Abstract

Cardiac remodeling after acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is characterised by molecular and cellular mechanisms involving both left (LV) and right ventricular (RV) walls. Cardiomyoycte apoptosis in the peri-infarct and remote LV myocardium plays a central role in cardiac remodeling. Whether apoptosis also occurs in the right ventricle of patients with ischemic heart disease has not been investigated. Aim of the current study was to investigate the presence of cardiomyocyte apoptosis in the right ventricle in patients with AMI. We assessed the number of apoptotic cardiomyocytes by multiple samplings in the LV and RV walls of 12 patients selected at autopsy who died 4 to 42 days after AMI. Five patients without cardiac disease were also selected at autopsy as controls. Apoptotic rates were calculated from the number of cardiomyocytes showing double positive staining for in situ end-labeling of DNA fragmentation – TUNEL – and for activated caspase-3. Potentially false positive results (DNA synthesis and RNA splicing) were excluded from the cell counts. The apoptotic rate in the RV in patients with AMI was significantly higher than in control hearts (0.8% [0.3–1.0] vs 0.01% [0.01–0.03], P<0.001). RV apoptosis was significantly correlated with parameters of global adverse remodeling such as cardiac diameter-to-LV free wall thickness (R=+0.57, P=0.050). RV apoptosis was significantly higher in 5 cases (42%) with infarct involving the ventricular septum and an adjacent a small area of the RV walls (1.0% [0.8–2.2] vs 0.5% [0.2–1.0], P=0.048; P<0.001 vs controls). The association between apoptotic rate in RV and cardiac remodeling was apparent even after exclusion of cases with RV AMI involvement (R=+0.82, P=0.023 for diameter-to-LV wall thickness ratio; and R=−0.91, P=0.002 for RV free wall thickness). In conclusion, patients with cardiac remodeling after AMI have a significant increase in RV apoptosis even when ischemic involvement of the RV wall is not apparent.

Keywords: apoptosis, heart failure, right ventricle, myocardial infarction, remodeling

Introduction

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is associated with early and late compensatory mechanisms which can be seen as attempts to optimize ventricular filling and cardiac output of both the left and right ventricles. In animal experimental models of AMI, right ventricular (RV) remodeling is associated with left ventricular (LV) remodeling even if the RV is spared from the initial ischemic damage.1–2 Hirose et al.3 have shown that RV dilatation and remodeling variably occur in subjects with transmural LV AMI, and it has been shown that the presence of signs and/or symptoms of RV failure further identifies a subgroup of patients with an extremely unfavorable prognosis and survival which is frequently <2 years.4–5

Several molecular and cellular mechanisms, occurring both at the site of AMI and at remote unaffected sites, lead to LV dilatation and post-AMI dysfunction.6–7 Recently, myocardiocyte loss due to apoptosis in early and subacute phases of AMI has been consistently shown in human observational studies and in animal models.8–14 These findings are of importance because increased myocardial apoptotic rates are associated with severe and progressive heart failure.8–14 It remains to be determined, however, whether increased apoptosis is also present in the RV. We assessed the extent of myocardial apoptosis in postmortem RV tissue in 12 patients who died within 2 months of AMI.

METHODS

Twelve patients with recent AMI primarily involving the LV wall (occurring 4–42 days prior to death), no clinical, laboratory or pathology evidence of reinfarction, and absence of conditions likely to affect RV remodeling (such as RV AMI, severe lung disease, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary valvulopathy and intracardiac shunts) were selected at post-mortem examination.

Macroscopic examination was performed to determine the infarct size which was graded as a percentage of the LV circumference. In patients with transmural (>75%) septal infarct it was assessed whether the infarct area extended to the insertion of the anterior and/or posterior RV free walls. Transverse and longitudinal cardiac diameters were measured at the atrioventicular section. Left and right ventricle free wall thickness was measured in an unaffected segment. The transverse diameter-to-wall thickness ratio was calculated for the left and right ventricles. A cardiac diameter-to-LV free wall thickness ratio >9 was used to assess cardiac dilatation.11–12 RV dilatation was defined as an enlargement of the RV characterized by a tricuspidal ring circumference greater than 120 mm.11 The infarct-related artery was assessed at pathology and patency/degree of stenosis was assessed for the infarct-related artery and the major coronary branches. Tissue specimens were obtained from areas of the myocardium from the LV (usually posterior wall) and the RV (usually anterior wall) that were remote from the infarct site and visually unaffected. Specimens were processed as previously described.10–12 Briefly, specimens were fixed in 10% paraformaldehyde, in situ end-labeling of DNA fragmentation (TUNEL) was performed using the Apoptag kit (Oncor, Gaithersburg, MD), according to the supplier’s instructions. For immunohistochemistry, the sections already treated for the TUNEL assay were heated and then incubated with antibodies against muscle actin (mouse monoclonal anti-human actin HHF35 from DAKO-Carpintera, CA, US; dilution 1:50) and activated caspase-3 (using anti-cleaved caspase-3 [Asp 175] antibody – Cell Signaling Technology [dilution 1:50]) and visualized by the streptavidin-biotin system, using either 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazide or diaminobenzidine as the final chromogen. Myocardiocytes were defined as apoptotic if co-localization of markers of DNA fragmentation (TUNEL) and activated caspase-3 was evident, according to the fact that high immunohistochemical expression of caspase-3 is present in myocardiocytes undergoing apoptosis and it co-localizes with TUNEL positive cardiomyocytes. The apoptotic rate was expressed as the ratio of number of myocardiocytes co-expressing TUNEL and activated caspase-3 positivity on nucleated cells per field (250X), calculated from 100 fields. Muscle actin-negative cells as well as myocardiocytes co-expressing TUNEL-positivity and specific staining for markers of DNA synthesis (PCNA) (using mouse monoclonal anti-human PCNA PC10 antibody from DAKO, CA, USA, dilution 1:100) and/or markers of transcription activity (RNA splicing factor SC-35) (using mouse monoclonal anti SC-35 from Sigma, Milan, Italy; dilution 1:200) were not included in the cell count, as they were considered potential false positive results.9–11 Suitable negative and positive controls for TUNEL and caspase-3 were performed, as defined elsewhere.10–12 Briefly, controls for TUNEL were performed as indicated by the supplier (using a normal female rodent mammary gland 3–5 days after weaning of rat pups for positive control and sham stainings leaving out the active enzyme but including proteinase K digestion to control for non specific incorporation of nucleotides or for non specific binding of enzyme-conjugate). A “stringent approach” (leaving proteinase K digestion out of the reaction) was used as a control to avoid false positive results potentially associated with pretreatment by proteinase K. A human lymph node was used as a control for activated caspase-3 (strong immunoreactivity was evident in the apoptotic-prone germinal centre B-lymphocytes of the lymph node and not in the mantle zone). Moreover, negative controls indicating the noninterference of TUNEL and secondary antibodies were performed by leaving out the primary antibodies (actin, caspase-3, PCNA and SC-35 respectively). Immunoistochemistry assays and Apoptotic rate counts were performed by two pathologists unaware of clinical and macroscopic pathologic data.

The clinical chart related to the index admission was retrospectively analyzed to obtain functional echocardiography data when available with a focus on variables that indicate left ventricular function and filling pressures such as left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), left atrial diameter, transmitral flow pattern and mitral regurgitation severity. The study protocol was approved by the University of Trieste Institutional Review Board.

Quantitative results are expressed in text, tables and figures as median (interquartile range). The non parametric Mann-Whitney U test and the Kruskal-Wallis test for non-paired data were used to compare AR among different subjects, when comparing two or more than two groups respectively. The Bonferroni’s correction was applied when necessary. The Chi-square test was used to compare proportions, with Fisher’s exact test used when one or more cells contained a value lower than 5. Correlation between continuous non-parametric variables was performed using the Spearman rank test. The software SPSS 15.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. The median time to death post AMI was 8 (4–22) days. The median age was 77 (62–87) years, 7 (58%) were males, all (100%) caucasians. All patients had symptomatic heart failure according to the current classification 15 and all had one or more co-morbidities contributing to death as indicated in Table 1. All deaths were in-hospital. Echocardiographic data were available in 6 patients (50%). Median LV ejection fraction was 37% (29–50), left atrial diameter was 42 mm (38–50), mitral E wave deceleration time 140 ms (95–200) and E/A ratio 0.9 (0.4–2.2).

TABLE 1.

Clinical characteristics of the 12 patients with fatal acute myocardial infarction and heart failure (consecutive number given based on age)

| Age (years) | Gender | Time from AMI to death (days) | Large AMI(*) | Ventricular Septal AMI | RV involvement at histopathology | Narrowed RCA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 37 | Man | 8 | + | 0 | + | + |

| 2 | 50 | Man | 4 | + | 0 | + | + |

| 3 | 59 | Woman | 16 | + | + | + | + |

| 4 | 69 | Man | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 70 | Man | 40 | + | + | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 72 | Man | 10 | + | + | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 82 | Woman | 4 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 82 | Man | 11 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 82 | Man | 42 | + | 0 | + | + |

| 10 | 89 | Woman | 5 | + | + | 0 | + |

| 11 | 90 | Woman | 4 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | 92 | Woman | 4 | + | 0 | + | + |

Abbreviations: AMI: acute myocardial infarction; RCA: right coronary artery; RV: right ventricle.

Extensive AMI= infarct extending more than 30% of left ventricle circumference at pathologic evaluation

In 5 patients with septal infarct (42%), involvement of the RV free wall was noted at histopathology, while no RV involvement was noted in the remaining patients. The median infarct size at the time of autopsy was 28% (19–34). Global cardiac dilatation was found in 7 cases (58%). Gross pathologic and standard microscopic examination showed that scar tissue consistent with recent necrotic cell death was evident in all patients. Importantly, as ongoing necrosis can confound the assessment of apoptosis, there was no evidence of very recent (<72 hours) or acute ongoing necrosis.

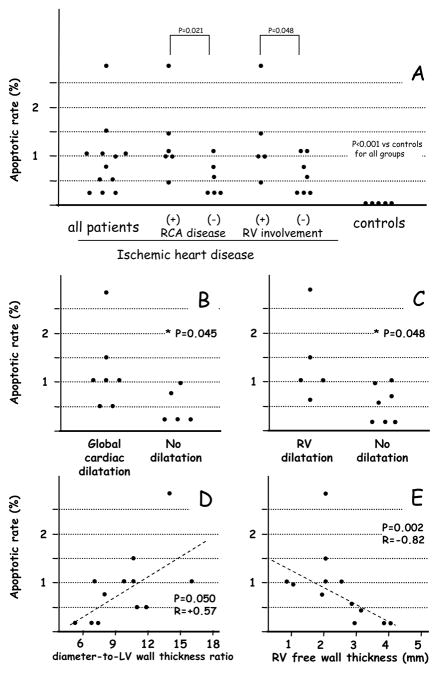

The apoptotic rate in the RV from patients with AMI was significantly higher than in the control hearts (0.8% [0.3–1.0] vs 0.01% [0.01–0.03], P<0.001)(Figure 1A). Apoptosis in unaffected LV from the patients with AMI was 2.2% [0.8–2.5] (P=0.026 vs RV apoptosis, _P<0.001 vs control hearts). RV apoptosis was independent of age, gender, time from MI to death, diabetes, or hypertension (data nor shown). RV apoptosis was not associated with a specific AMI location in the LV (data not shown) but hearts with septal infarct had higher RV apoptosis if the RV free wall was partially involved in the infarct. Moreover, RV apoptosis was significantly correlated with the number of coronary arteries affected by atherosclerotic disease with triple-vessel coronary artery disease having significantly higher AR (1.2%[1.0–2.5]) when compared to patients with double-vessel (0.6%[0.2–1.0]) or single-vessel coronary artery disease (0.4%[0.2–0.5])(P=0.048). RV apoptosis was significantly dependent on whether right coronary artery disease was present or not (independent of infarct location) with hearts with concomitant right coronary artery atherosclerotic disease having significantly higher AR (1.0%[0.9–1.8] vs those without right coronary artery disease 0.4%[0.2–0.8], P=0.021)(Figure 1A). Apoptosis in the RV was significantly higher in cases with RV involvement (1.0% [0.8–2.2] vs 0.5% [0.2–1.0], P=0.048; P<0.001 vs controls)(Figure 1A). The extent of apoptosis of RV correlated with signs of adverse cardiac remodeling at pathology. The apoptotic rate in RV was higher in cases with global cardiac dilatation (1.0% [0.5–1.5] vs 0.2% [0.2–0.9] in those without, P=0.045)(Figure 1B), and it was higher in patients with RV dilatation (1.0% [0.8–2.2] vs 0.5% [0.2–1.0] in those without, P=0.048)(Figure 1C). The apoptotic rate in the RV correlated significantly with the diameter-to-LV wall thickness ratio (R=+0.57, P=0.050), a marker of global cardiac remodeling (Figure 1D). The apoptotic rate in the RV was also significantly inversely correlated with RV wall thickness (R=−0.82, P=0.002)(Figure 1E) and directly correlated with diameter-to-RV wall thickness ratio (R=+0.87, P=0.001), indices of adverse RV remodeling.

Figure 1.

Panel A shows cardiomyocyte apoptosis in the unaffected right ventricular myocardium after acute myocardial infarction (left column) in comparison to RV myocardium in subjects who died of non cardiac causes (right column). Rates of cardiomyocyte apoptosis in subgroups of cases with and without right coronary artery (RCA) atherosclerotic disease and in cases with and without right ventricular (RV) involvement are shown in the central columns.

Panels B-E show the association between apoptosis in the right ventricle (RV) and signs of adverse remodeling at autopsy: increased cardiac diameter to left ventricle (LV) free wall thickness which is an index of global cardiac dilatation (panel B), increased tricuspid annulus circumference which is an index of RV dilatation (panel C), and the individual measurements (panels D and E).

To exclude the potential involvement of RV infarction, the association between apoptosis in the RV and cardiac remodeling was evaluated in the subgroup of patients without RV involvement (58%). There were significant correlations between the apoptotic rate in the RV and RV wall thickness (R=−0.91, P=0.002), diameter-to-LV wall thickness (R=+0.82, P=0.023), diameter-to-RV wall thickness (P=+0.90, P=0.006), and cardiac weight (R=+0.82, P=0.023). However, RV involvement and right coronary artery disease were significantly associated with 5 of 6 hearts with right coronary artery disease having RV involvement (83%) vs none of the 6 hearts without right coronary artery disease (0%, P=0.015).

Echocardiographic parameters from the same admission were available in 6 patients (50%). The apoptotic rate in the RV was not significantly correlated with functional parameters consistent with systolic dysfunction and/or increased filling pressures such as LV ejection fraction (R=+0.03, P=0.96), left atrial diameter (R=+0.50, P=0.39), E/A ratio at transmitral pulsed wave Doppler flow (R=+0.70, P=0.19), mitral E wave deceleration time (R=−040, P=0.50), and mitral regurgitation severity (R=+0.63, P=0.32).

DISCUSSION

In the current study we show for the first time that patients having LV AMI have elevated rates of apoptosis in areas of the RV wall. As apoptosis is considered to be a key pathologic failure for adverse cardiac remodeling and heart failure, the finding of elevated RV apoptosis suggests active processes occurring simultaneously in both ventricular walls that likely contribute to the development of heart failure.16–18

Our data, although limited by a small sample size, show that hearts with a large ventricular septal infarct and partial involvement of the insertions of the RV free walls had significantly greater apoptosis than the other hearts, suggesting that infarcts involving the septum are more likely to produce RV mechanical strain. Moreover, hearts with atherosclerotic disease of the right coronary artery, which supplies perfusion to most of the RV muscle, had significantly greater apoptosis, suggesting a role for decreased coronary blood flow and ischemia in remote non-infarcted regions.13 This observation is consistent with evidence of reduced coronary flow reserve and ischemia in non-culprit coronary arteries and myocardial regions in patients with acute coronary syndromes.19–20 Whether ischemia or mechanical strain are responsible for increased apoptosis remains unclear because in our small cohort those patients having narrowing of the right coronary artery were the same patients displaying signs of RV dilatation, making it impossible to distinguish the pathophysiologic role of the two processes.

As for the consequences of increased apoptosis in the RV wall, they are likely reflected in greater RV dilatation and RV free wall thinning. A delicate balance between cell death and survival indeed exists after an insult such as acute ischemia/infarction. The very same stimuli that trigger apoptosis also trigger cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Although speculative, it is possible that progressive RV free wall thinning and RV dilatation represent the shift of the balance toward cell death and loss of hypertrophy.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Norbert F. Voelkel (Virginia Commonwealth University) for critically reviewing the data and the manuscript, and Dr. Vera Di Trocchio (Virginia Commonwealth University) for her editorial assistance.

This study was supported in part by a grant from the Jeffress Memorial Trust Fund to A.A., a grant from FUTURA ONLUS (a non-for-profit organization) to A.B., and by grants from National Institutes of Health HL51045, HL59469, and HL79424 to R.C.K.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Patten RD, Aronovitz MJ, Deras-Meja L, Pandian NG, Hanak GG, Smith HJ, Mendelsohn ME, Konstam MA. Ventricular remodeling in a mouse model of myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:H1812–H1820. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.5.H1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brower GL, Janicki JS. Contribution of ventricular remodeling to pathogenesis of heart failure in rats. Am J Physiol. 2001;280:H674–H683. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.2.H674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirose K, Shu NH, Reed JE, Rumberger JA. Right ventricular dilatation and remodeling the first year after an initial transmural wall left ventricular myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1993;72:1126–1130. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(93)90980-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oakley C. Importance of right ventricular function in congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1988;62:14A–19A. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(88)80079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Salvo TG, Mathier M, Semigran MJ, Dec GW. Preserved right ventricular ejection fraction predicts exercise capacity and survival in advanced heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:1143–1153. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00511-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E. Ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction –Experimental observations and clinical implications. Circulation. 1990;81:1161–1172. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.4.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anversa P, Olivetti G, Capasso JM. Cellular basis of ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1991;68:7D–16D. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(91)90256-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krijnen PAJ, Nijmeijer R, Meijer CJLM, Visser CA, Hack CE, Niessen HWM. Apoptosis in myocardial ischaemia and infarction. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:801–811. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.11.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abbate A, Biondi-Zoccai GGL, Baldi A. Pathophysiologic role of myocardial apoptosis in post-infarction left ventricular remodeling. J Cell Physiol. 2002;193:145–153. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baldi A, Abbate A, Bussani R, Patti G, Melfi R, Angelini A, Dobrina A, Rossiello R, Silvestri F, Baldi F, Di Sciascio G. Apoptosis and post-infarction left ventricular remodeling. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:165–174. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abbate A, Biondi-Zoccai GGL, Bussani R, Dobrina A, Camilot D, Feroce F, Rossiello R, Baldi F, Silvestri F, Biasucci LM, Baldi A. Increased myocardial apoptosis in patients with unfavorable left ventricular remodeling and early symptomatic post-infarction heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:753–760. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02959-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bussani R, Abbate A, Biondi-Zoccai GG, Dobrina A, Leone AM, Camilot D, Di Marino MP, Baldi F, Silvestri F, Biasucci LM, Baldi A. Right ventricular dilatation after left ventricular acute myocardial infarction is predictive of extremely high peri-infarctual apoptosis at postmortem examination in humans. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:672–678. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.9.672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biondi-Zoccai GG, Abbate A, Vasaturo F, Scarpa S, Santini D, Leone AM, Parisi Q, De Giorgio F, Bussani R, Silvestri F, Baldi F, Biasucci LM, Baldi A. Increased apoptosis in remote non-infarcted myocardium in multivessel coronary disease. Int J Cardiol. 2004;94:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sinagra G, Bussani R, Abbate A, Piro M, Biondi-Zoccai GG, Kontos MC, Sabbadini G, Barresi E, Crea F, Biasucci LM, Aleksova A, Pinamonti B, Silvestri F, Vetrovec GW, Baldi A. Left ventricular diastolic filling pattern at Doppler echocardiography and apoptotic rate in fatal acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:307–309. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunt SA, Baker DW, Chin Mh, Cinquegrani MP, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, Goldstein S, Gregoratos G, Jessup ML, Noble RJ, Packer M, Silver MA, Stevenson LW, Gibbons RJ, Antman EM, Alpert JS, Faxon DP, Fuster V, Jacobs AK, Hiratzka LF, Russell RO, Smith SC., Jr American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association ACC/AHA guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:2101–2113. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01683-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voelkel NF, Quaife RA, Leinwand LA, Barst RJ, McGoon MD, Meldrum DR, Dupuis J, Long CS, Rubin LJ, Smart FW, Suzuki YJ, Gladwin M, Denholm EM, Gail DB National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Working Group on Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Right Heart Failure. Right ventricular function and failure: report of a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group on cellular and molecular mechanisms of right heart failure. Circulation. 2006;114:1883–1891. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.632208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sabbah HN, Stein PD, Kono T, Gheorghiade M, Levine TB, Jafri S, Hawkins ET, Goldstein S. A canine model of chronic heart failure produced by multiple sequential coronary microembolization. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:H1379–H1384. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.260.4.H1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferlinz J. Right ventricular function in adult cardiovascular disease. Progr Cardiovasc Dis. 1982;25:225–267. doi: 10.1016/0033-0620(82)90018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibson CM, Ryan KA, Murphy SA, Mesley R, Marble SJ, Giugliano RP, Cannon CP, Antman EM. Braunwald EImpaired coronary blood flow in nonculprit arteries in the setting of acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:974–982. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00335-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Araujo LI, Camici P, Spinks TJ, Jones T, Maseri A. Abnormalities in myocardial metabolism in patients with unstable angina as assessed by positron emission tomography. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 1988;2:41–46. doi: 10.1007/BF00054251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]