Abstract

It has long been known that psychopathology can influence social perception, but a 2D framework of mind perception provides the opportunity for an integrative understanding of some disorders. We examined the covariation of mind perception with three subclinical syndromes—autism-spectrum disorder, schizotypy, and psychopathy—and found that each presents a unique mind-perception profile. Autism-spectrum disorder involves reduced perception of agency in adult humans. Schizotypy involves increased perception of both agency and experience in entities generally thought to lack minds. Psychopathy involves reduced perception of experience in adult humans, children, and animals. Disorders are differentially linked with the over- or underperception of agency and experience in a way that helps explain their real-world consequences.

Keywords: morality, empathy, theory of mind, transdiagnostic

Mental disorders can reveal themselves in distortions of social perception. A person with a disorder may have difficulty understanding the goals of others, or in more profound cases, may ascribe life to inanimate objects or entirely fail to recognize mental states at all. Such distorted mind perception not only has consequences for sufferers of disorders and society at large, but may also help in understanding the etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of psychopathology. In this research, we examine three subclinical syndromes associated with interpersonal difficulties: autism-spectrum disorder, schizotypy, and psychopathy. We predicted that each would be characterized by a unique pattern of distorted mind perception.

Traditional approaches to psychopathology often treat individual disorders as separate entities, each with its own signs, symptoms, and etiology. Although this approach has made significant progress in defining and treating psychopathology, this compartmentalization of disorders belies the integrated nature of the mind. More recent research takes a “transdiagnostic” approach, characterizing separate disorders as different impairments of underlying cognitive systems (1). For example, depression, anxiety, and substance abuse all appear to be linked to disturbances of affect (2). We suggest that a number of disorders may be characterized as specific distortions of mind perception, atypical ascriptions of mental capacities to other entities.

Successful interaction with the world requires knowing which entities have minds and which do not. Mind perception can therefore be distorted by overperception (perceiving a nonexistent mind) and underperception (failing to perceive an existent mind). Research suggests that both can be associated with adverse consequences for perceivers and targets, consequences that range from social faux pas to violence and death. For example, the overperception of mind in infants can lead to child abuse (3), but the underperception of mind in adults can lead to the denial of moral rights (4, 5).

Although psychopathology has long been linked to abnormal social perception, recent discoveries provide a unique framework for understanding the link between mental disorders and mind perception. Originally thought to proceed along a single dimension, mind perception has been revealed in a factor-analytic study to occur along independent dimensions of experience (e.g., the capacity for pleasure, fear, hunger) and agency (e.g., the capacity for self-control, planning, memory) (6). Adult humans are typically seen as capable of both experience and agency, whereas children and animals are seen as capable of mainly experience. Gods and robots are seen as capable of mainly agency, and the dead are seen as capable of neither.

These dimensions capture a range of research on both mind perception and morality (7), and similar dimensions surface in studies of stereotyping (8) and the perception of humanness (4). This 2D structure allows for a nuanced understanding of mind perception as it relates to psychopathology, as different disorders may be characterized by the under- or overascription of experience, agency, or both. Furthermore, psychopathologies may be linked to under- and overperception of agency or experience only for certain targets, providing a multidimensional space for understanding psychopathology. We investigate the link between perceptions of mind and three disorders that have been linked to abnormal social function.

Autism Spectrum

The autism spectrum is a clear candidate for distorted mind perception. Previous research finds that those on the autism spectrum have difficulty representing others’ mental states (9); however, the precise nature of this difficulty is not fully characterized. Autism is consistently linked with failures to understand others’ goals and plans (i.e., their agentic mental contents) (10, 11), but there is significant debate about ascriptions of experience. Some studies find deficits in processing others’ emotional states (12), but others find that individuals with autism use emotion-related words similar to matched controls (13) and remain sensitive to the emotional discomfort of others (14). Moreover, although individuals with autism often have difficulty interacting with other people, they interact relatively easily with nonhuman animals (15) and robots (16). This finding would suggest that although the perception of human minds may be impaired, scores on the autism spectrum should be unrelated to the mind ascribed to other entities.

Schizotypy

Research has suggested that schizotypy may be opposite to autism in the domain of social cognition, involving the overattribution of mental states (17). Such promiscuous mind perception may underlie schizotypals’ strange beliefs, magical thinking, and paranoia. Although adult humans are typically ascribed maximum amounts of both agency and experience—creating a ceiling effect that precludes overattributions—nonhuman targets should be ascribed relatively more mind by those higher in schizotypy.

Psychopathy

Psychopathy is characterized by callous affect and interpersonal insensitivity; psychopaths are perhaps best known for manipulating others and committing crimes (18). The cause of their frequently cruel behavior is debated, but one prominent theory suggests that psychopaths lack the ability to empathize with others (19, 20). As empathy requires an understanding of another's emotional states (21), we hypothesized that those high in psychopathic tendencies would fail to perceive experience in those who normally possess this capacity (i.e., humans and animals). Importantly, as experience is linked to the ascription of moral rights (5, 6), its denial would help explain why psychopaths harm both people and animals (22).

Methods

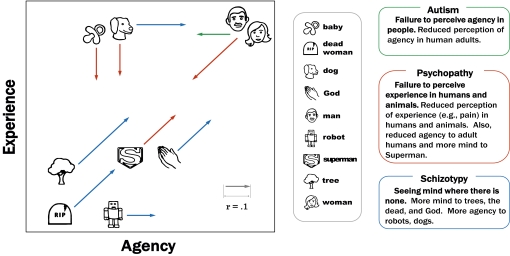

Participants were 890 online survey respondents ranging in age from 18 to 73 (M = 32). Sixty percent were women, and the majority had some college education. Forty-five participants were excluded from analysis for failing to complete the survey or for failing catch items (SI Text). Participants were solicited from internet advertising and undergraduate classes to complete the Mind Survey, where they judged the perceived experience and agency of nine target entities (Fig. 1; also see SI Text). They also completed Web versions of the Autism-spectrum Quotient scale (AQ) (9), the Schizotypy Personality Questionnaire (SPQ-B) (23), and the Self-Report Psychopathy Scale (SPR-III) (24). Because of confidentiality concerns, the “Criminal Behavior” subscale of the SPR-III was not included, and because of the strong association between the SPQ-B “Interpersonal” and “Disordered” subscales and the AQ, r(843) > 0.43, P < 0.001, we exclusively examined Cognitive-Perceptual schizotypy.

Fig. 1.

Targets located by agency and experience factor scores. Vectors represent significant correlations between mind perception and increased severity of disorder (color coded). Horizontal vectors represent variation on agency and vertical vectors represent variation on experience. Diagonal vectors represent variation on both agency and experience. For example, those with higher Autism quotients ascribe less agency to adult humans (r = −0.14). Vectors are scaled to represent the magnitude of correlation.

A confirmatory factor analysis supported dividing mind perception into Agency and Experience, χ2 = 546.53, P < 0.00001 (SI Text). Links between mind perception and psychopathology were investigated by correlating ratings of agency and experience with the three subclinical psychopathology indices. To control for multiple comparisons and the large sample size, only unadjusted correlations above |r = 0.1| were deemed significant (all, df = 843, P < 0.001) (Fig. 1) See SI Text and Table S1 for the complete correlation matrix.

To account for the possible influence of other variables, we examined the link between mind perception and gender, age, and education. Age and education had little effect on mind perception, with the only significant finding being that increased age and education were linked to decreased mind ascription to Superman, A|r (correlation with agency) = −0.21, E|r (correlation with experience) = −0.25. With respect to gender, women ascribed more experience to adult humans (E|r = 0.12), animals (E|r = 0.18), and babies (E|r = 0.18) than men did, potentially stemming from women possessing greater trait empathy (25). Additionally, women ascribed increased agency to God (A|r = 0.14), which is consistent with the relatively higher religiosity of women (26). Reported correlations are adjusted for gender where appropriate.

Results and Discussion

Autism Spectrum.

We found that higher scores on the AQ scale were associated specifically with reduced perceptions of agency in adult humans, A|r = −0.14. This observation suggests that the deficits of autism lie primarily with understanding others’ goals and plans. The lack of association between autism spectrum scores and attributions of experience, E|r = −0.03, suggests that individuals with autism can still empathize with other people. Finally, the lack of distortion in the perception of animals (A|r = −0.02, E|r = −0.05) and robots(A|r = −0.006, E|r = −0.05) is consistent with reports that some people with autism form bonds with these entities despite being disconnected from people (15, 16). Controlling for gender leaves the link between autism spectrum scores and ascription of agency to adult humans largely unchanged (A|r = −0.13), an interesting finding given that autism spectrum scores are generally higher for men (9), as indeed they were in this sample (r = 0.14, P < 0.001).

Schizotypy.

Results confirmed that those higher in schizotypy were primarily characterized by a tendency to indiscriminately perceive mind—that is, to perceive mental capacities where other people typically do not. Whereas ascriptions of mental capacities to human adults were normal for those higher in schizotypy, these individuals ascribed greater experience, agency, or both to entities generally perceived to lack mental capacities: trees, (A|r = 0.19, E|r = 0.22), dead people (A|r = 0.17, E|r = 0.16), robots (A|r = 0.12), and animals (A|r = 0.20). Higher schizotypy scores were also associated with increased attributions of mind to God (A|r = 0.15, E|r = 0.13). Controlling for gender made no difference; there was no apparent relation between gender and schizotypy (r = 0.04, n.s.).

Psychopathy.

Consistent with our hypothesis, higher psychopathy scores were associated with reduced perceptions of experience in those typically ascribed experience. Adult humans (E|r = −0.12), babies (E|r = −0.15), and animals (E|r = −0.14) were all afforded less experience. This result may account for why psychopaths harm these groups; without perceptions of experience, the ascription of moral rights also diminishes (4, 7). Additional regression analyses controlling for gender found that psychopathy remained significantly related to reduced experience ascription, albeit with reduced magnitudes: adult humans (E|r = −0.09), babies (E|r = −0.09), and animals (E|r = −0.08) (all, s > 2.2, P < 0.03). This reduction of effect size likely stems from the link between gender and psychopathy, with males scoring relatively higher, measured in this sample at r = 0.36, P < 0.001. Other significant psychopathy correlations were decreased ascriptions of agency to adult humans (A|r = −0.22) and increased perceptions of mind in Superman (A|r = 0.13, E|r = 0.13). The Superman finding is curious; perhaps psychopaths identify with this invincible hero.

Conclusions

Autism spectrum disorders, schizotypy, and psychopathy each involve abnormalities in social interaction, but analyzing these disorders in terms of ascriptions of agency and experience across a range of targets shows that each has a unique pattern of distorted mind perception. It is worth noting that these findings stem from self-report measures, and that the correlations reported are relatively modest, despite their strong statistical significance. Even small correlations, however, can translate to large effects when considering the extremes of distributions (i.e., those who qualify for clinical diagnoses). Mind perception in clinical populations may be even more distorted if the link between psychopathology and mind perception is nonlinear. Quadratic models designed to explore this possibility did not reveal any systematic nonlinearity, but our study included only a limited number of individuals who surpass the clinical cutoff for each disorder. Future research using clinical samples could test directly for such effects.

The results of this study help to characterize three disorders and highlight the benefits of a transdiagnostic approach (1, 2), whereby disorders are viewed as disturbances of underlying cognitive systems. The findings suggest that mind perception is one such cognitive system that would benefit from future research as it relates to psychopathology. Such research could assist with etiology and treatment; for example, investigating whether recalibrating mind perception also improves other symptoms of these disorders. Most of all, these results suggest that the characterization of psychopathology should focus not only on minds of sufferers, but also on how their minds perceive those of others.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Gray, J. Hromjak, V. Lopez, and B. Simpson. This work was supported in part by National Science Foundation Grant BCS 0841746 and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (K.G.). A.S.H. was supported by the Mind, Brain, and Behavior program.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1015493108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Harvey A, Watkins E, Mansell W, Shafran R. Cognitive Behavioural Processes across Psychological Disorders: A Transdiagnostic Approach to Research and Treatment. 1st Ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kring AM. Emotional disturbances as transdiagnostic processes. In: Lewis M, Haviland-Jones JM, Barrett LF, editors. (2008) Handbook of Emotions. New York: Guildford Press; [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perez-Albeniz A, De Paul J. Empathy and risk status for child physical abuse: The effects of an adult victim's pain cues and an adult victim's intent on aggression. Aggress Behav. 2006;32:421–432. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haslam N. Dehumanization: An integrative review. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2006;10:252–264. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gray K, Wegner DM. Moral typecasting: Divergent perceptions of moral agents and moral patients. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;96:505–520. doi: 10.1037/a0013748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gray HM, Gray K, Wegner DM. Dimensions of mind perception. Science. 2007;315:619. doi: 10.1126/science.1134475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waytz A, Gray K, Epley N, Wegner DM. Causes and consequences of mind perception. Trends Cogn Sci. 2010;14:383–388. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fiske ST, Cuddy AJC, Glick P. Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007;11(2):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Skinner R, Martin J, Clubley E. The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ): Evidence from Asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. J Autism Dev Disord. 2001;31(1):5–17. doi: 10.1023/a:1005653411471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baron-Cohen S. Mindblindness. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leslie AM, Thaiss L. Domain specificity in conceptual development: Neuropsychological evidence from autism. Cognition. 1992;43:225–251. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(92)90013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dapretto M, et al. Understanding emotions in others: Mirror neuron dysfunction in children with autism spectrum disorders. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(1):28–30. doi: 10.1038/nn1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tager-Flusberg H. Autistic children's talk about psychological states: Deficits in the early acquisition of a theory of mind. Child Dev. 1992;63:161–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rogers K, Dziobek I, Hassenstab J, Wolf OT, Convit A. Who cares? Revisiting empathy in Asperger syndrome. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37:709–715. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0197-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pavlides M. Animal-assisted Interventions for Individuals with Autism. Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robins B, Dautenhahn K, Dickerson P. 2009. From isolation to communication: A case study evaluation of robot assisted play for children with Autism with a minimally expressive humanoid robot. In, Advances in Computer-Human Interactions. Second International Conferences on Advances in Computer-Human Interaction, AHI 2009, Feb. 1–7, Cancun, Mexico pp. 205–211. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crespi B, Badcock C. Psychosis and autism as diametrical disorders of the social brain. Behav Brain Sci. 2008;31:241–261. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X08004214. discussion 261–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hare RD. Psychopathy as a risk factor for violence. Psychiatr Q. 1999;70(3):181–197. doi: 10.1023/a:1022094925150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blair RJR. The amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex in morality and psychopathy. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007;11:387–392. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marsh AA, Blair RJ. Deficits in facial affect recognition among antisocial populations: A meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:454–465. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Preston SD, de Waal FBM. Empathy: Its ultimate and proximate bases. Behav Brain Sci. 2002;25:1–20. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x02000018. discussion 20–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hare RD. Without Conscience: The Disturbing World of the Psychopaths Among Us. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raine A, Benishay D. The SPQ-B: A brief screening instrument for schizotypal personality disorder. J Pers Disord. 1995;9:346–355. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paulhus DL, Hemphill J, Hare R. Manual of the Self-Report Psychopathy Scale (SRP-III) Toronto: Multi-Health Systems; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S. The empathy quotient: An investigation of adults with Asperger syndrome or high functioning autism, and normal sex differences. J Autism Dev Disord. 2004;34(2):163–175. doi: 10.1023/b:jadd.0000022607.19833.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vaus DD, McAllister I. Gender differences in religion: A test of the structural location theory. Am Sociol Rev. 1987;52:472–481. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.