Introduction

A thorough pre-operative evaluation is fundamental for stratifying haemorrhagic risk, for predicting transfusion needs in relation to the type of surgical intervention, as well as for evaluating the indications and eligibility of a patient for autotransfusion procedures, and the need for any adjuvant therapies (Grade of recommendation: 2C)1–3.

The pre-operative assessment must include a careful review of the patient’s clinical documentation, a thorough personal and family history, focused particularly on revealing a suspected bleeding disorder, as well as a control of the laboratory tests.

The evaluation must be carried out a reasonable time before the planned date of the intervention, for example 30 days before, in order to allow detailed diagnostic investigations or planning of appropriate therapeutic measures (Grade of recommendation: 2C)4.

Evaluation of haemorrhagic risk

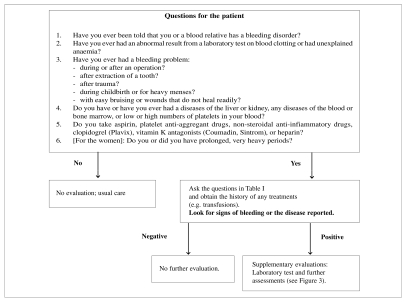

A detailed personal and family history of any bleeding episodes must be taken from all patients who are candidates for surgery or invasive procedures (Figures 1–3, Table I) (Grade of recommendation: 2C)5–10.

Figure 1.

Initial evaluation of bleeding disorders35.

Figure 3.

Laboratory assessment for von Willebrand’s disease or other bleeding disorders36.

Table I.

Bleeding score12.

| Patient’s ID_________________ sex_____ date of birth_____________ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epistaxis | Bleeding from minor wounds | Oral cavity | |||

| 0 | None or rare (<5 episodes) | 0 | None or mild (<5 episodes) | 0 | No |

| 1 | >5 episodes or >10 min/episode | 1 | >5 episodes or >5 min/episode | 1 | Reported at least 1 episode |

| 2 | Only medical consultation | 2 | Only medical consultation | 2 | Only medical consultation |

| 3 | Packing or cauterisation or antifibrinolytic | 3 | Surgical haemostasis | 3 | Surgical haemostasis or antifibrinolytic |

| 4 | Transfusion or replacement therapy or DDAVP | 4 | Transfusion or replacement therapy or DDAVP | 4 | Transfusion or replacement therapy or DDAVP |

| Menorrhagia | Muscle haematomas | Joint bleeds | |||

| 0 | No | 0 | None | 0 | None |

| 1 | Only medical consultation | 1 | After trauma, no treatment | 1 | After trauma, no treatment |

| 2 | Antifibrinolytic and OC | 2 | Spontaneous, no treatment | 2 | Spontaneous, no treatment |

| 3 | DDAVP or replacement therapy or iron treatment | 3 | Spontaneous or traumatic, requiring treatment | 3 | Spontaneous or traumatic, requiring treatment |

| 4 | Transfusion or replacement therapy or DDAVP or hysterectomy | 4 | Spontaneous or traumatic, requiring surgery or transfusions | 4 | Spontaneous or traumatic, requiring surgery or transfusions |

| Dental extractions | Surgery | Post-partum bleeding | |||

| – 1 | No bleeding after ≥2 extractions | – 1 | No haemorrhage in ≥2 operations | – 1 | No haemorrhage in ≥2 deliveries |

| 0 | No extractions or no bleeding after 1 extraction | 0 | No surgery or no haemorrhage in = 1 operation | 0 | No deliveries or no haemorrhage after 1 delivery |

| 1 | Reported in <25% of all procedures | 1 | Reported in <25% of all operations | 1 | Only medical consultation |

| 2 | Reported in >25% of all procedures, no intervention | 2 | Reported in >25% of all operations | 2 | DDAVP or replacement therapy or iron treatment or antifibrinolytic |

| 3 | Re-suturing or packing | 3 | Surgical haemostasis or antifibrinolytic | 3 | Transfusion or replacement therapy or DDAVP |

| 4 | Transfusion or replacement therapy or DDAVP | 4 | Transfusion or replacement therapy or DDAVP | 4 | Hysterectomy |

| Skin Gastrointestinal bleeding | CNS bleeding | ||||

| 0 | None or mild (<1 cm) | 0 | None | 0 | None |

| 1 | >1 cm and without trauma | 1 | Associated with ulcer, portal hypertension, haemorrhoids, angiodysplasia | 1 | - |

| 2 | Only medical consultation | 2 | Spontaneous | 2 | - |

| 3 | - | 3 | Surgical haemostasis or transfusion or replacement therapy or DDAVP or antifibrinolytic | 3 | Subdural, any intervention |

| 4 | - | 4 | - | 4 | Intracerebral, any intervention |

| Total score:___________ (attention if >0) | |||||

Legend: DDAVP = desmopressin; ID = identity code; CNS = central nervous system; OC = oral contraceptive.

A well-conducted clinical interview should elicit information on any spontaneous, post-traumatic or post-surgical bleeding, any use of anticoagulant and anti-aggregant drugs (Grade of recommendation: 2C)2 and include the family history (Grade of recommendation: 2C)2,11.

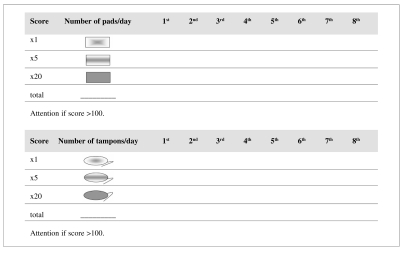

For those patients with a positive history of bleeding, it may be helpful to use a structured questionnaire12, such as the one shown in Table I13, and a scheme to evaluate menorrhagia (Figure 2) in order to quantify the haemorrhagic risk (Grade of recommendation: 2C)14,15.

Figure 2.

Evaluation of menorrhagia14.

Indiscriminate screening of coagulation parameters in unselected patients who are candidates for surgery or invasive procedures, in the absence of a history suggestive of bleeding, cannot be recommended (Grade of recommendation: 2C+)2,16,17. In the presence of a history of bleeding or a clear indication (for example, liver disease) further diagnostic laboratory tests are necessary; these should be guided by clinical findings and the history and clinical features of the patient (Grade of recommendation: 2C)2. A platelet count is, however, advisable before surgery and invasive procedures (excluding diagnostic endoscopies) (Grade of recommendation: 2C)18.

The contemporaneous presence of anaemia and thrombocytopenia increases haemorrhagic risk19–31. In anaemic and thrombocytopenic patients (platelet count ≤20x109/L) who are candidates for surgery or invasive procedures, the haemorrhagic risk can be reduced by increasing the haematocrit to around 30% (besides correcting the platelet count to levels appropriate for the management of the procedure to be carried out) (Grade of recommendation: 1C+)19–31.

Laboratory tests

The laboratory tests commonly used to evaluate haemorrhagic risk are the prothrombin time (PT)32, which explores the extrinsic and common coagulation cascades, the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), which explores the intrinsic and common coagulation cascades, and the platelet count. Both the PT and the aPTT can be altered in various situations, which may lead to a physiological response being masked. For example, the levels of factor VIII (FVIII) increase during pregnancy and in response to stress and inflammatory states.

This causes a shortening in the aPTT, which can mask a mild form of haemophilia or von Willebrand’s disease. Contrariwise, lengthening of the aPTT due to the presence of a lupus inhibitor is not associated with an increased risk of bleeding.

Further examinations are assays of fibrinogen and the clotting factors [von Willebrand factor (vWF), factor II, factor V, factor VII, FVIII, factor IX, factor X, and factor XI], the bleeding time, and platelet function tests33,34. The utility of the bleeding time, even when standardised, is limited by the poor sensitivity and specificity of this test2.

Figure 3 is a flow diagram illustrating the procedures to adopt for the initial evaluation and investigation of coagulation status (Grade of recommendation: 2C)35–37.

A lack of factor XII does not increase haemorrhagic risk, while, in selected cases in which no laboratory anomalies are apparent but there is a history of significant bleeding, it is suggested that platelet function is evaluated and factor XIII assayed (Grade of recommendation: 2C)38,39.

Treatment of defects of haemostasis

In the case of a clotting defect, replacement therapy with the deficient factor should be instituted (Grade of recommendation: 1A)40–44. Table II lists the inherited bleeding disorders, the haemostatic levels of the deficient factors and the mean dose of the specific factor or plasma necessary for the replacement therapy41.

Table II.

Treatment of congenital bleeding disorders based on the plasma levels of the deficient factor in the context of surgery41.

| Deficient factor | Haemostatic plasma levels (IU/dL) | Factor half-life (hours) | Dose of specific concentrate (IU/kg) | PCC (IU/kg) | Dose of plasma (mL/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fibrinogen | 30–50 mg/dL | 72 | 20–30 mg/kg | - | 15–20 |

| Prothrombin | 20–30 | 72 | - | 20–30 | 15–20 |

| Factor V | 10–15 | 36 | - | - | 15–20 |

| Factor VII | 10–15 | 4–6 | 30–40 | - | - |

| Factor VIII | 50–100 | 8–12 | 50–100 | - | - |

| Factor IX | 50–100 | 20–24 | 50–100 | - | - |

| Factor X | 10–15 | 40 | - | 20–30 | 15–20 |

| Factor XI | 5–10 | 60 | 15–20 | - | 15–20 |

Legend: PCC=prothrombin complex concentrate.

In type I von Willebrand’s disease, the drug of first choice for patients with vWF levels of 10 IU/dL or higher is desmopressin (DDAVP) (Grade of recommendation: 2B)42. vWF/FVIII concentrates are indicated for patients who do not respond to DDAVP (patients with severe type 1, types 2 and type 3 von Willebrand’s disease) (Grade of recommendation: 2B)42.

vWF concentrates without FVIII can be an alternative to vWF/FVIII concentrates as prophylaxis against bleeding in elective surgery (Grade of recommendation: 2C)42,45.

Thrombocytopenia

The suggested prophylaxis in the case of thrombocytopenia is as follows19:

- major surgery or invasive procedures such as lumbar puncture, epidural anaesthesia, liver biopsy, endoscopy with biopsy, placement of a central venous catheter: bring the platelet count to above 50x109/L (Grade of recommendation: 2C+)46–51;

- operations to critical sites, eye surgery and neurosurgery: administer prophylactic transfusions if the platelet count falls below the threshold of 100x109/L (Grade of recommendation: 2C)19,46–49;

- in patients with acute disseminated intravascular coagulation, in the absence of bleeding: reserve prophylactic platelet transfusions for those cases in which the thrombocytopenia and stratification of haemorrhagic risk indicate a high probability of bleeding (Grade of recommendation: 2C)52.

With regards to the treatment of thrombocytopenia:

- the surgical patient who is bleeding usually requires a platelet transfusion if his or her platelet count is below 50x109/L and rarely requires such a transfusion if the platelet count is above 100x109/L (Grade of recommendation: 2C)19,46–48,53;

- during massive transfusions, when the volume of red cell concentrate transfused is approximately double that of the circulating blood volume, a platelet count of 50x109/L can be expected; a transfusion threshold of 75x109/L is, therefore, suggested in those patients with active bleeding, in order to guarantee them a margin of safety and prevent the platelet count from dropping below 50x109/L, the critical threshold for haemostasis. A higher platelet count has been recommended for patients with multiple trauma resulting from high velocity accidents or with lesions involving the central nervous system (Grade of recommendation: 2C)19,54;

- in acute disseminated intravascular coagulation, in the presence of considerable bleeding and thrombocytopenia, besides treatment of the underlying disease and restoration of normal levels of clotting factors, the platelet count must be monitored and coagulation screening tests performed (PT, aPTT, fibrinogen, antithrombin, D-dimer). There is not a consensus on the target platelet count, but in the presence of substantial bleeding, it could be reasonable to maintain the platelet count around 50x109/L (Grade of recommendation: 2C)19,52,55.

Platelet disorders

Platelet transfusions are indicated, independently of the platelet count, for the prophylaxis of haemorrhage in patients with platelet function defects (congenital or acquired) at high risk of bleeding who must undergo surgery or an invasive procedure at high haemorrhagic risk, as well in the presence of peri-operative haemorrhage (Grade of recommendation: 2C)19,50.

Recombinant activated factor VII

The main indications for the use of recombinant activated factor VII (rFVIIa) are peri-operative prophylaxis and the treatment of bleeding in patients with haemophilia A or B with inhibitors, in whom replacement treatment with the deficient factor is not possible or not indicated (Grade of recommendation: 2C)56,57 and in patients with acquired haemophilia (Grade of recommendation: 2C+)57, inherited FVII deficiency (Grade of recommendation: 2C+)41,58,59, or Glanzmann’s thromboasthenia associated with refractoriness to platelet transfusion (Grade of recommendation: 2C)19,46,60.

In recent years there has been a notable increase in the use of rFVIIa for “off label” indications such as the treatment of haemorrhage due to secondary coagulopathies in patients undergoing surgery or in those with multiple trauma61, despite uncertainty about the risk of thrombotic complications associated with the use of this drug for unregistered indications62,63.

The use of rFVIIa, mainly in the setting of uncontrolled studies, has also been the subject of recommendations, based on the consensus of experts, for the treatment of massive haemorrhage in surgical, obstetric and gynaecological patients64–66. A recent Cochrane systematic review recommended using rFVII only in clinical trials, since its true efficacy as a haemostatic drug, both for prophylaxis and for the treatment of major bleeding, is still uncertain67. However, reports of adverse arterial thromboembolic events have recently led the European Medicines Agency (EMEA) to contraindicate the use of rFVIIa for purposes other than the approved indications68,69.

Desmopressin

According to a review from the Cochrane Library70, the use of DDAVP limits blood losses in the peri-operative period, but not to a clinically important extent, and does not significantly reduce the transfusion of red cell concentrates. The authors, therefore, concluded that there is not currently evidence to support the use of DDAVP to contain peri-operative blood losses and transfusion requirements in patients who do not have inherited bleeding disorders (Grade of recommendation: 1C)70–73.

Antithrombin deficiency

Replacement therapy with antithrombin (AT) is almost exclusively indicated for patients with congenital AT deficiency in particular situations characterised by an imbalance in haemostasis towards thrombosis (Grade of recommendation: 2C)74–76.

There is no clinical evidence that above normal levels of AT guarantee better protection than physiological levels75,77,78.

A recent meta-analysis77,78 on the use of AT in critically ill patients did not demonstrate any significant effect on the reduction of mortality either globally or in the subgroups of studies carried out in obstetric patients or in those with trauma; however, an increase in haemorrhagic risk was revealed75,77,78.

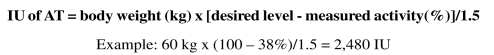

Calculation of the dose of antithrombin to administer

Before giving replacement therapy with the specific concentrate, it is advisable to assay AT function (Grade of recommendation: 2C)75.

Given that a dose of 1 IU/kg of body weight increases plasma AT activity by 1.5%, the dose to administer can be calculated as follows:

|

The dose and timing of subsequent administrations are based on the results of monitoring the plasma activity of AT every 12–48 hours.

Side effects and adverse reactions

AT infusions are generally well tolerated although allergic reactions are possible75.

The use of AT concentrates contemporaneously with the administration of heparin increases the risk of bleeding and for this reason careful clinical and laboratory controls are necessary in this situation (Grade of recommendation: 2C)75.

Evaluation of concurrent therapy Antiplatelet drugs

The patient’s drug history must be taken, aimed at determining any use of anti-aggregant therapies (Grade of recommendation: 1C+)79.

Besides the strictly anti-aggregant drugs (aspirin, clopidogrel, dipyridamole, ticlopidine, abciximab), which inhibit platelet function with different mechanisms, effectiveness and duration80–82, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs also have an antiplatelet effect through the inhibition of cyclo-oxygenase (COX 1)45,83.

The anti-aggregant drugs and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have an irreversible effect and do not have antidotes, so their use must be suspended some days before a planned intervention (Grade of recommendation: 2C)17,45,84–87.

Oral anticoagulants

As for the antiplatelet drugs, oral anticoagulant therapy (warfarin, acenocoumarol) must be suspended at least 4 days before surgery to allow the PT and International Normalised Ratio to return to the norm (Grade of recommendation: 2C)88.

In preparation for surgery that cannot be deferred, patients receiving vitamin K antagonists must be treated with prothrombin complex concentrates, which are the first choice of treatment, or, if these are not available, with fresh-frozen plasma, in order to normalise the parameters of coagulation (Grade of recommendation: 1C+)19,75,89–94.

Heparin and thrombolytic drugs

Low-dose (prophylactic) unfractionated heparin (UFH) seems to be associated with a low risk of haemorrhage during anaesthesia and surgery95. Nevertheless, in patients receiving treatment with heparin, spinal anaesthesia and neurosurgical interventions should be avoided for at least 6 hours after suspension of the last dose of UFH and for at least 12 hours after treatment with low molecular weight heparins (LMWH), since the activity of these drugs peaks 4 hours after injection and lasts for 24 hours.

Patients receiving therapeutic doses of heparin have high intra- and post-operative risks of bleeding, so UFH and LMWH should be suspended for 6 and 12 hours, respectively (Grade of recommendation: 2C+)95.

In emergency situations, the anticoagulant effect of heparin can be antagonised by protamine sulphate (Grade of recommendation: 2C+)95.

When necessary, heparin administration can be restarted approximately 12 hours after completion of the intervention (Grade of recommendation: 2C+)96–98.

Surgical procedures should, generally, be postponed in patients receiving thrombolytic drugs, even though these have a short half-life (Grade of recommendation: 2C)96–98.

The effects of herbal remedies

Herbal remedies are very widely used in the population as supplementary or alternative therapies3,99–102. The use of such remedies is often not reported, since they are considered dietary integrators; however, many of them can affect coagulation and should, therefore, be suspended before an operation, at different times prior to the intervention depending on their duration of action (Grade of recommendation: 2C )103,104.

Garlic potentiates the effect of warfarin and has antiplatelet properties, so it is advisable to suspend its assumption 7 days before a planned intervention (Grade of recommendation: 2C)105. Ginko biloba has an antiplatelet effect, and it has been suggested that this should be suspended 36 hours before an intervention (Grade of recommendation: 2C)105. The antiplatelet effect of ginseng is irreversible, so this product should be suspended for 7 days (Grade of recommendation: 2C)105.

Other herbal remedies with antiplatelet effects are blueberries, bromelain, flaxseed oil, ginger and grape seed extract104. St. John’s wort and green tea, in contrast, accelerate the metabolism of warfarin, reducing its effect.

Evaluation of haemoglobin

The level of haemoglobin, related to other conditions that cause organ ischaemia, such as cardiorespiratory disorders, influences the threshold for transfusion of red blood cells106,107.

Patients with low levels of haemoglobin (<130 g/L in men and <120 g/L in women) have a higher risk of requiring allogeneic transfusion; to minimise this possibility, pharmacological measures should be used to correct their red cell mass before an operation (Grade of recommendation: 2C)1,4.

A simple strategy for sparing a patient’s blood is to limit the frequency of laboratory controls, the volume of blood sampled and the number of tests requested (Grade of recommendation: 2C)108.

Since blood transfusion is associated with an increase in morbidity and mortality in all surgical patients, a considerable amount of research has been carried out on how to limit or eliminate the use of allogeneic transfusions63,109,110.

Anaemia is a common finding in patients who are candidates for elective surgery111,112.

The relationship between erythropoiesis, erythropoietin and iron, studied in patients undergoing pre-operative autologous blood donation, shows the bone marrow response to post-haemorrhagic anaemia113. In response to the collection of one unit of blood a week, under the standard conditions of an autologous donation regimen, endogenous erythropoietin stimulates the production of 397–568 mL of red blood cells, equivalent to 2–3 units of whole blood. Exogenous erythropoietin treatment in patients pre-depositing autologous blood produces from 358 to 1102 mL of red blood cells, equivalent to 2–5 units of whole blood33,114.

The response to treatment with exogenous erythropoietin115 in patients with an adequate iron store is independent of the iron supply, as demonstrated in a cohort of patients with haemochromatosis, who did not have a greater response than that of controls116. It is, however, difficult for the iron supply to be increased in healthy subjects to the level necessary to support a rate of erythropoiesis of this degree, whereas this can be achieved in situations such as haemochromatosis or intravenous administration of iron117.

There is a good correlation between the dose of erythropoietin and red blood cell production118, which can be estimated to be four times higher than the basal levels, independently of sex and age119.

In patients with substantial iron deficiency, oral iron assumption is not sufficient to correct the induced dyserythropoiesis and intravenous iron administration should be considered (Grade of recommendation: 1C+)117,120–123.

The so-called “iron-limited” erythropoiesis, which occurs during treatment with erythropoietin, should also be corrected by the intravenous administration of iron (Grade of recommendation: 1C+)116,117.

Numerous, well-designed studies have examined the risks and adverse events related to the use of intravenous iron, particularly allergic and vasomotor reactions, which are independent of the dose and occur in about 5% of the patients: 0.7% of these reactions can be life-threatening123–125. Iron gluconate and iron sucrose have a better safety profile than iron dextran123–128. The rate of adverse events, in particular allergic reactions, appears to be lower with iron gluconate (the only preparation for intravenous administration available in Italy) than with iron dextran (3.3 and 8.7 episodes per million doses, respectively)33.

References

- 1.Goodnough LT, Shander A. Blood management. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:695–701. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-695-BM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chee YL, Crawford JC, Watson HG, Greaves M. Guidelines on the assessment of bleeding risk prior to surgery or invasive procedures. Br J Haematol. 2008;140:496–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Perioperative Blood Transfusion and Adjuvant Therapies. Practice guidelines for perioperative blood transfusion and adjuvant therapies: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Perioperative Blood Transfusion and Adjuvant Therapies. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:198–208. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200607000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodnough LT, Shander A, Spivak JL, et al. Detection, evaluation, and management of anemia in the elective surgical patient. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:1858–61. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000184124.29397.EB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koh MBC, Beverley J. The management of perioperative bleeding. Blood Rev. 2003;17:179–85. doi: 10.1016/s0268-960x(02)00062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dean JA, Blanchette VS, Carcao MD, et al. von Willebrand disease in a pediatric-based population: comparison of type 1 diagnostic criteria and use of the PFA-100® and a von Willebrand factor/collagen binding assay. Thromb Haemost. 2000;3:401–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferraris VA, Ferraris SP, Saha SP, et al. Perioperative blood transfusion and blood conservation in cardiac surgery: the Society of Thoracic Surgeons and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83 :S27–86. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.02.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drews CD, Dilley AB, Lally C, et al. Screening question to identify women with von Willebrand Disease. J Am Med Women Assoc. 2002;57:217–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laffan M, Brown SA, Collins PW, et al. The diagnosis of von Willebrand disease: a guideline from the UK Haemophilia Centre Doctors’ Organization. Haemophilia. 2004;10:199–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2004.00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JW. Von Willebrand disease, hemophilia A and hemophilia B, and other factor deficiencies. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2004;42:59–76. doi: 10.1097/00004311-200404230-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zahreddine I, Atassi K, Fuhrman C, et al. Impact of prior biological assessment of coagulation on the hemorrhagic risk of fiberoptic bronchoscopy. Rev Mal Respir. 2003;20:341–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tosetto A, Rodeghiero F, Castaman G, et al. A quantitative analysis of bleeding symptoms in type 1 von Willebrand disease: results from a multicenter European study (MCMDM-1 VWD) J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:766–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodeghiero F, Castaman G, Tosetto A, et al. The discriminant power of bleeding history for the diagnosis of von Willebrand disease type 1: an international, multicenter study. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:2619–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higham JM, O’Brien PM, Shav RW. Assessment of menstrual blood loss using a pictorial chart. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1990;97:734–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1990.tb16249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.James AH, Kouides PA, Abdul-Kadir R, et al. Von Willebrand disease and other bleeding disorders in women: consensus on diagnosis and management from an international expert panel. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201:12.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asaf T, Reuveni H, Yermiahu T, et al. The need for routine pre-operative coagulation screening tests (prothrombin time PT/partial thromboplastin time PTT) for healthy children undergoing elective tonsillectomy and/or adenoidectomy. Int J Ped Otor. 2001;61 :217–22. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(01)00574-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Segal JB, Dzik WH. Transfusion Medicine/Hemostasis Clinical Trials Network. Paucity of studies to support that abnormal coagulation test results predict bleeding in the setting of invasive procedures: an evidence-based review. Transfusion. 2005;45:1413–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.00546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Società Italiana per lo Studio dell’Emostasi e della Trombosi (SISET) Valutazione del rischio emorragico in pazienti sottoposti ad interventi chirurgici o procedure invasive. SISET; 2007. [Last accessed: 25/03/2010]. Available at: http://www.siset.org/lineeguida/LG3.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liumbruno G, Bennardello F, Lattanzio A, et al. Recommendations for the transfusion of plasma and platelets. Blood Transfus. 2009;7:132–50. doi: 10.2450/2009.0005-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schiffer AC, Anderson KC, Bennet CL, et al. Platelet transfusion for patients with cancer: clinical practice guidelines of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1519–38. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.5.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Livio M, Gotti E, Marchesi D, et al. Uraemic bleeding: role of anaemia and beneficial effect of red cell transfusions. Lancet. 1982;2:1013–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)90050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Small M, Lowe GD, Cameron E, Forbes CD. Contribution of the haematocrit to the bleeding time. Haemostasis. 1983;13:379–84. doi: 10.1159/000214826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernandez F, Goudable C, Sie P, et al. Low haematocrit and prolonged bleeding time in uraemic patients: effect of red cell transfusions. Br J Haematol. 1985;59:139–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1985.tb02974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Escolar G, Garrido M, Mazzara R, et al. Experimental basis for the use of red cell transfusion in the management of anemic-thrombocytopenic patients. Transfusion. 1988;28:406–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1988.28588337325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burns ER, Lawrence C. Bleeding time. A guide to its diagnostic and clinical utility. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1989;113:1219–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ho CH. The hemostatic effect of adequate red cell transfusion in patients with anemia and thrombocytopenia. Transfusion. 1996;36:290. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1996.36396182154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crowley JP, Metzger JB, Valeri CR. The volume of blood shed during the bleeding time correlates with the peripheral venous hematocrit. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997;108:579–84. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/108.5.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valeri CR, Cassidy G, Pivacek LE, et al. Anemia-induced increase in the bleeding time: implications for treatment of nonsurgical blood loss. Transfusion. 2001;41:977–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2001.41080977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eugster M, Reinhart WH. The influence of the hematocrit on primary haemostasis in vitro. Thromb Haemost. 2005;94:1213–8. doi: 10.1160/TH05-06-0424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Webert KE, Cook RJ, Sigouin CS, et al. The risk of bleeding in thrombocytopenic patients with acute myeloid leukaemia. Haematologica. 2006;41:1530–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Webert KE, Cook RJ, Couban S, et al. A multicenter pilot-randomized controlled trial of the feasibility of an augmented red blood cell transfusion strategy for patients treated with induction chemotherapy for acute leukemia or stem cell transplantation. Transfusion. 2008;48:81–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Samama CM, Ozier Y. Near-patient testing of haemostasis in the operating theatre: an approach to appropriate use of blood in surgery. Vox Sang. 2003;84 :251–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1423-0410.2003.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waters JH. A Physician’s Handbook. 1st ed. Bethesda, MD: AABB; 2006. Perioperative Blood Management. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Federici AB, Castaman G, Thompson A, et al. Von Willebrand disease: clinical management. Haemophilia. 2006;12 (Suppl 3):152–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2006.01273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nichols WL, Hultin MB, James AH, et al. von Willebrand disease (vWD): evidence-based diagnosis and management guidelines, the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Expert Panel report (USA) Haemophilia. 2008;14:171–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2007.01643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nichols WL, Rick ME, Ortel TL, et al. Clinical and laboratory diagnosis of von Willebrand disease: a synopsis of the 2008 NHLBI/NIH guidelines. Am J Haematol. 2009;84:366–70. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Metjian AD, Wang C, Sood SL, et al. Bleeding symptoms and laboratory correlation in patients with severe von Willebrand disease. Haemophilia. 2009;15 :1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2009.02025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lim W, Moffat K, Hayward CP. Prophylactic and perioperative replacement therapy for acquired factor XIII deficiency. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2:1017–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Answar R, Miloszewski KJ. Factor XIII deficiency. Br J Haematol. 1999;107:468–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keeling D, Tait C, Makris M. Guidelines on the selection and use of therapeutic products to treat haemophilia and other hereditary bleeding disorders. Haemophilia. 2008;14:671–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2008.01695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Santagostino E. Linee guida per la terapia sostitutiva dell’emofilia e dei difetti ereditari della coagulazione. Associazione Italiana dei Centri Emofilia; 2003. [Last accessed: 25/03/2010]. Available at: http://www.aiceonline.it/documenti/LineeGuida/ITALIA_Coagulopatie.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mannucci PM, Franchini M, Castaman G, et al. Evidence-based recommendations on the treatment of von Willebrand disease in Italy. Blood Transfus. 2009;7 :117–26. doi: 10.2450/2008.0052-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lethagen S, Kyrle PA, Castaman G, et al. The Haemate P Surgical Study Group. Von Willebrand factor/factor VIII concentrate (Haemate P) dosing based on pharmacokinetics: a prospective multicenter trial in elective surgery. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:1420–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Federici AB, Castaman G, Franchini M, et al. Clinical use of Haemate P in inherited von Willebrand disease: a cohort study on 100 Italian patients. Haematologica. 2007;92:944–51. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Borel-Derlon A, Federici AB, Roussel-Robert V, et al. Treatment of severe von Willebrand disease with a high-purity von Willebrand factor concentrate (Wilfactin® ): a prospective study of 50 patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:1115–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines for the use of platelet transfusions. Br J Haematol. 2003;122:10–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bosly A, Muylle L, Noens L, et al. Guidelines for the transfusion of platelets. Acta Clin Belg. 2007;62:36–47. doi: 10.1179/acb.2007.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rebulla P, Finazzi G, Marangoni F, et al. The threshold for prophylactic platelet transfusions in adults with acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1870–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712253372602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rebulla P. Platelet transfusion trigger in difficult patients. Transfus Clin Biol. 2001;8:249–54. doi: 10.1016/s1246-7820(01)00129-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tosetto A, Balduini CL, Cattaneo M, et al. Management of bleeding and of invasive procedures in patients with platelet disorders and/or thrombocytopenia: Guidelines of the Italian Society for Haemostasis and Thrombosis (SISET) Thromb Res. 2009;124:e13–8. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Obstetric Anesthesia. Practice guidelines for obstetric anesthesia: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Obstetric Anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:843–63. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000264744.63275.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Levi M, Toh CH, Thachil J, Watson HG. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of disseminated intravascular coagulation. British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Br J Haematol. 2009;145:24–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Callow CR, Swindell R, Randall W, Chopra R. The frequency of bleeding complications in patients with haematological malignancy following the introduction of a stringent prophylactic platelet transfusion policy. Br J Haematol. 2002;118:677–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines on the management of massive blood loss. Br J Haematol. 2006;135:634–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Levi M. Current understanding of disseminated intravascular coagulation. Br J Haematol. 2004;124:567–76. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gringeri A. Linee guida per la diagnosi ed il trattamento di pazienti con inibitori dei fattori plasmatici della coagulazione. Associazione Italiana dei Centri Emofilia. 2004. [Last accessed: 25/03/2010]. Available at: http://www.aiceonline.it/documenti/LineeGuida/AICE_guida_inib_2004_finale.pdf.

- 57.Hay CR, Brown S, Collins PW, et al. The diagnosis and management of factor VIII and IX inhibitors: a guideline from the United Kingdom Haemophilia Centre Doctors Organisation. Br J Haematol. 2006;133:591–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bolton-Maggs PH, Perry DJ, Chalmers EA, et al. The rare coagulation disorders: review with guidelines for management from the United Kingdom Haemophilia Centre Doctors’ Organisation. Haemophilia. 2004;10:593–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2004.00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peyvandi F, Palla R, Menegatti M, Mannucci PM. Introduction. Rare bleeding disorders: general aspects of clinical features, diagnosis, and management. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2009;35:349–55. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1225757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miller Y, Bachowski G, Benjamin R, et al. A Compilation from Recent Peer-Reviewed Literature. 2nd ed. American National Red Cross; 2007. [Last accessed: 25/03/2010]. Practice Guidelines for Blood Transfusion. Available at: http://www.redcross.org/www-files/Documents/WorkingWiththeRedCross/practiceguidelinesforbloodtrans.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ranucci M, Isgrò G, Soro G, et al. Efficacy and safety of recombinant activated factor VII in major surgical procedures. Arch Surg. 2008;143:296–304. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2007.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mannucci PM, Levi M. Prevention and treatment of major blood loss. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2301–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra067742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cardone D, Klein AA. Perioperative blood conservation. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2009;26:722–9. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e32832c5280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vincent JL, Rossaint R, Riou B, et al. Recommendations on the use of recombinant activated factor VII as an adjunctive treatment for massive bleeding: a European perspective. Crit Care. 2006;10:R120. doi: 10.1186/cc5026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shander A, Goodnough LT, Ratko T, et al. Consensus recommendations for the off-label use of recombinant human factor VIIa (NovoSeven) therapy. Pharma Ther. 2005;30:644–58. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Welsh A, McLintock C, Gatt S, et al. Guidelines for the use of recombinant activated factor VII in massive obstetric haemorrhage. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;48:12–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2007.00823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stanworth SJ, Birchall J, Doree CJ, Hyde C. Recombinant factor VIIa for the prevention and treatment of bleeding in patients without haemophilia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2:CD005011. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005011.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.European Medicines Agency. NovoSeven. European Public Assessment Report. Procedural steps taken and scientific information after the authorization. [Last accessed 11/01/2010]. Changes made after 01/02/2004. Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Procedural_steps_taken_and_scientific_information_after_authorisation/human/000074/WC500030872.pdf.

- 69.European Medicines Agency. NovoSeven. Allegato I. Riassunto delle caratteristiche del prodotto. [Last accessed: 11/01/2010]. Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/it_IT/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000074/WC500030873.pdf.

- 70.Carless PA, Stokes BJ, Moxey AJ, et al. Desmopressin use for minimising perioperative allogeneic blood transfusion. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2004;1:CD 001884. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001884.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mannucci PM. Desmopressin: an historical introduction. Haemophilia. 2008;14 (Suppl 1):1–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2007.01609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Franchini M. The use of desmopressin as a hemostatic agent: a concise review. Am J Hemat. 2007;82:731–5. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cattaneo M. The use of desmopressin in open-heart surgery. Haemophilia. 2008;14 (Suppl 1):40–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2007.01608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.German Medical Association. Cross-Sectional Guidelines for Therapy with Blood Components and Plasma Derivatives. 4th revised edition. 2009. [Last accessed: 25/03/2010]. Available at: http://www.bundesaerztekammer.de/downloads/LeitCrossBloodComponents4ed.pdf.

- 75.Liumbruno GM, Bennardello F, Lattanzio A, et al. Recommendations for the use of antithrombin concentrates and prothrombin complex concentrates. Blood Transfus. 2009;7:325–34. doi: 10.2450/2009.0116-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hathaway WE, Goodnight SH., Jr . Malattie dell’Emostasi e Trombosi. Milano: McGraw-Hill Companies Italia; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Afshari A, Wetterslev J, Brok J, Møller AM. Antithrombin III for critically ill patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;3:CD005370. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005370.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Afshari A, Wetterslev J, Brok J, Møller A. Antithrombin III in critically ill patients: systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. BMJ. 2007;335:1248–51. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39398.682500.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Roberts HR, Monroe DM, Escobar MA. Current concepts of hemostasis: implication for therapy. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:722–30. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200403000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Russell MW, Jobes D. What should we do with aspirin, NSAIDs, and glycoprotein-receptor inhibitors? Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2002;40:63–76. doi: 10.1097/00004311-200204000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schroeder WS, Gandhi PJ. Emergency management of hemorragic complications in the era of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antagonists, clopidogrel, low molecular weight heparin, and third-generation fibrinolytic agents. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2003;5:310–7. doi: 10.1007/s11886-003-0068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Patrono C, Rocca B. Aspirin 110 years later. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7 (Suppl 1):258–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Strom BL, Berlin JA, Kinman JL, et al. Parenteral ketorolac and risk of gastrointestinal and operative site bleeding. A postmarketing surveillance study. JAMA. 1996;275:376–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dunning J, Versteegh M, Fabbri A, et al. Guidelines on antiplatelet and anticoagulation management in cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;34:73–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lecompte T, Hardy F. Antiplatelets agents and perioperative bleeding. Can J Anesth. 53:S103–16. doi: 10.1007/BF03022257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gresele P. Perioperative handling of antiplatelet therapy: watching the two sides of the coin. Intern Emerg Med. 2009;4:275–6. doi: 10.1007/s11739-009-0271-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Di Minno NMD, Prisco D, Ruocco AL, et al. Perioperative handling of patients on antiplatelet therapy with need for surgery. Intern Emerg Med. 2009;4 :279–88. doi: 10.1007/s11739-009-0265-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dunn AS, Turpie AG. Perioperative management of patients receiving oral anticoagulants: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:901–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.8.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.NIH - Consensus Conference. Fresh-frozen plasma. Indications and risks. JAMA. 1985;253:551–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines for the use of fresh frozen plasma. Transfus Med. 1992;2:57–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.1992.tb00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vorstand und wissenschaftlicher Beirat der Bundesärztekammer. Leitlinien zur Therapie mit Blutkomponenten und Plasmaderivaten (Revision 2003) Köln: Deutscher Ärzte-Verlag; 2003. Gefrorenes Frischplasma. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ortiz P, Mingo A, Lozano M, et al. Guide for transfusion of blood components. Med Clin (Barc) 2005;125:389–96. doi: 10.1157/13079172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Stanworth SJ, Brunskill SJ, Hyde CJ, et al. Appraisal of the evidence for the clinical use of FFP and plasma fractions. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2006;19 :67–82. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2005.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dzik WH. The NHLBI Clinical Trials Network in transfusion medicine and hemostasis: an overview. J Clin Apher. 2006;21:57–9. doi: 10.1002/jca.20092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Warkentin TE, Crowther MA. Reversing anticoagulants both old and new. Can J Anaesth. 2002;49 (Suppl):S11–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Douketis JD, Johnson JA, Turpie AG. Low molecular-weight heparin as bridging anticoagulation during interruption of warfarin: assessment of a standardized periprocedural anticoagulation regimen. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1319–26. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.12.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cohen AT, Hirst C, Sherril B, et al. Meta-analysis of trials comparing ximelagatran with low molecular weight heparin for prevention of venous thromboembolism after major orthopaedic surgery. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1335–44. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.O’Donnell M, Linkins LA, Kearon C, et al. Reduction of out-of-hospital symptomatic venous thromboembolism by extended thromboprophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparin following elective hip arthroplasty: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1362–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.11.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kuczkowski KM. Labor analgesia for the parturient with herbal medicines use: what does an obstetrician need to know? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2006;274:233–9. doi: 10.1007/s00404-006-0136-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wang SM, Caldwell-Andrews AA, Kain ZN. The use of complementary and alternative medicines by surgical patients: a follow-up survey study. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:1010–5. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000078578.75597.F3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kaye AD, Clarke RC, Sabar R, et al. Herbal medicines: current trends in anesthesiology practice. A hospital survey. J Clin Anesth. 2000;12:468–71. doi: 10.1016/s0952-8180(00)00195-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cheng B, Hung CT, Chiu W. Herbal medicine and anaesthesia. Hong Kong Med J. 2002;8:123–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tsen LC, Segal S, Pothier M, et al. Alternative medicine use in presurgical patients. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:148–51. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200007000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ang-Lee MK, Moss J, Yuan CS. Herbal medicines and perioperative care. JAMA. 2001;286:208–16. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.German K, Kumar U, Blackford HN. Garlic and the risk of TURP bleeding. Br J Urol. 1995;76:518. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1995.tb07766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Liumbruno G, Bennardello F, Lattanzio A, et al. Recommendations for the transfusion of red blood cells. Blood Transfus. 2009;7:49–64. doi: 10.2450/2008.0020-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gurusami KS, Osmani B, Shara, et al. Non-surgical interventions to decrease blood loss and blood transfusion requirements for liver resection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;3:CD7378. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Smoller BR, Krushall MS. Phlebotomy for diagnostic laboratory tests in adults: pattern of use and effect on transfusion requirements. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:1233–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198605083141906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Alvarez GG, Fergusson DA, Neilpovitz DT, et al. Cell salvage does not minimize perioperative allogeneic blood transfusion in abdominal vascular surgery: a systematic review. Can J Anesth. 2004;51:425–31. doi: 10.1007/BF03018303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tinmouth AT, McIntyre LA, Fowler RA. Blood conservation strategies to reduce the need for red blood cell transfusion in critically ill patients. CMAJ. 2008;178:49–57. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Napolitano LM. Perioperative anemia. Surg Clin N Am. 2005;85:1215–27. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Shermack KM, Horn E, Rice TL. Erythropoietic agents for anemia of critical illness. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65:540–6. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Goodnough LT, Skine B, Brugnara C. Erythropoietin, iron and erythropoiesis. Blood. 2000;96:823–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Crosby E. Perioperative use of erythropoietin. Am J Ther. 2002;9:371–6. doi: 10.1097/00045391-200209000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Corwin HL, Gettinger A, Fabian TC, et al. Efficacy and safety of epoetin alfa in critically ill patients. N Eng J Med. 2007;357:965–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Goodnough LT, Marcus RE. Erythropoiesis in patients stimulated with erythropoietin: the relevance of storage iron. Vox Sang. 1998;75:128–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Madore F, Whiter CT, Foley RB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for assessment and management of iron deficiency. Kidney Int. 2008;74 (Suppl 110):S7–S11. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Goodnough LT, Verbrugge D, Marcus RE, et al. The effect of patient size and dose of recombinant human erythropoietin therapy on red blood cell expansion. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;179:171–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Goodnough LT, Price TH, Parvin CA. The endogenous erythropoietin response and the erythropoietic response to blood loss anemia: the effects of age and gender. J Lab Clin Med. 1995;126:57–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Beris P, Munoz M, Garcia-Erce JA, et al. Perioperative anemia management: consensus statement on the role of intravenous iron. Br J Anesth. 2008;100:599–604. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Auerbach M, Goodnough LT, Picard D, et al. The role of intravenous iron in anemia management and transfusion avoidance. Transfusion. 2008;48:988–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Auerbach M, Coyen D, Ballard H. Intravenous iron: from anathema to standard of care. Am J Hematol. 2008;83:580–8. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Fishbane S, Ungureanu VD, Maeska JK, et al. The safety of intravenous iron dextran in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 1996;28:529–34. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(96)90463-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kim YH, Chung HH, Kang SB, et al. Safety and usefulness of intravenous iron sucrose in the management of preoperative anemia in patients with menorrhagia: a phase IV, open label, prospective, randomized study. Acta Haematol. 2009;121:37–41. doi: 10.1159/000210062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Fishbane S. Safety in iron management. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:S18–26. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00373-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hayat A. Safety issues with intravenous iron products in the management of anemia in chronic kidney disease. Clin Med Res. 2008;34:93–102. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2008.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Aronoff GR. Safety of intravenous iron in clinical practice: implications for anemia management protocols. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:S99–106. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000143815.15433.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Notebaert E, Chauny JM, Albert M, et al. Short-term benefits and risks of intravenous iron: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transfusion. 2007;47:1905–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]