Abstract

Diabetes mellitus is generally treated with oral diabetic drugs and/or insulin. However, the morbidity and mortality associated with this condition increases over time, even in patients receiving intensive insulin treatment, and this is largely attributable to diabetic complications or the insulin therapy itself. Pancreas transplantation in humans was first conducted in 1966, since when there has been much debate regarding the legitimacy of this procedure. Technical refinements and the development of better immunosuppressants and better postoperative care have brought about marked improvements in patient and graft survival and a reduction in postoperative morbidity. Consequently, pancreas transplantation has become the curative treatment modality for diabetes, particularly for type I diabetes. An overview of pancreas transplantation is provided herein, covering the history of pancreas transplantation, indications for transplantation, cadaveric and living donors, surgical techniques, immunosuppressants, and outcome following pancreas transplantation. The impact of successful pancreas transplantation on the complications of diabetes will also be reviewed briefly.

Keywords: Pancreas, Transplantation, Diabetes

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus is a leading public health concern in oriental countries and around the world. According to the Centers for Disease Control, more than 15 million people in the United States, or 5.9% of the population, have diabetes and 798,000 new cases are diagnosed each year.1 The prevalence of diabetes in Korea is almost the same with the states as 5.92% of the population. It is estimated that the diabetic population is rapidly increasing by 10% each year.2

While hyperglycemia is the defining characteristic of diabetes, the underlying pathogenesis leading to hyperglycemia differs significantly among the various forms of the disease. Common to all is the presence of defects in insulin secretion and/or insulin action.

Type 1 diabetes occurs when the pancreatic beta cells are destroyed and the patient develops profound or absolute insulin deficiency. Nearly all cases are autoimmune in origin. This form of diabetes accounts for approximately 5% to 10% of diabetes. The disease most often appears in childhood, but patients of any age may present with type 1 diabetes.3 A mixture of genetic and environmental factors are believed to lead to the autoimmune destruction that causes type 1 diabetes. Over the past 10 years the incidence of type 1 diabetes has increased.4

Type 2 diabetes occurs as the result of defects in both insulin secretion and insulin action. This form of the disease represents about 90% of prevalent cases of diabetes. The incidence of type 2 diabetes in children has been dramatically increasing in recent years.5,6

Diabetes mellitus is associated with devastating complications that increase both the mortality and morbidity of those suffering from the disease.

Heart disease is the leading cause of diabetes related deaths and people with diabetes die from heart disease two to four times more often than people without diabetes. This is one of the leading cause of end stage renal disease in Korea.2

Excessive hyperglycemia is a major risk factor for the development of diabetic retinopathy.7 Diabetes is the leading cause of new blindness.8 But cataracts and glaucoma related to diabetes are also responsible for vision loss.

Foot ulcers that occur as a result of diabetic neuropathy are estimated to affect about 15% of all patients with diabetes at some point during their lifetime.9 In addition, approximately 85% of lower extremity amputations are proceded by a foot ulcer.10 In Korea, almost half (44.8%) of the people who had lower limb amputation were diabetic.2

The increased morbidity and mortality found in patients with diabetes is largely attributable to the complications. Because of its high prevalence and the severity of its associated complications, diabetes has become one of the costliest diseases to treat in Korea and Westernized countries.

Although and intensified insulin regimen improves glycosolated haemoglobin concentrations and reduces the rate of long-term complications, it does not prevent them.

The goal of pancreas transplantation is to safely restore normoglycaemia by the provision of sufficient β cell mass. Transplantation of a pancreas, unlike liver, lung, and heart, is not a life-saving operation but it improves quality of life because patients do not need to inject insulin on a daily basis or regularly monitor glucose concentrations with finger sticks, and hypoglycaemic unawareness is no longer a problem. The long-term advantages of this surgical procedure have to be balanced against the potential morbidity and mortality associated with diabetes, and the side effects from the long-term immunosuppression that is needed to prevent alloimmunity and autoimmune recurrence. The risk of immunosuppression is particularly relevant for recipients of pancreas transplant alone (PTA; unlike patients with uraemic diabetes who are also given a kidney transplant), since the only benefit of immune-suppression in this category is insulin free euglycaemia.11

HISTORY OF PANCREAS TRANSPLANTATION

Insulin independence in a type 1 diabetic was first achieved on December 17, 1966, when William Kelly and Richard Lillehei transplanted a duct ligated segmental pancreas graft simultaneously with a kidney from a cadaver donor into a 28-year-old uremic woman at the University of Minnesota.12

In the second pancreas 1966, Lillehei was the lead surgeon doing the donor's whole pancreas and attached duodenum transplanted extraperitoneally to the left iliac fossa in 32-year-old recipient.12,13

On November 24, 1971, the first pancreas transplant using urinary drainage via the native ureter was performed by Marvin Gliedman at Montefiore Hospital in New York.14 In 1973, Merkel reported a segmental PTA with end-to-side ductoenterostomy.15

In 1978, Dubernard et al.16 reported on a technique in which the pancreatic duct of the segmental pancreas graft was injected with neoprene, a synthetic polymer.

In 1983, Hans Sollinger at the University of Wisconsin reported on a bladder drainage technique of a segmental graft that over the next decade was the most used method for managing pancreatic exocrine secretions.17

Further Nghiem and Corry18 reported on a whole pancreaticoduodenal transplantation with a secure duodenocystotomy.

In 1984, Starzl et al.19 reintroduced the technique of enteric drained whole organ pancreaticoduodenal transplants as originally described by Lillehei.

From the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s, bladder drainage became the most common technique worldwide, because a decrease in urine amylase activity could be used as a sensitive, if nonspecific, marker of rejection.20-22 However late 1990s there was shift again from bladder to enteric drainage, in particular for simultaneous pancreas and kidney (SPK) transplants.23 Enteric drainage is a more physiologic way to drain pancreatic exocrine secretions, and improvements in antimicrobial and immunosuppressive therapy reduced the risks of complications as well as rejection. Addition, the chronic complications of bladder drainage (urinary tract infections, hematuria, acidosis, dehydration) led to the need for enteric conversion in 10% to 15% of bladder drained recipients.

In 1992, Rosenlof et al.24 From the University of Virginia and Shokouh-Amiri et al.25 from the University of Tennessee described the use of portal drainage at the junction of the recipient's superior and splenic veins in recipients of enteric drained whole organ pancreaticoduodenal transplants. Subsequently, Gaber et al.26 reported on a large series of cases.

Segmental transplant was primarily used with living donors (LDs). Pancreas transplants with LDs began at the University of Minnesota in the late 1970s and LD laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy was introduced in 2001 at the same center.27-29

INDICATION OF PANCREAS TRANSPLANTATION

1. Donor

1) Cadaveric donor

The criteria of selection for suitable vast majority of pancreas grafts are obtained from cadaver, heart-beating donors. Although pancreas grafts from non-heart-beating donors have been successfully transplanted, this practice has been extremely limited.30 Suitability of a cadaver pancreas donor is based on general criteria common to all organ procurements as well as on specific pancreas-related factors.

Complete, irreversible loss of brain function and brain stem function manifests clinically as complete apnea, brain stem areflexia, and cerebral unresponsiveness. The cause for the absence of clinical brain function must be known and must be irreversible.

The initial selection of a cadaver pancreas donor is based on ABO group compatibility and on a documented negative crossmatch. HLA matching is not critical for SPK transplants. For solitary pancreas transplants the degree of match is an important prognostic factor for graft survival.31 Therefore, for pancreas after kidney (PAK) or PTA transplants most centers require a minimum of three HLA antigen matches or, preferably, one match per HLA locus.

Further, the quality of the donor graft is key to the rate of early postoperative complications such as thrombosis, pancreatitis, infection, and leaks. Technical failures still account for a significant rate of pancreas graft loss,32 The following factors are associated with a lower quality of pancreas grafts and thus an increased incidence of technical complications.

Pancreas donor age requirements are, in general, more strict. Most centers require a minimum donor weight of 30 kg or above. Gruessner et al.33 in their review of 445 pancreas transplant performed in the cyclosporine era at the University of Minnesota, they found that donor age above 45 years was a significant risk factor for vascular thrombosis, intraabdominal infections, anastomotic or duodenal leaks, and relaparotomy.

The authors from Pittsburgh contended that the most important variable in determining suitability of a pancreas graft is inspection by an experienced pancreas transplant surgeon.34 Most experts agree that the direct examination of the graft is important.

It is safe to state that donors dying from cerebrovascular complications, especially those who are older and who have comorbid conditions, should be assessed carefully.

Hyperglycemia in the absence of a history of pancreatic endocrine insufficiency is often seen in brain-dead patients. Most transplant centers consider donor hyperglycemia a benign disorder; in the absence of a clinical history of diabetes.33,35,36

Even in the absence of direct trauma to the pancreas, increased serum amylase levels (greater than 110 UI/L) are observed in up to 40% of donors and may contraindicate donation.37 Isolated elevation of serum amylase levels without significant comorbidity does not appear to contraindicate pancreas donation.37,38

With modern organ preservation, based on flush and cold storage with University of Wisconsin solution, pancreas grafts can be safely transplanted up to 30 hours after procurement.39,40 However, increased incidence of vascular thrombosis were reported with prolonged cold ischemia.

The vast majority of pancreas transplant surgeons consider donor obesity to be at least a relative contraindication to donation. Grafts with fatty degeneration are widely considered more likely to develop posttransplant pancreatitis, thrombosis, and infection.

2) Living donor

Living donors for solitary pancreas transplants are now used if the recipient is highly sensitized (panel reactive antibody >80%) and has a low probability of receiving a cadaver graft; must avoid high dose immunosuppression; or has a nondiabetic identical twin or a 6-antigen-matched sibling.41

The social and psychological evaluations assess the donor's voluntarism and altruism as well as the dynamics of the donor recipient relationship.

Apart from the general medical workup, potential pancreas donors must also fulfill certain criteria and undergo testing specific to their pancreatic endocrine function. Related donors must be at least 10 years older than the age at which the intended recipient was diagnosed with diabetes mellitus. No other sibling or family members other than the recipient can be diabetic. Potential donors with a history of gestational diabetes are also excluded.42,43

Initial pancreas specific laboratory screening tests include serum amylase and lipase, fasting plasma glucose, and fasting hemoglobin (Hb) AIC determination. Part of their extensive metabolic evaluation, potential donors undergo oral glucose tolerance tests and studies to determine their insulin secretion and functional insulin secretory reserve.

Potential donors fast for at least 10 hours before undergoing an IV arginine stimulation test, followed 30 minutes later by either an IV glucose tolerance test or a glucose potentiation.

2. Recipient

Most pancreas transplants have been done in patients with type 1 diabetes who are absolutely β-cell deficient.

However, pancreas transplants have also been done in patients considered to have type 2 diabetes. The patient became insulin dependent even though C-peptide type was present pretransplant, indicating persistence of at least some endogenous β-cell function.44

Benefit of a transplant is obvious when the problems of diabetes clearly exceed the potential side effects of chronic immunosuppression.45 Patients with hypoglycemic unawareness with frequent reactions to exogenous insulin lead a dangerous existence.46

Patients with progressive secondary complications of diabetes are also destined for blindness, amputations, and kidney failure that exceeds the usual side effects of immunosuppression. Beta-cell replacement as early as possible is desirable.

The burden of modern diabetic management is dialysis like.41 Standard diabetic management entails at least four blood sugar determinations a day, with at least twice daily insulin injections and supplementary injections according to blood sugar levels.

In the Diabetes Control and Complication Trial, even in the intensive treatment arm under the most ideal conditions, 15% of the patients went on to develop secondary complications.7 Retinopathy, neuropathy, and nephropathy are at least as morbid, if not more so, than the side effects of chronic immunosuppression.

Diabetes per se is sufficient for a patient to opt for a β-cell transplant, accepting the risks of immunosuppression over those of diabetes.47 Certainly for patients with ongoing diabetic problems, the quality of life improves with β-cell replacement.

Pancreas transplant recipients can be divided into two broad classifications: those with nephropathy to such a degree that they also undergo a kidney transplant, either simultaneously or sequentially, and those, usually without end-stage renal disease, who undergo only a pancreas transplant.

The traditional categories are as follows: SPK transplant. PAK transplant. PTA. Kidney after pancreas (KAP) transplant.

In the SPK category, the most common scenario is for both organs to come from same cadaveric donor, with a small percentage being from a living donor. However, simultaneous cadaveric donor pancreas and living donor kidney transplants have also been done.

Living donor SPK transplant is the Cadillac option for uremic diabetic patients.47 As a pre-emptive transplant, it avoids dialysis and induces insulin independence with one operation and with the lowest rejection rate.

SURGICAL ASPECTS OF PANCREAS TRANSPLANTATION

1. Donor procedures

1) Cadaveric donor

Successful outcome of pancreas transplantation largely depends on the procuring surgeon's expertise.

It became obvious that perioperative coordination is essential, in particular when the pancreas and liver are procured by different teams.

A midline incision is made. After the falciform ligament is divided, the right colon is fully mobilized to expose the retroperitoneum, cava, aorta at its bifurcation, and duodenum. The infrarenal aorta is encircled, the inferior mesenteric artery is divided, mesentery is reflected superiorly, and the superior mesenteric artery is identified at its base and encircled. The triangular ligament of the left lobe is mobilized to allow access to the supraceliac aorta. After infrarenal and supraceliac control of the aorta is achieved, the porta hepatis is dissected.

The common bile duct is divided close to the superior margin of the head of the pancreas. The hepatic artery is dissected from its bifurcation to the celiac artery; the gastroduodenal artery is ligated and divided. The splenic artery is identified and looped with a vessel loop. The portal vein is dissected free at its midpoint between the pancreas and liver.

The nasogastric tube is advanced into the duodenum and the duodenum is flushed with a solution of amphotericin, metronidazole, and gentamicin.

The patient is heparinized (20,000 U) and the distal aorta cannulated and ligated. Inferior mesenteric vein is cannulated and the cannula is advanced up to the portal vein. The supraceliac aorta is clamped. Inferior vena cava is exposed supradiaphragmatically at its junction with the right atrium and incised. The right pleural cavity is opened. The aortic and portal cannulas are flushed with 3 and 2 L, respectively, of cold UW or other (HTK) solution. The abdomen is packed with slushed ice until the perfusion is complete.

Once flushing is complete, the ice is removed. The liver is carefully excised, taking adjacent diaphragm. The portal vein is divided, leaving an adequate stump (1 cm to 2 cm) on the pancreas side. The splenic artery is divided close to its origin and tacked with a single nonabsorbable 6-0 suture to aid future identification.

The lesser sac is opened by sharp dissection along the greater curvature of the stomach toward the spleen. The short gastric veins are divided with scissors. The spleen is mobilized carefully, dividing all it s peritoneal reflections. The spleen is elevated. The avascular plane behind the pancreas is developed, both bluntly and sharply. The peritoneal reflection along the inferior border of the pancreas is divided. After removal of the perfusion cannula, the inferior mesenteric vein is ligated on the pancreas side. The attachments along the superior border of the pancreas toward the stomach are divided by sharp dissection. The Kocher maneuver is completed. Attachments to the anterior surface of the head of the pancreas, including the right gastric and gastropiploic artery are ligated, The duodenum is divided just distal to the pylorus using a GIA stapler. Third or fourth portion of the duodenum or proximal jejunum (righ behind the ligament of Treitz) is divided in a similar manner. The mesentery and mesocolon are divided using a GIA stapler. The superior mesenteric artery is taken with a patch of aorta, without injury to the renal arteries. Pancreas is removed and packaged.

Meticulous surgical technique and attention to detail during the benchwork preparation are paramount to avoid grave technical complications posttransplant.

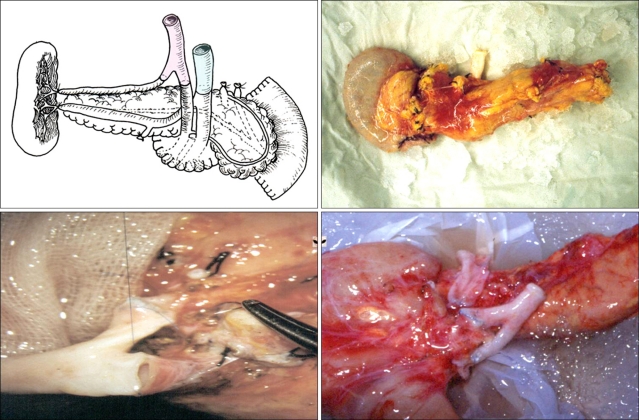

Benchwork reconstruction involves these steps: splenic hilar dissection, duodenal segment preparation, ligation of mesenteric vessels, and arterial (or venous) reconstruction (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Bench procedure for the cadaveric pancreas.

2) Living donor

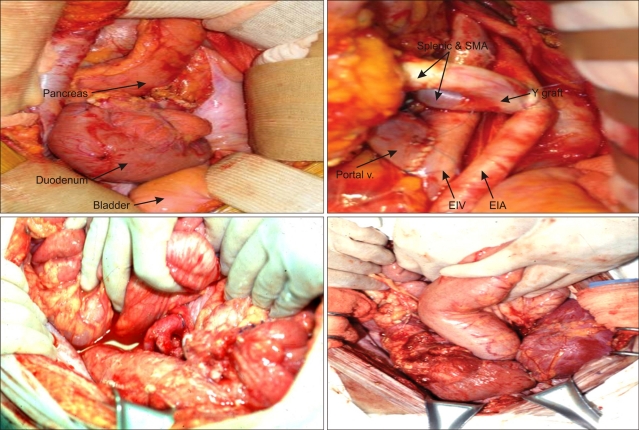

Distal pancreatectomy for a variety of pancreatic diseases is a common general surgical procedure, but removing the distal pancreas for transplantation is some-what different: gentle dissection is critical to diminish the risk of pancreatitis both in the (healthy) donor and in the recipient after revacularization. Vascular supply via the splenic artery and vein must be preserved (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Living donor organ harvest.

HA, hepatic artery; SA, splenic artery; SV, splenic vein; Panc stump, pancreatic stump.

2. Recipient procedures

Since the first pancreas transplant in 1966,12 a variety of surgical techniques for graft implantation have been reported. In fact, more so than with any other solid organ, the history of pancreas transplantation has predominantly revolved around the development and application of different surgical techniques. Most controversial issues have been the management of exocrine pancreatic secretions (bladder vs enteric drainage) and the type of venous drainage (systemic vs portal vein drainage). According to the International Pancreas Transplant Registry (IPTR), through 1995 more than 90% of all pancreas transplants worldwide were bladder drained.

Two main reasons for the widespread use of bladder drained whole-organ pancreaticoduodenal transplants are the low complication rate, with no contamination from an enterotomy, and the ability to monitor urinary amylase levels to detect graft rejection.20,48 Contrast to enteric drainage, surgical complications with bladder drainage are usually contained to the right or left lower abdominal quadrant: Leaks usually do not result in diffuse peritonitis because no abdominal spillage of enteral contents occurs. Duodenal segment or bladder leaks can frequently be managed conservatively, without surgical repair, by placement of a foley catheter and percutaneous drain. Urinary amylase measurements have been particularly helpful in solitary pancreas transplants, in which a simultaneously transplanted kidney from the same donor is not available to monitor serum creatinine levels for rejection.49

However, bladder drainage is associated with unique metabolic and urologic complications. The loss of 1 to 2 L/d of (alkaline) exocrine pancreatic and duodenal mucosal secretions in the urine results in bicarbonate deficiency and electrolyte derangements, causing chronic (hyperchloremic) metabolic acidosis and dehydration.50,51

Urologic complications are common because alkaline pancreatic enzymes are a source of irritation to the transitional epithelium of the bladder and to the lower genitourinary system. Urologic complications include the following: chemical cystitis and urethritis, recurrent hematuria, bladder stones, and recurrent graft pancreatitis from reflux. The high rate of urinary tract infections is a frequent cause of morbidity. More serious, but less common, complications include severe perineal inflammation and excoriation and, more frequently in men, ureteral disruption and strictures.

In light of the potential complications of bladder drainage and possibly their negative impact on quality of life, interest in enteric drainage resurged in the mid-1990s. Currently enteric drainage is increasingly used, thanks to improvements in surgical technique, immunosuppressive therapy, radiologic imaging and interventional procedures, and antimicrobial prophylaxis.

But, enteric drainage is a much less valuable option for solitary pancreas transplants (PTA, PAK); in these recipients, urinary amylase monitoring is crucial given the inability to monitor serum creatinine without a kidney graft from the same donor.

1) Cadaveric donor

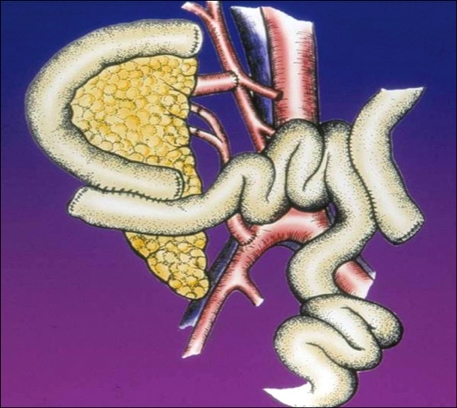

Since the original descriptions of the vascular technique, most pancreas grafts have been placed heterotopically in the pelvis, with vascular anastomoses to the recipient iliac artery and vein (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Recipient operation, cadaveric simultaneous pancreas and kidney transplantation.

SMA, superior mesenteric artery; EIV, external iliac vein; EIA, external iliac artery.

Gaber et al. used the superior mesenteric vein or one of its tributaries for venous drainage (Fig. 4).52

Fig. 4.

Portal/enteric drainage.

Portal vein drainage creates a more physiologic state of insulin metabolism. Peripheral hyperinsulinemia has been associated with atherosclerosis and portal hypoinsulinomia with lipoprotein abnormalities. Yet no convincing evidence exists today that systemic vein drainage places pancreas recipients at a disadvantage by increasing their risk of vascular disease.

The pancreas is placed intraabdominally, preferably on the right side of the pelvis, for two reasons: the iliac vessels are more superficial than on the left side and, therefore, dissection is easier on the right side and the natural position of the right iliac vessels (vein lateral to artery) does not require vascular realignment or possible ligation and division of the internal iliac artery, although on the left side it might.

When the donor portal vein is used for anastomosis, the head of the pancreas is in a cephalad position in the midabdomen. The vast majority of pancreas grafts with portal vein drainage are placed so that the donor portal vein connects to the recipient proximal superior mesenteric vein (SMV) or to the SMV's main feeding vessel. A hole in the small bowel mesentery is made so that the arterial Y-graft traverses the shortest distance to the arterial inflow (most commonly, the right common iliac artery). This distance may be as long as 6 cm.

2) Living donor

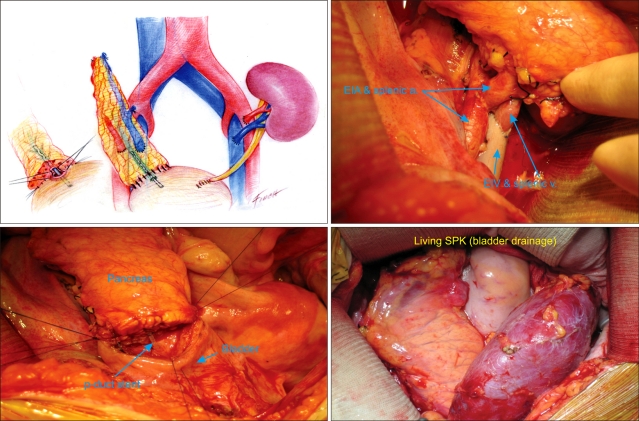

Segmental grafts are obtained from living donors. Most segmental grafts comprise the body and tail of the pancreas. The splenic artery and splenic vein are anastomosed to the recipient external iliac vessels. The dissection of the recipient iliac vessels is as extensive as with a whole organ transplant because of the importance of a tension free venous anastomosis. A tension free bladder anastomosis can be constructed. A two layer anastomosis using the invagination technique is constructed (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Recipient operation, living-donor simultaneous pancreas and kidney (SPK) transplantation.

p-duct, pancreatic duct; EIV, external iliac vein; EIA, external iliac artery.

For enteric drainage of segmental grafts, a Roux-en-Y loop is routine. Proximal small bowel is drawn caudad to the level of the cut surface of the pancreas to ensure that the mesentery of the jejunum is long enough to reach the graft. Roux-en-Y limb is anastomosed to the whole cut surface of the pancreas with the invagination technique.

POSTOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

1. General management

A meticulous preoperative evaluation, including a complete history and physical examination, is crucial to ensure optimal patient and graft outcomes.

In pancreas transplant recipients, significant emphasis must be placed on three areas: cardiovascular status, kidney function, and glucose control.

In uremic candidates, the need for hemodialysis must be determined prior to transplantation. Knowledge of dialysis status and preoperative fluid management (including electrolyte, acid base, and volume status) is vital to the proper choice of a uremic recipient for organs from a particular donor.

Successful intraoperative management depends on cooperation and team work between the surgeons, anesthesiologists, and nursing staff involved.

At the time of organ reperfusion, bleeding from the allograft may be problematic, especially from the pancreas. Adequate volume status is imperative at this time point. Aggressive use of blood products may be required, so adequate communication and preparation by the anesthesiology and nursing staffs must ensure that immediate infusion can begin if necessary.

In this phase of recovery, three major processes are evolving: The recipient is undergoing the physiological response to surgical trauma, the transplanted organs are in a varying degree of reperfusion injury/recovery (including reperfusion pancreatitis), and the recipient is now immunosuppressed.

Early graft function (pancreas or kidney) can be monitored by various means. Most centers adopt a protocol that combines laboratory as well as imaging studies to obtain a level of certainty with regard to adequate organ function. For some centers, declines in serum blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, amylase, and lipase levels along with normal blood sugar levels are all that is required to assess good graft function in SPK recipients.53,54 Some centers routinely obtain sonograms or nuclear scintography on all recipients.55-57

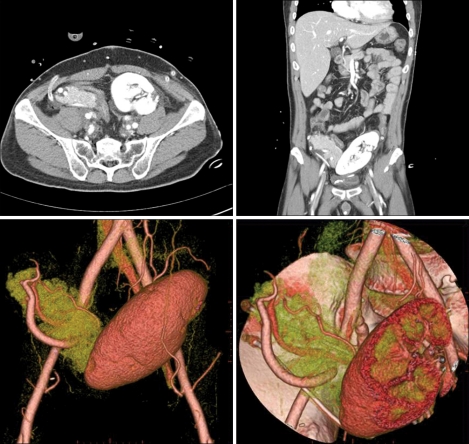

Computerized axial tomography scan can detect image of a portally drained collections, pancreatic necrosis, and possibly duodenal obstruction or leak (Fig. 6).57,58

Fig. 6.

Postoperative CT, and living-donor simultaneous pancreas and kidney transplantation.

Creatinine clearance and urine protein, C-peptied levels, and HbA1c can be periodically obtained to assess long term graft function.

For pancreas recipients with bladder-drained exocrine secretions, urinary amylase levels can be monitored.53,54 Analysis of a 12- or 24-hour urine collection in which urinary amylase levels have declined 50% or more from baseline is suggestive of rejection or pancreatitis. Confronted with this situation, further evaluation and probable biopsy are warranted either percutaneously via US or computed tomography guidance or transcystoscopically, assisted by US guidance.59,60

Prophylactic coverage against microorganisms is paramount during the perioperative period.

Postoperative care for living donor and cadaver donor pancreas recipients is similar. However, for living donor pancreas recipients, routine systemic anticoagulatory prophylaxis is recommended, given their relatively high rate of vascular thrombosis.

2. Immunosuppressants

The principles of maintenance therapy for pancreas recipients are the same as for other solid organ recipients. But, because of the high immunogenicity of (especially solitary) pancreas transplants, the amount of immunosuppression required is more than for kidney, liver, or heart transplants.

Because pancreas transplantation is regarded to be life-enhancing, rather than lifesaving, overimmunosuppression should be avoided.

The term 'induction therapy' is used to describe antilymphocyte antibody that are parenterally administered for a short course immediately posttransplant.

The rationale for using induction immunotherapeutics pertains to the agents' potent anti-T-cell immunosuppressive properties. In this context, induction therapy is used in conjunction with maintenance agents for the purpose of minimizing the risks of early rejection episodes, often with aims to accelerate renal allograft function and perhaps even inducing a tolerogenic effect to donor alloantigen.

ATGAM, Zenepax, and Simulect have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). In addition OKT3 and thymoglobulin are used for induction theraphy and effective for treatment of acute allograft rejection. Campath is an FDA-approved agent has been described for induction in kidney transplantation and used in pancreas transplantant as well.

Solid organ transplantation would not have become the treatment of choice for patients with end-stage organ failure without the concurrent development of potent immunosuppressive drugs as a maintenance treatment. In the late 1970s, the discovery of the calcineurin inhibitor, CSA by Borel et al.,61 propelled solid-organ transplantation into a new era and marked the beginning of increasingly successful extrarenal, including pancreas transplantation. By the early 1980s it was recognized that the combination of cyclosporine, azathioprine, and steroids resulted in best graft outcome. Currently triple-drug immunosuppression (now with Tacrolimus and MMF) has remained the gold standard for maintenance theraphy in pancreas transplantation. In the late 1990s, in selected pancreas recipient categories, triple immunosuppression for maintenance therapy was sometimes abandoned by steroid withdrawal or avoidance.

The principles of maintenance therapy for pancreas recipients are the same as for other solid organ recipients. But, because of the high immunogenicity of (especially solitary) pancreas transplants, the amount of immunosuppression required is more than for kidney, liver, or heart transplants.

3. Immunobiology, diagnosis, and treatment of rejection

In most cases of pancreas graft rejection, clinical symptoms are subtle or nonexistent. Only 5% to 20% of patients with pancreas graft rejection have clinical symptoms.62,63 Fever as a clinical symptom of rejection was common in the azathioprine era; but now, because calcineurin inhibitors are used for maintenance therapy, fever is uncommon. Even in the presence of clinical symptoms, the diagnosis of rejection, if a biopsy is not obtained, is usually a composite decision based on clinical and laboratory criteria.

Rejection markers can be determined in the serum or urine. For bladder drained transplants, urine amylase has been the most widely used rejection marker. For enteric drained transplants, a combination of serum exocrine (e.g., glucose disappearance rate) markers has been used.

With the successful development of safe, percutaneous biopsy techniques in the early 1990s, laboratory parameters are increasingly used as screening tests.

It appears that, based on uni- and multivariate analyses of US IPTR/UNOS and single center data, SPK transplants can be done with little regard for HLA matching. However, in the PTA and PAK categories, HLA matching has remained an important outcome factor.

Acute pancreas rejection episodes are usually treated with a 7- to 14-day course of mono- or polyclonal antibody therapy.64,65

In the immunologically more favorable SPK category, pancreas rejection episodes graded as minimal or mild can be reversed with steroid boluses, recycling of the steroid taper, or increases in calcineurin or target of rapamycin inhibitor dosages. Antibody therapy is frequently reserved for moderate or severe rejection episodes in SPK recipients.65

PANCREAS TRANSPLANT OUTCOMES

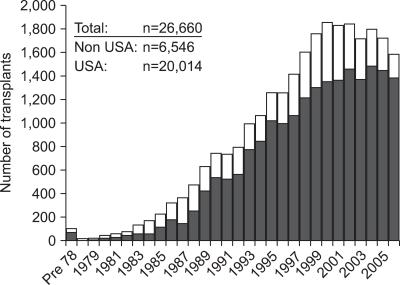

From December 16, 1966 to December 31, 2008 more than 30,000 pancreas transplants have been reported to the IPTR, including 22,000 from the United States and >8,000 from outside the US. Between 2004 and 2008 the most common pancreas transplant category was a combined pancreas/kidney transplant (73%) (Fig. 7).66

Fig. 7.

Pancreas transplants worldwide.

During this time period, the patient age at transplant increased due to an increased number of patients with type 2 diabetes reported as reason for transplantation.

Patient survival at one year is now better than 95% and reached 90% at 3 years post-transplantation. Pancreas graft function also reached 85% in SPK compared to 79% in solitary pancreas transplants.

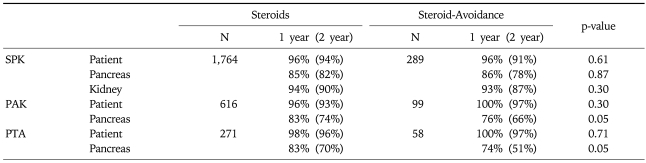

The use of young donors with short preservation time showed a significant decrease for the risk of graft failure in all 3 categories (Table 1, Fig. 8).66

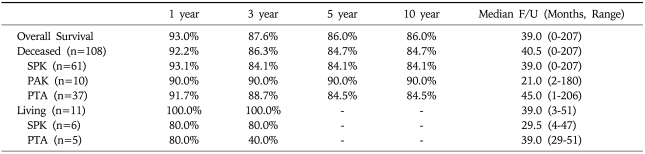

Table 1.

Patient and Graft Survival in the USA

SPK, simultaneous pancreas and kidney; PAK, pancreas after kidney; PTA, pancreas transplant alone.

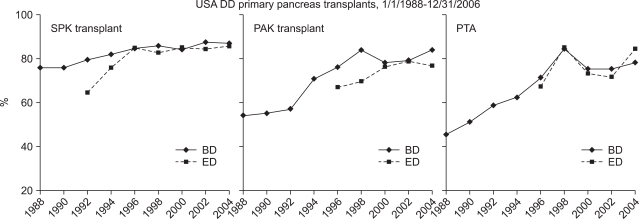

Fig. 8.

One-year pancreas graft survival in the USA.

DD, deceased donor; SPK, simultaneous pancreas and kidney; PAK, pancreas after kidney; PTA, pancreas transplant alone; BD, bladder drainage; ED, enteric drainage.

With modifications in immunosuppressive and anticoagulatory protocols, 1-year graft survival rates for living donor pancreas recipients are now >85%. Living donor transplants increase the number of organs available and decrease the number of patient deaths on the waiting list, among many advantages. A meticulous donor work-up, according to standardized evaluation criteria, remains key to a low metabolic and surgical complication rate.41

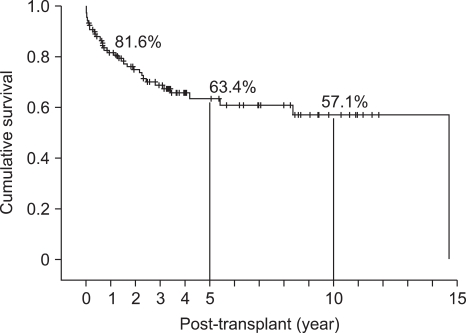

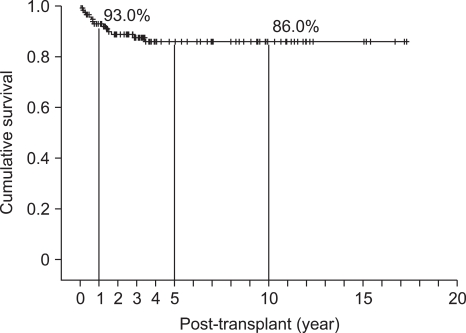

Overall 119 cases of pancreas transplantation have been performed from July 1992 to December 2009 in our institution.

Among the 119 cases, pancreas transplantation alone were 42 (43.7%), pancreas after kidney transplantation cases were 10 (8.40%) and simultaneous pancreas and kidney transplant were 67 (56.3%).

Deceased donor and living donor was 108 and 11 cases respectively. Bladder drainage was performed in 69 (60%) case and enteric drainage in 50 (42.0%) cases. Over all pancreas graft survival rates at 1, 5, 10 years were 81.6%, 63.4%, and 57.1%, respectively (Table 2, Fig. 9), and patient survival rates were 93%, 86%, and 86%, respectively. Median follow-up duration was 39 months (range, 0-207months) (Table 3, Fig. 10).

Table 2.

Pancreas Graft Survival Rate at Asan Medical Center (n=119, August 1992 to December 2009)

SPK, simultaneous pancreas and kidney; PAK, pancreas after kidney; PTA, pancreas transplant alone.

Fig. 9.

Overall graft survival rate at Asan Medical Center (n=119, August 1992 to December 2009).

Table 3.

Patient Survival Rate (n=119, August 1992 to December 2009)

SPK, simultaneous pancreas and kidney; PAK, pancreas after kidney; PTA, pancreas transplant alone.

Fig. 10.

Overall patient survival rate at Asan Medical Center (n=119, August 1992 to December 2009).

EFFECTS OF PANCREAS TRANSPLANTATION ON SECONDARY COMPLICATIONS OF DIABETES

1. Nephropathy

Bohman et al.67 in 1985 first demonstrated that the development of diabetic glomerulopathy was prevented in recipients of SPK (two patients) and PAK (six patients). Thus, Pancreas transplant performed within the first several years after KT appears to halt the progression of diabetic glomerulopathy lesions.68

It appeard that the total mesangial volume per glomerulus stopped expanding in the pancreas transplant recipients but continued to expand in the untreated patients.69 Nevertheless, the disappointing conclusion of this study was that diabetic glomerulopathy lesions were not reversed by 5 years of normoglycemia. However, GBM and TBM width, unchanged at 5 years, decreased at 10 year follow-up. Total mesangial and total mesangial matrix volumes per glomerulus were consequently unchanged at 5 years and markedly decreased at 10 years.

Thus, this study provides clear evidence that diabetic glomerular and tubular lesions in humans are reversible.70

2. Retinopathy

Most of the studies showed little impact on the progression of retinopathy. However, results pointed to the possibility that the beneficial effects on retinopathy appeared by about 3 years posttransplant, that a transplant is probably more helpful if performed at earlier stages of retinopathy, and that a transplant may have a benefit regarding macular edema.71

From an ophthalmologic standpoint, it seems almost a certainty that earlier transplants would be of benefit in preventing the development or progression of diabetic retinopathy.

3. Neuropathy

Polyneuropathy affecting somatic and autonomic nervous systems is a common secondary complication of long term diabetes mellitus.

Chronic hyperglycemia with its metabolic consequences is considered the most important factor in development of diabetic neuropathy.72,73

After a successful pancreas transplant the results of neurological evaluations tended to improve, as indicated by the increase in the mean values of the indices of neuropathy. The motor and sensory nerve conduction indices already showed significant improvement from values at entry in the study after 1 year, and additional improvements were seen at all the intervals tested. On the other hand, the mean autonomic function indices only showed noticeable improvement after 5 year of the transplantation.41

During 10 years of follow-up clearly demonstrated that peripheral nerve function improved in patients who achieved a normoglycemic state after a successful transplant.74 Improvement was maintained throughout the 10-year follow-up after transplant and was more obvious for somatic than for autonomic nerve functions.

4. Quality of life

In addition to the potential favorable effects of pancreas transplant on the secondary complications of diabetes, several studies have shown that the overall quality of life improves after a successful tranplant.75-78

Improvement in quality of life is, at least in part, attributable to improvement of autonomic and somatic nerve function, which allows for better development of general life activities and adaptation to social stress events.78

CONCLUSION

In pancreas transplantation, patient and graft survival rates have been improved over time due to refined surgical technique and immunosuppressant evolution. In near future, pancreas transplantation will be expected to be a primary option for curative treatment of diabetes, namely, pancreas transplant alone in early stage of diabetic complication as well as simultaneous kidney and pancreas transplantation in advanced diabetic complication.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes fact sheet: national estimates and general information on diabetes in the United States. Revised ed. Atlanta: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Korean Diabetes Association, Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service. Report of task force team for basic statistical study of Korean diabetes mellitus: diabetes in Korea 2007. Seoul: Goldfishery; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes surveillance. Atlanta: Department of Health and Human Services; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris MI National Diabtes Data Group, editor. Diabetes in America. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: NIH, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 1995. Summary; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ehtisham S, Barrett TG, Shaw NJ. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in UK children--an emerging problem. Diabet Med. 2000;17:867–871. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fagot-Campagna A, Pettitt DJ, Engelgau MM, et al. Type 2 diabetes among North American children and adolescents: an epidemiologic review and a public health perspective. J Pediatr. 2000;136:664–672. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.105141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977–986. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klen R, Klein BE. Vision disorders in diabetes. In: Harris MI, editor. Diabetes in America. Washington, DC: NIH; 1995. pp. 293–337. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palumbo PJ, Melton LJ. Peripheral vascular disease and diabetes. In: Harris MI, Hamman RF, editors. Diabetes in America. Washington, DC: NIH; 1985. pp. XV1–XV21. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reiber GE, Boyko EJ, Smith DG. Lower extremity foot ulcers and amputations in diabetes. In: Harris MI, editor. Diabetes in America. Washington, DC: NIH; 1995. pp. 409–427. [Google Scholar]

- 11.White SA, Shaw JA, Sutherland DE. Pancreas transplantation. Lancet. 2009;373:1808–1817. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60609-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelly WD, Lillehei RC, Merkel FK, Idezuki Y, Goetz FC. Allotransplantation of the pancreas and duodenum along with the kidney in diabetic nephropathy. Surgery. 1967;61:827–837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lillehei RC, Idezuki Y, Feemster JA, et al. Transplantation of stomach, intestine, and pancreas: experimental and clinical observations. Surgery. 1967;62:721–741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gliedman ML, Gold M, Whittaker J, et al. Clinical segmental pancreatic transplantation with ureter-pancreatic duct anastomosis for exocrine drainage. Surgery. 1973;74:171–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merkel FK, Ryan WG, Armbruster K, Seim S, Ing TS. Pancreatic transplantation for diabetes mellitus. IMJ Ill Med J. 1973;144:477–479. passim. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dubernard JM, Traeger J, Neyra P, Touraine JL, Tranchant D, Blanc-Brunat N. A new method of preparation of segmental pancreatic grafts for transplantation: trials in dogs and in man. Surgery. 1978;84:633–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sollinger HW, Kamps D, Cook K, et al. Segmental pancreatic allotransplantation with high-dose cyclosporine and low-dose prednisone. Transplant Proc. 1983;15:2997–3000. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nghiem DD, Corry RJ. Technique of simultaneous renal pancreatoduodenal transplantation with urinary drainage of pancreatic secretion. Am J Surg. 1987;153:405–406. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(87)90588-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Starzl TE, Iwatsuki S, Shaw BW, Jr, et al. Pancreaticoduodenal transplantation in humans. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1984;159:265–272. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prieto M, Sutherland DE, Goetz FC, Rosenberg ME, Najarian JS. Pancreas transplant results according to the technique of duct management: bladder versus enteric drainage. Surgery. 1987;102:680–691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nankivell BJ, Allen RD, Bell B, et al. Factors affecting measurement of urinary amylase after bladder-drained pancreas transplantation. Clin Transplant. 1991;5:392–397. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benedetti E, Najarian JS, Gruessner AC, et al. Correlation between cystoscopic biopsy results and hypoamylasuria in bladder-drained pancreas transplants. Surgery. 1995;118:864–872. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(05)80277-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gruessner AC, Sutherland DE. Pancreas transplant outcomes from United States (US) cases reported to the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) and non-US cases reported to the International Pancreas Transplant Registry (IPTR) as of October 2000. Los Angeles: UCLA Immunogenetics Center; 2001. pp. 45–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenlof LK, Earnhardt RC, Pruett TL, et al. Pancreas transplantation. An initial experience with systemic and portal drainage of pancreatic allografts. Ann Surg. 1992;215:586–595. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199206000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shokouh-Amiri MH, Gaber AO, Gaber LW, et al. Pancreas transplantation with portal venous drainage and enteric exocrine diversion: a new technique. Transplant Proc. 1992;24:776–777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaber AO, Shokouh-Amiri MH, Hathaway DK, et al. Results of pancreas transplantation with portal venous and enteric drainage. Ann Surg. 1995;221:613–622. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199506000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sutherland DE, Goetz FC, Najarian JS. Living-related donor segmental pancreatectomy for transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1980;12:19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gruessner RW, Sutherland DE. Simultaneous kidney and segmental pancreas transplants from living related donors - the first two successful cases. Transplantation. 1996;61:1265–1268. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199604270-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gruessner RW, Kandaswamy R, Denny R. Laparoscopic simultaneous nephrectomy and distal pancreatectomy from a live donor. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;193:333–337. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)01010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tojimbara T, Teraoka S, Babazono T, et al. Long-term outcome after combined pancreas and kidney transplantation from non-heart-beating cadaver donors. Transplant Proc. 1998;30:3793–3794. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)01239-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sutherland DE, Gruessner R, Gillingham K, et al. A single institution's experience with solitary pancreas transplantation: a multivariate analysis of factors leading to improved outcome. Clin Transpl. 1991:141–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cicalese L, Giacomoni A, Rastellini C, Benedetti E. Pancreatic transplantation: a review. Int Surg. 1999;84:305–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gruessner AC, Barrou B, Jones J, et al. Donor impact on outcome of bladder-drained pancreas transplants. Transplant Proc. 1993;25:3114–3115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gruessner RW, Sutherland DE, Troppmann C, et al. The surgical risk of pancreas transplantation in the cyclosporine era: an overview. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:128–144. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)00895-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gores PF, Gillingham KJ, Dunn DL, Moudry-Munns KC, Najarian JS, Sutherland DE. Donor hyperglycemia as a minor risk factor and immunologic variables as major risk factors for pancreas allograft loss in a multivariate analysis of a single institution's experience. Ann Surg. 1992;215:217–230. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199203000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gores PF, Viste A, Hesse UJ, Moudry-Munns KC, Dunn DL, Sutherland DE. The influence of donor hyperglycemia and other factors on long-term pancreatic allograft survival. Transplant Proc. 1990;22:437–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hesse UJ, Sutherland DE. Influence of serum amylase and plasma glucose levels in pancreas cadaver donors on graft function in recipients. Diabetes. 1989;38(Suppl 1):1–3. doi: 10.2337/diab.38.1.s1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nghiem DD, Cottington EM, Corry RJ. Pancreas donor criteria. Transplant Proc. 1988;20:1007–1009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wright FH, Wright C, Ames SA, Smith JL, Corry RJ. Pancreatic allograft thrombosis: donor and retrieval factors and early postperfusion graft function. Transplant Proc. 1990;22:439–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.D'Alessandro AM, Stratta RJ, Sollinger HW, Kalayoglu M, Pirsch JD, Belzer FO. Use of UW solution in pancreas transplantation. Diabetes. 1989;38(Suppl 1):7–9. doi: 10.2337/diab.38.1.s7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sibley S, Seaquist ER. Diabetes mellitus: classification and epidemiology. In: Gruessner R, Sutherland DE, editors. Transplantation of the pancreas. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2004. pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kendall DM, Sutherland DE, Najarian JS, Goetz FC, Robertson RP. Effects of hemipancreatectomy on insulin secretion and glucose tolerance in healthy humans. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:898–903. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199003293221305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gruessner RW, Kendall DM, Drangstveit MB, Gruessner AC, Sutherland DE. Simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation from live donors. Ann Surg. 1997;226:471–480. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199710000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sasaki TM, Gray RS, Ratner RE, et al. Successful long-term kidney-pancreas transplants in diabetic patients with high C-peptide levels. Transplantation. 1998;65:1510–1512. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199806150-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sutherland DE. Is immunosuppression justified for nonuremic diabetic patients to keep them insulin independent? (The argument for) Transplant Proc. 2002;34:1927–1928. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(02)03126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cryer PE. Hypoglycemia-associated autonomic failure in diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;281:E1115–E1121. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.281.6.E1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gruessner RW, Sutherland DE, Drangstveit MB, Bland BJ, Gruessner AC. Pancreas transplants from living donors: short- and long-term outcome. Transplant Proc. 2001;33:819–820. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(00)02329-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Prieto M, Sutherland DE, Fernandez-Cruz L, Heil J, Najarian JS. Experimental and clinical experience with urine amylase monitoring for early diagnosis of rejection in pancreas transplantation. Transplantation. 1987;43:73–79. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198701000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sollinger HW, Pirsch JD, Dalessandro AM, Kalayoglu M, Belzer FO. Advantages of bladder drainage in pancreas transplantation: a personal view. Clin Transplant. 1990;4:32–36. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sindhi R, Stratta RJ, Lowell JA, et al. Experience with enteric conversion after pancreatic transplantation with bladder drainage. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;184:281–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.See WA, Smith JL. Activated proteolytic enzymes in the urine of whole organ pancreas transplant patients with duodenocystostomy. Transplant Proc. 1991;23:1615–1616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muhlbacher F, Gnant MF, Auinger M, et al. Pancreatic venous drainage to the portal vein: a new method in human pancreas transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1990;22:636–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Prieto M, Sutherland DE, Fernandez-Cruz L, Heil J, Najarian JS. Urinary amylase monitoring for early diagnosis of pancreas allograft rejection in dogs. J Surg Res. 1986;40:597–604. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(86)90103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Prieto M, Sutherland DE, Fernandez-Cruz L, Heil J, Najarian JS. Experimental and clinical experience with urine amylase monitoring for early diagnosis of rejection in pancreas transplantation. Transplantation. 1987;43:73–79. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198701000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Patel B, Markivee CR, Mahanta B, Vas W, George E, Garvin P. Pancreatic transplantation: scintigraphy, US, and CT. Radiology. 1988;167:685–687. doi: 10.1148/radiology.167.3.3283839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nghiem DD, Ludrosky L, Young JC. Evaluation of pancreatic circulation by duplex color Doppler flow sonography. Transplant Proc. 1994;26:466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dachman AH, Newmark GM, Thistlethwaite JR, Jr, Oto A, Bruce DS, Newell KA. Imaging of pancreatic transplantation using portal venous and enteric exocrine drainage. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:157–163. doi: 10.2214/ajr.171.1.9648780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moulton JS, Munda R, Weiss MA, Lubbers DJ. Pancreatic transplants: CT with clinical and pathologic correlation. Radiology. 1989;172:21–26. doi: 10.1148/radiology.172.1.2662252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jones JW, Nakhleh RE, Casanova D, Sutherland DE, Gruessner RW. Cystoscopic transduodenal pancreas transplant biopsy: a new needle. Transplant Proc. 1994;26:527–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Benedetti E, Najarian JS, Gruessner AC, et al. Correlation between cystoscopic biopsy results and hypoamylasuria in bladder-drained pancreas transplants. Surgery. 1995;118:864–872. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(05)80277-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Borel JF, Feurer C, Gubler HU, Stahelin H. Biological effects of cyclosporin A: a new antilymphocytic agent. Agents Actions. 1976;6:468–475. doi: 10.1007/BF01973261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stratta RJ, Sollinger HW, D'Alessandro AM, Pirsch JD, Kalayoglu M, Belzer FO. OKT3 rescue therapy in pancreas-allograft rejection. Diabetes. 1989;38(Suppl 1):74–78. doi: 10.2337/diab.38.1.s74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sutherland DE, Dunn DL, Goetz FC, et al. A 10-year experience with 290 pancreas transplants at a single institution. Ann Surg. 1989;210:274–285. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198909000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sutherland DE, Gruessner RW, Dunn DL, et al. Lessons learned from more than 1,000 pancreas transplants at a single institution. Ann Surg. 2001;233:463–501. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200104000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sollinger HW, Odorico JS, Knechtle SJ, D'Alessandro AM, Kalayoglu M, Pirsch JD. Experience with 500 simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplants. Ann Surg. 1998;228:284–296. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199809000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gruessner AC, Sutherland DE. Pancreas transplant outcomes for United States (US) cases as reported to the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) and the International Pancreas Transplant Registry (IPTR) Clin Transpl. 2008:45–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bohman SO, Tyden G, Wilczek H, et al. Prevention of kidney graft diabetic nephropathy by pancreas transplantation in man. Diabetes. 1985;34:306–308. doi: 10.2337/diab.34.3.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bilous RW, Mauer SM, Sutherland DE, Najarian JS, Goetz FC, Steffes MW. The effects of pancreas transplantation on the glomerular structure of renal allografts in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:80–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198907133210204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fioretto P, Mauer SM, Bilous RW, Goetz FC, Sutherland DE, Steffes MW. Effects of pancreas transplantation on glomerular structure in insulin-dependent diabetic patients with their own kidneys. Lancet. 1993;342:1193–1196. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92183-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fioretto P, Steffes MW, Sutherland DE, Goetz FC, Mauer M. Reversal of lesions of diabetic nephropathy after pancreas transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:69–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807093390202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ramsay RC, Goetz FC, Sutherland DE, et al. Progression of diabetic retinopathy after pancreas transplantation for insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:208–214. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198801283180403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brown MJ, Asbury AK. Diabetic neuropathy. Ann Neurol. 1984;15:2–12. doi: 10.1002/ana.410150103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Amthor KF, Dahl-Jorgensen K, Berg TJ, et al. The effect of 8 years of strict glycaemic control on peripheral nerve function in IDDM patients: the Oslo Study. Diabetologia. 1994;37:579–584. doi: 10.1007/BF00403376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Navarro X, Sutherland DE, Kennedy WR. Long-term effects of pancreatic transplantation on diabetic neuropathy. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:727–736. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gross CR, Zehrer CL. Health-related quality of life outcomes of pancreas transplant recipients. Clin Transplant. 1992;6:165–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zehrer CL, Gross CR. Comparison of quality of life between pancreas/kidney and kidney transplant recipients: 1-year follow-up. Transplant Proc. 1994;26:508–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nakache R, Tyden G, Groth CG. Long-term quality of life in diabetic patients after combined pancreas-kidney transplantation or kidney transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1994;26:510–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hathaway DK, Abell T, Cardoso S, Hartwig MS, el Gebely S, Gaber AO. Improvement in autonomic and gastric function following pancreas-kidney versus kidney-alone transplantation and the correlation with quality of life. Transplantation. 1994;57:816–822. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199403270-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]