Abstract

The clinical phenotype in sepsis that is observed as LPS tolerance is determined by silencing of proinflammatory genes like IL-1 beta (IL-1β). This study shows that facultative heterochromatin (fHC) silences IL-1β expression during sepsis, where we find dephosphorylated histone H3 serine 10 and increased binding of heterochromatin protein-1 (HP-1) to the promoter. In both human sepsis blood leukocytes and an LPS tolerant human THP-1 cell model, we show that IκBα and v-rel reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene homolog B (RelB) function as dominant labile mediators of fHC formation at the IL-1β promoter. Protein synthesis inhibition decreases levels of IκBα and RelB, converts silent fHC to euchromatin, and restores IL-1β transcription. We further show TLR dependent NFκB p65 and histone H3 serine 10 phosphorylation binding at the promoter. We conclude that the resolution phase of sepsis, which correlates with survival in humans, may depend on the plasticity of chromatin structure as found in fHC.

Keywords: interleukin-1, LPS tolerance, epigenetics, facultative heterochromatin, sepsis

INTRODUCTION

1.1 Sepsis and LPS reprogramming

Under severe environmental stress, such as sepsis with severe systemic inflammation (SSI), regulation of innate immunity in the host is altered [1]. The resulting suppression of inflammatory responses may increase susceptibility to secondary infection, sustain multi-organ failure, and increase mortality. Therapies based on disrupting the acute pro-inflammatory response was relatively unsuccessful [2] possibly due, in part, to the complex and dynamic regulation imposed an innate immune responses.

Our understanding of the immune dysregulation characteristic of sepsis is rapidly evolving. Components range from modified cytosolic signaling to changes in chromatin structure in immune cell nuclei [3]. Studies in human, mouse, and cell-culture models represent the human disease differently, although one common feature is the failure of robust pro-inflammatory response to LPS [4]. This phenomenon, known as LPS tolerance, is acquired in vivo or ex vivo by repeated or prolonged LPS stimulation of naïve phenotypes. It is characterized by altered LPS induced intracellular signaling and repressed pro-inflammatory gene expression, while expression of other genes with distinct functional characteristics, many with anti-inflammatory activity, is sustained [5]. LPS induces both pro- and anti-inflammatory genes through Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), so tolerance is regulated by mechanisms that act at the level of specific genes or classes of genes, rather than signals [6]. Since both suppression of pro-inflammatory genes and expression of anti-inflammatory and other functional groups of genes have been observed, we favor LPS reprogrammed over LPS tolerant as a more accurate description of this phenotype.

1.2 LPS reprogramming and epigenetic silencing of pro-inflammatory genes

Consistent with phenotypic gene reprogramming, epigenetic mechanisms appear to regulate repression [5]. Others (in mice) and we (in humans) found distinct chromatin modifications associated with gene silencing at the promoters of many pro-inflammatory, LPS-reprogrammed genes [6–9]. In cultured cells pretreated with LPS, a second LPS challenge failed to induce epigenetic changes characteristic of gene activation [7]. Further experiments showed that the initial LPS dose induced a negative regulator(s) that mediated transcription silencing upon subsequent LPS challenge [10, 11].

Using a THP-1 human promonocyte culture model, we previously identified IκBα as one labile negative regulator that participates in LPS reprogramming [10]. Its expression is tightly controlled and at one level, involves rapid protein turnover [12]. During LPS activation, IκBα degradation allows NFκB activation to initiate pro-inflammatory gene expression [13]; thereafter, it must be re-synthesized to inhibit NFκB activation and limit the inflammatory response. Our previous study [10] showed that blocking IκBα resynthesis with cycloheximide (CHX) could re-establish the LPS response; specifically, it restored transcription of the pro-inflammatory gene, IL-1β, in reprogrammed THP-1 cells.

More recently, we found that RelB is induced by LPS in normal cells and accumulates at high levels in the nucleus in reprogrammed cells [11, 14]. Its expression in naïve cells is sufficient to reprogram them; as a negative transcription regulator, it can bind to, and inhibit transcription of IL-1β and TNFα genes. Consistent with pro-inflammatory gene silencing, we found increased RelB levels in peripheral blood leukocytes from sepsis patients.

Gene silencing in reprogrammed THP-1 cells is accompanied by epigenetic marks consistent with the formation of facultative heterochromatin (fHC) at repressed promoters [7–9, 15, 16]. LPS stimulation of naïve cells increased histone H3 serine 10 phosphorylation; in reprogrammed cells, serine 10 phosphorylation decreased, consistent with the histone code changes from activation to repression. Formation of repressive fHC is supported by increased binding of heterochromatin protein-1 (HP-1), a protein implicated in the formation and/or maintenance of fHC, at repressed promoters in LPS reprogrammed cells [15].

1.3 fHC formation at the IL-1β promoter is controlled by labile proteins

This report implicates epigenetic modifications in our observation that inhibiting protein synthesis reverses gene silencing and restores LPS-inducible gene expression of IL-1β in reprogrammed cells. The return to LPS sensitivity was associated with (a) decreased protein levels of nuclear RelB and IκBα and their decreased binding to the IL-1β promoter; and (b) recruitment of the transcription activator, NFκB p65, to the IL-1β promoter and (c) re-establishment of H3 serine10 phosphorylation, an epigenetic nucleosome modification correlated with gene expression. Although HP-1 levels were not sensitive to the inhibition of protein synthesis, it was dissociated when IL-1β expression was restored. These results indicate that pro-inflammatory genes assume fHC characteristics in LPS-reprogrammed cells; that IκBα and RelB participate in fHC formation; and that sustained expression of the labile proteins is required to maintain the silent state of fHC at specific gene loci.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Cell isolation, culture, and treatment

THP-1 cells obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD) were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with 10U/ml penicillin G, 10μg/ml streptomycin, 2mM L-glutamine, and 10% FCS (low LPS FCS; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator. LPS reprogrammed THP-1 cells were made by pretreatment for 16h with LPS (1.0 μg/ml of Gram-negative lipopolysaccharide [E. coli 0111:B4; Sigma, St. Louis, MO]). Non-specific (control) and IκB siRNAs (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) were transfected using an AMAXA THP-1 transfection kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Normal (no pretreatment) and reprogrammed THP-1 cells were washed with FCS free RPMI-1640 medium, resuspended in FCS supplemented RPMI-1640 media at 1×106 cells/ml, and stimulated with LPS (1.0 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of cycloheximide (CHX, 10uM; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) to inhibit protein synthesis for the times indicated in the figure legends. Low passage number and log-phase cells were used for all experiments. All solutions were routinely monitored for LPS contamination by the Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (sensitivity <1 pg/ml).

2.2 Peripheral Blood Leukocyte (BL) and PMN isolation

Four patients with sepsis were selected based on the presence of identifiable infection in blood or tissue (e.g., lung) and accompanying sustained hypotension, despite robust administration of fluids; all patients required use of vasopressors and had failure of two or more organs (lung, liver, kidney). Using these criteria, 95% of patients reproducibly have reduced IL-1β production in response to LPS in doses from 10 ng/ml to 1 ug/ml [17]. Patients enrolled in this study were positive for Gram-positive and/or Gram-negative sepsis. Patients with known HIV infection, hematological malignancies affecting leukocyte counts, current cytotoxic chemotherapy, or high-dose glucocorticoid treatment were excluded. Patient clinical information is shown on Table 1. The Institutional Review Board endorsed the study for Clinical Research associated with the General Clinical Research Center of the Medical Center.

Table I.

| PATIENT | sex | age | infection site | infection type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | M | 28 | lung | (+) |

| B | M | 28 | lung | (−) |

| C | F | 45 | lung | (−) |

| D | M | 74 | lung | (+) |

A venous or arterial heparinized blood sample (up to 30ml) was drawn from sepsis patients or healthy control subjects and immediately processed. BL were isolated by isolymph sedimentation (Gallard-Schlesinger Industries, Carle Place, Inc., NY) followed by centrifugation for 5 min at 200xg at room temperature. The remaining erythrocytes were lysed in LPS free H2O for 20 sec before isotonicity was restored with 3.6% NaCl. Isolated BL were washed and counted in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). The proportion of PMN in BL vary in patients, with a predominance of PMN (85–95%) compared to healthy control subjects (60–80%). In control subjects, BL were further separated into PMN by a second centrifugation over 3 ml isolymph for 30 min at 400g. The PMN pellet was washed and counted in PBS and adjusted to approximate proportions of PMN and mononuclear cells. Our previous studies show that highly purified preparations of PMN or BL are similarly transcriptionally repressed [18]. Cells were immediately used for mRNA and ChIP assays described below.

2.3 Western blot analysis

Nuclear extract proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to an Immuno-Blot® PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). RelB, IκBα, NfκB p65, phosphoSer(10)-H3, HP-1, β-actin, and HRP conjugated secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) were used to visualize proteins using Western blot protocols specified by the manufacturer. Blots were stripped and reprobed with control antibodies (b-actin) as indicated. Protein levels on the blots were quantified using ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics, Amersham Pharmaceutical Biotech., Sunnyvale, CA). Statistical analysis and graphs were performed using Microsoft Excel XP.

2.4 Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP assays)

ChIP assays (Upstate Biotechnology) were used to assess IκBα, RelB, p65 binding, and phosphohistone H3 binding to the IL-1β promoter. They were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions with the following modifications: Cells (5X106cells/condition) were fixed by adding formaldehyde (HCHO, from a 37% HCHO/10% methanol stock; Calbiochem) to the medium for a final formaldehyde concentration of 1% and incubated at room temperature for 10 min with gentle shaking. The chromatin was sheared by sonication using a Diagenode Bioruptor (UCD-200TM-EX; TOSHO DENKI CO., LTD) at high power cycles of 30′-on and 30′-off for 23 min that generated DNA fragments of ~0.5–1.5 kb. Each condition was divided to provide an input sample that was not incubated with antibodies. The other sample was incubated overnight with antibodies specific for RelB, IκBα, HP-1, p65, and phospho(S10)-histone H3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Purified DNA was resuspended in 10μl dH2O.

2.5 Real-time PCR

IL-1β promoter in the ChIP DNA was quantified by real-time PCR. Input or immunoprecipitated DNA was used for each reaction. The probe set used to detect IL-1β promoter sequences has been described [7]. The real-time PCR reaction (total 25μl) contained 3μl DNA, 12.5μl 2XTaqMan Universal Master Mix, 300nM of each primer, and 100nM dNTPs. The real-time PCR procedure was: 2 min at 50°C, 10min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C, using ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). Data were normalized to the input DNA and presented as fold-change relative to DNA from untreated cells.

Total RNA was isolated at 2 h after stimulation of THP-1 cells, patient BL, and control BL and/or PMN, using RNA STAT-60 (Tel-Test, Friendswood, TX). Real-time PCR was performed using IL-1β and GAPDH-predesigned TaqMan primer/probe kits (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Data were normalized to GAPDH mRNA and presented as fold-change relative to mRNA from untreated cells.

2.6 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis and graphic presentations were performed using GraphPad Prism 4 (real-time mRNA analyses) or Microsoft Excel XP (real-time ChIP). Significance was taken at p<0.05 (one-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons) or Student’s t-test for paired analyses). All data shown are results from at least 3 independent observations and expressed as the mean ± SEM.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 IL-1β transcription increases with the inhibition of protein synthesis in LPS-reprogrammed cells

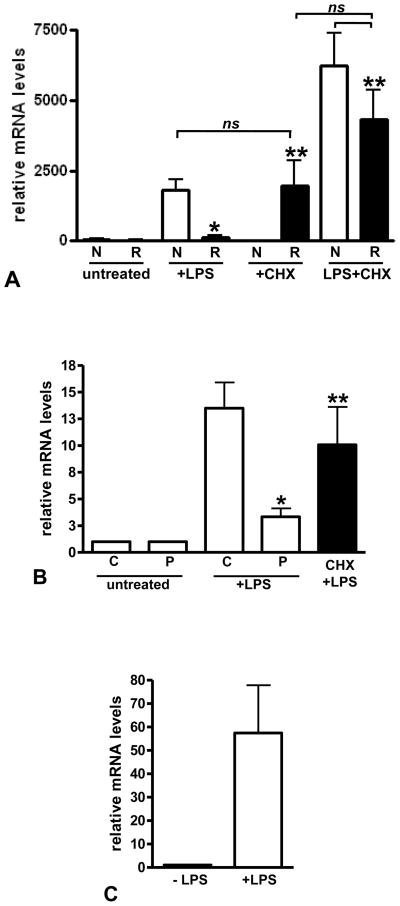

We previously used Northern blot to assess IL-1β mRNA levels stimulated by LPS and suggested that IκBα was a negative, labile regulator of pro-inflammatory gene transcription in LPS-reprogrammed THP-1 cells. We now show by real-time PCR that reprogrammed cells do not transcribe IL-1β and confirm that inhibited protein synthesis can restore LPS response. Reprogrammed THP-1 cells (Figure 1A) or sepsis peripheral blood leukocytes (BL; Figure 1B) were treated with LPS in the presence or absence of cycloheximide (CHX). Inhibiting protein synthesis by CHX restored LPS response, confirming our previous study that implicated a labile repressor(s) in mediating gene reprogramming [10].

FIGURE 1.

IL-1β expression is increased by protein synthesis inhibition in reprogrammed cells. A. THP-1 cells were treated as indicated. Total RNA was isolated and IL-1β mRNA measured by real time PCR as described in the methods. Data shown are IL-1β mRNA normalized to GAPDH mRNA in each sample and expressed as relative mRNA levels. Untreated normal THP-1 (N) and reprogrammed THP-1 cells (R) have very low levels of IL-1β mRNA. Normal cells show induced levels of IL-1β mRNA when treated with LPS, whereas reprogrammed cells are significantly repressed (*p<0.001, t-test). Protein synthesis inhibition with CHX reverses IL-1β repression (solid bars) in reprogrammed cells. There is a significant difference (**p<0.05) between LPS alone and CHX or LPS+CHX treated reprogrammed cells; there is no significant difference (p>0.05) between LPS treated normal cells, CHX treated reprogrammed cells or LPS+CHX treated normal or reprogrammed cells (one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni multicomparison post-test). B. BL were isolated and treated as indicated. Total RNA was isolated and IL-1β mRNA measured by real time PCR as described in the methods. Data shown are IL-1β mRNA normalized to GAPDH mRNA in each sample and expressed as fold increase relative to untreated mRNA levels. Control BL (C) show induced levels of IL-1β mRNA when treated with LPS, whereas SSI patient BL (P) are significantly repressed (*p<0.005, t-test) that is reversed by protein synthesis inhibition (solid bars). There is no significant difference (p>0.05) between LPS treated control BL and LPS+CHX treated SSI patient BL; there is a significant difference (**p<0.05) between LPS alone and LPS+CHX treated patient BL (one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni multicomparison post-test). C. Control PMN IL-1β mRNA levels induced by LPS is shown for comparison. There is no significant difference (p>0.05) in IL-1β mRNA levels induced by LPS in control BL and PMN.

We extended this paradigm to blood leukocytes obtained from the four patients with sepsis and multi-organ failure. IL-1β mRNA levels, assessed by real-time PCR in normal THP-1 cells and control peripheral blood leukocytes (BL), both exposed to LPS, are shown for comparison. The septic BL are dominated by PMN, which, we previously reported, are refractory to LPS induced IL-1β expression much in the same way as mononuclear cells [19]. In comparison, Figure 1C shows that isolated PMN from control subjects are LPS responsive. Together, these results support the concept that in human sepsis and its THP-1 cell model, de novo synthesis of inhibitors is part of the repressed phenotype of pro-inflammatory genes in LPS-reprogrammed cells.

At the onset of sepsis, TLR receptors signal threatened cells to rapidly transcribe a set of poised pro-inflammatory genes, inciting the acute phase of inflammation [20]. If the infectious threat is limited, the acute pro-inflammatory genes expressed in the systemic circulation return to the basal state within hours, and physiologic resolution follows [5]. If the threat is severe and systemic, a gene-specific epigenetic reprogram that may last from days to weeks will evolve within 3–6 hours. We have followed it in humans for up to 21 days. During this stage, certain gene classes (e.g., rapid-response, acute pro-inflammatory) are transcriptionally silenced, while others (e.g., anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial) remain activated [18]. This sustained epigenetic paradigm produces a distinct clinical phenotype and predicts poor outcome. Our finding here that silenced transcription in human sepsis can revert to responsiveness has not been previously reported, to our knowledge, and may have implications for future sepsis intervention.

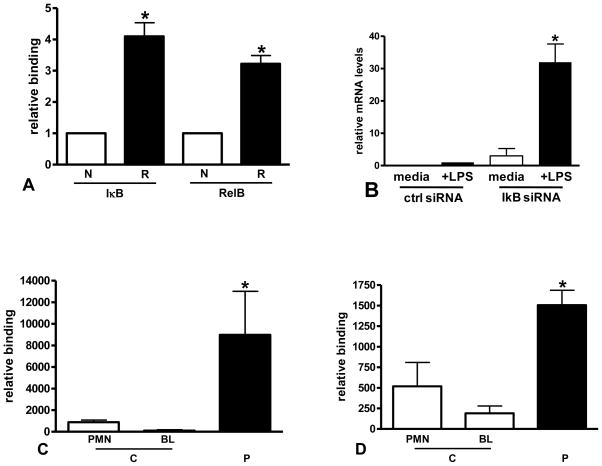

3.2 IκBα and RelB binding to the IL-1β promoter increases in reprogrammed cells

Using chromatin immunoprecipitation assays (ChIP) assays, we tested whether IκBα and RelB bind to the IL-1β promoter. In LPS-reprogrammed THP-1 cells (Figure 2A) and septic BL (Figure 2C/D) compared to normal THP-1 and control BL and PMN, we found significant binding of both IκBα and RelB to the IL-1β promoter, supporting a combined role in inhibiting pro-inflammatory genes during LPS reprogramming. We had previously shown RelB binding to the promoter in reprogrammed cells and confirmed a role for RelB in reprogrammed cells by siRNA knockdown [11]. Here we confirm a role for IκB in reprogrammed cells by siRNA knockdown (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2.

IκB and RelB binding to the IL-1β promoter are increased in reprogrammed cells. A. ChIP assays were used to measure IκB and RelB binding to the IL-1β promoter in normal (N) and reprogrammed (R) THP-1 cells as described in the methods. A significant increase in binding was found for both proteins in reprogrammed cells (*p<0.01, t-test). Data shown are normalized to input DNA and expressed as fold increase relative to binding in normal cells. B. Reprogrammed cells were transfected with IκB siRNA and stimulated with LPS. IκB knockdown significantly (*p<0.001) increased IL-1β expression when compared to cells transfected with control siRNA (ctrl siRNA). C and D. ChIP assays were used to measure IκB (B) and RelB (C) binding to the IL-1β promoter in control (C) and SSI patient BL (P) as described in the methods. A significant increase in binding was found for both proteins in SSI patient BL (*p<0.05, one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni multicomparison posttest). Low levels of binding for IκB and RelB to the IL-1β promoter in control PMN is also shown.

In innate immunity leukocytes, RelB protein is not expressed in the basal homeostatic phase but induced as sepsis evolves [11]. Once it accumulates in the nucleus, its promoter binding is co-incident with retained p50 on the IL-1β and TNFα proximal promoters in a presumed dimer switch with p65. RelB mediates transcription repression by forming a complex of HP1 and G9a histone methyl transferase [14]; the Rel homology domain (RHD) directly interacts with the N terminal of G9a, generating the histone H3K9 di-methylated silent state and recruiting heterochromatin protein-1 (HP-1) to methylated sites. Here, we show for the first time that both IκBα and RelB are enriched at the IL-1β promoter when sepsis silences transcription and in THP-1 LPS-reprogrammed cells. This result prompted us to test whether both IκBα and RelB are labile and require continued synthesis to sustain transcription silencing.

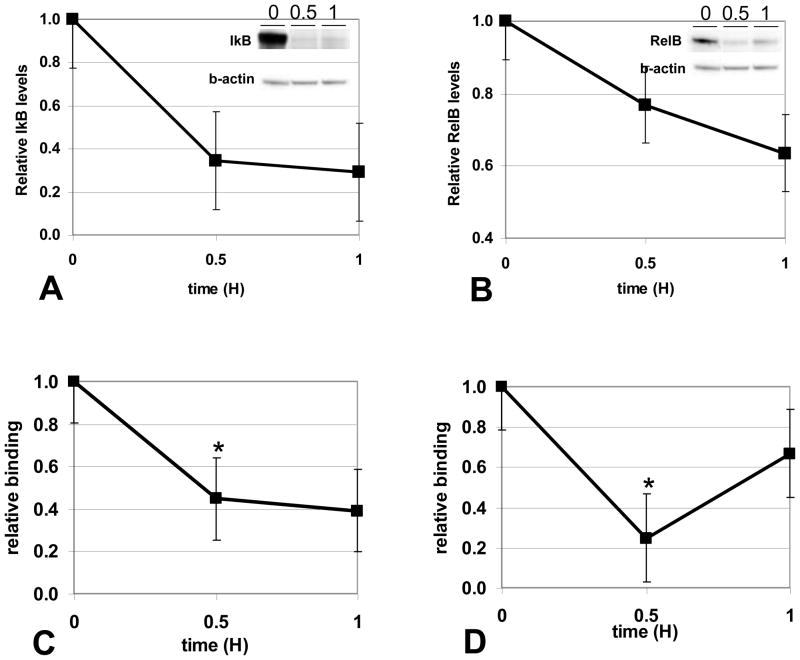

3.3 Inhibiting protein synthesis decreases IκBα and RelB levels and binding to the IL-1β promoter in reprogrammed cells

To determine whether IkBa and RelB are synthesized de novo as inhibitors in LPS-reprogrammed cells, we tested whether inhibiting protein synthesis by CHX would decrease their nuclear levels. We treated the cell models of septic BL and LPS-reprogrammed THP-1 with CHX and assessed IκBα or RelB (Figure 3A, 3B, respectively) levels in nuclear extracts and found marked decreases. Thus, enhanced synthesis of IκBα and de novo RelB production are important in LPS- reprogrammed cells, where they inhibit the expression of pro-inflammatory genes like IL-1β. Using ChIP assays, we further found that CHX treated reprogrammed cells have decreased IκBα and RelB binding to the IL-1β promoter (Figure 3C, 3D, respectively). These results correlate reversal of gene silencing with decreased RelB and Iκbα at the promoter of LPS-inducible genes. RelB and IκBα are de novo synthesized inhibitors that participate in gene silencing by binding pro-inflammatory gene promoters in reprogrammed cells.

FIGURE 3.

Inhibition of protein synthesis decreases IκB and RelB nuclear protein and promoter binding in reprogrammed cells. Reprogrammed THP-1 cells were treated with LPS+CHX for the indicated times, nuclear extracts prepared, and IκB (A) or RelB (B) protein levels in nuclear extracts (30ug) were quantitated by W. blot as described in the methods. Inhibition of protein synthesis decreases IkB and RelB nuclear protein levels. Results shown are the average of 3 separate experiments. A representative blot is shown (inset). IκB (C) or RelB (D) binding to the IL-1β promoter was measured by ChIP assays in reprogrammed THP-1 cells treated with LPS+CHX. Protein synthesis inhibition significantly (*p<0.05) decreases both IκB and RelB binding to the IL-1β promoter. Results shown are the average of three independent experiments.

To our knowledge, this is first report of IκBα dependent ChIP that correlates with transcription repression. IκBα does not bind well to RelB or DNA [21], and its p65 binding partner is not present on LPS-silenced promoters [7]. Thus, its function in repressing transcription at the level of the promoter is unknown. Like the BCL3 member of the IκB family, IκBα may bind to the p50 homodimer on IL-1β to prevent its removal by proteosome degradation [22]. If so, it could help to retain the p50 homodimer platform for accumulation of RelB. RelB stabilizes IκBα in fibroblasts [23]. We also found a dual function for RelB in reprogrammed cells, where in addition to its repressive function on IL-1β, RelB also activates transcription and enhances levels of IκBα [24]. Moreover, RelB can form an auto-activation loop at its own promoter [25]. Together, these two feed-forward loops may maintain production of both labile proteins, which are required to repress transcription during LPS reprogramming. In any event, the mechanism responsible for sustaining expression of both the IκBα and RelB genes appears critical for maintaining reprogramming during the course of sepsis. Further studies of this paradigm may inform new therapies.

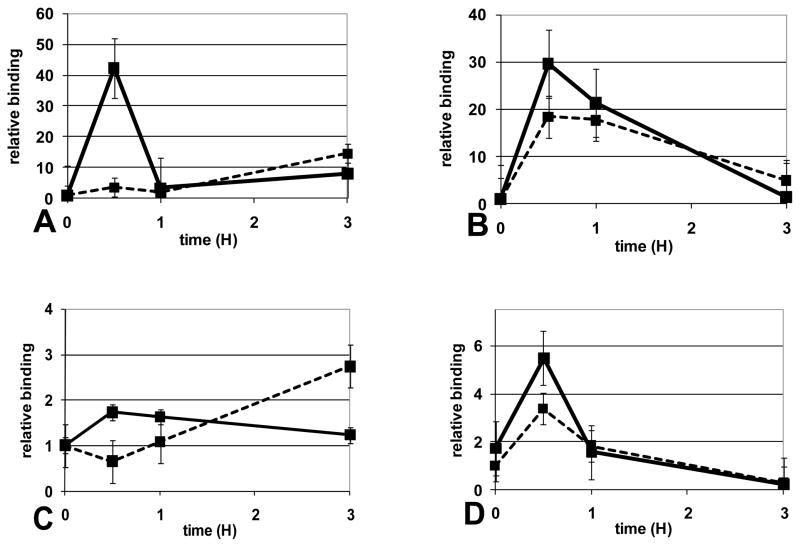

3.4 Inhibiting protein synthesis restores LPS response in reprogrammed cells

Our previous reports showed that reprogrammed cells still respond to LPS and can translocate NFkB p65 to the nucleus [26]. ChIP assays showed that, despite translocation, p65 could not bind the IL-1β promoter during human sepsis and in the SSI THP1 model [7]. The inability of p65 to activate transcription in THP1 cells correlated with dephosphorylated histone H3, a salient feature of transcription repression. Here, we tested whether inhibiting protein synthesis in LPS reprogrammed cells would restore LPS induced binding of p65 to the IL-1β promoter. As shown in Figure 4, we found that treatment with CHX in the absence (Figure 4A/C) or presence of LPS (Figure 4B/D) could restore LPS induced p65 binding and histone H3 serine10 phosphorylation at the IL-1β promoter. Taken together, these results show that de novo synthesized RelB and IκBα repress the IL-1β promoter in reprogrammed cells. Inhibiting protein synthesis decreases RelB and IκBα levels and promoter binding, and restores p65 binding, histone H3 phosphorylation and IL-1β expression. This paradigm occurs in sepsis leukocytes and reprogrammed THP1 cells.

FIGURE 4.

Inhibition of protein synthesis increases LPS induced p65 binding and phosphorylation of histone H3 at the IL-1β promoter in reprogrammed cells. NFκB p65 binding (A, B) and H3 (serine10) phosphorylation (C, D) at the IL-1β promoter was measured by ChIP assay in reprogrammed THP-1 cells treated with CHX alone (A, C) or LPS+CHX (B, D) for the indicated times. Inhibition of protein synthesis is unable to induce p65 or histone phosphorylation in normal cells (dotted line) when compared to reprogrammed cells (solid line). Protein synthesis inhibition restores both p65 binding and histone phosphorylation at the IL-1β promoter in reprogrammed cells (solid line). Results shown are the average of three (A, B, C) and 4 (D) independent experiments.

3.5 fHC formation in LPS reprogrammed cells

fHC are genomic regions with distinctive epigenetic marks that correlate with transcription silencing [27]. Their formation at or near pro-inflammatory genes seems necessary for transcription repression. During LPS reprogramming, we identified HP-1 as a transacting protein that facilitates fHC formation at or near silenced pro-inflammatory genes [8]. Unlike constitutive heterochromatin, fHC retains the potential to activate transcription and can revert to euchromatin.

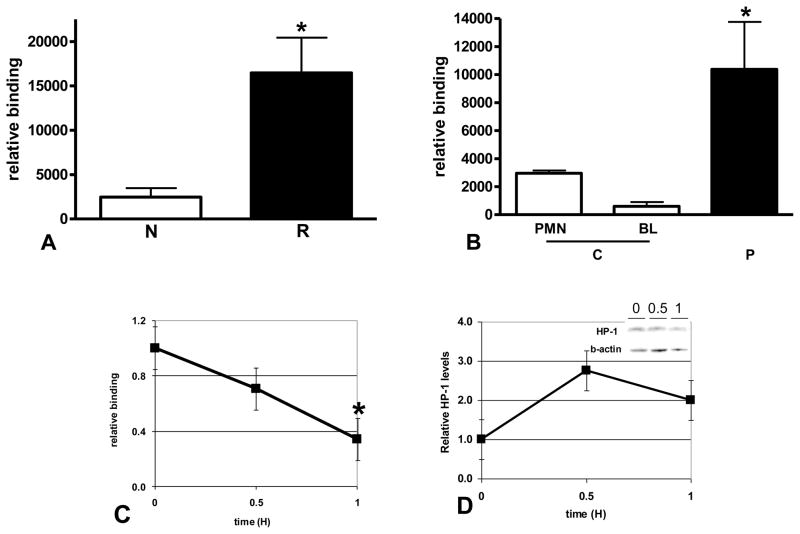

We therefore examined the IL-1β promoter for HP-1 association during LPS reprogramming in sepsis. Consistent with its role in fHC formation and gene silencing, we found HP-1 significantly increased at the IL-1β promoter in reprogrammed THP-1 cells (Figure 5A) and in septic BL compared to controls (Figure 5B). HP-1 binding diminished with CHX treatment (Figure 5C); however, unlike RelB and IκBα, HP-1 protein levels were not sensitive to CHX (Figure 5D). This result is consistent with HP-1 as a chromatin structural protein and recruitment to repressed promoters dependent on interaction with other proteins and/or other chromatin modifiers that regulate transcription [28]. The present study demonstrates fHC formation as the mechanism for repression during and implicates RelB and IκB in regulating in this process. In contrast to HC (heterochromatin) which remains transciptionally silent, a salient feature of fHC is the ability to be transcribed from a repressed state. As we demonstrate in this study, fHC formation, as defined by HP-1 association, occurs at the IL-1β promoter in reprogrammed cells. CHX treatment decreases promoter binding of labile proteins IκB and RelB, HP-1 is dissociated from the promoter and IL-1β expression is restored.

FIGURE 5.

Formation of fHC represses IL-1β expression in LPS reprogrammed cells. A. ChIP assays were used to show a significant increase in HP-1 binding to the IL-1β promoter in reprogrammed (R) THP-1 cells (*p<0.02) when compared to normal (N). B. ChIP assays were used to compare HP-1 binding to the IL-1 promoter in control (C) and and SSI patient BL (P). A significant increase in binding was found in SSI patient BL (*p<0.05, one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni multicomparison post-test). Low levels of HP-1 binding to the IL-1β promoter in control PMN is also shown. C. ChIP assays were used to measure HP-1 binding to the IL-1β promoter in reprogrammed THP-1 cells treated with LPS+CHX for the indicated times. Protein synthesis inhibition significantly (*p<0.05) decreases HP-1 binding to the IL-1β promoter. Results shown are the average of three independent experiments. D. Reprogrammed THP-1 cells were treated with LPS+CHX for the indicated times, nuclear extracts prepared, HP-1 protein levels in nuclear extracts were quantitated by W. blot as described in the methods. HP-1 levels are not sensitive to treatment with CHX. Results shown are the average of 4 separate experiments. A representative blot is shown (inset).

These findings emphasize the importance of gene specific chromatin modification in the control of the temporal stages of inflammation and further support the observation that “tolerant” and “non-tolerant” genes appear in response to inflammation (reviewed by [3]). Our results support that the cooperative interaction between transcription factors and chromatin-modifying enzymes generate the epigenetic specificity of the inflammatory process in the inciting, evolving and resolving phases.

We and others are beginning to delineate the epigenetic regulation of the inflammation response. This study emphasizes the localized silencing of pro-inflammatory genes by fHC in a highly destructive form of human and animal inflammation. Unlike heterochromatin, fHC formation allows repressed genes to respond under specific circumstances. The physiological conditions that ultimately reverse epigenetic repression during sepsis are unknown but correlate with survival.

The pathogenesis of common human diseases has traditionally been linked to genetic mutations, and only recently have epigenetic modifications of chromatin and DNA been implicated in physiologic dysfunction related to such chronic conditions as diabetes and cancer [29, 30]. Many factors influencing the epigenome have been identified. Notably, DNA methylation has long been correlated with the aging process, although the exact mechanisms and cause-effect relationships remain unclear. Two major epigenetic mechanisms are the posttranslational modification of histone proteins in chromatin and DNA methylation that are regulated by distinct but coupled, pathways [30, 31]. The epigenetic state is clearly a central regulator of differentiation and development, and emerging evidence supports its key role in human pathologies, including inflammatory disorders [5, 32].

CONCLUSION

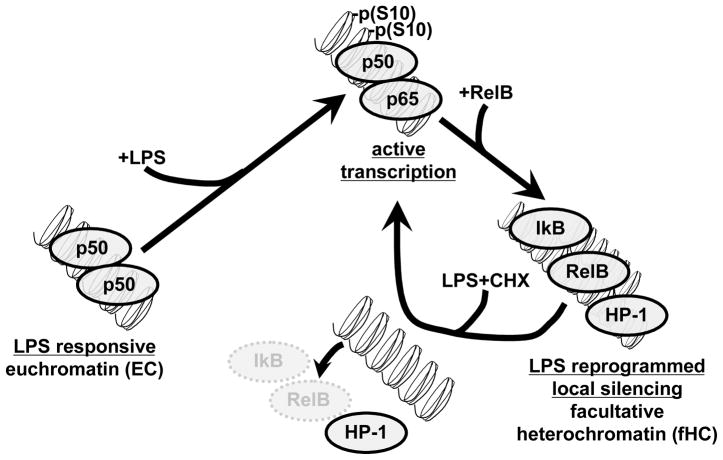

This study, summarized in Figure 6, provides the first evidence for the reversible nature of epigenetic-based transcription silencing of acute proinflammatory genes during sepsis. This restorative process occurs when repressed fHC reverts to responsive euchromatin following depletion of RelB and IκBα. Transcription silencing of acute proinflammatory genes like IL-1β, which incite sepsis, is mediated, at least in part, by de novo synthesis of IκBα and RelB. These LPS responsive, labile proteins are required to mediate the formation of fHC and repress transcription. The IL-1β expression is restored when IκBα and RelB are degraded concomitant with loss of HP-1 binding at the promoter. Gene expression is also correlated with re-binding of p65 and phosphorylation of histone H3 serine 10 at the IL-1β promoter. Based on these results, we suggest that as sepsis resolves, the loss of dominant negative repressors like RelB and a switch from fHC to euchromatin may correlate with a return to normal innate immune response. This paradigm may inform novel therapies for sepsis.

FIGURE 6.

LPS reprogramming and formation of fHC. At the onset of SSI and in LPS treated THP-1 cells, NFκB is activated and transcription of proinflammatory genes like TNFα and IL-1β is observed. Transcription is associated with NFκB p65 binding and histone H3 S10 phosphorylation at the promoter. Induction of these genes is followed by a period of LPS reprogramming that is characterized by repressed transcription, where SSI patient BL and reprogrammed THP-1 cells are no longer responsive to LPS stimulation. Reprogramming is associated with RelB, IκB and HP-1 binding to the promoter. In this study, we show that inhibition of protein synthesis (by addition of CHX) can restore LPS responsiveness in reprogrammed cells. We found that degradation of RelB and IκB is accompanied by release of HP-1 binding to the promoter. p65 binding and histone H3 S10 phosphorylation at the promoter correlated with the increased transcription of IL-1. As depicted in this model, our results suggest that in normal healthy controls and in naïve cells, proinflammatory genes have the molecular features of euchromatin (EC) that are responsive to LPS activation. In SSI and in LPS reprogrammed cells, silenced proinflammatory genes assume features of facultative heterochromatin (fHC). Degradation of the labile transacting factors, RelB and IκB, is accompanied by release of the heterochromatin protein, HP-1. Restoration of LPS response is characterized by binding of p65 and H3 S10 phosphorylation at the IL-1 promoter and increased IL-1 mRNA.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jean Hu and Sue Cousart for their contributions to our research. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01AI-09169 (CEM), R01AI-065791 (CEM), R01AI-079144 (CEM), and MO-1RR 007122 to the Wake Forest University General Clinical Research Center. The authors have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- CHX

cycloheximide

- fHC

facultative heterochromatin

- HP-1

heterochromatin protein 1

- BL

Peripheral blood leukocytes

- RelB

v-rel reticloendotheliosis viral oncogene homolog B

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE. The pathophysiology and treatment of sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:138–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bone RC. Why sepsis trials fail. JAMA. 1996;276:565–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foster SL, Medzhitov R. Gene-specific control of the TLR-induced inflammatory response. Clin Immunol. 2009;130:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.West MA, Heagy W. Endotoxin tolerance: A review. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:S64–S73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCall CE, Yoza BK. Gene silencing in severe systemic inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:763–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200610-1436CP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster SL, Hargreaves DC, Medzhitov R. Gene-specific control of inflammation by TLR-induced chromatin modifications. Nature. 2007;447:972–8. doi: 10.1038/nature05836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan C, Li L, McCall CE, Yoza BK. Endotoxin tolerance disrupts chromatin remodeling and NF-kappaB transactivation at the IL-1beta promoter. J Immunol. 2005;175:461–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Gazzar M, Yoza BK, Chen X, Hu J, Hawkins GA, McCall CE. G9a and HP1 couple histone and DNA methylation to TNFalpha transcription silencing during endotoxin tolerance. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:32198–208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803446200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Gazzar M, Yoza BK, Hu JY, Cousart SL, McCall CE. Epigenetic silencing of tumor necrosis factor alpha during endotoxin tolerance. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:26857–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704584200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larue KEA, McCall CE. A Labile Transcriptional Repressor Modulates Endotoxin Tolerance. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1994;180:2269–75. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.6.2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoza BK, Hu JY, Cousart SL, Forrest LM, McCall CE. Induction of RelB participates in endotoxin tolerance. J Immunol. 2006;177:4080–5. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.4080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rothwarf DM, Karin M. The NF-kappa B activation pathway: a paradigm in information transfer from membrane to nucleus. Sci STKE. 1999;1999:RE1. doi: 10.1126/stke.1999.5.re1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medzhitov R, Horng T. Transcriptional control of the inflammatory response. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:692–703. doi: 10.1038/nri2634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen X, El GM, Yoza BK, McCall CE. The NF-kappaB factor RelB and histone H3 lysine methyltransferase G9a directly interact to generate epigenetic silencing in endotoxin tolerance. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:27857–65. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.000950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El-Gazzar M, Yoza BK, Chen X, Garcia BA, Young NL, McCall CE. Chromatin-specific remodeling by HMGB1 and linker histone H1 silences proinflammatory genes during endotoxin tolerance. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:1959–71. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01862-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Gazzar M, Liu T, Yoza BK, McCall CE. Dynamic and selective nucleosome repositioning during endotoxin tolerance. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:1259–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.067330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCall CE, Caves J, Cooper R, DeChatlet L. Functional characteristics of human toxic neutrophils. J Infect Dis. 1971;124:68–75. doi: 10.1093/infdis/124.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mueller LP, Yoza BK, Neuhaus K, Loeser CS, Cousart S, Chang MC, et al. Endotoxin-adapted septic shock leukocytes selectively alter production of sIL-1RA and IL-1beta. Shock. 2001;16:430–7. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200116060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCall CE, Grosso-Wilmoth LM, LaRue K, Guzman RN, Cousart SL. Tolerance to endotoxin-induced expression of the interleukin-1 beta gene in blood neutrophils of humans with the sepsis syndrome. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:853–61. doi: 10.1172/JCI116306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beutler B, Poltorak A. Sepsis and evolution of the innate immune response. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:S2–S6. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryseck RP, Novotny J, Bravo R. Characterization of elements determining the dimerization properties of RelB and p50. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3100–9. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carmody RJ, Ruan Q, Palmer S, Hilliard B, Chen YH. Negative regulation of toll-like receptor signaling by NF-kappaB p50 ubiquitination blockade. Science. 2007;317:675–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1142953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xia Y, Chen S, Wang Y, Mackman N, Ku G, Lo D, et al. RelB modulation of IkappaBalpha stability as a mechanism of transcription suppression of interleukin-1alpha (IL-1alpha), IL-1beta, and tumor necrosis factor alpha in fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7688–96. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.11.7688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen X, Yoza BK, El GM, Hu JY, Cousart SL, McCall CE. RelB sustains IkappaBalpha expression during endotoxin tolerance. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2009;16:104–10. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00320-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bren GD, Solan NJ, Miyoshi H, Pennington KN, Pobst LJ, Paya CV. Transcription of the RelB gene is regulated by NF-kappaB. Oncogene. 2001;20:7722–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoza BK, Hu JY, Cousart SL, McCall CE. Endotoxin inducible transcription is repressed in endotoxin tolerant cells. Shock. 2000;13:236–43. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200003000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trojer P, Reinberg D. Facultative heterochromatin: is there a distinctive molecular signature? Mol Cell. 2007;28:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maison C, Almouzni G. HP1 and the dynamics of heterochromatin maintenance. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:296–304. doi: 10.1038/nrm1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldberg AD, Allis CD, Bernstein E. Epigenetics: a landscape takes shape. Cell. 2007;128:635–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fischle W, Wang Y, Allis CD. Histone and chromatin cross-talk. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:172–83. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ko M, Sohn DH, Chung H, Seong RH. Chromatin remodeling, development and disease. Mutat Res. 2008;647:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]