Abstract

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a risk factor for erectile dysfunction (ED). Although type 2 DM is responsible for 90–95% diabetes cases, type 1 DM experimental models are commonly used to study diabetes-associated ED.

Aim

Goto-Kakizaki (GK) rat model is relevant to ED studies since the great majority of patients with type 2 diabetes display mild deficits in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, insulin resistance, and hyperglycemia. We hypothesized that GK rats display ED which is associated with decreased nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability.

Methods

Wistar and GK rats were used at 10 and 18 weeks of age. Changes in the ratio of intracavernosal pressure/mean arterial pressure (ICP/MAP) after electrical stimulation of cavernosal nerve were determined in vivo. Cavernosal contractility was induced by electrical field stimulation (EFS) and phenylephrine (PE). In addition, nonadrenergic-noncholinergic (NANC)- and sodium nitroprusside (SNP)-induced relaxation were determined. Cavernosal neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) mRNA and protein expression were also measured.

Main Outcome Measure

GK diabetic rats display ED associated with decreased cavernosal expression of eNOS protein.

Results

GK rats at 10 and 18 weeks demonstrated impaired erectile function represented by decreased ICP/MAP responses. Ten-week-old GK animals displayed increased PE responses and no changes in EFS-induced contraction. Conversely, contractile responses to EFS and PE were decreased in cavernosal tissue from GK rats at 18 weeks of age. Moreover, GK rats at 18 weeks of age displayed increased NANC-mediated relaxation, but not to SNP. In addition, ED was associated with decreased eNOS protein expression at both ages.

Conclusion

Although GK rats display ED, they exhibit changes in cavernosal reactivity that would facilitate erectile responses. These results are in contrast to those described in other experimental diabetes models. This may be due to compensatory mechanisms in cavernosal tissue to overcome restricted pre-penile arterial blood supply or impaired veno-occlusive mechanisms.

Keywords: Goto-Kakizaki, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, Erectile Dysfunction, Corpus Cavernosum

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by high blood glucose levels. The pancreatic beta-cell and its secretory product, insulin, are central in the pathophysiology of diabetes [1,2]. Type 1 or insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (T1DM) results from an absolute deficiency of insulin due to autoimmune beta-cell destruction. In type 2, non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (T2DM), liver, muscle, and fat cells are resistant to the actions of insulin. The compensatory attempt by the beta-cell to release more insulin is not sufficient to maintain blood glucose levels within a normal physiological range, finally leading to the functional exhaustion of the surviving beta-cells [3,4]. Despite genetic predisposition, the risk of developing type 2 diabetes in humans increases with age, obesity, cardiovascular disease (hypertension, dyslipidemia), and a lack of physical activity [5,6].

Numerous studies have demonstrated that patients with DM have high rates of erectile dysfunction (ED) [7–9], whose prevalence ranges from 20% to 71% [10–12]. Fedele and coworkers [10] reported the prevalence of ED to be 51% among individuals with T1DM and 37% among those with T2DM in a cohort of approximately 10,000 men. Moreover, the Massachusetts Male Aging Study noted that the prevalence of ED in diabetic men is 50.7 per 1,000 population-years vs. 24.8 in those without diabetes [13].

Investigations in animal models and diabetic patients have implicated several mechanisms responsible for diabetes-associated ED, such as impaired vasodilatory signaling [14], nonadrenergic-noncholinergic (NANC) dysfunction [14], endothelial dysfunction [15–17], oxidative stress [18], pro-inflammatory changes, cavernosal hypercontractility [17,19], venoocclusive dysfunction [17], and hypogonadism [20].

In a recent review, Hidalgo-Tamola and Chitaley [21] emphasize that despite the fact that both T1DM and T2DM entail abnormal carbohydrate metabolism and hyperglycemia, these diseases differ in many characteristics including insulin and body mass index status as well as cytokine and lipid profiles. T2DM is responsible for 90–95% of cases of diabetes, although clinical and epidemiological studies seldom separate T1DM and T2DM. In addition, fewer than 10 basic science studies addressing mechanisms of ED in animal models of T2DM have been published.

The Goto-Kakizaki (GK) rat is a polygenic model of T2DM obtained through selective inbreeding of Wistar rats with abnormal glucose tolerance over several generations. It is characterized by non-obesity, moderate but stable fasting hyperglycemia, hypoinsulinemia, normolipidemia, impaired glucose tolerance, which appears at 2 weeks of age in all animals, and an early onset of diabetic complications. In adult GK rats, total pancreatic beta cell mass is decreased by 60% along with a similar decrease in pancreatic insulin stores. In addition to the defects in beta cells, impaired insulin sensitivity in the liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissues has also been reported. Impaired insulin secretion and hepatic glucose overproduction (hepatic insulin resistance) are early events in diabetic GK rats mostly contributing to development of hyperglycemia rather than the peripheral (muscle and adipose tissue) insulin resistance [22,23].

Although the GK rat is a valuable diabetes model that shares several features of the T2DM observed in humans, no studies on erectile function in these animals have been reported in the literature. Considering that: (i) diabetes induces ED; (ii) there are only few studies evaluating the effects of T2DM in erectile function [21]; (iii) nitric oxide (NO) plays a major role in erectile function, we have hypothesized that GK rats display ED which is associated with decreased NO bioavailability. To test our hypothesis, we have used GK rats of 10 and 18 weeks of age to determine erectile function and changes in corpora cavernosa reactivity to contractile and relaxant stimuli.

Methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats (10 and 18 weeks old; Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and GK rats (10 and 18 weeks old; in-house bred derived from the Tampa colony) were used in the present studies. All procedures were performed in accordance with the Guiding Principles in the Care and Use of Animals, approved by the Medical College of Georgia Committee on the Use of Animals in Research and Education. The animals were housed four per cage on a 12-hour light/dark cycle and fed a standard chow diet with water ad libitum.

Blood Glucose Measurement

Animals were fasted from 8 am to 12 pm (5 hours). Blood was drawn from the tail vein and glucose was measured by a commercially available glucose meter (Accu-Chek Active, Indianapolis, IN, USA).

In Vivo Measurements of Intracavernosal Pressure/Mean Arterial Pressure

Intracavernosal pressure (ICP) in response to electrical stimulation of the cavernosal nerve was assessed in control and GK rats, as previously described [24,25]. Animals were anaesthetized with 4% isoflurane in 10% oxygen (O2). To monitor and calculate mean arterial pressure (MAP) and ICP, the left femoral artery and the right crura were cannulated with a phenylephrine (PE)-10 tubing cannula tied with 6-0 silk suture and fitted to a heparinized saline-filled pressure transducer. The left cavernosal nerve was assessed via a midline incision and stimulated with bipolar silver electrode. ICP changes were then monitored in response to frequency curves (0.2–20 Hz; 5 ms pulses at 6 V). The stimulation at each frequency lasted for 45 seconds and each frequency curve was repeated after an interval of 5 minutes. ICP and arterial pressure were converted from analog to digital signals and transmitted to a data-acquisition program (Chart software, version 5.2; ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA). The erectile response was calculated using the maximum ICP response normalized to MAP at the time of maximum ICP. The area under the curve (AUC, in mmHg.s) for ICP was also recorded with stimulation at 12 Hz during a 40-second period. The AUC was determined after all frequency curves were performed. Three measurements were analyzed for each animal.

Functional Studies in Cavernosal Strips

Cavernosal strip preparation was obtained from each corpus cavernosum, as previously described [26]. Briefly, cavernosal strips (1 × 1 × 10 mm) were mounted in myographs containing physiological salt solution at 37°C and continuously bubbled with a mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2. The tissues were stretched to a resting force of 3.0 mN. Changes in isometric force were recorded. To verify the contractile ability of the preparations, a high potassium chloride (KCl) solution (120 mM) was added to the organ baths at the end of the equilibration period. Cumulative concentration–response curves to phenylephrine (10−8 M to 10−4 M) in the presence or absence of Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) (10−4 M) were performed with strips under basal tone. Electrical field stimulation (EFS) was applied to strips placed between platinum pin electrodes. EFS was conducted at 20 V, 1-ms pulse width, and trains of stimuli lasting 10 seconds at varying frequencies (1 to 64 Hz). To evaluate adrenergic nerve-mediated responses, strips were incubated with L-NAME (10−4 M) plus atropine (10−6 M) before EFS was performed. When atropine and L-NAME were used, drugs were administered 30–45 minutes before concentration–response or frequency–response curves were performed. To evaluate NANC-mediated relaxation, strips were incubated for 45 minutes with bretylium (3 × 10−5 M) plus atropine (10−6 M) (to eliminate noradrenergic and cholinergic nerves-mediated responses, respectively), contracted with PE (10−5 M), and frequency–response curves (1 to 64 Hz) were performed. Cumulative concentration–response curves to sodium nitroprusside (SNP) (10−9 M to 3 × 10−3 M; nitric oxide donor and endothelium-independent vasodilator) were performed in cavernosal strips contracted with PE (10−5 M; α1-adrenergic receptor agonist). Time control experiments were performed to determine force development of cavernosal strips not related to the effects of each antagonist/inhibitor. Control solutions containing vehicle were also used throughout the experimental protocols.

RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis, and Quantitative Real-Time Reverse-Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total RNA was extracted from cavernosal strips using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen Sciences, MD, USA). The quantity, purity, and integrity of all RNA samples were determined by NanoDrop spectrophotometers (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). One microgram of total RNA was reverse transcribed using the high-capacity cDNA archive kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), and single-strand cDNA was stored at −20°C. Primers for nNOS (N° Rn00583793_m1) and eNOS (N° Rn02132634_s1) mRNA were obtained from Applied Biosystems. Real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) reactions were performed using the 7500 fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Negative controls contained water instead of first-strand cDNA. Each sample was normalized on the basis of its 18S ribosomal RNA content. Relative gene expression for nNOS and eNOS was normalized to a calibrator that was chosen to be the basal condition (samples from control) for each time point. Results were calculated with the ΔΔCt method and expressed as n-fold differences in gene expression relative to 18S rRNA and to the calibrator and were determined as follows: n-fold = 2−(ΔCt sample − ΔCt calibrator), where the parameter Ct (threshold cycle) is defined as the fractional cycle number at which the PCR reaction reporter signal passes a fixed threshold.

Protein Expression

Cavernosal tissues were dissected and homogenized in protease inhibitor cocktail [(4-(2-aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride (AEBSF), pepstatin A, E-64, bestatin, leupeptin and aprotinin); Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA] using a small tissue homogenizer. The Bradford assay was used to measure protein concentration. A total of 60 µg of protein was loaded onto an SDS-PAGE 10% gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked with 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered solution with 1% Tween for 1 hour at room temperature. Membranes were then probed with rabbit polyclonal anti-eNOS (1:250; Cell Signaling), mouse monoclonal anti-nNOS (1:8,000; BD Transduction Laboratories), rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-eNOS (Ser 1177) (1:250; Cell Signaling), and mouse anti-β-actin (1:20,000; Sigma Aldrich). All primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C. Immunostaining was detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:2,000; GE Healthcare) and anti-mouse IgG (1:2,000; GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) for 1 hour at room temperature. For β-actin detection, the secondary antibody was used in a higher dilution (1:5,000). Immunoblots were revealed by the SuperSignal Substrate (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA) and quantitated by densitometry using a Scion Image analyzer software (Scion Image Corporation, Frederick, MD, USA).

Drugs and Solutions

Physiological salt solution of the following composition was used: 130 mM NaCl, 14.9 mM NaHCO3, 5.5 mM dextrose, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.18 mM KH2PO4, 1.17 mM MgSO4.7H2O, 1.6 mM CaCl2.2H2O, and 0.026 mM EDTA. Atropine, L-NAME, PE, SNP, and bretylium tosylate ([o-bromobenzyl] ethyldimethylammonium p-toluenesulfonate) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). All reagents used were of analytical grade. Stock solutions were prepared in deionized water and stored in aliquots at −20°C; dilutions were prepared immediately before use.

Statistical Analysis

Contractions were recorded as changes in the displacement from baseline and are represented as millinewtons (mN) normalized by dry weight (µg) of individual cavernosal tissue weight for n experiments. Relaxation is expressed as percentage change from the PE-contracted levels. Agonist concentration–response curves were fitted using a nonlinear interactive program (Graph Pad Prism 4.0; GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Agonist potencies are expressed as pD2 (negative logarithm of the molar concentration of agonist producing 50% of the maximum response). Emax (maximum effect elicited by the agonist) values are represented as milliNewtons (mN) for contractile responses or as a percentage change from the PE-contracted levels for relaxation responses. Statistical analyses of Emax and pD2 values were performed using nonlinear regression followed by F-test or Student’s t-test. Real-time PCR and Western blot data were analyzed by one-sample t-test and the P value was computed from the t ratio and the numbers of degrees of freedom. Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

GK rats at 10 and 18 weeks of age exhibited decreased body weight in comparison to their control littermates. In addition, the levels of blood glucose were statistically higher in GK rats compared to the respective control animals (Table 1). Cavernosal strips dry weight from GK rats at 10 weeks of age were decreased compared to control. Although at 18 weeks of age this difference was abolished, a clear tendency to reduce cavernosal weight was shown in GK rats (P = 0.0567) (Table 1). However, after normalization of cavernosal strips weight by body weight, GK rats at 10 weeks of age displayed increased ratio compared to control group and the increased tendency between control and GK rats at 18 weeks of age was abolished (P = 0.1064) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Metabolic parameters of control and GK rats at 10 and 18 weeks

| Control | GK | Control | GK | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | 10 weeks | 18 weeks | ||

| Body weight (g) | 370 ± 7 | 250 ± 8* | 564 ± 18 | 362 ± 9* |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 86 ± 4.7 | 133 ± 12.6* | 98 ± 1.6 | 155 ± 15* |

| Cavernosal strip (mg) | 10.4 ± 0.4 | 8.6 ± 0.4* | 16.1 ± 0.9 | 13.9 ± 0.6 |

| Cavernosal strip/body weight (µg/g) | 26.0 ± 1.2 | 36.0 ± 2.1* | 35.7 ± 1.8 | 39.8 ± 1.5 |

P < 0.05 vs. respective control group.

Values are means ± SEM for n = 7 in each group.

In Vivo Erectile Function

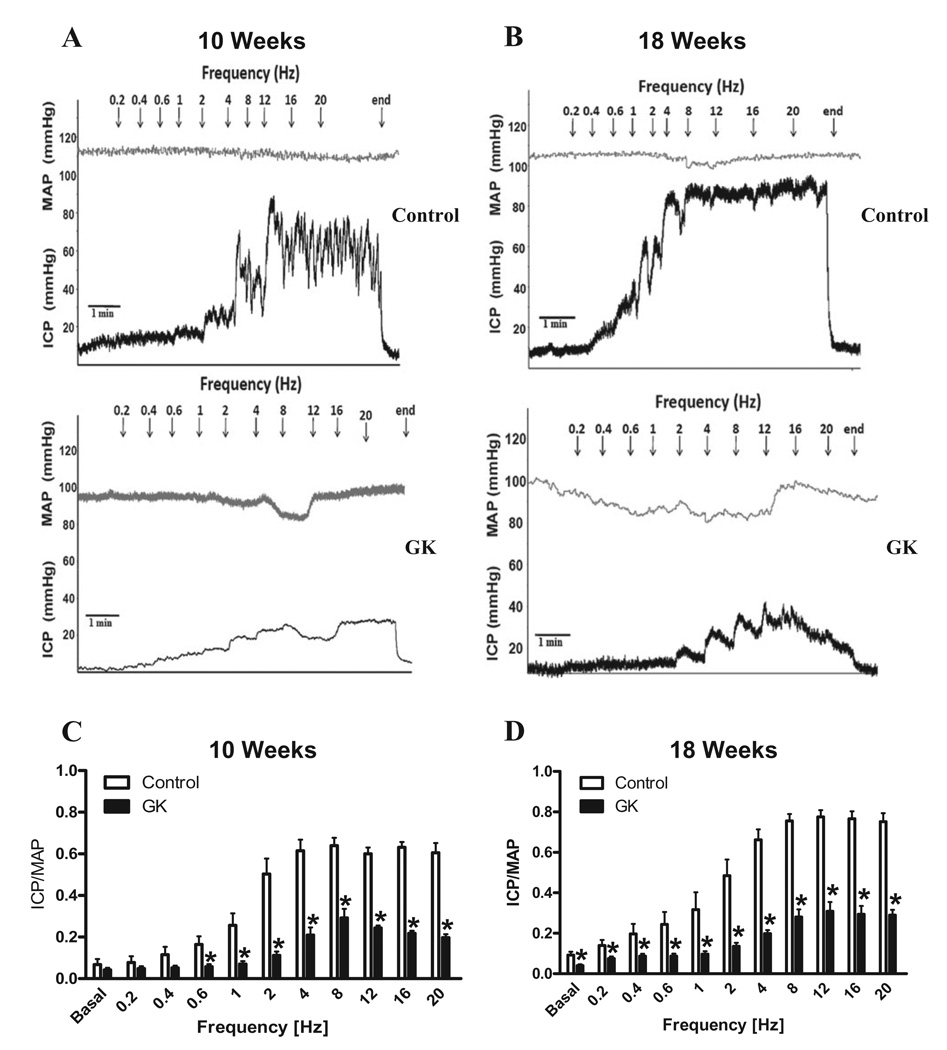

In vivo studies demonstrated that GK rats at 10 and 18 weeks of age display a significant reduction in erectile response following electrical stimulation of the cavernosal nerve (Figures 1A and B, respectively). This impairment was characterized by a decrease in maximal ICP/MAP responses after 0.6 Hz of stimulation in GK rats at 10 weeks of age (Figure 1C). At 18 weeks of age, ICP/MAP was decreased at both basal and at all frequencies of stimulation in GK rats (Figure 1D). Similarly, the AUC (at 12Hz) was significantly reduced in GK rats at 10 (Control: 573 ± 75 vs. GK: 245 ± 34; mmHg.s) and 18 (Control: 572 ± 43 vs. GK: 261 ± 63; mm Hg/s) weeks of age compared to control group.

Figure 1.

Type 2 diabetic GK rats display erectile dysfunction. In vivo assessment of maximal ICP/MAP responses to cavernosal nerve stimulation. Representative tracings of the ICP and MAP responses to electrical stimulation of the cavernosal nerve in control (top) and GK rats (bottom) at 10 (A) and 18 (B) weeks of age. Bar graphs data represent maximal ICP/MAP in control (open bars) and GK rats (filled bars) at 10 (C) and 18 (D) weeks of age. Values represent mean ± SEM of n = 8–9 per group. *, P < 0.05 compared with values from control rats.

Functional Studies in Cavernosal Strips

Cavernosal reactivity studies were carried out in animals of 10 and 18 weeks of age to verify if cavernosal alterations occur in early stages of diabetes in this model.

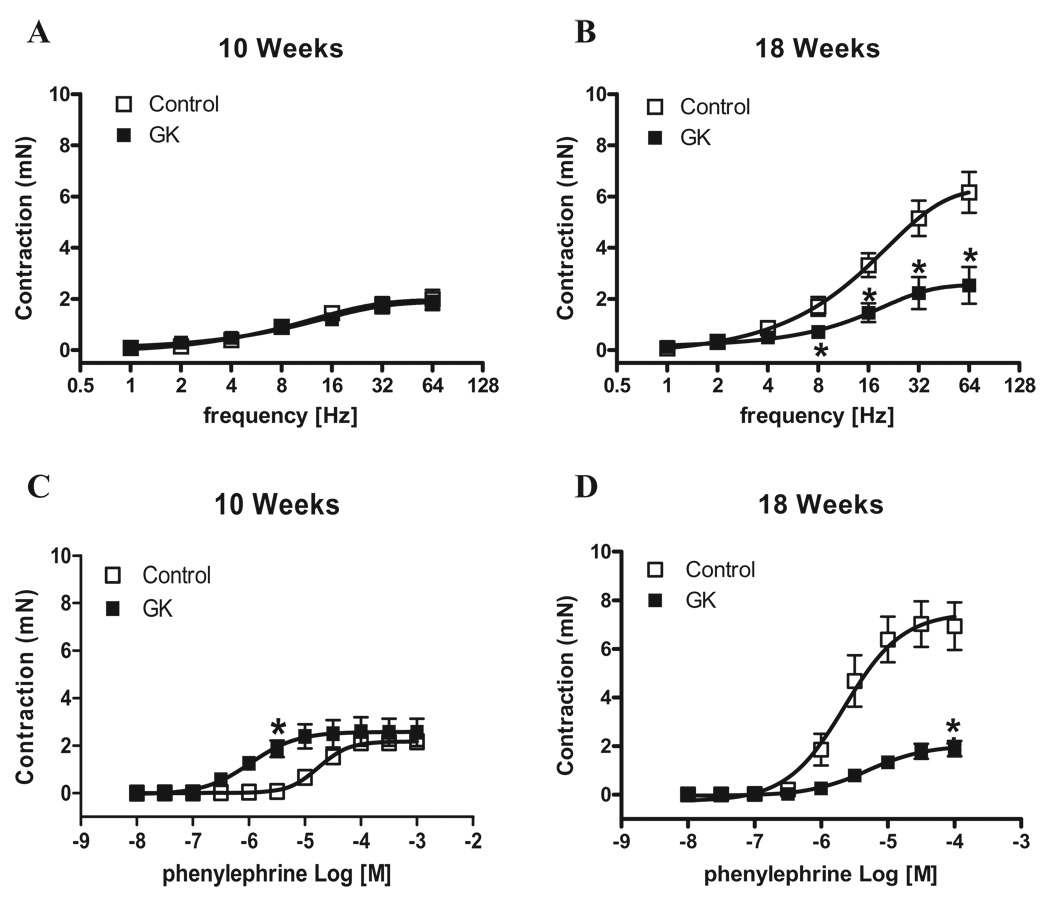

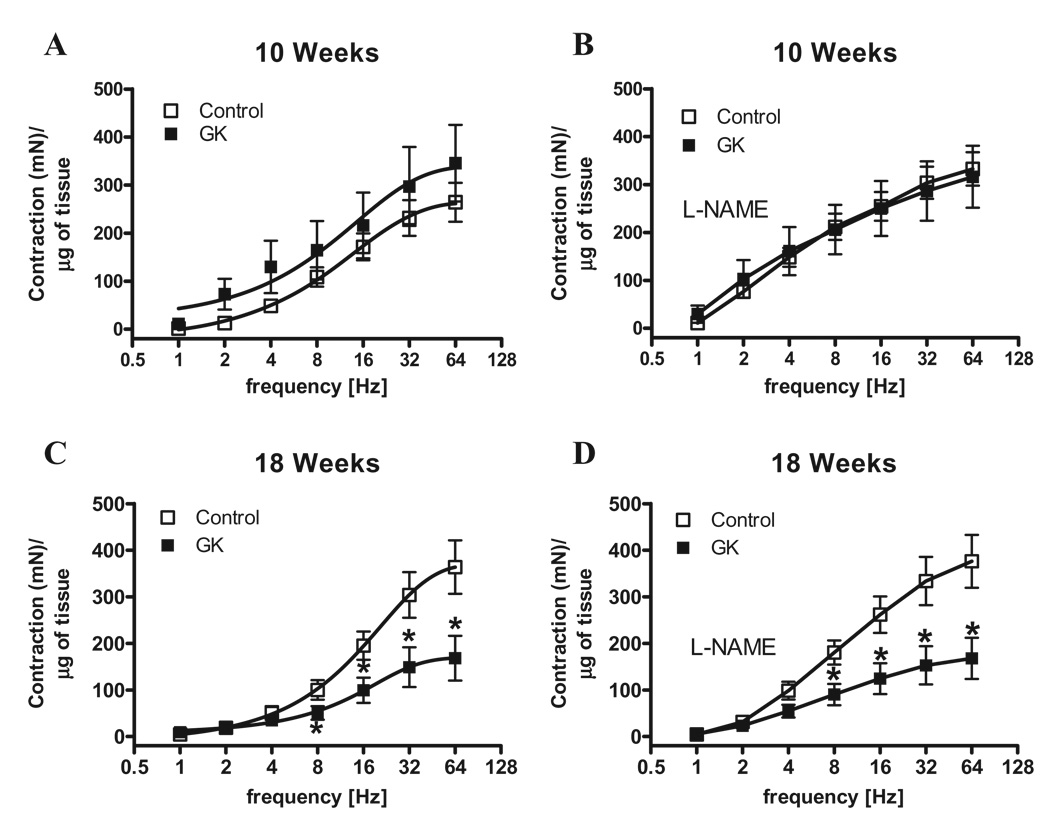

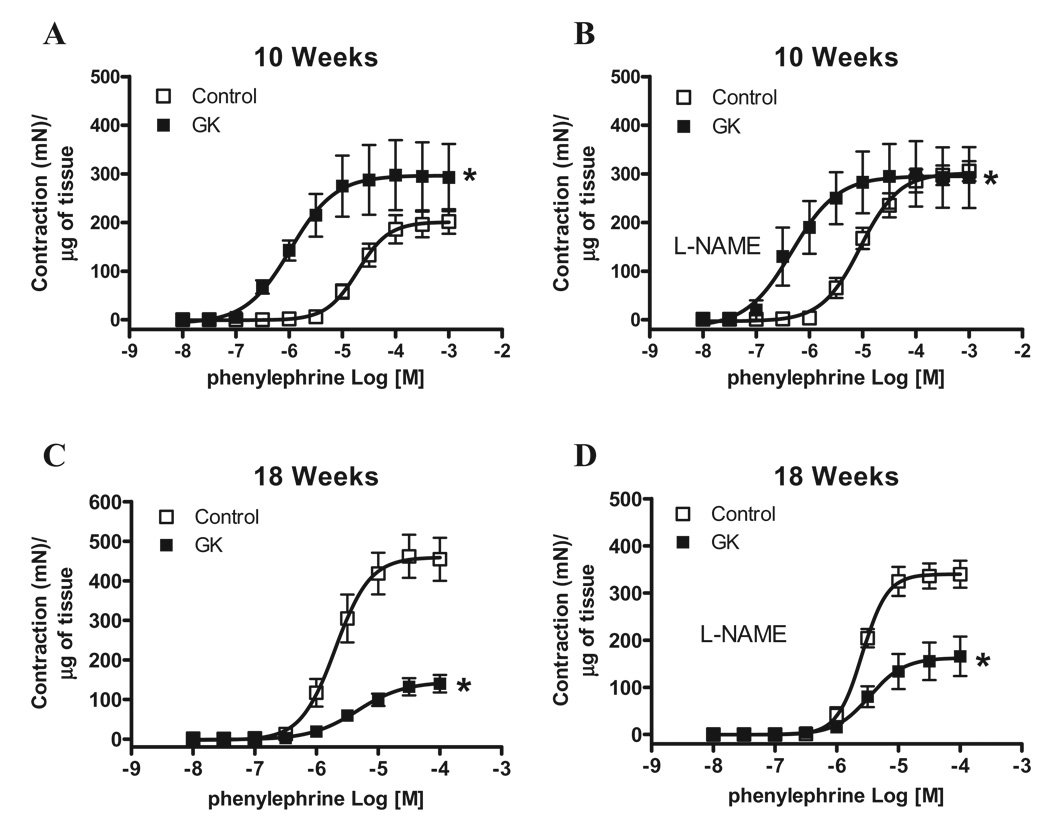

Considering that the penis is kept in the flaccid state mainly by sympathetic activation, we determined responses induced by EFS (adrenergic nerve stimulation) in the first set of experiments. Contractile responses to EFS were not altered between cavernosal strips from control and GK rats at 10 weeks of age (Figure 2A). However, cavernosal strips from GK rats at 18 weeks of age displayed decreased response to EFS compared to age-matched control animals (P < 0.05) (Figure 2B). While EFS-induced contraction evaluates sympathetic-mediated responses, contractile responses elicited by PE allow inferences on contraction by direct activation of adrenergic receptors in cavernosal smooth muscle cells. Considering that the impaired contractile response to EFS in cavernosal strips from GK rats could be due either to decreased prejunctional release of neurotransmitter or impaired postjunctional signaling in the smooth muscle cells, direct stimulation of cavernosal smooth muscle strips with PE allows the evaluation of postjunctional changes. Accordingly, cavernosal strips from GK rats showed increased contractile response to PE at 10 weeks of age (Figure 2C). Conversely, contractile responses to PE in cavernosal tissue from GK rats at 18 weeks of age were decreased (Figure 2D). To verify if this decreased contractile response is specific for EFS and PE, cavernosal strips were stimulated with 120 mM KCl. Cavernosal responses were not different between control and GK rats at 10 weeks. However, cavernosal strips from 18-week-old GK rats showed a decreased response to KCl compared to control (Control: 4.65 ± 0.34 [n = 7] vs. GK: 1.47 ± 0.25 [n = 7], mN) (Table 2), which suggests that the changes are not related only to the sympathetic adrenergic system, but also direct changes in cavernosal smooth muscle may be involved. Considering that GK rats display reduced body weight (Table 1) and that decreased cavernosal weight could account for the difference observed in contraction, the contractile responses to EFS and PE were normalized by the cavernosal weight. However, even after normalization by the cavernosal weight, the pattern observed in contractile responses to EFS (Figure 3) and to PE (Figure 4) was not altered. It is noteworthy that incubation of cavernosal strips with L-NAME potentiates contractile responses to EFS (Figure 3) at both ages. In contrast, contractile responses to PE were only potentiated in the control group at 10 but not at 18 weeks of age (Table 2). In addition, L-NAME did not abolish the differences in responses to EFS (Figure 3) or PE (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Corpora cavernosa from GK rats display decreased responses to sympathetic nerve stimulation and α-adrenoreceptors activation. Contractile responses of cavernosal strips from control (□) and GK (■) rats at 10 and 18 weeks of age upon stimulation of adrenergic nerves by EFS and PE. (A and B) Frequency-response curves elicited by EFS (1–64 Hz). (C and D) PE concentration-response curves. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 7). *P < 0.05 compared with values from control rats.

Table 2.

Emax and pD2 values for agonists-induced responses in cavernosal tissue from control and GK rats

| Control | GK | Control | GK | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 weeks | 10 weeks | |||

| Agonist | pD2 | Emax | ||

| KCl (120 mM) | n.d. | n.d. | 1.64 ± 0.27 | 1.70 ± 0.27 |

| Phenylephrine | 4.71 ± 0.06 | 5.96 ± 0.18* | 2.29 ± 0.09 | 2.57 ± 0.18 |

| Phenylephrine + L-NAME | 5.01 ± 0.04** | 6.31 ± 0.19* | 3.21 ± 0.07** | 2.46 ± 0.17* |

| SNP | 5.49 ± 0.39 | 6.05 ± 0.17 | 72.91 ± 11.94 | 79.14 ± 4.55 |

| 18 weeks | 18 weeks | |||

| pD2 | Emax | |||

| KCl | n.d. | n.d. | 4.65 ± 0.34 | 1.47 ± 0.25* |

| Phenylephrine | 5.67 ± 0.15 | 5.30 ± 0.14 | 7.00 ± 0.48 | 2.03 ± 0.15* |

| Phenylephrine + L-NAME | 5.58 ± 0.03 | 5.44 ± 0.17 | 5.82 ± 0.14** | 2.39 ± 0.30* |

| SNP | 5.34 ± 0.12 | 5.93 ± 0.14* | 69.59 ± 3.87 | 86.93 ± 3.70* |

P < 0.05 GK vs. respective control;

P < 0.05 vehicle vs. L-NAME incubation.

Values are means ± SEM for n = 5–7 experiments in each group. Emax values for KCl and PE are represented as mN. Relaxation induced by SNP was calculated relative to the maximal changes from the contraction produced by PE and Emax values are represented as % of relaxation. PE, phenylephrine; KCl, potassium chloride; SNP, sodium nitroprusside; Emax, maximum effect elicited by the agonist; pD2, negative logarithm of EC50; n.d. = non-determined.

Figure 3.

Normalization of corpora cavernosa contractile responses by the weight of cavernosal strips or inhibition of NOS does not change decreased EFS contractile responses in corpora cavernosa from GK rats. Contractile responses of cavernosal strips from control (□) and GK (■) rats at 10 and 18 weeks of age upon stimulation of adrenergic nerves by EFS. Frequency-response curves elicited by EFS (1–64 Hz) in the absence (A and C) or presence (B and D) of L-NAME 10−4 M. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 7). *, P < 0.05 compared with values from control rats. In all conditions contractile responses were normalized by the weight of each cavernosal strip and are represented as development of isometric force (mN) by weight (g) of tissue.

Figure 4.

Normalization of corpora cavernosa contractile responses by the weight of cavernosal strips or inhibition of NOS does not change decreased PE contractile responses in corpora cavernosa from GK rats. Contractile responses of cavernosal strips from control (□) and GK (■) rats at 10 and 18 weeks of age upon stimulation of α-adrenoreceptors by PE. Concentration response curves to PE were performed in the absence (A and C) or presence (B and D) of L-NAME 10−4 M. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 7). *, P < 0.05 compared with values from control rats. In all conditions contractile responses were normalized by the weight of each cavernosal strip and are represented as development of isometric force (mN) by weight (g) of tissue.

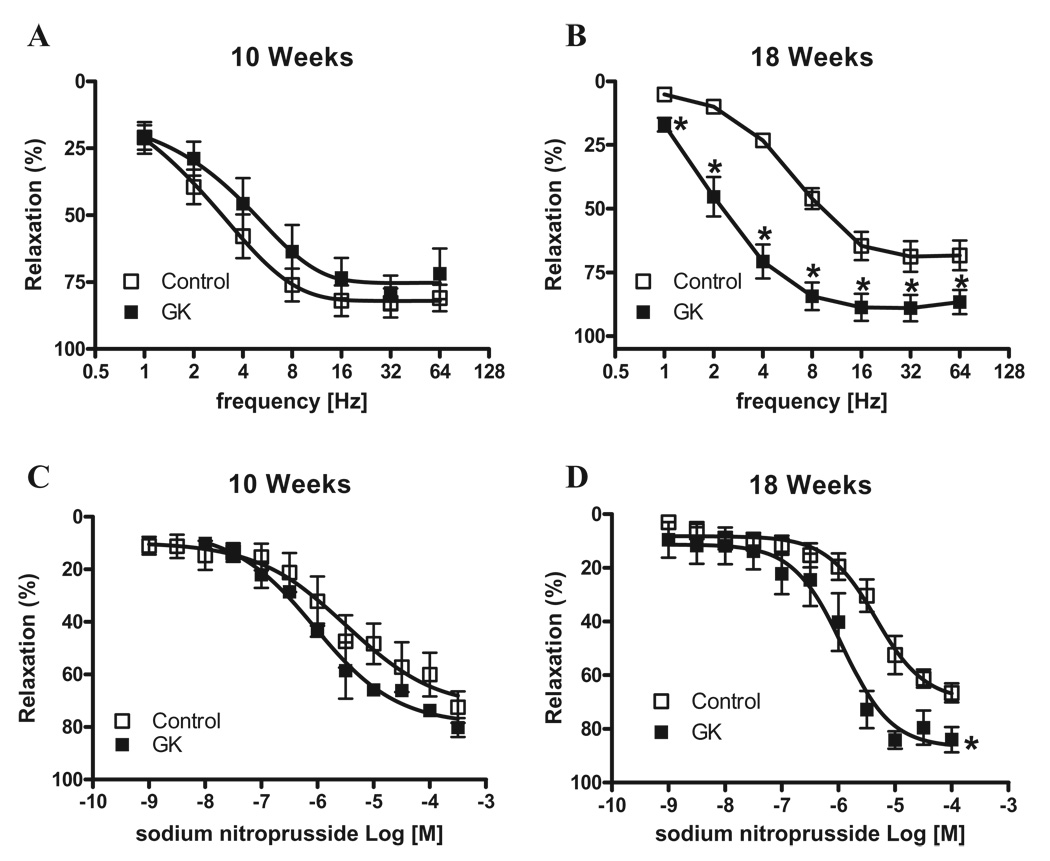

In the second set of experiments, we determined whether relaxation responses were also altered in corpora cavernosa from GK rats. NANC induced-relaxation was not changed in cavernosal tissue from GK rats at 10 weeks (Figure 5A). Conversely, GK rats at 18 weeks of age demonstrated greater relaxation of cavernosal tissue than control animals (Figure 5B). The cumulative addition of SNP (10−9 to 3 × 10−4 M) produced concentration-dependent relaxation of PE-contracted tissues (Table 2). Cavernosal relaxation responses to SNP were increased in GK rats at 18 weeks of age, but no differences were observed in strips from 10-week-old animals (Figures 5C and D).

Figure 5.

Cavernosal strips from GK rats display increased relaxation to NANC nerve stimulation. NANC nerve-induced relaxation response of cavernosal segments from control (□) and GK (■) rats at 10 and 18 weeks of age. (A and B) Frequency–response curves elicited by EFS (1–64 Hz) in cavernosal strips incubated with bretylium tosylate (3 × 10−5 M) and atropine (10−6 M). (C and D) Sodium nitroprusside concentration-effect curves. Experimental values of the relaxations induced by EFS and sodium nitroprusside were calculated relatively to the maximal changes from the contraction produced by PE in each tissue, which was taken as 100%. Data represent the mean ± SEM of n = 7 experiments in each group. *P < 0.05 vs. control.

NOS mRNA and Protein Expression

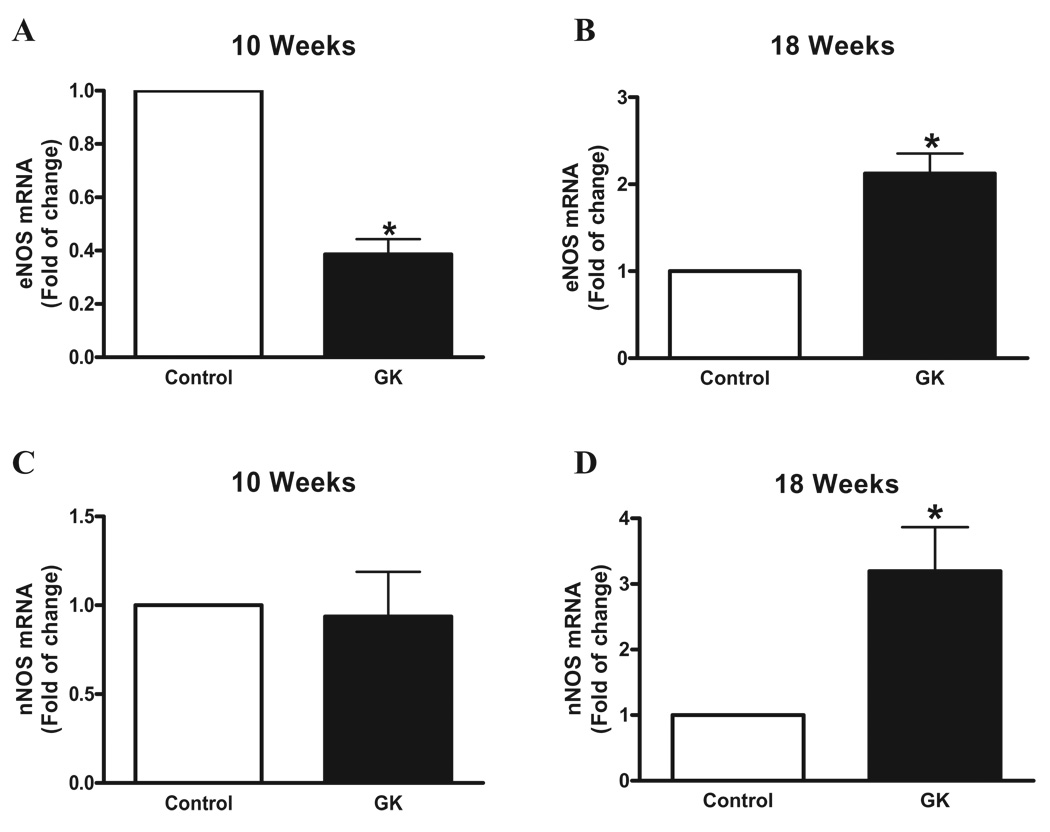

The eNOS mRNA expression was decreased in cavernosal tissue from GK rats at 10 weeks of age (Figure 6A). In contrast, eNOS mRNA expression was increased in corpora cavernosa of GK rats 18 weeks old (Figure 6B). Expression of nNOS was increased in cavernosal strips from GK rats at 18 weeks of age, but no changes were observed between control and GK rats at 10 weeks of age (Figures 6C and D).

Figure 6.

Corpora cavernosa from GK rats exhibit increased nNOS and eNOS gene expression. Messenger RNA expression of eNOS (A and B) and nNOS (C and D) determined by qPCR using total RNA extracted from cavernosal tissue of control (open bar) and GK (filled bar) rats. Bar graphs show fold of change in nNOS and eNOS mRNA expression. Values were normalized by the correspondent 18s rRNA of each sample. Results are mean ± SEM (n = 5 to 7). *p < 0.05 vs control group.

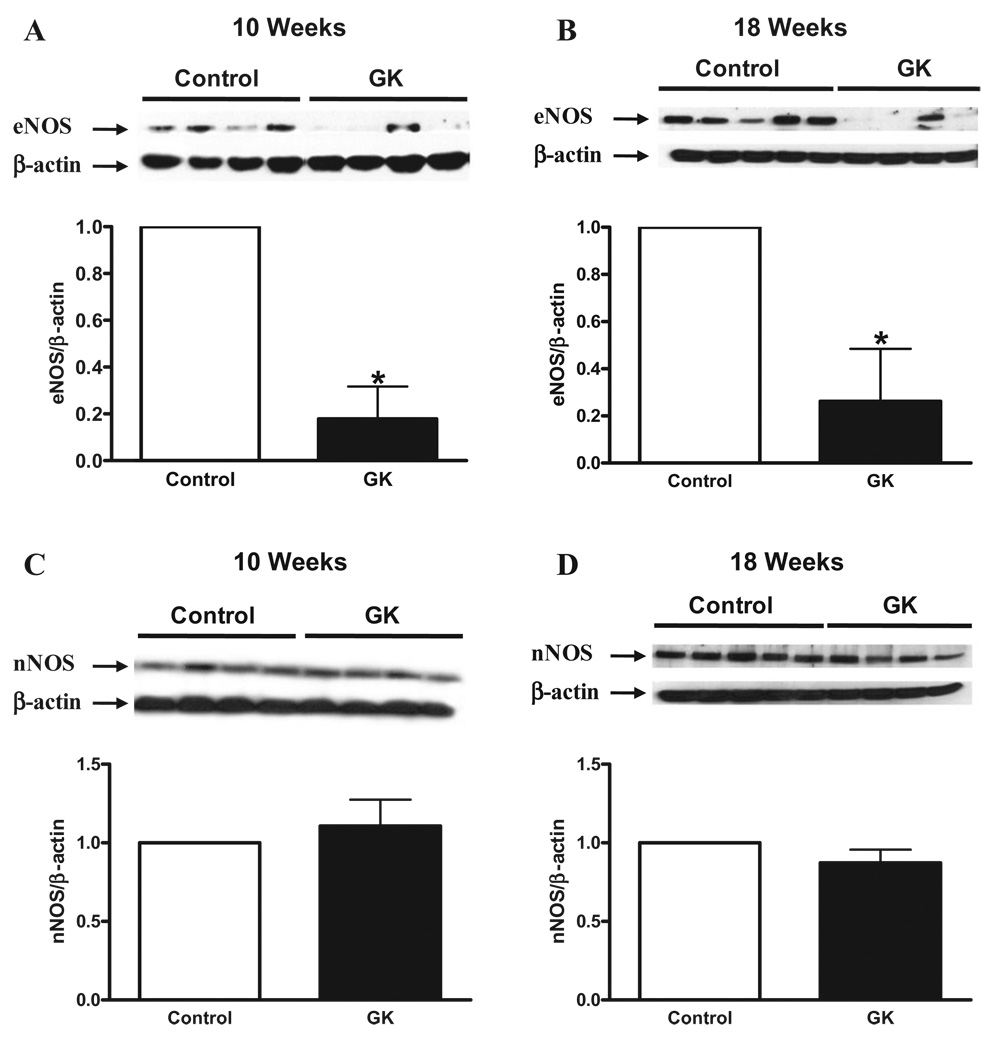

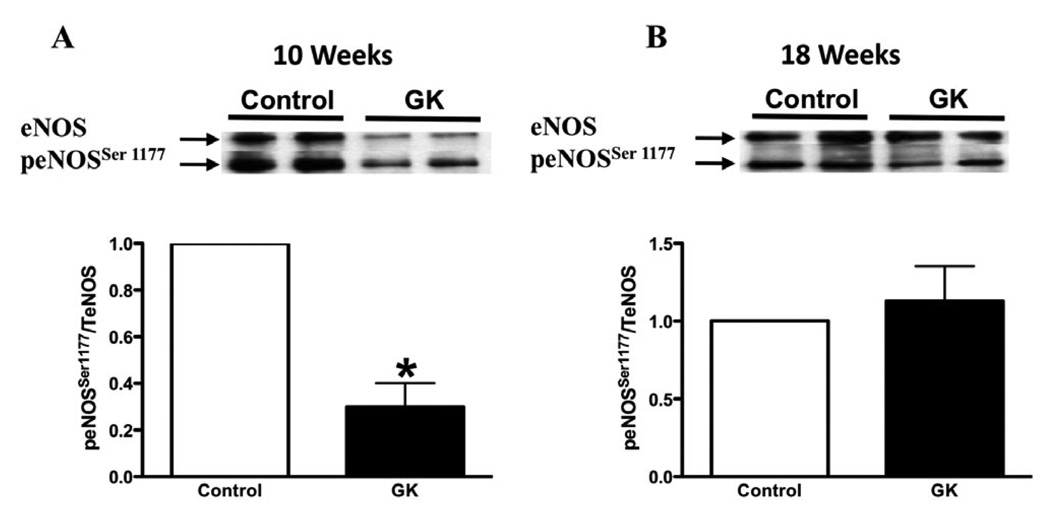

In order to determine if the changes observed in mRNA expression would be translated into protein level, eNOS and nNOS protein expression was performed by Western blot. eNOS protein expression was decreased in cavernosal tissue from GK rats at both ages (Figures 7A and B), but no changes were observed in nNOS protein expression (Figures 7C and D). In addition to the decreased levels of eNOS expression, the phosphorylation levels of eNOS at Ser [1177], which accounts for eNOS activity, was found to be decreased in the cavernosal tissue of GK rats at 10 weeks (Figure 8A), but no changes were observed at 18 weeks (Figure 8B).

Figure 7.

Corpora cavernosa from GK rats exhibit decreased nNOS and eNOS protein expression. Protein expression of eNOS (A and B) and nNOS (C and D) determined by Western blot using total protein extracted from cavernosal tissue of control (open bar) and GK (filled bar) rats. Bar graphs show fold of change in nNOS and eNOS protein expression. Values were normalized by the correspondent α-actin of each sample. Results are mean ± SEM (n = 5 to 7). *P < 0.05 vs control group.

Figure 8.

eNOS phosphorylation levels at Ser [1177] in corpora cavernosa from control and GK rats. Phosphorylation of eNOS at Ser [1177] was determined byWestern blot using total protein extracted from cavernosal tissue of control (open bar) and GK (filled bar) rats at 10 (A) and 18 (B) weeks of age. Bar graphs show fold of change in phopho-eNOS protein expression. Values were normalized by the correspondent total eNOS expression of each sample. Results are mean ± SEM (n = 4 to 5). *P < 0.05 vs. control group.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that cavernosal tissue from GK rats displays functional changes that would facilitate penile erection. Nevertheless, GK rats display decreased in vivo erectile response following electrical stimulation of the cavernosal nerve. This study also shows that the expression of a key enzyme involved in erectile responses, eNOS is decreased in cavernosal strips from GK rats.

In the first set of experiments, we observed that following electrical stimulation of the cavernosal nerve, GK rats display an inability to achieve similar levels of maximum ICP/MAP observed in control animals. In addition, AUC measurements revealed a strikingly decreased response in GK rats. This impairment, along with the decreased maximum ICP/MAP after cavernosal nerve stimulation, may reflect insufficient blood inflow to corpora cavernosa resulting in ED. This finding is consistent with a report by Luttrell and collaborators [17] that demonstrated that db/db mice, a type II diabetic mouse model, display ED. Similar results were also observed in a type II diabetic rat model [16].

Several reports in the literature have demonstrated that obesity is an independent risk factor for ED [13,27,28]. Furthermore, abdominal adiposity and physical inactivity increases the odds of ED [29]. On the other hand, experimental studies have shown improvement in erectile function with exercise and caloric restriction [30]. In addition, cardiovascular risk factors associated with obesity, endothelial dysfunction and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines are proposed mechanisms for obesity-associated ED [31]. However, it is noteworthy to observe that ICP/MAP responses in GK rats were smaller than those observed in previous studies in diabetic and obese animals [16,17], suggesting greater impairment in erectile function of GK rats. Considering that obesity is thought to worsen ED, this apparent discrepancy remains unclear, and more studies are warranted to solve this question. However, type 2 diabetes is typically associated with hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia. In contrast, GK rats present mild hyperglycemia combined with defective β-cell mass and function [22], which ultimately results in decreased plasma insulin levels. Thus, genetic variation resulting in different metabolic profile among these animal models may account for the observed differences.

Decreased ICP/MAP responses following electrical stimulation of cavernosal nerve in GK rats may reflect insufficient blood inflow to the penis due to hypercontractility of cavernosal tissue. Accordingly, several studies have demonstrated that type I [32] and type II [16,17,19], diabetes experimental models display increased contractile responses in cavernosal tissue. The most predominant dysfunction observed in type II diabetic animals is increased response to EFS, which is driven by sympathetic nerve activation or direct adrenergic receptor stimulation [16,17,19]. In addition, human diabetic patients exhibit autonomic neuropathy, normally manifested as a sympathetic overdrive, which can be associated with a sympatho-vagal imbalance [33]. It is known that in the smooth muscle septa surrounding the cavernous spaces, and around the central and helicine arteries, there are a large number of sympathetic nerve endings and few-to-moderate numbers of parasympathetic endings [34]. While nerve damage and neurodegenerative processes undoubtedly contribute to ED, it is not clear whether there is any etiological mechanism in patients that is nerve-specific, rather than being simply a reflection of the neural consequences of the physiological challenge caused by vascular dysfunction. Accordingly, impaired neural tissue blood flow is a major contributor to diabetic neuropathy in man and animal models [35].

In contrast, the present study demonstrated that GK rats first display increased contractile response at 10 weeks, which was followed by decreased contractile response to sympathetic or direct adrenergic receptors stimulation at 18 weeks. Taken into account that GK rats display reduced body weight, one may ask if the decreased contractile responses reflect changes in cavernosal mass. However, after normalization of contractile responses by penis weight, GK rats still displayed decreased cavernosal contractions. Accordingly, Kobayashi and coworkers [36] demonstrated decreased contractile responses in aortic rings from GK rats in an age-dependent fashion. In addition, increased levels of noradrenaline and neuropeptide Y (NYP) have been demonstrated in cavernosal tissue from GK rats of 52 weeks of age [37]. Taken together, this evidence suggests that increased cavernosal levels of noradrenaline may trigger increased cavernosal reactivity at first, and subsequently lead to the activation of compensatory mechanisms to prevent damage or further increase in smooth muscle cell contractility in corpora cavernosa from GK rats. However, additional studies are required to fully address that possibility. Additional support to this idea is the fact that vascular tissue from GK rats displays increased expression of α2D-adrenergic receptor subtype [36], which accounts for endothelium-dependent NO-mediated relaxation [38], thus limiting the contractile effects of noradrenaline. However, it is important to mention that studies have demonstrated increased contractile responses to endothelin-1 (ET-1) in other vascular beds from GK rats, such as mesenteric [39] and basilar artery [39,40].

Isolated cavernosal segments from GK rats at 10 weeks of age displayed no changes in NANC-mediated relaxation. However, at 18 weeks, increased cavernosal NANC relaxation was observed. Whereas eNOS activation seems to account for endothelium-induced relaxation, NANC-induced relaxation of cavernosal segments is primarily mediated via NO derived from nNOS. Although nNOS gene expression was increased, protein expression was not modified in cavernosal tissue from GK rats after 18 weeks. However, at this age, corpora cavernosa from GK rats displayed increased endothelium-independent relaxation to a NO donor, suggesting greater sensitivity of cavernosal smooth muscle cells to NO actions. Conversely, decreased protein expression of eNOS was observed at both ages in GK rat cavernosal tissue. Interestingly, eNOS gene expression was found to be decreased at 10 weeks, which was subsequently increased in cavernosal strips of GK rats at 18 weeks. The phosphorylation of eNOS at Ser [1177] is frequently associated to its activation [41]. In our studies, we demonstrated that eNOS phosphorylation at Ser [1177] is decreased in GK rats at 10 weeks, but no changes were observed at 18 weeks. These results not only suggest an age-dependent differential regulation of eNOS gene transcription in cavernosum of GK rats, but also that counter-regulatory mechanisms may be activated attempting to reestablish eNOS expression to control levels. Nevertheless, additional enzyme alterations may be brought by the diabetic condition. Accordingly, O-Linked β-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) modification is a post-translational modification that reciprocally and dynamically occupies eNOS at Ser [1177], thus inhibiting the enzyme phosphorylation and activity. Musicki and coworkers [42] elegantly demonstrated that O-GlcNac modification decreased eNOS phosphorylation at Ser [1177] in diabetic penile tissue, which may contribute to ED associated with diabetes. Although increased eNOS expression has been reported in aortic tissue from GK animals [36,43], NO bioavailability seems to be reduced mainly by increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production [43]. Moreover, NO synthase activity has been reported to be increased in type I diabetes [44]. However, numerous studies have demonstrated impairment of NANC-mediated relaxation in type I diabetes [32,45–48], and consistent with these functional reports, nNOS expression and activity have also been reported to be significantly decreased in type I diabetes [49–51]. Furthermore, Cellek and coworkers [51] demonstrated degeneration of nitrergic nerves in type I diabetic animals, which may account for the lowered nNOS expression and decreased functional responses observed in these animals. Interestingly, NANC responses have also been reported in type II diabetes [16,17], and reduced content of nNOS was demonstrated in type II diabetic Otsuka Long Evans Fatty rats [52]. On the other hand, other studies in different type II diabetes model were unable to observe reduced levels of nNOS [14,52]. Taken together, these results in the literature demonstrate variation not only in functional responses, but also in the expression levels of key enzymes involved in erection: nNOS and eNOS in diabetic condition. Differences in metabolic profile, insulin sensitivity, glycemic levels and animal species between the models utilized may account for the apparent discrepancies observed. In addition, Chitaley [53] has speculated that nNOS functionally altered responses likely do not have pathophysiological relevance to ED development in db/db animals, since they found only a mild impairment in parasympathetic-mediated relaxation [17]. Similarly, our results point in the same direction, indicating that it is not always that functional responses in cavernosal tissue correlate with erectile function in vivo, since compensatory mechanisms may be activated in the cavernosal tissue to overcome the impairment in erectile responses.

Although peripheral neural damage is a very well-known complication of diabetes that can lead to neurogenic ED, the main factor of ED in men with diabetes is vasculogenic, because of arterial insufficiency or veno-occlusive dysfunction [54,55]. Veno-occlusive dysfunction is characterized by an inability to limit the outflow of blood from the cavernosum, resulting in a venous leak. Similarly to humans, veno-occlusive dysfunction seems to play a major role in experimental models of type II diabetes-associated ED [17,56].

Finally, decreased relaxation in pre-penile vessels also leads to a decreased erectile response, since pudendal arteries seems to contribute to 70% of the resistance to blood inflow in the penis [57]. Based on that, it is reasonable to speculate that impairment of pudendal arteries function in GK animals and, consequently, ED may trigger increased cavernosal relaxation, as a counter-regulatory mechanism. However, further studies are necessary to investigate these possibilities.

Herein, we present the novel observation that GK rats display decreased erectile response following electrical stimulation of cavernosal nerve. Despite this fact, decreased contractile responses and increased NANC-mediated cavernosal relaxation were observed. Associated with the functional responses, eNOS protein expression and activity was decreased, but no changes were observed in nNOS protein expression. Although it is challenging to reconcile the in vivo with the functional in vitro results, differences between these experimental conditions and its influence upon NO bioavailability may account for the observed discrepancy. For instance, asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) is an endogenous inhibitor for NO synthesis and its plasma levels are increased in diabetic patients, leading to endothelial dysfunction [58]. Moreover, differences in ROS generation between in vivo and in vitro conditions might also explain the conflicting results. On the other hand, compensatory mechanisms may occur to limit the damage extension in the cavernosal tissue. In addition, the present study introduces a new diabetes-associated ED model that will contribute to understand the different mechanisms underlying ED in type II diabetes.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL71138 and DK83685).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None.

-

Category 1

-

Conception and DesignFernando S. Carneiro; Rita C. Tostes

-

Acquisition of DataFernando S. Carneiro; Fernanda R.C. Giachini; Zidonia N. Carneiro; Victor V. Lima

-

Analysis and Interpretation of DataFernando S. Carneiro; Rita C. Tostes

-

-

Category 2

-

Drafting the ArticleFernando S. Carneiro; Rita C. Tostes

-

Revising It for Intellectual ContentRita C. Tostes; Adviye Ergul; R. Clinton Webb

-

-

Category 3

-

Final Approval of the Completed ArticleRita C. Tostes

-

References

- 1.Kloppel G, Lohr M, Habich K, Oberholzer M, Heitz PU. Islet pathology and the pathogenesis of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus revisited. Surv Synth Pathol Res. 1985;4:110–125. doi: 10.1159/000156969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell GI, Polonsky KS. Diabetes mellitus and genetically programmed defects in beta-cell function. Nature. 2001;414:788–791. doi: 10.1038/414788a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(1 suppl):S5–S20. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2007.s5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahn SE. Clinical review 135: The importance of beta-cell failure in the development and progression of type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:4047–4058. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.9.7713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng D. Prevalence, predisposition and prevention of type II diabetes. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2005;2:29. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-2-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramarao P, Kaul CL. Insulin resistance: Current therapeutic approaches. Drugs Today (Barc) 1999;35:895–911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosen RC, Wing R, Schneider S, Gendrano N., 3rd Epidemiology of erectile dysfunction: The role of medical comorbidities and lifestyle factors. Urol Clin North Am. 2005;32:403–417. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2005.08.004. v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Latif MA, Makhlouf AA, Moustafa YM, Gouda TE, Niederberger CS, Elhanbly SM. Diagnostic value of nitric oxide, lipoprotein(a), and malondialdehyde levels in the peripheral venous and cavernous blood of diabetics with erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 2006;18:544–549. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yaman O, Akand M, Gursoy A, Erdogan MF, Anafarta K. The effect of diabetes mellitus treatment and good glycemic control on the erectile function in men with diabetes mellitus-induced erectile dysfunction: A pilot study. J Sex Med. 2006;3:344–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fedele D, Bortolotti A, Coscelli C, Santeusanio F, Chatenoud L, Colli E, Lavezzari M, Landoni M, Parazzini F. Erectile dysfunction in type 1 and type 2 diabetics in Italy. On behalf of Gruppo Italiano Studio Deficit Erettile nei Diabetici. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:524–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Penson DF, Latini DM, Lubeck DP, Wallace KL, Henning JM, Lue TF. Do impotent men with diabetes have more severe erectile dysfunction and worse quality of life than the general population of impotent patients? Results from the Exploratory Comprehensive Evaluation of Erectile Dysfunction (ExCEED) database. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1093–1099. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.4.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldstraw MA, Kirby MG, Bhardwa J, Kirby RS. Diabetes and the urologist: A growing problem. BJU Int. 2007;99:513–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johannes CB, Araujo AB, Feldman HA, Derby CA, Kleinman KP, McKinlay JB. Incidence of erectile dysfunction in men 40 to 69 years old: Longitudinal results from the Massachusetts male aging study. J Urol. 2000;163:460–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vernet D, Cai L, Garban H, Babbitt ML, Murray FT, Rajfer J, Gonzalez-Cadavid NF. Reduction of penile nitric oxide synthase in diabetic BB/WORdp (type I) and BBZ/WORdp (type II) rats with erectile dysfunction. Endocrinology. 1995;136:5709–5717. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.12.7588327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hurt KJ, Musicki B, Palese MA, Crone JK, Becker RE, Moriarity JL, Snyder SH, Burnett AL. Akt-dependent phosphorylation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase mediates penile erection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:4061–4066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052712499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wingard C, Fulton D, Husain S. Altered penile vascular reactivity and erection in the Zucker obese-diabetic rat. J Sex Med. 2007;4:348–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00439.x. (Discussion 62–3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luttrell IP, Swee M, Starcher B, Parks WC, Chitaley K. Erectile dysfunction in the type II diabetic db/db mouse: Impaired venoocclusion with altered cavernosal vasoreactivity and matrix. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H2204–H2211. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00027.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newsholme P, Haber EP, Hirabara SM, Rebelato EL, Procopio J, Morgan D, Oliveira-Emilio HC, Carpinelli AR, Curi R. Diabetes associated cell stress and dysfunction: Role of mitochondrial and non-mitochondrial ROS production and activity. J Physiol. 2007;583:9–24. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.135871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carneiro FS, Giachini FR, Lima VV, Carneiro ZN, Leite R, Inscho EW, Tostes RC, Webb RC. Adenosine actions are preserved in corpus cavernosum from obese and type II diabetic db/db mouse. J Sex Med. 2008;5:1156–1166. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00752.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corona G, Mannucci E, Petrone L, Ricca V, Balercia G, Mansani R, Chiarini V, Giommi R, Forti G, Maggi M. Association of hypogonadism and type II diabetes in men attending an outpatient erectile dysfunction clinic. Int J Impot Res. 2006;18:190–197. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hidalgo-Tamola J, Chitaley K. Review type 2 diabetes mellitus and erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2009;6:916–926. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Portha B. Programmed disorders of beta-cell development and function as one cause for type 2 diabetes? The GK rat paradigm. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2005;21:495–504. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Srinivasan K, Ramarao P. Animal models in type 2 diabetes research: An overview. Indian J Med Res. 2007;125:451–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chitaley K, Webb RC, Dorrance AM, Mills TM. Decreased penile erection in DOCA-salt and stroke prone-spontaneously hypertensive rats. Int J Impot Res. 2001;13(5 suppl):S16–S20. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carneiro FS, Nunes KP, Giachini FR, Lima VV, Carneiro ZN, Nogueira EF, Leite R, Ergul A, Rainey WE, Clinton Webb R, Tostes RC. Activation of the ET-1/ETA pathway contributes to erectile dysfunction associated with mineralocorticoid hypertension. J Sex Med. 2008;5:2793–2807. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tostes RC, Giachini FR, Carneiro FS, Leite R, Inscho EW, Webb RC. Determination of adenosine effects and adenosine receptors in murine corpus cavernosum. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322:678–685. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.122705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tamler R. Diabetes, obesity, and erectile dysfunction. Gend Med. 2009;6(1 suppl):4–16. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chitaley K, Kupelian V, Subak L, Wessells H. Diabetes, obesity and erectile dysfunction: Field overview and research priorities. J Urol. 2009;182:S45–S50. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.07.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janiszewski PM, Janssen I, Ross R. Abdominal obesity and physical inactivity are associated with erectile dysfunction independent of body mass index. J Sex Med. 2009;6:1990–1998. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hannan JL, Heaton JP, Adams MA. Recovery of erectile function in aging hypertensive and normotensive rats using exercise and caloric restriction. J Sex Med. 2007;4:886–897. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hannan JL, Maio MT, Komolova M, Adams MA. Beneficial impact of exercise and obesity interventions on erectile function and its risk factors. J Sex Med. 2009;6(3 suppl):254–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nangle MR, Cotter MA, Cameron NE. Protein kinase C beta inhibition and aorta and corpus cavernosum function in streptozotocin-diabetic mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;475:99–106. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)02113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perin PC, Maule S, Quadri R. Sympathetic nervous system, diabetes, and hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2001;23:45–55. doi: 10.1081/ceh-100001196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hedlund P, Ny L, Alm P, Andersson KE. Cholinergic nerves in human corpus cavernosum and spongiosum contain nitric oxide synthase and heme oxygenase. J Urol. 2000;164:868–875. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200009010-00064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cameron NE, Eaton SE, Cotter MA, Tesfaye S. Vascular factors and metabolic interactions in the pathogenesis of diabetic neuropathy. Diabetologia. 2001;44:1973–1988. doi: 10.1007/s001250100001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kobayashi T, Matsumoto T, Ooishi K, Kamata K. Differential expression of alpha2D-adrenoceptor and eNOS in aortas from early and later stages of diabetes in Goto-Kakizaki rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H135–H143. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01074.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morrison JF, Dhanasekaran S, Howarth FC. Neuropeptides in the rat corpus cavernosum and seminal vesicle: Effects of age and two types of diabetes. Auton Neurosci. 2009;146:76–80. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2008.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bockman CS, Gonzalez-Cabrera I, Abel PW. Alpha-2 adrenoceptor subtype causing nitric oxide-mediated vascular relaxation in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;278:1235–1243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sachidanandam K, Harris A, Hutchinson J, Ergul A. Microvascular versus macrovascular dysfunction in type 2 diabetes: Differences in contractile responses to endothelin-1. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2006;231:1016–1021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harris AK, Elgebaly MM, Li W, Sachidanandam K, Ergul A. Effect of chronic endothelin receptor antagonism on cerebrovascular function in type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294:R1213–R1219. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00885.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fulton D, Gratton JP, McCabe TJ, Fontana J, Fujio Y, Walsh K, Franke TF, Papapetropoulos A, Sessa WC. Regulation of endothelium-derived nitric oxide production by the protein kinase Akt. Nature. 1999;399:597–601. doi: 10.1038/21218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Musicki B, Kramer MF, Becker RE, Burnett AL. Inactivation of phosphorylated endothelial nitric oxide synthase (Ser-1177) by O-GlcNAc in diabetes-associated erectile dysfunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11870–11875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502488102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bitar MS, Wahid S, Mustafa S, Al-Saleh E, Dhaunsi GS, Al-Mulla F. Nitric oxide dynamics and endothelial dysfunction in type II model of genetic diabetes. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;511:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elabbady AA, Gagnon C, Hassouna MM, Begin LR, Elhilali MM. Diabetes mellitus increases nitric oxide synthase in penises but not in major pelvic ganglia of rats. Br J Urol. 1995;76:196–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1995.tb07674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chitaley K, Luttrell I. Strain differences in susceptibility to in vivo erectile dysfunction following 6 weeks of induced hyperglycemia in the mouse. J Sex Med. 2008;5:1149–1155. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nangle MR, Cotter MA, Cameron NE. Effects of the peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst, FeTMPyP, on function of corpus cavernosum from diabetic mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;502:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nangle MR, Cotter MA, Cameron NE. IkappaB kinase 2 inhibition corrects defective nitrergic erectile mechanisms in diabetic mouse corpus cavernosum. Urology. 2006;68:214–218. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.01.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nangle MR, Cotter MA, Cameron NE. The calpain inhibitor, A-705253, corrects penile nitrergic nerve dysfunction in diabetic mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;538:148–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.03.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park CS, Ryu SD, Hwang SY. Elevation of intracavernous pressure and NO-cGMP activity by a new herbal formula in penile tissues of aged and diabetic rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;94:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cellek S, Foxwell NA, Moncada S. Two phases of nitrergic neuropathy in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Diabetes. 2003;52:2353–2362. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.9.2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cellek S, Rodrigo J, Lobos E, Fernandez P, Serrano J, Moncada S. Selective nitrergic neurodegeneration in diabetes mellitus—A nitric oxide-dependent phenomenon. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;128:1804–1812. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jesmin S, Sakuma I, Salah-Eldin A, Nonomura K, Hattori Y, Kitabatake A. Diminished penile expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors at the insulin-resistant stage of a type II diabetic rat model: A possible cause for erectile dysfunction in diabetes. J Mol Endocrinol. 2003;31:401–418. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0310401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chitaley K. Type 1 and type 2 diabetic-erectile dysfunction: Same diagnosis (ICD-9), different disease? J Sex Med. 2009;6(3 suppl):262–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dey J, Shepherd MD. Evaluation and treatment of erectile dysfunction in men with diabetes mellitus. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:276–282. doi: 10.4065/77.3.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Siroky MB, Azadzoi KM. Vasculogenic erectile dysfunction: Newer therapeutic strategies. J Urol. 2003;170:S24–S29. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000075361.35942.17. (discussion S29–30) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kovanecz I, Ferrini MG, Vernet D, Nolazco G, Rajfer J, Gonzalez-Cadavid NF. Pioglitazone prevents corporal veno-occlusive dysfunction in a rat model of type 2 diabetes mellitus. BJU Int. 2006;98:116–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Manabe K, Heaton JP, Morales A, Kumon H, Adams MA. Pre-penile arteries are dominant in the regulation of penile vascular resistance in the rat. Int J Impot Res. 2000;12:183–189. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yamagishi S, Ueda S, Nakamura K, Matsui T, Okuda S. Role of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) in diabetic vascular complications. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:2613–2618. doi: 10.2174/138161208786071326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]