Abstract

The MDM2 oncogene is overexpressed in 5–10% of human tumours. Its major physiological role is to inhibit the tumour suppressor p53. However, MDM2 has p53-independent effects on differentiation and does not predispose to tumorigenesis when it is expressed in the granular layer of the epidermis. These unexpected properties of MDM2 could be tissue specific or could depend on the differentiation state of the cells. Strikingly, we found that MDM2 has p53-dependent effects on differentiation, proliferation and apoptosis when it is expressed in the less differentiated basal layer cells. MDM2 inhibits UV induction of p53, the cell cycle inhibitor p21WAF1/CIP1 and apoptosis (‘sunburn cells’). Importantly, MDM2 increases papilloma formation induced by chemical carcinogenesis and predisposes to the appearance of premalignant lesions and squamous cell carcinomas. p53 has a natural role in the protection against UV damage in the basal layer of the epidermis. Our results show that MDM2 predisposes to tumorigenesis when expressed at an early stage of differentiation, and provide a mouse model of MDM2 tumorigenesis relevant to p53’s tumour suppressor functions.

Keywords: apoptosis/differentiation/p53/proliferation/tumours

Introduction

MDM2 is an oncoprotein that is deregulated in human tumours and has transforming properties. Five to 10% of human tumours overexpress MDM2 due to gene amplification or increased transcription and translation (for reviews see Haines, 1997; Piette et al., 1997; Prives, 1998; Freedman et al., 1999; Juven-Gershon and Oren, 1999; Momand et al., 2000). The Mdm2 gene is amplified in 30% of osteosarcomas (Oliner et al., 1992) and in 20% of soft tissue tumours in general (Momand et al., 1998). MDM2 overexpression has been associated with cancer predisposition in a Li–Fraumeni family (Picksley et al., 1996). MDM2 was originally identified as an amplified gene in spontaneously transformed Balb/c3T3 cells (Cahilly-Snyder et al., 1987). MDM2 overexpression confers tumorigenic properties upon fibroblasts (Fakharzadeh et al., 1991), immortalizes primary rat embryo fibroblasts and transforms them in the presence of Ras (Finlay, 1993). The major function of MDM2 is to inhibit the activity of the p53 tumour suppressor. In human tumours, MDM2 overexpression is considered to be an alternative mechanism of p53 inactivation. In general, p53 gene mutation and MDM2 gene amplification do not occur in the same tumours (Momand et al., 1998). In mice, inactivation of the two MDM2 genes results in embryonic lethality, which is rescued by inactivation of the p53 genes (Jones et al., 1995; Montes de Oca Luna et al., 1995).

MDM2 controls the activity of p53 by forming a complex with it. MDM2 interacts with the transcription activation domain of p53 and thereby blocks its transcriptional activity (Oliner et al., 1993). Binding leads to p53 ubiquitylation through the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of MDM2 (Haupt et al., 1997; Honda et al., 1997; Kubbutat et al., 1997; Fang et al., 2000; Honda and Yasuda, 2000). It also leads to export from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, where p53 is degraded by the ubiquitin-dependent proteosome pathway (Freedman and Levine, 1998; Roth et al., 1998; Lain et al., 1999; Tao and Levine, 1999). MDM2 gene transcription is regulated by p53, setting up an autoregulatory loop in which increased MDM2 production limits p53 induction in response to a variety of cellular stresses. The p53–MDM2 regulatory loop is crucial in the regulation of p53. Diminished or delayed inhibition by MDM2 results in activation of p53 and consequently increased transcription of target genes, such as p21WAF1/CIP1, which is involved in cell cycle arrest (el-Deiry et al., 1993; Harper et al., 1993) and Bax, which induces apoptosis (Miyashita and Reed, 1995). MDM2 interacts physically and functionally with a number of factors, including other members of the p53 and MDM2 families, the tumour suppressor ARF (p19ARF/p14ARF) and the cell cycle regulators E2F, pRb and p107.

The p53 family has two additional members, p73 and p63, which have overlapping properties (for reviews see Kaelin, 1999; Levrero et al., 2000; Lohrum and Vousden, 2000). MDM2 binds to p73 and inhibits p73-mediated transactivation and apoptosis, but does not stimulate its degradation. p73 regulates the MDM2 promoter, which may produce an autoregulatory loop. p63 regulates the MDM2 promoter, but the effects of MDM2 on p63 have not been established. MDM2 interacts with its homologue, MDMX, resulting in inactivation of E3 ligase and export activities of MDM2 and the formation of a nuclear pool of inactive p53 (Jackson and Berberich, 2000). There is considerable potential for complex circuitry and regulation between the different members of the p53 and MDM2 families. However, p53 and MDM2 appear to be the important factors for tumour suppression, since they are principally associated with tumour formation whereas the other members appear to be involved in development. The interaction of MDM2 with the tumour suppressor p19ARF/p14ARF results in activation of p53 by two mechanisms. Complex formation inhibits MDM2 E3 ligase activity, resulting in p53 stabilization. Complex relocalization to the nucleolus releases p53 in the nucleus (for review see Sherr and Weber, 2000). E2F1 in complex with DP1 is a positive regulator of the cell cycle that is inhibited by pRb. Binding to MDM2 activates E2F1 and inhibits pRb, leading to activation of the cell cycle in a p53-independent manner.

MDM2 overexpression interferes with a variety of developmental and differentiation processes. MDM2 inhibits differentiation of myoblasts by inhibiting Myo-D (Fiddler et al., 1996). Targeted expression to the mammary gland in mice inhibits mammary gland development and uncouples S phase from mitosis in a p53- and E2F1-independent manner (Lundgren et al., 1997; Reinke et al., 1999). Overexpression driven by the entire Mdm2 gene predisposes to spontaneous tumour formation (Jones et al., 1998) and reveals a p53-independent role for MDM2 in tumorigenesis. Overexpression in the differentiating compartment of the epidermis inhibits differentiation in a p53-independent manner, but does not predispose to tumour formation (Alkhalaf et al., 1999). These studies reveal p53-independent roles of MDM2; the contribution of p53 to the physiology of the targeted cells and to the observed phenotypes is not clear. Since the principal function of MDM2 is to inhibit p53, we have targeted MDM2 expression to cells in the epidermis in which p53 has an established role.

p53 is the key UV-responsive gene in skin whose mutation is thought to initiate carcinogenesis (for review see Soehnge et al., 1997). Skin cancer is increasing at an alarming rate; it is estimated that one million new cases occur each year in the USA, primarily due to UV exposure from sunlight. Epidermal keratinocytes are most susceptible to damage from UV, because they are close to the skin surface. Skin epidermis is a stratified epithelium in which the basal layer contains stem cells and transient amplifying cells that divide continuously to supply cells that enter the differentiating programme and move up the epidermis. A fine balance between proliferation and differentiation maintains the integrity of the epidermis (for reviews see Fuchs, 1995; Eckert et al., 1997). p53 is expressed at low levels in unexposed skin. UV induces p53 in basal layer cells (Hall et al., 1993; Jonason et al., 1996), resulting in cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, which protects from cancer induction (Jiang et al., 1999). UV damage to the p53 gene inhibits the normal protective response, predisposing to cancer (Ziegler et al., 1994; Berg et al., 1996). The role of p53 changes during epidermal differentiation, principally in that its protective function becomes dispensable in late differentiating cells that are dying (Song and Lambert, 1999; Tron et al., 1999).

Keratinocytes undergo a complex developmental programme as they progress from the basal to the spinous, granular and finally the cornified layer of the epidermis. Specific markers of differentiation include cytokeratins K6 and K16 in the inner root sheath of hair follicles, K5 and K14 in the basal layer, K1 and K10 in the spinous layer, and involucrin, loricrin and filaggrin in the granular layer. p63 is abundant in hair follicles and basal cells and is absent from the cells that are undergoing terminal differentiation. Whenever p63 mRNA is present, it encodes mainly truncated, potentially dominant-negative isotypes that would not be expected to interact with MDM2 (Parsa et al., 1999). Inactivation of p63 by homologous recombination in the mouse shows that it is important for epidermal differentiation (Mills et al., 1999; Yang et al., 1999). MDM2 is expressed in the basal layer and at a higher level in the suprabasal layer (Dazard et al., 1997; see also Results). MDM2 expression increases and p53 levels decrease when epidermal keratinocytes are induced to differentiate in vitro (Weinberg et al., 1995), suggesting that MDM2 expression in the epidermis may be associated with entry into the differentiation programme.

We previously reported that MDM2 expression in the granular layer has p53-independent effects and does not predispose to tumour formation (Alkhalaf et al., 1999). Since the major role of MDM2 is regulation of p53, and since p53 tumour suppressor functions are important in the basal layer, we targeted MDM2 expression to the basal layer under the control of the K14 promoter. We found that transgenic MDM2 inhibits UV induction of p53 and affects proliferation, apoptosis and differentiation in a p53-dependent manner. In contrast to findings of our previous study, we show here that exogenous MDM2 enhances both papilloma formation induced by chemical carcinogenesis and spontaneous development of premalignant lesions in older animals. These results show that the oncogenic potential of MDM2 in vivo is revealed when it is targeted to cells in which p53 suppresses tumorigenesis.

Results

MDM2 expression in normal mouse and human skin

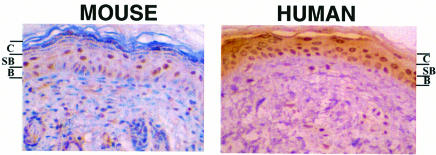

We have previously shown by western blotting that the MDM2 protein is expressed in normal adult mouse skin (Alkhalaf et al., 1999). In order to identify the cells that express MDM2, we used immunohistochemistry (IHC) with a high temperature antigen unmasking protocol (Materials and methods). We found that MDM2 is expressed highly in the suprabasal layer of the epidermis and to a lesser extent in the basal layer (Figure 1). Similarly, in unexposed normal human adult skin, MDM2 was detected primarily in the suprabasal layer and to a lesser extent in the basal layer, in agreement with a previous report (Dazard et al., 1997). Endogenous MDM2 was not detected by IHC when the high temperature antigen unmasking was omitted (Alkhalaf et al., 1999; see below). These results suggest that MDM2 is expressed as keratinocytes begin to differentiate and move into the suprabasal level. We showed previously that MDM2 expression in the granular layer, which extends MDM2 expression into later periods of differentiation, gave a p53-independent phenotype (Alkhalaf et al., 1999). In order to extend MDM2 expression to an earlier time in development, and to cells that are normally sensitive to p53 induction, we expressed MDM2 in the basal proliferative layer of the epidermis.

Fig. 1. IHC detection of endogenous MDM2 protein in normal mouse and human skin. Paraffin sections were treated with a high temperature antigen unmasking protocol to visualize endogenous proteins. Positive cells are stained brown. C, stratum corneum; SB, suprabasal layer; B, basal layer. Original magnification, ×100.

Generation of transgenic mice with targeted expression of MDM2 in the basal layer

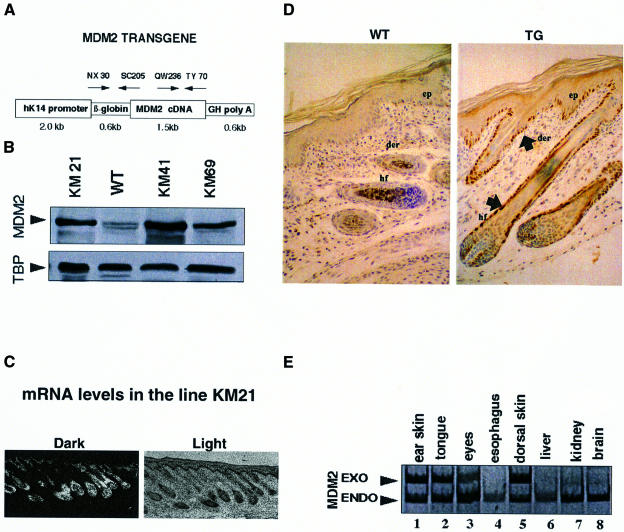

MDM2 was expressed in the basal layer with a transgene containing 2 kb of the human K14 promoter, the rabbit β-globin intron, mouse MDM2 cDNA and the growth hormone poly(A) signal (Figure 2A). The 2 kb human K14 promoter has been shown to drive expression to the basal cells of squamous epithelia (Coulombe et al., 1989; Vassar et al., 1989; Wang et al., 1997). Ten transgene-positive founders were generated, of which four transmitted the transgene, three did not give germline transmission and three bred poorly. Two of the four lines (KM21 and KM41) were used for further study. The adult dorsal skin from the principal transgenic lines expressed about five times more MDM2 protein than wild-type skin, as shown by western blotting (Figure 2B). Transgenic MDM2 RNA was expressed in the basal layer of the epidermis and in hair follicles, using in situ hybridization and a radiolabelled probe (Figure 2C; endogenous MDM2 did not contribute significantly to the signal under these conditions; data not shown). Exogenous MDM2 protein was detected by IHC in the basal layer and in the hair follicles of 6-day-old dorsal skin (Figure 2D, TG). Endogenous MDM2 was not detected under these conditions, without high temperature antigen unmasking (Figure 2D, WT; see also above). Exogenous MDM2 RNA was detected by RT–PCR in several tissues, including skin, tongue and eyes, which contain stratified squamous epithelium, but not in oesophagus, liver, kidney or brain (Figure 2E). Endogenous MDM2 RNA was detected in all the samples.

Fig. 2. Expression of exogenous MDM2. (A) Schematic representation of the K14–MDM2 transgene construct. The transgene contains the human K14 promoter (2 kb), rabbit β-globin intronic sequences (0.6 kb), mouse MDM2 cDNA (1.5 kb) and the growth hormone poly(A) signal (0.6 kb). PCR primers are indicated with arrows. (B) Western blot analysis of the KM21, 41 and 69 lines and wild-type animals. The mol. wt 90 000 MDM2 band detected with the #364 anti-MDM2 antibody is indicated. TBP is a control for loading. (C) In situ hybridization with frozen sections of the dorsal skin of day 6 KM21 mice and 35S-labelled antisense RNA prepared with the 1.5 kb MDM2 cDNA. Original magnification, ×50. (D) IHC without high temperature unmasking, using the #364 antibody against MDM2 and paraffin sections of the dorsal skin of day 6 KM21 mice (TG). Note that endogenous MDM2 is not clearly detected in the wild type (WT) without high temperature unmasking. Abbreviations: ep, epidermis; der, dermis; hf, hair follicle. (E) RT–PCR detection of MDM2 RNA in different tissues. Five micrograms of RNA from different organs were analysed by RT–PCR using specific primers. PCR products were resolved in 6% acrylamide gels, stained with ethidium bromide and photographed. The control was GAPDH (not shown). EXO and ENDO indicate specific bands expected for exogenous and endogenous MDM2, respectively.

Overall appearance and histopathology

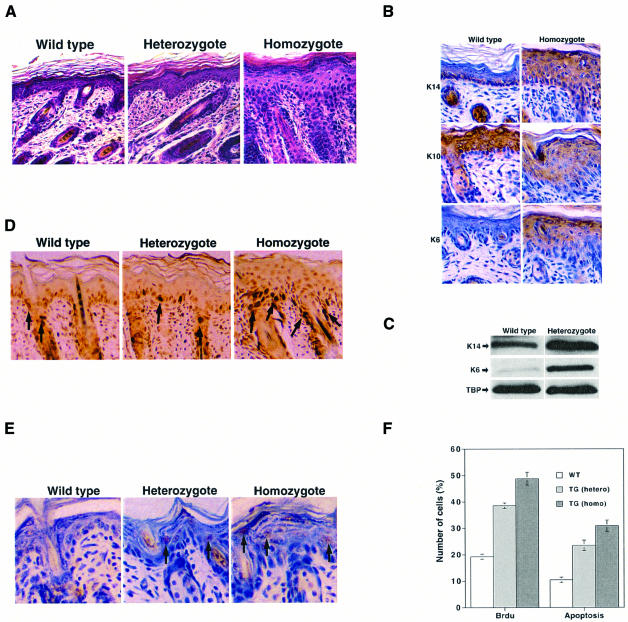

At birth, the skin of heterozygous transgenic pups was indistinguishable from that of their littermates. After 5–6 days, some scales appeared, mostly in the middle dorsal and lower trunk regions but also to a lesser extent on the tail. The appearance of coat hair was delayed until after ∼2 weeks. In homozygotes the early phenotype was more severe, with extensive flaking and peeling on the back, tail and legs; in addition, these mice were smaller, though later their growth caught up with that of their littermates (not shown). The histology of the dorsal skin was examined using haematoxylin and eosin-stained sections (Figure 3A). The epidermis of control skin was uniform in thickness and had one basal and two suprabasal layers of cells. The epidermis of heterozygotes was somewhat thicker and that of homozygytes was much thicker, with more cells in the basal layer and nucleated cells even in the late differentiated compartments.

Fig. 3. Pathology of the dorsal skin. (A) Histology. Dorsal skin from 6-day-old mice was fixed and paraffin sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin. Note especially that the homozygous epidermis is considerably thickened, with nucleated cells throughout and increased cellular density in the dermis. Original magnification, ×100. (B) Differentiation and proliferation markers in wild-type and homozygous animals. IHC was performed with antibodies against K14, K10 and K6. Original magnification, ×200. (C) Western blots for K14 and K6. Total cell extracts were prepared with RIPA buffer from the dorsal skin of wild-type and heterozygous animals and blotted with specific antibodies against K14 (PRB-169P; Babco), K6 (PRB-169P; Babco) and TBP (loading control, 3G3, generously given by L.Tora). (D) Proliferation. Wild-type, heterozygous and homozygous animals were labelled by injection with BrdU and sections were analysed by IHC with antibodies against BrdU. Arrows indicate some of the positive brown-staining cells. Original magnification, ×200. (E) Apoptosis. Wild-type, homozygous and heterozygous skin sections were analysed with the Apoptag Oncor kit. Arrows indicate some of the TUNEL-positive cells. Original magnification, ×200. (F) Quantification of proliferation and apoptosis. Five hundred cells from five areas and three animals were counted and the number of positive cells expressed as a percentage of the total. The differences between the wild type (WT) and heterozygote, and between the heterozygote and homozygote, were statistically significant (P <0.0001), as assessed by the unpaired t-test (Statview program).

Altered differentiation programme

Differentiation was studied using IHC of paraffin sections; K14 and K5 were used as markers for basal proliferating cells, K10 for early differentiating cells, loricrin for later differentiation cells (Fuchs and Green, 1980; Nelson and Sun, 1983; Lersch and Fuchs, 1988) and K6 for proliferating cells found in hair follicles and in skin pathologies (Weiss et al., 1984; Stoler et al., 1988). K14 expression was markedly altered in transgenic mice, with high levels in the suprabasal layers in homozygotes (Figure 3B) and in heterozygotes (not shown). Similar results were obtained with K5 (data not shown). The patterns of K10 (Figure 3B) and loricrin expression (not shown) were apparently unaltered. K6 was expressed at higher levels in the suprabasal layer of the skin (Figure 3B). Western blots of skin extracts confirmed that K14 and K6 were expressed at higher levels in heterozygotes (Figure 3C) and homozygotes (data not shown). Thus, overexpression of MDM2 in the basal layer deregulates the expression of keratin markers, showing that it affects differentiation.

Increased proliferation in the basal layer and more apoptosis in hair follicles and the suprabasal layer

The increased thickness of the epidermis and expression of K6 suggested that MDM2 stimulates proliferation. Proliferation was studied directly by incorporation of the thymidine analogue 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU) followed by IHC with BrdU-specific antibodies. In 6-day-old mice, there were more BrdU-labelled cells in the skin of transgenic heterozygotes and homozygotes than in the skin of their wild-type littermate controls (Figure 3D and F); this difference was reproducible and statistically significant (P <0.0001). The proliferating cells were located in the expected places, in the basal layer and hair follicles. Similar results were obtained using IHC for PCNA, an accessory protein of DNA polymerase that is associated with the replication machinery (data not shown). Apoptosis counter-balances proliferation, so it affects the thickness of the epidermis. Apoptosis was detected by the TUNEL assay, in which DNA fragments associated with apoptosis are labelled at their 3′ ends with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase. There was a reproducible and statistically significant increase in the number of TUNEL-positive cells in transgenic epidermis (Figure 3E and F; P <0.0001). The increase in apoptosis compensates for the greater proliferation and probably accounts for the small increase in epidermal thickness in heterozygous mice. The apoptotic cells were found in the suprabasal layer, where DNA fragmentation is usually observed, and in hair follicles. This increased apoptosis, as well as delayed cellular differentiation, could account for the delay in the appearance of the hair.

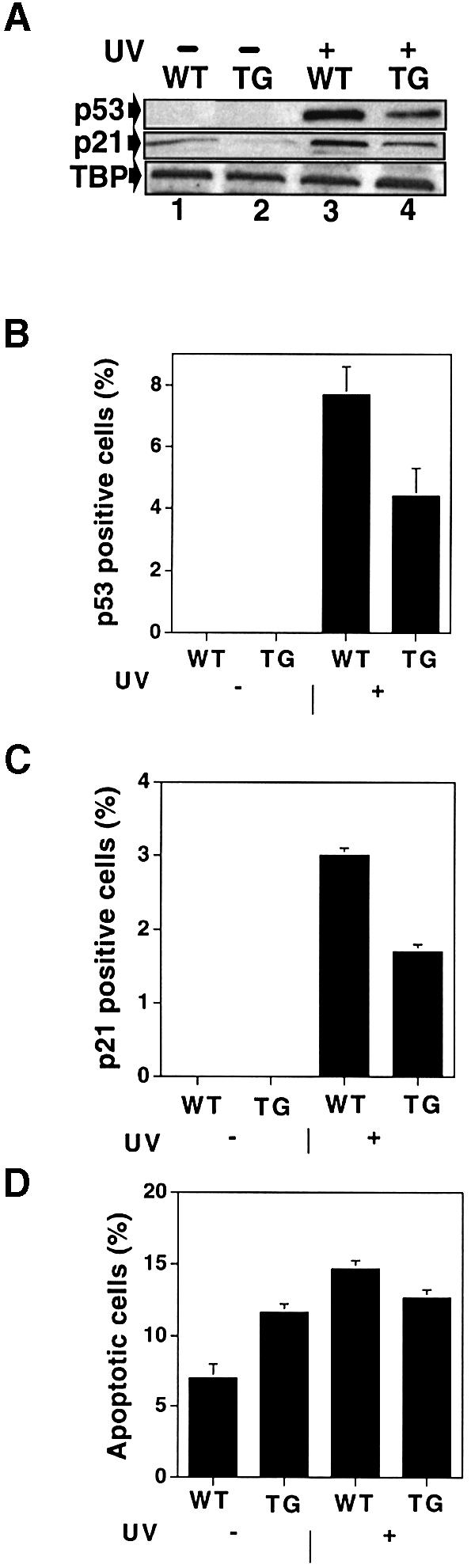

Inhibition of p53 by MDM2 overexpression

There is a low level of p53 in the basal layer of the epidermis, which is increased by UV, resulting in enhanced levels of p21WAF1/CIP1 and apoptosis (Ziegler et al., 1994; Ananthaswamy et al., 1998; Song and Lambert, 1999; Ouhtit et al., 2000). UV also increases MDM2 levels in normal epidermis (data not shown). To establish that exogenous MDM2 inhibits the p53 response, dorsal skin was exposed to 5000 J/m2 of UV and 24 h later biopsies were examined by western blotting for p53 and p21WAF1/CIP1 levels (Figure 4A) and by IHC for p53, p21WAF1/CIP1 and apoptosis (Figure 4B–D). p53 protein levels were markedly induced in wild-type animals; the increase was lower in transgenic animals (Figure 4A). p21WAF1/CIP1 was also induced to higher levels in wild-type animals than in the transgenic ones (Figure 4A). There was a statistically significant decrease in the induction of p53- (Figure 4B) and p21WAF1/CIP1-positive cells (Figure 4C) in the transgenic epidermis. In contrast, there was no significant increase in apoptotic cells in transgenic animals, even though there was a clear increase in these cells in wild-type animals (Figure 4D). These results demonstrate that exogenous MDM2 inhibits the induction of p53, p21WAF1/CIP1 and apoptosis. Curiously, MDM2 expression inhibits apoptosis induced by UV, but increases apoptosis in the absence of induction. The inhibition may result from a direct effect on p53 induction by UV. The increase may be a consequence of natural homeostasis in the epidermis that compensates for increased proliferation by greater cell death, to maintain overall thickness.

Fig. 4. Analysis of p53, p21WAF1/CIP1 and apoptosis in UV treated skin. (A) Western blots of p53 and p21WAF1/CIP1 expression. Transgenic and wild-type mice were UV irradiated; 24 h later, total cell extracts were prepared using RIPA buffer, fractionated by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted with antibodies against p53 (NCL-P53-CM5), anti-p21WAF1/CIP1 (C-19) and TBP (3G3, a control for equal loading). (B and C) Quantification of p53- (B) and p21WAF1/CIP1-positive cells (C). Twenty-four hours after UV irradiation, dorsal skin was analysed by IHC and positive cells from four different mice were counted. Error bars indicate the standard deviation. The differences between wild-type and transgenic samples in UV-induced p53- and p21WAF1/CIP1-positive cells were statistically significant (P <0.001). (D) Quantification of apoptotic cells. Twenty-four hours after UV irradiation, dorsal skin was analysed with the Apoptag Oncor kit and positive cells were counted using samples from four different mice. Error bars indicate the standard deviation. There was a statistically significant difference in apoptosis between UV irradiated and non-irradiated wild-type animals (P <0.001), whereas the difference is not significant in the transgenic animals (P <0.3). WT, wild type; TG, transgenic KM21 line.

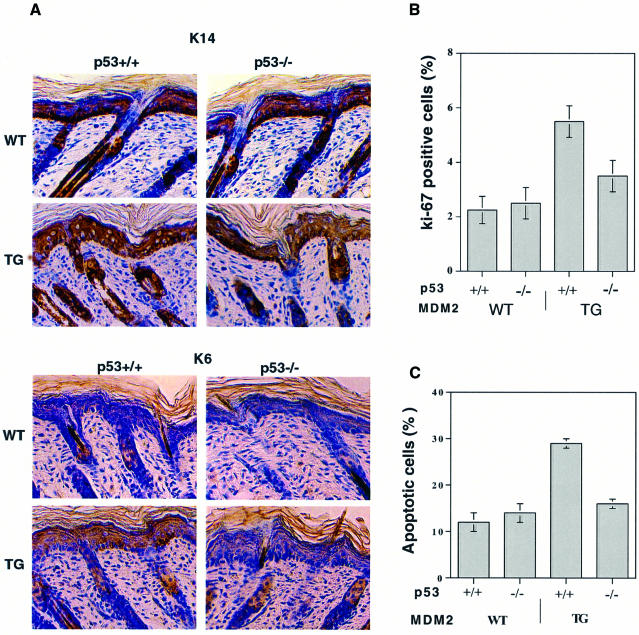

Functional interaction of MDM2 and p53 in vivo

K14–MDM2 transgenic mice have altered levels and localization of K14 and K6 expression, and increased proliferation and apoptosis. To examine whether p53 is involved in these effects, the K14–MDM2 mice were crossed on to a p53-null background. The levels of K14 and K6 expression in the p53-null transgenic animals were lower than those in the p53-wild-type transgenics, and similar to the levels in the non-transgenic animals (Figure 5A). The level of the proliferation marker, Ki-67, was also decreased in the p53-null transgenic animals compared with the wild-type transgenic mice, to a level comparable to that in the non-transgenic animals (Figure 5B). Similarly, there was less apoptosis in the p53-null transgenics than in the wild-type transgenics (Figure 5C). These results show that the phenotypic alterations observed in K14–MDM2 animals are dependent on the presence of p53.

Fig. 5. Effect of p53 background on differentiation, cell proliferation and apoptosis. (A) IHC with K14 and K6 antibodies. Original magnification, ×100. (B) Quantification of IHC with Ki-67 antibodies. (C) Quantification of TUNEL-positive cells with the same samples as in (B). One hundred cells were counted from four different fields and three different mice. Error bars indicate the standard deviation. The differences are significant between p53+/+ and p53–/– transgenics (P <0.0001), and between p53+/+ wild types and transgenics (P <0.0002). TG, transgenic KM21 line.

Mdm2 overexpression increases susceptibility to chemical carcinogenesis

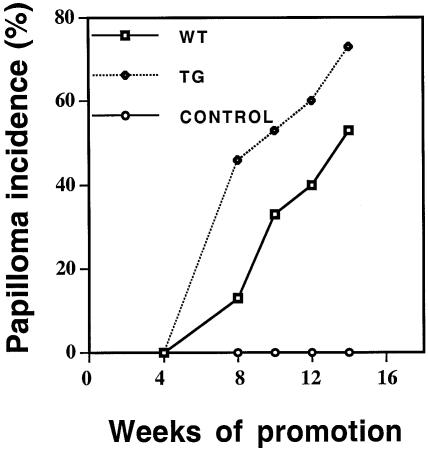

To study susceptibility to carcinogenesis, we treated 6–8-week-old transgenic and wild-type females with the initiator DMBA and then promoted twice a week with TPA. Papillomas began to appear after 7 weeks of treatment (Figure 6). At all times, a statistically significantly higher proportion of the transgenic mice developed papillomas than wild-type animals. The difference was greater initially than it was later. These results demonstrate that K14–MDM2 transgenic mice are more sensitive to chemically induced carcinogenesis than normal mice.

Fig. 6. Susceptibility of K14–MDM2 (KM21) transgenic mice to chemical carcinogenesis. Female mice (15 per group) were treated with the tumour initiator DMBA and the tumour promoter TPA. The number of papillomas was determined at various times. The data represent the mice bearing papillomas divided by the total number. At 8 and 14 weeks, the tumour incidences were statistically different between the two groups (P <0.001). WT, wild type; TG, transgenic; control, acetone vehicle alone.

Adult K14–MDM2 transgenic mice develop hyperproliferative lesions

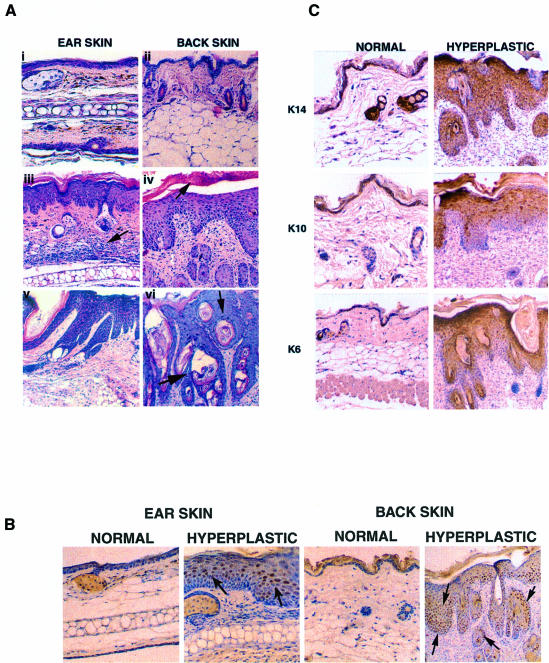

The K14–MDM2 mice were normal at birth. After ∼4 days they developed mild scaling on their backs and tails; this scaling disappeared with age (see above). Later, they displayed a number of abnormalities. They lost hair, especially on the snout, around the eyes and on the back (Table I; the phenotype was observed in the three lines studied). Many of the mice (about a third of the KM21 line) developed skin lesions on their ears and back. The affected skin was red, visibly keratotic and thickened. Histological examination of the ear lesions (Figure 7A, panels i, iii and v) showed that there was distinct mild hyperplasia of the epidermis, with a 2- to 3-fold increase in all the cell layers. In the thickest parts, there were increases in the number of basal cells, overlaid with cells intermediate between the basal and spinous layers. Hyperchromatic enlarged cells were found throughout the epidermis, hair follicles were massively enlarged and sebaceous glands were also occasionally affected. The majority of the lesions also displayed increased cellularity in the dermis (see arrow in Figure 7A, panel iii). The ear lesions had early papillomatous features (Figure 7A, panel v). The papillomas were inverted and premalignant, with anaplastic and dysplastic cells. The nuclei were large, irregular and hyperchromatic. The lesions on the dorsal skin and in the axillary regions were often more advanced (Figure 7A, panels ii, iv and vi). They were slightly raised and were papillomatous as shown by histological examination. The epidermis was hyperplastic, with abnormal keratinization, hyperkeratosis, acanthosis and parakeratosis (see arrow in Figure 7A, panel iv). In certain cases the lesions were dysplastic, with keratinized foci throughout the epidermis (Figure 7A, panel vi). In highly affected individuals, the lesions covered the entire ear and large areas of the back. The lesions did not regress and sometimes became malignant. In the KM21 line, 33% developed skin lesions and 5% formed squamous cell carcinomas that were undifferentiated or differentiated. In addition to skin lesions, the mice also developed abnormalities and tumours in other places (Table I), which were either associated with the epidermis (fibrosarcomas) or in tissues in which the K14 promoter is expressed (mammary gland and eye). They developed fibrosarcomas in the skin of the ears, legs and inguinal region. The mammary tumours were adenocarcinomas with squamous metaplasia and keratinized foci. The eye defects were ulcerous, with corneal hyperproliferation and opacity (data not shown).

Table I. Summary of the adult phenotypic lesions in K14–MDM2 transgenic mice.

| Transgenic lines | No. of mice | Skin lesions | SCC | Fibrosarcomas | Mammary tumours | Eye defects | Hair loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KM21 |

75 |

25 (33%) |

4 (5%) |

3 (10%) |

2 (2.6%) |

5 (6.6%) |

32 (42%) |

| KM41 |

28 |

3 (10%) |

0 |

1 (3.5%) |

1 (3.5%) |

2 (7.1%) |

8 (28%) |

| KM69 |

18 |

1 (5.5%) |

0 |

1 (5.5%) |

0 |

0 |

4 (22%) |

| Wild type | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Various pathologies were observed in adult transgenic mice, including skin lesions on the ears and back, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), fibrosarcoma, mammary tumours, eye defects and hair loss. Of the 25 mice with skin lesions, 18 were analysed by haematoxylin and eosin staining and seven for MDM2 production by IHC. The skin lesions included papillomas, hyperplasia, dysplasia, hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis and acanthosis. The wild-type controls included littermates from all three transgenic lines.

Fig. 7. Histology and expression of MDM2 and differentiation markers in adult skin preneoplastic lesions and tumours. (A) Haematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of back and ear skin lesions in KM21 and wild-type mice that were >18 months old. (i and ii) Unaffected transgenic skin; (iii–vi) lesions; (i), (iii) and (v) are ear skin, and (ii), (iv) and (vi) back skin. Arrows indicate excessive cellularity in the dermis (iii), parakeratosis (iv) and keratinized foci throughout the epidermis (vi). Original magnification, ×100. (B) Expression of MDM2. IHC with antibody #364 against MDM2 and sections of normal and hyperplastic skin from the ear (original magnification, ×200) and back (original magnification, ×100). Note that many MDM2-positive cells (brown-stained nuclei) are seen in the expanded basal layer and the outer root sheath (ORS) of hair follicles (arrows). (C) Expression of differentiation markers. IHC of normal and hyperplastic dorsal skin with antibodies against K14, K10 and K6. Original magnification, ×100.

The presence of MDM2 and differentiation markers in the adult lesions was examined by IHC. There were high levels of MDM2 in hyperplastic and dysplastic lesions from the ear and dorsal skin, in both the proliferating and differentiating layers (Figure 7B). MDM2 was barely detectable in the unaffected ear and back skin of transgenic mice of similar age. MDM2 was also detected in fibrosarcomas of ear and leg skin, as well as in mammary tumours (data not shown). K14 was detected in almost the entire hyperplastic epidermis, with greatest amounts found in the upper layers (Figure 7C). K10 was detected in the upper layers, indicating that the keratinocytes were differentiating to some extent, despite the high level of proliferation. K6 expression was up-regulated in the interfollicular suprabasal keratinocytes of the hyperplastic epidermis, similar to the observations in other mouse models of epithelial carcinoma (Vassar et al., 1992; Greenhalgh et al., 1993; Coussens et al., 1996). In conclusion, these results show that MDM2 expression driven by the K14 promoter predisposes to the development of hyperplastic lesions that can progress to papillomas and squamous cell carcinomas.

Discussion

MDM2 appears to be important for epidermal differentiation. It is highly expressed in normal human and mouse skin (Dazard et al., 1997; Alkhalaf et al., 1999; this study). MDM2 overexpression in two different layers perturbs the differentiation programme (Alkhalaf et al., 1999; this study). MDM2 has been implicated in regulation of differentiation in other systems (Fiddler et al., 1996). It may affect differentiation through inhibition of p53 or interaction with other molecules. p53 has been implicated in cell differentiation and development (Almog and Rotter, 1997). p63, a homologue of p53, is important for epidermal differentiation (Mills et al., 1999; Yang et al., 1999). However, it appears unlikely that MDM2 affects p63 activity since the variant expressed in the epidermis lacks the putative MDM2 interaction domain (Parsa et al., 1999). MDM2 is expressed in both the basal and suprabasal layers, in which keratinocytes enter the differentiation programme, suggesting that MDM2 is involved in the early steps of differentiation, in which the decision occurs as to whether the basal proliferating cell will enter the proliferation programme. In support of this hypothesis, it has been shown that MDM2 levels increase when keratinocytes are induced to differentiate in vitro (Weinberg et al., 1995). p53 activity could influence MDM2 levels since MDM2 is one of its target genes. However, p53 may not be the major determinant of the basal level of MDM2. p53 levels are low in uninduced conditions in the epidermis (Hall et al., 1993). Further more, MDM2 expression is independent of p53 in keratinocytes (Dazard et al., 1997) and epithelia during mouse development (Leveillard et al., 1998). Constitutive MDM2 expression is thought to set the sensitivity of cells to p53 induction (for reviews see Haines, 1997; Piette et al., 1997; Prives, 1998; Freedman et al., 1999; Juven-Gershon and Oren, 1999; Momand et al., 2000). The consequences of p53 induction are differentiation dependent in the epidermis, resulting in either cell cycle arrest or apoptosis in different compartments (Tron et al., 1998a,b, 1999; Song and Lambert, 1999). The basal levels of MDM2 may help determine whether p53 induction results in cell cycle arrest or apoptosis in different keratinocyte populations.

MDM2 overexpression in different layers of the skin has similar effects on differentiation, proliferation and apotosis. However, the molecular mechanisms of these effects are not identical since p53 removal has an effect only when MDM2 is expressed in the basal layer. These observations are explicable in the light of the known properties of MDM2 and p53. MDM2 interacts with a number of proteins that have roles in the epidermis, including p53 (Soehnge et al., 1997; Leffell, 2000), pRb (Paramio et al., 1998), E2F1 (Wang et al., 2000), SMAD/transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) (Sun et al., 1998; Yam et al., 1999) and alternative reading frame (ARF) (Serrano, 2000). The pathways regulated by these molecules are interconnected in different ways. For example, p53 regulates expression of p21WAF1/CIP1, an inhibitor of cyclin/CDK that regulates pRb and E2F. MDM2 can thereby affect pRb and E2F1 indirectly through p53 and directly through protein–protein interactions. The role of p53 changes in different states of keratinocyte differentiation. p53 induction results in apoptosis of proliferating keratinocytes, whereas p53 is not activated in late-stage suprabasal cells (Tron, 1998b; Song and Lambert, 1999; Tron et al., 1999). MDM2 produced in the basal layer has effects on p53 and can thereby indirectly target downstream molecules such as E2F and pRb. MDM2 produced in late differentiating keratinocytes cannot do this and can only target downstream molecules directly, resulting in a p53-independent phenotype.

In the in vivo MDM2 overexpression studies that have been performed, the phenotypes have been shown to be p53 independent. MDM2 inhibits development of the mammary gland when its expression is directed to mammary cells by the β-LG promoter (Lundgren et al., 1997). MDM2 induces multiple rounds of S phase without completion of mitosis, in the absence as well as the presence of p53. Sixteen per cent of the mice develop mammary tumours later in life, which may be a direct consequence of DNA instability rather than due to effects on p53. In another report, only one line with the mdm2 gene as the transgene was studied (Jones et al., 1998). This line displayed increased tumorigenesis, with a high incidence of sarcomas that was retained in a p53–/– background. The cell types targeted by the transgene are unknown; they may be cells in which p53 is not functional, since the mdm2 gene has a tissue-specific expression pattern in the absence of p53 (Leveillard et al., 1998).

We report that MDM2 expression driven by the human K14 promoter has p53-dependent effects. UV irradiation induces p53 in the basal and suprabasal layers and stimulates p21WAF1/CIP1 expression, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. In K14–MDM2 mice, following UV irradiation, there are fewer cells with nuclear accumulation of p53, with elevated p21WAF1/CIP1 and undergoing apoptosis (‘sunburn cells’), showing that p53 is inhibited. In a p53–/– background, all the phenotypic effects of transgenic MDM2 are diminished, including expression of the differentiation marker K14, the proliferation markers K6, Ki-67 and PCNA (not shown), and apoptosis. These results show that the effects of MDM2 are p53 dependent. Interestingly, removing p53 is not equivalent to expression of MDM2. In p53–/– animals the pattern of expression of K14 is not altered, and K6 and Ki-67 expression and apoptosis are not elevated. There are several possible explanations for this. In p53–/– mice, all the cells in the animal are affected throughout development. This may lead to the functions of p53 being compensated for by redundancy with other members of the family. Alternatively, the phenotypic effects may depend on interactions between cells. The surrounding tissues (e.g. the dermis) lack p53 in p53–/– animals, but contain p53 in transgenic animals. In addition, the presence of an ‘inactive’ p53–MDM2 complex may not be simply equivalent to the absence of p53.

Young K14–MDM2 mice display changes in epidermal proliferation resulting in mild scaling in heterozygous animals and delayed appearance of hair. After several months, during which they appear normal, the mice develop a variety of skin lesions with high penetrance. Many of the animals lose hair in patches on the back, around the snout and eyes. There are many apoptotic cells in the hair follicles of these animals, which probably accounts for the hair loss. These animals also develop localized lesions of the skin on the back and ears, and, to a lesser extent, mammary tumours and eye defects. They occasionally develop fibrosarcomas; these have been found in other studies in which oncogene expression is targeted with the K14 promoter, and their origin has not been explained. Focal spontaneous preneoplastic lesions have been reported in other studies of K14-targeted expression, including erbB-2 (Xie et al., 1998), sonic hedgehog (Oro et al., 1997), β-catenin (Chan et al., 1999), TGF-α (Vassar and Fuchs, 1991) and human papillomavirus 16 E6 and E7 (Vassar and Fuchs, 1991). Squamous cell carcinomas develop at a low frequency in K14–MDM2 mice. Chemical carcinogenesis induces more papillomas in transgenic mice. These results show that MDM2 expression in the basal layer of the epidermis predisposes to tumorigenesis.

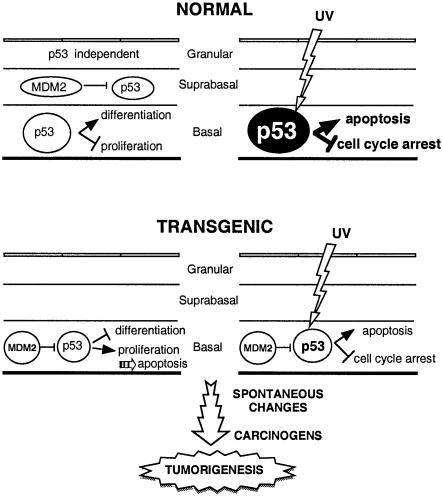

The potential role of MDM2 in the epidermis and its effects on tumorigenesis are summarized in Figure 8. In normal epidermis, p53 levels are low. p53 may be activated during the exit from the proliferative state, resulting in inhibition of cell division and stimulation of differentiation. The consequence of p53 activation could be the MDM2 expression that is observed in the basal and the suprabasal layers. Later, as the keratinocytes progress in the differentiation associated with the ‘cell death’ programme, they become insensitive to p53-induced apoptosis. UV induces p53 in the proliferative compartment of the basal layer, resulting in protection from the tumorigenic effects of DNA damage, by DNA repair during cell cycle arrest, or by apoptosis. In transgenic mice, p53 is inhibited by MDM2 produced in the basal layer, leading to decreased differentiation and increased proliferation. Increased apoptosis is an indirect effect of the mechanisms that maintain homeostasis. The UV response is impaired by MDM2, thereby decreasing the protective effect of p53. The reduced tumour suppressor function of p53 results in increased papilloma formation after chemical carcinogenesis and spontaneous accumulation of genetic lesions resulting in the appearance of hyperplastic lesions and carcinomas.

Fig. 8. Model of the potential role of MDM2 in the epidermis and its effects on tumorigenesis.

In conclusion, targeting of MDM2 to cells in which p53 is active is required to increase the susceptibility to tumorigenesis, as opposed to the effects on differentiation, cell division and apoptosis. The surface location of the preneoplastic lesions, and the known biological relevance of p53 in skin cancer and MDM2 in p53-dependent tumour formation, should make these mice a useful tool to develop and analyse pharmaceuticals aimed at inhibiting tumour formation by MDM2.

Materials and methods

Construction of the transgene and the transgenic lines

The PHR2 plasmid (a gift from S.Werner), containing the 2 kb human K14 promoter, rabbit β-globin intronic sequences, truncated mouse FGFRI cDNA and growth hormone poly(A), was digested with SmaI to release the FGFRI cDNA. The resulting plasmid was ligated to MDM2 cDNA that was prepared by double digesting cytomegalovirus (CMV)–MDM2 recombinant (Alkhalaf et al., 1999) with HindIII and SpeI, and blunt ending. The KpnI fragment, containing the expression unit, was purified on a sucrose gradient and microinjected into SJL/C57BL/6 hybrid zygotes. The founders were screened by PCR using primers NX30 (β-globin exon 1 sequence), SC205 (MDM2 exon 4), QW-236 (MDM2 exon 11) and TY-70 (MDM2 exon 12). Primers NX30 and SC205 amplify an 800 bp band, and QW-236 and TY-70 amplify two bands, 220 bp from the transgene and 582 bp from the endogenous mdm2 genomic sequence.

Histology and IHC of mouse skin

Skin samples from transgenic and wild-type mice, matched with respect to age, gender and body site, were fixed in freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) overnight at 4°C, dehydrated with Histolemon (Carlo Erba), immersed in liquid paraffin overnight and embedded in moulds. Sections (6 µm) were used for normal histological analysis by staining in haematoxylin and eosin, or for IHC. Sections for high temperature unmasking were mounted on Superfrost Plus (Labonard, France) slides and incubated at 37°C overnight and then at 60°C for 1 h.

High temperature unmasking protocol for endogenous MDM2, p53 and Ki-67

The slides were deparaffinized and rehydrated; endogenous peroxidase was quenched as described for keratin IHC (see below). The slides were boiled in 0.01 M citrate buffer (pH 6) for 20 min in a microwave oven and blocked in 4% bovine serum albumin in PBS. They were then incubated with antibodies (anti-MDM2 #364, 1 in 200; anti-p53 NCL-p53-CM5, 1 in 1000; or anti-Ki-67 NCL-Ki-67, 1 in 1000). The slides were incubated for 3 h at room temperature and then treated as for the keratin markers.

IHC for K14, K10 and K6

The slides were deparaffinized, rehydrated and incubated with primary antibodies from Babco (anti-K14 PRB-155P, dilution 1 in 1000; or anti-K10 PRB-159P and anti-K6 PRB-169P, dilution 1 in 500) for 3–4 h. They were then incubated with the secondary antibody [biotin-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson Laboratories), dilution 1 in 200] followed by streptavidin peroxidase (1 in 200) and revealed with DAB liquid substrate kit (Zymed) for 5 min, counterstained with haematoxylin and analysed by light microscopy.

BrdU labelling and detection

Six-day-old mice were injected subcutaneously with 60 µg of BrdU per gram of body weight and killed 2 h later. Skin samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and embedded in paraffin. Sections (6 µm) were used for IHC with the BrdU staining kit (Zymed).

TUNEL assay for apoptosis

Paraffin sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated and analysed for DNA fragments using the Apoptag Plus peroxidase in situ apoptosis detection kit (Intergen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Western blots

Skin samples were homogenized in RIPA buffer using an Ultrathorax. Homogenates (200 µg) were analysed by 10% SDS–PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The filters were incubated with the rabbit polyclonal anti-MDM2 antibody (#364) overnight at 4°C, then with peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson Laboratories; 1 in 200 dilution) and visualized by an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Pierce).

In situ hybridization

Frozen sections (10 µm) were analysed by in situ hybridization using a 35S-labelled antisense riboprobe corresponding to 1.5 kb of the MDM2 cDNA. After hybridization, emulsion dip, exposure and developing, the sections were examined with a microscope under bright- and dark-field illumination (Niederreither and Dolle, 1998).

RT–PCR

Total RNA was prepared from different organs that were homogenized in the Trizol reagent (Gibco-BRL) with an Ultrathorax. Equal amounts of RNA (5 µg) were subjected to RT–PCR. The primers NX 30 (β-globin exon sequence) and SC205 (MDM2 exon 4) give a 225 bp product for the transgene, and RP-165 and SC205 give a 190 bp product for endogenous MDM2. The products were analysed on 6% acrylamide gels.

Chemical carcinogenesis

Eight-week-old female mice were shaved with an A4 clipper; 1 week later, the mice were given the initiator DMBA (25 µg/200 µl of acetone) once and then were given the tumour promoter TPA (10 µg) twice a week for 15 weeks. Acetone alone was used as a control. The animals were then observed every 2 weeks for the appearance of papillomas and tumours.

UV irradiation

Mice were irradiated inside a UV box that had four 40 W FL40SE fluorescent sun lamps (Sankyo Denki Co. Ltd). The rate of UVB (285–350 nm) irradiation was 1 mW/cm2, as measured at the level of the two metal platforms inside the box with a Type I UV meter (Waldmann Medical Division, Herbert Waldmann GmbH). The mice received a total dose of 5000 J/m2.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank J.-P.Ghnassia for pathological examination of the lesions, M.Alkhalaf for his early contribution to this work, K.Niederreither and P.Dollé for help with the in situ hybridizations, S.Werner for the gift of PHR2, Arup Indra for critical reading of the manuscript, M.Le Meur, R.Matyas, A.Collet and many other members of the IGBMC facilities’ staff for invaluable help. We thank BioAvenir (Rhône-Poulenc), the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, the Hôpital Universitaire de Strasbourg, the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer, the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale, the Ligue Nationale Française contre le Cancer, the Ligue Régionale (Haut-Rhin) contre le Cancer and the Ligue Régionale (Bas-Rhin) contre le Cancer for financial assistance.

References

- Alkhalaf M., Ganguli,G., Messaddeq,N., Le Meur,M. and Wasylyk,B. (1999) MDM2 overexpression generates a skin phenotype in both wild type and p53 null mice. Oncogene, 18, 1419–1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almog N. and Rotter,V. (1997) Involvement of p53 in cell differentiation and development. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1333, F1–F27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ananthaswamy H.N., Loughlin,S.M., Ullrich,S.E. and Kripke,M.L. (1998) Inhibition of UV-induced p53 mutations by sunscreens: implications for skin cancer prevention. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc., 3, 52–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg R.J., van Kranen,H.J., Rebel,H.G., de Vries,A., van Vloten,W.A., Van Kreijl,C.F., van der Leun,J.C. and de Gruijl,F.R. (1996) Early p53 alterations in mouse skin carcinogenesis by UVB radiation: immunohistochemical detection of mutant p53 protein in clusters of preneoplastic epidermal cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 274–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahilly-Snyder L., Yang-Feng,T., Francke,U. and George,D.L. (1987) Molecular analysis and chromosomal mapping of amplified genes isolated from a transformed mouse 3T3 cell line. Somat. Cell Mol. Genet., 13, 235–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan E.F., Gat,U., McNiff,J.M. and Fuchs,E. (1999) A common human skin tumour is caused by activating mutations in β-catenin. Nature Genet., 21, 410–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulombe P.A., Kopan,R. and Fuchs,E. (1989) Expression of keratin K14 in the epidermis and hair follicle: insights into complex programs of differentiation. J. Cell Biol., 109, 2295–2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coussens L.M., Hanahan,D. and Arbeit,J.M. (1996) Genetic predisposition and parameters of malignant progression in K14-HPV16 transgenic mice. Am. J. Pathol., 149, 1899–1917. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dazard J.E., Augias,D., Neel,H., Mils,V., Marechal,V., Basset-Seguin,N. and Piette,J. (1997) MDM-2 protein is expressed in different layers of normal human skin. Oncogene, 14, 1123–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert R.L., Crish,J.F. and Robinson,N.A. (1997) The epidermal keratinocyte as a model for the study of gene regulation and cell differentiation. Physiol. Rev., 77, 397–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el-Deiry W.S. et al. (1993) WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell, 75, 817–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakharzadeh S.S., Trusko,S.P. and George,D.L. (1991) Tumorigenic potential associated with enhanced expression of a gene that is amplified in a mouse tumor cell line. EMBO J., 10, 1565–1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang S., Jensen,J.P., Ludwig,R.L., Vousden,K.H. and Weissman,A.M. (2000) Mdm2 is a RING finger-dependent ubiquitin protein ligase for itself and p53. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 8945–8951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiddler T.A., Smith,L., Tapscott,S.J. and Thayer,M.J. (1996) Amplification of MDM2 inhibits MyoD-mediated myogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol., 16, 5048–5057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay C.A. (1993) The mdm-2 oncogene can overcome wild-type p53 suppression of transformed cell growth. Mol. Cell. Biol., 13, 301–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman D.A. and Levine,A.J. (1998) Nuclear export is required for degradation of endogenous p53 by MDM2 and human papillomavirus E6. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 7288–7293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman D.A., Wu,L. and Levine,A.J. (1999) Functions of the MDM2 oncoprotein. Cell. Mol. Life Sci., 55, 96–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs E. (1995) Keratins and the skin. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol., 11, 123–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs E. and Green,H. (1980) Changes in keratin gene expression during terminal differentiation of the keratinocyte. Cell, 19, 1033–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh D.A., Rothnagel,J.A., Quintanilla,M.I., Orengo,C.C., Gagne,T.A., Bundman,D.S., Longley,M.A. and Roop,D.R. (1993) Induction of epidermal hyperplasia, hyperkeratosis and papillomas in transgenic mice by a targeted v-Ha-ras oncogene. Mol. Carcinogen., 7, 99–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines D.S. (1997) The mdm2 proto-oncogene. Leuk. Lymph., 26, 227–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall P.A., McKee,P.H., Menage,H.D., Dover,R. and Lane,D.P. (1993) High levels of p53 protein in UV-irradiated normal human skin. Oncogene, 8, 203–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper J.W., Adami,G.R., Wei,N., Keyomarsi,K. and Elledge,S.J. (1993) The p21 Cdk-interacting protein Cip1 is a potent inhibitor of G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Cell, 75, 805–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haupt Y., Maya,R., Kazaz,A. and Oren,M. (1997) Mdm2 promotes the rapid degradation of p53. Nature, 387, 296–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda R. and Yasuda,H. (2000) Activity of MDM2, a ubiquitin ligase, toward p53 or itself is dependent on the RING finger domain of the ligase. Oncogene, 19, 1473–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda R., Tanaka,H. and Yasuda,H. (1997) Oncoprotein MDM2 is a ubiquitin ligase E3 for tumor suppressor p53. FEBS Lett., 420, 25–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M.W. and Berberich,S.J. (2000) MdmX protects p53 from Mdm2-mediated degradation. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 1001–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W., Ananthaswamy,H.N., Muller,H.K. and Kripke,M.L. (1999) p53 protects against skin cancer induction by UV-B radiation. Oncogene, 18, 4247–4253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonason A.S., Kunala,S., Price,G.J., Restifo,R.J., Spinelli,H.M., Persing,J.A., Leffell,D.J., Tarone,R.E. and Brash,D.E. (1996) Frequent clones of p53-mutated keratinocytes in normal human skin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 14025–14029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S.N., Roe,A.E., Donehower,L.A. and Bradley,A. (1995) Rescue of embryonic lethality in Mdm2-deficient mice by absence of p53. Nature, 378, 206–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S.N., Hancock,A.R., Vogel,H., Donehower,L.A. and Bradley,A. (1998) Overexpression of Mdm2 in mice reveals a p53-independent role for Mdm2 in tumorigenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 15608–15612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juven-Gershon T. and Oren,M. (1999) Mdm2: the ups and downs. Mol. Med., 5, 71–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin W.G. Jr (1999) The p53 gene family. Oncogene, 18, 7701–7705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubbutat M.H., Jones,S.N. and Vousden,K.H. (1997) Regulation of p53 stability by Mdm2. Nature, 387, 299–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lain S., Midgley,C., Sparks,A., Lane,E.B. and Lane,D.P. (1999) An inhibitor of nuclear export activates the p53 response and induces the localization of HDM2 and p53 to U1A-positive nuclear bodies associated with the PODs. Exp. Cell Res., 248, 457–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leffell D.J. (2000) The scientific basis of skin cancer. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol., 42, 18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lersch R. and Fuchs,E. (1988) Sequence and expression of a type II keratin, K5, in human epidermal cells. Mol. Cell. Biol., 8, 486–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leveillard T., Gorry,P., Niederreither,K. and Wasylyk,B. (1998) MDM2 expression during mouse embryogenesis and the requirement of p53. Mech. Dev., 74, 189–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levrero M., De Laurenzi,V., Costanzo,A., Gong,J., Wang,J.Y. and Melino,G. (2000) The p53/p63/p73 family of transcription factors: overlapping and distinct functions. J. Cell Sci., 113, 1661–1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohrum M.A. and Vousden,K.H. (2000) Regulation and function of the p53-related proteins: same family, different rules. Trends Cell Biol., 10, 197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren K., Montes de Oca Luna,R., McNeill,Y.B., Emerick,E.P., Spencer,B., Barfield,C.R., Lozano,G., Rosenberg,M.P. and Finlay,C.A. (1997) Targeted expression of MDM2 uncouples S phase from mitosis and inhibits mammary gland development independent of p53. Genes Dev., 11, 714–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills A.A., Zheng,B., Wang,X.J., Vogel,H., Roop,D.R. and Bradley,A. (1999) p63 is a p53 homologue required for limb and epidermal morphogenesis. Nature, 398, 708–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita T. and Reed,J.C. (1995) Tumor suppressor p53 is a direct transcriptional activator of the human bax gene. Cell, 80, 293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momand J., Jung,D., Wilczynski,S. and Niland,J. (1998) The MDM2 gene amplification database. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 3453–3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momand J., Wu,H.H. and Dasgupta,G. (2000) MDM2—master regulator of the p53 tumor suppressor protein. Gene, 242, 15–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montes de Oca Luna R., Wagner,D.S. and Lozano,G. (1995) Rescue of early embryonic lethality in mdm2-deficient mice by deletion of p53. Nature, 378, 203–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson W.G. and Sun,T.T. (1983) The 50- and 58-kDa keratin classes as molecular markers for stratified squamous epithelia: cell culture studies. J. Cell Biol., 97, 244–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederreither K. and Dolle,P. (1998) In situ hybridization with 35S-labeled probes for retinoid receptors. Methods Mol. Biol., 89, 247–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliner J.D., Kinzler,K.W., Meltzer,P.S., George,D.L. and Vogelstein,B. (1992) Amplification of a gene encoding a p53-associated protein in human sarcomas. Nature, 358, 80–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliner J.D., Pietenpol,J.A., Thiagalingam,S., Gyuris,J., Kinzler,K.W. and Vogelstein,B. (1993) Oncoprotein MDM2 conceals the activation domain of tumour suppressor p53. Nature, 362, 857–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oro A.E., Higgins,K.M., Hu,Z., Bonifas,J.M., Epstein,E.H.,Jr and Scott,M.P. (1997) Basal cell carcinomas in mice overexpressing sonic hedgehog. Science, 276, 817–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouhtit A., Muller,H.K., Davis,D.W., Ullrich,S.E., McConkey,D. and Ananthaswamy,H.N. (2000) Temporal events in skin injury and the early adaptive responses in ultraviolet-irradiated mouse skin. Am. J. Pathol., 156, 201–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paramio J.M., Lain,S., Segrelles,C., Lane,E.B. and Jorcano,J.L. (1998) Differential expression and functionally co-operative roles for the retinoblastoma family of proteins in epidermal differentiation. Oncogene, 17, 949–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsa R., Yang,A., McKeon,F. and Green,H. (1999) Association of p63 with proliferative potential in normal and neoplastic human keratinocytes. J. Invest. Dermatol., 113, 1099–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picksley S.M., Spicer,J.F., Barnes,D.M. and Lane,D.P. (1996) The p53–MDM2 interaction in a cancer-prone family and the identification of a novel therapeutic target. Acta Oncol., 35, 429–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piette J., Neel,H. and Marechal,V. (1997) Mdm2: keeping p53 under control. Oncogene, 15, 1001–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prives C. (1998) Signaling to p53: breaking the MDM2–p53 circuit. Cell, 95, 5–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinke V., Bortner,D.M., Amelse,L.L., Lundgren,K., Rosenberg,M.P., Finlay,C.A. and Lozano,G. (1999) Overproduction of MDM2 in vivo disrupts S phase independent of E2F1. Cell Growth Differ., 10, 147–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth J., Dobbelstein,M., Freedman,D.A., Shenk,T. and Levine,A.J. (1998) Nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling of the hdm2 oncoprotein regulates the levels of the p53 protein via a pathway used by the human immunodeficiency virus rev protein. EMBO J., 17, 554–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano M. (2000) The INK4a/ARF locus in murine tumorigenesis. Carcinogenesis, 21, 865–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr C.J. and Weber,J.D. (2000) The ARF/p53 pathway. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 10, 94–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soehnge H., Ouhtit,A. and Ananthaswamy,O.N. (1997) Mechanisms of induction of skin cancer by UV radiation. Frontiers Biosci., 2, D538–D551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S. and Lambert,P.F. (1999) Different responses of epidermal and hair follicular cells to radiation correlate with distinct patterns of p53 and p21 induction. Am. J. Pathol., 155, 1121–1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoler A., Kopan,R., Duvic,M. and Fuchs,E. (1988) Use of monospecific antisera and cRNA probes to localize the major changes in keratin expression during normal and abnormal epidermal differentiation. J. Cell Biol., 107, 427–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun P., Dong,P., Dai,K., Hannon,G.J. and Beach,D. (1998) p53-independent role of MDM2 in TGF-β1 resistance. Science, 282, 2270–2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao W. and Levine,A.J. (1999) Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of oncoprotein Hdm2 is required for Hdm2-mediated degradation of p53. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 3077–3080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tron V.A., Trotter,M.J., Ishikawa,T., Ho,V.C. and Li,G. (1998a) p53-dependent regulation of nucleotide excision repair in murine epidermis in vivo. J. Cutan. Med. Surg., 3, 16–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tron V.A., Trotter,M.J., Tang,L., Krajewska,M., Reed,J.C., Ho,V.C. and Li,G. (1998b) p53-regulated apoptosis is differentiation dependent in ultraviolet B-irradiated mouse keratinocytes. Am. J. Pathol., 153, 579–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tron V.A., Li,G., Ho,V. and Trotter,M.J. (1999) Ultraviolet radiation-induced p53 responses in the epidermis are differentiation-dependent. J. Cutan. Med. Surg., 3, 280–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassar R. and Fuchs,E. (1991) Transgenic mice provide new insights into the role of TGF-α during epidermal development and differentiation. Genes Dev., 5, 714–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassar R., Rosenberg,M., Ross,S., Tyner,A. and Fuchs,E. (1989) Tissue-specific and differentiation-specific expression of a human K14 keratin gene in transgenic mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 86, 1563–1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassar R., Hutton,M.E. and Fuchs,E. (1992) Transgenic overexpression of transforming growth factor α bypasses the need for c-Ha-ras mutations in mouse skin tumorigenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol., 12, 4643–4653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Russell,J.L. and Johnson,D.G. (2000) E2F4 and E2F1 have similar proliferative properties but different apoptotic and oncogenic properties in vivo. Mol. Cell Biol., 20, 3417–3424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Zinkel,S., Polonsky,K. and Fuchs,E. (1997) Transgenic studies with a keratin promoter-driven growth hormone transgene: prospects for gene therapy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 219–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg W.C., Azzoli,C.G., Chapman,K., Levine,A.J. and Yuspa,S.H. (1995) p53-mediated transcriptional activity increases in differentiating epidermal keratinocytes in association with decreased p53 protein. Oncogene, 10, 2271–2279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss R.A., Eichner,R. and Sun,T.T. (1984) Monoclonal antibody analysis of keratin expression in epidermal diseases: a 48- and 56-kdalton keratin as molecular markers for hyperproliferative keratinocytes. J. Cell Biol., 98, 1397–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W., Wu,X., Chow,L.T., Chin,E., Paterson,A.J. and Kudlow,J.E. (1998) Targeted expression of activated erbB-2 to the epidermis of transgenic mice elicits striking developmental abnormalities in the epidermis and hair follicles. Cell Growth Differ., 9, 313–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yam C.H., Siu,W.Y., Arooz,T., Chiu,C.H., Lau,A., Wang,X.Q. and Poon,R.Y. (1999) MDM2 and MDMX inhibit the transcriptional activity of ectopically expressed SMAD proteins. Cancer Res., 59, 5075–5078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang A. et al. (1999) p63 is essential for regenerative proliferation in limb, craniofacial and epithelial development. Nature, 398, 714–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler A., Jonason,A.S., Leffell,D.J., Simon,J.A., Sharma,H.W., Kimmelman,J., Remington,L., Jacks,T. and Brash,D.E. (1994) Sunburn and p53 in the onset of skin cancer. Nature, 372, 773–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]