Abstract

In 1929, August Krogh identified the matching of oxygen (O2) supply with demand in skeletal muscle as a fundamental physiological process. In the intervening decades, much research has been focused on elucidating the mechanisms by which this important process occurs. For any control system to be effective, there must be a means by which the need is determined and a mechanism by which that information is coupled to an appropriate response. The focus of this review is to highlight current research in support of the hypothesis that the mobile erythrocyte, when exposed to reduced O2 tension, releases ATP in a controlled manner. This ATP interacts with purinergic receptors on the endothelium producing both local and conducted vasodilation enabling the erythrocyte to distribute perfusion to precisely match O2 delivery with need in skeletal muscle. If this is an important mechanism for normal physiological control of microvascular perfusion, defects in this process would be anticipated to have pathophysiological consequences. Individuals with either type 2 diabetes (DM2) or pre-diabetes have microvascular dysfunction that contributes to morbidity and mortality. DM2 erythrocytes and erythrocytes incubated with insulin at levels similar to those seen in pre-diabetes fail to release ATP in response to reduced O2 tension. Knowledge of the components of the signal transduction pathway for low O2-induced ATP release suggest novel therapeutic approaches to ameliorating this defect. Although the erythrocyte may be but one component of the complex O2 delivery process, it appears to play an important role in distributing oxygen within the microvasculature.

Keywords: Red blood cells, Adenosine triphosphate, tissue oxygenation, blood flow

Introduction

In 1929 August Krogh stated that, with respect to skeletal muscle, “it seemed to me clear that there must be some mechanism regulating the conditions of supply [of oxygen]. With constant conditions, the facilities for transport must be either ridiculously out of proportion to the requirements of the muscles during rest or ridiculously inadequate to meet their needs during heavy work.” (Krogh 1959). This seminal observation identified the matching of oxygen (O2) supply with demand in skeletal muscle as a fundamental physiological process. The first model for O2 transport in skeletal muscle was proposed by Krogh and Erlang (Krogh 1919) based on the assumption that each capillary is the sole supplier to a cylindrical region of tissue surrounding it (the Krogh cylinder). Although elegant, this simple model does not take into account the complexity of O2 exchange within the microvasculature (Ellsworth & Pittman 1990; Ellsworth et al. 1994) and therefore cannot adequately explain the sensitivity and accuracy of the system that matches O2 delivery to metabolic need in skeletal muscle. Subsequently, research into additional mechanisms involved in providing this tissue with appropriate amounts of O2 has been undertaken by numerous investigators. Studies have evaluated the sensitivity of individual arterioles to O2 (Duling 1974, Jackson 1987, Pittman & Duling 1973), the role of metabolites released within the tissues or vessels themselves (Hester, 1993) and/or the presence of a localized sensor within the tissue. Although evidence exists in support of each of these mechanisms, none either fully explains the sensitivity of the response of the microcirculation to tissue O2 needs or accounts for the complexity of the hemodynamic and O2 transport properties of the vessels which comprise the architecturally complex skeletal muscle microvasculature.

Fundamentally, a system designed to alter perfusion distribution to adequately deliver O2 to tissue must incorporate a means to detect and quantify that need and subsequently affect an appropriate alteration in blood flow (O2 supply). The coupling of these two critical processes requires interplay among tissue gas exchange, tissue metabolism and vascular smooth muscle function and must be regulated within a narrow range (Hollenberg 1971). It is well recognized that the vascular endothelium serves a critical role in controlling vascular caliber (Furchgott & Zawadzki, 1980, Busse et al. 1985, Vahnoutte et al. 1991) and coordinating the response to diverse local stimuli (Furchgott & Zawadzki 1980, Dietrich 1989, Segal et al. 1989, Segal & Duling, 1989, Dietrich & Tyml 1992). One intriguing possibility under active investigation is that a component of the O2 transport pathway itself is responsible for sensing oxygen need and altering perfusion to adequately supply oxygen to skeletal muscle.

Erythrocyte-derived ATP and blood flow regulation

The primary O2 carrier in mammalian systems is the haemoglobin containing anucleate erythrocyte. In addition to haemoglobin, the erythrocyte contains numerous receptors, effector proteins, channels and pumps as well as an active glycolytic pathway that maintains milimolar amounts of ATP within the cell. In 1992, Bergfeld and Forrester reported that human erythrocytes release ATP in a controlled fashion in response to exposure to low O2 in the presence of hypercapnia. A later study by Ellsworth et al. (1995) confirmed this finding in a study using hamster erythrocytes exposed to reduced O2 in the absence of hypercapnia implicating the decrease in O2 as the stimulus for ATP release. Similar results have been obtained for erythrocytes from humans, rabbits and rats (Ellsworth 2000).

Since these initial observations, several lines of evidence have provided support for the hypothesis that the erythrocyte, via its capacity to release ATP in response to exposure to reduced O2 tension, serves a regulatory role in the control of skeletal muscle perfusion (Ellsworth et al. 2009). If erythrocyte-derived ATP contributes to the matching of blood flow with tissue O2 requirements, then it is crucial to first establish that ATP present in the vascular lumen produces not only local vasodilation, but also dilation that is conducted to upstream arterioles (Kurjiaka & Segal 1995). In in situ studies in the hamster cheek pouch retractor muscle, when ATP was injected into the lumen of individual arterioles (30–50 µm), vasodilation was detected locally as well as 1210 +/− 494 µm upstream from the site of injection (McCullough et al. 1997). Although these studies demonstrate that ATP stimulates conducted vasodilation in arterioles, the lowest PO2 levels and thus the greatest concentration of ATP would be expected to be found in the capillaries and venules of skeletal muscle. Importantly, ATP administered into venules in the skeletal muscle microcirculation also elicits vasodilation that is conducted through the capillary network to upstream feed arterioles. This response was shown to result in significant increases in erythrocyte flux in second order arterioles, terminal arterioles and capillaries of 63, 50 and 92%, respectively (Collins et al. 1998). The increase in erythrocyte flux was accompanied by a significant increase in tissue O2 tension (Ellsworth 2000). These results support a physiological role for ATP in the regulation of microvascular perfusion in skeletal muscle.

Although the studies in which ATP is added directly into the vascular lumen demonstrate that this adenine nucleotide stimulates both local and conducted vasodilation, they do not establish the source of ATP released in response to increased O2 demand in the skeletal muscle microcirculation. To address this critical issue, arterioles were isolated from the hamster cheek pouch retractor muscle (~50 µm in diameter), cannulated, placed in a tissue bath and perfused with either buffer or buffer containing erythrocytes. When buffer-perfused vessels were exposed to reduced extraluminal O2, as would occur if local O2 demand were increased, there was no vasodilation. In contrast, when these same vessels were perfused with buffer containing oxygenated human or rabbit erythrocytes, decreased extraluminal O2 stimulated dilation of the arteriole (Sprague et al. 2009, Hanson et al. 2009). These results are consistent with an earlier study in rat cerebral arterioles in which dilation in response of low extraluminal O2 tension occurred only when the vessels were perfused with buffer containing rat erythrocytes (Dietrich et al. 2000). In this study, dilation in the presence of erythrocytes was associated with increased ATP in the vessel effluent. One interpretation of these findings is that ATP, released from erythrocytes when these cells are exposed to reduced O2 tension, is critical for the dilation of the arterioles.

A signaling pathway for low O2-induced ATP release from erythrocytes

The finding that erythrocytes release ATP in a controlled manner in response to exposure to reduced O2 suggests that these cells possess a specific signaling pathway which mediates that release. Over the past several years, a pathway that couples exposure to low O2 with ATP release from erythrocytes has been described (Figure 1). This pathway includes the heterotrimeric G-protein, Gi (Olearczyk et al. 2004), adenylyl cyclase (AC) (Sprague et al. 2005), protein kinase A (Sprague et al. 2001) and the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) (Sprague et al. 1998). Although these proteins are clearly components of the signaling pathway for low O2-induced ATP release, characterization of the mechanism by which low O2 activates Gi and the identity of the final conduit for ATP release have been the most difficult to establish.

Figure 1.

Proposed mechanism by which erythrocytes alter regional perfusion to enable the matching of oxygen (O2) supply with demand in skeletal muscle. When erythrocytes enter a tissue region in which O2 demand exceeds supply, O2 is released from erythrocytes. The fall in O2 saturation (SO2) of haemoglobin results in activation of the heterotrimeric G-protein, Gi, activating adenylyl cyclase (AC) which results in increases in 3’5’-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), activation of protein kinase A (PKA) and the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) and, ultimately, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) release via pannexin 1. The cAMP required for ATP release is hydrolyzed by phosphodiesterase 3 (PDE3). Released ATP binds to purinergic receptors on the endothelium stimulating production of vasodilators that relax vascular smooth muscle locally and initiate dilation that is also conducted upstream. Other abbreviations: EDHF = endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor, PGI2 = prostacyclin, NO = nitric oxide, AMP = adenosine monophosphate, α, β and γ = G protein subunits.

Jagger et al. (2001) demonstrated that a critical trigger for ATP release from erythrocytes is a decrease in haemoglobin O2 saturation, consistent with a mechanism suggested by previous studies (Stein & Ellsworth 1993). More recently, Sridharan et al. (2010B) reported that low O2-induced ATP release is linked to deformation of the erythrocyte membrane. These studies led to the hypothesis that as membrane-bound haemoglobin is desaturated, the resulting conformational change in the molecule produces local membrane deformation which serves as a direct mechanical stimulus for activation of Gi and, consequently, ATP release. Such a mechano-transduction mechanism for Gi activation has been observed in other cell types (Gudi et al. 1996, Gudi et al.1998). Taken together, these studies are consistent with the hypothesis that desaturation of haemoglobin, as would occur when erythrocytes enter an area of skeletal muscle where O2 demand is increased, activates a well defined signaling pathway for ATP release.

A perplexing question has been the mechanism by which ATP exits the erythrocyte when these cells are exposed to reduced O2 tension. ATP can be released from cells via vesicular transport, cell lysis or via channels or transporters. Since erythrocytes do not form releasable vesicles and cell lysis cannot be responsible for regulated ATP release, the likely mechanism is via ATP channels or transporters. Several proteins have been suggested to function as ATP conduits including CFTR, connexin hemichannels, voltage dependent anion channels, volume regulated anion channels as well as ATP binding cassette proteins (Abraham et al. 1993, Liu et al. 2008, Okada et al. 2004, Scemes et al. 2007, Sprague et al. 1998). Recently, another channel for ATP release, pannexin 1, was shown to be present in erythrocyte membranes and to mediate ATP release in response to depolarization with potassium or osmotic stress (deformation) (Locovei el al. 2006). In studies in our laboratory, pannexin 1 has been shown to be responsible for ATP release in response to exposure of erythrocytes to low O2 tension (Sridharan et al. 2010A). However, other ATP conduits are also present in erythrocyte membranes as shown by the finding that inhibitors of pannexin 1 do not prevent ATP release from erythrocytes in response to receptor-mediated activation of the prostacyclin (IP) receptor (Sridharan et al. 2010A). The identity of this second ATP conduit is under active investigation.

A critical requirement for ATP release from erythrocytes is an increase in cAMP. Levels of cAMP in erythrocytes, as in all cells, are determined by its production by adenylyl cyclases (ACs) and hydrolysis by phosphodiesterases (PDEs). Since cAMP is a second messenger in multiple signaling pathways, the activity of PDEs localized to an individual pathway plays a key role in maintaining discrete responses (Adderley 2010). Erythrocytes possess isoforms of three PDEs that hydrolyze cAMP (PDEs 2, 3 and 4). PDE3 has been shown to actively regulate increases in cAMP associated with the signal transduction pathway that mediates low O2-induced ATP release (Hanson et al. 2010).

Defects in low O2-induced ATP release from erythrocytes and vascular disease

If erythrocyte-derived ATP is an important regulator of the distribution of perfusion to meet metabolic need in skeletal muscle then a defect in its release could contribute to microvascular dysfunction. Understanding of the signal transduction pathways for ATP release from erythrocytes provides insights into previously unrecognized factors which could contribute to the development of peripheral vascular disease and provides new therapeutic approaches to its treatment and/or prevention.

As noted above, activation of the heterotrimeric G protein, Gi, is required for low O2-induced ATP release from human erythrocytes (Olearczyk et al. 2004). We have found that, in erythrocytes of humans with type 2 diabetes (DM2), expression of one isoform of Giα, Giα2, is selectively reduced. This defect is associated with decreased ATP release from DM2 erythrocytes in response to both pharmacological activation of Gi protein with mastoparan 7 (MAS7) (Sprague et al. 2006) and, more importantly, exposure to reduced O2 tension (Sprague et al. 2010). The functional significance of this defect in erythrocyte signaling is revealed by studies in which isolated skeletal muscle arterioles were perfused with buffer or buffer containing either healthy human or DM2 erythrocytes (Sprague et al. 2010). When perfused with buffer containing healthy human erythrocytes, skeletal muscle arterioles dilated when extraluminal O2 tension was reduced, as would occur when O2 demand exceeds supply in that tissue. In contrast, the same vessel did not dilate in response to this physiological stimulus when perfused with buffer alone or buffer containing DM2 erythrocytes. These findings suggest that the inability of DM2 erythrocytes to release ATP in response to exposure to low O2 could contribute to the observed skeletal muscle microvascular dysfunction in this human condition.

Although most studies of the vascular disease of DM2 focus on the period after the development of pathological hyperglycemia, it is now recognized that vascular disease is present in the pre-diabetic period that is characterized by insulin resistance. That is, glucose is only minimally increased, but insulin levels are markedly elevated. Erythrocytes possess insulin receptors as well as components of well characterized insulin signaling pathways (Hanson et al. 2010). In adipocytes, binding of insulin with its receptor activates PDE3, the same PDE family associated with regulation of increases in cAMP required for low O2-induced ATP release from erythrocytes (Shakur et al. 2001). Recently it was shown that insulin attenuates low O2-induced ATP release from healthy human erythrocytes and that this action is mediated by activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase and, subsequently, PDE3 (Hanson et al., 2010). In addition, when isolated arterioles were perfused with erythrocytes incubated with insulin at concentrations found in pre-diabetes (1 nM), these vessels failed to dilate in response to reduced extraluminal O2, an effect which could not be explained by a direct action of insulin on the microvessels (Hanson et al. 2009).

Further support for an adverse effect of elevated insulin levels on microvascular function was demonstrated using in vivo video microscopy of the skeletal muscle microvasculature of 7-week Zucker diabetic fatty rats (ZDF), a well characterized animal model of pre-diabetes (Ellis et al. 2010). In these studies O2 supply to capillaries was reduced compared with their controls due to a lower O2 supply rate per capillary and higher O2 extraction resulting in a decreased O2 saturation at the venous end of the capillary network. These results suggest a lower average tissue PO2 in the pre-diabetic animals, a result supported by computational modeling studies. Together these results support a new and previously unrecognized role for insulin in the microvascular pathophysiology of pre-diabetes.

The erythrocyte as a therapeutic target in the treatment of DM2 and pre-diabetes

If impaired release of ATP from erythrocytes contributes to impaired skeletal muscle perfusion in diabetes and pre-diabetes, can the ability to release ATP in response to low O2 tension be rescued pharmacologically? The characterization of the complex signaling pathway for low O2-induced ATP release from erythrocytes suggests that intervention should be possible. Since increases in cAMP are required for ATP release from erythrocytes, one strategy for restoring or augmenting ATP release from erythrocytes would be to inhibit the PDE-mediated hydrolysis of this critical second messenger.

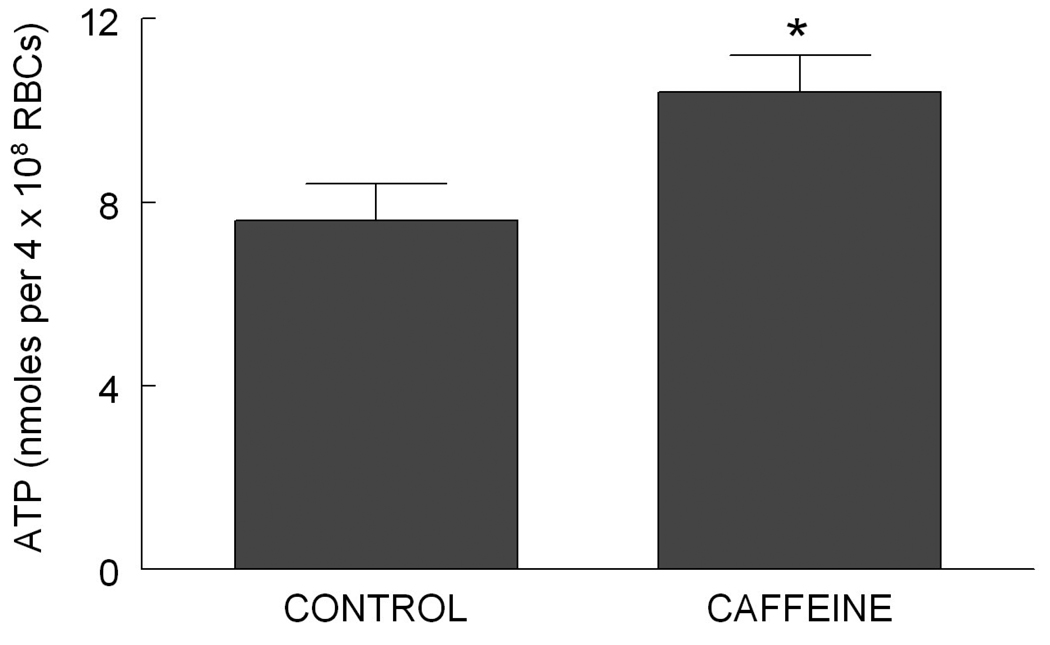

If targeting PDEs is a viable therapeutic approach, then a non-selective PDE inhibitor such as caffeine should augment ATP release from erythrocytes. Incubation of rabbit erythrocytes with 70 µM caffeine resulted in a significant increase in basal ATP release (Figure 2). Although these studies implicate PDE inhibitors as agents that could increase ATP release from human erythrocytes, caffeine does not target the specific PDE or the signaling pathway responsible for low O2-induced ATP release.

Figure 2.

Effect of caffeine (70 µM, n=17) on ATP release from isolated rabbit erythrocytes was determined as previously described (Ellsworth et al. 1995). Cells were collected from anesthetized and heparinized rabbits and centrifuged at 500 × g at 4 °C for 10 min under a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Saint Louis University. The plasma, buffy coat, and uppermost erythrocytes were removed by aspiration and discarded. The remaining erythrocytes were washed three times in buffer containing, in mM: 21.0 tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane, 4.7 KCl, 2.0 CaCl2, 140.5 NaCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 5.5 glucose, and 0.5% bovine albumin fraction V, final pH 7.4. Cells were prepared on the day of use. Values are the means ± SE. *, different from CONTROL (P<0.05).

As described previously, low O2-induced ATP release from human erythrocytes requires activation of the heterotrimeric G protein, Gi, and increases in cAMP (Olearczyk et al. 2004) (Figure 1). Increases in cAMP associated with exposure to low O2 are regulated by the activity of PDE3 (Hanson et al. 2009). Therefore, we utilized the PDE3-selective inhibitor, cilostazol, a drug used in the treatment of peripheral vascular disease in humans, in an attempt to augment increases in cAMP in response to direct activation of Gi with mastoparan 7 (MAS7). Although cilostazol is effective in relieving the symptoms of peripheral vascular disease, neither the mechanism of action of the drug nor its role in the treatment of the vascular disease of DM2 are fully understood. In studies using the non-selective PDE inhibitor, 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX, 100 µM), as well as cilostazol (10 and 100 µM) it was established that both agents produced increases in MAS7-induced cAMP levels in DM2 erythrocytes (Figure 3). Importantly, the selective PDE3 inhibitor, cilostazol, restored levels of cAMP in DM2 erythrocytes to values not different from those in healthy human erythrocytes (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of mastoparan 7 (MAS7, 10 µM) on cAMP levels in erythrocytes of healthy humans (open bars, n=9) and on erythrocytes of humans with type 2 diabetes (DM2, closed bars, n=12) was determined as previously described (Hanson et al. 2010). In some studies DM2 erythrocytes were preincubated with cilostazol (CILO) at a concentration of either 10 µM (n=7) or 100 µM (n=4) or 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX, 100 µM, n=7). Human erythrocytes were obtained by venipuncture, collected in a heparinized syringe and processed as described under Figure 2. The protocol for blood removal was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Saint Louis University. Values are the means ± SE. Different from respective CONTROL; * = P<0.05, † = P<0.01.

Since cilostazol increased intracellular cAMP levels in this pathway, it would be expected that this PDE3 inhibitor would also increase ATP release in response to activation of Gi. When DM2 erythrocytes were exposed to MAS7 in the presence of cilostazol (10 µM), ATP release from DM2 erythrocytes was potentiated (Figure 4). These findings suggest that use of an agent that inhibits PDE3 in humans with DM2 could rescue the capacity of erythrocytes to release ATP in response to low O2 tension which would restore the ability of these cells to participate in the matching of O2 delivery with demand in skeletal muscle.

Figure 4.

Effect of mastoparan 7 (MAS7, 10 µM) on ATP release from erythrocytes of humans with type 2 diabetes (DM2, n=4) in the presence and absence of pretreatment with cilostazol (CILO, 10 µM) was determined as previously described (Hanson et al. 2010). Human erythrocytes were obtained by venipuncture, collected in a heparinized syringe and processed as described under Figure 2. The protocol for blood removal was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Saint Louis University. Values are the means ± SE. Different from respective CONTROL; * = P<0.05, † = P<0.01.

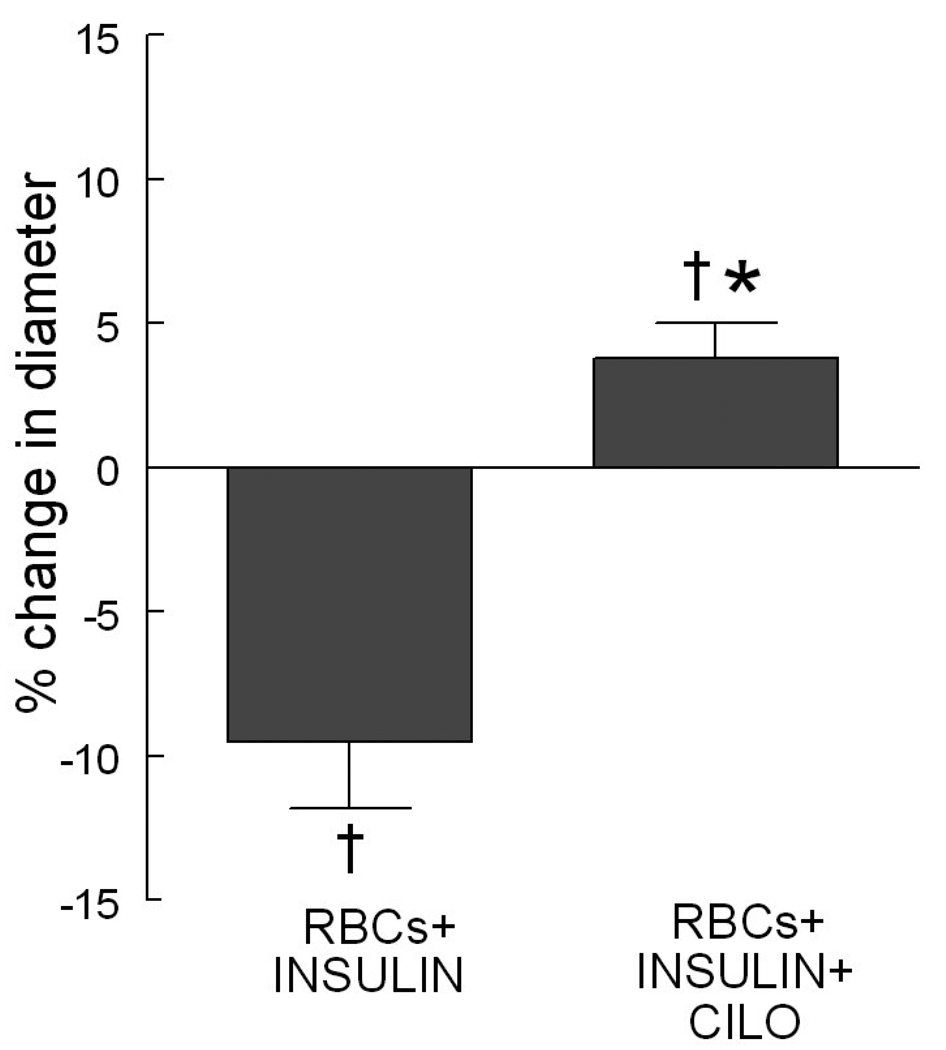

Although these studies with MAS7 suggest a beneficial role for PDE3 inhibitors in established DM2, both impaired ATP release and microvascular dysfunction are also present during the pre-diabetic period when blood glucose is ≤ 126 mg/dl but only at the expense of excessively high insulin levels. As reported previously, the ability of insulin to inhibit ATP release from erythrocytes is mediated via activation of PDE3. Therefore it would be anticipated that the PDE3 inhibitor, cilostazol, should likewise rescue the ability of insulin-treated erythrocytes to stimulate dilation of skeletal muscle resistance vessels exposed to reduced extraluminal O2. When isolated hamster skeletal muscle arterioles were perfused with buffer containing erythrocytes and insulin, decreases in extraluminal O2 did not stimulate vasodilation (Figure 5). In contrast, pre-treatment of the same erythrocytes with cilostazol (100 µM) prevented this adverse effect of insulin (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effect of cilostazol on the response of isolated arterioles to reduced extraluminal oxygen (O2) tension when perfused with buffer containing erythrocytes pre-incubated with insulin (1 nM, 30 min) was determined as previously described (Hanson et al. 2009). Arterioles (n=6) were exposed to either extraluminal normoxia (pO2=165±4 mm Hg) or reduced O2 tension (pO2 = 11±2 mm Hg) and perfused with buffer containing fully oxygenated erythrocytes treated with insulin in the absence and presence of cilostazol (CILO, 10 µM). Values are the means ± SE. * = different from RBCs treated with insulin in the absence of cilostazol (P< 0.05), †; different from respective normoxic control (P<0.05).

Summary and conclusions

Although August Krogh defined the necessity for the matching of O2 supply with demand in skeletal muscle over eighty years ago, the mechanisms that regulate this complex physiological process have not been fully elucidated and remain under active investigation today. For such a regulatory system to be effective not only must there be a means to detect levels of tissue oxygenation but this detector must be coupled to an affector which can appropriately alter microvascular perfusion (O2 delivery).

Here, we provide support for the hypothesis that the erythrocyte, long appreciated as a vital transporter of O2, must now be considered an active participant in regulation of local vascular resistance and, consequently, its own distribution within the skeletal muscle microcirculation. This mobile cell’s ability to release both O2 and ATP when exposed to reduced tissue O2 tension is a key component of the mechanism that regulates the matching of O2 supply with demand in skeletal muscle. Importantly, insights into the signaling mechanisms that culminate in ATP release from erythrocytes make this cell an intriguing therapeutic target for the development of new drugs to ameliorate perfusion defects in skeletal muscle associated with human diseases such as DM2 and pre-diabetes. Although we have come far from the original Krogh cylinder model of O2 delivery, it is clear that a great deal of work remains before we comprehend fully the complex and elegant mechanisms that are responsible for “regulating the conditions of supply [of oxygen]” in skeletal muscle.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank J.L. Sprague for inspiration. This work is supported by NIH grants HL-056249, HL-064180, HL-089094 and HL-089125 and ADA grant RA-133. The studies with caffeine were carried out by MaryAnn Chrzaszcz and Emily O’Keefe while undergraduates at Saint Louis University.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

There are no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Abraham EH, Prat AG, Gerweck L, Seneveratne T, Arceci RJ, Kramer R, Guidotti G, Cantiello HF. The multidrug resistance (mdr1) gene product functions as an ATP channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:312–316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.1.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adderley SP. Ph.D. Dissertation. Saint Louis University School of Medicine; 2010. Compartmentalized cAMP regulates receptor-mediated ATP release from erythrocytes. [Google Scholar]

- Bergfeld GR, Forrester T. Release of ATP from human erythrocytes in response to a brief period of hypoxia and hypercapnia. Cardiovasc Res. 1992;26:40–47. doi: 10.1093/cvr/26.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busse R, Trogisch G, Bassenge E. The role of endothelium in the control of vascular tone. Basic Res Cardiol. 1985;80:475–490. doi: 10.1007/BF01907912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins DM, McCullough WT, Ellsworth ML. Conducted vascular responses: Communication across the capillary bed. Microvasc. Res. 1998;56:43–53. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1998.2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich HH. Effect of locally applied epinephrine and norepinephrine on blood flow and diameter in capillaries of rat mesentery. Microvasc Res. 1989;38:125–135. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(89)90021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich HH, Kajita Y, Dacey RG., Jr Local and conducted vasomotor responses in isolated rat cerebral arterioles. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H1109–H1116. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.3.H1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich HH, Ellsworth ML, Sprague RS, Dacey RG., Jr Red blood cell regulation of microvascular tone through adenosine triphosphate. Am J Physiol. 2000;278:H1294–H1298. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.4.H1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich HH, Tyml K. Capillary as a communicating medium in the microvasculature. Microvasc Res. 1992;43:87–99. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(92)90008-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duling B. Oxygen sensitivity of vascular smooth muscle. II. In vivo studies. Am J Physiol. 1974;227(1):42–49. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1974.227.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis CG, Goldman D, Hanson M, Stephenson AH, Milkovich S, Benlamri A, Ellsworth ML, Sprague RS. Defects in oxygen supply to skeletal muscle of prediabetic ZDF rats. Am J Physiol. 2010;298:H1661–H1670. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01239.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellsworth ML. The red blood cell as an oxygen sensor: what is the evidence? Acta Physiol Scand. 2000;168:551–559. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201x.2000.00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellsworth ML, Ellis CG, Goldman D, Stephenson AH, Dietrich HH, Sprague RS. Erythrocytes: oxygen sensors and modulators of vascular tone. Physiology (Bethesda) 2009;24:107–116. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00038.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellsworth ML, Ellis CG, Popel AS, Pittman RN. Role of microvessels in oxygen supply to tissue. NIPS. 1994;9:119–123. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.1994.9.3.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellsworth ML, Forrester T, Ellis CG, Dietrich HH. The erythrocyte as a regulator of vascular tone. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:H2155–H2161. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.6.H2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellsworth ML, Pittman RN. Arterioles supply oxygen to capillaries by diffusion as well as by convection. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:H1240–H1243. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.258.4.H1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furchgott RF, Zawadzki JV. The obligatory role of endothelial cells in the relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by acetylcholine. Nature. 1980;288:373–376. doi: 10.1038/288373a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudi SR, Clark CB, Frangos JA. Fluid flow rapidly activates G proteins in human endothelial cells. Involvement of G proteins in mechanochemical signal transduction. Circ Res. 1996;79:834–839. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.4.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudi SR, Lee AA, Clark CB, Frangos JA. Equibiaxial strain and strain rate stimulate early activation of G proteins in cardiac fibroblasts. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:C1424–C1428. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.5.C1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson MS, Ellsworth ML, Achilleus D, Stephenson AH, Bowles EA, Sridharan M, Adderley S, Sprague RS. Insulin Inhibits Low Oxygen-Induced ATP Release from Human Erythrocytes: Implication for Vascular Control. Microcirculation. 2009;16(5):424–433. doi: 10.1080/10739680902855218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson MS, Stephenson AH, Bowles EA, Sprague RS. Insulin inhibits human erythrocyte cAMP accumulation and ATP release: role of phosphodiesterase 3 and phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Exp Biol Med. 2010;235:256–262. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2009.009206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hester RL. Uptake of metabolites by postcapillary venules: mechanism for the control of arteriolar diameter. Microvasc Res. 1993;46:254–261. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1993.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenberg M. Effect of oxygen on growth of cultured myocardial cells. Circ Res. 1971;28:148–157. doi: 10.1161/01.res.28.2.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson WF. Arteriolar oxygen reactivity: where is the sensor? Am J Physiol. 1987;253(22):H1120–H1126. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.253.5.H1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagger JE, Bateman RM, Ellsworth ML, Ellis CG. Role of erythrocyte in regulating local O2 delivery mediated by hemoglobin oxygenation. Am J Physiol. 2001;280:H2833–H2839. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.6.H2833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh A. The number and distribution of capillaries in muscles with calculations of the oxygen pressure head necessary for supplying tissue. J Physiol. 1919;52:409–415. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1919.sp001839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh A. The Anatomy and Physiology of Capillaries. NY: Hafner Publishing Co., Inc; 1959. Lecture II: The distribution and number of capillaries in selected organs; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Kurjiaka DT, Segal SS. Conducted vasodilation elevates flow in arteriole networks of hamster striated muscle. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:H1723–H1728. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.5.H1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HT, Toychiev AH, Takahashi N, Sabirov RZ, Okada Y. Maxi-anion channel as a candidate pathway for osmosensitive ATP release from mouse astrocytes in primary culture. Cell Res. 2008;18:558–565. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locovei S, Bao L, Dahl G. Pannexin 1 in erythrocytes: function without a gap. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(20):7655–7659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601037103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough WT, Collins DM, Ellsworth ML. Arteriolar responses to extracellular ATP in striated muscle. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:H1886–H1891. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.4.H1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada SF, O'Neal WK, Huang P, Nicholas RA, Ostrowski LE, Craigen WJ, Lazarowski ER, Boucher RC. Voltage-dependent anion channel-1 (VDAC-1) contributes to ATP release and cell volume regulation in murine cells. J Gen Physiol. 2004;124:513–526. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olearczyk JJ, Stephenson AH, Lonigro AJ, Sprague RS. Heterotrimeric G protein Gi is involved in a signal transduction pathway for ATP release from erythrocytes. Am J Physiol. 2004;286:H940–H945. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00677.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittman RN, Duling BR. Oxygen sensitivity of vascular smooth muscle. Microvasc Res. 1973;6:202–211. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(73)90020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal SS, Damon DN, Duling BR. Propagation of vasomotor responses coordinates arteriolar resistances. Am J Physiol. 1989;256:H832–H837. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.256.3.H832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal SS, Duling BR. Conduction of vasomotor responses in arterioles: a role for cell-to-cell coupling? Am J Physiol. 1989;256:H838–H845. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.256.3.H838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scemes E, Suadicani SO, Dahl G, Spray DC. Connexin and pannexin mediated cell-cell communication. Neuron Glia Biol. 2007;3:199–208. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X08000069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakur Y, Holst LS, Landstrom TR, Movsesian M, Degerman E, Manganiello V. Regulation and function of the cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase (PDE3) gene family. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2001;66:241–277. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(00)66031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague RS, Ellsworth ML, Stephenson AH, Kleinhenz M, Lonigro A. Deformation-induced ATP release from red blood cells requires cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator activity. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:H1726–H1732. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.5.H1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague RS, Ellsworth ML, Stephenson AH, Lonigro AJ. Participation of cAMP in a signal-transduction pathway relating erythrocyte deformation to ATP release. Am J Physiol. 2001;281:C1158–C1164. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.4.C1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague RS, Hanson MS, Achilleus D, Bowles EA, Stephenson AH, Sridharan M, Adderley S, Procknow J, Ellsworth ML. Rabbit erythrocytes release ATP and dilate skeletal muscle arterioles in the presence of reduced oxygen tension. Pharmacol Rep. 2009;61:183–190. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(09)70020-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague RS, Stephenson AH, Bowles EA, Stumpf MS, Lonigro AJ. Reduced expression of Gi in erythrocytes of humans with type 2 diabetes is associated with impairment of both cAMP generation and ATP release. Diabetes. 2006;55:33588–33593. doi: 10.2337/db06-0555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague RS, Stephenson AH, Ellsworth ML. Red not dead: signaling in and from erythrocytes. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2007;18(9):350–355. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sridharan M, Adderley SP, Bowles EA, Egan TM, Stephenson AH, Ellsworth ML, Sprague RS. Pannexin 1 is the conduit for low oxygen tension-induced ATP release from human erythrocytes. Am J Physiol. 2010 doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00301.2010. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sridharan M, Sprague RS, Adderley SP, Bowles EA, Ellsworth ML, Stephenson AH. Diamide decreases deformability of rabbit erythrocytes and attenuates low oxygen tension-induced ATP release. Exp Biol Med. 2010 doi: 10.1258/ebm.2010.010118. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein JC, Ellsworth ML. Capillary oxygen transport during severe hypoxia: role of hemoglobin oxygen affinity. J Appl Physiol. 1993;75:1601–1607. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.4.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhoutte PM, Lüscher TF, Gräser T. Endothelium-dependent contractions. Blood Vessels. 1991;28:74–83. doi: 10.1159/000158846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]