Abstract

Determining the referent of a novel name is a critical task for young language learners. The majority of studies on children’s referent selection focus on manipulating the sources of information (linguistic, contextual and pragmatic) that children can use to solve the referent mapping problem. Here, we take a step back and explore how children’s endogenous biases towards novelty and their own familiarity with novel objects influence their performance in such a task. We familiarized 2-year-old children with previously novel objects. Then, on novel name referent selection trials children were asked to select the referent from three novel objects: two previously seen and one completely novel object. Children demonstrated a clear bias to select the most novel object. A second experiment controls for pragmatic responding and replicates this finding. We conclude, therefore, that children’s referent selection is biased by previous exposure and children’s endogenous bias to novelty.

Keywords: word learning, fast mapping, novelty, language acquisition

The problem of learning words is a problem of ambiguity wrapped in uncertainty and shrouded in vagueness. On the auditory side, the acoustic cues to individual phonemes are inherently context dependent, and at the level of words, there are few cues that allow the listener to unambiguously segment a word. On the visual and conceptual side, parsing objects from the visual scene is extraordinarily difficult, and how the properties of those objects to are mapped to concepts and categories is still not understood. Children of course, must solve both problems without substantial top-down knowledge, and without always knowing all the relevant features of the input.

However, learning a word requires children to face a third level of ambiguity: they must learn which of those highly ambiguous auditory categories maps to which of those highly uncertain visual categories. This mapping problem can be seen quite vividly the first time a child is presented with a novel word and several possible referents. In such situations, there are an infinite number of interpretations for the novel word that might be considered (cf. Quine, 1960)—each of the referents, their properties, actions that the speaker may take on them (or has taken) and so forth. Each is instantiated as a possible link between the auditory word-form and concept, and thus, even in this relatively constrained task, an enormous number of potential mappings must be considered. The rapid pace at which young children typically acquire a vocabulary, however, points to their skill at solving this problem.

Historically, research aimed at examining this skill has focused on the types of information children use to determine the correct referent of a novel word. In a typical study, the child is presented with a novel word, some possible referents for that word, and various cues such as eye-gaze, gestures, or syntactic frames that suggest the intended meaning. Such studies have been incredibly productive and reveal, among other things, the contributions of linguistic, conceptual and social/pragmatic cues in children’s determination of novel word meaning (see e.g., Baldwin, 1991; Booth & Waxman, 2003; Heibeck & Markman, 1987; Jaswal & Markman, 2001; Moore, Angelopoulos, & Bennett, 1999; Tomasello & Akhtar, 1995). The main focus of this kind of work, however, is how children use the linguistic or pragmatic cues presented by the experimenter in conjunction with a novel word and the available objects to determine the referent. As such, this approach treats early word learning as an inference problem and the cues presented in the task as sources of information that can be used to constrain the problem-space.

Studies based on this approach attempt to minimize the influence of individual children’s endogenous biases on their in-the-moment performance by using completely novel objects and/or words, focusing on mean performance across groups of children, and controlling the experiment such that only one or two sources of information are available. Importantly, however, children’s endogenous biases could create an uneven playing field on which other sources of information must compete. As an example, consider a case in which social cues such as eye-gaze direct the child to one object, but the child is endogenously biased to consider another object. If a novel word were presented, which object would win and be mapped to the novel word? The one the child was biased toward? Or the one the other speaker was indicating with eye-gaze? Evidence from Hirsh-Pasek, Golinkoff and Hollich (2000) suggests that there is a developmental progression in word learning tasks that pit object salience against other cues to referents. Likewise, there are similar changes in the role of object salience in directing eye gaze during the second year (see, Moore, 2008 for a review and Corkum & Moore, 1998; Deák, Flom, & Pick, 2000).

Clearly, any complete account of children’s behavior in even the simplest of word learning tasks needs to take children’s biases, goals and intentions into account. Biases may not always align with the task and/or empirical questions posed by the experimenter, and it is crucial to be aware of such biases so that they can be accounted for. But, more importantly, such biases may compete with information-based processes to determine how the child treats novel words and novel objects in the real world as well. The studies presented here take a first step in this direction by examining an endogenous bias that is quite likely to influence children’s performance in referent selection tasks and can be manipulated in the laboratory—children’s attraction to novel objects.

There is considerable evidence from early infancy that novelty plays a role in driving attention, eye-movements and other behaviors, and that this may change with development (e.g., Hunter & Ames, 1988). For example, from two months of age infants’ decrease their amount of looking to familiar stimuli across successive trials, as the stimuli become more familiar (Fantz, 1964), from four months infants discriminate between a previously seen targets and previously unseen foils from the same category after less than 15 seconds of exposure (e.g., Quinn, Eimas, & Rosenkrantz, 1993), and from seven months infants reach more for novel objects than familiar objects (Shinskey & Munakata, 2005). Thus, there is fairly robust evidence for a basic novelty bias in how infants approach stimuli.

It is likely that children’s relative familiarity with objects and words would also bias their performance in the referent selection tasks that occur every day. For example, in the 17,000 words that each child hears on a given day (Hart & Risley, 1995), there are likely to be many word forms that may be partly or entirely familiar, but for which the child does not know the meaning. Similarly, a child who knows 50, 100 or even 200 words is likely surrounded every day by thousands of objects for which she has not yet learned the names, but that she has seen several times before. Thus, while every word and object is novel to a child at one point in time, outside of laboratory experiments, the proportion of situations in which children are presented with words and objects with which they have no familiarity whatsoever is likely to be quite small.

Previous research has made it clear that children can use the novelty of potential referents as a cue to word meaning. For example, a child presented with an object from a category for which she knows the name, such as a cup, and an object from a novel, nameless category will map the novel name to the novel object (Halberda, 2006). Or, if only the cup is present, the child will infer the novel name refers to an object part such as the handle (Hansen & Markman, 2009). Children can also use relative novelty in a context to determine if a word denotes an object or action (Tomasello & Akhtar, 1995). In highly ambiguous cases, in which an adult does not use a name but requests “it,” 12–14-month-old infants will choose the object they have never played with before, that is, the object that is most novel to themselves, but by 18–20 months infants are just as likely to choose the object that is most novel to the adult (MacPherson & Moore, 2010). Similarly, after an adult and infant have played with an object together, 14–20-month-old infants will map the ambiguous pronoun “it” to something previously played with, rather than something novel (Ganea & Saylor, 2007). Thus, novelty in context contributes to children’s ability to handle referential ambiguity. However, children are not simply novelty-seekers—in these experiments, novelty contributes as a source of information along with other pragmatic, lexical, and memory-based processes.

Other studies suggest that children take novelty relative to a speaker into account in referent selection. For example, children take adults’ excitement as an indication of what is most novel and is therefore more likely to be the referent of a novel word (Tomasello & Haberl, 2003). Likewise, in cases where they do not know names for any of the stimuli but the novel object is familiar to the experimenter, children map novel names to novel parts (Grassmann, Stracke, & Tomasello, in press; Moll, Carpenter, & Tomasello, 2007). Along this line, previous research by Akhtar and colleagues (Akhtar, Carpenter, & Tomasello, 1996; Diesendruck, Markson, Akhtar, & Reudor, 2004) suggests that children use the relative novelty of an object to a speaker when mapping a novel name to a collection of nameless objects (see also, Moll, et al., 2007; Moll & Tomasello, 2007). On the basis of such data, these authors and others (see e.g., Birch & Bloom, 2002) have argued that novelty acts as social pragmatic cue in naming contexts.

Both lines of research argue that novelty to either the speaker or the child participates as a source of information in complex inference processes—children become increasingly sensitive to what other people know and novelty can serve as a component of that sensitivity. But can novelty play a more basic role? A number of researchers have argued that endogenous attentional mechanisms, removed from communicative pragmatics, can bias children’s interpretations of novel words. For example, Samuelson and Smith (1998) found that children readily map novel names to the most salient object in a context; suggesting that simple endogenous mechanisms could shape a lexical response quite independently of the demands of word learning. In previous studies, because the use of novelty as a cue to word meaning emphasized the inferential component of referent selection, the literature neglected the contribution of children’s own endogenous biases toward or away from novel objects. Samuelson and Smith argued that such salience may even be a proxy or heuristic for other types of inference—that is, social/pragmatic cues may work, at least early in development, by biasing attention. However, whether such endogenous biases are equivalent to more inferential processes, or compete against them to shape the response, it is clear that we must understand them in order to understand word learning in its natural environment. Samuelson and Smith’s (1998) data offer a good start and a hint that such biases may exist, however, their study focused on short-term attentional factors—the increased salience of an object based on its novelty in a context—not longer-developing factors like the familiarity of an object to a child. This the focus of the work presented here.

To better understand how children’s relative familiarity with objects, and their endogenous biases towards novelty, influence their interpretation of novel names, we need a systematic investigation of a novel word learning situation in which no information is presented to bias referent selection. A particularly informative case would be one in which children are confronted with a novel word and multiple novel, nameless objects. Lacking any additional information, children should be equally likely to select any of the possible referents. But what if the objects varied in how familiar they were to the child? All of the objects are nameless, so again, each object should be equally likely to be selected as the referent of the novel name. However, the extent to which children are biased to select objects based on their novelty/familiarity would reveal something about the internally driven biases that shape this behavior.

To this end, we tested the effects of children’s familiarity with objects on how they map novel names to novel objects. Specifically, we presented 2-year-old children with a referent selection task in which the only difference between the possible referents was the child’s own previous experience with the objects. Thus, in the current study we ask if children’s own familiarity with the novel, nameless objects changes how they perform on a referent selection task. Importantly, when the completely novel object is introduced in this study there is no change in location (cf., Diesendruck, et al., 2004), no change in the experimenter’s excitement (cf., Akhtar, et al., 1996), no special activity enacted only on it (cf., Samuelson & Smith, 1998) and no information provided about whether it is familiar or novel to the experimenter (cf., Birch & Bloom, 2002). That is, we do not highlight novelty in any way and do not use novelty as a cue to a “correct” answer. If children still map the novel name onto the most novel object, this will suggest that children’s endogenous biases to novelty play an important role in young children’s referent selections.

Experiment 1

Method

Participants

Twelve 24-month-old monolingual, English-speaking children (M = 24m 20d, SD = 14.11d, range = 24m 7d – 25m 20d, 5 girls, 7 boys) participated. Data from one additional child were excluded from analyses due to experimenter error. Parents were reimbursed for parking and children received a small gift (e.g., storybook) for participating.

Stimuli

Sixteen known and 16 unknown objects served as potential referents (see Figure 1). Before the experiment began, the experimenter showed the parent color photographs of the known objects and asked if the child was familiar with all the words and objects. If the child knew a different name for an object (e.g., “kitty” v. “cat”) that name was used during the experiment. The parent was also shown color photographs of the novel objects and asked if the child could name any of them. Additional stimuli were available for substitutions if a child was familiar with a novel object or unfamiliar with a known object, however, no such substitutions were needed. All objects were similar in size (5cm × 8cm × 10cm). Eight distinct CVC nonwords were used to name the novel objects: cheem, dite, dupe, fode, foo, pabe, roke, yok. These words were chosen because they adhere to English phonological rules and have been used successfully in previous studies (see, Horst & Samuelson, 2008; Wilkinson & Mazzitelli, 2003). The objects were presented on a white, wooden tray that was divided into three sections.

Figure 1.

The stimuli used in the experiments. Panel A depicts the 16 known objects. Panels B and C depict the 8 familiarized novel and 8 super novel objects, respectively.

Design and Procedure

During the experiment, children were seated across a white table from the experimenter in a booster seat next to their parents or on their parents’ laps. Parents were instructed to avoid interacting with their children but to encourage their children to respond if necessary. Most children did not need parental encouragement after the warm-up trials.

Each session began with a familiarization phase in which the child played with half of the novel objects—these eight objects became the familiarized novel objects, the remaining eight objects would be completely novel at test, or “supernovel.” An experimenter was present during the familiarization only to ensure that the child interacted with all the objects and that the parent did not name them. First, the experimenter placed four novel objects together on the table without providing any names. Children were allowed to explore the objects anyway they wanted to for approximately one minute. Then, the experimenter removed those objects and placed four more novel objects on the table for another minute.

Similar to sequential touching tasks (e.g., Ellis & Oakes, 2006), the experimenter allowed the child to play with the objects alone with minimal interference—acting only to ensure that the child touched each object at least once. That is, if the child was not attending to the objects, had not yet examined a particular object, or explored a single object exclusively, the experimenter gently encouraged the child to engage with the objects by using neutral language, e.g., “look at this one” or “what can you do with this?” (for a similar method see, Jaswal, 2010). Otherwise, the experimenter did not engage with the child. Children generally enjoyed playing with these novel objects, thus, the social interaction between the experimenter and child was minimal throughout the familiarization phase.

The experimenter removed all of the objects from the table at the end of the familiarization phase. The test phase immediately followed the familiarization phase. First the experimenter presented three warm-up trials with the same three known objects on each trial (e.g., dog, cup, shoe). These trials were included to introduce children to the forced-choice task and to provide them with practice in choosing one object on each trial from any location (left, middle, right). On each warm-up trial, the experimenter set the tray of objects on the table and silently counted for three seconds. This gave the child an opportunity to look at the objects (see, Horst & Samuelson, 2008). The experimenter then asked for the target object (e.g., “can you get the dog?”) before sliding the tray forward. Children were prompted up to four additional times if needed. Children were praised heavily for correct responses and corrected if necessary. The same objects were presented on each warm-up trial, but positions of the objects on the tray were pseudo-randomized across trials. Children were asked for a different object in a different position (left, middle, right) on each trial. The warm-up stimuli were not used again during the experiment.

The referent selection trials immediately followed the warm-up trials and continued in the same manner except that children were neither praised nor corrected after their selections. The experimenter simply took the object back and said “ok” or “thank you.” On known name referent selection trials the child was presented with three known objects (e.g., banana, car, horse) and a known name (e.g., “can you get the horse?”). Thus, these trials were the same as the warm-up trials except that children were neither praised nor corrected. These trials were included as a control to check that the child stayed on task. On novel name referent selection trials the child was presented with three novel objects—two familiarized novels (e.g., kaleidoscope, bird-toy) and one completely new novel object (e.g., massager)—and a novel name (e.g., “can you get the fode?”). Regardless of trial type (known name, novel name) or which object the child selected, the experimenter remained neutral, but used a positive tone-of-voice to keep the child engaged in the task (see also, Jaswal, 2010).

One known name trial occurred after every two novel name trials (i.e., Trials 3, 6, 9, 12), for a total of four known and eight novel name referent selection trials. Across novel name trials children saw each familiarized novel object twice and each completely new novel object once. Specifically, children first saw the novel objects from the first minute of the familiarization phase during trials 1 and 2. For example, a child might see the kaleidoscope and birdtoy with the massager. Similarly, children saw the novel objects from the second minute of the familiarization phase during trials 4 and 5. For example, a child might see the slinky and Jacob’s ladder with the top. On the remaining novel name referent selection trials, children saw one familiarized object from the first minute and one novel object from the second minute of the familiarization phase. For example, a child might see the kaleidoscope and slinky with the metal sphere. Thus, trials were presented in blocks: all familiarized novel objects were seen for the first time as test objects during Block 1 (the first four novel name referent selection trials) and were seen for the second time during Block 2 (the last four novel name trials). A different “supernovel” object was presented on each trial. Sets, object locations and novel trial order were counterbalanced across children.

Coding

The experimenter recorded children’s responses onto a datasheet during the session. Across both experiments, children picked up or touched a single object on 95% of the known name trials and 92% of the novel name trials. Children pointed to a single object on the other trials. If a child failed to make a clear response this was coded as a “non-response.” In Experiment 1 non-responses occurred once on a known name trial for two children and once on a novel name trial for two children. All of the children in Experiment 2 made clear responses on every trial. A naïve coder coded 25% of the sessions from each experiment offline from DVD. Inter-coder reliability was 100%. Children’s proportion of known name, supernovel or foil choices on the referent selection trials were calculated as the number of choices to a given object type (e.g., supernovel) out of the number of total responses on known or novel name trials, respectively. For example, if a child chose the supernovel object six times, a familiarized novel once and failed to respond once on the novel name trials, the proportion of supernovel choices would be .86 (see also, Horst & Samuelson, 2008).

Results

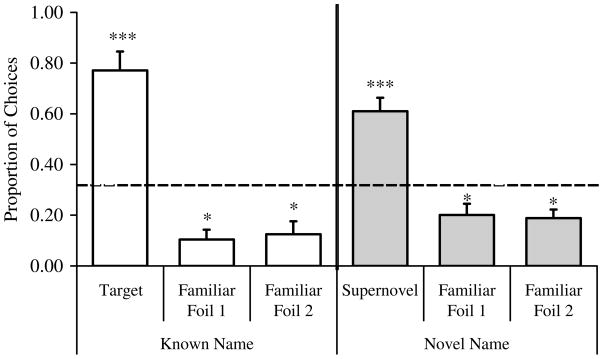

Results are depicted in Figure 2. On known name trials, children chose the target object at a rate of 77%. As can be clearly seen, children chose the target object significantly more than expected by chance (.33), t(11) = 6.12, p < .0001, d = 3.69 and chose both foils significantly less than chance, t(11) = −6.07, p < .0001, d = −1.75, and t(11) = −4.21, p < .01, d = −1.22, respectively (throughout this paper, all ps are two-tailed, and each analysis against chance uses Bonferroni’s correction of α = .05/3 = .02).

Figure 2.

Data from Experiment 1. White bars indicate responses on known name trials, dark bars indicate responses on novel name trials. Dotted line represents chance (.33). Error bars indicate one standard error. *** p < .0001, * p < .05.

On novel name trials, children demonstrated a clear bias to the “supernovel” object, selecting it on 61% of the trials. This was seen at the individual level as well as 11 of the 12 children selected the supernovel object at greater than chance levels (3 or more trials). Children’s proportion of supernovel responses was significantly greater than chance (.33), t(11) = 5.56, p < .0001, d = 3.31, and chose both familiarized novel objects significantly less than expected by chance, M = 20%, t(11) = −2.98, p < .05, d = −.88 and M = 19%, t(11) = −4.25, p < .01, d = −1.26 respectively1. Pre-planned, paired t-tests confirmed that children chose the completely new novel object significantly more than either of the familiarized novel objects, t(11) = 4.65, p < .001, d = 2.47 and t(11) = 5.67, p < .001, d = 2.81, respectively (using Bonferroni’s correction of .025). .

This would appear to support our hypothesis that an endogenous novelty bias may be present in referent selection tasks, and may play a role in word learning. However, to be sure that such a bias did not arise from other factors, we conducted four follow-up analyses.

Object Salience

First, we were concerned that children’s strong preference for the supernovel objects could be due to how interesting the objects were, that is an a priori preference for the supernovel objects over the familiarized novel objects. To assess children’s preferences for the supernovel stimulus set, a separate group of 13 24-month-old children (M = 24m 25d, SD = 7.76d, range = 24m 11d – 25m 6d, 6 girls, 7 boys) were presented with preference trials. On each trial, the child was presented with two novel objects: one that had been used as a familiarized novel object (Figure 1, Panel B) and one that had been used as a supernovel object (Figure 1, Panel C) in Experiment 1. The experimenter placed the two objects on a white, wooden tray divided in two even sections and asked: “can you get the one you like the best?” and then slid the tray toward the child. Across children, each item was paired with each other item (i.e., massager/kaleidoscope) approximately equally often. Trial order and locations (left, right) were also counterbalanced across participants. Children’s responses were coded offline by a naïve coder, and again inter-coder reliability was high, M =97.14, SD = 7.56. Children chose the familiarized novel objects on 59% (SD = 15%) of trials and the supernovel objects on 41% (SD = 15%) of trials. A one-sample t-test on children’s proportion of supernovel choices revealed that children preferred the supernovel objects significantly less than expected by chance (.50), t(12) = −2.23, p < .05, two-tailed, d = .63. That is, children significantly preferred the familiarized novel objects. This suggests, then, that children in Experiment 1 had to overcome their a priori preferences for the familiarized novel objects to choose the supernovel objects. This is consistent with previous research that suggests that by 18–20 months children are able to overcome their own egocentric preferences to respond to adult requests (MacPherson & Moore, 2010; Repacholi & Gopnik, 1997). In this light, children’s strong bias for the supernovel object is even more striking.

Block Effects

Our second follow-up analysis examined the possibility that the child interpreted the experimenter’s response at the end of the trial (“ok” or “thank you”) as feedback (either reinforcing familiarized novel or supernovel object choices). If this were the case, we might see a change in supernovel choices during Block 2, mostly likely an enhancement of whatever effect was observed in Block 1. Thus, we also examined children’s choices on the novel name referent selection trials as a function of Block (first, second). We found no difference in the proportion of supernovel choices during Block 1 (M = .62, SD = .16) or Block 2 (M = .60, SD = .25), t(11) = .31, ns, d = .19. Thus, children showed the same strong bias for the supernovel object, regardless of whether the familiarized novel object had (Block 2) or had not (Block 1) already been seen on a referent selection trial.

Familiarization Effects

Our third follow-up analysis examined whether something about how the experimenter and child had interacted with objects during the familiarization phase could account for children’s strong supernovel bias. A naïve coder counted the number of times the experimenter directed children’s attention to each object during the familiarization phase. We then compared the number of times the experimenter directed children’s attention to a familiarized novel object that the child proceeded to choose during the referent selection trials (M = 1.79, SD = 1.21) versus a familiarized novel object the child did not choose (M = 1.80, SD = .66) and found no difference, t(10) = .58, ns, d = .33. This suggests, then, the experimenter’s behavior during the familiarization phase did not differentially influence children’s responses during the referent selection trials.

Experimenter Influence

Finally, it was possible that the experimenter could have unconsciously influenced children’s choices during the referent selection trials. When the experimenter made the request for an object during the referent selection trials she looked directly into the child’s eyes and not at any of the objects. Nevertheless, to ensure that no other subtle cues by the experimenter could have directed the child to the supernovel object, we asked a group of naïve adults to guess which object the experimenter was requesting on each novel object trial for each participant. Twelve adults (18–39-years-old) watched all of the sessions from DVD and wrote down the location (left, middle, right) of the object they thought the experimenter was requesting for each trial. Each adult watched a single child’s session. Overall, adults picked the supernovel object as the referent on 29% of the trials (SD = 17%). A one-sample t-test on adults’ proportion of supernovel guesses revealed that adults suspected the supernovel objects as the referent at chance levels (.33), t(11) = −.78, ns, two-tailed, d = .22. This suggests, then, that the experimenter was not providing any additional cues to the referent of the novel names.

Discussion

Clearly, children behaved systematically in this referent selection task, even though there was no correct answer. Specifically, children were biased to choose the most novel object as a function of the objects’ familiarity. Our follow-up analyses also suggest that children’s responses were not driven by the differences in the experimenter’s responding over the course of the referent selection trials or during novel name referent selection trials. Additional testing revealed that 2-year-old children actually preferred the familiarized novel objects over the supernovel objects.

Nevertheless, one alternative explanation for our results might be that the prior familiarization in the presence of an experimenter served to increase the salience of some of the objects. We think this is unlikely for two reasons. First, the experimenters refrained from directing attention to the objects as much as possible, and our analyses show no differences in later referent selection based on the experimenter’s prompts to look at any of the objects. Second, prior studies have found that adult attention to objects increases their salience (Baldwin & Markman, 1993) whereas here we found the children were actually biased away from the familiarized objects and toward the supernovel ones.

It is possible, however, that children’s responses were influenced by pragmatic factors. For example, children may have chosen the unfamiliar novel objects because they had no social history or previous shared experience with the experimenter and those objects. Given that children are sensitive to speakers’ knowledge and presence during naming events (e.g., Diesendruck, et al., 2004; Jaswal & Markman, 2007; Sabbagh & Baldwin, 2001), it is possible that children expect adults to name objects they know, and fail to name objects for which they do not already know the name. That is, children may have chosen the unfamiliar novel object simply because the experimenter had failed to name the other objects earlier, implying that the experimenter did not know these names (otherwise she would have used them).

Experiment 2 was designed to rule out this explanation. Specifically, to ensure that children’s behavior during the referent selection trials was not due to earlier social interaction with the experimenter, we did not allow the child to have earlier social interaction with the experimenter who administered the referent selection trials. We did this by replicating Experiment 1 with two different experimenters. Experiment 2 was identical to Experiment 1 except that one experimenter administered the familiarization phase and a different experimenter administered the warm-up and referent selection trials. If children’s behavior in Experiment 1 is due to pragmatic understanding of what adults are likely to name, then children should show no biases on the referent selection trials of Experiment 2 with a naïve experimenter. If, however, children’s behavior in Experiment 1 is due to the familiarity of the novel objects, then children should demonstrate the same “supernovel” bias in Experiment 2 despite changing experimenters.

Experiment 2

Method

Participants

Twelve 24-month-old monolingual, English-speaking children (M = 24m 26d, SD = 19.2, range = 23m 24d – 26m 4d, 6 girls, 6 boys) participated. None of the children had participated in Experiment 1. Data from two additional children were excluded from the analyses due to parental interference (n = 1), which included naming the stimuli and picking objects for the child, and fussiness (n = 1).

Design and Procedure

All aspects of the experiment were identical to Experiment 1 except that one experimenter presented objects during the familiarization phase, then announced “Now [name] is going to come and play with you!” Then, a second experimenter who was not in the room during the familiarization phase came into the room as the first experimenter left. The second experimenter presented all of the referent selection trials.

Results and Discussion

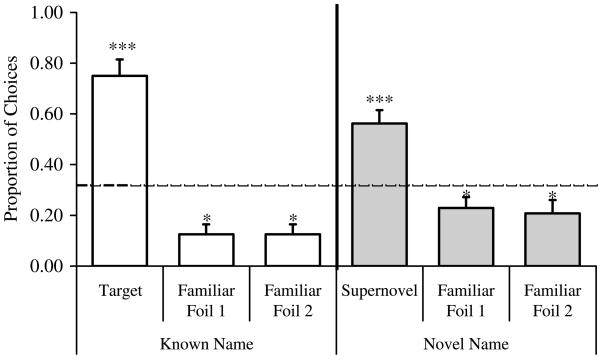

Results are depicted in Figure 3. As in Experiment 1, on known name trials, children chose the target object at a rate of 75%. As can be clearly seen, children chose the target object significantly more than expected by chance (.33), t(11) = 6.82, p < .0001, d = 1.97 and chose both foils significantly less than chance, both t(11) = −5.44, p < .0001, both d = −1.57.

Figure 3.

Data from Experiment 2. White bars indicate responses on known name trials, dark bars indicate responses on novel name trials. Dotted line represents chance (.33). Error bars indicate one standard error. *** p < .0001, * p ≤ .05.

Also, as in Experiment 1, on novel name trials, children demonstrated a clear bias to the “supernovel” object, selecting it on 56% of trials. This was again seen at the individual level as 11 of the 12 children selected the supernovel object at greater than chance levels (3 or more trials). Children’s proportion of supernovel responses was greater than chance (.33), t(11) = 4.71, p < .0001, d = 1.35, and chose both familiarized novel objects marginally significantly less than expected by chance, M = 23%, t(11) = −2.45, p = .03, d = .72 and M = 21%, t(11) = −2.40, p = .03, d = .71 respectively, using Bonferroni’s correction of .02). Again, Pre-planned paired t-tests confirmed that children chose the completely new novel object significantly more than either of the familiarized novel objects, t(11) = 4.42, p < .001, d = 2.12 and t(11) = 3.89, p < .01, d = 2.06, respectively (using Bonferroni’s correction of .025).

To better understand children’s novelty bias and to be sure that such a bias did not arise from other factors, we conducted the same follow-up analyses as in Experiment 1.

Object Salience

The same stimuli served as familiarized novel objects and supernovel objects as in Experiment 1. Recall, we tested an additional group of children after Experiment 1 and they significantly preferred the familiarized novel objects to the supernovel objects. Again, this suggests that children in the current experiment had to overcome their a priori preferences and that children’s strong bias for the supernovel objects is even more remarkable.

Block Effects

Next, we examined children’s choices on the novel name referent selection trials as a function of block (first, second). The same pattern of results as in Experiment 1 was found: a strong bias for the supernovel object, regardless of whether the familiarized novel object had (Block 2) or had not (Block 1) already been seen on a referent selection trial. Again there was no difference in the proportion of supernovel choices during Block 1 (M = .56, SD = .24) or Block 2 (M = .56, SD = .26), t(11) = 1.00, ns, d = .60.

Familiarization Effects

We also compared the number of times during the familiarization phase the first experimenter directed children’s attention to a familiarized novel object that the child proceeded to choose during the referent selection trials (M = 1.41, SD = .90) versus a familiarized novel object the child did not choose (M = 1.28, SD = .49) and found no difference, t(11) = .55, ns, d = .33. This suggests, then, that the experimenter’s behavior during the familiarization phase did not differentially influence children’s responses during the referent selection trials with the other experimenter.

Experimenter Influence

Finally, it was possible that the second experimenter could have unconsciously influenced children’s choices during the referent selection trials, even though she again looked directly into the child’s eyes an not at any of the objects on these trials. Thus, we asked a group of naïve adults to guess which object the experimenter was requesting on each novel object trial for each participant. Twelve adults (18–32-years-old) watched all of the sessions from DVD and wrote down the location (left, middle, right) of the object they thought the experimenter was requesting for each trial. Each adult watched a single child’s session. Overall, adults picked the supernovel object as the referent 39% of the time (SD = 16%). A one-sample t-test on adults’ proportion of supernovel guesses revealed that adults suspected the supernovel objects as the referent at chance levels (.33), t(11) = 1.24, ns, two-tailed, d = .36. This suggests, then, that the experimenter was not providing any additional cues to the referent of the novel names.

These results clearly replicate the findings from Experiment 1 and demonstrate that children’s knowledge of what was most familiar to the speaker or highlighted in the earlier social interaction of that experiment cannot account for their highly systematic behavior. Therefore, children’s behavior in these experiments is very likely the result of differences in familiarity of the novel objects and their own endogenous biases towards novelty.

General Discussion

Across two experiments we familiarized children with previously novel objects and then presented them with referent selection trials with a novel name, two now-familiar novel objects and a completely new “supernovel” object. Children behaved systematically in this task: they mapped novel names to the object that was most novel to themselves. This was the case even if all the objects were equally novel to the adult speaker at the time of referent selection (Experiment 2). This study differed from the vast majority of studies in the extant literature, because although children were asked to determine the referent of a novel name, there was no “correct” answer to the mapping problem (cf. Akhtar, Jipson, & Callanan, 2001; Horst & Samuelson, 2008). Yet, children behaved in a highly systematic manner that appears to derive from an endogenous bias to novelty. The roots of this bias may even lie in the well-known visual novelty preferences that begin to develop in early infancy (Hunter & Ames, 1988).

The current findings demonstrate that behavior in word learning tasks can be driven by non-linguistic knowledge and does not have to depend on linguistic or pragmatic information. Young children map novel names to objects previously singled out by an adult and are sensitive to objects being singled out via ostensive naming (Akhtar, et al., 1996), salient activities (Samuelson & Smith, 1998) or speaker’s intention to refer to them (Tomasello & Akhtar, 1995). However, most previous experiments (e.g., Akhtar, et al., 1996; Diesendruck, et al., 2004) manipulate the novelty of the objects to the speaker. Here, however, we manipulated the novelty of the objects to the child. If children’s behavior was driven by novelty to the speaker, they would have been equally likely to choose any of the objects, particularly in Experiment 2 in which the speaker was unfamiliar with any of the objects. The systematicity of their preference for the supernovel objects, however, suggests that children were sensitive to their own familiarity or novelty with the objects and that their behavior was guided by attentional mechanisms (for a similar explanation of these findings, see Diesendruck et al., 2004).

Note that we are not denying that children are capable of pragmatic inference nor that social interaction plays a role in language acquisition. The extant word learning literature is filled with examples in which young children use pragmatic cues in various ambiguous situations. For example, children make pragmatic inferences after having played with a particular object or game (e.g., Akhtar, et al., 1996; Liebal, Behne, Carpenter, & Tomasello, 2009; MacPherson & Moore, 2010) and after observing another’s preference for a particular item (e.g., Repacholi & Gopnik, 1997; Saylor, Sabbagh, Foruna, & Troseth, 2009) as well as when faced with gestures and other similar cues (e.g., Baldwin, 1991; Moore, et al., 1999; Tomasello & Akhtar, 1995) Clearly, in several situations, pragmatic cues can provided valuable information to solve the mapping problem.

We are also not claiming that biases towards novelty are the sole driving force in children’s referent selection or word learning behaviors. Rather, we believe that the endogenous working of attention and associative learning are the platform upon which such inferences must be performed. That is, children’s understanding of pragmatic intent and the implications of prior social interactions for current word learning tasks must be integrated with the novelty-bias revealed in our task. On this view, these results suggest that novelty and salience are not simply low-level recoding of pragmatic or lexical principles–they are important components of word learning mechanisms in their own right.

The question, then, is how does a novelty bias of this sort emerge with respect to the more information-oriented processes involved in word learning? We see a number of possibilities that are shaped by the level of constraint offered by the referent selection task. In some cases, novelty may act as a sort of rough heuristic that would be fairly useful. Very often, the most novel available object will be the most likely referent of a novel word. Consequently, novelty may heighten children’s ability to quickly map objects and names by giving an attentional boost to particular objects. Thus, even if novelty does not serve as a source of information, novel objects may be attended to more readily than partially familiar, yet unnamed, objects. Such a mechanism could amplify effects in situations in which the objects are highly novel (e.g., tightly controlled laboratory experiments), and could weaken effects in other situations where objects that do not yet have names are more familiar (e.g., a home environment where several objects have been seen many times but never named). Biasing referent selection toward novel objects, would give children a quick-and-dirty entry point for word learning. Such a heuristic would clearly apply to situations like mutual exclusivity in which several known objects are presented with one novel object (Mervis & Bertrand, 1994), and may also apply more broadly. That is, a simple novelty bias could get children to the right referent faster than more complex inference-based processes.

In other cases, it is less clear how a novelty bias might emerge. Consider, for example, the learning-by-overhearing paradigm of Akhtar and colleagues (Akhtar, et al., 2001; Floor & Akhtar, 2006). This research involves a game in which the experimenter reveals four hidden objects—one of which is named. Twenty-four- and 30-month-old toddlers are very good at a later referent selection task, whether the child was addressed directly or was watching the experimenter show the objects to another adult (Akhtar et al., 2001). Similarly, half of 18-month-olds tested in this paradigm also succeed in the later referent selection task (Floor & Akhtar, 2006). An endogenous novelty bias might be problematic in weakly constrained situations like this—particularly if it conflicts with other information presented in the task. In the learning-by-overhearing situation, for example, if the child were not paying particularly close attention to the speaker/addressee, or if the social cues were ambiguous, a novelty bias may end up dominating and driving the child’s response (assuming that some objects are more familiar than others, as they will undoubtedly be in the real world).

Thus, the current results have implications for existing accounts of children’s behaviors in referent selection tasks. And, importantly, these results offer a basis for continuity between infant’s well-known attraction to novel objects, sounds and events and the processes at work in the first stages of word learning. In addition, these findings make two important theoretical contributions to the word learning literature and have considerable implications for approaches that view referent selection as the product of constraints or attentional mechanisms. First, referent selection is not always about finding the most optimal solution. In the literature, constraints or biases are frequently used to describe children’s behavior in canonical referent selection tasks. Principles like the mutual exclusivity principle (Markman & Wachtel, 1988), the novel-name-nameless-category constraint (Mervis & Bertrand, 1994), the lexical gap hypothesis (Golinkoff, Hirsh-Pasek, Bailey, & Wenger, 1992), and disjunctive syllogism (Halberda, 2006) all suggest a rational deduction of the most logical referent given the contents of the child’s current lexicon and the available referents. Bayesian approaches (e.g., Xu & Tenenbaum, 2007) are more graded and flexible, but still fundamentally frame the problem as determining the optimal solution given the available referents and children’s linguistic knowledge. Under these views, novelty is a source of information the child can use to determine the correct answer in referent selection tasks.

While we agree that on some level word learning certainly is a problem solving task, as these data demonstrate, children may engage in systematic behavior in a reference selection task that is not driven by the quest for the most optimal solution to the problem of referential ambiguity. As such, this laboratory task is not so dramatically different from learning situations in everyday life that do not offer any information or indication that children will find out if they are correct. Future research should examine (both empirically and computationally) what, if anything, children learn when their answers are not optimal—and, in some cases, even wrong (see, McMurray, Horst, & Samuelson, in prep).

Second, exposure to the referent is just as important as exposure to the name. McMurray, Horst, Toscano and Samuelson (2009) have recently developed a model of fast mapping and word learning from a dynamic competition/associative learning perspective According to this model, a small amount of learning occurs with each exposure to a name or object. Importantly, however, the learning for names and objects is independent: the child can learn something about the object categories without simultaneously learning anything about the possible object names (Horst, McMurray, & Samuelson, 2006; see also, Mayor & Plunkett, 2010). During fast mapping, then, dynamic competition processes force the child to make a decision based on the visual scene and any knowledge acquired previously (whether or not that knowledge is complete). On this view, because no naming occurred during the familiarization phase of the current experiments, the child could not learn the objects’ names or learn any name-object associations, but the child could still learn about the objects themselves. This small amount of learning could have created weak biases away from the familiarized objects—biases that drove children’s behavior when the objects were later presented with a completely novel object in the naming context.

It is important to note that in the context of McMurray et al.’s (2009) formal model, none of these mechanisms are willfully geared to optimal word learning—competition and association are simply hallmarks of neural processing. However, what emerges from these mechanisms is a system that, while it can do mutual exclusivity and other complex inference process, has quirks like the novelty bias. And note that here, we are reclaiming the term “bias” for its proper meaning: a simple predisposition to do one thing over another, not an informational principle.

Thus, word learning critically depends on an array of linguistic and non-linguistic processes that guide children’s behavior in real-time. And, referent selection, while certainly sensitive to informational processes, must co-develop along with more basic processes of attention, memory and novelty preferences (see also, Hirsh-Pasek, et al., 2000; Samuelson & Smith, 2000; Smith, 2000). Future explanations of children’s behavior in referent selection tasks will need to recognize these domain-general visual and attentional components (as well as other endogenous biases from the motor system, for example), which each have their own developmental histories and clearly shape the word learning future.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NICHD grant 5R01HD045713 to LKS. Portions of these data were presented at the 2009 Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development (Denver, USA) and New Directions in Word Learning (York, UK). We thank Richard Aslin for comments on an earlier version and Ryan Schiffer, Amanda Falk and the students in the Iowa Language and Category Development Laboratory for assistance in data collection. We also thank the parents and children who participated.

Footnotes

Before running the t-tests on children’s proportion of supernovel choices, we conducted tests of normality. Shapiro-Wilk’s test for normality confirmed that these data were normally distributed for both Experiment 1 (W(12) = .93, ns) and Experiment 2 (W(12) = .89, ns). In addition, we also ran non-parametric analyses using Chi-Square tests and obtained the same pattern of results.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akhtar N, Carpenter M, Tomasello M. The role of discourse novelty in early word learning. Child Development. 1996;67(2):635–645. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar N, Jipson J, Callanan MA. Learning words through overhearing. Child Development. 2001;72(2):416–430. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin DA. Infants’ contribution to the achievement of joint reference. Child Development. 1991;62:875–890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin DA, Markman EM. Infants’ ability to draw inferences about nonobvious object properties: Evidence from exploratory play. Child Development. 1993;64(3):711–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch SA, Bloom P. Preschoolers are sensitive to the speaker’s knowledge when learning proper names. Child Development. 2002;73(2):434–444. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth AE, Waxman SR. Mapping Words to the World in Infancy: Infants’ Expectations for Count Nouns and Adjectives. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2003;4(3):357–381. [Google Scholar]

- Corkum V, Moore C. The origins of joint visual attention in infants. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:28–38. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deák G, Flom R, Pick A. Effects of gesture and target on 12- and 18-month-olds’ joint visual attention to objects in front of or behind them. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:511–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diesendruck G, Markson L, Akhtar N, Reudor A. Two-year-olds’ sensitivity to speakers’ intent: An alternative account of Samuelson and Smith. Developmental Science. 2004;7(1):33–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2004.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantz RL. Visual experience in infants: Decreased attention familar patterns relative to novel ones. Science. 1964;146:668–670. doi: 10.1126/science.146.3644.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floor P, Akhtar N. Can 18-Month-Old Infants Learn Words by Listening In on Conversations? Infancy. 2006;9(3):327–339. doi: 10.1207/s15327078in0903_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganea P, Saylor M. Infants’ use of shared linguistic information to clarify ambiguous requests. Child Development. 2007;78(2):493–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golinkoff RM, Hirsh-Pasek K, Bailey LM, Wenger NR. Young-Children and Adults Use Lexical Principles to Learn New Nouns. Developmental Psychology. 1992;28(1):99–108. [Google Scholar]

- Grassmann S, Stracke M, Tomasello M. Two-Year-Olds Exclude Novel Objects as Potential Referents of Novel Words Based on Pragmatics. Cognition. in press doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halberda J. Is this a dax which I see before me? Use of the logical argument disjunctive syllogism supports word-learning in children and adults. Cognitive Psychology. 2006;53(4):310–344. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen MB, Markman EM. Children’s use of mutual exclusivity to learn labels for parts of objects. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45(2):592–596. doi: 10.1037/a0014838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart B, Risley TR. Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Baltimore, MD, USA: Paul H. Brookes Publishing; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Heibeck TH, Markman EM. Word Learning in Children - an Examination of Fast Mapping. Child Development. 1987;58(4):1021–1034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh-Pasek K, Golinkoff RM, Hollich G. An Emergentist Coalition Model for Word Learning: Mapping Words to Objects Is a Product of the Interaction of Multiple Cues. In: Golinkoff RM, Hirsh-Pasek K, Bloom L, Smith LB, Woodward AL, Akhtar N, Tomasello M, Hollich G, editors. Becoming a word learner: A debate on lexical acquisition. vii. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Horst JS, McMurray B, Samuelson LK. Online Processing is essential for leaning: Understanding fast mapping and word learning in a dynamic connectionist architecture. Proceedings from the 28th Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society. 2006:339–344. [Google Scholar]

- Horst JS, Samuelson LK. Fast Mapping But Poor Retention By 24-Month-Old Infants. Infancy. 2008;13(2):128–157. doi: 10.1080/15250000701795598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter MA, Ames EW. A multifactor model of infant preferences for novel and familiar stimuli. Advances in Infancy Research. 1988;5:69–95. [Google Scholar]

- Jaswal VK. Explaining the disambiguation effect: Don’t exclude mutual exclusivity. Journal of Child Language. 2010;37(1):95–113. doi: 10.1017/S0305000909009519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaswal VK, Markman EM. Learning proper and common names in inferential versus ostensive contexts. Child Development. 2001;72(3):768–786. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaswal VK, Markman EM. Looks aren’t everything: 24-month-olds’ willingness to accept unexpected labels. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2007;8(1):93–111. [Google Scholar]

- Liebal K, Behne T, Carpenter M, Tomasello M. Infants use shared experience to interpret pointing gestures. Developmental Science. 2009;12(2):264–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson AC, Moore C. Understanding Interest in the Second Year of Life. Infancy. 2010;15(3):324–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7078.2009.00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markman EM, Wachtel GF. Children’s use of mutual exclusivity to constrain the meaning of words. Cognitive Psychology. 1988;20(2):121–157. doi: 10.1016/0010-0285(88)90017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayor J, Plunkett K. A Neurocomputational Account of Taxonimic Responding and Fast Mapping in Early Word Learning. Psychological Review. 2010;117(1):1–31. doi: 10.1037/a0018130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurray B, Horst JS, Samuelson LK. Using Your Lexicon at Two Timescales: Investigating the Interplay Between Word Learning and Recognition. Manuscript in preparation in prep [Google Scholar]

- McMurray B, Horst JS, Toscano J, Samuelson LK. Connectionist Learning and Dynamic Processing: Symbiotic Developmental Mechanisms. In: Spencer JP, Thomas M, McClelland J, editors. Towards a New Grand Theory of Development? Connectionism and Dynamic Systems Theory Reconsidered. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 218–249. [Google Scholar]

- Mervis CB, Bertrand J. Acquisition of the Novel Name Nameless Category (N3c) Principle. Child Development. 1994;65(6):1646–1662. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll H, Carpenter M, Tomasello M. Fourteen-month-olds know what others experience only in joint engagement. Developmental Science. 2007;10(6):826–835. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll H, Tomasello M. How 14- and 18-month-olds know what others have experienced. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43(2):309–317. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore C. The development of gaze following. Child Development Perspectives. 2008;2(2):66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Moore C, Angelopoulos M, Bennett P. Word learning in the context of referential and salience cues. Developmental Psychology. 1999 Jan;35(1):60–68. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quine WVO. Word and object: An inquiry into the linguistic mechanisms of objective reference. Cambridge: MIT Press; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn PC, Eimas PD, Rosenkrantz SL. Evidence for representations of perceptually similar natural categories by 3-month-old and 4-month-old infants. Perception. 1993;22(4):463–475. doi: 10.1068/p220463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repacholi BM, Gopnik A. Early reasoning about desires: Evidence from 14- and 18-month-olds. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33(1):12–21. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbagh MA, Baldwin DA. Learning words from knowledgeable versus ignorant speakers: Links between preschoolers’ theory of mind and semantic development. Child Development. 2001;72(4):1054–1070. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson LK, Smith LB. Memory and attention make smart word learning: An alternative account of Akhtar, Carpenter, and Tomasello. Child Development. 1998;69(1):94–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson LK, Smith LB. Grounding development in cognitive processes. Child Development. 2000;71(1):98–106. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saylor MM, Sabbagh MA, Foruna A, Troseth G. Preschoolers use speakers’ preferences to learn words. Cognitive Development. 2009;24(2):125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Shinskey JL, Munakata Y. Familiarity Breeds Searching: Infants Reverse Their Novelty Preferences When Reaching for Hidden Objects. Psychological Science. 2005;16(8):596–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LB. Learning How to Learn Words: An Associative Crane. In: Golinkoff RM, Hirsh-Pasek K, Bloom L, Smith LB, Woodward AL, Akhtar N, Tomasello M, Hollich G, editors. Becoming a Word Learner: A Debate on Lexical Acquisition. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 51–80. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello M, Akhtar N. Two-year-olds use pragmatic cues to differentiate reference to objects and actions. Cognitive Development. 1995;10(2):201–224. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello M, Haberl K. Understanding attention: 12- and 18-month-olds know what is new for other persons. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39(5):906–912. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.5.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson KM, Mazzitelli K. The effect of ‘missing’ information on children’s retention of fast-mapped labels. Journal of Child Language. 2003;30(1):47–73. doi: 10.1017/s0305000902005469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Tenenbaum J. Word Learning as Bayesian Inference. Psychological Review. 2007;114(2):245–272. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.114.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]