Abstract

Malaria vaccines, comprised of irradiated Plasmodium falciparum sporozoites or a synthetic peptide containing T and B cell epitopes of the circumsporozoite protein (CSP), elicit multifunctional cytotoxic and non-cytotoxic CD4+ T cells in immunized volunteers. Both lytic and non-lytic CD4+T cell clones recognized a series of overlapping epitopes within a ‘universal’ T cell epitope EYLNKIQNSLSTEWSPCSVT of CSP (NF54 isolate) that was presented in the context of multiple DR molecules. Lytic activity directly correlated with T cell receptor (TCR) functional avidity as measured by stimulation indices and recognition of naturally occurring variant peptides. CD4+ T cell-mediated cytotoxicity was contact-dependent and did not require de novo synthesis of cytotoxic mediators, suggesting a granule-mediated mechanism. Live cell imaging of the interaction of effector and target cells demonstrated that CD4+ cytotoxic T cells recognize target cells with their leading edge, reorient their cytotoxic granules towards the zone of contact, and form a stable immunological synapse. CTL attacks induced chromatin condensation, nuclear fragmentation and formation of apoptotic bodies in target cells. Together, these findings suggest that CD4+ CTLs trigger target cell apoptosis via classical perforin/granzyme-mediated cytotoxicity, similar to CD8+ CTLs, and these multifunctional sporozoite- and peptide-induced CD4+ T cells have the potential to play a direct role as effector cells in targeting the exoerythrocytic forms within the liver.

Keywords: Malaria, Vaccine, CTL, Perforin, Granzymes, Apoptosis, Immunological synapse, Cytotoxic granule, Live cell imaging

1. Introduction

After transmission by the bite of an infected mosquito, Plasmodium sporozoites travel from the skin to the liver, their first site of replication in the mammalian host (Vanderberg and Frevert, 2004; Amino et al., 2005). Once arrested within a hepatic sinusoid, the parasites leave the bloodstream by traversing Kupffer cells, migrate through the parenchyma of the liver, infect hepatocytes and grow to exoerythrocytic forms (EEF) (Ishino et al., 2004; Frevert et al., 2005; Baer et al., 2007b; Usynin et al., 2007). Eventually, each infected hepatocyte releases thousands of erythrocyte-infective merozoites, which begin the cycle of blood stage infection, thus initiating the clinical phase of the disease (Sturm et al., 2006; Baer et al., 2007a).

The circumsporozoite protein (CSP), the major surface antigen of the sporozoites, has been the focus of malaria vaccine development because of its immunodominance and presence in both the sporozoite and EEF stage of Plasmodium (Kumar et al., 2006). Extensive studies over the past 30 years demonstrated that both sporozoite neutralizing antibodies and cell-mediated immunity directed against infected hepatocytes, contribute to sporozoite-induced immunity (Nardin and Nussenzweig, 1993). Based on data from a variety of rodent models, CD8+ T cells are generally regarded as the principal cytotoxic effector cells, while CD4+ T cells provide T helper factors required for memory CD8+ T cell and optimal antibody responses (Romero et al., 1989; Molano et al., 2000; Carvalho et al., 2002; Doolan and Martinez-Alier, 2006). However, in the absence of CD8+ cells, CD4+ T cells can also provide direct protective immunity in both sporozoite and peptide-immunized animals (Romero et al., 1989; Tsuji et al., 1990; Rénia et al., 1991; Rénia et al., 1993; Wang et al., 1996; Charoenvit et al., 1999; Oliveira et al., 2008).. One major protective mechanism is dependent on IFN-γ, a cytokine produced by both CD4+ and CD8+ cells, which induces nitric oxide (NO) production in infected hepatocytes thus killing the intracellular parasites (Ferreira et al., 1987; Schofield et al., 1987; Mellouk et al., 1991; Seguin et al., 1994).

Classical granule-mediated cytotoxicity is essential for protection in some murine malaria models (Doolan and Hoffman, 2000). In other infectious diseases, human CD4+ CTLs, as well as CD8+ CTLs, have been shown to develop during viral, bacterial and fungal infections and following immunization (Miskovsky et al., 1994; Zaunders et al., 2004; Aslan et al., 2006; Casazza et al., 2006; Mitra-Kaushik et al., 2007; Bastian et al., 2008; Leen et al., 2008). There is currently little information available about the interaction between Plasmodium-specific human CTLs, either CD4+ or CD8+, and their target cells.

CTLs utilize a granule exocytosis pathway for target cell killing (Russell and Ley, 2002; Catalfamo and Henkart, 2003; Clark and Griffiths, 2003; Lieberman, 2003; Trapani and Sutton, 2003). Cytotoxic granules are secretory lysosomes that store many of the apoptosis-inducing molecules including the pore-forming proteins perforin and granulysin, various serine proteases named granzymes, and the death receptor ligand FasL in their distinctive dense core (Peters et al., 1991; Clark and Griffiths, 2003). Under resting conditions, CD8+ CTLs are polar cells with an organelle-free leading edge and a tapered uropod containing the cytotoxic granules (Yannelli et al., 1986; Ng et al., 2008). Within minutes of specific antigen/human leukocyte antigen (HLA) complex recognition, primed CD8+ CTLs round up and form a tight junction or immunological synapse with the target cell (Kupfer and Singer, 1989; Faroudi et al., 2003; Depoil et al., 2005; Dustin, 2005; Wiedemann et al., 2006). Intracellular signaling causes the microtubule organizing center (MTOC), Golgi complex, and cytotoxic granules to migrate vectorially along the microtubule network towards the site of contact (Yannelli et al., 1986; Kuhn and Poenie, 2002; Trambas and Griffiths, 2003; Dustin, 2005, 2006). Immediately upon completion of reorientation, one or more of the granules rapidly fuse with the cell membrane and discharge their lethal content into the narrow gap between CTL and target cell. The fatal hit is delivered either via secretion of perforin and granzymes, which require active collaboration of the target cell for induction of apoptosis (Keefe et al., 2005; Pipkin and Lieberman, 2007), or via release of Fas ligand (FasL), which causes the apoptotic death of cells expressing Fas on their surface (Berke, 1995). The perforin/granzyme pathway, rather than the Fas/FasL pathway, is essential for the clearance of many intracellular pathogens (Russell and Ley, 2002).

The first evidence for human CD4+ T cells with cytotoxic properties directed against a protozoan parasite came from class II-restricted T cells isolated from a sporozoite-immunized volunteer, who was protected against challenge with Plasmodium falciparum sporozoites for at least 1 year (Moreno et al., 1991). Herein we demonstrate that additional clones from sporozoite-immunized volunteers are able to lyse autologous B cells pulsed with the T* peptide (EYLNKIQNSLSTEWSPCSVT) in the context of HLA-DR 4, 7 and 9. In addition, cytotoxic CD4+ T cells that can specifically recognize autologous target cells pulsed with T* peptide were also isolated from volunteers immunized with a (T1BT*) peptide vaccine containing the T* epitope. Upon activation, these cytotoxic subsets of both sporozoite and peptide induced CD4+ T cell clones, which have the phenotype of memory T cells (Moreno et al., 1993b; Calvo-Calle et al., 2005), were shown to express perforin and release serine esterases. These CD4+ CTLs form typical immunological synapses with peptide-primed target cells and induce apoptosis. Together, our findings suggest that in addition to their indirect role as helper cells in the humoral immune response against sporozoites (Molano et al., 2000), multifunctional CD4+ T cells have the potential to eliminate EEFs from the infected liver through direct effector mechanisms, similar to CD8+ T cells. This work provides the basis for more detailed spatial and temporal analysis of the interaction between cytotoxic T cells and the malaria-infected liver.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Human CD4+ T cell lines and clones

The CD4+ T cell clones have been described in detail previously and were established either from protected volunteers immunized with irradiated P. falciparum sporozoites (Moreno et al., 1991; Moreno et al., 1993a) or volunteers immunized with (T1BT*)4-P3C malaria peptide vaccine containing immunodominant T and B cell epitopes of the P. falciparum CSP (Moreno et al., 1991; Moreno et al., 1993a; Nardin et al., 2001; Calvo-Calle et al., 2005). Sporozoite-induced clones were isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells PBMC obtained 20 days after volunteers resisted challenge with P. falciparum sporozoites. Peptide-induced clones were established 10 months after final immunization (T1BT*)4-P3C (day 373). PBMC were expanded in vitro with the T* peptide, EYLNKIQSLSTEWSPCSVT (amino acid (aa) 326–345 NF54 isolate, GenBank accession AAA29527), which contains overlapping T cell epitopes recognized in the context of multiple class II molecules (Calvo-Calle et al., 1997). After a single in vitro expansion with peptide, the cells were cloned in the presence of PHA-P (Difco, Detroit, MI), recombinant IL-2 (Hoffman-La Roche, Nutley, NJ) and allogeneic irradiated PBMC as feeder cells. After screening for reactivity, positive clones were maintained in medium containing recombinant human IL-2 (rIL-2) and were re-stimulated with phytohemagglutinin (PHA) and allogeneic cells every 3–4 weeks. The clones recognize the T* epitope in the context of multiple HLA DR and DQ molecules (Moreno et al., 1993a; Calvo-Calle et al., 2005).

2.2. Target cells

HLA class II homozygous or autologous Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) transformed human B cells were used as antigen-presenting target cells. Target cells were pulsed overnight with 10 μg/ml of the T* peptide EYLNKIQNSLSTEWSPCSVT from the P. falciparum NF54 isolate or a polymorphic variant peptide from Brazil and Thailand isolates which contains three aa substitutions (underlined), K--KR (GenBank accession AAA29516) (Moreno et al., 1993a). In live cell imaging studies, peptide was added prior to or during the confocal imaging of mixed effector/target cell cultures.

2.3. Cytokine Assays

Supernatants were collected from cultures containing 2 × 104 T cells and 1 × 104 irradiated homozygous EBV-B cells in the presence of various peptide concentrations or medium only. IL-2 was measured in 24 h supernatants using a bioassay based on stimulation of the IL-2-dependent T cell line CTLL-2 (Gillis et al., 1978). The results are expressed as stimulation index [S.I. = mean cpm in wells containing supernatants from peptide-stimulated T cells/mean cpm in medium treated control wells].

2.4. Cytotoxicity assays

Chromium release assays were carried out by labeling peptide-pulsed target cells for 1 h with 120 μCi of Na251CrO4 (ICN Biomedical Inc., Irvine, CA). After washing, 1 × 104 cells each were added to duplicate wells of round-bottom microtiter plates (Corning, NY). T cells were added at different effector-to-target cell (E:T) ratios and the plates were incubated for 4 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. The supernatants were assayed for 51Cr release using an LKB 1260 Multigamma II gamma counter. Specific cytotoxicity was calculated as percent specific lysis [= (experimental release − spontaneous release)/(total release − spontaneous release) × 100]. No lysis was observed in a bystander 51Cr release assay, in which lytic T cells and peptide-pulsed matched DR EBV-B cells were co-incubated with labeled mismatched DR EBV-B cell lines, indicating that target cell lysis was contact dependent.

2.5. JAM assay

For detection of target cell DNA fragmentation, EBV-B cells were incubated with 10 μg/ml peptide and pulsed with 5 μCi/ml 3H-thymidine (ICN Biomedical Inc.). After overnight incubation, the cells were irradiated (2,500 rad), washed and added to round-bottom microtiter plates at a concentration of 1× 104 cells/well. T cells at different E:T ratios were added and the plates were incubated for 12 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were harvested on TomTeK Mach II and labeled DNA bound to glass fiber filters was measured by scintillation counting. Because fragmented DNA fails to bind to the filter, the reduction in cpm in the presence of effector T cells reflects DNA fragmentation (Matzinger, 1991; Hoves et al., 2003). Specific cytotoxicity was calculated as percent reduction in 3H-thymidine incorporation [= (total incorporated label in absence of effector cells − experimentally retained DNA in presence of effector cells) / total incorporated label in absence of effector cells × 100].

2.6. Effect of metabolic inhibitors on cytolytic activity

Effector T cells were preincubated with metabolic inhibitors at different concentrations for 45 min., washed twice and then added to peptide-pulsed 51Cr labeled target cells for cytotoxicity assay, or to 3H-thymidine-pulsed target cells for the JAM assay. The inhibitors included cyclosporin A (0.12–2 μg/ml) (Sandoz, Basel, Switzerland), cycloheximide (0.25–4 μg/ml) (Sigma), and actinomycin D (0.03–0.5 μg/ml) (Sigma). These inhibitors blocked IL-2 production in a dose-dependent manner (data not shown), but were not toxic to the cells (Ju et al., 1990) and did not increase the spontaneous release of radiolabel from the target cells.

2.7. Detection of cytolytic granule contents perforin and serine protease

Immunohistochemical staining for perforin was carried out using a monoclonal antibody (MAb) specific for human perforin, which was kindly provided by Dr. Y. Shinkai, as described (Kawasaki et al., 1990). Cytocentrifuge slide preparations of cytolytic and non-cytolytic T cell clones were fixed for 3 min with cold acetone and for 1 min with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. After rinsing with 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, the slides were treated with 0.5% periodic acid for 10 min and 0.3% H2O2. After rinsing with Tris buffer, the slides were blocked for 30 min with PBS containing 1% BSA and sequentially incubated with the MAb, goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to biotin, ABC Vectastain, and developed with diaminobenzidine (all from Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA).

In addition, peptide-induced lytic and non-lytic clones were stained for intracellular perforin and analyzed by flow cytometry. The cells were first washed, resuspended in cold PBS and then fixed and permeabilized using Cytofix/Cytoperm 15 min, 4°C in the dark according to the manufacturer’s protocol (BD Pharmingen). Fixed and permeabilized cells were stained with a MAb specific for human perforin or isotype control (BD Pharmingen) at room temperature, 30 min in the dark and then analyzed on a FACSCalibar using CellQuest.

Staining for granule-associated serine proteases was done on cytospin slides in which 200 μl aliquots of cell suspension (3 × 105 cells/ml) were added to each well of a Shandon Cytospin 3 cytocentrifuge (Pittsburgh, PA) and spun at 700 rpm for 10 min (Wagner et al., 1993). Slides were dried and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 1 min and rinsed with PBS. Serine protease staining was performed by incubation for 10 min at 37°C with 2 × 10−4 M of the substrate N, α-benzyloxycarbonyl-L-lysine thiobenzyl ester (BLT; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in 0.2 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.1 containing 0.2 mg/ml Fast Blue BB (Sigma). After incubation, excess stain was removed by rinsing with tap water and the cells were counterstained with Harris’ haematoxylin.

Serine esterase activity was also measured in supernatants of activated T cell clones stimulated with anti-CD3- MAb or peptide-pulsed EBV-B cells. The activity was determined by adding 30 μl of sample supernatant to 170 μl of 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, containing 1 mM EDTA, 220 μM 5,5′-dithio-bis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid), and 200 μM N-benzyloxycarbonyl-L-lysine thiobenzyl ester (BLT) (all from Sigma) as a substrate solution. After incubation at room temperature for 40 min, the O.D. was read at 405 nm. Clones cultured in the absence of anti-CD3, or with EBV-B cells without peptide, did not secrete detectable serine esterase and were used as blank control. The results are expressed as percent increase of activity [= (O.D. in stimulated cultures − O.D. in blank control) / O.D. in stimulated cultures × 100].

2.8. Transmission electron microscopy of lytic CD4+ T cells

Cytolytic (DR7-M2B10) or non-cytolytic (DR7-1D2, DR7-1C8) CD4+ T cell clones were incubated at 37°C with or without EBV-B target cells in the presence or absence of 10 μg/ml T* peptide for 30 min, 3 h or 6 h. Aliquots of these effector-target cell suspensions were fixed with 1% glutaraldehyde and 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and embedded in Epon (Baer et al., 2007a). Ultrathin sections were cut with a RMC MT-7 ultramicrotome, photographs were taken with a Zeiss EM 910 transmission electron microscope.

2.9. Live cell imaging of T cell interaction with target cells

To visualize the dynamics of the interaction between cytotoxic cells and target cells, the lytic CD4+ T cell clones DR4-W2F9 (Moreno et al., 1993a) or DR4-65 (Calvo-Calle et al., 2005) were first loaded with 100 nM LysoTracker Green or 1 μM LysoTracker Red (Molecular Probes) to label the lysosomal cytotoxic granules, and the cell surface was labeled with 50 μM FM 4-64 FX (Molecular Probes). In additional studies, Cy5-conjugated TFL4 provided by the CyToxiLux kit (OncoImmunin, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD), when used according to the instructions of the manufacturer, sequestered to lysosomes and was used as another marker for cytotoxic granules to label the CD4+ T cell clones.

Target cells were loaded with 7.3 μM CellTracker Red CMTPX or 1 μM CellTrace Calcein Green AM (Molecular Probes). To facilitate in vitro examination, target cells were immobilized by pretreatment of the cover glass with 1% Alcian blue (Frevert and Reinwald, 1988). After target cell attachment, the supernatant was replaced by complete medium containing 100 U/ml rIL-2.

Glass-bottom dishes with immobilized target cells were examined with a Leica TCS SP2 AOBS confocal microscope equipped with a temperature- and CO2-controlled Ludin chamber. After acquisition of control data, target cells were exposed to CD4+ T cells and in the presence or absence of added peptide. Time series or three-dimensional stacks were recorded using 488 nm excitation for CellTrace Calcein Green and LysoTracker Green, 594 nm for CellTracker Red and LysoTracker Red, and 633 nm for TFL-4. Leica Confocal Software (version 2.61 Build 1537), Image-Pro Plus (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD) and AutoDeBlur software (AutoQuant Imaging, Inc.) were used for image analysis and deconvolution. Individual cells were monitored for fluorescence emission using ImageJ software.

3. Results

3.1. Sporozoite-induced CD4+ CTL clones

A series of CD4+ T cell clones were derived from three sporozoite-immunized volunteers by stimulation of their immune PBMC with peptide representing the T* epitope of P. falciparum CSP (NF54 isolate; aa 326–345). These CD4+ T cell clones proliferate when stimulated with T* peptide in the context of the multiple class II molecules, DR 1, 4, 7 or 9 (Moreno et al., 1993a). Consistent with previous observations using a DR7 restricted CTL clone derived from one of the sporozoite immunized volunteers (Moreno et al, 1991), CD4+ T cell clones from all three volunteers were capable of lysing peptide-pulsed target cells. In a 51Cr release assay, the DR9 restricted AC2F9 clone (DR9-A2F9), DR7 restricted 2B10 clone (DR7-M2B10), DR1 restricted 1B11 clone (DR1-1B11) and DR4 restricted DW2F9 clone (DR4-W2F9), expressed variable levels of lytic activity when incubated with peptide-pulsed EBV-B target cells (Fig. 1A). Cytotoxic responses were HLA-restricted and peptide-specific, i.e. no specific lysis occurred in the absence of peptide or when peptide was presented by APC lacking the appropriate class II molecule (data not shown). The same class II genetic restrictions and fine epitope specificity could be found in both lytic and non-lytic DR-7 restricted clones, which both recognize the SLSTEWSPC epitope within the T* sequence, indicating that unique T cell receptor (TCR), rather than specific epitope, function in lytic effector cells (data not shown).

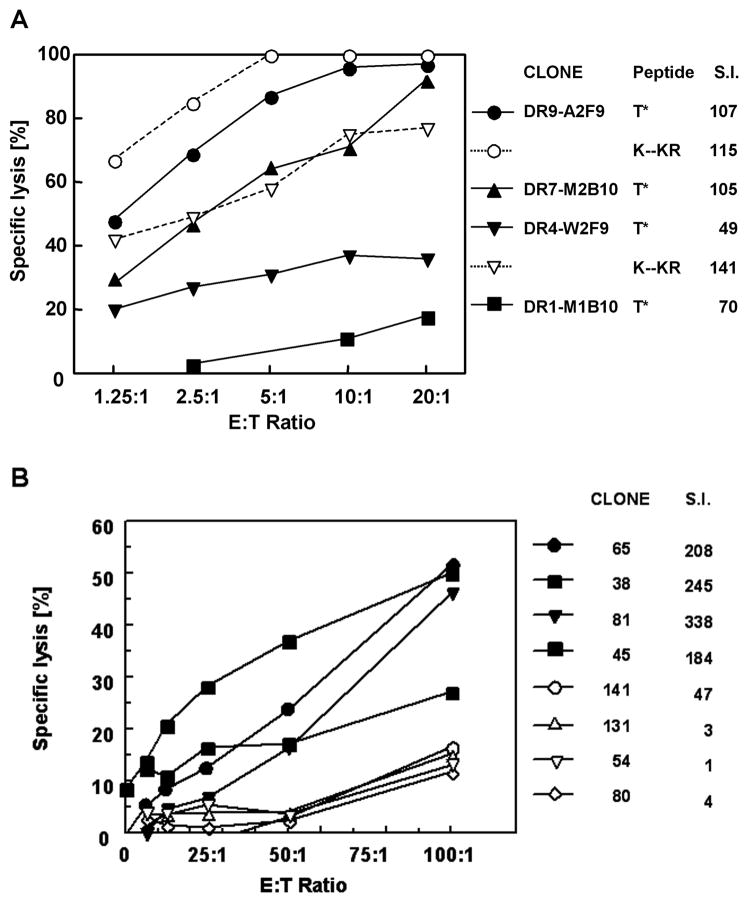

Fig. 1.

Lytic activity of the CD4+ T cell clones. Each clone is represented by a different symbol. A) Specific lysis of 51Cr labeled EBV target cells co-cultivated at the indicated E:T ratios with sporozoite-induced CD4+ T cell clones. Target cells were pulsed with a 20mer T* NF 54 peptide containing the sequence EYLNK (solid symbols and lines) or with the corresponding 20mer variant peptide derived from isolates from Brazil and Tanzania which differs at the underlined aa KYLKR (open symbols and dotted lines). Stimulation indices (S.I.) are shown for each clone as measured in culture supernatants using an IL-2 dependent bioassay. The K--KR peptide stimulated similar levels of proliferation and lytic activity in clone DR7-M2B10 as the T* NF54 peptide and did not stimulate the DR1-M1B10 clone (data not shown for clarity). B) Specific lysis of T* peptide-pulsed target cells induced by DR4 restricted CD4+ T cell clones isolated from volunteers immunized with the (T1BT*)4 peptide. Corresponding cytokine levels in culture supernatants, shown as S.I., were measured in IL-2 bioassay.

The DR7 and DR9 restricted clones exhibited the highest levels of lytic activity against T* peptide-pulsed EBV targets, with a range of 60–90% lysis at a effector-to-target cell (E:T) ratio of 10:1 (Fig. 1A). The DR4 restricted T cell clone gave 30% lytic activity and the DR1 restricted T cell clones were unable to lyse T* peptide-pulsed autologous EBV-B target cells at any of the E:T ratios tested. The DR1 and DR7 restricted clones were derived from the same sporozoite immunized volunteer, indicating that both lytic and non-lytic cells restricted by different class II are present in the same donor at the same time point.

The avidity of peptide-TCR interaction was a key determinant of lytic activity. When the clones were tested with the variant peptide K--KR, higher levels of lysis were obtained in the DR4 restricted clone (Fig. 1A). The variant peptide stimulated DR4-W2F9 CTLs to 60% killing of target cells, versus 35% with the NF54 T* peptide sequence. This heterocyclic response was specific for the individual clone, as significant enhancement of lytic activity was not observed with the DR7 or DR9 restricted clones. This heterocyclic response was also noted in the proliferative activity of the clones. Stimulation of the DR4 restricted clone with the K--KR variant peptide elicited a S.I. of 141, as compared to 49 S.I. with the NF54 peptide. As with lytic activity, enhanced proliferation was specific for the unique TCR of the DR4-W2F9 clone, as significant increase in S.I. not found when variant peptide was used to stimulate the DR9-A2F9 clone.

3.2. Peptide-induced CD4+ T cell clones

Volunteers immunized with the T1BT* synthetic peptide vaccine, containing the P. falciparum CSP repeats combined with the T* universal epitope, also developed CD4+ T cell responses specific for the T* epitope (Nardin et al., 2001). A series of DR4 restricted T cell clones derived from one of these volunteers (vol. 09) were found to be cytotoxic (Fig. 1B). As found with sporozoite induced clones, both lytic and non-lytic cells were present in the same donor at the same time point (Day 373, 10 months after the final immunization). Similar also to sporozoite-induced clones, both lytic and non-lytic clones used the same restriction element (DRB1*0401) for recognition of the same core epitope (SLSTEWSP) within the T* sequence. Although the same core epitope was recognized by all of the clones, TCR were encoded by multiple Vβ families including VB2, 3, 9, 14 and 18 indicating independent origins of each clone (Calvo-Calle et al., 2005). This core epitope overlapped, but was distinct from the core epitopes recognized by the cytolytic sporozoite-induced T cell clones restricted by DR9 (LNKIQNSLSTEW), DR7 (SLSTEWSPC) or DR4 (EYLNKIQSLSTEW) class II molecules (Moreno et al., 1993a). These clonal fine specificities indicate that lytic activity was not dependent on interaction of TCR with a unique core epitope within the T* epitope.

As found with sporozoite induced clones, CTL activity correlated with high S.I.s of the T cell clones (Fig. 1B). In dose response assays, there was a positive correlation between the peptide concentration required to stimulate lytic activity and IL-2 production (r = 0.833), where lowest doses (0.05 – 0.1 μM) were required for stimulation of highly lytic cells compared with 4 μM for non-lytic clones. At a given antigen concentration, the highly lytic CD4+ T cell clones from both the sporozoite-vaccinated and the peptide-immunized volunteers had higher S.I.s compared with the non-lytic clones (Fig. 1A and B). Together, these findings indicate that lytic activity correlated with high peptide:TCR avidity (Rees et al., 1999).

3.3. CD4+ CTL mediated nuclear alterations in target cells

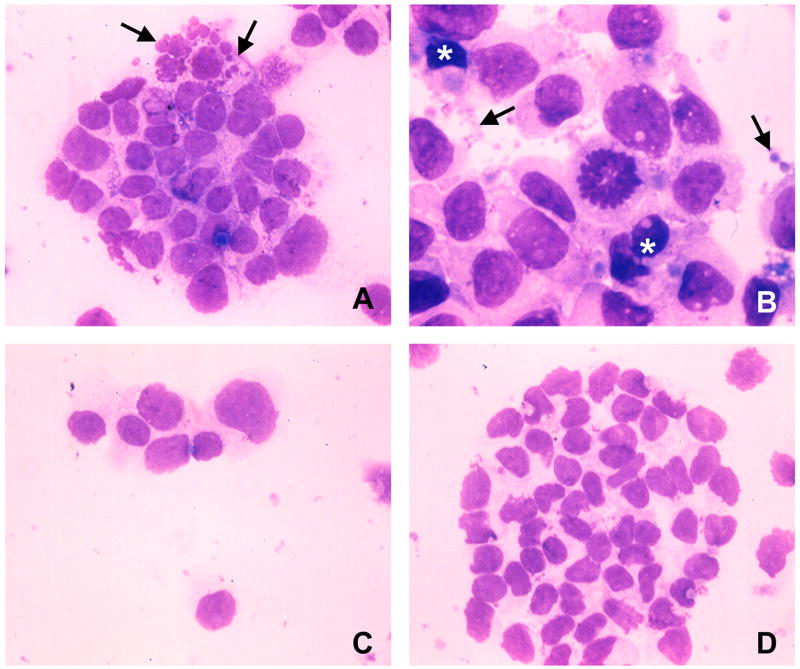

Giemsa staining presented morphological evidence for apoptotic target cell death. Peptide-pulsed target cells harvested 2–4 h after incubation with the sporozoite-induced CD4+ CTL clone DR7-M2B10 exhibited chromatin condensation, nuclear blebbing and formation of apoptotic bodies (Fig. 2A and B). No nuclear alterations were detected in EBV-B cells in the absence of peptide (Fig. 2C), or in peptide-pulsed target cells exposed to the non-cytotoxic T cell clone DR7-1C8 (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

CD4+ cytotoxic T cell (CTL) attack causes nuclear alterations. Giemsa staining of cytospin preparations of E:T preparations. A) After exposure to the cytotoxic CD4+ CTL clone DR7-M2B10 for 2 h, peptide-pulsed EBV-B cells exhibit nuclear fragmentation (arrows). B) After 4 h exposure, peptide-pulsed target cells contain condensed nuclei (*), exhibit membrane blebbing and formation of apoptotic bodies (arrows). No nuclear or cell membrane alterations were found in EBV-B cells co-cultivated with CD4+ CTL in the absence of peptide (C) or in peptide-pulsed target cells exposed to the non-cytotoxic clone DR7-1C8 (D).

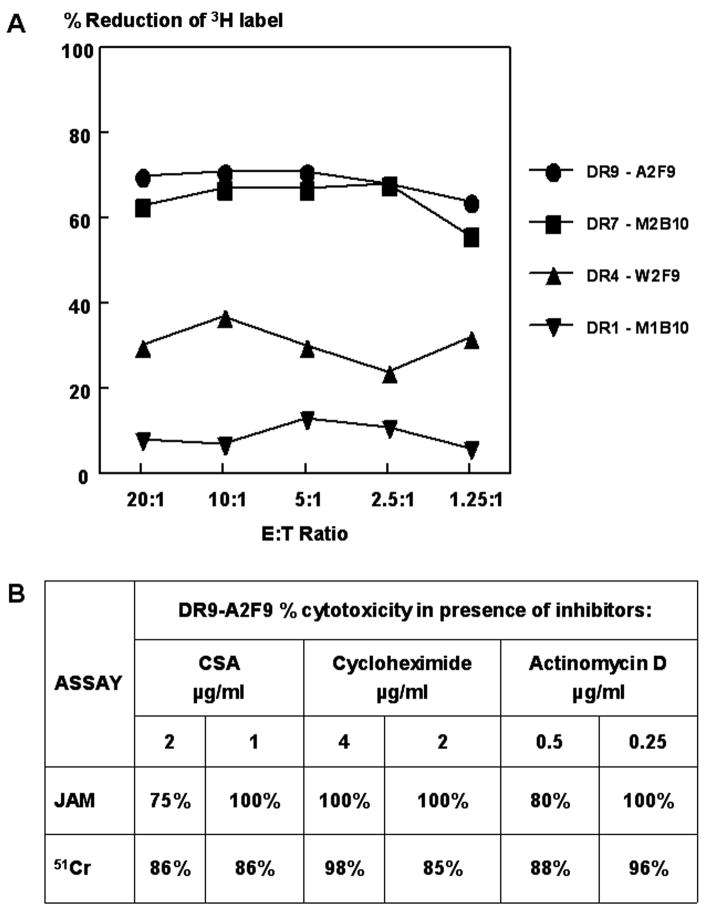

Nuclear degradation was also detected using a JAM assay. This assay measures DNA fragmentation in 3H-Tdr labeled target cells as reflected in reduction of 3H-labelled nuclear material binding to glass filters after cell harvesting (Matzinger, 1991; Hoves et al., 2003). The 51Cr release assay requires loss of membrane integrity and therefore detects only late apoptotic cells. The JAM assay revealed DNA degradation, shown as the percentage of reduction in 3H-label, in peptide-pulsed EBV-B cells incubated with cytotoxic, but not non-cytotoxic CD4+ T cell clones after 12 h of incubation (Fig. 3A). No DNA degradation was observed in target cells in the absence of peptide, or in peptide-pulsed target cells in the absence of T cells.

Fig. 3.

CD4+ cytotoxic T cell (CTL)-mediated DNA fragmentation of target cells. A) Sporozoite-induced CD4 + T cell clones that were shown in the 51Cr cytotoxicity assay to have lytic activity that was high (clones DR9-A2F9, DR7-M2B10), intermediate (DR4-W2F9) or non-lytic (DR1-M1B10) were tested in the JAM assay. T cells and H3-Tdr labeled peptide-pulsed target cells were incubated at the indicated E:T ratios. Results are expressed as the percentage reduction in the amount of labeled DNA recovered from peptide-pulsed target cells harvested on glass filters compared to target cells without peptide. B) Clone DR9-A2F9 was incubated with metabolic inhibitors cyclosporin A (CSA), cycloheximide, or actinomycin D prior to JAM or 51Cr assay. Results shown for concentration of inhibitors that blocked 100% of IL-2 production by the clone. The percentage of cytotoxicity observed in presence of inhibitors relative to the percentage of cytotoxicity in the absence of inhibitors is shown.

The pattern of DNA degradation amongst the different clones was the same as detected by the 51Cr release assay. Cells with high levels of cytotoxicity in the 51Cr release assay had high levels in the JAM assay (Fig. 3B). These results, together with the morphological changes observed in Giemsa stained target cells, suggest that CD4+ CTLs trigger apoptosis in peptide-primed autologous target cells.

3.4. Cytotoxic effector molecules are preformed in CD4+ CTLs

Metabolic inhibitors, such as the translation inhibitor cycloheximide, the transcription inhibitor actinomycin D and cyclosporine A, an inhibitor of lymphokine transcription, have been shown to block lytic activity mediated by CD8+ T cells (Ju et al., 1990). These inhibitors had no effect on the specific cytotoxicity of CD4+ T cell clones, in either the JAM assay or 51Cr release assay (Fig. 3B), when used at concentrations that totally blocked the production of IL-2 by the T cells. The finding that de novo protein synthesis of cytotoxic mediators was not required for CD4+ T cell cytotoxicity is consistent with the notion that lytic effector molecules are preformed, as in the granule-mediated cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells. Upon CD8+ CTL attack, perforin and granzymes, lytic mediators that are stored in the cytotoxic granules (Vergelli et al., 1997; Russell and Ley, 2002; Clark and Griffiths, 2003; Trapani and Sutton, 2003; Grossman et al., 2004), are released and the serine esterases traffic rapidly to the target cell nucleus where they activate caspases leading to DNA fragmentation, chromatin condensation and apoptosis (Leist and Jaattela, 2001; Russell and Ley, 2002; Trapani and Sutton, 2003; Harwood et al., 2005).

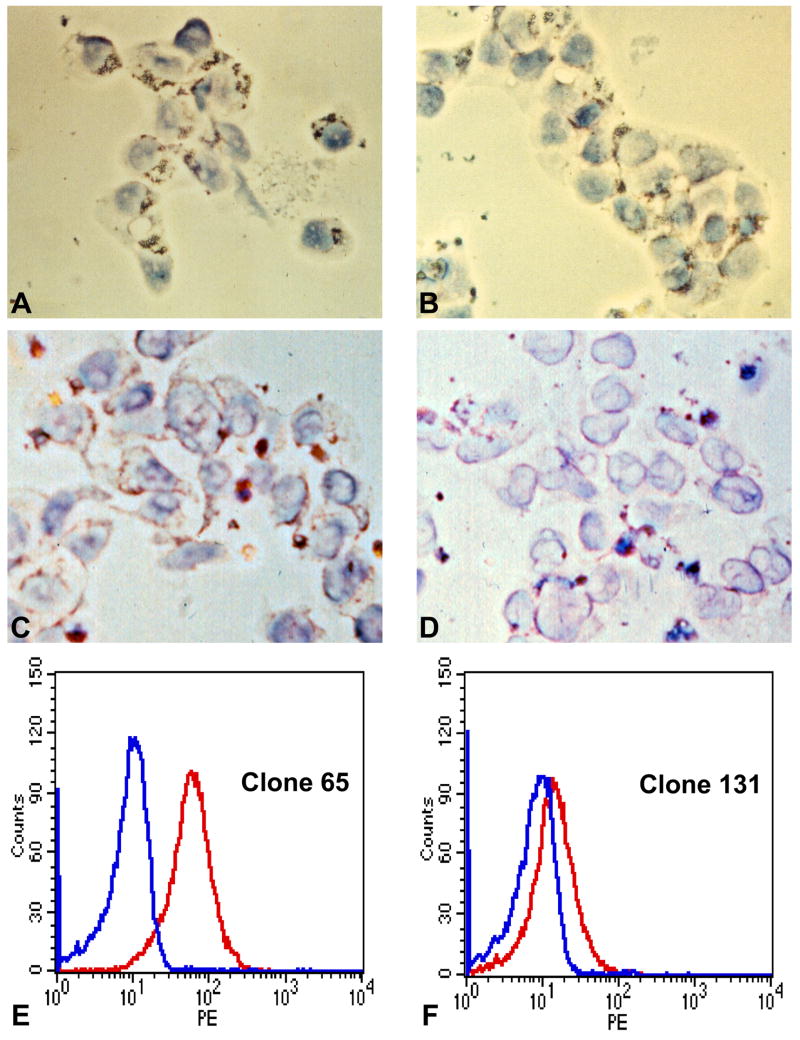

We therefore analyzed the CD4+ T cell clones for the presence of perforin and granzymes typical of cytotoxic granules. Immunocytochemical staining of the sporozoite-induced CD4+ T cell clones detected serine esterases in the cytoplasm of both cytotoxic and non-cytotoxic CD4+ T cell clones (Fig. 4A and B). In vitro, target cell conjugation typically causes CTLs to release granzymes into the culture supernatant (Pasternack et al., 1986; Takayama and Sitkovsky, 1987; Catalfamo and Henkart, 2003; Lieberman, 2003; Trapani and Sutton, 2003). When sporozoite-induced CD4+ T cells were activated, either by stimulation with peptide-pulsed EBV-B target cells or by cross-linking by antibody to CD3, both cytotoxic and non-cytotoxic CD4+ T cell clones secreted similar amounts of serine esterases into the supernatant that were detectable by BLT assay (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

CD4+ cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) express perforin and serine esterases. Immunocytochemical staining of sporozoite-induced clones (A–D) and peptide-induced clones (E–F). N-benzyloxycarbonyl-L-lysine thiobenzyl ester (BLT) staining for serine esterase in sporozoite-induced CD4+ T cell clones (A) cytotoxic DR7-M2B10 or (B) non-cytotoxic DR7-1D2. The punctate cytoplasmic reaction pattern is consistent with location in cytotoxic granules. Staining with a perforin-specific monoclonal antibody (MAb) of (C) cytotoxic clone DR7-M2B10 or (D) non-cytotoxic (clone DR7-1D2). Flow cytometry analysis of peptide-induced CD4+ T cells stained with a MAb specific for human perforin following stimulation with anti-CD3 of (E) the cytotoxic clone DR4-65 and (F) the non-cytotoxic clone DR4-131.

In contrast, perforin was found only in activated cytotoxic CD4+ T cell clones. Immunolabeling with a MAb against human perforin (Kawasaki et al., 1990) yielded a punctate cytoplasmic distribution, consistent with granule localization, in the sporozoite-induced cytotoxic CD4+ CTL clone DR7-2B10, but little or no staining in the non-lytic clone DR7-1D2 (Fig. 4C and D). Perforin expression was also detected by flow cytometry analysis in peptide induced cytotoxic CD4+ CTLs (DR4-65), with minimal expression in non-lytic clone (DR4-131) (Fig. 4E and F). These data indicate that malaria-specific CD4+ T cells contain granules that store granzymes, but perforin can be detected only in the highly cytotoxic clones, consistent with findings in CD4+ CTLs specific for viruses and other pathogens (Miskovsky et al., 1994; Appay et al., 2002; Casazza et al., 2006).

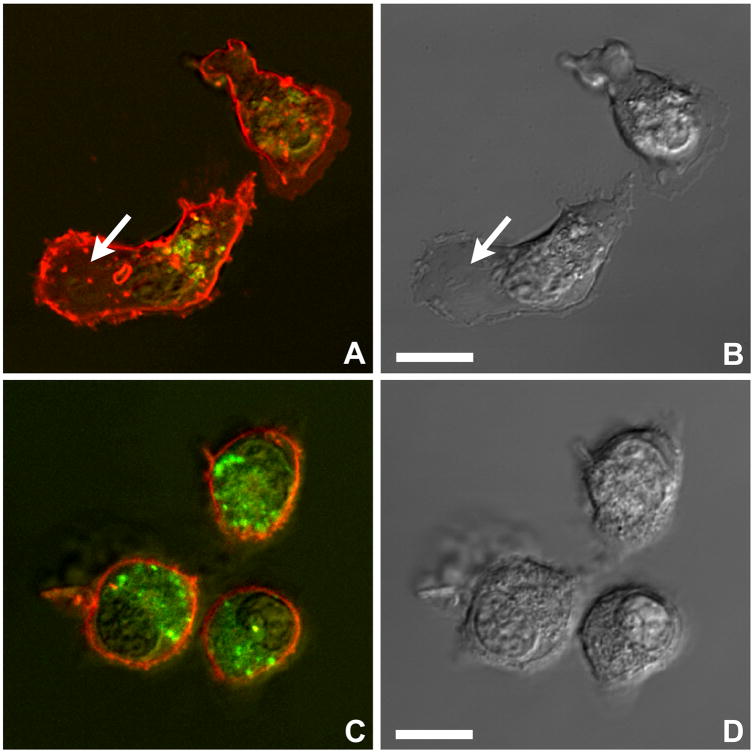

3.5. Motility and morphology of CD4+ T cells

To examine live CD4+ CTLs, the cytotoxic granules, which are part of the lysosomal system, were loaded with LysoTracker Green. The cell membrane was labeled with a red lipophilic dye (FM 4-64) that integrates into phospholipid membranes. Live cell imaging showed that, similar to CD8+ CTLs (Yannelli et al., 1986), the malaria-specific CD4+ CTLs had a polar morphology. The cells were shown to crawl with a broad organelle-free leading edge and a tapered trailing uropod containing a cluster of cytotoxic granules (Fig. 5A and B). When CD4+ CTLs attached to the bottom of the dish, the granules accumulated near the cover glass (Fig. 5C and D).

Fig. 5.

Motility of CD4+ cytotoxic T cells (CTLs). A and B) Parallel fluorescence and differential interference contrast images show groups of CD4+ T cells (clone DR4-65) that are crawling and have adopted an elongated shape. The cytotoxic granules were loaded with LysoTracker Green and the lipophilic red dye FM 4-64 FX was incorporated into the cell membrane. Note the organelle-free leading edge (arrows) and the trailing uropod containing the cytotoxic granules. C, D) Other CTLs (clone DR4-65) appear rounded due to adhesion of the uropod to the glass surface. The cytotoxic granules of these cells have accumulated near the zone of contact with the glass, while their leading edges extend into the culture medium. Live cell imaging, confocal microscopy. Bars = 5 μm.

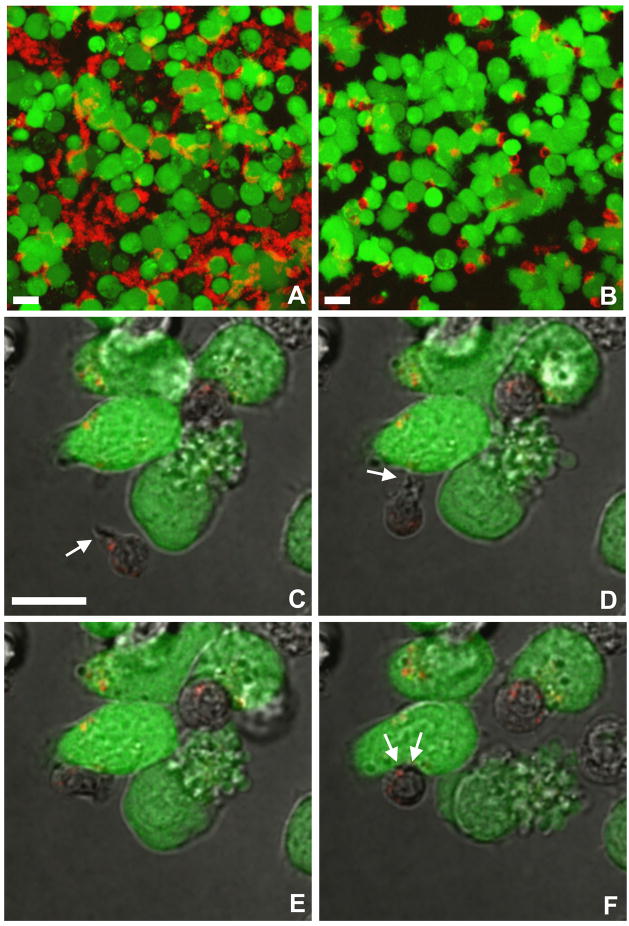

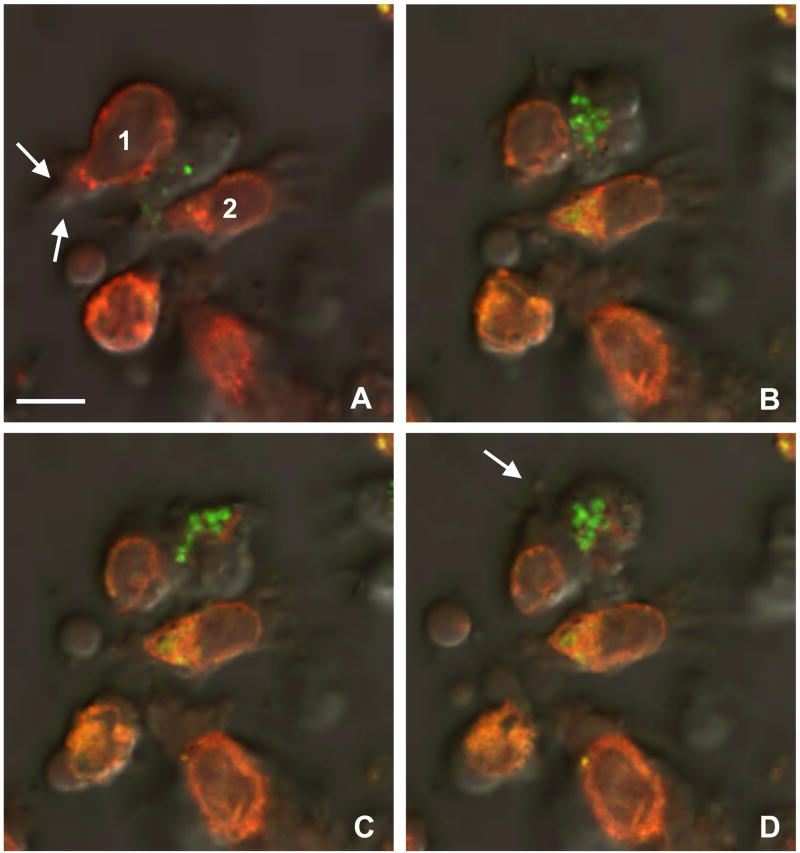

3.6. CD4+ CTL / target cell recognition is peptide dependent

To study the dynamics of the interaction between CD4+ CTLs and target cells, EBV-B cells were primed overnight with T* peptide, K--KR variant peptide, or no peptide. The cytosol was then loaded with CellTrace Calcein for live cell imaging by confocal microscopy. The green fluorescent EBV-B cells were then co-cultivated with CD4+ CTLs (DR4-W2F9 or DR4-65), whose cytotoxic granules had been labeled with the red marker TFL4-Cy5.

Time series show that in the absence of cognate (variant K--KR) peptide, the cytolytic CD4+ CTL clone DR4-65 did not engage in any prolonged contact with target cells. Instead, the CTLs continued to crawl, maintaining the typical elongated polarized cell shape with the cytotoxic granules clustered at the trailing uropod (Supplementary Movie S1). A maximum projection of this time series visualizes the path of the crawling T cells (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Motility of CD4+ cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) in presence or absence of cognate peptide-pulsed target cells. A) Target cells were incubated with variant K--KR peptide and exposed to the lytic CD4+ CTL clone DR4-65. In the absence of cognate peptide, the TFL4-Cy5 loaded CTLs remain elongated and continue to crawl between the CellTrace Calcein Green-loaded target cells. The maximum projection of a time series (see Supplementary Movie S1) visualizes the tracks of the motile T cells. B) In contrast, the lytic CD4+ CTL clone DR4-W2F9 recognizes EBV-B cells pulsed with the high affinity K--KR variant peptide. The maximum projection of a time series (see Supplementary Movie S2) documents that virtually all the CTLs arrest and round up immediately upon contact with a CellTrace Calcein Green labeled target cell pulsed with cognate peptide. C–F) Individual frames from a time series (see Supplementary Movie S3) demonstrating that CD4+ CTLs use lamellipodia for target cell recognition. C) A TFL4-Cy5 loaded CTL crawls with its lamellipodia pointing in the direction of movement. Immediately upon contact with a CellTrace Calcein Green-labeled target cell, the CTL rounds up and reorients its cytotoxic granules towards the area of contact (D). Bars = 10 μm.

In contrast, when incubated with target cells pulsed with the same K--KR variant peptide, DR4-W2F9 CD4+ CTLs immediately arrested and rounded up (Supplementary Movie S2). A maximum projection confirms that DR4-W2F9 CTLs remained stationary for the entire observation period of 10 min (Fig. 6B). Target cell priming with T* peptide caused both CD4+ CTL clones to arrest immediately, while neither clone recognized EBV-B cells in the absence of peptide (data not shown).

CD8+ CTLs are known to contain a multi-molecular complex of adhesion molecules in the trailing uropod, while the tentacle-like lamellipodia, which extend from the leading edge and are thought to act as a propulsive force, carry the TCR and various chemokine receptors (Ng et al., 2008). Consistent with this asymmetric receptor distribution, CD4+ CTLs first contacted target cells with their lamellipodia and then reoriented their uropod with the granules towards the zone of contact (Fig. 6C–I and Supplementary Movie S4).

3.7. Dynamics of the CD4+ T cell / target cell interaction

To examine more closely the dynamics of the cell interactions, in another set of experiments, EBV-B cells were pulsed overnight with T* peptide, K--KR variant peptide or no peptide and the target cell cytosol was loaded with CellTracker Red (Fig. 7 and Supplementary Movie S3). The red fluorescent target cells were then incubated with CD4+ CTLs clone DR4-W2F9 whose granules were loaded with LysoTracker Green. Time series document that immediately upon recognition of a target cell primed with K--KR variant peptide, clone DR4-W2F9 CD4+ CTLs rounded up (Fig. 7A) and reoriented their cytotoxic granules towards the area of adhesion (Fig. 7B). The granules remained associated with each other while moving in and out of the optical plane (Fig. 7C) suggesting that they followed the movements of the microtubule organizing center (MTOC) as described for CD8+ CTLs (Bossi and Griffiths, 2005; Menager et al., 2007). Conjugation with CD4+ CTLs gradually induced membrane blebbing, formation of apoptotic bodies and cytoplasmic swelling in target cells (Fig. 7C and D). As above, CD4+ CTLs did not engage in any prolonged contact with target cells in the absence of peptide (data not shown).

Fig. 7.

CD4+ cytotoxic T cell (CTL) attack causes target cell rounding and blebbing. A–D) Individual frames from a time series (see Supplementary Movie S4) show a LysoTracker Green-loaded CTL (clone DR4-W2F9) approaching one of the CellTracker Red-labeled peptide-pulsed target cells (1), rounding up, and reorienting its granules towards the contact zone. B) The target cell retracts its membrane protrusions (B) and begins to swell (C). D) Eventually, the membrane of the attacked EBV-B target cell shows blebs (arrow), while neighboring cells (2) remain unaltered and well spread. The cytotoxic granules of the effector cell remain associated with each other while moving in and out of the optical plane. Bars = 10 μm.

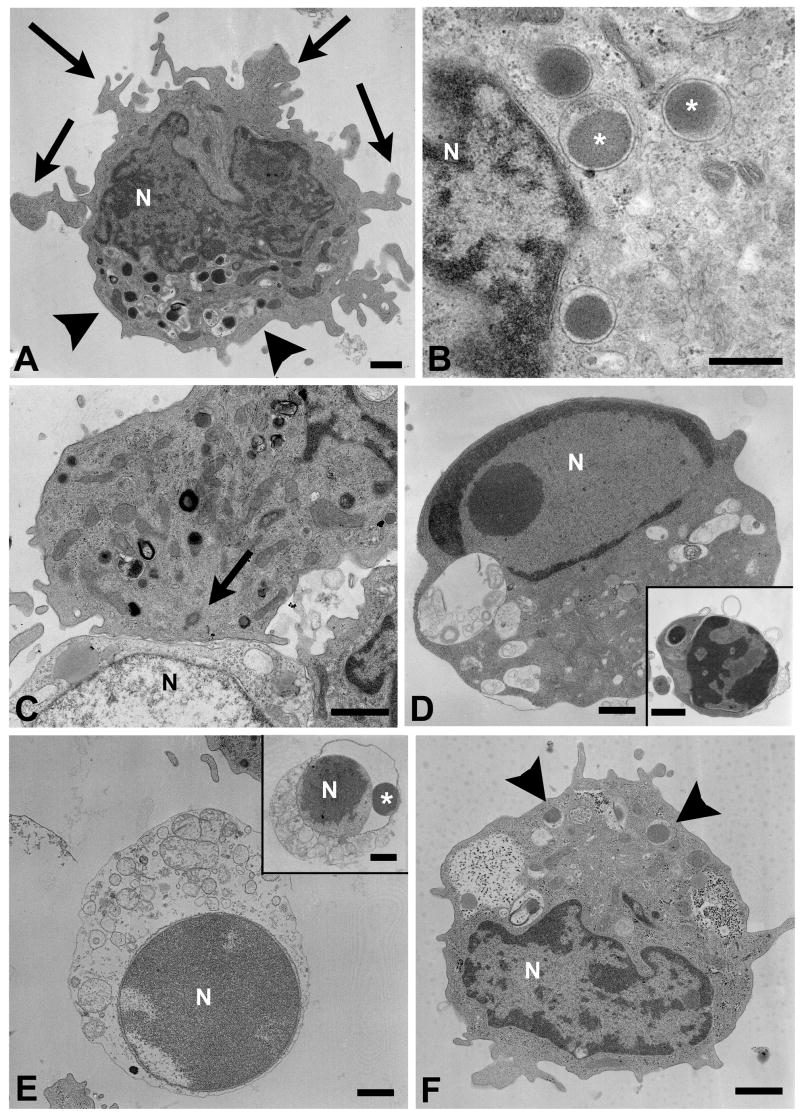

3.8. CD4+ CTL / target cell conjugates interact via typical immunological synapses

To confirm target cell apoptosis on the ultrastructural level, cytotoxic or non-lytic CD4+ T cell clones derived from sporozoite- or peptide-immunized volunteers were incubated for 30 min, 3 h or 6 h with EBV-B target cells in the presence or absence of T* peptide and processed for electron microscopic examination. Lytic CD4+ T cells (clone DR7-M2B10) contained characteristic cytotoxic granules in their cytoplasm (Fig. 8A). The granules measured 400–500 nM in diameter (Fig. 8B), exhibited the dense homogeneous core typically found in cytotoxic granules from CD8+ T cells or natural killer (NK) cells (Clark and Griffiths, 2003) and were frequently concentrated at one pole of the cell. Conjugates of CD4+ CTLs and peptide-pulsed target cells were connected via typical immunological synapses (Fig. 8C) with the cytotoxic granules and the MTOC orientated towards the zone of contact. Some target cells showed hallmarks of apoptosis such as nuclear condensation and fragmentation (Fig. 8D), blebbing of the cell membrane and formation of apoptotic bodies (Fig. 8D, insert). Other target cells exhibited signs of cytoplasmic swelling or disintegration and appeared to undergo necrosis (Fig. 8E). However, these swollen cells also showed evidence for prior chromatin condensation and nuclear fragmentation (Fig. 8E, insert) suggesting that necrosis had occurred secondary to apoptosis. The percentage of dying or dead target cells increased with time. Neither reorientation of the cytotoxic granules towards the target cell nor target cell death was observed in the absence of cognate peptide. Similarly, incubation of peptide-pulsed target cells with the non-lytic CD4+ T cell clone DR7-1D2 did not induce apoptotic changes in the target cells (data not shown). Non-lytic CD4+ T cells contained a lower number of granules, which also had a different morphological appearance (Fig. 8F). Taken together, these data suggest that CD4+ CTLs form a typical immunological synapse with their targets and kill those by granule discharge in a peptide-dependent manner.

Fig. 8.

CD4+ CTLs kill target cells by apoptosis. A) CD4+ cytotoxic T cell (CTL) clone DR7-M2B10 contains a cluster of cytotoxic granules (arrowheads) and cytoplasmic protrusions (arrows). B) Typical cytotoxic granules (*) in the cytoplasm of CD4+ CTLs. C) Typical immunological synapse between a CD4+ CTL (top) and a peptide-pulsed target cell (bottom). The microtubule organizing center (arrow) is located in close apposition to the contact zone. D) Dead target cell exhibiting nuclear condensation, membrane blebbing, vacuolization and apoptotic bodies (insert). E) The homogeneous chromatin structure indicates that this target cell has died by apoptosis prior to secondary necrosis. Insert: a necrotic target cell exhibits swollen cytoplasmic organelles. The nuclear fragment (*), located between the distended membranes of the nuclear envelope, indicates target cell apoptosis. F) Typical appearance of a non-cytolytic CD4+ T cell (clone DR7-1D2). The cell contains only a small number of lysosomes (arrowheads), whose matrix also has a lower density than the cytotoxic granules of CD4+ CTLs. Cells were fixed after 30 min (A–D, F), 3 h (E), and 6 h (E insert) of co-cultivation. N = nucleus. Bars = 1 μm.

3.9. CD4+ CTL attack does not impair the target cell membrane integrity

Cells that succumb to apoptosis in vivo normally retain the physiologic barrier function of the plasma membrane until they are eliminated by phagocytosis (Leist and Jaattela, 2001). However, since the peptide-pulsed target cells released 51Cr and exhibited DNA degradation after 4 h in vitro exposure to CD4+ CTL clones, and since others reported that human CD8+ CTL lines cause target cells to loose fluorescent cytoplasmic tracer within a few minutes (Zweifach, 2000; Lyubchenko et al., 2001; Faroudi et al., 2003; Wiedemann et al., 2006), we loaded EBV-B cells with Calcein Green and monitored the fluorescence emission over time. Analysis of dozens of CD4+ CTL target cell conjugates yielded no evidence for any significant loss of tracer within at least 30 min of observation (data not shown). Thus, CD4+ CTLs caused blebbing of the target cell membrane and formation of apoptotic bodies, but no sudden change in membrane permeability. This finding suggests that CD4+ CTLs secrete perforin or other membrane-perturbing molecules predominantly into the immunological synapse and these trigger target cell death by apoptosis, which may be followed by loss of membrane integrity and secondary necrosis.

4. Discussion

These studies demonstrate that Plasmodium-specific cytotoxic CD4+ T cells can be elicited in volunteers by immunization with irradiated sporozoites as well as by immunization with a synthetic peptide vaccine containing a universal T cell epitope of P. falciparum CSP. The high-avidity CD4+ CTLs induce apoptosis in autologous target cells primed with cognate peptide. These human CD4+ CTLs are multifunctional as, in addition to cytolytic activity, they secrete a broad range of cytokines when stimulated with the T* peptide (Moreno et al., 1993b; Calvo-Calle et al., 2005).

Although considerably less detail is available on the cytotoxic machinery of CD4+ CTLs compared to CD8+ CTLs, in studies of murine virus-specific T cells both appear to possess the same general repertoire of pro-apoptotic mechanisms (Ng et al., 2008). On the transcript level, CD4+ and CD8+ CTLs share a very similar profile of effector molecules such as perforin, granzyme B and IFN-γ (Hidalgo et al., 2008). Both CD4+ and CD8+ CTLs are able to employ either the perforin/granzyme or the Fas/FasL pathway for target cell killing, in humans as well as in mice (Vergelli et al., 1997; Russell and Ley, 2002; Grossman et al., 2004). Further, CD4+ and CD8+ CTLs specific for viral antigens form immunological synapses upon APC recognition and undergo the same general reorganization of MTOC and cytotoxic granules towards the target cell.

Consistent with the studies in tumor and virus-specific CD4+ CTLs, upon activation, the Plasmodium-specific CD4+ CTLs were found to express perforin and release BLT esterases. Electron and confocal microscopy demonstrated that these CD4+ CTLs recognized target cells with their lamellipodia, suggesting an asymmetric receptor distribution, as found with CD8+ CTLs. Following arrest of the cells in the presence of specific peptide, the Plasmodium-specific CD4+ CTLs form a typical immunological synapse with target cells and vectorially relocate their cytotoxic granules and MTOC towards the zone of contact. The CD4+ CTLs and target cells remain conjugated for at least 30 min. Subsequently, the peptide-pulsed EBV-B target cells exhibit DNA degradation, chromatin condensation, nuclear fragmentation, blebbing of the cell membrane with formation of apoptotic bodies - all hallmarks of apoptosis - and eventually secondary necrosis.

Live cell imaging revealed that CD4+ CTL attack does not cause any significant loss of fluorescent tracer from the target cell cytoplasm within at least 30 min. The observed DNA fragmentation, chromatin condensation, target cell rounding and blebbing is consistent with death by apoptosis, a highly regulated process that may take hours to complete (Krysko et al., 2008). Kinetics of DNA fragmentation as measured by the JAM assay indicate no DNA degradation at 2 h, half maximal loss of labeled DNA at 4 h and maximal loss by 8 h post incubation of effector and target cells (Alberto Moreno, unpublished data).

Consistent with CD8+ T cell studies (Yang et al., 2002; Villacres et al., 2003; Almeida et al., 2007), we also show that the avidity of cognate peptide/TCR interactions controls the lytic activity of the individual CD4+ T cell clones, implying that the avidity of the HLA/peptide/TCR complex determines the extent of CTL activation. In agreement with this interpretation, others found that the level of activation determines whether CD8+ CTLs form lytic synapses, which mediate target cell killing by polarized granule secretion, or stimulatory (non-lytic) synapses, which stimulate protracted signal transduction for long-term production of cytokines (Faroudi et al., 2003). The finding that CD4+ CTLs can remain conjugated for hours (Trambas and Griffiths, 2003) is consistent with the positive correlation of IL-2 production observed in the lytic CD4+ T cell clones.

The proposed effector mechanism for the human CSP-specific CD4+ CTLs, i.e. granule-mediated exocytosis of perforin and granzymes, is consistent with the reported CD8+ CTL-mediated killing of Plasmodium berghei-infected murine hepatocytes in vitro (Bongfen et al., 2007). Together, these results suggest the potential of CD4+ CTLs to play a direct role in the clearance of P. falciparum EEFs from the liver. Indeed, data from mouse models support an effector role for CD4+ T cells in vivo. CD4+ T cells confer protective immunity in CD8+ T cell-deficient mice immunized with P. berghei or Plasmodium yoelii irradiated sporozoites (Oliveira et al., 2008) and depletion of CD8+ T cells does not abrogate sporozoite-induced immunity in all strains of mice (Doolan and Hoffman, 2000). In addition, transfer of murine CD4+ CTLs, as well as CD8+ CTLs, induced by either peptide or sporozoite vaccination, can passively protect naïve mice against sporozoite challenge and block liver stage development in vitro (Romero et al., 1989; Tsuji et al., 1990; Rénia et al., 1991, 1993; Rodrigues et al., 1991).

Immunization and passive transfer studies in the murine model demonstrate that CD4+ T cells are directly functional in vivo. Class II restricted CD4+ CTLs were initially thought to be of limited effectiveness in the liver because parenchymal cells normally do not express class II antigens. However, numerous studies have shown that infectious agents such as viruses, as well as cytokines such as IFN-γ, can induce class II antigen expression on hepatocytes in vivo (Franco et al., 1988; Lobo-Yeo et al., 1990; Vergani et al., 2002; Herkel et al., 2003). Recent functional and morphological studies demonstrate that naïve CD8+ T cells monitor hepatocytes by sending cytoplasmic extensions across the endothelial fenestration into the space of Disse (McAvoy and Kubes, 2006; Warren et al., 2006). The similar morphology, polarity and motility of CD4+ CTL documented in the present studies suggest that Plasmodium-specific CD4+ CTLs could recognize infected hepatocytes directly, extravasate into the space of Disse, and kill those via classical granule-mediated cytotoxicity, as proposed for CD8+ CTLs. Future comparison of the activity of these CD4+ CTLs and human CD8+ CTLs (Prato et al., 2005) in humanized mice (Morosan et al., 2006; Shultz et al., 2007) should shed light on the human immune mechanisms that function in the control of the pre-erythrocytic stages of Plasmodium.

Alternatively, CD4+ T cells may encounter CSP-derived peptide on other class II positive liver cells. The current studies and previous work demonstrate that immunization with P. falciparum sporozoites or CSP peptide induce multifunctional human CD4+ T cells that are capable of both granule-mediated cytotoxicity as well as secretion of high levels of IFN-γ (Calvo-Calle et al., 2005; Oliveira et al., 2008), a cytokine known to inhibit EEF development (Ferreira et al., 1987; Schofield et al., 1987; Mellouk et al., 1991; Seguin et al., 1994). Such bifunctional CD4+ T cells may recognize CSP presented by class II on non-parenchymal cells and inhibit EEF development via IFN-γ-mediated induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in infected hepatocytes (Hollingdale and Krzych, 2002). Kupffer cells, in particular, represent excellent candidates for presentation of Plasmodium antigens as these professional antigen-presenting cells are exposed to sporozoites exiting the circulation and are thus strategically positioned for interaction with CTLs patrolling the liver (Meis et al., 1983; Pradel and Frevert, 2001; Ishino et al., 2004; Frevert et al., 2005; Baer et al., 2007b; Usynin et al., 2007). However, based on early reports suggesting that lethal irradiation to eliminate Kupffer cells from the liver (Haller et al., 1979; Paradis et al., 1990), a recent study has raised a question as to the role of Kupffer cells as APCs for Plasmodium-specific T cells. Protective immunity following adoptive transfer of murine CSP specific transgenic CD8+ CTL into the lethally irradiated recipients suggested that non-parenchymal cells did not play a role as APC in adaptive immunity to malaria (Sano et al., 2001; Chakravarty et al., 2007). This conclusion must be reconsidered, however, in light of the latest demonstration that sessile Kupffer cells are actually highly resistant to irradiation (Klein et al., 2007). With the recent advances in intravital imaging, the tools and technology are on hand to unravel the cellular interactions and molecular processes involved in the elimination of Plasmodium EEFs from the liver in vivo.

How CD4+ T cells are initially programmed for cytotoxic potential is unknown, but the induction of multifunctional CD4+ T cells, capable of both cytotoxic and cytokine responses, may enable these effector cells to kill EEFs both directly by granule-mediated cytotoxicity, and indirectly by IFN-γ mediated iNOS induction in infected hepatocytes. A combination of these effector mechanisms would greatly enhance elimination of EEFs from the liver of malaria-infected individuals. The finding that a peptide vaccine can elicit multifunctional CD4+ T cells with cytotoxic potential in humans, similar to CD4+ CTLs elicited by sporozoite immunization, encourages efforts to develop effective pre-erythrocytic subunit vaccines to control a parasite infection that afflicts over 300–500 million people in the world today.

Supplementary Material

CD4+ cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) fail to recognize target cells in the absence of cognate peptide. CD4+ T cells (clone DR4-65) with TLF4-Cy5 loaded granules were added to Calcein Green-labeled target cells primed with variant K--KR peptide. The absence of cognate peptide prevents target cell recognition and causes the CD4+ CTLs to continue to migrate. Confocal live cell microscopy, cycle time 10 s, replay speed 10 frames/s, total time: 10 min.

CD4+ T cells remain in contact with target cells in the presence of peptide. CD4+ T cells (clone DR4-W2F9) were loaded with TLF4-Cy5 and added to Calcein Green-labeled target cells pulsed with K--KR variant peptide. The CD4+ T cells recognize this high-affinity peptide, immediately adhere, adopt a rounded shape, and reorient their granules towards the target cells. Confocal live cell microscopy, cycle time 10 s, replay 10 frames/s, total time: 10 min.

CD4+ cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) use lamellipodia for target cell recognition. A CD4+ CTL (clone DR4-W2F9; containing red cytotoxic granules) approaches a variant K--KR peptide-primed target cell (green). Note the polarized shape of the CTL with the leading edge pointing in the direction of movement. As soon as the lamellipodia make contact with the target cell, the CTL rounds up and reorients its cytotoxic granules (red) towards the zone of adhesion. The CTL remains immotile until the end of the observation period (10 min). Note that CD4+ CTLs typically push a dent into the target cell membrane (arrow). Confocal live cell microscopy, cycle time 3 s 259 ms, replay speed 10 frames/s, total time: 5 min 20 s.

Dynamics of the cytotoxic CD4+ cytotoxic T cell (CTL)-mediated target cell attack. A CD4+ T cell (clone DR4-65), whose cytotoxic granules were loaded with LysoTracker Green, approaches one of the T* peptide-pulsed target cells, whose cytoplasm was loaded with CellTracker Red. Upon contact, the CTL reorients its granules towards the zone of contact. The target cell gradually looses its membrane protrusions and eventually shows extensive membrane blebbing. Despite considerable movement within the cytoplasm of the CTL, the cytotoxic granules remain in close association with each other. Confocal live cell microscopy, cycle time 6 s 519 ms, replay speed 10 frames/s, total time: 22 min.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the expert technical assistance provided by Rita Altszuler. The work was supported by NIH grants RO1 AI 25085 and RO1 AI45138 to EN and RO1 AI51656 and S10 RR019288 to UF. CK received a postdoctoral fellowship from the American Liver Foundation.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data associated with this article.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Almeida JR, Price DA, Papagno L, Arkoub ZA, Sauce D, Bornstein E, Asher TE, Samri A, Schnuriger A, Theodorou I, Costagliola D, Rouzioux C, Agut H, Marcelin AG, Douek D, Autran B, Appay V. Superior control of HIV-1 replication by CD8+ T cells is reflected by their avidity, polyfunctionality, and clonal turnover. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2473–2485. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amino R, Menard R, Frischknecht F. In vivo imaging of malaria parasites - recent advances and future directions. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005;8:407–414. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appay V, Zaunders JJ, Papagno L, Sutton J, Jaramillo A, Waters A, Easterbrook P, Grey P, Smith D, McMichael AJ, Cooper DA, Rowland-Jones SL, Kelleher AD. Characterization of CD4(+) CTLs ex vivo. J Immunol. 2002;168:5954–5958. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslan N, Yurdaydin C, Wiegand J, Greten T, Ciner A, Meyer MF, Heiken H, Kuhlmann B, Kaiser T, Bozkaya H, Tillmann HL, Bozdayi AM, Manns MP, Wedemeyer H. Cytotoxic CD4 T cells in viral hepatitis. J Viral Hepat. 2006;13:505–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer K, Klotz C, Kappe SHIK, Schnieder T, Frevert U. Release of hepatic Plasmodium yoelii merozoites into the pulmonary microvasculature. PLoS Pathog. 2007a;3:e171. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer K, Roosevelt M, Van Rooijen N, Clarkson AB, Jr, Schnieder T, Frevert U. Kupffer cells are obligatory for Plasmodium sporozoite infection of the liver. Cell Microbiol. 2007b;9:397–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastian M, Braun T, Bruns H, Rollinghoff M, Stenger S. Mycobacterial lipopeptides elicit CD4+ CTLs in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected humans. J Immunol. 2008;180:3436–3446. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berke G. The CTL’s kiss of death. Cell. 1995;81:9–12. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90365-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongfen SE, Torgler R, Romero JF, Renia L, Corradin G. Plasmodium berghei-infected primary hepatocytes process and present the circumsporozoite protein to specific CD8+ T cells in vitro. J Immunol. 2007;178:7054–7063. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.7054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossi G, Griffiths GM. CTL secretory lysosomes: biogenesis and secretion of a harmful organelle. Semin Immunol. 2005;17:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo-Calle JM, Hammer J, Sinigaglia F, Clavijo P, Moya-Castro ZR, Nardin EH. Binding of malaria T cell epitopes to DR and DQ molecules in vitro correlates with immunogenicity in vivo: identification of a universal T cell epitope in the Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein. J Immunol. 1997;159:1362–1373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo-Calle JM, Oliveira GA, Nardin E. Human CD4+ T cells induced by synthetic peptide malaria vaccine are comparable to cells elicited by attenuated P. falciparum sporozoites. J Immunol. 2005;175:7575–7585. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho LH, Sano G, Hafalla JC, Morrot A, Curotto de Lafaille MA, Zavala F. IL-4-secreting CD4+ T cells are crucial to the development of CD8+ T-cell responses against malaria liver stages. Nat Med. 2002;8:166–170. doi: 10.1038/nm0202-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casazza JP, Betts MR, Price DA, Precopio ML, Ruff LE, Brenchley JM, Hill BJ, Roederer M, Douek DC, Koup RA. Acquisition of direct antiviral effector functions by CMV-specific CD4+ T lymphocytes with cellular maturation. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2865–2877. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalfamo M, Henkart PA. Perforin and the granule exocytosis cytotoxicity pathway. Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15:522–527. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(03)00114-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarty S, Cockburn IA, Kuk S, Overstreet MG, Sacci JB, Zavala F. CD8(+) T lymphocytes protective against malaria liver stages are primed in skin-draining lymph nodes. Nat Med. 2007;13:1035–1041. doi: 10.1038/nm1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charoenvit Y, Majam VF, Corradin G, Sacci JB, Jr, Wang R, Doolan DL, Jones TR, Abot E, Patarroyo ME, Guzman F, Hoffman SL. CD4(+) T-cell- and gamma interferon-dependent protection against murine malaria by immunization with linear synthetic peptides from a Plasmodium yoelii 17-kilodalton hepatocyte erythrocyte protein. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5604–5614. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.5604-5614.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Griffiths GM. Lytic granules, secretory lysosomes and disease. Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15:516–521. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(03)00113-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depoil D, Zaru R, Guiraud M, Chauveau A, Harriague J, Bismuth G, Utzny C, Muller S, Valitutti S. Immunological synapses are versatile structures enabling selective T cell polarization. Immunity. 2005;22:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolan DL, Hoffman SL. The complexity of protective immunity against liver-stage malaria. J Immunol. 2000;165:1453–1492. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolan DL, Martinez-Alier N. Immune response to pre-erythrocytic stages of malaria parasites. Curr Mol Med. 2006;6:169–185. doi: 10.2174/156652406776055249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dustin ML. A dynamic view of the immunological synapse. Semin Immunol. 2005;17:400–410. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dustin ML. Impact of the immunological synapse on T cell signaling. Results Probl Cell Differ. 2006;43:175–198. doi: 10.1007/400_019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faroudi M, Utzny C, Salio M, Cerundolo V, Guiraud M, Muller S, Valitutti S. Lytic versus stimulatory synapse in cytotoxic T lymphocyte/target cell interaction: manifestation of a dual activation threshold. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14145–14150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2334336100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira A, Morimoto T, Altszuler R, Nussenzweig V. Use of a DNA probe to measure the neutralization of Plasmodium berghei sporozoites by a monoclonal antibody. J Immunol. 1987;138:1256–1259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco A, Barnaba V, Natali P, Balsano C, Musca A, Balsano F. Expression of class I and class II major histocompatibility complex antigens on human hepatocytes. Hepatology. 1988;8:449–454. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840080302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frevert U, Reinwald E. Formation of filopodia in Trypanosoma congolense by cross-linking the variant surface antigen. J Ultrastruct Molec Struct Res. 1988;99:124–136. doi: 10.1016/0889-1605(88)90048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frevert U, Engelmann S, Zougbédé S, Stange J, Ng B, Matuschewski K, Liebes L, Yee H. Intravital observation of Plasmodium berghei sporozoite infection of the liver. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e192. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis S, Ferm MM, Ou W, Smith KA. T cell growth factor: parameters of production and a quantitative microassay for activity. J Immunol. 1978;120:2027–2032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman WJ, Verbsky JW, Tollefsen BL, Kemper C, Atkinson JP, Ley TJ. Differential expression of granzymes A and B in human cytotoxic lymphocyte subsets and T regulatory cells. Blood. 2004;104:2840–2848. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haller O, Arnheiter H, Lindenmann J. Natural, genetically determined resistance toward influenza virus in hemopoietic mouse chimeras. Role of mononuclear phagocytes. J Exp Med. 1979;150:117–126. doi: 10.1084/jem.150.1.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood SM, Yaqoob MM, Allen DA. Caspase and calpain function in cell death: bridging the gap between apoptosis and necrosis. Ann Clin Biochem. 2005;42:415–431. doi: 10.1258/000456305774538238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herkel J, Jagemann B, Wiegard C, Lazaro JF, Lueth S, Kanzler S, Blessing M, Schmitt E, Lohse AW. MHC class II-expressing hepatocytes function as antigen-presenting cells and activate specific CD4 T lymphocytes. Hepatology. 2003;37:1079–1085. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo LG, Einecke G, Allanach K, Halloran PF. The transcriptome of human cytotoxic T cells: similarities and disparities among allostimulated CD4(+) CTL, CD8(+) CTL and NK cells. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:627–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.02128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingdale M, Krzych U. Immune responses to liver-stage parasites: Implications for vaccine development. In: Perlman P, Troye-Blomberg M, editors. Malaria Immunology. Karger: Basel; 2002. pp. 97–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoves S, Krause SW, Scholmerich J, Fleck M. The JAM-assay: optimized conditions to determine death-receptor-mediated apoptosis. Methods. 2003;31:127–134. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishino T, Yano K, Chinzei Y, Yuda M. Cell-passage activity is required for the malarial parasite to cross the liver sinusoidal cell layer. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E4. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju ST, Ruddle NH, Strack P, Dorf ME, DeKruyff RH. Expression of two distinct cytolytic mechanisms among murine CD4 subsets. J Immunol. 1990;144:23–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki A, Shinkai Y, Kuwana Y, Furuya A, Iigo Y, Hanai N, Itoh S, Yagita H, Okumura K. Perforin, a pore-forming protein detectable by monoclonal antibodies, is a functional marker for killer cells. Int Immunol. 1990;2:677–684. doi: 10.1093/intimm/2.7.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe D, Shi L, Feske S, Massol R, Navarro F, Kirchhausen T, Lieberman J. Perforin triggers a plasma membrane-repair response that facilitates CTL induction of apoptosis. Immunity. 2005;23:249–262. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein I, Cornejo JC, Polakos NK, John B, Wuensch SA, Topham DJ, Pierce RH, Crispe IN. Kupffer cell heterogeneity: functional properties of bone marrow derived and sessile hepatic macrophages. Blood. 2007;110:4077–4085. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-073841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krysko DV, Vanden Berghe T, D’Herde K, Vandenabeele P. Apoptosis and necrosis: Detection, discrimination and phagocytosis. Methods. 2008;44:205–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn JR, Poenie M. Dynamic polarization of the microtubule cytoskeleton during CTL-mediated killing. Immunity. 2002;16:111–121. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00262-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar KA, Sano G, Boscardin S, Nussenzweig RS, Nussenzweig MC, Zavala F, Nussenzweig V. The circumsporozoite protein is an immunodominant protective antigen in irradiated sporozoites. Nature. 2006;444:937–940. doi: 10.1038/nature05361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupfer A, Singer SJ. Cell biology of cytotoxic and helper T cell functions: immunofluorescence microscopic studies of single cells and cell couples. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:309–337. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.001521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leen AM, Christin A, Khalil M, Weiss H, Gee AP, Brenner MK, Heslop HE, Rooney CM, Bollard CM. Identification of hexon-specific CD4 and CD8 T-cell epitopes for vaccine and immunotherapy. J Virol. 2008;82:546–554. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01689-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leist M, Jaattela M. Four deaths and a funeral: from caspases to alternative mechanisms. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:589–598. doi: 10.1038/35085008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman J. The ABCs of granule-mediated cytotoxicity: new weapons in the arsenal. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:361–370. doi: 10.1038/nri1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo-Yeo A, Senaldi G, Portmann B, Mowat AP, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D. Class I and class II major histocompatibility complex antigen expression on hepatocytes: a study in children with liver disease. Hepatology. 1990;12:224–232. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840120208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubchenko TA, Wurth GA, Zweifach A. Role of calcium influx in cytotoxic T lymphocyte lytic granule exocytosis during target cell killing. Immunity. 2001;15:847–859. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00233-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzinger P. The JAM test. A simple assay for DNA fragmentation and cell death. J Immunol Methods. 1991;145:185–192. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(91)90325-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAvoy EF, Kubes P. Holey endothelium: gateways for naive T cell activation. Hepatology. 2006;44:1083–1085. doi: 10.1002/hep.21421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meis JF, Verhave JP, Jap PH, Meuwissen JH. An ultrastructural study on the role of Kupffer cells in the process of infection by Plasmodium berghei sporozoites in rats. Parasitology. 1983;86:231–242. doi: 10.1017/s003118200005040x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellouk S, Green SJ, Nacy CA, Hoffman SL. IFN-γ inhibits development of Plasmodium berghei exoerythrocytic stages in hepatocytes by an L-arginine-dependent effector mechanism. J Immunol. 1991;146:3971–3976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menager MM, Menasche G, Romao M, Knapnougel P, Ho CH, Garfa M, Raposo G, Feldmann J, Fischer A, de Saint Basile G. Secretory cytotoxic granule maturation and exocytosis require the effector protein hMunc13-4. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:257–267. doi: 10.1038/ni1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miskovsky EP, Liu AY, Pavlat W, Viveen R, Stanhope PE, Finzi D, Fox WM, 3rd, Hruban RH, Podack ER, Siliciano RF. Studies of the mechanism of cytolysis by HIV-1-specific CD4+ human CTL clones induced by candidate AIDS vaccines. J Immunol. 1994;153:2787–2799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra-Kaushik S, Cruz J, Stern LJ, Ennis FA, Terajima M. Human cytotoxic CD4+ T cells recognize HLA-DR1-restricted epitopes on vaccinia virus proteins A24R and D1R conserved among poxviruses. J Immunol. 2007;179:1303–1312. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molano A, Park SH, Chiu YH, Nosseir S, Bendelac A, Tsuji M. Cutting Edge: The IgG response to the circumsporozoite protein is MHC class II-dependent and CD1d-independent: Exploring the role of GPIs in NK T cell activation and antimalarial responses. J Immunol. 2000;164:5005–5009. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.10.5005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno A, Clavijo P, Edelman R, Davis J, Sztein M, Herrington D, Nardin E. Cytotoxic CD4+ T cells from a sporozoite-immunized volunteer recognize the Plasmodium falciparum CS protein. Int Immunol. 1991;3:997–1003. doi: 10.1093/intimm/3.10.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno A, Clavijo P, Edelman R, Davis J, Sztein M, Sinigaglia F, Nardin E. CD4+ T cell clones obtained from Plasmodium falciparum sporozoite-immunized volunteers recognize polymorphic sequences of the circumsporozoite protein. J Immunol. 1993a;151:489–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno A, Xu SG, Levitt A, Nardin E. Effector mechanisms of human T cell clones specific for the Plasmodium CS Th/Tc epitope. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993b;49:173. [Google Scholar]

- Morosan S, Hez-Deroubaix S, Lunel F, Renia L, Giannini C, Van Rooijen N, Battaglia S, Blanc C, Eling W, Sauerwein R, Hannoun L, Belghiti J, Brechot C, Kremsdorf D, Druilhe P. Liver-stage development of Plasmodium falciparum, in a humanized mouse model. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:996–1004. doi: 10.1086/500840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardin EH, Nussenzweig RS. T cell responses to pre-erythrocytic stages of malaria: role in protection and vaccine development against pre-erythrocytic stages. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:687–727. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.003351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardin EH, Calvo-Calle JM, Oliveira GA, Nussenzweig RS, Schneider M, Tiercy JM, Loutan L, Hochstrasser D, Rose K. A totally synthetic polyoxime malaria vaccine containing Plasmodium falciparum B cell and universal T cell epitopes elicits immune responses in volunteers of diverse HLA types. J Immunol. 2001;166:481–489. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng LG, Mrass P, Kinjyo I, Reiner SL, Weninger W. Two-photon imaging of effector T-cell behavior: lessons from a tumor model. Immunol Rev. 2008;221:147–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira GA, Kumar KA, Calvo-Calle JM, Othoro C, Altszuler D, Nussenzweig V, Nardin EH. Class II restricted protective immunity induced by malaria sporozoites. Infect Immun. 2008;76:1200–1206. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00566-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradis K, Sharp HL, Vallera DA, Blazar BR. Kupffer cell engraftment across the major histocompatibility barrier in mice: bone marrow origin, class II antigen expression, and antigen-presenting capacity. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1990;11:525–533. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199011000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternack MS, Verret CR, Liu MA, Eisen HN. Serine esterase in cytolytic T lymphocytes. Nature. 1986;322:740–743. doi: 10.1038/322740a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters PJ, Borst J, Oorschot V, Fukuda M, Krähenbühl O, Tschopp J, Slot JW, Geuze HJ. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte granules are secretory lysosomes, containing both perforin and granzymes. J Exp Med. 1991;173:1099–1109. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.5.1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pipkin ME, Lieberman J. Delivering the kiss of death: progress on understanding how perforin works. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradel G, Frevert U. Plasmodium sporozoites actively enter and pass through Kupffer cells prior to hepatocyte invasion. Hepatology. 2001;33:1154–1165. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.24237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prato S, Maxwell T, Pinzon-Charry A, Schmidt CW, Corradin G, Lopez JA. MHC class I-restricted exogenous presentation of a synthetic 102-mer malaria vaccine polypeptide. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:681–689. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees W, Bender J, Teague TK, Kedl RM, Crawford F, Marrack P, Kappler J. An inverse relationship between T cell receptor affinity and antigen dose during CD4(+) T cell responses in vivo and in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:9781–9786. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rénia L, Marussig MS, Grillot D, Pied S, Corradin G, Miltgen F, Guidice Gd, Mazier D. In vitro activity of CD4+ and CD 8+ T lymphocytes from mice immunized with a synthetic malaria peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7963–7967. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.18.7963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rénia L, Grillot D, Marussig M, Corradin G, Miltgen F, Lambert PH, Mazier D, Del Guidice G. Effector functions of circumsporozoite peptide-primed CD4+ T cell clones against Plasmodium yoelii liver stages. J Immunol. 1993;150:1471–1478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues MM, Cordey AS, Arreaza G, Corradin G, Romero P, Maryanski JL, Nussenzweig RS, Zavala F. CD8+ cytolytic T cell clones derived against the Plasmodium yoelii circumsporozoite protein protect against malaria. Int Immunol. 1991;3:579–585. doi: 10.1093/intimm/3.6.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero P, Maryanski JL, Corradin C, Nussenzweig RS, Nussenzweig V, Zavala F. Cloned cytotoxic T cells recognize an epitope in the circumsporozoite protein and protect against malaria. Nature. 1989;341:323–326. doi: 10.1038/341323a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JH, Ley TJ. Lymphocyte-mediated cytotoxicity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:323–370. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100201.131730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano G, Hafalla JC, Morrot A, Abe R, Lafaille JJ, Zavala F. Swift development of protective effector functions in naive CD8(+) T cells against malaria liver stages. J Exp Med. 2001;194:173–180. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.2.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield L, Villaquiran J, Ferreira A, Schellekens H, Nussenzweig R, Nussenzweig V. γ interferon, CD8+ T cells and antibodies required for immunity to malaria sporozoites. Nature. 1987;330:664–666. doi: 10.1038/330664a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seguin MC, Klotz FW, Schneider I, Weir JP, Goodbary M, Slayter M, Raney JJ, Aniagolu JU, Green SJ. Induction of nitric oxide synthase protects against malaria in mice exposed to irradiated Plasmodium berghei infected mosquitoes: involvement of interferon gamma and CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1994;180:353–358. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shultz LD, Ishikawa F, Greiner DL. Humanized mice in translational biomedical research. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:118–130. doi: 10.1038/nri2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm A, Amino R, van de Sand C, Regen T, Retzlaff S, Rennenberg A, Krueger A, Pollok JM, Menard R, Heussler VT. Manipulation of host hepatocytes by the malaria parasite for delivery into liver sinusoids. Science. 2006;313:1287–1290. doi: 10.1126/science.1129720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama H, Sitkovsky MV. Antigen receptor-regulated exocytosis in cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1987;166:725–743. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.3.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trambas CM, Griffiths GM. Delivering the kiss of death. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:399–403. doi: 10.1038/ni0503-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapani JA, Sutton VR. Granzyme B: pro-apoptotic, antiviral and antitumor functions. Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15:533–543. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(03)00107-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji M, Romero P, Nussenzweig RS, Zavala F. CD4+ cytolytic T cell clone confers protection against murine malaria. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1353–1357. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.5.1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usynin I, Klotz C, Frevert U. Malaria circumsporozoite protein inhibits the respiratory burst in Kupffer cells. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:2610–2628. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderberg JP, Frevert U. Intravital microscopy demonstrating antibody-mediated immobilization of Plasmodium berghei sporozoites injected into skin by mosquitoes. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:991–996. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergani D, Choudhuri K, Bogdanos DP, Mieli-Vergani G. Pathogenesis of autoimmune hepatitis. Clin Liver Dis. 2002;6:727–737. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(02)00018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergelli M, Hemmer B, Muraro PA, Tranquill L, Biddison WE, Sarin A, McFarland HF, Martin R. Human autoreactive CD4+ T cell clones use perforin- or Fas/Fas ligand-mediated pathways for target cell lysis. J Immunol. 1997;158:2756–2761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]