Abstract

Disruption of the extracellular matrix (ECM) is frequently found in calcific aortic valve disease (CAVD), yet the role of ECM components in valvular interstitial cell (VIC) function and dysfunction remains poorly understood. This study examines the contributions of exogenous and endogenous hyaluronic acid (HA), in both two-dimensional (2D) and 3D environments, in regulating the phenotype and calcification of VICs. VIC calcification was first assessed in a 2D setting in which the cells were exposed to different molecular weights of exogenous HA presented in either an immobilized or soluble form. Delivery of HA suppressed nodule formation in a molecular weight-dependent manner, while blocking VIC recognition of HA via an antibody to CD44 abolished these nodule-suppressive effects and stimulated other hallmarks of valvular dysfunction. These 2D results were then validated in a more physiologically-relevant setting, using an approach that allowed the characterization of VIC phenotype in response to HA alterations in the native 3D environment. In this approach, leaflet organ cultures were analyzed following treatment with anti-CD44 or with hyaluronidase to specifically remove HA. Disruption of VIC-HA interactions upregulated markers of VIC disease and induced leaflet mineralization. Similarly, HA-deficient leaflets exhibited numerous hallmarks of CAVD, including increased VIC proliferation, apoptosis, increased expression of disease-related markers, and mineralization. These findings suggest that VIC-HA interactions are crucial in maintaining a healthy VIC phenotype. Identification of ECM components that can regulate VIC phenotype and function has significant implications for understanding of native valve disease, investigating possible treatments, and designing new biomaterials for valve tissue engineering.

Keywords: hyaluronic acid, valvular interstitial cells, extracellular matrix, heart valve calcification

1. Introduction

Aortic valve disease accounts for over 13,000 deaths per year in the U.S. (Lloyd-Jones et al., 2009), and calcification is the leading cause of aortic valve failure. Valvular interstitial cells (VICs), the most prevalent cells in the valve leaflet, are found in an ‘activated’ phenotypic state in calcified heart valves (Mulholland and Gotlieb, 1996). Changes in the microenvironment such as the introduction of mechanical stresses, the presence of various cytokines, and changes in extracellular matrix (ECM) composition are all factors that can stimulate VICs to become activated (Cushing et al., 2005; Rabkin et al., 2001; Walker et al., 2004). These activated VICs can express numerous cytokines and growth factors that are characteristic of either a myofibroblast or osteoblast-like phenotype. VIC differentiation into a myofibroblast phenotype is distinguished by marked cell contraction and an increase in the expression of alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), often leading to pathological remodeling of the ECM by VICs in vitro (Walker et al., 2004). Prolonged activation of this myofibroblast phenotype is believed to be associated with dystrophic calcification, which is found in approximately 83% of calcified valves (Mohler et al., 2001). This calcification is also accompanied by dramatic increases in proliferation and apoptosis in the normally quiescent VIC population. Meanwhile, activation of VICs into an osteoblast-like phenotype is indicated by increased expression of alkaline phosphatase (ALP), osteocalcin (OCN), and core binding factor-α1 (CBFa-1) (Jian et al., 2003; Mohler et al., 1997; Mohler et al., 2001; Srivatsa et al., 1997), and may eventually lead to the formation of calcific nodules via ossification. The formation of nodules via either dystrophic or ossific processes can cause valve stiffening, thereby obstructing ventricular outflow.

The aortic valve is a thin micro-structure with a surprisingly complex composition. It has three main layers containing a specific distribution of ECM components which include glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), elastin, and collagen. Although disarray of the extracellular matrix is often found in calcified valves (Hinton et al., 2006), the role of ECM composition in valve dysfunction and disease progression remains poorly understood. Recent studies in our lab have shown that individual matrix components differentially regulate the in vitro calcification of VICs (Rodriguez and Masters, 2009).

There is increasing evidence that the GAG component of the valve in particular plays many interesting roles in regulating leaflet function. GAGs are highly expressed in fetal valves (Aikawa et al., 2006), and, with age, certain GAGs become more localized and abundant in specific regions of the valve that receive more compression during the cardiac cycle (Stephens et al., 2008). Hyaluronic acid (HA) is a major component of the valve ECM; it is found in the spongiosa layer of the valve leaflet and comprises 60% of the total GAG content in the heart valve (Stephens et al., 2008). In normal valves, HA concentration has been shown to increase with age (Stephens et al., 2008). However, disruption of the extracellular matrix that results in altered HA composition can be pathological. While HA abundance has been associated with myxomatous valves, failure of bioprosthetic valves has been related to a decrease in HA (Grande-Allen et al., 2003b; Gupta et al., 2009; Vyavahare et al., 1999). These observations suggest that HA is an important component of the valve ECM. It provides resistance to compression and the maintenance of equilibrium between HA synthesis and degradation is necessary for proper valve function.

Moreover, previous studies have indicated that VICs are highly responsive to HA with respect to proliferation and extracellular matrix production (Masters et al., 2005; Shah et al., 2008). VICs are known to express CD44, a cell-surface receptor for HA that mediates HA-initiated signaling cascades (Masters et al., 2005; Latif et al., 2007; Turley et al., 2002). Although the effects of HA binding to CD44 are strongly cell type-dependent, this interaction can impact numerous cell functions such as adhesion, proliferation, migration, ECM production, as well as angiogenesis (Turley et al., 2002). The ability of HA to concurrently affect such a wide array of cell functions is thought to be due to the interactions of CD44 with multiple intracellular binding partners, thereby coordinating “cross-talk” across several different intracellular signaling pathways (Turley et al., 2002). In the context of vascular diseases, expression of CD44 is associated with increased atherosclerosis (Cuff et al., 2001; Slevin et al., 2007), although the impact of CD44 expression or inhibition in valve tissue has yet to be determined.

While many studies have examined the effects of HA on the function of various cell types, much remains to be learned regarding the response of VICs to exogenous HA and their interaction with endogenous HA, particularly with respect to VIC differentiation and calcification. For this reason, the goal of the current work is to understand the role of VIC-HA interactions in the regulation of valve calcification. Thus, in this work we present two different approaches to study VIC-HA interactions in the context of VIC phenotype. First, we explore a “bottom-up” approach in which characterization of VIC phenotype upon interaction with various molecular weights of immobilized and soluble exogenous HA is achieved in a 2D environment. Second, to validate our 2D results in a more physiologically-relevant setting, we introduce a “top-down” approach that allows the characterization of VIC phenotype in response to alterations of HA presentation in a native 3D environment. Understanding the individual contribution of HA, a major valve ECM component, to valvular disease will not only have a significant impact on the tissue engineering field, but will also help us to better understand calcific valve etiology and identify potential targets for treatment.

2. Results

2.1. Nodule-Forming VIC Cultures Contain Less HA

Previous work has shown that the degree of culture calcification is highly dependent on the type of ECM coating upon which VICs are cultured (Rodriguez and Masters, 2009). Specifically, VICs cultured on fibrin-coated surfaces had a high number of nodules and expressed markers that are indicative of a diseased phenotype. On the other hand, VICs cultured on collagen-coated surfaces exhibited resistance to in vitro nodule formation even after treatment with pro-calcific growth factors. In the present work, quantification of ECM composition after culture on these surfaces revealed that VICs on collagen (the ‘non-calcifying’ environment) produced a significantly higher amount of HA than VICs cultured on fibrin or TCPS (the calcifying environments) (Figure 1, P<0.05), thereby implicating HA as a potential factor in maintaining a non-calcifying VIC phenotype. The resulting hypothesis – that VIC-HA interactions help to maintain a non-pathological VIC phenotype – was further explored in subsequent experiments.

Figure 1.

Higher levels of hyaluronic acid (HA) were found when VICs were cultured on collagen (Coll) when compared to fibrin (FB) and tissue culture polystyrene (TCPS). *P<0.05 compared to FB and TCPS.

2.2. Effect of Immobilized HA on VIC Dysfunction

Motivated by the findings observed in Figure 1, we aimed to investigate the role of HA in VIC calcification through a “bottom-up” approach. Immobilization of different molecular weights of HA on TCPS surfaces resulted in a decrease in nodule formation when compared against unmodified TCPS (Figure 2A). While all HA molecular weights were successful at decreasing nodule formation, VICs cultured upon the 64 kDa HA exhibited the lowest number of nodules per well (P<0.005). To demonstrate that the decrease in nodules was directly related to VIC interaction with the immobilized HA, the culture medium was supplemented with 0.5 µg/mL anti-CD44, an antibody that blocks the major binding receptor for HA. Treatment with anti-CD44, but not with the isotypic control, resulted in a reversal of the effects of immobilized HA on VICs, increasing the number of nodules to values similar to those found for the TCPS control (Figure 2A). Similar to the trend observed in Figure 2A, the average nodule size and total nodule area tended to decrease on the HA-treated surfaces when compared to the TCPS control (Figures 2B and 2C, P<0.05). Furthermore, total calcium content in VIC cultures followed the same trend as the total number of nodules (Figure 2D), and suggested that the nodules were indicative of culture calcification.

Figure 2.

Culture of VICs upon 2-D substrates modified with immobilized HA in a range of molecular weights led to decreases in: (A) nodule number, (B) average size of individual nodules, (C) total calcified area, and (D) calcium content. Treatment with anti-CD44 reversed the suppressive effects of immobilized HA on nodule number (A, hatched bars). Treatment with an isotypic control antibody did not impact nodule formation (A, empty bars). *P<0.05 compared to TCPS for all panels.

2.3. Effect of Soluble HA on VIC Dysfunction

To further investigate the calcification-suppressing effects of HA in VIC cultures, various molecular weights of HA were also presented to VICs in a soluble form. The HA was added directly to the cell culture medium of VICs cultured on TCPS. As shown in Figure 3A, there was a distinct trend in nodule formation relative to HA molecular weight. Namely, increasing the molecular weight of the HA led to increased efficacy in inhibiting nodule formation in VIC cultures. To determine whether the decrease in nodules was a direct result of VIC recognition of HA in the medium, anti-CD44 or a non-immune isotype-matched antibody control was added to the culture medium concurrently with the soluble HA. After five days, the addition of anti-CD44 resulted in a greatly reduced efficacy of HA to decrease nodule formation when compared to control conditions (Figures 3A). Addition of the control antibody did not reverse the effects of soluble HA, thus corroborating the conclusion that recognition of HA by VICs via the CD44 receptor had an influence on nodule formation (Figure 3A). Treatment with HA did not yield significant changes in average nodule size (Figure 3B), but, consistent with the trend observed for total nodule number, both total nodule area and total calcium content decreased with an increase in HA molecular weight (Figures 3C and 3D).

Figure 3.

VICs in 2-D culture were treated with different molecular weights of exogenous HA in solution and evaluated for: (A) nodule number, (B) average size of individual nodules, (C) total calcified area, and (D) calcium content. Treatment with anti-CD44 reversed the suppressive effects of soluble HA on nodule number (A, hatched bars). Treatment with an isotypic control antibody did not impact nodule formation (A, empty bars). P<0.05 compared to TCPS for all panels.

2.4. Disruption of VIC-HA Interactions in Native Leaflets

Our findings in the previous sections suggest that binding of VICs to HA via the CD44 receptor is important in regulating in vitro calcification, as a decrease in nodule formation was observed in the presence of HA (Figures 2 and 3). Furthermore, as shown in Figure 4, CD44 is expressed in native porcine leaflets. Thus, these results inspired us to take a “top-down” approach to quantifying VIC-HA interactions by blocking the major HA-binding receptor, CD44, in the native 3D microenvironment. After 6 days of culture, native porcine leaflets treated with anti-CD44 experienced an increase in cell proliferation and apoptosis compared to both untreated leaflets and leaflets treated with a control antibody (Figure 5, P<0.05). Furthermore, immunohistochemical staining revealed that blocking this HA receptor increased the expression of several markers of VIC dysfunction – α-SMA, ALP, and CBFa-1 – compared to the isotypic and untreated controls (Figure 6A). Quantification of these markers via western blot confirmed a significant increase in the expression of ALP and CBFa-1 in leaflets that were treated with anti-CD44 when compared to the control (Figure 6B, P<0.05). In addition, positive Von Kossa staining indicated an increase in tissue mineralization after blocking the CD44 receptor, as shown in Figure 6C.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical detection of the expression of CD44 in native valve leaflets; CD44 (left), DAPI (center), merged pictures (right). Scale bar = 100 µm.

Figure 5.

Native valve leaflets were treated with anti-CD44 over 6 days of in vitro culture and then analyzed for: (A) VIC proliferation, and (B) VIC apoptosis. n=6 samples per condition, *P<0.01 compared to untreated control.

Figure 6.

Treatment of native valve leaflets with anti-CD44 for a period of 6 days resulted in significantly elevated expression of several phenotypic markers of valve disease, as indicated by: (A) immunohistochemical detection of alpha smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; left), alkaline phosphatase (ALP; center) and core binding factor alpha 1 (Cbfa-1; right), (B) western blot for α-SMA, ALP, and CBFa-1, and (C) Von Kossa staining to detect mineralization (black). *P<0.05 compared to control. Scale bar = 100 µm.

2.5. Depletion of HA from the Native ECM

To further investigate the role of HA in regulating the phenotype and calcification of VIC cultures, HA was removed from native aortic valve leaflets via targeted enzymatic digestion. Since the in vitro culture of native leaflets following targeted ECM-depletion is a new method for exploring the contributions of individual ECM components to VIC function in a 3-D environment, it was necessary to first validate the feasibility of this technique. Figure 7 demonstrates that this ECM-depletion method is effective in removing solely the target ECM component from the native leaflet. Specifically, hyaluronidase (HY-ase) treatment was highly effective in removing 15.4 or 100% of the HA (Figure 7A) without altering the amounts of collagen (Figure 7B), sulfated GAGs (Figure 7C), or cellularity (Figure 7D) in the leaflet. However, while removing 15.4% of the total HA did not affect leaflet mechanics (Figure 7E), complete removal of HA did result in a significant increase in the Young’s Modulus when compared to the control condition (P<0.05).

Figure 7.

Native leaflets were treated with two concentrations of hyaluronidase (HY-ase), followed by biochemical and mechanical characterization of the treated leaflets to validate this HA-depletion method. Quantitative assays were performed on the leaflets to measure: (A) HA, (B) collagen, (C) sulfated GAGs, (D) DNA, and (E) Young’s Modulus. *P<0.05 compared to untreated leaflet.

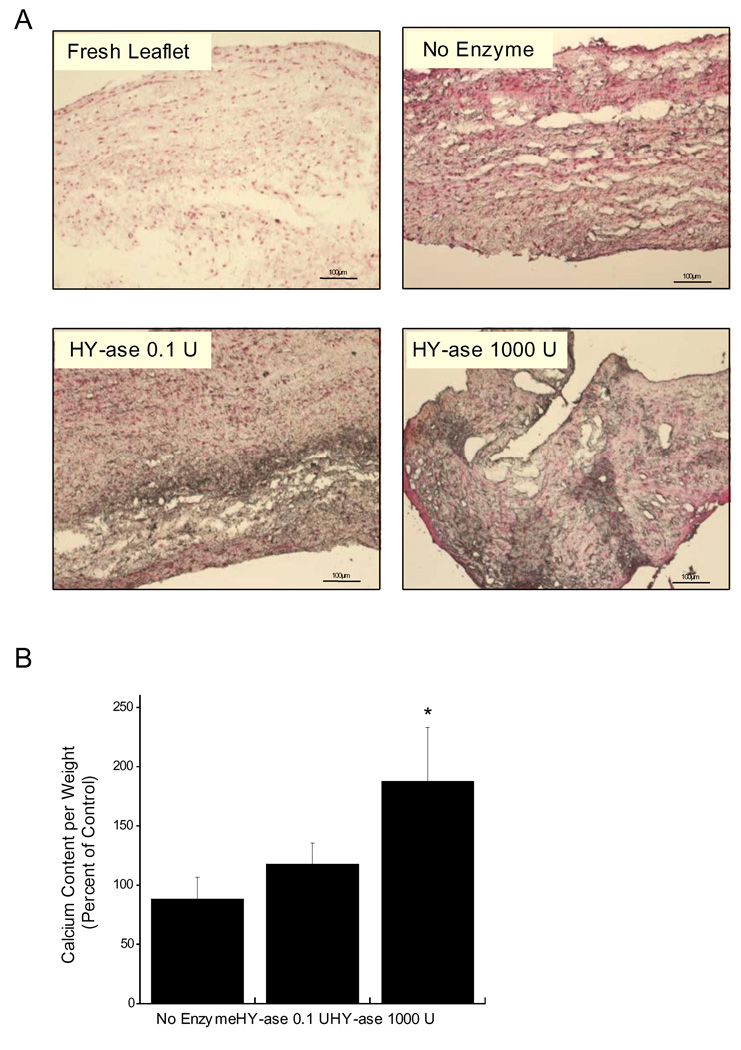

Following this confirmation of the feasibility of using HY-ase to preferentially remove HA from the leaflets with minimal disruption of other leaflet ECM components or cellularity, these altered living leaflets were then used to examine how the loss of HA from the VIC’s native environment impacted VIC phenotype. Characterization of the HA-deficient leaflets after 6 days of culture demonstrated that partial or total removal of HA from the native leaflet had a significant impact on VIC proliferation, apoptosis, and phenotype. A significant increase in proliferating and apoptotic cells was observed on HY-ase treated leaflets when compared to the untreated control (Figure 8, P<0.05). Furthermore, immunohistochemical staining of HA-depleted leaflet sections (Figure 9) revealed an increase in the expression of α-SMA, ALP, and CBFa-1, markers for myofibroblast and osteoblast phenotypes, relative to the undepleted control. As observed in Figure 10, quantification of these markers via western blot revealed that their expression was dependent upon the amount of HA removed. While α-SMA did not change across the different conditions, only complete removal of HA from the native ECM resulted in a significant increase in the expression of ALP and CBFa-1 (P<0.05). Interestingly, both partial and total HA removal resulted in an increase in mineralization of the leaflets as indicated by positive Von Kossa staining (Figure 11A). However, only complete removal of HA resulted in a statistically significant increase in total calcium content (Figure 11B).

Figure 8.

Effect of HA removal from native leaflets on: (A) VIC proliferation, and (B) VIC apoptosis after 6 days of in vitro culture. n=6 samples per condition, *P<0.01 compared to no enzyme control.

Figure 9.

Effect of HA depletion on the expression of phenotypic markers of valve disease following 6 days of in vitro leaflet culture, as evaluated by immunohistochemical detection of: α-SMA (left), ALP (middle), and Cbfa-1 (right). Top to bottom: Day 0, no enzyme, HY-ase 0.1 U, and HY-ase 1000 U. Scale bar = 100 µm.

Figure 10.

Effect of HA depletion on the expression of phenotypic markers of valve disease following 6 days of in vitro leaflet culture, as evaluated by western blot detection of: (A) α-SMA, (B) ALP, and (C) Cbfa-1. All results are normalized to β-tubulin. *P<0.05 compared to untreated leaflet.

Figure 11.

Effect of HA depletion on VIC mineralization following 6 days of in vitro leaflet culture, as determined by: (A) von Kossa staining for mineralization; calcium deposits are stained in black, and (B) calcium content. *P<0.05 compared to untreated leaflet. Scale bar = 100 µm.

3. Discussion

Much remains to be learned about the etiology of heart valve calcification, although several studies have highlighted the importance of the valve extracellular matrix in maintaining not only the mechanical, but also the biological, functions of the valve (Benton et al., 2008; Cushing et al., 2007; Grande-Allen et al., 2003a; Rodriguez and Masters, 2009; Stephens et al., 2009; Vesely, 1998). A major component of the valve’s ECM, hyaluronic acid is not only able to regulate VIC proliferation and ECM production, but has also proven attractive as a scaffold material for heart valve tissue engineering (Masters et al., 2005; Ramamurthi and Vesely, 2005; Shah et al., 2008). Thus, herein we investigated, by two different approaches, the role of HA in VIC calcification in order to better understand the contribution of individual ECM components to calcific valve etiology and inform the design of scaffold materials for valve tissue engineering. Our findings suggest that the VIC-HA interaction is necessary to maintain a healthy VIC phenotype, and that disruption of these VIC-HA interactions in both 2D tissue culture and 3D organ culture environments can induce VIC activation to a pathological phenotype.

In our “bottom-up” approach, interaction of VICs with immobilized and soluble HA in 2D cultures showed that calcification is dependent upon the HA molecular weight, as demonstrated by the decrease in nodule formation, total nodule area, and total calcium content observed for various molecular weights of both immobilized and soluble forms of HA. These results are consistent with previous findings where the effects of HA on the function of several other cell types were found to be molecular weight-dependent (Allison et al., 2009; Masters et al., 2005; Slevin et al., 2007). The delivery of HA fragments by weight, rather than by molarity, is consistent with standard practice for delivering exogenous HA (Allison et al., 2009; Croce et al., 2003; Ibrahim and Ramamurthi 2008; Joddar et al., 2006; Masters et al., 2005; Slevin et al., 2002). However, it should be noted that one potential limitation of the current work is that this approach results in a different number of HA molecules delivered to the conditions, which has the potential to influence the findings presented for the 2D cultures.

Although not the focus of the current study, it is worth noting that one potential mechanism for HA-based regulation of VIC calcification and phenotype may be the ability of HA to attenuate the cellular response to TGF-β1, a potent pro-calcific factor that is found in high concentrations in excised calcified valves and is the subject of many VIC dysfunction studies (Jian et al., 2003; Locci et al., 1995; Mohler et al., 1999; Webber et al., 2009). Smad3 phosphorylation is a critical step in TGF-β1-initiated signaling, and preliminary studies by our group indicate that lower levels of phospho-Smad3 accompany the decrease in calcification found in VIC cultures treated with exogenous soluble HA (see Supplementary Material). This finding is consistent with trends identified in other cell types, where HA was found to attenuate the cellular response to TGF-β1 (Ito et al., 2004). As noted earlier, numerous intracellular signaling cascades are affected by HA-CD44 binding (Turley et al., 2002), so it is possible that multiple other signaling molecules, such as Rho and Rac, also participate in regulating the cellular responses documented in the current work.

Previous work has demonstrated that VICs recognize HA via the CD44 receptor (Hellstrom et al., 2006; Masters et al., 2005). In the current study, administration of a neutralizing antibody to CD44 abolished the nodule-suppressing effects of HA delivered in either soluble or immobilized form, confirming that the documented calcification trends were directly attributable to VIC interaction with HA. Treatment of VICs with anti-CD44 also dramatically increased proliferation and apoptosis, which is meaningful because increases in these functions also serve as early hallmarks of valvular disease (Gu and Masters, 2009; Jian et al., 2003; Kaden et al., 2003). The effectiveness of HA in reducing nodule formation and α-SMA expression was also dependent upon the method of presenting the HA to the cells. Specifically, while immobilized HA was more effective at reducing nodule number, total nodule area, and total calcium content when delivered in a low molecular weight range (Figure 2), soluble HA achieved the greatest reduction in calcification only when delivered at the two highest molecular weights (Figure 3). Overall, treatment with either immobilized or soluble HA achieved similar reductions in nodule number and calcium content, although immobilization of HA was more effective at reducing nodule size, and hence total calcified area.

In other cell types, it has been found that exogenously-delivered HA has a different effect on cell response and tissue organization than endogenously produced HA (Allison et al., 2009; Chao and Spicer, 2005; Webber et al., 2009). Therefore, we investigated whether our 2D findings could be translated to a more physiologically-relevant environment by implementing a “top-down” approach to study the effect of endogenous HA in VIC calcification in a 3D setting. Strikingly, blocking the CD44 receptor in native valve leaflets increased the expression of ALP and CBFa-1 and the deposition of calcium, suggesting that interruption of the VIC-HA interaction in the native environment activates an osteoblast-like phenotype. These trends were further investigated by performing a study using an ECM-depletion method that allows the examination of the contribution of individual matrix components in valvular disease. As shown in Figure 7, this method can be tailored to remove from the native environment only the ECM component of interest (in this case, HA) without altering cellularity, tissue mechanics, or other ECM proteins. Although HY-ase can cross-react with other polysaccharides, using this method we were able to successfully remove 15.4% or 100% of the total HA, thus creating living, HA-deficient leaflets without significantly affecting the quantity of other GAGs in the leaflet. Similar to the results obtained upon the disruption of VIC-HA interactions via anti-CD44, removal of HA from leaflets also caused an increase in apoptosis and proliferation, which can contribute to valve pathology (Gu and Masters, 2009; Jian et al., 2003; Kaden et al., 2003). Although immunohistochemical staining qualitatively indicated an increase in osteogenic markers with either partial or total HA depletion of leaflets, only total depletion of HA led to a significant increase in these markers when measured via quantitative techniques. It is possible that the differences in protein expression detected via immunostaining appeared greater than those detected by Western blotting due to the well-documented heterogeneity of the VIC population (Liu et al., 2007). The presence of a heterogeneous cell population can diminish the detection of changes in protein expression when using analysis techniques – such as Western blotting – that require tissue homogenization.

It should be noted that leaflets completely depleted of HA demonstrated increased stiffness, which can also regulate VIC phenotype (Kloxin et al., 2010; Yip et al., 2009). However, there are multiple factors that suggest that HA content, and not mechanics, was predominantly responsible for the alterations in VIC phenotype observed in HA-depleted valves in the current study. First, immunohistochemical evaluation demonstrated that partial HA depletion was capable of increasing numerous markers of VIC disease in the absence of significant mechanical changes. Second, although leaflets fully depleted of HA were stiffer than controls, previous work by others has shown that it is actually softer matrices that tend to promote VIC activation to an osteoblast-like phenotype, while stiffer matrices stimulate more myofibroblastic differentiation (Yip et al., 2009). In our work, we saw a significant upregulation of osteoblast-like activity in the stiffer, high HY-ase dose condition, which is not the trend that would be expected if the phenotypic changes were guided primarily by mechanics. Lastly, our anti-CD44 treated leaflets, which had the same stiffness as the untreated condition, also strongly expressed osteogenic markers, implying that the significant increase in ALP and CBFa-1 observed in the total HA-depleted leaflets was due to the absence of HA and not primarily due to changes in tissue mechanics. Although the culture setting of these leaflets does not completely resemble the physiological environment, as they were cultured under static conditions, the results obtained from these HA-deficient leaflets strongly agree with our 2D findings in that the interaction of VICs with HA is favorable for maintaining a healthy VIC phenotype.

The findings presented herein emphasize the importance of an HA-rich environment for maintaining a healthy VIC phenotype, which is of great relevance to both the elucidation of valvular disease etiology and the development of tissue-engineered valve replacements. This work not only shows that the incorporation of exogenous HA can regulate VIC calcification in a molecular weight-dependent manner but it also demonstrates that the deficiency of endogenous HA leads to a diseased VIC phenotype. Furthermore, in this study we introduce a method that allows the removal of individual matrix components without impacting cellularity and tissue structure leading to a “synthetically-diseased” leaflet that can be used as an in vitro model to study valvular disease progression and target possible treatments.

4. Materials and Methods

Unless otherwise stated, all products are from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO. Data were compared using ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test, or a student’s t-test where appropriate, for which statistical significance was defined as P≤0.05. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

4.1. VIC Isolation and Culture

VICs were isolated from porcine aortic heart valves (Hormel, Inc., Austin, MN) by collagenase digestion (Johnson et al., 1987). In brief, valve leaflets were excised and placed into a wash solution of Medium 199 (pH 7.4) supplemented with 200 U/ml penicillin and 200 µg/ml streptomycin. Leaflets were then transferred to a filter-sterilized solution of 0.6 mg/ml collagenase type II (Worthington Biochemical Corp., Lakewood, NJ) and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes with shaking to remove endothelial cells. The supernatant from this initial digestion was removed, and the leaflets were then incubated at 37°C for 60 minutes in fresh collagenase solution (0.6 mg/ml) to dissociate the VICs from the valve extracellular matrix. VICs were cultured in Medium 199 (pH 7.4) supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, and 15% (v/v) FBS (Hyclone, Logan, UT) and used between passages 2–4 for all experiments.

Unless otherwise specified, VICs used in all 2D experiments were seeded at a density of 50,000 cells/cm2 onto 24-well plates. During the execution of experiments, the VICs were cultured in low-serum medium (1% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine, in Medium 199), and the medium was changed every other day until Day 5.

4.2. HA Quantification in VIC Cultures

Total HA was quantified in VICs that were cultured on a pro-calcific ECM substrate (fibrin) and on an ECM component that does not support VIC calcification (collagen type I) (Rodriguez and Masters, 2009). To quantify total HA, cells were lysed in radio-immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1% Igepal CA 630, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 50 mM Trizma HCl, pH 7.5) with 19 U/mL papain (Worthington Biochemical Corporation, Lakewood, NJ) at 60°C for 6 hours. The amount of HA in the samples was determined using a quantitative HA test kit (Corgenix, Broomfield, CO), which detects HA based upon the binding of HA to a labeled HA binding protein. The absorbance of samples and HA standards was read at 450 nm on a microplate reader (Synergy HT, Biotek Instruments, Winooski, VT).

4.3. Culture on HA Coatings

Wells of tissue culture polystyrene (TCPS) 24-well plates were coated by adsorption of HA (sodium salt, from Streptococcus equi, 4.7, 64, 107 and 4000 kDa; Lifecore, Chaska, MN and Sigma-Aldrich) from a 25 µg/ml HA solution prepared in 50 mM bicarbonate coating buffer (pH 9.6), followed by incubation overnight at 4°C. Control wells were left uncoated, and all wells were rinsed once with PBS prior to cell seeding. Coating efficiency was assessed using a quantitative HA test kit (Corgenix). Cells were seeded as described in section 4.1. After five days of culture, cells were fixed, lysed, or homogenized for quantification of calcification and phenotype as described in subsequent sections. These experiments were also repeated in the presence of 0.5 µg/ml anti-CD44 (rat IgG2b, low-endotoxin, azide-free, Clone IM7; Biolegend, San Francisco, CA) or a non-immune, isotype-matched rat IgG2b (0.5 µg/ml, Clone RTK4530; Biolegend) in order to determine whether cell function outcomes could be directly attributed to cellular recognition of HA via the main HA receptor (CD44).

4.4. Treatment with HA in Solution

VICs were seeded onto unmodified (TCPS) 24-well plates as described in section 4.1. One day following cell seeding, the culture medium in the wells was removed and the VICs were treated with 10 µg/ml of HA in a range of molecular weights (4.7, 64, 107 and 4000 KDa), or left untreated. These experiments were also repeated in the presence of 0.5 µg/ml anti-CD44 or 0.5 µg/ml isotype-matched control. After five days of culture, cells were fixed, lysed, or homogenized for quantification of calcification as described in subsequent sections.

4.5. Nodule Quantification

To clearly visualize calcific nodules formed after five days of culture, VICs were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and stained with 2% Alizarin Red S (ARS) for 15 minutes with shaking at room temperature. Samples were then washed four times with deionized water (diH2O) and the nodules in each well were quantified via manual counting under a microscope (Olympus IX51 microscope with epi-fluorescence, Olympus, Center Valley, PA). Nodule size analysis was performed using NIH ImageJ Software. Every positively-stained nodule in every well in each of three duplicate experiments was measured in area.

4.6. Assessment of Mineralization by ARS Extraction

Calcium content was quantified by performing extraction of ARS staining (described in section 4.5) (Gregory et al., 2004). In brief, stained cultures were incubated at −20°C for 1 hour followed by 30 minutes incubation with 10% acetic acid at room temperature (RT) with shaking. After incubation, cells and nodules were scraped from the wells and transferred to a microcentrifuge tube, vortexed for 30 seconds and heated at 85°C for 10 minutes. Mineral oil was added to the solution to avoid evaporation while heating. Samples were then cooled on ice for 5 minutes and centrifuged at 20000 × g. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and mixed with 10% ammonium hydroxide. Absorbance of the resulting solution was read at 405 nm on a microplate reader (Synergy HT, Biotek Instruments, Winooski, VT).

4.7. Treatment of Native Leaflets with anti-CD44

To identify expression of CD44 by VICs in the native environment, leaflets were excised from porcine aortic valves as described in section 4.1 and washed in a solution of Medium 199 (pH 7.4) supplemented with 200 U/ml penicillin and 200 µg/ml streptomycin. Leaflets were denuded of endothelial cells, cut in half, and fixed in 10% formalin. Following fixation, leaflets were embedded in tissue freezing medium for 6 hours at −80°C, and sectioned into 7 µm slices using a cryostat (HM 505-E, Microm International GmbH, Walldorf, Germany). Tissue sections were washed four times with diH2O water prior to immunohistochemical staining for anti-CD44. Sections were blocked overnight with a 5% BSA solution in PBS at RT, followed by application of primary antibody diluted in 1% BSA in PBS. After overnight incubation at 4°C, the sections were thoroughly rinsed in PBS and reacted with goat anti-rabbit AlexaFluor 488 IgG (2 µg/mL; Invitrogen) for 1 hour and sections were counterstained with DAPI (1 µg/ml). Fluorescent images of the stained sections were captured using a microscope (Olympus IX51 microscope with epi-fluorescence, Olympus, Center Valley, PA).

To translate our 2D experiments to a more physiologically-relevant environment, we blocked CD44 in native porcine aortic valve leaflets. For this experiment, leaflets were excised from porcine aortic valves as described in section 4.1 and washed in a solution of Medium 199 (pH 7.4) supplemented with 200 U/ml penicillin and 200 µg/ml streptomycin. Leaflets were denuded of endothelial cells, cut in half, and cultured attached to non-adhesive silicone bases at 37°C in VIC growth medium containing 15% FBS supplemented with 1.5 µg/mL anti-CD44 or 1.5 µg/mL isotype-matched control antibody. Culture medium was changed and supplemented with anti-CD44 or control antibody every other day for a period of 6 days. After culture, leaflets were fixed or digested for analysis of cell proliferation, apoptosis, or phenotype via methods specified in sections 4.11, 4.12 and 4.13.

4.8. Depletion of HA from Native Valve Leaflets

To further investigate the role of HA in native aortic valve function, HA was removed from native valve leaflets by targeted enzymatic digestion. Leaflets were excised from porcine aortic valves and washed in a solution of Medium 199 (pH 7.4) supplemented with 200 U/ml penicillin and 200 µg/ml streptomycin. This was followed by a 1.5 hour incubation at 37°C with shaking in a filter-sterilized solution of 0.1 or 1000 U hyaluronidase (type II, from bovine testes). Leaflets were denuded of endothelial cells, cut in half, and cultured attached to non-adhesive silicone bases at 37°C in VIC growth medium containing 15% FBS. Untreated native leaflets were used as controls.

4.9. Validation of Targeted HA Depletion Method

To validate the effectiveness of HY-ase digestion to selectively remove HA from native valve leaflets, enzyme-treated leaflets were freeze-dried for 72 hours, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, pulverized, and incubated in a papain solution (19 U/mg papain (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ), 10mM cysteine in PBE buffer) overnight at 60°C with shaking. Following digestion, samples were homogenized by vortexing and used for detection of total collagen, HA, sulfated glycosaminoglycans (sGAGs), and DNA. Total collagen was indirectly measured by detecting the total amount of hydroxyproline in the leaflet digest (Woessner, 1961), wherein hydroxyproline accounts for 13.3% of total collagen (Goll et al., 1963). The amount of sGAG was quantified by the dimethyl methylene blue (DMMB) assay and compared against chondroitin sulfate standard solutions as previously reported (Barbosa et al., 2003). Total HA was detected as specified above for cell cultures. To verify that the HA-depletion method did not affect cellularity, total DNA content was measured by the Pico Green assay (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). All results were normalized to leaflet dry weight.

4.10. Mechanical Properties

In order to evaluate the impact of ECM depletion on tissue strength and stiffness, enzyme-treated leaflets were cut into longitudinal strips (4.5 mm wide, radial region) and mechanically tested in tension (Instron Model 5548 MicroTester) to calculate the leaflet Young’s modulus, as has been described elsewhere for the mechanical characterization of heart valves (Hoerstrup et al., 2002). Testing was performed in an environmental chamber filled with PBS and held at physiological temperature (37°C).

4.11. Proliferation and Apoptosis

Proliferating VICs in cultured leaflets were visualized and quantified using the Click-It EdU Cell Proliferation Imaging System (Invitrogen). Labeling of VICs with EdU was performed as specified by the manufacturer. EdU was added to the media on day 5 of leaflet culture and incubated overnight. On day 6, leaflets were flash-frozen and tissue sections were prepared as specified in section 4.7. Detection of EdU was achieved by a copper-catalyzed reaction resulting in fluorescence that was visualized using an Olympus IX51 microscope with epi-fluorescence, and sections were counterstained with DAPI (1 µg/ml). Total proliferating cells in leaflet sections were quantified and divided by total cell number using NIH ImageJ Software to yield the percent proliferating cells.

Apoptotic VICs in the leaflets were visualized using the ApopTag Red In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA). After culture, leaflets were fixed in 10% paraformaldehyde in PBS, pH 7.4 for 1 hour at RT followed by post-fixation in pre-cooled ethanol:acetic acid solution (2:1) for 5 minutes at −20°C. Tissue sections were prepared as specified above. After application of the equilibration buffer, TdT enzyme was incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. Subsequent TdT detection was performed by incubating with anti-digoxigenin conjugate for 30 minutes at RT. Apoptotic cells in DAPI-counterstained leaflet sections were visualized using an Olympus IX51 microscope. Total apoptotic cells in leaflet sections were quantified and divided by total cell number using NIH ImageJ Software to yield the percent apoptotic cells.

4.12. Characterization of Cell Phenotype in Leaflets

Histological analysis for markers of a diseased VIC phenotype was performed on anti-CD44-treated and on HA-depleted leaflets. After culture, leaflets were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and prepared for sectioning as described in section 4.7. Tissue sections were washed four times with diH2O water prior to immunohistochemical staining for alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and core binding factor-alpha1 (CBFa-1). Sections were blocked overnight with a 5% BSA solution in PBS at RT, followed by application of primary antibodies diluted in 1% BSA in PBS: anti-α-SMA (mouse clone 1A4, 5 µg/mL), anti-ALP (mouse clone AP-59, 1:1000), and anti-CBFa-1 (rabbit, 2 µg/mL, Alpha Diagnostic International, San Antonio, TX). After overnight incubation at 4°C, the sections were thoroughly rinsed in PBS and reacted with either goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit AlexaFluor 488 IgG conjugates (2 µg/mL; Invitrogen) for 1 hour. Fluorescent images of the stained sections were captured using a microscope (Olympus IX51 microscope with epi-fluorescence, Olympus, Center Valley, PA). The leaflet orientation and region that is displayed is comparable across all photomicrographs.

Tissue mineralization was detected by visualization of calcium deposition in the sections via Von Kossa staining. Tissue sections were incubated in a 5% silver nitrate solution for 1 hour under ultraviolet light and counterstained with 0.1% nuclear fast red (Acros Organics) for 5 minutes. Calcium deposits were identified by black staining and images were captured using an Olympus IX51 microscope. To quantify calcium content, leaflets were stained for 1 hour with ARS (section 4.5), flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and pulverized, followed by ARS extraction as specified in section 4.6.

4.13. Quantification of Calcific Markers by Western Blot

Characterization of VIC phenotype was performed by quantifying the expression of markers characteristic of the myofibroblast and osteoblast phenotype. Cultured cells or tissue specimens were lysed with a 20% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) lysis buffer. The total amount of protein was quantified via the Micro BCA Assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Separation of proteins in the lysate was performed by gel electrophoresis using 4–12% Bis-Tris NuPage Gels (Invitrogen). Blotting onto a nitrocellulose membrane and subsequent blocking were performed using standard western blotting techniques. Blot membranes were then incubated with primary antibodies (anti-αSMA, anti-ALP, anti-Runx2 and anti-β-Tubulin; rabbit, AbCam, Cambridge, MA) for 1.5 hours at RT with shaking and IRDye-conjugated secondary antibody (Li-Cor Biotechnology, Lincoln, NE) for 1 hour at RT with shaking. Infrared fluorescence was detected and quantified using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (Li-Cor).

Acknowledgements

Funding support for this work was provided by the NIH (R01 HL093281 to K.S.M.), the Cardiovascular Training Program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (NIH, T32 HL 007936-06 to K.J.R.) and a University of Wisconsin-Madison Graduate Engineering Research Scholars (GERS) fellowship to K.J.R. The authors would like to thank Mr. Kyle Williamson and Mr. Max Salick for their technical support and assistance with the mechanical testing.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aikawa E, Whittaker P, Farber M, Mendelson K, Padera RF, Aikawa M, Schoen FJ. Human semilunar cardiac valve remodeling by activated cells from fetus to adult: implications for postnatal adaptation, pathology, and tissue engineering. Circulation. 2006;113:1344–1352. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.591768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison DD, Braun KR, Wight TN, Grande-Allen KJ. Differential effects of exogenous and endogenous hyaluronan on contraction and strength of collagen gels. Acta. Biomater. 2009;5:1019–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa I, Garcia S, Barbier-Chassefiere V, Caruelle JP, Martelly I, Papy-Garcia D. Improved and simple micro assay for sulfated glycosaminoglycans quantification in biological extracts and its use in skin and muscle tissue studies. Glycobiology. 2003;13:647–653. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwg082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton JA, Kern HB, Anseth KS. Substrate properties influence calcification in valvular interstitial cell culture. J. Heart Valve Dis. 2008;17:689–699. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao H, Spicer AP. Natural antisense mRNAs to hyaluronan synthase 2 inhibit hyaluronan biosynthesis and cell proliferation. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:27513–27522. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411544200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croce MA, Boraldi F, Quaglino D, Tiozzo R, Pasquali-Ronchetti I. Hyaluronan uptake by adult human skin fibroblasts in vitro. Eur. J. Histochem. 2003;47:63–73. doi: 10.4081/808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuff CA, Kothapalli D, Azonobi I, Chun S, Zhang Y, Belkin R, Yeh C, Secreto A, Assoian RK, Rader DJ, Puré E. The adhesion receptor CD44 promotes atherosclerosis by mediating inflammatory cell recruitment and vascular cell activation. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;108:1031–1040. doi: 10.1172/JCI12455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushing MC, Liao JT, Anseth KS. Activation of valvular interstitial cells is mediated by transforming growth factor-beta1 interactions with matrix molecules. Matrix Biol. 2005;24:428–437. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushing MC, Liao JT, Jaeggli MP, Anseth KS. Material-based regulation of the myofibroblast phenotype. Biomaterials. 2007;28:3378–3387. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goll DE, Bray RW, Hoekstra WG. Age-associated changes in muscle composition. The isolation and properties of a collagenous residue from bovine muscle a. J. Food Sci. 1963;28:503–509. [Google Scholar]

- Grande-Allen KJ, Griffin BP, Ratliff NB, Cosgrove DM, Vesely I. Glycosaminoglycan profiles of myxomatous mitral leaflets and chordae parallel the severity of mechanical alterations. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003a;42:271–277. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00626-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grande-Allen KJ, Mako WJ, Calabro A, Shi Y, Ratliff NB, Vesely I. Loss of chondroitin 6-sulfate and hyaluronan from failed porcine bioprosthetic valves. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2003b;A 65:251–259. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory CA, Gunn WG, Peister A, Prockop DJ. An Alizarin red-based assay of mineralization by adherent cells in culture: comparison with cetylpyridinium chloride extraction. Anal. Biochem. 2004;329:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X, Masters KS. Role of the MAPK/ERK pathway in valvular interstitial cell calcification. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2009;296:H1748–H1757. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00099.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta V, Barzilla JE, Mendez JS, Stephens EH, Lee EL, Collard CD, Laucirica R, Weigel PH, Grande-Allen KJ. Abundance and location of proteoglycans and hyaluronan within normal and myxomatous mitral valves. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2009;18:191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellstrom M, Johansson B, Engstrom-Laurent A. Hyaluronan and its receptor CD44 in the heart of newborn and adult rats. Anat. Rec. A. Discov. Mol. Cell. Evol. Biol. 2006;288:587–592. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton RB, Jr, Lincoln J, Deutsch GH, Osinska H, Manning PB, Benson DW, Yutzey KE. Extracellular matrix remodeling and organization in developing and diseased aortic valves. Circ. Res. 2006;98:1431–1438. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000224114.65109.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoerstrup SP, Kadner A, Melnitchouk S, Trojan A, Eid K, Tracy J, Sodian R, Visjager JF, Kolb SA, Grunenfelder J. Tissue engineering of functional trileaflet heart valves from human marrow stromal cells. Circulation. 2002;106:143–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim S, Ramamurthi A. Hyaluronic acid cues for functional endothelialization of vascular constructs. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2008;2:22–32. doi: 10.1002/term.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, Williams JD, Fraser D, Phillips AO. Hyaluronan attenuates transforming growth factor-beta1-mediated signaling in renal proximal tubular epithelial cells. Am. J. Pathol. 2004;164:1979–1988. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63758-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jian B, Narula N, Li QY, Mohler ER, 3rd, Levy RJ. Progression of aortic valve stenosis: TGF-beta 1 is present in calcified aortic valve cusps and promotes aortic valve interstitial cell calcification via apoptosis. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2003;75:457–465. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04312-6. discussion 465-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joddar B, Ramamurthi A. Fragment size- and dose-specific effects of hyaluronan on matrix synthesis by vascular smooth muscle cells. Biomaterials. 2006;27:2994–3004. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CM, Hanson MN, Helgeson SC. Porcine cardiac valvular subendothelial cells in culture: cell isolation and growth characteristics. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1987;19:1185–1193. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(87)80529-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaden JJ, Dempfle CE, Grobholz R, Tran HT, Kilic R, Sarikoc A, Brueckmann M, Vahl C, Hagl S, Haase KK, Borggrefe M. Interleukin-1 beta promotes matrix metalloproteinase expression and cell proliferation in calcific aortic valve stenosis. Atherosclerosis. 2003;170:205–211. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(03)00284-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloxin AM, Benton JA, Anseth KS. In situ elasticity modulation with dynamic substrates to direct cell phenotype. Biomaterials. 2010;31:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latif N, Sarathchandra P, Thomas PS, Antoniw J, Batten P, Chester AH, Taylor PM, Yacoub MH. Characterization of structural and signaling molecules by human valve interstitial cells and comparison to human mesenchymal stem cells. J Heart Valve Dis. 2007;16:56–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu AC, Joag VR, Gotlieb AI. The emerging role of valve interstitial cell phenotypes in regulating heart valve pathobiology. Am. J. Pathol. 2007;171:1407–1418. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Flegal K, Ford E, Furie K, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Hailpern S, Ho M, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lackland D, Lisabeth L, Marelli A, McDermott M, Meigs J, Mozaffarian D, Nichol G, O'Donnell C, Roger V, Rosamond W, Sacco R, Sorlie P, Stafford R, Steinberger J, Thom T, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Wong N, Wylie-Rosett J, Hong Y. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119:e21–e181. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locci P, Marinucci L, Lilli C, Martinese D, Becchetti E. Transforming growth factor beta 1-hyaluronic acid interaction. Cell Tissue Res. 1995;281:317–324. doi: 10.1007/BF00583400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters KS, Shah DN, Leinwand LA, Anseth KS. Crosslinked hyaluronan scaffolds as a biologically active carrier for valvular interstitial cells. Biomaterials. 2005;26:2517–2525. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler ER, 3rd, Adam LP, McClelland P, Graham L, Hathaway DR. Detection of osteopontin in calcified human aortic valves. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1997;17:547–552. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.3.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler ER, 3rd, Chawla MK, Chang AW, Vyavahare N, Levy RJ, Graham L, Gannon FH. Identification and characterization of calcifying valve cells from human and canine aortic valves. J. Heart. Valve. Dis. 1999;8:254–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler ER, III, Gannon F, Reynolds C, Zimmerman R, Keane MG, Kaplan FS. Bone formation and inflammation in cardiac valves. Circulation. 2001;103:1522–1528. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.11.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulholland DL, Gotlieb AI. Cell biology of valvular interstitial cells. Can. J. Cardiol. 1996;12:231–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabkin E, Aikawa M, Stone JR, Fukumoto Y, Libby P, Schoen FJ. Activated interstitial myofibroblasts express catabolic enzymes and mediate matrix remodeling in myxomatous heart valves. Circulation. 2001;104:2525–2532. doi: 10.1161/hc4601.099489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramamurthi A, Vesely I. Evaluation of the matrix-synthesis potential of crosslinked hyaluronan gels for tissue engineering of aortic heart valves. Biomaterials. 2005;26:999–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez KJ, Masters KS. Regulation of valvular interstitial cell calcification by components of the extracellular matrix. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2009;A 90:1043–1053. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah DN, Recktenwall-Work SM, Anseth KS. The effect of bioactive hydrogels on the secretion of extracellular matrix molecules by valvular interstitial cells. Biomaterials. 2008;29:2060–2072. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slevin M, Kumar S, Gaffney J. Angiogenic oligosaccharides of hyaluronan induce multiple signaling pathways affecting vascular endothelial cell mitogenic and wound healing responses. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:41046–41059. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109443200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slevin M, Krupinski J, Gaffney J, Matou S, West D, Delisser H, Savani RC, Kumar S. Hyaluronan-mediated angiogenesis in vascular disease: uncovering RHAMM and CD44 receptor signaling pathways. Matrix Biol. 2007;26:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2006.08.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivatsa SS, Harrity PJ, Maercklein PB, Kleppe L, Veinot J, Edwards WD, Johnson CM, Fitzpatrick LA. Increased cellular expression of matrix proteins that regulate mineralization is associated with calcification of native human and porcine xenograft bioprosthetic heart valves. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;99:996–1009. doi: 10.1172/JCI119265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens EH, Chu CK, Grande-Allen KJ. Valve proteoglycan content and glycosaminoglycan fine structure are unique to microstructure, mechanical load and age: Relevance to an age-specific tissue-engineered heart valve. Acta. Biomater. 2008;4:1148–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens EH, Timek TA, Daughters GT, Kuo JJ, Patton AM, Baggett LS, Ingels NB, Miller DC, Grande-Allen KJ. Significant changes in mitral valve leaflet matrix composition and turnover with tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2009;120:S112–S119. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.844159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turley EA, Noble PW, Bourguignon LY. Signaling properties of hyaluronan receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:4589–4592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100038200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesely I. The role of elastin in aortic valve mechanics. J. Biomech. 1998;31:115–123. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(97)00122-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyavahare N, Ogle M, Schoen FJ, Zand R, Gloeckner DC, Sacks M, Levy RJ. Mechanisms of bioprosthetic heart valve failure: fatigue causes collagen denaturation and glycosaminoglycan loss. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1999;46:44–50. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199907)46:1<44::aid-jbm5>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker GA, Masters KS, Shah DN, Anseth KS, Leinwand LA. Valvular myofibroblast activation by transforming growth factor-beta: implications for pathological extracellular matrix remodeling in heart valve disease. Circ. Res. 2004;95:253–260. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000136520.07995.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber J, Jenkins RH, Meran S, Phillips A, Steadman R. Modulation of TGFbeta1-dependent myofibroblast differentiation by hyaluronan. Am. J. Pathol. 2009;175:148–160. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woessner JF., Jr The determination of hydroxyproline in tissue and protein samples containing small proportions of this imino acid. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1961;93:440–447. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(61)90291-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip CY, Chen JH, Zhao R, Simmons CA. Calcification by valve interstitial cells is regulated by the stiffness of the extracellular matrix. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2009;29:936–942. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.182394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]