Abstract

Purpose

Compared to traditional macroemulsion propofol formulations currently in clinical use, microemulsion formulations of this common intravenous anesthetic may offer advantages. We characterized the pharmacokinetics and coagulation effects as assessed by thromboelastography of these formulations in swine.

Methods

Yorkshire swine (20-30 kg, either sex, n=15) were sedated, anesthetized with isoflurane, and instrumented to obtain a tracheostomy, internal jugular access, and carotid artery catheterization. Propofol (2 mg/kg, 30 s) was administered as macroemulsion (10 mg/mL; Diprivan®; n=7) or a custom (2 mg/kg, 30 s) microemulsion (10 mg/mL; n=8). Arterial blood specimens acquired pre- and post-injection (1 and 45 min) were used for thromboelastography. Arterial blood specimens (n=12 samples / subject, 60 min) were serially collected, centrifuged, and analyzed with solid-phase extraction with UPLC to determine propofol plasma concentrations. Non-compartmental pharmacokinetic analysis was applied to plasma concentrations.

Results

No changes were noted in thromboelastographic R time (P=0.74), K time (P=0.41), α angle (P=0.97), or maximal amplitude (P=0.71) for either propofol preparation. Pharmacokinetic parameters k (P=0.45), t1/2 (P=0.26), Co (P=0.89), AUC0-∞ (P=0.23), Cl (P=0.14), MRT (P=0.47), Vss (P=0.11) of the two formulations were not significantly different.

Conclusion

The microemulsion and macroemulsion propofol formulations had similar pharmacokinetics and did not modify thromboelastographic parameters in swine.

Keywords: Microemulsion, macroemulsion, propofol, swine, pharmacokinetics, thromboelastographic

Introduction

Microemulsions of propofol possess pharmacodynamic properties similar to conventional macroemulsions currently in use and may possess several major advantages [1]. Among the theoretical, as yet unproven in humans, improvements may be less pain on injection, reduced risk of bacterial growth, elimination of egg products, and a reduced lipid load [1]. For example, Date and Nagarsenker detailed that a propofol microemulsion caused significantly less pain during intravenous injection compared to a macroemulsion in a rat paw lick model [2]. On the other hand, others have demonstrated that human subjects receiving propofol report significantly more pain on injection (i.e., stinging) than when receiving traditional macroemulsions of propofol [3]. In addition, the lipid load associated with the macroemulsion carrier (composed mostly of soybean oil) may cause hypertriglyceridemia, the primary reason for therapeutic failure in patients convalescing in the intensive care unit [4]. As the microemulsion described herein has no oil carriers, this limitation does not apply to this type of formulation. For these reasons, interest has grown for these parenteral, nano-scaled formulations of propofol and other drugs [5-8].

The microemulsions in this report are stable, optically transparent, colorless formulations of propofol (which exists as an oil at room temperature) surrounded by surfactants and have mean particle sizes of approximately 10-50 nm in diameter [6]. In contrast, macroemulsions exist as relatively unstable, optically opaque systems of propofol embedded in a soybean oil carrier with multiple surfactants (e.g., glycerol, egg lecithin) and possess larger particle diameters of approximately 180 nm [9]. Several recent reports have detailed design, synthesis, and phase domain relationships of propofol microemulsions in which the drug serves dual roles as the active drug agent and as the oil core of the microemulsion even though many of the investigators have used different types and concentrations of surfactants [5-7,10]. In addition, the present and other investigators also have reported the use of these microemulsion formulations to anesthetize rats [7], dogs [6], horses [5], and humans [10], and noted that the microemulsions possess pharmacodynamic properties similar to those of macroemulsion formulations. In our own work, the pharmacokinetic profile of propofol microemulsions were not well defined, although we did observe similar plasma propofol concentrations for a macroemulsion and microemulsion after drug administration in dogs [6].

In addition to pharmacokinetic issues, some investigators have remain concerned that microemulsions may adversely interact with blood constituents [9,11,12]. Ryoo and colleagues hypothesized that the surfactants used in propofol microemulsions may interfere with cellular components of blood, but did not observe increased plasma hemoglobin concentrations using an in vitro model of hemolysis [9]. Likewise, neither Boscan and colleagues nor the present investigators noted significant changes in blood cellular indices (e.g., hematocrit, platelet concentration) or coagulation tests (e.g., prothrombin time) in horses and dogs, respectively, following propofol microemulsion administration [5,6]. Previously, thrombotic defects in human blood were demonstrated when blood was incubated with high concentrations of ionic surfactants that were used to construct other types of microemulsions [12]. Notwithstanding these observations, we wished to determine the possible effects of microemulsions on cellular components of blood using a comprehensive assay of coagulation function (i.e., thromboelastography).

Therefore, the purpose of this study was two-fold. First, we assessed the effects of a propofol microemulsion or macroemulsion on clotting in these swine as measured by thromboelastography. Second, we determined and compared the pharmacokinetic profiles of a microemulsion and a macroemulsion of propofol following an intravenous bolus administered to swine.

Materials and Methods

Propofol Microemulsion Formulation

The propofol microemulsion was prepared by using a method previously reported in detail by the investigators [6]. In brief, propofol (10 mg/mL, Albemarle Corporation, Baton Rouge, LA, U.S.A.), purified poloxamer 188 (50 mg/mL, BASF Corporation, Florham Park, NJ, U.S.A.), and sodium laurate (2.1 mg/mL, St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.) were agitated with ultra-pure normal saline (0.90 mg/mL NaCl) bulk media and stored under a nitrogen head, similar to the commercially available macroemulsion of propofol (Diprivan®, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, Wilmington, DE, U.S.A.) as oxidation of propofol can otherwise occur. In this microemulsion, propofol (which exists as an oily substance at room temperature) serves as an oil core surrounded by a halo of nonionic surfactant (i.e., purified poloxamer 188) and an ionic co-surfactant (sodium laurate). The function of the co-surfactant is to reduce the overall surface tension and decrease the total concentration of the non-ionic surfactant.

Animal Preparation

The research described in this paper adhered to the “Principles of Laboratory Animal Care” (NIH publication #85-23, revised in 1985). All experimental protocols and facilities were approved by the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. A porcine model was selected because swine cardiovascular physiology closely resembles that of humans, because swine are large enough to provide sufficient blood for repeated measurement of propofol concentrations, and because the investigators have previously worked with swine for other research purposes. Yorkshire swine (20-30 kg, either sex, n=8 for the microemulsion, n=7 for the macroemulsion) were purchased from the Teaching Swine Unit, Department of Animal Sciences, College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, U.S.A. Animals were then housed in pairs with adequate access to food and water at the University of Florida Large Animal Facility located in Progress Corporate Park, Alachua, FL, U.S.A. Starting the evening prior to experiments, the animals were held nil per os.

On the day of experiment, the swine were sedated using an intramuscular injection of ketamine (20 mg/kg) and xylazine (4 mg/kg) supplied by Webster Veterinary, Alachua, FL. Swine were weighed on a platform scale (Way Platform Scale, VSSI, Inc., Carthage, MO, U.S.A.) and transferred to an onsite operating table where they were placed in a supine position with the legs secured. Animals were further anesthetized by isoflurane (Webster Veterinary, Alachua, FL, U.S.A.) administered via face mask (SurgiVet, Webster Veterinary) with end-tidal concentrations of approximately 2-3%. After induction, anesthesia was maintained with end-tidal isoflurane concentrations of 0.8-1.2% in a mixture of air and oxygen with the inspired oxygen concentration approximately 50%. Vital signs were monitored using a conventional veterinary monitor (8100 Poet Plus, Criticare Systems, Inc., Waukesha, WI, U.S.A.). Three 14 gauge aluminum hub hypodermic needles (Monoject, Webster Veterinary,) were inserted intramuscularly into the right and left shoulder and left thigh for electrocardiogram lead placement. The oxyhemoglobin content (SpO2) was measured using a pulse oximeter placed across the tongue. A rectal temperature probe (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) was inserted for core body temperature monitoring. Body temperature was maintained at 37.0±1.0 °C with forced air flow warming blankets (Midwest Medical Supply, Plant City, FL, U.S.A.).

When swine were anesthetized and no longer responded to a noxious pinch by the investigators of the animal's toes, a tracheotomy was performed to secure the airway with subsequent insertion of a 7.0 mm internal diameter, cuffed endotracheal tube (Webster Veterinary). Successful completion of the tracheostomy was ensured by observation of a regularly formed capnograph with an end-tidal carbon dioxide tension of 35-50 mm Hg as measured by side-stream capnometry (8500 Poet IQ). Swine maintained spontaneous ventilation throughout the duration of the experiment.

Through the same skin incision, the right carotid artery and right internal jugular vein were cannulated directly. The arterial blood pressure was measured from the carotid artery cannula using a pressure transducer (BLPR, World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, U.S.A.) that was zeroed to the level of the animal's heart and displayed real-time on a monitor. Due to the swine's fasted state, a bolus of intravenous fluid (10 mL/kg, 0.9% sodium chloride, Webster Veterinary) was administered over 15-20 min followed by a continuous infusion of this fluid of approximately 50 mL/h. Following instrumentation, the animal was allowed 30 min to equilibrate before experiments commenced.

Experimental Protocol

Each swine was randomly assigned to one of two groups using a random number generator to receive either macroemulsion (Diprivan®, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, Wilmington, DE, U.S.A.) or the microemulsion propofol formulation. Each animal received either the microemulsion (n=8) or macroemulsion (n=7) formulation of propofol and did not crossover into the opposite limb of the experiment. In the macroemulsion group, although we began the experiment with eight animals, one animal could not be properly instrumented for the experiment and, thus, led to an unequal number of swine in each group. Before administration, the propofol microemulsion was filtered through a 0.45 μm sterile filter. Although commercial grade propofol microemulsions would not require filtration by the end-user, we used filtration for the laboratory-grade propofol microemulsion to remove any potential contaminants. The macroemulsion was not filtered as it was assumed to be sterile as packaged by the manufacturer. Thereafter, a bolus of propofol (2.0 mg/kg) over 30 s of the appropriate formulation was administrated through the intravenous cannula via a microprocessor-controlled syringe pump (SP2001, World Precision Instruments) to obviate confounding variables associated with manual injection. Thereafter, whole blood (1.0 mL) was aspirated from the arterial catheter at the following times after injection: 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 5.0, 7.5, 10.0, 15.0, 20.0, 30.0, 40.0, 50.0, and 60.0 min. All blood samples aspirated for measurement of propofol concentrations were centrifuged (Model 235C microcentrifuge Fisher Scientific) for 10 min. Thereafter, plasma (500 μL) was pipetted (Brinkmann Eppendorf Reference Series 2000 Pipetter, Fischer Scientific) into new microcentrifuge tubes and frozen on ice. Samples were then stored at 0 °C (Frigidaire, Martinez, GA, U.S.A.) for later measurement of plasma propofol concentrations. At the completion of the experiment, anesthesia was deepened by increasing the inspired isoflurane concentration to 5%. Subsequently, animals were euthanized with an intravenous injection of pentobarbital and phenytoin sodium (Beauthanasia-D, Webster Veterinary) with subsequent observation for asystole.

Thromboelastography

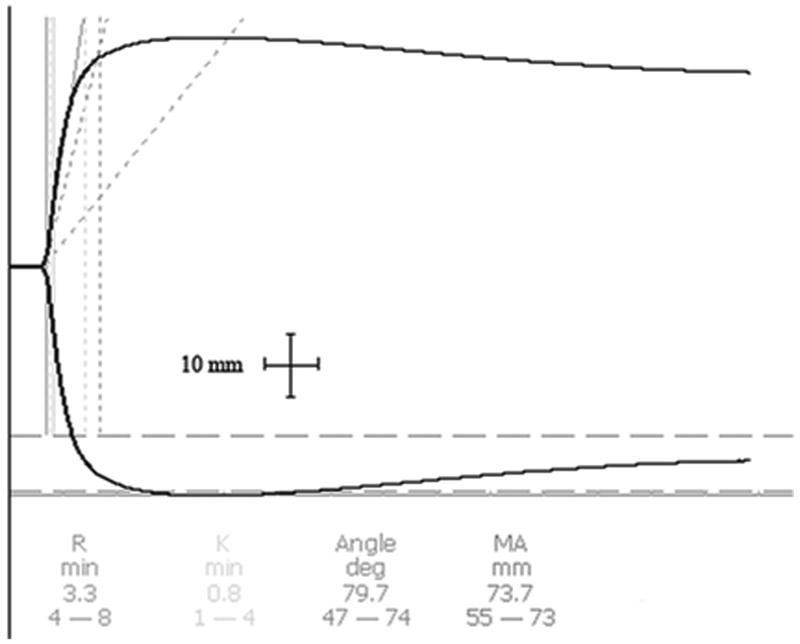

Thromboelastography (TEG) was selected as a measure of coagulation for several reasons. First, TEG is a functional test that summarizes the effects of the blood coagulation system whereas cell population assays (e.g., platelet concentration) note only the absolute concentration of platelets without any measurement of the cells' effectiveness. Some data already exist to demonstrate that surfactant can interfere with fibrin attachment on platelets without affecting the total platelet concentration. Second, TEG can concurrently assess a number of thrombotic functions. That is, the R time measures the time for fibrin formation, the K time assesses dynamics of protein interaction and clot formation, the alpha angle evaluates the acceleration of fibrin formation and cross-linking, and the MA (maximum amplitude) examines platelet formation with fibrin interactivity, respectively. Third, the investigators have used TEG in clinical practice and previously examined nano-scaled microemulsions with this device in earlier works [11].

Thromboelastographic (TEG) values were obtained with a hemostasis analyzer (TEG 5000, Mercury Medical, Clearwater, FL, U.S.A.) using a method similar to that previously reported by Morey and colleagues [6]. In brief, the device was calibrated daily using Biological Level I and II controls in both channels prior to experimentation. Blood samples (4.5 mL/sample) were drawn from the venous cannula just before propofol administration and then 1 and 45 min following the propofol bolus. In accordance with the manufacturer's instructions, blood was then transferred to a citrated vial (18.0 mg/vial, Webster Veterinary), inverted 5 times and allowed to rest for 10 min. Then, 1.0 mL of the citrated blood was pipetted into a 1% kaolin microcentrifuge tube (Mercury Medical). This tube was inverted 5 times. Calcium chloride (20 μL) was pipetted into a clean/empty disposable cup (Mercury Medical) in the TEG analyzer. Then, an aliquot (340 μL) of kaolin-treated, citrated blood was added to the disposable cup. Samples were allowed to run to completion for the duration of 60 min. TEG measurements included four routinely measured parameters: the R time, K time, alpha angle, and MA (maximum amplitude). These parameters were automatically calculated from the raw tracing by use-specific software (TEG 4.1.54, Mercury Medical) and a laptop computer (Latitude D510, Dell Computer Corporation, Round Rock, TX, U.S.A.) interfaced with the TEG as recommended by the TEG manufacturer.

Measurement of Plasma Propofol Concentrations

Plasma propofol concentrations were determined employing sample preparation by solid-phase extraction with hydrophilic-lipophilic balance cartridges and employing an ultra-high pressure liquid chromatographic (UPLC) technique adapted from methods previously reported by our and other groups [12-14]. In brief, the UPLC (AcQuity Ultra Performance LC System, Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) technique permits analytical methods wherein run times are significantly decreased. In addition, a minimal deadspace volume of the whole system allows very short equilibration times. UPLC separations were achieved using an Acquity UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 × 50 mm, Waters). The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile–water (70:30, v/v). The flow rate was 0.1 mL/min. The detection was made using a wavelength of 273 nm via an UPLC photodiode array detector. The analyses were performed at ambient temperature (20 °C). The precision of the propofol peak retention time in fresh plasma was 4.43±0.04 min with a relative standard deviation of 0.8% over the relevant concentration range. Measurements were performed in triplicate. The SPE chromatography method validation for inter-and intra-day has been reported in our previous publication (12). The inter-and intra-day propofol UPLC method precision test was made by injecting standard propofol concentrations (0.25, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 3.0 and 3.5 μg/ml) six times. The percentage relative standard deviations (%RSD) were found in range from 1.1-5.0%. The lower limit of quantification of propofol was 0.25 μg/ml.

TEG Analysis

Prior to parametric testing, the assumption of normality was validated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test with Lilliefors' correction. For TEG data, two-way (factor 1: formulation; factor 2: time at 0, 1, and 45 min), repeated measures analysis of variance was performed using commercially available statistical software (SigmaStat 3.1, Systat Software, Inc., Point Richmond, CA, U.S.A.). Measurements are reported as mean±standard deviation. P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Pharmacokinetic analysis

The plasma concentration-time data for each animal were assessed in a noncompartmental pharmacokinetic analysis using WinNonlin (Pharsight Corporation, Mountain View, CA, USA) software. A total of 15 animals were analyzed, 7 of which received the macroemulsion and 8 of which received the microemulsion formulation. Elimination half life, t½, is obtained as ln(2)/k, where k is the negative slope of the terminal linear phase of the ln(C) versus time plot. The initial plasma concentration (Co) is estimated by back-extrapolating the ln(C) versus time plot until time zero. The trapezoidal rule was used to calculate the area under the concentration versus time curve (AUC). The total body clearance CL is calculated as the dose/AUC, where AUC is the area under the curve from time zero to infinity. AUC is equal to AUC0-tlast+Clast/k, where Clast is the last measured concentration, and AUC0-tlast is the area under the curve from time zero until the last measured concentration. The mean residence time (MRT) is calculated as AUMC/AUC, where AUMC is the area under the first moment curve. The AUMC is obtained from a plot of plasma concentration multiplied by time versus time. The volume of distribution at steady state, Vss is calculated as the MRT*CL. Measurements are reported as mean±standard deviation. Each pharmacokinetic parameter among the macroemulsion propofol formulation subject group was compared to the microemulsion propofol subject group using a two-tailed, two-sample t-test assuming unequal variances. P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

TEG Analysis

Blood was aspirated from the internal jugular catheter for swine treated with the propofol microemulsion (n=8) or macroemulsion (n=7) formulations for measurement of TEG. Representative raw data of the TEG tracings are illustrated in figure 1. No significant differences between the two formulations were noted with respect to the R time, K time, α angle, or maximal amplitude as detailed in the tabulated summary data (table 1). Although not the focus of this study, we noted a tendency for the R time to decrease from time 0 min to times 1 and 45 min in both the macro- and micro-emulsion groups, but this change did not achieve statistical significance (P=0.14).

Figure 1.

Representative, ‘print screen’ computer-generated traces and measurements demonstrating the effects of a propofol (2 mg/kg) microemulsion (panel A) or macroemulsion (panel B) on the thromboelastograph of porcine blood obtained 1 min after injection. For the time noted along the abscissa, 1mm is equal to 1 min. The normal ranges of parameters for humans are noted by the hyphenated values

Table 1.

Coagulation parameters measured by thromboelastography for swine treated with a propofol microemulsion or macroemulsion.

| Parametera | Time (min) |

Microemulsionb | Macroemulsionb | Pc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R time (min) | Baseline | 4.4 ± 0.7 | 3.5 ± 0.9 | 0.74 |

| 1 | 2.8 ± 1.4 | 3.0 ± 1.1 | ||

| 45 | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 3.5 ± 1.8 | ||

| K time (min) | Baseline | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.41 |

| 1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | ||

| 45 | 0.8 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | ||

| α-angle (°) | Baseline | 74.4 ± 5.8 | 77.2 ± 4.2 | 0.97 |

| 1 | 79.9 ± 2.0 | 78.8 ± 2.5 | ||

| 45 | 79.4 ± 1.8 | 77.9 ± 3.5 | ||

| Maximum Amplitude (mm) | Baseline | 78.1 ± 2.0 | 78.0 ± 1.9 | 0.71 |

| 1 | 74.7 ± 2.2 | 74.9 ± 2.1 | ||

| 45 | 78.0 ± 2.6 | 76.5 ± 2.0 |

Coagulation parameters were determined before injection (Baseline) and at times 1 min and 45 min following injection as measured by thromboelastography and automated calculation of the four parameters.

Values are represented as mean ± standard deviation for swine treated with a propofol (2 mg/kg) microemulsion (n=8) or macroemulsion (n=7).

The P value noted refers to possible differences due to a change in formulation (microemulsion compared to macroemulsion). Representative thromboelastographic tracing of single time points for the microemulsion or macroemulsion are illustrated in figure 1.

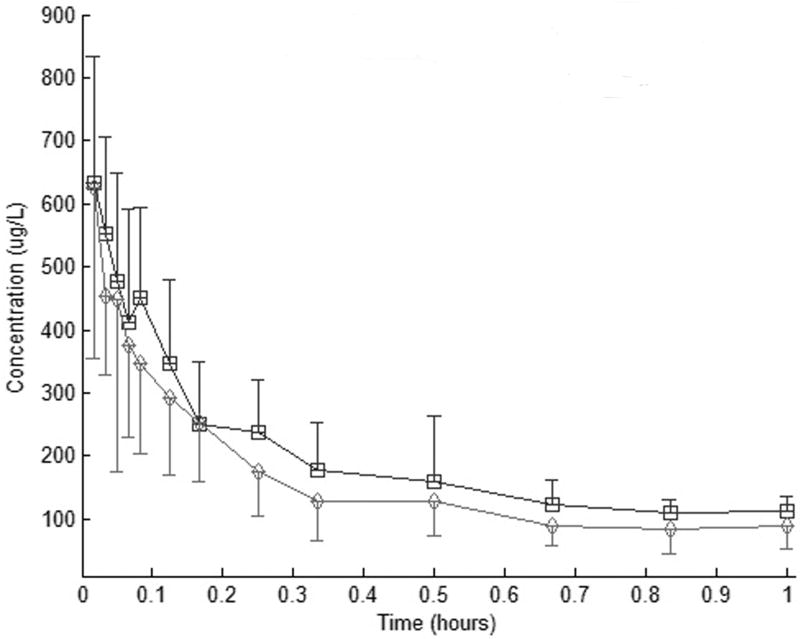

Pharmacokinetic Analysis

The summary propofol plasma profiles for the microemulsion and macroemulsion are shown in figure 2. Pharmacokinetic parameters resulting from noncompartmental analysis are listed in table 2. The results show the pharmacokinetic parameters (k, t1/2, Co, AUC0-∞, CL, MRT, Vss) of the two formulations are not significantly different.

Figure 2.

Propofol plasma concentration (mean7SD) after i.v. bolus injection (2 mg/kg) of a macroemulsion (&) or microemulsion (B) propofol formulations in swine

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic parameters (mean±SD) for a macroemulsion and microemulsion propofol formulation after bolus intravenous administration (2 mg/kg) in healthy, isoflurane-anesthetized swine.

| Parameter | Macroemulsiona | Microemulsiona | Pb |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 7 | 8 | |

| k (h-1) | 1.32 ± 0.44 | 1.16 ± 0.56 | 0.45 |

| t1/2 (h) | 0.59 ± 0.24 | 0.72 ± 0.32 | 0.26 |

| Co (μg/L) | 756.9 ± 303.0 | 933.3 ± 589.4 | 0.89 |

| AUC0-∞ (h*μg/L) | 282.9 ± 110.7 | 259.6 ± 126.2 | 0.23 |

| Cl (L/h/kg) | 7.61 ± 5.47 | 10.68 ± 8.25 | 0.14 |

| MRT (h) | 0.80 ± 0.31 | 0.90 ± 0.40 | 0.47 |

| Vss (L/kg) | 7.49 ± 4.70 | 7.52 ± 2.19 | 0.11 |

Values are represented as mean ± standard deviation for swine treated with a propofol (2 mg/kg) microemulsion (n=8) or macroemulsion (n=7).

The P value noted refers to possible differences due to a change in formulation (microemulsion compared to macroemulsion).

Discussion

TEG Data

Earlier we reported that some surfactants, at high concentrations, used to construct microemulsions may adversely affect parameters of clotting as measured in human blood using thromboelastography [12]. Although no change in platelet concentrations were observed in dogs or horses receiving propofol microemulsion in earlier studies [5,6], platelet count measurements are not sensitive to determine if platelet function has changed with preservation of the overall number of platelets. Therefore, we investigated if comprehensive assays of clotting (i.e., the TEG parameters) could detect altered hemostasis and did not observe any significant changes following administration of either the microemulsion or macroemulsion.

Microemulsions of the type used in this study are composed of an oil (i.e., propofol) and one or more surfactants. In the present microemulsion, purified poloxamer 188 is the major surfactant used to construct the formulation although sodium laurate is also included as a co-surfactant. For this reason, prior information about the effects of this surfactant is pertinent. The data reported herein are consistent with previously reported information showing that while purified poloxamer 188 causes reductions in TEG maximal amplitude, possibly by interfering with fibrinogen, this effect occurs at concentrations exceeding 0.03 mM [12,15]. In another study, Orringer and colleagues hypothesized that intravenously administered purified poloxamer 188 would reduce cell-cell, cell-protein, and protein-protein interactions and thereby improve blood flow in the setting of chest crisis in sickle cell disease patients [16]. They intravenously administered large doses (100 mg/kg for 1 h followed by 30 mg/kg per hour for 47 h) of purified poloxamer 188, but demonstrated only minimal change in the chest crisis duration between control and treated groups. Our own data are in agreement with those of Orringer and colleagues in that we also did not detect any changes in TEG parameters, an aggregate index of a complex series of cell-protein interactions, but greater doses of the surfactants associated with propofol microfol infusions (vis-à-vis single bolus dosing used in this study) have not yet been conducted. We conclude that the mass of purified poloxamer 188 and sodium laurate did not measurably affect coagulation as measured by the TEG following a 2 mg/kg bolus dose.

Pharmacokinetic Data

Other investigators have also studied the pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic properties of propofol microemulsions, albeit in other species and with different surfactants that compose these formulations. In horses, Boscan and colleagues administered a propofol (1.0 mg/mL) microemulsion or macroemulsion and noted a statistically significant longer time to the “first anesthetic effect” with the microemulsion (1.07±0.15 and 0.94±0.19 min, respectively) although the absolute increase in time (i.e., 8 s) was minimal [5]. Although Boscan and colleagues did not measure propofol concentrations in the horses' blood, the slightly prolonged induction time alludes to a longer time for propofol release in horses [5]. In contrast to Boscan's report and in agreement with the present data, Kim and colleagues studied the properties of a propofol microemulsion and macroemulsion to anesthetize humans and concluded that efficacy and safety of the two formulations were not different at the doses used in their investigation [10]. In contrast, Lee and colleagues used continuous infusions of propofol microemulsion in rats to demonstrate that the microemulsion formulations caused higher than predicted concentrations of propofol [17]. Besides possible species-species variation that potentially confounds evaluations between studies, these differing findings may be due to variations in the composition and concentrations of the surfactants associated with microemulsion construction that make direct comparisons problematic. For example, the surfactants used in these aforementioned investigators studies were polyethylene glycol 660 hydroxystearate [5,10], tetrahydrofurfuryl alcohol [10], purified poloxamer 188 [6,17], caprylic acid [6], glycerin [17]. For this reason, even subtle changes in the surfactant type or composition may have marked effects on the physical characteristics (e.g., size, pH, stability) and pharmacokinetic properties of the microemulsion.

Previously, both we and others noted a secondary peak in propofol concentrations following administration of a propofol microemulsion or macroemulsion to both dogs and humans [6,18-20]. This secondary peak is a much lesser concentration (∼10%) compared to the first peak and occurs when animals or subjects emerge from anesthesia. Suggested hypotheses for its existence include experimental artifact, physiological changes (e.g., increased cardiac output, loss of peripheral venodilation with resultant influx of propofol) associated with emergence from anesthesia, and possibly splenic contraction in canines [18]. In the present study, no secondary peak was noted. We find it more likely that the secondary peak is associated with physiological changes associated with anesthetic emergence for several reasons. First, the animals reported herein were euthanized following the study and, therefore, did not emerge from anesthesia. Second, swine can contract their own spleens via α-adrenoceptor stimulation, but no secondary peak was observed in the present study [21,22]. In fact, Gentile and colleagues advocate for a splenectomized design in swine studies that claim to resemble human physiology [21]. Third, these reports from four independent groups suggest that experimental artifact has diminishing probability as a cause for the secondary peak. Although not the focus of this study, we find that the data reported herein favor the hypothesis relying on physiological changes associated with emergence. A specific study with an infusion of propofol would be needed to more fully confirm the hypothesis.

Conclusion

In summary, we have demonstrated that a propofol microemulsion has pharmacokinetics similar to a propofol macroemulsion in a swine model. Furthermore, this surfactant load associated with the propofol microemulsion did not significantly modify TEG profile in these animals. In the future, we wish to expand our investigations of this propofol microemulsion from single bolus administration to a longer, continuous infusion to more fully delineate the formulation's properties when given in a way to resemble clinical practice where propofol is used for both induction (bolus) and maintenance (infusion) of anesthesia.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (Bethesda, MD, U.S.A.) via grant [2R44GM072142] and by NanoMedex Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Fitchburg, WI, U.S.A.).

The methodology for preparation of the propofol microemulsion used in this study is protected by United States Patents 6,623,765 and 6,638,537, which are assigned to the University of Florida, Research Foundation, Incorporated (Gainesville, FL) and licensed to NanoMedex Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Drs., Dennis, Gravenstein, Modell, Morey, and Shah as well as the University of Florida own stock in NanoMedex Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and as such may benefit financially as a result of the outcomes of the research reported in this publication. Drs. Morey and Gravenstein serve as board members for NanoMedex Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Abbreviations

- AUC

area under the concentration versus time curve

- AUMC

area under the first moment curve

- Co

initial plasma concentration

- CL

total body clearance

- MA

maximal amplitude of the TEG

- MRT

mean residence time

- TEG

thromboelastography

- t½

elimination half life

- UPLC

ultra-high pressure liquid chromatography

- Vss

volume of distribution at steady state

References

- 1.Date AA, Nagarsenker MS. Parenteral microemulsions: An overview. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2008;355:19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Date AA, Nagarsenker MS. Design and evaluation of microemulsions for improved parenteral delivery of propofol. Aaps Pharmscitech. 2008;9:138–45. doi: 10.1208/s12249-007-9023-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sim JY, Lee SH, Park DY, Jung JA, Ki KH, Lee DH, Noh GJ. Pain on injection with microemulsion propofol. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;67:316–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03358.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knibbe CAJ, Naber H, Aarts LPHJ, Kuks PFM, Danhof M. Long-term sedation with propofol 60 mg ml(-1) vs. propofol 10 mg ml(-1) in critically ill, mechanically ventilated patients. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 2004;48:302–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2004.0339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boscan P, Steffey EP, Farver TB, Mama KR, Huang NJ, Harris SB. Comparison of high (5%) and low (1%) concentrations of micellar microemulsion propofol formulations with a standard (1%) lipid emulsion in horses. Am J Vet Res. 2006;67:1476–83. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.67.9.1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morey TE, Modell JH, Shekhawat D, Shah DO, Klatt B, Thomas GP, Kero FA, Booth MM, Dennis DM. Anesthetic properties of a propofol microemulsion in dogs. Anesth Analg. 2006;103:882–7. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000237126.57445.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morey TE, Modell JH, Shekhawat D, Grand T, Shah DO, Gravenstein N, McGorray SP, Dennis DM. Preparation and anesthetic properties of propofol microemulsions in rats. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:1184–90. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200606000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karasulu HY. Microemulsions as novel drug carriers: the formation, stability, applications and toxicity. Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery. 2008;5:119–35. doi: 10.1517/17425247.5.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryoo HK, Park CW, Chi SC, Park ES. Development of propofol-loaded microemulsion systems for parenteral delivery. Arch Pharm Res. 2005;28:1400–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02977908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim KM, Choi BM, Park SW, Lee SH, Christensen LV, Zhou J, Yoo BH, Shin HW, Bae KS, Kern SE, Kang SH, Noh GJ. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of propofol microemulsion and lipid emulsion after an intravenous bolus and variable rate infusion. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:924–34. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000265151.78943.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aparicio RM, Garcia-Celma MJ, Vinardell MP, Mitjans M. In vitro studies of the hemolytic activity of microemulsions in human erythrocytes. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 2005;39:1063–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morey TE, Varshney M, Flint JA, Seubert CN, Smith WB, Bjoraker DG, Shah DO, Dennis DM. Activity of microemulsion-based nanoparticles at the human bio-nano interface: concentration-dependent effects on thrombosis and hemolysis in whole blood. Journal of Nanoparticle Research. 2004;6:159–70. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bajpai L, Varshney M, Seubert CN, Dennis DM. A new method for the quantitation of propofol in human plasma: efficient solid-phase extraction and liquid chromatography/APCI-triple quadrupole mass spectrometry detection. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2004;810:291–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bajpai L, Varshney M, Seubert CN, Stevens SM, Jr, Johnson JV, Yost RA, Dennis DM. Mass spectral fragmentation of the intravenous anesthetic propofol and structurally related phenols. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2005;16:814–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bohner M, Ring TA, Rapoport N, Caldwell KD. Fibrinogen adsorption by PS latex particles coated with various amounts of a PEO/PPO/PEO triblock copolymer. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2002;13:733–46. doi: 10.1163/156856202320269184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orringer EP, Casella JF, Ataga KI, Koshy M, Adams-Graves P, Luchtman-Jones L, Wun T, Watanabe M, Shafer F, Kutlar A, Abboud M, Steinberg M, Adler B, Swerdlow P, Terregino C, Saccente S, Files B, Ballas S, Brown R, Wojtowicz-Praga S, Grindel JM. Purified poloxamer 188 for treatment of acute vaso-occlusive crisis of sickle cell disease: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;286:2099–106. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.17.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee EH, Lee SH, Park DY, Ki KH, Lee EK, Lee DH, Noh GJ. Physicochemical properties, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of a reformulated microemulsion propofol in rats. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:436–47. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318182a486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zoran DL, Riedesel DH, Dyer DC. Pharmacokinetics of propofol in mixed-breed dogs and greyhounds. Am J Vet Res. 1993;54:755–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cockshott ID, Briggs LP, Douglas EJ, White M. Pharmacokinetics of propofol in female patients. Studies using single bolus injections. Br J Anaesth. 1987;59:1103–10. doi: 10.1093/bja/59.9.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kay NH, Uppington J, Sear JW, Allen MC. Use of an emulsion of ICI 35868 (propofol) for the induction and maintenance of anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 1985;57:736–42. doi: 10.1093/bja/57.8.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gentile BJ, Szlyk-Modrow PC, Sils IV, Krestel BA, Tartarini KA, Francesconi RP. Splenic effects on hemodynamics induced by hypothermia and rewarming in miniature swine. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1995;66:143–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stubenitsky R, Verdouw PD, Duncker DJ. Autonomic control of cardiovascular performance and whole body O2 delivery and utilization in swine during treadmill exercise. Cardiovasc Res. 1998;39:459–74. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]