Abstract

The identification of Nocardia species, usually based on biochemical tests together with phenotypic in vitro susceptibility and resistance patterns, is a difficult and lengthy process owing to the slow growth and limited reactivity of these bacteria. In this study, a panel of 153 clinical and reference strains of Nocardia spp., altogether representing 19 different species, were characterized by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). As reference methods for species identification, full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing and phenotypical biochemical and enzymatic tests were used. In a first step, a complementary homemade reference database was established by the analysis of 110 Nocardia isolates (pretreated with 30 min of boiling and extraction) in the MALDI BioTyper software according to the manufacturer's recommendations for microflex measurement (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Leipzig, Germany), generating a dendrogram with species-specific cluster patterns. In a second step, the MALDI BioTyper database and the generated database were challenged with 43 blind-coded clinical isolates of Nocardia spp. Following addition of the homemade database in the BioTyper software, MALDI-TOF MS provided reliable identification to the species level for five species of which more than a single isolate was analyzed. Correct identification was achieved for 38 of the 43 isolates (88%), including 34 strains identified to the species level and 4 strains identified to the genus level according to the manufacturer's log score specifications. These data suggest that MALDI-TOF MS has potential for use as a rapid (<1 h) and reliable method for the identification of Nocardia species without any substantial costs for consumables.

Nocardia spp. are ubiquitous bacteria dispersed in vegetation, dust, soil, freshwater, and salt water that are isolated with increasing frequency from clinical specimens, especially those from immunocompromised patients (1).

The taxonomy of the genus Nocardia has undergone major changes during the last decades, and currently more than 50 species have been characterized by phenotypic and molecular methods, besides a number of unnamed genomospecies (2). Not all of them have been found in humans, and Nocardia asteroides, previously considered the species most frequently isolated from clinical specimens, has been shown to be heterogeneous and has been divided into several species (2). Moreover, several additional species of human origin have been recently described and reported (5, 6).

The routine identification of Nocardia strains to the species level by conventional phenotypical methods is a fastidious and time-consuming process owing to the limited biochemical reactivity of these organisms, often requiring 1 or more days to complete identification. Moreover, the available tests may be difficult to interpret and inconclusive and require dedicated trained staff. In order to overcome these drawbacks, molecular methods such as 16S rRNA gene sequencing and PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of both the 65-kDa heat shock protein-encoding gene (hsp65) and the 16S rRNA gene have been recently advocated for Nocardia species identification (3). However, these methods remain accessible to reference laboratories only and are difficult to implement for routine bacterial identification in a clinical laboratory.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) can analyze the protein composition of a bacterial cell and has emerged as a new technology for species identification. By measuring the exact sizes of peptides and small proteins, which are assumed to be characteristic for each bacterial species, it allows determination to the species level within a few minutes when the analysis is performed on whole cells, cell lysates, or crude bacterial extracts (8). Through the improvement of the technique, MALDI-TOF MS has proved over the recent years to be a rapid, accurate, easy-to-use, and inexpensive method for the universal identification of microorganisms (11). Until now, MALDI-TOF MS has been challenged for the identification of various groups of microorganisms, including Gram-positive bacteria, Enterobacteriaceae, Gram-negative nonfermenters, mycobacteria, anaerobes, and yeasts (8, 9, 11-13). In this respect, the use of MALDI-TOF MS as a tool for the identification of fastidious, slow-growing organisms such as Nocardia species, which are notoriously difficult to identify by conventional tests, in the routine laboratory appeared to us of major interest. One factor limiting the use of MALDI-TOF MS remains the limited availability of reference data sets for microorganisms that are infrequently isolated from clinical specimens, and it has been shown previously that the absence or the availability of only a small number of isolates of a given species in the reference database may account for most of the cases in which no identification can be obtained by the MALDI-TOF MS method (11).

In this study, we therefore aimed to establish a large reference database for the MALDI-TOF MS-based identification of Nocardia species isolates. In a first step, we developed a simple modified extraction procedure based on boiling for 30 min, followed by ethanol-formic acid extraction, and we generated our own spectrum database issued from a large collection of clinical and reference Nocardia sp. isolates. Following the establishment of our reference database, we subsequently evaluated the methodology against 43 blind-coded clinical isolates of Nocardia species that were analyzed by phenotypical, biochemical, and enzymatic tests and by full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing, which was used as the reference identification method.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Overall, 153 Nocardia strains were collected for the study, of which 134 were from clinical specimens and 19 were reference strains of the most commonly isolated species. The clinical Nocardia isolates had all been isolated from clinical specimens in Belgium between 1990 and 2009 and were referred by several Belgian clinical laboratories to one of us (G.W.) for confirmation of identification by conventional biochemical and enzymatic tests and by sequencing of the entire16S rRNA gene according to previously published methods (16). Susceptibilities to 11 antimicrobial agents were furthermore determined by Etest for all Nocardia strains (5). The clinical origins of the strains were as follows: 38 strains were isolated from the respiratory tract, 20 were from wounds, 13 were from blood, 8 were from brain abscesses or cerebrospinal fluid, and 55 were of unknown origin. All of the Nocardia strains available in our collection were included in the study in order to avoid any strain selection bias. One hundred ten Nocardia isolates, comprising 91 randomly selected clinical strains identified in our laboratory and the 19 reference strains of the most relevant Nocardia species, were selected to generate our own spectrum database, while 43 blind-coded Nocardia clinical isolates representative of the various species available in our collection were subsequently analyzed for the challenge identification part of the study. The distribution of the different Nocardia species is listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Species distribution of 153 Nocardia isolates subjected to analysis by MALDI-TOF MS

| Species | Reference strain(s) in own database (n = 19)a | No. of clinical isolates |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| In own database (n = 91) | Tested for identification (n = 43) | ||

| Nocardia abscessus | DSM44432Tb | 5 | 4 |

| Nocardia africana | DSM44491b | ||

| Nocardia asiatica | DSM44668 | 1 | |

| Nocardia asteroides | DSM43258, NCTC11293T | ||

| Nocardia beijingensis | 1 | ||

| Nocardia brasiliensis | NCTC11294T | 6 | 3 |

| Nocardia carnea | DSM46071, DSM44558, DSM43397T | 2 | 1 |

| Nocardia cyriacigeorgica | DSM44484Tb | 11 | 5 |

| Nocardia elegans | 1 | ||

| Nocardia farcinica | DSM43665Tb | 40 | 12 |

| Nocardia niigatensis | DSM44670b | 1 | |

| Nocardia nova | DSM43207T | 21 | 15 |

| Nocardia otitidiscaviarum | NCTC1934T | ||

| Nocardia paucivorans | DSM44386Tb | 2 | |

| Nocardia pseudobrasiliensis | DSM44290 | ||

| Nocardia puris | DSM44599T | ||

| Nocardia shimofusensis | 1 | ||

| Nocardia transvalensis | DSM43405Tb | ||

| Nocardia veterana | DSM44445T | 1 | 1 |

A superscript capital T indicates the type strain.

Nocardia reference strain also included in the original software of the MALDI BioTyper database (Bruker Daltonik GmbH).

All of the strains were cultivated on Trypticase soy blood agar with 5% sheep blood (TSA; bioMérieux, Marcy-L'Etoile, France) and incubated for 48 to 72 h at 37°C. A subset of 10 Nocardia isolates was also cultivated on Sabouraud agar (bioMérieux, Marcy-L'Etoile, France) and on Löwenstein-Jensen medium (Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France). For each microorganism, approximately 10 colonies were scraped from the agar and added to 500 μl distilled water. A modified extraction procedure consisted of boiling the mixture for 30 min, followed by a 2-min centrifugation at 13,000 rpm (10,000 × g). The supernatant was removed, and the pellet was mixed with 300 μl distilled water, followed by the addition of 900 μl ethanol. Two series of centrifugation for 2 min at 13,000 rpm and complete supernatant removal were necessary to obtain a dried pellet. The pellet was suspended in 50 μl of formic acid (70%) and incubated for 15 min at room temperature. Finally, 50 μl of acetonitrile was gently added and the mixture was centrifuged for 2 min at 13,000 rpm. The supernatant was the final product of the extraction procedure, and it was subjected to MALDI-TOF MS analysis.

MALDI-TOF MS.

MALDI-TOF MS measurements were performed on a microflex LT (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Leipzig, Germany) provided with a 20-Hz nitrogen laser. Spectra were recorded in the positive linear mode with an accelerating voltage of 20 kV and analyzed over a mass range of 2,000 to 20,000 Da. Each series of measurements was preceded by calibration with a bacterial test standard (BTS 255343; Bruker Daltonik).

Establishment of a Nocardia database.

One microliter of the final extraction product of the Nocardia strain was spotted eight times onto a steel target. Directly after drying in air, each spot was overlaid with 1 μl of matrix. The matrix used was a saturated solution of α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid dissolved in a basic organic solvent composed of 50% acetonitrile and 2.5% trifluoroacetic acid. Each spot was measured three times by the MBT_FC.par flexControl method and the MBT-autoX.axe autoExecute method. Every measurement resulted from six series of 40 laser shots at different positions on the spotted product. The 24 spectra obtained were closely analyzed in the flexAnalysis program with a major alertness for intrusive peaks. Finally, a minimum of 20 accurate spectra out of 24 were downloaded in the MALDI BioTyper software and assembled in order to generate a single mean spectrum accounting for the extracted Nocardia strain with the BioTyper MSP creation standard method. In order to appreciate the correlation between the organisms and visualize the clustering, a dendrogram was calculated with the MALDI BioTyper software. Distance values in a dendrogram are relative and always normalized to a maximal value of 1,000.

MALDI-TOF MS identification of Nocardia challenge strains.

One microliter of the extraction product of the Nocardia clinical strain was spotted once onto the target, followed by the addition of 1 μl matrix on each spot and measurement by the MBT_FC.par flexControl method. The bacterial spectra acquired by MALDI-TOF MS were analyzed in the MALDI BioTyper 2.0 software incorporating the MALDI BioTyper database and our own established Nocardia database. A first score was obtained after submitting the downloaded raw spectra to the original MALDI BioTyper database version 3.0.2 bearing the spectra of 3,486 cellular organism, while a second score resulted from the association of the former database and our own Nocardia database. Identification results and best matching scores are displayed in Table 2. The score indicated is a logarithmic value resulting from the alignment of the peak list of the unknown raw spectrum and the best matching database spectrum. According to the specifications of the manufacturer, a high log score of ≥2 was required for identification to the species level and an intermediate log score lying between <2 and ≥1.7 was required for identification to the genus level. A low score of <1.7 was considered unreliable for identification. The raw spectra of the 43 Nocardia clinical isolates were obtained through a unique run.

TABLE 2.

Best-match identification results and scores of 43 blind-coded clinical Nocardia isolates with the MALDI BioTyper database alone and enriched with our own Nocardia database

| Strain no. | Clinical isolate | MALDI BioTyper database |

MALDI BioTyper database and own Nocardia database |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identification result | Score | Identification result | Score | ||

| 101 | Nocardia farcinica | Nocardia farcinica | 1.491 | Nocardia farcinica | 2.385 |

| 102 | Nocardia nova | Nocardia nova | 1.965 | Nocardia nova | 2.356 |

| 103 | Nocardia beijingensis | Neisseria meningitidis | 1.260 | Nocardia abscessus | 1.586 |

| 104 | Nocardia abscessus | Nocardia abscessus | 1.616 | Nocardia abscessus | 1.616 |

| 105 | Nocardia nova | Nocardia nova | 1.979 | Nocardia nova | 2.382 |

| 106 | Nocardia nova | Nocardia nova | 2.233 | Nocardia nova | 2.547 |

| 107 | Nocardia abscessus | Nocardia abscessus | 1.523 | Nocardia abscessus | 2.318 |

| 108 | Nocardia nova | Nocardia nova | 2.013 | Nocardia nova | 2.560 |

| 109 | Nocardia nova | Nocardia nova | 1.878 | Nocardia nova | 2.403 |

| 110 | Nocardia brasiliensis | Nocardia species | 2.084 | Nocardia brasiliensis | 2.255 |

| 111 | Nocardia nova | Nocardia nova | 1.973 | Nocardia nova | 2.347 |

| 112 | Nocardia nova | Nocardia nova | 2.122 | Nocardia nova | 2.546 |

| 113 | Nocardia farcinica | Clostridium chauvoei | 1.43 | Nocardia farcinica | 2.421 |

| 114 | Nocardia abscessus | Nocardia abscessus | 1.746 | Nocardia abscessus | 2.107 |

| 115 | Nocardia nova | Nocardia nova | 2.227 | Nocardia nova | 2.571 |

| 116 | Nocardia cyriacigeorgica | Lactobacillus kalixensis | 1.110 | Nocardia cyriacigeorgica | 2.108 |

| 117 | Nocardia nova | Nocardia nova | 2.028 | Nocardia nova | 2.389 |

| 118 | Nocardia abscessus | Nocardia abscessus | 1.665 | Nocardia abscessus | 2.346 |

| 119 | Nocardia carnea | Pandoraea pulmonicola | 1.423 | Pandoraea pulmonicola | 1.423 |

| 120 | Nocardia nova | Nocardia nova | 1.988 | Nocardia nova | 2.257 |

| 121 | Nocardia farcinica | Nocardia farcinica | 1.322 | Nocardia farcinica | 2.293 |

| 122 | Nocardia cyriacigeorgica | Nocardia sp. | 1.17 | Nocardia cyriacigeorgica | 1.870 |

| 123 | Nocardia shimofusensis | Nocardia testacea | 1.73 | Nocardia testacea | 1.733 |

| 124 | Nocardia nova | Nocardia aobensis | 1.72 | Nocardia nova | 1.846 |

| 125 | Nocardia farcinica | Clostridium septicum | 1.24 | Nocardia farcinica | 2.255 |

| 126 | Nocardia farcinica | Nocardia farcinica | 1.38 | Nocardia farcinica | 2.266 |

| 127 | Nocardia farcinica | Kocuria rosea | 1.29 | Nocardia farcinica | 2.153 |

| 128 | Nocardia farcinica | Nocardia farcinica | 1.25 | Nocardia farcinica | 2.337 |

| 129 | Nocardia nova | Nocardia nova | 2.19 | Nocardia nova | 2.367 |

| 130 | Nocardia nova | Nocardia nova | 2.06 | Nocardia nova | 2.511 |

| 131 | Nocardia brasiliensis | Issatchenkia occidentalis | 1.2 | Issatchenkia occidentalis | 1.204 |

| 132 | Nocardia veterana | Arthrobacter polychrolactophilus | 1.25 | Nocardia nova | 1.689 |

| 133 | Nocardia farcinica | Alcaligenes faecalis | 1.29 | Nocardia farcinica | 1.988 |

| 134 | Nocardia brasiliensis | Nocardia species | 1.94 | Nocardia brasiliensis | 2.318 |

| 135 | Nocardia farcinica | Nocardia species | 1.297 | Nocardia farcinica | 2.406 |

| 136 | Nocardia farcinica | Lactobacillus oligofermentans | 1.297 | Nocardia farcincia | 2.045 |

| 137 | Nocardia farcinica | Clostridium septicum | 1.347 | Nocardia farcinica | 2.229 |

| 138 | Nocardia nova | Nocardia nova | 2.066 | Nocardia nova | 2.285 |

| 139 | Nocardia cyriacigeorgica | Streptococcus gordonii | 1.34 | Nocardia cyriacigeorgica | 2.113 |

| 140 | Nocardia cyriacigeorgica | Candida glabrata | 1.288 | Nocardia cyriacigeorgica | 2.097 |

| 141 | Nocardia cyriacigeorgica | Issatchenkia orientalis | 1.385 | Nocardia cyriacigeorgica | 2.117 |

| 142 | Nocardia farcinica | Issatchenkia orientalis | 1.379 | Nocardia farcinica | 2.031 |

| 143 | Nocardia nova | Nocardia nova | 2.144 | Nocardia nova | 2.322 |

RESULTS

Establishment of a Nocardia database.

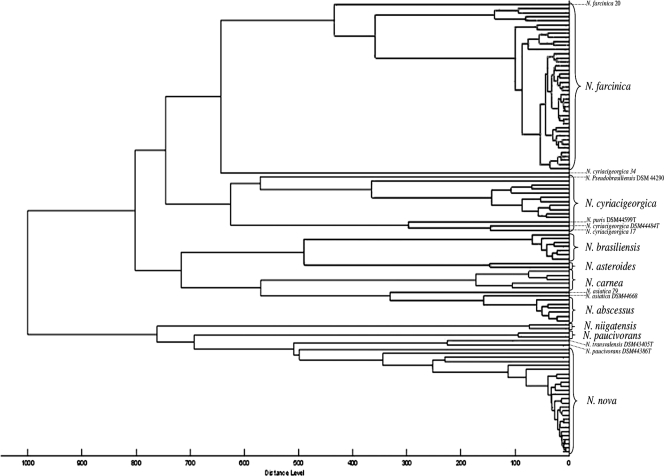

The 110 resulting Nocardia spectra were stored in the Nocardia node of the projects taxonomy tree linked to the MALDI BioTyper taxonomy tree database. The dendrogram generated from the 110 registered Nocardia spectra pointed out distinctive clusters consisting of nocardiae of the same species (Fig. 1). The 41 Nocardia farcinica spectra constituted a first cluster that could potentially be subdivided into two smaller groups and with an additional distinct spectrum of one single strain (N. farcinica 20). A distance level of 450 separated the two most extreme N. farcinica spectra, whereas the subclustering reduced the maximal distance level in both groups to 150. A second cluster regrouped 11 N. cyriacigeorgica spectra despite a high distance level of 650 between the two most distant strains. In fact, two strains of N. cyriacigeorgica were distantly related to the others, namely, N. cyriacigeorgica 17 and reference type strain DSM44484T. All of the spectra of the N. africana, N. elegans, N. nova, and N. veterana strains made up another cluster with a maximum distance level of 500.

FIG. 1.

Dendrogram of 110 Nocardia strains analyzed, including 91 clinical strains and 19 reference strains. Species clustering can be observed. Ten Nocardia strains are annotated on the dendrogram because of the unexpected positioning of their spectra.

The N. abscessus, N. asteroides, N. brasiliensis, N. carnea, and N. niigatensis species, respectively, united all of their recorded spectra into small groups with a maximum distance level below 200 within each group. Eventually, a small group unified two N. paucivorans spectra.

Seven remaining Nocardia spectra were located in clusters assembling the spectra of other species. The spectra of the reference type strains N. pseudobrasiliensis DSM44290T, N. otitidiscaviarum NCTC1934T, and N. puris DSM44599T were found within the N. cyriacigeorgica cluster. Despite the grouping of the two N. asiatica strains (clinical strain N. asiatica 79 and type strain N. asiatica DSM44668T), a distance level of only 350 separated them from the N. abscessus cluster. Finally, the N. transvalensis DSM43405T and N. paucivorans DSM44386T spectra were gathered together.

The spectrum of clinical strain N. cyriacigeorgica 34 had an isolated position in the dendrogram, with a distance level of >600 from the closest Nocardia spectrum.

MALDI-TOF MS identification of Nocardia challenge strains.

Of the 43 acquired blind-coded Nocardia spectra aligned with the MALDI BioTyper database, 19 isolates (44%) were correctly identified, of which 10 (23%) were identified to the species level (log scores, ≥2) and 9 (21%) were identified to the genus level (log scores between <2 and ≥1.7). The remaining 24 isolates (56%) yielded log scores of <1.7 and were thereby considered not identifiable.

Log scores are listed in Table 3. The strains with high log scores were all of N. nova, except one N. brasiliensis isolate that was identified as a Nocardia sp. by the MALDI BioTyper database. Of the nine strains with intermediate scores, five of N. nova and one of N. abscessus were correctly identified to the species level. Likewise despite low log scores, three strains of N. abscessus, five strains of N. farcinica, and one strain of N. cyriacigeorgica were correctly identified to the species level.

TABLE 3.

Best-match identification results of 43 clinical Nocardia isolates with the MALDI BioTyper database alone and enriched with our own Nocardia database

| Log score | Isolate result determined with MALDI BioTyper database |

Isolate result determined with MALDI BioTyper database supplemented with spectra issued from our home-made database |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | No. identified/total |

No. misidentified/total | % | No. identified/total |

No. misidentified/total | |||

| Species level | Genus level | Species level | Genus level | |||||

| ≥2 | 23 | 10/43 | 79 | 34/43 | ||||

| ≥1.7 and <2 | 21 | 7/43 | 2/43 | 9 | 3/43 | 1/43 | ||

| <1.7 | 56 | 9/43 | 15/43 | 12 | 1/43 | 2/43 | 2/43 | |

The addition of our own established Nocardia database to the original database did significantly improve the scores, leading to 38 (88%) correct identifications, of which 34 (79%) were to the species level (log scores of ≥2) and 4 (9%) were to the genus level (log scores between <2 and ≥1.7). Five isolates (12%), including one isolate each of N. abscessus, N. beijingensis, N. brasiliensis, N. carnea, and N. veterana, yielded log scores of <1.7 and thus could not be identified.

DISCUSSION

The identification of Nocardia species has always been considered a long and tedious task in the routine laboratory, and several publications have proposed tools in order to improve, accelerate, and ease the process. For instance, Wauters et al. recently proposed an algorithm including a combination of nine conventional and enzymatic tests for the rapid identification of the most common species (16). This scheme proved to be very efficient and highly discriminating for the accurate identification of more than 95% of the clinical isolates of Nocardia that belong to six different species.

Another identification approach was based on the antimicrobial susceptibility profiles within the genus Nocardia. In 1988, Wallace and Steele delineated six different susceptibility and resistance pattern types within 78 isolates of N. asteroides (14). This study led to the subsequent in-depth evaluation of Nocardia taxonomy by molecular methods that eventually resulted in the creation of distinct Nocardia species associated with described drug patterns (2). Glupczynski et al. consolidated the typical multidrug resistance patterns of five major clinical species, namely, N. farcinica, N. nova, N. cyriacigeorgica, N. abscessus, and N. brasiliensis, by determining MICs against 12 selected antimicrobial agents by Etest (5).

Further on, the expansion of molecular methods has distinctly contributed to the rapid and accurate identification of Nocardia species. PCR amplification of a 999-bp fragment of the 16S rRNA gene and subsequent restriction endonuclease analysis were described by Conville et al. (3), as they observed distinct restriction fragment length polymorphism patterns for all of the former drug pattern types of N. asteroides but not for N. asteroides drug pattern type IV. Another gene target explored for the identification of Nocardia species was the 16S-23S rRNA gene internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region containing different signatures for appropriate interspecies discrimination. Wang et al. (15) recently developed species ITS rRNA gene operon-specific probes enabling the identification of the five emerging pathogenic Nocardia species N. beijingensis, N. blacklockiae, N. thailandica, N. elegans, and N. vinacea. Altogether, it appears, however, that the use of molecular methods nevertheless requires the presence of a highly qualified staff and often sophisticated material specific to each technique.

MALDI-TOF MS has launched a new era in the routine microbiology laboratory. This proteomic method has proved its efficacy for the identification of various microorganisms (11, 13). Several evaluations have been reported for the identification of fastidious, slow-growing organisms such as Gram-negative nonfermenters, yeasts, or mycobacteria known to be difficult to identify by conventional tests in the routine laboratory (8, 9, 13). After establishing a reference database of 248 nonfermenting Gram-negative bacteria, Mellmann et al. analyzed 78 blind-coded clinical nonfermenters and obtained 85.9% correct identifications (8). Recently, van Veen et al. demonstrated the ability of the MALDI-TOF MS method to identify yeasts of clinical interest accurately (13). In a prospective study, 61 clinical yeast isolates belonging to seven different genera were analyzed following extraction. Overall, correct species identification was found for 85% of the microorganisms and only two minor misidentifications (identification correct to the genus but not the species level) were observed.

Regarding the identification of other fastidious microorganisms, a database of 37 Mycobacterium strains representing 13 species was created by Pignone et al. (9) allowing an in-depth analysis and comparison of the different spectra, which led to the conclusion that all of the strains produced reproducible, unique mass spectral profiles. The spectra analyzed arose from the direct deposit of the Mycobacterium strains. In our study, laser bombing of a direct deposit of Nocardia strains led to spectra of very poor quality or even to the absence of any spectra. While creating a new database requires the achievement of optimal spectra, we faced the challenge of obtaining Nocardia spectrum peaks with sufficient intensity. Because of the thickness and hydrophobicity of the Nocardia cell wall, which, like that of mycobacteria, contains a large amount of mycolic acids, pretreatment of the strains was mandatory prior to analysis by MALDI-TOF MS. It rapidly came out that the standard ethanol-formic acid extraction procedure alone was insufficiently efficient to allow the membrane proteins to be ionized by the matrix. A pretreatment that consisted of boiling the Nocardia colonies in 500 μl of distilled water for 30 min led to rupture of the cell wall and thus allowed us to solve this problem. A shorter boiling time of 10 min had no effect, while increasing the time beyond 30 min did not improve the quality of the spectra generated (data not shown). The above issue could also be resolved by plunging the solution of Nocardia colonies three times into liquid nitrogen at −196°C for 5 s. The boiling technique was preferred to the liquid nitrogen freezing method due to the less frequent availability of liquid nitrogen in routine laboratories and to the easier handling of the boiling technique.

A major advantage of MALDI-TOF MS is that it allows the rapid identification of nocardiae from cultured colonies with a very short turnaround time, only 1 h being necessary to perform the entire identification procedure, starting from the boiling procedure, followed by the ethanol-formic acid extraction and the analysis by MALDI-TOF MS of a Nocardia isolate cultured on TSA. Nocardia strains can also be isolated from culture media used for the growth of mycobacteria or fungi. Extraction of colonies of a selection of 10 Nocardia spp. grown on Sabouraud agar and on Löwenstein-Jensen medium yielded identification and score results similar to those obtained with cultures grown on TSA medium (data not shown). The development and establishment of our own Nocardia database expanded the MALDI BioTyper database by 110 Nocardia spectra. A dendrogram (Fig. 1) of those added spectra enabled us to visualize the clustering of spectra in species-specific groups. The 16S rRNA sequence similarity of the species N. africana, N. elegans, N. nova, and N. veterana, which form a species complex, could explain the clustering together of their respective MALDI-TOF spectra (2).

Likewise, the MALDI-TOF MS dendrogram pointed out 10 Nocardia strains because of the unexpected positioning of their individual spectra. Starting from this observation, a panel of rapid biochemical tests developed by Wauters et al. (16) was repeated with those 10 Nocardia strains, including 6 reference type strains (N. asiatica DSM44668T, N. otitidiscaviarum NCTC1934T, N. paucivorans DSM44386T, N. pseudobrasiliensis DSM44290T, N. puris DSM44599T, and N. transvalensis DSM43405T) and 4 clinical strains (N. asiatica 79, N. cyriacigeorgica 17, N. cyriacigeorgica 34, and N. farcinica 20). The results confirmed the identification of all of the strains but clinical strain N. farcinica 20, which displayed a negative γ-glutamyl aminopeptidase test and which also clustered at a large distance from all of the other strains included in the N. farcinica cluster (Fig. 1). Total 16S rRNA gene sequencing was repeated with this last strain, and the isolate was best identified as N. higoensis with 99.5% sequence similarity at the level of the 16S rRNA sequence. Newly described in 2004 by Kageyama et al. (7), N. higoensis was isolated for the first time from a patient with lung nocardiosis in Japan. The reported susceptibility to tobramycin differentiating N. higoensis from N. farcinica strains was also confirmed for this strain (data not shown). The major distance level of 600 separating the N. cyriacigeorgica strain 34 spectrum from the other Nocardia spectra could not be explained, as the strain showed 99.9% 16S rRNA sequence similarity to N. cyriacigeorgica type strain DSM44484T and displayed an antimicrobial susceptibility and resistance profile (resistance to ciprofloxacin and clarithromycin, susceptibility to ceftriaxone, imipenem, and tobramycin) matching the N. cyriacigeorgica drug resistance pattern.

Another interesting observation was that the N. asiatica DSM44668T and N. asiatica 79 spectra clustered quite closely with the N. abscessus cluster at a distance level of 350. Newly described in 2004 by Kageyama et al. (6), N. asiatica has a significant 16S rRNA sequence divergence from N. abscessus, while only two biochemical tests (nitrate reduction and esculin decomposition) could distinguish the two species. Moreover, the rapid Nocardia species identification tests proposed by Wauters et al. (16) yielded the same phenotypic results for both species.

The N. cyriacigeorgica cluster was divided into two groups, with the first group formed by the clinical strain N. cyriacigeorgica 17 and reference type strain N. cyriacigeorgica DSM44484T separated from the other strains with a distance level of 600. These two strains were furthermore joined by reference strain N. puris DSM44599T. The second group included nine N. cyriacigeorgica clinical strains, as well as reference type strain N. pseudobrasiliensis DSM44290T. Biochemical tests and antimicrobial susceptibility testing could not differentiate between the two N. cyriacigeorgica groups. Interestingly Roth et al. (10) also observed a microheterogeneity in the sequence of the 16S rRNA gene (sequence divergence of fewer than five bases) in several Nocardia species. This observation might account for the subclustering of the N. cyriacigeorgica group and the N. nova group observed in the MALDI-TOF MS dendrogram. Furthermore, the analysis of sequence similarities of the 16S rRNA genes of the species N. puris and N. pseudobrasiliensis with that of the N. cyriacigeorgica strain through the phylogenetic tree developed by Roth et al. (10) was inconclusive. Poor 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity between N. paucivorans and N. transvalensis was also observed, despite their close relatedness in the MALDI-TOF MS dendrogram. It should, however, be stressed that several species were insufficiently represented in our study, with only a single strain each being available for N. puris, N. pseudobrasiliensis, and N. transvalensis. Hence, an evaluation with a larger number of strains of those species is clearly necessary to confirm or reject the latter dendrogram observations.

It should be stressed that the original database included in the MALDI BioTyper software version 3.0.2 contains 36 Nocardia spectra accounting for 29 different species. Of note, the species that are most frequently isolated from clinical specimens were represented by, at most, two different spectra. The broadening of this database with our own Nocardia database, including a large panel of Nocardia isolates from clinical specimens and reference strains, was intended to improve the accuracy of the database for the identification of Nocardia spp. In fact, the failure of MALDI-TOF MS to reach identification is most often explained by an insufficient coverage of organisms by the database. For instance, Seng et al. (11) pointed out the gap in non-Clostridium anaerobe identification as no or only very few reference spectra were included for these organisms in the Bruker database. The same authors also showed that the inclusion of additional spectra and broadening of the database could solve this problem. On the other hand, misidentification with a log score value of ≥1.7 can rarely be resolved by expansion of the database. First reported by Seng et al. (11), two recent studies confirmed that nearly 50% of the Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates tested were misidentified as Streptococcus parasanguinis and that incorporation of additional spectra of those species into the database did not solve the problem (4, 13).

In this study, we were confronted with a lack of identification by MALDI-TOF MS and we could clearly confirm the benefit of an extended database, since correct identification to the species level with a score of ≥2 increased from 44% to 88% when our own Nocardia database was added to the original database of the manufacturer. Likewise, our created database essentially comprised Nocardia species most frequently found in human clinical specimens. The absence of identification (scores of <1.7) with the MALDI BioTyper database involved 24 strains belonging to seven species, including strains of major clinical significance, namely, N. abscessus, N. cyriacigeorgica, and N. farcinica. Among the three Nocardia strains that could only be identified to the genus level despite the addition of our own database, the N. shimofusensis and N. beijingensis strains were not represented in the databases and were subsequently added. One N. brasiliensis and one N. carnea strain each were misidentified despite their inclusion in both databases but with scores of <1.7 (Table 2).

Repeating the MALDI-TOF MS analysis with triple deposits of the same Nocardia culture isolate did not lead to better identification scores than using a single deposit (data not shown).

Notwithstanding the database, all of the results with scores of ≥2 yielded correct identification to the species level and results proved at least correct to the genus level for scores of ≥1.7 and <2. Consequently, misidentification was always associated with a low score of <1.7. In conclusion, the added Nocardia database clearly improves identification to the species level. We therefore recommend MALDI-TOF MS for rapid and accurate identification of the most commonly encountered Nocardia sp. isolates after pretreatment by 30 min of boiling and ethanol-formic acid extraction of the organism. Further expansion of the database with a larger number of isolates including the less common recently described Nocardia species is also clearly warranted.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by EU grant FP7-HEALTH-2009-SINGLE-STAGE TEMPOtest-QC, project 241742.

We have no conflicts of interest to report.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 September 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambrosioni, J., D. Lew, and J. Garbino. 2010. Nocardiosis: updated clinical review and experience at a tertiary center. Infection 38:89-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown-Elliott, B. A., J. M. Brown, P. S. Conville, and R. J. Wallace, Jr. 2006. Clinical and laboratory features of the Nocardia spp. based on current molecular taxonomy. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19:259-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conville, P. S., S. H. Fischer, C. P. Cartwright, and F. G. Witebsky. 2000. Identification of Nocardia species by restriction endonuclease analysis of an amplified portion of the 16S rRNA gene. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:158-164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Bel, A., I. Wybo, D. Pierard, and S. Lauwers. 2010. Correct implementation of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry in routine clinical microbiology. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:1991-1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glupczynski, Y., C. Berhin, M. Janssens, and J. Wauters. 2006. Determination of antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of Nocardia spp. from clinical specimens by Etest. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 12:905-912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kageyama, A., N. Poonwan, K. Yazawa, Y. Mikami, and K. Nishmura. 2004. Nocardia asiatica sp. nov., isolated from patients with nocardiosis in Japan and clinical specimens from Thailand. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54:125-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kageyama, A., K. Yazawa, A. Mukai, M. Kinoshita, N. Takata, K. Nishmura, R. M. Kroppenstedt, and Y. Mikami. 2004. Nocardia shimofusensis sp. nov., isolated from soil, and Nocardia higoensis sp. nov., isolated from a patient with lung nocardiosis in Japan. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54:1927-1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mellmann, A., J. Cloud, T. Maier, U. Keckvoet, I. Ramminger, P. Iwen, J. Dunn, G. Hall, D. Wilson, P. Lasala, M. Kostrzewa, and D. Harmsen. 2008. Evaluation of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry in comparison to 16S rRNA gene sequencing species identification of nonfermenting bacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:1946-1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pignone, M., K. M. Greth, J. Cooper, D. Emerson, and J. Tang. 2006. Identification of mycobacteria by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:1963-1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roth, A., S. Andrees, M. Kroppenstedt, D. Harmsen, and H. Mauch. 2003. Phylogeny of the genus Nocardia based on reassessed 16S rRNA gene sequences reveals underspeciation and division of strains classified as Nocardia asteroides into three established species and two unnamed taxons. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:851-856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seng, P., M. Drancourt, F. Gouriet, B. La Scola, P. E. Fournier, J. M. Rolain, and D. Raoult. 2009. Ongoing revolution in bacteriology: routine identification of bacteria by matrix-assisted laser desorption time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Clin. Infect. Dis. 49:543-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spanu, T., E. De Carolis, B. Fiori, M. Sanguinetti, T. D'Inzeo, G. Fadda, and B. Posteraro. 2 February 2010, posting date. Evaluation of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry in comparison to rpoB gene sequencing for species identification of bloodstream infection staphylococcal isolates. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. [Epub ahead of print.] doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03181.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.van Veen, S. Q., E. C. J. Claas, and E. J. Kuijper. 2010. High-throughput identification of bacteria and yeast by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry in conventional medical microbiology laboratories. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:900-907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallace, R. J., Jr., and L. C. Steele. 1988. Susceptibility testing of Nocardia species for the clinical laboratory. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 9:155-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang, X., M. Xiao, F. Kong, V. Sintchenko, H. Wang, B. Wang, S. Lian, T. Sorrell, and S. Chen. 2010. Reverse line blot hybridization and DNA sequence studies of the 16S-23S rRNA gene intergenic spacer regions of five emerging pathogenic Nocardia species. J. Med. Microbiol. 59:548-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wauters, G., V. Avesani, J. Charlier, M. Janssens, M. Vaneechoutte, and M. Delmée. 2005. Distribution of Nocardia species in clinical samples and their rapid identification in the routine laboratory. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:2624-2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]