Abstract

Cyclic nucleotide-gated (CNG) channels play an essential role in the visual and olfactory sensory systems and are ubiquitous in eukaryotes. Details of their underlying ion selectivity properties are still not fully understood and are a matter of debate in the absence of high-resolution structures. To reveal the structural mechanism of ion selectivity in CNG channels, particularly their Ca2+ blockage property, we engineered a set of mimics of CNG channel pores for both structural and functional analysis. The mimics faithfully represent the CNG channels they are modeled after, permeate Na+ and K+ equally well, and exhibit the same Ca2+ blockage and permeation properties. Their high-resolution structures reveal a hitherto unseen selectivity filter architecture comprising three contiguous ion binding sites in which Na+ and K+ bind with different ion-ligand geometries. Our structural analysis reveals that the conserved acidic residue in the filter is essential for Ca2+ binding but not through direct ion chelation as in the currently accepted view. Furthermore, structural insight from our CNG mimics allows us to pinpoint equivalent interactions in CNG channels through structure-based mutagenesis that have previously not been predicted using NaK or K+ channel models.

Cyclic nucleotide-gated (CNG) channels are central to signal transduction in the visual and olfactory sensory systems (1–4). These channels conduct various mono and divalent cations and, under physiological conditions, are more permeable to Ca2+ than Na+ (5–9). Ca2+ permeation, mediated through a highly conserved acidic residue (most commonly Glu) in the selectivity filter, lowers channel conductance by effectively blocking monovalent cation currents (7, 10–18) and plays an essential physiological role in visual transduction (1). A Glu-to-Asp mutation enhances Ca2+ binding whereas a Glu-to-Asn mutation diminishes it. In the absence of CNG channel structures, structural insight into the molecular details underlying ion nonselectivity has been limited to K+ channel models (19, 20) and, more recently, the prokaryotic nonselective cation channel NaK from Bacillus cereus (21, 22). Although previous studies on NaK have yielded important insights into Ca2+ binding in cation channels, they fall short of explaining several key mechanistic differences between NaK and CNG channels. First, the submillimolar affinity of external Ca2+ binding observed in NaK is much weaker than that of most CNG channels (23). Second, an Asp-to-Glu mutation in the NaK filter leads to a higher Ca2+ binding affinity whereas the opposite holds true for CNG channels (24–26). Finally, selectivity filter sequences of CNG, K+, and NaK channels differ significantly after the conserved T(V/I)G residues in both amino acid composition and sequence length, a majority of CNG channels containing an ETPP motif (Fig. 1A), suggesting a different filter architecture. To reveal the structural mechanism of nonselective permeation, and more importantly, Ca2+ blockage in CNG channels, we fine tuned the NaK model by generating a set of chimera channel pores with selectivity filter sequences matching those of CNG channels.

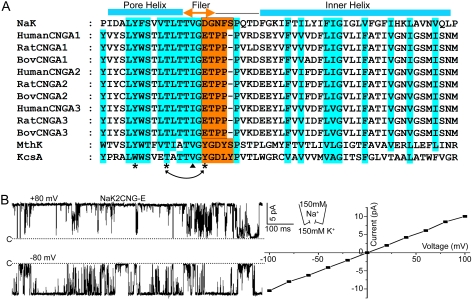

Fig. 1.

(A) Partial sequence alignment between NaK, K+ channels (MthK and KcsA) and human, rat, and bovine CNG channel alpha subunits (A1–A3). Semiconserved residues are shaded in cyan. Residues in NaK replaced by corresponding CNG channel residues are shaded in orange. Secondary structure assignment is based on the NaKNΔ19 structures (PDB ID 3E86). Asterisks mark the positions where mutagenesis was performed on bovine CNGA1 based on the NaK2CNG-E structure and arrows indicate the residues for swap mutations. (B) Single channel traces of NaK2CNG-E at ± 80 mV and its I-V curve. Currents were recorded using giant liposome patch clamping with 150 mM NaCl and 150 mM KCl in the pipette and bath solutions, respectively. Dotted lines mark the zero current level.

Results

Generating NaK Chimeras That Mimic CNG Channel Pores.

A majority of CNG channels contain an amino acid sequence of ETPP C-terminal to the T(V/I)G residues that are also conserved in NaK and K+ selective channel selectivity filters (Fig. 1A). The NaK channel has an amino acid sequence of DGNFS in the equivalent region where only the acidic residue (Asp66) is conserved. Furthermore, the sequence is one residue longer in the NaK channel. Accordingly, the selectivity filters of commonly found CNG channels and their mutants (Glu-to-Asp and Glu-to-Asn) for Ca2+ binding studies were reproduced in NaK by altering its filter sequence of TVGDGNFS to TVGETPP (NaK2CNG-E), TVGDTPP (NaK2CNG-D), and TVGNTPP (NaK2CNG-N) (Fig. 1A). Although residue positions equivalent to Val64 in NaK (position marked by a triangle in Fig. 1A) are occupied by Ile in most CNG channels, such an alteration does not affect the protein packing surrounding the selectivity filter; a NaK mutant containing a TIGDTPP filter sequence has virtually the same structure as NaK2CNG-D, suggesting that the NaK2CNG chimeras presented in this study can accommodate Ile in the filter without structural change. Therefore all the studies presented here were performed with Val at position 64.

The CNG-Mimicking NaK Chimeras Are Nonselective.

All NaK2CNG chimeras share biochemical properties similar to wild-type channel and can be purified as stable tetramers. Giant liposome patching was employed to assay the functional properties of the channels and confirm their nonselective nature (Materials and Methods). In order to observe single channel currents, all NaK2CNG chimeras used for functional studies carried an additional Phe92Ala mutation which has been shown to increase ion flux through the channel pore (23, 27). Fig. 1 B and C show sample single channel traces for NaK2CNG-E recorded under bi-ionic conditions (150 mM NaCl and 150 mM KCl in the pipette and bath solutions, respectively) along with its I-V curve. The mutant channels exhibit a high single channel conductance in both directions with a reversal potential of 0 mV, indicating the channel is indeed nonselective with virtually the same permeability for Na+ and K+. NaK2CNG-D and NaK2CNG-N exhibit similar properties (Fig. S1). All mutant channels also exhibit very high open probability. Even though we have yet to discover the channel’s gating mechanism, this high open probability greatly aides our functional analysis in this study.

Structural Determination of NaK2CNG Chimeras.

Structures of all three NaK2CNG chimeras in complex with various cations were determined in an open conformation between resolutions of 1.58 and 1.95 Å (Materials and Methods, Fig. S2A, and Table S1). The K+ complex structure of NaK2CNG-D will be used here to describe the overall structural features, shared by all the mutants, focusing on the selectivity filter region. The NaK2CNG-D selectivity filter adopts a distinct architecture akin to an intermediate between NaK and KcsA (Fig. S2 B and C), and contains three contiguous ion binding sites equivalent to sites 2–4 of a K+ channel and numbered as such for comparison (Fig. 2A). The external entryway has a concave funnel shape with the pyrrolidine ring from the first proline (Pro68) in the filter region, absolutely conserved in CNG channels, forming the wall of the funnel (Fig. 2A). Two layers of well-ordered water molecules, four in each, are observed within the funnel. These water molecules, particularly the four in the inner layer right above site 2, form a hydration shell that participates in stabilizing various cations in the funnel upon entering or exiting the filter.

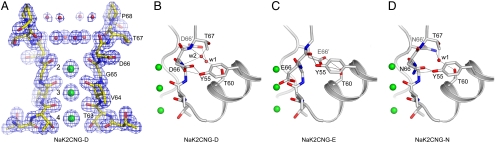

Fig. 2.

Selectivity filter structures of CNG-mimicking NaK mutants. (A) Selectivity filter structure of NaK2CNG-D in complex with K+ ions. The 2Fo-Fc electron density map (1.62 Å) is contoured at 2.0σ (blue mesh). Red spheres represent the two layers of water molecules within the external funnel. Three ion binding sites are labeled 2–4 from top to bottom. (B–D) Protein packing around the selectivity filters of (B) NaK2CNG-D, (C) NaK2CNG-E, and (D) NaK2CNG-N. Red spheres represent water molecules that mediate the hydrogen bonding network. Residue 66 from the neighboring subunit is labeled as D66′, E66′, and N66′, respectively. All K+ ions in the filter are drawn as green spheres.

Protein Packing Around the Selectivity Filter.

Although the overall selectivity filter structure in the three CNG-mimicking mutants is similar, noticeable differences in protein packing in the region surrounding it are observed owing to the different amino acid composition of residue 66 (Fig. 2 B–D and Fig. S3). The side chain of residue 66 (Glu, Asp, or Asn) in all mutants remains buried underneath the external surface of the protein and points away from the ion conduction pathway, but forms different hydrogen bonding interactions with its neighboring residues in all three cases. The different hydrogen bonding networks, some mediated through water molecules, are highlighted in Fig. 2 and Fig. S3. The differences in protein packing at residue 66 lead to subtle changes in the backbone carbonyl position of Gly65 among the different mutants, which likely accounts for altered ion binding profiles in the filter, particularly at site 2 (see SI Discussion and Figs. S4 and S5).

Na+ and K+ Binding in the Selectivity Filter.

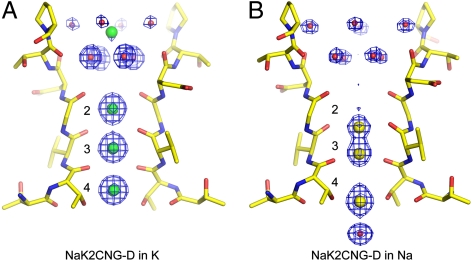

Despite similar permeability for Na+ and K+, we observed clear differences in ion-ligand geometries between the two ions as illustrated by the NaK2CNG-D-Na+ and -K+ complex structures (Fig. 3). The K+ complex structure reveals three electron density peaks with equivalent intensity in the filter, indicating K+ binding with similar occupancy at each site (Fig. 3A). A weaker electron density peak, likely from a K+ ion with lower occupancy, is observed at the center of the external funnel sandwiched between the two layers of water molecules. In the Na+ complex, three strong peaks are observed at sites 3 and 4, two at the upper and lower edges of site 3, and the other on the lower edge of site 4 (Fig. 3B). In the cavity just below site 4, a water molecule, not observed in K+ complex, participates in the chelation of a Na+ ion at the lower edge of site 4. Some weaker electron density is also observed in the center of site 2 and at the external entrance likely arising from low occupancy Na+ binding. Although the filter structure remains unchanged in both complexes (Fig. S6), K+ ions tend to bind at the center of each site, whereas Na+ clearly prefers to bind on the upper or lower edge of each site equatorially with its ligands. The latter configuration allows for shorter ion-ligand distances and preferable Na+ ion binding. Similar patterns of Na+ and K+ binding are also observed in NaK2CNG-E and NaK2CNG-N. Details of Na+ and K+ binding profiles in all three mutants are discussed in the SI Text and are summarized in Fig. S5.

Fig. 3.

K+ and Na+ binding in the selectivity filter of NaK2CNG-D (A) Fo-Fc ion omit map focusing on the selectivity filter of the NaK2CNG-D-K+ complex (1.62 Å) contoured at 4σ. (B) Fo-Fc ion omit maps focusing on the selectivity filter of the NaK2CNG-D-Na+ complex (1.58 Å) contoured at 4σ. Water molecules within the external funnel (red spheres) were also omitted in the map calculation. K+ and Na+ ions are represented by green and yellow spheres, respectively.

Ca2+ Binding in the Selectivity Filter.

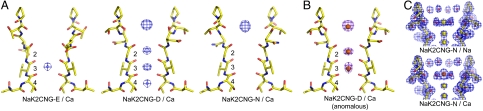

Ca2+ complexes of the engineered chimeras were obtained by crystal soaking in stabilization solutions containing 100 mM NaCl/25 mM CaCl2 (Materials and Methods). These Na/Ca-soaked crystals were compared with the Na+-soaked crystals (reference crystals) using FNa/Ca-soak - FNa-soak difference Fourier maps to determine whether and where Ca2+ binds (Fig. 4A). The FNa/Ca-soak - FNa-soak difference map of NaK2CNG-E indicates that a single Ca2+ ion binds at site 3 (Fig. 4A, Left). Ca2+ binding in NaK2CNG-D is more complex and the difference map reveals four major peaks along the ion conduction pathway: three at sites 2–4 inside the filter and one within the funnel just above the external entrance (Fig. 4A, Center). To verify whether these are due to Ca2+ binding and do not arise from Na+, which is also present in the soaking conditions, we calculated the anomalous difference Fourier map from a Ca/Na-soaked NaK2CNG-D crystal collected at longer wavelength (λ = 1.5 Å) at which Ca2+ ion is the only element in the protein that has significant anomalous scattering. As shown in Fig. 4B, the anomalous difference Fourier map reveals three peaks at the same positions as the top three observed in the FNa/Ca-soak - FNa-soak difference map, confirming Ca2+ binding at sites 2, 3, and above the external entrance. In the control experiment, the anomalous difference Fourier map from a Na+-soaked NaK2CNG-D crystal does not show anomalous signals in the filter. The fourth peak in the FNa/Ca-soak - FNa-soak difference map of NaK2CNG-D is likely due to the redistribution of Na+ at site 4 upon Ca2+ binding.

Fig. 4.

Ca2+ binding in the selectivity filter of NaK mutants. (A) FNa/Ca-soak-FNa-soak difference Fourier maps between mutant crystals soaked in stabilization solutions containing 100 mM NaCl (Na-soak) and in solutions containing both 100 mM NaCl and 25 mM CaCl2 (Na/Ca-soak). Maps are contoured at 8σ at a resolution of 2.0 Å for NaK2CNG-E (Left) and 1.8 Å for NaK2CNG-D (Center) and NaK2CNG-N (Right). (B) Anomalous difference Fourier map (purple mesh, at 1.9 Å and contoured at 5σ) of a Na/Ca-soaked NaK2CNG-D crystal indicates the positions of bound Ca2+ ions (orange spheres). (C) 2Fo-Fc maps of Na-soaked (Upper, 1.62 Å) and Na/Ca-soaked (Upper, 1.63 Å) NaK2CNG-N crystals reveal the hydration of an externally bound Na+ (yellow sphere) or Ca2+ ion (orange sphere) by the inner layer of water molecules within the funnel. External Ca2+ in NaK2CNG-D is bound in the same hydrated form.

The FNa/Ca-soak - FNa-soak difference map for NaK2CNG-N reveals a single electron density peak within the funnel at the same position as the external peak observed in NaK2CNG-D, (Fig. 4A, Right) indicating that, compared to NaK2CNG-D, Ca2+ binding inside the selectivity filter is abolished in NaK2CNG-N but external Ca2+ binding is retained. The position of this externally bound Ca2+ in NaK2CNG-N or NaK2CNG-D is slightly above the external entrance, at the same position as the hydrated Na+ ion observed in the Na+ complexes (Fig. 4C and Fig. S5). Refined structures from the Na/Ca-soaked crystals of both mutants reveal that the external Ca2+ is also hydrated by the inner layer of water molecules similar to Na+ and has no direct interaction with the protein (Fig. 4C). We believe this external Ca2+ binding observed in both NaK2CNG-N and NaK2CNG-D is not specific and simply arises from the competition between hydrated Na+ and Ca2+ ions within the funnel at high Ca2+ concentration. This conclusion is consistent with our functional analysis, described below, which shows that in NaK2CNG-N external Ca2+ causes a reduction in channel current only at high concentrations.

Ca2+ is a Permeable Blocker for NaK2CNG Chimeras.

Ca2+ blockage in our CNG-mimicking channels was functionally characterized using giant liposome patch clamping with various concentrations of Ca2+ added to the external side of the channel in addition to 150 mM K+. As shown in single channel traces, inward K+ currents in NaK2CNG-E and NaK2CNG-D decrease with increasing [Ca2+] whereas NaK2CNG-N has almost no sensitivity to external Ca2+ (Fig. 5A). A plot of unblocked current as a function of [Ca2+] gives rise to Kis of 58.3 and 6.3 μM at -80 mV for NaK2CNG-E and NaK2CNG-D, respectively (Fig. 5B). The Ca2+ binding affinity in NaK2CNG-E is similar to that observed in some eukaryotic CNGA2 and A3 channels (2). Higher Ca2+ affinity in NaK2CNG-D is also consistent with CNG channel studies which have shown that a Glu-to-Asp mutation in the filter enhances Ca2+ blockage (24–26). We believe the multiple Ca2+ binding (at sites 2 and 3) in the NaK2CNG-D filter, resulting from the position of the side-chain carboxylate group of Asp66 and the presence of two water molecules, contributes to this difference (see SI Discussion). Furthermore, as observed for CNG channels, Ca2+ acts as a permeating blocker in the engineered mimics. The Ca2+ permeation was confirmed using single channel recording on NaK2CNG-E with 100 mM CaCl2 in the bath solution, which shows a clear Ca2+ current, albeit with low conductance (Fig. 5C, upper trace). Addition of tetrapentyl ammonium, an open pore blocker for K+ channels that can also block NaK from intracellular side, leads to a complete inhibition of the observed Ca2+ current (Fig. 5C, lower trace).

Fig. 5.

Ca2+ blockage and permeation in NaK mutants. (A) Single channel traces of NaK2CNG-E (Left traces), NaK2CNG-D (Center traces), and NaK2CNG-N (Right traces) recorded at -80 mV in the presence of various concentrations of external Ca2+. Both pipette and bath solutions contain symmetrical 150 mM KCl. Additionally, 30 μM tetrapentyl ammonium (TPeA) was added to the bath solution to ensure that recorded currents are from mutant channels oriented with their external side facing the bath solution. (B) Plot of the fraction of unblocked single channel currents recorded at -80 mV as a function of external Ca2+ concentrations. Data points are mean ± SEM from five measurements and are fitted to the Hill equation with Ki of 58.3 ± 6.3 μM and Hill coefficient n = 0.98 ± 0.1 for NaK2CNG-E, and Ki of 6.3 ± 0.62 μM and n = 1.22 ± 0.1 for NaK2CNG-D. (C) Single channel traces of NaK2CNG-E recorded at -80 mV with 150 mM KCl in the pipette and 100 mM CaCl2 in the bath solution. The single channel in the recordings had its intracellular side facing the bath solution and was blocked by addition of 30 μM TPeA in bath solution (bottom trace).

Mutagenesis of CNG Channels Based on the Structure of NaK2CNG Chimera.

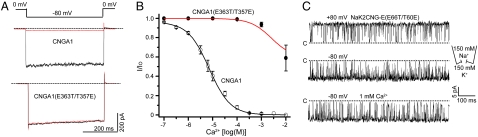

We used insights from our chimera models to directly perform mutagenesis on the bovine retinal CNG channel (CNGA1) using NaK2CNG-E as a model. In the NaK2CNG-E structure, the carboxylate of Glu66 forms a hydrogen bond directly with the hydroxyl group of Thr60 from a neighboring subunit (Fig. 2C). To test whether such an interaction exists in CNG channels, we generated a CNGA1 mutant channel with the equivalent residues, Glu363 and Thr357, swapped (Fig. 1A). Whereas the single mutation (T357E) failed to yield functional channels, the E363T/T357E double mutation gave rise to a functional channel that conducts monovalent cations similar to wild type, but is no longer blocked by external Ca2+ (Fig. 6 A and B). An identical residue swap in NaK2CNG-E yielded a channel that was strikingly similar to the swap mutation of CNGA1: The channel conducts Na+ and K+ just like NaK2CNG-E but is no longer sensitive to external Ca2+ blockage (Fig. 6C). The data confirm the direct interaction between Glu363 and Thr357 in CNG channels and also demonstrate the importance of the exact position of the glutamate side chain in Ca2+ binding.

Fig. 6.

Mutagenesis of bovine CNGA1 channel based on the structure of NaK2CNG-E. (A) Macroscopic currents of wild-type bovine retinal CNGA1 (Upper) and its E363T/T357E swapped mutation (Lower) recorded at -80 mV in the presence (red traces) and absence (black traces) of 100 μM extracellular Ca2+. Channels were activated by 1 mM cGMP in the pipette solution. (B) Plot of the fraction of unblocked inward currents (I/Io) at -80 mV as a function of external Ca2+ concentrations. Data points are mean ± SEM from five measurements and are fitted to Langmuir functions with Ki of 7.1 μM for wild-type CNGA1. (C) Single channel traces of NaK2CNG-E (E66T/T60E) swapped mutation recorded at ± 80 mV with 150 mM NaCl in the pipette and 150 mM KCl in the bath solution (top two traces). Addition of 1 mM Ca2+ at extracellular side (bath solution) has no effect on single channel conductance at -80 mV (bottom trace).

Tyr55 in the pore helix appears to be a key player in protein packing around the selectivity filter of the NaK2CNG chimeras. In NaK2CNG-E, it forms a short-range hydrogen bond with the backbone carbonyl oxygen of Glu66 that is expected to be important in stabilizing the selectivity filter. This tyrosine is absolutely conserved in CNG channels and is likely to play a similar role. Indeed, no obvious current was observed when we replaced the equivalent Tyr (Tyr352) to Phe in CNGA1 at a voltage range of ± 100 mV. In a recent study of the same channel, replacing Tyr352 with Ala renders the channel conductance strongly voltage dependent resulting from voltage-dependent conformational changes at the filter (28). Furthermore, interaction between Tyr352 and Glu363 (equivalent to Tyr55 and Glu66 in NaK2CNG-E) has been implicated in the same study, consistent with our structural observation.

Discussion

Our data on Ca2+ blockage yield interesting and unique insights into the underlying structural mechanisms of specific Ca2+ binding in CNG channels. Contrary to conventional models, the Ca2+ ion in the filter is exclusively chelated by backbone carbonyl oxygen atoms and not directly by the acidic side chain which, particularly in NaK2CNG-E, is oriented tangential to the ion conduction pathway and buried underneath the external surface of the protein, seemingly unable to make any direct contact with main-chain atoms of the selectivity filter (Fig. 2 and Fig. S3). Ca2+ specificity could arise from the presence of a negative charge in close proximity that could perturb the charge distribution along the backbone of the filter residues, making certain carbonyl oxygen atoms more electronegative and more suited for Ca2+ binding. Additionally, specificity could also arise from the side-chain carboxylate of the acidic residue in the NaK2CNG chimeras being buried in a fairly hydrophobic environment shielded from the ion conduction pathway by the main-chain atoms of the selectivity filter residues. This low-dielectric environment may enhance the electrostatic interaction between the negative charge and the cation in the filter which, combined with the presence of four such negative charges in a channel tetramer, may help stabilize the doubly charged Ca2+ ion.

The structural study presented here provides an accurate picture of how Ca2+ binds in the selectivity filter as well as the position of conserved acidic residues mediating it. In light of other striking similarities between the two groups, we feel these NaK2CNG chimera structures represent accurate structural models for CNG channel pores, complementing long-standing electrophysiological studies and providing unique insights into the structural mechanism of CNG channel function. The efficacy of these models is further verified by our data on chimera structure-based mutagenesis studies of the bovine retinal CNG channel (CNGA1).

Although further study is needed to work out exact details of Ca2+ binding mechanisms, we believe our observations very likely hold true for CNG channels. A similar mechanism may also apply to voltage-gated Ca2+ channels whose Ca2+ binding mechanism has been suggested to be similar to CNG channels (2, 4), utilizing the four conserved glutamate resides in the filter, one from each homologous domain, to confer Ca2+ specificity (29–31). Finally, our high-resolution structures also open the door for computational simulations aimed at providing a more theoretical explanation for Ca2+ binding in tetrameric cation channels.

Materials and Methods

Protein purification, crystallization, and structure determination of all NaK2CNG chimeras followed our recent study of NaKNΔ19, a truncated NaK channel lacking the N-terminal M0 helix (27). Similarly, these mutant structures were determined in an open conformation between resolutions of 1.58 and 1.95 Å (Table S1 and SI Materials and Methods). All chimeras used for functional studies contain an extra Phe to Ala mutation at a position equivalent to Phe92 of NaK in order to enhance the single channel conductance, and the proteins were reconstituted in lipid vesicles composed of 3∶1 ratio of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphatidylethanolamine and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphatidylglycerol (Avanti Polar Lipids) at a protein/lipid ratio of 0.1 μg/mg as described (21, 32). Giant liposomes were obtained by air drying followed by rehydration. Giant liposome patches were performed as described in SI Text. The gene encoding bovine retinal cyclic GMP-gated channel (CNGA1) was cloned into the pcDNA3.1(+) plasmid and the channel was expressed in HEK 293 cells. The channel currents were recorded 2–4 d after transfection using patch clamp in a whole-cell configuration. Detailed descriptions of materials and methods are provided in SI Text.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

Use of the Advanced Photon Source and the Advanced Light Source was supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Energy Research. We thank the beamline staff for assistance in data collection. This work was supported in part by The Howard Hughes Medical Institute and by grants from the National Institute of Health (GM079179 to Y.J.) and The David and Lucile Packard Foundation. M.G.D. was supported by Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award Predoctoral Fellowship (5 F31 GM07703) from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID codes 3K0D, 3K03, and 3K06 for K+ complexes of NaK2CNG-E, NaK2CNG-D, and NaK2CNG-N, respectively; and 3K0G, 3K04, and 3K08 for Na+ complexes of NaK2CNG-E, NaK2CNG-D, and NaK2CNG-N, respectively).

See companion article on page 598.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1013643108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Yau KW, Baylor DA. Cyclic GMP-activated conductance of retinal photoreceptor cells. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1989;12:289–327. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.12.030189.001445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaupp UB, Seifert R. Cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:769–824. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00008.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matulef K, Zagotta WN. Cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003;19:23–44. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.110701.154854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zagotta WN, Siegelbaum SA. Structure and function of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1996;19:235–263. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.001315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumann A, Frings S, Godde M, Seifert R, Kaupp UB. Primary structure and functional expression of a Drosophila cyclic nucleotide-gated channel present in eyes and antennae. EMBO J. 1994;13:5040–5050. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06833.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finn JT, Solessio EC, Yau KW. A cGMP-gated cation channel in depolarizing photoreceptors of the lizard parietal eye. Nature. 1997;385:815–819. doi: 10.1038/385815a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frings S, Seifert R, Godde M, Kaupp UB. Profoundly different calcium permeation and blockage determine the specific function of distinct cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Neuron. 1995;15:169–179. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hackos DH, Korenbrot JI. Divalent cation selectivity is a function of gating in native and recombinant cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels from retinal photoreceptors. J Gen Physiol. 1999;113:799–818. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.6.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Picones A, Korenbrot JI. Permeability and interaction of Ca2+ with cGMP-gated ion channels differ in retinal rod and cone photoreceptors. Biophys J. 1995;69:120–127. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)79881-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haynes LW, Kay AR, Yau KW. Single cyclic GMP-activated channel activity in excised patches of rod outer segment membrane. Nature. 1986;321:66–70. doi: 10.1038/321066a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stern JH, Knutsson H, MacLeish PR. Divalent cations directly affect the conductance of excised patches of rod photoreceptor membrane. Science. 1987;236:1674–1678. doi: 10.1126/science.3037695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colamartino G, Menini A, Torre V. Blockage and permeation of divalent cations through the cyclic GMP-activated channel from tiger salamander retinal rods. J Physiol. 1991;440:189–206. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zimmerman AL, Baylor DA. Cation interactions within the cyclic GMP-activated channel of retinal rods from the tiger salamander. J Physiol. 1992;449:759–783. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zufall F, Firestein S, Shepherd GM. Cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels and sensory transduction in olfactory receptor neurons. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1994;23:577–607. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.23.060194.003045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haynes L, Yau KW. Cyclic GMP-sensitive conductance in outer segment membrane of catfish cones. Nature. 1985;317:61–64. doi: 10.1038/317061a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dzeja C, Hagen V, Kaupp UB, Frings S. Ca2+ permeation in cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. EMBO J. 1999;18:131–144. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.1.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Root MJ, MacKinnon R. Identification of an external divalent cation-binding site in the pore of a cGMP-activated channel. Neuron. 1993;11:459–466. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90150-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eismann E, Muller F, Heinemann SH, Kaupp UB. A single negative charge within the pore region of a cGMP-gated channel controls rectification, Ca2+ blockage, and ionic selectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1109–1113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.3.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doyle DA, et al. The structure of the potassium channel: Molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science. 1998;280:69–77. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou Y, Morais-Cabral JH, Kaufman A, MacKinnon R. Chemistry of ion coordination and hydration revealed by a K+ channel-Fab complex at 2.0 A resolution. Nature. 2001;414:43–48. doi: 10.1038/35102009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alam A, Shi N, Jiang Y. Structural insight into Ca2+ specificity in tetrameric cation channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15334–15339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707324104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi N, Ye S, Alam A, Chen L, Jiang Y. Atomic structure of a Na+- and K+-conducting channel. Nature. 2006;440:570–574. doi: 10.1038/nature04508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alam A, Jiang Y. Structural analysis of ion selectivity in the NaK channel. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:35–41. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park CS, MacKinnon R. Divalent cation selectivity in a cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel. Biochemistry. 1995;34:13328–13333. doi: 10.1021/bi00041a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seifert R, Eismann E, Ludwig J, Baumann A, Kaupp UB. Molecular determinants of a Ca2+-binding site in the pore of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels: S5/S6 segments control affinity of intrapore glutamates. EMBO J. 1999;18:119–130. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.1.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gavazzo P, Picco C, Eismann E, Kaupp UB, Menini A. A point mutation in the pore region alters gating, Ca(2+) blockage, and permeation of olfactory cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. J Gen Physiol. 2000;116:311–326. doi: 10.1085/jgp.116.3.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alam A, Jiang Y. High-resolution structure of the open NaK channel. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:30–34. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martinez-Francois JR, Xu Y, Lu Z. Mutations reveal voltage gating of CNGA1 channels in saturating cGMP. J Gen Physiol. 2009;134:151–164. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200910240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang S, et al. Molecular localization of ion selectivity sites within the pore of a human L-type cardiac calcium channel. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:13026–13029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ellinor PT, Yang J, Sather WA, Zhang JF, Tsien RW. Ca2+ channel selectivity at a single locus for high-affinity Ca2+ interactions. Neuron. 1995;15:1121–1132. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang J, Ellinor PT, Sather WA, Zhang JF, Tsien RW. Molecular determinants of Ca2+ selectivity and ion permeation in L-type Ca2+ channels. Nature. 1993;366:158–161. doi: 10.1038/366158a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heginbotham L, LeMasurier M, Kolmakova-Partensky L, Miller C. Single streptomyces lividans K(+) channels: Functional asymmetries and sidedness of proton activation. J Gen Physiol. 1999;114:551–560. doi: 10.1085/jgp.114.4.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.