Abstract

The repair of incisional and ventral hernias by the laparoscopic method is finding its place in the general surgical field. The use of tacks and transfascial sutures is commonplace. A new hernia has been identified. Two hernias have been seen following the successful repair of incisional hernias. These did not appear to be recurrent hernias as definite findings of fascial defects were present related to the tack sites themselves. This raises the question that possibilities exist that more of these “tack” hernias may be identified in the future. More research and possibly other fixation devices may prevent this entity from becoming more prevalent.

Keywords: Incision, Tacks, Laparoscopy, Hernia

INTRODUCTION

The laparoscopic repair of incisional and ventral hernias has been established as an option for repairing these entities. The initial report1 of this operation used staples to fixate the mesh. During the evolution of this operation, the use of transfascial sutures has become the standard to secure the prosthetic biomaterial.2–6 These sutures are believed to provide secure fixation to the prosthetic mesh. The use of additional fixation devices provides the necessary approximation of the patch to the anterior abdominal wall so that tissue in-growth can occur. The sutures are generally placed 5 cm apart while the other devices, such as helical tacks, are placed 1-1.5 cm apart, both along the periphery of the prosthetic biomaterial.

Currently, the most popular device used in the approximation of the biomaterial edges is the Pro-Tack (U. S. Surgical/Tyco Corporation, Norwalk, CT), although others, such as the Salute (ONUX Medical, Inc., Hampton, NJ), have recently become available. The former device places a helical coil into the fascia and muscle of the anterior abdominal wall (Figure 1). The tack itself is 4 mm in length and 3 mm in width. This penetrates approximately 3 mm to 4 mm into these tissues. The latter (a reusable instrument) places a stainless steel coil, which is not preformed, into the muscle and fascia. This penetrates approximately 3 mm into the tissues.

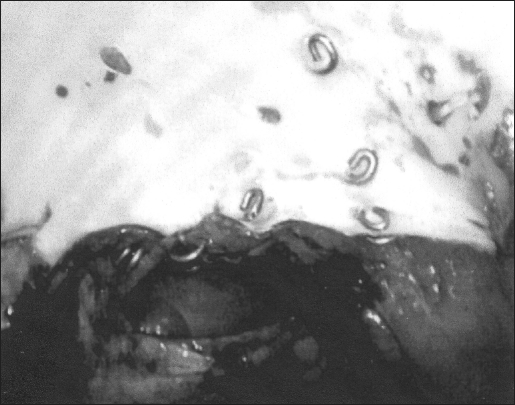

Figure 1.

Laparoscopic appearance of “tack” hernia in Case 2. Note the 2 intact transfascial sutures on either side of the defect.

I have encountered 2 patients who have developed hernias at the site of these tacks. This type of hernia has not been described and represents a new clinical entity. The surgeon must now recognize the possibility of this hernia being the cause of an apparent need for repeated repair.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Case 1

This 48-year-old male originally presented to another surgeon with a primary umbilical hernia. He was morbidly obese (BMI = 50.3). The fascial edges of the hernia defect were not felt preoperatively because of the incarcerated contents of the hernia. At that time, the surgeon performed a laparoscopic repair of the hernia. A review of the operative report revealed that the patient had 2 fascial defects that measured 2×2 cm each. A 10×15-cm DualMesh (W. L. Gore and Associates, Inc., Flagstaff, AZ) prosthesis was placed under the defect in the manner previously described.1 The patient was discharged on the day of surgery and had an uneventful postoperative course.

This patient presented to this author 6 months postoperatively with an obvious hernia at the superior aspect of the location of the patch. The apparent location of the hernia defect was easily delineated because the minute scars of the prior skin incisions that were used to place the transfascial sutures at the initial operation were easily seen. Despite this, however, it was not possible to identify the exact size or location of the hernia due to the large panniculus that was present (BMI=48). No preoperative testing was necessary to further delineate the hernia.

The patient was taken to the operative suite and underwent a laparoscopic examination. No adhesions were noted to the previously placed biomaterial. The hernia was located at the superior aspect of the previous repair. The hernia defect measured 3.5×3.5 cm and appeared to be located between two of the previously placed transfascial sutures. This hernia defect was repaired with a second DualMesh Plus patch that measured 10×15 cm. The patient is now 19 months postoperative and has had no evidence of recurrence.

Case 2

This 34-year-old male presented with a recurrent incisional hernia from a prior colectomy for Crohn's disease in June 1998. The original repair was sutured primarily with polypropylene sutures by another surgeon in January 1999. At the time of this presentation, the patient had a BMI of 26.5. I repaired this recurrent hernia laparoscopically in June of 2000. The hernia defect measured 7.5×12.5 cm. To effect the repair of this hernia, a 15×19-cm DualMesh Plus “corduroy” patch was fixed to the anterior abdominal wall with transfascial sutures placed along the periphery of the prosthesis at 5-cm intervals followed by helical tacks placed 1-1.5 cm apart. The patient was discharged the morning after surgery and had an uneventful postoperative course.

At the annual follow-up visit in June of 2001, the hernia repair was intact. He returned in January 2002 with a 1-month history of a painful bulge at the right superior aspect of the previous laparoscopic repair. The clinical examination of this patient appeared similar to that of the other patient discussed above. The hernia was felt to be located between two of the transfascial sutures and measured 4×4.3 cm in dimension. This hernia was not incarcerated; but because of his associated pain, the patient was taken to surgery the next day.

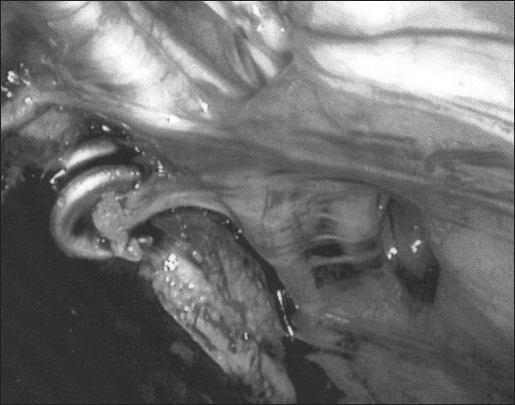

At laparoscopy, it was found that a neomesothelium covered the visceral surface of the prosthetic biomaterial. A few omental adhesions were adherent to this membrane. This surface covering was entered to easily expose the patch. At the site of the hernia, several tacks were not secure within the hernia defect itself. This was clearly between two of the transfascial sutures. The transfascial sutures were intact and were not involved as part of the defect (Figure 1). Additionally, inspection of the contralateral side of the prosthetic biomaterial revealed fascial defects that were adjacent to tacks. These are felt to represent small hernias (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Laparoscopic appearance of the side opposite of the presenting hernia. The fascial defects at the site of the tacks are easily apparent.

The prosthetic biomaterial was fully incorporated into the anterior abdominal wall and had not pulled away. The previous hernia repair was intact, as the prior hernia was not exposed. These hernias were, therefore, new and unrelated to the prior fascial defect. The current defect had an actual intraoperative measurement of 2.5× 4.3cm.

The hernia repair was performed with a 15×19 cmDualMesh Plus “corduroy” patch placed transversely across all of these defects to provide complete coverage of these “tack” hernias. The tacks used in this repair were staggered along the edge of the patch while the transfascial sutures were applied in the usual manner. However, instead of the recommended minimum of 1-cm spacing between the suture punctures to place the transfascial sutures, I spaced these at a minimum of 2 cm apart. The patient had an uneventful recovery. He is nearly 9 months postoperative and is without any complaints.

DISCUSSION

Laparoscopic repair of incisional and ventral hernias is evolving into the armamentarium of many surgeons. The increased use of this technique may identify unusual or unexpected outcomes. One of these has been identified in these 2 patients. I have used this technique with various modifications since 1991. Currently, like most surgeons, I use transfascial permanent sutures to fixate the mesh securely. The placement of additional tacks along the periphery of the prosthesis serves to approximate the patch so that in-growth of tissue can occur and prevent the potential migration of bowel between the sutures. Since the helical tacks became available, I have used them extensively to perform this function, without apparent complications. The technique that was used for the repair in these patients has been described previously.8

This discovery of fascial disruption by these devices, resulting in herniation is a completely new finding. This could be problematic to those surgeons in various parts of the world who do not place transfascial sutures and rely solely upon these tacks for fixation. Conceivably, several of these “failures” may be noted in the future. Conversely, it is also possible that some of the recurrent hernias that have been reported in the literature may have, in fact, been the result of the development of these tack hernias. It is believed that once these hernias have enlarged significantly, it may be quite difficult to identify the cause with absolute certainty.

The consideration of the cause of these hernias is problematic. I do not feel that these tacks were placed improperly as I have used these devices for many years. In fact, if they were placed improperly, it is more likely that they would not have had significant penetration of the fascia that could have resulted in these defects. Potentially, “shrinkage” of the biomaterial could have pulled these tacks out of the fascia. While this idea has appeal, it is widely known that meshes do not actually shrink. The normal healing processes result in scar contraction such that the final size of any prosthetic biomaterial will be smaller once this has occurred. Additionally, the prior fascial defect was completely covered by the prior prosthesis.

One could postulate that the level of in-growth of the patch was insufficient. This was not found at the time of surgery. The prosthetic biomaterial of both of these patients was firmly attached to the anterior abdominal wall. Additionally, if this had been the problem, one would assume that these hernias would have become manifest within a few weeks or months. Experimentally, the fixation of this product is quite rapid even at 3 days.9

Another consideration may be that these hernia defects were the result of a tearing force exerted by the transfascial sutures used to secure the prostheses. This was not evident in either patient, however. As evidenced in Figure 1, the hernia defect is seen between the sutures rather than at the site of the suture. This was quite distinct at the time of the operation. There, also, can be little question that the fascial defects that lie adjacent to the tacks in Figure 2 can only be the result of the tacks themselves as no suture was near the site of these defects.

I believe that these tacks were dislodged early postoperatively, most likely in the first 30 to 60 days. The hernias did not become manifest until such time that the fascial defects enlarged enough to become obvious to the patients. Conceivably, other hernia recurrences that have been reported in other published reports may have developed similarly. If such hernias are identified after many months or years, it would be anticipated that the enlargement of the hernia would make as accurate an assessment as was accomplished in these 2 individuals very unlikely.

The commonalities of these individuals are that they were both not elderly and both were overweight. Neither patient smoked tobacco. No other distinguishing characteristics were present in either patient. Therefore, no obvious predisposing factors are felt to be responsible for these hernias except that the increased intraabdominal pressures may have played a role. Additionally, a collagen abnormality could be postulated.

Since I have discovered these hernias, I have modified my approach to laparoscopic ventral hernia repair somewhat. I now stagger the tacks along the edge of the patch no more than 1 cm apart between the sutures in an effort to disperse the effects of the intraabdominal pressure (Figure 3). Possibly this spacing will prevent the extraction of these most peripheral tacks by the inner row of tacks. I also use a larger interval of puncture sites of the patch to place the transfascial sutures. Prior to this, a minimum of 1 cm of distance between these was felt to be adequate, but currently I believe that a space of at least 1.5-2 cm between these puncture sites is necessary; this also is done to disperse the forces more to the sutures than the tacks themselves. At present, I use the Salute construct to fixate the prosthesis between the sutures. These appear to be somewhat “less aggressive” than the helical tacks, which may lessen the tendency of the device to extract itself from the fascia. We have demonstrated the effectiveness of this device in the labarotory.9 Thus far, these modifications appear to be effective, but longer follow-up of these and all of our patients is needed.

Figure 3.

The “staggered“ placement of the tacks at the periphery of the DualMesh Plus prosthesis.

CONCLUSION

A new entity of hernia has been discovered. The “tack” hernia may become more recognized in the future now that this has been described. Modification of the current method of laparoscopic incisional and ventral hernioplasty may diminish the occurrence of this problem in the future.

References:

- 1. LeBlanc KA, Booth WV. Laparoscopic repair of incisional abdominal hernias using expanded polytetrafluroethylene: preliminary findings. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1993;3(1):39–41 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. LeBlanc KA, Booth WV, Bellanger DE, Whitaker JM. Laparoscopic incisional and ventral herniorraphy: our initial 100 patients. Hernia. 2001;5:41–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Park A, Birch DW, Lovrics P. Laparoscopic and open incisional hernia repair: a comparison study. Surgery. 1998;124(4):816–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ramshaw BJ, Escartia P, Schwab J, Mason EM, Wilson RA, Duncan TD, et al. Comparison of laparoscopic and open ventral herniorraphy. American Surgeon. 1999;65:827–832 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Park A, Heniford T, LeBlanc KA, Voeller G. Laparoscopic repair of incisional hernias: patient selection and preop evaluation. Contemp Surg. 2001;57(4):171–182 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Park A, Heniford T, LeBlanc KA, Voeller G. Laparoscopic repair of incisional hernias: surgical technique. Contemp Surg. 2001;57(5):225–238 [Google Scholar]

- 7. LeBlanc KA. Current considerations in laparoscopic incisional and ventral herniorraphy. JSLS. 2000;4:131–139 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. LeBlanc KA, Bellanger DE, Rhynes KV, Baker DG, Stout RW. Tissue attachment strength of prosthetic meshes used in ventral and incisional hernia repair: a study in the New Zealand white rabbit adhesion model. Surg Endosc. In press [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9. LeBlanc KA, Stout RW, Kearney MT, Paulson DB. Comparison of adhesion formation associated with Pro-Tack (US Surgical) versus a new mesh fixation device, Salute (ONUX Medical). Surg Endosc. In press [DOI] [PubMed]