Abstract

Bacterial infection may increase risk for thrombosis and atherosclerosis. Human platelets express toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), the receptor for gram-negative bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Experiments were designed to evaluate direct, acute effects of TLR4 activation on aggregation, secretion, and generation of pro-thrombogenic microparticles in vitro on platelets derived from healthy women at risk for development of cardiovascular disease because of their hormonal status. Platelet-rich plasma from recently menopausal women was incubated with ultrapure Escherichia coli LPS in the absence or presence of antibodies that neutralize the human TLR4. Incubating platelets with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 5 minutes decreased aggregation and dense granule adenosine triphosphate secretion induced by thrombin receptor agonist peptide (TRAP) but not by adenosine diphosphate or collagen. The antibody to TLR4 blocked this effect of LPS. TLR4 activation increased phosphorylation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and decreased production of prothrombotic phosphatidylserine and P-selectin–positive microparticles in response to TRAP. Therefore, acute, direct activation of TLR4 reduces platelet reactivity to TRAP stimulation in vitro. Increased thrombotic and cardiovascular risk with bacterial infection most likely reflects the sum of TLR4 activation on other blood and vascular cells to release proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines, which indirectly affect platelet reactivity.

Keywords: infection, innate immunity, thrombin receptor agonist peptide, ATP secretion, thrombotic risk

INTRODUCTION

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), the major outer membrane component of gram-negative bacteria, stimulates inflammatory processes through toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), a trans-membrane glycoprotein present on leukocytes, lymphocytes, vascular endothelium, and human platelets.1–3 Therefore, endotoxin may have direct effects on platelet functions and indirect effects through release of inflammatory cytokines from other activated blood elements. In humans, with no symptoms of infection, circulating levels of LPS range from 6 to 209 pg/mL. Although acute infection increases risk for an adverse thrombotic event,4–7 endotoxin at concentrations > 50 pg/mL induces inflammatory responses in human monocytes, macrophages, and vascular cells and is an independent risk factor for atherosclerosis.8,9

When activated, platelets, as well as other cells, release sealed phospholipid-rich membrane vesicles called micro-particles, which depending on their surface proteins and receptors can be thrombogenic10–13 Whether TLR4 activation mediates release of microparticles from platelets, which could potentially link infection to thrombotic risk, is not know. Furthermore, in nucleated cells, TLR4 activation is signaled through phosphorylation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), but it is unclear if a similar pathway would be activated in anucleate platelets.14 Experiments were designed to evaluate acute, direct effects and mechanisms of LPS through TLR4 signaling in platelets.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

The following materials were used: ultrapurified LPS (Escherichia coli 0111:B4 strain-TLR4 ligand; catalog #tlrl-pelps) from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA); monoclonal antibody to human TLR4 from IMGENEX (San Diego, CA); TLR4 blocking mouse anti-human TLR4 antibody (clone HTA125) from eBioscience (San Diego, CA); and rabbit anti-human phospho-P38 MAP kinase and p38 MAP kinase antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies (Beverly, MA). The LPS and HTA125 were azide-free. All other reagents and solvents used in this study were of analytic/reagent grade. All blood chemistries were measured by the Mayo Clinic Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology (Rochester, MN).

Subjects

Participants were recently postmenopausal women (n = 26) being screened for eligibility into the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS, NCT000154180)15 at Mayo Clinic according to an institutional research board–approved protocol (IRB 2241-04). Women were between 42 and 58 years of age and within 3 years of their last menses. Women were not using lipid-lowering medications or aspirin. Their serum levels of 17β estradiol were <40 pg/mL, with follicle-stimulating hormone >35 mIU/mL; none were current smokers (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Women from Whom Platelets Were Collected*

| Age (yrs) | Menopausal Age (mo) | BMI (kg/m2) | LDL Cholesterol (mg/dL) | HDL Cholesterol (mg/dL) | TG (mg/dL) | hs-CRP (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 52.5 ± 0.3 | 17.4 ± 1.8 | 26.2 ± 0.6 | 149.8 ± 8.0 | 61.1 ± 2.6 | 103.2 ± 12.9 | 1.8 (0.3–8.4)† |

Data are shown as mean ± SEM; n = 24–26.

Mean (range of values).

BMI, body mass index; HDL, high-density lipoproteins; LDL, low-density lipoproteins; TG, triglycerides.

Preparation of Platelet-rich Plasma

Blood from the antecubital vein was collected through a 19-gauge needle into tubes containing either citrate or hirudin plus tick anticoagulant peptide. Anticoagulated blood was centrifuged at 200g at room temperature for 15 minutes to obtain platelet-rich plasma (PRP). The purity of PRP was validated by Coulter counter (T660; Mayo Clinic Hematology Lab), yielding <0.1% of leukocyte or red blood cell contamination. The platelet count in each sample of PRP was measured so that the same number of platelets could be studied in each experiment and/or data adjusted for secretion/platelet.

Platelet Aggregation

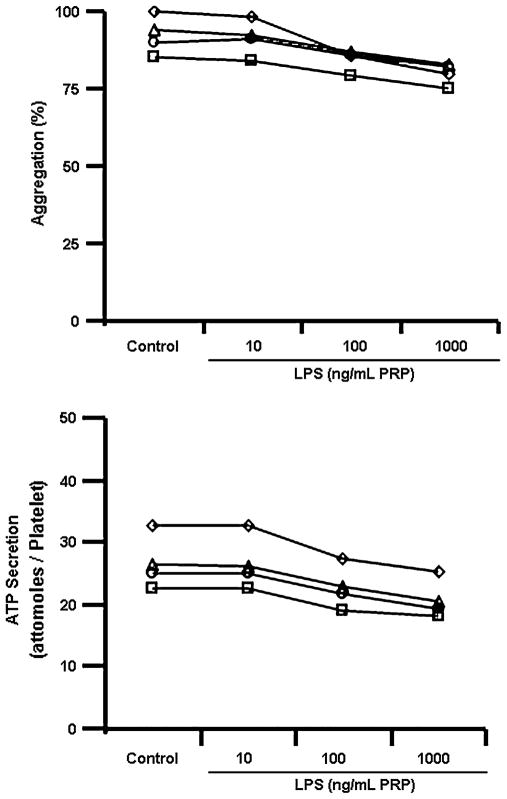

In preliminary experiments, PRP was incubated with varying concentrations of LPS (10–1000 ng/mL) from 1 to 60 minutes to identify the lowest concentration (threshold) of LPS, which reliably affected platelet activity in the shortest period (Fig. 1). Based on these experiments, in all other experiments, PRP was incubated with a 100 ng/mL of LPS for 5 minutes. This dose of LPS was also observed as threshold concentration to induce release of interleukin-1β from isolated human platelets after 60 minutes of incubation.16 For all experiments, PRP from a single participant was aliquoted into separate tubes, each containing the same number of platelets. Saline (control), LPS, or LPS plus the antibody for TLR4 was added to each tube in equal volumes. The monoclonal TLR4 antibody (20 μg/mL) was added 30 minutes before addition of the LPS. Aggregation was induced with thrombin receptor agonist peptide (TRAP, 10 μM/mL), adenosine diphosphate (ADP, 10 μM/mL), and equine tendon collagen (2 μg/mL) in separate experiments. Aggregation was determined by a turbidimetric method using the whole blood aggregometer in optical mode (model 560-VS; Chrono-Log; Haverton, PA) as described previously.17,18

FIGURE 1.

Preliminary experiments to determine the threshold dose for LPS, which affected platelet aggregation (upper panel) and secretion (lower panel) after a 5-minute incubation. Each line represents responses of platelets from a single individual. Based on these data, LPS at a dose of 100 ng/mL with an incubation time of 5 minutes was used in all other experiments.

Platelet Dense Body Adenosine Triphosphate Secretion

Dense granule secretion of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) was measured by bioluminescence from ultradilute PRP (1:1000) after stimulation with TRAP (10 μM) as described previously.17,18 Maximal platelet ATP secretion is expressed as attomoles per platelet.

Isolation and Identification of Blood Microparticles

After platelet aggregation induced by TRAP, the sample was centrifuged at 3000g for 15 minutes. The pellet (platelet aggregates) was used for Western blotting (see below). The supernatant was removed and centrifuged again at 3000g for 15 minutes. Microparticles were isolated from this supernatant (platelet-free plasma) by centrifugation at 20,000g for 30 minutes and identified by flow cytometry (FACSCanto; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) as previously described.19

Western Blotting

The aggregated PRP (above) was washed twice with acid–citrate–dextrose buffer and stored at −70°C until analysis. Western blotting to determine expression of TLR4, total p38 MAPK, and dual phosphorylated (threonine180/tyrosine180) p38 MAPK was performed as described previously.20,21 Bands were analyzed using UN-SCAN-IT gel digitizing system.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Data were compared using 1-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett or Tukey multicomparison test or by Student t test for paired observations. For all tests, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

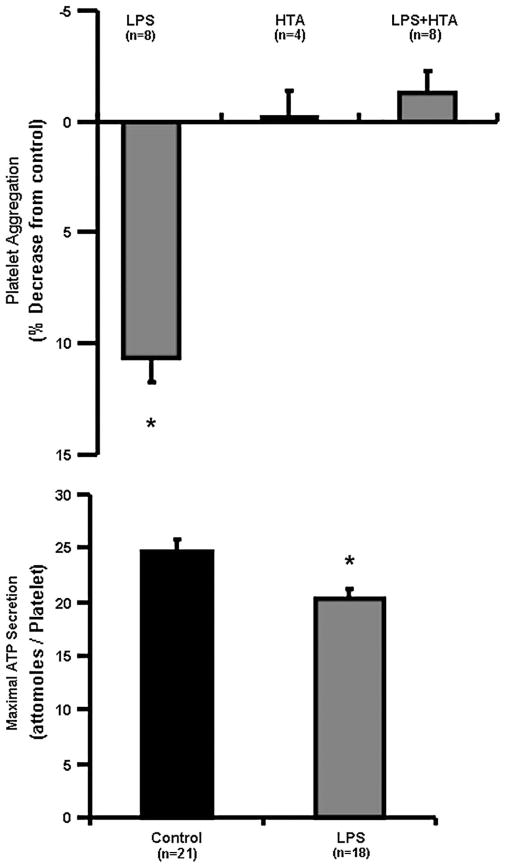

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of the study population were within the normative range by age and sex (Table 1). Of the 24 women in whom high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) was measured, 13 had values ≤1 mg/L, 8 had values 1≤3 mg/L, and 3 had values >3 mg/L. Platelet count averaged 256,000 ± 55,000/μL. Incubation of platelets for 5 minutes with LPS (100 ng/mL) significantly reduced platelet aggregation induced by TRAP (10 μM/mL), an effect blocked by the antibody to TLR4 (Fig. 2). LPS did not alter aggregation induced by either adenosine diphosphate (10 μM/mL) or collagen (2 μM/mL; data not shown). Dense body ATP secretion induced by TRAP also was significantly reduced by LPS (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

TLR4-mediated effects of LPS (100 ng/mL) on aggregation (top panel) and ATP secretion (bottom panel) of platelets from newly menopausal women. PRP was adjusted to contain equal numbers of platelets (256,000 ± 55,000/μL) for incubation with either equal volumes of saline (control) or LPS (100 ng/mL in saline) for 5 minutes before stimulation with TRAP (10 μM) in the absence and presence of the TLR4 antibody (HTA 125; 20 μg/mL). Data are shown as means ± SEM of the percent decrease in platelet aggregation to TRAP in saline alone; n represents the number of individual samples used for each test. Asterisks denote statistical significance from control, P < 0.05.

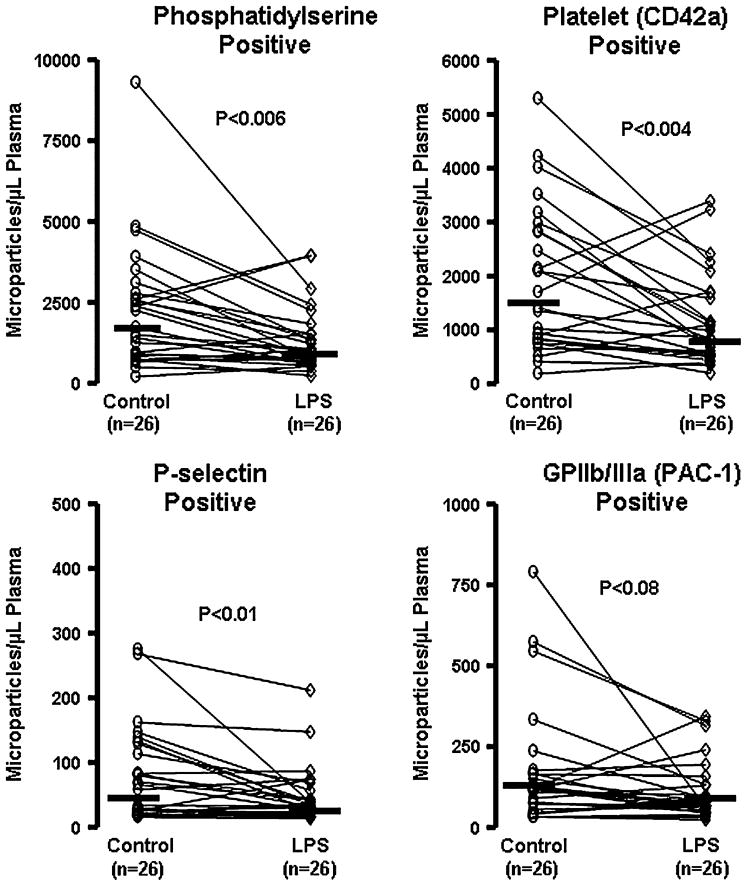

Under control conditions, generation of microparticles from platelets after TRAP stimulation showed wide variability among individuals (Fig. 3). Numbers of microparticles generated in response to TRAP tended to increase with increasing levels of hs-CRP; mean numbers of microparticles positive for phosphytidylserine were 1839, 2361, and 4727 microparticles/μL in women with hs-CRP levels ≤1, 1 to ≤3 and >3 mg/L, respectively. Given that only 3 women had hs-CRP levels >3 mg/L, there was insufficient statistical power for further analysis of this association. After the 5-minute incubation of platelets with LPS, there were significantly fewer phosphatidylserine-positive and platelet (CD42a)-positive microparticles (Fig. 3, upper panels). Other smaller (minor) populations of microparticles that were P-selective positive or GPIIb/IIIa positive likewise declined after LPS treatments (Fig. 3, lower panels). These effects of LPS on production of microparticles also were blocked by the TLR4 antibody (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Numbers of microparticles isolated from PRP exposed to saline control or LPS (100 ng/mL) for 5 minutes after stimulation of platelet aggregation with TRAP (10 μM). Data are shown as responses of paired samples from individual women (n). Bars represent median response of each group under each condition. P values denote significance between control and LPS.

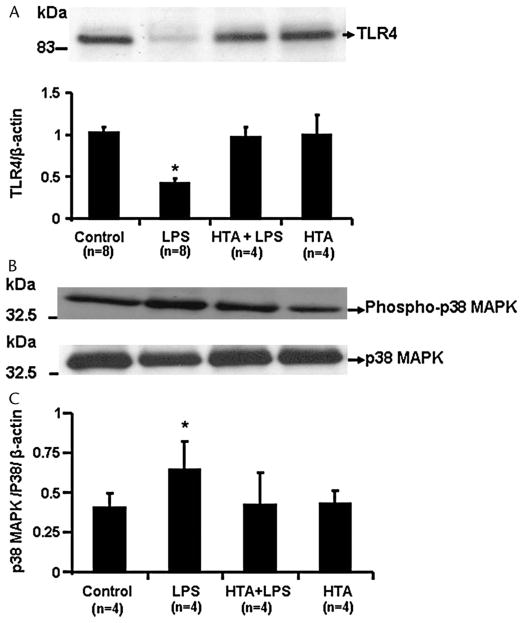

Expression of TLR4 on platelets was confirmed by Western blot analysis. Expression was reduced in lysate from aggregated platelets, which had been incubated with LPS (100 ng/mL), a response not observed in the presence of the antibody (Fig. 4). The phosphorylated form of p38 MAPK increased significantly in lysate from platelets incubated with LPS and was abrogated in the presence of the TLR4 antibody. Expression of total p38 MAPK (nonphosphorylated) was not affected by any of these interventions (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

Sample Western blots and cumulative densitometry of TLR4 expression (panel A), phospho-p38 MAPK (panel B), and p38 MAPK (panel C) in lysate from platelets, which had been incubated in the absence (control, saline) and presence of LPS (100 ng/mL), the TLR4 antibody HTA 125 (20 μg/mL) alone, or in combination with LPS. Cumulative data are presented as mean ± SEM; n represents the number of individuals from whom platelets were collected. Asterisk denotes statistical significance from control, P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Results of this study demonstrate that 5-minute incubation with LPS at a concentration selective to TLR4 signaling directly inhibited platelet aggregation, dense granule ATP secretion and release of reactive microparticles induced by TRAP but not by ADP or collagen. Although the inhibition of aggregation was modest (about 10%), the reduction in microparticle production was consistent with an inhibition of aggregation and may represent a more sensitive marker of the direct response of platelets to LPS. How this relates to increased thrombotic risk with bacterial infection is unknown. However, with longer incubation times, other second messenger systems are activated, which prime platelets to become hyper-responsive to other agonists.16 Therefore, this study provides insight into the temporal relationship of LPS–TLR4 binding and platelet functions. Furthermore, in vivo LPS would affect platelets themselves and also activate release of cytokines and microparticles from other blood elements, which could indirectly modulate platelet activity.22–24 With sepsis, circulating concentrations of LPS would be high enough to activate receptors other than and in addition to TLR4.25 Thus, the concentration of LPS, the duration of exposure, and the agonist used to stimulate platelets are critical to demonstrate acute modulation of platelet functions by LPS. These observations explain in part discrepancies in the literature of a null effect, proinflammatory, or inhibitory effect of LPS on platelet functions.23,26–30

In this study, platelets were obtained from comparably aged women of defined hormonal status. It remains to be determined how platelet responsiveness to LPS would be influenced by hormonal status and/or sex.31 These women were screened to eliminate confounding variables related to cardiovascular risk. Nonetheless, there appeared to be a relationship of hs-CRP, an inflammatory cytokine related to increased cardiovascular risk,32–35 and the platelet response to LPS. Three women had hs-CRP levels > 3 mg/L, which if sustained is a risk factor for atherosclerosis. However, because there was only a single measurement of hs-CRP in each woman, it is not known if this level would be sustained or if it represents an acute, occult infection.36,37 Although these data were not sufficiently powered to derive a significant correlation with hs-CRP, they are provocative enough to be hypothesis generating and support the concept that a defined inflammatory status of the platelet donor could impact specific mechanisms of platelet activation.38 Thrombin-generating capacity of platelets is related to numbers of phosphatidylserine-positive platelet microparticles.19 Numbers and characteristics of platelet-derived microparticles could define a prothrombotic condition.19,39,40

TLR4 signaling through stress-activated p38 MAPK observed in these anucleate human platelets parallels observations of TLR4 signaling in nucleated cells and platelets from horses.14,41 Modulation of platelet reactivity to some but not all agonists (ie, TRAP compared with ADP or collagen) after TLR4 activation may reflect convergence of receptor signaling pathways. For example, protein kinase Cδ activation of the p38 MAPK signaling cascade was essential for collagen-induced but not thrombin-induced platelet aggregation and activity.42

In conclusion, acute in vitro activation of the TLR4-dependent pathway by LPS directly and selectively decreases aggregation, dense granular ATP secretion, and generation of procoagulant or thrombogenic microparticles from platelets of recently menopausal women. Because TLR4 activation inhibited rather than augmented platelet aggregation in vitro suggests that acute in vivo LPS may affect platelet activation and thrombotic risk indirectly through activation of other cells. These concepts require validation in other populations, such as age-matched men, younger adults, and individuals with defined symptomatic infections. It will be possible to examine whether these LPS–TLR4–mediated mechanisms are affected by menopausal hormone treatments and how these changes relate to progression of atherosclerosis in women randomized to treatment as the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study trial progresses to planned termination in 2012.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH HL78638 and HL90639, Kronos Longevity Research Institute, American Heart Association (AHA30503Z), the Mayo Foundation Institute, and Japanese Menopause Society.

Footnotes

Dr. Hashimoto’s is now at Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Tokyo Women’s Medical University, Shinjyuku-ku, Tokyo, Japan.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Aslam R, Speck ER, Kim M, et al. Platelet toll-like receptor expression modulates lipopolysaccharide-induced thrombocytopenia and tumor necrosis factor-a production in vivo. Blood. 2006;107:637–641. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shiraki R, Inoue N, Kawasaki S, et al. Expression of Toll-like receptors on human platelets. Thromb Res. 2004;113:379–385. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2004.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cognasse F, Hamzeh H, Chavarin P, et al. Evidence of toll-like receptor molecules on human platelets. Immunol Cell Biol. 2005;83:196–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2005.01314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frishman WH, Ismail A. Role of infection in atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease: a new therapeutic target? Cardiol Rev. 2002;10:199–210. doi: 10.1097/00045415-200207000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyers DG. Myocardial infarction, stroke, and sudden cardiac death may be prevented by influenza vaccination. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2003;5:146–149. doi: 10.1007/s11883-003-0087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mattila KJ, Valtonen VV, Nieminen M, et al. Dental infection and the risk of new coronary events: prospective study of patients with documented coronary artery disease. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:588–592. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.3.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heit JA, Melton LJI, Lohse CM, et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients vs community residents. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:1102–1110. doi: 10.4065/76.11.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stoll LL, Denning GM, Weintraub NL. Potential role of endotoxin as a proinflammatory mediator of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:2227–2236. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000147534.69062.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rice JB, Stoll LL, Li WG, et al. Low-level endotoxin induces potent inflammatory activation of human blood vessels: inhibition by statins. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1576–1582. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000081741.38087.F9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cocucci E, Racchetti G, Meldolesi J. Shedding microvesicles: artefacts no more. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morel O, Toti F, Hugel B, et al. Cellular microparticles: a disseminated storage pool of bioactive vascular effectors. Curr Opin Hematol. 2004;11:156–164. doi: 10.1097/01.moh.0000131441.10020.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Distler JH, Huber LC, Gay S, et al. Microparticles as mediators of cellular cross-talk in inflammatory disease. Autoimmunity. 2006;39:683–690. doi: 10.1080/08916930601061538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boulanger CM, Amabile N, Tedgui A. Circulating microparticles: a potential prognostic marker for atherosclerotic vascular disease. Hypertension. 2006;48:180–186. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000231507.00962.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maung AA, Fujimi S, Miller ML, et al. Enhanced TLR4 reactivity following injury is mediated by increased p38 activation. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:565–573. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1204698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harman SM, Brinton EA, Cedars M, et al. KEEPS: the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study. Climacteric. 2005;8:3–12. doi: 10.1080/13697130500042417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shashkin PN, Brown GT, Ghosh A, et al. Lipopolysaccharide is a direct agonist for platelet RNA splicing. J Immunol. 2008;181:3495–3502. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jayachandran M, Okano H, Chatrath R, et al. Sex-specific changes in platelet aggregation and secretion with sexual maturity in pigs. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:1445–1452. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01074.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jayachandran M, Mukherjee R, Steinkamp T, et al. Differential effects of 17b-estradiol, conjugated equine estrogen and raloxifene on mRNA expression, aggregation and secretion in platelets. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H2355–H2362. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01108.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jayachandran M, Litwiller RD, Owen WG, et al. Characterization of blood borne microparticles as markers of premature coronary calcification in recently menopausal women. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:931–938. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00193.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klein-Hitpass L, Ryffel GU, Heitlinger E, et al. A 13 bp palindrome is a functional estrogen responsive element and interacts specifically with estrogen receptor. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:647–663. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.2.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jayachandran M, Miller VM. Ovariectomy upregulates expression of estrogen receptors, NOS, and HSPs in porcine platelets. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H220–H226. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00950.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montrucchio G, Bosco O, Del Sorbo L, et al. Mechanisms of the priming effect of low doses of lipopolysaccharides on leukocyte-dependent platelet aggregation in whole blood. Thromb Haemost. 2003;90:872–881. doi: 10.1160/TH03-02-0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ward JR, Bingle L, Judge HM, et al. Agonists of toll-like receptor (TLR)2 and TLR4 are unable to modulate platelet activation by adenosine diphosphate and platelet activating factor. Thromb Haemost. 2005;94:831–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cognasse F, Hamzeh-Cognasse H, Lafarge S, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 ligand can differentially modulate the release of cytokines by human platelets. Br J Haematol. 2008;141:84–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.06999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jayachandran M, Brunn GJ, Karnicki K, et al. In vivo effects of lipopolysaccharide and TLR4 on platelet production and activity: implications for thrombotic risk. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102:429–433. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01576.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matera C, Falzarano C, Berrino L, et al. Effects of tetanus toxin, Salmonella typhimurium porin, and bacterial lipopolysaccharide on platelet aggregation. J Med. 1992;23:327–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saba HI, Saba SR, Morelli G, et al. Endotoxin-mediated inhibition of human platelet aggregation. Thromb Res. 1984;34:19–33. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(84)90103-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saluk-Juszczak J, Wachowicz B, Bald E, et al. Effects of lipopolysaccharides from gram-negative bacteria on the level of thiols in blood platelets. Curr Microbiol. 2005;51:153–155. doi: 10.1007/s00284-005-4461-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baba K. Effects of E. coli LPS on human platelet aggregation. Masui. 1994;43:339–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheu JR, Hung WC, Kan YC, et al. Mechanisms involved in the antiplatelet activity of Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide in human platelets. Br J Haematol. 1998;103:29–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jayachandran M, Miller VM. Influence of hormones and sex on platelet functions. In: Bittar EE, editor. Advances in Molecular and Cell Biology. Vol. 34. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier B.V; 2004. pp. 307–319. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Albert MA, Glynn RJ, Buring JE, et al. C-reactive protein levels among women of various ethnic groups living in the United States (from the Women’s Health Study) Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:1238–1242. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.01.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pradhan AD, Manson JE, Rossouw JE, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers, hormone replacement therapy, and incident coronary heart disease. Prospective analysis from the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. JAMA. 2002;288:980–987. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.8.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ridker PM, Buring JE, Cook NR, et al. C-reactive protein, the metabolic syndrome, and risk of incident cardiovascular events. An 8-year follow-up of 14 719 initially healthy American women. Circulation. 2003;107:391–397. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000055014.62083.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ridker P, Cannon CP, Morrow D, et al. C-reactive protein levels and outcomes after statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:20–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Macy EM, Hayes TE, Tracy RP. Variability in the measurement of C-reactive protein in healthy subjects: implications for reference intervals and epidemiological applications. Clin Chem. 1997;43:52–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ockene IS, Matthews CE, Rifai N, et al. Variability and classification accuracy of serial high-sensitivity C-reactive protein measurements in healthy adults. Clin Chem. 2001;47:444–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller VM, Jayachandran M, Hashimoto K, et al. Estrogen, inflammation, and platelet phenotype. Gend Med. 2008;5:S91–S102. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jayachandran M, Litwiller RD, Owen WG, et al. Circulating micro-particles and endogenous estrogen in newly menopausal women. Climacteric. 2009;12:1–8. doi: 10.1080/13697130802488607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Merten M, Thiagarajan P. P-selectin in arterial thrombosis. Z Kardiol. 2004;93:855–863. doi: 10.1007/s00392-004-0146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brooks AC, Menzies-Gow NJ, Wheeler-Jones C, et al. Endotoxin-induced activation of equine platelets: evidence for direct activation of p38 MAPK pathways and vasoactive mediator production. Inflamm Res. 2007;56:154–161. doi: 10.1007/s00011-006-6151-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yacoub D, Theoret JF, Villeneuve L, et al. Essential role of protein kinase C delta in platelet signaling, alpha IIb beta 3 activation, and thromboxane A2 release. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:30024–30035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604504200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]