Summary

Background and objectives

The cross-reactive antigen(s) of tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome from renal tubulointerstitia and ocular tissue remain unidentified. The authors' recent study demonstrated that the presence of serum IgG autoantibodies against modified C-reactive protein (mCRP) was closely associated with the intensity of tubulointerstitial lesions in lupus nephritis. The study presented here investigates the possible role of IgG autoantibodies against mCRP in patients with TINU syndrome.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

mCRP autoantibodies were screened by ELISA with purified human C-reactive protein in 9 patients with TINU syndrome, 11 with drug-associated acute interstitial nephritis, 20 with IgA nephropathy, 19 with minimal change disease, 20 with ANCA-associated vasculitis, 6 with Sjogren's syndrome, and 12 with amyloidosis. mCRP expression was analyzed by immunohistochemistry in renal biopsy specimens from the 9 patients with TINU syndrome and 40 from disease controls. Frozen normal human kidney and iris were used to demonstrate co-localization of human IgG and mCRP from patients with TINU syndrome with laser scanning confocal microscopy.

Results

The mCRP autoantibodies were detected in all nine patients with TINU syndrome, significantly higher than that of those with disease controls (P < 0.05). The renal histologic score of mCRP in TINU syndrome was significantly higher than that in disease controls (P < 0.05). The staining of mCRP and human IgG were co-localized in renal and ocular tissues.

Conclusions

It is concluded that mCRP might be a target autoantigen in TINU syndrome.

Introduction

Acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) defines a pattern of renal injury that is usually associated with an abrupt deterioration in renal function. The causes of AIN usually fall within one of three general categories: drug induced, infection associated, and autoimmune mediated. The third category includes Sjögren's syndrome, lupus nephritis, and tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome.

TINU syndrome is characterized by tubulointerstitial nephritis with bilateral sudden-onset anterior uveitis (1). Since the first description in 1975 by Dobrin et al. (2), over 200 cases have been described in the literature with a median age of onset at 15 years (range 9 to 74 years) and a 3:1 female-to-male predominance (3).

The pathogenesis of TINU is not clear, but it is thought to be the result of an autoimmune process that might involve humoral and cellular autoimmunity (4,5). Renal tubular and ciliary body epithelia share some similar functions, such as those pertaining to electrolyte transporters sensitive to carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Thus, it is conceivable that they might share cross-reactive autoantigens (6,7). A recent study demonstrated the presence of autoantibodies recognizing a common autoantigen found in tubular and uveal cells in the serum of a 15-year-old girl suffering from TINU (8). However, an exact cross-reactive autoantigen in TINU syndrome has yet to be identified.

Plasma C-reactive protein (CRP), a member of the pentraxin family, is composed of five identical nonglycosylated polypeptide subunits. Under certain conditions such as altered pH, high urea concentration, or low calcium concentration, native CRP dissociates irreversibly into monomers, also called modified CRP (mCRP). mCRP undergoes conformational rearrangement that results in expression of an isomer with distinct antigenic and physiochemical characteristics (9). mCRP is considered to be a tissue and/or cell-based form of the acute phase protein with less understood properties and biologic effects (9–13). mCRP may be produced by various cells, such as lymphocytes (14), smooth muscle cells (15), and renal tubular epithelial cells (16). Our previous study found that the level of anti-mCRP autoantibodies in sera from patients with lupus nephritis was closely associated with the score of their interstitial lesions (17). We speculated that anti-mCRP autoantibodies might exist in patients with TINU syndrome and might be a link between the kidney and eye in the syndrome.

In this study, we report a novel common autoantigen that renal and ocular tissues might share. Anti-mCRP autoantibodies were detected in all of the patients with TINU syndrome; upregulated expression of mCRP was found in renal biopsies of patients, and IgG from patients with TINU syndrome was co-localized with mCRP in human renal and uveal tissues.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Sera from nine consecutive patients with TINU syndrome, admitted to our hospital between January 1999 and August 2008, were collected on the day of renal biopsy. Sera from three patients with TINU syndrome were also obtained during follow-up, and serum from one patient was obtained sequentially in remission and at the occurrence of uveitis.

The diagnosis of TINU was based on the criteria described by Mandeville et al. (3), histopathology-proven AIN and typical uveitis (bilateral anterior uveitis with or without intermediate uveitis or posterior uveitis, onset of uveitis 2 months before or 12 months after AIN). Complete remission of TINU syndrome was defined as the presence of normal renal function and normal visual acuity maintained at 20/25. The detailed clinical and pathologic data were retrospectively reviewed (3).

Sera from patients with drug-associated AIN (n = 11), IgA nephropathy (n = 20), minimal change disease (MCD) (n = 19), ANCA-associated vasculitis (n = 20), Sjogren's syndrome (n = 6), and amyloidosis (n = 12) were collected on the day of renal biopsy before administration of immunosuppressive treatment. Sera from 60 healthy subjects with matched gender and age were collected as normal controls. All of the sera were stored at −70°C until use.

Consecutive renal biopsies from every ten patients with MCD, AIN, IgA nephropathy, and ANCA-associated vasculitis were used as histologic controls. Normal portion of human kidney cortex was obtained from nephrectomized specimens of patients with kidney tumors. Normal portion of iris and ciliary body was obtained from patients with trabeculectomy. Informed consent was obtained for blood sampling and renal biopsy from each patient. The research was in compliance of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Detection of mCRP Autoantibodies by ELISA

Autoantibodies against mCRP were detected by ELISA as described (17). Briefly, human CRP (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), diluted to 5.6 μg/ml with 0.05 mol/L in bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6), was coated onto one half of polystyrene microtiter plates (Costar, Corning, NY) with the other half coated with bicarbonate buffer alone as antigen-free wells for 1 hour at 37°C. Free binding sites were blocked with PBS containing 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (PBST) and 1% BSA for 1 hour at 37°C. Sera were diluted to 1:50 in PBST. The volumes of this step and subsequent steps were 100 μl. The plates were washed 3 times with PBST. The binding was detected by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-human IgG antibodies (Life Technologies BRL, Grand Island, NY) with a dilution of 1:5000. The HRP substrate O-phenylenediamine was used at 0.4 mg/ml in 0.1 mmol/L citrate phosphate buffer (pH 5.0). The reaction was stopped by 1.0 mol/L sulfuric acid and results were recorded as the net OD490 nm (average value of antigen-coated wells minus average value of antigen-free wells). The binding of a known positive control serum was regarded as 100%, and the bindings of the tested sera were expressed as percentages of the known positive sample. The cutoff value was set as the mean ± 2 SD of the 60 normal controls.

Renal and Uveal Expression of mCRP by Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining of mCRP was performed on 4-μm deparaffinized sections of formaldehyde-fixed renal tissue using mouse monoclonal anti-human mCRP-antibodies (clone 8, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) as described previously with little modification (9). Briefly, sections were deparaffinized in xylene-ethanol at room temperature and rehydrated immediately in PBS, then immersed into freshly prepared 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol solution for 10 minutes at room temperature to quench endogenous peroxidase activity. To block nonspecific staining, sections were incubated with 3% BSA in PBS at 37°C for 30 minutes. The primary antibodies were directly added on each section and were incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. The detection system used, Dako EnVision HRP (Dako A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark), was an avidin-free two-step indirect method with goat anti-mouse immunoglobulins conjugated with HRP as secondary antibodies. The secondary antibodies were incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C. Sections were developed in fresh hydrogen peroxide plus 3–3-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride solution for 3 minutes. Finally, sections were counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin. As a negative control, primary antibodies were replaced by PBS. The extent of tubulointerstitial staining for mCRP was evaluated at 400× magnification and scored semiquantitatively: 0, no staining; 1, weak and spotty staining; 2, moderate and patchy staining; and 3, strong and diffuse staining. Two independent investigators scored the intensity of mCRP expression, and the final score was determined as the mean of the two scores from the two investigators.

Co-Localization of mCRP and IgG from Patients with TINU Syndrome by Immunofluorescence Using Laser Scanning Confocal Microscopy

Sections at a thickness of 5 μm from frozen human renal biopsy tissue and frozen iris tissue were air-dried at room temperature for 30 minutes and fixed in iced acetone for 10 minutes. Between stages, the sections were washed 3 times with PBS for 10 minutes. The mouse monoclonal anti-human CRP-antibodies (clone 8, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) diluted at 1:200 were incubated at 37°C for 1 hour as primary antibodies. As a negative control, PBS replaced primary antibodies. Sera from patients with TINU syndrome, MCD, and AIN were diluted at 1:5, were added to the sections, and were incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. As a negative control, sera from normal controls replaced sera from patients. Rhodamine (TRITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology, Beijing, China) diluted at 1:40 was used as secondary antibodies at 37°C for 30 minutes. Then, FITC-conjugated rabbit anti-human IgG (Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology, Beijing, China) diluted at 1:40 was added to the sections. Co-localization of mCRP and human IgG from patients with TINU syndrome were judged by merging of the green fluorescence of FITC and the red fluorescence of TRITC.

Statistical Analyses

For statistical analyses, statistical software SPSS 10.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) was used. Quantitative data were expressed as mean ± SD, and median with range (25th percentile, 75th percentile). For comparison between patients and controls, the t test was used. For correlation between histologic scores and levels of autoantibodies, the Spearman correlation was performed. Statistical significance was considered as P < 0.05.

Results

Demographic Features of Patients with TINU Syndrome and Disease Controls

As shown in Table 1, of the nine patients with TINU syndrome, seven patients were female and two were male with a mean age of 45.2 ± 15.7 years. They were diagnosed with TINU syndrome by renal histopathology and ophthalmological examination (3). All nine patients presented with acute kidney injury and their mean serum creatinine at presentation was 241.22 ± 112.47 μmol/L. Topical steroids for the eyes were prescribed to all patients. Oral prednisone (median initial dosage, 30 mg/d, 4 weeks) were prescribed to eight patients, among whom cyclophosphamide was administrated (intravenous 0.6 g, twice only, or oral 50 mg/d) for two patients. The serum creatinine of all of the patients normalized within 2 to 4 months after the above therapy. The demographic and clinical features of patients with TINU syndrome and disease controls are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, and laboratory features of the nine patients with TINU syndrome

| Patient number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | M | F | F | M | F | F | F | F | F |

| Age | 16 | 74 | 43 | 37 | 40 | 51 | 41 | 56 | 49 |

| Interval between initiation of nephritis and uveitis (months) | <12 | <12 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| Fever | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Fatigue | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Weight loss | Y | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Lymph node enlargement | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Right neck | Right maxilla |

| Acute kidney injury | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 113 | 92 | 110 | 106 | 97 | 89 | 99 | 137 | 102 |

| Leukocytes in urine (/HP) | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y |

| Hematuria | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N |

| Proteinuria (g/24 h) | NA | 0.84 | 1.29 | 0.38 | 0.98 | 0.8 | 1.76 | 1.32 | 1.85 |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L) | 173 | 524 | 158 | 191 | 248 | 270 | 170 | 210 | 227 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 50 | 141 | 33 | 32 | 135 | 45. | NA | 70 | 54 |

| CRP (normal range <8 mg/L) | 4.81 | 71.5 | 3.69 | 2.08 | 59 | 2.73 | 2.59 | 18.5 | 11.4 |

| IgG (g/L) | NA | NA | 15.2 | 15 | 20.7 | 18.4 | 12.9 | 18.1 | 19.3 |

| IgA (g/L) | NA | NA | 1.28 | 3.34 | 2.17 | 3.41 | 4.69 | 3.8 | 1.11 |

| IgM (g/L) | NA | NA | 4.84 | 1.00 | 1.28 | 2.39 | 2.25 | 3.56 | 5.03 |

| C3 (normal range >0.8g/L) | 1.51 | 1.53 | 1.1 | 0.87 | 1.51 | 0.82 | 0.7 | 1.43 | 0.21 |

M, male; F, female; NA, information not available; N, no; Y, yes; L, left; R, right; HP, high-powered field; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

Table 2.

Demographic features of disease controls

| Demographic | AIN (n = 11) | IgA Nephropathy (n = 20) | MCD (n = 19) | ANCA-Associated Vasculitis (n = 20) | Sjogren's Syndrome (n = 6) | Amyloidosis (n = 12) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (Female/male) | 9/2 | 9/11 | 4/15 | 9/11 | 4/2 | 4/8 |

| Age (years) | 43.6 ± 18.8 | 31.7 ± 6.7 | 24.8 ± 9.2 | 61.8 ± 15.4 | 42.8 ± 11.7 | 56.4 ± 13.1 |

Table 3.

Laboratory features of patients with TINU syndrome and drug-induced AIN

| Clinical Features | Patients with TINU Syndrome (n = 9) | Patients with AIN (n = 11) |

|---|---|---|

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L) | 241.22 ± 112.47 | 292.4 ± 168.93 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 94.33 ± 33.31 | 103.45 ± 12.27 |

| Proteinuria (g/24 h) | 1.15 ± 0.50 | 1.48 ± 0.55 |

| C3 (g/L) | 1.08 ± 0.46 | 1.13 ± 0.32 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 19.59 ± 26.60 | 13.46 ± 18.25 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 70.00 ± 43.69 | 70.67 ± 26.94 |

| IgG (g/L) | 17.09 ± 2.77 | 16.62 ± 4.91 |

| IgA (g/L) | 2.83 ± 1.34 | 3.72 ± 1.08 |

| IgM (g/L) | 2.91 ± 1.62 | 2.27 ± 1.19 |

Prevalence of Serum Autoantibodies against mCRP in Patients with TINU Syndrome and in Controls

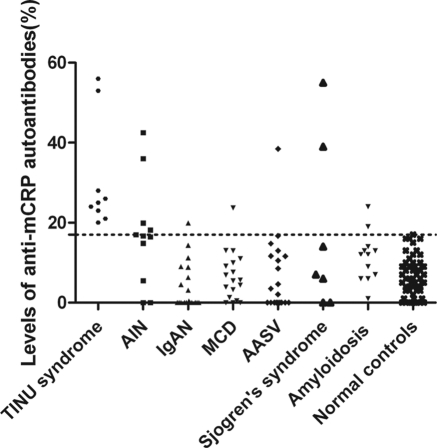

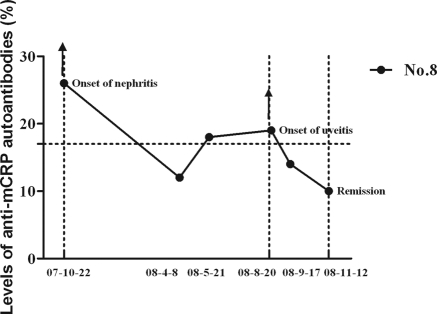

The cutoff value of the ELISA was 17%. The serum mCRP autoantibodies were detected in all nine patients (100%) with TINU syndrome in active phase, which was significantly higher than that with AIN (4 of 11, 36.3%, P = 0.013), IgA nephropathy (1 of 20, 5.0%, P < 0.001), MCD (1 of 19, 5.0%, P < 0.001), ANCA-associated vasculitis (1 of 20, 5.0%, P < 0.001), Sjogren's syndrome (1 of 6, 28.6% P = 0.005), and amyloidosis (2 of 12, 16.7%, P = 0.001). None of the 60 healthy controls were positive for mCRP autoantibodies (Figure 1). The mCRP autoantibodies in two of three of patients with TINU syndrome with follow-up data turned negative in remission (mean interval: 3.13 months). We collected sequential sera from one patient who developed uveitis during follow-up (patient 8). The mCRP autoantibodies were positive at onset of acute tubulointerstitial nephritis and turned negative in remission, but the mCRP autoantibodies became positive weeks before the development of uveitis and turned to negative again when disease was in the quiescent phase (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Levels of serum mCRP autoantibodies from patients with TINU syndrome and controls. The horizontal dashed line indicates the cutoff value (17%).

Figure 2.

The change of serum mCRP autoantibody levels in patients with TINU syndrome from active phase to remission and the levels of serum mCRP autoantibodies from one patient (patient 8) with sequential sera. The horizontal dashed line indicates the cutoff value (17%).

Pathologic Association of mCRP Autoantibodies

Semiquantitative scores of renal histologic features were explored to evaluate the tubulointerstitial lesions in the kidney, including interstitial inflammatory cell infiltration, interstitial edema, interstitial fibrosis, tubular injury, tubulitis, and tubular atrophy (18). The levels of anti-mCRP autoantibodies were closely correlated with interstitial fibrosis (r = 0.766, P = 0.016) in TINU syndrome. No correlation was found between the levels of mCRP autoantibodies and semiquantitative scores of tubulointerstitial lesions in disease controls (Table 4).

Table 4.

Semiquantitative scores of tubulointerstitial lesions in patients with TINU syndrome and disease controls

| Statistic | TINU Syndrome (n = 9) | AIN (n = 11) | IgA Nephropathy (n = 20) | MCD (n = 19) | ANCA-Associated Vasculitis (n = 20) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interstitial inflammation | |||||

| median (range) | 3 (3,3) | 3 (3,3) | 2 (1,3) | 0 (0,0) | 3 (1.25,3) |

| r | ND | ND | −0.316 | 0.220 | −0.022 |

| P | 0.202 | 0.366 | 0.930 | ||

| Interstitial edema | |||||

| median (range) | 0 (0,0.5) | 0.5 (0,1.25) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) |

| r | −0.207 | −0.551 | ND | ND | −0.219 |

| P | 0.593 | 0.099 | 0.382 | ||

| Tubulitis | |||||

| median (range) | 1 (1,1) | 1 (0.75,1) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) | 1 (0,1) |

| r | −0.137 | 0.264 | 0.000 | ND | 0.499 |

| P | 0.725 | 0.460 | 1.000 | 0.062 | |

| Tubular injury | |||||

| median (range) | 0 (0,1) | 0.5 (0,1.25) | 0 (0,1) | 0 (0,0) | 1 (0,1) |

| r | 0.456 | 0.007 | −0.010 | 0.086 | 0.254 |

| P | 0.217 | 0.985 | 0.970 | 0.726 | 0.308 |

| Interstitial fibrosis | |||||

| median (range) | 1 (0,1.5) | 1 (0,1) | 1 (0,2) | 0 (0,0) | 1 (1,1) |

| r | 0.766 | 0.393 | 0.232 | 0.086 | 0.021 |

| P | 0.016 | 0.261 | 0.354 | 0.726 | 0.934 |

| Tubular atrophy | |||||

| median (range) | 3 (2.5,3) | 3 (2.75,3) | 1 (1,3) | 0 (0,1) | 2 (1.25,3) |

| r | −0.502 | −0.123 | 0.144 | −0.136 | 0.048 |

| P | 0.168 | 0.736 | 0.520 | 0.577 | 0.849 |

Range shown as 25th percentile, 75th percentile. ND, not detectable.

Semiquantitation of mCRP Expression by Immunohistochemistry in Patients with TINU Syndrome and Disease Controls

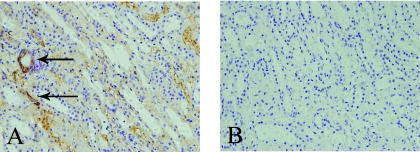

The expression of mCRP was further measured semiquantitively using immunohistochemistry in the 9 patients with TINU syndrome and in 40 patients from disease controls.

The mCRP signal was observed in the cytoplasm of tubules and interstitia of renal biopsies from all nine patients with TINU syndrome, seven of the ten patients with MCD, three of the ten with AIN, five of the ten with IgA nephropathy, and nine of the ten with ANCA-associated vasculitis (Figure 3). However, the mean histologic score in patients with TINU syndrome (2.0 ± 0.9) was significantly higher than that in those with MCD (1.0 ± 0.8, P = 0.002), with AIN (0.3 ± 0.5, P < 0.001), with IgA nephropathy (0.5 ± 0.5, P < 0.001), and with ANCA-associated vasculitis (1.3 ± 0.7, P = 0.032).

Figure 3.

Staining of mCRP by immunohistochemistry in patients with TINU syndrome with monoclonal antibodies against human mCRP. The mCRP signal (brown) was demonstrated using the HRP technique in renal biopsy tissues. Nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin. (A) Renal histologic score of 3+ for mCRP, with the cytoplasm of renal tubular epithelial cells and interstitia showing mCRP positivity (arrows), 200×. (B) Negative control of the same renal tissue, 200×.

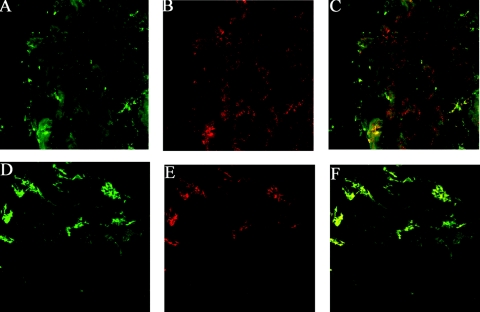

Co-Localization of mCRP and IgG from Patients with TINU Syndrome by Immunofluorescence with Laser Scanning Confocal Microscopy

The mCRP could be detected in normal tubular epithelial cells, interstitia, and uveal cells of normal tissue (Figure 4, B and E). When sera from patients with TINU syndrome were incubated with the above tissue sections, IgG deposition in tubular epithelial cells (Figure 4A) and in uveal cells (Figure 4D) was identified. The renal staining of mCRP and IgG could be partially merged (9 of 9), and the ocular staining could be largely (3 of 9) or partially (6 of 9) merged as observed with confocal microscopy (Figure 4, C and F). There was no IgG deposition in sections incubated with sera from normal control or patients with AIN or MCD.

Figure 4.

Co-localization of mCRP and IgG from patients with TINU syndrome by immunofluorescence using laser scanning confocal microscopy. (A) Indirect immunofluorescence with anti-human IgG antibodies indicated focal cytoplasmic staining in renal tubular cells in a renal biopsy section (600×). (B) Direct immunofluorescence with anti-mCRP antibodies indicated focal cytoplasmic staining in tubular cells of the same renal biopsy section. (C) The merged image of expression of mCRP and human IgG from a patient with TINU syndrome (600×). (D) Indirect immunofluorescence with anti-IgG antibodies indicated membranous positive staining in human ciliary body cells and iris (600×). (E) Direct immunofluorescence with anti-mCRP antibodies indicated staining in ciliary body cells and iris of the same ocular section. (F) The merged image of expression of mCRP and human IgG from a patient with TINU syndrome (600×).

Discussion

TINU syndrome is an oculorenal syndrome that is considered to be underdiagnosed and may be far more common than currently appreciated. Young patients with mild renal disease may not be identified at the time of presentation (1). Although the pathophysiology of TINU is still poorly understood, the current view suggests that it is an autoimmune process. Cell-mediated immune responses and autoantibody production have been implicated (4,5).

In the study presented here, we demonstrate for the first time a high prevalence of serum anti-mCRP autoantibodies in patients with TINU syndrome. These results suggest that mCRP may be one of the common target autoantigens in renal and ocular tissues in patients with TINU syndrome. In comparison with other renal diseases and normal controls, the high prevalence of serum anti-mCRP autoantibodies in TINU syndrome was impressive, especially in the active phase of nephritis. Furthermore, the levels of anti-mCRP autoantibodies, in two of the three patients whose sera were collected during follow-up, decreased in remission. We also sequentially collected sera from one patient (patient 8) initially diagnosed with AIN whose uveitis occurred 11 months later during follow-up. Interestingly, it was found that the levels of mCRP autoantibodies decreased significantly from onset to remission; however, the mCRP autoantibodies became positive weeks before the occurrence of uveitis and turned negative after steroid therapy. These findings indicate that the anti-mCRP autoantibodies were temporally associated with nephritis and uveitis in this patient. However, the usefulness of mCRP autoantibodies used as a serologic biomarker for the diagnosis and evaluation of disease activity for patients with TINU syndrome will require additional study.

Previous studies found that specific basement membrane antigens were immunogenic in animal models of AIN, and some patients with AIN had autoantibodies to the tubular basement membranes (TBMs) (3). Indirect immunofluorescence using sera from patients with anti-TBM nephritis revealed autoantigen localization in the TBMs of proximal and distal tubules, Bowman's capsule, and the basal membrane of the intestinal mucosa (19,20). A few patients with TINU syndrome were reported to have immunofluorescent TBM staining, indicating antibody deposition (21,22). However, the identification of common target autoantigen(s) in renal and ocular tissues for patients with TINU syndrome has been disappointing. Last year, Abed et al. (8) reported convincing evidence for a common target autoantigen in tubular and uveal cells. They demonstrated the presence of autoantibodies recognizing a common autoantigen in tubular and uveal cells in the serum of a 15-year-old girl suffering from TINU. Using indirect immunofluorescence, they showed that the patient's serum stained normal human kidney and normal mouse eye. There were clear focal cytoplasmic IgG deposits on renal proximal and distal tubular epithelial cells and membranous IgG deposits in uveal cells (ciliary body and iris). However, the autoantigen(s) were not identified and it is unknown whether human and mouse eyes share the same antigen or epitope(s).

Thus, we suggest that mCRP may be one of the common target autoantigens in renal and ocular tissues for patients with TINU syndrome. To strengthen this possibility, we performed immunohistochemical staining and found that the expression of mCRP was upregulated in the renal tubules and interstitia of patients with TINU syndrome in comparison with disease controls.

Moreover, we demonstrated co-localization of mCRP and human IgG from patients with TINU syndrome using immunofluorescence and laser scanning confocal microscopy (Figure 4). Furthermore, this is the first demonstration of mCRP expression in normal human iris and ciliary body. This suggests that the anti-mCRP autoantibodies might bind to overexpressed mCRP in renal and ocular tissues and thus may induce subsequent renal and eye injury. Interestingly, our study showed the existence of serum autoantibodies against mCRP and upregulated expression of mCRP in tubular cells of patients with TINU syndrome by indirect immunofluorescence. However, the direct immunofluorescence performed on renal biopsy specimens of our patient failed to demonstrate IgG deposition, similar to the report mentioned above (8).

Dual roles for mCRP exist in the innate immune system; mCRP may not only facilitate the safe clearance of damaged self-materials, but can also protect against unwanted complement activation in the fluid phase (23). mCRP exhibits complement-activating activity of the early components of the classical complement pathway by binding to C1q, leading to the turnover of C3, largely bypassing the more inflammatory and destructive terminal sequence by binding of factor H (23). Autoantibodies against mCRP might interrupt its normal biologic functions and lead to excessive complement activation with persistent renal and ocular injury. Several lines of evidence demonstrate the involvement of the complement cascade in the pathogenesis of acute TINU (24–26).

Our study is limited to a single center with nine patients. In addition, we did not purify the anti-mCRP autoantibodies from patients with TINU syndrome to stain normal patients' renal and ocular tissues. Further studies are needed in a larger cohort of patients with TINU syndrome to prove that mCRP autoantibodies are pathogenic in the disease. Nevertheless, this study demonstrates that autoantibodies against mCRP are prevalent in patients with TINU syndrome and sera from affected patients recognize mCRP in the kidney and eye. Therefore, mCRP might be one of the common target autoantigens in renal and ocular tissues for patients with TINU syndrome.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars (No. 30725034), the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (No.7102150), and the Program for New Century Excellent Talent in University (No. BMU 20100013). We are very grateful to Professors Bradley M. Denker and Wenchao Song for helping us improve our English writing.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1. Mackensen F, Smith JR, Rosenbaum JT: Enhanced recognition, treatment, and prognosis of tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome. Ophthalmology 114: 995–999, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dobrin RS, Vernier RL, Fish AL: Acute eosinophilic interstitial nephritis and renal failure with bone marrow-lymph node granulomas and anterior uveitis. A new syndrome. Am J Med 59: 325–333, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mandeville JT, Levinson RD, Holland GN: The tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol 46: 195–208, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gafter U, Kalechman Y, Zevin D, Korzets A, Livni E, Klein T, Sredni B, Levi J: Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis: Association with suppressed cellular immunity. Nephrol Dial Transplant 8: 821–826, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yoshioka K, Takemura T, Kanasaki M, Akano N, Maki S: Acute interstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome: Activated immune cell infiltration in the kidney. Pediatr Nephrol 5: 232–234, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Izzedine H: Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome (TINU): A step forward to understanding an elusive oculorenal syndrome [Comment]. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 1095–1097, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sugimoto T, Tanaka Y, Morita Y, Kume S, Uzu T, Kashiwagi A: Is tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome associated with IgG4-related systemic disease? Nephrology 13: 89, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abed L, Merouani A, Haddad E, Benoit G, Oligny LL, Sartelet H: Presence of autoantibodies against tubular and uveal cells in a patient with tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome [see comment]. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 1452–1455, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schwedler SB, Guderian F, Dammrich J, Potempa LA, Wanner C: Tubular staining of modified C-reactive protein in diabetic chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18: 2300–2307, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shoenfeld Y, Szyper-Kravitz M, Witte T, Doria A, Tsutsumi A, Tatsuya A, Dayer JM, Roux-Lombard P, Fontao L, Kallenberg CG, Bijl M, Matthias T, Fraser A, Zandman-Goddard G, Blank M, Gilburd B, Meroni PL: Autoantibodies against protective molecules—C1q, C-reactive protein, serum amyloid P, mannose-binding lectin, and apolipoprotein A1: Prevalence in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann NY Acad Sci 1108: 227–239, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mihlan M, Stippa S, Jozsi M, Zipfel PF: Monomeric CRP contributes to complement control in fluid phase and on cellular surfaces and increases phagocytosis by recruiting factor H. Cell Death Differ 16: 1630–1640, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rees RF, Gewurz H, Siegel JN, Coon J, Potempa LA: Expression of a C-reactive protein neoantigen (neo-CRP) in inflamed rabbit liver and muscle. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 48: 95–107, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Diehl EE, Haines GK, III, Radosevich JA, Potempa LA: Immunohistochemical localization of modified C-reactive protein antigen in normal vascular tissue. Am J Med Sci 319: 79–83, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kuta AE, Baum LL: C-reactive protein is produced by a small number of normal human peripheral blood lymphocytes. J Exp Med 164: 321–326, 1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Calabro P, Willerson JT, Yeh ET: Inflammatory cytokines stimulated C-reactive protein production by human coronary artery smooth muscle cells. Circulation 108: 1930–1932, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jabs WJ, L B, Gerke P, Kreft B, Wolber EM, Klinger MH, Fricke L, Steinhoff J: The kidney as a second site of human C-reactive protein formation in vivo. Eur J Immunol 33: 152–161, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lu JH, Teh BK, Wang L, Wang YN, Tan YS, Lai MC, Reid KB: The classical and regulatory functions of C1q in immunity and autoimmunity. Cell Mol Immunol 5: 9–21, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Racusen LC, Solez K, Colvin RB, Bonsib SM, Castro MC, Cavallo T, Croker BP, Demetris AJ, Drachenberg CB, Fogo AB, Furness P, Gaber LW, Gibson IW, Glotz D, Goldberg JC, Grande J, Halloran PF, Hansen HE, Hartley B, Hayry PJ, Hill CM, Hoffman EO, Hunsicker LG, Lindblad AS, Yamaguchi Y, et al. : The Banff 97 working classification of renal allograft pathology. Kidney Int 55: 713–723, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lehman DH, Wilson CB, Dixon FJ: Interstitial nephritis in rats immunized with heterologous tubular basement membrane. Kidney Int 5: 187–195, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Miyazato H, Yoshioka K, Hino S, Aya N, Matsuo S, Suzuki N, Suzuki Y, Sinohara H, Maki S: The target antigen of anti-tubular basement membrane antibody-mediated interstitial nephritis. Autoimmunity 18: 259–265, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morino M, Uryu T, Yoshikawa T: A case of uveitis associated with tubulointerstitial nephritis [in Japanese]. Nippon Jinzo Gakkai Shi 25: 1027–1034, 1983 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wakaki H, Sakamoto H, Awazu M: Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome with autoantibody directed to renal tubular cells. Pediatrics 107: 1443–1446, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ji SR, Wu Y, Potempa LA, Liang YH, Zhao J: Effect of modified C-reactive protein on complement activation: A possible complement regulatory role of modified or monomeric C-reactive protein in atherosclerotic lesions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 26: 935–941, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. David S, Biancone L, Caserta C, Bussolati B, Cambi V, Camussi G: Alternative pathway complement activation induces proinflammatory activity in human proximal tubular epithelial cells. Nephrol Dial Transplant 12: 51–56, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bora NS, Jha P, Bora PS: The role of complement in ocular pathology. Semin Immunopathol 30: 85–95, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jha P, Sohn JH, Xu Q, Nishihori H, Wang Y, Nishihori S, Manickam B, Kaplan HJ, Bora PS, Bora NS: The complement system plays a critical role in the development of experimental autoimmune anterior uveitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 47: 1030–1038, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]