Abstract

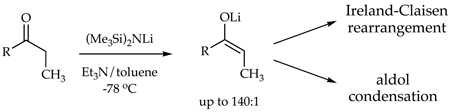

Lithium hexamethyldisilazide (LiHMDS) in triethylamine (Et3N)/toluene is shown to enolize acyclic ketones and esters rapidly and with high E/Z selectivity. Mechanistic studies reveal a dimer-based mechanism consistent with previous studies of LiHMDS/Et3N. E/Z equilibration occurs when <2.0 equiv of LiHMDS are used. Studies of the aldol condensation and Ireland-Claisen rearrangement of the resulting Et3N-solvated enolates show higher and often complementary diastereoselectivities when compared with analogous reactions in THF. The Et3N-solvated enolates also display a marked (20-fold) acceleration of the Ireland-Claisen rearrangement with evidence of autocatalysis. A possible importance of amine-solvated enolates is discussed.

Introduction

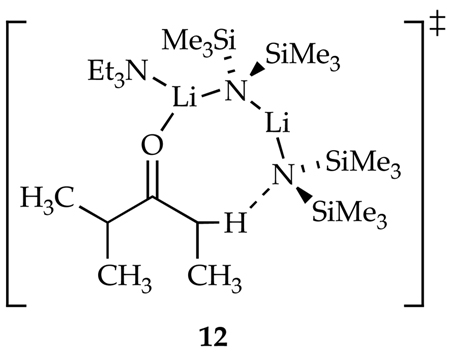

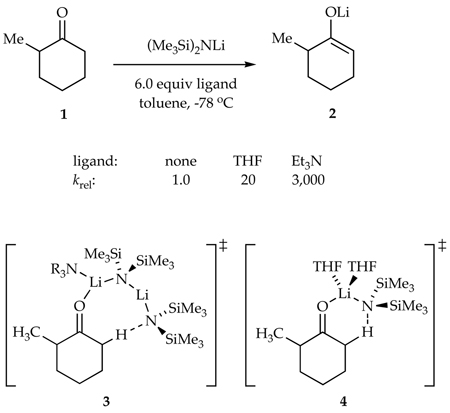

On the heels of investigations of the solvent-dependent structures of lithium hexamethyldisilazide (LiHMDS),1,2 we began examining structure-reactivity relationships in LiHMDS-mediated ketone enolizations (eq 1).3 We found that enolization of ketone 1 in Et3N/toluene3a is >100 times faster than the analogous enolization in neat THF.3b,c. This was surprising given that simple trialkylamines are particularly feeble ligands2,3a,b,4 that have rarely been used in organolithium chemistry.5,6 The high rates imparted by trialkylamines were traced to a dimer-based pathway exemplified by transition structure 3. The exceptional steric demands of the trialkylamines were shown to destabilize dimeric LiHMDS reactants more than they destabilize transition structure 3. By contrast, the LiHMDS/THF-mediated enolizations proceed via a more conventional disolvated monomer-based transition structure 4.3b.

|

(1) |

We describe herein LiHMDS/Et3N-mediated enolizations of acyclic ketones. The enolizations are fast, dimer-based, and, most important, highly E selective (eq 2). We also examine the reactivity of the Et3N-solvated lithium enolates toward aldol condensations and Ireland-Claisen rearrangements and find some distinct advantages when compared with THF-solvated enolates.7

|

(2) |

Results

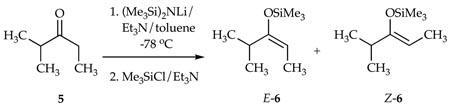

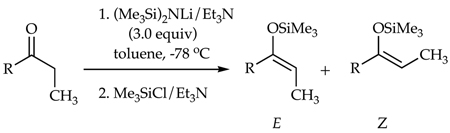

Stereochemistry of Enolization

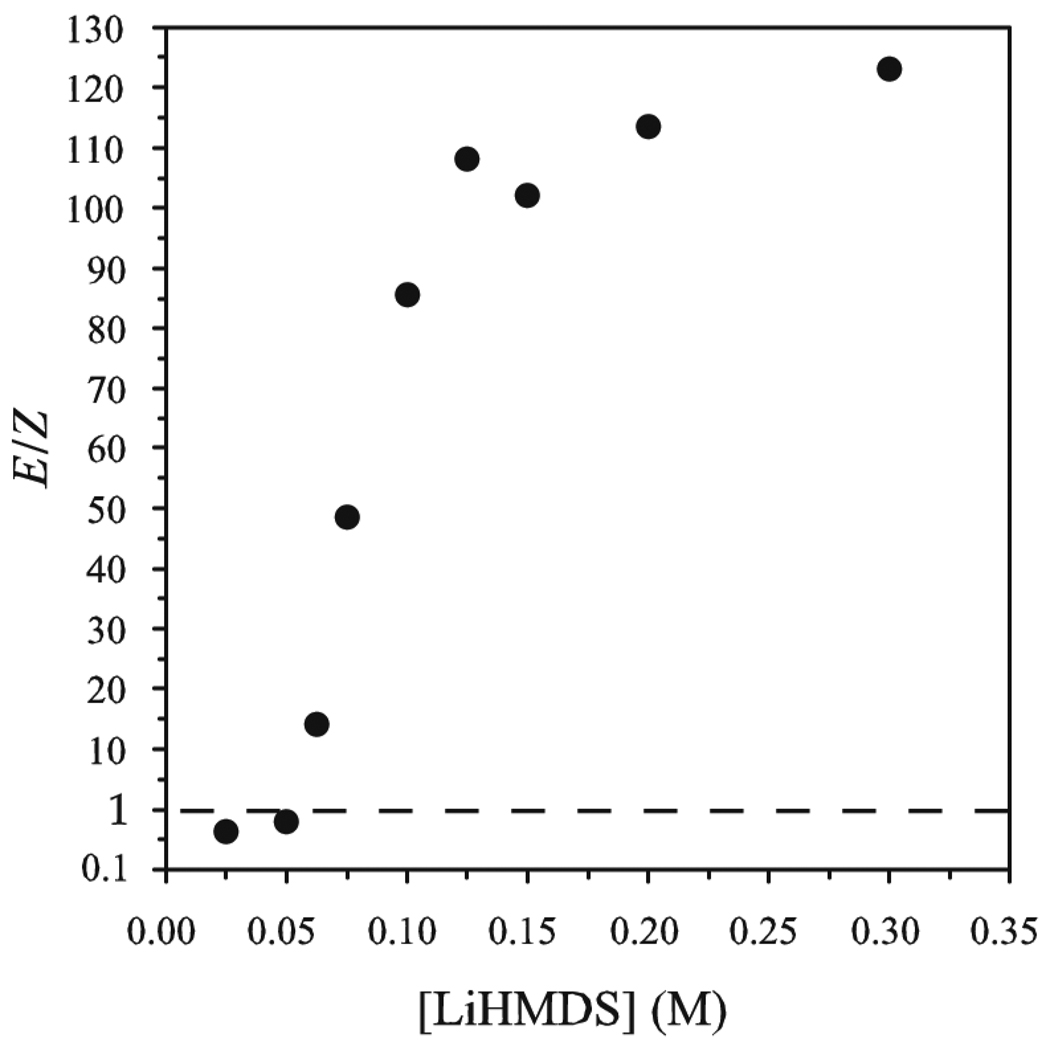

The E/Z selectivities for LiHMDS-mediated enolizations were monitored by quenching the resulting enolate solutions with Me3SiCl/Et3N8 and analyzing the products with gas chromatography (GC) using well-established protocols (eq 3).9 The proportion of LiHMDS to ketone proves to be the key determinant of stereochemistry (Figure 1). At low base loadings the enolization shows a modest Z selectivity akin to that observed for LiHMDS/THF mixtures.10,11,12 The E selectivity rises markedly with increasing quantities of LiHMDS, approaching 110:1 at ≥2.0 equiv of LiHMDS per ketone.

Figure 1.

E/Z selectivity (E-6:Z-6, eq 3) versus molarity (M) of LiHMDS in samples containing 0.10 M ketone 5 and 1.2 M excess Et3N in toluene at −78 °C.16

|

(3) |

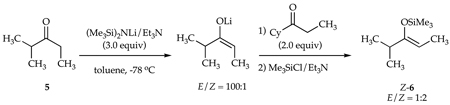

The dependencies of the E/Z selectivities on the equivalents of LiHMDS could be construed as evidence of intervening lithium enolate/LiHMDS mixed aggregates in a kinetically controlled enolization.9, 13,14,15 It is mathematically impossible, however, for a 100:1 selectivity at 50% conversion (2.0 equiv of base) to be reversed to a 1:2 selectivity at full conversion (1.0 equiv of base) without an intervening equilibration. Indeed, when a reaction mixture resulting from a highly E-selective enolization of ketone 5 is subsequently treated with cyclohexyl ethyl ketone as a surrogate to consume the remaining LiHMDS (eq 4), the E selectivity in the enolization of 5 is lost. Under no circumstance, however, is a regiochemical equilibration observed.

|

(4) |

A limited survey of hindered trialkylamines and dialkyl ethers in toluene as the cosolvent afforded the E/Z selectivities listed in Table 1. LiHMDS/Et3N affords the highest selectivities.11 The selectivity reversal caused by decreasing the THF concentrations was noted by Xie and Wielgosh.12

Table 1.

| solvent, S |

E-6:Z-6 |

|---|---|

| Et3N | 110:1 |

| Me2NEt | 90:1 |

| (i-Pr)2NEt | 40:1 |

| i-Bu3N | 60:1 |

| THF (0.5 M) | 13:1 |

| THF (10 M) | 1:13 |

| Me4THFb | 40:1 |

| TMEDA | 30:1 |

[5] = 0.050 M; [LiHMDS] = 0.15 M; [S] = 1.5 M in toluene; −78 °C.

Me4THF = 2,2,5,5-tetramethyltetrahydrofuran (1.5 M in toluene).

The generality of the E-selective enolization by LiHMDS/Et3N was established by surveying the enolizations summarized in Table 2. Results derived from LiHMDS/THF are included for comparison. Although the selectivities were not optimized for each case, we suspect there is only limited room for improvement.

Table 2.

| E/Z selectivity | ||

|---|---|---|

| R |

Et3N/tolueneb |

THFc |

| Et | 140:1 | 1:411a |

| i-pr (3) | 100:1 | 1:1411a |

| Cy | 80:1 | 1:3010 |

| Ph | 3.5:1 | 1:>10011a |

| CH3O | 22:1 | 1:1211b,k |

|

50:1 | 1:811c,d |

[ketone] = 0.05 M; [LiHMDS] = 0.15 M.

[Et3N] = 1.5 M in toluene; −78 °C.

Neat THF.

|

(5) |

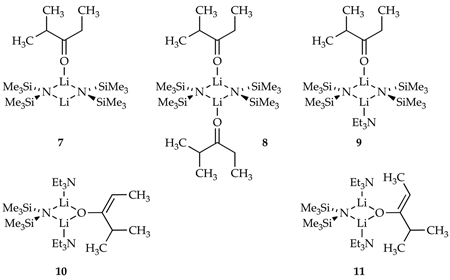

Aggregate Structures

Adding ketone 5 to LiHMDS in either toluene or Et3N/toluene mixtures at −78 °C and monitoring with in situ IR spectroscopy reveals that 5 (1714 cm−1) is quantitatively converted to LiHMDS-ketone complexes (1698 cm−1).17,18 (The less reactive 2,4,4-trideuterated ketone, 5-d3,19 was used to monitor structures and rates in some instances.) Dimers bearing one or two complexed ketones (7 and 8) are readily characterized with 6Li and 15N NMR spectoscopy1,20,21 using [6Li,15N]LiHMDS22 (Table 3). Putative LiHMDS-ketone complex 9 was too reactive to characterize, but is almost certainly isostructural to the closely related complex characterized previously.3b Enolization of 5 with 3.0 equiv of LiHMDS/Et3N at −78 °C affords mixed dimer 10 (Table 3). If the enolization is carried out under poorly selective conditions at 0 °C using 3.0 equiv of [6Li,15N]LiHMDS, both mixed dimer 10 and the corresponding Z-enolate-derived mixed dimer 11 are observed.15b

Table 3.

NMR spectroscopic dataa

| compd | δ 6Li (mult, JLiN) | δ 15N (mult, JLiN) |

|---|---|---|

| 7 | 1.00 (t, 4.0) | 41.4 (q,3.8) |

| 1.48 (t, 3.1) | ||

| 8 | 1.85 (t, 3.3) | 38.7 (q, 3.4) |

| 10 | 0.48 (d, 3.4) | 40.34 (q, 3.4) |

| 11 | 0.51 (d, 3.5) | 40.31 (m, --) |

Spectra were recorded in 0.10 M [6Li,15N]LiHMDS in toluene containing Et3N. Coupling constants were measured after resolution enhancement and reported in hertz. Multiplicities are denoted as follows: d = doublet, t = triplet, and q = quintet. The chemical shifts are reported relative to 0.30 M 6LiCl/MeOH at −90 °C (0.0 ppm) and neat Me2NEt at −90 °C (25.7 ppm).

Mechanism of Enolization

The structural similarities of ketones 1 and 5 certainly suggest a common mechanism. Indeed, rate studies using well-documented protocols3,21 confirm the mechanistic parallels as follows. Pseudo-first-order conditions were established by maintaining low concentrations of ketone 5 (0.004–0.01 M) and high, yet adjustable, concentrations of recrystallized22 LiHMDS (0.05–0.40 M) and Et3N (0.15–2.40 M), with toluene as the cosolvent. Monitoring the loss of LiHMDS-ketone complex 9 with in situ IR spectroscopy (1698 cm−1) shows clean first-order decays to ≥5 half-lives. The resulting pseudo-first-order rate constants (kobsd) are independent of ketone concentration (0.004 – 0.040 M). Re-establishing the IR baseline and monitoring a second aliquot of ketone reveals no significant change in the rate constant, showing that conversion-dependent autocatalysis or autoinhibition are unimportant under these conditions.23,24 Comparison of 5 and 5-d3 provided a large kinetic isotope effect (kH/kD > 10),25 confirming rate-limiting proton transfer.26,27

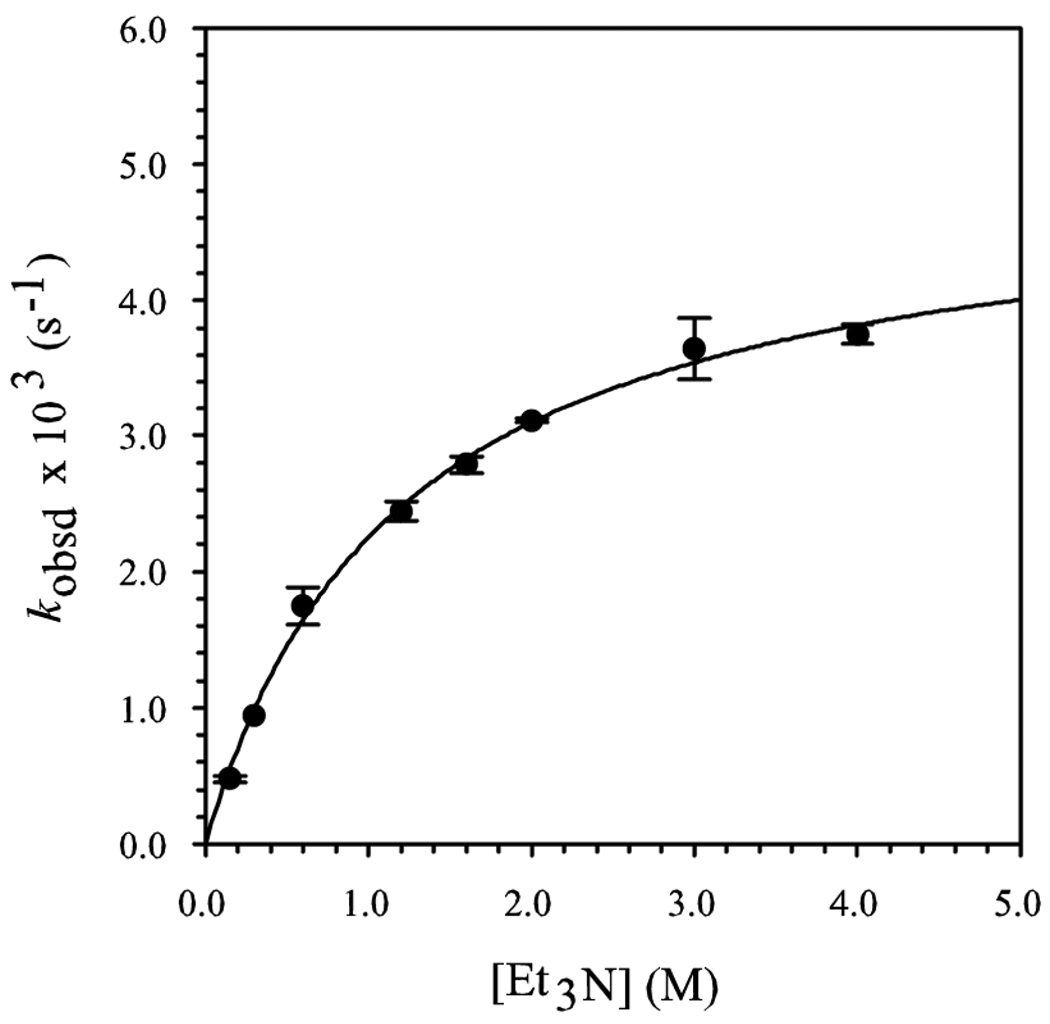

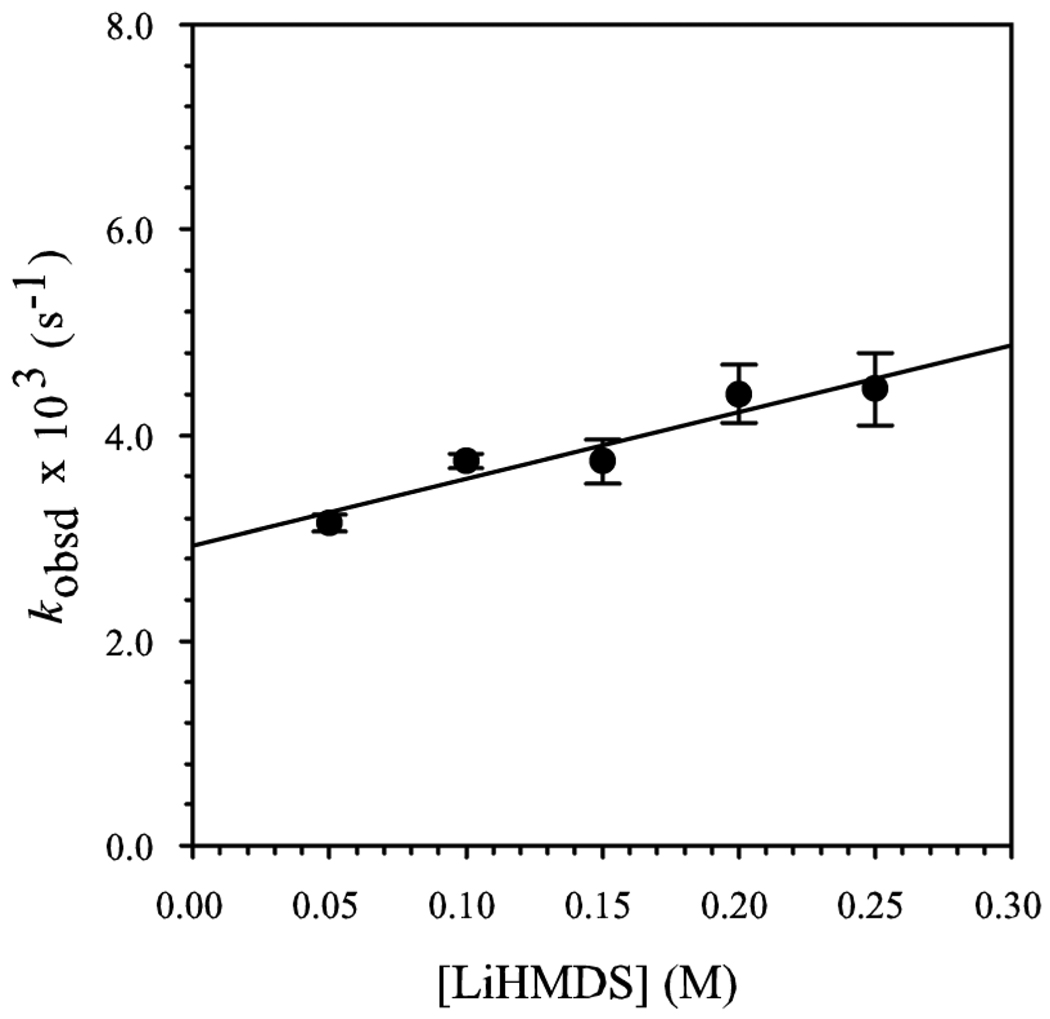

A plot of kobsd versus [Et3N] shows saturation kinetics (Figure 2).3b,24,28 At low Et3N concentrations, unsolvated complex 7 is the dominant form (see above), affording a first-order [Et3N] dependence. At high concentrations of Et3N, fully solvated complex 9 becomes the dominant form, and a zeroth-order Et3N dependence results. A plot of kobsd versus [LiHMDS] at elevated Et3N concentration reveals a zeroth-order dependence (Figure 3). (The slight upward drift results from residual saturation kinetics affording complex 9.)3a The idealized rate law (eq 6) is consistent with the generic mechanism described by eqs 7 and 8 and monosolvated dimer-based transition structure 12.29

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

Figure 2.

Plot of kobsd versus [Et3N] in toluene cosolvent for the enolization of 5-d3 (0.005 M) by LiHMDS (0.10 M) at −78 °C. The curve depicts an unweighted least-squares fit to kobsd = a[Et3N]/(1 + b[Et3N]), where a = 4.0 ± 0.1, b = 8.2 ± 0.6 × 101.

Figure 3.

Plot of kobsd versus [LiHMDS] in 4.0 M Et3N/toluene solution for the enolization of 5-d3 (0.005 M) by LiHMDS at −78 °C. The curve depicts an unweighted least-squares fit to kobsd = a[LiHMDS] + b, where a = 5 ± 1, b = 3.0 ± 0.1.

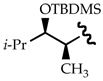

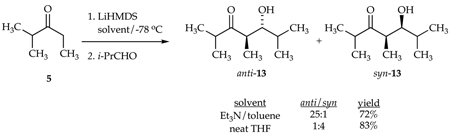

Aldol Condensation

We examined the reactivities and selectivities of enolates bearing poorly coordinating and sterically demanding Et3N ligands and compared them with those observed in neat THF. For example, eq 9 illustrates a sequential enolization with LiHMDS (3.0 equiv) in Et3N/toluene followed by an aldol condensation with isobutyraldehyde affording primarily anti-13 (anti/syn = 25:1).30 By contrast, the analogous reaction in neat THF shows decidedly inferior stereocontrol with opposite selectivity. Several additional aldol condensations are included as supporting information.

|

(9) |

By carrying out the enolizations in different solvents, we are comparing the chemistry of enolates that differ in both stereochemistry and coordinating ligand. To isolate the influence of solvent on only the aldol condensation, we enolized 5 with LiHMDS/Et3N and subsequently added THF prior to the addition of i-PrCHO; the anti/syn selectivity drops to 18:1. Thus, there is no apparent advantage offered by the THF-solvated enolate. Nonetheless, we believe that such strategies can be important (vide infra).

Ireland-Claisen Rearrangement

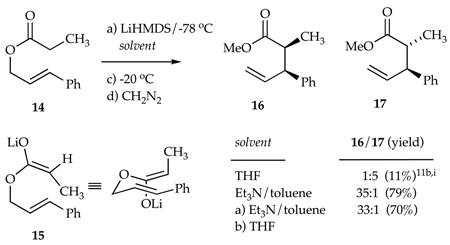

We examined a lithium enolate variant of the Ireland-Claisen rearrangement7,11b,31 to compare selectivities and reactivities of THF- and Et3N-solvated enolates. Enolization of 14 using LiHMDS (3.0 equiv) and Et3N (10 equiv per lithium) in toluene at −78 °C affords an estimated 20:1 preference for enolate 15 (see Table 2, R = OMe). Claisen rearrangement of 15 at −20 °C affords a 35:1 ratio of 1631 and 1731 in 79% isolated yield. Addition of 10 equiv of THF (per lithium) subsequent to enolization in Et3N/toluene affords a comparable 33:1 selectivity in 70% yield (albeit much more slowly; vide infra). Curiously, the standard protocol--enolization and rearrangement in neat THF--proceeds in 11% yield. The low yields using LiHMDS/THF could stem from either a poor enolization or a poor rearrangement from the Z isomer as noted by Ireland in a similar silyl Claisen.11i

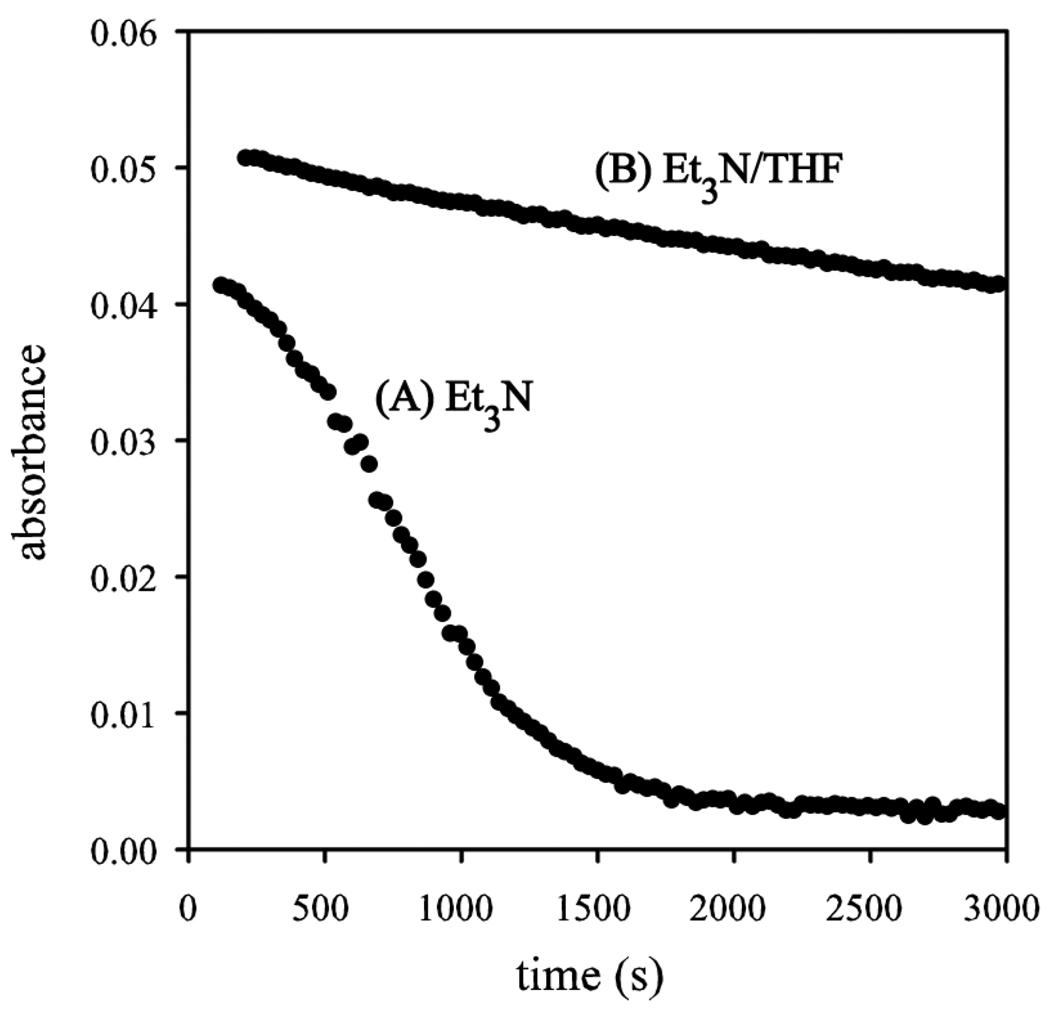

Qualitative rate studies of the rearrangement are quite interesting. In situ IR spectroscopy revealed the loss of the Et3N-solvated ester enolate 15 (1675 and 1659 cm−1) and formation of carboxylate absorbances (1610, 1600, 1582, and 1424 cm−1).32 A sigmoidal behavior (Figure 4, curve A) is indicative of autocatalysis24,33 occurring as the enolate is replaced with carboxylates, presumably within aggregates. By contrast, addition of 10 equiv of THF (per lithium) subsequent to enolization affords a THF-solvated enolate, as evidenced by the replacement of absorbances at 1675 and 1659 cm−1 with an absorbance at 1657 cm−1. Of special importance, rearrangement in Et3N/toluene (Figure 4, curve B) proceeds approximately 20 times faster than with added THF. The Et3N solvated enolate is substantially more reactive.

Figure 4.

IR absorbance of enolate 15 versus time in (A) 1.5 M Et3N/toluene, and (B) 1.5 M Et3N/1.5 M THF/toluene.

Discussion

We previously showed that LiHMDS/Et3N-mediated enolizations are very fast compared to LiHMDS/THF and traced the accelerations to a dimer-based mechanism.3b,29 We hasten to add that the high rates are only observed using ≥2.0 equiv of LiHMDS. (Equimolar LiHMDS and ketone afford an inert bis-ketone solvated LiHMDS dimer.) Of course, such accelerations are notable, but the procedure may also be cost effective. LiHMDS is now used routinely on large scales for complex drug synthesis.35,36 Using Et3N/hydrocarbon mixtures instead of THF could offer considerable savings.10,37

E-Selective Enolizations

Acting on a hunch, we found LiHMDS/Et3N-mediated enolizations of acyclic ketones are very fast and afford high E/Z selectivities (Tables 1 and 2). Excess (≥2.0 equiv) LiHMDS is required to maintain high rates and selectivities. Enolizations of ketone 5 with only 1.0 equiv of LiHMDS/Et3N suffer from E/Z equilibration. Overall, the procedure is more selective and more convenient than that using LiTMP/LiBr mixtures, which has afforded lithium enolates with the highest E-selectivity (up to 50:1) reported to date.9

Mechanism of Enolization

NMR spectroscopic studies of the enolization of ketone 5 using 3.0 equiv of LiHMDS revealed lithium enolate-LiHMDS mixed dimer 10. The loss in stereoselectivity when <2.0 equiv LiHMDS/Et3N was used was traced to a facile equilibration and consequent formation of mixed dimers 10 and 11. There is no affiliated regiochemical equilibration.

Rate studies of the enolization under pseudo-first-order conditions (a large excess of LiHMDS) confirmed that a dimer-based enolization--transition structure 12--is the source of the high selectivities. Previous semiempirical computational studies of enolizations by amine-solvated lithium amides failed to predict the observed high selectivities.38

Aldol Condensation

The facile enolizations in Et3N/toluene allowed us to examine the reactivity of Et3N-solvated enolates and to compare them with their THF-solvated counterparts. We first examined the aldol condensation--the most prevalent application of E-selective enolizations--to ascertain whether the high enolization selectivities could be translated into high syn/anti selectivities. The aldol condensations are generally anti selective using the LiHMDS/Et3N-based protocol (eq 9 and supporting information). We examined whether the selectivity might improve if THF was added before the addition of the aldehyde. This sequence is tantamount to doing the enolization in Et3N and the aldol condensation in THF. The selectivities did not improve.

Claisen Rearrangement

We investigated a lithium enolate variant of the Ireland-Claisen rearrangement shown in eq 10.7 The low yields using LiHMDS/THF were previously observed by Ireland on a closely related case and were attributed to the formation of an unreactive stereoisomer. We concur with this notion. The improved selectivity toward enolate 15 expected for LDA/THF could, in principle, solve the problem, but we obtained complex mixtures that probably derived from allylic metalation of or 1,2-addition to the cinnamyl ether moiety.39 By contrast, LiHMDS/Et3N-mediated enolization affords 15 rapidly and selectively. Subsequent rearrangement proceeded in good yield and exceptional selectivity.

A distinct benefit of the Ireland-Claisen rearrangement is that it is slow enough to allow us to readily monitor reaction rates. We found that Et3N-solvated enolates rearrange approximately 20 times faster than the analogous THF solvates, and there is evidence of autocatalysis.33 We are likely to examine Ireland-Claisen rearrangements in more detail later.

On the Role of Solvent Mixtures

There are very few ligands--probably far fewer than most organic chemists realize--that can displace THF from lithium.1,20 When an enolate is generated in THF, the subsequent reaction is necessarily THF dependent in most instances. By contrast, highly hindered trialkylamines are substitutionally labile, potentially allowing many ligands to coordinate and influence subsequent reactions. Although substituting THF for Et3N in a few instances described herein did not offer obvious benefits, the principle is an important one. Organolithium intermediates generated in poorly coordinating solvents are especially well suited for subsequent ligand substitutions. If Et3N and the electrophile are incompatible (alkyl halides, for example), highly hindered dialkylethers may suffice.3d

Conclusion

LiHMDS/Et3N offers a particularly convenient, cost-effective protocol for generating lithium enolates with the highest E selectivity reported to date. The Et3N-solvated enolates are also provocative species. As expected, the high E selectivities can be translated into relatively highly stereoselective aldol condensations and Ireland-Claisen rearrangements. Moreover, the potential importance of amine-solvated lithium enolates is underscored by a marked (20-fold) acceleration of the Ireland-Claisen rearrangement when compared with the rates observed using THF-solvated variant. One might ask why, if Et3N elicits such favorable reactivities, have simple (monodentate) trialkylamines played such a minor role in organolithium chemistry?5,6 The answer may be simple. Et3N is a poorly coordinating ligand that cannot compete with ethereal solvents for coordination to lithium: Et3N requires hydrocarbons as cosolvents to be effective. We suggest that trialkylamine/hydrocarbon mixtures are worthy of more careful consideration in other applications within organolithium chemistry.

Experimental Section

Reagents and Solvents

Coordinating ligands and toluene were distilled by vacuum transfer from blue or purple solutions containing sodium benzophenone ketyl. The toluene still contained 1% tetraglyme to dissolve the ketyl. 6Li metal (95.5% enriched) was obtained from Oak Ridge National Laboratory (Oak Ridge, TN). LiHMDS, [6Li]LiHMDS, and [6Li,15N]LiHMDS were prepared and purified as described previously.22 Ketone 5-d3 was prepared as described previously.19 Air- and moisture-sensitive materials were manipulated under argon or nitrogen using standard glove box, vacuum line, and syringe techniques.

NMR Spectroscopic Analyses

Samples were prepared, and the 6Li and 15N NMR spectra were recorded as described elsewhere.2

IR Spectroscopic Analyses

Spectra were recorded with an in situ IR spectrometer fitted with a 30-bounce, silicon-tipped probe optimized for sensitivity. The spectra were acquired in 16 scans (30-second intervals) at a gain of 1 and a resolution of 4 or 8. The probe was inserted through a nylon adapter and O-ring seal into an oven-dried, cylindrical flask fitted with a magnetic stir bar and T-joint. The T-joint was capped with a septum for injections and an argon line. After evacuation under full vacuum and flushing with argon, the flask was charged with the reagents via syringe.

Representative enolization

A 5-mL serum vial was charged with a solution of LiHMDS (50 mg, 0.30 mmol) in Et3N (420 µL, 3.0 mmol) and toluene (1.53 mL) and cooled to −78 °C. Ketone 5 (12 µL, 0.10 mmol) in toluene (38 µL) was added with stirring. After 20 min, the reaction was quenched with 180 µL of a 4:1 solution of Me3SiCl/Et3N (centrifuged free of solid Et3N-HCl) in toluene (3.0 mL). After warming to RT, dilution with pentane, and quenching with cold aqueous NaHCO3, the solution was subjected to a standard aqueous workup. The crude enol silyl ethers E-6 and Z-6 were analyzed by GC as described previously.9

Representative Aldol Condensation

The enolate solution prepared as described above was quenched with isobutyraldehyde (27 µL, 0.30 mmol). After an additional 10 min at −78 °C and quenching with aqueous NH4Cl, a standard aqueous workup afforded a crude mixture of adducts anti-13 and syn-13 in 25:1 ratio as shown by GC. Flash chromatography afforded pure anti-13 in 72% yield as shown by comparison with previously reported spectroscopic data.30

Ireland-Claisen Rearrangement

A solution of enolate in Et3N (1.5 M)/toluene was prepared at −78 °C as described above. The sample was slowly warmed to RT to allow the rearrangement to proceed. After 10 min at RT, the reaction mixture was poured into 10 mL of 5% aqueous NaOH and washed with ether. The aqueous layer was cooled to 0 °C and acidified with concentrated HCl, and the carboxylic acid was extracted with ether. The carboxylic acid was converted to its methyl ester by adding distilled CH2N242 at 0 °C until a yellow color persisted. The resulting methyl esters were analyzed using GC to show a 35:1 mixture of 1631 and 17.31 Flash chromatography afforded a 79% combined yield.

Kinetics

Rate constants were determined using a standard protocol exemplified as follows: The IR cell described above was charged with a solution of LiHMDS (167 mg, 1.00 mmol) in Et3N (2.09 mL, 1.5 M) and toluene (7.74 mL) and cooled to −78 °C. After recording a background spectrum, ketone 5 (50 µL, 0.050 mmol, 0.005 M final concentration) was added neat with stirring. IR spectra were recorded over 5 half-lives. To account for mixing and temperature equilibration, spectra recorded in the first 1.0 min were discarded. The rate constant was determined using an unweighted, non-linear least squares fit to the function f(x)=aebx.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health for direct support of this work. We also thank Merck Research Laboratories, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, R. W. Johnson, Boehringer-Ingelheim, and Schering-Plough for indirect support.

Footnotes

Supporting Information: NMR spectra and rate data (xx pages). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References and Footnotes

- 1.Lucht BL, Collum DB. Acc. Chem. Res. 1999;32:1035. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lucht BL, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:2217. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Zhao P, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:4008. doi: 10.1021/ja021284l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhao P, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:14411. doi: 10.1021/ja030168v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhao P, Condo A, Keresztes I, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:3113. doi: 10.1021/ja030582v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Zhao P, Lucht BL, Kenkre SL, Collum DB. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:242. doi: 10.1021/jo030221y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Bernstein MP, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:8008. [Google Scholar]; (b) Brown TL, Gerteis RL, Rafus DA, Ladd JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964;86:2135. [Google Scholar]; (c) Lewis HL, Brown TL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970;92:4664. [Google Scholar]; (d) Quirk RP, Kester DE. J. Organomet. Chem. 1977;127:111. [Google Scholar]; (e) Young RN, Quirk RP, Fetters LJ. Adv. Polym. Sci. 1984;56:1. [Google Scholar]; (f) Eppley RL, Dixon JA. J. Organomet. Chem. 1968;11:174. [Google Scholar]; (g) Quirk RP, Kester D, Delaney RD. J. Organomet. Chem. 1973;59:45. [Google Scholar]; (h) Quirk RP, McFay D. J. Polym. Sci., Polym. Chem. Ed. 1981;19:1445. [Google Scholar]; (i) Kaufmann E, Gose J, Schleyer PvR. Organometallics. 1989;8:2577. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukuzaki T, Kobayashi S, Hibi T, Ikuma Y, Ishihara J, Kanoh N, Murai A. Org. Lett. 2002;4:2877. doi: 10.1021/ol026260y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chalk AJ, Hay AS. J. Polym. Sci, A. 1969;7:691. Carreira EM, Du Bois J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:8106. Bartlett PD, Tauber SJ, Weber WD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969;91:6362. Fisher JW, Trinkle KL. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:2505. Screttas CG, Eastham JF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965;87:3276. Goralski P, Legoff D, Chabanel M. J. Organomet. Chem. 1993;456:1. Hallden-Aberton M, Engelman C, Fraenkel G. J. Org. Chem. 1981;46:538. Sanderson RD, Roediger AHA, Summers GJ. Polym. Int. 1994;35:263. Welch FJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1960;82:6000. Oliver CE, Young RN, Brocklehurst B. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A. 1993;70:17. Streitwieser A, Jr, Cang CJ, Hollyhead WB, Murdoch JR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972;94:5288. Sanderson RD, Costa G, Summers GJ, Summers CA. Polymer. 1999;40:5429. Yu YS, Jerome R, Fayt R, Teyssie P. Macromolecules. 1994;27:5957. Zgonnik VN, Sergutin VM, Kalninsh KK, Lyubimova GV, Nikolaev NI. Bull. Acad. Sci. USSR. 1977;26:709. Antkowiak TA, Oberster AE, Halasa AF, Tate DP. J. Polym. Sci., A. 1972;10:1319. Giese HH, Habereder T, Knizek J, Nöth H, Warchold M. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2001:1195. Doriat C, Koeppe R, Baum E, Stoesser G, Koehnlein H, Schnoeckel H. Inorg. Chem. 2000;39:1534. doi: 10.1021/ic9903432. Chabanel M, Lucon M, Paoli D. J. Phys. Chem. 1981;85:1058. Bernstein MP, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:789. Luitjes H, de Kanter FJJ, Schakel M, Schmitz RF, Klumpp GW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:4179. Wiedemann SH, Ramírez A, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:15893. doi: 10.1021/ja0304087. (u) Also, see reference 4.

- 7.(a) Ireland RE, Mueller RH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972;94:5897. doi: 10.1021/ja00765a079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Castro AMM. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:2939. doi: 10.1021/cr020703u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Pereira S, Srebnik M. Aldrichim. Acta. 1993;26:17. [Google Scholar]; (d) Hiersemann M, Nubbemeyer U. The Claisen Rearrangement: Methods and Applications. Wiley: Weinheim; 2007. [Google Scholar]; (e) Gilbert JC, Yin J, Fakhreddine FH, Karpinski ML. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:51. [Google Scholar]; (f) Chai Y, Hong S-p, Lindsay HA, McFarland C, McIntosh MC. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:2905. [Google Scholar]; (g) Tsunoda T, Sakai M, Sasaki O, Sako Y, Hondo Y, Ito S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:1651. [Google Scholar]; (h) Trunoda T, Sasaki O, Ito S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:727. [Google Scholar]; (h) Tsunoda T, Nishii T, Hoshizuka M, Yamasaki C, Suzuki T, Ito S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:7667. [Google Scholar]; (i) Suh YG, Kin S-A, Jung J-K, Shin D-Y, Min K-H, Koo B-A, Kim H-S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1999;38:3545. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(19991203)38:23<3545::aid-anie3545>3.3.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Linström UM, Somfai P. Chem.-Eur. J. 2001;7:94. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20010105)7:1<94::aid-chem94>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Linström UM, Somfai P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:8385. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stork G, Hudrlik PF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968;90:4462. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall PL, Gilchrist JH, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:9571. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masamune S, Imperiali B, Garvey DS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:5526. [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Heathcock CH, Buse CT, Kleschick WA, Pirrung MC, Sohn JE, Lampe J. J. Org. Chem. 1980;45:1066. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ireland RE, Mueller RH, Willard AK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976;98:2868. [Google Scholar]; (c) Evans DA, Yang MG, Dart MJ, Duffy JL, Kim AS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:9598. [Google Scholar]; (d) McCarthy PA, Kageyama M. J. Org. Chem. 1987;52:4681. [Google Scholar]; (e) Davis FA, Yang B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:8398. doi: 10.1021/ja051452k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Okabayashi T, Iida A, Takai K, Nawate Y, Misaki T, Tanabe Y. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:8142. doi: 10.1021/jo701456t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Woltermann CJ, Hall RW, Rathman T. PharmaChem. 2003;2:4. [Google Scholar]; (h) Fataftah ZA, Kopka IE, Rathke MW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:3959. [Google Scholar]; (i) Ireland RE, Wipf P, Armstrong JD., III J. Org. Chem. 1991;56:650. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie L, Wielgosh M. Book of Abstracts, 219th ACS National Meeting; March 26–30, 2000; San Francisco, CA. Washington, D. C: Publisher: American Chemical Society; 2000. ORGN-196. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galiano-Roth AS, Kim Y-J, Gilchrist JH, Harrison AT, Fuller DJ, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:5053. [Google Scholar]

- 14.For leading references and discussions of mixed aggregation effects, see: Seebach D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1988;27:1624. Tchoubar B, Loupy A. Salt Effects in Organic and Organometallic Chemistry. New York: VCH; 1992. Chapters 4, 5, and 7. Briggs TF, Winemiller MD, Xiang B, Collum DB. J. Org. Chem. 2001;66:6291. doi: 10.1021/jo010305b. Caubère P. Chem. Rev. 1993;93:2317. Gossage RA, Jastrzebski JTBH, van Koten G. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:1448. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462103.

- 15.(a) For rate studies of the alkylation of LiHMDS/lithium enolate mixed aggregates in THF, see: Kim Y-J, Streitwieser A. Org. Lett. 2002;4:573. doi: 10.1021/ol017175d. (b) For a lithium amide mixed aggregate containing the enolate of 3-pentanone, see: Sun CZ, Williard PG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:7829.

- 16.The concentration of LiHMDS, although expressed in units of molarity, refers to the concentration of the monomer unit (normality). Concentrations of the Et3N refer to the concentrations of the free (uncomplexed) amine rather than to the total unless stated otherwise.

- 17.For leading references and recent examples of detectable organolithium-substrate pre-complexation, see: Klumpp GW. Recl. Trav. Chim. Pays-Bas. 1986;105:1. Andersen DR, Faibish NC, Beak P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:7553. (c) For more recent examples of observable RLi-substrate precomplexation see: Pippel DJ, Weisenberger GA, Faibish NC, Beak P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:4919. doi: 10.1021/ja001955k. Bertini-Gross KM, Beak P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:315. doi: 10.1021/ja002662u.

- 18.For a general discussion of ketone-lithium complexation and related ketone- Lewis acid complexation, see: Shambayati S, Schreiber LS. In: Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Trost BM, Fleming I, editors. Vol. 1. New York: Pergamon; 1991. p. 283.

- 19.Peet NP. J. Label. Compound. 1973;9:721. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collum DB. Acc. Chem. Res. 1993;26:227. [Google Scholar]

- 21.For a review of the kinetics of lithium diisopropylamide-mediated reactions, see: Collum DB, McNeil AJ, Ramirez A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;49:3002. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603038.

- 22.Romesberg FE, Bernstein MP, Gilchrist JH, Harrison AT, Fuller DJ, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:3475. [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Seebach D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1988;27:1624. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sun X, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:2459. [Google Scholar]; (c) McGarrity JF, Ogle CA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;107:1810. [Google Scholar]; (d) Thompson A, Corley EG, Huntington MF, Grabowski EJJ, Remenar JF, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:2028. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Depue JS, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:5524. [Google Scholar]

- 25.The undeuterated ketone reacted so quickly at −78 °C that only a lower limit on the measured isotope effect is warranted.

- 26.Isotope effects for LiHMDS-mediated ketone enolizations have been measured previously. Held G, Xie LF. Microchem. J. 1997;55:261. Xie LF, Saunders WH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:3123.

- 27.The regioselectivity indicated in eq 1 was shown to be >20:1 by trapping with Me3SiCl/Et3N mixtures and comparing the crude product with authentic material by GC.26

- 28.Espenson JH. Chemical Kinetics and Reaction Mechanisms. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1995. pp. 86–90. [Google Scholar]; Dunford HB. J. Chem. Educ. 1984;61:129. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Open dimers were first proposed for the isomerization of oxiranes to allylic alcohols by mixed metal bases: Mordini A, Rayana EB, Margot C, Schlosser M. Tetrahedron. 1990;46:2401. For a bibliography of lithium amide open dimers, see Ramirez A, Sun X, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:10326. doi: 10.1021/ja062147h.

- 30.(a) Heathcock CH, Pirrung MC, Sohn JE. J. Org. Chem. 1979;44:4294. [Google Scholar]; (b) Evans DA, Nelson JV, Taber TR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981;103:3099. [Google Scholar]; (c) Van Horn DE, Masamune S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1979:2229. [Google Scholar]

- 31.For stereoselective Ireland-Claisen rearrangements using boron enolates, see: Corey EJ, Lee D-H. J. Am Chem. Soc. 1991;113:4026.

- 32.Silverstein RM, Webster FX, editors. Spectrometric Identification of Organic Compounds. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1998. p. 97. [Google Scholar]

- 33.(a) Nudelman NS, Velurtas S, Grela MA. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2003;16:669. [Google Scholar]; (b) Alberts AH, Wynberg H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:7265. [Google Scholar]; (c) Alberts AH, Wynberg H. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1990:453. [Google Scholar]; (d) Xie L, Saunders WH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:3123. [Google Scholar]

- 34.(a) Besson C, Finney EE, Finke RG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:8179. doi: 10.1021/ja0504439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Besson C, Finney EE, Finke RG. Chem. Mater. 2005;17:4925. doi: 10.1021/ja0504439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Espenson JH. Chemical Kinetics and Reaction Mechanisms. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1995. [Google Scholar]; (d) Huang KT, Keszler A, Patel N, Patel RP, Gladwin MT, Kim-Shapiro DB, Hogg N. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:31126. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501496200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Huang Z, Shiva S, Kim-Shapiro DB, Patel RP, Ringwood LA, Irby CE, Huang KT, Ho C, Hogg N, Schechter AN, Gladwin MT. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:2099. doi: 10.1172/JCI24650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Tanj S, Ohno A, Sato I, Soai K. Org. Lett. 2001;3:287. doi: 10.1021/ol006921w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.(a) Dugger RW, Ragan JA, Ripin DHB. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2005;9:2943. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wu G, Huang M. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:2596. doi: 10.1021/cr040694k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Farina V, Reeves JT, Senanayake CH, Song JJ. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:2734. doi: 10.1021/cr040700c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.For selected examples in which LiHMDS is used on large scale, see: Kauffman GS, Harris GD, Dorow RL, Stone BRP, Parsons RL, Jr, Pesti JA, Magnus NA, Fortunak JM, Confalone PN, Nugent WA. Org. Lett. 2000;2:3119. doi: 10.1021/ol006321x. Boys ML, Cain-Janicki KJ, Doubleday WW, Farid PN, Kar M, Nugent ST, Behling JR, Pilipauskas DR. Org. Process Res. Dev. 1997;1:233. Ragan JA, Murry JA, Castaldi MJ, Conrad AK, Jones BP, Li B, Makowski TW, McDermott R, Sitter BJ, White TD, Young GR. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2001;5:498. Rico JG. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:6599. DeMattei JA, Leanna MR, Li W, Nichols PJ, Rasmussen MW, Morton HE. J. Org. Chem. 2001;66:3330. doi: 10.1021/jo0057203.

- 37.The advantages of hydrocarbons containing low concentrations of coordinating ligands are discussed: Rutherford JL, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:199. doi: 10.1021/ja003104i.

- 38.Romesberg FE, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:2166. [Google Scholar]

- 39.(a) Mukaiyama T, Hayashi H, Miwa T, Narasaka K. Chem. Lett. 1982:1637. [Google Scholar]; (b) Conor SB, Simpkins NS. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:8192. [Google Scholar]

- 40.LiHMDS solvated by hindered ethers were shown to enolize ketone 1 via a dimer-based mechanism analogous to 3.3d

- 41.LiHMDS/Et3N mixtures were used inadvertently by Murai and coworkers when they carried out LiHMDS/toluene-mediated enolizations with a Et3N/Me2SiCl2 in situ trap.6

- 42.Black TH. Aldrichim. Acta. 1983;16(1):3. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.