Abstract

Chlorosulfolipids have been isolated from freshwater algae and from toxic mussels. They appear to have a structural role in algal membranes and have been implicated in Diarrhetic Shellfish Poisoning. Further fascinating aspects of these compounds include their stereochemically complex polychlorinated structures and the resulting strong conformational biases, and their poorly understood (yet surely compelling) biosynthesis. Discussions of each of these topics and of efforts in structural and stereochemical elucidation and synthesis are the subject of this Highlight.

1 Introduction

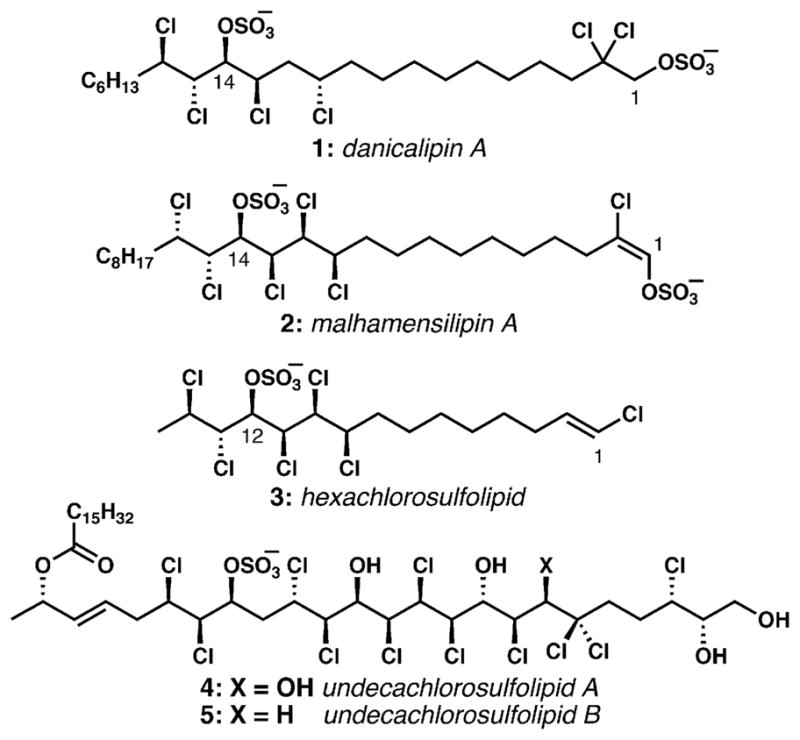

First reported as a new class of naturally occurring substances in 1969, the chlorosulfolipids (Fig. 1) went largely ignored by synthetic organic chemists for the ensuing forty years. In that time, this family of natural products has grown to include lipids that are integral components of algal membranes (1), protein kinase inhibitors (2), and causative agents of Diarrhetic Shellfish Poisoning (3–5). Their stereochemically intricate structures imply fascinating biosyntheses, and the exquisite conformational bias imposed upon these acyclic structures by the arrays of chlorine-bearing asymmetric centers must be intimately related to their unknown functions in the producing organisms. In short, the chlorosulfolipids are an intriguing puzzle of evolutionary biochemistry.

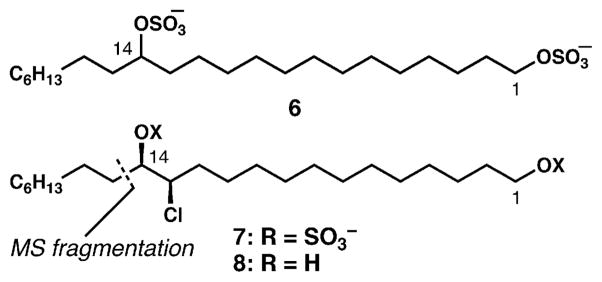

Fig. 1.

Representative chlorosulfolipids from algae (1, 2) and from toxic mussels (3–5).

2 Structural elucidation, biosynthesis and biological relevance

2.1 Discovery and early structural elucidation of the lipids from the alga Ochromonas danica

In 1962, sulfated lipids of unknown structure were isolated by Haines and Block from the chrysophyte Ochromonas danica.1 Subsequent studies by the Haines group revealed that two sulfate groups were incorporated on each lipid backbone.2,3 They cleaved these sulfate linkages to reveal diols which were much easier to isolate and characterize; the first sulfolipid whose structure was fully clarified was 1,14-docosanediol disulfate (6, Fig. 2). Shortly thereafter, it was discovered that many of the components in the crude sulfolipid extracts were chlorinated. The Haines group completely elucidated the structure of monochlorinated lipid 7, including its absolute configuration.4 Simultaneously and independently, while examining fatty acid biosynthesis in O. danica, Elovson and Vagelos described the isolation of several polychlorodiols by acid hydrolysis of sulfolipids from this organism, and used mass spectrometry to show that the diols contain one to six chlorine atoms substituting for hydrogen along a 22-carbon (docosane) hydrocarbon chain.5 Comprising an estimated 3% of the dry cell weight and 15% of the total cellular lipids, these previously unknown compounds warranted further examination.

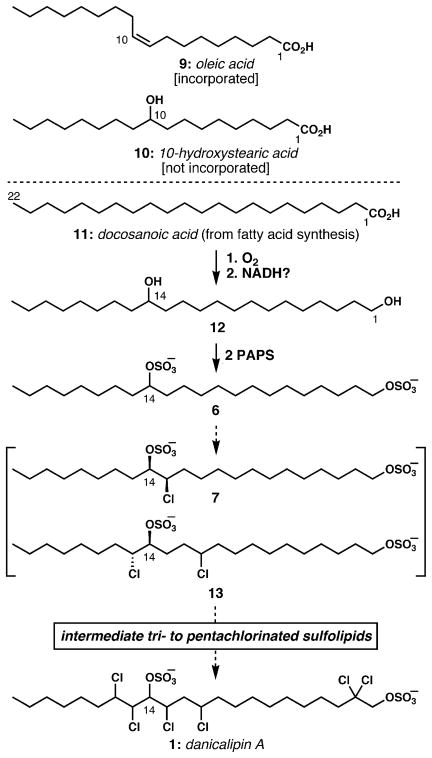

Fig. 2.

Structures of the two simplest sulfolipids from O. danica.

The structure of monochloride diol 8 (and hence lipid 7) was assigned4 by diagnostic mass spectrometric fragmentation (cleavage α to oxygen) that delivered a fragment consisting of 14 carbon atoms, 1 chlorine atom and 2 oxygen atoms. The structural assignment was further solidified by treatment of diol 8 with base to generate the corresponding cis-epoxide, which clearly signified the presence of a vicinal chlorohydrin with syn configuration. The absolute configuration was assigned by comparison of optical rotation data with known standards available at the time, and proved to be correct.

Heroic degradation and derivatization experiments were necessary for the structural elucidation of hexachlorinated lipid 1 by Elovson and Vagelos.6 Because chlorine atoms do not promote mass-spectrometry-induced cleavage at the carbon to which they are attached, it was necessary to substitute them with groups which would do so, to allow for the precise assignment of the six chlorine atoms to their respective carbon atoms. Discussion of the entire sequence of reactions is beyond the scope of this article, but one key point in the strategy was the use of 36Cl-labeled chlorosulfolipid, obtained by growth of O. danica on 36Cl−, as a starting point. In this way, assaying radioactivity in the reaction products and in aqueous extracts of the reaction mixtures (which would contain liberated chloride) provided information about whether chlorides were displaced/eliminated in the process. Key degradative steps included base-promoted epoxide formations, conversion of the C2-dichloride to the corresponding ketone, and an assortment of elimination, periodate cleavage, and inter- and intramolecular nucleophilic displacement steps. Each of the intermediates along this degradative pathway was analyzed and their structures corroborated by mass spectrometry. This work was a cleverly executed tour-de-force in structure elucidation, and it correctly yielded the planar structure of the major chlorosulfolipid from O. danica, which would later be named danicalipin A (1, Fig. 1).

The structure and configuration of simple chlorosulfolipid 7 and the connectivity of danicalipin A (1) and some of its less chlorinated relatives represent the extent to which structural elucidation was feasible with the O. danica chlorosulfolipids at the time;7–9 these compounds were revisited in 2009 via synthesis by our group10 and re-isolation and NMR spectroscopic analysis by the Okino group11 (see below).†

2.2 Biosynthesis of the O. danica lipids

During the 1970s, the groups of Haines, Elovson, and Mercer independently investigated the biosynthetic origin of the chlorosulfolipids in O. danica.12–17 The Haines group demonstrated the ready incorporation of 14C-labeled acetate and the intact integration of several 14C-labeled fatty acids,12 suggesting that the hydrocarbon chain is first constructed via the normal fatty acid biosynthetic pathway, and later functionalized with the polar substituents. Noting the incorporation of oleic acid (9, Scheme 1), this group hypothesized that an alkene hydration event introduced the eventual C14-hydroxyl group, prior to chain elongation to the 22-carbon hydroxy acid, and reduction to the 1,14-diol.12,13 According to this hypothesis, 10-hydroxystearic acid (10) should be a reasonable biosynthetic precursor; however, Elovson reported that this substrate showed sluggish incorporation, implying that it is not a biosynthetic intermediate en route to the chlorosulfolipids.14 On the other hand, docosanoic acid (11) was much more rapidly assimilated. By growing the algae in an 18O2-enriched medium, Elovson demonstrated that direct oxidation of the fully saturated fatty acid chain with molecular oxygen was the origin of the secondary hydroxyl group, and that it did not arise from water. Further evidence that alkene hydration was not involved was gleaned from the growth of the organism in H218O, which resulted in label incorporation only in the primary hydroxyl group, which presumably resulted from exchange processes on the carboxylic acid. On the basis of these and other important experiments12–17 the order of events has been proposed collectively by these research groups to be: fatty acid synthesis → docosanoic acid → 14-hydroxydocosanoic acid → docosane-1,14-diol. Enzyme-mediated transfer of the sulfate group of 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate (PAPS) to the diol was postulated to be the final step in the biosynthesis of sulfolipid 6.13,15

Scheme 1.

Current understanding of the O. danica lipid biosynthesis.

Throughout all of these studies, a minor series of tetracosane (24C, two more than the predominant series) chlorosulfolipids were observed, usually in about 10–15% relative abundance compared with the docosane series.7 Most unusual in the tetracosane series is the location of the secondary sulfate group: it is positioned at C15, one carbon down the chain compared to the docosane lipids (see below).

Few details are known regarding the incorporation of chlorine into the bis-sulfated hydrocarbon backbone. Thomas and Mercer showed that chlorination occurs in a stepwise fashion; using radiolabeling, they demonstrated conclusively that less chlorinated lipids resubjected to the culture medium are further chlorinated.16 Each of the chlorine substituents are located on unactivated carbon atoms; therefore, it is unlikely that enzymes such as haloperoxidases, which generate electrophilic chlorine, are responsible for introduction of the chlorosulfolipid substituents. Because the chlorides are introduced one by one, the possibility of enzymatic alkene dichlorination is highly unlikely. Logically, Haines postulated that the chlorines are incorporated by free-radical processes,13 but at that time, enzymes that catalyzed such oxidations were unknown. Recently, Walsh has discovered a new class of α-ketoglutarate-dependent non-heme iron halogenases that halogenate unactivated methyl groups via a free-radical process.18 Similar halogenases might be operative in the halogenation of the unactivated methylenes of the lipids of O. danica. Given the reasonably well-established sequence of biosynthetic monochlorinations,16 the isolation of both C13-monochloride 7 and C11, C15-dichloride 13 is unusual. Because the C13 chloride of 7 is absent in the dichlorinated lipid, the order of chlorination does not necessarily always follow the same linear path; as Thomas and Mercer wrote, “The precise sequence of chlorination is likely to be complex and occur via a matrix rather than a direct route. The nature of this matrix will not become apparent until the structures of all members … have been elucidated.”16

2.3 Chlorosulfolipids from other algal species

In the early 1970s Mercer and Davies detected docosane chlorosulfolipids from the filamentous alga Tribonema aequale (class Xanthophyceae, yellow-green algae) that, similar to those from O. danica, bear one to six chlorine atoms and two sulfate groups.19 Though extensive degradative studies were not performed, isolation and analysis of O. danica lipids in an identical manner were done for comparative purposes. The GC–MS traces of the compounds from each source were identical. Mercer and Davies went on to report detection of chlorosulfolipids in two other members of Xanthophyceae, two members of Chlorophyceae and a member of Cyanophyceae (cyanobacteria), albeit in much smaller quantities than in O. danica.20 In 1979, Mercer and Davies studied the distribution of chlorosulfolipids in 30 species of algae, both marine and freshwater, from a variety of different classes and orders.21 Their results suggest that these lipids are relatively widespread in freshwater algae, but their abundance in all other species studied was lower than in O. danica and the closely related O. malhamensis. No chlorosulfolipids were found in the marine algae surveyed.

In 1994, the groups of Slate and Gerwick reported the isolation of malhamensilipin A from the alga Poterioochromonas malhamensis (renamed from O. malhamensis); this lipid displayed antimicrobial activity and moderate pp60 protein tyrosine kinase inhibition.22 Advances in NMR spectroscopy since the original chlorosulfolipid isolations allowed for the determination of the gross chemical structure of malhamensilipin A (see 14, Fig. 3) without recourse to degradation experiments or extensive reliance upon mass spectral fragmentation patterns. Lipids produced by this organism were largely of the tetracosane (24C, corresponding to the minor series of lipids in O. danica) variety, but the overall structure of the lipid bore striking resemblance to the lipids produced by O. danica. Two distinct features of this molecule, however, were the presence of the unique chlorovinylsulfate group and location of the secondary hydroxyl group at C14 (compare C14 of the docosane and C15 of the tetracosane lipids of O. danica, see 15‡).8,9 This variance with respect to the position of the secondary alcohol (sulfate) among freshwater-algae-derived lipids remains unexplained. Within the chlorovinyl sulfate, the absence of an nOe correlation between the protons on C1 and C3 suggested an E-alkene geometry, but the inaccessibility of model compounds precluded confirmation of this assignment by chemical shift correlation. While it seems most likely that the chlorovinyl sulfate is generated by elimination of HCl from a precursor 2,2-dichloro-1-sulfate related to those found in the O. danica lipids, the observation of pentachlorinated tetracosane lipid 16‡ (with only one chloride at C2) does allow for the possibility of a desaturation event on such a β-chlorosulfate. A further unusual feature was the absence of a sulfate group on the secondary hydroxyl group, which differed from the O. danica lipids. In 2010, our group collaborated with the Gerwick group to revise and refine the structure of malhamensilipin A from 14 to bis(sulfate) 2,23 including its relative and absolute configuration, by a combination of mass spectrometric and NMR methods. This assignment was verified by synthesis (Section 3.2).24

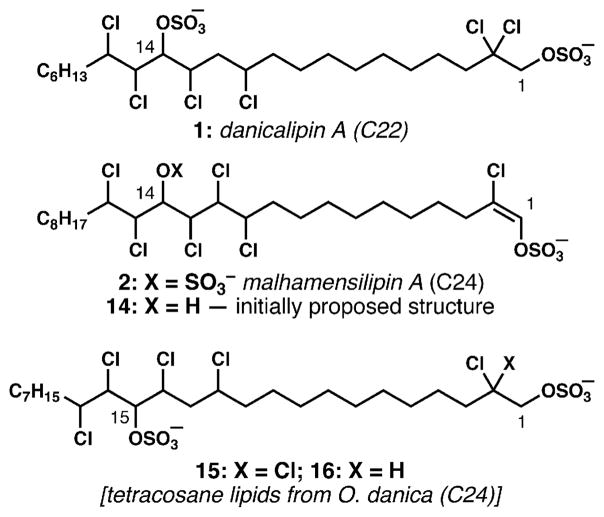

Fig. 3.

Malhamensilipin A structure and a comparison of the oxygenation pattern among freshwater chlorosulfolipids.

2.4 Chlorosulfolipids from toxic Adriatic mussels

Between 2001 and 2004, the group of Ciminiello and Fattorusso reported the isolation of chlorosulfolipids 3–5 from the digestive glands of toxic mussels.25–27 These lipids were deemed to be the causative agents in Diarrhetic Shellfish Poisonings and were found during periods of toxicity associated with algal blooms in the northwestern Adriatic Sea. Lipid 3 bears structural similarity to both the O. danica and P. malhamensis chlorosulfolipids, but with a truncated alkane terminus and a vinyl chloride in place of the usual sulfate bearing C1-terminus. Lipids 4 and 5 share a fascinating and unprecedented structure, containing eleven chlorine atoms, multiple hydroxyl groups, and a sulfate group arranged in daunting arrays of contiguous stereogenic centers. Application of Murata’s J-based configurational analysis (see below)28 to lipids 3–5 permitted, for the first time, determination of the relative configuration of polychlorinated sulfolipids; application of the modified Mosher method29 established their absolute configurations. In 2010, the Sheu group reported the isolation of chlorosulfolipid 3 and analogs devoid of the sulfate and C1 (vinyl) chloride from the Formosan octoral Dendronephthya griffini,30 suggesting that the marine algae that produce these chlorosulfolipids are widespread and might be either food for or symbionts with a number of different higher organisms. It is curious that both marine and freshwater algae produce chlorosulfolipids.

2.5 Elucidation of chlorosulfolipid relative configuration and solution conformation by NMR

Murata’s J-based configurational analysis28 was developed to assign relative configurations of acyclic, conformationally biased, stereochemically rich portions of natural products, chiefly in the arena of polyketides. The method relies on the ability to measure 3JH,H, 3JC,H and 2JC,H coupling constants.31 Both 3JH,H and 3JC,H coupling constants follow a Karplus curve that relates their magnitude to dihedral angle; they can be used to elucidate conformation (Fig. 4a). 2JC,H has dependence on the dihedral angle between an electronegative substituent on the carbon and the adjacent proton; the Murata method was developed with oxygen substituents as the key electronegative groupings. When the electronegative substituent is gauche to its vicinal proton, 2JC,H is large, and when it is anti, it becomes small. Assimilation of these data and nuclear Overhauser effect (nOe)/rotational nuclear Overhauser effect (rOe) data (necessary in certain cases only) allows for the determination of solution conformation, in the form of a Newman projection; the relative configurations of adjacent stereogenic centers are thus determined. Ciminello and Fattorusso were the first to extend this method to polychlorinated molecules in the structural elucidation of 3–5, wherein they made the logical assumption that chlorine substituents would behave similarly to the oxygen substituents used by Murata.25–27 In an important 2010 paper,32 the Carreira group confirmed that J-based configurational analysis is generally applicable in the context of polychlorinated molecules, corroborating the assignments made using this method with X-ray crystallographic structure determination, as well as recalibrating the magnitudes of expected coupling constants using appropriate synthetic samples. Representative coupling data from Carreira’s report of the synthesis of (±)-333 are shown in Fig. 4b to demonstrate how the relative configuration of the stereogenic centers from C12 to C14, and the conformation about the connecting bonds, were determined (the isolation paper only provided qualitative coupling data, large or small).25

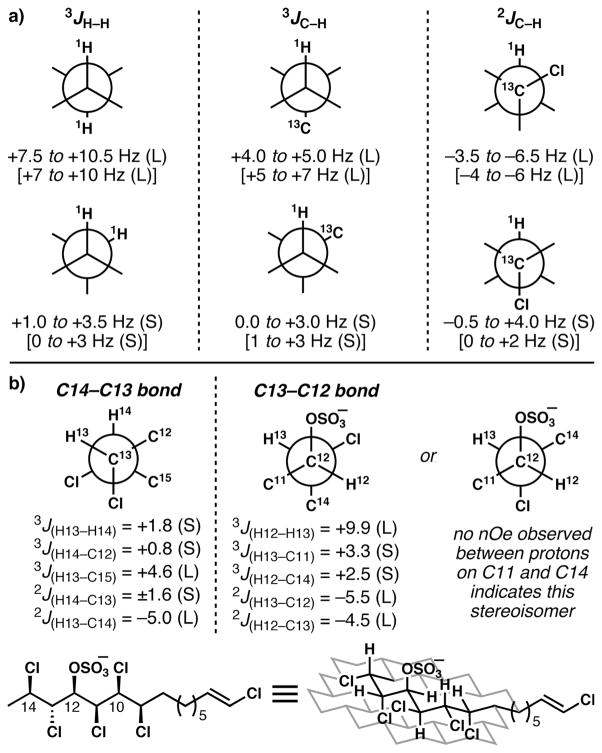

Fig. 4.

a) Murata’s J-based configurational analysis as calibrated for chlorine-bearing analytes by Carreira et al. [values in brackets are Murata’s values for oxygenated substrates]. b) Application to lipid 3 and the solution conformation of this lipid derived from this method.

It should be emphasized that for molecules that display substantial conformational biases, including the chlorosulfolipids, this powerful method also provides important information about their solution structure. Although they never made the point explicitly, the coupling data obtained by Fattorusso and Ciminiello25–27 were sufficient to determine the major solution conformations of these lipids; for example, simpler lipid 3 adopts the conformation shown in Fig. 4b. This conformational preference can be understood by considering the tendency of the lipid to avoid all syn-pentane-like interactions (steric preference) and to maximize the relative gauche orientations of vicinal polar groupings (stereoelectronic preference);34 lipids 1 and 2 were later found to adopt similar conformations. Carreira’s tour-de-force in establishing an NMR database for polychlorinated, hydroxylated alkanes further demonstrated these conformational preferences among a large number of synthetic molecules.32 O’Hagan’s beautiful work in the synthesis and study of stereodefined vicinal polyfluorides,35 performed prior to and concurrent with the synthetic work on the chlorosulfolipids, also demonstrates the capacity for imposing molecular order in polyhalogenated molecules.

In 2009, in conjunction with the Gerwick group and Haines, we determined the relative and absolute configuration of O. danica lipid 1 by the Murata and modified Mosher methods, respectively, and named it danicalipin A.10 Synthesis was a key component of this work (Section 3.2). The same year, the Okino group reported the isolation of eight chlorosulfolipids from O. danica, including five previously undocumented ones.11 Their careful analysis revealed the relative and absolute configuration of many lipids whose structural information was previously limited to connectivity assigned by mass spectrometry.

In 2010, the Gerwick group together with our group revised the structure of malhamensilipin A.23 We first verified by HR-ESIMS that the chlorosulfolipid indeed bears a labile secondary sulfate group. The alkene geometry was confirmed by synthesis of model compounds; the chemical shifts of the E- and Z-isomers were found to be diagnostic. Finally, the relative and absolute configurations were determined using the Murata and modified Mosher methods, respectively, and these assignments were ultimately corroborated by an enantioselective synthesis (Section 3.2).24

2.6 Biological relevance of the chlorosulfolipids

The significant quantity of chlorosulfolipids present in O. danica membranes suggested a structural role for these lipids. A study by Brown and Elovson showed that this organism contains minimal quantities of phospholipids, which are nearly ubiquitous in biological systems.36 These workers noted that this alga contains a substantial quantity of another unusual polar lipid—a diacylated glycerol ether of N,N,N-trimethylhomoserine which, by virtue of its cationic nature, might be a reasonable replacement for phospholipids in the cell membrane. In a later study,37,38 Haines and coworkers documented that the flagellar membrane is devoid of phospholipids, and that chlorosulfolipids represent about 90 mol% of its polar lipids. Accompanying data suggest that the chlorosulfolipids are also significant components of the cell membrane, although the composition was not quantified. As mentioned above, the cell membrane does contain the unusual charged lipid discovered by Brown and Elovson, but it is not present in significant quantities in the flagellar membrane.

That the chlorosulfolipids make up such a significant portion of the membrane lipids, especially that of the flagellum, strongly suggests a structural role; however, a typical bilayer morphology is difficult to reconcile with these lipids which, in addition to the well-placed terminal sulfate, display a second, charged sulfate two-thirds of the way down the chain. If the lipid displays an extended arrangement within a typical membrane structure, that polar group would need to reside in the middle of the hydrophobic portion of the membrane, an energetically unfavorable situation. The possibility of hairpin-like structures of these lipids is readily discounted based on the congestion imparted by the chloride and sulfate substituents; the lipid is not able to adopt sharp turns. Furthermore, the chlorosulfolipids are water-soluble, further complicating the proposition of incorporation into membranes. The continuity of cell and flagellar membranes had been observed, and freeze fractures of the O. danica cell membrane demonstrated a fracture plane representative of a bilayer structure.37 Somehow, this organism is apparently able to integrate such an improbable lipid structure into important biological membranes, creating one of the major unanswered questions in this area of research: How can these unusual lipids organize in a thermodynamically feasible way into a membrane capable of sustaining the life of the alga? Haines has logically postulated that there must be some molecular entity, perhaps a divalent metal atom or protein bearing appropriately charged residues, that offsets the requisite negative charge of the sulfate group at physiological pH.37 The discovery of the mechanism of stabilization of chlorosulfolipid bilayers will presumably go a long way toward understanding the function and purpose of these evolutionarily unusual membranes.

The earliest report by Vagelos noted that cell-free extracts of O. danica shut down fatty acid biosynthesis, and this activity was correlated to the presence of the detergent-like chlorosulfolipids.5 The Okino group also reported the toxicity of the danicalipins to brine shrimp, and that the toxicity is not correlated to the level of chlorine substitution, suggesting that it is the amphiphilic (detergent-like) properties of the molecules that make them toxic.11 It is fascinating that molecules with such inherent, broad-spectrum toxicity can be biosynthesized and incorporated into membranes in such large amounts without detriment to the health of the alga.

The human toxicity of the mussel-derived lipids (3–5)25–27 associated with Diarrhetic Shellfish Poisoning adds another dimension of biological interest to these compounds. The mussel-derived lipids only have one sulfate group per molecule, and might not share the general toxicity, or detergent activity toward enzymes, of the freshwater algae-derived lipids. Nonetheless, their toxicity ushered in a new class of shellfish poisons, structurally very distinct from the previously well-known polyether and guanidinium toxins. Each of these lipids demonstrated moderate cytotoxicity against representative cancer cell lines, though no experiments to gauge selective toxicity were reported.

3 Synthetic studies

3.1 Relevant methodology

Aside from some early chemical experiments by Haines to secure the structure of the simplest O. danica chlorosulfolipids,4 these compounds went essentially unstudied by synthetic chemists for nearly four decades. Certainly, the unique structures of these lipids, the toxicity associated with the mussel-derived compounds, and their unknown biological purpose make them attractive targets for synthesis. The paucity of material isolated from Adriatic mussels and the difficulty associated with isolation and purification of the freshwater lipids hampered the biological study of chlorosulfolipids; total synthesis might provide a vector whereby sufficient quantities of material may be accumulated. Three research groups—ours, Carreira’s, and Yoshimitsu/Tanaka’s—have been actively engaged in the development of methodologies and strategies for chlorosulfolipid synthesis in the past few years.

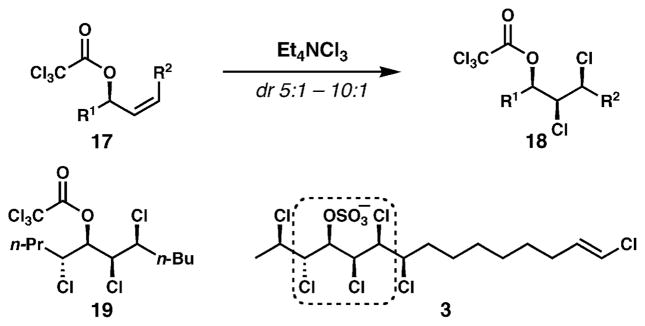

Vanderwal’s diastereoselective dichlorination

In 2008, we published the first paper describing synthetic chemistry inspired by the chlorosulfolipids.39 Clearly, the Carreira and Tanaka/Yoshimitsu groups were heavily involved in their own studies of these fascinating molecules at that time. Recognizing that hydroxyl (or sulfated hydroxyl) groups were interspersed among the chlorides in all chlorosulfolipids, we sought a method to stereoselectively dichlorinate chiral secondary allylic alcohols. In an effort to access the syn,syn-hydroxydichloride stereotriad that is frequently seen in lipids 3–5, Z-allylic alcohol derivatives were studied; trichloroacetate derivatives (17, Fig. 5) were dichlorinated using Mioskowski’s reagent (Et4NCl3)40 with useful levels of control (usually above 8 : 1 dr). Application to an allylic chlorohydrin derivative efficiently and diastereoselectively delivered 19, which bears the central stereotetrad found in mussel-derived lipid 3. Unfortunately, strategies that would incorporate the flanking chlorides and enable the use of this method for the synthesis of 3 and related lipids were never reduced to practice.

Fig. 5.

Diastereoselective dichlorination of Z-allylic trichloroacetates to generate key motifs of the chlorosulfolipids.

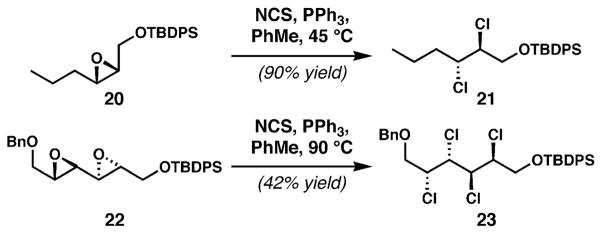

The Yoshimitsu/Tanaka deoxydichlorination of epoxides

The CCl4/PPh3 system, essentially the Appel reagent for conversion of alcohols to chlorides, had been previously reported by Isaacs and Kirkpatrick to convert simple epoxides to dichlorides;41 the Yoshimitsu group expanded the use of this reagent system to acyclic systems relevant to the chlorosulfolipids (see 20 → 21, Scheme 2). Their report,42 which included outstanding examples of stereospecific diepoxide to tetrachloride conversions (22 → 23), appeared essentially concurrently with our method for dia-stereoselective dichlorination, and provided an important tool with which to approach the chlorosulfolipids. The combination of this reaction with the Sharpless asymmetric epoxidation of allylic alcohols presents a valuable entry into enantioenriched polychlorides.

Scheme 2.

Tanaka and Yoshimitsu’s deoxydichlorination of epoxides.

3.2 Completed chlorosulfolipid syntheses

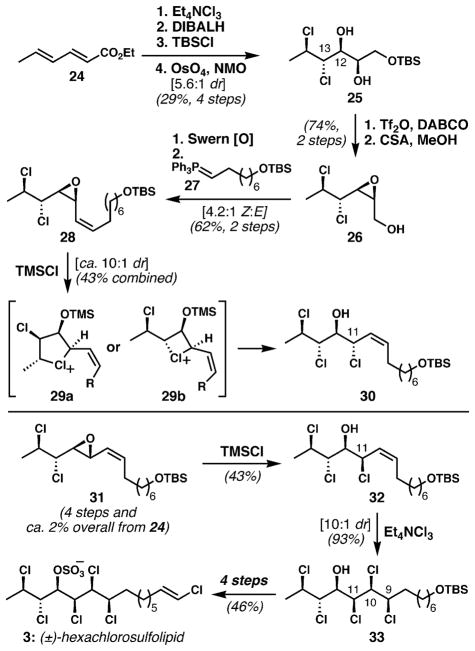

Carreira’s synthesis of (±)-hexachlorosulfolipid

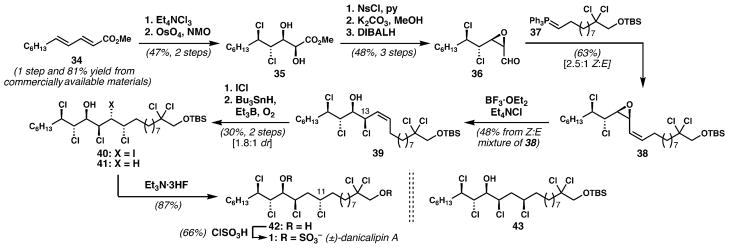

In 2009, the Carreira group reported the synthesis of (±)-hexachlorosulfolipid (3), the first synthesis within this class of targets.33 They alluded to multiple failed attempts to synthesize its key polychlorinated motif prior to the development of their successful route, and commented that displacement of activated alcohol derivatives with chloride was difficult, particularly when the carbinol was flanked with chlorine atoms. They also noted that chlorinated aldehydes were problematic compounds, which presumably undermined carbonyl addition strategies that would require α-chloro or α,β-dichloroaldehydes as intermediates. Ultimately, they succeeded with a strategy based on alkene functionalization (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

The Carreira group’s synthesis of (±)-hexachlorosulfolipid (3).§ Numbering corresponds to that used in lipid 3.

Ethyl sorbate (24) underwent stereospecific dichlorination of its less electron-poor alkene, followed by reduction of the ester and protection of the resulting alcohol. Diastereoselective dihydroxylation (5.6 : 1 dr) of the remaining alkene provided 25. This outcome was consistent with Kishi’s model for allylic alcohol dihydroxylation;43 in this case, one can presume that the allylic chloride plays an important stereocontrolling role. After separation, the major diastereomer was treated with triflic anhydride and DABCO to afford, after deprotection, epoxy alcohol 26. This efficient epoxide formation is noteworthy for its high regioselectivity. Oxidation and in situ Wittig homologation with phosphorane 27 gave vinyl epoxide 28 as a 4.2 : 1 (Z : E) mixture of isomers. Opening of the epoxide was expected to occur exclusively at the activated C11 position via inversion of configuration to furnish an allylic chloride with the C11–C14 stereotetrad matching that of target 3 (see 32). Treatment of 28 with TMSCl, according to the procedure of Llebaria,44 afforded an allylic chloride that was processed to a diastereomer (not shown) of lipid 3 that proved epimeric at carbons 9, 10, and 11, as determined by Murata’s J-based configurational analysis. It appeared that the epoxide chlorinolysis had occurred with retention of configuration, rather than the expected inversion. This result was attributed to anchimeric assistance from non-innocent chlorides. Related processes had been noted in epoxide solvolysis studies dating back to 1971.45 This unexpected stereochemical result was put to productive use: the relative configuration of the epoxide was changed appropriately to favor the desired configuration (see 31 → 32). Of course, this strategy depended upon anchimeric assistance also taking place in the stereoisomeric epoxide; fortunately, this expectation was borne out by experiment. Stereocontrolled dichlorination afforded 33, presumably under control of the C11 stereogenic center and dependant upon minimization of A1,3-strain. Installation of the vinyl chloride moiety under standard conditions and sulfation completed the first synthesis of 3 (or of any chlorosulfolipid). This concise synthesis could provide material for biological and pharmacological studies, including improved methods for analysis and detection to obviate occurrences of Diarrhetic Shellfish Poisoning.

Vanderwal’s synthesis and structural determination of (±)-danicalipin A

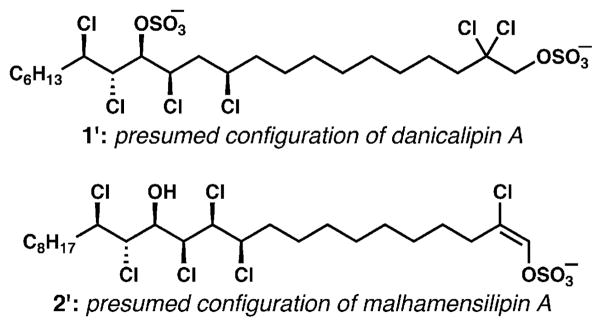

Concurrent with Carreira’s synthesis, our group was also engaged in efforts toward the synthesis of the chlorosulfolipids. The simplest mussel-derived lipid (3), the O. danica lipids (for example, 1) and malhamensilipin A (2) share many structural similarities. It was almost certain that all of these compounds were biosynthesized by algae. Therefore, it was tempting to speculate that the biosynthesis of these compounds would be closely related, and that the configurations just might be identical throughout. Fortunately, Haines had provided us a sample of desulfated hexachlorinated O. danica lipid (stable to benchtop storage for close to 30 years!) sufficient for NMR analysis. Circumstantial evidence for stereochemical conservation, in the form of similar 3JH–H coupling constants along the contiguous stretch of methine protons in each of these three lipids, was promising. Finally, the early studies of Haines that established the relative configurations of two of the less chlorinated O. danica lipids (see 7 and 13 in Scheme 1), whose stereochemistry should match that of 1, completely fit our speculation. On this basis, we hypothesized that the configurations of 1 and 2 would match that of 3, for which the configuration was known (Fig. 6). As a result, we targeted structures 1′ and 2′ in addition to 3 in our synthetic program.

Fig. 6.

Presumed configurations of lipids 1 and 2 based on analogy to hexachlorosulfolipid 3.

We first attempted to apply chloroacetate aldol, chloroallylation, and chloropropargylation reactions of chlorinated aldehyde electrophiles in combination with our diastereoselective alkene chlorination protocol to target 3, because its configuration was known. Unfortunately, this approach did not prove workable and was abandoned, yielding to an alkene functionalization strategy conceptually identical to that concurrently implemented by the Carreira group. The disclosure of the Carreira synthesis of 3 and the similarity of our approaches caused our group to shift focus completely to the synthesis and structural determination of danicalipin A (1), whose configuration was unknown beyond our unpublished hypothesis, and whose implication in biological membranes was cause for fascination. We were already engaged in a combined synthetic and spectroscopic approach to determining the configuration of lipid 1, the first step toward validating our stereochemical hypothesis. Because of early technical challenges in implementing the J-based configurational analysis on this desulfated chlorosulfolipid, we proceeded on the assumption that the configuration of 1 was identical to that of 3 (see 1′).

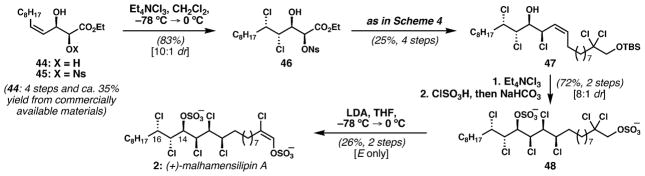

The enoate derived from dichlorination of diene 34 was dihydroxylated diastereoselectively to give 35 (ca. 9 : 1 dr);43 and Sharpless’s procedure for selective nosylation of the α-hydroxyl group of α,β-dihydroxyesters46 was perfectly applicable even in this specific case with γ- and δ-chlorides (Scheme 4). Phosphorane 37 was coupled with aldehyde 36 to yield vinyl epoxide 38 as a 2.5 : 1 (Z : E) mixture of alkene isomers. Exposure of the Z-vinyl epoxide to the chlorinative ring opening conditions prescribed by Llebaria44 led unexpectedly to a stereoisomeric mixture of C13 allylic chlorides (not shown). As we began investigating this unexpected outcome, the Carreira disclosure made clear the reason behind the stereochemical course of this reaction. After much experimentation, we found that a stereo-specific invertive ring opening could be achieved using excess BF3·OEt2 and Et4NCl and, in practice, applying this combination of reagents directly to the Z/E mixture of vinyl epoxides afforded the desired Z-syn-chlorohydrin 39 in respectable yield. Together, the Carreira discovery and our protocol allow for stereodivergent chlorinative ring openings of these specific types of vinyl epoxides.

Scheme 4.

Vanderwal’s synthesis of (±)-danicalipin A.

A regio- and diastereoselective hydrochlorination of alkene 39 was needed to introduce the last stereogenic center in 1. To this end, 39 was iodochlorinated to afford 40 with complete regio-control, but poor stereocontrol (1.8 : 1 dr). Selective reduction of the iodide and removal of the silyl protecting group from the major diastereomer provided a diol (42) whose NMR spectra were superimposable on those derived from the diol provided by Haines. Furthermore, the diastereomeric hexachlorides (compare 41 and 43) obtained by reductive deiodination demonstrated substantially different NMR spectra, which was important since they differed only in the configuration of the one isolated chlorine-bearing stereogenic center at C11. The relative configuration of the lipid target had remained unknown until this point – we had synthesized the correct structure but still were unsure of its stereochemical features.

Our newly established, critical collaboration with the Gerwick group finally enabled implementation of the J-based configurational analysis on synthetic diol 42, which revealed the configuration at C11 to be opposite to that observed in mussel-derived lipid 3 and to the presumed stereostructure 1′; this difference is intriguing from a biosynthetic perspective. Finally, the synthesis of 1, which was given the more tractable name “danicalipin A” was then realized by sequential treatment of diol 42 with ClSO3H followed by NaHCO3; this accomplishment constituted the first synthesis of a bis(sulfated) chloro-sulfolipid,10 and was the first polychlorinated lipid from O. danica to be fully characterized, including the absolute configuration of the natural sample, which was determined by modified Mosher method.

Vanderwal’s synthesis of (+)-malhamensilipin A

Following structural revision of malhamensilipin A in collaboration with the Gerwick group,23 we sought to accomplish its synthesis. As mentioned above, we had developed a syn-selective dichlorination reaction of Z-allylic esters, which was therefore unsuitable for the C14–C16 stereotriad of malhamensilipin A. We needed to find some way to suitably direct the anti-dichlorination of a C15–C16 alkene. Starting from a diol of type 44 (Scheme 5) was attractive because we could use Sharpless asymmetric dihydroxylation to begin an enantioselective synthesis. Fortuitously, dichlorination of enantioenriched α-nosylated diol 45 delivered stereotetrad 46 in good yield and selectivity 10 : 1 dr); the nosyl ester was required for subsequent conversion to the corresponding epoxide. Conversion of 46 to Z-allylic chloride 47 proceeded uneventfully according to the sequence used in our danicalipin A synthesis (see Scheme 4). Alkene dichlorination (8 : 1 dr) followed by deprotection with concomitant sulfation afforded bis-sulfate 48. Regio- and stereoselective elimination of HCl from 48, which contains seven chlorine atoms and two sulfates, was required to install the E-chlorovinyl sulfate. Using a reaction developed in model systems to elucidate the geometry of the chlorovinyl sulfate of 2,23 subjection of 48 to excess LDA at −78 °C in THF delivered a clean reaction mixture whose 1H NMR revealed the presence of a single alkene product, which proved to be malhamensilipin A. Isolation of enantioenriched malhamensilipin A was possible in only moderate yield, due to the difficulties in separation from starting material. This synthesis is noteworthy for the high degree of stereocontrol in the introduction of all the polar substituents.24

Scheme 5.

Vanderwal’s enantioselective synthesis of malhamensilipin A, featuring a selective elimination to install the E-chlorovinyl sulfate.

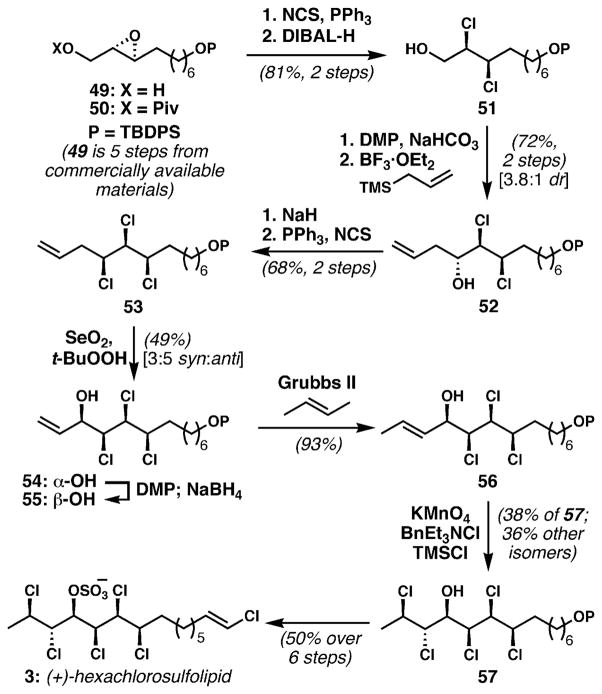

The Yoshimitsu/Tanaka synthesis of (+)-hexachlorosulfolipid

Yoshimitsu and coworkers applied their epoxide deoxydichlorination methodology42 to the synthesis of (+)-hexachlorosulfolipid (3),47 which was reported nearly concurrently with our synthesis of (+)-malhamensilipin A; these two achievements marked the first enantioselective syntheses of chlorosulfolipids. Perhaps not surprisingly, both syntheses began with Sharpless asymmetric alkene oxidations as the ultimate source of asymmetry, testament to the reach of these oxidations into non-obvious areas and to the dearth of direct methods for asymmetric alkene chlorination.

The synthesis began with conversion of protected epoxy alcohol 50 to the enantioenriched dichloride 51 with the NCS/PPh3 reagent combination (Scheme 6). Removal of the pivaloyl group and oxidation yielded a fragile aldehyde which immediately underwent stereocontrolled allylation to afford anti-chlorohydrin 52. This successful addition to an α,β-dichloroaldehyde stands in contrast to our difficulties in effecting such transformations (and potentially similar problems alluded to by Carreira). Direct displacement of the alcohol in 52 with chloride was only realized with low efficiency after much experimentation. Conversion of chlorohydrin 52 to the corresponding epoxide followed by a second iteration of epoxide deoxydichlorination circumvented this problem, providing syn,syn-trichloride 53 in good yield over two steps. After much optimization, allylic oxidation afforded a 3 : 5 ratio of desired syn-diastereomer 54 to anti-isomer 55 in moderate yield. An oxidation–reduction sequence was used to correct the stereochemistry of the undesired isomer. An efficient alkene cross-metathesis provided E-alkene 56, which was dichlorinated using a reagent mixture similar to one prescribed by Markó48 for alkene dichlorinations to afford stereohexad 57; unfortunately, two other diastereomers were produced in significant quantities. Nonetheless, the enantioenriched stereohexad was produced in nine steps from epoxide 50, and could be converted into (+)-hexachlorosulfolipid (3) in six additional steps. Although less step-economical than the Carreira synthesis, this work highlighted the utility of the this group’s method for the stereospecific conversion of epoxides into dichlorides, which provides an excellent foundation to access chlorosulfolipids in enantioenriched form.

Scheme 6.

Enantioselective synthesis of hexachlorosulfolipid 3 by the Tanaka/Yoshimitsu group [DMP = Dess–Martin periodinane; Grubbs II = Grubbs’ 2nd-generation ruthenium alkylidene metathesis catalyst].

4 Conclusions and unanswered questions: Toxicity, membranes, conformation

The complete elucidation of the chlorosulfolipid structures and the ability to obtain reasonable quantities of material by synthesis (and in some cases from isolation) provide opportunities for a multitude of studies of these fascinating compounds. For example, the mechanism of toxicity of the mussel-derived lipids, the role of the freshwater algae-derived lipids in biological membranes, and the mechanism of biosynthetic chlorination are all poorly understood and warrant in-depth investigations. The preferred low-energy solution conformations of the chlorosulfolipids are more readily explained; however, the importance of their evolutionarily dictated molecular shape to their biological purpose remains unknown.

Carreira has pointed out that their synthesis of (±)-333 will enable biological and pharmacological studies of this mussel toxin, perhaps unveiling the role of this lipid in the organism of origin and shedding light on the basis of human toxicity. The recent isolation of this chlorosulfolipid from coral in the Taiwan Strait30 suggests a wide distribution of the producing organism (likely an alga), which renders more important the discovery of a means of detection and the understanding of the mechanism of toxicity.

The O. danica chlorosulfolipids, which appear to be important (yet unlikely) components of the organism’s membranes, might hold the key to a greater understanding of biological membrane design. It remains unclear how these water-soluble lipids with two sulfates located remote from each other along the lipid backbone can be the major components of a stable lipid bilayer. Identification of the mechanism of stabilization of chlorosulfolipid membranes will be a major step toward understanding the roles of these unusual lipids.

Several aspects of the biosynthesis of the chlorosulfolipids remain unknown. Certainly, the biosynthetic oxidation of the fatty acid precursors in freshwater algae that results in a C14-hydroxyl in the docosane series and a C15-hydroxyl in tetracosane series (except in malhamensilipin A, which is a C14-hydroxylated tetracosane), is most unusual. More compelling still is the mechanism of chlorination. The functionalization of unactivated sp3-carbon atoms suggests a radical mechanism, as proposed by Haines.13 This biosynthetic strategy for C–H activation might well be mechanistically distinct from other known biosynthetic oxidations, and the regio- and stereoselectivities are intriguing. It is also bewildering that the chlorination appears not to adhere to a specific order of events. The enzymology of these halogenation processes will no doubt prove to be fascinating, and several interesting questions can be posed at this time: (1) How many enzymes are involved in the introduction of the six chlorine atoms? (2) What is the nature of the molecular recognition between the sulfates – which are always proximal to the chlorination sites – and the responsible enzyme? (3) Are these enzymes promiscuous and might they also chlorinate other aliphatic sulfates (or phosphates)? The biosynthesis of chlorosulfolipids 4 and 5 (Fig. 1) remains even more mysterious. Again, the position of the sulfate along the tetracosane backbone does not match that in any of the other chlorosulfolipids, and level of functionalization (eleven chlorines!) is truly remarkable. The identification of the organism that originates these complex structures is the requisite first step toward learning about their biosynthesis.

The beautiful three-dimensional solution structures of the chlorosulfolipids (see Fig. 4b) attest to the chlorine substituents’ excellent ability to control conformation. Hoffmann’s wonderful investigations of polyketide solution conformations,49,50 which are of prime importance for their biological activities, are of great relevance; it is likely that the chlorosulfolipids were evolved with the placement and stereochemistry of the chlorides to control their three-dimensional shape, which must be of critical importance to their role in the organism. So, while the preferred solution conformations of the chlorosulfolipids are well-established and easily understood, the evolutionary purpose that drove their three-dimensional shape remains unknown.

After decades of relative neglect, the past few years of intense structural and synthetic studies targeting the chlorosulfolipids have made for a competitive area of research. Examples of unusual reactivity and remarkable selectivity have been encountered in synthetic efforts toward these targets. The ability to procure these compounds by synthesis marks only the beginning of a fascinating area of research aimed at a complete understanding of their origins and biological purposes. The chlorosulfolipids are indeed a most unusual phenomenon of evolution.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the NIH–NIGMS for funding of our chlorosulfolipid research program through grant #GM086483.

Biographies

D. Karl Bedke received his B.S. in Chemistry from Brigham Young University in 2006, where he worked with Professor Merritt B. Andrus on enantioselective phase-transfer catalyzed glycolate alkylations. Since then he has been at UC Irvine pursuing his Ph.D. with Professor Chris Vanderwal, developing syntheses of chlorosulfolipids.

D. Karl Bedke received his B.S. in Chemistry from Brigham Young University in 2006, where he worked with Professor Merritt B. Andrus on enantioselective phase-transfer catalyzed glycolate alkylations. Since then he has been at UC Irvine pursuing his Ph.D. with Professor Chris Vanderwal, developing syntheses of chlorosulfolipids.

Chris Vanderwal received B.Sc. (Biochemistry) and M.Sc. (Chemistry) degrees from the University of Ottawa. He earned his Ph.D. from the Scripps Research Institute in 2003 based on his work on FR182877, a covalent binder of tubulin, with Prof. Erik Sorensen. After postdoctoral work with Prof. Eric Jacobsen at Harvard, Chris joined UC Irvine in 2005, where he is currently an Assistant Professor of Chemistry. His group focuses on complex molecule synthesis, targeting polychlorinated natural products, alkaloids, and terpenes.

Chris Vanderwal received B.Sc. (Biochemistry) and M.Sc. (Chemistry) degrees from the University of Ottawa. He earned his Ph.D. from the Scripps Research Institute in 2003 based on his work on FR182877, a covalent binder of tubulin, with Prof. Erik Sorensen. After postdoctoral work with Prof. Eric Jacobsen at Harvard, Chris joined UC Irvine in 2005, where he is currently an Assistant Professor of Chemistry. His group focuses on complex molecule synthesis, targeting polychlorinated natural products, alkaloids, and terpenes.

Footnotes

In 2007, Darsow and coworkers reported the planar structure of a chlorosulfolipid from O. danica that was structurally completely dissimilar from those previously reported. The structure was proposed based on MS3 analysis of crude lipid extracts, and was not corroborated by any other spectroscopic methods. Further, the molecular mass and the isotope pattern reported are in complete agreement with those of danicalipin A. While we cannot conclusively rule out the proposed structure, it appears very unlikely on the basis of the known biogenesis of the O. danica lipids. See: K. H. Darsow, H. A. Lange, M. Resch, C. Walter, R. Buchholz, Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom., 2007, 21, 2188–2194.

We note that the structures of the O. danica polychlorinated tetracosane lipids have appeared only in review articles,8,9 and no characterization data is immediately available for them. However, the position of the C15 sulfate follows from mass spectrometric analysis,5 and appears unequivocal. It does not seem unlikely that the chlorination patterns in the docosane and tetracosane lipids would be the same.

The yields quoted in this scheme are based upon reported actual yields of product (not yields based on recovered starting material), and the 2% overall yield of 31 from 24 takes into account the isolated yield of diastereomerically pure intermediate epoxide (13%) found in the Supporting Information of ref. 33.

References

- 1.Haines TH, Block RJ. J Protozool. 1962;9:33–38. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mayers GL, Haines TH. Biochemistry. 1967;6:1665–1671. doi: 10.1021/bi00858a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayers GL, Pousada M, Haines TH. Biochemistry. 1969;8:2981–2986. doi: 10.1021/bi00835a045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haines TH, Pousada M, Stern B, Mayers GL. Biochem J. 1969;113:565–566. doi: 10.1042/bj1130565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elovson J, Vagelos PR. Proc Natl Acad Soc USA. 1969;62:957–963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.62.3.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elovson J, Vagelos PR. Biochemistry. 1970;9:3110–3126. doi: 10.1021/bi00818a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haines TH. Prog Chem Fats Lipids. 1971;11:297–345. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haines TH. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1973;27:403–412. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.27.100173.002155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haines TH. In: Lipids and Biomembranes of Eukaryotic Microorganisms. Erwin JA, editor. Academic Press; New York: 1973. pp. 197–232. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bedke DK, Shibuya GM, Pereira A, Gerwick WH, Haines TH, Vanderwal CD. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:7570–7572. doi: 10.1021/ja902138w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawahara T, Kumaki Y, Kamada T, Ishii T, Okino T. J Org Chem. 2009;74:6016–6024. doi: 10.1021/jo900860e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mooney CL, Mahoney EM, Pousada M, Haines TH. Biochemistry. 1972;11:4839–4844. doi: 10.1021/bi00775a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mooney CL, Haines TH. Biochemistry. 1973;12:4469–4472. doi: 10.1021/bi00746a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elovson J. Biochemistry. 1974;13:2105–2109. doi: 10.1021/bi00707a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mercer EI, Thomas G, Harrison JD. Phytochemistry. 1974;13:1297–1302. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas G, Mercer EI. Phytochemistry. 1974;13:797–805. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elovson J. Biochemistry. 1974;13:3483–3487. doi: 10.1021/bi00714a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaillancourt FH, Yin J, Walsh CT. Proc Natl Acad Soc USA. 2005;102:10111–10116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504412102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mercer EI, Davies CL. Phytochemistry. 1974;13:1607–1610. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mercer EI, Davies CL. Phytochemistry. 1975;14:1545–1548. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mercer EI, Davies CL. Phytochemistry. 1979;18:457–462. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen JL, Proteau PJ, Roberts MA, Gerwick WH, Slate DL, Lee RH. J Nat Prod. 1994;57:524–527. doi: 10.1021/np50106a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pereira AR, Byrum T, Shibuya GM, Vanderwal CD, Gerwick WH. J Nat Prod. 2010;73:279–283. doi: 10.1021/np900672h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bedke DK, Shibuya GM, Pereira AR, Gerwick WH, Vanderwal CD. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:2542–2543. doi: 10.1021/ja910809c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ciminiello P, Fattorusso E, Forino M, Di Rosa M, Ianaro A, Poletti R. J Org Chem. 2001;66:578–582. doi: 10.1021/jo001437s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ciminiello P, Dell’Aversano C, Fattorusso E, Forino M, Magno S, Di Rosa M, Ianaro A, Poletti R. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:13114–13120. doi: 10.1021/ja0207347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ciminiello P, Dell’Aversano C, Fattorusso E, Forino M, Magno S, Di Meglio P, Ianaro A, Poletti R. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:7093–7098. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsumori N, Kaneno D, Murata M, Nakamura H, Tachibana K. J Org Chem. 1999;64:866–876. doi: 10.1021/jo981810k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohtani I, Kusumi T, Kashman Y, Kakisawa H. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:4092–4096. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chao CH, Huang HC, Wang GH, Wen ZH, Wang WH, Chen IM, Sheu JH. Chem Pharm Bull. 2010;58:944–946. doi: 10.1248/cpb.58.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marquez BL, Gerwick WH, Williamson RT. Magn Res Chem. 2001;39:499–530. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nilewski C, Geisser RW, Ebert MO, Carreira EM. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:15866–15876. doi: 10.1021/ja906461h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nilewski C, Geisser RW, Carreira EM. Nature. 2009;457:573–577. doi: 10.1038/nature07734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolfe S. Acc Chem Res. 1972;5:102–111. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hunter L, O’Hagan D. Org Biomol Chem. 2008;6:2843–2848. doi: 10.1039/b809432b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown AE, Elovson J. Biochemistry. 1974;13:3476–3482. doi: 10.1021/bi00714a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen LL, Pousada M, Haines TH. J Biol Chem. 1976;251:1835–1842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen LL, Haines TH. J Biol Chem. 1976;251:1828–1834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shibuya GM, Kanady JS, Vanderwal CD. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12514–12518. doi: 10.1021/ja804167v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schlama T, Gabriel K, Gouverneur V, Mioskowski C. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1997;36:2342–2344. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Isaacs NS, Kirkpatrick D. Tetrahedron Lett. 1972;13:3869–3870. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshimitsu T, Fukumoto N, Tanaka T. J Org Chem. 2009;74:696–702. doi: 10.1021/jo802093d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cha JK, Christ WJ, Kishi Y. Tetrahedron. 1984;40:2247–2255. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Daviu N, Delgado A, Llebaria A. Synlett. 1999:1243–1244. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peterson PE, Indelicato JM, Bonazza BR. Tetrahedron Lett. 1971;12:13–16. and references therein. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fleming PR, Sharpless KB. J Org Chem. 1991;56:2869–2875. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoshimitsu T, Fujumoto N, Nakatani R, Kojima N, Tanaka T. J Org Chem. 2010;75:5425–5437. doi: 10.1021/jo100534d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Markó IE, Richardson PR, Bailey M, Maguire AR, Coughlan N. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:2339–2342. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoffmann RW. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 1992;31:1124–1134. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hoffmann RW. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2000;39:2054–2070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]