Abstract

Background

The three-dimensional saddle shape of the mitral annulus is well characterized in animals and humans, but the impact of annular nonplanarity on valve function or mechanics is poorly understood. In this study, we investigated the impact of the saddle shaped mitral annulus on the mechanics of the P2 segment of the posterior mitral leaflet.

Methods

Eight porcine mitral valves (n = 8) were studied in an in-vitro left heart simulator with an adjustable annulus that could be changed from flat to different degrees of saddle. Miniature markers were placed on the atrial face of the posterior leaflet, and leaflet strains at 0%, 10%, and 20% saddle were measured using dual-camera stereophotogrammetry. Averaged areal strain and the principal strain components are reported.

Results

Peak areal strain magnitude decreased significantly from flat to 20% saddle annulus, with a 78% reduction in the measured strain over the entire P2 region. In the radial direction (annulus free edge), a 44.4% reduction in strain was measured, whereas in the circumferential direction (commissure-commissure), a 34% reduction was measured from flat to 20% saddle.

Conclusions

Nonplanar shape of the mitral annulus significantly reduced the mechanical strains on the posterior leaflet during systolic valve closure. Reduction in strain in both the radial and circumferential directions may reduce loading on the suture lines and potentially improve repair durability, and also inhibit progression of valve degeneration in patients with myxomatous valve disease.

The three-dimensional nonplanar “saddle” shape of the mitral annulus was first reported by Levine and colleagues [1], in a geometric diagnosis of mitral valve prolapse. In subsequent investigations in healthy humans [2] and animals [3], dynamic changes in the annular shape during different cardiac phases were quantified, which showed systolic high points along the anterior-posterior plane and low points at the two commissures. Recently, using advanced imaging techniques, several investigators reported the loss of annular saddle shape in patients with ischemic mitral regurgitation [4], wherein the degree of annular flattening was governed by the infarct location [5, 6]. A renowned group also reported the degree of nonplanarity of different annuloplasty rings after implantation, using sonomicrometry [7]. Although these studies demonstrate an increasing interest in the mitral annular anatomy in health and disease, there are few studies that focused on understanding the importance of this anatomic characteristic on mitral valve function and mechanics.

In 2002, the Gorman laboratory [8] used a simplified mathematical model of the mitral valve to demonstrate that the saddle shape of the mitral annulus imparts better leaflet curvature during systolic closure and thus reduces leaflet stress. In subsequent studies from our laboratory, we used native porcine mitral valves with intact annular and subvalvular geometries to demonstrate that the mitral annular saddle indeed reduces the forces acting on the chordae tendineae and also the mechanical strains acting on the anterior leaflet [9, 10]. In this study, we extend our studies to the P2 cusp of the posterior mitral leaflet, as most mitral valve surgeries used today involve resection, reshaping, or placement of suture lines on the posterior leaflet.

Material and Methods

Valve Selection

Mitral valves with intact annular and subvalvular geometries (including the papillary muscles) were excised from fresh porcine hearts immediately upon slaughtering. Eight valves of size 28, measured using standard annuloplasty ring sizers from Edwards Lifesciences (Irvine, CA) were selected for this study and were preserved in cold saline solution.

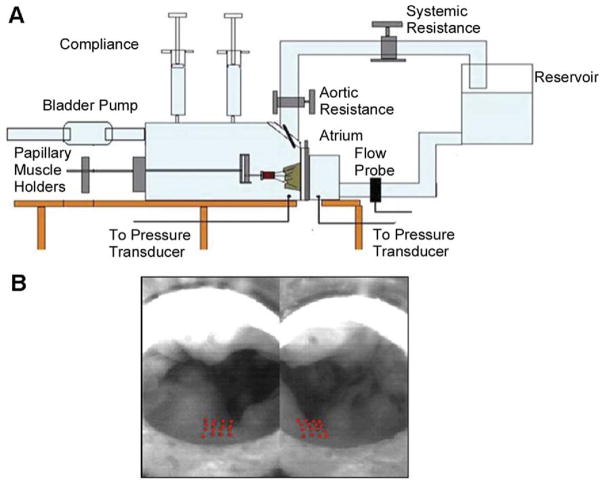

Experimental Set-Up

The Georgia Tech left heart simulator with a variable annular shape model was used for this study. This in-vitro simulator is well established and has been widely used to conduct several studies on mitral valve hemodynamics and mechanics [9, 10]. In brief, the simulator shown in Figure 1A has two rigid chambers representing the left atrium and the left ventricle. A mitral annulus plate with a silicone annulus, whose shape can be varied precisely from a flat to different levels of saddle, is placed in between the two chambers. The variable shape mitral annulus is made of a multilink chain wrapped in Dacron (Darlexx, Shawnut Mills, MA), and constrained at multiple locations along the perimeter of the annulus. Using a push-rod mechanism, the three-dimensional shape of this annulus can be adjusted to different levels while maintaining a constant annular perimeter. In this model, annular height to commissural width ratios (AHCWR) ratios from 0% (flat annulus) to as high as 30% AHCWR can be simulated. At high degrees of saddle, the annular perimeter was maintained constant by adjusting the septolateral dimension by ±1 mm, as reported previously [10].

Fig 1.

(A) Schematic of the in-vitro left heart simulator with a native porcine mitral valve. (B) Atrial view of the marker array on the P2 segment of the posterior leaflet.

The extracted porcine mitral valves were sutured onto the silicone annulus using 3-0 silk sutures in a continuous mattress format, ensuring that there were no gaps between the silicone annulus and the valve. The papillary muscles were covered in Dacron, and the muscles were mounted onto a geared fixture in the left ventricular chamber that allows displacement in three-dimensional space (apical, posterior, and lateral directions) [11]. Before mounting the valve into the loop, a 4 × 4 square array of 16 miniature markers (size approximately 200 μm) were placed on the atrial side of the P2 segment of the posterior leaflet using a black tissue dye (Shandon Tissue Marking Dye; Thermo Corp, Pittsburgh, PA) as shown in Figure 1B. A 0.9% saline solution was used as the working media, and pulsatile pressure and flow curves were generated using a compressible bladder pump connected to the left ventricle.

Leaflet Strain Measurement

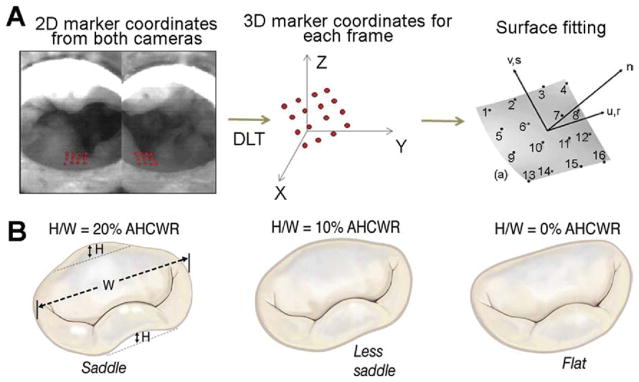

The array of markers on the P2 segment were imaged during the entire cardiac cycle under pulsatile conditions using two high-speed cameras (Basler 510K; Basler Corp, Exton, PA) with Nikon macro lenses (f2.8; Nikon, Melville, NY). The two cameras were synchronized with each other, and image acquisition was triggered at the beginning of systole, synchronized with the increase in the transmitral pressure gradient. The two cameras were separated by 30 degrees, and two-dimensional images of the marker array were obtained from the atrial window at a frame rate of 250 frames per second. This high frame rate allowed acquisition of 205 frames per cardiac cycle, of which 120 frames represent the period from when the valve begins to close, to complete closure, and till valve opening. At the camera angles used in this set-up, all the 16 markers were visible in these 120 frames and allowed high-resolution strain computations. The acquired images were stored to the hard drive in TIFF format at a 1,200 × 1,024 pixel resolution, and the two-dimensional coordinates of individual markers were obtained using a semiautomated MATLAB program and written to a text file. The three-dimensional coordinates of each marker were calculated from the digitized two-dimensional coordinates using a direct linear transformation with the reference coordinates obtained from a calibration cube, as shown in Figure 2. A surface was fit to the three-dimensional marker space using a biquintic finite element interpolation scheme that has an excellent fit with regions of high curvature, as validated in a previous study [13]. The areal strain, major and minor principal strains, and the principal angle, were calculated from the fitted surface using a C++ program.

Fig 2.

(A) Schematic of the methods to digitize the leaflet markers and three-dimensional reconstruction of the leaflet surface using direct linear transformation. (B) Degree of saddle defined as the ratio of annular height (H) to commissural width (W) ratio and the three degrees of saddle that were tested in this study.

Experimental Protocol

After mounting the mitral valve into the simulator, the mitral annular size and papillary muscle positions were adjusted to their physiologic positions. The physiologic papillary muscle positions were determined such that commissural chordae of the mitral valve were in a single apicobasal plane and parallel to each other, and the tips of the papillary muscles were in the circumferential plane passing perpendicularly through the coaptation line. The simulator was filled with 0.9% saline solution, and the valve was studied under adult physiologic hemodynamic conditions of 120 mm Hg peak transmitral pressure, 5 L/min cardiac output at a heart rate of 70 beats per minute. The systolic duration was 290 ms, with a total cycle time of 860 ms. The transmitral pressure was monitored and recorded in real-time using a differential pressure transducer (DP9-40; Validyne Engineering, Northridge, CA), and the mitral flow was recorded using an electromagnetic flow probe (600 Series; Braemar, MN). The data were monitored using a PCMCIA data acquisition card (DAQ-1200; National Instruments, Austin, TX) and recorded to the hard drive using a custom program DAQANAL (LABVIEW 8.0; National Instruments). The array of markers was imaged first with a flat annulus (0% AHCWR) and then by increasing the degree of annular saddle to 10% AHCWR and 20% AHCWR. As the degree of saddle increased and the commissural points on the annulus were moved apically, the papillary muscles were also moved apically by the same distance [10], to maintain a constant distance between the mitral annulus plane and the tips of the papillary muscles, and prevent chordal slackness. The lateral and posterior positions of the papillary muscles were held constant throughout the experiment.

Data Analysis

All the data are reported as mean ± 1 SD. Percentage differences in the strain measures between different levels of saddle were calculated with the flat annulus configuration as the reference. Normality of the data was tested using an Anderson-Darling test, and a one-way analysis of variance model was used to test the effect of degree of saddle on leaflet strains. The measured strains from different annular configurations were compared using a paired t test with a 95% confidence interval. The statistical analysis was conducted using MINITAB 15 (Minitab, State College, PA).

Results

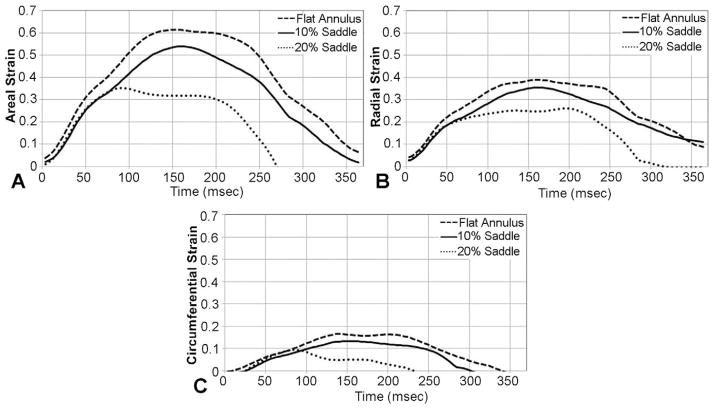

Strain Versus Time

Figure 3A illustrates the temporal changes in areal strain with a flat, 10%, and 20% saddle annulus, during systole. All valves experienced rapid strain rate during early systole, with subsequent peaking due to collagen locking at peak systolic closure, and finally rapid unloading from late systole to early diastole. A similar trend was seen in both the major and minor principal strains (Fig 3B,C), respectively, for all the valves. The total time of leaflet deformation, namely, the duration during which the leaflet deformed from the reference state to a peak and then returned to the reference state, was significantly different between the three annular shapes. With a flat annulus (0% AHCWR), the total deformation time was significantly larger at 389 ± 10 ms, compared with 360 ± 9 ms for 10% saddle and 273 ± 11 ms for 20% saddle.

Fig 3.

(A) Temporal changes in the areal strain for the three annular shapes. (B) Variations in the circumferential strain. (C) Variations in the radial strain.

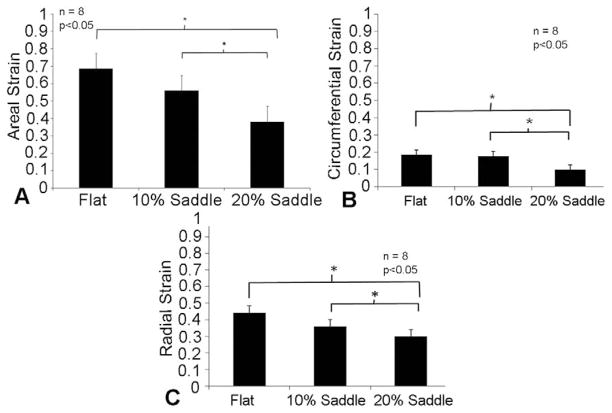

Peak Areal Strain Magnitude

The peak magnitude of the areal strain was calculated for all the eight valves, and the averaged magnitudes are reported (Fig 4A). Areal strain magnitudes significantly reduced from 0.68 ± 0.1 for a flat annulus, to 0.57 ± 0.1 for a 10% AHCWR annular shape (p = 0.03) and to 0.38 ± 0.09 for a 20% AHCWR annular shape (p = 0.005).

Fig 4.

(A) Peak areal stretch magnitudes with varying degrees of annular nonplanarity. (B and C) Changes in peak circumferential and radial strain magnitudes with variation in annular shape.

Radial and Circumferential Strains

Similar reduction was observed in peak strains both in the circumferential (commissure-commissure direction) and radial (free edge to annulus) directions. In the circumferential direction, the peak systolic strain did not change, from 0.18 ± 0.07 at 0% AHCWR to 0.17 ± 0.08 at 10% AHCWR (p = 0.816), but was significantly reduced to 0.10 ± 0.08 at 20% AHCWR (p = 0.01), as shown in Figure 4B. Similarly, in the radial direction, there was no significant change in the peak strain magnitude, from 0.44 ± 0.13 at 0% AHCWR to 0.35 ± 0.12 for 10% saddle (p = 0.196), but was reduced significantly to 0.29 ± 0.08 at 20% saddle (p = 0.031), as shown in Figure 4C.

Principal Angle

Principal angle was measured as the angle between the geometric axis of the leaflet and the principal strain vectors, at each time point in the cardiac cycle. This is a measure of the shear strain in the leaflets, because if the shear strain in leaflets is minimal, the principal angle is low and vice versa. In this study, the peak principal angles over the entire cardiac cycle were nearly equal for the flat (0.91 ± 0.60), 10% saddle (−0.38 ± 0.56), and 20% saddle (0.02 ± 1.11), indicating minimal shear strain in the leaflets during systolic valve closure.

Comment

Mitral annular motion and geometric changes have been of immense interest to cardiologists and cardiac surgeons, and repair strategies today are increasingly focusing on restoring the physiologic shape of the mitral annulus. The seminal study by Levine and coworkers [1] triggered great enthusiasm to characterize the sphincteric motion and geometric changes of the annular shape and size throughout the cardiac cycle, which is already accomplished in animals and humans in health and disease [2, 4]. However, the clinical relevance of this knowledge has not been realized owing to the lack of insights into the role of the mitral annular saddle on valve function and mechanics. In the past 5 years, few studies have reported a potential impact of the mitral annular saddle on leaflet curvature and mechanical strains on the anterior leaflet [8, 10, 12]. These studies laid the foundation for the importance of mitral annular saddle, and in this paper, we extend our studies to the posterior mitral leaflet, which is often the leaflet that is surgically repaired.

Data from this study demonstrate an inverse correlation between the degree of nonplanarity of the mitral annulus and the systolic mechanical strain on the P2 segment of the posterior mitral leaflet. As the mitral annular nonplanarity increased from 0% to 10% to 20% AHCWR, the peak areal strains reduced significantly. In comparison with the flat annulus (0% AHCWR), a 19.2% and 44.1% reduction in the peak areal strains were measured at 10% and 20% AHCWR, respectively. A similar trend was measured both in the circumferential and radial directions as well. In the radial direction (from annulus to free edge), the peak strains reduced by 5.5% with a 10% AHCWR and by 44.4% with a 20% AHCWR in comparison to the flat annulus at 0% AHCWR. Similarly, in the circumferential direction (along the leaflet, parallel to the annulus), reductions of 20.5% with 10% saddle and 34% with 20% saddle were measured.

The results from this study demonstrate that the saddle-shaped mitral annulus provides a mechanical benefit to the valve through a reduction in the leaflet strains. We speculate that the saddle shape of the annulus during systole optimizes force distribution among various mitral valve components, resulting in a minimal energy conformation of the valve. In a previous study from our group, Jimenez and colleagues [9] reported that mitral annular saddle optimizes chordal force balance by redistributing the forces between the anterior and posterior leaflets, compared with a flat annulus in which the forces are concentrated on the anterior leaflet. The forces in the commissural chordae reduced by 35% from a flat to 20% saddle annulus, which may have imparted better leaflet motion (as seen in Fig 3) and curvature during systole. Results from ongoing experiments in our laboratory demonstrate better systolic leaflet coaptation at the P1, P2, and P3 segments with improved leaflet curvature during peak systolic closure, which was demonstrated in animal studies (Jensen et al. Saddle-shaped mitral valve annuloplasty rings improve leaflet coaptation geometry. Presented at American Heart Association Scientific Sessions, 2007, abstract 14824). The temporal changes in the systolic strains on the P2 segment as recorded in this study show a distinct difference in the total time of leaflet deformation (time taken by the leaflet to deform back to the reference state) among the three annular shapes. These results encourage us to think that, even though increase in mitral leaflet curvature is a visible endpoint of the annular saddle [8], a subvalvular force redistribution is involved [9].

Although the complete story of the mitral annular saddle is yet to be explained, the results from this study have important implications for current practices in mitral valve reparative therapies. Typically, all degenerative mitral valve repairs involve resection of leaflet tissue and use of sutures to reconstruct the diseased leaflet. The results from this study indicate that restoring the physiologic saddle shape or allowing native mitral annular dynamics after the repair may reduce the forces on the suture lines and avoid suture dehiscence or tissue tearing at these regions. However, it should be noted that tissue tearing and suture dehiscence can also happen when excessive resection is adopted in fibroelastic deficient valves with acute chordal rupture only and no leaflet distension [14]. Additionally, the spatial heterogeneity in the leaflet ultrastructure and the differences in the composition of the tissue may play an important role in suture dehiscence, and thus the physiologic and pathologic characteristics of valve leaflets should be better understood.

From a biological perspective, reducing the leaflet strains (as shown in Fig 5) may decelerate the progression of leaflet degeneration after mitral valve surgery. Pedersen and coworkers [15] recently reported that, in canine mitral valves, strain magnitude correlated with overexpression of endothelin-1 receptors, which are the key drivers of valve degeneration. Hence, if surgically restoring the saddle shape of the mitral annulus has the ability to reduce leaflet strains, it may potentially inhibit valve degeneration to some extent. However, at this point, we are unable to comment more on this topic owing to lack of human data that replicate the results published for canine mitral valves [15].

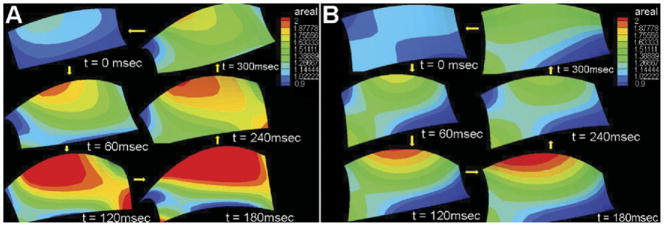

Fig 5.

The fitted quadratic C0 Lagrangian finite element surface showing the areal strain with (A) the flat annulus and (B) the 20% saddle annulus. The legend depicts the magnitudes of areal strain, and the surface plots show the reduction in the areal strain with increasing annular nonplanarity.

Although the in-vitro model adopted in this study simulates the physiologic function, hemodynamics, and mechanics of the normal mitral valve, it has some inherent limitations. Firstly, the mitral annulus has a dynamic sphincteric action that changes from a flat annulus during diastole to a saddle annulus during systole. In this study, we adopt a static saddle annulus that simulates only the systolic position; that, however, does not impact the outcomes of this study, as our focus is only on the systolic leaflet strains. Secondly, the mitral annulus also has an apical-basal motion, which was not simulated in this model. However, in a previous study from our group, we demonstrated that such apical-basal motion does not impact the function and mechanics of the valve as much as expected [16]. Finally, the rigid ventricular chamber used in this study does not mimic the ventricular motion, the effects of which on the valve function are not studied.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that the non-planar saddle shape of the mitral annulus reduces mechanical strains on the clinically important P2 segment of the posterior mitral leaflet. Current strategies for mitral valve repair should acknowledge these native valve mechanics, as they may have a potentially important role in increasing durability of degenerative mitral valve repairs.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Holifield Farms, Covington, Georgia, for donating the porcine hearts used in this study and Marcia Williams for designing the graphics used in this paper. This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health through R01 Grant 52009.

References

- 1.Levine RA, Triulzi MO, Harrigan P, et al. The relationship of mitral annular shape to the diagnosis of mitral valve prolapse. Circulation. 1987;75:756–67. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.75.4.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flachskampf FA, Chandra S, Gaddipatti A, et al. Analysis of shape and motion of the mitral annulus in subjects with and without cardiomyopathy by echocardiographic three-dimensional reconstruction. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2000;13:277–87. doi: 10.1067/mje.2000.103878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tibayan FA, Rodriguez F, Zasio MK, et al. Geometric distortions of the mitral valvular-ventricular complex in chronic ischemic mitral regurgitation. Circulation. 2003;108(Suppl 1):II116–21. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000087940.17524.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmad RM, Gillinov AM, McCarthy PM, et al. Annular geometry and motion in human ischemic mitral regurgitation: novel assessment with three-dimensional echocardiography and computer reconstruction. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:2063–8. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorman JH, Jackson BM, Enomoto Y, et al. The effect of regional ischemia on mitral valve annular saddle shape. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:544–8. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(03)01354-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watanabe N, Ogasawara Y, Yamaura Y, et al. Mitral annulus flattens in ischemic mitral regurgitation. Geometric differences between inferior and anterior myocardial infarction: a real time 3-dimensional echocardiographic study. Circulation. 2005;112(Suppl):I458–62. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.524595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Timek TA, Glasson JR, Lai DT, et al. Annular height to commissural width ratio of annuloplasty rings in-vivo. Circulation. 2005;112(Suppl):I423–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.525485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salgo IS, Gormn JH, Gorman RC, et al. Effect of annular shape on leaflet curvature in reducing mitral leaflet stress. Circulation. 2002;106:711–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000025426.39426.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jimenez JH, Soerensen DD, He Z, et al. Effects of a saddle shaped annulus on mitral valve function and chordal force distribution: an in vitro study. Ann Biomed Eng. 2003;31:1171–81. doi: 10.1114/1.1616929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jimenez JH, Liou SW, Padala M, et al. A saddle shaped annulus reduces systolic strain on the central region of the mitral valve anterior leaflet. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;134:1562–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jimenez JH, Soerensen DD, He Z, et al. Effects of papillary muscle position on chordal force distribution: an in-vitro study. J Heart Valve Dis. 2005;14:295–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sacks MS, Enomoto Y, Graybill JR, et al. In-vivo dynamic deformation of the mitral valve anterior leaflet. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:1369–77. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.03.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith DB, Sacks MS, Vorp DA, et al. Surface geometric analysis of anatomic structures using biquintic finite element interpolation. Ann Biomed Eng. 2000;28:598–611. doi: 10.1114/1.1306342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adams DH, Anyanwu AC. Seeking a higher standard for degenerative mitral valve repair: begin with etiology. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;136:551–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pedersen LG, Zhao J, Yang J, et al. Increased expression of endothelin-B receptor in static stretch exposed porcine mitral valve leaflets. Res Vet Sci. 2007;82:232–8. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jimenez JH, Soerensen DD, He Z, et al. Mitral valve function and chordal force distribution using a flexible annulus model. Ann Biomed Eng. 2005;33:557–66. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-1512-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]