Abstract

Cross-talk between Gαi- and Gαq-linked G-protein-coupled receptors yields synergistic Ca2+ responses in a variety of cell types. Prior studies have shown that synergistic Ca2+ responses from macrophage G-protein-coupled receptors are primarily dependent on phospholipase Cβ3 (PLCβ3), with a possible contribution of PLCβ2, whereas signaling through PLCβ4 interferes with synergy. We here show that synergy can be induced by the combination of Gβγ and Gαq activation of a single PLCβ isoform. Synergy was absent in macrophages lacking both PLCβ2 and PLCβ3, but it was fully reconstituted following transduction with PLCβ3 alone. Mechanisms of PLCβ-mediated synergy were further explored in NIH-3T3 cells, which express little if any PLCβ2. RNAi-mediated knockdown of endogenous PLCβs demonstrated that synergy in these cells was dependent on PLCβ3, but PLCβ1 and PLCβ4 did not contribute, and overexpression of either isoform inhibited Ca2+ synergy. When synergy was blocked by RNAi of endogenous PLCβ3, it could be reconstituted by expression of either human PLCβ3 or mouse PLCβ2. In contrast, it could not be reconstituted by human PLCβ3 with a mutation of the Y box, which disrupted activation by Gβγ, and it was only partially restored by human PLCβ3 with a mutation of the C terminus, which partly disrupted activation by Gαq. Thus, both Gβγ and Gαq contribute to activation of PLCβ3 in cells for Ca2+ synergy. We conclude that Ca2+ synergy between Gαi-coupled and Gαq-coupled receptors requires the direct action of both Gβγ and Gαq on PLCβ and is mediated primarily by PLCβ3, although PLCβ2 is also competent.

Keywords: Calcium, Complement, Fibroblast, G Protein-coupled Receptors (GPCR), Macrophage, Phosphatidylinositol, Phospholipase C, Purinergic Receptor, Signal Transduction

Introduction

Phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C (PLC)5-dependent Ca2+ responses are stimulated by several types of cell surface receptors, including members of the GPCR family. Gαq-linked GPCRs stimulate Ca2+ responses in most cells, whereas Gαi-linked receptor stimulation of Ca2+ release is variably seen, and the factors that determine this variation are not well understood (1–3). Simultaneous activation of Gαi- and Gαq-linked GPCRs has revealed pathway cross-talk, resulting in synergistic Ca2+ responses in a variety of primary and cultured cell types (4–10). Proposed mechanisms have included effects on receptor availability, changes in G-protein turnover, increased availability of the PLCβ substrate phosphatidylinositol 4,5-diphosphate, increased sensitivity of intracellular stores to inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate, and enhanced linkage of intracellular Ca2+ release to Ca2+ influx (5). From these disparate results, it is clear that the mechanisms for Ca2+ synergy may vary between systems and contexts.

We recently demonstrated that Gαi- and Gαq-coupled GPCRs synergize in stimulating a rise in [Ca2+]i in macrophages (11). Synergy required simultaneous receptor activation, and it affected both the initial release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores and the sustained elevation in Ca2+ levels. Similar to synergy in other cell types, synergy in macrophages occurred at the level of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate production (10, 12–16). Although macrophages express multiple PLCβ isoforms, these were used selectively in Ca2+ signaling and synergy. In particular, PLCβ3 mediated most of the synergy, with a possible minor contribution by PLCβ2, whereas PLCβ4 inhibited synergy (11). In contrast to the synergy in PLCβ activation, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activation was inhibited by the same signal interactions, demonstrating divergence in signaling effects on effector pathways downstream of the GPCRs.

Previous biochemical investigations of PLCβ isoforms have demonstrated differential sensitivity to activation by G-protein subunits; whereas PLCβ2 and PLCβ3 bind to and are activated by both Gβγ and Gαq, PLCβ4 is effectively activated only by Gαq (17–20). At the receptor level, Gαi-linked GPCRs activate PLCβ through binding of Gβγ alone, whereas signaling through Gαq-linked GPCRs may activate PLCβ through both Gβγ and Gαq. Thus, synergy in Ca2+ signaling could involve effects of both Gβγ and Gαq on PLCβ2 or PLCβ3. Alternatively, it could involve activation of PLCβ by only one of the two G-proteins. For example, synergy could involve only Gβγ interactions between receptors, especially if different Gβγ subunits were used by each receptor (21). Synergy could also be mediated solely by Gαq, with increased Gβγ levels serving to enhance the recycling of GTP-Gαq, but this is unlikely because this effect should enhance the activity of PLCβ4, and it does not (11).

In the current studies, we further examined the mechanistic requirements for PLCβ-mediated Ca2+ synergy responses. Studies of PLCβ-deficient primary macrophages revealed that only one PLCβ isoform is required for synergy, either PLCβ3 or, less potently, PLCβ2.

To dissect the molecular mechanisms involved in synergy, we employed a cellular system with a greater efficiency of transfection and higher throughput than primary BMDMs, mouse NIH-3T3 cells expressing C5aR. This model permits Gαi-mediated signaling in response to C5a together with Gαq-mediated signaling through endogenous P2Y receptors in response to UDP or UTP.

Studies of the NIH-3T3 model supported and extended the observations in macrophages. They demonstrated a robust synergistic Ca2+ response to C5a and UDP and demonstrated that synergy is dependent on endogenous PLCβ3. In contrast, PLCβ1 or PLCβ4 inhibited synergy, and inhibition by PLCβ4 required its C-terminal, Gαq binding site. Following knockdown of PLCβ3 by RNAi, synergy could be restored by expression of either human PLCβ3 (hPLCβ3) or mouse PLCβ2 (mPLCβ2), which is not expressed natively in these cells.

Mutational analyses of hPLCβ3 revealed that both Gβγ and Gαq binding sites are necessary for full synergistic activation of PLCβ3 in 3T3 cells, confirming the requirement for both activators of PLCβ3 in intact cells. We conclude that synergy between Gβγ and Gαq occurs directly at the level of PLCβ3.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

UDP, UTP, LPA, platelet-activating factor, human C5a, spiradoline, and FITC-dextran were from Sigma-Aldrich. S1P was from Avanti Polar Lipids. Mouse IgG2a was from BD Pharmaceuticals. F(ab′)2 fragments of goat anti-mouse IgG were from Jackson Immunoresearch Inc. Anti-PLCβ3 clone B521 was from Paul Sternweis (University of Texas Southwestern) (17). Anti-phospho-Akt and anti-phospho-ERK were from Cell Signaling Technologies. Fura2 was from Molecular Probes. Ionomycin, thapsigargin, and pertussis toxin (PTx) were from Calbiochem. Detailed protocols for reagents, procedures, and solutions are provided upon request and are referenced according to protocol number (e.g. PP00000172).

Culture of NIH-3T3 Cells

NIH-3T3 cells were maintained in DMEM with 10% FBS and 2 mm l-glutamine (PS00000663).

Mice and Culture of BMDMs

PLCβ3-deficient mice were on a C57BL/6 background after 7 generations of backcrossing (22), and PLCβ2-deficient mice were on 129SvEV background (23). For mice doubly deficient in PLCβ3 and PLCβ2, PLCβ2−/− mice were crossed twice to C57BL/6 mice and a PLCβ2+/− mouse was crossed to PLCβ3−/− mice. Mice were bred and housed under approved animal protocols. To obtain BMDMs, femurs and tibias were removed from sex- and age-matched mice (4–20 weeks of age, matched ±4 weeks) (PP00000172). Briefly, marrow was flushed from bones, erythrocytes were lysed, and the white cells were seeded in non-tissue culture Petri dishes for differentiation and selection of macrophages by growth and adhesion. After 6 days, over 99% of the surviving cells were macrophages, as assessed by expression of CD11b/αM integrin and CD115/c-Fms/MCSF receptor, and these cells were maintained in culture for up to 35 days. Cells were cultured overnight in tissue culture plates prior to use in assays.

Cell Transduction with siRNA, Plasmid Expression Constructs, and Retroviruses

For RNAi, 3T3 cells were plated at 1.25 × 105 cells/well in 6-well plates 24 h prior to transfection. Lipofectamine 2000 was used to deliver siRNA oligonucleotides at a final concentration of 100 nm. Media were changed 24 h post-transfection, and cells were plated for assay 48 h post-transfection (PP00000262). Bioassays and sampling for mRNA and protein expression level assessments were performed 72 h post-transfection. Knockdown efficiency of mRNA was quantified by quantitative RT-PCR, and proteins were quantified by Western blotting where antibodies were available.

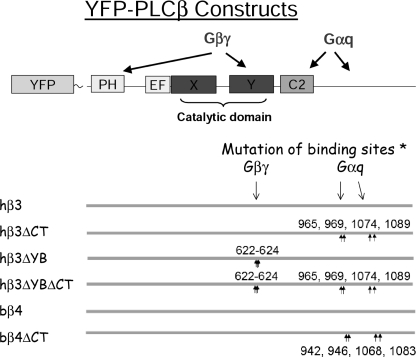

The cDNA for human C5aR, with an N-terminal FLAG epitope, was generously provided by Henry Bourne (University of California San Francisco) and was transferred to pcDNA4zeo (Invitrogen). The cDNA for the mutant κ-opioid receptor (RASSL form Ro2 (24)) was generously provided by Bruce Conklin (University of California San Francisco) and was transferred to pMXpie (25). Murine, human, and bovine PLCβ-YFP fusion proteins and mutant constructs were prepared by using previously described cloning methods and constructs (26). The domain structure of PLCβ is shown in Fig. 1, where previously demonstrated binding sites for Gβγ and Gαq are indicated (reviewed in Ref. 27). Residues in the Y-box and the C-terminal domains of either PLCβ3 or PLCβ4 were targeted for mutation to interfere with Gβγ or Gαq binding, respectively. Briefly, hPLCβ3 and bovine PLCβ4 cDNAs were cloned in gateway entry vectors, and site-directed mutagenesis was directed at putative G-protein interaction sites by using QuikChange® (Stratagene), according to the method of the manufacturer. For both hPLCβ3 and bovine PLCβ4, four amino acids that are predicted to contribute to Gαq interaction at the C terminus (hPLCβ3: Lys965, Arg969, Asp1074, and Arg1089; bovine PLCβ4: Lys942, Lys946, Ser1068, and Arg1083) were mutated to alanine (28, 29). For hPLCβ3, three amino acids that are predicted to contribute to Gβγ interaction (Glu622, Thr623, and Lys624) were also mutated to alanine (30, 31). For mPLCβ2, a stop codon was introduced after amino acid 840. N-terminal YFP tags were added to PLCβ sequences by Gateway (Invitrogen) recombination to either pDS_EF1-YFP-XB for mammalian plasmid expression or to pDS-FBneo YFP-X for retroviral expression (AfCS plasmids, available through ATCC). Control constructs were either empty vector, YFP alone, or YFP-FLAG versions. For in vitro assessment of hPLCβ3 mutants, the recombinant proteins were produced via the baculovirus expression vector system. His tags were added to the C termini, the sequences were transferred to pFastBac1 vectors, SF9 cells were transfected, and the proteins were purified from cell lysates by one-step affinity chromatography on Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose (Qiagen) (28).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic of PLCβ structure and design of G-protein binding site mutants. The theoretical PLCβ structural domain organization (NCBI) is shown along with sites of modification as described under “Experimental Procedures.” YFP was added as an N-terminal fusion protein, and point mutations targeting Gβγ and Gαq binding sites, based on homology to PLCβ1, were created as X → Ala mutations (*). The arrows indicate the location of amino acids mutated, and the numbers indicate their position relative to the N terminus of hPLCβ3. The species of isoform used is indicated as human (h) and bovine (b). Also used but not shown are YFP-mPLCβ1, -2, -3, and -4 without mutation and mPLCb2 truncated at amino acid 840.

3T3 cells were transfected with stable mammalian expression vectors by using Lipofectamine 2000. Amphotropic or ecotropic retroviruses were produced by using the Phoenix (32) or PlatE (33) packaging lines, respectively, with pMXpie or pFB-neo (Stratagene) vectors. 3T3 cells were selected and maintained in 100 μg/ml zeocin, 400 μg/ml G418, or 1 μg/ml puromycin, either alone or in combination as appropriate. Where required, fluorescent cell populations were enriched by cell sorting by using a FACSAria (BD Biosciences). Expression levels were evaluated by Western blotting using anti-PLCβ3. The molecular weight difference between endogenous PLCβ3 and transduced YFP-PLCβ3 allowed differentiation of bands corresponding to each form.

Primary BMDMs were transduced by using retroviruses. Proliferating myeloid progenitor cells were infected on two consecutive days, beginning within 2 days of isolation from mouse femurs. Overnight infections with retrovirus-containing supernatants included Polybrene at 8 μg/ml. After expansion, transduced macrophages were harvested and replated on tissue culture plastic or poly-l-lysine-coated glass chamber slides 24 h prior to assay.

In Vitro PLCβ Activity Assays

PLC activity was measured by hydrolysis of [3H]phosphatidylinositol 4,5-diphosphate as described previously (28, 34). Briefly, the reactions of purified PLCβ enzymes, G-protein subunits, and [3H]phosphatidylinositol 4,5-diphosphate (added as mixed phospholipid vesicles) were allowed to proceed at 30 °C for 10 min. Ca2+ was maintained at 0.2 μm. Gαq-stimulated activity was measured in the presence of (0.2 or) 2 nm Gαq (∼EC50) that had been previously activated by incubation with GTPγS. Gβγ-stimulated activity was measured in the presence of 30 nm Gβγ.

Population Calcium Assays

Ca2+ responses were measured by monitoring the fluorescence of Fura-2-loaded cells (PP00000211). Base-line readings were collected for 30–40 s prior to stimulation with ligands. Calibration steps included the additions of a Ca2+-minimizing solution (PS00000607) and Fura-2 Ca2+-saturating solution (PS00000608) at the end of each recording to allow calculation of [Ca2+]i values according to the method of Grynkiewicz et al. (52), assuming a cytoplasmic kD value of 250 nm for Fura-2. Ca2+ signals during the response period were quantified by features as indicated, including the peak offset response (difference between base-line Ca2+ level and the maximal Ca2+ level observed, reported in nm) and an integrated response (integrated Ca2+ level above the average base line over the indicated time period, reported in nm × s).

Single-cell Calcium Assays

Cells were plated in chambered coverglasses (Nunc, 8 wells/coverglass), cultured overnight, and loaded with Fura-2/AM as described above. Video microscopy was performed by using a Nikon TE-300 fluorescence microscope equipped with a Photometrics HQ2 camera, 37 °C stage incubator (Bionomics), xenon lamp (Sutter), and filter/shutter/dichroic controllers (Sutter and Conix). SimplePCI software was used to control collection parameters and to extract fluorescence intensity data for individual cells. Intracellular [Ca2+]i was estimated as described for population assays.

Statistical Analyses

The error bars in graphs depict the S.E. The statistical significance of each comparison was evaluated by performing Student's t test or a one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's test or individual t tests (with Bonferroni correction). A p value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Macrophages Deficient in Both PLCβ2 and PLCβ3 Have No Synergistic Ca2+ Response to C5a and UDP

Synergy in Ca2+ signaling in macrophages between C5a, acting on the Gαi-coupled C5aR, and UDP, acting on Gαq-coupled P2Y receptors, was previously found to be primarily dependent on expression of PLCβ3, but some synergy remained in PLCβ3-deficient cells (11). Because PLCβ4 appears to have an inhibitory role and PLCβ1 is not expressed in macrophages, the residual Ca2+ synergy in PLCβ3-deficient macrophages was thought to depend on PLCβ2 (11). To test this hypothesis, we examined Ca2+ synergy in mouse macrophages deficient in both PLCβ2 and PLCβ3 (PLCβ2/3−/−) in comparison with macrophages deficient in PLCβ3 alone (PLCβ3−/−). In the absence of both PLCβ2 and PLCβ3, BMDMs (which still expressed PLCβ4) lost the residual synergy that was apparent in macrophages deficient in PLCβ3 alone (Fig. 2, A–C). Thus, although synergy in macrophages is primarily dependent on PLCβ3, PLCβ2 is capable of supporting synergy.

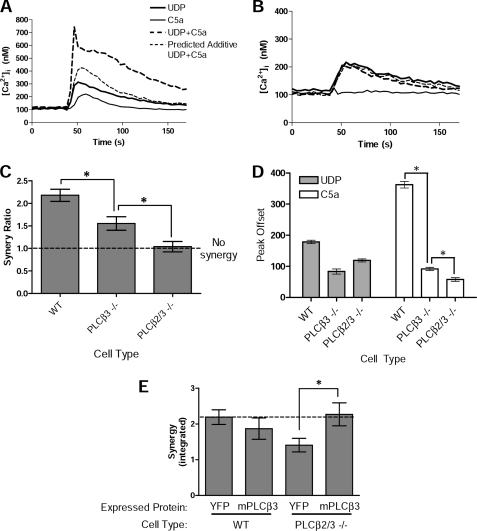

FIGURE 2.

Ca2+ synergy in BMDMs depends primarily on PLCβ3 with a small contribution by PLCβ2. BMDMs from WT, PLCβ3-deficient (PLCβ3−/−), or double PLCβ2- and PLCβ3-deficient (PLCβ2/3−/−) mice were assayed for their ability to reflect synergistic responses to C5a plus UDP. Intracellular Ca2+ responses were measured in Fura-2-loaded cells stimulated with C5a (0.75 nm), UDP (500 nm), or both ligands. Responses from WT (A) and PLCβ2/3−/− (B) BMDMs are indicated by the line graphs, in which each line represents the average of 3–4 individual wells/assay. Data shown are from representative experiments of n = 18 with similar results. C, summary of synergy responses from WT, PLCβ3−/−, and PLCβ2/3−/− BMDMs. The predicted additive responses for dual-ligand stimulation were calculated for each assay from the measured single-ligand responses, and a synergy ratio was determined as the ratio of the observed/predicted additive dual-ligand responses, using the peak offset feature. Values shown are mean ± S.E. from n = 18–20 replicate assays/condition. D and E, single-ligand Ca2+ responses in PLCβ-deficient BMDMs. D, wild-type, PLCβ3−/−, and PLCβ2/3−/− cells were stimulated with C5a (10 nm) or UDP (10 μm), and the Ca2+ responses were measured. Shown are the results for peak offset responses. Results are mean ± S.E. from n = 3 assays. *, p < 0.05. E, expression of mPLCβ3 in PLCβ2/3−/− BMDMs restores synergistic Ca2+ responses to levels observed in WT BMDMs. Single-cell Ca2+ assays were performed on WT or PLCβ2/3−/− BMDMs transduced with retrovirus encoding YFP-FLAG or YFP-mPLCβ3. Cells were stimulated with C5a (0.75 nm), UDP (500 nm), or C5a + UDP, and the Ca2+ responses were measured by integration over 2.25 min. Responses by transduced cells were measured in multiple assays of each of three independent batches of infected BMDMs. Values shown are mean ± S.E. from n = 5–6 samples per condition. *, p < 0.05.

The Ca2+ response to UDP alone in PLCβ2/3−/− macrophages differed little from the response by macrophages deficient in PLCβ3 alone (Fig. 2D), presumably reflecting activation of PLCβ4 by Gαq, but the Ca2+ response to C5a alone was diminished in PLCβ2/3−/− BMDMs compared with macrophages deficient in PLCβ3 alone, indicating a contribution from PLCβ2.

Reconstitution of PLCβ2/3-deficient BMDMs with PLCβ3 Alone Restores Synergy

The capacity of PLCβ3 alone to support Ca2+ synergy was evaluated by reconstituting wild type or PLCβ2/3-deficient BMDMs with PLCβ3 coupled to YFP or, as a control, with FLAG peptide coupled to YPF. Introduction of wild-type PLCβ3 increased single-ligand responses to both C5a and UDP, and it restored synergy to normal levels (Fig. 2E and supplemental Fig. S1). Thus, synergy can be supported by either PLCβ2 or PLCβ3 alone.

In these studies, transduction of PLCβ into BMDMs was inefficient, requiring the study of large numbers of cells to obtain statistically valid results. Therefore, for further studies of the role of PLCβ isoforms in synergy, we moved to the study of NIH-3T3 cells stably expressing C5aR, beginning with validation of these cells as a model for synergy in Ca2+ signaling between Gαi- and Gαq-coupled receptors.

NIH-3T3 Cells Demonstrate Robust Synergy in Ca2+ Signaling in Response to Endogenous Purinergic Receptors (P2YRs) and a Stably Transfected C5a Receptor (C5aR)

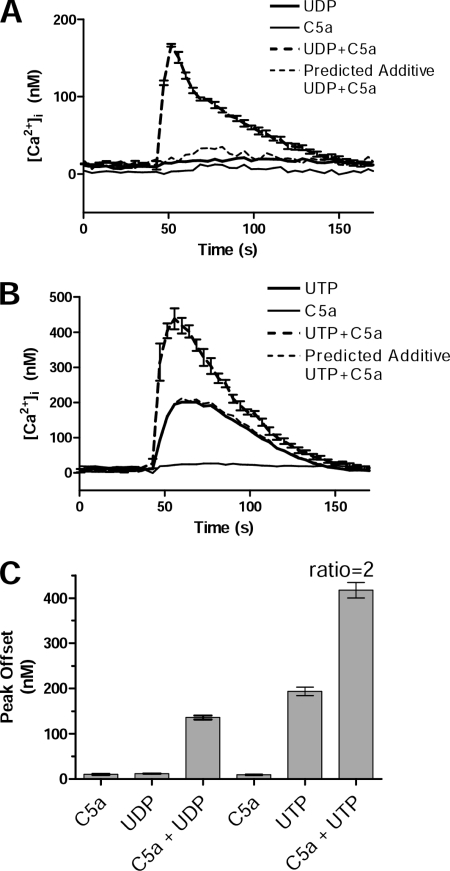

Mechanistic studies of the signaling interaction between C5a and UDP or UTP GPCRs at the level of PLCβ activation were performed in mouse NIH-3T3 cells expressing a stably transfected human C5aR and endogenous P2YRs. Robust synergy between C5a and either UDP (Fig. 3A) or UTP (Fig. 3B) was observed, both in the initial peak and in sustained levels of [Ca2+]i. C5a or UDP alone generated low or undetectable Ca2+ responses, even at concentrations up to 100 μm (Fig. 3B and supplemental Figs. S2 and S3). Substituting UTP for UDP, however, consistently gave a detectable response by itself, and this was elevated by C5a to levels 2–4 times the predicted additive value (Fig. 3C). Of note, C5a increased Ca2+ responses to UTP even when UTP was used at maximal concentrations, evidence that C5a recruits signaling pathways that are not utilized by UTP.

FIGURE 3.

C5a in combination with UTP or UDP yields synergistic Ca2+ responses in NIH-3T3 cells. Intracellular Ca2+ levels were calculated for Fura-2-loaded NIH-3T3 cells stably expressing the human C5aR in kinetic assays in 96-well plates. After 40 s base-line readings, cells were stimulated with UDP (100 μm), UTP (100 μm), C5a (10 nm), or a combination of these ligands, and responses were monitored for 2.5 min. Shown are a combination of C5a + UDP (A) and a combination of C5a + UTP (B). Each line in the graphs represents the average of 4–5 individual wells/assay, and the error bars (S.E.) are shown for the dual-ligand line in each graph. Synergy was evaluated by comparing the experimentally observed dual-ligand responses to the predicted additive responses of the individual ligands. C, the responses were quantified by using peak offset measurements, the difference from base line to observed peak. The dual-ligand responses were compared with the predicted additive responses (sum of single-ligand responses) and a synergy ratio calculated as observed/predicted additive peak offsets. For the C5a + UTP experiment shown, the synergy ratio was 2, but the predicted additive level for C5a + UDP was too low for reliable estimation of the synergy ratio. Data shown are from a representative assay of n = 7 with similar results.

To confirm that NIH-3T3 cells serve as an adequate model for synergy in Ca2+ signaling between Gαi- and Gαq-linked GPCRs, we evaluated synergy by a number of alternate receptor pairings with or without inhibition of Gαi signaling by PTx. As expected, the C5a and synergistic responses to UTP + C5a were sensitive to PTx (supplemental Fig. S4), whereas the responses to UTP were not (supplemental Fig. S5A), as seen previously in BMDMs (11). Endogenous LPA and S1P receptors generated PTx-sensitive Ca2+ responses (supplemental Fig. S5A), as did a transfected modified κ-opioid GPCR, Ro2 (24), which signals solely through Gαi in response to spiradoline (supplemental Figs. S5C and S6). A screen of dual-ligand Ca2+ responses showed that pairs of receptors with heterologous couplings to Gαi and Gαq showed synergy, whereas homologous couplings did not (supplemental Fig. S5, B and D; summarized in supplemental Table S1). Thus, Ca2+ synergy in NIH-3T3 cells reflects Gαq/Gαi GPCR cross-talk, as it does in macrophages and several other cell types.

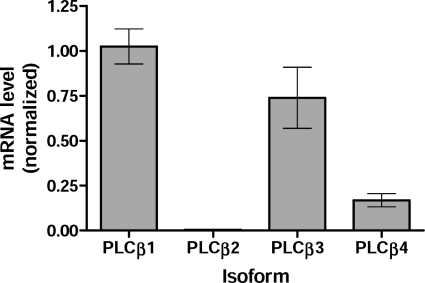

Ca2+ Synergy in NIH-3T3 Cells Depends on Endogenous PLCβ3

We next sought to determine the contribution of different PLCβ isoforms to Ca2+ signaling in NIH-3T3 cells. By quantitative RT-PCR, NIH-3T3 cells expressed relatively high levels of PLCβ1 and PLCβ3 transcripts but lower levels of PLCβ4 and little or no PLCβ2 (Fig. 4). Expression of each isoform was selectively reduced by RNAi, which reduced transcripts for PLCβ1, PLCβ3, and PLCβ4 by 60–80% (supplemental Fig. S7A). Only the knockdown of PLCβ3 significantly reduced the Ca2+ synergy response (Fig. 5). Knockdown of PLCβ2 had no effect, but this isoform is not significantly expressed in NIH-3T3 cells, so this may be viewed as an additional negative control. Knockdown of PLCβ1 or PLCβ4 increased synergy, but this change did not reach statistical significance for either isoform. These results are similar to our results in genetically deficient BMDMs, where the absence of PLCβ3 reduced synergy, whereas the absence of PLCβ4 enhanced synergy (PLCβ1 is the closest isoform to PLCβ4 biochemically (27)). Hence, our results in both BMDMs and NIH-3T3 cells indicate that PLCβ3 contributes to synergy in Ca2+ signaling, whereas PLCβ4 or PLCβ1 do not and instead inhibit synergy. Knockdown of single PLCβ isoforms did not significantly alter single-ligand Ca2+ responses; responses to C5a were too low to identify changes, whereas UTP responses were not affected by knockdown of PLCβ2 or PLCβ3 and only slightly affected by knockdown of PLCβ1. Presumably, the loss of individual PLCβ isoforms following RNAi is compensated by signaling through others, all of which can bind Gαq.

FIGURE 4.

Expression of PLCβ isoforms in NIH-3T3 cells. Quantitative RT-PCR was used to measure PLCβ isoform mRNA levels. mRNA levels were compared with β-actin in each assay and normalized to PLCβ1 levels. Data are mean ± S.E. (error bars) from three assays.

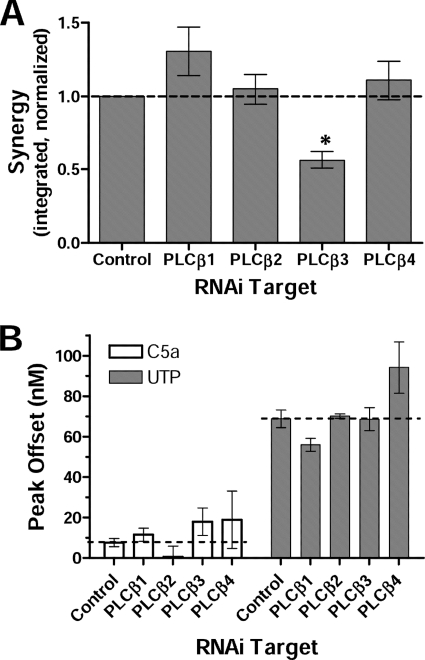

FIGURE 5.

Knockdown of PLCβ3 in NIH-3T3 cells reduces C5a + UTP Ca2+ synergy. siRNA-mediated knockdown of PLCβ isoforms in NIH-3T3-C5aR cells preceded assays of C5a + UTP Ca2+ synergy. PLCβ isoform-specific siRNA versus LacZ control siRNA were applied to cells 72 h prior to assay. A, cells were stimulated with UTP (100 μm), C5a (10 nm) or UTP + C5a. Integrated measures of synergy were normalized to responses of control cells in each assay (dotted line, representing an average synergy ratio of 3.5). B, single-ligand responses following PLCβ isoform-specific RNAi. Peak offset values were calculated for each response. Results are mean ± S.E. (error bars) from n = 3–5 assays/condition from independent rounds of RNAi. *, p < 0.05.

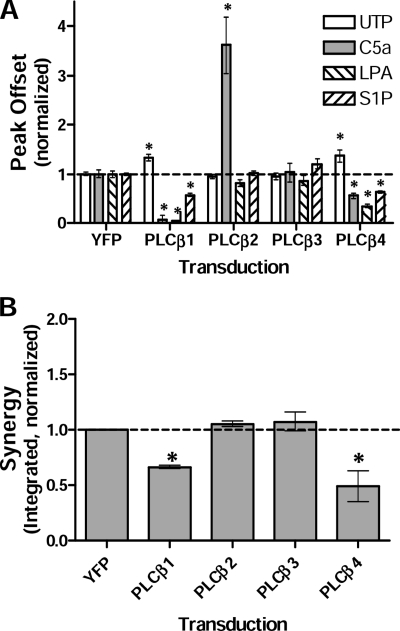

Overexpression of PLCβ Isoforms Selectively Enhances or Reduces Ca2+ Signaling

To further examine the selectivity of PLCβ isoforms in contributing to Ca2+ synergy, we overexpressed YFP-tagged PLCβ isoforms in NIH-3T3 cells. By flow cytometry, the PLCβ isoforms were expressed at comparable levels (supplemental Fig. S7, B and C). By Western blotting, PLCβ3 levels were 2.7 ± 0.2-fold above levels of endogenous PLCβ3 (data not shown). Ca2+ responses were compared with responses by cells transfected with YFP-tagged FLAG epitope (YFP-FLAG). Overexpression of PLCβ3 had no significant effect on any single-ligand responses, perhaps because endogenous levels of this PLCβ isoform are already high. Overexpression of PLCβ2, however, markedly enhanced the response to C5a, although it did not alter signaling to UTP, LPA, or S1P. The capacity of PLCβ2 to augment C5a signaling following overexpression in 3T3 cells, whereas overexpression of PLCβ3 did not, suggests that PLCβ2 may differ qualitatively from PLCβ3 in its activation by C5a. Overexpression of PLCβ1 or PLCβ4 augmented Gαq-coupled UTP responses (Fig. 6A), but it inhibited the Gαi-coupled responses by C5a, LPA, and S1P, perhaps reflecting differences in PLCβ isoform activation by Gαq versus Gβγ subunits (17, 18, 20). Overall, the results of PLCβ overexpression suggest that Ca2+ responses to C5a may be inhibited by PLCβ isoforms that are less sensitive to Gβγ (PLCβ1 and PLCβ4), but they are enhanced by isoforms that are activated by Gβγ (PLCβ2). Synergy in response to dual ligands also differed between either PLCβ1 or PLCβ4 relative to PLCβ2 or PLCβ3. Overexpression of PLCβ1 or PLCβ4 inhibited synergy following stimulation with C5a plus UTP (Fig. 6B), but this inhibition was lost with mutation of Gαq-binding domain of PLCβ4 (supplemental Fig. S7D). In contrast, overexpression of PLCβ2 or PLCβ3 did not alter synergy; the synergy ratio was maintained and was not further increased by overexpression of PLCβ2 or PLCβ3. As noted above, signaling by C5a alone rose substantially following overexpression of PLCβ2, and so did dual-ligand signaling by C5a plus UTP, but the synergy ratio was the same as in YFP-transfected cells, suggesting that PLCβ2 overexpression augments the magnitude of synergy responses in parallel with its augmentation of signaling by C5a alone. Thus, results from overexpression of PLCβ isoforms are consistent with the results from the knockdown experiments in supporting an inhibitory effect of PLCβ1 or PLCβ4 on Ca2+ response synergy, in contrast with dependence for synergy on PLCβ3. Although PLCβ2 is normally not found in NIH-3T3 cells, it appears capable of contributing to synergy, as it can in BMDMs (although its contribution to synergy in BMDMs is low).

FIGURE 6.

Overexpression of PLCβ isoforms in NIH-3T3 cells perturbs single- and dual-ligand responses. NIH-3T3 cells stably expressing YFP-PLCβ isoforms or YFP control protein were assayed for Ca2+ responses to individual ligands (A) and C5a + UTP dual ligand (B). A, single-ligand concentrations were 100 μm UTP, 10 nm C5a, 500 nm LPA, and 500 nm S1P. Responses were normalized to YFP control lines using the peak offset measures of the responses. B, synergy between C5a (10 nm) and UTP (100 μm) was measured using the integrated responses and normalized to responses of control cells in each assay (dotted line, representing an average synergy ratio of 2.7). Values shown are mean ± S.E. (error bars) from n = 3 assays. *, p < 0.05.

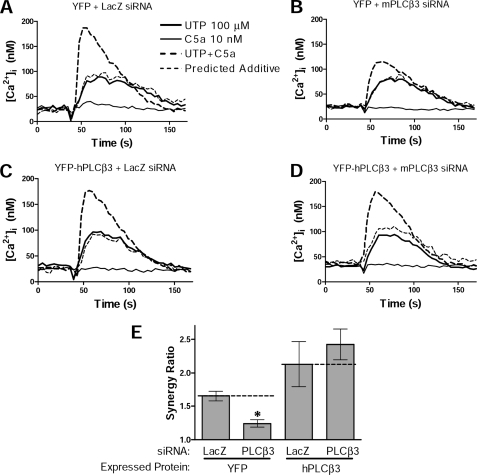

Reconstitution of PLCβ3 Expression Restores Ca2+ Synergy Lost with PLCβ3 RNAi

To further validate the requirement for PLCβ3 expression for Ca2+ synergy, we combined knockdown of endogenous murine PLCβ3 in NIH-3T3 cells by RNAi with restoration of PLCβ3 expression by transfection of human PLCβ3. The RNAi sequence targeted mPLCβ3 but not hPLCβ3. RNAi reduced mPLCβ3 mRNA by 74 ± 7%, as assessed by species-specific quantitative RT-PCR, and it reduced mPLCβ3 protein by 50–80% (supplemental Fig. S8), as assessed by Western blotting. In accord with this, RNAi reduced Ca2+ synergy by 60–70% (Fig. 7, A, B, and E). Expression of hPLCβ3 reversed the loss of synergy following knockdown of mPLCβ3 by RNAi (Fig. 7, C–E), supporting the conclusion that the loss of synergy following RNAi of PLCβ3 reflects knockdown of PLCβ3 expression. The restoration of synergy by transfected hPLCβ3 was not due to negation of the RNAi by hPLCβ3 (e.g. by binding siRNA) because mPLCβ3 remained suppressed (supplemental Fig. S8B). Indeed, attempted overexpression of transcripts for mPLCβ3 instead of hPLCβ3 failed to restore synergy (supplemental Fig. S9C), because knockdown of mPLCβ3 persisted (supplemental Fig. S8B). Synergy was also restored by mPLCβ2 although not as robustly as by hPLCβ3 (supplemental Fig. S9D). Thus, PLCβ2, like PLCβ3, has the capacity to mediate synergy in these cells.

FIGURE 7.

Expression of human PLCβ3 can compensate for knockdown of endogenous murine PLCβ3. NIH-3T3 cells were stably transfected with YFP (A and B) or YFP-hPLCβ3 (C and D) and subjected to RNAi using murine-specific anti-PLCβ3 (B and D) or LacZ control (A and C) siRNA. Ca2+ assays were performed to assess synergy responses with C5a + UTP stimulations. E, responses were quantified for synergy ratio using peak offset measurements (1 unit = predicted additive response of each cell). Shown are results from n = 3 assays of 2 independently derived cell lines/target. Synergy was reduced by 0.4 units with RNAi against mPLCβ3 (*, p < 0.05) unless the cells were reconstituted with hPLCβ3. Error bars, S.E.

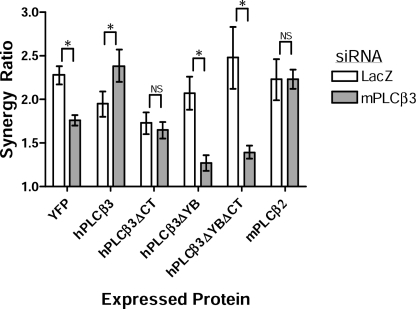

Both the Gβγ and Gαq Binding Sites of PLCβ3 Are Required for Synergistic Ca2+ Responses

PLCβ3 is responsive to both Gβγ and Gαq, and our studies suggest that synergy by Gαi and Gαq GPCRs may be mediated by the combined action of Gβγ and Gαq on a single PLCβ isoform. Several alternate mechanisms have been proposed for synergy between Gαi- and Gαq-linked GPCRs in different systems (5), however, and a direct synergistic activation mechanism does not preclude contributions from other mechanisms. To examine if the mechanism of Ca2+ synergy for dual C5aR and P2YR stimulation shares a requirement for activation of PLCβ3 by both Gβγ and Gαq, we evaluated the ability of PLCβ3 mutated in residues critical for activation by these respective G-proteins to mediate synergy. Residues in the Y-box of PLCβ3 homologous to those critical for the binding of Gβγ to PLCβ1 or residues in the C terminus homologous to those critical for the binding of Gαq to PLCβ1 were targeted with X → Ala mutations (28–31). These sites are depicted in Fig. 1 and described under “Experimental Procedures” as E262A,T263A,K264A in the Y-box and K965A,R969A,D1074A,R1089A in the C terminus. Mutation of the Y-box disrupted activation by Gβγ in vitro by ∼80%, but activation by Gαq remained intact (Table 1). Mutation of the C terminus diminished activation by Gαq by ∼65%, whereas activation by Gβγ was largely intact. Thus, the functional defects of these mutants were relatively selective.

TABLE 1.

In vitro G-protein activation of purified hPLCβ3

Activity was measured by hydrolysis of [3H]PIP2 and is expressed as -fold stimulation over basal activity, which was 103.38 ± 13.19 mol of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate/min/mol of PLC. Values shown are from a representative experiment of four or more with similar results.

| Activation | hPLCβ3 construct |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Intact | Y-box mutant | C-terminal mutant | |

| -fold | -fold | -fold | |

| Gβγ | 7.9 | 2 | 6.5 |

| Gαq | 8.5 | 9.4 | 4.4 |

We transfected NIH-3T3 cells with the different YFP-hPLCβ3 mutants or with a double mutant in which both sites were targeted. Expression of PLCβ3 mutated in the Y-box failed to reconstitute synergy lost by knockdown of endogenous mPLCβ3 (Fig. 8), indicating a requirement for Gβγ activation of PLCβ for synergy. In contrast, reconstitution with WT hPLCβ3 actually enhanced synergy in these experiments, suggesting that greater activity exists for this construct, perhaps due to YFP fusion or human versus mouse sequence effects. Such an enhancement was suggested, but not statistically significant, in Fig. 7E. Expression of PLCβ3 mutated in the C-terminal domain only partially restored synergy (Fig. 8) because synergy remained at base-line levels and did not show the enhancement seen with WT PLCβ3. The C-terminal mutant appeared ∼50% as effective as intact hPLCβ3 (supplemental Fig. S9C). This partial effect is consistent with the incomplete effect of the mutation in disrupting Gαq activation (Table 1). Disruption of both Y-box and C-terminal sites disrupted synergy comparable with the Y-box alone. Thus, both Y-box and C-terminal sites in PLCβ3 contribute to synergistic Ca2+ responses, supporting the premise that synergy in intact cells depends on activation of PLCβ3 by both Gβγ and Gαq. These data support a mechanism of Ca2+ synergy resulting from the synergistic activation of PLCβ3 by the combined activity of Gβγ and Gαq released by Gαi- and Gαq-linked GPCRs.

FIGURE 8.

Binding of both Gβγ and Gαq contributes to the synergistic activation of PLCβ. NIH-3T3 cells were stably transfected with YFP or YFP-tagged PLCβ constructs including intact hPLCβ3, C-terminal mutant (hPLCβ3ΔCT), Y-box mutant (hPLCβ3ΔYB), and C-terminal mutant (hPLCβ3ΔYBΔCT). Cells were then subjected to RNAi using murine-specific anti-PLCβ3 or LacZ control siRNA. Synergy ratios were calculated for each cell line and treatment. Shown are results from n = 4–14 assays of 2–3 independently derived cell lines/target. Although intact hPLCβ3 slightly elevated synergy with RNAi of endogenous mPLCβ3, the C-terminal mutant had a reduced capacity, and the Y-box mutant had no activity. *, p < 0.05. NS, not significant; Error bars, S.E.

DISCUSSION

In the current studies, we demonstrate that the synergistic increases in intracellular Ca2+ following simultaneous stimulation of Gαi- and Gαq-linked GPCRs in cells can be mediated by PLCβ3 or PLCβ2. PLCβ1 and PLCβ4 are instead inhibitory. Ca2+ synergy depends on binding sites in PLCβ3 for both Gβγ in the Y-box domain and Gαq in the C terminus. Based on these findings, we present a model of Ca2+ synergy resulting from the direct, synergistic activation of PLCβ3 by combined stimulation with Gβγ and Gαq.

PLCβ3 is the predominant isoform used for single-ligand and synergistic Ca2+ responses in macrophages (11). Despite the fact that macrophages have abundant transcripts for PLCβ2, PLCβ2 does not effectively substitute for PLCβ3 when the latter is absent (11). We now show that PLCβ2 is nonetheless required for the low level of residual synergy detected in PLCβ3-deficient macrophages because macrophages deficient in both PLCβ3 and PLCβ2 demonstrated no synergy in their Ca2+ response to C5a and UDP. Also, we found that PLCβ2 could substitute for PLCβ3 in NIH-3T3 cells (where it is not normally expressed at detectable levels); either endogenous PLCβ3 or exogenous PLCβ2 produced a robust synergistic Ca2+ response in these cells. In contrast, PLCβ4 did not mediate synergy in either system. Instead, either PLCβ4 or PLCβ1 isoforms tended to inhibit synergy when they were overexpressed.

These results may be viewed in light of known features of the PLCβ isoforms in their binding to G-protein subunits (reviewed in Ref. 27). Gβγ has been shown to interact both with residues in the N-terminal pleckstrin homology domain and in the Y-box of the PLCβ catalytic domain (30, 31, 35). Only PLCβ3 and PLCβ2 show high affinity binding and activation by Gβγ, and varied combinations of β and γ subunits can differ in their effectiveness (36–40). In our studies, PLCβ3 and PLCβ2 were the only isoforms able to reconstitute synergy in cells, and mutation of the Y-box Gβγ binding site alone led to a substantial loss of the synergistic activation of PLCβ3.

Like Gβγ, Gαq has at least two potential binding sites on PLCβ, one in the C terminus and another in the C2 domain (28, 41–44). Although Gαq can activate all isoforms of PLCβ, PLCβ2 is the least sensitive (45, 46). Mutation of the C terminus of PLCβ1 can disrupt its activation by Gαq but not Gβγ (28, 29). In our studies, homologous mutations of PLCβ3 also disrupted Gαq activation, but not fully; activation was reduced by ∼65%. This reduction in Gαq activation of the hPLCβ3 mutant in vitro correlated with a ∼50% reduced magnitude of synergy observed in cells. The residual Gαq activation in the PLCβ3 C-terminal mutant suggests either that alternate residues in this area contribute to Gαq activation or that there is a role for the other known Gαq-binding site in the C2 domain. Although our C-terminal mutation of PLCβ3 did not fully ablate Gαq activation, our data indicate a contribution of Gαq binding to the C terminus of PLCβ3 in the synergy mechanism. A role for Gαq in the synergy mechanism was further suggested by the inability of truncation mutants of PLCβ2, which eliminated the C-terminal Gαq binding region (truncation at amino acid 840), to mediate synergy in 3T3 cells (data not shown). Overall, our results demonstrate a direct role for Gβγ in PLCβ3-mediated synergy via binding in the Y-box catalytic domain, and they support a role for Gαq at the targeted C-terminal binding site.

The capacity to test the activation of purified PLCβ3 in vitro by individual or combined G-protein subunits has opened the path to exploring mechanisms by which Gβγ and Gαq may synergize in activating this PLCβ isoform. Recent studies by Philip and Ross (47). demonstrate synergistic activation of PLCβ3 by simultaneous Gβγ and Gαq stimulation in vitro, in accord with our studies in cells. These studies further show that the combined action of Gβγ and Gαq on PLCβ3 enhances conversion of the enzyme to the active state when both ligands are bound rather than merely enhancing ligand affinity.

The selective use of PLCβ isoforms in GPCR Ca2+ signaling and synergy may involve mechanisms in addition to their binding of G-proteins, such as the selective use of different scaffolding or other interacting proteins (48, 49). PDZ domain-containing proteins may be of central importance in the recruitment of PLCβs and other regulators of GPCR-mediated Ca2+ signaling (48–50). Although all isoforms of PLCβ have a PDZ domain-binding motif (X(S/T)X(V/L)) at the C terminus, their peptide sequences vary and may thus make differential use of PDZ domains. In support of this, PLCβ3 preferentially binds to specific PDZ domain-containing scaffolding proteins, including NHERF1, E3KARP, and SHANK2 (48, 49, 51). The selective use of PLCβ3 in GPCR signaling by macrophages could relate to the selective expression of such scaffolding proteins in these cells,6 whereas synergy in NIH-3T3 cells may involve scaffolding proteins that are recognized more equivalently by both PLCβ3 and PLCβ2. Further examination of PLCβ3 and PLCβ2 structural requirements for synergy are necessary to evaluate these contributions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues in the Alliance for Cellular Signaling for helpful insight and critiques of the project. We also thank Lily I. Jiang (University of Texas Southwestern) for plasmids and Rose Finley (San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center) for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants GM 62114 and GM 30355 (to E. M. R.). This work was also supported by Welch Foundation Grant I-0982 (to E. M. R.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table S1 and Figs. S1–S9.

L. Santat and I. Fraser, unpublished observation.

- PLC

- phospholipase C

- hPLC

- human PLC

- mPLC

- mouse PLC

- BMDM

- bone marrow-derived macrophage

- C5a

- complement 5a

- C5aR

- C5a receptor

- GPCR

- G-protein-coupled receptor

- LPA

- lysophosphatidic acid

- PTx

- pertussis toxin

- S1P

- sphingosine 1-phosphate

- YFP

- yellow fluorescent protein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Berridge M. J., Bootman M. D., Roderick H. L. (2003) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 517–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berridge M. J. (2006) Cell Calcium 40, 405–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Delmas P., Crest M., Brown D. A. (2004) Trends Neurosci. 27, 41–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Okajima F., Sato K., Sho K., Kondo Y. (1989) FEBS Lett. 248, 145–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Werry T. D., Wilkinson G. F., Willars G. B. (2003) Biochem. J. 374, 281–296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dickenson J. M., Hill S. J. (1993) Biochem. Soc Trans. 21, 1124–1129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jiménez A. I., Castro E., Mirabet M., Franco R., Delicado E. G., Miras-Portugal M. T. (1999) Glia 26, 119–128 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Toms N. J., Roberts P. J. (1999) Neuropharmacology 38, 1511–1517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shah B. H., Siddiqui A., Qureshi K. A., Khan M., Rafi S., Ujan V. A., Yaqub Y., Rasheed H., Saeed S. A. (1999) Exp. Mol. Med. 31, 42–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carroll R. C., Morielli A. D., Peralta E. G. (1995) Curr. Biol. 5, 536–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Roach T. I., Rebres R. A., Fraser I. D., Decamp D. L., Lin K. M., Sternweis P. C., Simon M. I., Seaman W. E. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 17351–17361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dickenson J. M., Hill S. J. (1994) Int. J. Biochem. 26, 959–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cilluffo M. C., Esqueda E., Farahbakhsh N. A. (2000) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 279, C734–C743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Okajima F., Tomura H., Kondo Y. (1993) Biochem. J. 290, 241–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dickenson J. M., Hill S. J. (1996) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 302, 141–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Werry T. D., Wilkinson G. F., Willars G. B. (2003) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 307, 661–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Smrcka A. V., Sternweis P. C. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 9667–9674 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Park D., Jhon D. Y., Lee C. W., Lee K. H., Rhee S. G. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 4573–4576 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee C. W., Lee K. H., Lee S. B., Park D., Rhee S. G. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 25335–25338 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Camps M., Carozzi A., Schnabel P., Scheer A., Parker P. J., Gierschik P. (1992) Nature 360, 684–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Quitterer U., Lohse M. J. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 10626–10631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xie W., Samoriski G. M., McLaughlin J. P., Romoser V. A., Smrcka A., Hinkle P. M., Bidlack J. M., Gross R. A., Jiang H., Wu D. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 10385–10390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jiang H., Kuang Y., Wu Y., Xie W., Simon M. I., Wu D. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 7971–7975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Coward P., Wada H. G., Falk M. S., Chan S. D., Meng F., Akil H., Conklin B. R. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 352–357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wu J., Cherwinski H., Spies T., Phillips J. H., Lanier L. L. (2000) J. Exp. Med. 192, 1059–1068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zavzavadjian J. R., Couture S., Park W. S., Whalen J., Lyon S., Lee G., Fung E., Mi Q., Liu J., Wall E., Santat L., Dhandapani K., Kivork C., Driver A., Zhu X., Chang M. S., Randhawa B., Gehrig E., Bryan H., Verghese M., Maer A., Saunders B., Ning Y., Subramaniam S., Meyer T., Simon M. I., O'Rourke N., Chandy G., Fraser I. D. (2007) Mol. Cell Proteomics 6, 413–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rhee S. G. (2001) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70, 281–312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ilkaeva O., Kinch L. N., Paulssen R. H., Ross E. M. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 4294–4300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kim C. G., Park D., Rhee S. G. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 21187–21192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bonacci T. M., Ghosh M., Malik S., Smrcka A. V. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 10174–10181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sankaran B., Osterhout J., Wu D., Smrcka A. V. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 7148–7154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Swift S., Lorens J., Achacoso P., Nolan G. P. (2001) Curr. Protoc. Immunol., Chapter 10, Unit 10.17C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Morita S., Kojima T., Kitamura T. (2000) Gene Ther. 7, 1063–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Biddlecome G. H., Berstein G., Ross E. M. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 7999–8007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang T., Dowal L., El-Maghrabi M. R., Rebecchi M., Scarlata S. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 7466–7469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Watson A. J., Katz A., Simon M. I. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 22150–22156 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wu D., Katz A., Simon M. I. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 5297–5301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rebecchi M. J., Pentyala S. N. (2000) Physiol. Rev. 80, 1291–1335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Boyer J. L., Graber S. G., Waldo G. L., Harden T. K., Garrison J. C. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 2814–2819 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ueda N., Iñiguez-Lluhi J. A., Lee E., Smrcka A. V., Robishaw J. D., Gilman A. G. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 4388–4395 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Park D., Jhon D. Y., Lee C. W., Ryu S. H., Rhee S. G. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 3710–3714 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wu D., Jiang H., Katz A., Simon M. I. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 3704–3709 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wang T., Pentyala S., Elliott J. T., Dowal L., Gupta E., Rebecchi M. J., Scarlata S. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 7843–7846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lee S. B., Shin S. H., Hepler J. R., Gilman A. G., Rhee S. G. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 25952–25957 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sternweis P. C., Smrcka A. V. (1993) Ciba Found. Symp. 176, 96–106; discussion 106–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jhon D. Y., Lee H. H., Park D., Lee C. W., Lee K. H., Yoo O. J., Rhee S. G. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 6654–6661 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Philip F., Kadamur G., Silos R. G., Woodson J., Ross E. M. (2010) Curr. Biol. 20, 1327–1335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ranganathan R., Ross E. M. (1997) Curr. Biol. 7, R770–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Suh P. G., Hwang J. I., Ryu S. H., Donowitz M., Kim J. H. (2001) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 288, 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fam S. R., Paquet M., Castleberry A. M., Oller H., Lee C. J., Traynelis S. F., Smith Y., Yun C. C., Hall R. A. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 8042–8047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hwang J. I., Kim H. S., Lee J. R., Kim E., Ryu S. H., Suh P. G. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 12467–12473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Grynkiewicz G., Poenie M., Tsien R. Y. (1985) J. Biol. Chem. 260, 3440–3450 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.