Abstract

Background/Aims

To evaluate the association between Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection and gastric cancer (GC) according to tumor subtype in Korea.

Methods

H. pylori status was determined serologically using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. In total, 2,819 patients with GC and 562 healthy controls were studied. A logistic regression method was used after adjusting for possible confounders.

Results

The prevalence of H. pylori infection was significantly higher in the GC patients (84.7%) than in the controls (66.7%) (odds ratio [OR], 3.13; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.46-3.97). The adjusted OR was significantly higher in H. pylori-infected patients aged <60 years (OR, 4.69; 95% CI, 3.44-6.38) than in those aged ≥60 years (OR, 1.48; 95% CI, 0.88-2.46; p<0.001). Subgroup analyses revealed no differences in seroprevalence between early gastric cancer (84.8%; OR, 3.01; 95% CI, 2.27-4.01) and advanced gastric cancer (84.6%; OR, 2.94; 95% CI, 2.24-3.85), cardia cancer (83.8%; OR, 2.98; 95% CI, 2.16-4.02) and noncardia cancer (84.8%; OR, 3.17; 95% CI, 2.48-4.04), and differentiated carcinoma (82.7%; OR, 2.99; 95% CI, 2.21-4.04) and undifferentiated carcinoma (86.8%; OR, 3.05; 95% CI, 2.32-4.00).

Conclusions

The seroprevalence of H. pylori was higher in GC patients than in healthy controls, especially in younger patients. H. pylori infection is associated with GC, regardless of the tumor location, stage, or differentiation.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Gastric cancer, Prevalence, Odds ratio, Subgroup analysis

INTRODUCTION

Although several prospective studies have supported that Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is a risk factor for the development of gastric cancer,1,2 not all epidemiological studies have shown that positive relationship between H. pylori infection and gastric cancer.3,4 These discrepancies may be due to marked differences in gastric cancer incidence and H. pylori prevalence in different geographic regions. Some population-based studies have shown that high levels of H. pylori infection were not accompanied by high gastric cancer mortality, the so-called African5 and Asian enigmas.6 Another possible explanations for the discrepancies in the study are confounding factors affecting both H. pylori infection and gastric cancer development, and differing proportions of gastric cancer subtypes related to tumor location, histological type, and tumor stage.

Gastric cancer remains the second most common cause of cancer deaths worldwide, as well as being the most common malignancy in South Korea.7,8 Recently, the seroprevalence of H. pylori in South Korea was reported as 59.6-66.9%,9,10 showing that Korea is still a H. pylori-prevalent area. Epidemiological studies on the association between H. pylori and gastric cancer in South Korea,4,11-13 however, have shown inconsistent results, but each of these studies included no more than 200 patients with gastric cancer.

Substantial studies on gastric cancer subtypes have also yielded conflicting results. There are discrepancies in gastric cardia cancer between Western and most Asian population studies.14-16 Studies on the association between H. pylori infection and gastric cancer according to histological type have yielded inconsistent results.17-19 Confounding factors such as age could affect both H. pylori infection and gastric cancer development.20 Furthermore, the association between H. pylori infection and gastric cancer may be modified by the level of exposure to other factors such as smoking or alcohol.21

The aim of the current large-scale study was to evaluate the association between H. pylori infection and gastric cancer in a region of high prevalence of both H. pylori infection and gastric cancer after adjusting for possible confounding factors. We also evaluated whether the association is confined to specific subtypes of gastric cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Subjects

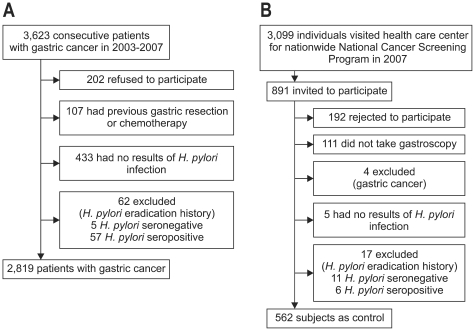

Fig. 1 shows the flow of participants. Between June 2003 and April 2007, 3,623 consecutive patients were diagnosed as having gastric cancer at the National Cancer Center Hospital. They underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and biopsy. All biopsies were evaluated by a single experienced histopathologist (M-C Kook), and each case of gastric cancer was confirmed as adenocarcinoma. We excluded patients who did not provide written informed consent (n=202); those with a previous history of gastric cancer treatment, such as gastric resection, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy (n=107); those who did not have results of H. pylori infection (n=433); and patients with a history of H. pylori eradication (n=62). Thus, a total of 2,819 patients was studied (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Flow of the participants, gastric cancer patients (A) and control subjects (B), in the study.

Gastric cancer cases were classified as cardia cancer if their centers were within 2 cm distal to the gastroesophageal junction and as noncardia cancer otherwise.22 Tumor overlapped two or more sites that included the cardia, or were present at more than two separate sites simultaneously, were excluded from site-specific analysis. Gastric cancer was also divided into early and advanced cancer, after pathological examination following endoscopic or surgical resection. Early gastric cancer (EGC) was defined as a tumor that was confined to the mucosa or submucosa regardless of lymph node involvement,23 and advanced gastric cancer (AGC) was defined as a tumor that invaded beyond the submucosa. In patients who did not undergo resection due to metastatic gastric cancer, tumor stage was determined by endoscopic and computer tomographic findings. Gastric cancers were classified histopathologically according to Lauren-s system (intestinal, diffuse, and mixed type)24 and on the Japanese classification system (differentiated and undifferentiated carcinoma)25 by a single pathologist. If a tumor was present at more than two separate sites synchronously, we included the dominant one in tumor depth.

Controls were enrolled from healthy adults who visited the health-care center at the National Cancer Center Hospital for the nationwide National Cancer Screening Program in Korea. From July 2007 through December 2007, 891 individuals were invited to participate as controls. Of those, 192 subjects declined to participate in the study and 111 individuals did not undergo EGD examination. Four individuals were excluded since they were diagnosed as having gastric adenocarcinoma, 5 were excluded due to unavailability of results of H. pylori infection, and 17 were excluded due to a history of H. pylori eradication. Thus, remaining 562 controls were studied (Fig. 1B).

Each subject was asked to answer a questionnaire under the supervision of a well-trained interviewer. The questionnaire included questions regarding demographic data (age, sex, and familial history of gastric cancer), environmental information (smoking, alcohol consumption, type of drinking water during childhood, number of sibling, type of residence), and socioeconomic data (familial income, education level). Smoking status was classified as ever- or nonsmokers. First-degree family history of gastric cancer was regarded positive if at least one of their parents or siblings had been diagnosed as having gastric cancer.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Cancer Center, Korea (NCCNCS-09-264), and written informed consent was obtained from each of the patients before being enrolled into the study.

2. Serological examination

A blood sample was obtained from each participant. Anti-H. pylori IgG was measured using H. pylori-EIA-Well kit (Radim, Rome, Italy) according to the manufacturer-s protocol, with a sensitivity of 88.0% and a specificity of 93.8% in the Korean population.26 Patients were categorized as seropositive and seronegative for H. pylori according to a selective cutoff value of IgG (15 UR/mL).

3. Statistical analysis

All p-values were two-sided, and p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. We used the Student's t-test for continuous variables, and the χ2 test and Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. Logistic regression models were used to estimate unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Data were adjusted for demographic characteristics and potential confounders. We also estimated the adjusted ORs by stage (EGC vs AGC), anatomical location (cardia versus noncardia), Japanese classification of cancer differentiation (differentiated versus undifferentiated), Lauren's classification (intestinal vs diffuse vs mixed), and age at diagnosis (<0 years vs ≥60 years). Cutoff point for age was chosen so that there would be an appropriate ratio of cancer patients and controls on each side of the cutoff point. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata 9.2 (STATA Co., College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

1. Demographic characteristics and potential confounders

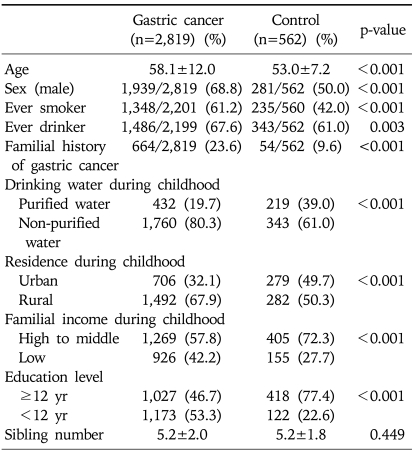

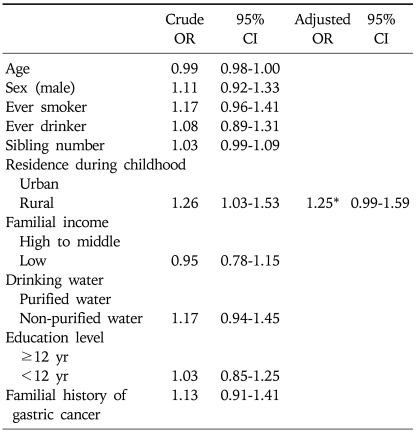

Table 1 shows the distribution of the case and control subjects by demographic characteristics. Compared with control subjects, case subjects were significantly older. The proportion of males, smoking history, alcohol consumption, and familial history of gastric cancer were significantly higher in case than in control subjects. Case subjects were more likely to have been exposed to non-purified water and a rural environment in their childhoods than were control subjects. Familial income and education level were lower in case than in control subjects. Using a model of best fit by multivariate logistic regression analysis, however, none of these variables was significantly related to the risk of H. pylori infection (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics and Potential Confounders in Gastric Cancer Patients and Control Subjects

Student's t-test for continuous variables, and χ2 test for categorical variables.

Differences in denominators were caused by non-responders.

Table 2.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis of Risk for H. pylori Infection

OR, odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

*Adjusted for sex, smoking, drinking water, education level, and socioeconomic status during childhood.

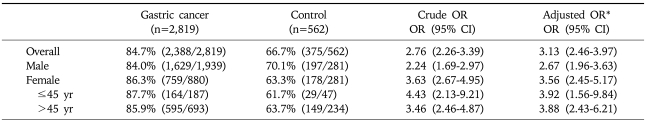

2. Overall analysis

H. pylori seropositivity was 84.7% for patients with gastric cancer and 66.7% for controls, yielding a summary crude OR of 2.76 (95% CI, 2.26-3.39) and an adjusted OR of 3.13 (95% CI, 2.46-3.97). Female patients tended to have a higher OR for H. pylori seroprevalence compared to male patients, however it was not statistically significance (p=0.126) (Table 3). The seroprevalence of the control group was slightly higher than that (59.6%) of previous study performed in 2005, in which the subjects were asymptomatic Korean adults attending health check-ups.9

Table 3.

Prevalence of H. pylori Infection in Gastric Cancer Patients and Control Subjects

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

*Adjusted for age, sex, familial history of gastric cancer, smoking, alcohol consumption, residence during childhood, drinking water, education level, and socioeconomic status during childhood.

3. Subgroup analysis

1) EGC vs AGC

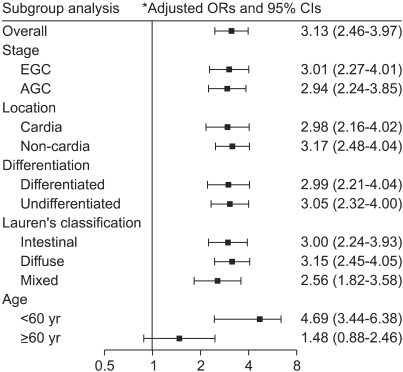

H. pylori seropositivity was found in 84.8% (1,055 of 1,244) of patients with EGC and 66.7% (375 of 562) of control individuals, yielding an adjusted OR estimate of 3.01 (95% CI, 2.27-4.01). H. pylori seropositivity was detected in 84.6% (1,333 of 1,575) of patients with AGC, giving an adjusted OR compared with controls of 2.94 (95% CI, 2.24-3.85) (Fig. 2). There was no significant difference in H. pylori seropositivity between these two groups of patients (χ2 test; p=0.900).

Fig. 2.

Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between H. pylori infection and gastric cancer, overall and by subgroup. *Adjusted for age, sex, familial history of gastric cancer, smoking, alcohol consumption, residence during childhood, source of drinking water, education level, and socioeconomic status during childhood.

2) Cardia vs noncardia cancer

We found that 83.8% (181 of 216) of patients with cardia gastric cancer was H. pylori seropositive, giving an adjusted OR compared with controls of 2.98 (95% CI, 2.16-4.02). In comparison, 84.8% (2,207 of 2,603) of patients with noncardia cancer was H. pylori seropositive, yielding an adjusted OR of 3.17 (95% CI, 2.48-4.04) (Fig. 2). There was no significant difference in H. pylori seropositivity between these two groups of patients (χ2 test; p=0.698).

3) Differentiated versus undifferentiated gastric cancer

We found that 82.7% (1,208 of 1,460) of patients with differentiated type gastric cancer was H. pylori seropositive, giving an adjusted OR compared with controls of 2.99 (95% CI, 2.21-4.04). In comparison, 86.8% (1,162 of 1,339) of patients with undifferentiated type gastric cancer was H. pylori seropositive, yielding an adjusted OR compared with controls of 3.05 (95% CI, 2.32-4.00) (Fig. 2). The prevalence of H. pylori seropositivity was significantly higher in gastric cancer patients with undifferentiated type than with differentiated type (χ2 test; p=0.003; OR, 1.36 [95% CI, 1.11-1.67]). However, the significance disappeared after adjustment for age and sex (OR, 1.14 [95% CI, 0.91-1.42]).

4) Histological types according to Lauren's classification

Of the 1,349 patients with intestinal type gastric cancer, 1,125 (83.4%) were seropositive for H. pylori, yielding an adjusted OR compared with controls of 3.00 (95% CI, 2.24-3.93). In comparison, 87.1% (848 of 974) of patients with diffuse type gastric cancer, and 84.3% (86 of 102) of patients with mixed type gastric cancer were seropositive, yielding adjusted ORs compared with controls of 3.15 (95% CI, 2.45-4.05) and 2.56 (95% CI, 1.82-3.58), respectively (Fig. 2). The prevalence of H. pylori seropositivity in patients with diffuse type gastric cancer was significantly higher than in those with intestinal type gastric cancer (χ2 test; p=0.04; OR, 1.35 [95% CI, 1.07-1.70]), but this difference was not observed after adjustment for age and sex (OR, 1.02 [95% CI, 0.79-1.32]).

5) Age at diagnosis

The H. pylori seropositivity rate in control subjects <60 years (64.4%, 288 of 447) was lower than that in control subjects ≥60 years (75.7%, 87 of 115). In contrast, the seroposivity rate was higher in case subjects <60 years (88.5%, 1,231 of 1,391) than that in case subjects ≥60 years (81.0%, 1,157 of 1,428). The adjusted OR of gastric cancer patients aged <60 years for the prevalence of H. pylori infection (4.69 [95% CI, 3.44-6.38]) was higher than that of those aged ≥60 years (1.48 [95% CI, 0.88-2.46]) (Fig. 2). This difference was significant, giving an OR of 1.80 (95% CI, 1.46-2.23).

DISCUSSION

This large-scale study was designed to investigate the association between H. pylori infection and gastric cancer in Korean patients. The large number of gastric cancer patients enrolled allowed subgroup analyses.

We found that the prevalence of H. pylori infection in gastric cancer patients was higher than in healthy control subjects, giving an overall adjusted OR of 3.24 (95% CI, 2.56-4.10). This result quantitatively supports the conclusion by the IARC that infection with H. pylori is a risk factor for gastric cancer in humans,27 although this may have underestimated the real attributable risk of H. pylori infection for gastric cancer caused by short time interval between serum collection and cancer diagnosis.15,28 A combined analysis of prospective studies showed a summary OR of 3.0 for gastric noncardia cancer.28 Because H. pylori does not colonize premalignant lesions of the stomach,29 serum antibodies to H. pylori may decline by the time gastric cancer develops. Therefore, the best estimate of the OR of H. pylori for gastric noncardia cancer was suggested to be 5.9, after more than 10 years of follow-up.28

We found that the strength of the association between H. pylori seropositivity and the risk of gastric cancer did not vary significantly by cancer stage. In previous analyses, however, the prevalence of H. pylori infection was significantly higher in patients with EGC than in those with AGC.19,20,30 Most untreated EGCs are reported to progress to AGC within 4-5 years.31 The lower frequency of H. pylori IgG antibodies in AGC may result from a decrease in antibody titer, due to the development of advanced H. pylori-associated atrophic gastritis concomitant with age. Intragastric environment of AGC patients is more inhospitable to H. pylori, resulting in disappearance of infection.29,32 Therefore, the histological characteristics of advanced cancer in the elderly typically show advanced atrophic changes caused by the presence of long-standing H. pylori infection yet the absence of infection. The mean age of patients with AGC was greater than that of patients with EGC in most studies included in meta-analysis.30 The difference in OR between EGC and AGC likely reflects the decrease in prevalence of H. pylori infection by increasing age.19 Thus, our finding of no difference in H. pylori seropositivity between EGC and AGC patients may originate from the similar mean ages (58.6 and 57.3 years, respectively). This suggests that H. pylori may be associated with gastric carcinogenesis, but not cancer progression.

We found that H. pylori seropositivity was associated with both gastric cardia and noncardia cancer. Although a strong positive association has been reported between H. pylori seropositivity in gastric noncardia adenocarcinoma,15,20,28 studies have found a null20,28 or inversely associated relationship15 between anti-H. pylori seropositivity and gastric cardia cancer. This association shows substantial geographic variation. Most studies in Asian populations have found a positive association between H. pylori seropositivity and cardia cancer,16,19 whereas most studies in Western populations have found nonassociation or an inverse association.15,33,34 This discrepancy may have been due, at least in part, to the classification in Western studies of some patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma as having gastric cardia cancer, particularly because it is not always possible to distinguish between adenocarcinomas that arise in the gastric cardia and in the lower esophagus.15 However, in some parts of Asia where Barrett's esophagus and adenocarcinomas of the lower esophagus are rare,16 tumors classified as cardia gastric cancers do not include any esophageal adenocarcinomas, making all cardia cancers of gastric origin, rather than a mixture of gastric and esophageal malignancies. Another hypothesis is that H. pylori colonization induces gastric atrophy, which results in reduced gastric acidity, less acid reflux into the esophagus, and a reduced risk of Barrett's esophagus and junctional cancers.35,36 Since the 1970s, there has been a substantial reduction in H. pylori prevalence, but a substantial increase in the incidence of gastric cardia adenocarcinoma in Western populations.37,38 Cardia cancer was recently reported to be positively associated with both gastric atrophy (OR, 3.92; 95% CI, 1.77-8.67) and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms (OR, 10.08; 95% CI, 2.29-44.36), with the latter apparent only in the nonatrophic subgroup. These findings indicated that there are two etiologies of cardia cancer, one arising from severe atrophic gastritis and being of intestinal or diffuse subtype, similar to noncardia cancer, and the other related to GERD and the intestinal subtype, similar to esophageal adenocarcinoma.22 Thus, atrophic gastritis related to H. pylori infection would contribute to a positive association between H. pylori infection and cardia cancer in Asian countries, whereas GERD may contribute to a negative or null association in Western countries, where Barrett's esophagus is more common than Asian countries.

H. pylori has been reported to be a causal factor in the atrophic gastritis-intestinal metaplasia-intestinal type of gastric cancer sequence, hypothesized by Correa.39 The prevalence of H. pylori infection seems to be greater in intestinal type than in diffuse type gastric cancers.18,40 However, most comprehensive studies have shown that there is no difference in H. pylori seroprevalence between these two types,15,20,28 a finding consistent with the present study.

Gastric cancer can be classified as differentiated or undifferentiated carcinoma according to Japanese classification.25 We found that both histological types have a similar association with H. pylori infection. Although previous studies showed that H. pylori infection may be associated with the differentiated, but not the undifferentiated type of gastric cancer,41,42 the number patients with undifferentiated type cancer was small (n=17 and 15, respectively, in two previous studies). Moreover, a recent study in Japan indicated that the ORs were similar (5.8 for differentiated and 5.1 for undifferentiated type).43

Younger H. pylori-infected patients have been found to be at higher relative risk for gastric cancer than older patients,20 a finding consistent with the present study. This can be explained by the lower infection rate in the younger controls, whereas the age-related prevalence of H. pylori infection increased significantly with the cohort effect in controls but not in cases.20 In addition, H. pylori prevalence was higher in younger than in older gastric cancer patients, which may be due to the spontaneous disappearance of infection caused by increased mucosal atrophy and intestinal metaplasia with advanced age, inhospitable place for H. pylori colonization.29,32 Generally, patients with gastric cancer have more severe mucosal atrophy and intestinal metaplasia in the stomach than normal subjects.44 Another hypothesis is that humoral immune response tends to decrease with age,45 resulting in the underdetection of serum antibodies against H. pylori.

Meanwhile, earlier reports showed that the prognosis of patients with early onset of gastric cancer was poor, with a short survival potential, especially in patients who presented with advanced gastric carcinoma.46,47 In a few reports, however, the prognosis of patients with early-onset gastric cacner who underwent gastrectomy was better than that of older patients.48,49 Recent reports have showed no difference in surgical outcomes between older and younger patients with gastric cancer.50-53 Therefore, age does not appear to be an independent risk factor for gastric cancer. Regarding to sex, homornal difference might be an important factor for prognosis in patients with gastric cancer. Several studies54 found that female sex hormones and their analogues appear to be associated with gastric carcinogenesis and progression, and that pregnancy and delivery may accelerate growth of stomach cancer cells.55-57 Further studies are needed to evaluate different outcomes between both sexes in young gastric cancer patients.

The strengths of this study include the prospectively collected large sample size, highly-qualified data obtained in a cancer center hospital of large volume, the assessment of tumor characteristics allowing subtype analyses, and the adjustment for potential confounders. However, this study had several limitations. First, because its design was cross-sectional, H. pylori status was assessed close to cancer diagnosis, making it likely that the magnitude of the association was underestimated. Second, this study did not include CagA serology which would have increased the sensitivity for the detection of H. pylori colonization.58 In Korea, most H. pylori strains are CagA-positive.59 Increasing mucosal atrophy and intestinal metaplasia with age can lead to the clearance of H. pylori.29,32 Because antibodies to CagA appear to persist longer than antibodies to H. pylori whole-cell,60 CagA seropositivity may be a better marker of H. pylori exposure among patients with severe mucosal disruption,16 which would be helpful in assessing the actual seroprevalence of H. pylori in older patients and controls. Third, factors that may confound the association between H. pylori infection and gastric cancer, including diet and salt intake, were not investigated in this study. Fourth, although we adjusted for possible confounding factors, there may have been a selection bias in our recruitment of healthy control subjects from nationwide National Cancer Screening Program. Fifth, We did not evaluate gastric atrophy and GERD objectively, therefore we could not make a subgroup analysis about the effect of H. pylori infection on cardia gastric cancer. Differences in basal characteristics and sample size between case and control groups were also a weak point.

In summary, this cross-sectional study showed that the prevalence of H. pylori is significantly higher than in gastric cancer patients than in healthy control subjects in Korea. Moreover, its prevalence was higher in younger than older gastric cancer patients, and the association between H. pylori infection and gastric cancer exists regardless of tumor location, stage, and histological differentiation in a region in which both H. pylori and gastric cancer were highly prevalent.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by grant 0910100 from the National Cancer Center, Korea.

References

- 1.You WC, Zhang L, Gail MH, et al. Gastric dysplasia and gastric cancer: Helicobacter pylori, serum vitamin C, and other risk factors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1607–1612. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.19.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa001999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crespi M, Citarda F. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: an overrated risk? Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:1041–1046. doi: 10.3109/00365529609036884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shin A, Shin HR, Kang D, Park SK, Kim CS, Yoo KY. A nested case-control study of the association of Helicobacter pylori infection with gastric adenocarcinoma in Korea. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1273–1275. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holcombe C. Helicobacter pylori: the African enigma. Gut. 1992;33:429–431. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.4.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh K, Ghoshal UC. Causal role of Helicobacter pylori infection in gastric cancer: an Asian enigma. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1346–1351. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i9.1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shin HR, Won YJ, Jung KW, et al. Nationwide cancer incidence in Korea, 1999~2001: first result using the national cancer incidence database. Cancer Res Treat. 2005;37:325–331. doi: 10.4143/crt.2005.37.6.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yim JY, Kim N, Choi SH, et al. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori in South Korea. Helicobacter. 2007;12:333–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim JH, Kim HY, Kim NY, et al. Seroepidemiological study of Helicobacter pylori infection in asymptomatic people in South Korea. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:969–975. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2001.02568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang WK, Kim HY, Kim DJ, et al. Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric cancer in the Korean population: prospective case-controlled study. J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:816–822. doi: 10.1007/s005350170003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee SA, Kang D, Shim KN, Choe JW, Hong WS, Choi H. Effect of diet and Helicobacter pylori infection to the risk of early gastric cancer. J Epidemiol. 2003;13:162–168. doi: 10.2188/jea.13.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim HY, Cho BD, Chang WK, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric cancer among the Korean population. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;12:100–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1997.tb00391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Vandersteen DP, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1127–1131. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamangar F, Dawsey SM, Blaser MJ, et al. Opposing risks of gastric cardia and noncardia gastric adenocarcinomas associated with Helicobacter pylori seropositivity. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1445–1452. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Limburg P, Qiao Y, Mark S, et al. Helicobacter pylori seropositivity and subsite-specific gastric cancer risks in Linxian, China. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:226–233. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.3.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parsonnet J, Vandersteen D, Goates J, Sibley RK, Pritikin J, Chang Y. Helicobacter pylori infection in intestinal- and diffuse-type gastric adenocarcinomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991;83:640–643. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.9.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansson LR, Engstrand L, Nyren O, Lindgren A. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in subtypes of gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:885–888. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90398-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kato M, Asaka M, Shimizu Y, Nobuta A, Takeda H, Sugiyama T. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and the prevalence, site and histological type of gastric cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(Suppl 1):85–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang JQ, Sridhar S, Chen Y, Hunt RH. Meta-analysis of the relationship between Helicobacter pylori seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1169–1179. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70422-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lunet N, Barros H. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer: facing the enigmas. Int J Cancer. 2003;106:953–960. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Derakhshan MH, Malekzadeh R, Watabe H, et al. Combination of gastric atrophy, reflux symptoms and histological subtype indicates two distinct aetiologies of gastric cardia cancer. Gut. 2008;57:298–305. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.137364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kajitani T. The general rules for the gastric cancer study in surgery and pathology. Part I. Clinical classification. Jpn J Surg. 1981;11:127–139. doi: 10.1007/BF02468883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. an attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31–49. doi: 10.1111/apm.1965.64.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma - 2nd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:10–24. doi: 10.1007/s101209800016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eom HS, Kim PS, Lee JW, et al. Evaluation of four commercial enzyme immunoassay for detection of Helicobacter pylori infection. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2001;37:312–318. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Lyon, 7-14 June 1994. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 1994;61:1–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Helicobacter and Cancer Collaborative Group. Gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori: a combined analysis of 12 case control studies nested within prospective cohorts. Gut. 2001;49:347–353. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.3.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karnes WE, Jr, Samloff IM, Siurala M, et al. Positive serum antibody and negative tissue staining for Helicobacter pylori in subjects with atrophic body gastritis. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:167–174. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90474-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang C, Yuan Y, Hunt RH. The association between Helicobacter pylori infection and early gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1789–1798. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsukuma H, Mishima T, Oshima A. Prospective study of "early" gastric cancer. Int J Cancer. 1983;31:421–426. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910310405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Genta RM, Gurer IE, Graham DY, et al. Adherence of Helicobacter pylori to areas of incomplete intestinal metaplasia in the gastric mucosa. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1206–1211. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8898634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chow WH, Blaser MJ, Blot WJ, et al. An inverse relation between cagA+ strains of Helicobacter pylori infection and risk of esophageal and gastric cardia adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 1998;58:588–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ye W, Held M, Lagergren J, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric atrophy: risk of adenocarcinoma and squamous-cell carcinoma of the esophagus and adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:388–396. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richter JE, Falk GW, Vaezi MF. Helicobacter pylori and gastroesophageal reflux disease: the bug may not be all bad. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1800–1802. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lagergren J. Adenocarcinoma of oesophagus: what exactly is the size of the problem and who is at risk? Gut. 2005;54(Suppl 1):i1–i5. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.041517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Devesa SS, Blot WJ, Fraumeni JF., Jr Changing patterns in the incidence of esophageal and gastric carcinoma in the United States. Cancer. 1998;83:2049–2053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wijnhoven BP, Louwman MW, Tilanus HW, Coebergh JW. Increased incidence of adenocarcinomas at the gastro-oesophageal junction in Dutch males since the 1990s. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:115–122. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200202000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Correa P. Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process--First American Cancer Society Award Lecture on Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6735–6740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohata H, Kitauchi S, Yoshimura N, et al. Progression of chronic atrophic gastritis associated with Helicobacter pylori infection increases risk of gastric cancer. Int J Cancer. 2004;109:138–143. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tatsuta M, Iishi H, Okuda S, Taniguchi H, Yokota Y. The association of Helicobacter pylori with differentiated-type early gastric cancer. Cancer. 1993;72:1841–1845. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930915)72:6<1841::aid-cncr2820720608>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iseki K, Tatsuta M, Iishi H, Baba M, Ishiguro S. Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with early gastric cancer by the endoscopic phenol red test. Gut. 1998;42:20–23. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sasazuki S, Inoue M, Iwasaki M, et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori infection combined with CagA and pepsinogen status on gastric cancer development among Japanese men and women: a nested case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1341–1347. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Craanen ME, Blok P, Dekker W, Tytgat GN. Helicobacter pylori and early gastric cancer. Gut. 1994;35:1372–1374. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.10.1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Linton PJ, Dorshkind K. Age-related changes in lymphocyte development and function. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:133–139. doi: 10.1038/ni1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakamura T, Yao T, Niho Y, Tsuneyoshi M. A clinicopathological study in young patients with gastric carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 1999;71:214–219. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(199908)71:4<214::aid-jso2>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lo SS, Kuo HS, Wu CW, et al. Poorer prognosis in young patients with gastric cancer? Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:2690–2693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang JY, Hsieh JS, Huang CJ, Huang YS, Huang TJ. Clinicopathologic study of advanced gastric cancer without serosal invasion in young and old patients. J Surg Oncol. 1996;63:36–40. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9098(199609)63:1<36::AID-JSO6>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yokota T, Takahashi N, Teshima S, et al. Early gastric cancer in the young: clinicopathological study. Aust N Z J Surg. 1999;69:443–446. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1622.1999.01553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Medina-Franco H, Heslin MJ, Cortes-Gonzalez R. Clinicopathological characteristics of gastric carcinoma in young and elderly patients: a comparative study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:515–519. doi: 10.1007/s10434-000-0515-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim DY, Joo JK, Ryu SY, Park YK, Kim YJ, Kim SK. Clinicopathologic characteristics of gastric carcinoma in elderly patients: a comparison with young patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:22–26. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bani-Hani KE. Clinicopathological comparison between young and old age patients with gastric adenocarcinoma. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2005;35:43–52. doi: 10.1385/IJGC:35:1:043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim JH, Boo YJ, Park JM, et al. Incidence and long-term outcome of young patients with gastric carcinoma according to sex: does hormonal status affect prognosis? Arch Surg. 2008;143:1062–1067. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.11.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matsui M, Kojima O, Kawakami S, Uehara Y, Takahashi T. The prognosis of patients with gastric cancer possessing sex hormone receptors. Surg Today. 1992;22:421–425. doi: 10.1007/BF00308791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Furukawa H, Iwanaga T, Hiratsuka M, et al. Gastric cancer in young adults: growth accelerating effect of pregnancy and delivery. J Surg Oncol. 1994;55:3–6. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930550103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maeta M, Yamashiro H, Oka A, Tsujitani S, Ikeguchi M, Kaibara N. Gastric cancer in the young, with special reference to 14 pregnancy-associated cases: analysis based on 2,325 consecutive cases of gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 1995;58:191–195. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930580310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lindblad M, Ye W, Rubio C, Lagergren J. Estrogen and risk of gastric cancer: a protective effect in a nationwide cohort study of patients with prostate cancer in Sweden. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:2203–2207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Romero-Gallo J, Perez-Perez GI, Novick RP, Kamath P, Norbu T, Blaser MJ. Responses of endoscopy patients in Ladakh, India, to Helicobacter pylori whole-cell and Cag A antigens. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2002;9:1313–1317. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.9.6.1313-1317.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chang YW, Han YS, Lee DK, et al. Role of Helicobacter pylori infection among offspring or siblings of gastric cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2002;101:469–474. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Klaamas K, Held M, Wadstrom T, Lipping A, Kurtenkov O. IgG immune response to Helicobacter pylori antigens in patients with gastric cancer as defined by ELISA and immunoblotting. Int J Cancer. 1996;67:1–5. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960703)67:1<1::AID-IJC1>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]