Abstract

Several Gram-negative pathogens, including Yersinia pestis, Burkholderia cepacia, and Acinetobacter haemolyticus, synthesize an isosteric analog of 3-deoxy-d-manno-oct-2-ulosonic acid (Kdo), known as d-glycero-d-talo-oct-2-ulosonic acid (Ko), in which the axial hydrogen atom at the Kdo 3-position is replaced with OH. Here we report a unique Kdo 3-hydroxylase (KdoO) from Burkholderia ambifaria and Yersinia pestis, encoded by the bamb_0774 (BakdoO) and the y1812 (YpkdoO) genes, respectively. When expressed in heptosyl transferase-deficient Escherichia coli, these genes result in conversion of the outer Kdo unit of Kdo2-lipid A to Ko in an O2-dependent manner. KdoO contains the putative iron-binding motif, HXDXn>40H. Reconstitution of KdoO activity in vitro with Kdo2-lipid A as the substrate required addition of Fe2+, α-ketoglutarate, and ascorbic acid, confirming that KdoO is a Fe2+/α-ketoglutarate/O2-dependent dioxygenase. Conversion of Kdo to Ko in Kdo2-lipid A conferred reduced susceptibility to mild acid hydrolysis. Although two enzymes that catalyze Fe2+/α-ketoglutarate/O2-dependent hydroxylation of deoxyuridine in fungal extracts have been reported previously, kdoO is the first example of a gene encoding a deoxy-sugar hydroxylase. Homologues of KdoO are found exclusively in Gram-negative bacteria, including the human pathogens Burkholderia mallei, Yersinia pestis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Legionella longbeachae, and Coxiella burnetii, as well as the plant pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum.

Keywords: iron-alpha-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenases, Kdo-hydroxylase, lipopolsaccharide, d-glycero-d-talo-oct-2-ulosonic acid (Ko)

The outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria is an asymmetric lipid bilayer. The inner leaflet of the outer membrane is comprised of phospholipids and the outer leaflet of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (1). LPS consists of lipid A (endotoxin), a nonrepeating core oligosaccharide that includes two 3-deoxy-d-manno-oct-2-ulosonic acid (Kdo) residues, and an O-antigen polymer (2, 3). The outer membrane serves as a permeability barrier that protects cells from the entry of hydrophobic compounds, including detergents and antibiotics (1). LPS also plays an important role in the interactions between host organisms and bacterial pathogens (4). The lipid A moiety of LPS is recognized by the TLR4/MD2 receptor of the mammalian innate immune system (5), stimulating the production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF- α and IL-1β (6). During sepsis, extreme inflammation induced by LPS can damage small blood vessels, contributing to the syndrome of Gram-negative septic shock (7).

Members of the Burkholderia cepacia complex are opportunistic human pathogens that are of biomedical interest because they can cause severe necrotizing pneumonia and septicemia in cystic fibrosis patients and immuno-compromised individuals (8). Yersinia pestis causes “Bubonic Plague” in humans (9). These important Gram-negative pathogens synthesize an unusual isosteric analog of Kdo, known as d-glycero-d-talo-oct-2-ulosonic acid (Ko) (10–14) in which the axial hydrogen atom at the 3-position of the outer Kdo unit is replaced with an OH group (10) (Fig. 1A). The biosynthesis of Ko has not been elucidated (15). Here, we report the identification of a unique Kdo hydroxylase, designated KdoO (Fig. 1A), that is present in Burkholderia ambifaria (Fig. 1B) and Yersinia pestis. BaKdoO and YpKdoO display 52% sequence identity and 64% sequence similarity to each other (Fig. 1C). Both enzymes hydroxylate the 3-position of the outer Kdo residue of Kdo2-lipid A in a Fe2+/α-ketoglutarate/O2-dependent manner (Fig. 1A). Although the biological function of Ko is not known, Ko-Kdo-lipid A is less susceptible to mild acid hydrolysis than is Kdo2-lipid A of Escherichia coli. Our discovery of a structural gene encoding an enzyme that generates Ko will enable genetic studies of the function of Ko in the bacteria that produce it and the prediction of the presence of Ko in organisms that have not been investigated biochemically. KdoO is a unique example of a defined protein that catalyzes the hydroxylation of a deoxy-sugar moiety in a natural product (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A proposed Kdo dioxygenase that generates the Ko moiety of B. ambifaria and Y. pestis LPS. A. A possible Fe2+/α-ketoglutarate/O2-dependent dioxygenase, designated KdoO, might account for the origin of the Ko unit after Kdo2-lipid A formation, consistent with the fact that Ko-containing bacteria make CMP-Kdo and transfer two Kdo residues to lipid A in the same manner as bacteria lacking Ko (15). LpxO, which generates the secondary S-2-hydroxymyristate substituent of Salmonella lipid A, provides a precedent for an analogous Kdo2-lipid A hydroxylation (17). B. The bamb_0774 gene, located between waaC and waaA on the B. ambifaria chromosome [Copeland A, et al. (2006) Complete sequence of chromosomes 1, 2, and 3 and plasmid 1 of Burkholderia cenocepacia AMMD, submitted August 2006 to the European Molecular Biology Laboratory/GenBank/DNA Data Base in Japan databases] (35), was identified as a possible structural gene for the Kdo hydroxylase because it encodes a protein with the active site signature of a Fe2+/α-ketoglutarate/O2-dependent dioxygenase (18). KdoO otherwise displays no sequence similarity to LpxO. C. Alignment of Bamb_0774 from B. ambifaria and Y1812 from Y. pestis KIM. These proteins share 52% identity (shown in red) and 64% similarity, and both contain the potential iron-binding motif, HXDXnH (n > 40) (potential downstream His residues shown in blue). Schematic representations: Kdo, black boxes; Ko, orange box; glucosamine, blue ovals; acyl chains, green squiggles; phosphate group, P.

Results

Identification of a Gene Encoding a Putative Kdo Hydroxylase.

In many strains of Yersinia and Burkholderia, Ko replaces the distal Kdo unit of the Kdo disaccharide in LPS (10–14). We hypothesized that Ko might be derived from Kdo by an enzymatic hydroxylation reaction (Fig. 1A) with mechanistic similarity to LpxO (16, 17), the Fe2+/α-ketoglutarate/O2-dependent dioxygenase that generates the secondary S-2-hydroxymyristate chain of Salmonella lipid A. We therefore searched for genes that met three criteria: (i) their presence in appropriate strains of Burkholderia and Yersinia, but not E. coli or Salmonella; (ii) their clustering with other LPS biosynthetic genes; and (iii) the presence of the iron-binding motif HX(D/E)Xn>40H in the predicted protein (18, 19). The bamb_0774 gene of Burkholderia ambifaria encodes a protein of 294 amino acid residues and is located between the kdtA(waaA) and waaC(rfaC) genes (Fig. 1B) (2). Y1812, a protein of 301 amino acid residues from Y. pestis KIM, displays 52% identity and 64% similarity to Bamb_0774 (Fig. 1C). Both proteins contain the putative iron-binding motif HVD(X)n>40H (Fig. 1C, letters in blue), but show no overall sequence similarity to LpxO or any other protein of known function. No putative transmembrane segments are predicted for KdoO by the TMHMM algorithm (20). Several alternative start codons are possible for Y1812 based on the genome sequence (Fig. S1).

Heterologous Expression of bamb_0774 and y1812 in E. coli WBB06.

Hybrid plasmids harboring bamb_0774 or y1812 (Table S1) were transformed into E. coli WBB06 (21), a heptosyl transferase-deficient mutant that synthesizes Kdo2-lipid A as its only LPS (Fig. 1A, left structure). This substance can be extracted from cells with chloroform/methanol mixtures along with the glycerophospholipids and analyzed by thin layer chromatography (TLC) (22), as shown for the vector control WBB06/pWSK29 (Fig. 2). Interestingly, 50 to 90% of the Kdo2-lipid A band was shifted to a more slowly migrating form in WBB06 harboring either y1812 or bamb_0774, which were renamed YpkdoO and BakdoO, respectively (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

An altered form of Kdo2-lipid A in E. coli WBB06 expressing KdoO. Lipids were extracted (35) and separated by TLC, followed by charring with 10% sulfuric acid in ethanol. Cells harboring either pYpKdoO or pBaKdoO generated a slower migrating derivative of Kdo2-lipid A, consistent with Ko formation.

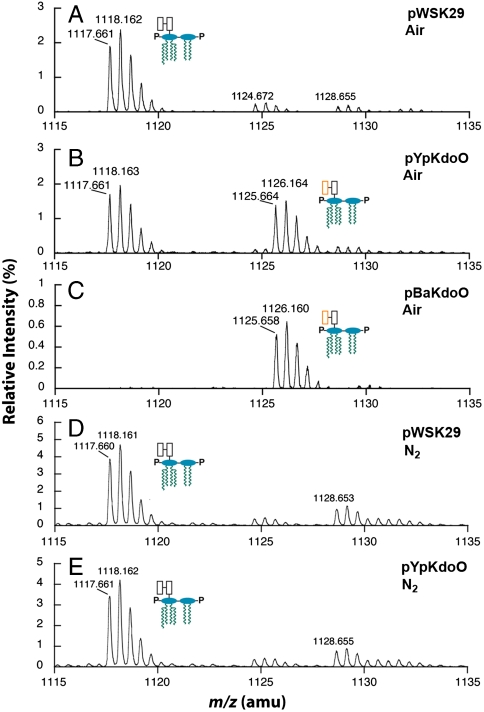

When analyzed by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) in the negative mode, Kdo2-lipid A forms well characterized doubly charged ions (predicted [M-2H]2- at m/z 1117.661) (Fig. 3A), which were used to calibrate the spectrum (22). In the constructs expressing YpKdoO or BakdoO, a doubly-charged species was seen at m/z 1125.664 or 1125.658, respectively (Fig. 3 B and C). This difference is consistent with the incorporation of one oxygen atom [+16 atomic mass unit (amu)], as expected for the biosynthesis of Ko-Kdo-lipid A (theoretical [M-2H]2- at m/z 1125.658), as shown in Fig. 1A. Conversion to Ko-Kdo-lipid A was almost quantitative with BaKdoO (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Kdo2-lipid A modification by KdoO involves hydroxylation and requires O2 A, B, and C. Cells expressing either YpKdoO or BaKdoO accumulate a Kdo2-lipid A derivative that is 16 amu larger than Kdo2-lipid A, consistent with the incorporation of a single oxygen atom and the generation of Ko-Kdo-lipid A (predicted [M-2H]2- at m/z 1,125.658). D and E. Growth in the absence of oxygen has no effect on the vector control but inhibits KdoO-dependent hydroxylation of Kdo2-lipid A. Schematic descriptions are the same as in Fig. 1.

Ko Formation Requires O2, and 18O from  Is Incorporated into the Product.

Is Incorporated into the Product.

When cells were grown in the presence of N2 gas instead of ambient air, the peak expected for the [M-2H]2- ion of Ko-Kdo-lipid A at m/z 1,125.658 was not observed in the mass spectrum of the lipids of WBB06/pYpKdoO (Fig. 3E), and the spectrum of the vector control was unchanged (Fig. 3D). Therefore, Ko formation by recombinant KdoO requires the presence of O2. A small peak at m/z 1,124.672 seen with both pYpKdoO and the vector control (Fig. 3A) may be due to the presence of small amounts of odd fatty acyl chains in the Kdo2-lipid A, as previously detected (23). These minor species were not altered by growth in the absence of oxygen. An additional peak at m/z 1,128.665 is attributed to the sodium adduct ion [M-3H + Na]2- of Kdo2-lipid A (Fig. 3A), which is present in variable amounts (Fig. 3 B–E).

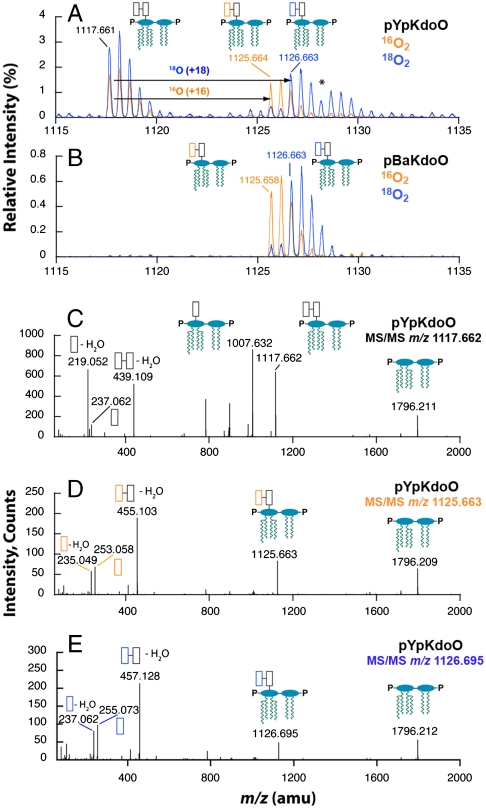

To demonstrate that the oxygen atom incorporated into Ko by KdoO is derived from O2 and not water, cells harboring either pYpKdoO or pBaKdoO were grown with ambient air or with 23%  mixed with N2 gas (Fig. 4 A and B). The relevant parts of the negative ion spectra of the LPS extracted from these cells are overlaid. The peak corresponding to the [M-2H]2- ion of Ko-Kdo-lipid A, obtained from the 18O2-grown cells, was observed at m/z 1,126.663 in both constructs (Fig. 4 A and B, blue spectra), which is 1 m/z larger (as a doubly-charged species) than the [M-2H]2- ion of the Ko-Kdo-lipid A generated in

mixed with N2 gas (Fig. 4 A and B). The relevant parts of the negative ion spectra of the LPS extracted from these cells are overlaid. The peak corresponding to the [M-2H]2- ion of Ko-Kdo-lipid A, obtained from the 18O2-grown cells, was observed at m/z 1,126.663 in both constructs (Fig. 4 A and B, blue spectra), which is 1 m/z larger (as a doubly-charged species) than the [M-2H]2- ion of the Ko-Kdo-lipid A generated in  -grown cells (Figs. 4 A and B, yellow spectra). This shift reflects the 2 amu difference between 16O and 18O, consistent with the proposed reaction in Fig. 1A.

-grown cells (Figs. 4 A and B, yellow spectra). This shift reflects the 2 amu difference between 16O and 18O, consistent with the proposed reaction in Fig. 1A.

Fig. 4.

18O from 18O2 is incorporated into the outer Kdo unit of Kdo2-lipid A by KdoO. A and B. KdoO expressing cells grown with 18O2 generate a Kdo2-lipid A derivative that is 1 m/z larger (as a doubly-charged species) than seen with 16O2-grown cells (blue vs. yellow spectra, respectively), confirming the incorporation of an O2-derived oxygen atom into the product. The asterisk* indicates the presence of the sodium adduct [M-3H + Na] ion of Kdo2-lipid A. C, D, and E. ESI-MS/MS analysis of Kdo2-lipid A, Ko-Kdo-lipid A, and [18O]Ko-Kdo-lipid A shows that YpKdoO modifies the outer Kdo unit, as evidenced in E by the [M-H]- ion of [18O]Ko at m/z 255.073, the [M-H216O-H]-ion of [18O]Ko at m/z 237.062, and the absence of corresponding [16O]Kdo fragments. Schematic descriptions are the same as in Fig. 1, except that [18O]Ko is indicated with a blue box.

ESI-MS/MS Analysis of the Ko-Kdo-Lipid A in WBB06 Cells Grown with  or

or  .

.

To identify the location of the oxygen atom in the truncated LPS isolated from WBB06 cells expressing YpKdoO, the first isotopic peak of each major ion was subjected to ESI-MS/MS analysis (Figs. 4 C–E). The fragmentation pattern of the unmodified Kdo2-lipid A from cells grown with ambient air (Fig. 4C) displayed the expected fragment ions (22), corresponding to the lipid A fragment ([M-H]- at m/z 1,796.211), the Kdo-lipid A fragment ([M-2H]2- at m/z 1,007.632), the Kdo2 fragment ([M-H2O-H]- at m/z 439.109), and the Kdo fragment ([M-H]- at m/z 237.062 and its dehydrated form [M-H2O-H]- at m/z 219.052). With the putative Ko-Kdo-lipid A product generated in the presence of 16O2, the peak attributed to [M-H]- of lipid A was seen at m/z 1,796.209, the same as with Kdo2-lipid A (Fig. 4D). Therefore, the extra oxygen atom present in the product was not incorporated into the lipid A moiety of the Kdo2-lipid A but into the Kdo disaccharide. The prominent peak observed at m/z 455.103 (Fig. 4D) was interpreted as the [M-H2O-H]- ion of the Ko-Kdo fragment derived from the Ko-Kdo-lipid A. Additional peaks seen in the MS/MS analysis of the Ko-Kdo-lipid A (Fig. 4D) were attributed to the [M-H]- and [M-H2O-H]- ions of Ko at m/z 253.058 and m/z 235.049, respectively. It is also noteworthy that the doubly-charged peak near m/z 1,007.6, attributed to the Kdo-lipid A fragment of Kdo2-lipid A (Fig. 4C), was greatly reduced in the product obtained from the Ko-Kdo-lipid A with the same collision energy (Fig. 4D), consistent with the idea that the glycosidic linkage of Ko is stronger than that of Kdo. The same fragmentation patterns were observed for the product generated by BaKdoO.

The ESI-MS/MS spectrum of the 18O-labeled Ko-Kdo-lipid A (Fig. 4E), generated by YpKdoO, confirmed that the oxygen atom incorporated into the outer Kdo unit was derived exclusively from O2 and not from water. The MS/MS spectrum shows a prominent peak at m/z 457.128, interpreted as the [M-H216O-H]- ion of [18O]Ko-Kdo (Fig. 4E). Furthermore, the spectrum also shows prominent peaks at m/z 255.073 and m/z 237.062 (Fig. 4E), consistent with the [M-H]- ion of [18O]Ko and the [M-H216O-H]- ion of [18O]Ko, respectively.

The results show that recombinant BaKdoO or YpKdoO catalyze the biosynthesis of Ko-Kdo lipid A in place of Kdo2-lipid A in E. coli WBB06. Hydroxylation must occur at the Kdo 3 position (Fig. 1A), given that incorporation at positions 4, 5, 7, or 8 would result in the elimination of water from the product through formation of an unstable gem-diol. Hydroxylation of the 6-position of the outer Kdo would result in the elimination of Kdo. Positions 1 and 2 of Kdo cannot be hydroxylated. We suggest that the OH group incorporated by KdoO at the 3-position has the axial configuration based on previous 1H-NMR analyses of Ko (Fig. 1A) (10). However, NMR studies of the product generated in vitro by KdoO will be required to establish this stereochemistry with certainty.

An Assay for KdoO Activity and Analysis of the Product Generated In Vitro.

An in vitro system for assaying recombinant YpKdoO was developed on the assumption that hydroxylation of Kdo by KdoO utilizes the same mechanism as reported for the lipid A dioxygenase LpxO (17). Although YpKdoO from WBB06/pYpKdoO was active in vivo (Figs. 2–4), YpKdoO protein was not present at very high levels when induced with 1 mM isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (IPTG). Therefore, an alternative expression plasmid, designated pYpKdoO.1 (Table S1), was generated and transformed into E. coli C41(DE3) (24). This construct greatly overexpresses YpKdoO when induced with 1 mM IPTG (Fig. S2A). YpKdoO protein was present both in the membrane-free supernatant and in the membranes of C41(DE3)/pYpKdoO.1, suggesting that YpKdoO is a peripheral membrane protein (Fig. S2A).

A TLC-based assay system with 5 μM Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid A as the substrate was developed for quantifying KdoO activity (Fig. 5A). Product formation was linear with time (Fig. 5A) and protein concentration. Activity was present in membrane-free lysates (Fig. 5A) and washed membranes (Fig. 5B) of C41(DE3)/pYpKdoO.1. Washed membranes were used to confirm the in vitro requirements for adding Fe2+, α-ketoglutarate, and ascorbic acid (Fig. 5B). The KdoO reaction was inhibited by inclusion of 1 mM EDTA (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

In vitro assay for KdoO and its cofactor requirements. A. Time course of the conversion of Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid A to Ko-Kdo-[4′-32P]lipid A by membrane-free lysates (0.05 mg/mL) of C41(DE3)/pYpKdoO.1. Abbreviation: NE, no enzyme. B. KdoO activity was insert dependent and required added Fe2+, α-ketoglutarate, and ascorbic acid. KdoO activity was inhibited by EDTA. Reactions were initiated by adding washed membranes of C41(DE3)/pYpKdoO.1 (0.02 mg/mL final concentration) and terminated by spotting 2 μL portions of the reactions onto silica TLC plates at various times. The plates were developed in chloroform∶methanol∶acetic acid∶H2O (25∶15∶3.5∶4 vol/vol) and quantified with a PhosphorImager screen.

The lipid product generated in vitro was purified by preparative TLC (Fig. S3A) and analyzed by ESI-MS. A peak consistent with formation of Ko-Kdo-lipid A (expected [M-2H]2- ion at m/z 1,125.658) was observed at m/z 1,125.659 (Fig. S3B). The data show unequivocally that efficient Ko formation by KdoO can occur with Kdo2-lipid A as the substrate.

The Presence of Ko Confers Resistance to Mild Acid Hydrolysis.

The difficulty of releasing free Kdo from Burkholderia LPS by mild acid hydrolysis has been attributed to the relative chemical stability of the Ko-Kdo linkage in this LPS (25). However, direct evidence to support this idea has not been reported. Reconstitution of KdoO activity in vitro allowed us to compare the resistance of Ko-Kdo-lipid A to that of Kdo2-lipid A during pH 4.5 hydrolysis at 100 °C . Two reaction mixtures were set up in parallel: the first was initiated with a membrane-free lysate from C41(DE3)/pET21(b); and the second with a membrane-free lysate from C41(DE3)/pYpKdoO.1. When the YpKdoO-containing mixture had converted ∼40% of the Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid A to Ko-Kdo-[4′-32P]lipid A, the reaction was quenched by adjusting the solution so that it contained 32.5 mM sodium acetate at pH 4.5. This mixture was then heated at 100 °C for the indicated times (Fig. S4). The stability of the Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid A and Ko-Kdo-[4′-32P]lipid A were monitored in parallel. The disappearance of the Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid A was much more rapid than that of Ko-Kdo-[4′-32P]lipid A (Fig. S4). The relative amounts of remaining substrates and hydrolysis products were expressed as their percentage of total amount of [4′-32P]lipid A-containing species remaining in the system. The data show that Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid A is more susceptible to mild acid hydrolysis than is Ko-Kdo-[4′-32P]lipid A under these conditions.

Discussion

Most Gram-negative bacteria synthesize Kdo, an eight-carbon 2-keto-3-deoxy sugar that forms the proximal portion of the core domain of LPS (Fig. 1A) (2). Two Kdo residues are usually present, one of which is linked directly to lipid A. A subset of Gram-negative bacteria, including B. cepacia (10–12), Y. pestis (13, 14), and some strains of Acinetobacter (26, 27), contain an unusual analog of Kdo, known as Ko, in which the axial hydrogen atom at position 3 of Kdo is replaced with an OH group (Fig. 1A). In B. cepacia and Y. pestis, Ko replaces the outer Kdo moiety (Fig. 1A), whereas in Acinetobacter the Ko unit replaces the inner Kdo residue.

The biosynthetic origin and function of Ko are unknown (15). In principle, Ko might be synthesized by a different pathway than the one that generates CMP-Kdo from arabinose 5-phosphate and phosphoenolpyruvate. However, B. cepacia, like E. coli, contains all the enzymes that make CMP-Kdo, and it possesses a bifunctional Kdo transferase that generates a Kdo disaccharide in vitro (12, 15). In Y. pestis, Ko synthesis is stimulated by growth at low temperatures (28), which also regulates the number and composition of the acyl chains in lipid A of this organism (29).

We have now discovered that Ko-Kdo-lipid A can be generated in living cells and in vitro by hydroxylation of Kdo2-lipid A. The enzyme that catalyzes Kdo hydroxylation, termed KdoO, is a unique member of the Fe2+/α-ketoglutarate/O2-dependent dioxygenase family (18, 19). The KdoO structural gene (Fig. 1B) was identified by inspection of a gene cluster in B. ambifaria that is responsible for the biosynthesis of the inner LPS core. A KdoO orthologue is also present in Y. pestis (Fig. 1C), but not in E. coli or Salmonella. Significant KdoO homologues also are encoded by the human pathogens Burkholderia mallei, Burkholderia pseudomallei, Klebsiella variicola, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Legionella longbeachae, and Coxiella burnetii, by the plant pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum (Fig. S5), and by some environmental organisms like Methylobacterium extorquens. The available genomes of Acinetobacter do not encode KdoO, suggesting that the inner Ko unit of Acinetobacter is generated by a different enzyme.

Fe2+/α-ketoglutarate/O2-dependent dioxygenases constitute a large and diverse family of mononuclear nonheme iron enzymes (18, 19). Crystal structures of different α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases have revealed a common architecture (18, 19). Whereas these proteins may show low overall sequence similarity, most α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases share the HX(D/E)XnHXm(R/K)XS motif (in which n = 50–70 and m = 10, n = 138–207 and m = 10–13, or n = 72–101 and m = 10) (18, 19). The HX(D/E)Xn>40H segment provides ligands for Fe2+, whereas the (R/K)XS residues bind the C-5 carboxylate moiety of α-ketoglutarate (18, 19). KdoO does not show significant sequence similarity to any known Fe2+/α-ketoglutarate/O2-dependent dioxygenase, except for the HX(D/E)Xn>40H motif. Although KdoO requires α-ketoglutarate as a cosubstrate, KdoO does not possess an obvious (R/K)XS sequence. All KdoO orthologues are currently annotated as conserved or hypothetical proteins of unknown function, restricted to a subset of Gram-negative bacteria.

Two Fe2+/α-ketoglutarate/O2-dependent enzymes that hydroxylate a deoxy-sugar moiety have been reported previously (30, 31), the 1′- or 2′- deoxyuridine hydroxylases from Rhodotorula glutinis. However, the genes and proteins responsible for these functions were not identified and sequenced (30, 31). To our knowledge, KdoO is a unique example of a defined protein that catalyzes the hydroxylation of a sugar moiety in nature. It will be of great interest to determine the structure, substrate selectivity, and mechanism of KdoO. Although very active with Kdo2-lipid A in vitro (Fig. 5) and functional when expressed in E. coli WBB06 (Figs. 2–4), we cannot entirely exclude the possibility that KdoO also hydroxylates free Kdo or CMP-Kdo. However, KdoO is a peripheral membrane protein (Fig. S2) and likely faces the cytoplasmic side of the inner membrane where it would encounter Kdo2-lipid A.

The physiological role of Ko remains to be elucidated. The addition of an OH group to the 3-position of the outer Kdo unit might enhance or modulate the binding of LPS to TLR4/MD2 (5). The Ko-Kdo bond may be stronger than the Kdo-Kdo linkage, based on its resistance to mild acid hydrolysis (Fig. S4) and the ESI-MS/MS fragmentation patterns (Fig. 4). The extra OH group in Ko might facilitate hydrogen bonding between adjacent LPS molecules in the outer membrane and provide an advantage under stressful environmental conditions. However, in our E. coli constructs, there is no effect of KdoO expression on bile salt, polymyxin, or calcium sensitivity. In Burkholderia cenocepacia, one 4-amino-4-deoxy-l-arabinose unit is linked to the Ko moiety of the core, possibly providing additional resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides (10). The enzyme responsible for 4-amino-4-deoxy-l-arabinose addition to Ko is unknown, but it might require the prior conversion of Kdo to Ko for its activity.

The identification of the kdoO gene will enable the construction of mutants unable to make Ko, and the evaluation of the effects of Ko ablation on LPS assembly and pathogenesis. Furthermore, the heterologous expression of KdoO in bacteria like E. coli or Salmonella may provide access to attenuated strains and unique vaccine adjuvants.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and plasmids used for this study are listed in Table S1. All materials, molecular biology applications, preparation of membranes and membrane-free lysates, methods for assaying Ko-Kdo-lipid A formation in vitro, and methods for determining the susceptibility of Kdo2-lipid A and Ko-Kdo-lipid A to mild acid hydrolysis are described in SI Text. Primers used for this study are listed in Table S2. The methods for lipid extraction from WBB06/pWSK29, WBB06/pYpKdoO and WBB06/pBaKdoO and ESI/MS analysis of Kdo2-lipid A and Ko-Kdo-lipid A are described in SI Text.

Anaerobic Growth of WBB06/pWSK29 and WBB06/pYpKdoO.

Cells were grown overnight aerobically in LB medium (32) supplemented with 50 μg/mL of ampicillin. To exclude oxygen during subsequent growth, autoclaved 500 mL glass bottles were filled to the top with LB medium containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin and 1 mM IPTG. The bottles were sealed with a plastic cap containing an inlet and an outlet needle. The medium was then purged by bubbling for 1 h with N2 through the inlet needle, which was immersed 0.5 inches below the surface. The N2 was passed through a sterile filter prior to purging the medium. Anaerobic cultures were inoculated by 1∶150 dilution of the overnight cultures (initial A600 ∼ 0.015). The anaerobic cultures were tightly capped as above, and grown with N2 bubbling through an 18 gauge inlet needle (immersed 0.5 inches below the surface) for 22 h at room temperature without shaking (final A600 0.30 for WBB06/pWSK29 and 0.29 for WBB06/pYpKdoO). The cultures were vented through a second 18 gauge outlet needle. Cells were harvested, washed with 20 mL PBS (33), and processed as described in SI Text to isolate the lipids.

Growth of WBB06/pYpKdoO and WBB06/pBaKdoO Under 18O2.

The procedure for growth in the presence of 18O2 was adapted with minor modification from Gibbons et al. (16, 17). A sealed 1-liter flask containing 200 mL of LB medium with 50 μg/mL of ampicillin and 1 mM IPTG was inoculated with a 1∶100 dilution of an overnight culture of WBB06/pYpKdoO or WBB06/pBaKdoO. The flask was evacuated to 74 mm Hg, as determined using a Marsh Instrument Co. model 1305-12 in-line vacuum gauge. The flask was purged with N2 and evacuated two more times to eliminate as much residual  as possible. Following the third evacuation, the pressure of the container was brought to 252 mm Hg with 18O2 and then to 760 mm Hg (1 atm) with N2, resulting in an atmosphere of ∼23% 18O2 at 97% isotopic enrichment. Parallel cultures for each construct were grown at 37 °C under ambient air in 200 mL of LB medium with 50 μg/mL of ampicillin and 1 mM IPTG as controls. When the control cultures reached an A600 ∼ 1.0, the cells were harvested from the control and 18O2-labeled cultures, given that the growth rates of both cultures were similar.

as possible. Following the third evacuation, the pressure of the container was brought to 252 mm Hg with 18O2 and then to 760 mm Hg (1 atm) with N2, resulting in an atmosphere of ∼23% 18O2 at 97% isotopic enrichment. Parallel cultures for each construct were grown at 37 °C under ambient air in 200 mL of LB medium with 50 μg/mL of ampicillin and 1 mM IPTG as controls. When the control cultures reached an A600 ∼ 1.0, the cells were harvested from the control and 18O2-labeled cultures, given that the growth rates of both cultures were similar.

In Vitro Assay for KdoO Activity.

The Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid A substrate was prepared according to published procedures (34). Unlabeled Kdo2-lipid A was obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids. The in vitro assay for KdoO was developed based on the previously reported assay for LpxO. The reaction mixture (typically in a final volume of 20 μL) contained 50 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (Hepes), pH 7.5, 1 mM α-ketoglutarate, 2 mM ascorbate, 15 μM Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2, 0.1% Triton X-100, 4 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mg/mL bovine serum albumin, and 5 μM Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid A (∼300,000 cpm/nmol). Ascorbate, α-ketoglutarate, and Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2 solutions were freshly prepared before each assay using deionized H2O degassed with N2. Assays were carried out at 30 °C. Reactions were initiated by adding membrane-free lysate (0.05 mg/mL final concentration) derived from E. coli C41(DE3)/ pYpKdoO.1 or its vector control. The reactions were terminated by spotting 1.5–2 μL of the reaction mixtures onto the origin of a 20 × 20 cm Silica Gel 60 TLC plate. The plate was dried with a cold air stream, and the lipids were separated by TLC in the freshly prepared and equilibrated tank containing the solvent chloroform∶methanol∶acetic acid∶H2O (25∶15∶3.5∶4, vol/vol). Following chromatography, the TLC plate was dried under a hot air stream and was exposed to a PhosphorImager screen for 12–16 h. The extent of conversion of Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid A to Ko-Kdo-[4′-32P]lipid A was determined with a PhosphorImager (GE Healthcare), equipped with ImageQuant software.

Determination of Cofactors Required for KdoO Activity.

To confirm that KdoO is a Fe2+/α-ketoglutarate/O2-dependent dioxygenase, these components were eliminated one at a time from the assay system. Alternatively, 1 mM EDTA was added to the assay mixture. Reactions were initiated with washed membranes (0.02 mg/mL final) derived from E. coli C41(DE3)/pYpKdoO.1 or its vector control. The reactions were incubated at 30 °C. After 0, 4, 8, 12, 20, 30, and 45 min, 1.8 μL of samples were withdrawn and spotted onto a 20 × 20 cm silica TLC plate, which was developed in chloroform∶methanol∶acetic acid∶H2O (25∶15∶3.5∶4 vol/vol) and quantified following exposure to a PhosphorImager screen.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

The authors thank all the members of the Raetz Laboratory for stimulating discussions. We are especially grateful to Drs. Brian Ingram and Mike Reynolds for help with the design of assays and 18O labeling experiments. We thank Drs. Louis E. Metzger 4th, David Six, and Ziqiang Guan for critical reading of the manuscript. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant GM-51796 to C.R.H.R. The mass spectrometry facility in the Department of Biochemistry of the Duke University Medical Center is supported by the LIPID MAPS Large Scale Collaborative Grant number GM-069338 from NIH.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1016462108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Nikaido H. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiol Mol Biol R. 2003;67:593–656. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.593-656.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raetz CRH, Whitfield C. Lipopolysaccharide endotoxins. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:635–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raetz CRH, Reynolds CM, Trent MS, Bishop RE. Lipid A modification systems in gram-negative bacteria. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:295–329. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.010307.145803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller SI, Ernst RK, Bader MW. LPS, TLR4 and infectious disease diversity. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:36–46. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park BS, et al. The structural basis of lipopolysaccharide recognition by the TLR4-MD-2 complex. Nature. 2009;458:1191–1195. doi: 10.1038/nature07830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124:783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russell JA. Management of sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1699–1713. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lynch JP., 3rd Burkholderia cepacia complex: impact on the cystic fibrosis lung lesion. Semin Respir Crit Care. 2009;30:596–610. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1238918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prentice MB, Rahalison L. Plague. Lancet. 2007;369:1196–1207. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60566-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isshiki Y, Kawahara K, Zähringer U. Isolation and characterization of disodium (4-amino-4-deoxy-beta-L- arabinopyranosyl)-(1 → 8)-(D-glycero-alpha-D-talo-oct-2-ulopyranosylonate)- (2 → 4)-(methyl 3-deoxy-D-manno-oct-2-ulopyranosid)onate from the lipopolysaccharide of Burkholderia cepacia. Carbohydr Res. 1998;313:21–27. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(98)00179-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Isshiki Y, Zähringer U, Kawahara K. Structure of the core-oligosaccharide with a characteristic D-glycero-alpha-D-talo-oct-2-ulosylonate-(2 → 4)-3-deoxy-D-manno-oct-2-ulosonate [alpha-Ko-(2 → 4)-Kdo] disaccharide in the lipopolysaccharide from Burkholderia cepacia. Carbohydr Res. 2003;338:2659–2666. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gronow S, Noah C, Blumenthal A, Lindner B, Brade H. Construction of a deep-rough mutant of Burkholderia cepacia ATCC 25416 and characterization of its chemical and biological properties. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1647–1655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206942200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vinogradov EV, et al. The core structure of the lipopolysaccharide from the causative agent of Plague, Yersinia pestis. Carbohydr Res. 2002;337:775–777. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(02)00074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knirel YA, et al. Temperature-dependent variations and intraspecies diversity of the structure of the lipopolysaccharide of Yersinia pestis. Biochemistry. 2005;44:1731–1743. doi: 10.1021/bi048430f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gronow S, Xia G, Brade H. Glycosyltransferases involved in the biosynthesis of the inner core region of different lipopolysaccharides. Eur J Cell Biol. 2010;89:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibbons HS, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. Oxygen requirement for the biosynthesis of the S-2-hydroxymyristate moiety in Salmonella typhimurium lipid A. Function of LpxO, a new Fe(II)/alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase homologue. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32940–32949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005779200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibbons HS, Reynolds CM, Guan Z, Raetz CRH. An inner membrane dioxygenase that generates the 2-hydroxymyristate moiety of Salmonella lipid A. Biochemistry. 2008;47:2814–2825. doi: 10.1021/bi702457c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Costas M, Mehn MP, Jensen MP, Que L., Jr Dioxygen activation at mononuclear nonheme iron active sites: enzymes, models, and intermediates. Chem Rev. 2004;104:939–986. doi: 10.1021/cr020628n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kovaleva EG, Lipscomb JD. Versatility of biological non-heme Fe(II) centers in oxygen activation reactions. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:186–193. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer ELL. Predicting trans-membrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brabetz W, Muller-Loennies S, Holst O, Brade H. Deletion of the heptosyltransferase genes rfaC and rfaF in Escherichia coli K-12 results in an Re-type lipopolysaccharide with a high degree of 2-aminoethanol phosphate substitution. Eur J Biochem. 1997;247:716–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raetz CRH, et al. (Kdo)2-lipid A of Escherichia coli, a defined endotoxin that activates macrophages via TLR-4. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:1097–1111. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600027-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murphy RC, Raetz CRH, Reynolds CM, Barkley RM. Mass spectrometry advances in lipidomica: collision-induced decomposition of (Kdo)2-lipid A. Prostag Oth Lipid M. 2005;77:131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miroux B, Walker JE. Over-production of proteins in Escherichia coli: mutant hosts that allow synthesis of some membrane proteins and globular proteins at high levels. J Mol Biol. 1996;260:289–298. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vinion-Dubiel AD, Goldberg JB. Lipopolysaccharide of Burkholderia cepacia complex. J Endotoxin Res. 2003;9:201–213. doi: 10.1179/096805103225001404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vinogradov EV, Bock K, Petersen BO, Holst O, Brade H. The structure of the carbohydrate backbone of the lipopolysaccharide from Acinetobacter strain ATCC 17905. Eur J Biochem. 1997;243:122–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.0122a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vinogradov EV, et al. Structural investigation of the lipopolysaccharide from Acinetobacter haemolyticus strain NCTC 10305 (ATCC 17906, DNA group 4) Eur J Biochem. 1997;247:82–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knirel YA, et al. Cold temperature-induced modifications to the composition and structure of the lipopolysaccharide of Yersinia pestis. Carbohydr Res. 2005;340:1625–1630. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montminy SW, et al. Virulence factors of Yersinia pestis are overcome by a strong lipopolysaccharide response. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1066–1073. doi: 10.1038/ni1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Warn-Cramer BJ, Macrander LA, Abbott MT. Markedly different ascorbate dependencies of the sequential alpha-ketoglutarate dioxygenase reactions catalyzed by an essentially homogeneous thymine 7-hydroxylase from Rhodotorula glutinis. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:10551–10557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stubbe J. Identification of two alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases in extracts of Rhodotorula glutinis catalyzing deoxyuridine hydroxylation. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:9972–9975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller JR. Experiments in molecular genetics. NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dulbecco R, Vogt M. Plaque formation and isolation of pure lines with poliomyelitis viruses. J Exp Med. 1954;99:167–182. doi: 10.1084/jem.99.2.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tran AX, et al. Periplasmic cleavage and modification of the 1-phosphate group of Helicobacter pylori lipid A. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:55780–55791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406480200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bligh EG, Dyer JJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.