived DAG and the Kennedy pathway. Contributions by the phospholipase B-mediated and phospholipase D-mediated hydrolysis of PC to produce fatty acids and PA, respectively, were not required for this metabolism.

An important question that arises from this work is how the DAG derived from TAG gets converted to phospholipids via PA and Kennedy pathways when the TGL3- and TGL4-encoded TAG lipases are associated with the surface of lipid droplets (31)5 but the DAG kinase and DAG cholinephosphotransferase (last step in the Kennedy pathway) enzymes are associated with the ER membrane (17, 60). The answer to this apparent dilemma may lie in the imaging studies of Goodman and co-workers (61) who have shown that >90% of lipid droplets in S. cerevisiae are associated with ER membranes. Thus, it is likely that the TAG lipase, DAG kinase, and DAG cholinephosphotransferase enzymes would be in close proximity to each other to catalyze the series of reactions needed to mobilize TAG. An alternative hypothesis is that the DAG derived from lipid droplet-associated TAG is translocated to the ER membrane for the utilization of the phospholipid-synthesizing enzymes. Definitive evidence for these hypotheses warrants further investigations.

This work also indicated that another function of DAG kinase was to alleviate the toxic effects of DAG. That increased DAG levels were toxic in S. cerevisiae was supported by the observations that dioctanoyl-DAG supplementation had an inhibitory effect on growth resumption of wild type cells, whereas in dgk1Δ mutant cells, the deletion of PAH1 as well as choline supplementation partially restored growth resumption. Loss of PA phosphatase activity reduces DAG production (4, 21), and choline supplementation increases DAG consumption (62). The role of DAG kinase activity in alleviating DAG toxicity was also supported by the fact that deletion of DGK1 in the dga1Δ mutant background causes a synthetic loss-of-growth phenotype (27). DGA1 encodes the DAG-consuming acyltransferase used for TAG synthesis, and the loss of this enzyme causes an accumulation of DAG (5). Thus, the additional loss of DAG kinase exacerbates the accumulation of DAG. Although not previously ascribed to DAG, the overproduction of hyperactive hypophosphorylated PA phosphatase and the overproduction of the NEM1-encoded protein phosphatase that dephosphorylates and activates PA phosphatase are toxic to cell growth, but the overproduction of DAG kinase alleviates this toxicity (20, 24). Precedence for a role of DAG kinase in alleviating the toxic effects of elevated levels of DAG was first reported in E. coli (63, 64).

The hydrolysis of TAG was inhibited in dgk1Δ mutant cells regardless of whether cerulenin was present in the growth medium. The reason for the lack of TAG lipase activity in these cells was unclear. There is no evidence for a direct inhibitory effect of DAG on TAG lipase activities (31). We cannot rule out the possibility that DAG or the lack of DAG kinase-mediated synthesis of PA signals the production of another molecule(s) that directly inhibits TAG lipase activities. In mammalian cells, the adipose TAG lipase is strongly activated by interaction with comparative gene identification-58 protein (65, 66). We considered the possibility that the DAG kinase, through protein-protein interaction, was required for the activation of the TAG lipases in yeast. However, this notion was ruled out because cells expressing the catalytic deficient DGK1(D177A) mutant allele exhibited the same loss-of-growth phenotype as the DGK1 deletion mutant. The TGL4-encoded TAG lipase is phosphorylated and activated by CDC28-encoded cyclin-dependent kinase, and this phosphorylation is required for the resumption of growth from the stationary phase, particularly in the presence of cerulenin (29). Thus, another explanation for the loss of TAG lipase activity in dgk1Δ mutant cells could be related to the lack of phosphorylation by cyclin-dependent kinase. Whether or not cyclin-dependent kinase activity is controlled directly or indirectly by the balance of PA and DAG is also unknown. These questions warrant further examination.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gil-Soo Han for helpful suggestions during the course of this work and comments on the preparation of the manuscript. We also thank Sepp Kohlwein for helpful discussions and unpublished information on the association of TGL3-encoded TAG lipase with lipid droplets. We thank Christopher McMaster (PMY201) and JoAnne Engebrecht (pME913) for reagents to delete the NTE1 and SPO7 genes, respectively, in the dgk1Δ mutant.

- PA

- phosphatidate

- DAG

- diacylglycerol

- TAG

- triacylglycerol

- PC

- phosphatidylcholine

- PE

- phosphatidylethanolamine

- PI

- phosphatidylinositol

- PS

- phosphatidylserine

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- SC

- synthetic complete.

REFERENCES

- 1. Carman G. M., Han G. S. (2009) J. Lipid Res. 50, S69–S73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rajakumari S., Grillitsch K., Daum G. (2008) Prog. Lipid Res. 47, 157–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kohlwein S. D. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 15663–15667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Han G. S., Wu W. I., Carman G. M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 9210–9218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Oelkers P., Cromley D., Padamsee M., Billheimer J. T., Sturley S. L. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 8877–8881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oelkers P., Tinkelenberg A., Erdeniz N., Cromley D., Billheimer J. T., Sturley S. L. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 15609–15612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Waggoner D. W., Xu J., Singh I., Jasinska R., Zhang Q. X., Brindley D. N. (1999) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1439, 299–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sciorra V. A., Morris A. J. (2002) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1582, 45–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Testerink C., Munnik T. (2005) Trends Plant Sci. 10, 368–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang X., Devaiah S. P., Zhang W., Welti R. (2006) Prog. Lipid Res. 45, 250–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brindley D. N. (2004) J. Cell. Biochem. 92, 900–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Howe A. G., McMaster C. R. (2006) Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 84, 29–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Foster D. A. (2007) Cancer Res. 67, 1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bishop W. R., Ganong B. R., Bell R. M. (1986) J. Biol. Chem. 261, 6993–7000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kearns B. G., McGee T. P., Mayinger P., Gedvilaite A., Phillips S. E., Kagiwada S., Bankaitis V. A. (1997) Nature 387, 101–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Carrasco S., Mérida I. (2007) Trends Biochem. Sci. 32, 27–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Han G. S., O'Hara L., Carman G. M., Siniossoglou S. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 20433–20442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Han G. S., O'Hara L., Siniossoglou S., Carman G. M. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 20443–20453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Karanasios E., Han G. S., Xu Z., Carman G. M., Siniossoglou S. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 17539–17544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Santos-Rosa H., Leung J., Grimsey N., Peak-Chew S., Siniossoglou S. (2005) EMBO J. 24, 1931–1941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Han G. S., Siniossoglou S., Carman G. M. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 37026–37035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Loewen C. J., Gaspar M. L., Jesch S. A., Delon C., Ktistakis N. T., Henry S. A., Levine T. P. (2004) Science 304, 1644–1647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Carman G. M., Henry S. A. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 37293–37297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. O'Hara L., Han G. S., Peak-Chew S., Grimsey N., Carman G. M., Siniossoglou S. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 34537–34548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Taylor F. R., Parks L. W. (1979) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 575, 204–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Petschnigg J., Wolinski H., Kolb D., Zellnig G., Kurat C. F., Natter K., Kohlwein S. D. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 30981–30993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Garbarino J., Padamsee M., Wilcox L., Oelkers P. M., D'Ambrosio D., Ruggles K. V., Ramsey N., Jabado O., Turkish A., Sturley S. L. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 30994–31005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goodman J. M. (2009) J. Lipid Res. 50, 2148–2156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kurat C. F., Wolinski H., Petschnigg J., Kaluarachchi S., Andrews B., Natter K., Kohlwein S. D. (2009) Mol. Cell 33, 53–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rajakumari S., Daum G. (2010) Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 501–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kurat C. F., Natter K., Petschnigg J., Wolinski H., Scheuringer K., Scholz H., Zimmermann R., Leber R., Zechner R., Kohlwein S. D. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 491–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Athenstaedt K., Daum G. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 23317–23323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Athenstaedt K., Daum G. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 37301–37309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zanghellini J., Natter K., Jungreuthmayer C., Thalhammer A., Kurat C. F., Gogg-Fassolter G., Kohlwein S. D., von Grünberg H. H. (2008) FEBS J. 275, 5552–5563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rose M. D., Winston F., Heiter P. (1990) Methods in Yeast Genetics: A Laboratory Course Manual, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sambrook J., Fritsch E. F., Maniatis T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd Ed., Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 37. Omura S. (1981) Methods Enzymol. 72, 520–532 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Inokoshi J., Tomoda H., Hashimoto H., Watanabe A., Takeshima H., Omura S. (1994) Mol. Gen. Genet. 244, 90–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhang Q., Chieu H. K., Low C. P., Zhang S., Heng C. K., Yang H. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 47145–47155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zwietering M. H., Jongenburger I., Rombouts F. M., van 't Riet K. (1990) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56, 1875–1881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ito H., Fukuda Y., Murata K., Kimura A. (1983) J. Bacteriol. 153, 163–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Innis M. A., Gelfand D. H. (1990) in PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications (Innis M. A., Gelfand D. H., Sninsky J. J., White T. J. eds) pp. 3–12, Academic Press, Inc., San Diego [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rothstein R. (1991) Methods Enzymol. 194, 281–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rudge S. A., Sciorra V. A., Iwamoto M., Zhou C., Strahl T., Morris A. J., Thorner J., Engebrecht J. (2004) Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 207–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bligh E. G., Dyer W. J. (1959) Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37, 911–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Homan R., Anderson M. K. (1998) J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Sci. Appl. 708, 21–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Christie W. W. (2003) Lipid Analysis, Barnes, Bridgwater, UK [Google Scholar]

- 48. Klig L. S., Homann M. J., Carman G. M., Henry S. A. (1985) J. Bacteriol. 162, 1135–1141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bradford M. M. (1976) Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Müller M. O., Meylan-Bettex M., Eckstein F., Martinoia E., Siegenthaler P. A., Bovet L. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 19475–19481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Czabany T., Athenstaedt K., Daum G. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1771, 299–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Carman G. M., Han G. S. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 2593–2597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kennedy E. P. (1986) in Lipids and Membranes: Past, Present, and Future (Op den Kamp J. A. F., Roelofsen B., Wirtz K. W. A., eds) pp. 171–206, Elsevier Science Publishers B.V., Amsterdam [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kent C., Carman G. M. (1999) Trends Biochem. Sci. 24, 146–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rose K., Rudge S. A., Frohman M. A., Morris A. J., Engebrecht J. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 12151–12155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zaccheo O., Dinsdale D., Meacock P. A., Glynn P. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 24024–24033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Dowd S. R., Bier M. E., Patton-Vogt J. L. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 3756–3763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fernández-Murray J. P., McMaster C. R. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1771, 331–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. McDonough V. M., Buxeda R. J., Bruno M. E., Ozier-Kalogeropoulos O., Adeline M. T., McMaster C. R., Bell R. M., Carman G. M. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 18774–18780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Huh W. K., Falvo J. V., Gerke L. C., Carroll A. S., Howson R. W., Weissman J. S., O'Shea E. K. (2003) Nature 425, 686–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Szymanski K. M., Binns D., Bartz R., Grishin N. V., Li W. P., Agarwal A. K., Garg A., Anderson R. G., Goodman J. M. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 20890–20895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. McMaster C. R., Bell R. M. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 14776–14783 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Raetz C. R., Newman K. F. (1978) J. Biol. Chem. 253, 3882–3887 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Jackson B. J., Bohin J. P., Kennedy E. P. (1984) J. Bacteriol. 160, 976–981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Gruber A., Cornaciu I., Lass A., Schweiger M., Poeschl M., Eder C., Kumari M., Schoiswohl G., Wolinski H., Kohlwein S. D., Zechner R., Zimmermann R., Oberer M. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 12289–12298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lass A., Zimmermann R., Haemmerle G., Riederer M., Schoiswohl G., Schweiger M., Kienesberger P., Strauss J. G., Gorkiewicz G., Zechner R. (2006) Cell Metab. 3, 309–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Irie K., Takase M., Araki H., Oshima Y. (1993) Mol. Gen. Genet. 236, 283–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kosodo Y., Imai K., Hirata A., Noda Y., Takatsuki A., Adachi H., Yoda K. (2001) Yeast 18, 1003–1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Brachmann C. B., Davies A., Cost G. J., Caputo E., Li J., Hieter P., Boeke J. D. (1998) Yeast 14, 115–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wimmer C., Doye V., Grandi P., Nehrbass U., Hurt E. C. (1992) EMBO J. 11, 5051–5061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Sikorski R. S., Hieter P. (1989) Genetics 122, 19–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]