Abstract

Transport of lactate, pyruvate, and other monocarboxylates across the sarcolemma of skeletal and cardiac myocytes occurs via passive diffusion and by monocarboxylate transporter (MCT) mediated transport. The flux of lactate and protons through the MCT plays an important role in muscle energy metabolism during rest and exercise and in pH regulation during exercise. The MCT isoforms 1 and 4 are the major isoforms of this transporter in skeletal and cardiac muscle. The current consensus on the mechanism of these transporters, based on experimental measurements of labeled lactate fluxes, is that monocarboxylate-proton symport occurs via a rapid-equilibrium ordered mechanism with proton binding followed by monocarboxylate binding. This study tests ordered and random mechanisms by fitting experimental measurements of tracer exchange fluxes from MCT1 and MCT4 isoforms to theoretical predictions derived using relationships between one-way fluxes and thermodynamic forces. Analysis shows that: 1), the available kinetic data are insufficient to distinguish between a rapid-equilibrium ordered and a rapid-equilibrium random-binding model for MCT4; 2), MCT1 has a higher affinity to lactate than does MCT4; 3), the theoretical conditions for the so-called trans-acceleration phenomenon (e.g., increased tracer efflux from a vesicle caused by increased substrate concentration outside the vesicle) do not necessarily require the rate constant for the lactate and proton bound transporter to reorient across the membrane to be higher than that for the unbound transporter; and finally, 4), based on model analysis, additional experiments are proposed to be able to distinguish between ordered and random-binding mechanisms.

Introduction

Lactate is transported across muscle cell plasma membrane mostly by carrier (monocarboxylate transporter) mediated cotransport of lactate and protons, and by a comparatively smaller flux from passive diffusion of lactic acid (1). The kinetics of carrier-mediated transport of lactate across mammalian plasma membranes have been extensively studied experimentally, with the general consensus that the mechanism involves rapid-equilibrium lactate and proton binding, with the proton binding first (ordered-binding), and that the lactate may bind only to the transporter in the proton-bound state, and that only the fully unbound carrier or the fully bound carrier can undergo a conformational change associated with transport of substrates across the membrane (2). Furthermore, it has been determined that the rate of exchange of the fully loaded carrier is faster than that of the unloaded carrier (1,2). These findings are based on experimental measurements of fluxes performed using radio-labeled lactate, in which one-way exchange fluxes are measured. Thus, analysis of these data requires a theoretical analysis of the tracer exchange fluxes associated with putative transport mechanisms. This study develops quantitative descriptions of tracer fluxes to test the proposed kinetic mechanisms against the reported data in the literature for the two main isoforms of monocarboxylate transporter (MCT) (i.e., MCT1 and MCT4) expressed in muscle and the heart.

We used tracer flux data from three previously published studies for our analysis. The first study considered was performed by Juel (3), who reported flux data on lactate and pH dependence of labeled lactate flux across giant sarcolemmal vesicles that demonstrate symmetry in the pH dependence. These sarcolemmal vesicles were prepared from rat gastrocnemius, likely resulting in vesicles that contain both MCT4 and MCT1 with a higher proportion of MCT4 (4–6). In the remaining two studies, rat MCT1 and MCT4 were kinetically characterized by expressing them in Xenopus oocytes (7,8).

In this study, tracer exchange fluxes are derived for the proposed kinetic schemes to show that an ordered mechanism with proton binding first or a random-binding mechanism cannot be excluded based on model fits to these data. Using the full kinetic models, apparent kinetic parameters for specific types of experiments are derived corresponding to both ordered and random-binding mechanisms. Based on our analysis of the expressions for the apparent kinetic parameters, we proposed extensions to the published experimental studies to distinguish between the proposed kinetic mechanisms.

Methods

The following elementary steps constitute a symmetric ordered-binding scheme with protons binding the unbound carrier (E1 or E2) and lactate binding the proton-bound carrier (EH1 or EH2) (Fig. 1):

| (1) |

Here the two sides of the membrane are labeled 1 and 2. As illustrated in Fig. 1 A, enzyme states with binding sites exposed to side 1 are denoted E1, EH1, and EHLAC1. Similarly, enzyme states with binding sites exposed to side 2 are denoted E2, EH2, and EHLAC2. Protons and lactate on side 1 are denoted H1 and LAC1, respectively; protons and lactate on side 2 are denoted H2 and LAC2. The k, kf, and kb values in Eq. 1 are rate constants associated with the individual steps in the mechanism. The assumption of symmetry based on the pH dependence data in Juel's (9) study requires that the forward and reverse rate constants of the carrier exchange are equal for each of the two translocation steps as shown in Eq. 1 (i.e., the forward and reverse rate constants for the translocation of the unbound transporter are both kE; and the forward and reverse rate constants for the translocation of the fully bound transporter are both kEHLAC).

Figure 1.

Kinetic schemes for MCT. (A) Ordered-binding mechanism. (B) Random-binding mechanism.

The total lactate concentration ([LAC]total which includes protonated and unprotonated anionic forms) and lactate anion concentration ([LAC]) on either side of the membrane are related by the following equilibrium relation,

| (2) |

where Ka, LAC is the dissociation constant for lactic acid at 25°C and 0.1 M ionic strength whose negative logarithm to the base 10 (pKa) is reported to be 3.67 (10). Equation 2 with the cited pKa is used to compute the free lactate (C3H5O3−) concentration as a function of total lactate concentration specified in the experimental studies analyzed in this article.

When proton and lactate binding reactions are considered to be in rapid-equilibrium, we define the following equilibrium constants:

| (3) |

From the above scheme, the unidirectional carrier fluxes from side 1 to side 2 are

| (4) |

Juel (3) reports measurement of tracer fluxes rather than net transport. The ratio of exchange of labeled lactate with unlabeled lactate across the membrane may be derived by applying the relationship between one-way fluxes and thermodynamic forces demonstrated by Beard and Qian (11) for reversible processes. The exchange flux ratio of labeled lactate is given by (11,12)

| (5) |

where Keq,cycle = 1, is the equilibrium constant for the entire cycle described in Eq. 1. This value for the equilibrium constant assumes that the ionic conditions and the temperature on both sides of the membrane are equivalent so that the activity coefficient for lactate is the same on both sides.

If an experiment is conducted with labeled lactate on side 1 exchanging with unlabeled lactate on side 2 of the membrane, then flux12 would represent the rate of loss of tracer from side 1 and rate of appearance on side 2 of the membrane. The net flux, which is not equal to the tracer exchange flux, is given by

| (6) |

Given an expression for the net flux, Eqs. 5 and 6 may be used to obtain expression for the one-way exchange fluxes. These expressions are derived in the Appendix, for the ordered quasiequilibrium binding model described above, as well as for the random-order mechanism shown in Fig. 1 B. We excluded an ordered mechanism with lactate binding first, because it could not account for any of the data, before analyzing the catalytic mechanisms shown in Eqs. 1 and 21. We also tested a mechanism where the protonated form of the enzyme could flip across the membrane and found that the parameter estimates for the rate constants were essentially zero, reducing it to the mechanisms shown in Fig. 1.

Inspection of the unidirectional flux and apparent kinetic parameter expressions in the Appendix shows that the identifiable parameters in these models are the binding affinities of protons (KH) and lactate (KLAC) to the MCT (which are assumed to be unaltered by the order of binding), the product of total MCT binding site concentration and the rate constant for the translocation of the fully loaded form of the MCT ([E0]kEHLAC), and the ratio of rate constants for the exchange of free and fully loaded forms of the MCT (kE/kEHLAC). Parameters were estimated using a MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA) implementation of genetic-algorithm-based optimizer PIKAIA 1.2 (13,14) with a generational replacement plan that was then followed by a gradient-based search. Table 1 summarizes the experiments and the corresponding equations used to fit the experimental data with reference to the figures in this article.

Table 1.

Substrate concentrations, figure correspondence to experimental data and equations for data analysis

| Study / experiment | Figure(s) / symbol | Equation(s) for data analysis |

pH1 | [LAC1]total (mM) | pH2 | [LAC2]total (mM) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ordered | Random | ||||||

| Juel (3) / equilibrium exchange | 2, A and B / ● | 14 | 22 | 7.4 | 0–60 | 7.4 | 0–60 |

| Juel (3) / zero trans | 2, A and B / ■ | 14 | 22 | 7.4 | 0–60 | 7.4 | 0 |

| Juel (3) / infinite cis | 2, A and B / ▴ | 14 | 22 | 7.4 | 60 | 7.4 | 0–60 |

| Juel (3) / cis pH effects, influx | 2, C and D / ♦ | 14 | 22 | 5–8 | 10 | 7.4 | 0 |

| Juel (3) / cis pH effects, efflux | 2, C and D / ▴ | 20 | 28 | 7.4 | 0 | 5-8 | 10 |

| Juel (3) / trans pH effects, influx | 2, C and D / ■ | 14 | 22 | 7.4 | 10 | 5–8 | 0 |

| Juel (3) / trans pH effects, efflux | 2, C and D / ● | 20 | 23 | 5-8 | 0 | 7.4 | 10 |

| Dimmer et al. (8) / lactate effects | 4, A and B / ■ | 14 | 28 | 5 | 1–100 | 7.4 | 0 |

| Dimmer et al. (8) / lactate effects | 4, A and B / ● | 14 | 22 | 6 | 1–100 | 7.4 | 0 |

| Dimmer et al. (8)/lactate effects | 4, A and B / ▴ | 14 | 22 | 7 | 1–100 | 7.4 | 0 |

| Dimmer et al. (8) / pH effects | 4, C and D / ■ | 14 | 22 | 5–9 | 1 | 7.4 | 0 |

| Bröer et al. (7) / lactate effects | 5, A and B / ■ | 14, 16 | 22, 24 | 7 | 0.5–50 | 7.3 | 0 |

| Bröer et al. (7) / pH effects | 5, C, and D / ● | 14, 19 | 22, 27 | 5–8 | 1 | 7.3 | 0 |

| Bröer et al. (7) / pH effects | 5, C and D / ■ | 14, 19 | 22, 27 | 5–8 | 5 | 7.3 | 0 |

| Bröer et al. (7) / pH effects | 5, C and D / ▴ | 14, 19 | 22, 27 | 5–8 | 10 | 7.3 | 0 |

| Bröer et al. (7) / pH effects | 5, C and D / ○ | 14, 19 | 22, 27 | 5–8 | 1 | 7.3 | 0 |

Table 1 provides a summary of experimental data analyzed, model equations, and corresponding plots in figures.

Results and Discussion

Lactate transport in sarcolemmal giant vesicles

Juel (3,15,16) characterized pH dependence, lactate dependence, and symmetry of MCT in giant sarcolemmal vesicles prepared from rat skeletal muscle with rapid initial unidirectional tracer flux measurements made on the order of 5 s. Juel (3) characterized tracer influx dependence on external lactate concentrations in equilibrium exchange experiments where intra- and extravesicular lactate concentrations are equal and zero-trans experiments where the intravesicular lactate concentration is zero. In addition, measurements of tracer influx dependence on internal lactate concentrations were made in infinite-cis experiments where the external lactate concentration was fixed at 60 mM while the internal lactate concentration was varied from zero to 60 mM.

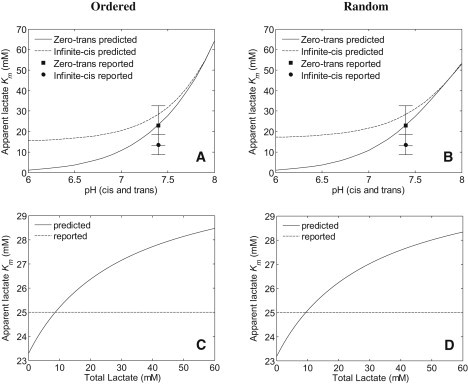

The cis and trans pH dependence of lactate influx and efflux was also characterized in the same study (3) at a constant 10 mM cis lactate concentration, demonstrating symmetry in pH dependence. Lactate and pH dependence data of tracer fluxes were simultaneously fit to flux expressions corresponding to ordered and random substrate binding mechanisms, where the lactate and proton concentrations were treated as constants as specified in Juel's study (3). Fig. 2, A and B, shows the tracer influx data dependent on internal and external lactate concentrations and model fits to flux expressions corresponding to ordered (Fig. 2 A) and random (Fig. 2 B) substrate binding mechanisms. Fig. 2, C and D, shows the data and ordered and random model fits for pH dependence of tracer fluxes, respectively. The estimated parameters, obtained by fitting all flux data simultaneously, are reported in Table 2, which show that both ordered and random substrate binding mechanisms can explain the data equally well. Juel's (3) data seem to show a lactate inhibition of equilibrium exchange and zero-trans fluxes at 60 mM external lactate concentration for equilibrium exchange and zero-trans experiments, which is not captured by our model.

Figure 2.

Lactate and pH effects on tracer fluxes. (A and B) Lactate influx data for equilibrium exchange (●), zero-trans (■), and infinite-cis (▴) experiments from Juel (3) and respective model fits (solid , dashed, and dotted lines) corresponding to the ordered-binding model (A) and the random-binding model (B). (C and D) Lactate influx data from Juel (3) as functions of cis (♦) and trans (■) pH, and lactate efflux data as functions cis (▴) and trans (●) pH and model fits for cis-pH dependence (dashed line) and trans-pH dependence (solid line), corresponding to the ordered-binding model (C) and to the random-binding model (D). Model equations and fixed parameter settings associated with fits are listed in Table 1.

Table 2.

Estimated parameters

| Study / isoform | Parameter | Rapid-equilibrium |

Rapid-equilibrium |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ordered | Random | ||

| Juel (3) / (mixed isoform with MCT4 dominant) | pKH | 8.17 | 8.197 |

| KLAC | 40.1 mM | 46.6 mM | |

| kE/kEHLAC | 2.3 | 2.08 | |

| SSE | 1.359 | 1.3566 | |

| Dimmer et al. (8) / MCT4 | pKH | 7.125 | 7.106 |

| KLAC | 11.89 mM | 29.73 mM | |

| kE/kEHLAC | 0.808 | 0.25 | |

| SSE | 17.12 | 17.28 | |

| Bröer et al. (7) / MCT1 | pKH | 6.282 | 6.664 |

| KLAC | 2.24 mM | 4.63 mM | |

| kE/kEHLAC | 0.157 | 0.205 | |

| SSE | 21.111 | 17.289 |

Table 2 shows parameters pKH (negative logarithm to the base 10 of proton affinity to the monocarboxylate transporter), KLAC (lactate affinity to the monocarboxylate transporter), and kE/kEHLAC (ratio of unbound and fully bound transporter translocation rate constants) estimated from the cited experimental data using flux expressions for ordered and random-binding models, and the sum of squares of errors (SSE) from the curve-fitting process.

However, the data from infinite-cis experiments do not show this inhibition effect. The infinite-cis experiment datum at 60 mM internal lactate, which falls on the model fit to equilibrium exchange data, is equivalent to the equilibrium-exchange datum at 60 mM external lactate. Additionally, the infinite-cis experiment datum at 0 mM internal lactate is equivalent to the equilibrium exchange datum at 60 mM external lactate, which is still below the model prediction (see Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material). Comparison of MCT4 flux data for the zero-trans experiments from the studies of Juel (3), Dimmer et al. (8), and Manning Fox et al. (17) showed that a consistent pattern of flux inhibition at high lactate concentrations is not present (see Fig. S2). Therefore, we did not modify our model to include inhibition at external high lactate concentrations.

The estimated lactate binding affinity is 40.1 mM for the ordered mechanism and 46 mM for the random mechanism and the pK for proton binding is ∼8.2 for both mechanisms, which shows that the net efflux of lactate is governed by the lactate gradient across the sarcolemma at intracellular pH 7. To our knowledge, our reported affinity parameters are the first estimates of intrinsic affinities of lactate and protons for the MCT for the proposed mechanisms, whereas the literature reports apparent Km values (18,19). Also note that the estimated ratio of the rate constant for the translocation of the unbound transporter to the rate constant for the translocation of the fully loaded transporter (proton and lactate bound) is >1, which is contrary to the view in the literature that the unbound transporter has a lower rate constant for translocation than fully bound transporter (1,2). We show below that this relationship between the estimated rate constants is not contrary to trans-acceleration or the phenomenon of a higher tracer flux during equilibrium exchange than in a zero-trans experiment for the same lactate concentration.

Fig. 3, A and B, shows the reported apparent lactate Km values for lactate fluxes during zero-trans and infinite-cis experiments and model-predicted apparent lactate Km values for ordered and random mechanisms, respectively, as functions of pH (expressions for the apparent lactate Km values are given in Eqs. 15, 17, 23, and 25). Model predictions for zero-trans Km values match the reported Km values and the Km values for the increase in infinite cis-flux as a function of internal lactate concentration are higher than the reported Km at pH 7.4 for both binding mechanisms, which is due most likely to an underestimate in the apparent Vmax from a simple Michaelis-Menten fit. Under equilibrium exchange conditions, we show that the apparent Km is a function of lactate concentration (Fig. 3, C and D) as opposed to a single Km reported by Juel (3). The apparent Km (25 ± 6.1 mM) reported by Juel (3) from fitting the equilibrium exchange flux data to the

flux expression falls within our model-predicted ranges.

Figure 3.

Apparent Michaelis constants. (A and B) Reported Km values for zero-trans and infinite-cis experiments at pH 7.4 from Juel (3) and model predictions over a pH range of 6–8 for the ordered-binding mechanism (A) and the random-binding mechanism (B). (C and D) Reported Km values for equilibrium exchange experiments from Juel (3) at pH 7.4 and model predictions over a lactate range of 0–60 mM for the ordered-binding mechanism (C) and the random-binding mechanism (D). Model equations and fixed parameter settings associated with fits are listed in Table 1.

In summary, based on the data of Juel (3), both models fit the data and one may not reject either substrate-binding scheme.

Lactate transport due to MCT4 expressed in Xenopus oocytes

Dimmer et al. (8) characterized lactate and pH dependence of lactate uptake flux in Xenopus oocytes expressing rat MCT4. Dimmer et al. (8) measured radio-isotope-labeled lactate accumulation in oocytes after a 10-min incubation as a function of external lactate ranging from 1 to 100 mM (zero-trans) at three external pH values (pH 5, 6, and 7) and reported the influx rates. The intraoocyte pH is close to 7.4 from the recordings shown in Dimmer et al. (8). Fig. 4 shows lactate influx data and model fits for the ordered-binding mechanism (Fig. 4 A) and the random-binding mechanism (Fig. 4 B). The model fits show qualitative agreement with the data. Dimmer et al. (8) report that the apparent Vmax was similar at pH 6 (4300 ± 200 pmol/10 min) and pH 7 (4200 ± 300 pmol/10 min), and decreased at pH 5 (2200 ± 100 pmol/10 min), which was stated as being in agreement with an ordered-binding mechanism. However, the expressions for the apparent lactate Vmax show that for the ordered mechanism it is independent of the external pH, and that it decreases with increasing external pH for the random mechanism (Eqs. A9 and A17).

Figure 4.

Lactate and pH effects on MCT4 fluxes in Xenopus oocytes. (A and B) Lactate influx data from Dimmer et al. (8) as a function of external lactate concentration at pH 5 (■), pH 6 (▴), and pH 7 (●) and respective model fits (solid , dashed, and dotted lines), corresponding to the ordered-binding model (A) and the random-binding model (B). (C and D) Lactate influx dependence data (■) as a function of external pH at 1 mM external lactate concentration and model fits (solid lines) corresponding to the ordered-binding model (C) and to the random-binding model (D). Model equations and fixed parameter settings associated with fits are listed in Table 1.

Fig. 4, C and D, shows the pH dependence of lactate influx at 1 mM external lactate concentration and model fits for the ordered mechanism and the random mechanism, respectively. The fitted model predicts that the flux peaks around pH 5.35 and thereafter decreases monotonically toward pH 1 or toward pH 10. Only a single measurement made at pH 5 qualitatively agrees with the model fit. More flux measurements under pH 6 could test the model in the lower pH range.

The estimated parameters (Table 2) show a higher affinity 12–30 mM of lactate toward the transporter and a lower pK of 7.1 for proton binding to the transporter when compared to the estimates from Juel's (3) data. The residual sum of squares of error (SSE) and estimated parameters show that neither model may be excluded, although the model fits are poorer when compared to the fits to Juel's (3) data. A possible explanation for the comparatively poorer fits may be a potential breakdown of the assumption that the reported fluxes are unidirectional initial fluxes. The lactate and proton concentrations inside the oocyte could change significantly during the 10-min incubation with tracer-labeled external lactate.

Lack of reported data on actual lactate time course in the oocytes under 10 min precludes further speculation.

Lactate transport due to MCT1expressed in Xenopus oocytes

Bröer et al. (7) kinetically characterized rat MCT1 expressed in Xenopus oocytes by measuring radio-isotope-labeled lactate uptake or pH changes in the oocytes due to lactate-proton cotransport. The data presented in Bröer et al. (7) are lactate fluxes normalized to their apparent maximal velocities, which results in the nonidentifiability of the product of total MCT binding site concentration and the rate constant for the translocation of the fully loaded form of the MCT. Fig. 5, A and B, shows lactate uptake flux data as a function of external lactate concentration at pH 7 from the study of Bröer et al. (7) and our model fits to the data using the ordered-binding mechanism (Fig. 5 A) and the random-binding mechanism (Fig. 5 B).

Figure 5.

Lactate and pH effects on MCT1 fluxes in Xenopus oocytes. (A and B) Normalized lactate influx data (■) measured using initial rates of cytosolic pH changes from Bröer et al. (7) as a function of external lactate at external pH 7, and model fits using the ordered-binding model (A) and the random-binding model (B). (C and D) Normalized lactate influx data as a function of external pH using radio-isotope-labeled lactate at external lactate concentrations 1 mM (●), 5 mM (■), and 10 mM (▴), and influx data using initial rates of cytosolic pH change at 1 mM external lactate (○). Model fits using the ordered-binding model (C) and fits using the random-binding model (D). Model equations and fixed parameter settings associated with fits are listed in Table 1.

Both ordered and random mechanisms fit the lactate dependence of influx well. Fig. 5, C and D, shows normalized lactate influx data measured from radio-isotope-labeled lactate uptake as a function of external pH at three different external lactate concentrations (1 mM, 5 mM, and 10 mM) and zero internal lactate. At 1 mM external lactate concentration, Bröer et al. (7) also measured the lactate influx using initial rates of cytosolic pH changes, which are very close to the influx data from tracer uptake at 1 mM external lactate. Model fits using the random-binding mechanism shown in Fig. 5 D are better when compared to the fits using the ordered-binding mechanism shown in Fig. 5 C. The parameter estimates for both models in Table 2 show that the lactate affinity for MCT1 is higher than that for MCT4 and the pK for proton binding is lower by >0.5 pH.

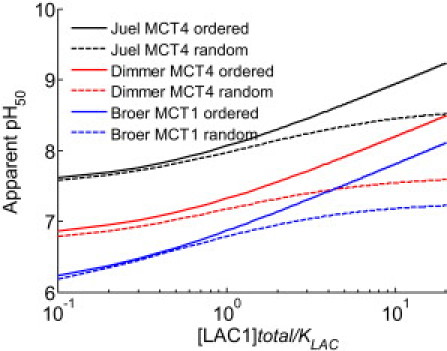

The pH dependence curves of lactate influx show increasing apparent pH50 (the pH at which half-maximal influx is attained) with increasing external lactate concentration. Model predictions of the apparent pH50 shown in Fig. 6, A and B, qualitatively agrees with Bröer et al.'s (7) nonmechanistic empirical equation for the pH50. The predicted difference between ordered and random model pH50 values is ∼1.5 pH units at high (∼100 mM) external lactate concentrations, which is clearly distinguishable based on experimental measurements. Therefore, to distinguish between ordered and random-binding mechanisms, the study of Bröer et al. (7) may be extended to include measurements of pH dependence of lactate influx at a zero internal lactate concentration over a range of lactate concentrations higher than in the original study.

Figure 6.

Reported and model-predicted apparent pH50 for MCT1 fluxes in Xenopus oocytes. (A and B) pH50 values corresponding to the data shown in Fig. 5, C and D, reported by Bröer et al. (7) and model predictions of pH50 values for ordered (solid lines) and random (dashed lines) binding models, using the parameter estimates based on the ordered-binding model (A) and using the parameter estimates based on the random-binding model (B). The reported pH50 values correspond to lactate influx flux data obtained using radio-isotope-labeled lactate at external lactate concentrations 1 mM (●), 5 mM (■), and 10 mM (▴) and influx data using initial rates of cytosolic pH change at 1 mM external lactate (○).

Model predictions of apparent Km values of net lactate efflux and influx under resting physiological conditions

The values for apparent lactate Km values in the studies analyzed in this article were determined under specific experimental lactate and pH conditions. Based on the kinetic parameters estimated for MCT1 and MCT4 (Table 2), we predicted the apparent Km values of net lactate efflux and influx under resting physiological pH and lactate concentrations in human skeletal muscle (Table 3). The resting intracellular pH was taken to be 7 and the intracellular lactate 1.3 mM (20), with extracellular pH assumed to be equal to the plasma pH 7.4 and the extracellular lactate 5.7 mM (20). The predicted apparent Km values are very similar for both Juel's (3) and Dimmer et al.'s (8) MCT4 studies between ordered and random model fits. The predicted lactate efflux Km from Juel's MCT4 parameter set and Dimmer's MCT4 parameter set are close to each other. The predicted Km for MCT1 for the random-binding model is 4.89 mM. The predicted apparent Km values show that MCT4 is indeed a lower apparent affinity transporter under resting physiological conditions when compared to MCT1.

Table 3.

Predicted apparent Km values under resting physiological conditions

| Study / isoform | Parameter | Rapid-equilibrium |

Rapid-equilibrium |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ordered (mM) | Random (mM) | ||

| Juel (3) / (mixed isoform with MCT4 dominant) | Efflux Km | 23.6 | 23.5 |

| Influx Km | 24.5 | 24.4 | |

| Dimmer et al. (8) / MCT4 | Efflux Km | 23.83 | 19.76 |

| Influx Km | 24.15 | 20.14 | |

| Bröer et al. (7) / MCT1 | Efflux Km | 8.73 | 4.89 |

| Influx Km | 10.47 | 4.89 |

Table 3 shows the model predicted apparent Km values under resting physiological conditions for net lactate efflux and influx under resting physiological conditions, i.e., intracellular pH 7, intracellular lactate 1.3 mM, extracellular pH 7.4, and extracellular lactate 5.7 mM using parameters estimates shown in Table 2.

A sufficient condition for trans-acceleration

A key observation in the published experimental kinetic studies on the MCT is the so-called trans-acceleration effect where the unidirectional tracer flux is greater when there is more lactate on the trans-side as opposed to a zero lactate concentration. We derive a sufficient condition for trans-acceleration by determining an inequality for the condition that the unidirectional tracer flux in an equilibrium exchange experiment is greater than the unidirectional tracer flux in a zero-trans experiment for the same pH and lactate concentrations:

| (7) |

Equation 7 shows that the rate constant for translocation of the fully loaded carrier need not always be greater than the rate constant for translocation of the unloaded carrier, for this phenomenon to occur.

Design of experiments to distinguish between ordered and random-binding mechanisms

Analysis of Juel's (3), Dimmer et al.'s (8), and Bröer et al.'s (7) data in the preceding sections showed that their data are insufficient to reject either ordered or random model for substrate binding. Herein we present an approach for experiment design based on the predicted behavior of the apparent kinetic parameters, and manipulation of only the external proton and lactate concentrations. Equations A22–A29 show the apparent Michaelis constants and maximal velocities of unidirectional tracer-labeled lactate influx with respect to external lactate and proton concentrations when the internal lactate concentration is set to zero (zero-trans experiment), which simplifies both the expressions and the experimental conditions. In this section, we denote side 1 as the extracellular or extravesicular side and the side 2 as the intracellular or intravesicular side.

Equations A22–A25 show the apparent zero-trans Km values and Vmax values with respect to external lactate concentrations, which are functions of the external lactate concentration and the internal proton and lactate concentrations. As the external pH approaches extremely alkaline values with respect to KH, the unidirectional tracer flux itself approaches zero (see cis-pH effects in Fig. 2, C and D), and when the pH approaches extremely acidic values with respect to KH, both ordered and random mechanisms yield the same apparent Vmax and Km. Therefore, characterizing lactate influx as a function of external lactate at various external proton concentrations will not help to distinguish between ordered and random-binding schemes.

Equations A26–A29 show the zero-trans apparent Km values and Vmax values with respect to external proton concentrations, which are functions of external lactate concentration and internal lactate and proton concentrations. As the external lactate concentration approaches values much higher than KLAC, the [H1] Km approaches zero (or pH50 goes toward infinity) for the ordered mechanism and

for the random mechanism. Under these conditions, the apparent Vmax value approaches the same limit

for both mechanisms. Fig. 7 shows predictions of pH50 values for ordered and random-binding mechanisms as a function of [LAC1]total/KLAC, based on parameters that were estimated using the ordered mechanism based flux expression from all three studies listed in Table 2. The internal pH values are fixed at 7.4 for Juel's (3) study, 7.4 for Dimmer et al.'s (8) MCT4 study, and 7.3 for Bröer et al.'s (7) MCT1 study. A random mechanism results in a saturating relationship whereas an ordered mechanism results in a nonsaturating increase in the pH50. Therefore, the pH50 predictions show that in going from an external lactate concentration of KLAC to a concentration of 10 KLAC, the change in pH50 is much larger for the ordered mechanism than for the random mechanism. We illustrate this phenomenon in Fig. S1 in terms of right shifts in flux versus pH curves at external lactate concentrations of KLAC, 10 KLAC, and 100 KLAC. Fig. S3 shows that the saturating behavior of the half-maximal pH predicted for the random mechanism is clearly distinguishable from the nonsaturating behavior of the half-maximal pH predicted for the ordered mechanism.

Figure 7.

Model predictions of pH50 for zero-trans experiments using ordered (solid lines) and random (dashed lines) binding mechanisms as a function of external [LAC]total/KLAC, computed using parameters estimated from all three studies analyzed in this article.

The results for the shift in pH50 values were similar when we used parameters that were estimated using a random-binding-mechanism-based flux expression from all three studies listed in Table 2. Therefore, an experiment conducted to characterize the pH dependency of lactate influx at high external lactate concentrations, in addition to the experiments conducted by Bröer et al. (7) at lower lactate concentrations, can potentially reject one of the proposed substrate binding schemes, i.e., ordered with protons binding first or random.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Ranjan Dash and the anonymous reviewers for helpful comments.

Research was funded by National Institutes of Health grant No. R01 HL094317 (to D.A.B.).

Appendix

Flux and Apparent Kinetic Parameter Expressions for Ordered-Binding Mechanism

The ordered-binding mechanism with proton binding first shown in Eq. 1 and in Fig. 1 A may be solved for quasi-steady state of [EHLAC1], [EHLAC2], [E1], and [E2] to derive the unidirectional tracer fluxes defined in Eq. 4. In addition, lactate- and proton-bound forms of E1 and E2 may be described in terms of substrate binding equilibria following the rapid-equilibrium binding assumption,

| (A1) |

where

Similarly,

| (A2) |

where

The conservation of total enzyme mass [E0] may be expressed as

| (A3) |

Quasi-steady state of [EHLAC1], [EHLAC2], [E1], and [E2] results in the following equation:

| (A4) |

Based on our assumption of symmetry, we denote the forward and reverse rate constants for the translocation of EHLAC and E as kEHLAC and kE, respectively.

Using Eqs. 8–10 in Eq. 11 and solving for [E1], we obtain

| (A5) |

Substituting for P1 and P2 from Eq. 8 in Eq. 8 in Eq. 12, we obtain

| (A6) |

Therefore, the unidirectional flux from side 1 to side 2, , is given by

| (A7) |

Apparent [LAC1] Km of flux12 is given by

| (A8) |

Apparent [LAC1] Vmax of flux12 is given by

| (A9) |

Apparent [LAC2] Km of flux12 is given by

| (A10) |

Apparent [H1] Km of flux12 is given by

| (A11) |

Apparent [H1] Vmax of flux12 is given by

| (A12) |

The unidirectional flux from side 2 to side 1 is given by

| (A13) |

Flux and apparent kinetic parameter expressions for random-binding mechanism

The elementary steps in a rapid-equilibrium random mechanism for MCT shown in Fig. 1 B are

| (A14) |

For this mechanism, the unidirectional forward flux expression, derived in a manner similar to the ordered-binding mechanism shown in the preceding section, is

| (A15) |

Apparent [LAC1] Km of flux12 is given by

| (A16) |

Apparent [LAC1] Vmax of flux12 is given by

| (A17) |

Apparent [LAC2] Km of flux12 is given by

| (A18) |

Apparent [H1] Km of flux12 is given by

| (A19) |

Apparent [H1] Vmax of flux12 is given by

| (A20) |

The unidirectional flux from side 2 to side 1 is given by

| (A21) |

Apparent kinetic parameters for ordered and random mechanisms when [LAC2] = 0

Expressions for apparent [LAC1] Km values when [LAC2] is zero

Ordered mechanism:

| (A22) |

Random mechanism:

| (A23) |

Expressions for apparent [LAC1] Vmax values when [LAC2] is zero

Ordered mechanism:

| (A24) |

Random mechanism:

| (A25) |

Expressions for apparent [H1] Km values when [LAC2] is zero

Ordered mechanism:

| (A26) |

Random mechanism:

| (A27) |

Expressions for apparent [H1] Vmax values when [LAC2] is zero

Ordered mechanism:

| (A28) |

Random mechanism:

| (A29) |

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Juel C. Lactate-proton cotransport in skeletal muscle. Physiol. Rev. 1997;77:321–358. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poole R.C., Halestrap A.P. Transport of lactate and other monocarboxylates across mammalian plasma membranes. Am. J. Physiol. 1993;264:C761–C782. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.4.C761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Juel C. Symmetry and pH dependency of the lactate/proton carrier in skeletal muscle studied with rat sarcolemmal giant vesicles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1996;1283:106–110. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(96)00084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson M.C., Jackson V.N., Halestrap A.P. Lactic acid efflux from white skeletal muscle is catalyzed by the monocarboxylate transporter isoform MCT3. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:15920–15926. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.26.15920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonen A., Miskovic D., Halestrap A.P. Abundance and subcellular distribution of MCT1 and MCT4 in heart and fast-twitch skeletal muscles. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000;278:E1067–E1077. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.278.6.E1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonen A. The expression of lactate transporters (MCT1 and MCT4) in heart and muscle. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001;86:6–11. doi: 10.1007/s004210100516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bröer S., Schneider H.P., Deitmer J.W. Characterization of the monocarboxylate transporter 1 expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes by changes in cytosolic pH. Biochem. J. 1998;333:167–174. doi: 10.1042/bj3330167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dimmer K.S., Friedrich B., Bröer S. The low-affinity monocarboxylate transporter MCT4 is adapted to the export of lactate in highly glycolytic cells. Biochem. J. 2000;350:219–227. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Juel C. Lactate/proton co-transport in skeletal muscle: regulation and importance for pH homeostasis. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1996;156:369–374. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.1996.206000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martell A.E., Smith R.M., Motekaitis R.J. National Institute of Standards and Technology; Gaithersburg, MD: 2004. NIST Standard Reference Database 46 V. 8.0. NIST Critically Selected Stability Constants of Metal Complexes. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beard D.A., Qian H. Relationship between thermodynamic driving force and one-way fluxes in reversible processes. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e144. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiechert W., de Graaf A.A. Bidirectional reaction steps in metabolic networks: I. Modeling and simulation of carbon isotope labeling experiments. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1997;55:101–117. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19970705)55:1<101::AID-BIT12>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charbonneau P. National Center for Atmospheric Research; Boulder, CO: 2002. Release Notes for PIKAIA 1.2. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charbonneau P. National Center for Atmospheric Research; Boulder, CO: 2002. An Introduction to Genetic Algorithms for Numerical Optimization. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Juel C. Muscle lactate transport studied in sarcolemmal giant vesicles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1991;1065:15–20. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(91)90004-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juel C. Regulation of cellular pH in skeletal muscle fiber types, studied with sarcolemmal giant vesicles obtained from rat muscles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1995;1265:127–132. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(94)00209-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manning Fox J.E., Meredith D., Halestrap A.P. Characterization of human monocarboxylate transporter 4 substantiates its role in lactic acid efflux from skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 2000;529:285–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00285.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halestrap A.P., Price N.T. The proton-linked monocarboxylate transporter (MCT) family: structure, function and regulation. Biochem. J. 1999;343:281–299. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Juel C., Halestrap A.P. Lactate transport in skeletal muscle - role and regulation of the monocarboxylate transporter. J. Physiol. 1999;517:633–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0633s.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sjøgaard G., Saltin B. Extra- and intracellular water spaces in muscles of man at rest and with dynamic exercise. Am. J. Physiol. 1982;243:R271–R280. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1982.243.3.R271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.