Abstract

SIV-infected natural hosts do not progress to clinical AIDS yet display high viral replication and an acute immunologic response similar to pathogenic SIV/HIV infections. During chronic SIV infection, natural hosts suppress their immune activation, whereas pathogenic hosts display a highly activated immune state. Here, we review natural host SIV infections with an emphasis on specific immune cells and their contribution to the transition from the acute-to-chronic phases of infection.

Keywords: HIV, SIV, Immune activation, natural hosts

Introduction

Exactly how HIV infection is able to induce the clinical sequelae characteristic of AIDS is a complex question that to date has not been fully answered. While direct infection and killing of CD4+ T cells by HIV likely plays an important role in the progression to disease, it is clearly not the only factor, as progression to AIDS can occur even in patients with healthy CD4+ T levels. A second major immunologic contributor to AIDS progression, identified in the late 1980s- early 1990s, is the prolonged hyper-activation of the immune system that occurs in HIV+ patients. Indeed, a number of studies have indicated that the extent to which the immune system is activated is a better predictor of progression to AIDS than either viral load or CD4+ T cell levels [1-3]. Deciphering the contribution of viral replication, immune activation or any other factor toward the clinical disease progression in humans is further complicated by the fact that humans progress to disease at various rates. One method to enable a more mechanistic approach to this problem is through the use of the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected monkey models. These monkey models include Asian origin rhesus macaques (RM) and pig-tailed macaques (PTM), which undergo a pathogenic disease course similar to HIV infection, as well as African origin sooty mangabeys (SM) and African green monkeys (AGM), which generally do not exhibit any clinical signs of disease when infected with SIV. Indeed a number of laboratories have been employing these monkey models with diverse disease outcomes to provide key insights into the factors contributing to the presence or absence of SIV disease progression [4-11].

Approximately 40 nonhuman primate species in Sub-Saharan Africa are infected with species-specific lentiviruses, collectively referred to as the natural hosts of SIV. These natural SIV infections represent virus-host relationships that are evolutionarily older than the HIV pandemic in humans. Indeed phylogenetic data indicate that HIV-1 and HIV-2 originated from cross-species transmissions of SIVs from chimpanzees (SIVcpz) and SM (SIVsmm), respectively [12]. The majority of natural host studies undertaken to date have focused on two species: SM (Cercocebus atys) and AGM (Chlorocebus spp.). SIV infection of the natural hosts is thought to be predominately sexually transmitted and lifelong, yet there is generally no pathogenic consequence of high levels of SIV replication in these species [10]. We hypothesize that any virologic or immunologic differences that exist between the natural SIV hosts and hosts of pathogenic HIV and SIV infections could be a key factor in the absence of disease progression observed in natural hosts. Some of the differences that have been observed include: infrequent vertical transmission, the maintenance of peripheral CD4+ T cell counts in the majority of animals, normal levels of mucosal T helper type 17 (Th17) cells and, the focus of this review, an absence of sustained immune activation during the chronic phase of the natural host SIV infection (reviewed in detail in [11]). HIV/SIV infections have traditionally been divided into two segments: the intial acute phase and the chronic phase that follows. Acute infection in both pathogenic and natural SIV hosts display striking similarity in the majority of viral and immune parameters [13-19]. Chronic infection, however, is markedly different in pathogenic and nonpathogenic infections. Specifically, during chronic infection the natural hosts of SIV generally maintain healthy levels of peripheral CD4+ T cells, low levels of aberrant immune activation, and no clinical signs of AIDS. The apparent departure between pathogenic and nonpathogenic disease outcomes evident during chronic infection despite generally similar acute phases has ignited interest in the immune and viral events which occur during the transition between these two phases, termed the acute-to-chronic transition phase. We hypothesize that this acute-to-chronic transition phase is indeed the most crucial period, and how the host immune response deals with this transition predicts the overall outcome of the disease. The approach of this review is to focus on this acute-to-chronic transition phase with a specific emphasis on understanding how different immune cell populations are impacting the level of systemic immune activation and which are functionally altered following the acute phase immune activation. The events driving the suppressed immune activation observed during the chronic phase of SIV infection in natural hosts are likely the result of a long evolutionary adaptation enabling these monkeys to live in symbiosis with their specific SIV strains. If elucidated, these evolutionary lessons regarding how to reduce the immune activation in natural SIV host species may inform the next generation of therapies and vaccines for HIV patients.

Immune Activation and Activation induced cell death during acute infection

Comparative studies of nonpathogenic and pathogenic HIV/SIV infections have offered strong support for the role of immune activation in HIV/SIV disease pathogenesis. Early descriptions of immune activation in HIV-infected patients included high levels of plasma IFN-α, increased expression of the IL-2 receptor on lymphocytes, and increased expression of the activation markers CD38 and HLA-DR on CD8+ T cells [20, 21]. These abnormalities are found at elevated levels in HIV-infected patients and are highest in patients at more advanced stages of disease [20]. Indeed, Giorgi et al. found that HIV-related disease progression was more closely correlated with the levels of CD8+ T cell activation than with viral load [1, 21]. Presently, HIV/SIV induced cellular proliferation, activation, and/or dysfunction has been described in many different immune subsets during pathogenic SIV/HIV infection, including T cells, B cells, NK cells, macrophages, and neutrophils [22-25]. The causes of this widespread immune cell activation are likely multi-factorial and include both the direct and indirect effects of the virus and viral proteins, the depletion and dysfunction of regulatory immune cells, and peripheral immune cell stimulation by bacterial products translocating from the intestinal lumen (reviewed in detail in [3]). Signs of immune activation are evident very early in the course of lentiviral infection [9, 18]. Within 1-5 weeks post infection, both progressive and nonprogressive hosts experience increases in T cell proliferation and immune activation. Initial studies of SIV infection in natural hosts utilized samples obtained during chronic infection or in vitro assays and therefore did not detect these early activation responses [26-28]. However, analyses with more frequent and earlier sampling demonstrated that SIV infection in natural hosts leads to increases in T cell proliferation and activation within T cell subsets by one week post infection [29-31]. More recent studies have utilized comparative genomics to probe the molecular events occurring during acute infection of both pathogenic and nonpathogenic SIV infections. Several of these studies have identified that interferon stimulated genes (ISGs) are upregulated early in both nonprogressing natural hosts and progressing macaque models. Importantly, however, ISG expression is differentially resolved during pathogenic and nonpathogenic infections. For example, SIV infected AGMs show a reduced ISG expression in blood and lymph nodes to near pre-infection levels by day 28 post-infection, while macaques maintain elevated expression into chronic timepoints [9, 29]. Similarly, Lederer et al. observed that both PTMs and AGMs experienced upregulation of IFN-α signaling at day 10 post infection, but only AGMs resolved this response by day 45 [32]. Likewise, SIV-infected SMs experienced early increases in RIG-I, IRF-3, and IRF-7 [33]. These genomic findings were recently corroborated by immunohistochemical and immunofluorescent analyses demonstrating an acute phase robust IFN-α response in the LN of SMs, AGMs, and RMs that is later resolved only in SMs and AGMs [9].

Microarray studies have also revealed that both progressive and nonprogressive hosts experience dramatic changes in the expression of genes associated with initiating innate and adaptive immune responses. For example, during acute SIV infection of SMs and RMs, Bosinger et al. detected widespread upregulation of genes involved in cellular immunity, such as granzyme A, immunoglobulin genes, and chemokines responsible for T cell trafficking [33]. However, expression of this gene family resolved to baseline levels during chronic infection of SMs, whereas expression remained elevated in chronically infected RMs. There are also key differences in the acute phase immune response between pathogenic and nonpathogenic infections which suggest that the magnitude and quality of this early response contribute to the ultimate disease outcome. A comparison of acute and chronic timepoints among AGMs and PTMs in the LN, blood, and colon, revealed that PTMs have higher expression of genes involved in oxidative stress, apoptosis, and inflammation, including neutrophil chemotaxis and degranulation, and chemokines such a CXCL9 and CXCL10 [32]. The increase in these gene transcripts at day 10 in PTMs correlated with higher levels of CD8+ T cell proliferation, one measure of an immune activated environment [32]. In contrast, AGMs had higher expression of genes involved in modulating the cell cycle, and restricting both inflammation and Th1 responses, including IL-10. Similar results were seen in SMs, in which the genes for immunoregulatory proteins which contribute to controlling T cell proliferation and activation, such as CD274/PDL1 and IDO1/INDO, were upregulated at days 7 and 10 post infection [8, 33]. While these studies have demonstrated that immunologic events of acute infection are not identical in nonpathogenic and pathogenic hosts, they have clearly established that SIV infection in both hosts results in an initial robust immune activation response, composed primarily of type I IFN responses [29, 32, 33]. Yet only the natural hosts, which go on to a nonpathogenic disease course, resolve the initial activation during the transition to chronic infection.

A close correlate of T cell activation and another distinctive characteristic of nonpathogenic SIV infections is the degree of T cell apoptosis. Both SMs and RMs experience an increase in CD8+ T cell apoptosis during the acute phase of SIV infection that corresponds with the development of cell-mediated immunity, including an increase in SIV-specific IFN-γ-producing cells [16]. However, SMs maintain low levels of peripheral CD3+/CD4+ and CD3+/CD4neg/CD8neg T cell apoptosis throughout acute and chronic infection relative to RMs [16]. The observation that RMs, but not SMs, experience increases in peripheral T cell apoptosis during acute SIV infection despite similar viral loads suggests that viral replication alone cannot account for this differential response in apoptotic T cell levels [16]. In the LN, both SMs and RMs show increases in CD4+ and CD8+ T cell apoptosis during the first 2-12 weeks of SIV infection. During this time, T cell apoptosis levels correlate with T cell activation, suggesting that acute infection results in activation-induced apoptosis [16]. By week 23, however, SMs resolve these increases to pre-infection levels while RMs maintain elevated levels of LN T cell apoptosis [16]. AGMs may regulate apoptosis more strictly during SIV infection, as there was no detectable increase in apopototic cells in the LN at early time points [34]. The low levels of chronic phase T cell activation and apoptosis in SIV-infected natural hosts has been correlated with differences in both viral and immunologic factors. With regard to virologic determinants, Schindler et al. demonstrated that nef proteins from SIV strains that infect African monkeys are able to down-modulate T cell receptor-CD3 complexes on the surface of CD4+ T cells, resulting in lower susceptibility of these cells to activation and apoptosis [35]. Remarkably, all HIV-1 groups (M, N, and O) express nef proteins which have lost this ability [35]. With regard to immunologic determinants, differential upregulation of the membrane receptor programmed death 1 (PD1) in lymph nodes of acutely infected SM hosts [8] and increased expression of the apoptosis inducing protein TRAIL in human but not SM antigen presenting cells [36] identify two of these key features.

Adaptive Immune Cells

CD4+ T cells

CD4+ T cells serve a key role in eliciting both the humoral and cellular immune responses and are likely to play an important role in HIV/SIV-induced immunologic activation. Their role in shaping the adaptive immune response makes them a potential source of immune activation, as the antiviral immune response is persistent and dynamic in the context of a chronic infection such as HIV/SIV. Moreover, the ability of these cells to produce inflammatory cytokines/chemokines adds to their potential to mediate immune activation. Of course, the potential contributions of this cell population to immune activation are balanced by the fact that CD4+ T cells are also depleted by HIV/SIV infection as well as the ability of some CD4+ T cell subsets such as regulatory T cells to reduce immune activation.

The assessment of CD4 depletion following SIV infection in the natural host models provides insights to the similarities and differences between pathogenic and nonpathogenic infections. During the acute phase of SIV infection a decrease in CD4+ T cell levels can be observed associated with the early peak in viral replication in both SMs and AGMs [37, 38]. Still, these reduced CD4+ T cell levels are generally within the ‘healthy’ range (above 500 cells/ul of blood) for SIV-infected SMs and are normally maintained throughout the disease course [18, 28]. In SIV-infected AGMs, CD4+ T cell levels generally rebound to near baseline levels during the transition from acute to chronic infection, providing further evidence for the immune recovery that occurs during this phase of the infection [19, 30]. In contrast, the CD4+ T cells within the gut associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) of SMs and AGMs undergo a rapid decrease following SIV infection, similar to that observed during pathogenic infections [19, 37]. Indeed, the GALT CD4+ T cells remain low throughout the chronic phase of the infection in natural host infections. One might hypothesize that in the context of massive GALT CD4+ T cell depletion maintaining the peripheral blood and lymph node associated CD4+ T cells is sufficient for maintaining low levels of immune activation. However, a subset of SIV+ SMs experience global CD4+ T cell depletion (<100 cells/ul of blood). These CD4-low SMs can be found within the naturally SIV-infected SM colony at the Yerkes primate center [39, 40] as well as within a cohort of mangabeys infected via SIV plasma transfer that subsequently developed a multitropic (CCR5/CXCR4/CCR8) infection [17]. Importantly, the depletion of CD4+ T cells in the peripheral blood, lymph nodes and GALT in these mangabeys did not result in any evidence of immune activation and no clinical signs of simian AIDS. Similarly low levels of CD4+ T cells have been observed in AGMs irrespective of SIV infection with no influence on immune competency [38]. Therefore, the preservation of total CD4+ T cell levels is not required to maintain low levels of immune activation in the SIV-infected natural host monkey species.

The identification of SIV-infected natural hosts that remain free of simian AIDS even when CD4+ T cell levels are below levels normally considered to be ‘AIDS defining’ was difficult to reconcile with the central role of CD4+ T cells in the immune system. Recent findings have begun to unravel how the natural hosts are able to maintain low levels of immune activation and healthy immune systems even when the CD4+ T cell levels are depleted. First, there may be a shift in which cells are infected in natural hosts due to the significantly low levels of CCR5 coreceptor expression on some subsets of CD4+ T cells in natural SIV hosts [3, 11, 41]. This low level of CCR5 expression may restrict the replication to CD4+ T cells that are in a more advanced stage of activation and/or differentiation to effectors. As such, restricted and delayed expression of CCR5 on activated CD4+ T cells may preserve the homeostasis of the pool of “resting” naïve and memory CD4+ T cells while supporting high levels of virus production. In this way only the effector CD4 cells are activated and therefore likely to die as a consequence of activation-induced cell death (AICD) [5]. It follows that the preserved pool of naïve and central memory T cells would be available to replenish the effector memory T cells, which would provide a continuous source of these important helper T cells capable of contributing to immune responses to both SIV and other pathogens, as well as a steady source of viral target cells [11, 42]. Second, there may be cells in the natural host that can perform functions of CD4+ T cells but do not express the CD4 protein on their surface, such as the double negative T cells identified in AGMs and SMs [17, 43]. The presence of these CD3+ cells that are refractory to infection (due to no CD4 protein), yet perform functions of CD4+ T cells, represent yet another adaptation for how the natural hosts have evolved to circumvent simian AIDS even after many years of SIV infection. Third, although the GALT CD4+ T cells are depleted during the acute phase of SIV infection of natural hosts, this CD4 depletion is qualitatively different from that observed during pathogenic HIV/SIV infection [6, 44, 45]. In particular, it may be the preferential preservation of Th17 T cells that might be critical for maintaining mucosal health in SIV infected natural hosts [6, 44, 45]. In summary, these findings regarding CD4 and CD4-like T cell populations suggest that natural hosts have methods for preserving their critical helper T cell populations.

Analysis of the acute-to-chronic phase shift in the immune activation response would not be complete without consideration for the role of regulatory T cells (T-regs). Indeed studies have found maintained or increased levels of T-regs during acute SIV infection of natural hosts [30]. Kornfeld et al. found increases in Foxp3 gene expression concurrent with increased plasma TGF-β within 24 hours of SIV infection of AGMs. This early increase was followed by an increase in plasma IL-10 at day 6. Possibly, the presence of T-reg cells early during SIV infection contributes to establishing an anti-inflammatory environment during acute infection which suppresses the immune activation at later stages [30]. However, there is no direct correlation between T-reg levels and the resolution of immune activation in natural hosts [8]. As such, both PTMs and AGMs experience increases in lamina propria T-regs at the same time as colonic immune activation increases (45 dpi), suggesting that these cells are not controlling immune activation in either pathogenic or nonpathogenic infection [45]. It may be that during acute pathogenic infection the ratio of T-reg to other cell subsets is most important [45]. In SIV-infected PTMs, a specific depletion of Th17 cells and a concurrent increase in FoxP3+ T-regulatory cells during the first 10 days of infection led to a perturbed ratio of these subsets. By day 45, PTMs with lower Th17:T-reg ratios had higher levels of T cell activation. In contrast, both Th17 and T-reg cells were preserved in SIV-infected AGMs and there was no correlation between the Th17:T-reg ratio and T cell activation. A similar preservation of Th17 cells was observed in the blood and GI tract of SIV-infected SMs whereas HIV patients had significant depletions in this subset [44]. These findings suggest a potential role for the CD4+ T-reg cells as well as Th17 cells, although it is likely that both the timing of the T-reg activation as well as the cellular milieu that is present will influence the ability of these subsets to elicit a beneficial or detrimental effect with regard to acute-to-chronic phase immune suppression as well as the disease outcome.

CD8+ T cells

CD8+ T cells might also provide key immune functions during the resolution of immune activation during the acute to chronic phase transition. Indeed, a role for CD8+ T cells in controlling HIV/SIV infection has been well documented, including evidence that: (1) autologous CD8+ T cells are able to suppress ex vivo HIV replication [46]; (2) there is a temporal correlation between the development of antiviral CD8+ T cells and post-peak viral decline [47]; and (3) depletion of CD8+ cells in the SIV macaque model resulted in rapid increases in viral replication [48]. In natural hosts, the contribution of CD8+ T cells is less clear. Recently, Schmitz et al. assessed the contribution of adaptive immune responses to a nonpathogenic outcome by administering antibodies to deplete both CD8+ and CD20+ cells during the first two weeks of SIVagmVer90 infection in PTMs and AGMs [49]. This dramatic depletion of the effector cells responsible for both arms of adaptive immunity had dramatically different outcomes in the two species. PTMs experienced a one-log increase in peak viral loads and approximately a four-log increase in set point viral loads following lymphocyte depletion. These animals exhibited rapid disease progression, including CMV reactivation. In contrast, depletion of CD8+ and CD20+ cells in AGMs had no effect on peak viral load and only a small delay in post-peak decline compared to control animals and all AGMs remained clinically healthy [49]. A similar delay in post-peak viral decline was observed in a separate study in which CD8+ cells were depleted during acute SIV infection of AGMs [50]. Importantly, these studies demonstrate that delaying the initiation of CTL and antibody responses has no impact on the nonpathogenic outcome in SIV-infected natural hosts. These findings are supported by earlier studies demonstrating that the magnitude of SIV-specific adaptive immune responses is comparable between natural hosts and pathogenic HIV/SIV-infected hosts and that depletion of CD8+ T cells in SIV-infected SMs has a limited effect on viral load [7, 16, 50-52]. Moreover, these studies indicate that while adaptive immune responses, including CD8+ CTL responses, likely play a larger role in non-natural hosts such as macaques and humans, they represent only one aspect of the host immune response to SIV. Overall, these findings would not support a major role for SIV-specific CD8+ T cells in the down-modulation of immune activation between the acute and chronic phases of natural SIV infection. However, recent findings by Klatt et al. assessing the mechanism by which CD8+ T cells control viral replication in SIV infected RMs indicated that key anti-SIV CD8+ T cell functions are not associated with a shorter half life of infected CD4+ T cells, suggesting that direct cell killing is not the primary means of action employed by SIV-specific CTL [53]. Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that cytokine production or other non-CTL functional activities by CD8+ T cells contribute to the acute to chronic transition phase of natural hosts.

Additional T cell subsets: Natural Killer T cells, γδ T cells and Double Negative (DN) T cells

There are other T cell subsets that could potentially serve key roles in the acute to chronic phase transition of the immune activation observed in the SIV infected natural host species. Natural killer T (NKT) cells are a relatively small subset of T cells that express both CD3 and the NK receptor CD16 and recognize non-peptide antigens presented by non-polymorphic MHC class I-like molecules (CD1d). Multiple NKT cells have been identified, the best characterized being the invariant NKT lymphocytes which are defined as expressing only one TCR α chain (Vα24 in humans) and a limited number of TCR β chains [54]. Upon activation of NKT cells by glycolipids presented by CD1d proteins, NKT cells produce a diverse array of cytokines including IL-10, TGF-β as well as those influencing the Th1 and Th2 pathway [55]. In SMs, NKT cells can express the CD8 protein or can be CD4neg/CD8neg, but they do not express the CD4 protein, making them resistant to SIV/HIV infection similar to RMs and humans [56-58]. NKT cells in SMs have been shown to produce a number of cytokines including the anti-inflammatory mediator IL-10, implicating these cells in the low level of immune activation observed in the SIV+ SMs [59]. In addition, an early increase in IL-17 production by NKT cells in the LN was recently found to be associated with subsequent progression to simian AIDS in RMs [60]. IL-17 production peaked at 14 days post-infection in the RMs, and was correlated with increased IL-18 and TGF-β production. Moreover, these cytokines were continuously produced during chronic infection of non-controlling RMs [60]. In contrast, SIV-infected AGMs did not exhibit any increase in IL-17 production in the LN during acute infection [60]. These data suggest a potential role for IL-17 in promoting immune activation during the acute to chronic transition phase of pathogenic HIV/SIV infections.

A second interesting T cell subset is the gammadelta (γδ) T cells, which play key roles in innate immunity and the initiation of adaptive immune responses. In humans, γδ T cells comprise a relatively minor subset (1 – 5% on average) of circulating T cells, but may represent as much as 50% of the T cells present within the mucosal associated lymphoid tissue [61]. γδ T cells can produce both Th1 and Th2 cytokines, thereby influencing adaptive immune responses [7]. Two main γδ T cell subsets exist as defined by the expression of one of two δ variable region, Vδ1 or Vδ2. The Vδ1+ γδ T cells are found predominately at mucosal sites and can respond to non-classical MHC molecules expressed on stressed cells, while Vδ2+ γδ T cells are predominately in the peripheral circulation and respond to non-peptide phosphoantigens [62]. γδ T cells are influenced by HIV infection as evidenced by a phenotypic switch from predominately Vδ2 before infection, to predominately Vδ1 within the peripheral blood of HIV+ patients [63]. Following an oral SIV infection, decreased γδ T cell levels were observed at the oral and esophageal mucosa, while increased γδ T cell levels were observed in the lymph nodes of RMs [64]. γδ T cells have also been assessed in SIV-infected SMs with regard to their ability to express cytokines following a mitogenic or phosphoantigen stimulation [65]. The SM γδ T cells maintain or increase their ability to produce IFN-γ or TNF-α following stimulation, whereas human γδ T cells exhibit a decreased cytokine response following HIV-infection [65].

A third interesting subset of T cells are phenotypically identified as CD3+/CD4neg/CD8neg or CD4/CD8-double negative (DN) T cells. DN T cells have α/β T cell receptors and are not invariant NKT cells due to their diverse usage of T cell receptor loci. Some studies in mice have suggested that DN T cells are a form of regulatory T cells, however other studies have attributed effector type functions to DN T cells [66, 67]. Interestingly, AGMs contain DN T cells that are CD8α-dim at relatively high frequencies regardless of SIV status [4]. Beaumier et al. found that these DN CD8α-dim T cells display predominately an effector phenotype and that they arise following downmodulation of the CD4 molecule on CD4+ T cells [4]. Notably, these DN CD8α-dim T cells retain helper T cell function, including IL-2 and IL-17 production, are MHC class II-restricted, and are resistant to SIV infection [4]. DN T cells from SMs do not display the CD8α protein on their surface [17], however, the levels of DN T cells in SMs are relatively high and these levels are not altered following SIV infection [17]. The observation that some SIV-infected SMs could survive with very low CD4+ T cell levels (CD4-low) and no evidence of clinical disease suggests that these DN T cells could potentially perform CD4 helper T cell functions [17]. In contrast to natural hosts, SIV-infected RMs experience high rates of DN T cell apoptosis as early as one week post infection [16]. The presence of DN T cells in SIV natural hosts identifies a cell type with the potential to impact disease progression due to their resistance to SIV infection and potential to perform T helper cell functions. Further studies are needed to identify the role of this, or any of these understudied T cell subsets, in the suppression of immune activation that occurs during the acute to chronic transition phase of SIV infection.

Innate Immune Cells

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) are likely among the first responders to lentiviral infection. Their unique signature of pattern recognition receptors, including TLR7, 8, and 9, as well as their capacity to produce more type I interferon on a per cell basis than any other immune cell demonstrates that they are built to respond quickly to viral infections. Indeed, pDCs have been shown to play a role in the earliest stages of HIV/SIV infections [68]. During the first two weeks of pathogenic SIV infection, increased levels of circulating pDCs are followed by transient decreases with the nadir occurring at two weeks post infection [68]. Concurrent with the decline of pDCs in the blood, pDC numbers increase in lymph nodes and plasma IFN-α levels reach their peak, suggesting that pDCs traffic to the LN, where they encounter high levels of virus [68]. In AGMs, the first weeks of SIV infection result in a transient decrease in the absolute numbers of blood pDCs with a return to baseline by 42 d.p.i. The decreases in blood pDC levels during acute SIVagm infection were found to have a temporal association with increases in lymph nodes [69]. Just as in pathogenic infection, plasma IFN-α levels increase early in SIV-infected AGMs [69]. pDC kinetics are similar in pathogenic and nonpathogenic SIV infection, although the magnitude of IFNa-producing cells is lower in AGMs [70]. In SIV-infected RMs, there is no correlation between the numbers of SIV+ cells and IFNa+ cells in the LN, suggesting that the virus is not the only driving force behind pDC IFNa-production during pathogenic infection [70]. One factor that may assist SMs in achieving this is the reduced sensitivity to TLR7/9 stimili [71], however pDCs from SIV-infected AGMs display considerable sensing of viral TLR7/8 and TLR9 ligands, producing levels of type I IFN comparable to RMs during the acute infection [9, 69, 70]. Downmodulation of aberrant IFN-α production by pDCs following acute infection of SIV natural host species may be critical for avoiding elevated levels of global immune activation during the chronic phase of infection [9]. These data identify clear correlates with regard to a role for pDCs and IFN-α in the resolution of the acute phase immune activation event in SIV-infected natural hosts.

Natural Killer Cells

Natural Killer (NK) cells were initially identified as an immune cell subset with potent cytotoxic activity against cells that do not express MHC or display altered MHC molecules that result from viral infection or transformation. There have been a number of studies assessing the phenotypic and functional differences between natural killer (NK) cells found in SIV-infected monkeys. Phenotypic changes in the NK cell populations following SIV infection of RMs have indicated that NK cells can be grouped based on their expression of CD16 and CD56, and each subset has different functional characteristics [72]. In addition, there is evidence that following SIV infection NK cells traffic away from secondary lymph nodes [72] possibly due to the change in surface proteins, from those that traffic NK cells to lymph nodes (CCR7) to those that target NK cells to the gut mucosa (α4β7) [73]. Specifically, in uninfected SMs, the major subset of NK cells (CD16+ CD56neg) exhibit higher ex vivo cytolytic activity relative to uninfected RMs [24]. Additionally, CD16− CD56+ NK cells from uninfected SMs were found to have higher IFN-γ and IL-2 responses to mitogenic stimulation than uninfected RMs [74]. The higher baseline NK cell activity in SMs may contribute to a rapid, robust response to SIV, as SMs display an increase in the frequency and function of these cells during acute infection [24]. Moreover, SM NK cells were found to have lower expression of the inhibiting receptor NKG2A than RMs, suggesting that the profile of activating and inhibiting receptors may contribute to the enhanced NK cell performance in SMs [24]. Taken together, these findings suggest a role for NK cells in the acute phase of nonpathogenic infection. It is tempting to speculate that NK cells contribute to controlling early viral replication by eliminating infected cells that display reduced MHC class I expression. This idea is supported by experiments in which CD8-depletion (which targets both CD8+ T cells and NK cells) results in a delayed post-peak decline of viral replication in natural hosts. It is possible that bringing early viral replication down to a lower set point is critical for the resolution of acute phase immune activation.

Cells that promote inflammation: neutrophils, mDCs, Monocytes/Macrophages

Neutrophils and monocyte-derived dendritic cells (mDCs) are two understudied immune cell subsets with role in inflammation that have the potential to influence the acute to chronic phase immune activation changes. Neutrophils play a key role in defense against invading pathogens by promoting inflammation by recruiting and activating other immune cells. The role of neutrophils in SIV disease has not been fully elucidated. Elbim et al. demonstrated that AGMs infected with SIVagm display no difference in neutrophil apoptosis during acute infection compared to baseline [22]. Conversely, during acute infection SIV-infected RMs had significantly higher levels of neutrophil apoptosis, resulting in neutropenia, which was highly correlated with viral load and disease progression [22]. Additionally, they found that this phenotype was associated with higher expression of the SIV coreceptor BOB/GPR15 on the surface of neutrophils, suggesting that non-infectious binding of SIV to BOB/GPR15 on neutrophils may induce bystander apoptosis of the cells. In addition, increased neutrophil apoptosis continued throughout the chronic phase of infection and was not observed with a non-pathogenic SIVdeltanef strain [75]. This apoptosis was significantly increased in macaques that progressed faster to sAIDS compared to non-progressors [75]. Interestingly, in chronically-infected macaques, the percentage of apoptotic cells correlated with PMN activation state reflected by increased CD11b expression and reactive oxygen species production [75].

With regard to mDCs, little is known about their in vivo role in influencing immune activation. However, it has been shown in vitro that AGM mDCs are unable to undergo a complete maturation process and are weak T cell stimulators, in contrast to mDCs cultured from RMs and humans [76]. Further, this inability was associated with a higher ratio of anti-inflammatory (IL-10) vs. pro-inflammatory (IL-12, IFN-γ, TNF-α) cytokine production during mixed lymphocyte reactions compared to human mDC [76]. It has been shown that during pathogenic HIV and SIV infections, mDC numbers decrease in the peripheral blood, possibility resulting from increased homing to LNs [77, 78]. However, a study by Brown et al. demonstrated that both mDCs and pDCs were depleted in parallel from blood as well as lymph nodes and spleens in monkeys with simian AIDS [79].

Despite the early identification of macrophages as targets and reservoirs for HIV infection, still little is known about these cells in the context of HIV/SIV-associated immune activation. Both macrophages and their blood precursor monocytes have the potential to contribute to the pro-inflammatory cytokine profile characteristic of HIV infection (reviewed [80]). For example, increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, like IL-1 and TNF-α have been found in monocytes from HIV-infected subjects [81] and IL-1, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8 production been found to be increased in HIV-infected monocyte-derived macrophages [82]. It has recently been reported that exposure of monocytes to HIV-1 or HIV-1-derived single-stranded RNA sequences sensitized these cells for TLR4 stimulation, resulting in a significantly higher TNF-α production by monocytes in response to LPS [83]. These results may have important implications in the context of immune activation resulting from the transolcation of microbial products from the gut lumen [43]. Further, monocytes and macrophages have been implicated in HIV-associated dementia, both through the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α which weaken the blood brain barrier, and by contributing to the spread of infection through potential trafficking of infected monocytes into the central nervous system [84]. Hence, the importance of monocytes and macrophages as both targets for HIV/SIV infection and as mediators of inflammation suggest these cells may play critical roles in the immune activation events following the acute phase of infection.

Future studies are warranted to determine the importance of the cells types that promote inflammation in the acute-to-chronic phase resolution of immune activation that is observed in natural host species but not in pathogenically SIV-infected animals.

Implications for HIV-infected patients

The role of inflammation and immune activation in the disease outcome of HIV infection has been demonstrated in numerous studies [1, 43]. An additional clear indicator of the consequence of immune activation is the distinct disease outcome observed in SIV-infected natural host species that maintain low chronic immune activation [3, 10, 11, 28]. This review focuses on a major finding uncovered through microarray and other analyses: that the acute phase of infection is virologically and immunologically quite similar among both natural and pathogenic hosts while the levels of immune activation during the chronic phase comprise one of the largest differences between the two disease outcomes [29, 32, 33, 85]. This observation has led to a logical focus on the immune events occurring during the transition from acute to chronic infection, with the underlying hypothesis being that those events are critical for establishing either a pathogenic or nonpathogenic disease course. Elucidating the contributions of specific immune cell subsets to this transition will likely identify novel targets for immunotherapies and vaccines, such as which immune cell functions to bolster or suppress, and which cytokines/chemokines to augment or block. And while SIV-infected natural hosts have evolved to transition from a state of high immune activation to one of low immune activation following the first few weeks of infection, the benefits of this transition are likely not limited to such an early time period. Indeed, an effective therapeutic capable of reducing immune activation, either alone or in combination with anti-retroviral therapy, would be predicted to benefit chronically HIV-infected patients regardless of the duration of infection. Moreover, a vaccine designed to allow for an acute phase increase in immune activation while inducing a transitional resolution of aberrant immune activation could possibly allow for HIV-infected individuals to live normal, healthy lives free from opportunistic infections and AIDS, analogous to the natural hosts of SIV.

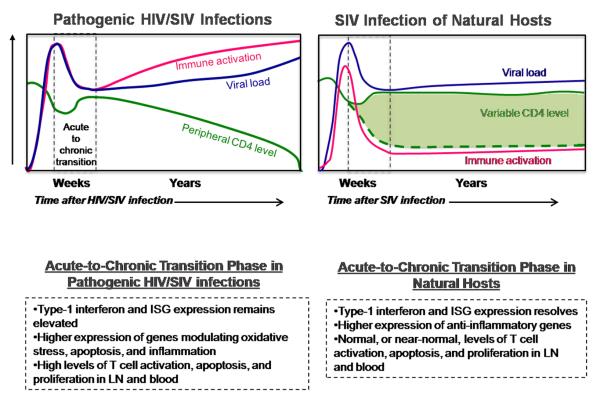

Figure 1.

Figure summarizes the differences between pathogenic HIV/SIV infections SIV and natural host monkey species; specifically with regard to the acute-to-chronic transition phase following an SIV or HIV infection. Within the graphs the blue line represents typical viral load levels, the green line and shaded green area represent typical CD4 levels, the red line represents general systemic immune activation which can be measured in a number of ways including the activation state of the immune cells and levels of interferon stimulated genes (ISGs). Vertical dotted lines indicate the time of acute-to-chronic transition which generally occurs between approximately 21 and 40 days. Some specific differences in the acute-to-chronic phase between pathogenic and natural host infections are listed within the dashed boxes below the graphs.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Guido Silvestri, Steve Bosinger, and Michaela Muller-Trutwin for critical reading and helpful suggestions regarding this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Giorgi JV, Hultin LE, McKeating JA, Johnson TD, Owens B, Jacobson LP, Shih R, Lewis J, Wiley DJ, Phair JP, Wolinsky SM, Detels R. Shorter survival in advanced human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection is more closely associated with T lymphocyte activation than with plasma virus burden or virus chemokine coreceptor usage. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:859–870. doi: 10.1086/314660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Orendi JM, Bloem AC, Borleffs JC, Wijnholds FJ, de Vos NM, Nottet HS, Visser MR, Snippe H, Verhoef J, Boucher CA. Activation and cell cycle antigens in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells correlate with plasma human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) RNA level in HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1279–1287. doi: 10.1086/314451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Sodora DL, Silvestri G. Immune activation and AIDS pathogenesis. AIDS. 2008;22:439–446. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f2dbe7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Beaumier CM, Harris LD, Goldstein S, Klatt NR, Whitted S, McGinty J, Apetrei C, Pandrea I, Hirsch VM, Brenchley JM. CD4 downregulation by memory CD4+ T cells in vivo renders African green monkeys resistant to progressive SIVagm infection. Nat Med. 2009;15:879–885. doi: 10.1038/nm.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Brenchley JM, Silvestri G, Douek DC. Nonprogressive and progressive primate immunodeficiency lentivirus infections. Immunity. 2010;32:737–742. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cecchinato V, Trindade CJ, Laurence A, Heraud JM, Brenchley JM, Ferrari MG, Zaffiri L, Tryniszewska E, Tsai WP, Vaccari M, Parks RW, Venzon D, Douek DC, O’Shea JJ, Franchini G. Altered balance between Th17 and Th1 cells at mucosal sites predicts AIDS progression in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1:279–288. doi: 10.1038/mi.2008.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Dunham R, Pagliardini P, Gordon S, Sumpter B, Engram J, Moanna A, Paiardini M, Mandl JN, Lawson B, Garg S, McClure HM, Xu YX, Ibegbu C, Easley K, Katz N, Pandrea I, Apetrei C, Sodora DL, Staprans SI, Feinberg MB, Silvestri G. The AIDS resistance of naturally SIV-infected sooty mangabeys is independent of cellular immunity to the virus. Blood. 2006;108:209–217. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-4897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Estes JD, Gordon SN, Zeng M, Chahroudi AM, Dunham RM, Staprans SI, Reilly CS, Silvestri G, Haase AT. Early resolution of acute immune activation and induction of PD-1 in SIV-infected sooty mangabeys distinguishes nonpathogenic from pathogenic infection in rhesus macaques. J Immunol. 2008;180:6798–6807. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.10.6798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Harris LD, Tabb B, Sodora DL, Paiardini M, Klatt NR, Douek DC, Silvestri G, Muller-Trutwin M, Vasile-Pandrea I, Apetrei C, Hirsch V, Lifson J, Brenchley JM, Estes JD. Downregulation of robust acute type I interferon responses distinguishes nonpathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection of natural hosts from pathogenic SIV infection of rhesus macaques. J Virol. 2010;84:7886–7891. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02612-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Pandrea I, Sodora DL, Silvestri G, Apetrei C. Into the wild: simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection in natural hosts. Trends Immunol. 2008;29:419–428. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sodora DL, Allan JS, Apetrei C, Brenchley JM, Douek DC, Else JG, Estes JD, Hahn BH, Hirsch VM, Kaur A, Kirchhoff F, Muller-Trutwin M, Pandrea I, Schmitz JE, Silvestri G. Toward an AIDS vaccine: lessons from natural simian immunodeficiency virus infections of African nonhuman primate hosts. Nat Med. 2009;15:861–865. doi: 10.1038/nm.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sharp PM, Hahn BH. The evolution of HIV-1 and the origin of AIDS. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2010;365:2487–2494. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Diop OM, Gueye A, Dias-Tavares M, Kornfeld C, Faye A, Ave P, Huerre M, Corbet S, Barre-Sinoussi F, Muller-Trutwin MC. High levels of viral replication during primary simian immunodeficiency virus SIVagm infection are rapidly and strongly controlled in African green monkeys. J Virol. 2000;74:7538–7547. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.16.7538-7547.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gueye A, Diop OM, Ploquin MJ, Kornfeld C, Faye A, Cumont MC, Hurtrel B, Barre-Sinoussi F, Muller-Trutwin MC. Viral load in tissues during the early and chronic phase of non-pathogenic SIVagm infection. J Med Primatol. 2004;33:83–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2004.00057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Klatt NR, Villinger F, Bostik P, Gordon SN, Pereira L, Engram JC, Mayne A, Dunham RM, Lawson B, Ratcliffe SJ, Sodora DL, Else J, Reimann K, Staprans SI, Haase AT, Estes JD, Silvestri G, Ansari AA. Availability of activated CD4+ T cells dictates the level of viremia in naturally SIV-infected sooty mangabeys. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2039–2049. doi: 10.1172/JCI33814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Meythaler M, Martinot A, Wang Z, Pryputniewicz S, Kasheta M, Ling B, Marx PA, O’Neil S, Kaur A. Differential CD4+ T-lymphocyte apoptosis and bystander T-cell activation in rhesus macaques and sooty mangabeys during acute simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol. 2009;83:572–583. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01715-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Milush JM, Reeves JD, Gordon SN, Zhou D, Muthukumar A, Kosub DA, Chacko E, Giavedoni LD, Ibegbu CC, Cole KS, Miamidian JL, Paiardini M, Barry AP, Staprans SI, Silvestri G, Sodora DL. Virally induced CD4+ T cell depletion is not sufficient to induce AIDS in a natural host. J Immunol. 2007;179:3047–3056. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Muthukumar A, Wozniakowski A, Gauduin MC, Paiardini M, McClure HM, Johnson RP, Silvestri G, Sodora DL. Elevated interleukin-7 levels not sufficient to maintain T-cell homeostasis during simian immunodeficiency virus-induced disease progression. Blood. 2004;103:973–979. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Pandrea IV, Gautam R, Ribeiro RM, Brenchley JM, Butler IF, Pattison M, Rasmussen T, Marx PA, Silvestri G, Lackner AA, Perelson AS, Douek DC, Veazey RS, Apetrei C. Acute loss of intestinal CD4+ T cells is not predictive of simian immunodeficiency virus virulence. J Immunol. 2007;179:3035–3046. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Fuchs D, Hausen A, Hengster P, Reibnegger G, Schulz T, Werner ER, Dierich MP, Wachter H. In vivo activation of CD4+ cells in AIDS. Science. 1987;235:356. doi: 10.1126/science.3099388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Giorgi JV, Ho HN, Hirji K, Chou CC, Hultin LE, O’Rourke S, Park L, Margolick JB, Ferbas J, Phair JP. CD8+ lymphocyte activation at human immunodeficiency virus type 1 seroconversion: development of HLA-DR+ CD38− CD8+ cells is associated with subsequent stable CD4+ cell levels. The Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study Group. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:775–781. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.4.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Elbim C, Monceaux V, Mueller YM, Lewis MG, Francois S, Diop O, Akarid K, Hurtrel B, Gougerot-Pocidalo MA, Levy Y, Katsikis PD, Estaquier J. Early divergence in neutrophil apoptosis between pathogenic and nonpathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus infections of nonhuman primates. J Immunol. 2008;181:8613–8623. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Mohri H, Bonhoeffer S, Monard S, Perelson AS, Ho DD. Rapid turnover of T lymphocytes in SIV-infected rhesus macaques. Science. 1998;279:1223–1227. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5354.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Pereira LE, Johnson RP, Ansari AA. Sooty mangabeys and rhesus macaques exhibit significant divergent natural killer cell responses during both acute and chronic phases of SIV infection. Cell Immunol. 2008;254:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Rosenzweig M, DeMaria MA, Harper DM, Friedrich S, Jain RK, Johnson RP. Increased rates of CD4(+) and CD8(+) T lymphocyte turnover in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6388–6393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bostik P, Dodd GL, Ansari AA. CD4+ T cell signaling in the natural SIV host--implications for disease pathogenesis. Front Biosci. 2003;8:s904–912. doi: 10.2741/1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hurtrel B, Petit F, Arnoult D, Muller-Trutwin M, Silvestri G, Estaquier J. Apoptosis in SIV infection. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12(Suppl 1):979–990. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Silvestri G, Sodora DL, Koup RA, Paiardini M, O’Neil SP, McClure HM, Staprans SI, Feinberg MB. Nonpathogenic SIV infection of sooty mangabeys is characterized by limited bystander immunopathology despite chronic high-level viremia. Immunity. 2003;18:441–452. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Jacquelin B, Mayau V, Targat B, Liovat AS, Kunkel D, Petitjean G, Dillies MA, Roques P, Butor C, Silvestri G, Giavedoni LD, Lebon P, Barre-Sinoussi F, Benecke A, Muller-Trutwin MC. Nonpathogenic SIV infection of African green monkeys induces a strong but rapidly controlled type I IFN response. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3544–3555. doi: 10.1172/JCI40093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kornfeld C, Ploquin MJ, Pandrea I, Faye A, Onanga R, Apetrei C, Poaty-Mavoungou V, Rouquet P, Estaquier J, Mortara L, Desoutter JF, Butor C, Le Grand R, Roques P, Simon F, Barre-Sinoussi F, Diop OM, Muller-Trutwin MC. Antiinflammatory profiles during primary SIV infection in African green monkeys are associated with protection against AIDS. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1082–1091. doi: 10.1172/JCI23006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Silvestri G, Fedanov A, Germon S, Kozyr N, Kaiser WJ, Garber DA, McClure H, Feinberg MB, Staprans SI. Divergent host responses during primary simian immunodeficiency virus SIVsm infection of natural sooty mangabey and nonnatural rhesus macaque hosts. J Virol. 2005;79:4043–4054. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.7.4043-4054.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Lederer S, Favre D, Walters KA, Proll S, Kanwar B, Kasakow Z, Baskin CR, Palermo R, McCune JM, Katze MG. Transcriptional profiling in pathogenic and non-pathogenic SIV infections reveals significant distinctions in kinetics and tissue compartmentalization. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000296. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Bosinger SE, Li Q, Gordon SN, Klatt NR, Duan L, Xu L, Francella N, Sidahmed A, Smith AJ, Cramer EM, Zeng M, Masopust D, Carlis JV, Ran L, Vanderford TH, Paiardini M, Isett RB, Baldwin DA, Else JG, Staprans SI, Silvestri G, Haase AT, Kelvin DJ. Global genomic analysis reveals rapid control of a robust innate response in SIV-infected sooty mangabeys. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3556–3572. doi: 10.1172/JCI40115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Cumont MC, Diop O, Vaslin B, Elbim C, Viollet L, Monceaux V, Lay S, Silvestri G, Le Grand R, Muller-Trutwin M, Hurtrel B, Estaquier J. Early divergence in lymphoid tissue apoptosis between pathogenic and nonpathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus infections of nonhuman primates. J Virol. 2008;82:1175–1184. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00450-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Schindler M, Munch J, Kutsch O, Li H, Santiago ML, Bibollet-Ruche F, Muller-Trutwin MC, Novembre FJ, Peeters M, Courgnaud V, Bailes E, Roques P, Sodora DL, Silvestri G, Sharp PM, Hahn BH, Kirchhoff F. Nef-mediated suppression of T cell activation was lost in a lentiviral lineage that gave rise to HIV-1. Cell. 2006;125:1055–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kim N, Dabrowska A, Jenner RG, Aldovini A. Human and simian immunodeficiency virus-mediated upregulation of the apoptotic factor TRAIL occurs in antigen-presenting cells from AIDS-susceptible but not from AIDS-resistant species. J Virol. 2007;81:7584–7597. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02616-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Gordon SN, Klatt NR, Bosinger SE, Brenchley JM, Milush JM, Engram JC, Dunham RM, Paiardini M, Klucking S, Danesh A, Strobert EA, Apetrei C, Pandrea IV, Kelvin D, Douek DC, Staprans SI, Sodora DL, Silvestri G. Severe depletion of mucosal CD4+ T cells in AIDS-free simian immunodeficiency virus-infected sooty mangabeys. J Immunol. 2007;179:3026–3034. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.3026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Pandrea I, Kornfeld C, Ploquin MJ, Apetrei C, Faye A, Rouquet P, Roques P, Simon F, Barre-Sinoussi F, Muller-Trutwin MC, Diop OM. Impact of viral factors on very early in vivo replication profiles in simian immunodeficiency virus SIVagm-infected African green monkeys. J Virol. 2005;79:6249–6259. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.10.6249-6259.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Sumpter B, Dunham R, Gordon S, Engram J, Hennessy M, Kinter A, Paiardini M, Cervasi B, Klatt N, McClure H, Milush JM, Staprans S, Sodora DL, Silvestri G. Correlates of preserved CD4(+) T cell homeostasis during natural, nonpathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus infection of sooty mangabeys: implications for AIDS pathogenesis. J Immunol. 2007;178:1680–1691. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Taaffe J, Chahroudi A, Engram J, Sumpter B, Meeker T, Ratcliffe S, Paiardini M, Else J, Silvestri G. A five-year longitudinal analysis of sooty mangabeys naturally infected with simian immunodeficiency virus reveals a slow but progressive decline in CD4+ T-cell count whose magnitude is not predicted by viral load or immune activation. J Virol. 84:5476–5484. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00039-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Pandrea I, Apetrei C, Gordon S, Barbercheck J, Dufour J, Bohm R, Sumpter B, Roques P, Marx PA, Hirsch VM, Kaur A, Lackner AA, Veazey RS, Silvestri G. Paucity of CD4+CCR5+ T cells is a typical feature of natural SIV hosts. Blood. 2007;109:1069–1076. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-024364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Picker LJ. Immunopathogenesis of acute AIDS virus infection. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Brenchley JM, Price DA, Schacker TW, Asher TE, Silvestri G, Rao S, Kazzaz Z, Bornstein E, Lambotte O, Altmann D, Blazar BR, Rodriguez B, Teixeira-Johnson L, Landay A, Martin JN, Hecht FM, Picker LJ, Lederman MM, Deeks SG, Douek DC. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nat Med. 2006;12:1365–1371. doi: 10.1038/nm1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Brenchley JM, Paiardini M, Knox KS, Asher AI, Cervasi B, Asher TE, Scheinberg P, Price DA, Hage CA, Kholi LM, Khoruts A, Frank I, Else J, Schacker T, Silvestri G, Douek DC. Differential Th17 CD4 T-cell depletion in pathogenic and nonpathogenic lentiviral infections. Blood. 2008;112:2826–2835. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-159301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Favre D, Lederer S, Kanwar B, Ma ZM, Proll S, Kasakow Z, Mold J, Swainson L, Barbour JD, Baskin CR, Palermo R, Pandrea I, Miller CJ, Katze MG, McCune JM. Critical loss of the balance between Th17 and T regulatory cell populations in pathogenic SIV infection. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000295. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Walker CM, Moody DJ, Stites DP, Levy JA. CD8+ lymphocytes can control HIV infection in vitro by suppressing virus replication. Science. 1986;234:1563–1566. doi: 10.1126/science.2431484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Koup RA, Safrit JT, Cao Y, Andrews CA, McLeod G, Borkowsky W, Farthing C, Ho DD. Temporal association of cellular immune responses with the initial control of viremia in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 syndrome. J Virol. 1994;68:4650–4655. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.7.4650-4655.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Schmitz JE, Kuroda MJ, Santra S, Sasseville VG, Simon MA, Lifton MA, Racz P, Tenner-Racz K, Dalesandro M, Scallon BJ, Ghrayeb J, Forman MA, Montefiori DC, Rieber EP, Letvin NL, Reimann KA. Control of viremia in simian immunodeficiency virus infection by CD8+ lymphocytes. Science. 1999;283:857–860. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5403.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Schmitz JE, Zahn RC, Brown CR, Rett MD, Li M, Tang H, Pryputniewicz S, Byrum RA, Kaur A, Montefiori DC, Allan JS, Goldstein S, Hirsch VM. Inhibition of adaptive immune responses leads to a fatal clinical outcome in SIV-infected pigtailed macaques but not vervet African green monkeys. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000691. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Gaufin T, Ribeiro RM, Gautam R, Dufour J, Mandell D, Apetrei C, Pandrea I. Experimental depletion of CD8+ cells in acutely SIVagm-infected African Green Monkeys results in increased viral replication. Retrovirology. 2010;7:42. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-7-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Reina J.M. Lozano, Favre D, Kasakow Z, Mayau V, Nugeyre MT, Ka T, Faye A, Miller CJ, Scott-Algara D, McCune JM, Barre-Sinoussi F, Diop OM, Muller-Trutwin MC. Gag p27-specific B- and T-cell responses in Simian immunodeficiency virus SIVagm-infected African green monkeys. J Virol. 2009;83:2770–2777. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01841-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Wang Z, Metcalf B, Ribeiro RM, McClure H, Kaur A. Th-1-type cytotoxic CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses to simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) are a consistent feature of natural SIV infection in sooty mangabeys. J Virol. 2006;80:2771–2783. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.6.2771-2783.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Klatt NR, Shudo E, Ortiz AM, Engram JC, Paiardini M, Lawson B, Miller MD, Else J, Pandrea I, Estes JD, Apetrei C, Schmitz JE, Ribeiro RM, Perelson AS, Silvestri G. CD8+ lymphocytes control viral replication in SIVmac239-infected rhesus macaques without decreasing the lifespan of productively infected cells. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000747. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Godfrey DI, Kronenberg M. Going both ways: immune regulation via CD1d-dependent NKT cells. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1379–1388. doi: 10.1172/JCI23594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Coquet JM, Chakravarti S, Kyparissoudis K, McNab FW, Pitt LA, McKenzie BS, Berzins SP, Smyth MJ, Godfrey DI. Diverse cytokine production by NKT cell subsets and identification of an IL-17-producing CD4-NK1.1- NKT cell population. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:11287–11292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801631105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Motsinger A, Azimzadeh A, Stanic AK, Johnson RP, Van Kaer L, Joyce S, Unutmaz D. Identification and simian immunodeficiency virus infection of CD1d-restricted macaque natural killer T cells. J Virol. 2003;77:8153–8158. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.14.8153-8158.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Motsinger A, Haas DW, Stanic AK, Van Kaer L, Joyce S, Unutmaz D. CD1d-restricted human natural killer T cells are highly susceptible to human immunodeficiency virus 1 infection. J Exp Med. 2002;195:869–879. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Rout N, Else JG, Yue S, Connole M, Exley MA, Kaur A. Heterogeneity in phenotype and function of CD8+ and CD4/CD8 double-negative Natural Killer T cell subsets in sooty mangabeys. J Med Primatol. 2010;39:224–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2010.00431.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Rout N, Else JG, Yue S, Connole M, Exley MA, Kaur A. Paucity of CD4+ natural killer T (NKT) lymphocytes in sooty mangabeys is associated with lack of NKT cell depletion after SIV infection. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9787. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Campillo-Gimenez L, Cumont MC, Fay M, Kared H, Monceaux V, Diop O, Muller-Trutwin M, Hurtrel B, Levy Y, Zaunders J, Dy M, Leite-de-Moraes MC, Elbim C, Estaquier J. AIDS progression is associated with the emergence of IL-17-producing cells early after simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J Immunol. 2010;184:984–992. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Brenchley JM, Schacker TW, Ruff LE, Price DA, Taylor JH, Beilman GJ, Nguyen PL, Khoruts A, Larson M, Haase AT, Douek DC. CD4+ T cell depletion during all stages of HIV disease occurs predominantly in the gastrointestinal tract. J Exp Med. 2004;200:749–759. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Groh V, Steinle A, Bauer S, Spies T. Recognition of stress-induced MHC molecules by intestinal epithelial gammadelta T cells. Science. 1998;279:1737–1740. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5357.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Autran B, Triebel F, Katlama C, Rozenbaum W, Hercend T, Debre P. T cell receptor gamma/delta+ lymphocyte subsets during HIV infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 1989;75:206–210. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Kosub DA, Durudas A, Lehrman G, Milush JM, Cano CA, Jain MK, Sodora DL. Gamma/Delta T cell mRNA levels decrease at mucosal sites and increase at lymphoid sites following an oral SIV infection of macaques. Curr HIV Res. 2008;6:520–530. doi: 10.2174/157016208786501490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Kosub DA, Lehrman G, Milush JM, Zhou D, Chacko E, Leone A, Gordon S, Silvestri G, Else JG, Keiser P, Jain MK, Sodora DL. Gamma/Delta T-cell functional responses differ after pathogenic human immunodeficiency virus and nonpathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus infections. J Virol. 2008;82:1155–1165. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01275-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Antonelli LR, Dutra WO, Oliveira RR, Torres KC, Guimaraes LH, Bacellar O, Gollob KJ. Disparate immunoregulatory potentials for double-negative (CD4− CD8−) alpha beta and gamma delta T cells from human patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis. Infect Immun. 2006;74:6317–6323. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00890-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Ma Y, He KM, Garcia B, Min W, Jevnikar A, Zhang ZX. Adoptive transfer of double negative T regulatory cells induces B-cell death in vivo and alters rejection pattern of rat-to-mouse heart transplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2008;15:56–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2008.00444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Malleret B, Maneglier B, Karlsson I, Lebon P, Nascimbeni M, Perie L, Brochard P, Delache B, Calvo J, Andrieu T, Spreux-Varoquaux O, Hosmalin A, Le Grand R, Vaslin B. Primary infection with simian immunodeficiency virus: plasmacytoid dendritic cell homing to lymph nodes, type I interferon, and immune suppression. Blood. 2008;112:4598–4608. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-162651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Diop OM, Ploquin MJ, Mortara L, Faye A, Jacquelin B, Kunkel D, Lebon P, Butor C, Hosmalin A, Barre-Sinoussi F, Muller-Trutwin MC. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell dynamics and alpha interferon production during Simian immunodeficiency virus infection with a nonpathogenic outcome. J Virol. 2008;82:5145–5152. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02433-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Campillo-Gimenez L, Laforge M, Fay M, Brussel A, Cumont MC, Monceaux V, Diop O, Levy Y, Hurtrel B, Zaunders J, Corbeil J, Elbim C, Estaquier J. Nonpathogenesis of simian immunodeficiency virus infection is associated with reduced inflammation and recruitment of plasmacytoid dendritic cells to lymph nodes, not to lack of an interferon type I response, during the acute phase. J Virol. 2010;84:1838–1846. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01496-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Mandl JN, Barry AP, Vanderford TH, Kozyr N, Chavan R, Klucking S, Barrat FJ, Coffman RL, Staprans SI, Feinberg MB. Divergent TLR7 and TLR9 signaling and type I interferon production distinguish pathogenic and nonpathogenic AIDS virus infections. Nat Med. 2008;14:1077–1087. doi: 10.1038/nm.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Reeves RK, Gillis J, Wong FE, Yu Y, Connole M, Johnson RP. CD16-natural killer cells: enrichment in mucosal and secondary lymphoid tissues and altered function during chronic SIV infection. Blood. 2010;115:4439–4446. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-265595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Reeves RK, Evans TI, Gillis J, Johnson RP. SIV infection induces an expansion of {alpha}4{beta}7+ and cytotoxic CD56+ NK cells. J Virol. 2010;84:8959–8963. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01126-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Pereira LE, Ansari AA. A case for innate immune effector mechanisms as contributors to disease resistance in SIV-infected sooty mangabeys. Curr HIV Res. 2009;7:12–22. doi: 10.2174/157016209787048465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Elbim C, Monceaux V, Francois S, Hurtrel B, Gougerot-Pocidalo MA, Estaquier J. Increased neutrophil apoptosis in chronically SIV-infected macaques. Retrovirology. 2009;6:29. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-6-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Mortara L, Ploquin MJ, Faye A, Scott-Algara D, Vaslin B, Butor C, Hosmalin A, Barre-Sinoussi F, Diop OM, Muller-Trutwin MC. Phenotype and function of myeloid dendritic cells derived from African green monkey blood monocytes. J Immunol Methods. 2006;308:138–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Grassi F, Hosmalin A, McIlroy D, Calvez V, Debre P, Autran B. Depletion in blood CD11c-positive dendritic cells from HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 1999;13:759–766. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199905070-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Pacanowski J, Kahi S, Baillet M, Lebon P, Deveau C, Goujard C, Meyer L, Oksenhendler E, Sinet M, Hosmalin A. Reduced blood CD123+ (lymphoid) and CD11c+ (myeloid) dendritic cell numbers in primary HIV-1 infection. Blood. 2001;98:3016–3021. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.10.3016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Brown KN, Trichel A, Barratt-Boyes SM. Parallel loss of myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells from blood and lymphoid tissue in simian AIDS. J Immunol. 2007;178:6958–6967. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Kedzierska K, Crowe SM. The role of monocytes and macrophages in the pathogenesis of HIV-1 infection. Curr Med Chem. 2002;9:1893–1903. doi: 10.2174/0929867023368935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Estcourt C, Rousseau Y, Sadeghi HM, Thieblemont N, Carreno MP, Weiss L, Haeffner-Cavaillon N. Flow-cytometric assessment of in vivo cytokine-producing monocytes in HIV-infected patients. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;83:60–67. doi: 10.1006/clin.1996.4323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Esser R, Glienke W, von Briesen H, Rubsamen-Waigmann H, Andreesen R. Differential regulation of proinflammatory and hematopoietic cytokines in human macrophages after infection with human immunodeficiency virus. Blood. 1996;88:3474–3481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Mureith MW, Chang JJ, Lifson JD, Ndung’u T, Altfeld M. Exposure to HIV-1-encoded Toll-like receptor 8 ligands enhances monocyte response to microbial encoded Toll-like receptor 2/4 ligands. AIDS. 2010;24:1841–1848. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833ad89a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Brabers NA, Nottet HS. Role of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-alpha and IL-1beta in HIV-associated dementia. Eur J Clin Invest. 2006;36:447–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2006.01657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Muthukumar A, Zhou D, Paiardini M, Barry AP, Cole KS, McClure HM, Staprans SI, Silvestri G, Sodora DL. Timely triggering of homeostatic mechanisms involved in the regulation of T-cell levels in SIVsm-infected sooty mangabeys. Blood. 2005;106:3839–3845. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]