Abstract

This study examines healthcare providers’ perceptions regarding experiences and factors that contribute to adherent and non-adherent behaviors to HIV treatment among women living with HIV infection in Puerto Rico and describes strategies implemented to improve adherence. Providers’ accounts revealed that women with HIV infection are living “beyond their strengths” attempting to reconcile the burden of the illness and keep adherent. Factors putting women beyond their strengths and influencing non-adherence behavior were: gender-related demands, fear of disclosure, and treatment complexity. Strategies to improve adherence included: ongoing assessment, education, collaborative work, support groups, networking, disguising pills, readiness, and seeking medications outside their towns. Provider-patient interactions are critical for women’s success and must assess all these factors in developing and providing health services.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Adherence, Providers, Women, and Puerto Rico

Introduction and Background

The Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), the virus that causes Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) continues to expand globally and, currently, the Caribbean countries, which comprise the Greater Antilles group, have the second highest prevalence of the epidemic in the world after Sub-Saharan Africa (Caribbean Epidemiology Centre, 2007). Currently, Haiti and the Dominican Republic form the epicenter of the HIV epidemic in the Americas and account for nearly three-quarters of the people living with HIV in the Caribbean (Caribbean Epidemiology Centre). The Island of Puerto Rico, which is also located in the Caribbean, to the east of the Dominican Republic, has been severely affected by HIV infection and AIDS. AIDS, representing the late clinical stage of HIV infection, which progressively damages the person’s immune system and eventually causes death, has affected 33,074 people and 62% have died of AIDS complications (Puerto Rico AIDS Surveillance Program, 2009). The 15% of the reported AIDS cases have occurred among those 15–24 years old, 13% among those 45–54 years old, and 7% among those 55 and older. After the implementation of HIV reporting in Puerto Rico in 2003, the number of new infection reported is 7,347, suggesting that HIV risk behaviors continues among our population (Puerto Rico HIV Surveillance Program, 2009).

Women represent one of the largest percentages of newly infected HIV group in the world (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2007). Of the estimated 39.5 million people living with HIV/AIDS, nearly half are women and girls (Henry Kaiser Family Foundation, 2007; Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS). In Latin America, it is estimated that of the 1.4 million people living with HIV, 30% are women, and 50% of the 420,000 people living with HIV in the Caribbean are also women (Pan American Health Organization, 2005). In Puerto Rico, women between the ages of 20–39 years old are the fastest growing segment of the adult population acquiring HIV and they represent 24% of AIDS cases (Puerto Rico AIDS Surveillance Program, 2009). The most common means of transmission are unprotected heterosexual activity (61%) and sharing of needles for drug use (Puerto Rico AIDS Surveillance Program). These numbers are important because they show the epidemiological face of the disease with women being one of the most vulnerable groups.

HIV infection is a very complex illness process that affects all facets of women’s lives including their physical, social, spiritual and psychological dimensions. These women must make a series of complex decisions concerning childbearing, treatment modalities, diagnosis, disclosure, family issues, and women’s role as family caregivers. One factor identified as impacting the course of HIV infection in women is their acceptance and use of prescribed drug therapies. Poorer antiretroviral adherence and more antiretroviral-related events have been reported among women (Ciambrone, Loewenthal, Bazerman, Zorilla, Urbina, & Mitty, 2006; Wood, Tobias, & McCree, 2004).

Adherence to antiretroviral regimens

Since the introduction of antiretroviral treatment (ART) the HIV/AIDS related morbidity and mortality has declined among affected people. Research has showed that adherence to ART is necessary in order to achieve treatment effectiveness, virological suppression, and to slow the development and spread of drug-resistance viral strains among people with HIV/AIDS (Reynolds, 2004; Vervoort, Borleffs, Hoepelman, & Grypdonck, 2007). Adherence to treatment and clinical follow-up play a particularly crucial role in allowing women to achieve virologic, immunologic and clinical outcomes. While ART has been very effective suppressing viral replication and slowing disease progression, achieving a balance between adherence, the challenges related to the illness, and daily activities have been difficult for people living with HIV infection. Adherence to HIV medications is a dynamic process managed by patients and their healthcare providers, where health care decisions are negotiated around client’s beliefs, abilities, behaviors, lifestyles, and priorities (Frank, Waldron, Jerrett, Rowe, & Fisk, 1998). A commitment to lifelong ART requires a commitment of both the patient and the health care team. Some studies indicate that women in particular appear to have more difficulty with adherence to ART due to many numerous interacting phenomena including poverty, unemployment, social services needs for their family, family responsibilities, stigma, lack of housing, lack of social support, alcohol/substance abuse, and mental health concerns (Chesney, 2003; Mills et al., 2006; Remien, Hirky, Johnson, Weinhardt, Whitter, & Le, 2003; Stone et al., 2001; Wood et al., 2004).

Given the importance of adherence, a consensus has been developing among researchers about the factors that influence adherence. These factors include treatment characteristics (Abel & Painter, 2003; Murphy, Roberts, Hoffman, Molina, & Lu, 2003); patient characteristics (Adam, Maticka-Tyndale, & Cohen, 2003; Hill, Kendall, & Fernandez, 2003; Wilson, Hutchinson, & Holzemer, 2002); and provider-patient interactions (Ammassari et al., 2002; Deschamps et al., 2004). Although all of these factors are relevant for medication adherence in people with HIV infection, provider-patient interactions seem to be a key determinant of a patient’s success in adhering to regimens (Bakken et al., 2000; Heyer & Ogunbanjo, 2006; Wagner, Justice, Chesney, Sinclain, Weissman, & Rodriguez-Barradas, 2001). These studies have documented the importance of quality and effective communication in the provider-patient relationship, which influences the patient’s attitude and understanding toward his/her illness and therapeutic regimen.

Patients who receive comprehensive information about an ART regimen tailored to their lifestyles and beliefs, who have access to culturally sensitive services, social support, and who have an open and non-judgmental dialogue with their health care providers (Fogarty Roter, Larson, burke, Gillespie, & Levy, 2002; Roberts, 2002) are more likely than others to be adherent to both ART and clinical follow-up. While the above mentioned studies suggest that provider-patient interactions seem to be a key determinant of a patient’s success in adhering to regimens, to date, little is know about providers’ perspectives working with women with HIV infection in Puerto Rico. In an effort to contribute to the literature on women with HIV infection, this pilot study focused on providers’ perceptions regarding factors that contribute to adherence and non-adherence behavior of women infected with HIV/AIDS in Puerto Rico.

Methods

Protection of human subjects

This study received the approval from the Committee on the Protection of Human Subjects at the University of Puerto Rico and the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), California. The research team was composed of the principal investigator, a Co-investigator from UCSF, and two doctoral level psychology students with experience conducting interviews and previous participations in qualitative research. The research team also completed training on the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and protection of human subject participants in research. The interviewer provided verbal and written information about the purpose of the study, the sponsoring institution, and obtained a written informed consent from participants. Participants received a copy of the signed informed consent form. Interviews were scheduled at participant’s convenience and conducted in a private room at their place of work. No personal or identifying information was retained within the transcripts and all tapes were destroyed after transcription. No financial incentives were provided.

Qualitative research approach

Due to the exploratory nature of this research, our study adopted a qualitative approach to describe the providers’ perceptions, experiences and factors that contribute to adherent and non-adherent behaviors to ART among women living with HIV infection in Puerto Rico. In-depth interviews were employed as the method of data collection to better understand providers’ perspective in great detail and elicit their experiences with women living with HIV/AIDS (Greenhalgh & Taylor, 1997; Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Strauss’ and Corbin’s guidelines were used to inductively analyze interview data, identify existing themes and patterns that emerged from data and to generate analytical categories. Detailed handwritten notes were taken during the course of each interview.

Participants

A State Public Health Department ambulatory clinic involved in HIV care of people with HIV infection in Puerto Rico was contacted. A collaborative agreement was developed between the research team and the organization. The clinic director made announcement about this study. Ten providers (two nurses, three physicians, three case managers, one health educator, and one psychologist) were purposely selected to represent a range of professionals working in HIV care, and who offer treatment to low-income persons within a multidisciplinary focus. This type of sampling was useful because the selected participants were those whose qualities or experiences will illustrate or highlight a phenomena (Polit & Beck, 2006). When approached, participants were aware of this study and were invited to participate if they met the following inclusion criteria: (a) were healthcare providers including physicians, nurses, case managers, health educators, and psychologists, (b) had clinical experience working with Puerto Rico women who are HIV positive, (c) have provided care related to HIV medication adherence for at least three years, and (d) willing to participate in this study. Descriptive characteristics of the ten health care providers who participated in the interviews can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic of Participating Healthcare Providers

| Characteristics | n = 10 |

|---|---|

| Gender (female/male) | (6/4) |

| Age distribution (mean and range) | 42 (23–59) |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic) | 10 |

| Specialty | |

| Nurse | 2 |

| Physician | 3 |

| Case manager | 3 |

| Health educator | 1 |

| Psychologist | 1 |

| Years treating women with HIV/AIDS (mean) | 5 |

Procedures and analysis

Participants were interviewed face-to face and interview lasted around one-and-a-half hour. Prior the interview, demographic data was collected using an existing Minimum Data Set (MDS) questionnaire created by UCSF containing general demographic information such as participants’ age, gender, years of formal education, type of provider that they are, and years treating patients with HIV/AIDS.

Each provider was interviewed once in Spanish, in a private place in the clinical setting where the participant worked. The interview guide consisted of seven broad questions. This interview guide served to maintain a minimum level of uniformity in the topic that was explored during the interviews. This guide included the following questions:

What were their perceptions of their experiences treating women with HIV/AIDS?

How do they feel about women’s capability of taking medication as it has been prescribed?

What resources and strategies are used by these women to make decisions about antiretroviral therapy?

What factors as a healthcare provider perceive as barriers for women’s adherence to treatment?

What factors do they perceive as facilitators?

What are some of the criteria used to assess women for initiation and/or continuation of treatment

What are some of the strategies implemented in the clinic to improve adherence with antiretroviral therapy regimen?

Probes were used in each question to clarify providers’ responses and to elicit more complete responses to the questions. The Interview Guide is included at the end of this paper. The interviewer recorded the interview in audiotape and also took detailed handwritten notes. The notes documented the type of participant, environmental surroundings, key aspects of the interview, emerging themes, non-verbal cues as well as, start and end times. These additional notes served as key part of the analysis. Purposeful sampling of providers having experience with women with HIV/AIDS allowed us to reach data repetitiveness and informational redundancy. Data no longer provided any new information to develop categories (Byrne, 2001; Creswell, 2005; Strauss & Corbin, 1998). In qualitative studies, redundancy is generally achieved with a small number of participants (Polit & Beck, 2006). In this study, informational redundancy occurred with the seventh interview; however, we conducted three additional interviews to assure saturation. It was found again that providers’ experiences were captured by the existing themes or categories.

The two doctoral students transcribed the interviews verbatim. The principal investigator checked the transcripts against the taped version of interviews to ensure accurate and authentic reproductions of participants’ accounts and conducted content analysis manually. The following coding scheme illustrated below was used to code the interview data. The transcripts were first read line-by-line and paragraph-by-paragraph. Important passages of the interview were noted in the margins. A list of categories was then generated for each question, grouping each specific response by the major topics referred by the participant. The initial categories were then refined until considered adequate to reliably represent that set of responses (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). All the participants’ responses were then coded to these finalized categories. These categories were gradually modified or replaced during the subsequent stages of analysis. The emerging categories were compared with each other to ensure that they were mutually exclusive and covered the behavioral variations (Hutchinson, 1986). When concepts emerged during data analysis, the literature and pertinent documents were used as an ongoing process for clarification and expansion of the emerging categories. Memos were written to document the researcher’s ideas and analytical process about the data and the coded categories, to keep record, and to organize the results of the analysis (Strauss & Corbin). Memos were also sorted and ordered to organize data and ideas.

Procedures for ensuring trustworthiness

The credibility, “how vivid and faithful the description of the phenomenon is” (Beck, 1993, p. 264), was assured by transcribing each interview verbatim and verified by the researcher to assure accuracy of the typed transcripts against the original recording. At the end of each interview, providers were asked to add anything else they wanted to tell about the experience taking care of women with HIV. Maintaining detailed handwritten notes were used in data analysis and were helpful to understand the participants’ context. After the researcher’s interpretation of the data, peer checking was used to ensure that the researcher’s findings accurately represent participants’ realities. Three interviews were translated into English by one of the doctoral students and reanalyzed by the second researcher of this study who has expertise in qualitative methods and HIV/AIDS research and by another researcher not familiar with the study, but who had experience in conducting research with the HIV population. This strategy helps to assure some auditability in this study (Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Sandelowski, 1986). The theoretical validity of this study was addressed by using the constant comparison method proposed by Strauss and Corbin (1998) in which emerging relationships between categories where compared to each other to assure they were mutually exclusive. Fittingness, refers to the generalizability of qualitative study findings, although non- quantitative sense. Sandelowski (1997) suggests that in qualitative research, emphasis is placed on idiographic or naturalistic generalizations or conclusions that are drawn from and about cases. Describing provider’s perspective of their experiences and processes in treating women with HIV/AIDS and the phenomenon of adherence may not be generalizable to all population. However, these descriptions provide some direction for providers, to generate recommendations that would guide the development of tailored approaches and interventions on ART among women living with HIV/AIDS.

Findings

We organized providers’ verbalizations of their perceptions based on experiences interacting and communicating with women with HIV/AIDS regarding factors that contribute to adherence and non-adherence into a dominant theme called “beyond their strengths” and three related themes. The central theme “beyond their strengths” was repeatedly stated by several health care providers (n=6) and was expressed in terms of a complex process of functioning as women find out the HIV diagnosis and occurring on a day-to-day basis as women attempted to reconcile the burden of the illness and keep adherent to ART. Factors that put women “beyond their strengths” and influence non-adherence behavior were clustered in three significant themes: (a) gender-related demands, (b) fear of disclosure, and (c) dealing with treatment complexity. In Table 2 we describe each of these categories. Along with these themes, strategies and providers’ characteristics used to improve adherence behavior were explored and addressed.

Table 2.

Description of Central Category and Themes of Analysis

| Central Category and Themes | Description |

|---|---|

| Beyond their strengths | In this central theme we include the providers’ conceptualizations of beyond their strengths as related to women living with HIV/AIDS |

| Gender-related demands | In this theme we included verbalizations addressing participants’ perceptions on how gender plays a significant role in women’s adherence and non-adherent behavior |

| Fear of disclosure of HIV/AIDS status | In this theme we include verbalizations where providers’ describe their experience with women who manifest fears of being stigmatized |

| Dealing with treatment complexities | In this theme we include verbalizations where described how ART requirement interferes with women’s adherence |

Gender-related Demands

In this category we included verbalizations addressing providers’ perceptions on how gender plays a significant role in women’s adherence and non-adherent behavior. When providers’ were asked about their experiences treating women with HIV/AIDS infection, all felt that being a woman influenced a person’s ability to deal with the illness, initiate treatment and be adherent to prescribed medication regimens. Compared to Puerto Rico men, providers reported that HIV/AIDS illness affects women more negatively because as part of the societal cultural norms and structure, they are required to take responsibility of care for her home, partner, children, and family members, as well as others, first. Two different providers, a male health educator and a female physician described respectively their experiences treating women and pointed out this gender imbalance:

In our culture, men can go out and [they] don’t have to give much explanation about where they are going and that makes the process of going out and getting their medication easier for them… But there are women who have a very difficult time leaving the house and going out without having to give an explanation.

I see a woman [at the clinic] who is in school; she is a single mother with two children… She also works and helps her children with their homework…and does things around the house. Sometimes she is unable to remember-to take the medications. It is very difficult having an HIV diagnosis because of women’s multiple roles in society. These women are single mothers, who also have many children to take care of, as well as other family members and their partners.

Some providers (n=3) suggested that women who adhere well to their medications do so because they feel responsible for others. Family was mentioned as the principal motivator for women to stay adherent to treatment. They informed that a substantial proportion of women are diagnosed when they get pregnant but one of the challenges providers confront with these women is that are reluctant to take medication because of the possible effects on the pregnancy. Providers, however, also use the pregnancy as a motivator to influence women’s decisions regarding antiretroviral therapy and to promote adherence. Ciambore et al. (2006) reported that support from family members and women’s concerns about the health of the unborn child were two facilitators of adherence. One female physician gave the following example:

They have to take care of themselves in order to care of their baby and have the knowledge that the medication lowers the risk of infection for the baby.

According to all interviewed providers, in Puerto Rico, many women who are HIV positive are young, marked with material issues, financial problems, lack of transportation, low levels of education, and do not know how to access HIV/AIDS services to seek health care. These issues were identified by providers as barriers for women to engage in on-going care, and to initiate and maintain adherence to ART regimens. When asked about criteria implemented to work effectively with women for initiation and continuation of ART in the context of these issues, descriptions of three mutually related strategies were provided: information gathering assessment, education, and collaborative work. Information gathering assessment is done in all settings, whether women arrive by referral or by word of mouth. For providers this is an important process and communication must be “clear” because this is the time when they identify:

what women know about the diagnosis, who knows it and is supporting her, how their family lives, how her lab work is, and what are her options for medications.

One case manager gave the following example:

…for us, it is very important to know who the woman lives with, whether or not she is a mother, whether she works and has children…for this particular person [last] we need to select a simpler regimen.

Two of the most frequently challenges confronted by most providers (n=6) is that many of the women they treat are not prepared for the HIV diagnosis and initiation of the antiretroviral treatment. Two different providers, a nurse and a physician described the strategies used:

We wait, because when the person is prepared, this facilitates things because we know that she will be more adherent…

when the CD4 count [the receptor for HIV, enabling the virus to gain entry] are low and viral load high, then we are more direct and tell them that they need to begin treatment.

Another means of getting information is by making arrangements for the women to be seen by providers from different disciplines. Providers repeatedly mentioned the words “treat women as a person”, “be sensible”, and “team work” meaning: “I help you and you help me” and “dual commitment” as key components that facilitate a successful initiation and continuation of treatment.

Education and collaborative work were described as essential strategies when giving individualized information to women in order to assist them in making decisions about medications and this “working together” helps women maintain a sense of control over some aspects of their lives. Providers were aware that women see them as an important source of information. For some providers three important things are key when working with women to facilitate adherence: “establishing rapport” being “always accessible” and providing a “good education.” From a psychologist’s point of view, the education and collaborative work between providers from different disciplines must occur in every encounter with the women. One case manager summed up this perspective in the following way:

If they understand their condition and are well informed, they will be able to make decisions…we educate them continuously and in our clinic everyone [staff] is involved and speaks the same language.

All providers interviewed expressed that, to be effective in working with women with HIV/AIDS, they must be fully open, meaning being sincere and honest, and have a trusting relationship with them. They feel it is appropriate to “show love”, “be a friend”, and “being emotional by expressing their own feelings openly and without any reserve” to women’s when a difficult situation arises. Being emotional is best described vividly by one female physician when she remembered the day when she was asked to help one woman disclose her diagnosis to her partner:

It was an incredible emotion because he showed her so much love…I looked at them and tears were streaming down my face and she said “Dr.?”… And I told her, “I have the right to be emotional with you.”

A male case manager described how he expresses his love to the patients:

I have patients that see me as a father-figure… if I have to lie down on bed with them while they are receiving treatment, I do it… I hug and kiss them.

The providers’ interviewed felt that it was appropriate to “go a bit further” with their HIV-positive patients because they have found that it helps the patients trust them more and share information more openly with them.

Fear of disclosure of HIV/AIDS status

Providers understood that women are aware of the stigmatized meaning attached to HIV/AIDS and Puerto Rico society’s negative stereotypes of persons living with HIV/AIDS. Many providers reported that women were not only concerned about their many issues affecting their lives, their responsibilities to family, partners, and relatives, but also avoid the effect of social stigma attached to their illness and potential discrimination resulting from the disclosure of their status. HIV/AIDS has fostered several responses in society, which include social stigma expressed by prejudice, fear, discrimination, and rejection of people and their families (Goffman, 1963; Ruiz-Torres, Cintron-Bou, & Varas-Diaz, 2007). Additionally, stigmatization has been recognized as a major influence in treatment and care of people living with HIV/AIDS (Madru, 2003; Relf, Mallinson, Pawlowski, Dolan, & Dekker, 2005; Surlis & Hyde, 2001; Varas-Diaz, Toro-Alfonso, & Serrano-Garcia, 2005). Although in the Puerto Rico culture, family historically is described as loving, caring, and nurturing, Roldan (2007) pointed out that in the presence of HIV/AIDS, people in Puerto Rico are responding in a way that runs contrary to this culture’s strong value. In response to the social stigma, several providers made reference to examples to evidence women’s fears of stigma, for example,

women who are reluctant to make a decision to initiate medication, women who come from one town to get their medications in another, women who are taking medications and no one knows that they have the condition, and women who have children and who do not want them finding out so that they [children] don’t suffer

The decision to conceal the diagnosis as a self-protective strategy to avoid social stigma and family rejection was perceived as a challenge for women’s access to ongoing services. These were the answers given by two providers concerning the disclosure issue:

Not revealing the HIV/AIDS status is detrimental for women. I had this divorced women with three children, and no one knew about her condition… She had fear and used to be in and out of the clinic. We lost her and we do not know about her whereabouts.

The disclosure of the diagnosis is very important… The family is very important because they help her to get here, the same if it is their romantic partner, because they don’t have to hide in order to receive services.

Providers shared the strategies implemented in their clinic to help maintain adherence to antiretroviral medications and protect women if no one knows about their HIV status. Among the strategies reported were:

Support groups to help women feel secure, that they are not alone in this process, and to learn specific strategies to care for herself.

Create a network within the family unit, where they can help each other.

At home and work they recommend putting their pills in different bottles so they cannot be identifiable to others.

Seeking alternatives places to obtain for outside their town.

Using these strategies, providers have found that as soon as women feel that they have some control on the issue of disclosure, everything in their lives change and this helps them become more responsible for their health.

Dealing with Treatment Complexities

All providers recognized that the requirement to adhere to a complex, difficult, time-consuming, regimen that interferes with daily activities and gender demands it is always difficult to women living with HIV infection. In dealing with treatment complexities, women are required to take multiple daily doses, make significant adjustment in their daily life, have extensive food restrictions, and additionally, face the toxicity and side effects of ART (Chesney, 2003). Adherence to HIV treatment regimen is a core element for viral suppression. If the virus is allowed to mutate into drug resistant strains, the treatment regimen can become ineffective, which reduces treatment options both for the non-adherent women and for any partners they may infect with these strains (Pilcher, Eron, Galvin, Gay, & Cohen, 2004). Because of this reality confronted by women’s, providers described the need for personalized antiretroviral regimens and the need for a clear negotiation with women. For example, it was the general consensus of providers that treatment should be delayed and negotiated until a woman is ready to adhere. Among the interventions considered by providers when working with women, the first is to establish “readiness”. Information gathering assessment made in first meetings, help providers establish the degree of readiness and willingness that women have to integrate a new behavior into their daily living in order to optimize adherence. The second step is to consider a simple medication regimen. One-provider remarks,

…first they are evaluated, orientation is provided about the medications that they will be taking, where they can get them and how they should be taken… It is voluntary decision. …If the woman decides at any moment that they want to stop treatment, they are allowed to, regardless of the reasons but they are also counseled about the consequences.

Even when women attempt to keep a true compromise to ART regimen, providers’ recognized that “they [the women] get to the point in which they are tired of taking medications and they decide to stop the treatment.” They have indicated that because women trust their providers, they usually tell them when their decision is made. At the same time, since, providers define themselves as “helpers”, when things like these happens, they are not judgmental, and use the strategy of giving “observed” time to women to see what happen.

Some providers’ also mentioned the difficulty women encounter accessing their medications through the health care system. A nurse provider said: “It’s difficult to receive medications at the local pharmacy”… there is a high volume of patients waiting for the same medication… services and processes are more difficult now.” A case manager reported,

Because the health care reform program sometimes the primary physician approves a prescription, but the insurance does not always cover it [the ART regimen] and patients can not pay high deductibles of $200–300.

Some providers’ (n=3) identify such a high co-payment for ART as a lack of sensitivity to people suffering from HIV infection.

Four providers were especially concerned with women that have one or more of the following characteristics: adolescents, low literacy, drug users, learning disabilities or mental retardation. They have found that these women demonstrated greater difficulties in following their medication schedule. In adolescents, these providers recognized that trying to convince this population about the importance to be adherent:

it is not an easy task …we have many barriers, its not just to say take it because it is for good for your health. That does not work with them… They are taking many medications and because of their ages and lifestyles, promoting adherence, which is a structured activity is very difficult for this population.

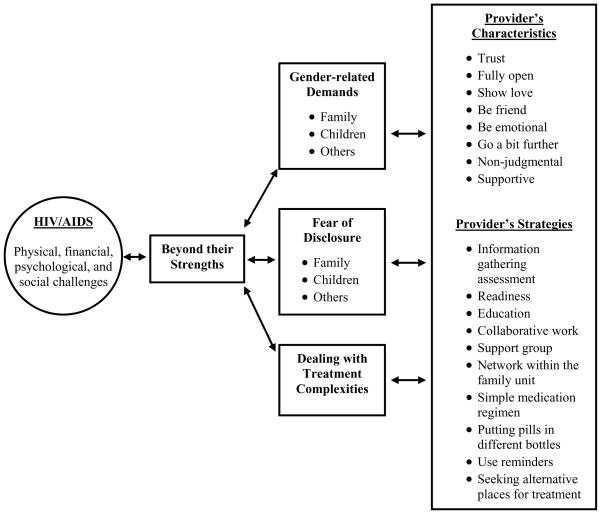

A physician commented that among drug-using women, treatment takes a “backseat to the drug use”, but when they are clean, “they do well.” Even when women have low literacy, learning disabilities or mental problems, providers’ work closely with them providing education in a simple way, using pictures, drawings, and charts to show them the necessity of health care services and day-by-day assistance with ART adherence. Similarly, Andersen et al. (2003) have demonstrated the effectiveness of using a personalized nursing care process among clients diagnosed with HIV, mental illness, and substance abuse by linking them to health care providers and using strategies to promote retention in health care. Figure 1 offers a visual representation of the central major categories, strategies and provider’s characteristics discussed in this paper.

Figure 1.

Visual representation of central theme, major categories contributing to non-adherence behavior, providers’ characteristics, and strategies to promote adherence among women’s with HIV/AIDS

Discussion

In light of the increasing numbers of women with HIV in Puerto Rico, and the multiple issues they confronted, make adherence particularly difficult. In this pilot study, the providers were likely to report strong feelings about the complex process of daily functioning of women living with HIV/AIDS infection that keep them “beyond their strengths” trying to deal with the burden of the illness and keep adherent to ART. The providers established the gender demands, fears of disclosure of the HIV/AIDS status, and treatment complexities as the main influencing factors for women’s adherence. Several providers expressed that for women having HIV infection in their lives and responding to traditional gender expectations, make it challenging for them to focus on their health and follow nearly perfect adherence to antiretroviral therapy. In accordance to what other studies have found, providers in this study recognized that gender demands play an integral role in determining women’s vulnerability to infection, their ability to access care, support, treatment, and their ability to cope (Anderson, Marcovici, & Taylor, 2002; Gupta, Whelan, & Allendorf, 2003; Ingram & Hutchinson, 2000; Misener & Sowell, 1998; Russell, Alexander, & Corbo, 2000). In this study, family and pregnancy were two main motivators identified by providers that influence women’s decision to stay adherent to treatment. This is because “familismo” has a fundamental role in Puerto Rican culture and family is seen as the most important social unit and its structure extends far beyond the nuclear family. Within the context of traditional familism, Hispanic women and recognize and value family and children and bear responsibility as the primary source of care for the entire family (Sabogal, Marin, Otero-Sabogal, Vanoss Marin, & Perez-Stable, 1987). A high level of perceived family support and having someone to live for is the most essential dimension of Hispanic familism and extremely important in terms of patient adherence (Murphy, Roberts, Martin, Marelich, & Hoffman, 2004). Another recurrent theme was related to the fear of revealing the diagnosis, which significantly adds to the complexity surrounding gender demands by placing a burden on women’s lives. Although the fear of stigma permeates these women’s lives and affects their adherence, disclosure of the diagnosis was very important for providers in this study because, many have had experiences in their clinic that show that women are less depressed and more adherent when receiving support from their family and partners. In addition, when women reveal their diagnosis they do not have to hide to receive services, which in turn promote their access to care on an ongoing basis. The revelation of diagnosis to family, partners, and friends can both improve adherence and be empowering to women with HIV infection. Establishing assistance programs for the discussion of women’s perceptions of stigma and the process of diagnosis revelation needs to be expanded in Puerto Rico.

Literature shows that the provider-patient relationship is a key component that can positively influence adherence. A relationship with a provider that is based on trust, consistency, access, and continued interaction has been identified as being important to promote and improve adherence (Abel & Painter, 2003; Altice & Friedland, 1998; Murphy et al., 2003; Reynolds, 2004; van Servellen et al., 2005). In this study, providers also believe that it is important for women to have a trusting relationship with them, that they must be accessible, non-judgmental, and supportive to women. One key difference between providers elsewhere and those in Puerto Rico is that whether a provider is a man or a woman, they have no problem crossing the line of a structured therapeutic relationship and go a bit further to show love and emotion and be a friend to the women. This strategy seems to positively influence women’s sense of trust and it also encourages them to share information more openly with providers. These behaviors could be explained as part of a cultural value called “personalismo” in Puerto Rico. Personalismo, the need to relate to people and not to institutions (Rogler & Cooney, 1984) goes beyond the traditional medical model approach of providing care from a presumably objective and emotionally neutral position. Among Hispanic/Latinos, “personalismo” accords great value to personal character and inner qualities, and represents a preference for people within the same ethnic group (Marin & Marin, 1991). In social relationships, warmth, trust, and respect form the foundation for interpersonal connectedness, cooperation, and mutual reciprocity (Flores, Eyre, & Millstein, 1998; Gloria & Peregoy, 1996). Providers must evaluate the practicability of “personalismo” and work within this traditional concept in addition to existing educational, behavioral, and cognitive interventions to promote adherence on these women. Additionally, researchers must be familiar with these values because they may affect the process and outcome of working with women with HIV/AIDS infection and adherence.

The study has several limitations, which include a small sample, and a heterogeneous group of providers serving women living with HIV/AIDS. Even with the small number of participants and the heterogeneity, the themes that emerged and the strategies used by some Puerto Rican providers to promote adherence in women cannot be ignored. Although findings cannot be generalized to all providers working with women with HIV, they may be transferable to others providers in similar situations (Lincoln & Guba, 1985) and also provide some guidelines that can be taken into consideration when addressing the issue of adherence among women living with HIV/AIDS in Puerto Rico. Considerations for future research include: (a) expanding the study size but keeping the heterogeneity to further explore the provider’s experiences; (b) conducting further research using mixed-method approaches to collect additional information; and (c) creating culturally sensitive and non-judgmental interventions tailored to Puerto Rico women’s lifestyles and beliefs, to promote and enhance ART adherence.

Biographies

Dr. Marta Rivero-Méndez is professor of nursing and the Director of the Doctoral program at the School of Nursing of the University of Puerto Rico, Medical Sciences Campus. She is a member of the UCSF HIV/AIDS International Nursing Research Network. Her research focuses on HIV symptoms’ management and experience, women, medication adherence and functional health literacy in persons living with HIV/AIDS in Puerto Rico as well as risk factors for STI’s in immigrant women.

Carol Dawson Rose PhD, RN is an associate professor of nursing at the University of California, San Francisco. Her research focuses on HIV health care experience of patients and providers.

Solymar S. Solís-Báez, BA., PhD(c) is a Doctoral Candidate in clinical psychology at the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras Campus as well as Project Director of the Nursing Research Center on HIV/AIDS Health Disparities of the School of Nursing of the University of Puerto Rico, Medical Sciences Campus. She has worked with Dr. Rivero for the past six years, conducting research on symptom management and experience, adherence and health literacy in persons living with HIV/AIDS in Puerto Rico.

Appendix

Semi-structured Interview Guide used with Health Care Provider’s

What are the providers’ perceptions of their experiences treating women with HIV/AIDS? (Probe: Opening Question: What is the process of how women are assigned to you? How do they become your patients? Can you tell me about your experience (s) treating women with HIV infection? Are the women different than the men that you treat? How they are different? Lifestyle? Life circumstances? Children?)

How do they feel about women capability of taking medication as it has been prescribed? (Probe: Can you tell me a story or give me a specific example of a situation where a woman patient of yours had difficulty taking the antiretroviral medication that was prescribed? What got in her way? How is this different from men?)

What resources and strategies are used by these women to make decisions about therapy? (Probe: Tell me how decisions are made about which medication to use?)

What factors as a healthcare provider perceive as barriers for women’s adherence to treatment? (Probe: What are some of the challenges that women have taking their medications?

-

What factors do they perceive as facilitators?)

(Probe: What are some of the things (supports) in woman’s life that helps women to keep adherence with their HIV treatment? Can you tell me a story or a specific example of a situation where a women patient of yours was successful adhering to her HIV medication treatment? What do you think helped her? How is different than from men?)

-

What are some of the criteria that are used to assess women for initiation and/or continuation of treatment?

(Probe: I want you to compare your experience treating men with your experiences treating women, what are your criteria for initiating or continuing medication? 7) What are some of the strategies implemented in the clinic to improve adherence with antiretroviral therapy regimen in women?)

(Probe: What has been implemented in the clinic or in your practice to improve adherence with antiretroviral medication for women specifically?)

Closing question: Is there anything else you want to tell me about your experience taking care of women with HIV?

Contributor Information

Marta Rivero-Méndez, University of Puerto Rico, Puerto Rico, USA.

Carol S. Dawson-Rose, University of California San Francisco, California, USA

Solymar S. Solís-Báez, University of Puerto Rico, Puerto Rico, USA

References

- Abel E, Painter L. Factors that influence adherence to HIV medications: Perceptions of women and health care providers. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2003;14:61–69. doi: 10.1177/1055329003252879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam BD, Maticka-Tyndale E, Cohen JJ. Adherence practices among people living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2003;15:263–274. doi: 10.1080/0954012031000068407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altice FL, Friedland GH. The era of adherence to HIV therapy. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1998;129:503–505. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-6-199809150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammassari A, Trotta MP, Murri R, Castelli F, Narciso P, Noto P, et al. Correlates and predictors of adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy: Overview of published literature. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2002;15(Suppl 3):123–127. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200212153-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen M, Smereck GA, Hockman E, Tinsley J, Milfort D, Shekoski C, et al. Integrating health care for women diagnosed with HIV infection, substance abuse and mental illness in Detroit, Michigan. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2003;14(5):49–58. doi: 10.1177/1055329003252055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson H, Marcovici K, Taylor K. The UNGASS, Gender and women’s vulnerability to HIV/AIDS in Latin America and the Caribbean. Washington DC: Pan-American Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bakken S, Holzemer WL, Brown MA, Powell-Cope GM, Turner JG, Inouye J, et al. Relationships between perception of engagement with health care provider and demographic characteristics, health status, and adherence to therapeutic regimen in persons with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2000;14:189–197. doi: 10.1089/108729100317795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck CT. Qualitative research: The evaluation of its credibility, fittingness, and audit ability. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1993;15:263–266. doi: 10.1177/019394599301500212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne M. Sampling for qualitative research. AORN Journal. 2001;73:494, 497–498. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2092(06)61990-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caribbean Epidemiology Centre. The Caribbean HIV/AIDS epidemic and the situation in member countries of the Caribbean Epidemiology Centre (CAREC) 2007 February; Retrieved March 25, 2008, from http://www.carec.org/documents/Caribbean_HIV_Epidemic.pdf.

- Chesney M. Adherence to HAART regimens. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2003;17:169–177. doi: 10.1089/108729103321619773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciambrone D, Loewenthal HG, Bazerman LB, Zorilla C, Urbina B, Mitty JA. Adherence among women with HIV infection in Puerto Rico: The potential use of modified directly observed therapy (MDOT) among pregnant and postpartum women. Women & Health. 2006;44(4):61–77. doi: 10.1300/j013v44n04_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW. Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. 2. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Deschamps AE, Graeve VD, van Wijngaerden E, De Saar V, Vandamme AM, van Vaerenbergh K, et al. Prevalence and correlates of nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy in a population of HIV patients using medication event monitoring system. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2004;18:644–657. doi: 10.1089/apc.2004.18.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores E, Eyre SL, Millstein SG. Sociocultural beliefs related to sex among Mexican American adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1998;20:60–82. [Google Scholar]

- Fogarty L, Roter D, Larson S, Burke J, Gillespie J, Levy R. Patient adherence to HIV medication regimens: A review of published and abstract reports. Patient Education and Counseling. 2002;46:93–108. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00219-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank L, Waldron K, Jerrett J, Rowe C, Fisk S. Treatment adherence: Assessment of healthcare provider assumptions and implications for clinical practice [Abstract] International Conference on AIDS. 1998;12:593. [Google Scholar]

- Gloria AM, Peregoy JJ. Counseling Latino alcohol and other substance users/abusers: Cultural considerations for counselors. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1996;13:119–126. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(96)00035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffmam E. Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T, Taylor R. How to read a paper: Papers that go beyond numbers (qualitative research) British Medical Journal. 1997;315:740–743. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7110.740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta GR, Whelan D, Allendorf K. Integrating gender into HIV/AIDS programmes: A review paper. Washington, D.C: International Center for Research on Women (ICRW), World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Henry Kaiser Family Foundation. The global HIV/AIDS epidemic. HIV/AIDS Policy Fact Sheet. 2007 June; Retrieved April 13, 2008, from http://www.kff.org/hivaids/upload/3030_09.pdf.

- Heyer A, Ogunbanjo GA. Adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy Part I: A review of factors that influence adherence. South African Family Practice. 2006;48(8):5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hill Z, Kendall C, Fernandez M. Patterns of adherence to antiretroviral: Why adherence has no simple measure. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2003;17:519–525. doi: 10.1089/108729103322494311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson S. Creating meaning: A grounded theory of NICU nurses. In: Chenitz WC, Swanson JM, editors. From practice to grounded theory qualitative research in nursing. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley; 1986. pp. 191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram D, Hutchinson SA. Double binds and the reproductive and mothering experiences of HIV-positive women. Qualitative Health Research. 2000;10:117–132. doi: 10.1177/104973200129118282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. AIDS epidemic update. 2007 December; Retrieved April 22, 2008, from http://data.unaids.org/pub/EPISlides/2007/2007_epiupdate_en.pdf.

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Madru N. Stigma and HIV: Does the social response affect the natural course of the epidemic? Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2003;14(5):39–48. doi: 10.1177/1055329003255112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin G, Marin BV. Research with Hispanic populations. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Bangsberg DR, Singh S, Rachlis B, Wu P, et al. Adherence to HAART: A systematic review of developed and developing nation patient-reported barriers and facilitators. PloS Medicine. 2006;3(11):438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misener TR, Sowell RL. HIV infected women’s decisions to take antiretroviral. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1998;20:431–447. doi: 10.1177/019394599802000403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DA, Roberts KJ, Martin DJ, Marelich W, Hoffman D. Barriers to antiretroviral adherence among HIV-infected adults. In: Laurence J, editor. Medication adherence in HIV/AIDS. New York, NY: Liebert Publications; 2004. pp. 107–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DA, Roberts KJ, Hoffman D, Molina A, Lu MC. Barriers and successful strategies to antiretroviral adherence among HIV-infected monolingual Spanish-speaking patients. AIDS Care. 2003;15:217–230. doi: 10.1080/0954012031000068362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan American Health Organization. Regional HIV/STI Plan for the Health Sector 2006–2015. Washington, D.C: Author; 2005. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- Pilcher CD, Eron JJ, Galvin S, Gay C, Cohen MS. Acute HIV revisited: New opportunities for treatment and prevention. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2004;113(7):937–945. doi: 10.1172/JCI21540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polit DF, Beck CT. Essentials of nursing research: Methods, appraisal, and utilization. 6. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Puerto Rico AIDS Surveillance Program. Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico: Department of Health, Puerto Rico; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Puerto Rico HIV Surveillance Program. Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico: Department of Health, Puerto Rico; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Relf MV, Mallinson K, Pawlowski L, Dolan K, Dekker D. HIV-related stigma among persons attending an urban HIV clinic. The Journal of Multicultural Nursing & Health. 2005;11(1):14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Remien RH, Hirky AE, Johnson MO, Weinhardt LS, Whittier D, Le GM. Adherence to medication treatment: A qualitative study of facilitators and barriers among diverse sample of HIV + men and women in four US cities. AIDS and Behavior. 2003;7:61–72. doi: 10.1023/a:1022513507669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds NR. Adherence to antiretroviral therapies: State of the science. Current HIV Research. 2004;2:207–214. doi: 10.2174/1570162043351309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts KJ. Physician-patient relationships, patient satisfaction, and antiretroviral medication adherence among HIV-infected adults attending a public health clinic. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2002;16:43–50. doi: 10.1089/108729102753429398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogler LH, Cooney RS. Puerto Rican families in New York City: Intergenerational processes. Maplewood, NJ: Waterfront Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Roldan I. AIDS stigma in the Puerto Rican community: An expression of other stigma phenomenon in Puerto Rican culture. Interamerican Journal of Psychology. 2007;41(1):41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Torres Y, Cintrón-Bou FN, Varas-Diaz N. AIDS-related stigma and health professionals in Puerto Rico. Interamerican Journal of Psychology. 2007;41(1):49–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell LD, Alexander MK, Corbo KF. Developing culture-specific interventions for Latinas to reduce HIV high-risk behaviors. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2000;11(3):70–76. doi: 10.1016/S1055-3290(06)60277-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabogal F, Marin G, Otero-Sabogal R, Vanoss-Marin B, Perez-Stable EJ. Hispanic familism and acculturation: What changes and what doesn’t? Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9:397–412. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. The problem of rigor in qualitative research. Advances in Nursing Science. 1986;8(3):27–37. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198604000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. “To be of use”: Enhancing the utility of qualitative research. Nursing Outlook. 1997;45:125–132. doi: 10.1016/s0029-6554(97)90043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AC, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Stone VE, Hogan JW, Schuman P, Rompalo AM, Howard AA, Korkontzelou C, et al. Antiretroviral regimen complexity, self-reported adherence, and HIV patients’ understanding of their regimens: Survey of women in the HER Study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2001;28:124–131. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200110010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surlis S, Hyde A. HIV-positive patients’ experiences of stigma during hospitalization. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2001;12:66–77. doi: 10.1016/S1055-3290(06)60185-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Servellen G, Nyamathi A, Carpio F, Pearce D, Garcia-Teague L, Herrera G, et al. Effects of a treatment adherence enhancement program on health literacy, patient-provider relationships, and adherence to HAART among low-income HIV-positive Spanish-speaking Latinos. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2005;19:745–759. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varas-Diaz N, Toro-Alfonso J, Serrano-Garcia I. My body, my stigma: Body interpretations in a sample of people living with HIV/AIDS in Puerto Rico. The Qualitative Report. 2005;19(1):122–142. Retrieved May, 22, 2008, from http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR0-1/varas-diaz.pdf.

- Vervoort SC, Borleffs JC, Hoepelman AI, Grypdonck MH. Adherence in antiretroviral therapy: A review of qualitative studies. AIDS. 2007;21:271–281. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328011cb20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner JH, Justice AC, Chesney M, Sinclair G, Weissman S, Rodriguez-Barradas M. Patient- and provider-reported adherence: Toward a clinically useful approach to measuring antiretroviral adherence. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2001;54(Suppl 1):91–98. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00450-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson HS, Hutchinson SA, Holzemer WL. Reconciling incompatibilities: A grounded theory of HIV medication adherence and symptom management. Qualitative Health Research. 2002;12:1309–1322. doi: 10.1177/1049732302238745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood SA, Tobias C, McCree J. Medication adherence for HIV positive women caring for children: In their own words. AIDS Care. 2004;16:909–913. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331290158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]