Abstract

Neuropeptide Y is abundant in the mammalian brain and plays a prominent role in behaviors related to negative affect and alcohol. NPY suppresses anxiety-like behavior and alcohol-drinking behaviors in a wide array of rodent models, and also affects changes in these behaviors produced by fearful and stressful stimuli. Rats selectively bred for high alcohol preference (P rats) appear to be particularly sensitive to the behavioral effects of NPY. The dual purpose of the present investigation was to determine the effects of intraventricular NPY on [1] the acoustic startle reflex (ASR) of P rats in a high-anxiety setting and [2] social interaction behavior of P rats. In Experiment 1, P rats were either cycled through periods of long-term ethanol access and abstinence or they remained ethanol-naïve. Rats were injected with one of four NPY doses and tested for ASR before and after footshock stress. NPY suppressed ASR in all P rats regardless of shock condition or drinking history. In Experiment 2, rats received intraventricular infusion of one of four NPY doses and then were injected with either ethanol (0.75 g/kg) or saline and tested for social interaction. NPY increased social interaction in P rats even at doses that suppressed locomotor activity, regardless of ethanol dose. Suppression of anxiety-like and arousal behaviors by NPY in the present study confirm a role for NPY in alcohol-related behaviors in alcohol-preferring P rats.

Keywords: Alcohol-Preferring Rats, Neuropeptide Y, Alcohol Abstinence, Acoustic Startle Response, Social Interaction

Introduction

Neuropeptide Y (NPY) affects emotionality in rats in a wide array of animal models (Heilig et al., 1989, 1992; Sajdyk et al., 1999). In general, NPY has potent anxiolytic effects in rats that have been localized to the amygdala (Heilig et al., 1993; Sajdyk et al., 2002). NPY in the amygdala increases social interaction by rats, interpreted as a decrease in anxiety-like behavior (Sajdyk et al., 2002). NPY also blocks potentiation of the acoustic startle response (ASR) by a conditioned fear stimulus, but has not been shown to affect unconditioned ASR in rats (Broqua et al., 1995). More recently, it was reported that NPY blocks stress-induced reinstatement of alcohol-seeking behavior, an effect that was attributed to inhibitory effects in the amygdala (Cippitelli et al., 2010).

A wealth of evidence supports the notion that amygdalar NPY modulates alcohol drinking by rats. Whole-brain activation of NPY systems, either directly via NPY microinfusion or indirectly via antagonism of pre-synaptic Y2 autoreceptors, suppresses alcohol drinking by alcohol-dependent Wistar rats, but not in rats without a history of dependence (Badia-Elder et al., 2001; Rimondini et al., 2005; Slawecki et al., 2000; Thorsell et al., 2005a,b). Whole-brain NPY activation also suppresses alcohol drinking in alcohol-preferring (P) rats (Badia-Elder et al., 2001; Gilpin et al., 2003, 2005), and the magnitude and duration of this effect is augmented following one or more periods of imposed alcohol abstinence (Gilpin et al., 2003, 2005). The suppressive effects of NPY on alcohol drinking are also mediated by the amygdala (Gilpin et al., 2008a,b; Pandey et al., 2005; Primeaux et al., 2006; Thorsell et al., 2007). Recent data suggest that the ability of NPY to suppress alcohol drinking are mediated by its effects on inhibitory neuronal populations in that brain region (Gilpin et al., unpublished observations). Together, these results suggest that the effects of NPY on anxiety-like and alcohol-related behaviors are mediated by the amygdala, and that the underlying neural processes of these two effects may overlap. Because alcohol abstinence produces increases in anxiety-like behavior and sensitivity to external stressors (for example, see Valdez et al., 2002, 2003; Zhao et al., 2007), it is reasonable to hypothesize that the enhanced ability of NPY to suppress alcohol drinking during withdrawal/abstinence reflects enhanced anxiolytic effects of NPY during high-anxiety high-arousal withdrawal periods.

In the first experiment, acoustic startle response was used to measure both basal arousal and arousal following exposure to an acute stressor in P rats. All tests occurred in the presence of bright white light, because light enhances the acoustic startle effect in rats via an unconditioned anxiogenic effect, and this effect does not extinguish within or across test sessions (Walker and Davis, 1997). Animals were exposed to footshock stress prior to designated ASR sessions because footshock stress increases ASR, and this effect is mediated by brain structures associated with anxiety aspects of the startle response (Davis, 1989; Koch, 1999), and also because footshock stress effectively reinstates alcohol-seeking behavior (Lê, 2004). In the second experiment, P rats were tested for the effects of acute alcohol and NPY on social interaction behavior, a measure of anxiety-like behavior in rats. The present investigation sought to determine (1) the effects of protracted alcohol abstinence, alone and in combination with external stressors, on ASR in P rats, (2) the dose-dependent effects of NPY on ASR in P rats, and (3) the interaction effects of acute alcohol and NPY on anxiety-like behavior in P rats.

Materials and Methods

Experiment 1

Subjects

Subjects were 144 experimentally naïve female P rats (bred at the Indiana University School of Medicine) of the 56th generation of selective breeding that were between 8 and 11 weeks of age and weighed between 123–317 g (mean ± SEM = 219.91 ± 3.05) at the start of ethanol exposure. Female P rats were used because they, like male P rats, show heightened anxiety-like behavior relative to alcohol-non-preferring (NP) rats (Stewart et al., 1993) and also exhibit decreases in alcohol consumption following intracerebral NPY infusion (Badia-Elder et al., 2001; Gilpin et al., 2003, 2005). All rats were individually housed in plastic tub-style cages in a vivarium maintained on a 12:12 hr light/dark cycle (lights off at 1400 hrs). Food (Lab Diet 5001, PMI Nutrition International Inc., Brentwood, MO) and water were available ad libitum at all times except where otherwise stated. All procedures were reviewed in advance by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and also met the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Procedure

Baseline Period for P Rats with Ethanol Access

A single group of P rats was given 6 weeks of continuous (24hr/day) access to 15% (v/v) ethanol and water. During this time, the side on which the ethanol bottle was placed was alternated daily. On days 22 and 23 of the baseline drinking period, rats were deprived of water (forced ethanol self-administration in order to optimize ethanol drinking) except during the 30-minute period when ethanol bottles were weighed. Following the 6-week drinking period, rats underwent cycles of ethanol access and imposed ethanol abstinence as described below. This group was designated the abstinence (ABST) group (n=92). A second group of ethanol-naïve (NAÏVE) rats (n=92) was matched for age with rats in the ABST group but never received ethanol.

ABST Group

Following 6 weeks of ethanol access, rats underwent a 14-day period with no ethanol (abstinence period 1), 14 days with ethanol (reinstatement period 1), and 14 more days with no ethanol (abstinence period 2). Fluid intakes from the final 7 days of the initial 6-week drinking period were used as baseline for comparison with fluid intakes upon subsequent reinstatement of ethanol. Fluid intake from the final 6 days of reinstatement period 1 were used to assign rats to one of 4 NPY dose groups matched for ethanol intake (g ethanol/kg body weight/day) to be tested for acoustic startle (see below). Stereotaxic surgeries were conducted during the first three days of abstinence period 2.

During days 9–13 of abstinence period 2, sham infusions (rats treated as if receiving infusion but nothing infused) were implemented daily at 1400 hrs to acclimate the rats to the infusion procedure. On the 14th day of abstinence period 2, immediately preceding acoustic startle testing, rats received ICV infusions of either aCSF (5.0 μl) (Plasma-Lyte [Electrolyte] Solution, Baxter, Deerfield, IL) or one of three doses (2.5, 5.0, or 10.0 μg/5.0 μl aCSF) of NPY (Porcine) (American Peptide Company, Sunnyvale, CA) according to prior group divisions based on ethanol intake. Several days following testing, rats were euthanized, their brains removed, and the location and patency of cannulae verified.

NAÏVE Group

An equal number of P rats were matched for age and weight with the ABST group. Rats were treated in an identical manner as P rats in the ABST group except that they remained ethanol-naïve for the duration of the experiment. Rats underwent stereotaxic surgeries and sham infusions, and were infused with either aCSF (5.0 μl) or one of four doses (2.5, 5.0, 10.0 μg/5.0 μl aCSF) of NPY prior to acoustic startle testing, in parallel with the ABST group.

Acoustic Startle Response Testing

Acoustic startle response testing was conducted with a commercial startle reflex system (S-R Lab; San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA). The sound-attenuated test chamber included an exhaust fan, a sound source, and an internal light that was always on during testing. Inside the test chamber, a single Plexiglas rodent cylinder (8.7 cm internal diameter) sat on a 12.5 × 25.5 cm Plexiglas stand. The acoustic startle response was transduced by a piezoelectric accelerometer mounted below the Plexiglas stand and was converted into arbitrary units by a personal computer program. Prior to testing, an S-R calibrator tube was used to calibrate the units to a sensitivity of 250 arbitrary units, since this calibration level prevents floor and ceiling effects in adult P rats (Bell et al., 2003). Data was sampled at 1kHZ for 100 milliseconds (ms) starting at the onset of each startle stimulus. The S-R Lab software program provided start values, maximum and average ASR trial values, as well as latency (ms) to reach the maximum trial value.

On day 14 of abstinence period 2, rats were infused with one of four NPY doses as described above, and then placed in a clean plastic cage for a 10-min interim period. Following this interim period, animals were placed in the rodent cylinder within the startle chamber. The test session was preceded by a 5-min habituation period during which 70 dB of background white noise was present. This background white noise was also present throughout the test session. The test session consisted of 31 trials with startle stimuli of four different decibel levels. During each of the 31 trials, a 750-ms burst of either 70 dB (background only), 95 dB, 105 dB, or 115 dB white noise was presented. The startle response of the rat was recorded for each of the first 100 ms of each trial. The main dependent variable, average ASR, was simply an average of these 100 (one per ms) response outputs. This range of startle stimuli is able to detect differences in threshold acoustic startle responses since a 90 dB acoustic stimulus does not elicit a startle response in normal adult P rats (Jones et al., 2000).

The 95 dB and 115 dB stimuli were each presented 8 times, the 105 dB stimulus was presented 9 times, and the background 70 dB stimulus was “presented” 6 times. Since rats exhibit highly variable responses during the initial trials of ASR test sessions, only the final 6 trials at each decibel level (all 6 trials at 70 dB) were averaged to provide a single data point for each rat at each decibel level and only these data were included in analyses. Trials were presented in a pseudo-Latin square design, where each decibel level preceded all other decibel levels an equal number of times (in the span of 24 trials included in data analysis). Trials were separated by a 20-s fixed intertrial interval. The rodent cylinder was cleaned between all test sessions.

Following the first test session (basal arousal test), rats were exposed to inescapable footshock stress (see below) for a 10-min period and once again placed in the rodent cylinder within the startle chamber. Rats were then re-tested (stress-induced arousal test) for acoustic startle response exactly as described above. Following the second test session, rats were returned to their clean home cage, given ad libitum access to food and water, and returned to the colony room.

Inescapable Footshock Stress

Immediately following the end of the first ASR test session, rats were moved to Habitest operant cages (Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA) with dimensions of approximately 26 cm L × 29 cm W × 29 cm H. The floor consisted of 16 parallel metal rods that were connected to an electric shock generator (Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA). There were no active levers or light present in the chamber. P rats were administered 10 minutes of intermittent footshock (0.8 mA; 0.5 s on) stress. A series of 20 footshocks were separated by variable time intervals of 10 s, 50 s, and 30 s, in that order. Therefore, footshock sessions consisted of 20 footshock deliveries over a period of 10 minutes with a mean intershock interval of 30 s. Following completion of the 10-minute session, rats were removed from the operant chambers and returned to acoustic startle test boxes for the stress-induced anxiety test described above. Operant chambers were always cleaned between shock sessions.

Experiment 2

Subjects

Subjects were 38 experimentally naïve female P rats (bred at the Indiana University School of Medicine) of the 56th generation of selective breeding that were approximately 8 weeks of age at the time of surgery. All rats were individually housed in plastic tub-style cages in a vivarium maintained on a 12:12 hr light/dark cycle (lights off at 1400 hrs). Food (Lab Diet 5001, PMI Nutrition International Inc., Brentwood, MO) and water were available ad libitum at all times.

Procedure

One week after surgical implantation of unilateral cannulae in the lateral ventricles, all rats underwent 2 consecutive days of sham infusions, during which they were handled as though being infused, but with no injector inserted into the cannulae. On the second day of sham infusions, 30 min following sham infusion, rats were placed alone into the social interaction apparatus for a 5-min habituation session. The social interaction apparatus (36 in L × 36 in W × 12 in H) was an open chamber with black floor and walls, and the floor was divided by yellow lines into a 6 × 6 grid of 36 in2 squares, used to count line crossings as a measure of activity.

On the day following the two sham infusion days, rats were infused (see General Methods) with either aCSF (5.0 μl) or one of three doses (2.5, 5.0, 10.0 μg/5.0 μl) of NPY (porcine; American Peptide Company, Sunnyvale, CA), and then immediately injected with ethanol (0.75 g/kg, i.p.) or an equivalent volume of saline (3 ml/kg). Thirty minutes after infusion, rats were tested for social interaction. Rats were placed into the social interaction apparatus with a partner rat of the same line, gender and body weight. Partner rats were housed under similar conditions and had never previously encountered any of the experimental rats. Each social interaction test session lasted 5 minutes and was recorded by a video camera mounted on the ceiling directly above the center of the chamber. Subsequently, a person blind to treatment conditions scored the time (seconds) experimental rats spent interacting (i.e., making physical contact, grooming, sniffing, crawling upon, etc.) with the partner rat, as well as locomotor activity (line crossings) of experimental rats. Social interaction by the experimental rat was only scored when the experimental rat played an active role in the interaction with the partner rat.

General Methods

Stereotaxic Surgery

Surgical implantation of intracerebroventricular cannulae was conducted using aseptic procedures as previously described (Badia-Elder et al., 2001), with the exception that rats were anesthetized via inhalation of isoflourane (IsoFlo, Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL) before and during surgery. The stereotaxic coordinates were adjusted to accommodate the smaller female rats used in the present study (AP-1.0, ML±1.5, DV- 3.8). At the completion of all experimental manipulations, anatomic localization was confirmed after euthanization. Following euthanization, a 1% solution of bromphenol blue dye in aCSF (5.0 μl) was injected into the ventricles. The brain was immediately removed, sliced, and placement was verified in a procedure that was blind to the treatment histories of the animals.

Microinfusions

A Harvard 33 microinfusion pump was used for all drug infusions at a rate of 2.5 μl/minute for a period of two minutes, and the injection cannula was left in the guide cannula for one additional minute to allow for adequate diffusion of the solution. Infusions were delivered to the cannula via polyethylene tubing (PE 50) that was connected to a Hamilton 25 μl syringe. Rats were placed in a clean plastic cage, where water and food were available ad libitum, directly following acoustic startle testing.

Data Analysis

In Experiment 1, fluid consumption was determined by weighing bottles daily at 1400 hrs, just before the start of the dark cycle. Ethanol intake (ml and g/kg), ethanol preference (ethanol:total fluid [E:T]) ratio, and total fluid intake (ml) by ABST rats during baseline and reinstatement period 1 were analyzed using one-way repeated-measures analyses of variance (RM ANOVA).

Average startle amplitudes were omitted for individual ASR trials in which rats exhibited start values (response amplitude during 1st millisecond of acoustic sound) above 10. Also, data from 115-dB trials were used to determine outliers (n=4 ABST rats; n=3 NAÏVE rats), since data was the most variable at this decibel level. Outlier values were defined as those values whose distance from the nearest quartile was greater than 1.5 times the interquartile range. If a rat was determined to have outlier data during 115-dB trials under a certain shock condition, then data for that rat at all decibel levels under the same shock condition (but not necessarily the other shock condition) were excluded from data analyses. For example, if average startle amplitude data from basal, but not post-shock, 115-dB trials for a given rat were outlier data, then data for that rat was excluded from analyses for all decibels in the basal ASR condition.

Average startle amplitude data were analyzed using a four-way (ethanol history × NPY dose × shock condition × decibel level) RM ANOVA, with shock condition and decibel level as the repeated-measures factors. The number of rats in each treatment group for ASR analyses was as follows: ABST 10.0 μg (n=17), ABST 5.0 μg (n=15), ABST 2.5 μg (n=18), ABST aCSF (n=20), NAÏVE 10.0 μg (n=18), NAÏVE 5.0 μg (n=18), NAÏVE 2.5 μg (n=17), NAÏVE aCSF (n=21).

In Experiment 2, social interaction time (seconds) and activity (line crossings) were analyzed with 2-way (NPY Dose X Ethanol Dose) between-subjects ANOVAs. One rat was excluded from analyses because its social interaction datum was determined to be an outlier (distance to nearest data point > 1.5 × interquartile range). For Experiments 1 and 2, all post-hoc analyses were conducted using Bonferroni multiple comparison tests, and in all cases, significance was determined at p<0.05.

Results

Experiment 1

Alcohol Drinking by P Rats

A one-way RM ANOVA revealed significant increases in ethanol consumption (ml), F(4,351)=79.71, p<0.001, ethanol intake (g/kg), F(4,351)=62.35, p<0.001, and ethanol preference (E:T), F(4,351)=109.22, p<0.001, upon reinstatement, indicative of an alcohol deprivation effect (Figure 1). Bonferroni post-hoc analyses revealed that these increases lasted through day four of reinstatement (p<0.001 in all cases). A compensatory decrease in water intake (ml), F(4,352)=98.73, p<0.001, lasted through day four of reinstatement (p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Mean (± SEM) ethanol intake (g/kg; closed circles) and ethanol preference (E:T; open circles) by P rats during the final 7 days of the six-week baseline drinking period and also during the 14 days ethanol access following the first imposed abstinence period. * p<0.001 significant difference from baseline for ethanol intake (g/kg) and ethanol preference.

Acoustic Startle Response in P Rats

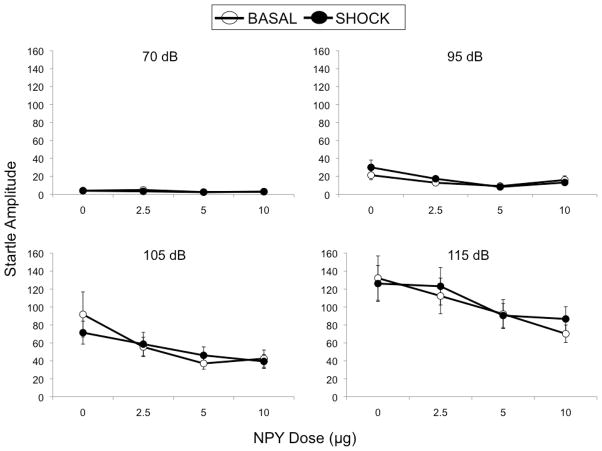

Figures 2 and 3 show pre- and post-shock acoustic startle responding in alcohol-naïve and alcohol-abstinent P rats, respectively, on day 14 of abstinence period 2. A 4-way (ethanol history × NPY dose × shock condition × decibel level) RM ANOVA yielded a significant effect of NPY, F(3,122)=6.36, p<0.001, on ASR amplitude. Bonferroni post-hoc analyses revealed that rats infused with any dose of NPY (2.5, 5.0, 10.0 μg) exhibited significantly lower ASR amplitudes than aCSF controls (p<0.03 in all cases). There was also a significant effect of decibel level, F(3,366)=291.03, p<0.001, on ASR amplitude. Bonferroni post-hoc analyses revealed that higher decibel levels produced greater ASR amplitudes and that amplitudes for all decibel levels differed significantly from amplitudes for all other decibel levels (p<0.01 in all cases). Finally, there was a significant interaction effect of NPY dose and decibel level, F(9,366)=4.14, p<0.001, on ASR amplitude. Bonferroni post-hoc analyses revealed that, during 105-dB and 115-dB trials, rats infused with any dose of NPY (2.5, 5.0, 10.0 μg) exhibited significantly lower ASR amplitudes than aCSF controls (p<0.001 in all cases). There were no effects of NPY on ASR amplitudes during 70-dB and 95-dB trials. There was no effect of shock or ethanol history on ASR amplitudes, nor were there any three-way or four-way interaction effects on ASR amplitudes (p>0.05 in all cases).

Figure 2.

Mean (± SEM) amplitude (arbitrary units) of acoustic startle response by alcohol-naïve P rats preceding (open circles) and following (closed circles) footshock on day 14 of abstinence period 2. Data represent the average of the final 6 trials in the session at the 70 dB (upper left panel), 95 dB (upper right panel), 105 dB (lower left panel), and 115 dB (lower right panel) acoustic levels.

Figure 3.

Mean (± SEM) amplitude (arbitrary units) of acoustic startle response by alcohol-abstinent P rats preceding (open circles) and following (closed circles) footshock on day 14 of abstinence period 2. Data represent the average of the final 6 trials in the session at the 70 dB (upper left panel), 95 dB (upper right panel), 105 dB (lower left panel), and 115 dB (lower right panel) acoustic levels.

Experiment 2

Social Interaction in P Rats

Social interaction by the experimental rat was only scored when the experimental rat played an active role in the interaction with the partner rat. A two-way (NPY dose × ethanol dose) ANOVA revealed a significant effect of NPY dose on social interaction time, F(3,29)=3.41, p=0.031 (Figure 4). Bonferroni post hoc analysis revealed that the 10.0 μg dose of NPY significantly increased social interaction time relative to vehicle (p<0.05). The 5.0 μg dose also produced a tendency (p=0.09) toward an increase in social interaction time.

Figure 4.

Mean (± SEM) time (seconds) of social interaction by P rats injected i.p. with either 0.75 g/kg ethanol (closed circles) or saline (open circles) and infused with one of four NPY doses prior to testing. NPY increased social interaction time in P rats, even at doses that decreased locomotor activity (data not shown).

A separate two-way (NPY dose × ethanol dose) ANOVA revealed a significant effect of NPY dose on locomotor activity, F(3,29)=6.08, p<0.05 (Table 1). Bonferroni post hoc analysis revealed that NPY significantly reduced activity at the 5.0 μg and 10.0 μg doses (p<0.01 in both cases) as compared to vehicle (data not shown). There were no NPY-ethanol interaction effects on social interaction time or locomotor activity. Furthermore, there was no correlation between locomotor activity and social interaction scores for individual rats, r(36)=−0.11, p>0.05).

Table 1.

Mean (± SEM) line crossings for P rats injected with either ethanol (0.75 g/kg, i.p.) or saline (3 ml/kg) and infused ICV with one of four NPY doses (0, 2.5, 5, 10 μg).

| Saline | Ethanol | |

|---|---|---|

| NPY Dose | ||

| 0.0 μg | 167.20 (20.85) | 176.20 (20.43) |

| 2.5 μg | 108.67 (30.84) | 143.17 (11.71) |

| 5.0 μg | 100.20 (31.55) | 87.00 (23.48) |

| 10.0 μg | 83.50 (49.05) | 92.60 (14.83) |

Discussion

The results of the present study show that intraventricular NPY reduces arousal and anxiety-like behavior in P rats. In Experiment 1, NPY suppressed the acoustic startle reflex (i.e., arousal) in the presence of bright light (anxiogenic) conditions in P rats. In Experiment 2, NPY increased social interaction (i.e., decreased anxiety-like behavior) by P rats, even at doses that produced decreases in locomotor activity.

Rats of the ABST group were tested for acoustic startle reflex 14 days into the second abstinence period and alcohol-naïve controls were tested at a parallel time point. All rats were infused with one of four NPY doses and tested for ASR (arousal) both preceding (basal ASR) and following (post-stress ASR) exposure to inescapable unpredictable footshock. NPY produced a global and dose-dependent suppression of arousal in P rats, an effect mainly attributable to the effects of NPY on ASR at the highest decibel levels. There was an indication that the lowest NPY dose may have been more effective in reducing startle in alcohol-abstinent P rats, especially following stress, relative to alcohol-naïve controls, and those data may warrant further investigation.

Previous studies support the notion that cycles of chronic alcohol exposure and abstinence produce an upregulation of NPY function in multiple brain regions that mediate multiple behaviors. Cycles of alcohol exposure and abstinence enhance the suppressive effects of intraventricular NPY on alcohol drinking (Gilpin et al., 2003, 2005) and the orexigenic effects of NPY (Gilpin et al., 2005). Furthermore, intraventricular administration of BIIE0246, a Y2 autoreceptor antagonist, produces stronger sedative effects and suppressive effects on ethanol drinking following cycles of high-dose alcohol exposure and abstinence (Rimondini et al., 2005). In the present investigation, P rats consumed substantial daily quantities of ethanol (6–9 g/kg/day for 8 weeks) that produce BALs of 50–200 mg/dl (Bell et al., 2006; Murphy et al., 1986; Rodd-Henricks et al., 2001), reduce bicuculline-induced seizure thresholds, and increase anxiety-like behavior as measured on the elevated plus-maze and in the social interaction test (Kampov-Polevoy et al., 2000).

In the current investigation, intraventricular NPY increased social interaction by P rats, indicative of a decrease in anxiety-like behavior. This result confirms past findings that intraventricular NPY suppresses anxiety-like behavior in outbred rats (Heilig et al., 1989) and rats selectively bred for high alcohol preference (Badia-Elder et al., 2003). A multitude of prior studies have used the social interaction test to establish a role for amygdalar NPY in anxiety-like behavior in rats. NPY infusion into the BLA suppresses basal anxiety-like behavior and blocks stress-induced increases in anxiety-like behavior as measured by the social interaction test, effects that have been attributed to the activity of both Y1 and Y2 receptors (Sajdyk et al., 1999, 2002). Repeated prophylactic NPY infusions into the BLA produce long-term decreases in anxiety-like behavior and resistance to the anxiogenic effects of stress (Sajdyk et al., 2008), similar to the long-term ability of repeated prophylactic NPY administration to block excessive drinking associated with the transition to alcohol dependence (unpublished observations from Gilpin NW and Koob GF).

The amygdala mediates the anxiolytic effects of NPY (Heilig et al., 1993; Sajdyk et al., 2002) and the suppressive effects of NPY on ethanol drinking (Gilpin et al., 2008a,b; Pandey et al., 2005; Thorsell et al., 2007), and also contributes to the acoustic startle response in rats (Davis et al., 2010). The ability of amygdalar NPY to suppress alcohol drinking is augmented in rats that have undergone multiple cycles of chronic alcohol exposure (Gilpin et al., 2008a; Thorsell et al., 2007), and also in rats that exhibit innately high levels of anxiety-like behavior (Primeaux et al., 2006) or are dependent on alcohol (Gilpin et al., 2008b). Recent data suggest that NPY in the central amygdala (CeA) modulates alcohol consumption by suppressing GABA release from interneurons in that region, specifically via actions at Y2 receptors, causing a net disinhibition of GABA projections out of the CeA to downstream regions (Gilpin et al., unpublished observations). These latter findings agree with evidence that NPY blocks stress-induced reinstatement of alcohol-seeking behavior via activation of inhibitory neuronal populations in the extended amygdala (Cippitelli et al., 2010), and are also confirmed by previous findings that Y2 receptors modulate alcohol consumption (Rimondini et al., 2005) and that amygdalar Y2 receptors affect anxiety-like behaviors in rats (Sajdyk et al., 2002; Tasan et al., 2010).

Alcohol drinking history did not affect the acoustic startle response in P rats in the present investigation, nor was there an alcohol × NPY interaction effect on social interaction in P rats. The suppressive effect of NPY on alcohol drinking is often attributed to its anxiolytic effects (Valdez and Koob, 2004), mainly because NPY effects on alcohol drinking and anxiety-like behavior are both mediated by amygdala (Gilpin et al., 2008a,b; Heilig et al., 1993; Sajdyk et al., 2002). However, the ability of NPY to suppress anxiety-related behaviors in rats is not contingent on prior alcohol exposure (Badia-Elder et al., 2003; Heilig et al., 1993; Sajdyk et al., 2002). Although rats selectively bred for high alcohol preference do appear to exhibit heightened sensitivity to the behavioral effects of NPY, especially following multiple withdrawals, the acoustic startle reflex test may not be the ideal measure for detecting NPY-alcohol interactions 14 days into abstinence (as tested in the present investigation). Past studies have reported signs of alcohol dependence in P rats following 6 weeks of continuous alcohol access (Kampov-Polevoy et al., 2000), but those withdrawal signs were measured 5 hours into acute withdrawal rather than 14 days into abstinence. Indeed, it appears that chronic alcohol vapor-induced increases in alcohol drinking by P rats dissipate 14 days into abstinence (Gilpin et al., 2008c). Therefore, although the anxiolytic effects of NPY are thought to be important for the ability of NPY to suppress alcohol drinking in rats, these results indicate that the anxiolytic effects of NPY do not appear to depend on prior alcohol exposure.

There was no clear effect of acute stress exposure on the acoustic startle response in P rats in this study. Past studies have shown that the effects of acute stressors on particular behaviors may be augmented during alcohol abstinence. Rats exposed to mild restraint stress 3 days into abstinence exhibit decreases in social interaction (i.e. increased anxiety) relative to stressed alcohol-naïve controls and also relative to non-stressed alcohol-abstinent controls (Breese et al., 2005). Similarly, rats exposed to mild restraint stress 6 weeks into protracted abstinence exhibit marked increases in anxiety-like behavior, as measured by the elevated plus-maze, relative to stressed alcohol-naïve controls and also relative to non-stressed alcohol-abstinent controls (Valdez et al., 2003). There were no stress-abstinence interaction effects on the acoustic startle reflex, which is likely attributable to the numerous differences between the present investigation and those prior studies, including dependent variable (ASR vs. social interaction and plus-maze), stressor (footshock vs. restraint), alcohol exposure protocol (homecage two-bottle choice vs. liquid diet), and rat strain (P rats vs. outbred rats).

In summary, the present investigation shows that intraventricular NPY suppresses the acoustic startle reflex in alcohol-preferring P rats. These data also show that intraventricular NPY increases social interaction (decreases anxiety-like behavior) in alcohol-preferring P rats, even at doses that suppress locomotor activity. Data from previous studies suggest that amygdalar NPY is an important regulator of negative affective states and alcohol-related behaviors, especially in subpopulations that exhibit increased susceptibility to pathological alcohol drinking, such as those selected for high alcohol preference and those exposed to cycles of high-dose alcohol exposure and abstinence.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. James Murphy, Charles Goodlett and Susan Swithers for their valuable insights into the contents of this paper. This investigation was supported by National Institutes of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grants, AA12857, AA07611, and AA10722.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Badia-Elder NE, Stewart RB, Powrozek TA, Murphy JM, Li T-K. Effects of neuropeptide Y on sucrose and ethanol intake and on the elevated plus maze test of anxiety in high alcohol drinking (HAD) and low alcohol drinking (LAD) rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:894–899. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000071929.17974.DA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badia-Elder NE, Stewart RB, Powrozek TA, Roy KF, Murphy JM, Li T-K. Effect of neuropeptide Y (NPY) on oral ethanol intake in Wistar, alcohol-preferring (P), and –nonpreferring (NP) rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:386–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RL, Rodd ZA, Hsu CC, Lumeng L, Murphy JM, McBride WJ. Amphetamine-modified acoustic startle responding and prepulse inhibition in adult and adolescent alcohol-preferring and -nonpreferring rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;75:163–171. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(03)00069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RL, Rodd ZA, Sable HJK, Schultz JA, Hsu CC, Lumeng L, et al. Daily patterns of ethanol drinking in peri-adolescent and adult alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2006;83:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breese GR, Overstreet DH, Knapp DJ. Conceptual framework for the etiology of alcoholism: A “kindling”/stress hypothesis. Psychopharmacol. 2005;178:367–80. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2016-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broqua P, Wettstein JG, Rocher MN, Gauthier-Martin B, Junien JL. Behavioral effects of neuropeptide receptor agonists in the elevated plus-maze and fear-potentiated startle procedure. Behav Pharmacol. 1995;6:215–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cippitelli A, Damadzic R, Hansson AC, Singley E, Sommer WH, Eskay R, Thorsell A, Heilig M. Neuropeptide Y (NPY) suppresses yohimbine-induced reinstatement of alcohol seeking. Psychopharmacol. 2010;208:417–426. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1741-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. Sensitization of the acoustic startle reflex by footshock. Behav Neurosci. 1989;103:495–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Walker DL, Miles L, Grillon C. Phasic vs sustained fear in rats and humans: role of the extended amygdala in fear vs anxiety. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;35:105–135. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin NW, Misra K, Koob GF. Neuropeptide Y in the central nucleus of the amygdala suppresses dependence-induced increases in alcohol drinking. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008b;90:475–480. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin NW, Richardson HN, Lumeng L, Koob GF. Dependence-induced alcohol drinking by alcohol-preferring (P) rats and outbred Wistar rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008c;32:1688–1696. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00678.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin NW, Stewart RB, Badia-Elder NE. Neuropeptide Y administration into the amygdala suppresses ethanol drinking in alcohol-preferring (P) rats following multiple deprivations. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008a;90:470–474. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin NW, Stewart RB, Murphy JM, Badia-Elder NE. Sensitized effects of neuropeptide Y on multiple ingestive behaviors in P rats following ethanol abstinence. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;81:740–749. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin NW, Stewart RB, Murphy JM, Li TK, Badia-Elder NE. Neuropeptide Y reduces oral ethanol intake in alcohol-preferring (P) rats following a period of imposed ethanol abstinence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:787–794. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000065723.93234.1D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilig M, McLeod S, Brot M, Heinrichs SC, Menzaghi F, Koob GF, Britton KT. Anxiolytic-like action of neuropeptide Y: mediation by Y1 receptors in amygdala, and dissociation from food intake effects. Neuropsychopharmacol. 1993;8:357–363. doi: 10.1038/npp.1993.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilig M, McLeod S, Koob GF, Britton KT. Anxiolytic-like effect of neuropeptide Y (NPY), but not other peptides in an operant conflict test. Regulat Pept. 1992;41:61–69. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(92)90514-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilig M, Soderpalm B, Engel JA, Widerlov E. Centrally administered neuropeptide Y (NPY) produces anxiolytic-like effects in animal anxiety models. Psychopharmacol. 1989;98:524–529. doi: 10.1007/BF00441953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AE, McBride WJ, Murphy JM, Lumeng L, Li TK, Shekhar A, McKinzie DL. Effects of ethanol on startle responding in alcohol-preferring and -nonpreferring rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;67:313–318. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00363-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampov-Polevoy AB, Matthews DB, Gause L, Morrow AL, Overstreet DH. P rats develop physical dependence on alcohol via voluntary drinking: changes in seizure thresholds, anxiety, and patterns of alcohol drinking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:278–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch M. The neurobiology of startle. Prog Neurobiol. 1999;59:107–28. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lê AD. Stress and relapse to alcohol: studies with the reinstatement procedure and alcohol deprivation effect (ADE). Paper presented at the meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism; Vancouver, B.C., Canada. June 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JM, Gatto GJ, Waller MB, McBride WJ, Lumeng L, Li TK. Effects of scheduled access on ethanol intake by the alcohol-preferring (P) line of rats. Alcohol. 1986;3:331–336. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(86)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey SC, Zhang H, Roy A, Xu T. Deficits in amygdaloid cAMP-responsive element-binding protein signaling play a role in genetic predisposition to anxiety and alcoholism. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2762–2773. doi: 10.1172/JCI24381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primeaux SD, Wilson SP, Bray GA, York DA, Wilson MA. Overexpression of neuropeptide Y in the central nucleus of the amygdala decreases ethanol self administration in “anxious” rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:791–801. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimondini R, Thorsell A, Heilig M. Suppression of ethanol self-administration by the neuropeptide Y (NPY) Y2 receptor antagonist BIIE0246: evidence for sensitization in rats with a history of dependence. Neurosci Lett. 2005;375:129–133. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.10.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd-Henricks ZA, Bell RL, Kuc KA, Murphy JM, McBride WJ, Lumeng L, Li TK. Effects of concurrent access to multiple ethanol concentrations and repeated deprivations on alcohol intake of alcohol-preferring rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1140–1150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajdyk TJ, Johnson PL, Lettermann RJ, Fitz SD, Dietrich A, Morin M, et al. Neuropeptide Y in the amygdala induces long-term resilience to stress-induced reductions in social responses but not hypothalamic–adrenal–pituitary axis activity or hyperthermia. J Neurosci. 2008;28:893–903. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0659-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajdyk TJ, Schober DA, Gehlert DR. Neuropeptide Y receptor subtypes in the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala modulate anxiogenic responses in rats. Neuropharmacol. 2002;43:1165–1172. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00234-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajdyk TJ, Vandergriff MG, Gehlert DR. Amygdalar neuropeptide Y Y1 receptors mediate the anxiolytic-like actions of neuropeptide Y in the social interaction test. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;368:143–147. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slawecki CJ, Betancourt M, Walpole T, Ehlers CL. Increases in sucrose consumption, but not ethanol consumption, following ICV NPY administration. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;66:591–594. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00215-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart RB, Gatto GJ, Lumeng L, Li TK, Murphy JM. Comparison of alcohol-preferring (P) and nonpreferring (NP) rats on tests of anxiety and for the anxiolytic effects of ethanol. Alcohol. 1993;10:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(93)90046-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasan RO, Nguyen NK, Weger S, Sartori SB, Singewald N, Heilbronn R, et al. The central and basolateral amygdala are critical sites of neuropeptide Y/Y2 receptor-mediated regulation of anxiety and depression. J Neurosci. 2010;30:6282–6290. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0430-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorsell A, Repunte-Canonigo V, O’Dell LE, Chen SA, King AR, Lekic D, et al. Viral vector-induced amygdala NPY overexpression reverses increased alcohol intake caused by repeated deprivations in Wistar rats. Brain. 2007;130:1330–1337. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorsell A, Slawecki CJ, Ehlers CL. Effects of neuropeptide Y on appetitive and consummatory behaviors associated with alcohol drinking in Wistar rats with a history of ethanol exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005a;229:584–590. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000160084.13148.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorsell A, Slawecki CJ, Ehlers CL. Effects of neuropeptide Y and corticotropin-releasing factor on ethanol intake in Wistar rats: interaction with chronic ethanol exposure. Behav Brain Res. 2005b;161:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez GR, Koob GF. Allostasis and dysregulation of corticotropin-releasing factor and neuropeptide Y systems: implications for the development of alcoholism. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;79:671–689. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez GR, Roberts AJ, Chan K, Davis H, Brennan M, Zorrilla EP, Koob GF. Increased ethanol self-administration and anxiety-like behavior during acute withdrawal and protracted abstinence: regulation by corticotropin-releasing factor. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:1494–1501. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000033120.51856.F0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez GR, Zorrilla EP, Roberts AJ, Koob GF. Antagonism of corticotropin-releasing factor attenuates the enhanced responsiveness to stress observed during protracted ethanol abstinence. Alcohol. 2003;29:55–60. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(03)00020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DL, Davis M. Anxiogenic effects of high illumination levels assessed with the acoustic startle paradigm. Biol Psych. 1997;42:461–471. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00441-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Weiss F, Zorrilla EP. Remission and resurgence of anxiety-like Behavior across protracted withdrawal stages in ethanol-dependent rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:1505–1515. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]