Abstract

Purpose

We investigated the clinicopathologic information of patients with gastric cancer with multiple primary cancers (GC-MPC) of three or more sites.

Materials and Methods

Between 1995 and 2009, 105,908 patients were diagnosed with malignancy at Severance Hospital, Yonsei University Health System. Of these, 113 (0.1%) patients with MPC of three or more sites were registered, and 41 (36.3%) of these were GC-MPC. We retrospectively reviewed the clinical data and overall survival using the medical records of these 41 GC-MPC patients. We defined synchronous cancers as those occurring within 6 months of the first primary cancer, while metachronous cancers were defined as those occurring more than 6 months later.

Results

Patients with metachronous GC-MPC were more likely to be female (p=0.003) and young than patients with synchronous GC-MPC (p=0.013). The most common cancer sites for metachronous GC-MPC patients were the colorectum, thyroid, lung, kidney and breast, while those for synchronous GC-MPC were the head and neck, esophagus, lung, and kidney. Metachronous GC-MPC demonstrated significantly better overall survival than synchronous GC-MPC, with median overall survival durations of 4.7 and 14.8 years, respectively, and 10-year overall survival rates of 48.2% and 80.7%, respectively (p<0.001).

Conclusion

Multiplicity of primary malignancies itself does not seem to indicate a poor prognosis. The early detection of additional primary malignancies will enable proper management with curative intent.

Keywords: Neoplasms, Multiple primary, Stomach neoplasms

Introduction

Since 2002, a population-based mass-screening program for gastric cancer was started by the Ministry of Health and Welfare in Korea, resulting in increasing numbers of patients with early gastric cancer. With the increased detection of early gastric cancer and the improvement of surgical procedure during the past three decades (1-3), gastric cancer survival has improved. Long-term follow-up for recurrence has led to an increased incidence of second primary cancers (4,5).

Multiple primary cancers (MPC) in one patient has been a frequent finding in recent decades. Although the mechanism for the pathogenesis of MPC has yet to be clarified, some factors such as heredity, constitution, environment, immunology, carcinogens including viruses, radiotherapy, and chemical treatments have been implicated. Increasingly elderly patient populations and improved diagnostic techniques have also been indicated as possible causes (6). Among patients with MPC, triple cancers are known to occur in 0.5%, and quadruple or quintuple cancers in less than 0.1% of the population (7). In Western Europe and the U.S., a number of cohort studies have examined the risk of a second neoplasm after the diagnosis of a specific tumor (8-10). However, there are few reports of MPC for gastric cancer. This is because gastric cancer is less frequent in Western Europe and the U.S. than it is in East Asia. In addition, multiple primary cancers of three or more sites are extremely rare conditions in patients with gastric cancer. Therefore, there is little data which reports the incidence and clinical features of this rare disease entity.

Therefore, we performed this study to evaluate the incidence of gastric cancer patients with three or more primary cancers. In addition, we also investigated clinicopathologic information of metachronous and synchronous gastric cancer patients in order to improve patient management and follow-up.

Materials and Methods

1. Patients

Between January 1995 and December 2009, 105,908 patients were diagnosed with malignancy at Severance Hospital, Yonsei University Health System. Among these, 113 (0.1%) patients with MPC of three or more sites were registered, and 41 (36.3%) of these had synchronous or metachronous gastric cancer. Diagnosis of gastric cancer and other MPC were pathologically confirmed in all patients.

2. Methods

We retrospectively reviewed clinicopathologic features of these 41 patients with metachronous or synchronous gastric cancer in MPC of three or more sites. The following data was collected; gender, age at initial cancer diagnosis, stage, gastric cancer histology, and survival from the time of first diagnosis of cancer. The tumor stage of the gastric cancer was determined according to Tumor-Node-Metastasis (TNM) classification (American Joint Committee on Cancer, 6th edition). Two main categories were used for histological typing: differentiated type (including papillary adenocarcinoma and well and moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma) and undifferentiated type (including poorly differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma, mucinous adenocarcinoma, and signet ring cell adenocarcinoma).

The MPC was defined according to Warren and Gates's criteria (11). The definition of MPC was as follows: 1) the tumor had to have definite features of malignancy, 2) the tumor had to be separate and distinct from the index tumor, which was gastric adenocarcinoma in this study, 3) the possibility of the tumor being a metastasis of the index tumor had to be ruled out. Based on this definition, we selected a total of 113 patients with three or more primary cancers between 1995 and 2009. Then, we selected 41 patients who were diagnosed with primary gastric cancer, synchronously or metachronously.

In terms of the chronicity, we defined synchronous and metachronous cancer based on Moertel's definition. Synchronous cancers were defined as those occurring within 6 months of the first primary cancer, while metachronous cancers were defined as those occurring more than 6 months later (12). Overall survival was defined as the time from first primary cancer diagnosis to death (of any cause).

3. Statistics

For statistical analysis, we used the χ2-test and Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and the student's t-test for continuous variables. The survival curve was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and the statistical difference in prognosis was analyzed using a log rank test. SPSS ver. 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used throughout and p-values of <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

1. Clinicopathologic features of synchronous and metachronous MPC

A total of 41 gastric cancer patients were diagnosed with three or more primary sites (GC-MPC). Among these, 34 (82.9%) had triple, 6 (14.6%) had quadruple and 1 (2.4%) had quintuple primary malignancies. Seventeen patients (41.5%) were diagnosed with MPC synchronously, whereas 24 (58.5%) were diagnosed metachronously.

Among 17 patients with synchronous GC-MPC, 6 patients were diagnosed with other malignancies before gastric cancer. In addition, 8 of 17 patients had 1 simultaneous malignancy in addition to gastric cancer, and 8 other patients had 2. Furthermore, one patient was diagnosed simultaneously with 3 other malignancies (esophagus, rectum, small bowel). Meanwhile, of 24 patients diagnosed with metachronous GC-MPC, 13 patients developed other malignancies after gastric cancer and 11 had other malignancies before gastric cancer.

Clinicopathologic data for synchronous and metachronous GC-MPC patients are described in Table 1. Twenty-nine (70.7%) patients were male, and the median age was 59 years (range, 27 to 79 years). The median time interval between the first cancer and the second cancer was 42 months (range, 11.5 to 225.2 months) and the time interval between the second and third cancer was 43 months (range, 7.7 to 133.3 months). Of the 39 evaluable patients, the TNM stage of the gastric cancer was early stage (I or II) in 34 cases (82.9%) and advanced stage (III or IV) in 5 cases (12.2%).

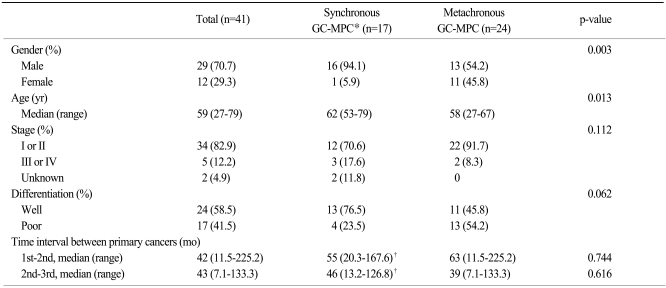

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic data for patients with gastric cancer in multiple primary cancers of more than three sites

*gastric cancer with multiple primary cancer, †this time interval indicates the onset duration between two cancers other than synchronous cancers.

Regarding stage, histology, and time interval between each cancer, there were no differences between the synchronous and metachronous groups. Patients in the metachronous group had more female (p=0.003) and younger (p=0.013) patients than those in synchronous group. The incidence of early-stage and poorly-differentiated tumor was slightly higher in gastric cancer patients with metachronous GC-MPC than in those with synchronous GC-MPC (91.7% vs. 70.6% for stage I/II and 54.2% vs. 23.5% for poorly differentiated histology, respectively). Excluding gastric cancer, we also analyzed the stages of the other primary cancers. In the subset analysis, early stage cancers were slightly more frequent in the synchronous group (25% vs. 42.3%) without statistical significance (p=0.217).

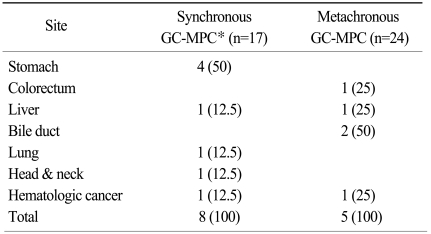

2. Site distribution of MPC

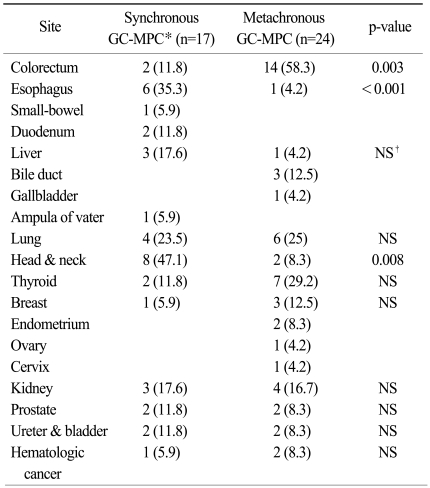

For a total of 41 patients, the most common site of MPC other than gastric cancer was colorectal cancer (n=16, 39%), followed by cancers in the lung (n=10, 24.4%), head & neck (n=10, 24.4%), and thyroid (n=9, 22%), as shown in Table 2 and Fig. 1A. We also analyzed site distribution of MPC according to the chronicity. Among the 17 synchronous gastric cancer patients, other common primary sites were as follows (Fig. 1B): head & neck (n=8, 47.1%), esophagus (n=6, 35.3%) and lung (n=4, 23.5%). In contrast, the most common sites for the 24 metachronous patients were: colorectum (n=14, 58.3%), thyroid (n=7, 29.2%) and lung (n=6, 25%). By way of comparison, esophageal cancer and head & neck cancer were demonstrated more frequently in the synchronous group (35.3% vs. 4.2%, p≤0.001 and 47.1% vs. 8.3%, p=0.008, respectively) while colorectal cancer was more frequent in the metachronous group (58.3% vs. 11.8%, p=0.003).

Table 2.

Site distribution of multiple primary cancers in patients with synchronous or metachronous gastric cancer

Parentheses indicate percentages.

*gastric cancer with multiple primary cancer, †not significant.

Fig. 1.

Site distribution of gastric cancer with multiple primary cancer (GC-MPC) of whole 41 patients (A) and metachronous/synchronous distribution (B).

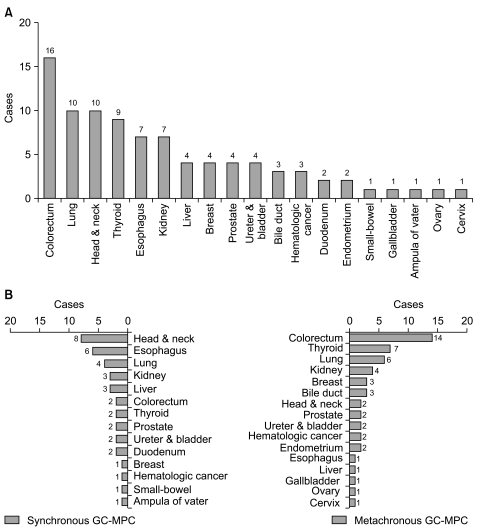

We also analyzed the site distribution of MPC in terms of gender distribution. Among 41 GC-MPC patients, 29 (70.7%) patients were male and 12 (29.3%) were female. In males, the most common site for MPC was the head & neck (n=10, 34.5%), followed by the colorectum (n=9, 31%), lung (n=7, 24.1%), kidney (n=7, 24.1%), and esophagus (n=6, 20.7%) as shown in Fig. 2A. In females, the most common site was the colorectum (n=7, 58.3%), followed by the thyroid (n=4, 33.3%), breast (n=4, 33.3%), and endometrium (n=3, 25%). When categorizing primary cancer sites based on smoking correlation, male patients demonstrated more frequent smoking related cancers such as head & neck, lung, kidney, esophagus, bladder cancers than female patients (n=34, 53.1%vs. n=4, 15.4%, respectively, p=0.002).

Fig. 2.

Site distribution according to gender differences (A), site distribution of metachronous multiple primary cancers (MPC) (B) and synchronous MPC (C) based on gender differences.

Fig. 2B and 2C compare the patients with synchronous primary cancer and those with metachronous primary cancer with regard to gender. In the metachronous group, the primary site distribution by gender was similar to that of the overall distribution (Fig. 2B). Conversely, in the synchronous group, the majority of patients were male and the primary site distribution by gender was different from the overall distribution (Fig. 2C). The most common sites in descending frequency were: the head & neck, esophagus, lung, liver, kidney, and colorectum.

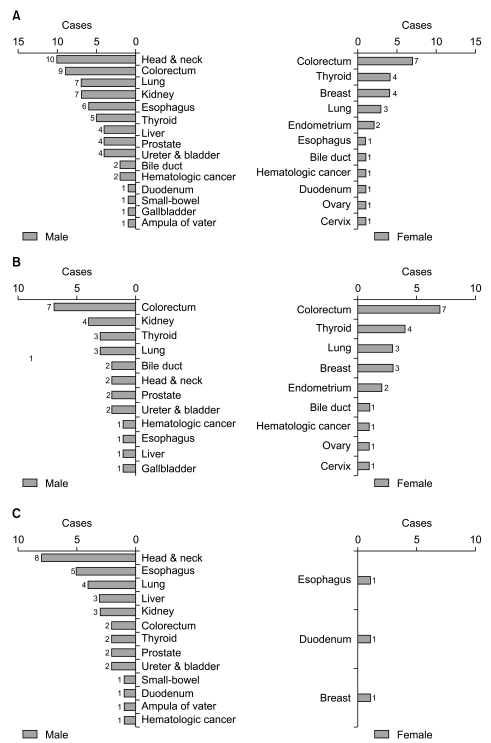

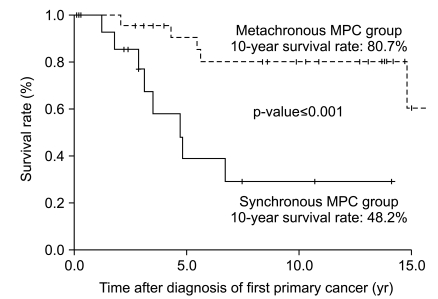

3. Survival outcome and cause of death

With a median follow-up duration for the whole group (41 patients) of 5.6 years (range, 0.1 to 23.2 years), the median overall survival duration and 10-year overall survival rate were 14.8 years (figure not shown) and 63.2%, respectively. The same figures for the synchronous and metachronous GC-MPC groups, respectively, were 4.7 years and 48.2%, and 14.8 years and 80.7% (p<0.001) (Fig. 3). We analyzed overall survival by gender, stage distribution, and gastric cancer histology. The survival differences between the synchronous and metachronous GC-MPC groups were significant in male (p=0.002), stage I/II (p=0.011) and well differentiated histology (p=0.01) groups, while the difference in female (p=0.629), stage III/IV (p=0.502) and poorly differentiated histology (p=0.154) groups did not reach statistical significance (Table 3).

Fig. 3.

Ten year overall survival difference between synchronous and metachronous gastric cancer with multiple primary cancer (GC-MPC).

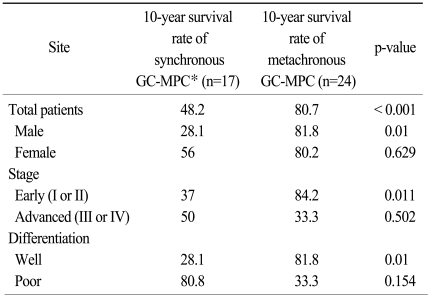

Table 3.

Difference of 10-year survival rate between synchronous and metachronous GC-MPC and subgroup analysis

Values indicate percentages. *gastric cancer with multiple primary cancer.

At the time of the analysis, 13 patients had died of either gastric or other primary cancers. Of these 13 patients, 8 patients were metachronous and 5 patients were synchronous. The causes of death are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Site distribution of tumors in patients who died of either gastric or another primary cancer

Parentheses indicate percentages. *gastric cancer with multiple primary cancer.

Discussion

We described the clinicopathologic features of a rare disease entity, GC-MPC, and analyzed its clinical significances to establish follow-up plan in cancer patients. During the 15 year investigation period, 0.1% of cancer patients had a MPC with three or more primary sites, and 36.3% of these were gastric cancer patients. This incidence is consistent with previous studies which reported prevalences of 0.029 to 1.7% (7,13,14).

Synchronous and metachronous gastric cancer patients showed somewhat different second cancer distribution. For metachronous gastric cancer patients, the most common cancer sites in descending order were: colorectum, thyroid, lung, kidney and breast. This finding is similar to the distribution of cancer in the general Korean population (15): stomach, colorectum, thyroid, breast, liver and lung in descending order of frequency. However, interestingly, the site distribution for synchronous gastric cancer demonstrated a different order: head & neck, esophagus, lung, and kidney. A possible reason for this phenomenon may be shared risk factors, especially cigarette smoking. Smoking is thought to be a risk factor for gastric cancer (16,17). The gender difference between synchronous and metachronous gastric cancer also supports this assumption. More male gastric cancer patients were diagnosed initially with multiple synchronous sites than female patients. In further subgroup analysis, smoking related cancers (head & neck, lung, esophagus, kidney, bladder) were significantly more common in males than in female patients. This suggests that smoking plays an important role in the increased incidence of synchronous disease in male patients. More careful examination of these sites may therefore be needed at the time of diagnosis and during the follow-up period of the gastric cancer. Further epidemiologic study is warranted to clarify this point.

In addition, the metachronous gastric cancer group contained more female and younger cases. These findings seem to be caused by different peak ages between males and females. According to the Korean cancer registry (15), there are two peak incidences in females. Breast and thyroid cancers in females were most frequently diagnosed in the fourth and fifth decades, whereas other malignancies like gastric cancer were often found in the seventh decade. Conversely, most cancers in males were diagnosed in the seventh decade. Therefore, females were at greater risk of being diagnosed with a first primary cancer of breast or thyroid cancer at a younger age, and those who survived their first primary cancer were at greater risk of developing a metachronous second primary cancer thereafter.

Although there is still little data for the underlying mechanism, three main explanations have been put forward for MPC. First, with longer survival, there is a greater likelihood of attack by many carcinogens, resulting in the development of more precancerous lesions. Additionally, assuming the risk of cancer is constant, it is more likely that precancerous lesions will develop into clinically significant cancers due to accumulation of genetic changes (6). This mechanism is explained by multistep carcinogenesis over time and the molecular and environmental changes of body associated with the aging process. Second, "field carcinogenesis" may be another mechanism for MPC pathogenesis (12,18,19). This theory implies that if cells in a similar microenvironment or with similarly susceptible cell biology are exposed to the same dose of carcinogens for the same duration of time, they have a similar risk of developing into cancer (20). The association of upper aerodigestive tract cancer and lung cancer is a well studied example of the field carcinogenesis theory (21,22). Lastly, genetic vulnerability due to specific genetic mutations may be responsible. MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS1, and PMS2 mutations in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer have been known to increase the genetic susceptibility for uterus, ovary, and stomach cancer (23).

The survival outcome in our study is consistent with previous studies (24,25), which suggests that metachronous patients have better prognoses than synchronous patients. In this study, the proportion of early stage (I or II) gastric cancer was 82.9%. Although recent developments in diagnosis and the introduction of mass screening programs have allowed increased detection of early gastric cancer, the proportion of early gastric cancer in this study is much higher than in the general population of Korea (50%). As patients with histories of cancer tend to undergo regular medical check-ups, this could lead to earlier diagnoses of new malignancies at curable stages (6). For these reasons, multiplicity of primary malignancies does not always imply a poor prognosis. Furthermore, metachronous status may sometimes result in a better survival outcome due to the detection of second or third primary cancer at earlier stages. Also, the better survival in the metachronous GC-MPC was maintained even when we did not include the favorable prognostic cancers such as thyroid or prostate cancer (data not shown).

Although our study had some unique findings, there were two potential limitations. First, the retrospective single center nature of our study may limit the generalization of our results. However, our analysis is based on data from the registry of the Yonsei Cancer Center, a major, 2000-bed tertiary hospital in Korea. This well organized and standardized tumor registry has records for every case of carcinoma in situ or carcinoma in our hospital since 1980. Therefore, the data from our registry can be interpreted as being broadly representative of Korea as a whole. Secondly, because of the long follow-up duration, some information was insufficient, and altered diagnostic and treatment strategies may have influenced the results. Therefore, further validation with nationwide data is needed, and this information might be useful in the establishment of a national diagnostic/treatment strategy for gastric cancer patients.

Conclusion

We reported the clinical features of multiple primary cancer in gastric cancer patients. To our knowledge, this is the first study describing the clinical features and prognosis of three or more primary sites in gastric cancer. The early detection of additional primary malignancies will enable prompt management with curative intent. Therefore, based on our results, further genetic and epidemiologic studies are warranted to clarify understanding of the pathogenesis and improve therapeutic outcome.

References

- 1.Otsuji E, Yamaguchi T, Sawai K, Hagiwara A, Taniguchi H, Takahashi T. Recent advances in surgical treatment have improved the survival of patients with gastric carcinoma. Cancer. 1998;82:1233–1237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ikeda Y, Mori M, Koyanagi N, Wada H, Hayashi H, Tsugawa K, et al. Features of early gastric cancer detected by modern diagnostic technique. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;27:60–62. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199807000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maehara Y, Okuyama T, Moriguchi S, Orita H, Kusumoto H, Korenaga D, et al. Prophylactic lymph node dissection in patients with advanced gastric cancer promotes increased survival time. Cancer. 1992;70:392–395. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920715)70:2<392::aid-cncr2820700204>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hiyama T, Hanai A, Fujimoto I. Second primary cancer after diagnosis of stomach cancer in Osaka, Japan. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1991;82:762–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1991.tb02700.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furukawa H, Hiratsuka M, Iwanaga T, Imaoka S, Kabuto T, Ishikawa O, et al. Treatments for second malignancies after gastrectomy for stomach cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 1996;43:194–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luciani A, Balducci L. Multiple primary malignancies. Semin Oncol. 2004;31:264–273. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2003.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Németh Z, Czigner J, Iván L, Ujpál M, Barabás J, Szabó G. Quadruple cancer, including triple cancers in the head and neck region. Neoplasma. 2002;49:412–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wegner HE. Multiple primary cancers in urologic patients. Audit of 19-year experience in Berlin and review of the literature. Urology. 1992;39:231–236. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(92)90296-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salminen E, Pukkala E, Teppo L, Pyrhönen S. Subsequent primary cancers following bladder cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A:303–307. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90246-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rabbani F, Grimaldi G, Russo P. Multiple primary malignancies in renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 1998;160:1255–1259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warren S, Gates O. Multiple primary, malignant tumors: a survey of the literature and statistical study. Am J Cancer. 1932;16:1358–1414. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moertel CG. Multiple primary malignant neoplasms: historical perspectives. Cancer. 1977;40(Suppl 4):1786–1792. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197710)40:4+<1786::aid-cncr2820400803>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayat MJ, Howlader N, Reichman ME, Edwards BK. Cancer statistics, trends, and multiple primary cancer analyses from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Oncologist. 2007;12:20–37. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-1-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hajdu SI, Hajdu EO. Multiple primary malignant tumors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1968;16:16–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1968.tb03965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Cancer Center. Annual report of Korea Central Cancer Registry. Goyang: National Cancer Center; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inoue M, Tsugane S. Epidemiology of gastric cancer in Japan. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:419–424. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.029330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujino Y, Mizoue T, Tokui N, Kikuchi S, Hoshiyama Y, Toyoshima H, et al. Cigarette smoking and mortality due to stomach cancer: findings from the JACC Study. J Epidemiol. 2005;15(Suppl 2):S113–S119. doi: 10.2188/jea.15.S113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furberg AH, Ambrosone CB. Molecular epidemiology, biomarkers and cancer prevention. Trends Mol Med. 2001;7:517–521. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(01)02162-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones PA. DNA methylation and cancer. Oncogene. 2002;21:5358–5360. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slaughter DP, Southwick HW, Smejkal W. Field cancerization in oral stratified squamous epithelium; clinical implications of multicentric origin. Cancer. 1953;6:963–968. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195309)6:5<963::aid-cncr2820060515>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Begg CB, Zhang ZF, Sun M, Herr HW, Schantz SP. Methodology for evaluating the incidence of second primary cancers with application to smoking-related cancers from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:653–665. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levi F, Randimbison L, Te VC, La Vecchia C. Second primary cancers in patients with lung carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;86:186–190. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990701)86:1<186::aid-cncr25>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ponz de Leon M, Bertario L, Genuardi M, Lanza G, Oliani C, Ranzani GN, et al. Identification and classification of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome): adapting old concepts to recent advancements. Report from the Italian Association for the study of Hereditary Colorectal Tumors Consensus Group. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:2126–2134. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marrano D, Viti G, Grigioni W, Marra A. Synchronous and metachronous cancer of the stomach. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1987;13:493–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moreaux J, Mathey P, Msika S. Gastric adenocarcinoma in the gastric stump after partial gastrectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 1991;38:517–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]