Abstract

A total of 20 Vibrio cholerae isolates were recovered for investigation from a cholera outbreak in Kelantan, Malaysia, that occurred between November and December 2009. All isolates were biochemically characterized as V. cholerae serogroup O1 Ogawa of the El Tor biotype. They were found to be resistant to multiple antibiotics, including tetracycline, erythromycin, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, streptomycin, penicillin G, and polymyxin B, with 35% of the isolates being resistant to ampicillin. All isolates were sensitive to ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin, chloramphenicol, gentamicin, and kanamycin. Multiplex PCR analysis confirmed the biochemical identification and revealed the presence of virulence genes, viz., ace, zot, and ctxA, in all of the isolates. Interestingly, the sequencing of the ctxB gene showed that the outbreak strain harbored the classical cholera toxin gene and therefore belongs to the newly assigned El Tor variant biotype. Clonal analysis by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis demonstrated that a single clone of a V. cholerae strain was responsible for this outbreak. Thus, we present the first molecular evidence that the toxigenic V. cholerae O1 El Tor variant has invaded Malaysia, highlighting the need for continuous monitoring to facilitate early interventions against any potential epidemic by this biotype.

Vibrio cholerae strains belonging to the O1 and O139 serogroups are agents of endemic and pandemic cholera, a potentially life-threatening diarrheal disease. As a water- and food-borne disease, cholera infection is linked to poverty and poor sanitation in many developing countries (13). From an epidemiological point of view, cholera tends to occur in explosive outbreaks throughout several regions simultaneously; likewise, extensive pandemics have followed a progressive pattern, affecting many countries across the continents and extending over many years (17). Cholera pandemics long have been believed to be exclusively associated with the toxigenic V. cholerae O1 serogroup, which consists of two biotypes: classical and El Tor. The classical biotype was responsible for the world's first six pandemics, but the seventh pandemic was caused by the O1 El Tor biotype and was exceedingly more extensive in geographic spread and duration (13).

The first non-O1 strain recognized as having caused an explosive cholera epidemic was discovered in 1992, but it did not belong to any of the 138 serogroups previously described. Thus, the new epidemic strain was designated serogroup O139 and subsequently has been linked to extensive outbreaks in various regions of Bangladesh and India (14). The discovery of its ability to cause large outbreaks and rapid spread to neighboring countries suggested the possibility that the new serogroup will facilitate the eighth pandemic of cholera if outbreaks continue to occur and more countries are affected (42). The strains of V. cholerae O1 El Tor in the seventh pandemic experienced an initial displacement by O139 strains in the Indian subcontinent (1) but recovered their prominence within a year and established a coexistence with O139 strains, causing subsequent cholera outbreaks throughout India and Bangladesh (12, 27).

In Malaysia, cholera caused by V. cholerae O1 El Tor is endemic and often has been associated with sporadic outbreaks (24, 33, 46). El Tor is one of the most established biotypes within the V. cholerae O1 serogroup and is differentiated from the classical biotype based on a number of phenotypic traits, such as polymyxin B susceptibility, chicken cell agglutination, Voges-proskauer (VP) test positivity, and phage susceptibility (17). In addition, comparative genomic analysis has revealed the presence of genes that are unique to the El Tor biotype (11). Some of these genes, including the major toxin-coregulated pilus (TCP) tcpA (19) and rtxC of the repeat in toxin (RTX) cluster, have since been used as genetic markers for the identification of El Tor strains (8). The classical and El Tor biotypes also differ in the infection pattern of disease they elicit; the El Tor strains have a higher ratio of asymptomatic carriers (37), survive better in the environment and human host, and are more efficiently transmitted from host to host (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bookshelf/br.fegi?book=mmed&part=A1358).

The public health significance of a V. cholerae isolate is routinely assessed by two critical properties: the production of cholera toxin (CT) and the possession of either the O1 or O139 antigen, which acts as a marker of epidemic potential (17). So far, agents of endemic and pandemic cholera have been represented exclusively by CT-producing V. cholerae strains. CT has been shown to be the key virulence factor responsible for the manifestation of massive, dehydrating diarrhea (21). Although CTs from classical and El Tor strains are structurally and functionally similar, differences in immunological and genetic attributes have enabled several methods to differentiate between the two biotypes. Specifically, the molecular techniques include the direct sequencing of the ctxB gene (30), a ganglioside GM1 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (GM1-ELISA) with specific monoclonal antibody to classical or El Tor CT (29), and a mismatch amplification mutation assay (MAMA) PCR to detect polymorphism at nucleotide position 203 in the ctxB genes (26).

In the study presented here, we performed the genetic analysis and molecular typing of V. cholerae O1 isolated from patients during a cholera outbreak in Kelantan, Malaysia, that occurred between November and December 2009. The existence of an outbreak was established based on the region's previous incidence rate of cholera, which was reported to be 0.0 per 100,000 for four consecutive years (2005 to 2008) (http://statistics.gov.my). The duration of the outbreak was only 21 days, and 33 cholera cases were confirmed. Among those 33, 21 victims were local Kelantanese and the remaining 12 were migrant Thai workers. The patient demographic data revealed that six different districts were involved, and the patients ranged widely in age. Isolates recovered from symptomatic patients were characterized for their antimicrobial susceptibility patterns, the presence of various toxigenic and pathogenic genes, the production of cholera toxin, the nucleotide sequence of cholera toxin B subunits, and the demonstration of the clonal relationships between these isolates. The ultimate findings from this research have provided important insights into the causative agent of the recent cholera outbreak in peninsular Malaysia.

(This study was presented in part at the 2nd National Conference on Environment and Health, Kota Bharu, Kelantan, Malaysia, 17 to 18 March 2010.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

A total of 20 V. cholerae isolates were recovered from different infected patients (11 Kelantanese and 9 Thais) hospitalized in Kelantan during the cholera outbreak period. Thiosulfate-citrate-bile salt-sucrose (TCBS) agar was used to isolate the V. cholerae from stool samples or rectal swabs after enrichment in alkaline peptone water for 6 h. Suspected V. cholerae colonies were identified using standard biochemical methods (18), and serotyping was performed by slide agglutination tests with polyvalent O1 and monospecific Ogawa and Inaba antisera (Denka Seiken, Tokyo, Japan). All V. cholerae isolates were biotyped using the VP test and by susceptibility to polymyxin B (50 U). The isolates were stored in Luria broth supplemented with 15% (vol/vol) glycerol. In addition, a V. cholerae O1 isolate from an environmental water source and two representatives of the V. cholerae O1 outbreak strain isolated in 2000 during the last cholera outbreak in Kelantan were obtained for epidemiological study and comparative purposes.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

The clinical isolates were tested for their susceptibility to 10 different antibiotic-impregnated commercial disks (Oxoid, Hampshire, United Kingdom) on Mueller-Hinton agar by using the disk diffusion method (3). The antibiotic disks were used at the following concentrations: ampicillin (10 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), erythromycin (15 μg), norfloxacin (10 μg), sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (25 μg), tetracycline (30 μg), chloramphenicol (30 μg), streptomycin (10 μg), kanamycin (30 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), and penicillin G (10 U). Isolates were recorded as susceptible, intermediate, or resistant according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (9).

Multiplex PCR.

A multiplex PCR-based assay was performed for each isolate to detect the presence of hemM, rfbO139, ctxA, tcpA, ace, zot, and tetA(A) genes using the primers listed in Table 1 (22) and thermocycling conditions described previously (10), with some modifications. Bacterial cell lysate was prepared by the boiling lysis method for use as the DNA template. The PCR amplification was carried out in a 20-μl reaction mixture containing 1× PCR buffer, 250 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), 4 mM MgCl2, 1 U Taq DNA polymerase (Fermentas, Vilniuas, Lithuania), various concentration of primer pairs (forward [F] and reverse [R]; Table 1), 1 μl of internal control DNA template, 2 μl of DNA template, and deionized water. A pair of primers, SSP2 (F) and SSP2 (R), was included in each reaction mixture to serve as the internal control for ruling out false-negative results. The thermocycling conditions were programmed in a Mastercycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) as follows: an initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. PCR amplicons were electrophoresed in 2% agarose containing ethidium bromide and visualized using a ChemiImage analyzer (Alpha Innotech, CA).

TABLE 1.

PCR primers used in this study

| Gene targeta | Nucleotide sequence (5′ to 3′) | Amplicon size (bp) | Primer concn per reaction (pmol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SSP2 (F) | TCTTGTAGGTTGTCATCCATC | 150 | 6.0 |

| SSP2 (R) | GACCATTCGTCCCAAACACCA | 150 | 6.0 |

| ace (F) | TGGCTAATTGATGGCTTTACGTG | 205 | 2.4 |

| ace (R) | GCGCTTGGTCTAACCCTAAAAAG | 205 | 2.4 |

| zot (F) | AGGCGGTTGCTCCTGCGTCTTTT | 245 | 2.4 |

| zot (R) | CGGTAACGGTAGCACCTTGTAG | 245 | 2.4 |

| ctx (F) | AACTCAGACGGGATTTGTTAGGC | 300 | 1.2 |

| ctx (R) | TCTCTGTAGCCCCTATTACGATGT | 300 | 1.2 |

| rfbO139 (F) | CGTTATAGGTATCATCAAGAGAG | 352 | 12.0 |

| rfbO139 (R) | CAAATATCTTTAGATAACTCAGA | 352 | 12.0 |

| tcpA-El (F) | ATTGCAATGACACAAACTTATCGTA | 401 | 3.2 |

| tcpA-El (R) | TAGTTAGGTTTAAGTTGGCACTTC | 401 | 3.2 |

| hemM (F) | TGGGAGCAGCGTCCATTGTG | 519 | 4.8 |

| hemM (R) | CAATCACACCAAGTCACTC | 519 | 4.8 |

| tcpA-Cla (F) | CGAAGTGATCATCGTTCTAGGC | 581 | 4.0 |

| tcpA-Cla (R) | AGCTGTTACCAAATGCAACGCC | 581 | 4.0 |

| tetA (F) | ATATCACTGATGGCGATGAGCG | 700 | 8.0 |

| tetA (R) | AAGAGGAGGGGTCCGACGAT | 700 | 8.0 |

Cla, classical; El, El Tor. Primer data are from reference 22.

CT production.

The production of cholera toxin (CT) was detected by using the GM1-ELISA method (41). Briefly, V. cholerae cultures were grown in AKI medium at 37°C overnight (15). Cell-free culture supernatants (100 μl) were added to separate wells in a GM1-coated microtitration plate and allowed to incubate at room temperature for 1 h. CT bound to GM1 was detected with rabbit anti-CT serum (Sigma-Aldrich, MO) followed by anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (Ig)-peroxidase conjugate (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). The plate was developed with ABTS (2,2′-azino-di[3-ethyl benzthiazoline sulfate]) solution, and absorbance was recorded at 405 nm with reference to 495 nm using a VERSAmax microplate reader (Molecular Devices, CA). The experiment was performed in duplicate, and optical densities of 0.4 or more above the background level in the ELISA were considered positive.

ctxB gene sequencing.

The ctxB gene was amplified from the isolates by using the previously described forward primer, ctx7 (5′-GGTTGCTTCTCATCATCGAACCAC-3′) (30), and a reverse primer, ctx-seqR (5′-GAAGAGCCGTGGATTCATCATGC-3′), which was designed in this study. PCR amplification of the ctxB gene was performed in a 20-μl reaction mixture containing 1× PCR buffer, 160 μM dNTPs, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.75 U Taq DNA polymerase (Fermentas), 10 pmol of each primer, and 2 μl of DNA template. The thermocycling conditions were performed as described above for the multiplex PCR, with the exception that the annealing step was performed at 55°C. The PCR amplicons were purified using a Wizard SV gel and PCR cleanup system (Promega, WI) and sequenced by First Base Laboratories Sdn. Bhd. (Selangor, Malaysia). The deduced amino acid sequences of the representative outbreak strain were aligned with corresponding sequences from the El Tor strain N16961 (GenBank accession number NC-002505) and the classical strain O395 (GenBank accession number CP001235) by using the ClustalW program.

PFGE.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed according to the PulseNet standardized protocol for Escherichia coli subtyping (6), with minor modifications. In brief, an isolated colony from an individual V. cholerae strain was streaked onto Columbia agar with 5% horse blood and incubated at 37°C for 16 h. Bacterial cells were embedded in 2% low-melting-point agarose (Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA) and lysed with lysis buffer (1% Sarkosyl in 0.5 M EDTA [pH 8.0] containing proteinase K). The agarose plugs obtained were digested with 10 U of restriction endonuclease NotI (Promega) at 37°C for 4 h. The plugs were loaded into a 1% agarose gel in 0.5% Tris-borate-EDTA buffer and electrophoresed at 14°C using a CHEF-DRIII apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The pulse time ranged from 4 to 8 s for 9 h and from 8 to 25 s for 11 h, both at 6 V/cm. The lambda ladder PFG marker (New England Biolabs, Frankfurt, Germany) was used as the molecular mass standard. The ethidium bromide-stained gel was visualized and captured using a ChemiImage analyzer (Alpha Innotech), by which the digital images were stored as TIFF files for subsequent analysis with FPQuest software, version 4.5 (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The similarity analysis of the profiles was performed using the Dice coefficient (position tolerance, 1.0%), and the dendrogram was constructed using UPGMA (unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic averages).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The complete coding sequences of the ctxB gene for the representative outbreak strains were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers HM143769, HM143770, HM143771, HM143772, HM143773, HM143774, and HM143775.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

All 20 clinical isolates recovered during the cholera outbreak in Kelantan produced characteristic biochemical reactions of V. cholerae and were serologically identified as being of the O1 Ogawa serotype. Furthermore, these isolates were determined to be of the El Tor biotype, as evidenced by their positivity in the VP test and resistance to polymyxin B.

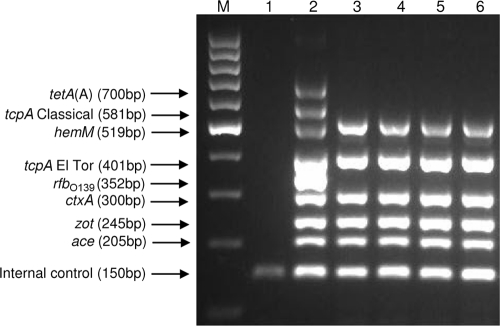

The clinical isolates also were analyzed by means of a multiplex PCR assay (22) to simultaneously determine the serogroups and biotypes and to detect the toxigenic potential by the amplification of virulence genes (ace, zot, and ctxA) and the tetracycline resistance gene tetA(A). The hemM (lolB) gene was used to confirm the biochemical identification of V. cholerae (Fig. 1), since it is known to be highly conserved among all serogroups and biotypes of V. cholerae (20). The multiplex PCR also facilitated the analysis of the differences in DNA sequence of the tcpA gene, which was used to biotype the isolates. The biotyping results based on phenotypic traits were supported by the presence of tcpA gene of the El Tor type. The detection of the tcpA gene was significant as this gene encodes for a TCP which is essential for transmission of cholera toxin phage (CTXΦ) and colonization of the bacterium in the small intestine (13).

FIG. 1.

Agarose electrophoresis products from the multiplex PCR. Amplified fragments of particular genes are indicated on the far left. Lane M, 100-bp DNA ladder; lane 1, negative control; lane 2, positive control; lane 3, isolate 03/09KB; lane 4, isolate 11/09KB; lane 5, isolate 29/09KB; lane 6, isolate 33/09KB.

The integration of CTXΦ into the chromosome of V. cholerae has been shown to confer toxigenicity to the strain since major virulence factors are encoded in the genome of the lysogenic filamentous phage. The pathogenesis of cholera is believed to be a result of synergistic actions involving a number of genes, which are mainly located in the CTX element and the TCP pathogenicity island (13). Genes encoding the CT, accessory cholera toxin (ace), and zonula occludens toxins (zot) are localized to a 4.5-kb DNA segment that forms the core region of the CTX genetic element (45). Therefore, we performed multiplex PCR assays to simultaneously detect the CT and other ancillary toxin genes to confirm the presence of CTX prophage in all of the isolates. Thus, we were able to identify the toxigenic V. cholerae O1 El Tor strain as the causative agent of the 2009 Kelantan cholera outbreak in a single reaction step. The toxigenicity of all of the clinical isolates was further demonstrated by using the ganglioside GM1-specific ELISA to detect the in vitro expression of CT.

The results from an antimicrobial susceptibility test (AST) are shown in Table 2. All isolates were found to be resistant to tetracycline, erythromycin, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, streptomycin, and penicillin G. In addition to these five antimicrobial agents, all of the isolates also exhibited resistance to polymyxin B, another typical feature of the El Tor biotype. Among the 20 isolates examined, 35% were resistant to ampicillin. Susceptibility to ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin, chloramphenicol, gentamicin, and kanamycin was observed in all of the isolates.

TABLE 2.

Antibiotic resistance of V. cholerae O1 El Tor variants isolated between November and December 2009 during a cholera outbreak in Kelantan, Malaysia

| Antibiotype | Antimicrobial resistance patterna | No. of isolates (%) |

|---|---|---|

| I | ERY SXT TET STR PEN PMB | 13 (65) |

| II | AMP ERY SXT TET STR PEN PMB | 7 (35) |

AMP, ampicillin; ERY, erythromycin; SXT, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim; TET, tetracycline; STR, streptomycin; PEN, penicillin G; PMB, polymyxin B.

Antibiotics represent an important adjunct therapy for cholera, as they effectively reduce the duration of diarrhea and amount of V. cholerae in the excretions (23). In Malaysia, tetracycline generally is used to treat severe cholera, but the emergence of tetracycline-resistant strains in Kelantan instigated a review of its efficacy (34). The retrospective analysis of outbreak isolates indicated that full sensitivity to tetracycline was present in 1992 and 1994. In 1993 only 8.9% of outbreak isolates were resistant to tetracycline, but that amount increased almost 4-fold in 1998, when 33.3% of isolates exhibited resistance to the drug, with another 54.2% retaining only moderate sensitivity (34). Our AST of the recent Kelantan strains revealed that the current cholera outbreak involved isolates that were fully resistant to tetracycline. Although none of the isolates were found to express the tetA(A) gene by multiplex PCR assay, the tetracycline-resistant phenotype of these isolates could have been conferred by other tetracycline resistance determinant classes, such as class B, C, D, and E, that can be found among members of Vibrio species (40).

In 1998, erythromycin replaced tetracycline as the first-line drug used in Kelantan for the management of cholera; unfortunately, the therapeutic property of the drug was undermined by the emergence of a new strain that encoded resistance to erythromycin. Since then, the sensitivity rate to ampicillin also dropped, from 87.5% in 1998 to 65% in 2009. The emergence of multidrug-resistant strains associated with large-scale treatment and prophylaxis of cholera with antibiotics (34, 44), along with the horizontal dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes between bacteria (4), has presented a global public health concern, because prolonged hospitalizations and the need for more specialized drugs ultimately will increase the economic burden of cholera. The early control of outbreaks will require an established surveillance system to track the fluctuations in drug resistance patterns of V. cholerae isolates. It is important that the wider global community also plays a role in curtailing indiscriminant prescribing practices to maintain the life-saving capacity of antimicrobials for future generations.

Heterogenicity within the cholera toxin B subunit enables V. cholerae O1 strains to be classified into three genotypes based on amino acid substitutions present at positions 39, 46, and/or 68 (32). According to this approach, all classical strains, as well as the particular El Tor strains from the Gulf Coast of the United States, are characterized as genotype 1. Genotype 2, however, is associated with the El Tor strains from the Australian environmental reservoir, while genotype 3 corresponds to the El Tor strains of the seventh pandemic and the Latin American epidemic strains (30).

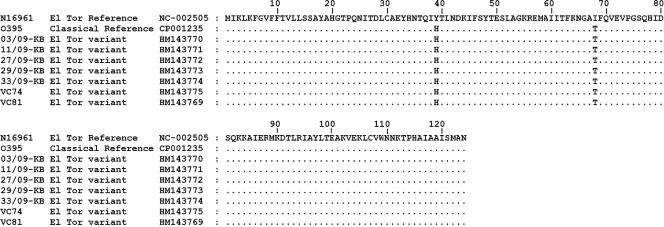

In the study presented here, the sequences of the ctxB gene from representative Kelantan outbreak strains were translated into their amino acid constituents for comparison to the reference classical strain O395 and El Tor strain N16961. The deduced amino acid sequence of the representative strains showed 100% homology to the classical strain O395, which is characterized as genotype 1 and has the amino acid substitution of histidine at position 39, phenylalanine at position 46, and threonine at position 68 (Fig. 2). Those strains that appear to have conventional phenotypic traits of the El Tor biotype but produce the classical-type CT are designated El Tor variants, in accordance with the new scheme for the biotyping of V. cholerae O1 (35).

FIG. 2.

Amino acid sequence alignment of cholera toxin B subunit of representative V. cholerae O1 El Tor variant isolates from the 2000 and 2009 cholera outbreak in Kelantan with the classical (O395) and El Tor (N16961) reference strains. Identical amino acid residues are indicated by dots.

El Tor strains producing cholera toxin of the classical type are not necessarily novel; the U.S. Gulf Coast clone was found to belong to the same genotype. Moreover, such strains were responsible for a cholera outbreak in Bangladesh (28) and have been detected in India (36), Japan, Hong Kong, China, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam (39). Our findings based on Malaysia isolates have provided further evidence that the El Tor strains harboring a classical CT gene are spreading throughout other yet-unreported Asian countries. Since the change between these variants is based on the genome, it was impossible to differentiate the El Tor strains from one another by using the standard bacteriological methods; as such, this variant may have been present but previously was undetected in Malaysia. In fact, the last cholera outbreak in Kelantan in 2000 was caused by an El Tor variant strain, and a comprehensive retrospective analysis of V. cholerae O1 clinical isolates would be required to determine whether the El Tor variants now have completely replaced the El Tor type in Malaysia. This has indeed been the case in the neighboring regions of Kolkata, India (36), and Bangladesh (29).

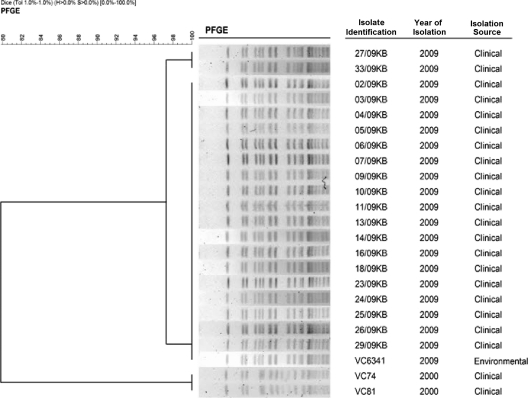

Advances in molecular techniques, such as multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (7), restriction fragment length polymorphism (48), ribotyping (31), and PFGE (24), have enabled individual strains of V. cholerae to be differentially classified beyond their phenotypic traits. Among the techniques, PFGE appears to be superior in terms of its discriminatory power; the analysis covers the entire genome, unlike the ribotyping technique that is only able to detect polymorphism(s) within a specific gene cluster (24). The stable and reproducible banding patterns of PFGE, which result from genomic DNA digestion with the restriction enzyme NotI, was proven to be highly discriminatory (5, 16, 25).

Periodic cholera outbreaks in Malaysia have been shown to be caused by a single clone or very closely related clones with similar PFGE profiles. Throughout the year, sporadic cases that arose were attributed to multiple clones of V. cholerae O1. The heterogeneity at the DNA level among isolates from areas in which cholera is endemic has enabled this technique to differentiate outbreak strains from sporadic cases, as evidenced by differences in their PFGE profiles (24). In this study, the PFGE analysis of the NotI-digested genomic DNA revealed that 16 to 19 fragments had been produced, ranging in size from 46 to 398 kb (Fig. 3). By using FPQuest software, version 4.5, 90% of the clinical isolates were indistinguishable by PFGE; this predominant pattern was designated type A. The remaining two isolates (27/09KB and 33/09KB) differed by an additional band of ∼95 kb and were designated type A1. These two were known to share 97.3% similarity with the outbreak strain and, thus, were considered to be closely related to the outbreak (43, 47).

FIG. 3.

PFGE banding patterns of NotI-digested total cellular DNA from V. cholerae O1 strains. The dendrogram was constructed by UPGMA (unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic averages) clustal analysis using FPQuest software, version 4.5.

In early November of 2009, initial cholera cases were reported among a group of Thai national fishermen working in the Pasir Puteh district. PFGE analysis of a V. cholerae O1 El Tor strain (VC6341) isolated from a drinking water reservoir in the ship where they worked showed patterns indistinguishable from that of their own samples. In such scenarios, the PFGE technique supplemented with epidemiological data can act as a critical tool for outbreak investigation by linking the source of the outbreak and the victims. Although we were successful in identifying the source of the outbreak among the fishermen, other environmental samples collected by the public health agencies from multiple bodies of water in the affected Kelantan districts did not yield any further V. cholerae O1 strains.

As both current and previous outbreaks have been caused by the El Tor variant, we believed it was of interest to determine whether these two outbreaks were caused by the same strain of V. cholerae. The differences among the PFGE profiles of the two representative isolates (VC74 and VC81) from the 2000 cholera outbreak and the current outbreak strain were more apparent, having similarity of 79.9%. The outbreak strains possibly are related; moderate variations in the banding patterns can be attributed to genetic events that might have taken place during the 9-year gap between the times they were isolated. Overall, the typing analysis suggests that a single clone was responsible for the Kelantan cholera outbreak and that this clone may be genetically related to the strain that caused the previous outbreak in the state.

Besides El Tor variants, El Tor hybrids have been described as well. These hybrids include the Matlab variant, which has a combination of traits from both classical and El Tor biotypes (38), and the Mozambique variants, which have a typical El Tor genome but harbor the classical CTXΦ (2). The dissemination of El Tor variants and hybrids could be indicative of the emergence of a more efficient and optimized form of El Tor. As these strains are equipped with all of the genetic features required to initiate a pandemic spread, the global community must acknowledge their potential (28). Although the pathogenicity of the El Tor variant is not fully understood, the genesis of these strains could be driven by selective pressure to survive, since the more-severe nature of cholera caused by the classical biotype increases the likelihood of finding another host, whereas the El Tor biotype can adapt better both in the environment and human host (39).

The return of cholera in Kelantan after almost a decade of absence, coupled with the first detection of an El Tor variant strain, necessitates the establishment of surveillance strategies for such strains. We cannot ignore the potential of these new strains to become epidemiologically dominant.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by USM-Cuba diagnostic grant 304/CIPPM/6150081N106 and USM-Cuba vaccine grant 304/PPSP/6150080N106. This research is supported by the Institute for Postgraduate Studies (IPS) of Universiti Sains Malaysia through the USM Fellowship Scheme awarded to G.Y.A. and C.Y.Y.

We gratefully acknowledge the Food Quality Control Laboratory in Kelantan for providing the environmental V. cholerae isolate used in this study.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 September 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albert, M. J., A. K. Siddique, M. S. Islam, A. S. Faruque, M. Ansaruzzaman, S. M. Faruque, and R. B. Sack. 1993. Large outbreak of clinical cholera due to Vibrio cholerae non-O1 in Bangladesh. Lancet 341:704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ansaruzzaman, M., N. A. Bhuiyan, B. G. Nair, D. A. Sack, M. Lucas, J. L. Deen, J. Ampuero, and C. L. Chaignat. 2004. Cholera in Mozambique, variant of Vibrio cholerae. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10:2057-2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer, A. W., W. M. Kirby, J. C. Sherris, and M. Turck. 1966. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disk method. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 45:493-496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beaber, J. W., B. Hochhut, and M. K. Waldor. 2002. Genomic and functional analyses of SXT, an integrating antibiotic resistance gene transfer element derived from Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 184:4259-4269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cameron, D. N., F. M. Khambaty, I. K. Wachsmuth, R. V. Tauxe, and T. J. Barrett. 1994. Molecular characterization of Vibrio cholerae O1 strains by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:1685-1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Center for Diseases Control and Prevention. 2000. Standardized molecular subtyping of food-borne bacterial pathogen by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA.

- 7.Chen, F., G. M. Evins, W. L. Cook, R. Almeida, N. Hargrett-Bean, and K. Wachsmuth. 1991. Genetic diversity among toxigenic and nontoxigenic Vibrio cholerae O1 isolated from the Western Hemisphere. Epidemiol. Infect. 107:225-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chow, K. H., T. K. Ng, K. Y. Yuen, and W. C. Yam. 2001. Detection of RTX toxin gene in Vibrio cholerae by PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2594-2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2005. Performance standards for antimicrobial testing. 15th informational supplement M100-S15. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 10.Deris, Z. Z., V. M. Leow, M. N. Wan Hassan, A. Z. Nik Lah, S. Y. Lee, H. Siti Hawa, H. Siti Asma, and M. Ravichandran. 2009. Non-O1, non-O139 Vibrio cholerae bacteraemia in splenectomised thalassaemic patient from Malaysia. Trop. Biomed. 26:320-325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dziejman, M., E. Balon, D. Boyd, C. M. Fraser, J. F. Heidelberg, and J. J. Mekalanos. 2002. Comparative genomic analysis of Vibrio cholerae: genes that correlate with cholera endemic and pandemic disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:1556-1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faruque, S. M., K. M. Ahmed, A. K. Siddique, K. Zaman, A. R. Alim, and M. J. Albert. 1997. Molecular analysis of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae O139 Bengal strains isolated in Bangladesh between 1993 and 1996: evidence for emergence of a new clone of the Bengal vibrios. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2299-2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faruque, S. M., M. J. Albert, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1998. Epidemiology, genetics, and ecology of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1301-1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faruque, S. M., D. A. Sack, R. B. Sack, R. R. Colwell, Y. Takeda, and G. B. Nair. 2003. Emergence and evolution of Vibrio cholerae O139. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:1304-1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iwanaga, M., and K. Yamamoto. 1985. New medium for the production of cholera toxin by Vibrio cholerae O1 biotype El Tor. J. Clin. Microbiol. 22:405-408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kam, K. M., C. K. Luey, Y. M. Tsang, C. P. Law, M. Y. Chu, T. L. Cheung, and A. W. Chiu. 2003. Molecular subtyping of Vibrio cholerae O1 and O139 by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis in Hong Kong: correlation with epidemiological events from 1994 to 2002. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4502-4511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaper, J. B., J. G. Morris, Jr., and M. M. Levine. 1995. Cholera. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 8:48-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kay, B. A., C. A. Bopp, and J. G. Wells. 1994. Isolation and identification of Vibrio cholerae O1 from fecal specimens, p. 41-51. In I. K. Wachsmuth, P. A. Blake, and O. Olsvik (ed.), Vibrio cholerae and cholera: molecular to global perspectives. ASM Press, Washington, DC

- 19.Keasler, S. P., and R. H. Hall. 1993. Detecting and biotyping Vibrio cholerae O1 with multiplex polymerase chain reaction. Lancet 341:1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lalitha, P., M. N. Siti Suraiya, K. L. Lim, S. Y. Lee, A. R. Nur Haslindawaty, Y. Y. Chan, A. Ismail, Z. F. Zainuddin, and M. Ravichandran. 2008. Analysis of lolB gene sequence and its use in the development of a PCR assay for the detection of Vibrio cholerae. J. Microbiol. Methods 75:142-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levine, M. M., J. B. Kaper, R. E. Black, and M. L. Clements. 1983. New knowledge on pathogenesis of bacterial enteric infections as applied to vaccine development. Microbiol. Rev. 47:510-550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim, K. L. 2006. Development of a DNA based molecular method for the detection of biotype, virulence and antibiotic resistance genotype of Vibrio cholerae. M.S. thesis. Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia.

- 23.Lindenbaum, J., W. B. Greenough, and M. R. Islam. 1967. Antibiotic therapy of cholera. Bull. World Health Organ. 36:871-883. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahalingam, S., Y. M. Cheong, S. Kan, R. M. Yassin, J. Vadivelu, and T. Pang. 1994. Molecular epidemiologic analysis of Vibrio cholerae O1 isolates by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:2975-2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsumoto, M., M. Suzuki, R. Hiramatsu, M. Yamazaki, H. Matsui, K. Sakae, Y. Suzuki, and Y. Miyazaki. 2002. Epidemiological investigation of a fatal case of cholera in Japan by phenotypic techniques and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Med. Microbiol. 51:264-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morita, M., M. Ohnishi, E. Arakawa, N. A. Bhuiyan, S. Nusrin, M. Alam, A. K. Siddique, F. Qadri, H. Izumiya, G. B. Nair, and H. Watanabe. 2008. Development and validation of a mismatch amplification mutation PCR assay to monitor the dissemination of an emerging variant of Vibrio cholerae O1 biotype El Tor. Microbiol. Immunol. 52:314-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mukhopadhyay, A. K., S. Garg, R. Mitra, A. Basu, K. Rajendran, D. Dutta, S. K. Bhattacharya, T. Shimada, T. Takeda, Y. Takeda, and G. B. Nair. 1996. Temporal shifts in traits of Vibrio cholerae strains isolated from hospitalized patients in Calcutta: a 3-year (1993 to 1995) analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:2537-2543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nair, G. B., S. M. Faruque, N. A. Bhuiyan, M. Kamruzzaman, A. K. Siddique, and D. A. Sack. 2002. New variants of Vibrio cholerae O1 biotype El Tor with attributes of the classical biotype from hospitalized patients with acute diarrhea in Bangladesh. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3296-3299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nair, G. B., F. Qadri, J. Holmgren, A. M. Svennerholm, A. Safa, N. A. Bhuiyan, Q. S. Ahmad, S. M. Faruque, A. S. Faruque, Y. Takeda, and D. A. Sack. 2006. Cholera due to altered El Tor strains of Vibrio cholerae O1 in Bangladesh. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:4211-4213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olsvik, O., J. Wahlberg, B. Petterson, M. Uhlen, T. Popovic, I. K. Wachsmuth, and P. I. Fields. 1993. Use of automated sequencing of polymerase chain reaction-generated amplicons to identify three types of cholera toxin subunit B in Vibrio cholerae O1 strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:22-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Popovic, T., C. Bopp, O. Olsvik, and K. Wachsmuth. 1993. Epidemiologic application of a standardized ribotype scheme for Vibrio cholerae O1. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:2474-2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Popovic, T., P. I. Fields, and O. Olsvik. 1994. Detection of cholera toxin genes, p. 41-51. In I. K. Wachsmuth, P. A. Blake, and O. Olsvik (ed.), Vibrio cholerae and cholera: molecular to global perspectives. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 33.Radu, S., M. Vincent, K. Apun, R. Abdul-Rahim, P. G. Benjamin, Yuherman, and G. Rusul. 2002. Molecular characterization of Vibrio cholerae O1 outbreak strains in Miri, Sarawak (Malaysia). Acta Trop. 83:169-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ranjit, K., and M. Nurahan. 2000. Tetracycline resistant cholera in Kelantan. Med. J. Malaysia 55:143-145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raychoudhuri, A., A. K. Mukhopadhyay, T. Ramamurthy, R. K. Nandy, Y. Takeda, and G. B. Nair. 2008. Biotyping of Vibrio cholerae O1: time to redefine the scheme. Indian J. Med. Res. 128:695-698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raychoudhuri, A., T. Patra, K. Ghosh, T. Ramamurthy, R. K. Nandy, Y. Takeda, G. B. Nair, and A. K. Mukhopadhyay. 2009. Classical ctxB in Vibrio cholerae O1, Kolkata, India. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15:131-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sack, D. A., R. B. Sack, G. B. Nair, and A. K. Siddique. 2005. Cholera. Lancet 63:223-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Safa, A., N. A. Bhuyian, S. Nusrin, M. Ansaruzzaman, M. Alam, T. Hamabata, Y. Takeda, D. A. Sack, and G. B. Nair. 2006. Genetic characteristics of Matlab variants of Vibrio cholerae O1 that are hybrids between classical and El Tor biotypes. J. Med. Microbiol. 55:1563-1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Safa, A., J. Sultana, P. D. Cam, J. C. Mwansa, and R. Y. C. Kong. 2008. Vibrio cholerae O1 hybrid El Tor strains, Asia and Africa. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:987-988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Speer, B. S., N. B. Shoemaker, and A. A. Salyers. 1992. Bacterial resistance to tetracycline: mechanisms, transfer, and clinical significance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 5:387-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Svennerholm, A.-M., and J. Holmgren. 1978. Identification of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin by means of a ganglioside immunosorbent assay (GM1-ELISA) procedure. Curr. Microbiol. 1.

- 42.Swerdlow, D. L., and A. A. Ries. 1993. Vibrio cholerae non-O1-the eighth pandemic? Lancet 342:382-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murray, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Towner, K. J., N. J. Pearson, F. S. Mhalu, and F. O'Grady. 1980. Resistance to antimicrobial agents of Vibrio cholerae E1 Tor strains isolated during the fourth cholera epidemic in the United Republic of Tanzania. Bull. World Health Organ. 58:747-751. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trucksis, M., J. E. Galen, J. Michalski, A. Fasano, and J. B. Kaper. 1993. Accessory cholera enterotoxin (Ace), the third toxin of a Vibrio cholerae virulence cassette. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90:5267-5271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vadivelu, J., L. Iyer, B. M. Kshatriya, and S. D. Puthucheary. 2000. Molecular evidence of clonality amongst Vibrio cholerae O1 biotype El Tor during an outbreak in Malaysia. Epidemiol. Infect. 124:25-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Belkum, A., P. T. Tassios, L. Dijkshoorn, S. Haeggman, B. Cookson, N. K. Fry, V. Fussing, J. Green, E. Feil, P. Gerner-Smidt, S. Brisse, and M. Struelens. 2007. Guidelines for the validation and application of typing methods for use in bacterial epidemiology. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13(Suppl. 3):1-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yam, W. C., M. L. Lung, and M. H. Ng. 1991. Restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of Vibrio cholerae strains associated with a cholera outbreak in Hong Kong. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:1058-1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]