Abstract

Biomaterials have the potential to be utilized as immunostimulatory or immunosuppressive delivery agents for biologics. It is hypothesized that this is directed by the ability of a biomaterial to drive dendritic cells (DC) in situ toward an immunostimulatory or an immunosuppressive phenotype, respectively. However, the specific pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that DCs use to recognize and respond to biomaterials are unknown. From among the many receptors that DCs use to recognize and respond to foreign entities, herein the focus is on integrins. A biomaterial that induces DC maturation, namely poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid (PLGA), supported increased human monocyte-derived DC adhesion and up-regulation of integrin receptor gene expression, measured via RT-PCR, as compared to culture on tissue culture polystyrene (TCPS). This was not observed for a biomaterial that does not support DC maturation. Through antibody-blocking techniques, the adhesion to both TCPS and PLGA was found to be β2 integrin dependent and β1 independent. Significantly, inhibiting β2-mediated adhesion to biomaterials via blocking antibodies also lowered the level of maturation of DCs (CD86 expression). β2 integrins (but not β1) were found localized in biomaterial-adherent DC podosomes and also were found in direct contact with the PLGA surface. Therefore, it appeared that β2 integrin-mediated adhesion is involved in determining the state of DC maturation on the PLGA surface. DC adhesion to biomaterials may be engaged or avoided to manipulate an immune response to biological component delivered with a biomaterial carrier.

Introduction

Dendritic cells are sentinels continuously surveying the body for pathogens. Upon recognition and uptake of foreign entities, their status as professional antigen-presenting cells (1, 2) serves to link the innate immune response to an antigen-specific adaptive response. DCs possess PRRs which aid in their response to foreign entities (e.g. pathogens) by binding pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) (3, 4). Upon recognizing PAMPs, DCs undergo a phenotypic shift from an immature (iDC) to a mature (mDC) state. As iDCs, they lack T cell stimulatory capacity (with low CD80/CD86 and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II surface expression), have a high phagocytic capacity and also have a rounded morphology. But upon maturation, DCs up-regulate CD80/CD86 as well as MHC II expression (2, 5, 6). Mature DCs also have a low phagocytic capacity and possess a “dendritic” morphology for increased interaction with T cells (2). The other side of maintaining immune homeostasis is that interaction of T cells with iDC or tolerogenic DCs maintains or induces immune tolerance through induction of T cell anergy or regulatory T cell induction (1). Thus, DCs may activate or passivate an immune response accordingly depending on their phenotypic status.

Tissue engineered devices utilize a biomaterial delivery vehicle (e.g. scaffold or a microparticle) for a biological component (7, 8). The host response to a tissue engineered device is composed of a non-specific inflammatory response toward the biomaterial component and an antigen-specific immune response toward the biologic (9, 10). In the case of non-autologous biologics, an immune response toward the therapeutic cell or protein is a major challenge, for example in tissue engineering (11), and we have previously found that the biomaterial scaffold may act as an adjuvant toward the co-delivered biologic (12). Biomaterial scaffolds of PLGA induce significantly higher and longer lasting humoral immune response toward a model antigen, ovalbumin, than scaffolds made of agarose (13). We hypothesize that the biomaterial-induced adjuvant effect (or lack thereof) is due to the DC response within the complex non-specific inflammatory reaction toward the biomaterial in vivo (9, 10). Furthermore, we have found that DCs treated with biomaterials used in combination products in vitro differentially induce or inhibit DC maturation (14–16). PLGA or chitosan films induced maturation of DC as seen in increases in cytokine production and CD86 expression, while this effect was not observed when DCs were treated with hyaluronic acid or agarose films. This illustrates the importance of material selection for tissue-engineered devices or vaccine delivery systems as biomaterials may influence the immune response toward the co-delivered biologic.

To begin to understand biomaterial-induced DC maturation, an investigation was undertaken to understand DC adhesion to biomaterials and its contribution to DC phenotype. This direction was suggested by preliminary observations that indicated an increase in DC adhesion on PLGA compared to other substrates (TCPS or agarose films). Cellular adhesion to biomaterials has been extensively studied as it mediates cellular responses with beneficial effects (e.g. endothelial coverage on vascular grafts) or detrimental effects (e.g. fibrous encapsulation) (17). The most well-characterized adhesion molecules used by leukocytes to mediate their adhesion to biomaterials are integrins (18), which are transmembrane heterodimer receptors composed of both α and β subunits (19, 20). Leukocytes uniquely possess the β2 family of integrins (αLβ2, αMβ2, αXβ2) that allow for transmigration in response to infection or inflammation (21). β2 integrins have been shown to be involved in the adhesion of monocyte/macrophages to biomaterials (22–24) and phagocyte accumulation on implants in vivo (25). Circulating or monocyte-derived myeloid DCs, which are particularly relevant in the response to biomaterial implants, possess integrins of both the β1 and β2 family (26, 27). DC integrin-mediated adhesion to known ligands such as fibronectin (28, 29) and fibrinogen (30) pre-coated on material surfaces has been shown. Furthermore, while different plasma/serum protein substrates elicit similar DC adhesion, they are capable of differentially influencing cytokine production (31); thus, different protein substrates may influence the response of DCs. As PRRs, αMβ2 (complement receptor, CR3) and αXβ2 (CR4) play a role in DC recognition of opsonized foreign entities, and CRs have been shown to play a role in monocyte recognition of a biomaterial (32). However, to date the role of integrin-mediated adhesion in substrate-induced DC maturation remains unknown.

Materials and Methods

Biomaterial Preparation

A solution of 10% w/v PLGA (mole ratio 75:25, inherent viscosity 0.70 dL/g in trichloromethane; Durect/Lactel Absorbable Polymers, Birmingham, AL) was prepared in 20mL dichloromethane overnight in sterile polypropylene tubes (33). To form films, this solution was gently poured into a cleaned 100mm Teflon dish and allowed to sit for two days in fume hood until DCM had evaporated. PLGA films (2mm in thickness) for use were punched out with arch punches for 24 well plates (9/16″) or 6 well plates (5/4″) and rinsed for 1h with sterile water. Films were allowed to dry in biosafety cabinet, sterilized with UV (30min each side) and rinsed with endotoxin free water immediately prior to use. Films were placed in bottom of wells and cells treated as described below. PLGA films were routinely tested for endotoxin content using Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) assay (QCL-1000, Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) with detected levels of approximately 0.1 EU/mL.

Three percent (w/v) agarose (Type V) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) films were prepared by microwaving agarose/water suspension for 30s. This solution was then cast in 6 well plates and allowed to cool at 4°C for 30 min. The films were brought to room temperature for at least 1h before use in cell culture. Resulting films were distributed across the wells with an average thickness of 3mm (approximately 2mm in the center of well and 4mm at edges).

Dendritic Cell Culture

Human peripheral blood was drawn from healthy donors with informed consent at Georgia Tech Student Health Center by trained phlebolotomist in accordance with Georgia Institute of Technology Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocol #H10011. Dendritic cells were differentiated from monocytes as previously described (34) with modifications (33). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by overlaying diluted whole blood (1:1 dilution in sterile Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline (D-PBS) [Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA], pH 7.2) on lymphocyte separation media [Cellgro, Herndon, VA] followed by differential centrifugation (400g, 30min at room temperature). PMBCs were collected from buffy-coats and washed once with D-PBS (10min, 1100rpm). Red blood cells were lysed in solution containing 155 mM ammonium chloride, 10 mM potassium bicarbonate (both from Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and 0.1 mM ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA) (Invitrogen). Cells were then rinsed twice with D-PBS (10min, 100rpm) followed by suspension in complete DC media (RPMI 1640 [Invitrogen] supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin all filtered through 0.2 μm filter) at 5×106/mL. Approximately 50×106 cells per 100mm Primaria culture dish (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) were cultured at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air for 2h, after which three complete DC media rinses were performed to remove non-adherent lymphocytes and leave remaining adherent monocytes. Complete DC media containing 800U/mL interleukin (IL)-4 and 1000U/mL granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (both from Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) was freshly added to monocytes to induce differentiation for 5 days at 37°C. On day 5, immature non-adherent DCs were collected, and re-suspended at 5×105/mL in complete DC media with cytokines for use as described below.

Dendritic Cell Treatment and RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis

Dendritic cells were collected on Day 5 of culture and treated in 6 well plates (Costar) (Corning, Corning, NY) with fresh complete media as untreated iDC for negative control, treated with ultrapure-LPS (a TLR4-specific ligand, 1μg/mL) (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA) as a positive-control for maturation to provide mature DCs (mDCs), or treated with PLGA or agarose films for 24h at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cell viability is routinely > 95% following treatment as assessed via propidium iodide staining or trypan blue exclusion. Non-adherent DCs were collected by gentle pipetting and pooled together with adherent DCs which were collected by addition and pipetting with cell dissociation solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). This pooled fraction was then purified for DCs using magnetic bead isolation. Briefly, cells were incubated with dendritic-cell specific ICAM grabbing non-integrin (DC-SIGN) microbeads along with Fc-receptor blocking solution (Miltenyi Biotec, Gladbach, Germany) per manufacturer’s protocol, rinsed and passed through an LS column placed in a midiMACs (Miltenyi Biotec) magnet to purify DC-SIGN+ DCs and remove B cells. To assess purity, DC-SIGN+ fraction was double-stained with DC-SIGN-FITC (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, clone 120507) and CD19-APC (Miltenyi Biotec, clone LT19). Final purified cell population was at least >95% DC-SIGN+ and <1% CD19+.

Purified DCs were used for RNA isolation using RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentration (A260nm) and quality (A260nm/A280nm > 2) was measured using NanoDrop 1000 (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) and stored at −80°C. The Quantitect RT Kit (Qiagen) was used to prepare cDNA according to the manufacturer. For each DC treatment, 10 ng of RNA (per single qRT-PCR reaction) multiplied by the number of reactions needed total was used for cDNA synthesis immediately following genomic DNA removal by DNAse I treatment (Qiagen). Reverse transcription was undertaken at 42°C for 20min in a water bath followed by immediate placement in 95°C heat-block for 3 min to inactivate reverse transcriptase. cDNA was then used for q-RT-PCR.

Primer Selection and Gene Expression Analysis

Integrins, adhesion molecules, integrin-related signaling molecules as well as two housekeeping genes (β-actin and β2-microglobulin) were selected for primer design partially based on known monocyte-derived DC integrin expression (26). Primers were chosen using Harvard PrimerBank (35) (Table 1) and appropriate forward and reverse pairs were chosen which minimized hairpin and primer-dimer formation as assessed using NetPrimer (Premier Biosoft International, Palo Alto, CA), were less than or equal to 250bp in amplicon size and had a melting temperature (Tm) of approximately 60°C. Forward and reverse primer synthesis was outsourced (Sigma) and pairs pooled. For validation/sequencing, primer pairs (1μM final concentration) were used to amplify an iDC sample cDNA prepared using HotStarTaq Plus PCR kit (Qiagen) following manufacturer’s instructions. Amplicons were shipped overnight to Eurofins MWG Operon (Huntsville, AL) and sequences were validated using Basic Local Alignments Search Tool (BLAST) (36).

Table 1.

Primer pairs for integrins, adhesion molecules and related signaling molecules as well as house keeping genes were chosen from Harvard Primer Bank [35] with PrimerBank ID listed in table. For detailed information/sequences on each primer pair, please see http://pga.mgh.harvard.edu/primerbank/.

| Gene | PrimerBank ID |

|---|---|

| ITGB1 (CD29) | 19743813a3 |

| ITGB2 (CD18) | 4557886a1 |

| ITGAL (CD11a) | 4504757a2 |

| ITGAM (CD11b) | 4504759a3 |

| ITGAX (CD11c) | 34452173a3 |

| ITGA4 (CD49d) | 4504749a3 |

| ITGA5 (Cd49e) | 4504751a1 |

| CD54 (ICAM1) | 4557878a2 |

| CD44 | 21361193a2 |

| FAK | 23273417a3 |

| Paxillin | 4506345a3 |

| Talin1 | 16753233a2 |

| Vinculin | 4507877a1 |

| Beta Actin | 4501885a1 |

| B2M | 4757826a1 |

Following validation, primer pairs were then used for experimental analysis of relative gene expression. QuantiFast SYBR-Green PCR kit (Qiagen) was used to measure PCR amplification of converted cDNA from each treatment via StepOne Plus RT-PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). Briefly, cDNA from each treatment from a single donor was mixed with SYBR-green master mix and aliquoted into a single MicroAmp Fast Optical 96 well plate (Applied Biosystems) along with primer pairs (1μM). An initial activation step was performed at 95°C for 5 min followed 40 cycles of RT-PCR at 95°C for 10s and 58°C for 30s. Melt curve analysis was performed automatically following RT-PCR, and each gene product exhibited single-peak Tm’s. Baseline and threshold level were set manually, and settings used were constant for each sample analyzed.

Threshold cycles (Ct) for each gene were determined and normalized to the average Ct of β-actin and β2-microglobulin (ΔCt) across treatments (which did not significantly change). Inter-donor comparison of up or down-regulation of gene expression was determined by comparing ΔCt values from treated DCs for a specific gene with that of iDCs.

Hierarchical cluster analysis was performed using Matlab (The Mathworks, Natick, MA) to perform a 2D clustergram using −ΔCt data. Cluster analysis was performed using a Pearson correlation distance calculation for both genes and treatments. Heat maps were generated in Matlab but bin size and colors were manually chosen.

Intracellular/Extracellular Immunofluorescence of Adherent DCs

Extracellular staining of adherent DCs was completed following culture of human monocyte-derived DCs in 24 well plates on TCPS surface or PLGA films. For noted time points, non/loosely-adherent cells were removed by aspiration and adherent cells were rinsed twice with cold PBS. Cells were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (Polysciences Inc, Warrington, PA) for 10 min and rinsed three times with PBS. Non-specific sites were blocked with 3% human serum albumin (HSA) (EMD Chemicals, Darmstadt, Germany) in PBS at room temperature for 1h. A fluorochrome conjugated antibody for DC-SIGN-(FITC) (R&D Systems, clone 120507) was diluted in 3% HSA, added to wells and incubated for 2h at room temperature. Surfaces were rinsed three times in cold PBS and immediately mounted and coverslip added directly onto sample using ProLong Gold Antifade kit with DAPI (Invitrogen). Bright field and fluorescent images were taken using Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY).

Early (1.5h) DC integrin (extracellular) and F-actin (intracellular) co-localization was monitored with immunofluoresence following DC treatment with PLGA films as described above with the following modifications. DCs were treated with PLGA films in 24 well plates for 1.5h, rinsed with PBS, and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 5min. Cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 (Sigma) for 10 min, rinsed, and non-specific sites blocked with 5% FBS in PBS for 1h, 37°C. Subsequently, cells were stained with either monoclonal β1-FITC (TS2/16, BioLegend, San Diego, CA) or monoclonal β2-FITC antibodies (TS2/18, BioLegend) in combination with phalloidin-TRITC (Sigma) to visualize F-actin for 1h, 37°C in 5% FBS. Surfaces were then rinsed, and PLGA films were mounted on glass slides and images taken with Zeiss LSM 510 UV confocal microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY).

Integrin Antibody-Blocking Experiments

To undertake integrin antibody blocking, biomaterial treatments of DCs took place in 24 well plates (Corning Costar). Human DCs were cultured as before up to Day 5 and collected and pre-treated with anti-integrin antibodies for 1h at 37°C prior to treatment on either TCPS or PLGA films for 24h. Monoclonal integrin blocking antibodies included: anti-β1 (Clone: P5D2; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), anti-β2 (Clone: TS1/18; BioLegend), anti-αM (Clone: 44 or CBRM1/5; BioLegend), anti-αL (Clone: HI111; BioLegend), anti-αX (Clone: 3.9; BioLegend), or isotype mouse IgG1,κ (BioLegend). All antibodies came purified and endotoxin-free except for anti-β1 which was purified using Protein G column (Pierce) and dialyzed in sterile D-PBS for 2h to remove contaminants. Anti-β1 and anti-β2 pre-treatment on TCPS or PLGA were initially tested at increasing concentrations ranging from 10–120μg/mL to determine appropriate blocking concentration. β1 antibodies were used then at 10μg/mL while anti-β2 antibodies were used at 10, 20 or 40 μg/mL, as noted in text.

The effect of integrin blocking on DC adhesion was first assessed microscopically. Images were taken of DCs at 3 and 24h on TCPS and PLGA substrates using an Axiovert 135 (Zeiss). Also, the effect of integrin blocking was assessed via cell counting of non/loosely adherent DCs. The number of adherent DCs was not directly assessed because adhesion to TCPS was, for some donors, extremely limited, yielding difficult analysis of adherent cell counts. At 24h, non/loosely-adherent DCs were collected by rocking and gentle pipetting of DCs off the surface. Non/loosely adherent DCs were counted using Multisizer 3 Coulter Counter (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) analyzing population between 10–20μm in diameter only. These DCs were pelleted by centrifugation at 400g for 10min while the remaining adherent DCs were collected using addition of cell dissociation solution (Sigma), pipetting and incubation at 37°C to remove DC from the surfaces. Adherent and non/loosely adherent DCs were pooled together and stained with anti-CD86-PE (Ancell, Minneapolis, MN) for 1h, 4°C to assess DC maturation. DCs were also double stained when necessary with CD86-PE/β2-FITC (BioLegend) or CD86-PE/β1-FITC (BioLegend) to indirectly test the binding of anti-β2 or anti-β1 blocking antibodies as well as level of maturation with CD86. Flow cytometry was then performed, and DC population gated on the FSC/SSC plot for analysis of CD86 expression. For TCPS-cultured DCs, CD86 expression was defined as “low” (CD86low gate) if CD86 levels were below an intensity of 50. For PLGA-treated DCs, using the same setting for flow cytometry, since CD86 expression increases on the activating biomaterial PLGA, the CD86low gate was doubled to include any cell with intensity below 100. The percentage of total DCs in the CD86low gate (defined as “% immature DCs”) was then normalized for each pre-treatment to the levels found on isotype.

Integrin Cross-linking to Biomaterial Surface

To demonstrate direct integrin engagement at the DC-biomaterial interface, a cellular-substrate cross-link was performed and integrins visualized (37). Specifically, DCs were cross-linked to PLGA using an amine reactive cross-linker with a 12Å spacer arm length, DTSSP (3,3′-Dithiobis [sulfosuccinimidylpropionate]) (Pierce, Rockford, IL). For this method, DCs were treated with PLGA films in 24 well plates for 1.5h and subsequently non-adherent cells were removed via D-PBS rinses. Adherent DCs were then cross-linked to PLGA surface via 1mM DTSSP in 2mM glucose in D-PBS (30 min, room temperature). Unreacted DTSSP was then quenched with 50mM Tris (Sigma) in D-PBS (15 min). Non-cross-linked cellular material was then extracted in 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS, Sigma) with 350μg/mL phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma) in D-PBS. Surfaces were then rinsed with D-PBS, and blocked with 5% FBS in PBS for 1h, 37°C. For this experiment only, polyclonal goat anti-human antibodies against β1 and β2 integrins (both from R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) were incubated at 1:400 dilution in 5% FBS for 1h, 37°C. Following three D-PBS rinses, surfaces were incubated with donkey anti-goat-FITC secondary antibody (kindly provided by Dr. Robert Nerem of Georgia Institute of Technology) at 10μg/mL (Invitrogen) in 5% FBS for 1h, 37°C. Surfaces were rinsed, mounted as previously described and surfaces visualized with LSM 510 UV confocal microscope (Zeiss). Non-cross-linked controls were also performed as negative controls and yielded no positive integrin staining, indicating cross-linking was necessary to detect integrins engaged by the material surface.

Statistical Analysis

For statistical analysis of DC adhesion and maturation data, an ANOVA analysis was performed (GraphPad, LaJolla, CA) using Tukey-post test (p<0.05) with donors nested within treatment (n=5–8). When comparing data to a normalized value (1), a two-sided Student t-test was performed (p≤0.05).

Results

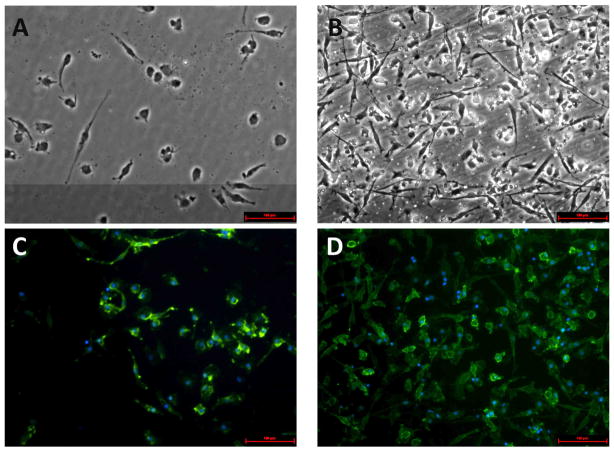

To initially investigate the level of DC adhesion to biomaterials, the adherent cell fraction on either TCPS or PLGA surfaces was imaged using microscopy. Adherent cells on both substrates were fixed and stained with DC surface marker (DC-SIGN) to assure the specific assessment of DCs. As shown in Figure 1, DCs present on TCPS surface mostly appeared round in morphology (Fig. 1A). This is in contrast to DCs treated with PLGA films which showed more cellular adhesion to the surface and nearly all DCs exhibited dendrites reaching over 100μm (Fig. 1B). On both substrates, each adherent cell was DC-SIGN+ (a human DC marker) (Fig. 1C,D) while being negative CD19 (B cells), a contaminating cell population in this culture system (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Adherent DC morphology on TCPS or PLGA films. DCs were cultured on TCPS (A,C) or treated with PLGA films (B,D) for 24h, stained with DC-SIGN-FITC and DAPI for nuclei visualization. Microscopy was performed at 20×. Representative of n=3 determinations. Scale bar denotes 100μm.

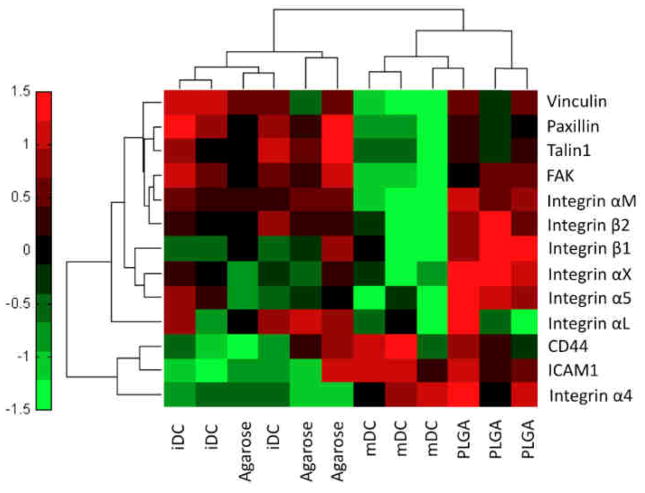

In order to pinpoint adhesion molecules potentially responsible for the recognition of biomaterials by DCs, a gene expression analysis was undertaken to determine how DC adhesion and/or DC activation influences integrin and other adhesion molecule mRNA expression. Dendritic cells were cultured on TCPS as a negative control for iDC, treated with PLGA or agarose films (14, 15), or cultured on TCPS and stimulated with ultrapure-LPS as a positive control for mDCs. As shown in Figure 2, DCs cultured on TCPS (iDC) or treated with agarose films showed similar gene expression patterns (qualitative analysis as seen through tight cluster) across all adhesion-related molecules investigated. In contrast, the activating treatments of PLGA films or ultrapure-LPS (mDC) clustered together, though to a lesser extent than agarose and TCPS (Fig. 2). Adhesion-related signaling molecules (such as FAK) were down-regulated in response to ultrapure-LPS but unaffected upon PLGA treatment. There was a noted difference in the integrin gene expression pattern to PLGA and ultrapure-LPS. While ultrapure-LPS induced down-regulation of integrin subunits (αM, β1, β2, αX, and α5), PLGA treatment induced an up-regulation of these molecules in DCs.

Figure 2.

Hierarchical cluster analysis of RT-PCR (−ΔCt) data for integrins and adhesion-related signaling molecules in DCs cultured on TCPS (iDC), treated with ultrapure-LPS (mDC), or treated with PLGA or agarose films for 24h. Heat map and 2D cluster analysis were performed using Matlab clustergram function assuming Pearson correlation distance calculation for both genes and treatments. Scale bar and color values denote ±1.5 standard deviation for each gene (row), n=3.

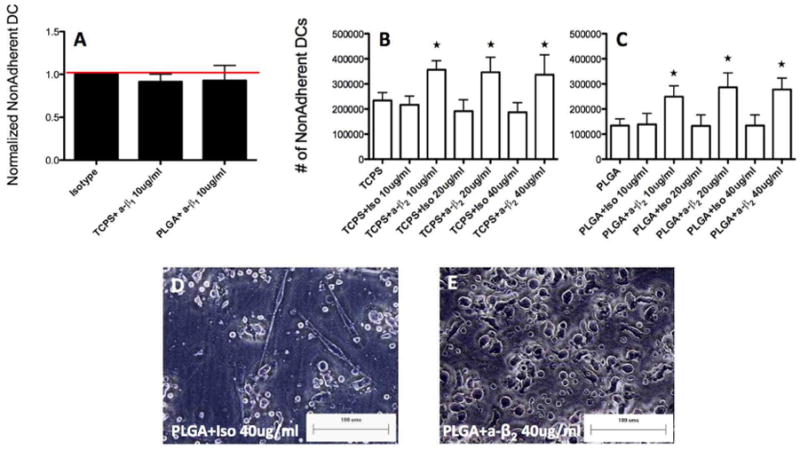

Next, the role of integrin families was investigated in DC adhesion to biomaterials using antibody-blocking techniques to inhibit β1 and β2 integrin family members. DC adhesion was measured by assessing the number of non/loosely adherent DCs (an inverse measurement of the number of cells adhering to the substrates) and compared to isotype control treatments. An anti-β1 blocking antibody (clone P5D2) was unable to affect extent of DC adhesion to both serum-coated (from the culture medium) TCPS or PLGA (Fig. 3A) but was able to inhibit DC adhesion and spreading to plasma fibronectin (pFN) coated glass cover slips (Supplemental Fig. 1) which has been shown by others (28), demonstrating functionality of the mAb with this ligand pre-coating. Two other monoclonal anti-β1 blocking antibodies (clones AIIB2 and JB1A) were similarly unable to inhibit DC adhesion to TCPS or PLGA (data not shown). Anti-β2 pre-treatment using blocking mAb TS1/18 (38), however, at all concentrations investigated (10, 20 and 40μg/mL) was able to inhibit adhesion of DCs to both TCPS and PLGA films (Fig. 3B,C) to levels significantly above isotype controls. The binding ability of anti-β2 was confirmed via flow cytometry using a fluorescently labeled antibody of the same clone which was unable to bind to DCs when pre-treated with anti-β2 but successfully bound in the presence of isotype (Supplemental Figure 2). The morphology of DCs treated with PLGA films was altered from being adherent and spread (Fig. 3D) to being rounded (Fig. 3E) when β2 binding was inhibited.

Figure 3.

β1 or β2 integrin antibody blocking of DCs cultured on TCPS or treated with PLGA films for 24h. (A) Anti-β1 (or isotype) at 10μg/mL treatment was performed and DCs were subsequently on cultured on TCPS or treated with PLGA films for 24h. Non/loosely adherent DCs were collected and counted and values were normalized to that of isotype control (n=2 independent determinations, mean+range). (B) DCs were cultured on TCPS for 24h following anti-β2 (or isotype) at 10, 20 or 40μg/mL treatment. Non-adherent DCs were collected, counted and averaged. Star indicates statistical difference from respective isotype and TCPS control (ANOVA, p<0.05) (n=5 independent determinations, mean+s.d.) (C) DCs were cultured on PLGA for 24h following anti-β2 (or isotype) at 10, 20 or 40μg/mL treatment. Non-adherent DCs were collected, counted and averaged. Star indicates statistical difference from respective isotype and PLGA control (ANOVA, p<0.05) (n=5 independent determinations, mean+s.d.) (D&E) Morphology of DCs cultured on PLGA following isotype (D) or anti-β2 (E) treatment, representative of n=5 determinations. Scale bar denotes 100μm. Brackets in B and C denote statistical difference between groups (ANOVA, p<0.05).

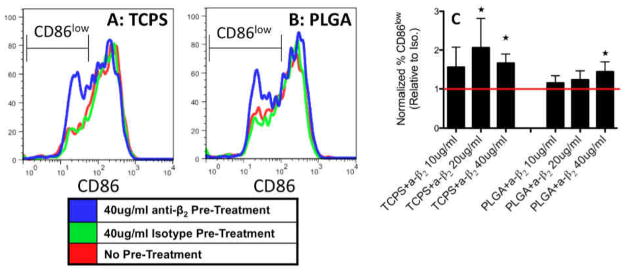

To investigate whether β2-mediated DC adhesion plays a role in biomaterial-induced DC maturation, CD86 expression was also examined in β2-blocked DCs cultured on TCPS or treated with PLGA films. On both substrates, a CD86low population was associated with DCs that were pre-treated with anti-β2, which exemplifies the appearance of immature DCs (Fig. 4A). The percentage of DCs in the CD86low gate (shown in Fig. 4A, B) was normalized to that of isotype controls for each donor and averaged for quantification. With increasing concentrations of anti-β2, DCs became more “immature” as the percentage of CD86low DCs increased for DCs cultured on TCPS or treated with PLGA and particularly at 40μg/mL exhibited significantly higher levels of “immature” DCs on both substrates (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

DC maturation marker (CD86) expression following anti-β2 treatment. Representative (of n=5 determinations) flow cytometry results of DC CD86 expression at 24h treatment on TCPS (A) or PLGA (B) following pre-treatment of 40μg/mL of anti-β2 (blue), isotype (green) or no treatment (red). CD86low gate for PLGA was double that of TCPS since PLGA induces increases in CD86 expression. (C) The percentage of DCs in CD86low gate was determined for each donor and normalized to that of isotype controls for each concentration examined. Star denotes statistical difference from isotype (1), Student T-test p≤0.05 (n=5 independent determinations, mean+s.d).

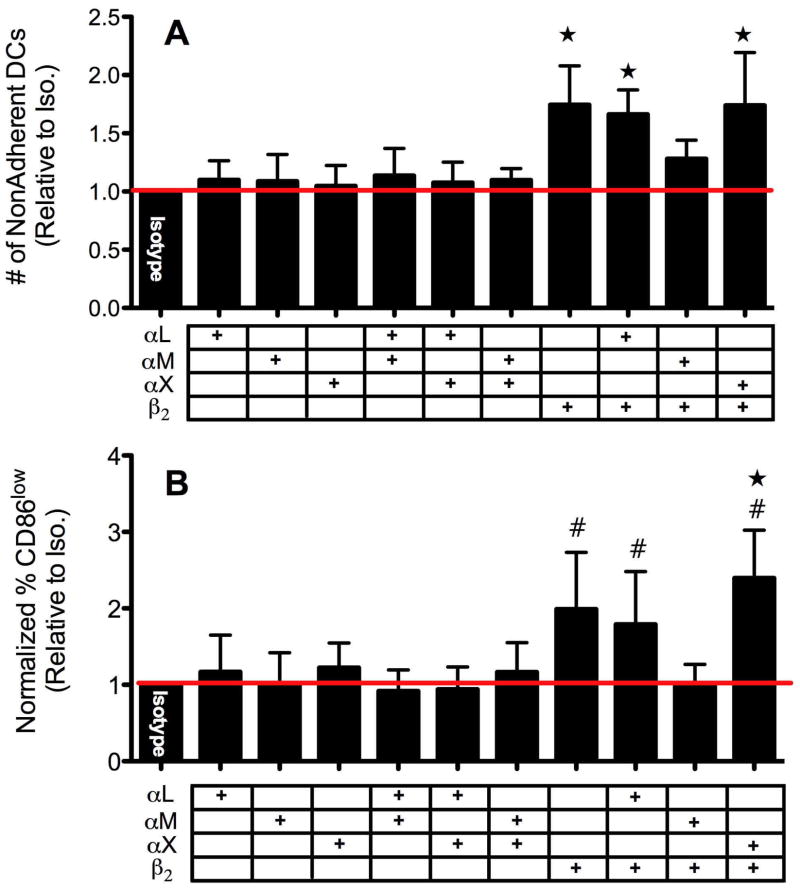

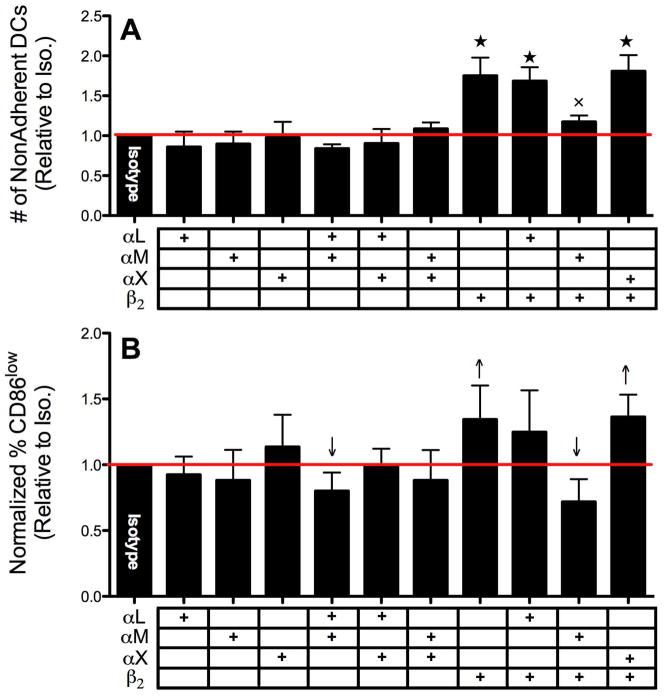

To attempt to identify the α subunit (αL, αM and αX) which pairs with β2 and determine the complete integrin molecule responsible for DC adhesion and activation by biomaterials, antibody-blocking techniques were also explored. Blocking antibodies against αL, αM and αX were used along with anti-β2 and the number of non/loosely-adherent DCs were measured as well as the percentage of CD86low DCs for DCs treated with TCPS or PLGA. For DCs cultured on TCPS, antibodies toward αL, αM or αX alone or in combinations with each other were not able to alter extent of DC adhesion (Fig. 5A). Once again, blocking β2 alone (or in combination with αL or αX) significantly increased the number of non/loosely-adherent DCs (therefore, decreasing the number of adherent DCs) (Fig. 5A). Surprisingly, anti-αM treatment seemed to lessen the inhibitory capacity of anti-β2 to prevent adhesion, which was found to possess similar levels of adhesion to that isotype (Fig. 5A). As expected, the inhibition of DC adhesion to TCPS by β2 antibody-blocking matched the reduction in CD86 expression (Fig. 5B). Dendritic cells pre-treated with antibodies toward αL, αM or αX showed no shift in the percentage of iDCs (CD86low) while DCs pretreated with anti-β2 (or in combination with αL or αX) exhibited a significant increase in the percentage of iDCs (Fig. 5B). Also, the anti-αM pre-treatment, which seemed to prevent anti-β2 from inhibiting adhesion, similarly appeared to reduce anti-β2 lowering in CD86 expression by DCs on TCPS to levels found with isotype. For PLGA treatments, similar results were found in that while α subunit antibody-blocking did not affect adhesion (Fig. 6A) blocking β2 alone, or in combination with αX but not αL, significantly decreased adhesion and simultaneously lowered CD86 expression (Fig. 6A,B). Surprisingly, anti-αM in combination with either anti-αL or anti-β2 showed a slight but significant lowering (compared to isotype) in percentage of CD86low DCs on PLGA which was not found for DCs cultured on TCPS. Overall, while anti-β2 pre-treatment affected adhesion to a similar degree on both TCPS and PLGA films, it was not as effective in lowering CD86 expression in DCs treated with PLGA as for DC cultured on TCPS (Fig. 5B and 6B).

Figure 5.

DC adhesion (A) and maturation (B) level following anti-αL/αM/αX and/or anti-β2 blocking on TCPS. A. Following anti-αL/αM/αX blocking in combination with anti-β2 (each at 20μg/mL) as denoted by table (+) under graph, non-adherent DC counts were collected. Values were normalized for each donor to that of isotype (1), n=8 independent determinations, mean+s.d. B. Following anti-αL/αM/αX blocking in combination with anti-β2 as denoted by table (+) under graph, the percentage of DCs in CD86low gate was determined by flow cytometry and normalized to that of isotype (n=6–8 independent determinations, mean+s.d). Stars for (A) & (B) denote statistical difference from all anti-α combination treatments (ANOVA, p<0.05). # designates statistical difference from isotype (1), Student T-test p≤0.05.

Figure 6.

DC adhesion (A) and maturation (B) level following anti-αL/αM/αX and/or anti-β2 blocking data on PLGA. (A) Following anti-αL/αM/αX blocking in combination with anti-β2 (each at 20μg/mL) as denoted by table (+) under graph, non-adherent DC counts were collected. Values were normalized for each donor to that of isotype (1), n=5–6 independent determinations, mean+s.d. (B) Following anti-αL/αM/αX blocking in combination with anti-β2 as denoted by table (+) under graph, the percentage of DCs in CD86low gate was determined by flow cytometry and normalized to that of isotype (n=5–6 independent determinations, mean+s.d). Stars for (A) denote statistical difference from all lower values (ANOVA, p<0.05). X indicates statistical difference from anti-αL + anti-αM (ANOVA, p<0.05). Arrows for (B) indicates statistically above or below isotype (1), Student t-test p≤0.05.

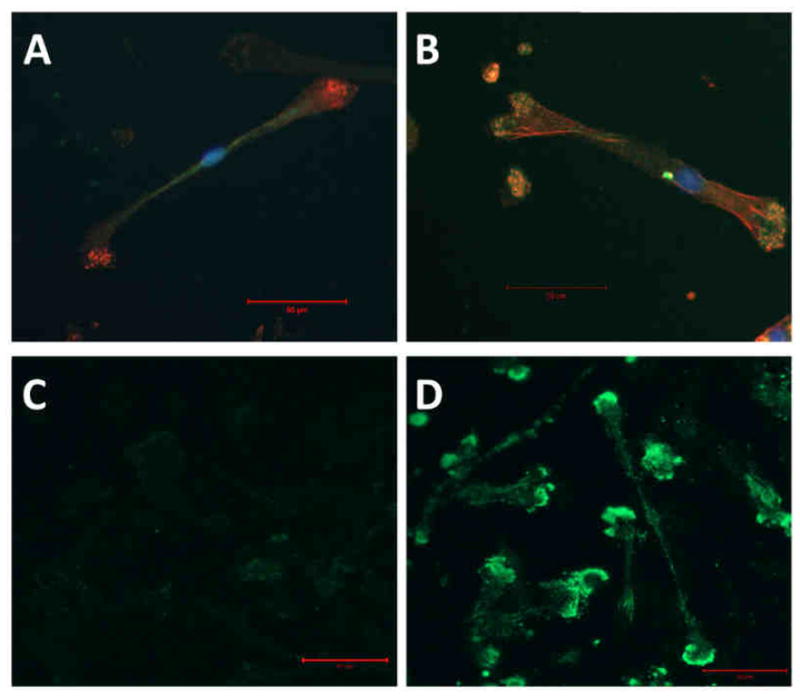

Lastly, to further verify the role of integrins in DC adhesion to biomaterials, both β1 and β2 integrin expression and their direct interaction with PLGA films was visualized on PLGA-adherent DCs using confocal microscopy. As shown in Figure 7, DCs expressed low levels of β1 integrins which did not appear to co-localize with F-actin (Fig. 7A) in DC podosomes. In contrast, co-localization of F-actin with β2 was commonly present in DCs at the sites of adhesion and spreading on PLGA (Fig. 7B). Furthermore, cross-linking adherent DCs to the surface of PLGA and removing non-cross-linked cellular components via an SDS solution showed high-levels of β2 presence at the cross-linked contacts between DCs and PLGA (Fig. 7D). The outlines of DC remnants on PLGA were visible with β2 visualization but are not observed when examining β1 (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7.

β1 vs. β2 integrin expression on DCs adhering to PLGA films. DCs were allowed to adhere to PLGA films for 1.5h and subsequent were fixed, permeabilized and stained with either anti-β1-FITC (A) or anti-β2-FITC (B) both in combination with phalloidin-TRITC (red) and nuclei (green). To examine receptors at DC-biomaterial interface alone, DCs were treated with PLGA films for 1.5h and cross-linked to surface using DTSSP. Non-cross-linked components were then extracted using 0.1% SDS. Polyclonal antibodies (goat) against β1 (C) or β2 (D) were used in combination with anti-goat-FITC secondary to detect integrin presence remaining on films. All films were imaged using confocal microscopy at 40×. Scale bar denotes 50μm. Representative of n=3 determinations.

Discussion

The results presented here illustrate the role and significance of β2 integrins in the recognition and response of DCs to biomaterials. A biomaterial which supports maturation of DCs, such as PLGA, induced up-regulation of integrin adhesion molecules which is in contrast to the response to surfaces that do not support DC maturation such as agarose or TCPS (Fig. 2). This may be related to the increase in DC adhesion, which occurred on PLGA in comparison to TCPS substrate (Fig. 1). Using antibody-blocking techniques, adhesion to both TCPS and PLGA was found to be β2-dependent (Fig. 3B and 3C) and β1-independent (Fig. 3A) which has similarly been shown for monocytes (22). Notably, a role for β2 was found not only in adhesion but also in contributing to determining the state of DC maturation as the percentage of CD86low expressing DCs was significantly increased during β2 antibody blocking of DCs on both TCPS and PLGA substrates (Fig. 4, Fig. 5, & Fig. 6). Biomaterial integrin-mediated adhesion in leukocytes has been established for monocytes/macrophages and neutrophils (22, 24, 32, 39). Particularly, β2 integrins (but not β1) are present on monocytes at early time points (1.5h) during adhesion to biomaterials (22). The current work adds to the field of biomaterials by illustrating the importance of β2 integrins at not only mediating adhesion of DCs to biomaterials but also more importantly contributing to their maturation state.

Possible α-subunits (αL, αM, αX) were also targeted to determine which may pair with β2 to mediate such DC response to biomaterials; however, no subunit examined appeared to affect either adhesion or maturation on TCPS (Fig. 5) or PLGA (Fig. 6). Anti-β2 treatment in combination with anti-(αLor αX) still lowered extent of adhesion and the state of maturation on TCPS (Fig. 5) and on PLGA (Fig. 6). Anti-αM treatment either inhibited or counteracted the effect of anti-β2 and maintained levels of DC adhesion and maturation to that of isotype controls. One possible explanation is that anti-αM may preclude anti-β2 binding through steric hindrance, as noted with flow cytometry for β2 antibody-staining which is somewhat lowered in the presence of anti-αM (Supplementary Fig. 2). This seems likely as anti-αM did not appear to affect DC adhesion or maturation on its own. To assure this, another blocking mAb for αM (clone CBRM1/5, (40)) was also examined and was found to not prevent DC adhesion to TCPS while also inhibiting anti-β2 binding to DCs (data not shown). Though this seems to potentially indirectly link αM to β2-mediated DC adhesion to biomaterials, others have shown that MAC-1 (αMβ2) requires αM for spreading while adhesion is primarily mediated through the β2 subunit (41). Here, anti-αM treatment did not lower the extent of DC spreading on biomaterials though it did induce slight clustering (data not shown).

Interestingly, β1 and β2 mRNA were both up-regulated in DCs treated with PLGA (Fig. 2); however, a role for β1 was not found while utilizing three known β1 blocking monoclonal antibodies (P5D2 as well as JB1A, AIIB2). Dendritic cell adhesion to pFN-coated glass, however, was found to be β1-dependent (Supplemental Fig. 1) as has been previously shown (28) which suggests that DC adhesion to the complex serum-adsorbed surfaces on biomaterials may be β1/FN-independent. The results received through mRNA expression analysis emphasize the need, particularly for integrins, for investigation at the protein level but even further at the cell surface using antibody-blocking or through other techniques such as RNAi. However, it is possible that at times greater than 24h, not studied here, that β1 protein and surface expression becomes relevant. β1 integrin expression has been shown to increase and become a relevant factor in adhesion as biomaterial-adherent monocytes differentiate into macrophages at one week (22). Dendritic cells also have higher levels of expression of β2 than macrophages (26). These may be important and applicable differences between macrophage and DC interactions with biomaterial surfaces. Biomaterials, designed to limit β1-mediated adhesion, may allow for DC presence via β2 but avoid macrophage and foreign-body giant cell accumulation via β1.

It appears that for DCs, β2-mediated adhesion is a requirement for biomaterial-induced maturation. Furthermore, even the less-adhesive and less-activating substrate TCPS may require a basal level of β2 signaling to maintain CD86 expression (Fig. 3B). This is an important finding not only for the biomaterials and tissue engineered device community, but also indicates how DCs in general may utilize integrins to maintain their immunostimulatory capacity. It is accepted that DC adhesion and migration ability is heavily influenced by the maturation state. However, these results indicate there is interplay between adhesion and maturation. Others have found that particular adhesive protein substrates, such as collagen (42) and many others (31), can induce increases in DC stimulation of T cells. In the current work, the biomaterial component is manipulating the DC phenotype through potentially numerous adhesive ligands presented as part of the adsorbed protein layer on biomaterials. Surface chemistry of biomaterials is known to influence protein adsorption and conformation to potentially influence differential cellular integrin engagement at the surface (43, 44). Substrate physical properties such as elasticity and hydrophobicity may contribute to both cellular adhesion and subsequent gene expression by altering the adsorption and presentation of adhesive serum ligands for β2 integrins such as FN or inactive complement component 3b (iC3b) (45, 46). The PLGA 75:25 material used herein is more hydrophobic than TCPS (71.6° (15) versus 59° (47) contact angle, respectively). Others have found that PLGA 50:50 (which has an equivalent contact angle to TCPS, 60° (48)) does not alone induce DC maturation in vitro (49). Thus, hydrophobicity of PLGA 75:25 may explain, in part, why DC adhesion is more prevalent on this composition of PLGA and also potentially why expression levels of CD86 was more difficult to lower for DCs treated with PLGA following β2 blocking than for DCs cultured on TCPS.

The visualization of integrin presence for DCs upon contact with PLGA films was investigated at an early time point (1.5h) to further verify the role of β2 integrins in DC adhesion and spreading on a biomaterial surface. β2 was found in preferentially high levels at podosomes in contact (within 12Å) with biomaterials and co-localized with F-actin (Fig. 7B, D). In contrast, the distribution of β1 was not able to be determined through this cross-linking to PLGA from adherent DCs and was found independent of actin (Fig. 7A, C). The morphology and expression patterns are very similar to what has been found on DC podosomes present when cultured on FN-coated surfaces which exhibit β2, αM, αX and actin co-localization while being absent of β1 (50). Here, the authors did not examine the effect of FN-coating on maturation marker expression, but DCs cultured on FN-coated surfaces did appear at least morphologically similar to DCs treated with PLGA films (Supplemental Fig. 1). While β1 binding to FN is well known (shown in Supplemental Fig. 1), β2 integrins, particularly αMβ2, have also been established as receptors for FN (51). Thus, the β2-mediated adhesion to FN may be one possible ligand present upon serum-adsorption to biomaterials, which may play a role in the adhesive response of DCs. Other ligands for β2-integrins include fibrinogen and iC3b; the former is unlikely to be present in the serum used here for culture and complement activation was prevented by heat inactivation of the serum used here, but activation fragments could have adsorb to the surfaces to mediate recognition.

Lastly, the intracellular link between integrin engagement and DC maturation remains unknown. In monocytes, integrin adhesion to ECM components (such as FN) is known to stimulate nuclear factor (NF)-κB and Jak/STAT signaling pathways (52). The NF-κB pathway plays a particularly important role in inflammatory signaling and, in DCs, controls the expression of numerous DC maturation markers such as CD80 and CD86 (53). The link between DC integrins and NF-κB is less characterized; however, DCs which were treated with PLGA films for 24h, did not show increases in activated NF-κB presence in nuclear extracts (15). This implies that either NF-κB is not involved in DC adhesion-induced maturation or that NF-κB activation occurs earlier than 24h. However, another explanation is that adhesion alone is not enough to activate DCs, and adhesion simply allows for other co-receptors to be localized to biomaterial surface for engagement. As a an example, toll-like receptor (TLR)-4, a PRR which can recognize not only LPS but many proteins such as fibrinogen (54) and induce DC maturation, is one such potential receptor. In fact, TLR4 has been shown to play a role in leukocyte recognition of biomaterials as TLR4-deficient mice display a delayed biomaterial-adherent leukocyte profile (55). Integrin subunit αM (CD11b) has recently been found to negatively regulate TLR triggered inflammatory responses (56); however, the role of other α subunits and β2 in TLR signaling remain unknown. Here, anti-β2 and isotype pre-treated DCs yielded a similar increase in CD86 expression upon treatment with ultrapure-LPS (data not shown), implying β2 inhibition may not have influenced TLR4 responsiveness. In summary, while integrin-mediated adhesion may be required for DC maturation in response to biomaterials, other co-receptors may contribute to the state of DCs in contact with biomaterials.

Conclusions

In summary, we have shown that DC integrin-mediated adhesion to biomaterials plays a role in determining the maturation state of DCs. β2-integrins (but not β1) were involved in DC recognition of both TCPS and PLGA films and blocking β2 lowered the extent of induced maturation of DCs. This has important relevance in determining criteria for material selection in the field of vaccine design and in the field tissue engineering.

Supplementary Material

To assure functionality of the purified anti-β1, the ability to block known β1-mediated DC adhesion to plasma fibronectin (pFN) [28] was tested. Briefly, autoclaved glass cover slips were coated overnight (in 24 well plates) with 10μg/mL human pFN (Sigma) in Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) or HBSS only as negative control. DCs at a concentration of 100,000/mL were then pretreated for 1h with anti-β1 (P5D2) in complete DC media. DCs were then cultured on pFN-coated glass slides for 2h, and non/loosely adherent DC counts were collected and normalized to that collected from glass alone with no pFN-coating (A), mean+s.d. Representative micrographs of n=3 are shown of DCs adhering to pFN in absence of pretreatment (B), pretreated with isotype (C) or anti-β1 (D) antibody. Stars indicate statistical difference between values and glass alone (1), Student t-test, p<0.05. Brackets designate statistical difference between groups, ANOVA p≤0.05 (n=3 independent determinations).

β2 integrin expression on DCs following anti-α and anti-β2 pre-treatments and treatment with PLGA films for 24h. DCs were stained with anti-β2-FITC (TS1/18) and expression levels determined via flow cytometry (GMFI) and normalized to that of isotype control. Star indicates significantly lower β2 staining from that of isotype control, Student t-test, p≤0.05 (n=3–4 independent determinations).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Andres Garcia for his guidance in the cellular cross-linking and immunofluorescence work. Furthermore, the authors acknowledge the support of Todd Rogers with a Cell and Tissue Engineering National Institutes of Health Training Grant (TR, 2T32GM08433-11A1) and Medtronic Supplement (TR, Award Number: 124000007). This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant 1RO1 EB004633-01A1.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–52. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinman RM, Banchereau J. Taking dendritic cells into medicine. Nature. 2007;449:419–26. doi: 10.1038/nature06175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janeway CA, Jr, Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen reconition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124:783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reis e Sousa C. Dendritic cells in a mature age. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:476–83. doi: 10.1038/nri1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mellman I, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells: specialized and regulated antigen processing machines. Cell. 2001;106:255–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00449-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stock UA, Vacanti JP. Tissue engineering: current state and prospects. Annu Rev Med. 2001;52:443–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.52.1.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nerem RM. Tissue engineering: the hope, the hype, and the future. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1143–50. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Babensee J, Anderson JM, McIntire L, Mikos A. Host response to tissue engineered devices. Adv Drug Del Rev. 1998;33:111–39. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(98)00023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Babensee JE. Interaction of dendritic cells with biomaterials. Semin Immunol. 2008;20:101–8. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nerem RM. Cell-based therapies: From basic biology to replacement, repair, and regeneration. Biomaterials. 2007;28:5074–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matzelle M, Babensee J. Humoral immune responses to model antigen co-delivered with biomaterials used in tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2004;25:295–304. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norton LW, Park J, Babensee JE. Biomaterial adjuvant effect is attenuated by anti-inflammatory drug delivery or material selection. J Control Release. 2010;146:341–348. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Babensee J, Paranjpe A. Differential levels of dendritic cell maturation on different biomaterials used in combination products. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2005;74A:503–10. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshida M, Babensee J. Differential effects of agarose and poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) on dendritic cell maturation. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;79A:393–408. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshida M, Mata J, Babensee J. Effect of poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) contact on maturation of murine bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;80A:7–12. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson JM, Rodriguez A, Chang DT. Foreign body reaction to biomaterials. Semin Immunol. 2008;20:86–100. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Springer TA. Adhesion receptors of the immune system. Nature. 1990;346:425–34. doi: 10.1038/346425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plow EF, Haas TK, Zhang L, Loftus J, Smith JW. Ligand binding to integrins. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21785–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R000003200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abram CL, Lowell CA. The ins and outs of leukocyte integrin signaling. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:339–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson JM. Biological responses to materials. Ann Rev Mat Res. 2001;31:81–110. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McNally AK, Anderson JM. Beta1 and beta2 integrins mediate adhesion during macrophage fusion and multinucleated foreign body giant cell formation. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:621–30. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64882-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Annenkov A, Ortlepp S, Hogg N. The beta 2 integrin Mac-1 but not p150,95 associates with Fc gamma RIIA. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:207–12. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis GE. The Mac-1 and p150,95 beta 2 integrins bind denatured proteins to mediate leukocyte cell-substrate adhesion. Exp Cell Res. 1992;200:242–52. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(92)90170-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang L, Ugarova TP, Plow EF, Eaton JW. Molecular determinants of acute inflammatory responses to biomaterials. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1329–34. doi: 10.1172/JCI118549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ammon C, Meyer SP, Schwarzfischer L, Krause SW, Andreesen R, Kreutz M. Comparative analysis of integrin expression on monocyte-derived macrophages and monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Immunology. 2000;100:364–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00056.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCarthy DA, Macey MG, Bedford PA, Knight SC, Dumonde DC, Brown KA. Adhesion molecules are upregulated on dendritic cells isolated from human blood. Immunology. 1997;92:244–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00346.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swetman Andersen CA, Handley M, Pollara G, Ridley AJ, Katz DR, Chain BM. beta1-Integrins determine the dendritic morphology which enhances DC-SIGN-mediated particle capture by dendritic cells. Int Immunol. 2006;18:1295–303. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kohl K, Schnautz S, Pesch M, Klein E, Aumailley M, Bieber T, et al. Subpopulations of human dendritic cells display a distinct phenotype and bind differentially to proteins of the extracellular matrix. Eur J Cell Biol. 2007;86:719–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thacker RI, Retzinger GS. Adsorbed fibrinogen regulates the behavior of human dendritic cells in a CD18-dependent manner. Exp Mol Pathol. 2008;84:122–30. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Acharya AP, Dolgova NV, Clare-Salzler MJ, Keselowsky BG. Adhesive substrate-modulation of adaptive immune responses. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4736–50. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McNally AK, Anderson JM. Complement C3 participation in monocyte adhesion to different surfaces. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:10119–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.10119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoshida M, Babensee J. Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) enhances maturation of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;71A:45–54. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Romani N, Reider D, Heuer M, Ebner S, Kampgen E, Eibl B, et al. Generation of mature dendritic cells from human blood. An improved method with special regard to clinical applicability. J Immunol Methods. 1996;196:137–51. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(96)00078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang X, Seed B. A PCR primer bank for quantitative gene expression analysis. Nucl Acids Res. 2003;31:e154. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–10. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keselowsky BG, Garcia AJ. Quantitative methods for analysis of integrin binding and focal adhesion formation on biomaterial surfaces. Biomaterials. 2005;26:413–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beals CR, Edwards AC, Gottschalk RJ, Kuijpers TW, Staunton DE. CD18 activation epitopes induced by leukocyte activation. J Immunol. 2001;167:6113–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McNally AK, Macewan SR, Anderson JM. alpha subunit partners to beta1 and beta2 integrins during IL-4-induced foreign body giant cell formation. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;82:568–74. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oxvig C, Lu C, Springer TA. Conformational changes in tertiary structure near the ligand binding site of an integrin I domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2215–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Solovjov DA, Pluskota E, Plow EF. Distinct roles for the alpha and beta subunits in the functions of integrin alphaMbeta2. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:1336–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406968200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brand U, Bellinghausen I, Enk AH, Jonuleit H, Becker D, Knop J, et al. Influence of extracellular matrix proteins on the development of cultured human dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:1673–80. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199805)28:05<1673::AID-IMMU1673>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keselowsky BG, Collard DM, Garcia AJ. Surface chemistry modulates fibronectin conformation and directs integrin binding and specificity to control cell adhesion. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;66:247–59. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keselowsky BG, Collard DM, Garcia AJ. Integrin binding specificity regulates biomaterial surface chemistry effects on cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:5953–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407356102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell. 2006;126:677–89. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson CJ, Clegg RE, Leavesley DI, Pearcy MJ. Mediation of biomaterial-cell interactions by adsorbed proteins: a review. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:1–18. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nuryastuti T, van der Mei HC, Busscher HJ, Iravati S, Aman AT, Krom BP. Effect of Cinnamon Oil on icaA Expression and Biofilm Formation by Staphylococcus epidermidis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:6850–5. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00875-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lam CNC, Wu R, Li D, Hair ML, Neumann AW. Study of the advancing and receding contact angles: liquid sorption as a cause of contact angle hysteresis. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2002;96:169–91. doi: 10.1016/s0001-8686(01)00080-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sharp FA, Ruane D, Claass B, Creagh E, Harris J, Malyala P, et al. Uptake of particulate vaccine adjuvants by dendritic cells activates the NALP3 inflammasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:870–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804897106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burns S, Hardy SJ, Buddle J, Yong KL, Jones GE, Thrasher AJ. Maturation of DC is associated with changes in motile characteristics and adherence. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2004;57:118–32. doi: 10.1002/cm.10163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lishko VK, Yakubenko VP, Ugarova TP. The interplay between integrins alpha(M)beta(2) and alpha(5)beta(1), during cell migration to fibronectin. Exp Cell Res. 2003;283:116–26. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Fougerolles AR, Chi-Rosso G, Bajardi A, Gotwals P, Green CD, Koteliansky VE. Global expression analysis of extracellular matrix-integrin interactions in monocytes. Immunity. 2000;13:749–58. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Vliet SJ, den Dunnen J, Gringhuis SI, Geijtenbeek TB, van Kooyk Y. Innate signaling and regulation of Dendritic cell immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:435–40. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rock KL, Kono H. The inflammatory response to cell death. Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3:99–126. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.151456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rogers TH, Babensee JE. Altered adherent leukocyte profile on biomaterials in Toll-like receptor 4 deficient mice. Biomaterials. 2010;31:594–601. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.09.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Han C, Jin J, Xu S, Liu H, Li N, Cao X. Integrin CD11b negatively regulates TLR-triggered inflammatory responses by activating Syk and promoting degradation of MyD88 and TRIF via Cbl-b. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:734–42. doi: 10.1038/ni.1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

To assure functionality of the purified anti-β1, the ability to block known β1-mediated DC adhesion to plasma fibronectin (pFN) [28] was tested. Briefly, autoclaved glass cover slips were coated overnight (in 24 well plates) with 10μg/mL human pFN (Sigma) in Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) or HBSS only as negative control. DCs at a concentration of 100,000/mL were then pretreated for 1h with anti-β1 (P5D2) in complete DC media. DCs were then cultured on pFN-coated glass slides for 2h, and non/loosely adherent DC counts were collected and normalized to that collected from glass alone with no pFN-coating (A), mean+s.d. Representative micrographs of n=3 are shown of DCs adhering to pFN in absence of pretreatment (B), pretreated with isotype (C) or anti-β1 (D) antibody. Stars indicate statistical difference between values and glass alone (1), Student t-test, p<0.05. Brackets designate statistical difference between groups, ANOVA p≤0.05 (n=3 independent determinations).

β2 integrin expression on DCs following anti-α and anti-β2 pre-treatments and treatment with PLGA films for 24h. DCs were stained with anti-β2-FITC (TS1/18) and expression levels determined via flow cytometry (GMFI) and normalized to that of isotype control. Star indicates significantly lower β2 staining from that of isotype control, Student t-test, p≤0.05 (n=3–4 independent determinations).