Abstract

Dietary supplement use has steadily increased over time since the 1970s; however, no current data exist for the U.S. population. Therefore, the purpose of this analysis was to estimate dietary supplement use using the NHANES 2003–2006, a nationally representative, cross-sectional survey. Dietary supplement use was analyzed for the U.S. population (≥1 y of age) by the DRI age groupings. Supplement use was measured through a questionnaire and was reported by 49% of the U.S. population (44% of males, 53% of females). Multivitamin-multimineral use was the most frequently reported dietary supplement (33%). The majority of people reported taking only 1 dietary supplement and did so on a daily basis. Dietary supplement use was lowest in obese adults and highest among non-Hispanic whites, older adults, and those with more than a high-school education. Between 28 and 30% reported using dietary supplements containing vitamins B-6, B-12, C, A, and E; 18–19% reported using iron, selenium, and chromium; and 26–27% reported using zinc- and magnesium-containing supplements. Botanical supplement use was more common in older than in younger age groups and was lowest in those aged 1–13 y but was reported by ~20% of adults. About one-half of the U.S. population and 70% of adults ≥ 71 y use dietary supplements; one-third use multivitamin-multimineral dietary supplements. Given the widespread use of supplements, data should be included with nutrient intakes from foods to correctly determine total nutrient exposure.

Introduction

The use of dietary supplements has increased over time in the United States (1). The NHANES has been used to monitor the use of dietary supplements since the 1970s. In NHANES I (1971–1974), age-adjusted prevalence of dietary supplement use was 28% and 38% among adult males and females, respectively; in NHANES II (1976–1980), adult supplement prevalence rates were 32% among males and 43% among females (ages ≥ 20 y) (1). In NHANES III, (1988–1994) use of dietary supplements was 35% for males and 43% among females (ages ≥ 2 mo) and use increased with advancing age (2). Since 1999, NHANES data have been collected continuously in 2-y cycles. NHANES data have been used to describe the prevalence of supplement use of children and adults in 1988–1994 (3, 4), among adults in 1999–2000 (5), and among infants, children, and adolescents in 1999–2002 (6). The purpose of this analysis was to update the prevalence estimates of dietary supplement use in the U.S. population for all ages using the most recent data from NHANES 2003–2006.

Methods

The NHANES is a nationally representative, cross-sectional survey that samples noninstitutionalized, civilian U.S. residents using a complex, stratified, multistage probability cluster sampling design (7). NHANES participants are asked to complete an in-person household interview and a follow-up health examination in a Mobile Examination Center. All data presented in this report were collected during the household interview. The unweighted interview response rate for all participants was 79% for NHANES 2003–2004 and 80% NHANES 2005–2006. Survey years 2003–2004 (n = 10,122) were combined with 2005–2006 (n = 10,348) for this analysis (n = 20,470). Individuals under the age of 1 y (n = 1003) were excluded. Pregnant females were also excluded (n = 674). Persons with unknown or missing data on the use of dietary supplements were deleted (n = 35). Thus, the final analytic sample was 18,758. Written informed consent was obtained for all participants or proxies and the survey protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Review Board at the CDC/National Center for Health Statistics.

Demographic data, including age, gender, race/ethnicity, and level of educational attainment, were collected through a computer-assisted personal interview. Self-reported height and weight were collected using the Weight History Questionnaire. Dietary supplement use information was collected as part of the Dietary Supplement Questionnaire. The Dietary Supplement Questionnaire is used to collect information on the participant’s use of vitamins, minerals, herbals, and other supplements over the past 30 d. Detailed information about type, consumption frequency, duration, and amount taken is also collected for each reported dietary supplement use. Dietary supplement use was also examined in 3 major classes: multi-vitamin, multi-mineral (MVMM),5 botanicals, and amino acids. For MVMM use, we constructed “use” as a product containing 3 or more vitamins (DSDCNTV) and 1 or more mineral counts (DSDCNTM) per supplement. Similarly, use of a botanical ingredient product was determined by the botanical count variable (DSDCNTB) and use of an amino acid-containing product was determined with the amino acid count variable (DSDCNTA).

Statistical analysis.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9, SAS Institute) and SAS-callable SUDAAN (version 9, Research Triangle Institute) software. Sample weights were used to account for differential nonresponse, noncoverage, and to adjust for planned over-sampling of some groups. SE for all statistics of interest were approximated by Taylor Series Linearization. Data were analyzed by the age groups specified in the DRI developed by the Food and Nutrition Board of the National Academy of Sciences (8).

Descriptive data are presented for the population, for adults only, and by gender and DRI age group using proc descript in SAS-callable Sudaan. For prevalence rates across age groups, we used Hsu’s procedure (9) to determine (for the population and within gender) which age groups had the highest and lowest value(s) for dietary supplement use (10). Hsu’s procedure was employed once to find the largest and once to find the smallest population prevalence(s); P-value was set at 0.025.

Adults (≥20 y) were also analyzed separately from children to examine relationships with BMI, race/ethnicity, and educational attainment. BMI was defined as kg/m2 and the CDC BMI classifications were used: obese (BMI ≥ 30), overweight (BMI 25–29.9, and normal-weight individuals (BMI < 24.9). Education was divided into 3 groups: less than high school (HS), HS diploma or equivalent, and those with more than a HS education. Three race/ethnic groups are available in the NHANES data: non-Hispanic white (NHW), non-Hispanic black, and Mexican-American. Group differences for the prevalence of daily supplement use within BMI, education, and race/ethnic groups were analyzed using a contrast statement in proc descript; significance was set at P ≤ 0.025.

Results

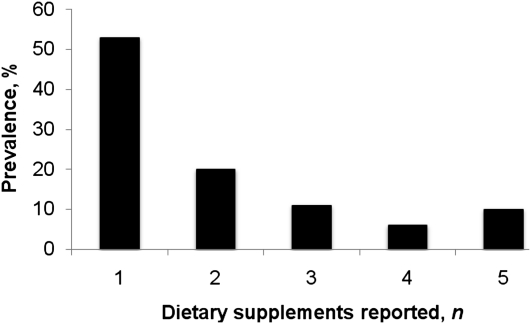

Dietary supplement use was reported by 49% (44% of males, 53% of females) of the U.S. population aged 1 y and older (Table 1). In general, dietary supplement use in all categories increased with age. Most people reported taking only 1 dietary supplement (Fig. 1). The majority of users (79%) reported taking them every day within the last 30 d, 12% reported use between 20 and 29 d, 9% between 10–19 d, and 9% reported use <10 d (data not shown). Across the 3 major categories of use, the prevalence of MVMM use was highest (33%) followed by use of botanical supplements (14%) and amino acids (4%; data not shown). MVMM use was highest among those ≥ 51 y and was also high among males 4–8 y. Use of botanical supplements was more common in older than in younger age groups and was lowest in those aged 1–13 y.

TABLE 1.

Prevalence of dietary supplement use in the past month among the U.S. population aged ≥1 y by gender and DRI age groups1

| n | Age, y | Any supplement, % | MVMM | Botanical |

| Total | ||||

| 18,758 | All ≥ 1 | 49 ± 0.9 | 33 ± 0.9 | 14 ± 0.6 |

| 1781 | 1–3 | 39 ± 1 | 26 ± 2 | 2 ± 0.4a |

| 1975 | 4–8 | 43 ± 2 | 32 ± 2 | 4 ± 1a |

| 2233 | 9–13 | 29 ± 2 a | 20 ± 1a | 3 ± 1a |

| 2812 | 14–18 | 26 ± 2 a | 16 ± 1a | 5 ± 1 |

| 2283 | 19–30 | 39 ± 1 | 27 ± 1 | 13 ± 1 |

| 3112 | 31–50 | 49 ± 1 | 35 ± 1 | 18 ± 1b |

| 2709 | 51–70 | 65 ± 2 b | 44 ± 2b | 20 ± 1b |

| 1853 | ≥71 | 71 ± 1 b | 46 ± 2b | 17 ± 1b |

| Males | ||||

| 9490 | All ≥ 1 | 44 ± 1 | 31 ± 1 | 13 ± 1 |

| 892 | 1–3 | 39 ± 2 | 27 ± 2 | - 2 |

| 963 | 4–8 | 46 ± 3 | 35 ± 2b | 4 ± 1a |

| 1106 | 9–13 | 29 ± 2 a | 18 ± 2a | 4 ± 1a |

| 1455 | 14–18 | 23 ± 1 a | 14 ± 1a | 5 ± 1 |

| 1222 | 19–30 | 36 ± 2 | 25 ± 2 | 14 ± 1b |

| 1594 | 31–50 | 44 ± 1 | 32 ± 1 | 16 ± 1b |

| 1342 | 51–70 | 58 ± 2 | 40 ± 2b | 18 ± 1b |

| 916 | ≥71 | 66 ± 2 b | 43 ± 2b | 18 ± 1b |

| Females | ||||

| 9268 | All ≥ 1 | 53 ± 1 | 36 ± 1 | 15 ± 1 |

| 889 | 1–3 | 38 ± 2 | 25 ± 2a | 3 ± 1a |

| 1012 | 4–8 | 40 ± 3 | 28 ± 3 | 3 ± 1a |

| 1127 | 9–13 | 29 ± 3a | 23 ± 3a | 2 ± 0.6a |

| 1357 | 14–18 | 30 ± 2a | 19 ± 2a | 6 ± 1 |

| 1061 | 19–30 | 43 ± 2 | 30 ± 1 | 13 ± 1 |

| 1518 | 31–50 | 55 ± 2 | 38 ± 2 | 21 ± 2b |

| 1367 | 51–70 | 72 ± 2b | 48 ± 2b | 21 ± 2b |

| 937 | ≥71 | 75 ± 2b | 48 ± 2b | 16 ± 1b |

All values are percentages ± SE. Superscripts denote sets within age and within gender and age groupings with prevalence estimates that are statistically indistinguishable from the lowest (a) or highest (b) population mean, as determined by Hsu's procedure with = 0.025.

Relative SE ≥ 40%; this estimate is not stable and is omitted.

FIGURE 1.

The number of supplements taken by U.S. adult supplement users, NHANES, 2003–2006, n = 9132.

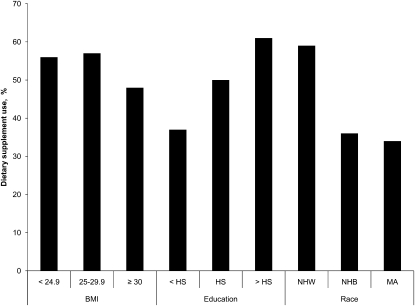

Among adults, 54% reported dietary supplement use. Obese individuals took fewer dietary supplements (48%) than overweight (57%) or normal-weight individuals (56%) (Fig. 2). Dietary supplement use was different among all education levels, with the highest use in those with more than a HS education (61%) and lowest use in those with less than a HS education (37%). NHW whites had a higher use of dietary supplements (59%) than non-Hispanic black (36%) or Mexican-American (34%).

FIGURE 2.

The prevalence of use of dietary supplements among U.S. adults ≥ 20 y by weight status, educational attainment, and race/ethnic group, NHANES 2003–2006. Values are the percentage of participants that used dietary supplements. Within BMI, education, and race/ethnic group, means without a common letter differ, P ≤ 0.025, n = 9132.

Between 28 and 31% of the U.S. population took supplements containing 1 or more of the following vitamins: B-6, B-12, C, A, and E; 17% took supplements containing vitamin K (Table 2). Use of vitamins B-6 and B-12 dietary supplements was most common among adults ≥ 51 y and among children ≥ 8 y. Vitamin C use was highest in those ≥ 51 y and among 4–8 y olds. Vitamin A use was highest in those ≥ 71 and ≤ 8 y of age. Vitamin E use was highest among 4–8 y olds and individuals ≥ 71 y. Vitamin K use was highest among those ≥ 51 y. The lowest prevalence of use of vitamin supplements was among adolescents (14–18 y olds) with the exception of vitamin K. The lowest prevalence of vitamin K use was among those aged ≤13 y.

TABLE 2.

Prevalence of vitamin-containing dietary supplement use in the past month among the U.S. population aged ≥ 1 y by gender and DRI age groups12

| n | Age, y | Vitamin B-6 | Vitamin B-12 | Vitamin C | Vitamin A | Vitamin E | Vitamin K |

| Total | |||||||

| 18,758 | All ≥ 1 | 29 ± 1 | 29 ± 1 | 31 ± 1 | 28 ± 1 | 29 ± 1 | 17 ± 0.5 |

| 1781 | 1–3 | 32 ± 2b | 31 ± 2b | 34 ± 2 | 33 ± 2b | 32 ± 2 | 3 ± 1a |

| 1975 | 4–8 | 36 ± 2b | 36 ± 2b | 38 ± 2b | 37 ± 2b | 37 ± 2b | 4 ± 1a |

| 2233 | 9–13 | 21 ± 1 | 21 ± 1 | 23 ± 2 | 22 ± 1 | 21 ± 1 | 5 ± 1a |

| 2812 | 14–18 | 16 ± 1a | 15 ± 1a | 18 ± 1a | 15 ± 1a | 15 ± 1a | 9 ± 1 |

| 2283 | 19–30 | 23 ± 1 | 23 ± 1 | 25 ± 1 | 22 ± 1 | 23 ± 1 | 15 ± 1 |

| 3112 | 31–50 | 29 ± 1 | 28 ± 1 | 30 ± 1 | 26 ± 1 | 28 ± 1 | 19 ± 1 |

| 2709 | 51–70 | 35 ± 1b | 36 ± 1b | 37 ± 2b | 33 ± 1 | 35 ± 1 | 27 ± 1b |

| 1853 | ≥ 71 | 36 ± 1b | 36 ± 1b | 41 ± 1b | 37 ± 1b | 40 ± 1b | 28 ± 1b |

| Males | |||||||

| 9490 | All ≥ 1 | 27 ± 1 | 27 ± 1 | 30 ± 1 | 26 ± 1 | 27 ± 1 | 18 ± 1 |

| 892 | 1–3 | 33 ± 3b | 32 ± 3b | 34 ± 2b | 33 ± 3b | 33 ± 2b | 2 ± 0.6a |

| 963 | 4–8 | 39 ± 3b | 39 ± 3b | 41 ± 3b | 40 ± 3b | 40 ± 3b | 4 ± 1a |

| 1106 | 9–13 | 20 ± 2 | 20 ± 2 | 23 ± 2 | 20 ± 2 | 20 ± 2 | 5 ± 1a |

| 1455 | 14–18 | 13 ± 1a | 12 ± 1a | 15 ± 1a | 12 ± 1a | 12 ± 1a | 7 ± 1 |

| 1222 | 19–30 | 21 ± 2 | 21 ± 2 | 23 ± 2 | 21 ± 2 | 21 ± 2 | 18 ± 2 |

| 1594 | 31–50 | 27 ± 1 | 26 ± 1 | 28 ± 1 | 25 ± 1 | 25 ± 1 | 22 ± 1b |

| 1342 | 51–70 | 34 ± 2b | 34 ± 1b | 36 ± 2b | 31 ± 2b | 33 ± 2b | 28 ± 2b |

| 916 | ≥ 71 | 35 ± 2b | 35 ± 2b | 40 ± 2b | 37 ± 2b | 40 ± 2b | 26 ± 2b |

| Females | |||||||

| 9268 | All ≥ 1 | 30 ± 1 | 30 ± 1 | 33 ± 1 | 29 ± 1 | 31 ± 1 | 17 ± 1 |

| 889 | 1–3 | 31 ± 2b | 30 ± 2 | 33 ± 2 | 32 ± 2b | 31 ± 2 | 3 ± 1a |

| 1012 | 4–8 | 32 ± 3b | 32 ± 3b | 34 ± 3b | 33 ± 3b | 33 ± 3b | 4 ± 1a |

| 1127 | 9–13 | 22 ± 2a | 23 ± 2 | 24 ± 2 | 23 ± 2 | 23 ± 2a | 5 ± 1a |

| 1357 | 14–18 | 18 ± 2a | 18 ± 2a | 22 ± 2a | 18 ± 2a | 17 ± 2a | 10 ± 1 |

| 1061 | 19–30 | 25 ± 2a | 25 ± 2a | 27 ± 2a | 23 ± 1 | 25 ± 2 | 11 ± 1 |

| 1518 | 31–50 | 31 ± 1b | 30 ± 2a | 33 ± 2a | 28 ± 1 | 30 ± 2 | 17 ± 1 |

| 1367 | 51–70 | 37 ± 2b | 37 ± 2b | 39 ± 2b | 35 ± 2b | 37 ± 2b | 27 ± 2b |

| 937 | ≥ 71 | 36 ± 2b | 37 ± 1b | 42 ± 1b | 38 ± 1 | 41 ± 2b | 29 ± 1b |

All values are percentages ± SE. Superscripts denote sets within age and within gender and age groupings with prevalence estimates that are statistically indistinguishable from the lowest (a) or highest (b) population mean, as determined by Hsu's procedure with = 0.025.

Prevalence calculated for vitamins from single or multiple ingredient products.

The use of selected minerals ranged from 18 to 27% in the U.S. population (Table 3) and magnesium was the most used mineral dietary supplement. Iron dietary supplement use was highest among 4–8 y olds and lowest in 9–18 y olds. Among males, 14–18 y olds had the lowest use of iron. Among females, those aged 19–30 y and 31–50 y had the highest iron use at 23 and 26%, respectively. Use of zinc, magnesium, selenium, and chromium was highest in those older than 51 y. Magnesium use was lowest in those 1–3 y and 9–18 y. Selenium and chromium use was low in those under the age of 13 y and highest in those ≥ 51 y.

TABLE 3.

Prevalence of mineral-containing dietary supplement use in the past month among the US population aged ≥1 y by gender and DRI age groups12

| n | Age, y | Iron | Zinc | Magnesium | Selenium | Chromium |

| Total | ||||||

| 18,758 | All ≥ 1 | 18 ± 0.6 | 26 ± 1 | 27 ± 0.5 | 19 ± 0.5 | 19 ± 0.5 |

| 1781 | 1–3 | 16 ± 2 | 18 ± 1 | 16 ± 1a | 1 ± 0.3a | 4 ± 1a |

| 1975 | 4–8 | 20 ± 2b | 25 ± 2 | 22 ± 2 | 1 ± 0.3a | 4 ± 1a |

| 2233 | 9–13 | 14 ± 1a | 17 ± 1 | 15 ± 1a | 3 ± 0.6 | 5 ± 1a |

| 2812 | 14–18 | 12 ± 1a | 13 ± 1a | 14 ± 1a | 9 ± 1 | 10 ± 1 |

| 2283 | 19–30 | 19 ± 1 | 22 ± 1 | 23 ± 1 | 16 ± 1 | 17 ± 1 |

| 3112 | 31–50 | 22 ± 1 | 26 ± 1 | 29 ± 1 | 21 ± 1 | 22 ± 1 |

| 2709 | 51–70 | 16 ± 1 | 34 ± 2b | 37 ± 1b | 30 ± 1b | 29 ± 1b |

| 1853 | ≥71 | 16 ± 0.9 | 36 ± 1b | 35 ± 1b | 32 ± 1b | 29 ± 1b |

| Males | ||||||

| 9490 | All ≥ 1 | 15 ± 0.6 | 24 ± 1 | 26 ± 1 | 19 ± 1 | 20 ± 1 |

| 892 | 1–3 | 17 ± 2b | 18 ± 2 | 15 ± 2a | 1 ± 0.2a | 4 ± 1a |

| 963 | 4–8 | 21 ± 2b | 27 ± 2 | 23 ± 2 | 1 ± 0.4a | 4 ± 1a |

| 1106 | 9–13 | 13 ± 1 | 16 ± 2a | 14 ± 2a | 3 ± 0.8 | 5 ± 1a |

| 1455 | 14–18 | 10 ± 1a | 11 ± 1a | 12 ± 1a | 7 ± 0.9 | 8 ± 1 |

| 1222 | 19–30 | 15 ± 2b | 21 ± 2 | 23 ± 2 | 19 ± 2 | 20 ± 2 |

| 1594 | 31–50 | 17 ± 1b | 25 ± 1 | 28 ± 1 | 23 ± 1 | 23 ± 1 |

| 1342 | 51–70 | 13 ± 1 | 31 ± 2b | 36 ± 2b | 30 ± 2b | 30 ± 2b |

| 916 | ≥ 71 | 14 ± 1 | 34 ± 2b | 34 ± 2b | 32 ± 2b | 29 ± 2b |

| Females | ||||||

| 9268 | All ≥ 1 | 21 ± 0.7 | 28 ± 1 | 28 ± 1 | 18 ± 1 | 18 ± 1 |

| 889 | 1–3 | 15 ± 2a | 18 ± 2a | 16 ± 2a | 2 ± 0.7a | 4 ± 1a |

| 1012 | 4–8 | 18 ± 2a | 24 ± 2 | 21 ± 2 | 2 ± 0.4a | 4 ± 0.8a |

| 1127 | 9–13 | 15 ± 2a | 18 ± 2a | 17 ± 2a | 3 ± 0.8a | 5 ± 1a |

| 1357 | 14–18 | 15 ± 2a | 16 ± 2a | 17 ± 2a | 10 ± 1 | 11 ± 1 |

| 1061 | 19–30 | 23 ± 1b | 24 ± 1 | 23 ± 2 | 13 ± 1 | 13 ± 1 |

| 1518 | 31–50 | 26 ± 1b | 28 ± 1 | 30 ± 1 | 20 ± 1 | 20 ± 1 |

| 1367 | 51–70 | 19 ± 2a | 36 ± 2b | 38 ± 2b | 30 ± 2b | 29 ± 2b |

| 937 | ≥ 71 | 17 ± 1a | 37 ± 1b | 36 ± 2b | 33 ± 1b | 30 ± 1b |

All values are percentages ± SE. Superscripts denote sets within age and within gender and age groupings with prevalence estimates that are statistically indistinguishable from the lowest (a) or highest (b) population mean, as determined by Hsu's procedure with = 0.025.

Prevalence calculated for minerals from single or multiple ingredient products.

Discussion

In 2003–2006, dietary supplement use was reported by one-half of all Americans, an increase of ∼10 percentage points from NHANES III (1988–1994) (2). The majority of people who used dietary supplements used only one; however, ∼10% of Americans reported taking >5 dietary supplements. Among adults, use was 54% in NHANES 2003–2006, an increase from the NHANES 1999–2000 data that indicates 52% of adults use dietary supplements. Dietary supplement use was associated with weight status, education, and race/ethnicity. Similar to other studies, overweight and obese individuals were less likely to use dietary supplements, those with higher educational attainments were more likely to use dietary supplements, and NHW were more likely than other racial and ethnic groups to use dietary supplements (11, 12). Picciano et al. (6) reported 32% dietary supplement use in children from birth to 18 y in NHANES 1999–2002, with the lowest use reported among teenagers 14–18 y old (26%) and highest use among 4- to 8-y-old children (49%). Our results show that “any” dietary supplement use was similar in 14–18 y olds (26%) but was 43% among 4–8 y old children.

Among both adults and children, MVMM were the most commonly reported dietary supplement, consistent with results from previous studies (5, 6, 11, 12). However, the definitions and categorization of MVMM dietary supplements are not standardized (13). This lack of standardization makes it difficult to compare prevalence estimates between populations and even within populations. Radimer et al. (5) defined a MVMM as containing 3 or more vitamins with or without minerals; 35% of adults reported use of a MVMM by this definition in 1999–2000. In the present analysis, we define a MVMM as containing 3 or more vitamins but required at least 1 mineral to be present to call it a multimineral; 33% of the U.S. population reported use of a MVMM by this definition. For comparison, we analyzed 2003–2006 data using the Radimer et al. (5). MVMM definition and found that 40% of adults ≥ 20 y used MVMM (data not shown). Thus, one clear pattern is that MVMM use is high and has increased over time in adults and MVMM use increases with age through adulthood.

Picciano et al. (6) reported MVMM use in the same age categories and using the same MVMM definition as this present analysis, permitting comparison of use over time in children from NHANES 1999–2002 to 2003–2006 (change not statistically evaluated between time periods). MVMM use among 1–3 y olds changed from 18 to 26%, from 25 to 32% among 4–8 y olds, from 19 to 20% among 9–13 y olds, and among 14–18 y olds from 14 to 16% between the time periods of 1999–2002 and 2003–2006. Thus, use of MVMM seemed to increase over time in children 1–8 y and remained relatively stable in adolescents 9–18 y olds when the time period 1999–2002 was compared with 2003–2006.

This is the first report, to our knowledge, to characterize botanical dietary supplement use in adults in NHANES since NHANES III (1988–1994) (3). The 2003–2006 NHANES data indicate ~20% of adults use a dietary supplement with at least 1 botanical ingredient, which could be in a combination product (e.g. MVMM plus echinacea) or as a botanical dietary supplement (e.g. a product exclusively containing echinacea). Data from the 2007 National Health Interview Survey indicated that ~18% of adults and ~12% of children used “nonvitamin, nonmineral natural products” (14). As with MVMM, classification and definitions of nonvitamin, nonmineral, or botanical dietary supplement is inconsistent (3). Current efforts at the federal level to initiate a LanguaL classification system for dietary supplements are being investigated. LanguaL is an automated method for describing dietary supplements (15–17); this type of system would harmonize reporting of dietary supplements and allow for cross study comparison on dietary supplement use.

Very little change occurred between 1999–2002 and 2003–2006 among children and adolescents (age 1–18 y) for use of dietary supplements containing calcium (10), vitamin A (6), or folic acid (18, 19). However, for iron-containing dietary supplements, there was a 5 percentage point decrease in 1–3 and 9–13 y olds, and a 7 percentage point decrease in 4–8 y olds from NHANES 1999–2002 (6) to 2003–2006 (change not statistically evaluated). This may be of concern given that toddlers are at high risk for iron deficiency in the US (20, 21).

The methods used in NHANES to accurately identify and record the specific dietary supplements reported by participants ensures high quality data. Although the dietary supplement data are self-reported, 85% of the time, NHANES interviewers saw the dietary supplement bottles and labels that participants reported using to verify accuracy. We did not present data for pregnant females and this information is virtually unknown (22). The small sample size of pregnant females in NHANES has been the primary challenge in ascertaining reliable estimates of dietary supplement use in this population subgroup. Calcium, vitamin D, and folic acid dietary supplement use has been previously reported in NHANES 2003–2006 in adults and children and is therefore not presented in this report (10, 18, 19).

In conclusion, dietary supplements are used by one-half of the U.S. population and appears to have increased slightly in adults since 1999–2000. MVMM are the most commonly reported dietary supplement across all age groups. Botanical use is reported by ∼20% of adults. In children, more than one-third report using supplements containing vitamins B-6, B-12, C, A, and E. Dietary supplements may contain nutrients in amounts as high as or higher than DRI recommendations and can contribute substantially to total nutrient intake. Without consideration of nutrient intakes from dietary supplements, there is a potential to misclassify the prevalence of nutrient inadequacy and excess (10, 18, 19, 23). These data suggest a high prevalence of dietary supplement use in the U.S. population.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is dedicated to Dr. Mary Frances Picciano, who developed the idea and was the inspiration behind this effort. R.L.B., J.T.D., J.S.E., P.R.T., J.M.B., C.T.S., and M.F.P. contributed to the concept development and manuscript preparation; C.V.L. and J.J.G. contributed to the methodological and statistical aspects of the work, as well as manuscript review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: DRI, dietary reference intake; HS, high school; NHW, non-Hispanic white; MVMM, multi-vitamin, multi-mineral.

Deceased, August 2010.

Literature Cited

- 1.Briefel RR, Johnson CL. Secular trends in dietary intake in the United States. Annu Rev Nutr. 2004;24:401–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ervin RB, Wright JD, Kennedy-Stephenson J. Use of dietary supplements in the United States, 1988–94. Vital Health Stat 11. 1999:i–iii, 1–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Radimer KL, Subar AF, Thompson FE. Nonvitamin, nonmineral dietary supplements: issues and findings from NHANES III. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000;100:447–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Block G, Jensen CD, Norkus EP, Dalvi TB, Wong LG, McManus JF, Hudes ML. Usage patterns, health, and nutritional status of long-term multiple dietary supplement users: a cross-sectional study. Nutr J. 2007. Oct 24;6:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radimer K, Bindewald B, Hughes J, Ervin B, Swanson C, Picciano MF. Dietary supplement use by US adults: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2000. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:339–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Picciano MF, Dwyer JT, Radimer KL, Wilson DH, Fisher KD, Thomas PR, Yetley EA, Moshfegh AJ, Levy PS. Dietary supplement use among infants, children, and adolescents in the United States, 1999–2002. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:978–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Center for Health Statistics About the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Hyattsville (MD); 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Food and Nutrition Board Dietary reference intakes applications in dietary assessment. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsu JC. Simultaneous confidence intervals for all distances from the "best". Ann Stat. 1981;9:1026–34 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bailey RL, Dodd KW, Goldman JA, Gahche JJ, Dwyer JT, Moshfegh AJ, Sempos CT, Picciano MP. Estimation of total usual calcium and vitamin D intakes in the United States. J Nutr. 2010;140:817–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foote JA, Murphy SP, Wilkens LR, Hankin JH, Henderson BE, Kolonel LN. Factors associated with dietary supplement use among healthy adults of five ethnicities: the Multiethnic Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:888–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rock CL. Multivitamin-multimineral supplements: who uses them? Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:S277–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yetley EA. Multivitamin and multimineral dietary supplements: definitions, characterization, bioavailability, and drug interactions. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:S269–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report 2008:1–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pennington JA, Hendricks TC. Proposal for an international interface standard for food databases. Food Addit Contam. 1992;9:265–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pennington JA, Hendricks TC, Douglass JS, Petersen B, Kidwell J. International Interface Standard for Food Databases. Food Addit Contam. 1995;12:809–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hendricks TC, Langua L. An automated method for describing, capturing and retrieving data about food. World Rev Nutr Diet. 1992;68:94–103 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bailey RL, Dodd KW, Gahche JJ, Dwyer JT, McDowell MA, Yetley EA, Sempos CA, Burt VL, Radimer KL, Picciano MF. Total folate and folic acid intake from foods and dietary supplements in the United States: 2003–2006. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:231–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bailey RL. McDowell MA, Dodd KW, Gahche JJ, Dwyer JT, Picciano MF. Total folate and folic acid intakes from foods and dietary supplements of US children aged 1–13 y. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:353–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Looker AC, Dallman PR, Carroll MD, Gunter EW, Johnson CL. Prevalence of iron deficiency in the United States. JAMA. 1997;277:973–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cogswell ME, Looker AC, Pfeiffer CM, Cook JD, Lacher DA, Beard JL, Lynch SR, Grummer-Strawn LM. Assessment of iron deficiency in US preschool children and nonpregnant females of childbearing age: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2006. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:1334–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Picciano MF, McGuire MK. Use of dietary supplements by pregnant and lactating women in North America. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:S663–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murphy SP, White KK, Park SY, Sharma S. Multivitamin-multimineral supplements' effect on total nutrient intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:S280–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]