Abstract

One of the two essential virulence factors of Bacillus anthracis is the poly-γ-d-glutamic acid (γDPGA) capsule. Five γDPGA-specific antibody antigen-binding fragments (Fabs) were generated from immunized chimpanzees. The two selected for further study, Fabs 11D and 4C, were both converted into full-length IgG1 and IgG3 mAbs having human IgG1 or IgG3 constant regions. These two mAbs had similar binding affinities, in vitro opsonophagocytic activities, and in vivo efficacies, with the IgG1 and IgG3 subclasses reacting similarly. The mAbs bound to γDPGA specifically with estimated binding affinities (Kd) of 35–70 nM and effective affinities (effective Kd) of 0.1–0.3 nM. The LD50 in an opsonophagocytic bactericidal assay was ≈10 ng/mL of 11D or 4C. A single 30-μg dose of either mAb given to BALB/c mice 18 h before challenge conferred about 50% protection against a lethal intratracheal spore challenge by the virulent B. anthracis Ames strain. More importantly, either mAb given 8 h or 20 h after challenge provided significant protection against lethal infection. Thus, these anti-γDPGA mAbs should be useful, alone or in combination with antitoxin mAbs, for achieving a safe and efficacious postexposure therapy for anthrax.

The Gram-positive, spore-forming bacterium Bacillus anthracis is the causal agent of anthrax. Anthrax is primarily a disease of herbivores, but all mammals, including humans, may be affected. Although naturally occurring anthrax infection of humans is rare, the 2001 anthrax attack through the US Postal Service highlighted the need for a safe and efficacious postexposure therapy for anthrax infection. The current Centers for Disease Control recommendations for treatment following potential exposure to aerosolized B. anthracis spores calls for administration of antibiotics for at least 60 d and the licensed protective antigen-based vaccine (1). However, antibiotic treatment can be ineffective when bacterial strains are antibiotic resistant (2). An alternative to treatment with antibiotics is desirable. Passive immunization through administration of mAbs against the capsule of B. anthracis may represent such an alternative.

Vegetative B. anthracis bacilli are encapsulated with a homopolymeric capsule composed of glutamic acid residues linked by γ peptide bonds. The glutamic acid residues of the homopolymer are solely in the d-form (γDPGA). The biosynthetic operon capBCADE encoding the capsule is present on the plasmid pXO2 (3–6). Strains that lack pXO2 are highly attenuated (7–9), and such strains have been used as vaccines to prevent anthrax in domesticated animals for more than 50 y (10). In a mouse model of pulmonary anthrax, encapsulation was shown to be essential for dissemination from the lungs and for persistence and survival of the bacterium in the host (7). Virulence appears to be associated with antiphagocytic properties of the capsule (5, 11, 12). A recent study showing that degradation of the capsule by a γ-polyglutamic acid depolymerase enhanced both in vitro macrophage phagocytosis and neutrophil killing of encapsulated B. anthracis further supports the antiphagocytic nature of the capsule (13).

Given the important role of the capsule in virulence, several recent studies have used the capsule of B. anthracis as a potential target for vaccine and neutralizing mAb development (14–20). These studies demonstrated that both active and passive vaccination targeting the B. anthracis capsule protected animals against experimental infection, suggesting that methods to increase the phagocytosis of encapsulated B. anthracis bacilli may be valuable in the treatment of anthrax.

The γDPGA capsule is poorly immunogenic and acts as a thymus-independent, type 2 antigen (21). Mouse mAbs specific to γDPGA capsule were generated successfully from mice immunized with γDPGA in combination with a CD40 agonist mAb (19, 20). These mouse mAbs were shown to be protective in a murine model of pulmonary anthrax. However, these mouse mAbs are not suitable for therapeutic use in humans because they induce a detrimental human anti-mouse antibody response. The aim of the present study was to generate clinically useful anti-γDPGA chimpanzee-derived mAbs. Because chimpanzee Igs are virtually identical to human Igs, chimpanzee-derived mAbs may be used in humans without further modification. The antibodies to γDPGA capsule were induced by immunizing chimpanzees with conjugates of immunogenic carrier proteins and synthetic γ-d-glutamic acid peptides (14). The γDPGA capsule-specific mAbs were generated by phage display library technology and were characterized in detail.

Results

Isolation and Characterization of Poly-γ-d-Glutamic Acid–Specific Antibody Antigen-Binding Fragments.

γDPGA-specific phage clones were recovered from the antibody antigen-binding fragment (Fab)-displaying phage library after three cycles of panning against γDPGA. DNA sequencing of the variable regions of heavy and light chains from γDPGA-specific clones revealed five distinct clones that were designated “4C,” “11D,” “2G,” “6H,” and “8A.” The amino acid sequences of the complementarity-determining region 3 (CDR3) of the heavy (HCDR3) and light (LCDR3) chains are shown in Fig. 1. The closest human V-gene germ-line origin of the five clones was determined from a sequence similarity search of all known human Ig genes (Table 1). Interestingly, the heavy chains of all five clones belong exclusively to family 3, with three clones using IGHV3-23*04 gene and two clones using IGHV3-49*04 gene. Three κ chains and two λ chains were used for the light chain. Both heavy and light chains appeared to have undergone somatic mutations, because 87–94% identity to germ-line V- genes was observed (Table 1).

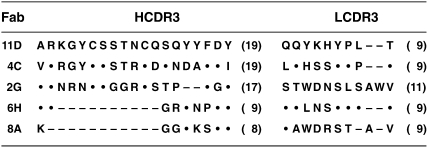

Fig. 1.

Alignment of the amino acid sequences of the HCDR3 and LCDR3 chains of five γDPGA-specific Fabs. The CDR3 regions were defined according to the IMGT nomenclature system. The number of amino acid residues in the CDR3 region of each Fab is shown in parenthesis. Identical residues relative to the clone 11D are identified by a dot (.), and missing residues are identified by a dash (–).

Table 1.

Assignment of five anti-PGA Fab clones to their closest human germ-line counterparts, based on nucleotide sequence homology*

| Heavy chain |

Light chain |

||||||

| mAb | V-gene | Identity (%) | J-gene | D-gene | V-gene | Identity (%) | J-gene |

| 11D | IGHV3-23*04 | 89 | IGHJ4*02 | IGHD2-2*01 | IGKV1D-16*01 | 92 | IGKJ4*01 |

| 4C | IGHV3-23*04 | 87 | IGHJ3*02 | IGHD2-2*01 | IGKV1D-17*02 | 89 | IGKJ1*01 |

| 2G | IGHV3-49*04 | 93 | IGHJ4*02 | IGHD2-15*01 | IGLV10-54*01 | 94 | IGLJ3*03 |

| 6H | IGHV3-23*04 | 87 | IGHJ4*02 | IGHD1-1*01 | IGKV1-5*03 | 90 | IGKJ4*01 |

| 8A | IGHV3-49*04 | 91 | IGHJ4*02 | IGHD5-24*01 | IGLV3-1*01 | 88 | IGLJ3*02 |

*The closest human V-gene germ lines were identified by search of the IMGT database at http://www.imgt.org/.

The initial competitive inhibition ELISA showed that the five Fab clones were binding to the same or an overlapping epitope on the antigen because they competed with each other for binding. The Fab clones 11D and 4C were selected as representative clones for further characterization because they have relatively longer HCDR3 regions (Fig. 1). Fab 11D and 4C sequences were converted into full-length IgG mAb with human γ1 and γ3 constant regions, and the two mAbs, regardless of IgG1 or IgG3 subclass, bound to γDPGA with similar titers in ELISA.

Binding Affinity.

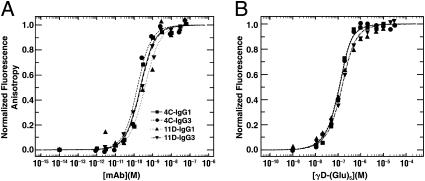

Fluorescence anisotropy assays at a series of mAb concentrations were applied to determine the affinities of the mAbs for a 10-mer peptide of γDPGA, taking advantage of the fluorescent tag on the 10-mer and the size increase upon complex formation. For all four IgGs tested, the anisotropy increased with increasing IgG concentrations until saturation was reached (Fig. 2A). Because binding data from surface plasmon resonance (SPR) experiments showed that one 10-mer could bind to two mAbs, the binding process we monitored on the 10-mer was not monovalent. Therefore, this assay is considered to measure avidity (effective affinity, effective Kd). As indicated in Table 2, the analysis yielded similar avidity with the 10-mer for the four IgGs, with effective Kd of 0.1–0.3 nM.

Fig. 2.

Changes in fluorescence upon addition of increasing amounts of mAb into fluorescently labeled γd-(Glu)10 peptide solution (A) or addition of increasing amounts of γd-(Glu)5 peptide into mAb solution (B). The normalized fluorescence anisotropy at emission wavelength 530 nM (A) or intensity readings at emission wavelength 341 nm (B) were plotted against concentrations of the titrant (mAb or 5-mer) for each titration point, followed by a nonlinear least squares regression analysis of a 1:1 binding model using SEDPHAT (sedfitsedphat.nibib.nih.gov).

Table 2.

Measured affinities and avidities for anti-γDPGA mAbs 11D and 4C

| mAbs | Effective Kd (10-mer)* (nM) | Kd (5-mer)† (nM) |

| 11D IgG1 | 0.3 | 63.9 |

| 11D IgG3 | 0.2 | 69.7 |

| 4C IgG1 | 0.2 | 35.6 |

| 4C IgG3 | 0.1 | 34.7 |

*The effective Kd was determined by fluorescence anistropy assay.

†The Kd was determined by fluorescence tryptophan perturbation assay.

To explore monovalent binding of mAbs to γDPGA, a smaller, 5-mer peptide was synthesized. A monovalent binding process between the 5-mer peptide and mAbs was found in preliminary SPR analyses. Affinity measurements then were obtained using the change of intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence when increasing amounts of γd-(Glu)5 were mixed with the mAb solution. The two mAbs, 11D and 4C, demonstrated different patterns of binding to γd-(Glu)5. The mAb 11D IgG1 and IgG3 proteins showed a signal decrease with increasing amounts of the γd-(Glu)5, accompanied by a blue shift in emission. In contrast, mAb 4C IgG1 and IgG3 indicated a signal increase and a red shift when binding to the γd-(Glu)5. These observations suggested that key tryptophan residues in the two proteins were in different chemical environments. The tryptophan residues were exposed to a more hydrophobic environment upon binding to the γd-(Glu)5 for the mAb 11D group and to a more polar one for the mAb 4C group (22). Equilibrium titration data of 5-mer binding to the mAbs were analyzed and are shown in Fig. 2B. IgG1 and IgG3 of the two mAbs showed similar affinities with a Kd of 35–70 nM (Table 2).

Opsonophagocytic Bactericidal Activity.

The in vitro opsonophagocytic bactericidal activity of the 4C and 11D anti-γDPGA mAbs was measured by their ability to kill capsulated B. anthracis cells in the presence of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes and complement. High opsonic titers of 1:100,000, 1:100,000, 1:125,000, and 1:158,000 (corresponding to 10 ng/mL, 10 ng/mL, 8 ng/mL, and 6.8 ng/mL of IgG) were reproducibly observed for 4C IgG1, 11D IgG1, 4C IgG3, and 11D IgG3, respectively. Thus, we did not detect a significant difference in the opsonophagocytic bactericidal activities between two MAbs or between IgG1 and IgG3 subclasses.

Linear regression analyses were used to determine the correlation between antibody concentration and the opsonophagocytic bactericidal activity. The calculated regression coefficient (r2) was 0.9782 for 4C IgG1, 0.9873 for 11D IgG1, 0.9908 for 4C IgG3, and 0.9953 for 11D IgG3, indicating a strong correlation between antibody concentrations and opsonophagocytic bactericidal activities.

Protection of Mice Against Pulmonary Challenge with Virulent B. anthracis Spores.

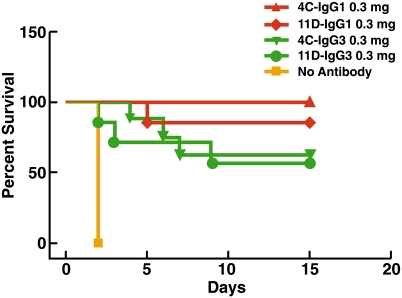

A murine inhalational anthrax model was used to assess the protective efficacy of the anti-γDPGA mAbs. First, to compare the efficacy of mAbs 4C and 11D and of the IgG1 and IgG3 subclasses of each mAb, the mice were pretreated with the mAbs at doses of 3 mg, 1 mg, or 0.3 mg per mouse and were challenged 18 h later with a dose of 1.5 × 104 spores (≈15 LD50). The survival results (Table 3) showed that pretreatment with either the IgG1 or IgG3 subclasses of the 4C or 11D mAbs provided significant protection at a dose of 0.3 mg per mouse against a lethal pulmonary challenge with B. anthracis (Ames strain) spores as compared with the vehicle control group, which all died by day 2 postinfection (P ≤ 0.001 for each mAb dose compared with control group). There was no significant difference in survival of mice pretreated at the lowest treatment dose of 0.3 mg per mouse with the IgG1 or IgG3 subclasses of the 4C mAb when compared with the 11D mAb (P > 0.2 and P > 0.7, respectively). There was a trend for the IgG1 subclass of both the 11D and the 4C mAbs to provide a higher level of protection than the IgG3 subclass of each mAb, but the difference in survival was not statistically significant at the doses tested (P > 0.05 at each dose) (Fig. 3).

Table 3.

Protection of mice from intratracheal challenge with B. anthracis (Ames strain) spores by anti-capsular mAbs*

| Time of treatment | mAb | Dose (mg) | Number surviving/ number in group† | Survival (%) |

| Irrelevant human IgG1 | 1 | 0/8 | 0 | |

| 11D IgG1 | 3 | 7/7 | 100 | |

| 1 | 7/7 | 100 | ||

| 0.3 | 6/7 | 86 | ||

| 0.1 | 6/8 | 75 | ||

| 0.03 | 5/8 | 63 | ||

| 18 h prechallenge | 11D IgG3 | 3 | 6/8 | 75 |

| 1 | 8/8 | 100 | ||

| 0.3 | 4/7 | 57 | ||

| 4C IgG1 | 3 | 8/8 | 100 | |

| 1 | 8/8 | 100 | ||

| 0.3 | 8/8 | 100 | ||

| 0.1 | 5/8 | 63 | ||

| 0.03 | 3/7 | 43 | ||

| 4C IgG3 | 3 | 4/5 | 80 | |

| 1 | 5/7 | 71 | ||

| 0.3 | 5/8 | 63 | ||

| 8 h postchallenge | 11D IgG1 | 1 | 7/7 | 100 |

| 4C IgG1 | 1 | 5/7 | 71 | |

| 20 h postchallenge 1‡ | 11D IgG1 | 1 | 3/5 | 60 |

| 4C IgG1 | 1 | 5/5 | 100 | |

| 20 h postchallenge 2 | 11D IgG1 | 1 | 2/10 | 20 |

| 4C IgG1 | 1 | 4/10 | 40 |

*BALB/c mice were injected i.p. with the designated dose of 11D or 4C at 18 h prechallenge or 8 h and 20 h postchallenge. The mice were challenged i.t. with 0.522–1.43 × 104 B. anthracis (Ames strain) spores/mouse.

†All groups started with 5–10 mice per group, but a few mice were lost during the inoculation procedure because of anesthesia complications.

‡The 20-h postchallenge group was tested twice with challenge doses of 0.522 × 104 spores per mouse for the first experiment and 1.43 × 104 spores per mouse for the second experiment.

Fig. 3.

Survival of mice pretreated with either IgG1 or IgG3 of the anti-γDPGA mAb at 0.3-mg dosage. Groups of mice (eight mice per group) were treated i.p. with the designated dose of mAb 11D or 4C at 18 h prechallenge. Control mice received vehicle alone. The mice then were infected i.t. with 1.5 × 104 B. anthracis (Ames strain) spores. The survival of mice was monitored twice daily for 2 wk postchallenge. Treatment with either the 4C or 11D anti-γDPGA mAbs provided significant protection against infection with B. anthracis as compared with the vehicle control group (P < 0.05 for all groups). No significant difference was detected in the protection provided by the IgG1 or IgG3 subclass of mAb 4C (P > 0.05) or by the two subclasses of 11D (P > 0.05).

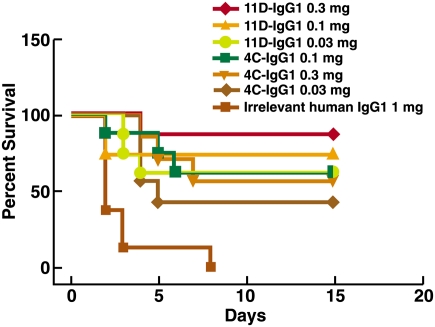

To determine the minimal effective dose of 4C and 11D IgG1 mAbs, groups of mice were pretreated with lower concentrations of the mAbs (0.3, 0.1, and 0.03 mg per mouse) and were challenged 18 h later with a lethal dose (0.5 × 104 spores; ≈5 LD50) of B. anthracis spores (Fig.4 and Table 3). Administration of either the 11D IgG1 or 4C IgG1 mAbs at a dose of 0.03 mg per mouse resulted in a significant increase in survival as compared with mice treated with an irrelevant control IgG1 mAb (P < 0.005). Again, no statistical difference was detected in the survival of mice treated with the 4C or11D mAbs (P > 0.2).

Fig. 4.

Determination of the minimal effective dose for mAbs 11D and 4C. Groups of mice (eight mice per group) were treated with the designated doses of mAb 11D or 4C at 18 h prechallenge. The mice then were infected i.t. with 5.2 × 103 B. anthracis (Ames strain) spores. Mice receiving 1 mg per mouse of irrelevant human mAb were used as a control group. The survival of mice was monitored twice daily for 2 wk postchallenge. Treatment with either the 4C or 11D anti-γDPGA mAb provided significant protection against infection with B. anthracis at all doses tested as compared with the control group (P < 0.05 for all groups).

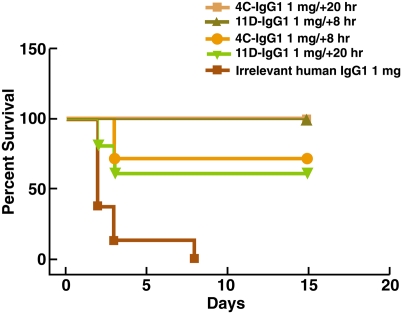

To assess the potential therapeutic value of the anti-γDPGA mAbs, a 1-mg dose of either the 4C IgG1 mAb or 11D IgG1 mAb was administrated to groups of mice 8 or 20 h after challenge with 0.5 × 104 spores (≈5 LD50). As shown in Table 3 and Fig. 5, significant protection was seen with the 11D and 4C mAbs administered at either 8 h or 20 h postchallenge when compared with mice treated with control mAb (P < 0.05). To confirm the 20-h postchallenge protection data, a second study (Table 3) was conducted using a slightly higher B. anthracis challenge dose (∼13 LD50). Although the overall percent survival was lower, significant protection again was observed in groups of mice administered either the 11D or 4C mAb at 20 h postchallenge as compared with groups treated with an irrelevant control mAb (P ≤ 0.005 for either 11D or 4C mAb as compared with control group). Again, no statistical difference was detected between the mice treated with the 4C vs. 11D mAbs.

Fig. 5.

Postchallenge protection of mice by mAbs 11D and 4C. Mice were infected i.t. with 5.2 × 103 B. anthracis (Ames strain) spores. The mice then were treated with 1 mg per mouse of mAb 11D or 4C at 8 h (seven mice) or 20 h (five mice) postchallenge. Mice receiving 1 mg per mouse of irrelevant human mAb at 20 h postchallenge were used as a control. Postchallenge treatment with either the 4C or 11D anti-γDPGA mAb at 8 and 20 h postchallenge provided significant protection against infection with B. anthracis as compared with the control group (P < 0.05 for all groups).

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that passive immunization with murine anti-γDPGA mAbs was protective in a murine pulmonary anthrax model when administered 18 h before infection (19, 20). Here, we demonstrated that chimpanzee/human anti-γDPGA mAbs 11D and 4C not only provided prophylactic protection but also conferred therapeutic protection when administrated 20 h after infection.

An interesting finding from these studies was that these chimpanzee/human anti-γDPGA mAbs exhibited a higher protective efficacy than previously reported for the murine anti-γDPGA mAbs (19, 20). The ED50 reported for the most effective murine mAbs tested was ≈500 μg per mouse (20), whereas the ED50 for our chimpanzee/human mAbs was ≈30 μg per mouse. This difference in the effective dose probably is explained by a 10-fold higher binding affinity in our chimpanzee/human mAbs than observed for the murine mAbs. The evidence that even 1 μg/mL of anti-polyglutamic acid (PGA) IgG (the expected concentration from dilution of 30 μg within a 30-g mouse) is protective argues for inclusion of PGA immunogens/conjugates in future anthrax vaccines. Prior evidence shows the efficacy of PGA vaccines (16), and our work reported here extends this result and suggests that conjugates able to induce even modest levels of appropriate anti-PGA antibodies would be very effective.

In addition to showing that prophylactic treatment with the 4C and 11D mAbs is protective against a lethal pulmonary challenge with B. anthracis spores, we have shown in this study that therapeutic treatment with anti-γDPGA mAbs can provide significant protection at least 20 h postchallenge. This result is impressive because it was shown previously that B. anthracis was present in the lung-associated lymph nodes 5 h after infection and could be detected in the spleen as early as 20 h after infection in most of the mice (23). It will be interesting to determine in the future how late after challenge treatment can be effective, because this information has important implications for treatment of patients who already are symptomatic or have evidence of bacteremia.

The fact that an opsonic anticapsular antibody is effective at low doses and even some hours after infection is consistent with the previously expressed view (24) that the most efficacious bacterial vaccines (and, by implication, passively administered antibodies) act by killing the small numbers of infecting bacteria (i.e., the inoculum). Apparently in the infection model used here, the number of bacteria present within the first day remains sufficiently low to be susceptible to opsonophagocytic clearance. Only when the bacteria have replicated and made amounts of toxin that are sufficient to incapacitate the phagocytes will an antiinoculum killing mechanism fail to operate.

Regarding the measurement of affinity, it was estimated previously from analyzing the changes in the binding energies for synthetic peptide with increasing degrees of polymerization that a 10-mer peptide constitutes an antibody-binding site (20). Our data, however, indicate that a 10-mer peptide constitutes more than one antibody-binding site. This conclusion is based on the following evidence: (i) The Kd value obtained by a fluorescence anisotropy assay with a 10-mer synthetic peptide was 200-fold lower than that obtained by a fluorescence perturbation assay with a 5-mer synthetic peptide. The huge difference in Kd value when using 10-mer or 5-mer peptides suggests that the 10-mer peptide may contain more than one binding site, and thus the Kd value derived from 10-mer peptides actually may represent avidity. (ii) The antigen competition assay by SPR showed that the 10-mer but not the 5-mer peptide captured by antibody immobilized on the chip was still reactive to antibodies in solution, indicating that one 10-mer peptide contains more than one antibody-binding site. Therefore, the Kd value derived from the 10-mer peptide is an effective Kd, which represents the binding strength of IgG to γDPGA in nature, whereas the Kd value derived from a 5-mer peptide represents intrinsic affinity of the mAbs. In comparison, our chimpanzee/human mAbs have more than 10-fold higher intrinsic affinity than reported for the murine mAbs using a similar measurement method (20). The higher affinity of our mAbs resulted in markedly greater protection than provided by the murine mAbs and also may yield more sensitive diagnostic reagents for detecting γDPGA antigen.

Our studies also examined whether a difference in subclass affected the protective efficacy of the anti-γDPGA mAbs (20). Previous studies using murine mAbs found that all the protective mAbs were of the IgG3 subclass, whereas one nonprotective mAb was of an IgG1 subclass. However, because different mAbs were used, it was not clear whether the difference in protection was related to subclass or to other properties such as binding affinities and binding sites. To address this question, we made IgG1 and IgG3 subclasses for each of the two mAbs by combining the antibody variable domain responsible for antibody binding with constant regions IgG1 or IgG3. The IgG1 and IgG3 of each antibody were compared for their binding affinities, in vitro opsonophagocytic activities, and in vivo protection. We found that the IgG1 and IgG3 subclasses of each mAb exhibited similar binding affinities, in vitro opsonic titers, and protection in vivo against B. anthracis, with the IgG1 subclass providing a higher level of protection than the IgG3 subclass. γDPGA not only is found on the surface of vegetative bacteria but also has also been reported to occur in a soluble form during the systemic phase of the infection (19). Some of the soluble γDPGA was found to be associated with lethal toxin, raising the possibility that γDPGA may play a novel and unexpected role in anthrax pathogenesis (25). Therefore, anti- γDPGA mAbs may have protective effects that extend beyond their demonstrated ability to promote opsonophagocytic killing of bacteria.

We previously have reported the isolation of potent neutralizing mAbs against several anthrax toxin proteins (26–28), and now we report the isolation of two protective γDPGA mAbs. We believe that the use of the antitoxin and γDPGA mAbs in combination may enhance protective efficacy by combining the activities of antitoxin and antibacteria.

Methods

Antigens.

Peptides (10 or 15 amino acids long) representing a fragment of the γDPGA capsule of B. anthracis were synthesized and conjugated to either B. anthracis recombinant protective antigen or tetanus toxoid according to procedures described (14).

Immunization.

Each of the two chimpanzees (AOA006 and AOA007) was immunized i.m. with 0.5 mL of γDPGA conjugated to recombinant protective antigen or tetanus toxoid and adsorbed to alum (25 μg γDPGA conjugates plus 650 μg alum) at weeks 0, 6, and 12. Bone marrow aspirates were taken 5, 7, and 13 wk after the last immunization. The housing and care of the chimpanzees were in compliance with all relevant guidelines and requirements, and animals were housed in facilities that are fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International. All animal study protocols involving chimpanzees were approved by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Animal Care and Use Committee as well as by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the facility housing the animals.

Phage Display Library Construction and Selection.

Bone marrow aspirates from the two immunized chimpanzees were mixed and used for isolation of lymphocytes by centrifugation on a Ficoll-Paque gradient. The total RNA extracted from bone marrow-derived lymphocytes was used for cDNA synthesis using a first-strand cDNA synthesis kit from GE Healthcare. The γ1 heavy-chain Fd (variable and first constant region) cDNA and the κ and γ chain cDNA were amplified by RT-PCR as described (29, 30). Amplified κ- and γ-chain DNA fragments were pooled and cloned into pComb3H at the SacI and XbaI sites, followed by insertion of γ1 Fd chain DNA fragments in the vector at XhoI and SpeI sites. The recombinant plasmid DNA was introduced into Escherichia coli Top 10 (Invitrogen) by electroporation, yielding 1 × 108 individual clones.

Production and selection of the specific phages were performed according to procedures described (29). In brief, the phagemids were rescued by superinfection with helper phage VCS M13 (Stratagene) and were subjected to panning against purified γDPGA for three cycles. After panning, 96 randomly picked single phage-Fab clones were cultured for phage production. The resulting phages were screened for specific binding to γDPGA by phage ELISA (29). Clones that bound to specific antigens but not to BSA were scored as positive.

Expression and Purification of Fab and IgG.

As described (29), Fab was expressed in E. coli and purified primarily on a nickel column, and IgG was expressed in mammalian cells and purified primarily on a protein A column. Both Fab and IgG were purified further through a cation-exchange SP column (GE Healthcare). Purities of the Fab and IgG were determined by SDS/PAGE, and the protein concentrations were determined by spectrophotometer measurement at A280, assuming that 1.35 A280 corresponds to 1.0 mg/mL.

Sequence Analysis of γDPGA-Specific Fabs.

The genes coding for the variable regions of the heavy and light chains of γDPGA-specific Fabs were sequenced. The presumed family usage, germ-line origin, and somatic mutations were identified by comparison with those deposited in the ImMunoGeneTics (IMGT) sequence database (http://imgt.cines.fr).

Affinity Measurements.

The affinities of subclass IgG1 and IgG3 anti-γDPGA mAbs 11D and 4C were measured by using fluorescence anisotropy and tryptophan perturbation assays. Both assays were performed on a PTI steady-state fluorimeter (Photon Technology International) at 20 °C with PBS (Cellgro), pH 7.4, as the working buffer. Fluorescein-labeled γDPGA 10-mer, FAM-γd-(Glu)10 [FAM: 5-(and-6)-carboxyfluorescein], and unlabeled 5-mer, γd-(Glu)5 were synthesized by Biopeptide. The peptides were more than 95% pure by HPLC, and the molecular masses were confirmed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry.

For fluorescence anistropy assay, the association of the γDPGA 10-mer with mAbs was observed as an increase in the fluorescence anisotropy of FAM-γ-d-(Glu)10 measured using the fluorimeter with excitation wavelength (λex) of 492 nm and emission wavelength (λem) of 530 nm. The samples were prepared by mixing FAM-γ-d-(Glu)10 and mAb to obtain 0.1 nM of 10-mer and targeted antibody concentrations (0.001–60 nM). Averages of three readings with a 1-s integration time were recorded.

For the tryptophan fluorescence perturbation assay, the interactions between γd-(Glu)5 and mAbs were quantified by monitoring the change of intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence of the mAbs upon addition of γd-(Glu)5. For the titrations, 0.1 μM of MAb solution was titrated with small aliquots of γd-(Glu)5 dissolved in the working buffer to reach targeted concentrations for each titration point. For each γd-(Glu)5 addition, the complex formation was monitored using fluorescence intensity at λex of 288 nm and λem of 300–400 nm. The total dilution of the MAb solution was <1% over the course of the titrations.

To determine the affinity of 10-mer or 5-mer for MAbs, the normalized fluorescence anisotropy or intensity readings (at 341 nm) were plotted against the titrant concentrations for each titration point, followed by a nonlinear least squares regression analysis of 1:1 binding model using SEDPHAT (sedfitsedphat.nibib.nih.gov), which determined the equilibrium binding constant, Kd. Normalized anisotropy or intensity values were plotted against the total concentration of the titrant (mAbs or 5-mer).

Binding Analysis by SPR.

The SPR biosensor experiments were conducted on a Biacore 3000 instrument (Biacore; GE Healthcare). IgGs were individually immobilized on CM3 sensor chips using standard amine coupling as described (31). For the binding assay, 10-mer or 5-mer γDPGA peptides were injected and allowed to associate for 20 min and to dissociate for 2 h at a flow rate of 5 μL/min. To investigate whether the γDPGA peptides contained more than one antibody-binding site, IgGs were injected after the association of the peptides with the immobilized IgG. An increase in signal upon injection of free IgG is indicative of one or more unbound binding sites on the peptide and, therefore, more than one epitope per peptide.

Opsonophagocytosis.

Spores of B. anthracis (Ames 34 strain) were incubated in a tryptic soy broth medium for 3–4 h in an incubator containing 20% CO2 for germination. The germinated cells were mixed with twofold serially diluted anti-γDPGA mAbs in a 96-well plate. The plate was incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 15 min before addition of colostrum-deprived calf serum (complement source) and human granulocytes. The plate was incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 with shaking at 220 rpm for 45 min. An aliquot of 5 μL from each well was plated onto trypticase soy agar (TSA) plates, and the plates were incubated at 37 °C, in 5% CO2 overnight. Reactions including all the components except antibodies or complement served as negative controls. Cfu on each TSA plate were counted, and opsonophagocytic titer was calculated as a reciprocal of mAb dilution yielding 50% bacterial killing by the Reed–Muench method (32). The mAb dilutions were ln-transformed and plotted, and a linear regression model was applied to determine the relationship between antibody concentration and the opsonophagocytic killing (GraphPad Prism, version 4.0).

Animal Studies.

Female BALB/c mice (age 7–8 wk) were obtained from Harlan. The mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free Select Agent-Animal Biosafety Level 3 facility at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center (UNMHSC) and were allowed at least 7 d to acclimate before challenge. The mice were injected i.p. with various amounts of anti-γDPGA mAbs at various times as indicated in Results, and control animals were treated with either vehicle alone (Dulbecco's PBS, DPBS) or an irrelevant human IgG1 mAb (Synagis; MedImmune). For pulmonary challenge with B. anthracis, the mice were inoculated intratracheally (i.t.) with spores in 50 μL DPBS as previously described (23). Briefly, mice were anesthetized, a small incision was made, and the spores were inoculated directly into the trachea using a bent 30-gauge needle. B. anthracis (Ames strain) spore stocks were prepared as described previously (23, 33), and each inoculum was prepared from an aliquot of frozen stock that was thawed and diluted in DPBS (GIBCO; Invitrogen). The target dose was 104 spores per mouse (≈10 LD50). The actual number of spores deposited in the lung was determined by killing two or three mice after infection, homogenizing the lungs in 1 mL of DPBS, and culturing serial dilutions onto sheep blood agar plates in duplicate, incubating overnight at room temperature, and averaging the number of cfu. The mice were monitored for survival and clinical signs twice daily for 2 wk postchallenge, and the results were evaluated statistically by Kaplan–Meier and logrank (Mantel–Cox) tests (GraphPad Prism, version 4.0). All animal protocols for mouse studies were approved by the UNMHSC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Mahtab Moayeri for helpful discussions and Dr. Haijing Hu for preparing B. anthracis spores for opsonophagocytosis work. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Karginov VA, et al. Treatment of anthrax infection with combination of ciprofloxacin and antibodies to protective antigen of Bacillus anthracis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2004;40:71–74. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00302-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turnbull PC, et al. MICs of selected antibiotics for Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus cereus, Bacillus thuringiensis, and Bacillus mycoides from a range of clinical and environmental sources as determined by the Etest. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:3626–3634. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.8.3626-3634.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Candela T, Mock M, Fouet A. CapE, a 47-amino-acid peptide, is necessary for Bacillus anthracis polyglutamate capsule synthesis. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:7765–7772. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.22.7765-7772.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green BD, Battisti L, Koehler TM, Thorne CB, Ivins BE. Demonstration of a capsule plasmid in Bacillus anthracis. Infect Immun. 1985;49:291–297. doi: 10.1128/iai.49.2.291-297.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Makino S, Uchida I, Terakado N, Sasakawa C, Yoshikawa M. Molecular characterization and protein analysis of the cap region, which is essential for encapsulation in Bacillus anthracis. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:722–730. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.2.722-730.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uchida I, et al. Identification of a novel gene, dep, associated with depolymerization of the capsular polymer in Bacillus anthracis. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:487–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drysdale M, et al. Capsule synthesis by Bacillus anthracis is required for dissemination in murine inhalation anthrax. EMBO J. 2005;24:221–227. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ivins BE, et al. Immunization studies with attenuated strains of Bacillus anthracis. Infect Immun. 1986;52:454–458. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.2.454-458.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Welkos SL. Plasmid-associated virulence factors of non-toxigenic (pX01-) Bacillus anthracis. Microb Pathog. 1991;10:183–198. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(91)90053-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turnbull PC. Anthrax vaccines: Past, present and future. Vaccine. 1991;9:533–539. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(91)90237-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith H, Keppie J, Stanley JL. The chemical basis of the virulence of Bacillus anthracis. I. Properties of bacteria grown in vivo and preparation of extracts. Br J Exp Pathol. 1953;34:477–485. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keppie J, Harris-Smith PW, Smith H. The Chemical Basis of the Virulence of Bacillus Anthracis. Ix. Its Aggressins and Their Mode of Action. Br J Exp Pathol. 1963;44:446–453. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scorpio A, et al. Poly-gamma-glutamate capsule-degrading enzyme treatment enhances phagocytosis and killing of encapsulated Bacillus anthracis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:215–222. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00706-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneerson R, et al. Poly(gamma-D-glutamic acid) protein conjugates induce IgG antibodies in mice to the capsule of Bacillus anthracis: A potential addition to the anthrax vaccine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8945–8950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1633512100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rhie GE, et al. A dually active anthrax vaccine that confers protection against both bacilli and toxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10925–10930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834478100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chabot DJ, et al. Anthrax capsule vaccine protects against experimental infection. Vaccine. 2004;23:43–47. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang TT, Fellows PF, Leighton TJ, Lucas AH. Induction of opsonic antibodies to the gamma-D-glutamic acid capsule of Bacillus anthracis by immunization with a synthetic peptide-carrier protein conjugate. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2004;40:231–237. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00366-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joyce J, et al. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of Bacillus anthracis poly-gamma-D-glutamic acid capsule covalently coupled to a protein carrier using a novel triazine-based conjugation strategy. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:4831–4843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509432200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kozel TR, et al. mAbs to Bacillus anthracis capsular antigen for immunoprotection in anthrax and detection of antigenemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5042–5047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401351101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kozel TR, et al. Protective and immunochemical activities of monoclonal antibodies reactive with the Bacillus anthracis polypeptide capsule. Infect Immun. 2007;75:152–163. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01133-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang TT, Lucas AH. The capsule of Bacillus anthracis behaves as a thymus-independent type 2 antigen. Infect Immun. 2004;72:5460–5463. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5460-5463.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pain RH. Determining the fluorescence spectrum of a protein. In: Coligan JE, et al., editors. Current Protocols in Protein Science. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2005. pp. 7.7.1–7.7.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lyons CR, et al. Murine model of pulmonary anthrax: Kinetics of dissemination, histopathology, and mouse strain susceptibility. Infect Immun. 2004;72:4801–4809. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.8.4801-4809.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robbins JB, Schneerson R, Szu SC. Perspective: Hypothesis: Serum IgG antibody is sufficient to confer protection against infectious diseases by inactivating the inoculum. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1387–1398. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.6.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ezzell JW, et al. Association of Bacillus anthracis capsule with lethal toxin during experimental infection. Infect Immun. 2009;77:749–755. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00764-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Z, et al. Efficient neutralization of anthrax toxin by chimpanzee monoclonal antibodies against protective antigen. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:625–633. doi: 10.1086/500148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Z, et al. Novel chimpanzee/human monoclonal antibodies that neutralize anthrax lethal factor, and evidence for possible synergy with anti-protective antigen antibody. Infect Immun. 2009;77:3902–3908. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00200-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Z, et al. Potent neutralization of anthrax edema toxin by a humanized monoclonal antibody that competes with calmodulin for edema factor binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13487–13492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906581106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen Z, et al. Chimpanzee/human mAbs to vaccinia virus B5 protein neutralize vaccinia and smallpox viruses and protect mice against vaccinia virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1882–1887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510598103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen Z, et al. Characterization of chimpanzee/human monoclonal antibodies to vaccinia virus A33 glycoprotein and its variola virus homolog in vitro and in a vaccinia virus mouse protection model. J Virol. 2007;81:8989–8995. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00906-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schuck P, Boyd LF, Andersen PS. Measuring protein interactions by optical biosensors. In: Coligan JE, Dunn BM, Ploegh HL, Speicher DW, Wingfield PT, editors. Current Protocols in Protein Science. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1999. pp. 20.2.1–20.2.21. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reed LJ, Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am J Hyg. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heninger S, et al. Toxin-deficient mutants of Bacillus anthracis are lethal in a murine model for pulmonary anthrax. Infect Immun. 2006;74:6067–6074. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00719-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]