Abstract

Plant communities vary dramatically in the number and relative abundance of species that exhibit facilitative interactions, which contributes substantially to variation in community structure and dynamics. Predicting species’ responses to neighbors based on readily measurable functional traits would provide important insight into the factors that structure plant communities. We measured a suite of functional traits on seedlings of 20 species and mature plants of 54 species of shrubs from three arid biogeographic regions. We hypothesized that species with different regeneration niches—those that require nurse plants for establishment (beneficiaries) versus those that do not (colonizers)—are functionally different. Indeed, seedlings of beneficiary species had lower relative growth rates, larger seeds and final biomass, allocated biomass toward roots and height at a cost to leaf mass fraction, and constructed costly, dense leaf and root tissues relative to colonizers. Likewise at maturity, beneficiaries had larger overall size and denser leaves coupled with greater water use efficiency than colonizers. In contrast to current hypotheses that suggest beneficiaries are less “stress-tolerant” than colonizers, beneficiaries exhibited conservative functional strategies suited to persistently dry, low light conditions beneath canopies, whereas colonizers exhibited opportunistic strategies that may be advantageous in fluctuating, open microenvironments. In addition, the signature of the regeneration niche at maturity indicates that facilitation expands the range of functional diversity within plant communities at all ontogenetic stages. This study demonstrates the utility of specific functional traits for predicting species’ regeneration niches in hot deserts, and provides a framework for studying facilitation in other severe environments.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00442-010-1741-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Chihuahuan, Facilitation, Functional traits, Mojave, Sonoran

Introduction

Facilitation has been shown to play an important role in the assembly and dynamics of many plant communities (Callaway et al. 2002; Valiente-Banuet et al. 2006; Cavieres and Badano 2009; Butterfield et al. 2010) particularly those of low-productivity environments (Bertness and Callaway 1994; Callaway 1995). In plant communities where facilitation is common, species’ responses to neighbors can still vary from strongly positive (here termed “beneficiaries”) to strongly negative (“colonizers”) (McAuliffe 1988; Liancourt et al. 2005), with the number, relative abundance, and specialization of species with respect to facilitation having important consequences for community stability and dynamics (McAuliffe 1988; Verdu and Valiente-Banuet 2008; Butterfield 2009). While the proximate causes of facilitation have been studied extensively—for example, improved water relations, reduced herbivory, temperature buffering, etc. (Flores and Jurado 2003; Callaway 2007)—the intrinsic biological characteristics of species that determine whether or not they engage in facilitative interactions are just beginning to be explored (Valiente-Banuet et al. 2006; Lopez and Valdivia 2007). Thus, an improved ability to predict the outcome of interactions based on species’ traits would be an important step forward in our understanding of the community and ecosystem-level consequences of facilitation.

In many severe environments, the presence of a neighbor is generally considered to produce a more benign microenvironment than open, bare ground, thereby permitting less stress-tolerant species to persist within a community (Michalet et al. 2006; but see Maestre et al. 2009). Despite this apparently simple contrast, many factors may differ in complex ways in the presence versus absence of a neighbor. This is particularly true in arid ecosystems, in which local environmental differences in soil moisture (Tielbörger and Kadmon 2000), light (Valiente-Banuet and Ezcurra 1991), soil fertility (Turner et al. 1966), herbivory (McAuliffe 1986) and temperature extremes (Nobel 1980) between sub-canopy and open microsites may simultaneously drive facilitation. Terms such as “benign” and “stressful” may not accurately represent this complex variation, particularly since many species perform better outside the influence of established canopies (McAuliffe 1988; Verdu and Valiente-Banuet 2008), which has been attributed to shade intolerance and belowground competition from larger neighbors (Holmgren et al. 1997; Miriti et al. 1998). Clearly, many environmental variables differ between open and sub-canopy microsites, and act in concert to determine plant growth and survival.

Understanding biological responses to complex environments can benefit from a trait-based approach (McGill et al. 2006). Measuring functional traits related to life-history strategies, resource economies and disturbance responses in contrasting environments provides a broad perspective on the selection pressures acting on plant populations (Westoby 1998; Westoby et al. 2002; Wright et al. 2004), all of which may be relevant to facilitation (Valiente-Banuet et al. 2006). The nature of trait relationships with facilitation may also vary through ontogeny (Valiente-Banuet and Verdu 2008), as seedling and mature trait values are often uncorrelated (Grime et al. 1997; Cornelissen et al. 2003). Seedling traits should be particularly important in desert perennial plant communities, since facilitation is most relevant during the regenerative phase of the perennial life-cycle (Yeaton 1978; McAuliffe 1988; Miriti 2006). However, ontogenetic trait conservatism may also result in the regeneration niche (in this case, sub-canopy or open microsite) influencing mature functional strategies (Valiente-Banuet et al. 2006; Poorter 2007). This is an important consideration, in that the functional traits of mature plants are much more likely to drive ecosystem processes than are those of seedlings, given their much larger cumulative biomass (Grime 1998). In addition, mature plant traits may determine if a species functions as a nurse plant at maturity, thereby influencing community structure both in terms of responses to and effects on microenvironmental conditions (Butterfield 2009). Thus, these broader consequences of regeneration niche selection should be assessed by measuring mature functional traits directly.

A broad array of both seedling and mature functional traits may exhibit strong relationships with one another and with the regeneration niche across desert plant species. Seed mass is a particularly important trait in this context, due to possible relationships with dispersal and reproductive strategies as well as seedling energy reserves (Moles and Westoby 2006). Following germination, maximum relative growth rate (RGRmax) indicates a plant’s ability to acquire resources during brief windows of opportunity, which may come at a cost to survival under persistently stressful conditions (Arendt 1997). Biomass allocation to different tissues reveals tradeoffs in the acquisition of different resources, which may differ greatly in sub-canopy and open microsites. Root-to-shoot ratio represents the relative limitation of water or mineral nutrients versus light or carbon, whereas height and leaf mass fraction (LMF) are associated with light and carbon acquisition, respectively (Poorter and Nagel 2000). In addition to allocation, tissue quality is also important, indicating tradeoffs between resource turnover and efficiency. Specific root length (SRL) is positively correlated with root elongation and maximum uptake rates in saturated soils, but negatively correlated with root longevity and drought tolerance (Nicotra et al. 2002; Markesteijn and Poorter 2009). Conversely, leaf mass per area (LMA) is negatively correlated with maximum photosynthetic rates and stomatal conductance, while being positively associated with leaf lifespan (Wright et al. 2004). LMA may also be positively correlated with the cell wall content and rigidity of leaves, which may partially regulate wilting point (Niinemets 2001). In addition to LMA, photosynthetic rates are also related to leaf size (i.e., leaf dry mass; MD) and several aspects of leaf composition (Niklas et al. 2007), including leaf dry matter content (LDMC), percent nitrogen (%N) and surface area (SA). These organ-specific traits related to water and carbon economies scale up to influence whole-plant water use efficiency (WUE), which is positively associated with average longevity of individuals in desert perennial plant populations (Schuster et al. 1992). Individual longevity is also positively associated with the total size or biomass of desert plants, which are negatively correlated with frequency of establishment and positively correlated with proportion of older plants in a population (Goldberg and Turner 1986). While the links between some of these life-history, allocation, construction and composition traits have been explored independently, their cumulative description of functional differentiation would provide a more comprehensive picture of functional strategies and an opportunity to quantitatively assess the functional basis of the regeneration niche in desert plants.

In this study, we measured the broad suite of functional traits discussed above on a variety of colonizer and beneficiary species across three different hot desert biogeographic regions of the southwestern USA. Both seedlings and mature plants were studied in order to determine potential effects of the regeneration niche on multiple ontogenetic stages. With these data, we tested the hypotheses that (1) functional traits are highly inter-correlated across species (due to strong spatial autocorrelation in environmental factors between open and sub-canopy microsites), (2) beneficiary and colonizer species have different functional strategies (i.e., occupy different volumes of trait space), with the contrast being greatest during the seedling stage, and (3) seedling and mature functional strategies (i.e., multivariate trait axes) will be correlated due to ontogenetic conservatism, even if individual traits are poorly correlated through ontogeny.

Materials and methods

Seedling experimental design

Twenty species of woody perennials native to the Chihuahuan, Sonoran, and Mojave Deserts of the southwestern USA were selected for estimation of seedling traits (see Electronic supplementary material, ESM 1). Field-collected seeds were obtained from the Sonoran Desert National Monument and the University of Arizona Desert Laboratory, with seeds collected from at least three plants per species. Seed of species that could not be obtained in the field were supplied by the Desert Legume Program of the University of Arizona and the Rancho Santa Anna Botanical Garden. Twelve angiosperm families were represented, with four species each from both Fabaceae and Asteraceae due to their high species richness and dominance in arid ecosystems of North America. Potential size and longevity range from sub-shrubs that live up to 50–100 years to large shrubs and small trees that live for hundreds or thousands of years. Seeds were germinated in Petri dishes on wet filter paper, and within one day of root emergence ten seedlings of each species were transplanted into plastic tree containers 7.5 cm wide × 20 cm deep filled with autoclaved, coarse grit sand. Plants were grown in a controlled environment with 12-h days and 35/25°C temperature cycles, similar to late spring or early autumn field temperatures. Total average photon flux was 190 μmol s−1 m−2, which while substantially below natural levels of irradiance is comparable to other growth chamber studies of semi-arid woody perennials (Wright and Westoby 1999), and creates a consistent set of conditions that permit reasonable comparisons across species. Plants were top-watered with drip irrigation twice daily, and fertilized every third day with major and minor nutrients. All plants were destructively harvested 6 weeks after transplanting before any roots came in contact with the containers, resulting in an average of 6 ± 2SD replicates per species. An additional growth chamber was also used to estimate seedling survival during a simulated drought. Seeds were germinated, transplanted and watered in the same manner as above for the first 4 weeks, at which time all watering was terminated. Plants were then monitored frequently until clear signs of mortality (leaves became dry or brown, photosynthetic stems turned brown) were observed, then the number of days until mortality was recorded as an estimate of short-term drought survival. Average number of replicates per species for the survival study was 8 ± 2SD.

All seedlings that were not subjected to the survival experiment were harvested for trait measurements (Table 1). All leaves were weighed fresh immediately following harvest and subsequently scanned on an HP Scanjet G4010 flatbed scanner. Stems were then cut level with the sand surface, and all roots carefully removed from the container, washed to remove sand particles and scanned in the same manner as the leaves. All plant biomass was subsequently dried at 60°C for at least 48 h before being weighed. The scanned images were analyzed with ImageJ v. 1.41 (NIH 2007) to estimate total leaf area for each plant, as well as total root length. Average seed mass was also estimated for at least 50 seeds per species.

Table 1.

Functional traits measured in this study

| Trait | Abbreviation | Units | Ecological relevance | Stage measured | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seed mass | Seed | g | Energy reserves; radical size; life-history | Seedling | |||

| Total biomass | Mass | g | Energy reserves; competitive ability | Seedling | |||

| Root mass fraction | RMF | g g−1 | Light versus water/nutrient acquisition | Seedling | |||

| Leaf mass fraction | LMF | g g−1 | Light versus water/nutrient acquisition | Seedling | |||

| Height | Height | cm | Light versus water/nutrient acquisition | Seedling | |||

| Relative growth rate | RGR | t−1 | Competitive ability; responsiveness to water pulse | Seedling | |||

| Leaf dry mass | Md | g | Leaf function; carbon investment on carbon return | Seedling/mature | |||

| Leaf surface area | SA | cm2 | Photosynthetic capacity; leaf temperature | Seedling/mature | |||

| Leaf mass per area | LMA | g cm−2 | Water retention; gas exchange | Seedling/mature | |||

| Leaf dry matter content | LDMC | % | Photosynthetic capacity; palatability | Seedling/mature | |||

| Specific root length | SRL | cm g−1 | Embolism resistance; responsiveness to water pulse | Seedling | |||

| Short term drought survival | Survival | days | Likelihood of individual establishment | Seedling | |||

| Leaf nitrogen content | %N | % | Photosynthetic capacity; palatability | Mature | |||

| Water use efficiency | WUE | δ13C | Balance between carbon and water economies | Mature | |||

| Mature growth form | Size | Ordinal | Storage capacity; life-history strategy | Mature | |||

Functional traits were measured for each plant and averaged to produce a species-level estimate. Total biomass, LMF and RMF were estimated with dry biomass. RGRmax was calculated by dividing final biomass by seed mass then taking the natural logarithm, and height of the primary stem was measured as the Euclidean distance from the sand surface to the highest apical meristem. Leaf scans were used to estimate SA (cm2) and LMA (g cm−2), and Md (g) was divided by fresh mass to estimate LDMC (%). Analogous to the inverse of LMA, SRL was calculated as the length of all roots divided by total root dry mass (cm g−1).

Mature trait data collection

Sampling was conducted in early March, late March, and mid-April in the Sonoran, Mojave, and Chihuahuan Deserts, respectively. In order to collect leaves at a similar developmental stage across these regions that differ somewhat in elevation and phenology, all samples were collected in the spring following full development of new leaves. All samples were collected between 700 and 1,000 m elevation in shrub-dominated plant communities, with some cacti and few perennial grasses present. Annual precipitation ranges from 220 mm at the Mojave site (Mojave National Preserve, CA, USA) to 300 mm at the Chihuahuan site (Indio Ranch Research Station, TX, USA), with the Sonoran sites in between (Sonoran Desert National Monument, Superstition Mountains and Tumamoc Hill, AZ, USA). Sampling sites were selected to include the full range of upland habitat types within each region (see ESM 2 for site descriptions and study species).

A total of 54 species from 16 families were sampled, the most common families being Asteraceae (18 species), Fabaceae (9) and Lamiaceae (5). Species were assigned to one of four size classes based on their USDA designations: suffrutescent, sub-shrub, shrub or tree. The majority of species were sub-shrubs (22) or shrubs (19), with some small trees (9) and several suffrutescent species (4). The relative proportions of families and growth forms sampled are representative of the woody floras of these arid ecosystems, and care was taken to randomly sample the available species in order to avoid biasing the estimates of relationships among traits. Aside from the large proportion of trees in the Fabaceae (6 of 9 species), no single family is over-represented within a single growth form, making growth form and family relatively independent. Many of the study species have very broad distributions, covering two or all three of the regions studied. However, samples were collected at only one site for each species, such that comparisons across “regions” or higher taxonomic groups with this dataset do not accurately represent the full trait distributions within such subsets and should be interpreted with caution.

In addition to measuring LMA, LDMC, Md and SA in the same manner as for seedlings, elemental analysis was conducted to measure %N and stable carbon isotope ratios (δ13C, ‰) of mature leaves. Seedling leaves were not subjected to this analysis due to insufficient biomass for some species. Stable carbon isotope composition is a correlate of WUE, due to the relationship between 13C discrimination and rates of stomatal water vapor conductance. Less negative δ13C values indicate lower conductance such that δ13C is positively correlated with WUE in C3 plants (Farquhar et al. 1989), which includes all species in the present study. Elemental analyses were conducted at the Stable Isotope Mass Spectrometry Laboratory at Kansas State University. All δ13C samples had a SD ± 0.03 relative to the standard.

Trait relationships

Several methods were used to assess relationships between traits. First, all functional traits were transformed to ordinal variables prior to correlation and principal components analyses, a preferred practice when assessing functional strategies (Grime et al. 1997). Variance estimates of the raw, continuous trait variables varied dramatically, which could introduce several forms of bias into statistical analyses if used rather than species’ ranks. In addition, for the seedling data, while growth chambers minimize unexplained variance that could be caused by environmental variation, the estimated value of a given trait almost certainly varies between seedlings grown indoors versus in the field. However, species’ ranks within a trait are less likely to vary with growing conditions than are estimated continuous values, making the results of rank-based analyses more relevant to ecological patterns in the field.

After transforming the trait variables, Spearman rank correlations were calculated between all traits within and among ontogenetic stages. Principal components analysis (PCA) was then performed on the seedling and mature datasets separately in order to determine the nature and number of relevant axes of functional differentiation among species at both ontogenetic stages. Scree tests were used first to select the number of principal components to be retained for both datasets. Following removal of principal components that did not explain sufficient variation in the data, varimax rotations were performed in order to maximize the variance explained by the remaining principal components (Johnson and Wichern 2002). The frequency of significant correlations among traits within an ontogenetic stage was high (see “Results”), so PCA served to simplify the correlation structure among traits as well as reduce the potential effects of multicollinearity on interpretation of further statistical analyses.

Regeneration niche

Based upon an extensive literature survey, species were assigned to one of two regeneration niche categories. This was done to test for relationships between seedling traits and observed patterns of seedling survival in the field. It should first be noted that a binary designation of a species as a colonizer or beneficiary does not reflect the continuum of responses observed in the field, but was considered sufficient in the absence of a continuous metric of regeneration niche. The selection criteria for published studies were either (1) differences in observed seedling survival beneath a canopy versus in the open, (2) population-level differences in the abundance of individuals beneath canopies versus in the open, or (3) successional data. In the absence of spatially explicit patterns, early and late successional species were classified as colonizers and beneficiaries, respectively. These microsite successional processes are generally a function of facilitation in arid environments (McAuliffe 1988). If information was not available for a species, the closest relative with regeneration niche information was used instead (designations and references available in the ESM).

Following the assessment of trait interrelationships, logistic regressions were performed on the principal component scores in order to test the hypothesis that species’ functional strategies predict their regeneration niche. The binomial response variable was the regeneration niche (colonizer = 0, beneficiary = 1), and each of the principal components at the seedling and mature stages were the predictor variables. When data were not available for the same species at maturity, a congener for which data were available was substituted. No substitute for Atriplex was available at maturity, as only C3 plants were studied for consistency of WUE estimates. Regeneration niche data were available for 16 of the seedling species and 15 of the mature species. All statistical analyses were performed with the R statistical package (v.2.9.1).

Results

Functional strategies

Among seedling leaf traits, more than half (35/66) of the possible bivariate correlations were significant, indicating substantial coordination among many aspects of plant function. At the leaf scale, SA and Md were strongly positively correlated, as were LMA and LDMC (Table 2). However, the former were not correlated with the latter, indicating that interior leaf construction may be somewhat independent of leaf size in seedlings. All four of these leaf traits were negatively correlated with SRL, indicating strong parallels between leaf and root function. At the organismal scale, RMF and LMF were negatively correlated, with allocation to roots rather than leaves being positively correlated with seed mass and LMA, but negatively correlated with RGRmax. LMF was also negatively correlated with LDMC and positively correlated with SRL. Total biomass was not correlated with allocation or RGRmax, but was positively correlated with height, seed mass, survival, and leaf size. Seed mass was generally highly correlated with most traits, with the sole exception of SA. Survival was also positively correlated with seed and total mass, indicating that larger plants tended to survive drought longer.

Table 2.

Spearman rank correlation coefficients for seedling traits

| Trait | RGR | Height | Seed | Survival | LDMC | SA | Md | LMA | RMF | LMF | Mass |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height | 0.08 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Seed | −0.72*** | 0.46* | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Survival | −0.20 | 0.41 | 0.54* | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| LDMC | −0.30 | 0.21 | 0.67** | 0.39 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| SA | 0.44 | 0.60** | 0.10 | 0.48* | 0.30 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Md | −0.11 | 0.55* | 0.50* | 0.51* | 0.32 | 0.55* | – | – | – | – | – |

| LMA | −0.70*** | 0.08 | 0.69** | 0.40 | 0.56* | −0.24 | 0.00 | – | – | – | – |

| RMF | −0.65** | −0.24 | 0.45* | 0.19 | 0.25 | −0.30 | 0.03 | 0.47* | – | – | – |

| LMF | 0.79*** | −0.02 | −0.72*** | −0.27 | −0.51* | 0.29 | 0.08 | −0.90*** | −0.67** | – | – |

| Mass | 0.06 | 0.86*** | 0.57* | 0.61** | 0.44 | 0.73*** | 0.71*** | 0.16 | −0.03 | −0.10 | – |

| SRL | 0.50* | −0.54* | −0.86*** | −0.49* | −0.66** | −0.27 | −0.57** | −0.62** | −0.40 | 0.58** | −0.70*** |

For explanation of abbreviations, see Table 1

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

Two principal components were retained from the seedling data matrix (PCS1 and PCS2), explaining 38 and 36% of the variance, respectively (Table 3). PCS1 had moderate to very high loadings for all traits except SA, reflecting a continuum of functional strategies related to nearly all aspects of seedling form and function. Species with more positive scores on PCS1 tended to be larger (high seed mass and total biomass), had low RGRmax and poor short-term drought survival; allocated biomass to roots (high RMF) at the expense of leaves (low LMF), but tended to be taller and allocated more mass to each individual leaf (high Md); had denser leaves and roots (high LMA and LDMC, low SRL). The patterns of trait loadings on PCS1 are identical to the Spearman correlations with seed mass (Table 2), suggesting that the latter may be a particularly important trait in determining functional strategies. In general, the trait loadings reflect a clear spectrum of turnover and efficiency, ranging from opportunistic to conservative strategies with increasing scores on PCS1. PCS2 reflected additional variation among a subset of the seedling traits. Species with more positive PCS2 values had greater total biomass, leaf mass and height (the same pattern as PCS1), but allocated biomass to leaves at the expense of roots, had low LMA, high SA leaves and high RGRmax. Seed mass, LDMC, survival and SRL were not related to PCS2. As a whole, positive PCS2 values appear to indicate greater overall size and allocation to photosynthesis than expected based on constraints of seed size.

Table 3.

Principal components analysis results for seedling traits

| Trait | PCS1 | PCS2 |

|---|---|---|

| Seed | 0.94 | <0.01 |

| SRL | −0.92 | <0.01 |

| LDMC | 0.72 | <0.01 |

| Survival | 0.67 | <0.01 |

| Mass | 0.69 | 0.67 |

| Md | 0.56 | 0.56 |

| Height | 0.52 | 0.66 |

| LMA | 0.73 | −0.51 |

| LMF | −0.71 | 0.63 |

| RGR | −0.61 | 0.66 |

| RMF | 0.47 | −0.59 |

| SA | <0.01 | 0.85 |

| σ explained | 0.38 | 0.36 |

For explanation of abbreviations, see Table 1

As with seedlings, substantial multicollinearity was found among mature plant traits (Table 4). Leaf %N, Md and SA were all positively correlated, while being negatively correlated with LDMC. Similar to seedling leaves, LMA was positively correlated with LDMC and uncorrelated with Md. However, LMA was negatively correlated with SA, indicating that leaves with less surface area tended to be denser or thicker. The only trait significantly correlated with WUE was size (positively), which was also positively correlated with Md and LMA.

Table 4.

Spearman rank correlation coefficients for mature traits

| Trait | Size | SA | Md | LMA | LDMC | %N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA | −0.05 | |||||

| Md | 0.27* | 0.47*** | ||||

| LMA | 0.31* | −0.62*** | 0.23 | |||

| LDMC | 0.03 | −0.49*** | −0.19 | 0.32* | ||

| %N | 0.10 | 0.42** | 0.37** | -0.17 | −0.57*** | |

| WUE | 0.27* | 0.09 | 0.24 | 0.03 | 0.23 | 0.03 |

For explanation of abbreviations, see Table 1

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

Three principal components were retained from the mature data matrix, explaining 32, 23 and 20% of the variance (Table 5). The first mature principal component (PCM1) had strong positive loadings for %N, Md and SA, and a negative loading for LDMC, with LMA being the only leaf trait independent of PCM1. As such, PCM1 can be interpreted as variation from low to high potential photosynthetic capacity. LMA and plant size had strong positive loadings on PCM2, although SA had a moderate (negative) loading on PCM2 as well. %N, LDMC and WUE were independent of PCM2. The only variable with a strong (positive) loading on PCM3 was WUE, although size and Md had moderate positive loadings as well. Both PCM2 and PCM3 reflect independent axes of low to high conservatism based on different aspects of plant function. On average across the regions sampled, the Chihuahuan species had the lowest values for PCM1 (photosynthetic capacity) and the Sonoran species the highest. The Chihuahuan species were the highest on PCM2 and PCM3 (LMA and WUE, respectively), with the Mojave species lowest on PCM2 and similar to the Sonoran species on PCM3. These differences may reflect climatological and phylogenetic differences, but may not be accurate representations of this variation and should be interpreted cautiously.

Table 5.

Principal components analysis results for mature traits

| Trait | PCM1 | PCM2 | PCM3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| %N | 0.82 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| LDMC | −0.80 | <0.01 | 0.31 |

| Md | 0.62 | 0.33 | 0.44 |

| SA | 0.68 | −0.54 | 0.31 |

| LMA | <0.01 | 0.92 | <0.01 |

| Size | <0.01 | 0.60 | 0.40 |

| WUE | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.90 |

| σ explained | 0.32 | 0.23 | 0.20 |

For explanation of abbreviations, see Table 1

Regeneration niche

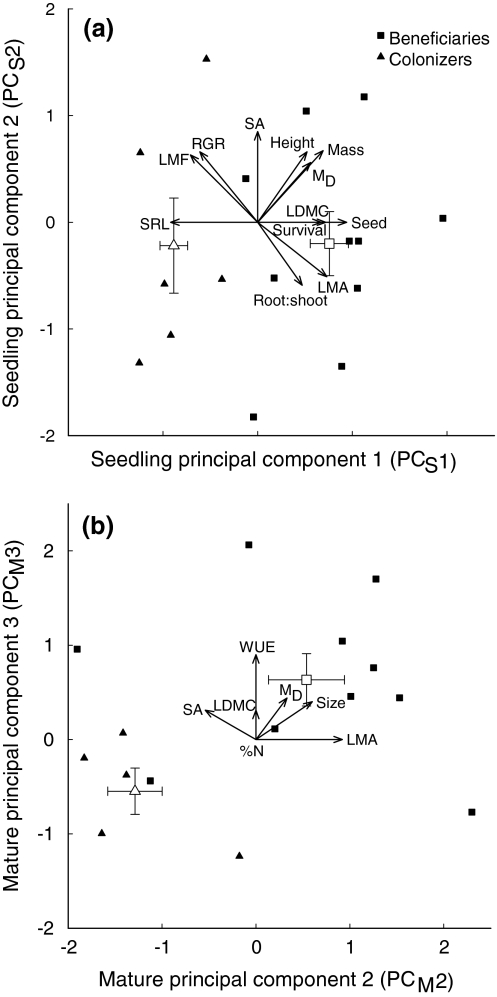

Among seedlings, there was no overlap between colonizer and beneficiary groups along PCS1 (Fig. 1a), resulting in a significant relationship with the regeneration niche based on a logistic regression (Z = ∞, P < 0.001). Beneficiaries and colonizers had more positive and more negative values of PCS1, respectively (i.e., positive relationship between PCS1 score and facilitation-dependence). There was no significant relationship between PCS2 and the regeneration niche (Z = 0.04, P = 0.97), indicating that PCS1 is related to differences between colonizers and beneficiaries, while PCS2 reflects variation within these two groups.

Fig. 1.

Trait loadings (vectors) and species scores for colonizers and beneficiaries (triangles and squares, respectively) along principal components axes for traits of a seedlings and b mature plants. Mean scores ± 1SE for each regeneration niche group are indicated by large, open symbols

For mature plants, PCM1 was not related to the regeneration niche (Z = 0.51, P = 0.61), but PCM2 and PCM3 had significant (Z = 1.99, P = 0.047) and moderately significant (Z = 1.88, P = 0.060) positive relationships with facilitation-dependence (Fig. 1b). Consequently, PCM2 and PCM3 were both significantly correlated with PCS1, which was the the seedling axis of differentiation related to the regeneration niche (r = 0.55 and 0.58, respectively; P < 0.05). All other possible relationships between seedling and mature principal components were not significant. Only 6% of all possible correlations between seedling and mature traits were significant, none of which represented the same trait at both stages (ESM 3), demonstrating that, while multivariate axes of differentiation were related through ontogeny, individual traits developed somewhat independently across species. The regeneration niche was highly conserved within the two dominant families, with all Asteraceae and Fabaceae being colonizers and beneficiaries, respectively. Thus these two families had strongly contrasting scores along PCS1, PCM2, and PCM3

Discussion

Functional strategies of beneficiaries and colonizers were significantly different, both for seedlings and mature plants. Taken together, the patterns of trait loadings on both seedling and mature principal components suggest that woody desert plants are strongly differentiated in their responses to environmental predictability, and can be arrayed along an axis from opportunistic to conservative strategies. These patterns reflect a tradeoff between resource turnover and efficiency that may be generally universal for vascular plants (Wright et al. 2004), and sheds an important light on the microenvironmental factors and corresponding functional strategies that shape plant life in severe environments.

Several lines of evidence from the seedling data suggest that sub-canopy microsites represent relatively consistent, resource-limiting environments in contrast to open microsites that fluctuate between highly severe and resource-rich states. The high density tissues of beneficiary leaves (high LMA and LDMC) and roots (low SRL), as well as their large leaf dry mass suggest a slow rate of return on long-lived organs suited to persistent water and/or light limitation (Valladares and Niinemets 2008; Markesteijn and Poorter 2009). Similarly, the allocation of resources to root mass and height (high RMF and height) at the expense of leaves (low LMF) indicates that substantial initial investments are required to acquire sufficient water and light beneath canopies. An alternative but complementary explanation is that colonizers construct cheap tissues (low LMA, high SRL) to maximize photosynthesis and water uptake during brief soil moisture pulses. Greater height does not increase light interception in the open, nor does allocation to roots in briefly saturated soil improve water relations, thereby justifying the high LMF, short stature and low RMF of colonizers. Arguments from both perspectives suggest that the slow-turnover, high efficiency beneficiary strategies and high-turnover, low-efficiency colonizer strategies are beneficial in their respective microenvironments.

Trait patterns related to resource turnover and efficiency may be largely explained by variation in seed size, RGRmax and short-term drought survival. The comparatively larger seeds of beneficiaries could be related to differences in energy reserve requirements, dispersal patterns and vectors, and maternal investment (Pianka 1970). Greater seed reserves are advantageous in many low-light environments (Westoby et al. 1996), and larger seeds are often associated with deeper tap-roots, leading to greater long-term water access (Guerrero-Campo and Fitter 2001). In contrast, production of many small seeds may increase the odds of at least some colonizers becoming established in sufficiently wet conditions (Wright and Westoby 1999; Moles et al. 2004). High RGRmax is critical under these circumstances, permitting seedlings to acquire sufficient carbon before going dormant (a phenological characteristic common to all of the colonizer species in this study) during subsequent inter-pulse periods. The patterns of RGRmax and seed size provide functional support for the assertion that effective soil moisture pulses are more frequent but of smaller size and duration in open microsites, whereas soil moisture is more persistent (but often limiting) beneath canopies at an intra-annual scale (Huxman et al. 2004).

When viewed as a whole, the above trait relationships suggest that colonizers and beneficiaries may not only be well-suited to their observed regeneration niche, but also maladapted to the other. Light-demanding colonizer species may not be able maintain a positive carbon balance in the low-light environment beneath shrub canopies, although the semi-substitutable nature of light and water can result in a shift toward facilitation in wet years (Butterfield et al. 2010). In contrast, beneficiaries may be excluded from the open for two primary reasons. First, many beneficiaries require protection from herbivory (McAuliffe 1984, 1986), likely due to the high costs incurred by losing large, expensive leaves that cannot be quickly replaced. In a similar vein, while beneficiaries had greater short-term drought survival, this is most likely linked to seed reserves. Once these reserves are exhausted, the dense tissues and belowground allocation of resources exhibited by beneficiaries may result in negligible photosynthesis during extended dry periods in the field, coupled with the inability to fix sufficient carbon during brief wet periods in the open. Thus, short-term drought survival on a per-individual basis may not be directly relatable to establishment at the population level.

Colonizers and beneficiaries maintained their general strategies of opportunism and conservatism through ontogeny. The only mature axis not correlated with the regeneration niche was PCM1, with high scores indicating high %N, SA, Md and low LDMC, all of which are associated with high potential photosynthetic rates. The term “potential” refers to the role of water availability in determining how often, how long, and to what extent maximum photosynthetic rates are approached (Reynolds et al. 1999; Housman et al. 2006). Traits associated with PCM2 likely indirectly regulate photosynthetic rate by determining leaf water potential. Species that were beneficiaries tended to have high scores on PCM2 indicating high LMA and large plant size, with the loadings of SA and Md likely related to selection on LMA. Larger desert plants tend to have deeper root systems (Schenk and Jackson 2002), permitting more persistent use of deep soil moisture. High LMA may support this persistent water uptake via a more negative wilting point while simultaneously minimizing diffusive water loss (Poorter et al. 2009). However, high LMA may come at a cost to maximum photosynthetic rate through reduced internal CO2 diffusion (Niinemets 1999). Smaller, more shallow-rooted species generally experience more pulsed soil moisture conditions (Schwinning and Ehleringer 2001), making cheap, leaky, low-LMA leaves viable during wet periods. Contrasting selection pressures on water conservation and carbon acquisition may explain why WUE is relatively independent of the other traits measured: a similar WUE may be attained by either minimizing water loss or maximizing carbon gain, with larger, higher LMA beneficiary species employing the former strategy and smaller, lower LMA colonizer species the latter. Beneficiaries did, however, maintain significantly greater WUE than colonizers, suggesting some coordination between WUE and unmeasured physiological or functional traits. Interestingly, the range of functional strategies employed by beneficiaries at maturity were more diverse than those of colonizers, suggesting that ontogenetic drift or altered selection pressures influence development despite correlations between the seedling and mature principal components related to the regeneration niche. Functional convergence through ontogeny might be expected for colonizers, with initial differences among seedlings of different species being reduced by strong selection for a common growth form in open microsites. In contrast, some beneficiaries experience a strong ontogenetic niche shift upon emerging above their nurse’s canopy whereas others remain perpetually beneath the canopy. This could lead to ontogenetic functional divergence among beneficiary species. Colonizer convergence and/or beneficiary divergence are hinted at by our results (Fig. 1a, b). Alternatively, the greater age at reproductive maturity and longer lifespan of beneficiaries may lead to greater ontogenetic drift in the absence of any strong selection differences (Coleman et al. 1994). In general, ontogenetic shifts and phenotypic plasticity are two areas of future research that may provide important insights into the form and function of desert woody plants, as well as the causes and consequences of facilitation.

The results of this study draw strong parallels to many existing theories regarding plant functional strategies, but with varying degrees of congruity. Traditionally, desert perennials have been classified as stress-avoiders or stress-tolerators (Noy-Meir 1973). This classification scheme unfortunately does not define “stress” well, particularly given the differences in the nature of resource and environmental fluctuations in open versus sub-canopy microsites. Similarly, “stress” is highly dependent upon a species’ functional strategy as is clear from the inability of many colonizers to establish beneath canopies despite conditions being highly favorable for beneficiaries. Perhaps most notably, r–K selection (MacArthur and Wilson 1967) bears a resemblance to the functional strategies and microsite successional dynamics of colonizers and beneficiaries (as does the similar R–S axis of CSR theory (Grime 1977)). While the functional analogy is accurate, the community dynamics generated by these strategies in deserts differ from the successional paradigm in which r–K selection theory was developed. Establishment of colonizers in deserts is dependent upon temporal windows of opportunity during wet periods (Butterfield et al. 2010), with the availability of resources that make establishment possible regulated by exogenous supply rates (precipitation), rather than resources being freed up by removal of K-selected species (Goldberg and Novoplansky 1997). Second, replacement of colonizers by beneficiaries via facilitation is not a function of differences in intrinsic growth rates and competitive exclusion, as with r- and K-selection dynamics (Pianka 1970), but by alteration of the local environment (see Connell and Slatyer 1977 for definitions of successional mechanisms). Third, a self-replicating beneficiary vegetation state does not exist in deserts, likely due to direct and indirect negative effects of mature plants on conspecific establishment (McAuliffe 1990; Miriti 2006). This results in individual microsites cycling through semi-independent dynamics of colonization, replacement, and abandonment (McAuliffe 1988). While r–K selection theory clearly does not address the intricacies of desert plant communities, these comparative differences between arid and more mesic ecosystems provide important insights into shifts in the structure and dynamics of plant communities across broad gradients in precipitation and productivity.

The functional causes and consequences of facilitation are just beginning to be studied, and should be critically compared to existing theories that do not explicitly consider positive interactions. Similarly, no single framework for studying the functional ecology of facilitation is likely to be sufficient. Facilitation occurs in many different biomes and ecosystems, with likely variation in the qualitative differences between open and sub-canopy microsites, as well as the traits that are most relevant to plant fitness in these contrasting microenvironments. Clearly more research is needed to determine the relationships between facilitation and functional strategies, however general concepts such as tradeoffs between resource turnover and efficiency should be used to make meaningful comparisons across biomes and taxa.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Bureau of Land Management, Mojave National Preserve, University of California, University of Arizona and University of Texas for permitting collection of leaf samples. J. Propster, T. Shaw and K. Simmons assisted with sample analysis. M. Holmgren, A. Kinzig, D. Peters and several anonymous reviewers provided comments that greatly improved this manuscript. J. McAuliffe and R. Callaway engaged in helpful discussions that shaped many ideas in this paper. B.J.B. was supported by the Jerome Aronson Plant Biology Fellowship at Arizona State University and the Forrest Shreve Desert Ecology Fellowship of the Ecological Society of America. The experiments presented in this study were conducted in compliance with the laws of the United States.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Arendt JD. Adaptive intrinsic growth rates: an integration across taxa. Q Rev Biol. 1997;72:149–177. doi: 10.1086/419764. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bertness MD, Callaway R. Positive interactions in communities. Trends Ecol Evol. 1994;9:191–193. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(94)90088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield BJ. Effects of facilitation on community stability and dynamics: synthesis and future directions. J Ecol. 2009;97:1192–1201. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2009.01569.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield BJ, Betancourt JL, Turner RM, Briggs JM. Facilitation drives 65 years of vegetation change in the Sonoran Desert. Ecology. 2010;91:1132–1139. doi: 10.1890/09-0145.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaway RM. Positive interactions among plants. Bot Rev. 1995;61:306–349. doi: 10.1007/BF02912621. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Callaway RM. Positive interactions and interdependence in plant communities. Dordrecht: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Callaway RM, et al. Positive interactions among alpine plants increase with stress. Nature. 2002;417:844–848. doi: 10.1038/nature00812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavieres LA, Badano EI. Do facilitative interactions increase species richness at the entire community level? J Ecol. 2009;97:1181–1191. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2009.01579.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JS, McConnaughay KDM, Ackerly DD. Interpreting phenotypic variation in plants. Trends Ecol Evol. 1994;9:187–191. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(94)90087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell JH, Slatyer RO. Mechanisms of succession in natural communities and their role in community stability and organization. Am Nat. 1977;111:1119–1144. doi: 10.1086/283241. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelissen JHC, et al. Functional traits of woody plants: correspondence of species rankings between field adults and laboratory-grown seedlings? J Veg Sci. 2003;14:311–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1654-1103.2003.tb02157.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Ehleringer JR, Hubick KT. Carbon isotope discrimination and photosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1989;40:503–537. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.40.060189.002443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flores J, Jurado E. Are nurse-protege interactions more common among plants from arid environments? J Veg Sci. 2003;14:911–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1654-1103.2003.tb02225.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg D, Novoplansky A. On the relative importance of competition in unproductive environments. J Ecol. 1997;85:409–418. doi: 10.2307/2960565. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg DE, Turner RM. Vegetation change and plant demography in permanent plots in the Sonoran Desert. Ecology. 1986;67:695–712. doi: 10.2307/1937693. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grime JP. Evidence for existence of 3 primary strategies in plants and its relevance to ecological and evolutionary theory. Am Nat. 1977;111:1169–1194. doi: 10.1086/283244. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grime JP. Benefits of plant diversity to ecosystems: immediate, filter and founder effects. J Ecol. 1998;86:902–910. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2745.1998.00306.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grime JP, et al. Integrated screening validates primary axes of specialisation in plants. Oikos. 1997;79:259–281. doi: 10.2307/3546011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero-Campo J, Fitter AH. Relationships between root characteristics and seed size in two contrasting floras. Acta Oecol. 2001;22:77–85. doi: 10.1016/S1146-609X(00)01101-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren M, Scheffer M, Huston MA. The interplay of facilitation and competition in plant communities. Ecology. 1997;78:1966–1975. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(1997)078[1966:TIOFAC]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Housman DC, et al. Increases in desert shrub productivity under elevated carbon dioxide vary with water availability. Ecosystems. 2006;9:374–385. doi: 10.1007/s10021-005-0124-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huxman TE, et al. Precipitation pulses and carbon fluxes in semiarid and arid ecosystems. Oecologia. 2004;141:254–268. doi: 10.1007/s00442-004-1682-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RA, Wichern DW. Applied multivariate statistical analysis. Upper Saddle River, USA: Prentice Hall; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Liancourt P, Callaway RM, Michalet R. Stress tolerance and competitive-response ability determine the outcome of biotic interactions. Ecology. 2005;86:1611–1618. doi: 10.1890/04-1398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez RP, Valdivia S. The importance of shrub cover for four cactus species differing in growth form in an Andean semi-desert. J Veg Sci. 2007;18:263–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1654-1103.2007.tb02537.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur RH, Wilson EO. The theory of island biogeography. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Maestre FT, Callaway RM, Valladares F, Lortie CJ. Refining the stress-gradient hypothesis for competition and facilitation in plant communities. J Ecol. 2009;97:199–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2008.01476.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Markesteijn L, Poorter L. Seedling root morphology and biomass allocation of 62 tropical tree species in relation to drought- and shade-tolerance. J Ecol. 2009;97:311–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2008.01466.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McAuliffe JR. Prey refugia and the distributions of 2 Sonoran Desert cacti. Oecologia. 1984;65:82–85. doi: 10.1007/BF00384466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAuliffe JR. Herbivore-limited establishment of a Sonoran Desert tree, Cercidium microphyllum. Ecology. 1986;67:276–280. doi: 10.2307/1938533. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McAuliffe JR. Markovian dynamics of simple and complex desert plant communities. Am Nat. 1988;131:459–490. doi: 10.1086/284802. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McAuliffe JR. Paloverdes, pocket mice and bruchid beetles—interrelationships of seeds, dispersers, and seed predators. Southwest Nat. 1990;35:329–337. doi: 10.2307/3671949. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGill BJ, Enquist BJ, Weiher E, Westoby M. Rebuilding community ecology from functional traits. Trends Ecol Evol. 2006;21:178–185. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalet R, et al. Do biotic interactions shape both sides of the humped-back model of species richness in plant communities? Ecol Lett. 2006;9:767–773. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miriti MN. Ontogenetic shift from facilitation to competition in a desert shrub. J Ecol. 2006;94:973–979. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2006.01138.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miriti MN, Howe HE, Wright SJ. Spatial patterns of mortality in a Colorado desert plant community. Plant Ecol. 1998;136:41–51. doi: 10.1023/A:1009711311970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moles AT, Westoby M. Seed size and plant strategy across the whole life cycle. Oikos. 2006;113:91–105. doi: 10.1111/j.0030-1299.2006.14194.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moles AT, Falster DS, Leishman MR, Westoby M. Small-seeded species produce more seeds per square metre of canopy per year, but not per individual per lifetime. J Ecol. 2004;92:384–396. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-0477.2004.00880.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nicotra AB, Babicka N, Westoby M. Seedling root anatomy and morphology: an examination of ecological differentiation with rainfall using phylogenetically independent contrasts. Oecologia. 2002;130:136–145. doi: 10.1007/s004420100788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIH (2007) ImageJ v. 1.41, Bethesda, MD, USA. http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/

- Niinemets Ü. Components of leaf dry mass per area-thickness and density alter leaf photosynthetic capacity in reverse directions in woody plants. New Phytol. 1999;144:35–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.1999.00466.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niinemets Ü. Global-scale climatic controls of leaf dry mass per area, density, and thickness in trees and shrubs. Ecology. 2001;82:453–469. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2001)082[0453:GSCCOL]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niklas KJ, et al. “Diminishing returns” in the scaling of functional leaf traits across and within species groups. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:8891–8896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701135104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobel PS. Morphology, nurse plants, and minimum apical temperatures for young Carnegiea gigantea. Bot Gaz. 1980;141:188–191. doi: 10.1086/337142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noy-Meir I. Desert ecosystems: environment and producers. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1973;4:25–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.04.110173.000325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pianka ER. On r- and K-selection. Am Nat. 1970;104:592–597. doi: 10.1086/282697. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poorter L. Are species adapted to their regeneration niche, adult niche, or both? Am Nat. 2007;169:433–442. doi: 10.1086/512045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poorter H, Nagel O. The role of biomass allocation in the growth response of plants to different levels of light, CO2, nutrients and water: a quantitative review. Aust J Plant Physiol. 2000;27:1191. doi: 10.1071/PP99173_CO. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poorter H, et al. Causes and consequences of variation in leaf mass per area (LMA): a meta-analysis. New Phyt. 2009;182:565–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds JF, et al. Impact of drought on desert shrubs: Effects of seasonality and degree of resource island development. Ecol Monogr. 1999;69:69–106. doi: 10.1890/0012-9615(1999)069[0069:IODODS]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk HJ, Jackson RB. Rooting depths, lateral root spreads and below-ground/above-ground allometries of plants in water-limited ecosystems. J Ecol. 2002;90:480–494. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2745.2002.00682.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster WSF, Sandquist DR, Phillips SL, Ehleringer JR. Comparisons of carbon isotope discrimination in populations of aridland plant species differing in lifespan. Oecologia. 1992;91:332–337. doi: 10.1007/BF00317620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwinning S, Ehleringer JR. Water use trade-offs and optimal adaptations to pulse-driven arid ecosystems. J Ecol. 2001;89:464–480. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2745.2001.00576.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tielbörger K, Kadmon R. Temporal environmental variation tips the balance between facilitation and interference in desert plants. Ecology. 2000;81:1544–1553. [Google Scholar]

- Turner RM, Alcorn SM, Olin G, Booth JA. Influence of shade, soil and water on saguaro seedling establishment. Bot Gaz. 1966;127:95–102. doi: 10.1086/336348. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valiente-Banuet A, Ezcurra E. Shade as a cause of the association between the cactus Neobuxbaumia tetetzo and the nurse plant Mimosa luisana in the Tehuacan Valley, Mexico. J Ecol. 1991;79:961–971. doi: 10.2307/2261091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valiente-Banuet A, Verdu M. Temporal shifts from facilitation to competition occur between closely related taxa. J Ecol. 2008;96:489–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2008.01357.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valiente-Banuet A, Rumebe AV, Verdu M, Callaway RM. Modern quaternary plant lineages promote diversity through facilitation of ancient tertiary lineages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:16812–16817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604933103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valladares F, Niinemets Ü. Shade tolerance, a key plant feature of complex nature and consequences. Annu Rev Ecol Evol S. 2008;39:237–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.39.110707.173506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verdu M, Valiente-Banuet A. The nested assembly of plant facilitation networks prevents species extinctions. Am Nat. 2008;172:751–760. doi: 10.1086/593003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westoby M. A leaf-height-seed (LHS) plant ecology strategy scheme. Plant Soil. 1998;199:213–227. doi: 10.1023/A:1004327224729. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Westoby M, Leishman M, Lord J. Comparative ecology of seed size and dispersal. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B. 1996;351:1309–1317. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1996.0114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Westoby M, et al. Plant ecological strategies: some leading dimensions of variation between species. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 2002;33:125–159. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.33.010802.150452. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wright IJ, Westoby M. Differences in seedling growth behaviour among species: trait correlations across species, and trait shifts along nutrient compared to rainfall gradients. J Ecol. 1999;87:85–97. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2745.1999.00330.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wright IJ, et al. The worldwide leaf economics spectrum. Nature. 2004;428:821–827. doi: 10.1038/nature02403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeaton RI. A cyclical relationship between Larrea tridentata and Opuntia leptocaulis in the northern Chihuahuan Desert. J Ecol. 1978;66:651–656. doi: 10.2307/2259156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.