Abstract

We isolated 45 Helicobacter pylori strains from 217 child patients. Resistance to clarithromycin, metronidazole, amoxicillin, and tetracycline was detected in 27%, 13%, 4%, and 0% of strains, respectively. The A2143G mutation was the most prevalent (67%) among clarithromycin-resistant strains. In addition, strain genotyping revealed a significant association between gastritis severity and the simultaneous presence of cagA, vacA s1m1, iceA2, and babA2 genes.

Helicobacter pylori infection is found worldwide and constitutes a public health concern in many countries. Previous epidemiological studies have shown a high prevalence of H. pylori infection in Brazil (2, 20, 24). H. pylori infection, generally acquired in childhood, persists asymptomatically for decades in most individuals.

Amoxicillin, tetracycline, metronidazole, and clarithromycin are frequently used, combined with proton pump inhibitors or bismuth salts, for the treatment of H. pylori infections (25). However, antibiotic resistance is frequently associated with eradication failure (3, 16). Resistance to metronidazole and clarithromycin is population dependent, and several studies suggest that clarithromycin resistance is higher in strains isolated from children than in strains isolated from adults (10). In Brazil, the prevalence of clarithromycin-resistant strains in adults is reported to be from 7 to 10% (15, 18). However, little is known about the prevalence of clarithromycin-resistant H. pylori infection in Brazilian children.

The primary aims of this study were to determine the prevalence of clarithromycin-resistant H. pylori strains in children, to identify those isolates via rapid methodology, and to examine the severity of gastritis caused by the antibiotic-resistant H. pylori isolates. Metronidazole, amoxicillin, and tetracycline resistance was also studied. Furthermore, the study aimed to genotype the vacA and iceA genes and to detect the cagA gene in gastric biopsy specimens, since recent studies found a high frequency of cagA-positive and iceA2-positive strains as well as a strain with the vacA signal region genotype s1 and middle region sequence m1 among pediatric H. pylori isolates in Brazil (6, 7, 11, 23). This is also the first investigation of babA2 gene prevalence in Brazilian children.

A total of 217 consecutive child patients, aged 1 to 18 years (mean age, 10 years) (105 girls and 112 boys), who underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy for the evaluation of dyspeptic symptoms at the outpatient clinic of Pediatric Gastroenterology at the Instituto da Criança, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, during 2008 and 2009 were included. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital. Patients previously treated for H. pylori infections were not included.

Gastric biopsy specimens were processed for histological examination and evaluated according to the updated Sydney system of classification and grading of gastritis (4).

Antral gastric specimens were transported in sodium thioglycolate broth (Difco, Detroit, MI) in an ice bath and ground before submission to DNA extraction and PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) analysis with primers specific to the H. pylori 23S rRNA gene (17). The QIAmp tissue kit (Qiagen) was used for DNA extraction. Point mutations related to clarithromycin resistance in the 23S rRNA amplicon were investigated in all H. pylori isolates by PCR-RFLP using BsaI and MboII enzymes (27). The vacA, cagA, iceA, and babA2 genotypes were detected by PCR, as described elsewhere (1, 9, 21, 26, 28). In each experiment, H. pylori strain 26695 (ATCC 700392) was used as the positive-control strain.

H. pylori strains were cultured on Belo Horizonte medium (22) under microaerophilic atmosphere at 37°C for 3 to 7 days, and the isolates were identified by Gram staining and biochemical tests for oxidase, catalase, and urease production. Resistance to clarithromycin, metronidazole, amoxicillin, and tetracycline was determined by the disc diffusion method (Oxoid), and MICs were determined by the Etest according to the manufacturer's recommendations (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden). An isolate was considered resistant to clarithromycin or tetracycline if the MIC was >1 mg/liter and to metronidazole or amoxicillin if the MIC was >4 mg/liter (19).

Data were analyzed by the two-tailed χ2 test and Fisher exact test. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

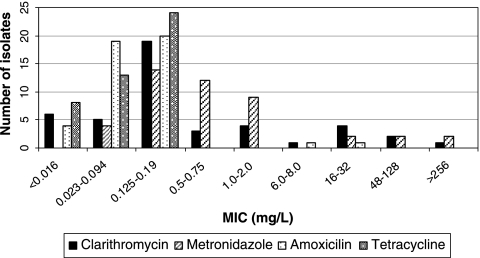

H. pylori was isolated in 45 (20.7%) of the 217 children; 12 (26.7%) of the 45 strains were clarithromycin resistant, 6 (13.3%) were metronidazole resistant, and 2 (4.4%) were amoxicillin resistant. All cultured H. pylori strains were susceptible to tetracycline (Fig. 1). No histological differences were observed between biopsy specimens with antibiotic-resistant strains and those with susceptible strains. PCR-RFLP was performed with all 12 clarithromycin-resistant isolates: 8 had the 23S rRNA A2143G point mutation, and 4 had the 23S rRNA A2142G mutation.

FIG. 1.

Distribution of MICs for the 45 H. pylori strains.

Among the 45 H. pylori-infected children, 13 had mild chronic gastritis, 28 had moderate chronic gastritis, 2 had marked chronic gastritis, and 2 had normal gastric mucosa. The percentage of H. pylori-infected children with chronic gastritis was 95.5% (43 patients), while 4.4% of the children (2 patients) had normal mucosa (P < 0.001).

vacA was detected in all 45 H. pylori-positive gastric biopsy specimens. The vacA genotypes s1m1, s2m2, and s1m2 or s2m1 were found in 57.7, 33.3, and 4.4% of the specimens, respectively. The iceA1 allele was detected in 9 (20%) and the iceA2 allele in 31 (68.9%) of the samples. Of the 45 H. pylori-positive biopsy specimens, 28 (62%) were cagA positive and 38 (84.4%) were babA2 positive. Correlation of histopathology results with vacA, cagA, and iceA genotypes showed that vacA s1m1-, cagA-, and iceA2-positive strains were more frequently found in patients with moderate and marked gastritis (77%) than in patients with mild gastritis (23%) (P < 0.001). Interestingly, in Slovenian children, vacA s1 and cagA were also shown to be associated with more pronounced chronic gastritis (12). In contrast, in Korean children, although vacA s1m1 cagA iceA1 was the predominant genotype, no association with gastritis severity was observed (14).

In conclusion, we found a high incidence of clarithromycin-resistant H. pylori strains (27%) in Brazilian children. Furthermore, we found an association between clarithromycin resistance and either the vacA s1m1 (P = 0.007) or the iceA2 (P = 0.038) genotype. The high level of clarithromycin resistance among strains from children compared to adults (15, 18) suggests the importance of susceptibility testing, especially in Brazilian children. All together, these data stress the relevance of susceptibility testing and genotyping for establishing antibiotic treatment in pediatric H. pylori infection.

In our study, PCR-RFLP proved to be a rapid and accurate method for the detection of clarithromycin resistance gene mutation directly in gastric biopsy samples. Only a few groups have studied mutations involved in clarithromycin resistance in strains obtained from children, and their results are similar to those obtained in our study (5, 13, 29).

Our data also demonstrate an association between H. pylori infection and gastritis in Brazilian children. In addition, we confirmed the reported association of infection with vacA s1m1 cagA iceA2-positive H. pylori strains and gastritis severity (6, 11, 23). Furthermore, a high frequency of babA2 was found among H. pylori isolates. Previous studies of adults in Brazil reported a high prevalence of babA2-positive strains from patients with different upper gastrointestinal diseases (8). The high incidence of babA2 in H. pylori Brazilian isolates suggests that this gene could be a useful marker for identifying patients with a high risk of H. pylori infection in Brazil.

Acknowledgments

Gabriella T. Garcia and Katia R. S. Aranda contributed equally to this work.

This work was supported by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientifíco e Tecnológico and Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 September 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atherton, J. C., T. L. Cover, R. J. Twells, M. R. Morales, C. J. Hawkey, and M. J. Blaser. 1999. Simple and accurate PCR-based system for typing vacuolating cytotoxin alleles of Helicobacter pylori. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2979-2982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braga, A. B., A. M. Fialho, M. N. Rodrigues, D. M. Queiroz, A. M. Rocha, and L. L. Braga. 2007. Helicobacter pylori colonization among children up to 6 years: results of a community-based study from northeastern Brazil. J. Trop. Pediatr. 53:393-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Broutet, N., S. Tchamgoué, E. Pereira, and F. Mégraud. 2000. Risk factors for failure of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy, p. 601-607. In R. H. Hunt and G. N. J. Tytgat (ed.), Helicobacter pylori: basic mechanisms to clinical cure 2000. Kluwer Academic Publishers and Axcan Pharma, Dordrecht, Netherlands.

- 4.Dixon, M. F., R. M. Genta, J. H. Yardley, and P. Correa. 1996. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney system. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 20:1161-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dzierzanowska-Fangrat, K., E. Rozynek, P. Jozwiak, D. Celinska-Cedro, K. Madalinski, and D. Dzierzanowska. 2001. Primary resistance to clarithromycin in clinical strains of Helicobacter pylori isolated from children in Poland. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 18:387-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gatti, L. L., F. J. Agostinho, R. W. Labio, F. B. Piason, L. C. Silva, V. F. Queiroz, C. A. Peres, D. Barbiere, M. A. C. Smith, and S. L. M. Payão. 2003. Helicobacter pylori and cagA and vacA gene status in children from Brazil with chronic gastritis. Clin. Exp. Med. 3:166-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gatti, L. L., R. W. Labio, L. C. Silva, M. A. C. Smith, and S. L. M. Payão. 2006. cagA positive Helicobacter pylori in Brazilian children related to chronic gastritis. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 10:254-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gatti, L. L., J. L. P. Modena, S. L. M. Payão, M. A. C. Smith, Y. Fukuhara, J. L. P. Modena, R. B. Oliveira, and M. Brocchi. 2006. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori cagA, iceA and babA2 alleles in Brazilian patients with gastrointestinal diseases. Acta Trop. 100:232-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerhardt, M., N. Lehn, N. Neumayer, T. Boren, R. Rad, W. Schepp, S. Mieklke, M. Classen, and C. Prinz. 1999. Clinical relevance of the Helicobacter pylori gene for blood-group antigen-binding adhesion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:12778-12783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glupczynski, Y., F. Mégraud, M. López-Brea, and L. P. Andersen. 2001. European multicentre survey of in vitro antimicrobial resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 20:820-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gusmão, V. R., E. N. Mendes, D. M. M. Queiroz, G. A. Rocha, A. M. C. Rocha, A. A. R. Ashour, and A. S. T. Carvalho. 2000. vacA genotypes in Helicobacter pylori strains isolated from children with and without duodenal ulcer in Brazil J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2853-2857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Homan, M., B. Luzar, B. J. Kocjan, R. Orel, T. Mocilnik, M. Shrestha, M. Kveder, and M. Poljak. 2009. Prevalence and clinical relevance of cagA, vacA, and iceA genotypes of Helicobacter pylori isolated from Slovenian children. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 49:289-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato, S., S. Fujimura, H. Udagawa, T. Shimizu, S. Maisawa, K. Ozawa, and K. Iinuma. 2002. Antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori strains in Japanese children. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:649-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ko, J. S., K. M. Kim, Y. L. Oh, and J. K. Seo. 2008. cagA, vacA, and iceA genotypes in Helicobacter pylori in Korean children. Pediatr. Int. 50:628-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magalhães, P. P., D. M. M. Queiroz, D. V. C. Barbosa, G. A. Rocha, E. N. Mendes, A. Santos, P. R. V. Correa, A. M. C. Rocha, L. M. Teixeira, and C. A. Oliveira. 2002. Helicobacter pylori primary resistance to metronidazole and clarithromycin in Brazil. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2021-2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mégraud, F. 1997. Resistance of Helicobacter pylori to antibiotics. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 11(Suppl. 1):43-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meier, A., P. Kirschner, B. Springer, V. A. Steingrube, B. A. Brown, R. J. Wallace, Jr., and E. C. Böttger. 1994. Identification of mutations in 23S rRNA gene of clarithromycin-resistant Mycobacterium intracellulare. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:381-384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mendonça, S., C. Ecclissato, M. S. Sartori, A. P. O. Godoy, R. A. Guerzoni, M. Degger, and J. Pedrazzoli, Jr. 2000. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori resistance to metronidazole, clarithromycin, amoxicillin, tetracycline, and furazolidone in Brazil. Helicobacter 5:79-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.NCCLS. 2000. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Tenth informational supplement (aerobic dilution). NCCLS M100-S10 (M7). National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, PA.

- 20.Parente, J. M. L., B. B. Silva, M. P. S. Palha-Dias, S. Zaterka, N. F. Nishimura, and J. M. Zeitune. 2006. Helicobacter pylori infection in children of low and high socioeconomic status in northeastern Brazil. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 75:509-512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peek, R. M., G. G. Miller, K. T. Tham, G. I. Pérez-Pérez, T. L. Cover, J. C. Atherton, G. D. Dunn, and M. J. Blaser. 1995. Detection of Helicobacter pylori gene expression in human gastric mucosa. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:28-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Queiroz, D. M., E. N. Mendes, and G. A. Rocha. 1987. Indicator medium for isolation of Campylobacter pylori. J. Clin. Microbiol. 25:2378-2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Queiroz, D. M., E. N. Mendes, A. S. T. Carvalho, G. A. Rochs, A. M. R. Oliveira, T. F. Soares, A. Santos, M. M. D. A. Cabral, and A. M. M. F. Nogueira. 2000. Factors associated with Helicobacter pylori infection by a cagA-positive strain in children. J. Infect. Dis. 181:626-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rocha, G. A., A. M. C. Rocha, L. D. Silva, A. Santos, A. C. D. Bocewicz, R. M. Queiroz, J. Bethony, A. Gazzinelli, R. Correa-Oliveira, and D. M. M. Queiroz. 2003. Transmission of Helicobacter pylori infection in families of preschool-aged children from Minas Gerais, Brazil. Trop. Med. Int. Health 8:987-991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Unge, P. 1998. Antimicrobial treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection—a pooled efficacy analysis of eradication therapies. Eur. J. Surg. 582:16-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Doorn, L. J., C. Figueredo, R. Rossau, G. Jannes, M. Asbroeck, J. C. Souza, F. Carneiro, and W. G. V. Quint. 1998. Typing of Helicobacter pylori vacA gene and detection of cagA by PCR and reverse hybridization. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1271-1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Versalovic, J., D. Shortridge, K. Kibler, M. V. Griffy, J. Beyer, R. K. Flamma, S. K. Tanaka, D. Graham, and M. F. Go. 1996. Mutations in 23S rRNA are associated with clarithromycin resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:477-480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamaoka, Y., T. Kodama, O. Gutierrez, J. G. Kim, K. Kashima, and D. Y. Graham. 1999. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori iceA, cagA, and vacA status and clinical outcome: studies in four different countries. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2274-2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang, Y. J., J. C. Yang, Y. M. Jeng, M. H. Chang, and Y. H. Ni. 2001. Prevalence and rapid identification of clarithromycin-resistant Helicobacter pylori isolates in children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 20:662-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]