Abstract

Sucrose non-fermenting-1-related protein kinase 2 (SnRK2) plays a key role in the plant stress signalling transduction pathway via phosphorylation. Here, a SnRK2 member of common wheat, TaSnRK2.7, was cloned and characterized. Southern blot analysis suggested that the common wheat genome contains three copies of TaSnRK2.7. Subcellular localization showed the presence of TaSnRK2.7 in the cell membrane, cytoplasm, and nucleus. Expression patterns revealed that TaSnRK2.7 is expressed strongly in roots, and responds to polyethylene glycol, NaCl, and cold stress, but not to abscisic acid (ABA) application, suggesting that TaSnRK2.7 might participate in non-ABA-dependent signal transduction pathways. TaSnRK2.7 was transferred to Arabidopsis under the control of the CaMV-35S promoter. Function analysis showed that TaSnRK2.7 is involved in carbohydrate metabolism, decreasing osmotic potential, enhancing photosystem II activity, and promoting root growth. Its overexpression results in enhanced tolerance to multi-abiotic stress. Therefore, TaSnRK2.7 is a multifunctional regulatory factor in plants, and has the potential to be utilized in transgenic breeding to improve abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants.

Keywords: Abiotic stress response, expression pattern, morphological character, physiological trait

Introduction

Reversible protein phosphorylation is central to the perception of, and response to, water deficit (Hirt, 1997), and constitutes a major mechanism for the control of cellular functions, such as responses to hormonal, pathogenic and environmental stimuli, and control of metabolism (Cohen, 1988).

The sucrose non-fermenting-1 (SNF1) protein kinase family, belonging to the CDPK–SnRK superfamily (Hrabak et al., 2003), currently comprises SNF1 in yeast, AMP-activated protein kinases (AMPKs) in mammals, and SNF1-related protein kinases (SnRKs) in higher plants. According to sequence similarity, domain structure, and cellular function, the plant SnRK subfamily can be divided into three subgroups, SnRK1, SnRK2, and SnRK3 (Hrabak et al., 2003). SnRK1 kinase is well characterized at the molecular and biochemical levels, and evidence indicates that SnRK1s play an important role in regulating carbon metabolism and sucrose signals in plants (Halford and Hardie, 1998). Unlike SnRK1, SnRK2 and SnRK3 are unique to plants and are involved in responses to environmental stresses (Halford and Hey, 2009). Several SnRK3 members have been extensively characterized. The best known member, SOS2, participates in ionic homeostasis to high salt stress in Arabidopsis (Halfter et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2000). Furthermore, SOS2 and PKS3 (SOS2-like protein kinase) interacted specifically with abscisic acid (ABA)-insensitive 2 (ABI2) phosphatase (Guo et al., 2002; Ohta et al., 2003). Therefore, it was suggested that the SnRK3 family might be part of a calcium-responsive regulatory loop controlling ABA sensitivity or might function as a cross-talk node in complex signalling networks (Kim et al., 2003).

Increasing evidence shows that SnRK2 genes play important roles in abiotic stress responses in plants. The first two SnRK2s in Arabidopsis, ASK1 and ASK2, were cloned in 1993 (Park et al., 1993). Until now, 10 SnRK2s have been identified in Arabidopsis; nine of them were activated by hyperosmotic and salinity stresses, and five of the nine were activated by ABA, whereas none was activated by cold stress (Boudsocq et al., 2007). Overexpression of AtSnRK2.8/AtSnRK2C led to enhanced drought tolerance in Arabidopsis (Umezawa et al., 2004). AtSRK2.6/AtSnRK2E/OST1 was involved in ABA regulation of stomatal closing and ABA-regulated gene expression (Mustilli et al., 2002). In rice, 10 members were identified and designated SAPK1–10. All were activated by hyperosmotic stress, and SAPK8–10 were also activated by ABA (Kobayashi et al., 2004). Overexpression of SAPK4 significantly enhanced salt tolerance in rice (Diedhiou et al., 2008). Recently, 10 maize SnRK2 members were cloned, and most ZmSnRK2s were induced by one or more abiotic stresses (Huai et al., 2008). In wheat, an SnRK2 member, PKABA1, was induced by ABA and dehydration stress, and it repressed the activity of gibberellic acid-inducible promoters when transiently overexpressed in barley aleurone layers (Anderberg and Walker-Simmons, 1992; Gomez-Cadenas et al., 1999). In our recent study, the wheat TaSnRK2.4 gene, expressed strongly in booting spindles compared with leaves, roots, and spikes, was induced by multi-stresses and ABA application. Overexpression of TaSnRK2.4 resulted in delayed seedling establishment, longer primary roots, and enhanced tolerance to abiotic stresses in Arabidopsis (Mao et al., 2010). Although evidence shows that SnRK2s function in abiotic stress signalling in plants and are activated very rapidly in response to osmotic stress, knowledge of specific functions of SnRK2s is fragmentary.

In this study, we isolated TaSnRK2.7 and characterized its expression pattern under diverse environmental stresses and in various wheat tissues. Transgenic experiments indicated that TaSnRK2.7 significantly increased tolerance to drought, salt, and cold stress in Arabidopsis.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and water-stress experiments

Common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genotype ‘Hanxuan 10’ with a conspicuous drought-tolerant phenotype was used in this study. Wheat seedling growth conditions and stress treatment assays were performed as described previously (Mao et al., 2010). To study the expression of the target gene at different developmental stages, wheat seedling leaves and roots, spindle leaves at booting, and spikes at the heading stage were sampled. Seedlings were grown in a growth chamber (Mao et al., 2010), and spindle leaves at jointing and spikes were sampled from field plots without environmental stress.

To probe copy number of the target gene, four plant accessions, including hexaploid wheat cultivar ‘Hanxuan 10’ (AABBDD), and three diploid species, including Triticum urartu (AA, accession number 1010004), Aegilops speltoides (SS, putative B genome donor species, accession number IcAG 400046), and Aegilops tauschii (DD, accession number PH1878) were selected to perform Southern blot analysis.

Cloning the full-length TaSnRK2.7 cDNA and sequence analysis

Tissues from wheat seedlings at various stages and from mature plants were collected to extract total RNA with TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen). Based on the candidate expressed sequence tag of TaSnRK2.7 from the cDNA library established in our laboratory (Pang et al., 2007), the putative full-length TaSnRK2.7 cDNA was obtained by in silico cloning. To obtain full-length TaSnRK2.7 cDNA, a pair of primers (F: 5′-CCCAATCTTCGCCTCTGCC-3′, R: 5′-TTTATCCCCGGTCTGTGGCC-3′) were designed based on the lateral flanking sequence of the open reading frame (ORF) of the putative sequence.

Database searches of the nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences were performed through an NCBI/GenBank/Blast search. Sequence alignments and similarities with other species were determined by the megAlign program in DNAStar. The signal sequence was predicted with SignalP (http://genome.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP). The functional region and activity sites were identified using the PROSITE (http://expasy.hcuge.ch/sprot/prosite.html) and SMART motif search programs (http://coot.embl-heidelberg.de/SMART). To probe the relationship of TaSnRK2.7 and SnRK2 proteins from other plant species, the PHYLIP software package was used to construct a phylogenetic tree.

Southern blot analysis

Genomic DNA was separately digested overnight with restriction enzymes EcoRV, HindIII, and NcoI. The digested fragments were fractionated by electrophoresis on 0.8% agarose gels at 1.5 V cm−1 for 8–10 h, and then blotted to nylon membranes (Hybond N+; Amersham) overnight in 20× saline–sodium citrate (SSC). A fragment (800 bp) of the genome sequence of TaSnRK2.7 labelled with [α-32P]dCTP was used as the probe. After UV cross-linking, the blotted membrane was hybridized overnight at 65 °C in 50×Denhardt's solution. The membrane was sequentially washed with 2×SSC, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS); 0.2×SSC, 0.1% SDS, and 0.1×SSC, 0.1% SDS for 15 min at 65 °C. The hybridized blot was exposed to a phosphor screen (Kodak-K) at room temperature, and the signals were captured using the Molecular Imager FX System (Bio-Rad).

Subcellular localization of TaSnRK2.7 protein

The ORF of TaSnRK2.7 was fused upstream of the green fluorescent protein gene (GFP) under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter and NOS terminator in the pJIT163 expression vector. Proper restriction sites were added to the 5′- and 3′-ends of the coding region by the PCR method. F: 5′-GAGAGGTCTCAAGCTTATGGAGAGGTACGAGCTGCTCA-3′ (BsaI site in bold, HindIII site in bold italics), R: 5′-GAGAGGTCTCGGATCCGCCGCTGGCACGGACC-3′ (BsaI site in bold, BamHI site in bold italics). The PCR product obtained was digested with BsaI, and then ligated with the pJIT163-GFP plasmid cut with the corresponding enzyme to create recombinant plasmids for expressing the fusion protein. Positive plasmids were confirmed by endonuclease digest analysis, and then followed by sequencing. The recombinant constructs were transformed into living onion epidermal cells by particle bombardment with a GeneGun (BioRad Helios™) according to the instruction manual (helium pressure, 150–300 p.s.i.). After incubation in Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium at 28 °C for 36–48 h, the onion cells were observed with a laser scanning confocal microscope (Leika TCS-NT). The images obtained were recorded automatically. The recombinant constructs and the control pJIT163-GFP plasmid were bombarded into 20 onion epidermal segments.

Expression patterns of TaSnRK2.7

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) were used to determine the expression patterns of TaSnRK2.7 in wheat. A tubulin transcript was used to quantify the relative transcript levels. qRT-PCR was performed in triplicate with an ABI PRISM® 7000 system using the SYBR Green PCR master mix kit (Applied Biosystems). Specific primers (RT-PCR, F: 5′-CCCAATCTTCGCCTCTGCC-3′, R: 5′-TTTATCCCCGGTCTGTGGCC-3′; qRT-PCR, F: 5'-CGGGGAGAAGATAGACGAGAATG-3′; R: 5′- CTCAAAAAGCTCACCACCAGATG -3′) were designed according to the cDNA sequence. The relative level of gene expression was detected using the 2–ΔΔCT method (Livaka and Schmittgen, 2001). ΔΔCT = (CT, Target–CT, Tubulin)Time x– (CT, Target–CT, Tubulin)Time 0. The CT (cycle threshold) values for both the target and internal control genes were the means of the triplicate independent PCRs. Time x is any treated time point (1, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, or 72 h) and Time 0 represents the initial untreated time (0 h).

To detect the transcription level of TaSnRK2.7 in different organs, the expression of TaSnRK2.7 in seedling leaves was regarded as a standard because of its lowest expression, and the corresponding formula was modified as ΔΔCT = (CT, Target–CT, Tubulin)DST–(CT, Target–CT, Tubulin)SL. DST refers to the developmental stage tissue and SL, the seedling leaf. To identify the relative expression of TaSnRK2.7 in transgenic Arabidopsis, the actin transcript of Arabidopsis was used to quantify the expression levels, and the transgenic line with lowest expression was regarded as a standard.

Transgenic plant generation

The ORF of TaSnRK2.7 was amplified using primers 5′-GAGAGGTACCCCCAATCTTCGCCTCTGCC-3′ (KpnI site in bold italics) and 5′-GAGACTGCAGTTTATCCCCGGTCTGTGGCC-3′ (PstI site in bold italics), then inserted into the multiple cloning sites of the binary plasmid in a pPZP211 vector (Hajdukiewicz et al., 1994) as a GFP-fused fragment under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter and NOS terminator, yielding a p35S-TaSnRK2.7-GFP construct. The recombinant construct and the p35S-GFP vector were introduced into Agrobacterium, and then transferred into wild-type Arabidopsis (Columbia ecotype) plants by floral infiltration. Positive transgenic plants were first screened on kanamycin plates and then identified by RT-PCR and fluorescence detection of GFP.

Morphological characterization of transgenic Arabidopsis plants

Arabidopsis seed germination occurred on MS medium solidified with 0.8% agar and seedlings were cultured in a growth chamber. To examine root morphology, 3-d-old seedlings were grown on the surface of MS medium solidified with 1.0% agar, and the plates were placed vertically to facilitate primary root length measurement.

To characterize the morphology of stomata, seedling leaves of similar size were detached, and the epidermis was peeled off and immediately placed flat on a glass slide. Stomata at similar locations were observed and photographed using an Axioplan 2 microscope (Carl Zeiss). The width, length, and area of stomata in the photographed image were measured, and the ratios of stomata and leaf areas were recorded.

Features of TaSnRK2.7 seedlings under cold and hyperosmotic stress, and ABA application

Both wild-type and transgenic seeds were germinated on MS medium solidified with 0.8% agar. Seven-day-old seedlings were planted on MS medium containing 5% glycerol, 300 mM NaCl, or 5 μM ABA, and then cultured in growth chambers (22 °C, 70% humidity, 150 μM m−2 s−1, 12-h light/12-h dark cycle). For cold stress assays, seedlings planted on MS medium were cultured in a low-temperature growth chamber (4 °C, 70% humidity, 150 μM m−2 s−1, 12-h light/12-h dark cycle). Seedlings cultured on MS medium under normal growth conditions were used as control. Plates were placed vertically to keep the root tips pointing upwards. Green cotyledons (%) and biomass (g) were recorded. Ten plants of each line were collected as a sample for biomass measurement.

Abiotic stress tolerance assays

Seven-day-old seedlings were planted in a sieve-like plate containing mixed soil (vermiculite:humus 1:1) and cultured normally in the greenhouse. The plants were exposed to various stresses at designated time points. For drought tolerance assays, the seedlings were cultured in a greenhouse (22 °C, 70% humidity, 150 μM m−2s−1, 12-h light/12-h dark cycle) without watering until phenotypic differences were evident between transgenic plants and controls, and then rewatered. For salt stress assays, Arabidopsis seedlings were cultured as described above. Water was withheld for 3 weeks and then plants were well irrigated with NaCl solution (300 mM) applied from the bottom of the plates. For cold stress, the plants were transferred to a low-temperature growth chamber (4 °C) after culturing in a normal growth chamber for 1 week.

Measurement of total soluble sugars

Total soluble sugars were determined as fructose equivalents using the anthrone colorimetric assay (Yemm and Willis, 1954) at 620 nm with a spectrophotometer (LG-721; BioRad). After detaching from roots, 4-week-old plants were put into liquid nitrogen immediately and dehydrated in a refrigerated vacuum evaporator at 8.1 kPa air pressure and –60 °C for 24 h. After dehydration, samples were dried at 80 °C to a constant dry weight (DW). Extractions were performed with 0.1 g of dry material for each sample with three replications. Samples were boiled in 4 ml of double distilled water (ddH2O) for 4 min. After filtration the extracted filtrates were transferred to volumetric flasks (5 ml) and brought to 5 ml by addition of ddH2O.

Cell membrane stability

Plant cell membrane stability (CMS) was determined with a conductivity meter (DDS-1, YSI), CMS (%) = (1–initial electrical conductivity/electrical conductivity after boiling)×100. Twelve 7-d-old seedlings (grown on 1×MS medium, 0.8% agar) were placed on filter paper saturated with NaCl (300 mM) solution. When signs of stress began to appear on WT plants, seedlings were collected immediately and rinsed thoroughly with ddH2O before immersion in 20 ml of ddH2O at room temperature. Initial conductivities were recorded 2 h later, and then the samples were boiled for 30 min, cooled to room temperature, and final conductivities were measured.

Water retention ability

Water retention ability (WRA) was measured as follows: ten 4-week-old stressed plants of similar size in each line were detached from roots, immediately weighed (fresh weight, FW), then desiccated under controlled conditions (45–50% relative humidity and 25 °C) and weighed at designated time intervals (desiccated weight). Finally, the plants were oven-dried to a constant DW for 24 h at 80 °C. WRA was measured according to the formula: WRA (%) = (desiccated weight–DW)/(FW–DW)×100. Stress conditions were the same for salt tolerance assays in soil. WRA was measured 24 h later after high-salt stress.

Osmotic potential and free proline determination

Osmotic potential (OP) was measured with a Micro-Osmometer (Fiske® Model 210; Fiske Associates). Free proline was extracted and quantified from fresh tissues of well-watered seedlings (0.5 g) according to the method of Hu et al. (1992). Stress conditions were the same as for salt tolerance assays in soil. OP was measured before salt stress and after high-salt stress for 1 d. Free proline content was measured before stress and after high-salt stress for 1, 3, and 6 h.

Chlorophyll florescence assays

Chlorophyll florescence was measured with a portable photosynthesis system (LI-COR LI-6400 XTR), and the maximum efficiencies of photosystem II (PSII) photochemistry, Fv/Fm = (Fm–F0)/Fm, was employed to assess changes in the primary photochemical reactions of the photosynthetic potential. Plants were treated in the same way as for salt tolerance assays in soil. Chlorophyll florescence was measured before stress and after stress for 12, 24, and 36 h.

Stomatal conductance measurements

Stomatal conductance was measured with a steady-state diffusion leaf porometer (Model SC-1; Decagon). Similar-sized mature rosette leaves were selected for stomatal conductance determination and the area around the merging point of the leaf transverse midline and vein was chosen as the measuring region.

Results

Molecular characterization of TaSnRK2.7

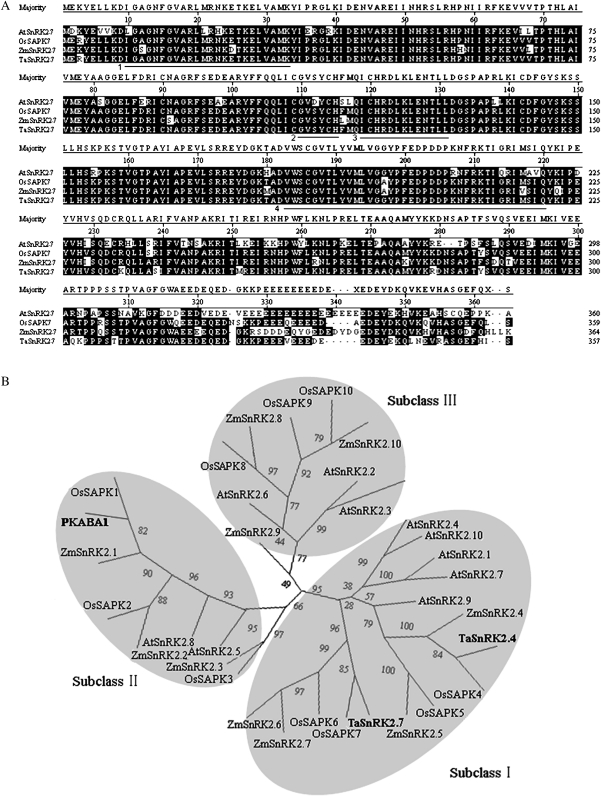

The TaSnRK2.7 cDNA was 1196 bp in length, including a 1074 bp ORF, a 73 bp 5′-untranslated region (UTR), and a 49 bp 3′ UTR. The ORF of TaSnRK2.7 encodes 357 deduced amino acid residues (AARs) with a calculated molecular mass of 42 kDa and a predicted pI of 5.47. Using a BLASTN search of the NCBI database, the deduced amino acid sequence showed homology with counterpart SnRK2 family members, namely, Oryza sativa, Zea mays, and Arabidopsis thaliana (Fig. 1A). TaSnRK2.7 has 94% identity to OsSAPK7 (NP_001052827), 87% to ZmSnRK2.7 (ACG50011), and 78% to AtSnRK2.7 (AAM65503). Scansite analysis indicated that TaSnRK2.7 has potential serine/threonine protein kinase activity, and like other SnRK2s, it has two domains in its N- and C-terminal regions. The N-terminal catalytic domain (4–260 AARs) is highly conserved, containing an ATP binding site (10–33 AARs) and protein kinase activating signature (119–131 AARs). Additionally, in the catalytic domain one potential N-myristoylation site GVsyCH (110–115 AARs) and one potential transmembrane-spanning region (183–220 AARs) were found. The relatively short C-terminal domain is abundant in Glu (E), and is predicted to be a coiled coil. Compelling evidence indicated that the C-terminal domain might have roles in kinase activation (Harmon et al., 1994; Harper et al., 1994; Huang et al., 1996), participation in protein–protein interactions mainly involved in ABA responsiveness, and possibly in ABA signal transmission (Kobayashi et al., 2004).

Fig. 1.

Sequence alignment of TaSnRK2.7 and SnRK2s from other plant species. (A) Alignment of the predicted amino acid sequences of TaSnRK2.7 and closely related plant SnRK2 protein kinases. Conserved prosite motifs are underlined. Regions 1–4 represent the ATP binding site, N-myristoylation site, protein kinase activating signature, and transmembrane-spanning region, respectively. Alignments were performed using the Megalign program of DNAStar. Common identical AARs are shown with a black background. Dashed lines represent gaps introduced to maximize alignment. Abbreviations on the left of each sequence: Ta, T. aestivum; Os, O. sativa; At, A. thaliana; Zm, Z. mays. (B) Phylogenetic tree of TaSnRK2.7 and SnRK2s from other plant species. Three distinct isoform groups are presented in grey. The phylogenetic tree was constructed with the PHYLIP 3.68 package; bootstrap values are in percentages.

Halford and Hardie et al. (1998) divided the SnRK2 family into two or three distinct subclasses based on functional divergence, namely SnRK2a (corresponding to subclass I and SnRK2b (corresponding to subclasses II and III). A phylogenetic tree was constructed with putative amino acid sequences of TaSnRK2.7, ZmSnRK2.7, and SnRK2 family members of rice and Arabidopsis. As shown in Fig. 1B, TaSnRK2.7 and its counterparts, OsSAPK7, ZmSnRK2.7, and AtSnRK2.7, were clustered in the same clade, subclass I.

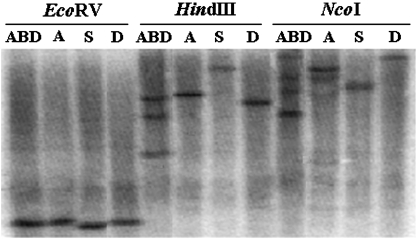

Determination of gene copy number

To study the genomic organization and copy number of TaSnRK2.7 in common wheat and its genome donor species, Southern blot analysis was performed using an 800-bp genomic fragment of TaSnRK2.7 as a probe (Fig. 2). In the lanes digested with EcoRV, only one hybridized band was present, whereas in the lanes digested with HindIII and NcoI, three hybridization bands were evident in hexaploid wheat and one in diploids. The appearance of some minor bands in the Chinese Spring (ABD) and T. urartu (A) genome (NcoI-digested) might be TaSnRK2.7 homologues in wheat. The results indicated that one copy of TaSnRK2.7 might exist in each of the three genomes of common wheat.

Fig. 2.

Southern blotting analysis of genomic DNA from common wheat and related diploid species digested with three restriction enzymes. Fragments were separated in a 0.8% agarose gel, blotted onto nylon membranes, and hybridized with the [α-32P]dCTP-labelled probe generated from the genomic sequence of TaSnRK2.7. ABD, Chinese spring; A, T. urartu; S, A. speltoides; D, A. tauschii.

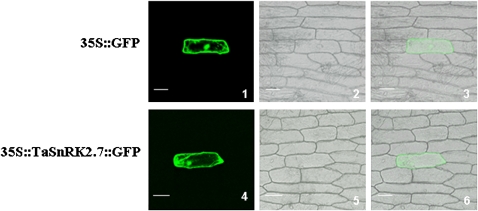

Subcelluar localization of the TaSnRK2.7 protein

The deduced amino acid sequence contains a putative N-myristoylation site and a transmembrane region, suggesting that TaSnRK2.7 might interact with the cell membrane and nuclear system. To address the subcellular localization of TaSnRK2.7 in living cells, a construct containing TaSnRK2.7 fused in-frame with GFP (TaSnRK2.7::GFP) driven by the CaMV 35S promoter was transiently expressed in living onion epidermal cells. As predicted, TaSnRK2.7–GFP was present in the cell membrane, cytoplasm, and nucleus (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Subcellular localization of TaSnRK2.7 in onion epidermal cells. Cells were bombarded with constructs carrying GFP or TaSnRK2.7–GFP as described in Materials and methods. GFP and TaSnRK2.7–GFP fusion proteins were transiently expressed under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter in onion epidermal cells and observed with a laser scanning confocal microscope. Images were taken in dark field for green fluorescence (1, 4), cell outline (2, 5), and the combination (3, 6) were photographed in bright field. Scale bar = 100 μm. Each construct was bombarded into at least 30 onion epidermal cells. (This figure is available in colour at JXB online.)

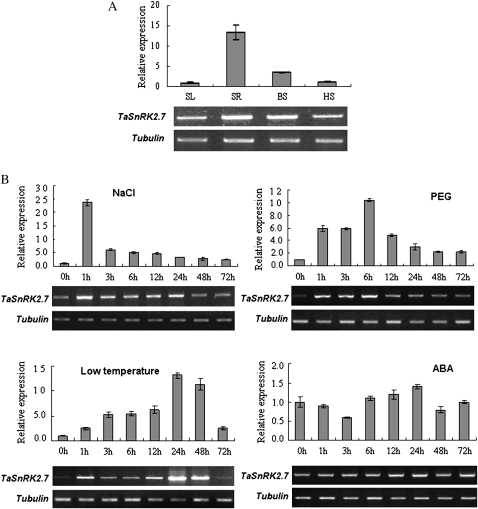

Expression patterns of TaSnRK2.7 in wheat

The expression patterns of TaSnRK2.7 in wheat were identified by both semi-qRT-PCR and qRT-PCR methods. As shown in Fig. 4A, TaSnRK2.7 was expressed strongly in seedling roots, weakly in booting spindles, and marginally in seedling leaves and heading spikes. Various expression patterns occurred under different stresses (Fig. 4B). The expression levels of TaSnRK2.7 increased significantly under salt, polyethylene glycol (PEG), and cold stress conditions, but were not activated by ABA. However, expression patterns differed significantly for NaCl and PEG stresses, the transcription levels increased rapidly and peaked at 1 and 6 h, respectively, and then decreased. For cold stress, the expression level increased gradually and reached its maximum at 24 h.

Fig. 4.

Expression patterns of TaSnRK2.7 in various tissues and in response to various treatments. (A) Expression patterns of TaSnRK2.7 in wheat tissues at different developmental stages. SL, seedling leaf; SR, seedling root; BS, booting spindle; HS, heading spike. (B) Expression patterns of TaSnRK2.7 under various stress conditions. The 2–ΔΔCT method was used to measure the relative expression level of the target gene. The expression of TaSnRK2.7 in seedling leaves or at 0 h was regarded as standard, and other values were compared with it. The experiments were performed in triplicate. Values are means of three samples±SE. Gels: upper, TaSnRK2.7-specific fragments amplified by semi-qRT-PCR; lower, tubulin fragments amplified by semi-qRT-PCR as internal control.

Morphological characteristics of TaSnRK2.7-overexpressing Arabidopsis under normal conditions

Transgenic plants were first screened on kanamycin plates, and then re-identified by detecting fluorescence of GFP and RT-PCR (Fig. S1A, B). Six transgenic lines were randomly selected to detect gene expression levels. As shown in Fig. S1C, expression levels of TaSnRK2.7 in different transgenic lines varied significantly.

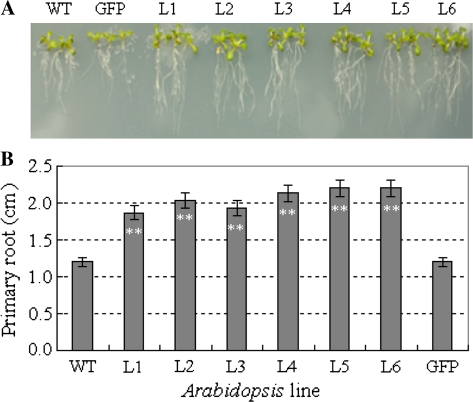

To evaluate the applicability of TaSnRK2.7 in transgenic breeding for abiotic stresses, the phenotypes of TaSnRK2.7 Arabidopsis were characterized at different developmental stages. Morphological assays indicated no evident difference in seed germination rate, seedling size, and seed production between transgenic and WT plants (Fig. S2). However, the primary roots of transgenic Arabidopsis were longer, and the numbers of lateral roots were greater than those of the GFP and WT controls (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of root morphology between TaSnRK2.7 lines and controls on MS medium. (This figure is available in colour at JXB online.)

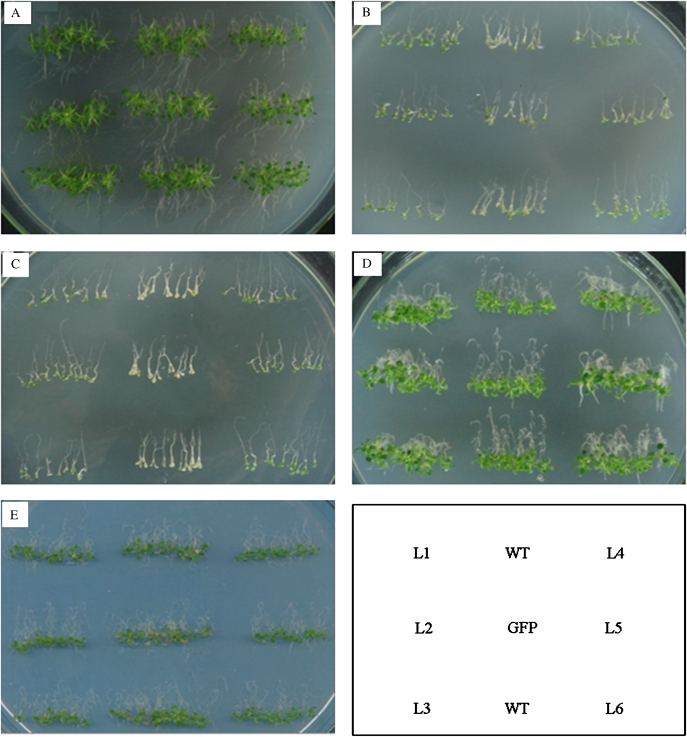

TaSnRK2.7 plants exhibit enhanced multi-abiotic stress tolerance at the seedling stage

An appropriate OP is vital to normal growth of plants and directly affects the water uptake of roots. The primary roots of Arabidopsis, like most plants, are positively gravitropic and sensitive to osmotic stress; therefore, gravitropic growth is an effective indicator of plant vigour under stress conditions. Under normal conditions there was no phenotypic difference between TaSnRK2.7 plants and controls (Fig. 6A). Under severe osmotic stress TaSnRK2.7 plants grew slowly, and roots of some plants began to grow downwards, whereas all the WT and GFP plants stopped growing, and most of the control plants began to bleach and died within 1 week (Fig. 6B, C). Under cold stress, TaSnRK2.7 plants were much more vigorous than the controls. As shown in Fig. 6D, the roots of TaSnRK2.7 plants grew downwards earlier and were bigger than the controls. Statistical analysis of green cotyledons and biomass showed that the green cotyledons (%) and FW of TaSnRK2.7 seedlings were significantly higher than those of the controls under stress (except the green cotyledons under cold stress) (Table 1). For ABA treatment, no phenotypic or statistical difference was evident between TaSnRK2.7 plants and controls (Fig. 6E).

Fig. 6.

TaSnRK2.7 seedlings exhibit enhanced abiotic stress tolerance on MS medium. Seven-day-old seedlings planted on MS medium containing 5% glycerol, 300 mM NaCl or cultured at 4 °C, were cultured vertically until evident differences appeared between the TaSnRK2.7 transformants and controls. (A) Control seedlings planted on MS medium for 1 week without stress. (B) Seedlings treated with 5% glycerol. (C) Seedlings treated with 300 mM NaCl. (D) Seedlings cultured at 4 °C. (E) Seedlings treated with 5 μM ABA. (This figure is available in colour at JXB online.)

Table 1.

Comparison of green cotyledons and biomass between TaSnRK2.7 lines and WT controls on MS medium with different treatments

| Treatment | WT | L1 | L2 | L3 | L4 | L5 | L6 | GFP | ||||||||

| GC | FW | GC | FW | GC | FW | GC | FW | GC | FW | GC | FW | GC | FW | GC | FW | |

| CK | 100 | 0.150 | 100 | 0.150 | 100 | 0.160 | 100 | 0.157 | 100 | 0.147 | 100 | 0.150 | 100 | 0.140 | 100 | 0.153 |

| 5% glycerol | 26 | 0.030 | 97** | 0.044* | 93** | 0.041* | 90** | 0.039* | 87** | 0.040* | 90** | 0.042* | 97** | 0.044* | 27 | 0.029 |

| 300 mM NaCl | 0 | 0.213 | 77** | 0.035* | 73** | 0.036* | 67** | 0.032* | 83** | 0.035* | 73** | 0.034* | 87** | 0.036* | 0 | 0.020 |

| 4 °C | 100 | 0.073 | 100 | 0.107** | 100 | 0.123** | 100 | 0.137** | 100 | 0.103** | 100 | 0.123** | 100 | 0.113** | 100 | 0.073 |

| 5 μM ABA | 77 | 0.065 | 77 | 0.067 | 77 | 0.067 | 77 | 0.066 | 77 | 0.069 | 77 | 0.064 | 73 | 0.065 | 77 | 0.067 |

Statistical analysis of green cotyledons and biomass showed that green cotyledons and FW of TaSnRK2.7 seedlings were significantly higher than WT controls under stress (except the green cotyledons under cold). No difference was detected following ABA application.

CK, control seedlings planted on MS medium for 1 week without stress; GC, green cotyledons (%). Experiments were performed in triplicate. Values are mean±SE, n=10.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01: significant difference between TaSnRK2.7 lines and WT controls with F-test.

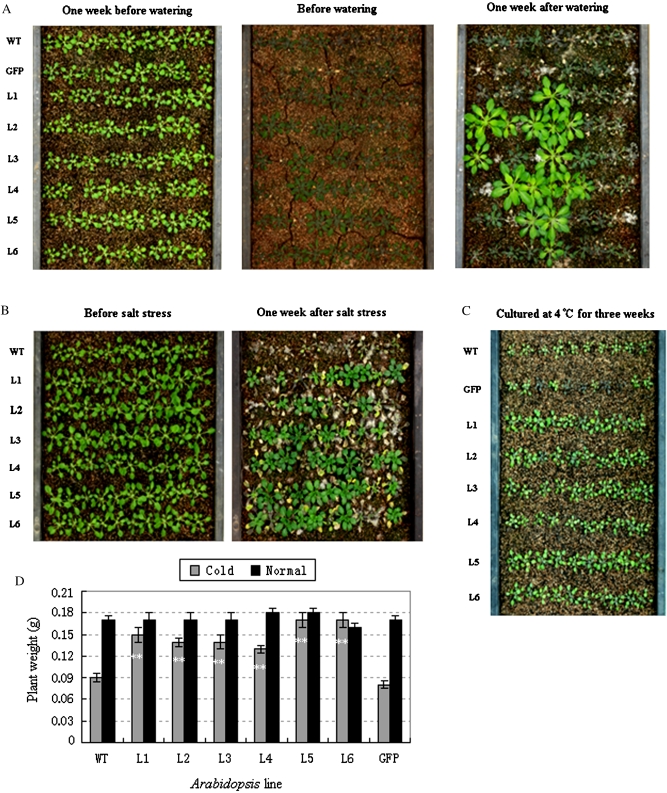

TaSnRK2.7 plants have pronounced abiotic stress tolerance in soil

To simulate field conditions TaSnRK2.7 lines and controls were planted in a sieve-like plate. Two weeks after drought stress induced by withholding water, the lower rosette leaves of WT and GFP plants wilted severely, and approximately half the leaves of controls became darker or died, whereas only some of the TaSnRK2.7 plants wilted slightly. After rewatering for 1 week, all the controls were dead, whereas 10–60% of TaSnRK2.7 plants survived (Fig. 7A). In salt stress treatments, the leaf tips of all lines began to crimple within 24 h, and 1 week later signs of salt stress were evident. TaSnRK2.7 transformants were clearly more vigorous than the controls (Fig. 7B). For cold stress analysis, all plants were planted in soil and cultured at 4 °C. Three weeks later differences in seedling size were evident and all the TaSnRK2.7 plants were bigger than the controls. The biomasses of TaSnRK2.7 plants were significantly higher than those of the controls (P<0.01) (Fig. 7C, D).

Fig. 7.

Stress tolerance assays of TaSnRK2.7-overexpressing transgenic Arabidopsis. (A) TaSnRK2.7 transgenic plants and controls grown under drought stress. (B) TaSnRK2.7 transgenic plants and controls treated with 300 mM NaCl. (C) TaSnRK2.7 transgenic plants and controls cultured at 4 °C. (D) Biomass of transgenic plants and controls after cold stress. Values are mean±SE, n=10. ** Significantly different from the controls at P<0.01. (This figure is available in colour at JXB online.)

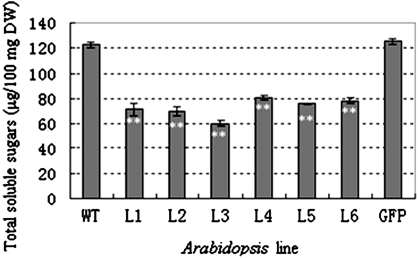

TaSnRK2.7 is involved in the carbohydrate metabolism

To investigate the role of TaSnRK2.7 in carbohydrate metabolism, total soluble sugars of TaSnRK2.7 plants were determined and the results revealed that total soluble carbohydrates in transgenic lines was significantly lower than the WT and GFP controls under well-watered conditions (P<0.01) (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Overexpression of TaSnRK2.7 leads to significantly decreased total water-soluble sugars in Arabidopsis. Values are mean±SE, n=10. ** Significantly different from the controls at P<0.01.

Physiological characterization of transgenic plants

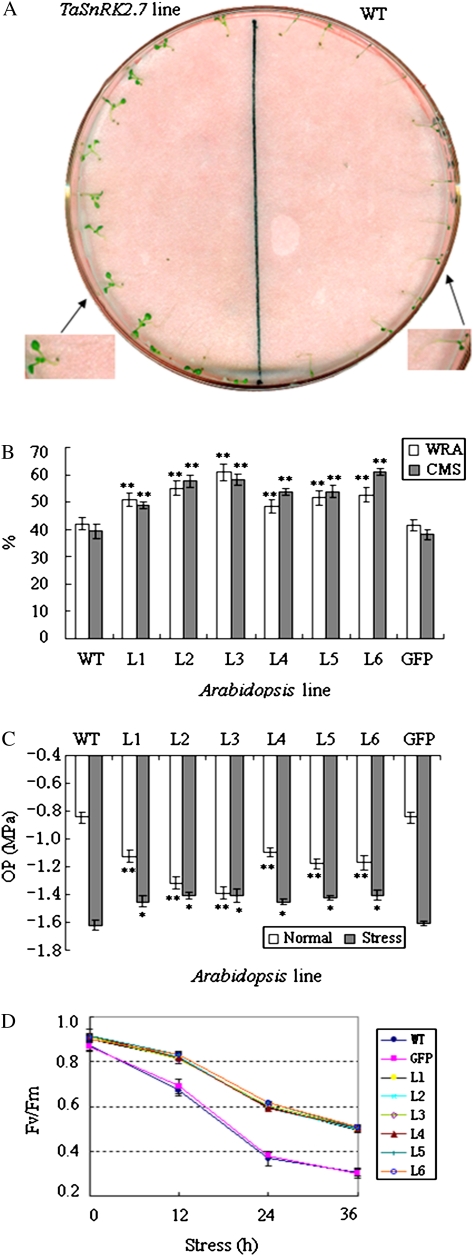

Four physiological traits related to plant stress tolerance, including CMS, WRA, OP and free proline, were analysed. To identify the cell membrane stability (CMS) of TaSnRK2.7-overexpressing Arabidopsis under stress, 7-d-old seedlings were treated with NaCl (300 mM) solution on filter paper. Symptoms of salt stress began to appear on WT and GFP plants 5 h after NaCl treatment, but no signs of stress were evident on TaSnRK2.7 plants (Fig. 9A). CMS levels in transgenic lines were significantly higher than in the two controls (P<0.01), strongly indicating that overexpression of TaSnRK2.7 increased CMS of Arabidopsis under salt stress (Fig. 9B).

Fig. 9.

Physiological characterization of TaSnRK2.7 plants. (A) Seedling phenotypes of TaSnRK2.7-overexpressing lines and WT under salinity stress for 5 h. (B) Comparison of CMS and WRA of transgenic plants and controls under stress. (C) TaSnRK2.7 plants had significantly lower OP than WT and GFP controls under normal conditions. One day after treatment with 300 mM NaCl, OP in WT and GFP controls had decreased more rapidly and was significantly lower than in TaSnRK2.7 plants. (D) Changes in variable to maximum fluorescence ratios (Fv/Fm) in TaSnRK2.7 plants and WT and GFP controls subjected to high salt stress. L1–L6, six individual TaSnRK2.7 transgenic lines; WT, wild type; GFP, GFP transgenic line. Values are mean±SE, n=10. * Significant difference between TaSnRK2.7-overexpressing lines and controls with F-test (*P<0.05, **P<0.01). (This figure is available in colour at JXB online.)

To assess WRA of TaSnRK2.7-overexpressing Arabidopsis under stress, six transgenic lines were selected to perform a 7-h detached-rosette water loss rate assay. Compared with plants, The six transgenic lines showed higher WRA than the WT and GFP control plants (P<0.01) (Fig. 9B).

To maintain a stable intracellular environment in the presence of external environmental stress many plants decrease their cellular OPs through accumulation of intracellular organic osmolytes such as proline, glycine betaine, mannitol, and trehalose (Wang et al., 2007; Zhu, 2002). OP analysis results showed that TaSnRK2.7 plants had significantly lower OP than WT and GFP (P<0.01) under normal conditions, and no OP difference was detected between WT and GFP controls (Fig. 9C). The leaf tips of WT and GFP controls began to crimple 1 d after salt stress (300 mM NaCl), whereas no phenotypic change was evident on TaSnRK2.7 plants. The OP of the two control plants decreased more rapidly than TaSnRK2.7 plants under high-salt stress conditions whereas TaSnRK2.7 plants retained a relatively steady OP (Fig. 9C).

Compelling evidence indicates that free proline plays an important role in addressing osmotic stress, including scavenging of free radicals, stabilizing subcellular structures, buffering cellular redox, and decreasing OP (Bartels and Sunkar, 2005). In the present study, there was no difference in free proline content between WT and transgenic plants under normal or stress conditions (data not shown).

Photochemical efficiency of PSII (Fv/Fm) was also measured. As shown in Fig. 9D, under normal conditions chlorophyll fluorescence of TaSnRK2.7 plants was slightly higher than the two controls, but did not reach a significant level (P>0.05). After NaCl treatment WT and GFP plants showed more significant drops in the Fv/Fm than TaSnRK2.7 plants. These data clearly show that TaSnRK2.7 plants might have more robust photochemical efficiency.

Discussion

Protein phosphorylation is one of the central signalling events occurring in response to environmental stress in plants (Ichimura et al., 2000). In this study, we identified an osmotic-stress-activated protein kinase gene, TaSnRK2.7, in common wheat. N-terminal myristoylation and transmembrane-spanning regions are essential for protein function in mediating membrane associations and protein–protein interactions in plant responses to environmental stress (Podel and Gribstov, 2004; Ishitani et al., 2000). In our research, an N-terminal myristoylation and one potential transmembrane-spanning region were identified. In plants these might be involved in interaction of proteins and participate in response to abiotic stress. In yeast, SNF1 kinase was localized to the nucleus, vacuole, and cytoplasm (Vincent et al., 2001), and involved in signal transduction pathways by interacting with RNA polymerase II holoenzyme to activate transcription of glucose-responsive genes (Kuchin et al., 2000). The presence of TaSnRK2.7 in the cell membrane, cytoplasm, and nucleus in the present study suggested that TaSnRK2.7 might have different functions in wheat. More effort should be made to determine the signal transduction pathway and detailed location of this enzyme to facilitate an understanding of adaptive cellular mechanisms in stressed plants.

In Arabidopsis, AtSRK2.8/AtSRK2C was identified as a root-specific protein kinase, and AtSRK2.6/AtSRK2E/OST1 was confirmed to play a pivotal role in stomatal closure in leaves, suggesting that different SnRK2 members have different roles in different tissues (Mustilli et al., 2002; Umezawa et al., 2004). Mao et al. (2010) showed TaSnRK2.4 strongly expressed in booting spindles. Our evidence showed that TaSnRK2.7 was expressed highly in seedling roots, suggesting that it might act as a fundamental signalling molecule of water and/or nutrient status in soil (Fig. 4A).

Numerous studies demonstrate that the SnRK2 family is involved in response to multi-environmental stress (Kobayashi et al., 2004; Huai et al., 2008). During the study, we detected dynamic expression of TaSnRK2.7 under PEG, salt, and cold stress (Fig. 4B), suggesting that TaSnRK2.7 is involved in the cross-talk of multi-environmental stress responses. Significant differences in expression level and diverse response times indicated that TaSnRK2.7 was very sensitive to NaCl and PEG stresses, but not activated by ABA application. To extend our understanding of the exact functions of TaSnRK2.7, further effort should be directed at deciphering the biological role and function of TaSnRK2.7 in non-ABA-dependent signal transduction pathways.

To investigate the in vivo role of TaSnRK2.7 in plants under abiotic resistance, fused TaSnRK2.7–GFP was overexpressed in Arabidopsis. Growth retardation often occurs in transgenic plants and severely restricts the utilization potential of target genes in plant breeding. To assess the feasibility of TaSnRK2.7 in transgenic breeding, morphological traits were closely monitored throughout the entire growth period. The results clearly demonstrated that TaSnRK2.7 overexpression does not retard plant growth, but it does improve development of the root system, which should benefit the uptake of water and nutrients under osmotic stress (Fig. 5).

Growing evidence indicated that genes included in SnRK2 subclasses II and III may be related to seed germination and/or ABA-regulated stomatal closure (Li et al., 2000; Boudsocq et al., 2007; Nakashima et al., 2009). In a recent study TaSnRK2.4, included in subclass I was activated by ABA and involved in seed development and dormancy (Mao et al., 2010). Here, no difference was observed in TaSnRK2.7 seed germination (Fig. S2). In addition, we measured the width, length, area, and density of stomata, as well as the stomatal conductance of fully expanded leaves under normal conditions, and no evident difference was identified (data not shown), showing that TaSnRK2.7 might not participate in regulation of stomatal development, aperture, and response to exogenous ABA.

It was reported that SnRK1s may have roles in regulating energy metabolism, similar to the roles of yeast SNF1 kinase and mammalian AMPK (Hardie et al., 1998; Halford and Hey, 2009). Zhang et al. (2001) reported that the absence of barley SnRK1 expression led to abnormal development of pollen and lack of starch accumulation. One embryo-expressed SnRK1 of wheat was involved in regulation of α-amylase in starch accumulation (Laurie et al., 2003). Maria Felix et al. (2009) demonstrated that silencing of SnRK1s led to increased sucrose levels in transgenic sugar cane. However, there are few reports on SnRK2 function in carbohydrate metabolism. In the present study, we clearly showed that overexpression of TaSnRK2.7 led to significantly decreased total soluble sugar content in Arabidopsis (Fig. 8), suggesting that TaSnRK2.7 might be involved in the metabolism of carbohydrate, similar to SnRK1 members. In future research, it will be necessary to gain an understanding of the signals and molecular roles of TaSnRK2.7 in carbohydrate metabolism.

Environmental stresses often cause physiological changes in plants. Physiological indices, including OP, CMS, and WRA, are typical physiological parameters for evaluating abiotic stress tolerance and resistance in crop plants (Dhanda and Sethi, 1998; Farooq and Azam, 2006). In general, plants with lower OP and higher CMS and WRA have enhanced tolerance or resistance to environmental stresses. Under hyperosmotic stress, enhanced osmolytes leading to lower OP in plant cells was suggested as an adaptive mechanism for maintenance of turgor (Wang et al., 2007; Zhu, 2002). In our work, the OP of TaSnRK2.7 seedlings were significantly lower than those of WT and GFP plants under normal growing conditions, but TaSnRK2.7 plants retained higher and steady OP levels compared with the two controls under salt-stress conditions, hinting that TaSnRK2.7 might be involved in the regulation of OP in Arabidopsis (Fig. 9C).

It is well documented that proline is the most widely distributed multifunctional osmolyte occurring in many organisms and playing important roles in enhancing osmotic stress tolerance (Kumar et al., 2003; Claussen, 2005). An increase in free proline was not detected in TaSnRK2.7 plants under normal and stress conditions, suggesting that proline might not be the reason for osmolyte augmentation. Soluble sugar is an important resource of osmolytes. Our data showed that TaSnRK2.7 plants had significantly lower total soluble sugar content than controls under well-watered conditions (Fig. 8), but this was inconsistent with OP determination results, hinting that total soluble sugar content was also not the cause of osmolyte augmentation either. Ongoing research is attempting to dissect the actual molecular mechanisms of decreased OP in TaSnRK2.7 plants. Chlorophyll fluorescence is a reliable, non-invasive method for monitoring photosynthetic events and reflects the physiological status of plants (Strasser et al., 2002). The ratio of variable to maximal fluorescence is an important parameter used to assess the physiological status of the photosynthetic apparatus; it represents the maximum quantum yield of the primary photochemical reaction of PS II. Environmental stresses that affect PS II efficiency are known to provoke decreases in Fv/Fm ratio (Krause and Weis, 1991). In this research, the Fv/Fm ratios of WT and GFP plants fell much more quickly than TaSnRK2.7 plants under salt stress (Fig. 9D), suggesting that TaSnRK2.7 plants had more robust photosynthetic capabilities than the controls.

Stress tolerance analysis of transgenic TaSnRK2.7 and control seedlings planted on MS medium and in soil demonstrated that the transgenic plants had acquired strengthened tolerance to severe drought, salt, and cold stress. Our understanding is that enhanced multi-stress tolerance is possibly due to decreased OP and enhanced root growth. An improved root system of TaSnRK2.7 plants might absorb water more effectively than WT controls under water-deficit conditions. Decreased OP means more osmolytes in plant sap, which possibly facilitates water retention, maintaining regular cell turgor, and avoiding damage to cell membranes, thus enhancing drought tolerance. Under salt stress, lower OP probably prevents entry of harmful ions, e.g. Na+ and Cl−, and reduces cell water loss, thereby helping to retain a steady OP under salt stress conditions (Fig. 9C), thus relieving ion damage to cell membranes, maintaining cell turgor, and therefore increasing salt tolerance. Under cold stress, lower OP generally means more solutes in the plant sap, resulting in lower freezing points and hence reduced cold damage. In agreement with the expression patterns, no morphological difference was identified between TaSnRK2.7 lines and controls after ABA treatment, indicating that TaSnRK2.7 does not participate in the response to ABA.

This study primarily concerned the morphological and physiological features of TaSnRK2.7 overexpression in Arabidopsis under normal and adverse conditions. It was proposed that overexpression of TaSnRK2.7 leads to enhanced plant tolerance to stresses mainly through increased osmolytes, enhanced photosynthetic capability, and strengthened seedling roots.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Figure S1. Identification of TaSnRK2.7 transformed Arabidopsis plants. (A) Determination of green fluorescence in roots of transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Assays were performed at the seedling stage with a laser-scanning confocal microscope. Images were taken in dark field for green fluorescence, and the root outline and combination are in bright field. (B) RT-PCR analysis of transgenic plants. M: 200-bp ladder; lanes 1–9: p35S-TaSnRK2.7-GFP-NOS transformed plants; lane 10: wild-type Arabidopsis (negative control); lane 11: p35S-GFP-NOS transformed plant (negative control); lane 12: p35S-TaSnRK2.7-GFP-NOS plasmid DNA (positive control). (C) Expression levels of TaSnRK2.7 in transgenic Arabidopsis lines L1–L6. The lowest expression of TaSnRK2.7 in L4 was regarded as standard.

Figure S2. Morphological characterization of TaSnRK2.7 plants. (A) Comparison of seed germination and seedlings between TaSnRK2.7 transformants and controls grown on MS medium. (B) Phenotypes of mature transgenic lines and WT grown in soil (4 weeks). (C) Grain yields of TaSnRK2.7 and WT plants. The seeds of transgenic TaSnRK2.7 and WT plants cultured under well-watered conditions were harvested separately. The grain yield of each plant was measured after dehydration, and there were no significant differences. L1–L6, six individual TaSnRK2.7 transgenic lines; WT, wild type; GFP, GFP transgenic line. Values are mean±SE, n=10.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor Zhensheng Li (Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing) for providing the pJIT163-GFP expression vector. We thank Robert A. McIntosh (Plant Breeding Institute, University of Sydney, NSW, Australia) for critical reading of, and comments on, the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Key Technologies R&D Program (2009ZX08002-012B).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AAR

amino acid residue

- ABA

abscisic acid

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- CDPK

calcium-dependent protein kinase

- CMS

cell membrane stability

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- OP

osmotic potential

- ORF

open reading frame

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real-time PCR

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

- WRA

water retention ability

- SNF

sucrose non-fermenting

- SnRK

SNF1-related protein kinase

- WT

wild type

References

- Anderberg RJ, Walker-Simmons MK. Isolation of a wheat cDNA clone for an abscisic acid-inducible transcript with homology to protein kinases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 1992;89:10183–10187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels D, Sunkar R. Drought and salt tolerance in plants. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences. 2005;24:23–58. [Google Scholar]

- Boudsocq M, Droillard MJ, Barbier-Brygoo H, Lauriere C. Different phosphorylation mechanisms are involved in the activation of sucrose non-fermenting 1 related protein kinases 2 by osmotic stresses and abscisic acid. Plant Molecular Biology. 2007;63:491–503. doi: 10.1007/s11103-006-9103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P. Protein phosphorylation and hormone action. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B—Biological Sciences. 1988;234:115–144. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1988.0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claussen W. Proline as a measure of stress in tomato plants. Plant Science. 2005;168:241–248. [Google Scholar]

- Dhanda SS, Sethi GS. Inheritance of excised-leaf water loss and relative water content in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) Euphytica. 1998;104:39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Diedhiou CJ, Popova OV, Dietz KJ, Golldack D. The SNF1-type serine-threonine protein kinase SAPK4 regulates stress-responsive gene expression in rice. BMC Plant Biology. 2008;8:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-8-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooq S, Azam F. The use of cell membrane stability (CMS) technique to screen for salt tolerant wheat varieties. Plant Physiology. 2006;163:629–637. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Cadenas A, Verhey SD, Holappa LD, Shen Q, Ho TH, Walker-Simmons MK. An abscisic acid-induced protein kinase, PKABA1, mediates abscisic acid-suppressed gene expression in barley aleurone layers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 1999;96:1767–1772. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Xiong L, Song CP, Gong D, Halfter U, Zhu JK. A calcium sensor and its interacting protein kinase are global regulators of abscisic acid signaling in Arabidopsis. Developmental Cell. 2002;3:233–244. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00229-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajdukiewicz P, Svab Z, Maliga P. The small, versatile pPZP family of Agrobacterium binary vectors for plant transformation. Plant Molecular Biology. 1994;25:989–994. doi: 10.1007/BF00014672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halford NG, Hardie DG. SNF1-related protein kinases: global regulators of carbon metabolism? Plant Molecular Biology. 1998;37:735–748. doi: 10.1023/a:1006024231305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halford NG, Hey SJ. Snf1-related protein kinases (SnRKs) act within an intricate network that links metabolic and stress signalling in plants. Biochemical Journal. 2009;419:247–259. doi: 10.1042/BJ20082408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfter U, Ishitani M, Zhu JK. The Arabidopsis SOS2 protein kinase physically interacts with and is activated by the calcium-binding protein, SOS3. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2000;97:3535–3540. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040577697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie DG, Carling D, Carlson M. The AMP-activated/SNF1 protein kinase subfamily: metabolic sensors of the eukaryotic cell? Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1998;67:821–855. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon AC, Yoo BC, McCaffery C. Pseudosubstrate inhibition of CDPK, a protein kinase with a calmodulin-like domain. Biochemistry. 1994;33:7278–7287. doi: 10.1021/bi00189a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper JF, Huang JF, Lloyd SJ. Genetic identification of an autoinhibitor in CDPK, a protein kinase with a calmodulin-like domain. Biochemistry. 1994;33:7267–7277. doi: 10.1021/bi00189a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirt H. Multiple roles of MAP kinases in plant signal transduction. Trends in Plant Science. 1997;2:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hrabak EM, Chan CW, Gribskov M, et al. The Arabidopsis CDPK-SnRK superfamily of protein kinases. Plant Physiology. 2003;132:666–680. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.011999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu CA, Delauney AJ, Verma DP. A bifunctional enzyme (delta 1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase) catalyzes the first two steps in proline biosynthesis in plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 1992;89:9354–9358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.19.9354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huai J, Wang M, He J, Zheng J, Dong Z, Lv H, Zhao J, Wang G. Cloning and characterization of the SnRK2 gene family from Zea mays. Plant Cell Reports. 2008;27:1861–1868. doi: 10.1007/s00299-008-0608-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JF, Teyton L, Harper JF. Activation of a Ca(2+)-dependent protein kinase involves intramolecular binding of a calmodulin-like regulatory domain. Biochemistry. 1996;35:13222–13230. doi: 10.1021/bi960498a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichimura K, Mizoguchi T, Yoshida R, Yuasa T, Shinozaki K. Various abiotic stresses rapidly activate Arabidopsis MAP kinases ATMPK4 and ATMPK6. The Plant Journal. 2000;24:655–665. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishitani M, Liu JP, Halfter U, Kim CS, Shi WM, Zhu JK. SOS3 function in plant salt tolerance requires N-myristoylation and calcium binding. The Plant Cell. 2000;12:1667–1677. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.9.1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KN, Cheong YH, Grant JJ, Pandey GK, Luan S. CIPK3, a calcium sensor-associated protein kinase that regulates abscisic acid and cold signal transduction in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell. 2003;15:411–423. doi: 10.1105/tpc.006858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause GH, Weis E. Chlorophyll fluorescence and photosynthesis: the basics. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology. 1991;42:313–349. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi Y, Yamamoto S, Minami H, Kagaya Y, Hattori T. Differential activation of the rice sucrose nonfermenting1-related protein kinase2 family by hyperosmotic stress and abscisic acid. The Plant Cell. 2004;16:1163–1177. doi: 10.1105/tpc.019943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchin S, Treich I, Carlson M. A regulatory shortcut between the Snf1 protein kinase and RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2000;97:7916–7920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.140109897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar SG, Reddy AM, Sudhakar C. NaCl effects on proline metabolism in two high yielding genotypes of mulberry (Morus alba L.) with contrasting salt tolerance. Plant Science. 2003;165:1245–1251. [Google Scholar]

- Laurie S, McKibbin RS, Halford NG. Antisense SNF1-related (SnRK1) protein kinase gene represses transient activity of an alpha-amylase (alpha-Amy2) gene promoter in cultured wheat embryos. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2003;54:739–747. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erg085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Wang XQ, Watson MB, Assmann SM. Regulation of abscisic acid-induced stomatal closure and anion channels by guard cell AAPK kinase. Science. 2000;287:300–303. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5451.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Ishitani M, Halfter U, Kim CS, Zhu JK. The Arabidopsis thaliana SOS2 gene encodes a protein kinase that is required for salt tolerance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2000;97:3730–3734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060034197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livaka KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C (T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao XG, Zhang HY, Tian SJ, Chang XP, Xie HM, Jing RL. TaSnRK2.4, a SNF1-type serine-threonine protein kinase of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) confers enhanced multi-stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2010;61:683–696. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maria Felix Jde, Papini-Terzi FS, Rocha FR, et al. Expression profile of signal transduction components in a sugarcane population segregating for sugar content. Tropical Plant Biology. 2009;2:98–109. [Google Scholar]

- Mustilli AC, Merlot S, Vavasseur A, Fenzi F, Giraudat J. Arabidopsis OST1 protein kinase mediates the regulation of stomatal aperture by abscisic acid and acts upstream of reactive oxygen species production. The Plant Cell. 2002;14:3089–3099. doi: 10.1105/tpc.007906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima K, Fujita Y, Kanamori N, et al. Three Arabidopsis SnRK2 protein kinases, SRK2D/SnRK2.2, SRK2E/SnRK2.6/OST1 and SRK2I/SnRK2.3, involved in ABA signaling are essential for the control of seed development and dormancy. Plant Cell Physiology. 2009;50:1345–1363. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta M, Guo Y, Halfter U, Zhu JK. A novel domain in the protein kinase SOS2 mediates interaction with the protein phosphatase 2C ABI2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2003;100:11771–11776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2034853100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang XB, Mao XG, Jing RL, Shi JF, Gao T, Chang XP, Li YF. Analysis of gene expression profile response to water stress in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seedling. Acta Agronomica Sinica. 2007;33:333–336. [Google Scholar]

- Park YS, Hong SW, Oh SA, Kwak JM, Lee HH, Nam HG. Two putative protein kinases from Arabidopsis thaliana contain highly acidic domains. Plant Molecular Biology. 1993;22:615–624. doi: 10.1007/BF00047402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podel S, Gribskov M. Predicting N-terminal myristoylation sites in plant proteins. BMC Genomics. 2004;5:37–51. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-5-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser A, Srivastava A, Tsimilli-Michael M. The fluorescence transient as a tool to characterize and screen photosynthetic samples. In: Mohanty P, Yunus U, Pathre M, editors. Probing Photosynthesis: Mechanism, Regulation and Adaptation. London: Taylor and Francis; 2002. pp. 443–480. [Google Scholar]

- Umezawa T, Yoshida R, Maruyama K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K. SRK2C, a SNF1-related protein kinase 2, improves drought tolerance by controlling stress-responsive gene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2004;101:17306–17311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407758101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent O, Townley R, Kuchin S, Carlson M. Subcellular localization of the Snf1 kinase is regulated by specific beta subunits and a novel glucose signaling mechanism. Genes and Development. 2001;15:1104–1114. doi: 10.1101/gad.879301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZQ, Yuan YZ, Ou JQ, Lin QH, Zhang CF. Glutamine synthetase and glutamate dehydrogenase contribute differentially to proline accumulation in leaves of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seedlings exposed to different salinity. Plant Physiology. 2007;164:695–701. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yemm EW, Willis AJ. The estimation of carbohydrates in plant extracts by anthrone. Biochemical Journal. 1954;57:508–514. doi: 10.1042/bj0570508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Shewry PR, Jones H, Barcelo P, Lazzeri PA, Halford NG. Expression of antisense SnRK1 protein kinase sequence causes abnormal pollen development and male sterility in transgenic barley. The Plant Journal. 2001;28:431–441. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JK. Salt and drought stress signal transduction in plants. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2002;53:247–273. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.091401.143329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.