Abstract

Retinal neuron degeneration and survival are often regulated by the same trophic factors that are required for embryonic development and are usually expressed in multiple cell-types. Therefore, the conditional gene targeting approach is necessary to investigate the cell-specific function of widely expressed and developmentally regulated genes in retinal degeneration. The discussion in this review will be focused on the use of Cre/lox-based conditional gene targeting approach in mechanistic studies for retinal degeneration. In addition to the basic experimental designs, this article addresses various factors influencing the outcomes of conditional gene targeting studies, limitations of current technologies, availability of Cre-drive lines for various retinal cells, and issues related to the generation of Cre-expressing mice. Finally, this review will update the current status on the use of Cre/lox-based gene targeting approach in mechanistic studies for retinal degeneration, which includes rod photoreceptor survival under photo-oxidative stress and protein trafficking in photoreceptors.

1. Introduction

The use of gene targeting with homologous recombination in murine embryonic stem (ES) cells has led to many mechanistic insights about human diseases. However, global gene disruption has two major limitations that may prevent the identification of gene function in a target tissue or in adults. First, disruption of essential genes often causes embryonic or early postnatal lethality [1]. Second, disruption of a ubiquitously expressed gene may not yield mechanistic insights regarding the function of a protein of interest in a particular cell type [2, 3]. In these scenarios, temporal or/and spatial gene disruption is far more advantageous. The seminal work on the utilization of bacteriophage P1 site-specific recombination system in mammals by Dr. Brian Sauer and his coworkers [4, 5] established a firm foundation for the Cre/lox-based gene targeting, which is the most widely used conditional gene targeting approach to date.

Cre recombinase is a 38 kDa protein and belongs to the integrase family of recombinases [6]. Biochemically Cre catalyzes site-specific DNA recombination, both intra- and intermolecularly, between the 34 base pair loxP sites [7]. Cre carries a eukaryotic nuclear targeting sequence [8] and is efficient in performing site-specific DNA recombination in mammals [9]. Therefore, Cre/lox system has become the primary choice for the site-specific DNA recombination-based manipulation of the mouse genome. Efficient Cre-mediated excision of DNA between directly repeated loxP sites has been widely used in gene activation and deletion of small or large segment of chromosomal DNA [9–11]. Cre-mediated recombination also permits the translocation of large DNA fragments on chromosomes [12] and integration (knock-in) or replacement of a gene or DNA segment [13–15]. Conditional gene knockout is by far the most widely used application of Cre-mediated site-specific recombination [16]. The use of this strategy in retinal degeneration studies will be the focus of this paper. In addition to the general strategy of Cre/lox gene targeting, this review will address various factors influencing the outcomes of conditional gene targeting studies, limitations of current technologies, availability of Cre-drive lines for various retinal cells, and issues related to the generation of Cre-drive lines. Finally, this paper will update the current status on the use of Cre/lox-based gene targeting approach in mechanistic studies for retinal degeneration, including the two most advanced areas, rod photoreceptor survival under photo-oxidative stress and protein trafficking in photoreceptors.

2. Strategy in Experimental Design

2.1. Basic Scheme of Experimental Design

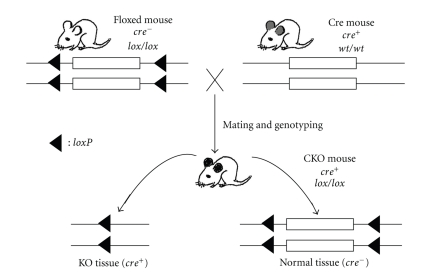

Cre/lox conditional gene targeting requires a mouse that has been pre-engineered with a loxP-flanked gene (or gene segment), generated with homologous recombination in murine ES cells (Figure 1). As the loxP sites are placed in introns, this engineered mouse is phenotypically wild type. A conditional gene knockout mouse is generated by breeding this mouse with a mouse that expresses Cre under the control of a tissue-specific promoter for two generations (Figure 1). In the conditional gene knockout mouse, the loxP-flanked gene is removed in a tissue-specific fashion. Only cells/tissues that express Cre carry the deleted gene, and thus they are phenotypically mutants (Figure 1). In this way, one can analyze the gene function in Cre-expressing tissues without affecting the gene expression in nontargeted tissues.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of generating a conditional knockout (CKO) mouse from breeding a tissue-specific Cre mouse (top right) with a mouse carrying homozygous floxed gene (top left). A CKO mouse carrying a homozygous floxed gene and cre (either heterozygous or homozygous) is obtained by genotyping the F2 offspring. Tissue-specific Cre expression is shown as grey-eared (top right). Tissue-specific gene KO is diagramed as black-eared (bottom).

2.2. Considerations in Experimental Design

One concern regarding the use of conditional gene targeting in vivo is that the Cre-mediated excisive recombination is usually not 100 percent. Therefore, the effect of gene disruption may not be observed. It is important to understand that there is a fundamental difference between Cre-mediated gene disruption and conventional gene knockdown. As only four Cre molecules are required for a productive Cre-mediated recombination [7], Cre-mediated gene disruption occurs usually in an all-or-none fashion in a particular cell. A most likely scenario for a 20 percent efficiency of Cre-mediated recombination is that approximately 20 percent of targeted cells have 100 percent gene knockout. This is completely different from 20 percent gene knockdown in all cells. This characteristic has made Cre/lox-based gene targeting a useful approach in gene function analysis, even though it is rare that transgenic Cre mice express the recombinase in all targeted cells/tissues. Since most gene function studies are targeting the effect of gene inside the cells, a fraction of targeted cells with gene deletion could produce stable phenotypic changes in animals [44, 45]. However, in a scenario that no phenotypic change is observed in animals that have a small portion of targeted cells carrying Cre-mediated gene disruption, the interpretation of data needs to be cautious.

Another misconception in designing conditional gene targeting studies is that a complete Cre-mediated excision is more desirable. This is not always true, particularly, in a situation that Cre may have toxic effect to the cells or phenotypic changes are too strong to be characterized. In a previous study, we intentionally used a rod-expressing Cre line with a lower efficiency of Cre-mediated recombination to avoid unnecessary complication derived from potential Cre toxicity in rods [44], as observed by others [21]. In a scenario that conditional gene targeting results in a massive or/and rapid phenotypic change that hampers the understanding of the biology and diseases, a lower level of Cre expression in targeted tissues/cells may produce a genetic mosaic that attenuates the development of pathological changes in animal models [46].

3. Cre-Drive Lines

3.1. Available Cre-Drive Lines

Although Cre can be exogenously delivered to a targeted tissue, it is usually expressed under the control of tissue/cell specific promoters. A critical factor for a successful conditional gene inactivation study is the availability of a suitable Cre-expressing drive line. Table 1 includes a list of published Cre-expressing drive lines for various retinal cells. Since most retinal degeneration studies are related to the photoreceptors and RPE, all published rod-, cone-, and RPE-expressing Cre mouse lines are listed in Table 1. Retinal Müller glia is the major supporting cell and plays a critically role in maintaining structural and functional integrity in the retina under stress conditions. As most Cre-drive lines for Müller glia were usually developed for brain and Cre expression occurred outside ocular tissues in these mice, Table 1 only lists a few that either have been characterized more thoroughly or have been shown to be successful in conditional gene targeting in the retina [3, 47, 48]. Degeneration of retinal ganglion cells (GCs) is becoming a focused research area for their role in glaucoma and for the relevance to the safety of treating AMD patient with anti-VEGF strategies [49]. A number of characterized GC-expressing Cre-drive lines are thus listed in Table 1. While inner nuclear layer (INL) neurons are not often investigated for retinal degeneration, they are retinal neurons. The Cre-drive lines for INL neurons can be used for studies related to retinal neurobiology and are listed in Table 1. Finally, Cre-drive lines that are expressed in almost all retinal neurons are also listed in Table 1. It is worth noting that some of the listed Cre-expressing mouse lines were originally designed to trace cell lineage and had strong developmental Cre expression. These Cre lines may not be suitable for retinal degeneration studies. Although some promoters employed for Cre expression are useful in circumventing embryonic lethality, due to their ubiquitous expression they cannot be utilized to study a tissue/cell type-specific gene function.

Table 1.

Published potentially useful Cre-drive lines in designing studies related to retinal degeneration.

| Major targeted cells | Minor/other expression | Promoter | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Photoreceptors | |||

| M- and S-cone | Not reported | hRgp | [17] |

| M-cone | Not reported | mMo | [18] |

| S-cone | Not reported | mSo | [18] |

| Rod | Rod bipolar | mRho | [19] |

| Rod | Not reported | Irbp | [20] |

| Rod | Not reported | hRho | [21, 22] |

| RPE | |||

| *RPE | Optic nerve | hVmd2 | [23] |

| *RPE | Müller cells/optic nerve/INL | hVmd2 | [24] |

| RPE | Pigmented cells | Dct | [25] |

| RPE | Neural retina | Trp1 | [26] |

| RPE | Lens/neural retina | Modified αA-crystallin | [27] |

| Müller glia | |||

| #Müller cells | GC and ONL | Pdgfra | [28] |

| *Müller cells | INL | hVmd2 | [24, 29] |

| !#Müller cells | Brain | Glast | [30] |

| Müller cells | INL/Brain | Thy1 | [31, 32] |

| Müller cells | Brain | Foxg1 | [31] |

| Ganglion cells | |||

| GC | Brain | Grik4 | [31] |

| Melanopsin-expressing GC | Not reported | Opn4 | [33] |

| $ GC | Amacrine and horizontal cells | Math5 | [34] |

| GC/neural retina | Brain | Thy1.2 | [35] |

| GC/Amacrine cells | Brain | Chat-(BAC transgenic) | [31, 36] |

| Inner nuclear layer neurons | |||

| $Amacrine cells | Not reported | Chat-(knockin-Jackson Lab) | [31] |

| Bipolar cells | photoreceptor/Brain | Pcp2 | [37] |

| #Rod bipolar cells | Brain | Pcp2 | [38] |

| $Amacrine and horizontal cells | Not reported | Ptf1a | [39] |

| Neural retina | |||

| #All retinal neurons | Not reported | Chx10 | [40] |

| !All retinal neurons | Brain | PrP | [41] |

| Neural retina | Brian/multiple tissues | Six3 | [42] |

| #All retinal neurons | Not reported | Dkk3 | [43] |

*Expression with a tetracycline-inducible approach. !Expression with a tamoxifen-inducible approach. #Expression with BAC transgenic approach. $Expression with knock-in approach. Abbreviations: Chat: choline acetyl transferase Dct: dopachrome tautomerase Dkk3: Dickkopf family protein 3 Foxg1: Forkhead box G1, Glast: glutamate/aspartate transporter, Grik4: glutamate receptor, ionotropic kainate 4 precursor, hRgp: human red/green pigment, Math5: murine atonal homolog 5, mRho: mouse rhodopsin, mMo: mouse M-opsin, mSo: Mouse S-opsin, Opn4: melanopsin, Pcp2: purkinje cell protein 2, Pdgfra: platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α, PrP: Prion protein, Ptf1a: pancreas specific transcription factor 1a, Six3: six/sine oculis subclass of homeobox gene, Thy1.2: Thymus cell antigen 1.2, and Trp1: tyrosinase-related protein.

3.2. Redundancy of Cre-Drive Lines

For most retinal cell-types, Table 1 lists more than one Cre-drive line. It is important to know that these seemly redundant Cre-drive lines are necessary. As most published Cre-drive lines derived from the same or similar promoters are not identical, it is ideal to have several usable Cre-drive lines for a particular cell-type due to the following considerations. First, a range of Cre expression levels provide choice to achieve a suitable degree of gene inactivation for a particular study. Second, variable ecotopic expression patterns between the Cre-expressing lines may produce unintended phenotypes that may be beneficial [24]. Third, transgenic cre is localized on one of the 20 chromosomes in mice. There is a 5 percent of possibility that cre may be residing on the same chromosome where a loxP-flanked gene is localized. Having more than one Cre-drive line for a targeted tissue/cell-type is likely to provide a choice for the successful generation of a conditional gene knockout mouse. Therefore, publishing a Cre-drive line for a particular cell-type with already established drive lines should be encouraged. Since there have not been many side-by-side studies comparing different Cre-drive lines as performed by Ivanova et al. recently [31], it is not possible to give an accurate account of the differences among Cre-drive lines that target a particular cell-type. This review only provides a roadmap about the available resources. To select the most desirable Cre-drive line, end users should perform side-by-side comparison, if necessary.

3.3. Types of Cre-Drive Lines

While the traditional transgenic approaches have proved to be useful for generating Cre-drive lines, the inherent problems associated with this approach [50] may cause variability in mutant phenotypes among animals. This variability sometimes may result in unintended expression pattern that may or may not be useful for other studies [24]. The use of knock-in or bacterial artificial chromosome based transgenic approaches is likely to produce Cre-drive lines with the expression patterns that more closely resemble the characteristics of the promoters. In addition, the variability in Cre expression among animals can be reduced using these transgenic approaches. For these reasons, the Cre-drive lines referenced in Table 1 also provide information on how these Cre-expressing mice were generated. It is important to keep in mind that a Cre-drive line generated with a knock-in approach may affect the expression of the native gene and careful phenotyping of Cre-expressing mice are necessary.

Table 1 also includes information about whether Cre-expressing lines are generated using an inducible promoter system such as tetracycline- or tamoxifen-inducible systems [51, 52]. While inducible tissue-/cell-specific gene knockout approach is more advantageous, there are inherent problems associated with these systems, such as leakiness [53, 54]. Efficient delivery of inducing agents to the targeted retinal cells at the peak of promoter activity is the key to the success of inducible Cre expression. Although inducing gene expression in a tetracycline-inducible system with doxycycline for a short period of time may not be harmful to the retina [55], one should always keep in mind that tamoxifen may be toxic to the retina [56]. One distinctive advantage of using inducible systems is their ability to turn off/down the expression of Cre, which may be toxic to the targeted cells [19, 21].

3.4. Cre Toxicity

Cre is a DNA recombinase and may cause unintended chromosomal rearrangement at cryptic sites [57, 58]. Proper control of Cre expression is required for Cre-drive lines and a careful phenotypic analysis of Cre-drive lines is a prerequisite for conditional gene targeting. However, the Cre toxicity may not be the only contributing factor that caused retinal denegation in Cre-expressing rod-specific Cre mice [19, 21]. As expression of human rhodorpsin-GFP fusion, a nontoxic protein, also caused progressive rod photoreceptor degeneration [59], it is likely that a high level of expression of an exogenous protein may be toxic to the host protein transcription/translation/maturation system in rods.

3.5. New Cre-Drive Lines

For the past decade or so, many laboratories have contributed considerable effort in establishing various Cre-drive lines. While Cre-expressing mice have been used successfully in conditional gene targeting, there are not sufficient Cre-drive lines, even for the most advanced field, photoreceptor biology. Due to a high level of Cre expression causes rod degeneration, it would be ideal to have at least one inducible Cre-drive line for rods. As there are at least fifty types of retinal neurons, the current list (Table 1) is far from completion. However, for most retinal cell-types, a major shortcoming of most currently available Cre-drive lines is a lack of temporal or spatial specificities and desired efficiencies. Significant improvement in this area is needed. At present, a major challenge for Cre/lox-based conditional gene targeting is the difficulties to obtain Cre-drive lines with desired tissue-specificities. A lack of “ideal” promoters is the major reason. Therefore, it is worthwhile to invest some effort on studying the expression pattern of potential promoters that drive Cre expression before making a mouse.

4. Dissecting Cellular Mechanisms of Retinal Degeneration

4.1. Photoreceptor Survival under Photo-Oxidative Stress

A major focus in retinal denegation is to reveal the mechanisms of photoreceptor survival. As many of the survival factors are essential for development, global disruption of these essential genes often causes embryonic lethality. Using Cre/lox-based conditional gene targeting approach, Haruta et al. demonstrated that Rac1, a component of NADPH oxidase that produces reactive oxygen species, was required for the rod photoreceptor protection from photo-oxidative stress [60]. To determine photoreceptor survival mechanisms under photo-oxidative stress, Ueki et al. used rod-specific gp130 knockout mice and showed that preconditioning of mice with a sublethal photo-oxidative stress activated an autonomous protective mechanism in rods through gp130, an IL6 cytokine receptor, and, its downstream target STAT3 [61]. To determine further whether Müller cells, major retinal supporting cells often played a role in photoreceptor protection by releasing survival factors, were involved in this process, they demonstrated that gp130 activation in Müller cells had no additional effect for rod survival under photo-oxidative stress [47]. While this study demonstrates the neuroprotective role of gp130-STAT3 pathway in the rod photoreceptors under the chronic photo-oxidative stress, another series of studies showed that the PI-3 kinase/AKT pathway could protect rod photoreceptors under the acute photo-oxidative stress. Using a conditional gene knockout approach, Rajala et al. showed that insulin receptor, a PI-3 kinase upstream regulator, had a protective effect to rod photoreceptors under the acute photo-oxidative stress [62]. In another study using a conventional gene targeting approach, disruption of AKT2, a PI-3 kinase downstream target, accelerated the acute photo-oxidative stress-induced rod photoreceptor degeneration [63]. Finally, Zheng et al. demonstrated that BCL-xl, a downstream target of AKT, was a rod survival factor under acute photo-oxidative stress [44]. These studies clearly mapped the significance of PI-3 kinase/AKT pathway in stress-induced rod photoreceptor survival in vivo.

4.2. Protein Trafficking and Photoreceptor Degeneration

Kinesin-II is a molecular motor localized to the inner segment, connecting cilium, and axoneme of mammalian photoreceptors. The involvement of kinesin-II in protein trafficking through the mammalian photoreceptor cilium was initially probed with Cre/lox-based conditional gene targeting. Loss of kinesin-II in rods caused significant accumulations of opsin, arrestin, and membrane proteins within the photoreceptor inner segment, which ultimately led to the death of photoreceptors, a phenotype that is commonly observed in retinitis pigmentosa [20]. Further experiments also suggested that ectopic accumulation of opsin was a primary result of rod-specific kinesin-II deletion [21]. Using a conditional gene targeting approach, Avasthi et al. recently demonstrated that heterotrimeric kinesin-II acted as a molecular motor for proper trafficking of membrane proteins within the cone photoreceptors [64]. These conditional gene targeting studies established an unequivocal role of kinesin-II as a molecular motor that facilitates protein membrane trafficking in the photoreceptors.

4.3. Conditional Gene Targeting in the RPE

RPE is the gatekeeper of the retina and plays a pivotal role in the maintenance of retinal neurons. Abnormal RPE function is associated with both the wet and dry-forms of age-related macular denegation (AMD) (for review see [65, 66]). Although the pathogenic mechanisms for dry-AMD is unclear, clinical evidence suggests that photoreceptor degeneration is a consequence of impaired RPE functions [67, 68]. RPE-specific gene targeting will be a powerful approach for functional analysis of the RPE-expressed genes in the pathogenesis of dry-AMD. Whereas the use of conditional gene targeting in the PRE is still at its infancy, investigating the role of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF or VEGF-A), a potent angiogenic factor whose polymorphisms are associated with AMD [69, 70], in choroidal vascular development has yield some information related to the relationship between the RPE-derived VEGF and choroidal vasculature [2, 71]. As abnormal choroidal vasculature is clearly associated with both the dry- and wet-AMD [72–75], the genetic systems established in these studies may have some utility for AMD research. While the conditional gene targeting approach has yet to reach its full potential in AMD research, Lewin et al. recently demonstrated that disruption of mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase (SOD) in the RPE produced a geographic atrophy-like phenotypes in mice [76]. Here again, tissue/celltype-specific disruption of widely expressed genes, such as VEGF and SOD, circumvents the interference of nontargeting tissues/cells and is likely a direction for generating animal models used for mechanistic, diagnostic, and therapeutic investigations in the years to come.

5. Concluding Remarks

Remarkable progress has been made since the publication of the first study on the retinal denegation using a conditional gene targeting approach a decade ago [20]. It is also important to realize that, except in protein trafficking and photoreceptor survival, progress in other areas of retinal biology is not keeping the pace. At present, cellular mechanisms of many trophic factors and their signaling pathways in the retina remains unclear. Although the RPE and Müller cells are two major retinal supporting cell-types, the post-developmental functions of RPE and retinal Müller cell-derived trophic factors and their signaling mechanisms have remained largely uninvestigated. Substantial effort is necessary to establish a framework for cellular mechanisms of inherited retinal degeneration, AMD, and diabetes-induced retinal neuron degeneration. Many of these investigations will require the use of conditional gene targeting approach. With the improved Cre-drive lines and effort in investigating cell-specific function of trophic factors and their signaling, significant progress in our understanding of retinal degeneration will be achieved in the near future. Ultimately, these findings will help to design therapeutic approaches for the treatment of the retinal degenerative diseases.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Brian Sauer for giving him the opportunity to work with the Cre/lox system, Dr. Robert E. Anderson for recruiting him to the field of retinal biology, Dr. John D. Ash for scientific and technical advices related to the retina, members of his laboratory for generating and characterizing retinal cell-specific Cre mice, and Dr. Ivana Ivanovic for critical reading/editing of this paper. The research in his laboratory is supported by NIH Grants nos. R01EY20900, P20RR17703, P20RR024215, and P30EY12190. Beckman Initiative for Macular Research Grant 1003, American Diabetes Association Grant 1-10-BS-94, Foundation fighting blindness grant BR-CMM-0808-0453-UOK, Oklahoma Center for Advancement of Science and Technology Contract HR09-058, and the Unrestricted Research Awards from Hope for Vision and Research to Prevent Blindness.

References

- 1.Ferrara N, Carver-Moore K, Chen H, et al. Heterozygous embryonic lethality induced by targeted inactivation of the VEGF gene. Nature. 1996;380(6573):439–442. doi: 10.1038/380439a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le YZ, Bai Y, Zhu M, Zheng L. Temporal requirement of RPE-derived VEGF in the development of choroidal vasculature. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2010;112(6):1584–1592. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06573.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bai Y, Ma JX, Guo J, et al. Müller cell-derived VEGF is a significant contributor to retinal neovascularization. Journal of Pathology. 2009;219(4):446–454. doi: 10.1002/path.2611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fukushige S, Sauer B. Genomic targeting with a positive-selection lox integration vector allows highly reproducible gene expression in mammalian cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992;89(17):7905–7909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.7905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sauer B, Henderson N. Site-specific DNA recombination in mammalian cells by the Cre recombinase of bacteriophage P1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1988;85(14):5166–5170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nunes-Düby SE, Kwon HJ, Tirumalai RS, Ellenberger T, Landy A. Similarities and differences among 105 members of the Int family of site-specific recombinases. Nucleic Acids Research. 1998;26(2):391–406. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.2.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo F, Gopaul DN, van Duyne GD. Structure of Cre recombinase complexed with DNA in a site-specific recombination synapse. Nature. 1997;389(6646):40–46. doi: 10.1038/37925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Le Y, Gagneten S, Tombaccini D, Bethke B, Sauer B. Nuclear targeting determinants of the phage P1 Cre DNA recombinase. Nucleic Acids Research. 1999;27(24):4703–4709. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.24.4703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gagneten S, Le Y, Miller J, Sauer B. Brief expression of a GFPcre fusion gene in embryonic stem cells allows rapid retrieval of site-specific genomic deletions. Nucleic Acids Research. 1997;25(16):3326–3331. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.16.3326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lakso M, Sauer B, Mosinger B, Jr., et al. Targeted oncogene activation by site-specific recombination in transgenic mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992;89(14):6232–6236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Madsen L, Labrecque N, Engberg J, et al. Mice lacking all conventional MHC class II genes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(18):10338–10343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith AJH, de Sousa MA, Kwabi-Addo B, Heppell-Parton A, Impey H, Rabbitts P. A site-directed chromosomal translocation induced in embryonic stem cells by Cre-loxP recombination. Nature Genetics. 1995;9(4):376–385. doi: 10.1038/ng0495-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le Y, Gagneten S, Larson T, et al. Far-upstream elements are dispensable for tissue-specific proenkephalin expression using a Cre-mediated knock-in strategy. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2003;84(4):689–697. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soukharev S, Miller JL, Sauer B. Segmental genomic replacement in embryonic stem cells by double lox targeting. Nucleic Acids Research. 1999;27(18, article e21) doi: 10.1093/nar/27.18.e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bethke B, Sauer B. Segmental genomic replacement by Cre-mediated recombination: genotoxic stress activation of the p53 promoter in single-copy transformants. Nucleic Acids Research. 1997;25(14):2828–2834. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.14.2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu H, Marth JD, Orban PC, Mossmann H, Rajewsky K. Deletion of a DNA polymerase β gene segment in T cells using cell type-specific gene targeting. Science. 1994;265(5168):103–106. doi: 10.1126/science.8016642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le YZ, Ash JD, Al-Ubaidi MR, Chen Y, Ma JX, Anderson RE. Targeted expression of Cre recombinase to cone photoreceptors in transgenic mice. Molecular Vision. 2004;10:1011–1018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akimoto M, Filippova E, Gage PJ, Zhu X, Craft CM, Swaroop A. Transgenic mice expressing Cre-recombinase specifically in M- or S-cone photoreceptors. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2004;45(1):42–47. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le YZ, Zheng L, Zheng W, et al. Mouse opsin promoter-directed Cre recombinase expression in transgenic mice. Molecular Vision. 2006;12:389–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marszalek JR, Liu X, Roberts EA, et al. Genetic evidence for selective transport of opsin and arrestin by kinesin-II in mammalian photoreceptors. Cell. 2000;102(2):175–187. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jimeno D, Feiner L, Lillo C, et al. Analysis of kinesin-2 function in photoreceptor cells using synchronous Cre-loxP knockout of Kif3a with RHO-Cre. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2006;47(11):5039–5046. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li S, Chen D, Sauvé Y, McCandless J, Chen YJ, Chen CK. Rhodopsin-iCre transgenic mouse line for Cre-mediated rod-specific gene targeting. Genesis. 2005;41(2):73–80. doi: 10.1002/gene.20097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le YZ, Zheng W, Rao PC, et al. Inducible expression of Cre recombinase in the retinal pigmented epithelium. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2008;49(3):1248–1253. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu M, Ueki Y, Ash JD, Zheng L, Le YZ. Unexpected transcriptional activity of human VMD2 promoter. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2010;664:211–216. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1399-9_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guyonneau L, Rossier A, Richard C, Hummler E, Beermann F. Expression of Cre recombinase in pigment cells. Pigment Cell Research. 2002;15(4):305–309. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0749.2002.02039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mori M, Metzger D, Garnier JM, Chambon P, Mark M. Site-specific somatic mutagenesis in the retinal pigment epithelium. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2002;43(5):1384–1388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao H, Yang Y, Rizo CM, Overbeek PA, Robinson ML. Insertion of a Pax6 consensus binding site into the αA-crystallin promoter acts as a lens epithelial cell enhancer in transgenic mice. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2004;45(6):1930–1939. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roesch K, Jadhav AP, Trimarchi JM, et al. The transcriptome of retinal Müller glial cells. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2008;509(2):225–238. doi: 10.1002/cne.21730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ueki Y, Ash JD, Zhu M, Zheng L, Le YZ. Expression of Cre recombinase in retinal Muller cells. Vision Research. 2009;49(6):615–621. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slezak M, Göritz C, Niemiec A, et al. Transgenic mice for conditional gene manipulation in astroglial cells. GLIA. 2007;55(15):1565–1576. doi: 10.1002/glia.20570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ivanova E, Hwang GS, Pan ZH. Characterization of transgenic mouse lines expressing Cre recombinase in the retina. Neuroscience. 2010;165(1):233–243. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dewachter I, Reversé D, Caluwaerts N, et al. Neuronal deficiency of presenilin 1 inhibits amyloid plaque formation and corrects hippocampal long-term potentiation but not a cognitive defect of amyloid precursor protein [V7171] transgenic mice. Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22(9):3445–3453. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03445.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hatori M, Le H, Vollmers C, et al. Inducible ablation of melanopsin-expressing retinal ganglion cells reveals their central role in non-image forming visual responses. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(6, article e2451) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang Z, Ding K, Pan L, Deng M, Gan L. Math5 determines the competence state of retinal ganglion cell progenitors. Developmental Biology. 2003;264(1):240–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campsall KD, Mazerolle CJ, de Repentingy Y, Kothary R, Wallace VA. Characterization of transgene expression and Cre recombinase activity in a panel of Thy-1 promoter-Cre transgenic mice. Developmental Dynamics. 2002;224(2):135–143. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gong S, Doughty M, Harbaugh CR, et al. Targeting Cre recombinase to specific neuron populations with bacterial artificial chromosome constructs. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(37):9817–9823. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2707-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saito H, Tsumura H, Otake S, Nishida A, Furukawa T, Suzuki N. L7/Pcp-2-specific expression of Cre recombinase using knock-in approach. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2005;331(4):1216–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang XM, Chen BY, Ng AHL, et al. Transgenic mice expressing Cre-recombinase specifically in retinal rod bipolar neurons. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2005;46(10):3515–3520. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakhai H, Sel S, Favor J, et al. Ptf1a is essential for the differentiation of GABAergic and glycinergic amacrine cells and horizontal cells in the mouse retina. Development. 2007;134(6):1151–1160. doi: 10.1242/dev.02781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rowan S, Cepko CL. Genetic analysis of the homeodomain transcription factor Chx10 in the retina using a novel multifunctional BAC transgenic mouse reporter. Developmental Biology. 2004;271(2):388–402. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weber P, Metzger D, Chambon P. Temporally controlled targeted somatic mutagenesis in the mouse brain. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;14(11):1777–1783. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Furuta Y, Lagutin O, Hogan BLM, Oliver GC. Retina- and ventral forebrain-specific Cre recombinase activity in transgenic mice. Genesis. 2000;26(2):130–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sato S, Inoue T, Terada K, et al. Dkk3-Cre BAC transgenic mouse line: a tool for highly efficient gene deletion in retinal progenitor cells. Genesis. 2007;45(8):502–507. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng L, Anderson RE, Agbaga MP, Rucker EB, 3rd, Le YZ. Loss of BCL-X in rod photoreceptors: increased susceptibility to bright light stress. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2006;47(12):5583–5589. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ueki Y, Wang J, Chollangi S, Ash JD. STAT3 activation in photoreceptors by leukemia inhibitory factor is associated with protection from light damage. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2008;105(3):784–796. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Betz UAK, Vosshenrich CAJ, Rajewsky K, Muller W. Bypass of lethality with mosaic mice generated by Cre-loxP-mediated recombination. Current Biology. 1996;6(10):1307–1316. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)70717-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ueki Y, Chollangi S, Le YZ, Ash JD. gp130 activation in Müller cells is not essential for photoreceptor protection from light damage. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2010;664:655–661. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1399-9_75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang J, Xu E, Elliott MH, Zhu M, Le Y-Z. Müller cell-derived VEGF is essential for diabetes-induced retinal inflammation and vascular leakage. Diabetes. 2010;59(9):2297–2305. doi: 10.2337/db09-1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nishijima K, Ng YS, Zhong L, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor-A is a survival factor for retinal neurons and a critical neuroprotectant during the adaptive response to ischemic injury. American Journal of Pathology. 2007;171(1):53–67. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jaenisch R. Transgenic animals. Science. 1988;240(4858):1468–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.3287623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gossen M, Freundlieb S, Bender G, Muller G, Hillen W, Bujard H. Transcriptional activation by tetracyclines in mammalian cells. Science. 1995;268(5218):1766–1769. doi: 10.1126/science.7792603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Feil R, Brocard J, Mascrez B, LeMeur M, Metzger D, Chambon P. Ligand-activated site-specific recombination in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93(20):10887–10890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Le Y, Miller JL, Sauer B. GFPcre fusion vectors with enhanced expression. Analytical Biochemistry. 1999;270(2):334–336. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Feil S, Valtcheva N, Feil R. Inducible Cre mice. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2009;530:343–363. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-471-1_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chang MA, Horner JW, Conklin BR, DePinho RA, Bok D, Zack DJ. Tetracycline-inducible system for photoreceptor-specific gene expression. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2000;41(13):4281–4287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gerner EW. Ocular toxicity of tamoxifen. Annals of Ophthalmology. 1989;21(11):420–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Loonstra A, Vooijs M, Beverloo HB, et al. Growth inhibition and DNA damage induced by Cre recombinase in mammalian cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(16):9209–9214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161269798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schmidt EE, Taylor DS, Prigge JR, Barnett S, Capecchi MR. Illegitimate Cre-dependent chromosome rearrangements in transgenic mouse spermatids. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(25):13702–13707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240471297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chan F, Bradley A, Wensel TG, Wilson JH. Knock-in human rhodopsin-GFP fusions as mouse models for human disease and targets for gene therapy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(24):9109–9114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403149101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haruta M, Bush RA, Kjellstrom S, et al. Depleting Rac1 in mouse rod photoreceptors protects them from photo-oxidative stress without affecting their structure or function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(23):9397–9402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808940106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ueki Y, Le YZ, Chollangi S, Muller W, Ash JD. Preconditioning-induced protection of photoreceptors requires activation of the signal-transducing receptor gp130 in photoreceptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(50):21389–21394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906156106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rajala A, Tanito M, Le YZ, Kahn CR, Rajala RVS. Loss of neuroprotective survival signal in mice lacking insulin receptor gene in rod photoreceptor cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(28):19781–19792. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802374200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li G, Anderson RE, Tomita H, et al. Nonredundant role of Akt2 for neuroprotection of rod photoreceptor cells from light-induced cell death. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(1):203–211. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0445-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Avasthi P, Watt CB, Williams DS, et al. Trafficking of membrane proteins to cone but not rod outer segments is dependent on heterotrimeric kinesin-II. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(45):14287–14298. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3976-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sunness JS. The natural history of geographic atrophy, the advanced atrophic form of age-related macular degeneration. Molecular Vision. 1999;5, article 25 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zarbin MA. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2004;122(4):598–614. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sarks JP, Sarks SH, Killingsworth MC. Evolution of geographic atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium. Eye. 1988;2(5):552–577. doi: 10.1038/eye.1988.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sarks SH. Ageing and degeneration in the macular region: a clinico pathological study. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 1976;60(5):324–341. doi: 10.1136/bjo.60.5.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Churchill AJ, Carter JG, Lovell HC, et al. VEGF polymorphisms are associated with neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Human Molecular Genetics. 2006;15(19):2955–2961. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Boekhoorn SS, Isaacs A, Uitterlinden AG, et al. Polymorphisms in the vascular endothelial growth factor gene and risk of age-related macular degeneration. The Rotterdam Study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(11):1899–1903. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Marneros AG, Fan J, Yokoyama Y, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression in the retinal pigment epithelium is essential for choriocapillaris development and visual function. American Journal of Pathology. 2005;167(5):1451–1459. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61231-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grunwald JE, Hariprasad SM, DuPont J, et al. Foveolar choroidal blood flow in age-related macular degeneration. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 1998;39(2):385–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McLeod DS, Grebe R, Bhutto I, Merges C, Baba T, Lutty GA. Relationship between RPE and choriocapillaris in age-related macular degeneration. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2009;50(10):4982–4991. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yi X, Ogata N, Komada M, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression in choroidal neovascularization in rats. Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 1997;235(5):313–319. doi: 10.1007/BF01739641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ishibashi T, Hata Y, Yoshikawa H, Nakagawa K, Sueishi K, Inomata H. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in experimental choroidal neovascularization. Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 1997;235(3):159–167. doi: 10.1007/BF00941723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lewin A, Gibson S, Liu J, Hauswirth WW, Le YZ. Generation of a Mouse Model of Early AMD by Induction of Oxidative Stress. ARVO Abstract, 6414, 2010.