Abstract

Atrioventricular (AV) cushions are the precursors of AV septum and valves. In this study, we examined roles of Smad4 during AV cushion development using a conditional gene inactivation approach. We found that endothelial/endocardial inactivation of Smad4 led to the hypocellular AV cushion defect and that both reduced cell proliferation and increased apoptosis contributed to the defect. Expression of multiple genes critical for cushion development was down-regulated in mutant embryos. In collagen gel assays, the number of mesenchymal cells formed is significantly reduced in mutant AV explants compared to that in control explants, suggesting that the reduction of cushion mesenchyme formation in mutants is unlikely secondary to their gross vasculature abnormalities. Using a previously developed immortal endocardial cell line, we showed that Smad4 is required for BMP signaling- stimulated upregulation of Tbx20 and Gata4. Therefore, our data collectively support the cell-autonomous requirement of endocardial Smad4 in regulating AV cushion development.

Keywords: valvulogenesis, BMP, Smad4, congenital heart disease, atrioventricular cushion

INTRODUCTION

Malformation of cardiac valvuloseptal structures accounts for a large proportion of congenital heart diseases (CHDs), which are the major cause of infant morbidity and mortality, occurring in as many as 1% of newborns (Hoffman, 1995; Hoffman and Kaplan, 2002; Clark et al., 2006; Onuzo, 2006). Valvuloseptal development in the atrioventricular canal (AVC) region is initiated with cushion formation by regional expansion of extracellular matrix (ECM) from both superior and inferior directions at ~E9.0 in mouse embryos (Markwald et al., 1981; Eisenberg and Markwald, 1995). Shortly thereafter, from E9.5 to E10.5, a group of endocardial cells respond to signals released from the myocardium and undergo epithelialmesenchyme-transformation (EMT) to migrate into the ECM. The cellularized AV cushions act as precursors of AV valves and septa to facilitate unidirectional blood flow, and are further matured into the final valvuloseptal structures through complicated remodeling processes (de la Cruz et al., 2001; Barnett and Desgrosellier, 2003; Schroeder et al., 2003; Armstrong and Bischoff, 2004; Gittenberger-de Groot et al., 2005; Person et al., 2005; Butcher and Markwald, 2007; Wagner and Siddiqui, 2007).

Functions of Bone Morphogenic Protein (BMP) signaling during AV cushion development have beenextensively studied in recent years. BMP signals are transduced through heterodimeric complexes of type I and type II serine/threonine kinase receptors (Hogan, 1996; von Bubnoff and Cho, 2001; Kishigami and Mishina, 2005; Miyazono et al., 2010). After formation of the receptor-ligand complex at the cell surface, the type II receptor phosphorylates the type I receptor, which in turn phosphorylates BMP receptor-activated Smads (R-Smads, including Smad1, 5, and 8). Phosphorylated (activated) Smad1/5/8 associate with Smad4 to form an R-Smad/Smad4 complex, which translocates into the nucleus to regulate transcription of target genes. In addition to promoting Smad-mediated transcription, BMP ligands may also transduce signals through “non-canonical” kinase pathways (de Caestecker, 2004; ten Dijke and Hill, 2004; Moustakas and Heldin, 2005).

Two BMP ligand genes, Bmp2 and Bmp4, are expressed in the myocardium of the AVC and are required for normal AV valvuloseptal formation. Myocardial depletion of Bmp2 causes defective specification of the AVC myocardium, severely reduced deposition of ECM into AV cushions, and failure in cellularization of cushions (Ma et al., 2005; Rivera-Feliciano and Tabin, 2006). In the collagen gel system, BMP2 can sufficiently replace the myocardium to stimulate EMT by endocardial cells (Sugi et al., 2004) and enhance mesenchyme migration (Inai et al., 2008), suggesting that BMP2 released from the myocardium can directly act on the endocardial and mesenchymal cells in AV cushions. Myocardial inactivation of Bmp4 leads to a common AV canal defect, phenocopying the cardiac abnormality typically observed in Down syndrome patients (Jiao et al., 2003). This defect is due to reduced proliferation of cushion mesenchymal cells rather than impaired EMT (Jiao et al., 2003).

In addition to manipulating Bmp2/4 ligand levels, BMP receptor genes have also been inactivated in different cardiac cell populations to elucidate the role of BMP signaling in cardiac development. For example, pan-myocardial inactivation of Alk3 (Bmpr1a), which encodes a BMP specific type I receptor, led to hypoplastic AV cushions (Gaussin et al., 2002). In addition, specific inactivation of Alk3 in the AVC myocardium caused defects in maturation of AV valves (Gautschi et al., 2008). Moreover, depletion of Alk3 from the endothelium reduced cushion mesenchyme formation to ~20% of the normal level (Ma et al., 2005; Park et al., 2006; Rivera-Feliciano and Tabin, 2006; Song et al., 2007a). Endothelial inactivation of Alk2, which encodes a type I receptor mediating both BMP and TGFβ signals (de Caestecker, 2004), has also been shown to reduce EMT in AV cushions (Wang et al., 2005).

Smad4 encodes a critical transcriptional co-activator of BMP R-Smads. In addition, Smad4 interacts with TGFβ R-Smads (including Smad2 and 3) to co-activate TGFβ downstream target genes. Recent studies from our group and others have demonstrated that Smad4 plays important roles in regulating development of the cardiovascular system, which includes myocardial wall morphogenesis, cardiac neural crest cell development, and vasculature formation (Park et al., 2006; Jia et al., 2007; Ko et al., 2007; Lan et al., 2007; Qi et al., 2007; Song et al., 2007b; Nie et al., 2008). Nevertheless, the role of Smad4 during AV cushion development has not been conclusively determined. Our current study establishes the cell-autonomous requirement of Smad4 in endocardial cells to promote normal AV cushion cellularization.

RESULTS

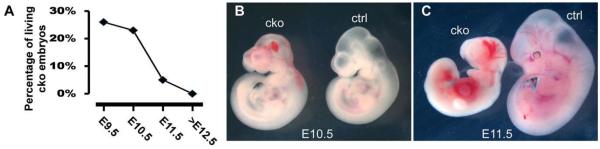

Endothelial Inactivation of Smad4 Causes Embryonic Lethality at Midgestation

To circumvent the early embryonic lethality of Smad4−/− mice (Sirard et al., 1998; Takaku et al., 1998; Yang et al., 1998; Chu et al., 2004), and to study the role of Smad4 during AV cushion development, we specifically inactivated Smad4 from endocardial/endothelial cells using Tie1-Cre (Gustafsson et al., 2001) and Smad4loxP/loxP (Yang et al., 2002) mouse lines. Tie1-Cre specifically inactivates target genes in pan-endothelial (including endocardial) cells starting from ~E9.5, when AV cushion mesenchymal cells are initially derived from endocardial cells (Gustafsson et al., 2001; Song et al., 2007a). We first crossed Tie1-Cre mice with Smad4loxP/loxP mice to obtain Tie1-Cre; Smad4+/loxP male mice, which were further crossed with Smad4loxP/loxP female mice to acquire conditional knockout mutant animals (Tie1-Cre; Smad4loxP/loxP).

No mutant animals were recovered at the P0 stage (from 6 litters), indicating that endothelial inactivation of Smad4 causes embryonic lethality. We then isolated embryos from E9.5 to E19.5 and determined the ratio of live mutant embryos to total embryos. The number of mutant embryos at E9.5 and 10.5 stages was consistent with the expected Mendelian ratio (25%), while at E11.5, less than 10% of total embryos were mutants, indicating that embryonic lethality occurs between E10.5 and E11.5 (Fig. 1A). Very few mutant embryos were able to survive beyond E12.5. Gross examination did not reveal any visible growth defects in E9.5 mutant embryos (data not shown). However, while mutants were similar in size to the controls at E10.5 (Fig. 1B), ~50% of them showed hemorrhage in the embryonic head region (Fig. 1B). This defect is likely due to maldevelopment of vasculature structures caused by pan-endothelial inactivation of Smad4, as previously reported (Park et al., 2006; Lan et al., 2007). At E11.5, internal hemorrhage was visible throughout the mutant embryos and growth arrest was clearly evident, when compared to controls (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Endocardial inactivation of Smad4 leads to embryonic lethality. Tie1-Cre; Smad4loxP/+ male mice were crossed with Smad4loxP/loxP female mice to obtain mutant embryos (Tie1-Cre; Smad4loxP/loxP) and their littermate controls at different stages. A: The chart shows the percentage of living mutant (Tie1-Cre; Smad4loxP/loxP) embryos isolated at various stages. At E9.5 and E10.5, the ratio of mutant embryos is about ~ 25%, close to the Mendelian ratio. Beginning at E11.5, the number of mutant embryos is dramatically lower than 25%. Very few mutant embryos can survive beyond E12.5. B,C: Gross examination of mutant embryos at E10.5 (B) and E11.5 (C). While the size of mutant embryos is similar to controls at E10.5, about 50% of them display hemorrhage in the brain area. At E11.5, all examined mutant embryos displayed growth arrest with hemorrhage throughout the whole embryo. cko, conditional knockout (Tie1-Cre; Smad4loxP/loxP); ctrl, control (Smad4loxP/loxP).

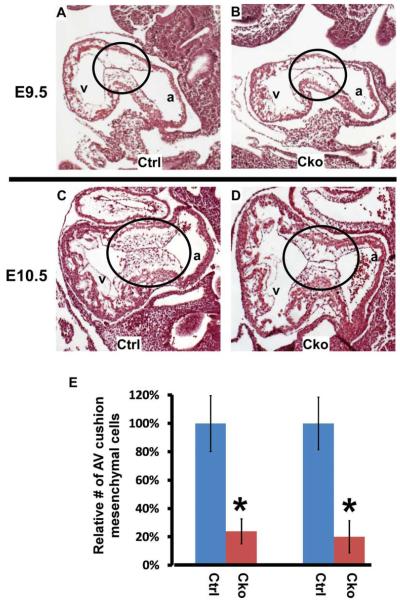

Endocardial Smad4 Is Required for Normal AV Cushion Cellularization

To test the role of endocardial Smad4 in regulating cushion mesenchyme formation, we performed detailed histological examination on mutants and their littermate controls. To minimize the possibility that the observed AV cushion defect was secondary to general growth retardation, only live embryos (with beating hearts) lacking obvious gross abnormalities were included for further analysis. The size of AV cushions was comparable between mutants and controls at E9.5 (Fig. 2A, B), indicating that endocardial Smad4 is not required for expansion of extracellular matrix at the AV canal region. This result is consistent with previous studies showing that the extracellular matrix proteins in AV cushions are predominantly secreted from the myocardium (Markwald et al., 1981; Eisenberg and Markwald, 1995). Mutant embryos displayed severe hypocellular AV cushion defects at both E9.5 and E10.5 stages, while no obvious defect was observed in the myocardial walls (Fig. 2A–D). Quantitative analysis indicated that the number of AV cushion mesenchymal cells in mutants was reduced to ~20% of that in controls at both E9.5 and E10.5 stages (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

Endothelial/endocardial expression of Smad4 is required for normal cellularization of AV cushions. A–D: Control (A, C) and mutant (B, D) embryos at E9.5 (A, B) and E10.5 (C, D) were sagittally sectioned and HE stained. The AV cushions from mutant embryos display a visible hypocellular defect. The circled areas refer to AV cushions. E: To quantitatively determine the extent of reduction in AV cushion mesenchymal cells caused by endocardial inactivation of Smad4, the total number of mesenchymal cells was determined by counting all sections covering the AVC region. The number of control hearts was set at 100%. Data were averaged from 3 embryos of each genotype. The error bar indicates the Standard Deviation (SD). *P < 0.01 (Student’s t-test). a, atria; v, ventricle; cko, conditional knockout (Tie1-Cre; Smad4loxP/loxP); ctrl, control (Smad4loxP/loxP).

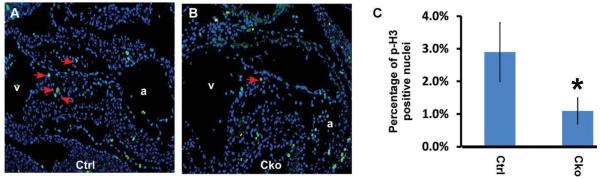

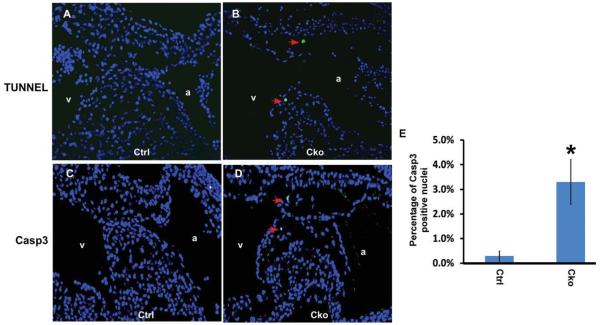

Smad4 Is Required for Proper Proliferation and Survival of Cushion Mesenchymal Cells

To test whether reduced cell proliferation contributed to the hypocellular AV cushion defects observed in mutant embryos, we immunostained embryonic sections with an anti-phospho-Histone His3 antibody. As shown in Figure 3, the number of mesenchymal cells at the M phase was reduced to ~1% in mutant embryos compared to ~3% in controls. This result indicates that Smad4 is required for normal proliferation of cushion mesenchymal cells. We next performed TUNEL assays to determine the contribution of cell death to the cushion defects. As shown in Figure 4A, B, TUNEL-positive cells were clearly detected in mutant AV cushions, while few, if any, such cells could be detected in littermate control cushions. We further demonstrated that the increased cell death was due to apoptosis rather than necrosis through immunostaining embryonic sections with an antibody against cleaved Casp 3 (Fig. 4C, D). Our quantification analysis confirmed that the number of cells undergoing apoptosis was significantly increased in mutant embryos (Fig. 4E). Therefore, we concluded that Smad4 is required for normal survival of cushion mesenchymal cells.

Fig. 3.

Smad4 is required for normal proliferation of cushion mesenchymal cells. A,B: Control (A) and mutant (B) embryos at E10.5 were sagittally sectioned and subjected to immunostaining using an antibody against phospho-Histone H3. Signals were visualized with an Alexa Fluor-488 conjugated secondary antibody (green). Total nuclei were visualized with DAPI staining (blue). Arrows indicate examples of positively stained nuclei in AV cushions. C: Quantitative analysis of cell proliferation in control and mutant AV cushions. Data were averaged from four independent embryos of each genotype, and at least 200 nuclei were counted for each embryo. Error bars indicate SD. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t-test). a, atria; v, ventricle; cko, conditional knockout (Tie1-Cre; Smad4loxP/loxP); ctrl, control (Smad4loxP/loxP).

Fig. 4.

Smad4 is required for normal survival of cushion mesenchymal cells. A,B: Control (A) and mutant (B) embryos at E10.5 were sagittally sectioned and subjected to TUNEL analysis using the Dead End Fluorescence TUNEL system (Promega). Total nuclei were visualized with DAPI staining (blue). Arrows indicate examples of TUNEL-positive nuclei. C,D: Control (C) and mutant (D) embryonic sections (E10.5) were immunostained with an antibody against cleaved Casp3. Signals were visualized with an Alexa Fluor-488 conjugated secondary antibody (green). Total nuclei were visualized with DAPI staining (blue). Arrows indicate examples of positively stained nuclei in AV cushions. E: Quantitative analysis of cell apoptosis in control and mutant AV cushions. Data were averaged from four independent embryos of each genotype, and at least 200 nuclei were counted for each embryo. Error bars indicate SD. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t-test). a, atria; v, ventricle; cko, conditional knockout (Tie1-Cre; Smad4loxP/loxP); ctrl, control (Smad4loxP/loxP).

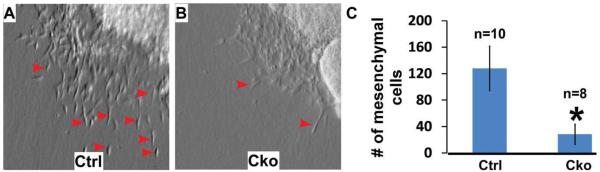

Smad4 Is Required for Normal EMT in Collagen Gel Assays

To test whether Smad4 is required for normal EMT, we performed ex vivo collagen gel assays, which have been widely applied to study EMT in AV cushions of chicken and mouse embryonic hearts (Bernanke and Markwald, 1982; Camenisch et al., 2002; Sugi et al., 2004; Song et al., 2007a). In control explants, mesenchymal cells were readily detected after 48 hr of ex vivo culturing (Fig. 5A), while significantly fewer mesenchymal cells were observed in mutant explants (Fig. 5B). Further quantitative analysis indicated that the number of mesenchymal cells formed in mutant explants was reduced to ~20% of that in control ones. We, therefore, conclude that Smad4 is required for normal mesenchyme formation in AV explants.

Fig. 5.

Smad4 is required for normal mesenchyme formation on ex vivo explants. A,B: Ex vivo collagen gel analysis was performed with control (A) and mutant (B) AV explants at E9.25, as described in Camenisch et al. (2002) and Song et al. (2007a). Fewer mesenchymal cells were formed in mutant explants. Examples of transformed cells (elongated and separated from other cells) are indicated with red arrows. C: The number of transformed cells in both control (n=10) and mutant explants (n=8) was counted under a light microscope. Data are shown as mean ± SD. *P < 0.01 (Student’s t-test). cko, conditional knockout (Tie1-Cre; Smad4loxP/loxP); ctrl, control (Smad4loxP/loxP).

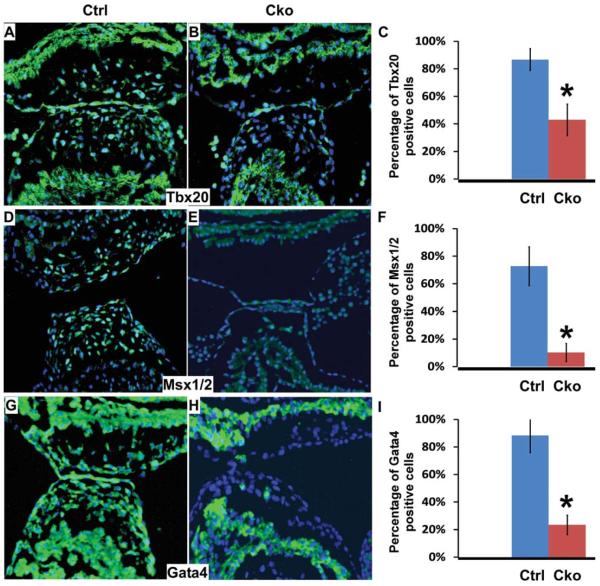

Smad4 Is Required for Normal Expression of Genes Involved in Regulating AV Cushion Development

To begin to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying the AV cushion defect in mutant embryos, we performed immunofluorescence staining assays to evaluate the expression of Tbx20, Msx1/2, and Gata4 in AV cushions at E10.5. Previous studies have demonstrated that these genes are involved in regulating AV cushion development (Rivera-Feliciano et al., 2006; Rivera-Feliciano and Tabin, 2006; Shelton and Yutzey, 2007; Song et al., 2007a; Chen et al., 2008). As shown in Figure 6, expression of these genes was visibly down-regulated in AV cushions of mutant embryos when compared to those of littermate controls. Further quantitative analysis confirmed that this reduction is statistically significant. These data indicate that Smad4 acts upstream of these genes to activate their expression during formation of AV cushion mesenchymal cells.

Fig. 6.

Expression of multiple genes involved in AV cushion development is reduced by endothelial/endocardial inactivation of Smad4. Sections of control and mutant embryos (E10.5) were immunostained with antibodies against Tbx20 (A, B), Msx1/2 (D, E), and Gata4 (G, H). Signals were visualized with an Alexa Fluor-488 conjugated secondary antibody (green). Total nuclei were visualized with DAPI staining (blue). C, F, I: The percentage of positively stained nuclei within AV cushions for Tbx20, Msx1/2, and Gata4, respectively. Data were averaged from at least 3 embryos of each genotype. Data are shown as mean ± SD. *P < 0.01 (Student;s t-test). Cko, conditional knockout (Tie1-Cre; Smad4loxP/loxP); ctrl, control (Smad4loxP/loxP).

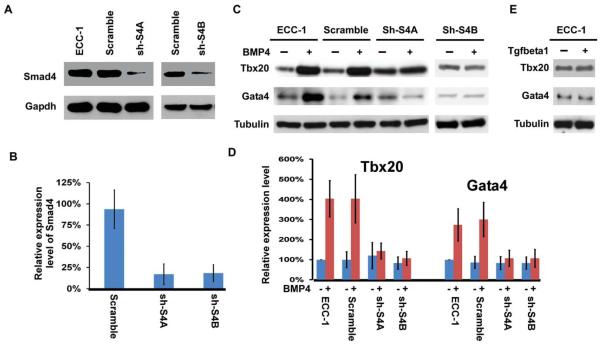

Smad4 Is Required for BMP Signaling–Induced Expression of Tbx20 and Gata4 by Endocardial Cells

Results described above from ex vivo collagen gel analysis (Fig. 5) and molecular marker examination (Fig. 6) suggest the essential cell-autonomous functions of Smad4 in promoting cushion mesenchyme formation from endocardial cells (see Discussion section). We decided to further test this idea using an immortalized endocardial cell line, which has been previously used to study gene regulation during EMT (Zhou et al., 2005). For simplicity, we will refer to this cell line as ECC-1. We purchased 4 shRNA lentiviral constructs that were predesigned to specifically knock down Smad4 expression. Two of the 4 constructs dramatically reduced Smad4 expression to <25% of the control level, while no obvious reduction was observed in cells transduced with the lentiviral construct expressing a scrambled shRNA (Fig. 7A, B). It has been previously demonstrated that BMP ligands can replace the myocardium to activate EMT by endocardial cells on collagen gel assays (Sugi et al., 2004). In support of this idea, BMP4 treatment of ECC-1 cells led to upregulated expression of Tbx20 and Gata4, which are known to regulate mesenchyme formation from endocardial cells (Fig. 7C, D). Knocking down expression of Smad4 in ECC-1 cells did not alter the basal expression of the two genes; however, BMP4-induced upregulation was diminished in cells in which Smad4 had been knocked down (Fig. 7C, D). We also treated ECC-1 cells with TGFβ1 and found that expression of Tbx20 and Gata4 was not altered by such treatment (Fig. 7E), suggesting that upregulated expression of these two genes in ECC-1 cells is specific to BMP stimulation.

Fig. 7.

Smad4 is required for BMP-induced upregulation of Tbx20 and Gata4 in endocardial cells. A,B: ECC-1 cells were transduced with various lentiviral constructs expressing Smad4 targeting shRNAs or a scrambled control shRNA. Western analysis was performed using an anti Smad4 antibody (A). Tubulin was used as a loading control. The band intensity was semi-quantified, and the intensity of Smad4 in ECC-1 cells without viral transduction was set at 100% (B). Data were averaged from 3 independent experiments, and the error bars indicate SD. C,D: ECC-1 cells with various lentiviral constructs were treated with 0 or 100 ng/ml of hBMP4 for 48 hr. Western analysis was performed using antibodies against Tbx20 or Gata4 (C). Tubulin was used as a loading control. Band intensities were semi-quantified, and the intensity of Tbx20 or Gata4 in ECC-1 cells in the absence of BMP4 stimulation was set at 100%. Data were averaged from 3 independent experiments with error bars indicating SD. E: ECC-1 cells were treated with 0 or 5 ng/ml TGFβ1 for 48 hr followed by Western analysis to examine expression of Tbx20 and Gata4. TGFβ treatment did not apparently alter the expression level of Tbx20 and Gata4.

DISCUSSION

The focus of this study was to determine the function of endocardial Smad4 during AV cushion development. We utilized multiple complementary model systems to demonstrate the cell-autonomous requirement of endocardial Smad4 in promoting mesenchyme formation in AV cushions of mouse embryos.

Our in vivo mouse genetic studies showed that endothelial inactivation of Smad4 leads to severe hypocellular AV cushion defects. Two previous elegant studies applying a similar conditional gene inactivation approach clearly established the critical role of Smad4 in the endothelium to regulate vasculature remodeling and integrity (Park et al., 2006; Lan et al., 2007). Both groups noticed the hypocellular AV cushion defect in mutant embryos; however, this defect has not been characterized in detail. Furthermore, in both studies, the mutant embryos used for histological examination of the AV cushion region displayed growth retardation and apparent myocardial wall defects (Park et al., 2006; Lan et al., 2007). It is thus difficult to exclude that the hypocellular cushion defect is secondary to the overall growth delay/arrest in mutant embryos caused by pan-endothelial inactivation of Smad4. The focus of our current study was to characterize the AV cushion defect in detail at both the histological and molecular levels. To minimize the possibility that the observed cushion defect was due to gross endothelial vascular abnormalities, we only included embryos lacking obvious gross abnormalities for further examination of the AV canal region. These mutant embryos appeared to have normal myocardial walls, but displayed severe cushion defects (Fig. 2), supporting the essential cell-autonomous role of endocardial Smad4 during AV cushion development.

To complement the in vivo genetic assays, we further examined the function of Smad4 in ex vivo cultured AV explants and in in vitro cultured ECC-1 endocardial cells. We showed that in the collagen gel assay, the number of mesenchymal cells formed in mutant explants is reduced to ~20% of that in controls, comparable to the reduction observed in mutant embryonic hearts (Fig. 5). One great advantage of the collagen gel system is that once placed on the gel, the mutant and control AV tissues are exposed to identical culture medium, and thus formation of mesenchymal cells ex vivo will be relatively independent of developmental processes in other embryonic areas. Therefore, the result from our collagen gel assay strongly supports the direct role of Smad4 in AV cushion endocardial cells. This conclusion is further substantiated by our in vitro cell culture assays using the ECC-1 endocardial cells, which are free from other cell types. Using this cell culture system, we showed that Smad4 is required for BMP4-induced upregulation of expression of EMT regulatory genes including Tbx20 and Gata4.

Smad4 has long been known to play critical roles in mediating activities of Tgfβ/BMP signaling during numerous biological/pathological processes (Feng and Derynck, 2005; Massague et al., 2005; Massague and Gomis, 2006). We recently reported that myocardial Smad4 promotes cardiomyocyte proliferation and survival through upregulation of Nmyc expression. However, many BMP-mediated cardiogenic processes, including AV canal specification, extracellular matrix deposition, and OFT remodeling, are not compromised by myocardial depletion of Smad4 (Song et al., 2007b). The spectrum of abnormalities observed in Alk3 myocardial inactivation embryos appears to be broader than that in Smad4 myocardial inactivation embryos (Gaussin et al., 2005; Song et al., 2007b) (our unpublished observation). These data suggest that many cardiomyogenic activities of BMP signaling are mediated through Smad4-independent pathways. In contrast to myocardial gene inactivation studies, endothelial inactivation of Smad4 led to the AV cushion abnormal phenotype closely resembling that caused by endothelial inactivation of Alk3 and Alk2 (Ma et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2005; Rivera-Feliciano and Tabin, 2006; Song et al., 2007a). We, therefore, speculate that Smad4-dependent transcription plays a central role in mediating BMP activities during AV cushion development. Since Smad4 can also interact with Smad2/3 to activate TGFβ signaling target genes, the mutant cushion phenotype could also be due to the combined effect of loss of both TGFβ and BMP activities in AV cushions.

We showed that expression of multiple genes (including Tbx20, Gata4, and Msx1/2) was down-regulated in Tie1-Cre; Smad4loxP/loxP AV cushions (Fig. 6). Tbx20 was previously demonstrated to play a critical role in promoting proliferation of cushion mesenchymal cells (Shelton and Yutzey, 2007), and endocardial/mesenchymal expression of Tbx20 is reduced in Bmp2 myocardial inactivation embryos (Ma et al., 2005; Rivera-Feliciano and Tabin, 2006). A more recent study showed that Tbx20 is a direct downstream target of BMP R-Smads (Mandel et al., 2010). Our result supports the idea that Smad4 is an essential transcriptional co-activator to activate Tbx20 expression in cushion endocardial and mesenchymal cells. Msx1/2 are also direct BMP downstream effectors that are expressed in AV cushion endocardial/mesenchymal cells during EMT (Bei and Maas, 1998; Bei et al., 2000; Abdelwahid et al., 2002; Gitler et al., 2003; Hussein et al., 2003). Expression of Msx1/2 was reduced in several mouse models with visible hypocellular AV cushion defects, including Nkx2.5-Cre;Bmp2loxP/loxP, Tie2-Cre;Alk2loxP/−, and Tie1-Cre; Alk3loxP/loxP embryos (Ma et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2005; Song et al., 2007a). Msx1−/−;Msx2−/− mutant embryos displayed abnormal endocardial activation and EMT in AV cushions (Chen et al., 2008). Using an antibody recognizing both proteins, we showed that normal expression of Msx1/2 relies on the endocardial expression of Smad4 in mouse embryonic hearts. Interestingly, expression of Msx1/2 in ECC-1 cells is not up-regulated by BMP stimulation (data not shown). This is likely due to the fact that responsiveness of some genes (e.g., Msx1/2) to BMP stimulation is lost in ECC-1 cells during the immortalization process. Gata4 is a critical upstream activator of the Erbb3-Erk pathway, which is required for EMT in the AVC region, and endocardial inactivation of Gata4 severely impaired EMT (Rivera-Feliciano et al., 2006). Expression of Gata4 in AV cushions is decreased by myocardial inactivation of Bmp2 (Rivera-Feliciano and Tabin, 2006). Our data suggests that Smad4 acts as the critical mediator of BMP signaling by activating Gata4. However, it is currently unclear whether Gata4 is a direct downstream target of the BMP/Smad pathway.

In conclusion, we provide multiple lines of convincing evidence to show that Smad4 plays a critical role during AV cushion cellularization, and that the activity of Smad4 is endocardial cell autonomous. Smad4 accomplishes its activities through regulating expression of multiple target genes that play essential roles during AV cushion development. Information acquired from this study will help us to better understand mechanisms of CHDs involving AV valvuloseptal abnormalities.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mouse and Embryo Manipulations

All procedures are approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Tie1-Cre mice (Gustafsson et al., 2001) were crossed with Smad4loxP/loxP mice (Yang et al., 2002) to specifically inactivate Smad4 in endothelial cells. In performing conditional gene inactivation experiments, we always crossed male Tie1-Cre; Smad4loxP/+ mice with female Smad4loxP/loxP mice. Mouse genotyping, embryo dissection, sectioning, and Hematoxylin-Eosin (HE) staining were performed as described previously (Jiao et al., 2002, 2003; Song et al., 2007a; Nie et al., 2008).

Ex Vivo Collagen Gel Assay

Ex vivo collagen gel assays were performed as described previously (Camenisch et al., 2002; Song et al., 2007a). Forty-eight hours after culturing the AV explants on the collagen gel, the number of mesenchymal cells formed was counted under a light microscope.

TUNEL, Immunostaining, and Western Analysis

TUNEL assays were performed using the “Dead End Fluorescence TUNEL system” (Promega, Madison, WI) following manufacturer’s instructions. Immunofluorescence studies were performed as described previously (Song et al., 2007a). Alexa Fluor-488 conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were used for visualization of the signal. Total nuclei were visualized with DAPI staining. Samples were examined with a Leica HC fluorescent microscope equipped with an RT SLIDER digital camera. Western analysis was performed as described (Song et al., 2007b), and signals were detected using ECL (Amersham, Pittsburgh, PA, or Millipore, Billerica, MA) kits. The protein concentration was determined using D/C Protein Assay Reagent (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) following the manufacturer’s instruction. Band intensities were semi-quantified using Scion Image software. The primary antibodies used in this study included antibodies recognizing phospho-Histone-H3 (UpState, Billerica, MA), Smad4, cleaved Casp3 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), Gata4, Tbx20 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), beta tubulin and Msx1/2 (Iowa Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA).

Culture of Endocardial Cells and Knock Down of Smad4 With Short Hairpin RNA (shRNA) Constructs

The immortalized endocardial cell line, ECC-1, was cultured as previously described (Zhou et al., 2005). For cytokine stimulation, cells were treated with 100 ng/ml hBMP4 (R&D, Minneapolis, MN) or 5 ng/ml TGFβ1 (R&D) in medium with 0.5% FBS for 48 hr. Cells were then subjected to Western and/or immunostaining analysis. Four lentiviral shRNA constructs (pre-designed to knock down Smad4) along with a scrambled control shRNA construct were purchased from Open Biosystems (Huntsville, AL). Lentiviral constructs were packaged with the ViralPower packaging mix (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instruction. The cultured cells were transduced with supernatants containing various shRNA lentiviral constructs and selected with 4 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma) for 4–6 weeks to acquire cells with constructs permanently incorporated into their genomes. Western analysis was then performed using an anti-Smad4 antibody (Cell Signaling) to determine which constructs were able to efficiently knock down Smad4 expression.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Chu-xia Deng (NIDDK) for providing Smad4loxP/loxP mice. We thank Cristina Harmelink, Paige DeBenedittis, and Xiaofei Chi for their assistance on the project. This project was supported by Grants from AHA (0535177N and 09GRNT2060268) and NHLBI (R01HL095783-01A1) awarded to K. J.

Grant sponsor: American Heart Association; Grant numbers: 0535177N and 09GRNT2060268; Grant sponsor: NHBLI; Grant number: R01HL095783.

REFERENCES

- Abdelwahid E, Pelliniemi LJ, Jokinen E. Cell death and differentiation in the development of the endocardial cushion of the embryonic heart. Microsc Res Tech. 2002;58:395–403. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong EJ, Bischoff J. Heart valve development: endothelial cell signaling and differentiation. Circ Res. 2004;95:459–470. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000141146.95728.da. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett JV, Desgrosellier JS. Early events in valvulogenesis: a signaling perspective. Birth Defects Res Part C Embryo Today. 2003;69:58–72. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.10006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bei M, Maas R. FGFs and BMP4 induce both Msx1-independent and Msx1-dependent signaling pathways in early tooth development. Development. 1998;125:4325–4333. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.21.4325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bei M, Kratochwil K, Maas RL. BMP4 rescues a non-cell-autonomous function of Msx1 in tooth development. Development. 2000;127:4711–4718. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.21.4711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernanke DH, Markwald RR. Migratory behavior of cardiac cushion tissue cells in a collagen-lattice culture system. Dev Biol. 1982;91:235–245. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(82)90030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher JT, Markwald RR. Valvulogenesis: the moving target. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2007;362:1489–1503. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camenisch TD, Molin DG, Person A, Runyan RB, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, McDonald JA, Klewer SE. Temporal and distinct TGFbeta ligand requirements during mouse and avian endocardial cushion morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2002;248:170–181. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YH, Ishii M, Sucov HM, Maxson RE., Jr Msx1 and Msx2 are required for endothelial-mesenchymal transformation of the atrioventricular cushions and patterning of the atrioventricular myocardium. BMC Dev Biol. 2008;8:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-8-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu GC, Dunn NR, Anderson DC, Oxburgh L, Robertson EJ. Differential requirements for Smad4 in TGFbeta-dependent patterning of the early mouse embryo. Development. 2004;131:3501–3512. doi: 10.1242/dev.01248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark KL, Yutzey KE, Benson DW. Transcription factors and congenital heart defects. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:97–121. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040104.113828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Caestecker M. The transforming growth factor-beta superfamily of receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004;15:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Cruz MV, Markwald RR, Krug EL, Rumenoff L, Sanchez Gomez C, Sadowinski S, Galicia TD, Gomez F, Salazar Garcia M, Villavicencio Guzman L, Reyes Angeles L, Moreno-Rodriguez RA. Living morphogenesis of the ventricles and congenital pathology of their component parts. Cardiol Young. 2001;11:588–600. doi: 10.1017/s1047951101000932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg LM, Markwald RR. Molecular regulation of atrioventricular valvuloseptal morphogenesis. Circ Res. 1995;77:1–6. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng XH, Derynck R. Specificity and versatility in tgf-beta signaling through Smads. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:659–693. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.022404.142018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaussin V, Morley GE, Cox L, Zwijsen A, Vance KM, Emile L, Tian Y, Liu J, Hong C, Myers D, Conway SJ, Depre C, Mishina Y, Behringer RR, Hanks MC, Schneider MD, Huylebroeck D, Fishman GI, Burch JB, Vatner SF. Alk3/Bmpr1a receptor is required for development of the atrioventricular canal into valves and annulus fibrosus. Circ Res. 2005;97:219–226. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000177862.85474.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaussin V, Van de Putte T, Mishina Y, Hanks MC, Zwijsen A, Huylebroeck D, Behringer RR, Schneider MD. Endocardial cushion and myocardial defects after cardiac myocyte- specific conditional deletion of the bone morphogenetic protein receptor ALK3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2878–2883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042390499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautschi O, Tepper CG, Purnell PR, Izumiya Y, Evans CP, Green TP, Desprez PY, Lara PN, Gandara DR, Mack PC, Kung HJ. Regulation of Id1 expression by SRC: implications for targeting of the bone morphogenetic protein pathway in cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2250–2258. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitler AD, Lu MM, Jiang YQ, Epstein JA, Gruber PJ. Molecular markers of cardiac endocardial cushion development. Dev Dyn. 2003;228:643–650. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Bartelings MM, Deruiter MC, Poelmann RE. Basics of cardiac development for the understanding of congenital heart malformations. Pediatr Res. 2005;57:169–176. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000148710.69159.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson E, Brakebusch C, Hietanen K, Fassler R. Tie-1-directed expression of Cre recombinase in endothelial cells of embryoid bodies and transgenic mice. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:671–676. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.4.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman JI. Incidence of congenital heart disease: II. Prenatal incidence. Pediatr Cardiol. 1995;16:155–165. doi: 10.1007/BF00794186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman JI, Kaplan S. The incidence of congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1890–1900. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01886-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan BL. Bone morphogenetic proteins: multifunctional regulators of vertebrate development. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1580–1594. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.13.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein SM, Duff EK, Sirard C. Smad4 and beta-catenin co-activators functionally interact with lymphoid-enhancing factor to regulate graded expression of Msx2. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:48805–48814. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305472200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inai K, Norris RA, Hoffman S, Markwald RR, Sugi Y. BMP-2 induces cell migration and periostin expression during atrioventricular valvulogenesis. Dev Biol. 2008;315:383–396. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Q, McDill BW, Li SZ, Deng C, Chang CP, Chen F. Smad signaling in the neural crest regulates cardiac outflow tract remodeling through cell autonomous and non-cell autonomous effects. Dev Biol. 2007;311:172–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.08.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao K, Zhou Y, Hogan BL. Identification of mZnf8, a mouse Kruppel-like transcriptional repressor, as a novel nuclear interaction partner of Smad1. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7633–7644. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.21.7633-7644.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao K, Kulessa H, Tompkins K, Zhou Y, Batts L, Baldwin HS, Hogan BL. An essential role of Bmp4 in the atrioventricular septation of the mouse heart. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2362–2367. doi: 10.1101/gad.1124803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishigami S, Mishina Y. BMP signaling and early embryonic patterning. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:265–278. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko SO, Chung IH, Xu X, Oka S, Zhao H, Cho ES, Deng C, Chai Y. Smad4 is required to regulate the fate of cranial neural crest cells. Dev Biol. 2007;312:435–447. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan Y, Liu B, Yao H, Li F, Weng T, Yang G, Li W, Cheng X, Mao N, Yang X. Essential role of endothelial Smad4 in vascular remodeling and integrity. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:7683–7692. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00577-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Lu MF, Schwartz RJ, Martin JF. Bmp2 is essential for cardiac cushion epithelial-mesenchymal transition and myocardial patterning. Development. 2005;132:5601–5611. doi: 10.1242/dev.02156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel EM, Kaltenbrun E, Callis TE, Zeng XX, Marques SR, Yelon D, Wang DZ, Conlon FL. The BMP pathway acts to directly regulate Tbx20 in the developing heart. Development. 2010;137:1919–1929. doi: 10.1242/dev.043588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markwald RR, Krook JM, Kitten GT, Runyan RB. Endocardial cushion tissue development: structural analyses on the attachment of extracellular matrix to migrating mesenchymal cell surfaces. Scan Electron Microsc. 1981:261–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massague J, Gomis RR. The logic of TGFbeta signaling. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:2811–2820. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massague J, Seoane J, Wotton D. Smad transcription factors. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2783–2810. doi: 10.1101/gad.1350705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazono K, Kamiya Y, Morikawa M. Bone morphogenetic protein receptors and signal transduction. J Biochem. 2010;147:35–51. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvp148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moustakas A, Heldin CH. Non-Smad TGF-beta signals. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3573–3584. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie X, Deng CX, Wang Q, Jiao K. Disruption of Smad4 in neural crest cells leads to mid-gestation death with pharyngeal arch, craniofacial and cardiac defects. Dev Biol. 2008;316:417–430. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onuzo OC. How effectively can clinical examination pick up congenital heart disease at birth? Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2006;91:F236–237. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.094789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C, Lavine K, Mishina Y, Deng CX, Ornitz DM, Choi K. Bone morphogenetic protein receptor 1A signaling is dispensable for hematopoietic development but essential for vessel and atrioventricular endocardial cushion formation. Development. 2006;133:3473–3484. doi: 10.1242/dev.02499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Person AD, Klewer SE, Runyan RB. Cell biology of cardiac cushion development. Int Rev Cytol. 2005;243:287–335. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(05)43005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi X, Yang G, Yang L, Lan Y, Weng T, Wang J, Wu Z, Xu J, Gao X, Yang X. Essential role of Smad4 in maintaining cardiomyocyte proliferation during murine embryonic heart development. Dev Biol. 2007;311:136–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Feliciano J, Tabin CJ. Bmp2 instructs cardiac progenitors to form the heart-valve-inducing field. Dev Biol. 2006;295:580–588. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Feliciano J, Lee KH, Kong SW, Rajagopal S, Ma Q, Springer Z, Izumo S, Tabin CJ, Pu WT. Development of heart valves requires Gata4 expression in endothelial-derived cells. Development. 2006;133:3607–3618. doi: 10.1242/dev.02519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JA, Jackson LF, Lee DC, Camenisch TD. Form and function of developing heart valves: coordination by extracellular matrix and growth factor signaling. J Mol Med. 2003;81:392–403. doi: 10.1007/s00109-003-0456-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton EL, Yutzey KE. Tbx20 regulation of endocardial cushion cell proliferation and extracellular matrix gene expression. Dev Biol. 2007;302:376–388. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirard C, de la Pompa JL, Elia A, Itie A, Mirtsos C, Cheung A, Hahn S, Wakeham A, Schwartz L, Kern SE, Rossant J, Mak TW. The tumor suppressor gene Smad4/Dpc4 is required for gastrulation and later for anterior development of the mouse embryo. Genes Dev. 1998;12:107–119. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.1.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L, Fassler R, Mishina Y, Jiao K, Baldwin HS. Essential functions of Alk3 during AV cushion morphogenesis in mouse embryonic hearts. Dev Biol. 2007a;301:276–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L, Yan W, Chen X, Deng CX, Wang Q, Jiao K. Myocardial Smad4 is essential for cardiogenesis in mouse embryos. Circ Res. 2007b;101:277–285. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.155630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugi Y, Yamamura H, Okagawa H, Markwald RR. Bone morphogenetic protein-2 can mediate myocardial regulation of atrioventricular cushion mesenchymal cell formation in mice. Dev Biol. 2004;269:505–518. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaku K, Oshima M, Miyoshi H, Matsui M, Seldin MF, Taketo MM. Intestinal tumorigenesis in compound mutant mice of both Dpc4 (Smad4) and Apc genes. Cell. 1998;92:645–656. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Dijke P, Hill CS. New insights into TGF-beta-Smad signalling. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Bubnoff A, Cho KW. Intracellular BMP signaling regulation in vertebrates: pathway or network? Dev Biol. 2001;239:1–14. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner M, Siddiqui MA. Signal transduction in early heart development (II): ventricular chamber specification, trabeculation, and heart valve formation. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2007;232:866–880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Sridurongrit S, Dudas M, Thomas P, Nagy A, Schneider MD, Epstein JA, Kaartinen V. Atrioventricular cushion transformation is mediated by ALK2 in the developing mouse heart. Dev Biol. 2005;286:299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Li C, Xu X, Deng C. The tumor suppressor SMAD4/DPC4 is essential for epiblast proliferation and mesoderm induction in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3667–3672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Li C, Herrera PL, Deng CX. Generation of Smad4/Dpc4 conditional knockout mice. Genesis. 2002;32:80–81. doi: 10.1002/gene.10029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B, Wu B, Tompkins KL, Boyer KL, Grindley JC, Baldwin HS. Characterization of Nfatc1 regulation identifies an enhancer required for gene expression that is specific to pro-valve endocardial cells in the developing heart. Development. 2005;132:1137–1146. doi: 10.1242/dev.01640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]