Abstract

Polarized Ca2+ signals in secretory epithelial cells are determined by compartmentalized localization of Ca2+ signaling proteins at the apical pole. Recently the ER Ca2+ sensor STIM1 and the Orai channels were shown to play a critical role in store-dependent Ca2+ influx. STIM1 also gates the TRPC channels. Here, we asked how cell stimulation affects the localization, recruitment and function of the native proteins in polarized cells. Inhibition of Orai1, STIM1, or deletion of TRPC1 reduces Ca2+ influx and frequency of Ca2+ oscillations. Orai1 localization is restricted to the apical pole of the lateral membrane. Surprisingly, cell stimulation does not lead to robust clustering of native Orai1, as is observed with expressed Orai1. Unexpectedly, cell stimulation causes polarized recruitment of native STIM1 to both the apical and lateral regions, thus to regions with and without Orai1. Accordingly, STIM1 and Orai1 show only 40% co-localization. Consequently, STIM1 shows higher co-localization with the basolateral membrane marker E-cadherin than does Orai1, while Orai1 showed higher co-localization with the tight junction protein ZO1. TRPC1 is expressed in both apical and basolateral regions of the plasma membrane. Co-IP of STIM1/Orai1/IP3Rs/TRPCs is enhanced by cell stimulation and disrupted by 2APB. The polarized localization and recruitment of these proteins results in preferred Ca2+ entry that is initiated at the apical pole. These findings reveal that in addition to Orai1, STIM1 likely regulates other Ca2+ permeable channels, such as the TRPCs. Both channels contribute to the frequency of [Ca2+] oscillations and thus impact critical cellular functions.

Keywords: STIM1, Orai1, TRPC1, polarized, recruitment, epithelial cells

Introduction

The receptor-evoked Ca2+ signal in polarized cells, such as pancreatic and salivary gland (SG) acinar and duct cells, is unique in that it starts at the apical pole and propagates to the basal pole (1, 2). The basis for the polarized Ca2+ signal can be ascribed to the polarized arrangement of key Ca2+ signaling proteins. Thus, GPCR (3), IP3 receptors (4–6), TRPC channels (7, 8), the plasma membrane Ca2+ pump (PMCA) (9) and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ pump (SERCA2b) (10) are markedly enriched at the apical pole. Indeed, many components of the Ca2+ signaling complex can be co-immunoprecipitated (co-IP) (11), indicating assembly of the proteins into a tight complex.

Another crucial component of the Ca2+ signal is the store-operated Ca2+ channel (SOC) that is activated in response to Ca2+ release from the ER. Ca2+ influx by the SOCs maintains and controls the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations, reloads the ER with Ca2+ on termination of the stimulus and mediates almost all cellular functions regulated by Ca2+ (1, 12, 13). The expression pattern of native SOC channels, as well as their possible relocation after cell stimulation are unknown.

Until recently the molecular identity and mechanism of gating of SOCs was not known. This changed with the discovery of STIM1 (14, 15) and the Orai channels (16–18). STIM1 is a multidomain, Ca2+ binding protein that functions as the ER Ca2+ sensor (14, 15). At the resting state STIM1 is diffusely localized in the ER with its luminal EF hand domain bound to Ca2+. Depletion of ER Ca2+ results in dissociation of Ca2+ from the STIM1-EF hand domain as well as aggregation and clustering of STIM1 at close proximity to the plasma membrane where it interacts with the SOCs (14, 15, 19–21).

There are two types of STIM1-regulated SOCs that have been described; Orai channels that mediate the CRAC current (16–18) and TRPC channels, which function as Ca2+ permeable non-selective cation channels (22–25). STIM1 gates both channel types by different mechanisms. The STIM1-SOAR domain interacts with the C-terminus of the Orais and is sufficient to open the channels (26, 27). The STIM1 ERM domain mediates interaction of STIM1 with the TRPC channels (28) to heteromultimerize them (25). The ERM domain then presents the STIM1 polybasic domain to the TRPCs, which activates the channels by an electrostatic gating mechanism (29).

It is clear that TRPC channels account for part of the SOCs in pancreatic and salivary glands cells, as revealed by the reduction of SOC activity in cells obtained from mice with deletion of TRPC1 (30) and TRPC3 (31), with consequent attenuation of cell function. We have shown before that TRPC3 is concentrated in the apical pole together with all other components of the Ca2+ signaling complexes (7, 8). However, localization and function of TRPC1 in pancreatic acini is not known. Similarly, the exact localization and role of the Orais in Ca2+ influx in secretory cells is not well established. Given that STIM1 regulates the Orai (18, 32) and TRPC channels (22–25), we expected that it should be enriched at the apical pole. However, a recent study reported that store depletion resulted in accumulation of expressed and native STIM1 mostly in the basal aspect of pancreatic acinar cells and in segregation of STIM1 and IP3R3 (33). Similarly, expressed Orai1 was also targeted in part to the basal and lateral membranes (33). On the other hand, recent immunohistochemical staining suggested that Orai1 localization was not uniform (34).

In the present work, we have examined the function and localization of native STIM1 and Orai1 in resting and stimulated exocrine secretory cells as well as their interaction with key components of Ca2+ signaling complexes. We are reporting that expression of inhibitory peptides or knockdown of Orai1 or STIM1 by siRNA reduce Ca2+ influx leading to reduced frequency of receptor-stimulated Ca2+ oscillations. The use of anti-STIM1 (35, 36) and anti-Orai1 antibodies (34) with established specificity reveals that Orai1 expression is primarily restricted in the lateral membrane close to the apical pole. In response to cell stimulation, STIM1 is predominantly recruited to the apical and lateral regions next to plasma membrane domains with and without Orai1. Plasma membrane regions with high localization of STIM1 but without Orai1 express TRPC1. These findings are strongly supported by mutual co-IP of STIM1, Orai1, IP3R3 and TRPC1 and enhancement of their co-IP by cell stimulation. Most notably, treatment with 2APB, which dissociates STIM1 clusters with native Orai1 (37–39), disrupted the polarized recruitment of native STIM1 and the co-IP of STIM1-Orai1-IP3Rs-TRPC1 complexes. These findings show polarized recruitment of native STIM1 in specialized cell types, that the native STIM1 is recruited to Orai1-containing and Orai1-free cellular domains and stress the significance of the apical pole as a Ca2+ signaling center.

Results

The discovery of STIM1 and Orai1 and their prominent role in SOCs raised the question of their role and localization in Ca2+ signaling in specialized polarized cells like secretory cells. The Ca2+ signal in secretory cells is unique in that it is highly polarized, always initiating at the apical pole and propagating to the basal pole (1, 2). That the molecular basis for the polarized Ca2+ signal is highly polarized and restricted localization of all Ca2+ signaling proteins examined has been firmly established (1). This would predict polarized expression and recruitment of Orai1 and STIM1, respectively, in polarized cells. Moreover, in response to cell stimulation and store depletion the expressed ER localized STIM1 and plasma membrane localized Orai1 are recruited to form punctae at which STIM1 and Orai1 show perfect co-localization (19, 21, 26, 40, 41). It is not known whether there is a similar perfect co-localization of the native STIM1 and Orai1. This is of particular importance since STIM1 also gates the TRPC channels (22–25) that have prominent role in receptor stimulated Ca2+ influx in secretory cells (30, 31). The present studies which were set to address these questions resulted in several unexpected findings with significant implications for the mechanism of Ca2+ influx in secretory cells.

Role of endogenous STIM1 and Orai1 in secretory cell Ca2+ signaling

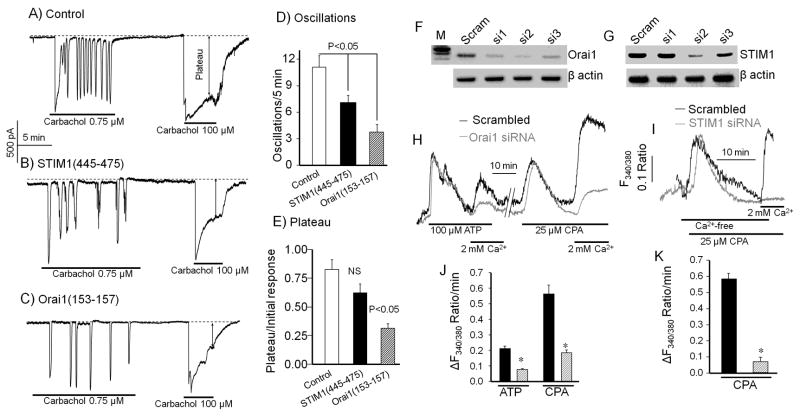

First, we have sought to establish a role for STIM1 and Orai1 in Ca2+ signaling by secretory cells. Since the use of siRNA probes cannot be employed in native acinar that lose polarity within 12 hrs in culture, the recent development of probes that inhibit the activity of STIM1 and Orai1 offers a reasonable alternative. The STIM1(445–475) fragment inhibits the native CRAC current when infused into Jurkat cells (40). [Ca2+]i in pancreatic acinar cells was followed by recording the Ca2+-activated Cl− current (11) to allow infusing the cells with peptides through the patch pipette. Figs. 1A and 1B show that infusion of STIM1(445–475) into pancreatic acinar cells reduce the frequency by about 35% of Ca2+ oscillations triggered by weak receptor stimulation. Inhibition of the fully activated Ca2+ influx (plateau phase) by STIM1(445–475) did not reach statistical significance, likely because the peptide is a weak inhibitor of Ca2+ influx (40). Nevertheless, even partial inhibition of Ca2+ influx was sufficient to reduce the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations. A five residues Orai1(153–157) fragment was reported to strongly inhibit the current mediated by expressed STIM1-Orai1 (42). Figs. 1C and 1E show that infusion of this fragment into pancreatic acinar cells inhibited Ca2+ influx by about 50% and reduced the frequency of the Ca2+ oscillations by about 70%. Hence, there is a good correlation between inhibition of Ca2+ influx and reduced Ca2+ oscillations frequency, highlighting the crucial role of Ca2+ influx in sustaining the oscillation and determining their frequency.

Fig. 1. Inhibition of Ca2+ signaling by STIM1 and Orai1 inhibitory peptides in pancreatic acini and by siRNA knockdown in parotid ducts.

[Ca2+]i is monitored as changes in the Ca2+-activated Cl− current, which faithfully reports changes in pancreatic acinar cells [Ca2+]i. Acinar cells were infused with pipette solution (A, control) containing 50 μM of the STIM1 inhibitory peptide STIM1(445–475) (B), or 50 μM of the Orai1 inhibitory peptide Orai1(153–157) (C), for 7 min before stimulation with 0.75 μM carbachol to induce Ca2+ oscillations and then with 100 μM carbachol to maximally activate Ca2+ influx. The average oscillation frequency is shown in (D) and the plateau in (E). The dashed lines are the zero current. The plateau (marked by a line with double arrows) was normalized relative to the initial increase in current due to Ca2+ release from the ER. The columns show the meam±s.e.m of 7 experiments.

The efficiency of the Orai1 (F) and STIM1 (G) siRNA probes was determined by RT-PCR in mouse keratinocytes. (H, J) show the response of sealed parotid ducts treated with scrambled (dark traces and columns) or with Orai1 siRNA and stimulated with 100 μM ATP in Ca2+-free media and then exposed to media containing 2 mM Ca2+ to evaluate Ca2+ influx. The ducts were then perfused with Ca2+-containing media for 10 min to load the stores before treatment with 25 μM CPA in Ca2+-free media and finally exposed to media containing Ca2+ to evaluate SOC activity. (I, K) Parotid ducts treated with scrambled or STIM1 siRNA were treated with 25 μM CPA in Ca2+-free media and then exposed to Ca2+-containing media to measure SOC activity. Panels (J, K) show the meam±s.e.m of 4 ducts.

To further demonstrate the role of STIM1 and Orai1 in Ca2+ signaling in secretory cells we used an independent assay to test the effect of their knockdown on Ca2+ influx in parotid gland sealed ducts in primary culture, in which siRNA effectively knockout the desired genes (43–45). Ducts were prepared from the parotid gland to show the role of STIM1 and Orai1 in another secretory cell type. Figs. 1F and 1G show the efficiency of the knockdown of Orai1 and STIM1 by three siRNA probes. The second probe for each gene was used for the experiments shown, but we also tested the effect of the siRNA1 for Orai1 and siRNA3 for STIM1 to exclude off target effects and obtained similar results. Figs. 1H,J show that knockdown of Orai1 have reduced Ca2+ influx activated by receptor stimulation or by store depletion by about 65% and Figs. 1I,K show that knockdown of STIM1 has reduced SOC by about 85%.

Polarized localization of native Orai1

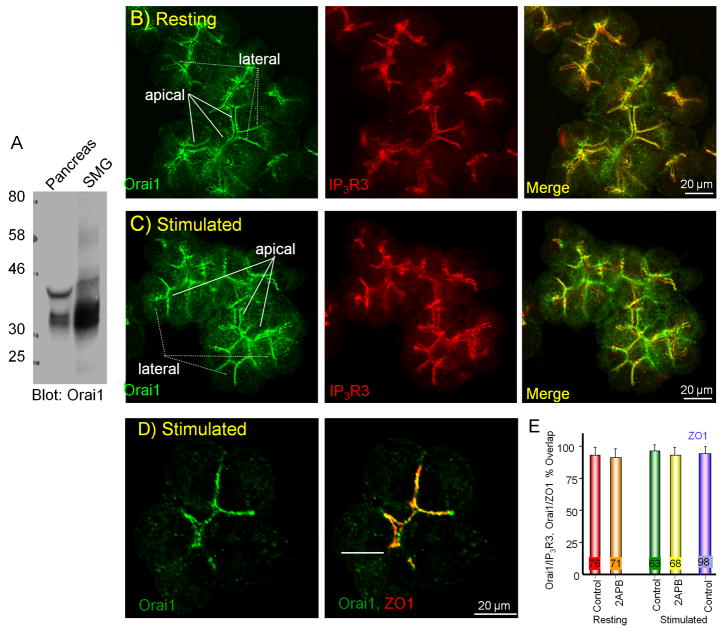

The specificity of the antibody used to localize Orai1 has been validated in a recent report showing that the immunohistochemical signal obtained in wild-type tissues is eliminated in tissues obtained from patient and mice with deletion of Orai1 (34). Fig. 2A shows that this anti-Orai1 antibody detected Orai1 in pancreatic and salivary gland extracts. Fig. 2B shows that Orai1 localization is restricted to the lateral membrane of pancreatic acinar cells (arrows), similar to the localization of a number of key Ca2+ signaling proteins (1). Staining is also observed at the lateral membrane most adjacent to the apical pole (dotted arrows) and there is no detectable staining of Orai1 in the basal plasma membrane region, suggesting that the level of Orai1, if it is expressed at this site, is very low.

Fig. 2. Localization of Orai1 in pancreatic acini.

The anti-Orai1 antibody detects Orai1 in pancreatic and submandibular gland extracts (A). To deplete the ER Ca2+ store acini in Ca2+- free media containing 1 mM EGTA were stimulated with 0.5 mM carbachol and treated with 25 μM CPA for 10 min. The acini were then fixed and co-stained for Orai1 and IP3R3 (B, C) or ZO1 (D). In (B, C) membranes next to the apical pole are marked with solid arrows and the lateral membranes are marked with dashed arrows. In (E) images acquired from resting and stimulated cells that were treated with vehicle or with 50 μM 2APB were used to determine the overlap of Orai1 with IP3R3 and with ZO1. The results are the mean±s.e.m of the number of cells indicated in the columns. There is no significant difference between all conditions.

The luminal plasma membrane in the apex of acinar cells is small but folds along the lateral membrane at the apical pole, where the two membranes are separated by tight junctions (3, 46). Staining of the tight junctions in pancreatic acini resulted in an image very similar to that obtained with Orai1 (3). Indeed, co-staining with the tight junction protein ZO1 shows nearly perfect co-localization of Orai1 and ZO1 (Fig. 2D) with 94±5% overlap (n=98 cells).

Another Ca2+ signaling protein expressed in this region of the cell is the ER-located IP3R. Accordingly, localization of Orai1 significantly overlaps with IP3R3 (Fig. 2D, 93±6%, n=76 cells). Although a significant portion of Orai1 transfected in pancreatic acinar cells is targeted to the apical pole, localization of the expressed Orai1 was more homogeneous at the plasma membrane (33). We cannot fully explain the difference between the present and previous findings. However, it might be due to over-expression of Orai1 overwhelming the cellular protein sorting and trafficking machinery.

Cell stimulation and depletion of ER Ca2+ result in clustering of expressed Orai1 (19, 21, 26, 27, 40, 41). However, cell stimulation together with inhibition of the SERCA pumps have had no dramatic effect on the unique polarized localization of native Orai1 in acinar cells (Fig. 2C). Additionally, treating the cells with 2APB had no effect on the localization of Orai1 (Fig. 2D). The images in Fig. 2 were acquired at a plane showing the maximal expression of Orai1 and IP3R3 and ZO1. However, similar tight overlap between Orai1 and IP3R3 and ZO1 was observed in all cellular planes. A possible implication of this finding is that in the polarized acinar cells, Orai1 is already targeted to its site of function and further targeting or relocation is not needed. This may ensure the highly polarized Ca2+ signal in these cells.

Polarized recruitment of native STIM1

Given the polarized localization of Orai1 in Fig. 2 and the tight co-clustering of heterologously expressed STIM1 and Orai1 in response to store depletion (19, 21, 26, 40, 41), we expected STIM1 to show a similar localization as Orai1 in stimulated cells. We examined the localization of the native STIM1 using two different anti-STIM1 antibodies with established specificity. One antibody raised against the conserved STIM1(657–685) detected the native STIM1 and, importantly, the signal was eliminated in tissues from patients who lack STIM1 (34). Fig. S1 shows that this antibody reported diffused STIM1 staining in resting acinar cells with more intense staining at the basal pole. Cells stimulation did not result in massive redistribution of this staining to the basal pole, but rather induced recruitment of STIM1 to the apical (turquoise arrowheads) and lateral regions close to the plasma membranes (yellow arrowheads) (Fig. S1B). The SOC inhibitor 2APB that disrupts clustering of STIM1 with native Orai1 (37–39) had no obvious effect on STIM1 localization in resting cells, but markedly reduced accumulation of STIM1 at the apical and lateral plasma membrane regions (Fig. S1C). Another notable finding is that the recruited STIM1 and IP3R3 show only partial co-localization along the lateral membrane (turquoise squares in Fig. S1B). This is different from the findings with Orai1 (see also below), where there was >90% overlap with IP3R3.

Similar, but superior staining was obtained with a second anti-STIM1 antibody. Staining with the Protein-Tech antibody was eliminated in tissue from STIM1−/− mice (35). We further validated the use of this antibody in Fig. S2 by showing that it recognizes the native and expressed STIM1 in HeLa cells (panel A), showing reduced signal in STIM1 siRNA-treated HeLa cells (panes B, D), and gaving the expected STIM1 staining in resting and stimulated cells (panels B, C).

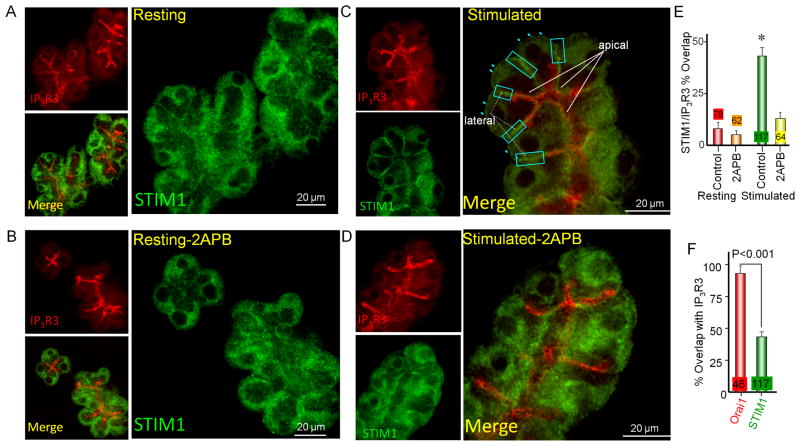

Fig. 3 shows the localization of STIM1 relative to IP3R3 obtained with this antibody. Resting cells show primarily diffuse STIM1 localization (Fig 3A). Treating resting cells with 2APB did not have any effect on this localization (Figs. 3B and 3E). Cell stimulation and store depletion recruited STIM1 primarily to the apical pole (solid arrows) and lateral cellular regions (dashed arrows), with small amount of STIM1 punctae at the basal membrane region (turquoise arrowheads) (Fig 3C). STIM1 at the apical pole shows excellent co-localization with IP3R3 (Fig. 3C). Unexpectedly, intense accumulation of STIM1 at the lateral membrane region was at a region free of IP3Rs (turquoise squares). Hence, STIM1 showed only 43±6% (n=117) overlap with IP3R3 (Fig. 3E). An important control is shown in Figs. 3D and 3E, in which treatment with 2APB disrupted STIM1 accumulation, reducing the overlap with IP3R3 to 13±3% (n=64), which is not different from the overlap in resting cells.

Fig. 3. Localization of STIM1 in pancreatic acini.

Resting acini (A, B) were maintained in solution A, whereas stimulated acini (C, D) are acini in Ca2+- free media containing 1 mM EGTA that were stimulated with 0.5 mM carbachol and treated with 25 μM CPA for 10 min. Control and stimulated acini were also treated with 50 μM 2APB (B, D) that was added just before cell stimulation. The acini were then co-stained for STIM1 and IP3R3. In (C) membranes next to the apical pole are marked with solid arrows and lateral membranes are marked with dashed arrows. Punctae at the basal and lateral membranes are marked with turquoise arrows. The turquoise squares in all images depict area showing high expression of STIM1 and no IP3R3. In (E) images collected from resting and stimulated cells that were treated with vehicle or with 50 μM 2APB were used to determine the overlap of STIM1 with IP3R3. (F) compares the overlaps of Orai1 and STIM1 with IP3R3. The results are the mean±s.e.m of the indicated number of cells. * denote p<0.01 from resting cells.

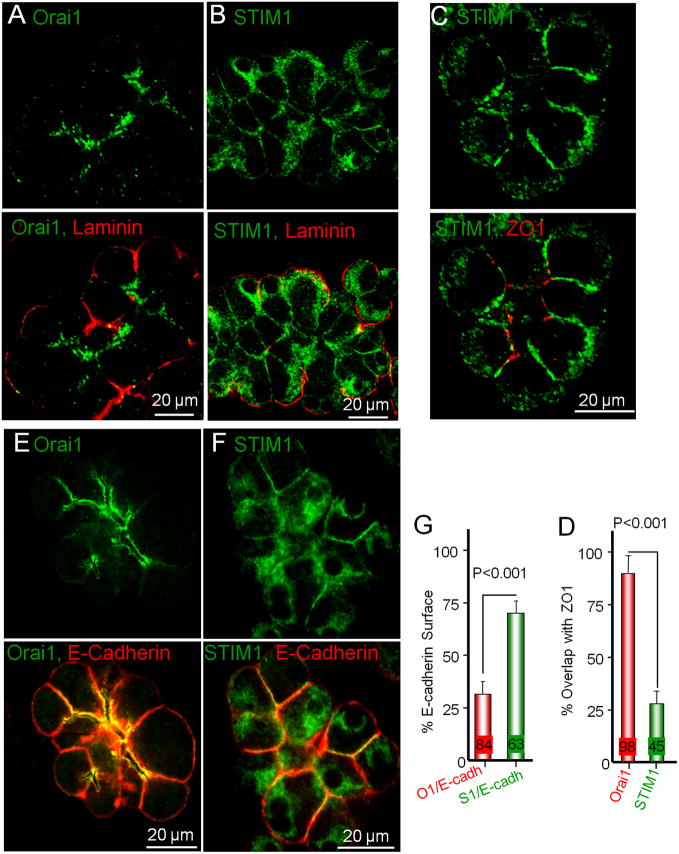

To further confirm the unexpected differential overlap of Orai1 and STIM1 with IP3R3 (summarized in Fig. 3F) we compared co-localization of STIM1 and Orai1 with other marker proteins. In Fig. 4A and 4B the basal membrane was stained with laminin to show more clearly the very low level or no localization of STIM1 and Orai1 at this site. Fig. 4C shows the partial localization of STIM1 at the tight junction and Fig. 4D shows quantification of the dramatic difference in the co-localization of Orai1 and STIM1 with ZO1. We also measured the area of the basolateral membrane that overlaps with the Orai1 and STIM1. The basolateral membrane was visualized with E-cadherin. The images in Fig. 4E and 4F were acquired in planes optimal to observe the basolateral membrane with E-cadherin. Figs. 4E and 4G show that Orai1 was detected in 28±3.3% (n=84 cells) of the basolateral membrane domain, whereas Figs. 4F and 4G show that STIM1 was detected in 67±4.5% (n=63 cells) of the basolateral membrane domain.

Fig. 4. Plasma membrane area occupied by Orai1 and STIM1 in pancreatic acini.

Store-depleted and receptor stimulated acini were stained with the basal membrane marker laminin (A, B), the tight junction marker ZO1 (C) and the basolateral membrane E-cadherin (E, F) (all red). The acini were co-stained with Orai1 (A, E) or STIM1 (B, C, F). (D) compares the overlap of STIM1 and Orai1 with ZO1 and in (G) images similar to those in (E) and (F) were used to determine the % basolateral membrane expressing Orai1 or with adjacent STIM1. The results are the mean±s.e.m of the number of cells indicated in the columns.

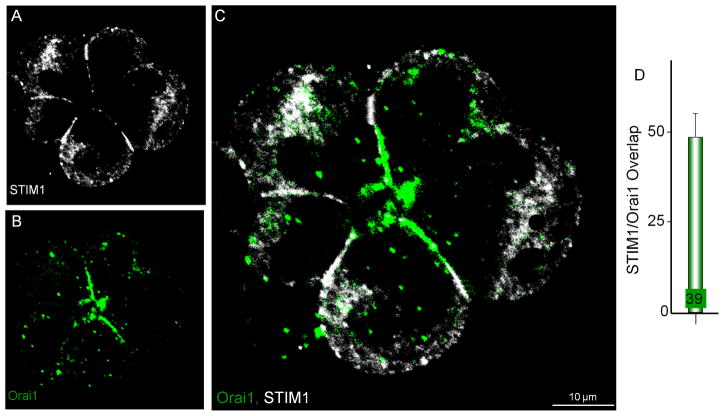

Finally, we tagged the anti-STIM1 antibodies with Alexa Fluor® 647 and used it to determine localization of STIM1 and Orai1 in the same stimulated cells. Fig. 5 shows that only about 50% of STIM1 co-localizes with Orai1, which confirms the results obtained with IP3R3 and E-cadherin. Thus, the remaining STIM1 likely forms complexes with other Ca2+ influx channels.

Fig. 5. Co-localization of STIM1 and Orai1 in the same cells.

Store-depleted acini were labeled with Orai1 and then with the Alexa Fluor® 647-tagged STIM1 as detailed in methods. The double labeling procedure resulted in a significant background staining in the form of dots, mainly from the Orai1 antibodies. These were excluded from calculation of % overlap of STIM1 and Orai1. Overlap was restricted to the plasma membrane region and is shown in (D).

Polarized localization of native TRPC1

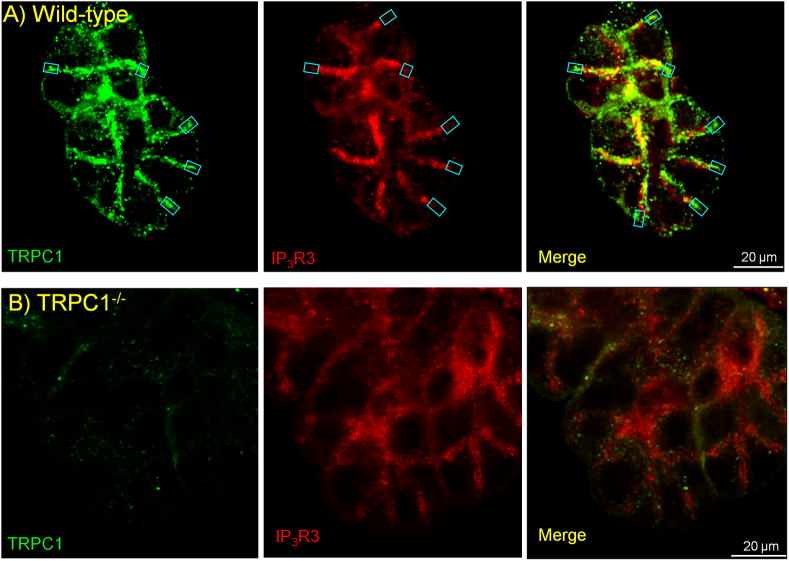

The distinct lateral regions that express STIM1 but not Orai1 raise the question of whether STIM1-interacting TRPC channels are localized at this region. Of particular interest is TRPC1 that is localized at the lateral membrane of salivary gland acinar cells (30). Unfortunately, detection of TRPC1 in pancreatic acini with the antibodies requires fixation with paraformaldehyde that precludes detection of IP3Rs. Reclaiming detection of the IP3Rs after paraformaldehyde fixation required incubation with cold MeOH, but this resulted in a non-specific intense staining of the secretory granules that overwhelmed the staining for TRPC1. Nevertheless, fixation with paraformaldehyde suggested that TRPC1 is localized at the apical and lateral regions of the basolateral membrane of pancreatic acinar cells (Fig. S3A). Pancreatic acinar cells from Trpc1−/− mice showed reduced Ca2+ influx (Fig. S3B) and Ca2+ oscillation frequency (Fig. S3C), indicating that TRPC1 mediates a significant portion of Ca2+ influx in these cells.

It was possible to obtain reasonable images of TRPC1 and IP3Rs in parotid acini treated with paraformaldehyde and MeOH. Fig. 6A shows staining of the lateral membranes with the anti-TRPC1 antibody and Fig. 6B shows that the staining is markedly reduced in Trpc1−/− parotid acini. Co-staining of Trpc1 and IP3R3 revealed lateral membrane regions with no overlap between them (turquoise squares), as was found with STIM1 (Fig. 3 and S1). Although the fixation procedure reduced the resolution of the IP3Rs images and precluded reliable calculation of overlap, the findings in Fig. 6 suggest that part of STIM1 is recruited to a plasma membrane domain expressing TRPC1, STIM1 and no Orai1. However, all the proteins, Orai1, TRPC1, IP3R3 as well as STIM1 co-localize in the lateral membrane close to the apical pole following cell stimulation.

Fig. 6. Localization of TRPC1 in parotid gland acini.

Acini from wild-type (A) and Trpc1−/− mice (B) were co-stained for TRPC1 (green) and IP3R3 (red). The turquoise squares in all images depict area showing high expression of TRPC1 and no IP3R3.

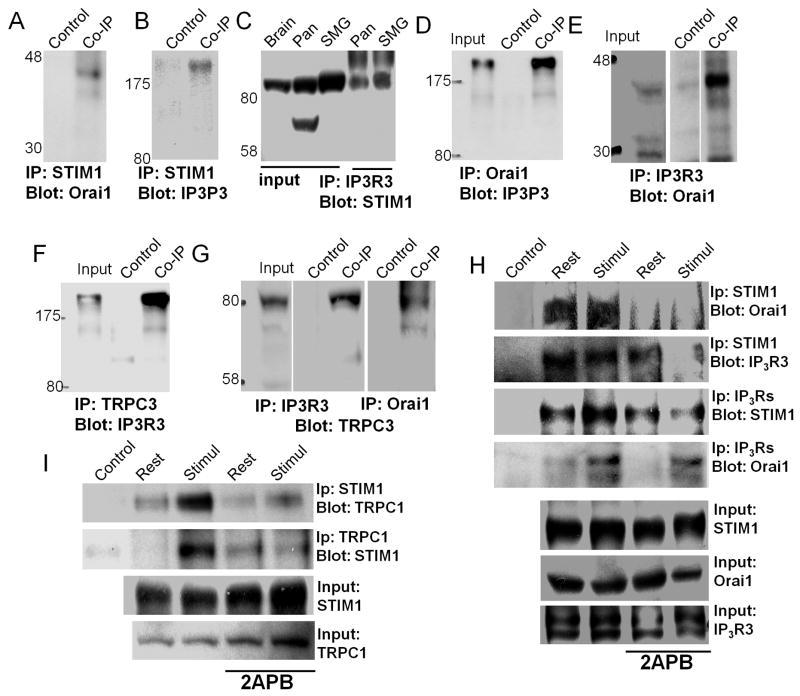

Co-IP of STIM1/Orai1/TRPC1/IP3R3

Co-localization by confocal microscopy is not sufficient to determine if the proteins exist in the same Ca2+ signaling complex. This can be tested more directly by co-IP assays. First, we determined if proteins expressed in model systems can be co-IPed. A recent study reported that cell stimulation enhances co-IP of expressed TRPC3-Orai1-STIM1-IP3R1 (47). Fig. S4 extends these findings by showing that the co-IP is enhanced by cell stimulation and it is reduced by treating the cells with 2APB. co-IP of expressed proteins can be markedly affected by their over-expression. Therefore, when possible, it is important to demonstrate co-IP of the native proteins. Therefore, next we examined the reciprocal co-IP of all native Ca2+ signaling proteins in pancreatic acinar cells. The co-IP of TRPC3 was examined since it shows close co-localization with IP3R3 (7), interacts with TRPC1 (25) and contributes to Ca2+ influx in acinar cells (31). Fig. 7A shows that IP of STIM1 co-IPs Orai1. Figs. 7B, and 7C show the reciprocal co-IP of IP3R3 and STIM1 and Figs. 7D and 7E show the reciprocal co-IP of IP3R3 and Orai1. TRPC3 co-IPs with IP3R3 (Figs. 7F and 7G) and with Orai1 (Fig. 7G).

Fig. 7. Co-immunoprecipitation of STIM1, Orai1, IP3R3, TRPC3 and TRPC1 is enhanced by cell stimulation and disrupted by 2APB.

For each set of experiments, extracts were prepared from the pancreas of two mice. Control lanes are without primary antibodies and inputs are 5% of the initial material used for the IP. Extracts were used to IP STIM1 (A, B) and probe for co-IP Orai1 (A) and IP3R3 (B); IP IP3R3 (C, E, G) and probe for co-IP of STIM1 (C), Orai1 (E) and TRPC3 (G); IP Orai1 (D, G) and probe for co-IP of IP3R3 (D) and TRPC3 G). In (H, I) part of the cells were not stimulated (rest) and part were stimulated by incubation in Ca2+- free media and treatment with 0.5 mM carbachol and 25 μM CPA for 10 min at 37 °C. Portions of resting and of stimulated cells were treated with 50 μM 2APB. Extracts were prepared from all four conditions and used to IP STIM1 (two upper blots in H) and probe for co-IP of Orai1 and IP3R3 and for IP IP3R3 (two middle blots in H) and probe for co-IP of STIM1 and Orai1. The bottom blots are the inputs. Extracts were also used to determine the reciprocal co-IP of STIM1 and TRPC1 (I). Note that cell stimulation enhances the co-IP, whereas treatment with 2APB reduces the co-IP.

Significantly, Fig. 7H shows that cell stimulation enhances the co-IP of IP3Rs with STIM1 and Orai1 and the co-IP is inhibited by treatment with 2APB. Fig. 7I shows the mutual co-IP of STIM1 and TRPC1, enhancement of the co-IP by cell stimulation and its disruption by treating the acini with 2APB. Hence, the native Orai1, STIM1, IP3Rs, TRPC3 and TRPC1 are in Ca2+ signaling complexes and STIM1 may stabilize the complexes, since the complexes are disrupted by 2APB. Because of the partial Orai1/STIM1 overlap and the overlap of TRPC3 and TRPC1 with STIM1 in regions that do not express STIM1, it is likely that STIM1 stabilizes complexes of several compositions: Orai1-STIM1; TRPC1/TRPC3-STIM1 and Orai1-STIM1-TRPC1/TRPC3. It will be of particular interest to test whether the various complexes mediate spatially different Ca2+ influx pathways that may regulate specific cellular functions.

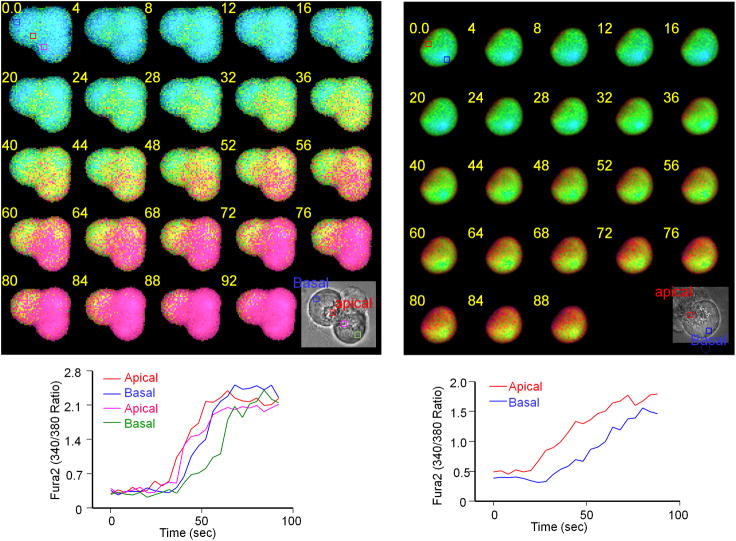

Polarized initiation of Ca2+ influx

To begin to evaluate the possibility that STIM1 may mediate several Ca2+ influx pathways that operate in different cellular microdomains, we analyzed initiation of Ca2+ influx in cells with fully depleted stores and thus maximally activated Ca2+ influx. In addition, the stores were depleted passively so as to minimize propagation of the Ca2+ signal due to cell stimulation. Fig. 8 shows that the consequence of the localization of TRPC channels, Orai1 and the recruited STIM1 at the apical pole next to the tight junctions is the generation of a defined Ca2+ influx site (Fig. 8, left images). Since these cells maintain polarity even when dissociated to single cells, we have also measured Ca2+ influx in single acinar cells to ensure uniform Ca2+ access to all parts of the plasma membrane. Fig. 8, right images show that also in single pancreatic acinar cells Ca2+ influx initiates at the apical pole. The rate of cytoplasmic Ca2+ increase due to Ca2+ influx is very slow, indicating that the Ca2+ signal does not propagate. Diffusion of Ca2+ in the cytoplasm is quite slow (48), and thus cytoplasmic Ca2+ increase at later times likely reflects Ca2+ influx through sites different from the initial site where Orai1 is present. These sites probably mediate Ca2+ entry through TRPC channels that are present at the lateral membrane.

Fig. 8. Site of Ca2+ entry in pancreatic acinar cells.

A three cells Acinus (left panels) and a single acinar cell (right panels) loaded with Fura2 were incubated in Ca2+- free media and were treated with 0.5 mM carbachol and 25 μM CPA to activate Ca2+ influx. When Ca2+ returned to basal level the cells were exposed to media containing 5 mM Ca2+ and images were collected every 0.3 sec to detect the initial sites of Ca2+ influx. The traces show the time course of the changes in Ca2+ recorded in the ROI indicated in the first fluoresce image and the bright field image.

Discussion

A key finding of the present work is the relatively restricted localization of Orai1 at the apical pole of the lateral membrane and the recruitment of part of STIM1 to this membranous region in response to receptor stimulation and Ca2+ store depletion. As it has been established previously, the apical pole of secretory cells is specialized to generate local Ca2+ signals that mediate the main function of polarized enzyme and fluid secretion by these cells (1, 2, 49). The restricted localization of native Orai1 in secretory cells is quite different from that seen in fibroblasts, muscle fibers, adrenal cells and parathyroid cells, where it is more uniformly distributed in the plasma membrane (34). Notably, cell stimulation and store depletion does not appear to cause massive clustering of Orai1. This is in sharp contrast to observations with the expressed Orai1 that co-clusters with expressed STIM1 (19, 21, 26, 27, 40, 41). While this again might be unique to secretory cells with their polarized functions, additional studies with other polarized cells as well as other cell types of the localization of endogenous Orai1 in resting and stimulated cells is required to determine the generality of this finding.

Another feature of secretory cells reported here is the recruitment of STIM1 to both the apical and lateral basolateral membrane regions. This localization is supported by multiple observations: a) Two different anti-STIM1 antibodies that did not stain STIM1−/− cells (34, 35) gave the same staining pattern, b) The antibodies detected native and expressed STIM1 and staining is markedly reduced in STIM1 siRNA-treated cell, c) The localization was disrupted by treatment with 2APB, which disrupts Orai1-STIM1 complexes (37–39), d) STIM1 localization overlaps with Orai1 and TRPC1 at the apical pole and with TRPC1 alone in the lateral region of the basolateral membrane, e) STIM1 was reciprocally co-IP’d with IP3R3, TRPC1 and Orai1, and the co-IP is enhanced by cell stimulation and disrupted by treatment with 2APB, f) Ca2+ influx initiates at the apical pole of these cells. The localization observed in the present work is different from that reported before using a different anti-STIM1 antibody (33), which can account for the different observations.

It is significant that all proteins involved in Ca2+ signaling and in Ca2+ influx show close localization at the apical pole of the basolateral membrane in resting cells. An exception is STIM1, which is localized diffusely in the cell and gets recruited to this region after cell stimulation where it forms or stabilizes the SOC complex and activates Ca2+ influx. We expected STIM1 to show complete co-localization with Orai1, since Orai1 and STIM1 as well as all STIM1 fragments that include SOAR, relocate to the same cellular location (19, 21, 26, 27, 40, 41). However, a significant amount of STIM1 was seen in the lateral membrane region where it did not co-localize with Orai1. This is the first example showing recruitment of STIM1 that is independent of Orai1. Hence, it appears that STIM1 can be recruited to form Orai1-dependent and Orai1-independent clusters. Since STIM1 associates with TRPC channels (22–25), and TRPC1 is expressed at the lateral and basal membranes of acinar cells (Figs. 6, S4 and (30)), it is possible that STIM1 at the lateral membrane region is associated with TRPC1. Indeed, TRPC1 co-IP with STIM1, the co-IP is enhanced by cell stimulation and disrupted by 2APB.

The acinar cells appear to have two Ca2+ influx domains and complexes, one that includes STIM1-Orai1 and TRPC channels and one composed of only STIM1 and TRPC channels. Several studies reported that the function of Orai1 and TRPC channels are interrelated (23, 50–53) and when expressed at physiologically low levels, the function of both channels is concomitantly required for SOC activity (23, 51, 52). This can account for the presence of TRPC1 in the most apical and lower part of the lateral membrane. At the lower lateral membrane STIM1 forms a complex with TRPC1 to activate Ca2+ influx at a domain that may have a different physiological role than Ca2+ influx at the apex of the lateral membrane.

The significance of the polarized recruitment of STIM1 to the apex of these cells is quite evident from their function. Exocytosis and fluid secretion requires high Ca2+ microdomains at the apical pole that must then propagate to the apical pole, especially to drive fluid secretion (1, 2, 49). Ca2+ influx is crucial for the receptor-stimulated Ca2+ oscillations (Figs. 1, S4, (31)). The unique restricted targeting of Orai1, TRPCs and IP3Rs and recruitment of STIM1 to this site may be designed to pre-determine the site of Ca2+ entry to ensure its fidelity and rapid activation. Indeed, this site appears to be the preferred site for initial Ca2+ influx (Fig. 8). It is possible that Ca2+ influx channels localized in the apical pole support the Ca2+ oscillations. The lateral Ca2+ influx channels may be activated when the demand for Ca2+ influx is increased during intense cell stimulation. Intense cell stimulation results in propagated, receptor-specific apical to the basal Ca2+ waves (1), where it regulates other mechanisms involved in exocrine secretion. The lateral Ca2+ influx may support the propagation of the Ca2+ waves. Further studies are required to determine the exact contributions of the apical and laterally localized Ca2+ influx channels to cell function.

Methods

Materials

Fura-2-acetoxymethyl ester (Fura-2/AM) was purchased from Teflabs (Austin, TX). carbamyl choline chloride (carbachol), HEPES, pyruvic acid, ATP, cyclopiazonic acid (CPA), 2-APB, soybean trypsin inhibitor (STI), and D-glucose were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Anti-IP3R3 monoclonal antibody (Ab) was from BD bioscience (San Jose, CA) and monoclonal anti-E-cadherin antibodies were from Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA. Anti-TRPC3 polyclonal Antibody was from Alomone Lab (Jerusalem, Israel) or Sigma. Anti-TRPC1 polyclonal antibody was described and its specificity validated before (30). The polyclonal anti-STIM1 antibody used in Figs. 2 and S3 was from Protein Tec (ProteinTech Group Inc., Chicago, IL). The antibody against STIM1 used in supplementary Fig. 2 is a rabbit polyclonal, affinity-purified antibody raised against a conserved 29 a.a. peptide corresponding to a.a. 657–685 of human STIM1 using standard protocols (Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL). The specificity of this antibody was verified in (34). The antibody against Orai1 is a rabbit polyclonal, affinity-purified antibody raised against a 17 a.a. peptide corresponding to a.a. 275–291 of human Orai1 and was generated using standard protocols (Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL). The specificity of this antibody was verified in (34). Generation and characterization of the Trpc1−/− mice was described before (30).

Isolation of acinar cells and preparation of sealed ducts

All procedures for maintaining the mice and for isolation of acini and ducts followed NIH guidelines and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of UT Southwestern Medical Center. Acini and duct fragments were isolated from the pancreas of 25–35g wild-type and Trpc1−/− mice by limited collagenase digestion as described previously (3, 11). After isolation, the acini were washed and re-suspended in solution A containing (140 mM NaCl, 10 mM glucose, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM CaCl2, pH7.4), 0.02% soybean-trypsin inhibitor and 0.1% bovine serum albumin and kept on ice until use.

To prepare single acinar cells, the pancreas was digested with collagenase and treated with trypsin-EDTA as described before (7). Briefly, the minced pancreas was incubated in solution A containing 4 mg/15 ml collagenase P for 5 min at 37 °C. The digest was washed with Ca2+- and Mg2+-free PBS and treated for 2 min at 37 °C with 0.05% trypsin-EDTA solution, washed with solution A, and re-treated with the solution containing collagenase for 3–4 min at 37 °C. Finally, the cells were washed with solution A and kept on ice until use.

Sealed mouse parotid ducts were prepared by microdissection and culture of intralobular ducts, as detailed elsewhere (43, 45). In brief, the parotid glands from one mouse were injected with a mixture of 50U/ml collagenase, 400U/ml hyaluronidase, 0.2 mg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor and 2 mg/ml BSA in solution A and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. The media was replaced with fresh digestion media and the incubation continued for an additional 30 min. The partially digested tissue was minced, washed with DMEM (Sigma-Aldrich) and used to micro-dissect intralobular ducts. The ducts were cultured in DMEM in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator for 48–72 hours before use for Ca2+ measurements.

Analysis of Orai1 and STIM1 gene expression and treatment with dicer siRNA

Because of the limited amount of microdissected duct tissue, the efficiency of the siRNA probes was determined in a mouse keratinocytes cell line. After incubation with the siRNA probes for 48 hrs, RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini Kit from Qiagen. After synthesis of first-strand cDNA (SuperScript Preamplification System, Invitrogen), STIM1 and Orai1 mRNA were determined by RT-PCR with β-actin as a loading control. The optimal cycling protocol was determined to be 94°C for 1 minute, 50°C for 1 minute, and 72°C for 3 minute for 30–40 cycles. The dicer siRNA sequence of Orai1 used for most experiments was GGUCAAAGCCCUAGGAUUAGUCCAA and the SiRNA-STIM1 sequence was GGGCAAGGAUGUUAUAUUUGAACCA. The scrambled siRNA was CUUCCUCUCUUUCUCUCCCUUGUGA. Ducts were treated with siRNA as follows. After dissection, the ducts were incubated in 35-mm dishes containing 2 ml of DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. A mixture of 100 pmol siRNA diluted in 250 μl of Opti-MEM (Invitrogen), and 5 μl Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) was incubated for 20 min at room temperature and then diluted just before use with 250 μl of the same medium. The mixed solution containing the siRNA was added to the dish. After 4 hours, the medium was replaced with a fresh medium without the siRNA. After 24 hrs incubation with siRNA the ducts were cut in half to release the accumulated fluid and tension, in particular in ducts treated with scrambled siRNA. The transfected ducts were cultured for a total of 48–60 hours before Ca2+ measurement.

[Ca2+]i measurement

Pancreatic acini and parotid ducts were loaded with Fura2 by 30–45 min incubation with 3 μM Fura2/AM at room temperature and washed by perfusion with worm (37 °C) solution A for at least 10 min in the dark before fluorescence measurements. Fura-2 fluorescence was measured using dual excitation wavelengths of 340 and 380 nm, and all light emitted above 510 nm was collected and used to obtain the F340/F380 ratio. For the duct experiments, the emitted fluorescence was monitored using a PMT tube (Photon Technology International Inc., Birmingham, NJ) attached to an inverted microscope (Nikon). Fluorescence signals were obtained at 1 sec intervals and analyzed using Felix software (Photon Technology International Inc.). Ca2+ imaging of acini were performed with a Nikon imaging setup using a digital camera (Cascade, Photometrics) with a cutoff filter at 510 nm and analyzed with Metafluor (Universal Imaging). All results are presented as the 340/380 ratios or as Ca2+ levels when appropriate.

Immunolocalization

All experiments were done with isolated acini so that the effect of cell stimulation on the localization of Orai1 and STIM1 can be evaluated. For most experiments, isolated pancreatic acini were platted on glass coverslips for 5min at room temperature prior to fixation with cold (−20 °C) methanol. For staining of TRPC1 in pancreatic acini, the acini were fixed with 3% Paraformaldehyde and extracted with 0.05% tritonX-100 and parotid acini were fixed with Paraformaldehyde and extracted with cold MeOH. After fixation, immunostaining was performed as described previously (3, 11) using 1:200 dilution of the STIM1, Orai1, IP3R3, laminin and E-cadherin antibodies. Briefly, the acini were incubated with the primary antibodies overnight at 4°C and after washing unbound antibodies 3 times with blocking solution, the bound antibodies were detected with goat anti-rabbit IgG tagged with FITC (STIM1 and Orai1) and anti-mouse IgG tagged with Rhodamine (IP3R3 and E-cadherin). Images were collected with a Bio-Rad 1024 confocal microscope.

For co-staining of Orai1 and STIM1, the anti-STIM1 antibody was directly tagged with the Alexa Fluor® 647 fluorofore. For labeling, 1 μg of affinity purified anti-STIM1 antibody in PBS was added to 5 μl of the Zenon Alexa Fluor® 647 rabbit IgG labeling reagent (Invitrogen) and the mixture was incubated for 5 min at room temperature. The reaction was then quenched by the addition of 5 μl of the Zenon blocking reagent and incubation for 5 min at room temperature. Since this procedure did not work well with the anti-Orai1 antibody, the fixed acini were first incubated with the anti-Orai1 antibody overnight at 4°C and after washing unbound antibody 3 times with blocking solution, the bound Orai antibody was detected with goat anti-rabbit IgG tagged with FITC. The cells were then washed 4 times with PBS to remove excess secondary antibodies and the cells were incubated with the Alexa Fluor® 647-tagged STIM1 antibody complex for 2 hrs at R.T., washed 3 times with PBS and processed for viewing. Although the images were not as clean as those obtained by using polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies for the co-staining, the localization of STIM1 and Orai1 could be clearly distinguished. Images were collected with Olympus confocal microscope and analyzed using Fluoview10-ASW2.1 software.

Analysis of overlap

All overlaps were determined with ImagJ. Overlaps of Orai1 with IP3R3 and with E-cadherin were determined by applying background that isolated the staining at the plasma membrane region. To determine the overlaps of STIM1 with IP3R3 and with E-cadherin a mask was placed in the cell interior of the STIM1 images before determining the overlap. In addition, overlaps were determined only in cells in which STIM1 staining could be clearly resolved. Images were collected from 3–5 separate acinar preparations and the results are the averages from all experiments and are given as the mean±s.e.m of the number of cells analyzed.

Co-immunoprecipitation (IP) and Western blot

Cells and mice tissues were extracted with ice-cold lysis buffer (1×PBS containing 10 mM Na pyrophosphate, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM Na orthovanadate, 1% Triton X-100, and a protease inhibitors cocktail, pH 7.4). The extracts were incubated for 1 hr at 4 °C, cleared by centrifugation for 15-min at 14,000 rpm and incubated with the desired antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Sepharose beads were added for the last 4 hrs of the incubation, collected and washed 3 times with lysis buffer by centrifugation and the proteins were recovered by heating at 55 °C for 30 min in SDS sample buffer. Protein concentration in the extracts was measured by the Bradford method and proteins were analyzed for the co-IP indicated in the Figures.

Current measurement

Isolated pancreatic acinar cells were perfused with a bath solution containing (mM) 140 NaC1, 5 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2 and 10 Hepes (pH 7.4, with NaOH). The patch pipette resistance was 2–5 mega-ohms when it was filled with internal solution containing (mM) 140 NMDG-Cl, 1 MgCl2, 0.5 EGTA, 5 ATP, 10 HEPES (pH 7.3 with Tris) and sufficient CaCl2 to clamp Ca2+ at 100 nM. After obtaining a giga-seal the whole cell configuration was established by gentle sacking and voltage pulses. Then, the holding potential was switched from 0 to −60 mV and the current output from the patch clamp amplifier (Axopatch-200B; Axon Instruments) was filtered at 20 Hz, sampled at 1 kHz, and stored with a Digi-Data 1200 interface and pclamp 8.1 software (Axon Instruments). Current traces were analyzed by Origin 8 software.

Statistics

Results are given as mean ± SEM of the indicated number of experimentations. Statistical significance was determined by analysis of variance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health Grants DE12309 and DK38938 and by the NIH Intramural Research grants to S.M. I.S.A and Z01-ES-101684 to L.B.

Abbreviations

- STIM1

stromal interaction molecule 1

- IP3Rs

IP3 receptors; 2APB

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- SOCs

store-operated channels

- SERCA

sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase pumps

- co-IP

co-immunoprecipitation

- TRPC

transient receptor potential-canonical

Footnotes

All authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest to disclose

References

- 1.Kiselyov K, Wang X, Shin DM, Zang W, Muallem S. Calcium signaling complexes in microdomains of polarized secretory cells. Cell Calcium. 2006;40(5–6):451–459. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen OH, Tepikin AV. Polarized calcium signaling in exocrine gland cells. Annu Rev Physiol. 2008;70:273–299. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shin DM, Luo X, Wilkie TM, Miller LJ, Peck AB, Humphreys-Beher MG, Muallem S. Polarized expression of G protein-coupled receptors and an all-or-none discharge of Ca2+ pools at initiation sites of [Ca2+]i waves in polarized exocrine cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(47):44146–44156. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105203200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee MG, Xu X, Zeng W, Diaz J, Wojcikiewicz RJ, Kuo TH, Wuytack F, Racymaekers L, Muallem S. Polarized expression of Ca2+ channels in pancreatic and salivary gland cells. Correlation with initiation and propagation of [Ca2+]i waves. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(25):15765–15770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.15765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yule DI, Ernst SA, Ohnishi H, Wojcikiewicz RJ. Evidence that zymogen granules are not a physiologically relevant calcium pool. Defining the distribution of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors in pancreatic acinar cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(14):9093–9098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nathanson MH, Fallon MB, Padfield PJ, Maranto AR. Localization of the type 3 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor in the Ca2+ wave trigger zone of pancreatic acinar cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(7):4693–4696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JY, Zeng W, Kiselyov K, Yuan JP, Dehoff MH, Mikoshiba K, Worley PF, Muallem S. Homer 1 mediates store- and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor-dependent translocation and retrieval of TRPC3 to the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(43):32540–32549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602496200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bandyopadhyay BC, Swaim WD, Liu X, Redman RS, Patterson RL, Ambudkar IS. Apical localization of a functional TRPC3/TRPC6-Ca2+-signaling complex in polarized epithelial cells. Role in apical Ca2+ influx. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(13):12908–12916. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410013200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao XS, Shin DM, Liu LH, Shull GE, Muallem S. Plasticity and adaptation of Ca2+ signaling and Ca2+-dependent exocytosis in SERCA2(+/−) mice. Embo J. 2001;20(11):2680–2689. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.11.2680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee MG, Xu X, Zeng W, Diaz J, Kuo TH, Wuytack F, Racymaekers L, Muallem S. Polarized expression of Ca2+ pumps in pancreatic and salivary gland cells. Role in initiation and propagation of [Ca2+]i waves. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(25):15771–15776. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.15771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shin DM, Dehoff M, Luo X, Kang SH, Tu J, Nayak SK, Ross EM, Worley PF, Muallem S. Homer 2 tunes G protein-coupled receptors stimulus intensity by regulating RGS proteins and PLCbeta GAP activities. J Cell Biol. 2003;162(2):293–303. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200210109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berridge MJ, Bootman MD, Roderick HL. Calcium signalling: dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4(7):517–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parekh AB, Putney JW., Jr Store-operated calcium channels. Physiol Rev. 2005;85(2):757–810. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00057.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liou J, Kim ML, Heo WD, Jones JT, Myers JW, Ferrell JE, Jr, Meyer T. STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+-store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr Biol. 2005;15(13):1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roos J, DiGregorio PJ, Yeromin AV, Ohlsen K, Lioudyno M, Zhang S, Safrina O, Kozak JA, Wagner SL, Cahalan MD, Velicelebi G, Stauderman KA. STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store-operated Ca2+ channel function. J Cell Biol. 2005;169(3):435–445. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200502019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feske S, Gwack Y, Prakriya M, Srikanth S, Puppel SH, Tanasa B, Hogan PG, Lewis RS, Daly M, Rao A. A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature. 2006;441(7090):179–185. doi: 10.1038/nature04702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vig M, Peinelt C, Beck A, Koomoa DL, Rabah D, Koblan-Huberson M, Kraft S, Turner H, Fleig A, Penner R, Kinet JP. CRACM1 is a plasma membrane protein essential for store-operated Ca2+ entry. Science. 2006;312(5777):1220–1223. doi: 10.1126/science.1127883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang SL, Yeromin AV, Zhang XH, Yu Y, Safrina O, Penna A, Roos J, Stauderman KA, Cahalan MD. Genome-wide RNAi screen of Ca(2+) influx identifies genes that regulate Ca(2+) release-activated Ca(2+) channel activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(24):9357–9362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603161103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luik RM, Wu MM, Buchanan J, Lewis RS. The elementary unit of store-operated Ca2+ entry: local activation of CRAC channels by STIM1 at ER-plasma membrane junctions. J Cell Biol. 2006;174(6):815–825. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu MM, Buchanan J, Luik RM, Lewis RS. Ca2+ store depletion causes STIM1 to accumulate in ER regions closely associated with the plasma membrane. J Cell Biol. 2006;174(6):803–813. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Varnai P, Toth B, Toth DJ, Hunyady L, Balla T. Visualization and manipulation of plasma membrane-endoplasmic reticulum contact sites indicates the presence of additional molecular components within the STIM1-Orai1 Complex. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(40):29678–29690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704339200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee KP, Yuan JP, Hong JH, So I, Worley PF, Muallem S. An endoplasmic reticulum/plasma membrane junction: STIM1/Orai1/TRPCs. FEBS Lett. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.11.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liao Y, Erxleben C, Abramowitz J, Flockerzi V, Zhu MX, Armstrong DL, Birnbaumer L. Functional interactions among Orai1, TRPCs, and STIM1 suggest a STIM-regulated heteromeric Orai/TRPC model for SOCE/Icrac channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(8):2895–2900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712288105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ong HL, Cheng KT, Liu X, Bandyopadhyay BC, Paria BC, Soboloff J, Pani B, Gwack Y, Srikanth S, Singh BB, Gill DL, Ambudkar IS. Dynamic assembly of TRPC1-STIM1-Orai1 ternary complex is involved in store-operated calcium influx. Evidence for similarities in store-operated and calcium release-activated calcium channel components. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(12):9105–9116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608942200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yuan JP, Zeng W, Huang GN, Worley PF, Muallem S. STIM1 heteromultimerizes TRPC channels to determine their function as store-operated channels. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(6):636–645. doi: 10.1038/ncb1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuan JP, Zeng W, Dorwart MR, Choi YJ, Worley PF, Muallem S. SOAR and the polybasic STIM1 domains gate and regulate Orai channels. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11(3):337–343. doi: 10.1038/ncb1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park CY, Hoover PJ, Mullins FM, Bachhawat P, Covington ED, Raunser S, Walz T, Garcia KC, Dolmetsch RE, Lewis RS. STIM1 clusters and activates CRAC channels via direct binding of a cytosolic domain to Orai1. Cell. 2009;136(5):876–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang GN, Zeng W, Kim JY, Yuan JP, Han L, Muallem S, Worley PF. STIM1 carboxyl-terminus activates native SOC, I(crac) and TRPC1 channels. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8(9):1003–1010. doi: 10.1038/ncb1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeng W, Yuan JP, Kim MS, Choi YJ, Huang GN, Worley PF, Muallem S. STIM1 gates TRPC channels, but not Orai1, by electrostatic interaction. Mol Cell. 2008;32(3):439–448. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu X, Cheng KT, Bandyopadhyay BC, Pani B, Dietrich A, Paria BC, Swaim WD, Beech D, Yildrim E, Singh BB, Birnbaumer L, Ambudkar IS. Attenuation of store-operated Ca2+ current impairs salivary gland fluid secretion in TRPC1(−/−) mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(44):17542–17547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701254104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim MS, Hong JH, Li Q, Shin DM, Abramowitz J, Birnbaumer L, Muallem S. Deletion of TRPC3 in mice reduces store-operated Ca2+ influx and the severity of acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(4):1509–1517. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.07.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peinelt C, Vig M, Koomoa DL, Beck A, Nadler MJ, Koblan-Huberson M, Lis A, Fleig A, Penner R, Kinet JP. Amplification of CRAC current by STIM1 and CRACM1 (Orai1) Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8(7):771–773. doi: 10.1038/ncb1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lur G, Haynes LP, Prior IA, Gerasimenko OV, Feske S, Petersen OH, Burgoyne RD, Tepikin AV. Ribosome-free terminals of rough ER allow formation of STIM1 puncta and segregation of STIM1 from IP(3) receptors. Curr Biol. 2009;19(19):1648–1653. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.07.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCarl CA, Picard C, Khalil S, Kawasaki T, Rother J, Papolos A, Kutok J, Hivroz C, Ledeist F, Plogmann K, Ehl S, Notheis G, Albert MH, Belohradsky BH, Kirschner J, et al. ORAI1 deficiency and lack of store-operated Ca2+ entry cause immunodeficiency, myopathy, and ectodermal dysplasia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(6):1311–1318 . e1317. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skibinska-Kijek A, Wisniewska MB, Gruszczynska-Biegala J, Methner A, Kuznicki J. Immunolocalization of STIM1 in the mouse brain. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 2009;69(4):413–428. doi: 10.55782/ane-2009-1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Picard C, McCarl CA, Papolos A, Khalil S, Luthy K, Hivroz C, LeDeist F, Rieux-Laucat F, Rechavi G, Rao A, Fischer A, Feske S. STIM1 mutation associated with a syndrome of immunodeficiency and autoimmunity. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(19):1971–1980. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DeHaven WI, Smyth JT, Boyles RR, Bird GS, Putney JW., Jr Complex actions of 2-aminoethyldiphenyl borate on store-operated calcium entry. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(28):19265–19273. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801535200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tamarina NA, Kuznetsov A, Philipson LH. Reversible translocation of EYFP-tagged STIM1 is coupled to calcium influx in insulin secreting beta-cells. Cell Calcium. 2008;44(6):533–544. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peinelt C, Lis A, Beck A, Fleig A, Penner R. 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate directly facilitates and indirectly inhibits STIM1-dependent gating of CRAC channels. J Physiol. 2008;586(13):3061–3073. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.151365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kawasaki T, Lange I, Feske S. A minimal regulatory domain in the C terminus of STIM1 binds to and activates ORAI1 CRAC channels. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;385(1):49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lioudyno MI, Kozak JA, Penna A, Safrina O, Zhang SL, Sen D, Roos J, Stauderman KA, Cahalan MD. Orai1 and STIM1 move to the immunological synapse and are up-regulated during T cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(6):2011–2016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706122105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Srikanth S, Jung HJ, Ribalet B, Gwack Y. The intracellular loop of Orai1 plays a central role in fast inactivation of CRAC channels. J Biol Chem. 2009 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.072736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Y, Soyombo AA, Shcheynikov N, Zeng W, Dorwart M, Marino CR, Thomas PJ, Muallem S. Slc26a6 regulates CFTR activity in vivo to determine pancreatic duct HCO3- secretion: relevance to cystic fibrosis. EMBO J. 2006;25(21):5049–5057. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang D, Shcheynikov N, Zeng W, Ohana E, So I, Ando H, Mizutani A, Mikoshiba K, Muallem S. IRBIT coordinates epithelial fluid and HCO3- secretion by stimulating the transporters pNBC1 and CFTR in the murine pancreatic duct. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(1):193–202. doi: 10.1172/JCI36983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shcheynikov N, Yang D, Wang Y, Zeng W, Karniski LP, So I, Wall SM, Muallem S. The Slc26a4 transporter functions as an electroneutral Cl-/I-/HCO3-exchanger: role of Slc26a4 and Slc26a6 in I- and HCO3- secretion and in regulation of CFTR in the parotid duct. J Physiol. 2008;586(16):3813–3824. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.154468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murakami M, Yoshimura K, Sugiya H, Seo Y, Loffredo F, Riva A. Relationship of fluid and mucin secretion to morphological changes in the perfused rat submandibular gland. Eur J Morphol. 2002;40(4):203–207. doi: 10.1076/ejom.40.4.203.16691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Woodard GE, Lopez JJ, Jardin I, Salido GM, Rosado JA. TRPC3 regulates agonist-stimulated Ca2+ mobilization by mediating the interaction between type I inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor, RACK1 and Orai1. J Biol Chem. 2009 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.033605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Allbritton NL, Meyer T, Stryer L. Range of messenger action of calcium ion and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate. Science. 1992;258(5089):1812–1815. doi: 10.1126/science.1465619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Melvin JE, Yule D, Shuttleworth T, Begenisich T. Regulation of fluid and electrolyte secretion in salivary gland acinar cells. Annu Rev Physiol. 2005;67:445–469. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.041703.084745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheng KT, Liu X, Ong HL, Ambudkar IS. Functional requirement for Orai1 in store-operated TRPC1-STIM1 channels. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(19):12935–12940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800008200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim MS, Zeng W, Yuan J, Shin DM, Worley P, Muallem S. Native store-operated Ca2+ influx requires the channel function of Orai1 and TRPC1. J Biol Chem. 2009 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808097200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liao Y, Erxleben C, Yildirim E, Abramowitz J, Armstrong DL, Birnbaumer L. Orai proteins interact with TRPC channels and confer responsiveness to store depletion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(11):4682–4687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611692104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liao Y, Plummer NW, George MD, Abramowitz J, Zhu MX, Birnbaumer L. A role for Orai in TRPC-mediated Ca2+ entry suggests that a TRPC:Orai complex may mediate store and receptor operated Ca2+ entry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(9):3202–3206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813346106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.