Abstract

Background

Enterococci rank among the leading causes of nosocomial infections. The failure to identify pathogen-specific genes in Enterococcus faecalis has led to a hypothesis where the virulence of different strains may be linked to strain-specific genes, and where the combined endeavor of the different gene-sets result in the ability to cause infection. Population structure studies by multilocus sequence typing have defined distinct clonal complexes (CC) of E. faecalis enriched in hospitalized patients (CC2, CC9, CC28 and CC40).

Results

In the present study, we have used a comparative genomic approach to investigate gene content in 63 E. faecalis strains, with a special focus on CC2. Statistical analysis using Fisher's exact test revealed 252 significantly enriched genes among CC2-strains. The majority of these genes were located within the previously defined mobile elements phage03 (n = 51), efaB5 (n = 34) and a vanB associated genomic island (n = 55). Moreover, a CC2-enriched genomic islet (EF3217 to -27), encoding a putative phage related element within the V583 genome, was identified. From the draft genomes of CC2-strains HH22 and TX0104, we also identified a CC2-enriched non-V583 locus associated with the E. faecalis pathogenicity island (PAI). Interestingly, surface related structures (including MSCRAMMs, internalin-like and WxL protein-coding genes) implicated in virulence were significantly overrepresented (9.1%; p = 0.036, Fisher's exact test) among the CC2-enriched genes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have identified a set of genes with potential roles in adaptation or persistence in the hospital environment, and that might contribute to the ability of CC2 E. faecalis isolates to cause disease.

Background

For many years, Enterococcus faecalis was considered as an intestinal commensal, which only sporadically caused opportunistic infections in immunocompromised patients. During the last thirty years, however, E. faecalis has gained notoriety as one of the primary causative agents of nosocomial infections [1,2], including urinary tract infections, endocarditis, intra-abdominal infections and bacteremia. The ability of E. faecalis to cause infection has been connected to inherent enterococcal traits, enabling the bacterium to tolerate diverse and harsh growth conditions. Moreover, several putative enterococcal virulence factors have been characterized (reviewed in [3]), and the role of these virulence factors in pathogenicity have been further established in various animal infection models [4-8] and cultured cell lines [9,10]. Reportedly, several of the proposed virulence determinants are enriched among infection-derived E. faecalis and/or E. faecium isolates, including esp (enterococcal surface protein) [11], hyl (hyaluronidase) [12], genes encoding collagen binding adhesins [13,14] and other matrix-binding proteins [15], and pilin loci [16,17]. On the other hand, recent studies on enterococcal pathogenicity have shown that a number of the putative virulence traits are present not only in infectious isolates but also in animal and environmental isolates [18-23]. This widespread distribution of putative virulence determinants in enterococcal isolates strongly suggest that enterococcal pathogenicity is not a result of any single virulence factor, but rather a more intricate process. Indeed, the virulence potential of the newly sequenced laboratory strain E. faecalis OG1RF was, despite its lack of several factors, comparable to that of the clinical isolate E. faecalis V583 [24]. Bourgogne et al. [24] proposed a scenario where the virulence of V583 and OG1RF may be linked to genes that are unique to each of the two strains, but where the combined endeavor of the different gene-sets result in the ability to cause infection.

Population structure studies of E. faecalis by multilocus sequence typing (MLST) have previously defined distinct clonal complexes (CC) of E. faecalis enriched in hospitalized patients (CC2, CC9, CC28 and CC40), designated high-risk enterococcal clonal complexes (HiRECCs) [25,26]. In one of our previous studies, we reported an overall correlation between MLST and Bayesian phylogenetic analysis of gene content as revealed by microarray-based comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) [27]. This observation led us to speculate whether the virulence of different HiRECCs may be due to lineage-specific gene sets. In the present study we have used the comparative genomics approach to further investigate variation in gene content within E. faecalis, with a special focus on CC2. This complex was chosen on the basis of previous Bayesian-based phylogenetic reconstruction [27]. CC2 is equivalent to the previously designated BVE complex, and comprises several clinically important E. faecalis isolates, including the first known beta-lactamase producing isolate HH22, the first U.S. vancomycin-resistant isolate V583, and pathogenicity island (PAI)-harboring clinical bacteremia isolate MMH594 [26,28,29]. This CC represents a globally dispersed hospital-associated lineage, and identification of CC2-enriched genes may unravel novel fitness factors implicated in survival and spread of E. faecalis clones in the hospital environment.

Results and discussion

Overall genomic diversity

To explore the genetic diversity among E. faecalis, BLAST comparison was performed with 24 publicly available sequenced draft genomes, including the two CC2-strains TX0104 (ST2), which is an endocarditis isolate, and HH22 (ST6; mentioned above) against the genome of strain V583, which is also a ST6 isolate. The number of V583 genes predicted to be present varied between 2385 (OG1RF) and 2831 (HH22) for the 24 strains (Additional file 1). In addition, we used CGH to investigate variation in gene content within 15 E. faecalis isolated in European hospital environments, with a special focus on a hospital-adapted subpopulation identified by MLST (CC2). Of the 3219 V583 genes represented on the array, the number of V583 orthologous genes classified as present ranged from 2359 (597/96) to 2883 (E4250). Analysis of the compiled data set (in silico and CGH), revealed a total of 1667 genes present in all strains, thus representing the E. faecalis core genome. None of the annotated V583 genes were found to be divergent in all the isolates analyzed.

Putative CC2-enriched elements

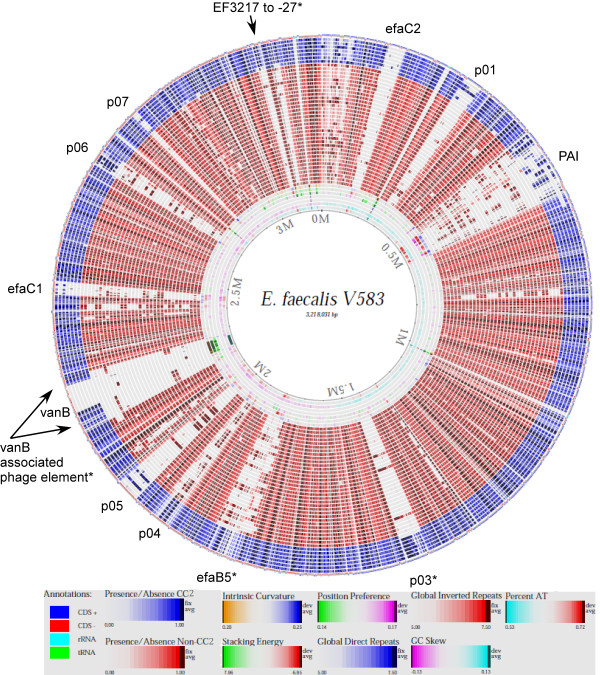

In a previous study, we identified a set of potential pathogen-specific genes, which were entirely divergent in a collection of commensal baby isolates [27]. None of these genes were found to be present in all hospital-related isolates analyzed in the present study, neither was any gene found to be unique to any HiRECC. In order to identify genes specifically enriched among strains belonging to CC2, data from the present study were supplemented with hybridization data from an additional 24 strains of various origins ([27,30] and M. Solheim, unpublished data). The additional data sets were obtained by hybridization to the same array as described above. All together, data from a total of 63 strains were analyzed, in addition to V583 (Table 1). A genome-atlas presentation of the gene content in all the strains analyzed by CGH compared to the V583 genome is shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Enterococcus faecalis isolates used in this study. CC; clonal complex, CGH; comparative genomic hybridization, MLST; multilocus sequence typing, S; singleton, ST; sequence type.

| Strain | Year | Country | Source | MLST | Application | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST | CC | ||||||

| TX0104 | USA | Clinical | 2 | 2 | In silico | [65] | |

| 609/96 | 1996 | Poland | Wound | 6 | 2 | CGH, PCR | [25] |

| 372-56 | 2007 | Norway | Blood | 6 | 2 | CGH, PCR | |

| 226B | 2005 | Norway | Feces | 6 | 2 | PCR | [27] |

| 368-42 | 2007 | Norway | Blood | 6 | 2 | PCR | |

| 442/05 | 2005 | Poland | CSF | 6 | 2 | PCR | [25] |

| E1828 | 2001 | Spain | Blood | 6 | 2 | PCR | [26] |

| MMH594 | 1985 | USA | Clinical | 6 | 2 | CGHC, PCR | [66] |

| V583 | 1989 | USA | Blood | 6 | 2 | CGH, PCR | [67] |

| 158B | 2005 | Norway | Feces | 6 | 2 | CGHB, PCR | [27] |

| HH22 | ≤1982 | USA | Urine | 6 | 2 | In silico | [29] |

| LMGT3303 | 6 | 2 | CGHD, PCR | ||||

| E1834 | 2001 | Spain | Blood | 51 | 2 | CGH, PCR | [26] |

| E4250 | 2007 | Netherlands | Feces | 183 | 2 | CGH, PCR | |

| HIP11704 | 2002 | USA | Clinical | 4 | 4 | In silico | [68] |

| E1841 | 2001 | Spain | Blood | 9 | 9 | CGH, PCR | [26] |

| Vet179 | 1999 | Norway | Dog_urine | 9 | 9 | CGHD, PCR | [69] |

| CH188 | 1980s | USA | Liver | 9 | 9 | In silico | [70] |

| E1807 | 2002 | Spain | Feces | 17 | 9 | CGH, PCR | [26] |

| X98 | 1934 | Feces | 19 | 19 | In silico | [71] | |

| OG1RF | ≤1975 | USA | Oral | 1 | 21 | CGHC, PCR | [72] |

| E1960 | 2001 | Spain | Feces | 8 | 21 | CGH, PCR | [26] |

| T8 | ≤1992 | Japan | Urine | 8 | 21 | In silico | [73] |

| 2426/03 | 2003 | Poland | Feces | 21 | 21 | CGH, PCR | [25] |

| ATCC 29200 | ≤1974 | Canada | Urogenital | 21 | 21 | In silico | [74] |

| T1 | ≤1950 | 21 | 21 | In silico | [73] | ||

| LMGT3406 | 1999 | Denmark | Poultry_feces | 22 | 21 | CGHD, PCR | |

| 111A | 2005 | Norway | Feces | 161 | 21 | CGHB, PCR | [27] |

| TX1322 | USA | 161 | 21 | In silico | [65] | ||

| 3339/04 | 2004 | Poland | Blood | 23 | 25 | CGH, PCR | [25] |

| UC11/46 | Finland | Feces | 97 | 25 | CGH, PCR | [19] | |

| 189 | 2002-2003 | Norway | Feces | 162 | 25 | CGHB, PCR | [27] |

| Symbioflor 1 | Germany | Feces | 248 | 25 | CGHC, PCR | [75] | |

| T2 | ≤1992 | Japan | Urine | 11 | 28 | In silico | [73] |

| E1188 | 1997 | Greece | Blood | 28 | 28 | CGH, PCR | [26] |

| 383/04 | 2004 | Poland | Blood | 87 | 28 | CGH, PCR | [25] |

| E1052 | Netherlands | Feces | 30 | 30 | CGHD, PCR | ||

| 85 | 2008 | Norway | Feces | 30 | 30 | CGHB, PCR | [27] |

| 597/96 | 1996 | Poland | Ulcer | 40 | 40 | CGH, PCR | [25] |

| LMGT2333 | Iceland | Fish | 40 | 40 | CGHD, PCR | ||

| JH1 | ≤1974 | United Kingdom | Clinical | 40 | 40 | In silico | [76] |

| LMGT3209 | Greece | Food_cheese | 40 | 40 | CGHD, PCR | ||

| 1645 | 2007 | Denmark | Blood | 220 | 40 | CGH, PCR | |

| 29C | 2004 | Norway | Feces | 44 | 44 | CGHB, PCR | [27] |

| 92A | 2005 | Norway | Feces | 44 | 44 | CGHB | [27] |

| DS5 | ≤1974 | 55 | 55 | In silico | [77] | ||

| E2370 | Hungary | Wound | 16 | 58 | CGH, PCR | ||

| 105 | 2002-2003 | Norway | Feces | 16 | 58 | CGHB, PCR | [27] |

| D6 | Denmark | Pig | 16 | 58 | In silico | [31] | |

| E1Sol | 1960s | Solomon Islands | Feces | 93 | 93 | In silico | [78] |

| Merz96 | 2002 | USA | Blood | 103 | 103 | In silico | [79] |

| R712 | USA | Clinical | 103 | 103 | In silico | [65] | |

| S613 | USA | Clinical | 103 | 103 | In silico | [65] | |

| LMGT3405 | 1999 | Denmark | Poultry_feces | 116 | 116 | CGHD, PCR | |

| LMGT3407 | 1999 | Denmark | Poultry_feces | 34 | 121 | CGHD, PCR | |

| Fly1 | 2005 | USA | Drosophila | 101 | 101A | In silico | [31] |

| Vet138 | 1998 | Norway | Dog_ear | 164 | 119A | CGHD, PCR | [69] |

| 82 | 2008 | Norway | Poultry_feces | 65 | S | CGHD, PCR | |

| T11 | ≤1992 | Japan | Urine | 65 | S | In silico | [73] |

| 62 | 2002-2003 | Norway | Feces | 66 | S | CGHB, PCR | [27] |

| ATCC 4200 | 1926 | Blood | 105 | S | In silico | ||

| AR01/DG | 2001 | New Zealand | Dog | 108 | S | In silico | [80] |

| 266 | 2002-2003 | Norway | Feces | 163 | S | CGHB, PCR | [27] |

| LMGT3143 | Spain | Animal_wood pigeon | 165 | S | CGHD, PCR | ||

| LMGT3208 | Greece | Food_cheese | 166 | S | CGHD, PCR | ||

| 84 | 2008 | Norway | Poultry_feces | 249 | S | CGHD, PCR | |

| TuSoD ef11 | USA | Clinical | 364 | S | In silico | [65] | |

AClonal complexes were no predicted founder was proposed by eBURST.

BIn Solheim et al. 2009.

CIn Vebø et al. 2010.

DMS, unpublished work.

Figure 1.

Genome-atlas presentation of CGH data compared to the V583 genome and arranged by clonal relationship according to MLST. From inner to outer lanes: 1) percent AT, 2) GC skew, 3) global inverted repeats, 4) global direct repeats, 5) position preference, 6) stacking energy, 7) intrinsic curvature, 8) 189, 9) LMGT3208, 10) LMGT3407, 11) 92A, 12) 29C, 13) E1960, 14) 111A, 15) 105, 16) E2370, 17) 84, 18) 383/04, 19) E1188, 20) Vet179, 21) EF1841, 22) E1807, 23) LMGT3143, 24) LMGT3405, 25) OG1RF, 26) 2426/03, 27) LMGT3406, 28) 85, 29) E1052, 30) 1645, 31) LMGT3209, 32) LMGT2333, 33) 597/96, 34) 62, 35) Vet138, 36) 266, 37) UC11/96, 38) Symbioflor 1, 39) 3339/04, 40) 82, 41) E1834, 42) E4250, 43) LMGT3303, 44) 158B, 45) MMH594, 46) 372-56, 47) 609/96 and 48) annotations in V583. Elements enriched in CC2-strains are indicated with an asterisk.

By Fisher's exact testing (q < 0.01), 252 genes were found to be more prevalent among CC2-strains than in non-CC2-strains (Additional file 2). The CC2-enriched genes included large parts of phage03 (p03; n = 51), efaB5 (n = 34) and a phage-related region identified by McBride et al. [31](EF2240-82/EF2335-51; n = 55), supporting the notion that the p03 genetic element may confer increased fitness in the hospital environment [27]. Indeed, prophage-related genes constituted a predominant proportion of the CC2-enriched genes (55.5%; p < 2.2e-16, Fisher's exact test). Interestingly, the Tn916-like efaB5 element has previously also been suggested to play a role in niche adaptation (Leavis, Willems et al. unpublished data): CGH analysis identified an efaB5-orthologous element in E. faecium that appeared to be common for HiRECC E. faecalis and CC17 E. faecium, a hospital-adapted subpopulation identified by MLST. To further confirm the presence of the relevant MGEs in E. faecalis, we used PCR combining internal primers with primers targeting the genes flanking p03, efaB5 and the vanB-associated phage-related element in V583, to monitor conserved V583 junctions on either side of the elements in 44 strains (Table 1). Seven strains contained the junctions on both sides of p03, of which six strains were CC2-strains. Eleven strains were positive for the junctions on both sides of efaB5, including nine CC2-strains, while thirteen strains gave positive PCR for both junctions of the phage-related element surrounding vanB, of which eleven strains belonged to CC2 (Additional file 3). These results substantiate the theory of p03, efaB5 and the vanB-associated phage as CC2-enriched elements.

A total of 178 of the 252 putative CC2-enriched genes identified here, were associated with previously defined MGEs identified in V583 [32]. In addition to p03, efaB5 and the vanB-surrounding phage element, these included p01 (n = 5), PAI (n = 7), p04 (n = 21), p06 (n = 1) and pTEF1 and pTEF2 (n = 5) (Additional file 2). In addition, a ten-gene cluster (EF3217 to -27) with significant GC skew compared to the genome-average (31.6 and 37.4%, respectively), was found to be significantly more frequent in strains belonging to CC2 than in non-CC2 strains. The deviation in GC content suggests that this genetic element may also be of foreign origin. This notion was further supported by the sequence similarities of several of the genes with known phage-related transcriptional regulators (EF3221, EF3223 and EF3227). Moreover, EF3221 to -22 showed high degree of identity (>85%) to EfmE980_2492 to -93 of the newly sequenced Enterococcus faecium E980 [33]. EfmE980_2492 holds a domain characteristic of the aspartate aminotransferase superfamily of pyridoxal phosphate-dependent enzymes. Interestingly, EF3217 encodes a putative helicase, while EF3218 encodes a putative MutT protein, both with implications in DNA repair [34,35]. A potential role of these genes in protection against oxidative DNA damage induced in the hospital environment and during infection is plausible. To further investigate the distribution of EF3217 to -27 in E. faecalis, 44 strains were screened by PCR (Additional file 3): 10 CC2-strains held all ten genes, while 19 strains including two CC2-strains were devoid of the entire element. Moreover, 2 strains contained EF3225 only, 3 strains contained EF3217 to -18, while 8 strains, including OG1RF, contained EF3226 only. The two latter patterns of presence and divergence of EF3217 to -27 were also obtained with BLASTN analysis of TX0104 and OG1RF, respectively, corroborating that these are indeed genuine polymorphisms in this locus. Notably, in the OG1RF genome five more genes (OG1RF_0214 to -18) are also located between the homologs of EF3216 and EF3230 [24], suggesting this locus may represent a hot spot for insertions. Partial sequencing across the junction between EF3216 and EF3230 suggested that several of the non-CC2 strains carry genes homologous to OG1RF_0214 to -18 in this locus (results not shown).

Mobile DNA constitutes a substantial fraction of the E. faecalis V583 genome and transfer of MGEs and transposons thus plays an important role in the evolution of E. faecalis genomes [32]. The large pool of mobile elements also represents an abundant source of pseudogenes, as indel events occurring within coding regions often render genes nonfunctional. To verify the expression of the CC2-enriched genes, we correlated the list of enriched genes with data from two transcriptional analyses performed in our laboratory with the same array as used in the CGH experiment described in present study ([30] and Solheim, unpublished work). Transcription was confirmed for all but fifteen of the CC2-enriched genes (results not shown), thus validating the expression of these reading frames. The fifteen genes, for which no transcripts were detected, were mainly located within efaB5 and phage04.

A constraint of the comparative genomic analyses presented here, is that the comparison of gene content is based on a single reference strain only (V583). To compensate, we conducted a CC2 pangenome analysis with the draft genomes of CC2-strains HH22 and TX0104 to identify putative CC2-enriched non-V583 genes. The pangenome analysis identified a total of 298 non-V583 ORFs in the HH22 and TX0104 (Additional file 4). Among these ORFs, one gene cluster was identified as particularly interesting (Fisher's exact; Additional file 4 and Figure 2). Notably, HMPREF0348_0426 in TX0104 represented the best BLAST hit for all the three ORFs HMPREF0364_1864 to -66 in HH22, suggesting discrepancy in annotation between the two strains. Sequencing across the gap between contig 00034 and contig 00035 in TX0104 confirmed that HMPREF0348_0427 and HMPREF0348_0428 represent the two respective ends of a gene homologous to HMPREF0346_1863 in HH22. (Additional file 5). The presence of the putative non-V583 CC2-enriched gene cluster among E. faecalis was further elucidated by PCR in our collection of strains (Additional file 3). Strains were screened for the presence of three individual genes (HMPREF0346_1861, HMPREF0346_1864 and HMPREF0346_1868) and the entire element, with primers hmpref0346_1868-F and hmpref0346_1861-R. Fisher's exact testing (q < 0.01) on the basis of the PCR data confirmed that the gene cluster was significantly enriched among CC2. Comparative sequence analysis of the flanking regions suggests that the gene cluster is located in the HH22 and TX0104 versions of the E. faecalis pathogenicity island [36]. Recently, a microarray-based assessment of PAI-content in a set of clinical E. faecalis isolates revealed high degree of variation within the island, and an evidently modular evolution of the PAI [37], which would be consistent with acquisition by an indel event of this locus in the PAI of TX0104, HH22 and other positive CC2-strains.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of a putative non-V583 CC2-enriched gene cluster, as annotated in the Enterococcus faecalis HH22 and TX0104 draft genomes (GenBank accession numbers ACIX00000000 and ACGL00000000, respectively). The EF-numbers of flanking genes indicate the insert site location compared to the E. faecalis V583 pathogenicity island.

CC2-enriched surface-related structures

Lepage et al. [38] have previously identified eight genes as potential markers for the V583/MMH594-lineage, of which all except one gene (EF2513) are found among the CC2-enriched genes in this study. Interestingly, several of these genes were later assigned to a recently classified family of surface proteins, with a C-terminal WxL domain, proposed to form multi-component complexes on the cell surface [39,40]. Siezen et al. [40] termed these genes cell-surface complex (csc) genes and postulated a role in carbon source acquisition. Independently, Brinster et al. [39] showed that WxL domains are involved in peptidoglycan-binding. A total of nine WxL protein-coding genes, divided into three clusters (EF2248 to -54, EF3153 to -55 and EF3248 to -53), were identified as putative CC2-enriched genes in the present study. Note that EF3153 to - 55 does not represent a complete csc gene cluster, as not all four csc gene families (cscA - cscD) are present in the cluster [40]. Interestingly, the OG1RF genome sequence revealed homologues loci encoding WxL-proteins corresponding to the gene clusters EF3153 to -55 and EF3248 to -53 in V583 (50-75% sequence identity) [24]. Such homologs may possibly explain the divergence observed between CC2 and non-CC2-strains in the present study. Indeed, BLAST analysis with the OG1RF sequences against the E. faecalis draft genomes suggested that the OG1RF_0209-10 and OG1RF_0224-25 are widely distributed among non-CC2 E. faecalis. Given the putative function in carbon metabolism, the observed sequence variation may be related to substrate specificity.

In addition to the WxL domain, EF2250 also encodes a domain characteristic for the internalin family [39]. Internalins are characterized by the presence of N-terminal leucine-rich repeats (LRRs). The best characterized bacterial LRR proteins are InlA and InlB from Listeria monocytogenes, known to trigger internalization by normally non-phagocytic cells [41]. Two internalin-like proteins were identified in E. faecalis V583 (EF2250 and elrA (EF2686)) [41,42]. Recently, Brinster et al. [42] presented evidence of that ElrA play a role in E. faecalis virulence, both in early intracellular survival in macrophages and by stimulating the host inflammatory response through IL-6 induction. Moreover, by quantitative real-time PCR Shepard and Gilmore [43] found that elrA was induced in E. faecalis MMH594 during exponential growth in serum and during both exponential and stationary growth in urine. Contradictory data have, however, been published for this and other strains using different methods [42,44]. Although it is tempting to speculate that EF2250 contributes to the interaction with the mammalian host, the role of internalins in E. faecalis pathogenesis is still not understood, and it may therefore be premature to extrapolate function solely on the basis of shared structural domains.

Glycosyl transferase family proteins are involved in the formation of a number of cell surface structures such as glycolipids, glycoproteins and polysaccharides [45]. E. faecalis is in possession of several capsular polysaccharides [46-48], with Cps and Epa being the best characterized. The epa (enterococcal polysaccharide antigen) cluster represents a rhamnose-containing polysaccharide which was originally identified in E. faecalis OG1RF [46]. The version of the epa cluster found in the V583 genome contains an insertion of four genes (EF2185 to -88) compared to OG1RF. This insertion appeared to be enriched among CC2. While EF 2185 and EF2187 encodes transposases of the IS256 family, the two remaining genes showed 100% identity to the two respective ends of a racemase domain protein in E. faecalis TX0104. Neighboring the epa cluster, two glycosyl transferases (EF2170 and EF2167) proposed as potential virulence factors [32], are part of a three operon locus (EF2172 to -66), possibly associated with lipopolysaccharide production. Five of the genes within this locus were also found to be enriched among CC2 in the present study.

Paulsen et al. [32] also listed other putative surface-exposed virulence genes, including a choline-binding protein (CBP; EF2662) and a putative MSCRAMM (microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules; EF2347) that based on our analysis were found to be enriched in CC2. A role of CBPs in pneumococcal colonization and virulence has been established [49,50]. A number of putative MSCRAMMs have been identified in E. faecalis [51], however, only Ace (adhesion of collagen from E. faecalis; EF1099) has been characterized in detail: Ace was shown to mediate binding to collagen (type I and IV), dentin and laminin [52-54]. Lebreton et al. [55] recently presented evidence of an in vivo function of Ace in enterococcal infections other than involvement in the interaction with extracellular matrix. It was demonstrated that an ace deletion mutant was significantly impaired in virulence, both in an insect model and in an in vivo-in vitro murine macrophage models. The authors suggested that Ace may promote E. faecalis phagocytosis and that it may also be possible that Ace is involved in survival of enterococci inside phagocytic cells. Also the structurally related MSCRAMM, Acm, found in E. faecium was recently reported to contribute to the pathogenesis of this bacterium [56].

Mucins are high molecular weight glycoproteins expressed by a wide variety of epithelial cells, including those of the gastrointestinal tract, and located at the interface between the cell and the surrounding environment [57]. The binding of bacteria to mucins through mucin-binding domain proteins is thought to promote colonization [58]. Diversity in the carbohydrate side chains creates a significant heterogeneity among mucins of different origin (e.g. different organisms or body sites), facilitating bacterial attachment to epithelial cells [58]. The non-V583 CC2-enriched gene cluster identified through in silico analysis in the present study harboured an ORF (HMPREF0346_1863 and HMPREF0348_0427/HMPREF0348_0428 in HH22 and TX0104, respectively) with homology to known mucin-binding domain proteins.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have identified a set of genes that appear to be enriched among strains belonging to CC2. Since a significant proportion (9.1%; p = 0.036, Fisher's exact test) of these genes code for proteins associated with cell surface structures, absence of or divergence in these loci may lead to antigenic variation. Indeed, both MSCRAMMs and internalins have been identified as potential antigens of E. faecalis or other Gram-positive bacteria [59-61]. It is noteworthy that the genes encoding any of the established enterococcal virulence factors were not among the CC2-enriched genes. Surface structures that promote adhesion of pathogenic bacteria to human tissue are also promising targets for creation of effective vaccines. However, functional studies of the individual CC2-enriched genes are required in order to distinguish their implications in enterococcal virulence.

Methods

Bacterial strain and growth conditions

Bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. faecalis strains were grown overnight (ON) in brain heart infusion broth (BHI; Oxoid) at 37° without shaking. All the strains have previously been sequence typed by the MLST scheme proposed by Ruiz-Garbajosa et al. [26].

Comparative genomic hybridization

Microarrays

The microarray used in this work has been described previously [27]. The microarray design has been deposited in the ArrayExpress database with the accession number A-MEXP-1069 and A-MEXP-1765.

DNA isolation

Genomic DNA was isolated by using the FP120 FastPrep bead-beater (BIO101/Savent) and the QiaPrep MiniPrep kit (Qiagen) as previously described [27].

Fluorescent labeling and hybridization

Fifteen hospital-associated E. faecalis strains were selected for CGH based on their representation of MLST sequence types (STs) belonging to major CCs and potential HiRECCs, with a special focus on CC2, and their variety of geographical origins within Europe. Genomic DNA was labeled and purified with the BioPrime Array CGH Genomic labeling System (Invitrogen) and Cyanine Smart Pack dUTP (PerkinElmer Life Sciences), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Purified samples were then dried, prior to resuspension in 140 μl hybridization solution (5 × SSC, 0.1% (w/v) SDS, 1.0% (w/v) bovine serum albumin, 50% (v/v) formamide and 0.01% (w/v) single-stranded salmon sperm DNA) and hybridized for 16 h at 42°C to the E. faecalis oligonucleotide array in a Tecan HS 400 pro hybridization station (Tecan). Arrays were washed twice at 42°C with 2 × SSC + 0.2% SDS, and twice at 23°C with 2 × SSC, followed by washes at 23°C with 1) 0.2 × SSC and 2) H2O. Two replicate hybridizations (dye-swap) were performed for each test strain. Hybridized arrays were scanned at wavelengths of 532 nm (Cy3) and 635 nm (Cy5) with a Tecan scanner LS (Tecan). Fluorescent intensities and spot morphologies were analyzed using GenePix Pro 6.0 (Molecular Devices), and spots were excluded based on slide or morphology abnormalities. All water used for the various steps of the hybridization and for preparation of solutions was filtered (0.2 μM) MilliQ dH20.

Data analysis

Standard methods in the LIMMA package [62] in R http://www.r-project.org/, available from the Bioconductor http://www.bioconductor.org were employed for preprocessing and normalization. Within-array normalization was first conducted by subtracting the median from the log-ratios for each array. A standard loess-normalization was then performed, where smoothing was based only on spots with abs(log-ratio) < 2.0 to avoid biases due to extreme skewness in the log-ratio distribution. For the determination of present and divergent genes a method that predicts sequence identity based on array signals was used, as described by Snipen et al. [63]. A threshold of 0.75 was used in order to obtain a categorical response of presence or divergence, i. e. genes with Sb-value > 0.75 were classified as present, while genes with Sb-value < 0.75 were classified as divergent. Genes with Sb-value = 0.75 remained unclassified. All genes were tested for significant enrichment among the CC2-strains by using the Fisher's exact test.

Microarray data accession number

The microarray data have been deposited in the ArrayExpress database with the series accession number E-TABM-905.

Polymerase chain reaction

The presence of selected genes was verified by means of polymerase chain reactions (PCR). A similar approach was also applied to investigate the presence of selected mobile genetic elements (MGEs). Primers targeting the genes flanking the MGEs were combined with internal primers to monitor the presence of the junctions on either side of each MGE. PCR was carried out in 20 μl reaction volumes containing 1× buffer, 250 μM of each deoxynucleotide triphosphate and 1 U DyNAZyme II polymerase (Finnzymes). The reaction conditions included an initial denaturation step at 95°C and 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 56-60°C for 30 s and 72°C for 1-5 min, followed by a final extension step at 72°C for 7 min. The primers used in this study are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study.

| Target gene | Primer sequences (5' → 3') | Amplicon size (bp) | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| ef1415 | F:TGTTGCGGTTTCTGCATTAG | 2818 | PCR on junction between EF1415 and EF1417 |

| ef1417 | R:GCATCTCGATAGACAATTCG | PCR on junction between EF1415 and EF1417 | |

| ef1489 | F:GAATCGAACTAGCATTTTTGGG | 465 | PCR on junction between EF1489 and EF1490 |

| ef1490 | R:ATGGAACGAACCATTGGAAA | PCR on junction between EF1489 and EF1490 | |

| ef1843 | F:GGAGCCGTTAGACAGACAGC | 2457 | PCR on junction between EF1843 and EF1847 |

| ef1847 | R:GCTTGCTTTACAGCCTCAAGA | PCR on junction between EF1843 and EF1847 | |

| ef1895 | F:GCACAACAAATTTCAATTCCA | 4573 | PCR on junction between EF1895 and EF1898 |

| ef1898 | R:ATTGAAGTGGTTCGCTACGG | PCR on junction between EF1895 and EF1898 | |

| ef2239 | F:AACTGCTGTCAAGCGTAGCA | 1252 | PCR on junction between EF2239 and EF2240 |

| ef2240 | R:TGTGGCATTTTGGACTGTTG | PCR on junction between EF2239 and EF2240 | |

| ef2350 | F:ATAACTGAGTGATTTTCACAATTGC | 654 | PCR on junction between EF2350 and EF2352 |

| ef2352 | R:GATCCGTGGAAGTTCCTCAA | PCR on junction between EF2350 and EF2352 | |

| ef3216 | F:TCGGCGTTGAAGACTATGAA | - | Sequencing of junction between EF3216 and EF3230 |

| ef3217 | F:ATTGGGAATGACGGCTACAC R:TTGCGTATTTCGCAGCATAA |

499 | PCR |

| ef3218 | F:TCGCGTAGTAGGAGCAATCA R:TTTTGTTCAGTTCCCACACCT |

396 | PCR |

| ef3220 | F:AGCTTTTGGCGAAGGAGATT R:TTTATTGCGGGTTCCTCAGT |

495 | PCR |

| ef3221 | F:TGAACGAAAATGAAGGTGGT R:TCATCAATCTCCAACGCATC |

196 | PCR |

| ef3222 | F:CAAAGAAGAATCAGCCGATTAAA R:ATATTTGGGCATTTGCATGG |

183 | PCR |

| ef3223 | F:AATTGGGAAAAAGGGGTCAG R:TTCGTGATCTGCTTGTTGTTCT |

501 | PCR |

| ef3224 | F:GTTGGGCTGGACGTATGAAT R:TGTGGCTTTATAGGCTGTAGCA |

214 | PCR |

| ef3225 | F:ATTACTTCACCGCCCATGAC R:CGCTGGAAGTCTGCTCTTG |

474 | PCR |

| ef3226 | F:GATGATTTAACCGCACAAGGA R:TTTTTATTTCGAGCGGATGC |

499 | PCR |

| ef3227 | F:ACAGGAAGCCATTCACAAACT R:CTGATTCGTGGAAGTCCAACT |

162 | PCR |

| ef3230 | R:TCCTGACTTCCGTTCTGCTT | - | Sequencing of junction between EF3216 and EF3230 |

| hmpref0346_1861 | F:CGAGTTAGAGGAAGCGTTGG | 630 | PCR |

| R:CCAGACAATTTGGGCGTACT | |||

| hmpref0346_1864 | F:GAAATTTTCTGAAAGTGAAGACAAGA | 299 | PCR |

| R:TGATTAGCAGTCACAACAGCAA | |||

| hmpref0346_1868 | F:TGTACACAAGCTACCCGGATT | 538 | PCR |

| R:TTCCCACCTGCGTCTATTTT | |||

| hmpref0348_0427 | R:GAGACTTCAACCACTCCACAAAAACC | - | Sequencing of gap between contig00034-35 in TX0104 |

| hmpref0348_0428 | F:CCTGTAGAAGTATTGTCCATTTTAACGCTATC | Sequencing of gap between contig00034-35 in TX0104 |

Validation of microarray data by sequencing

Sequencing was performed using the ABI Prism Big dye Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit (Applied Biosystems) in an ABI PrismTM 3100 Genetic Analyzer and primers listed in Table 2.

In silico comparison of E. faecalis draft genomes

Whole genome blast comparison against the V583 reference genome was conducted for 24 E. faecalis strains whose draft genomes were publicly available (GenBank accession numbers in parenthesis; Table 1): E. faecalis ARO1/DG (ACAK01000000); E. faecalis ATCC 4200 (ACAG01000000); E. faecalis ATCC 29200 (ACOX00000000); E. faecalis CH188 (ACAV01000000); E. faecalis D6 (ACAT01000000); E. faecalis DS5 (ACAI01000000); E. faecalis E1Sol (ACAQ01000000); E. faecalis Fly1 (ACAR01000000): E. faecalis HIP11704 (ACAN01000000); E. faecalis HH22 (ACIX00000000); E. faecalis JH1 (ACAP01000000); E. faecalis Merz96 (ACAM01000000); E. faecalis OG1RF (ABPI01000001); E. faecalis R712 (ADDQ00000000); E. faecalis S613 (ADDP00000000); E. faecalis T1 (ACAD01000000); E. faecalis T2 (ACAE01000000); E. faecalis T3 (ACAF01000000); E. faecalis T8 (ACOC01000000); E. faecalis T11 (ACAU01000000); E. faecalis TuSoD ef11(ACOX00000000); E. faecalis TX0104 (ACGL00000000); E. faecalis TX1322 (ACGM00000000); E. faecalis X98 (ACAW01000000) [64,65], as follows: the annotated V583 genes were blasted (BLASTN) against each genome, and presence and divergence was predicted based on a score calculated as number of identical nucleotides divided by the length of the query gene. Genes obtaining a score >0.75 were predicted to be present.

CC2 pangenome content analysis

Among the newly released E. faecalis draft genomes were two CC2-strains; HH22 and TX0104. In order to extend the list of CC2-enriched genes beyond V583, we conducted a BLAST search using the annotated genes of these two strains as queries against the full genome sequences of the other draft genomes. Again, a cutoff of 75% identity to the query was used to distinguish present from divergent genes.

Authors' contributions

MS conceived and designed the study, carried out the experimental work, analyzed the data, assisted in the bioinformatic analysis and drafted the manuscript. MCB performed the experimental work and assisted in critical review of the manuscript. LS contributed analysis tools, performed the statistical and bioinformatic analyses and assisted in the critical review of the manuscript. RJLW conceived and designed the study, contributed material and assisted in critical review of the manuscript. IFN conceived the study, contributed material and assisted in critical review of the manuscript. DAB participated in the design and coordination of the study, performed bioinformatic analysis and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

BLAST comparison of E. faecalis genomes. Data from BLAST comparison of 24 E. faecalis draft genomes with the annotated genes of strain V583.

V583 genes which were identified as significantly enriched among CC2-strains in the present study. A list of V583 genes which were identified as significantly enriched among CC2-strains in the present study.

PCR screening. An overview of results from PCR screening of a collection of E. faecalis isolates.

Enrichment analysis of CC6 non-V583 genes by Fisher's exact test. An overview of the presence non-V583 genes in 24 E. faecalis draft genomes CC6 including data from enrichment analysis by Fisher's exact test.

Amino acid alignment of HMPREF0346_1863 in Enterococcus faecalis HH22 and its homologue in E. faecalis TX0104. An amino acid alignment of HMPREF0346_1863 in Enterococcus faecalis HH22 and its homologue in E. faecalis TX0104.

Contributor Information

Margrete Solheim, Email: margrete.solheim@umb.no.

Mari C Brekke, Email: mari.brekke@umb.no.

Lars G Snipen, Email: lars.snipen@umb.no.

Rob JL Willems, Email: rwillems@umcutrecht.nl.

Ingolf F Nes, Email: ingolf.nes@umb.no.

Dag A Brede, Email: dag.anders.brede@umb.no.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the European Union 6th Framework Programme "Approaches to Control multi-resistant Enterococci: Studies on molecular ecology, horizontal gene transfer, fitness and prevention" (LSHE-CT-2007-037410). We gratefully acknowledge the following researchers for kindly providing strains to this study: Dr. Lars B. Jensen, Dr. Barbara E. Murray, Dr. Ewa Sadowy, Dr. Arnfinn Sundsfjord and Dr. Atte von Wright. We also acknowledge Dr. David W. Ussery for contributing bioinformatic tools and assisting in construction of the genome-atlas and Hallgeir Bergum at The Norwegian Microarray Consortium for printing of the microarray slides. Finally, we acknowledge the tremendous genome sequencing efforts made by Dr. Michael S. Gilmore and coworkers at the Stephens Eye Research Institute and Harvard Medical School, the Broad Institute, and the Human Microbiome-project represented by Dr. Barbara E. Murray and co-workers at Baylor College of Medicine, Dr. George Weinstock and coworkers at Washington University, and Dr. S. Shrivastava and co-workers at the J. Craig Venter Institute.

References

- Richards MJ, Edwards JR, Culver DH, Gaynes RP. Nosocomial infections in combined medical-surgical intensive care units in the United States. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2000;21(8):510–515. doi: 10.1086/501795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisplinghoff H, Bischoff T, Tallent SM, Seifert H, Wenzel RP, Edmond MB. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(3):309–317. doi: 10.1086/421946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock LE, Gilmore MS. In: Gram-positive pathogens. Fischetti VA, Novick RP, Ferretti JJ, Portnoy DA, Rood JI, editor. Washington DC: ASM Press; 2006. Pathogenicity of enterococci; pp. 299–311. [Google Scholar]

- Shankar N, Lockatell CV, Baghdayan AS, Drachenberg C, Gilmore MS, Johnson DE. Role of Enterococcus faecalis surface protein Esp in the pathogenesis of ascending urinary tract infection. Infect Immun. 2001;69(7):4366–4372. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.7.4366-4372.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow JW, Thal LA, Perri MB, Vazquez JA, Donabedian SM, Clewell DB, Zervos MJ. Plasmid-associated hemolysin and aggregation substance production contribute to virulence in experimental enterococcal endocarditis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37(11):2474–2477. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.11.2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jett BD, Jensen HG, Nordquist RE, Gilmore MS. Contribution of the pAD1-encoded cytolysin to the severity of experimental Enterococcus faecalis endophthalmitis. Infect Immun. 1992;60(6):2445–2452. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.6.2445-2452.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlievert PM, Gahr PJ, Assimacopoulos AP, Dinges MM, Stoehr JA, Harmala JW, Hirt H, Dunny GM. Aggregation and binding substances enhance pathogenicity in rabbit models of Enterococcus faecalis endocarditis. Infect Immun. 1998;66(1):218–223. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.218-223.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh KV, Nallapareddy SR, Sillanpaa J, Murray BE. Importance of the collagen adhesin ace in pathogenesis and protection against Enterococcus faecalis experimental endocarditis. PLoS Pathog. p. e1000716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kreft B, Marre R, Schramm U, Wirth R. Aggregation substance of Enterococcus faecalis mediates adhesion to cultured renal tubular cells. Infect Immun. 1992;60(1):25–30. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.1.25-30.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmsted SB, Dunny GM, Erlandsen SL, Wells CL. A plasmid-encoded surface protein on Enterococcus faecalis augments its internalization by cultured intestinal epithelial cells. J Infect Dis. 1994;170(6):1549–1556. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.6.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar V, Baghdayan AS, Huycke MM, Lindahl G, Gilmore MS. Infection-derived Enterococcus faecalis strains are enriched in esp, a gene encoding a novel surface protein. Infect Immun. 1999;67(1):193–200. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.1.193-200.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice LB, Carias L, Rudin S, Vael C, Goossens H, Konstabel C, Klare I, Nallapareddy SR, Huang W, Murray BE. A potential virulence gene, hylEfm, predominates in Enterococcus faecium of clinical origin. J Infect Dis. 2003;187(3):508–512. doi: 10.1086/367711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nallapareddy SR, Sillanpaa J, Ganesh VK, Hook M, Murray BE. Inhibition of Enterococcus faecium adherence to collagen by antibodies against high-affinity binding subdomains of Acm. Infect Immun. 2007;75(6):3192–3196. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02016-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillanpaa J, Nallapareddy SR, Prakash VP, Qin X, Hook M, Weinstock GM, Murray BE. Identification and phenotypic characterization of a second collagen adhesin, Scm, and genome-based identification and analysis of 13 other predicted MSCRAMMs, including four distinct pilus loci, in Enterococcus faecium. Microbiology. 2008;154(Pt 10):3199–3211. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/017319-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickx AP, van Luit-Asbroek M, Schapendonk CM, van Wamel WJ, Braat JC, Wijnands LM, Bonten MJ, Willems RJ. SgrA, a nidogen-binding LPXTG surface adhesin implicated in biofilm formation, and EcbA, a collagen binding MSCRAMM, are two novel adhesins of hospital-acquired Enterococcus faecium. Infect Immun. 2009;77(11):5097–5106. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00275-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickx AP, Bonten MJ, van Luit-Asbroek M, Schapendonk CM, Kragten AH, Willems RJ. Expression of two distinct types of pili by a hospital-acquired Enterococcus faecium isolate. Microbiology. 2008;154(Pt 10):3212–3223. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/020891-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillanpaa J, Prakash VP, Nallapareddy SR, Murray BE. Distribution of genes encoding MSCRAMMs and Pili in clinical and natural populations of Enterococcus faecium. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(4):896–901. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02283-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton TJ, Gasson MJ. Molecular screening of Enterococcus virulence determinants and potential for genetic exchange between food and medical isolates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67(4):1628–1635. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.4.1628-1635.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lempiainen H, Kinnunen K, Mertanen A, von Wright A. Occurrence of virulence factors among human intestinal enterococcal isolates. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2005;41(4):341–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2005.01769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semedo T, Santos MA, Lopes MF, Figueiredo Marques JJ, Barreto Crespo MT, Tenreiro R. Virulence factors in food, clinical and reference Enterococci: A common trait in the genus? Syst Appl Microbiol. 2003;26(1):13–22. doi: 10.1078/072320203322337263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creti R, Imperi M, Bertuccini L, Fabretti F, Orefici G, Di Rosa R, Baldassarri L. Survey for virulence determinants among Enterococcus faecalis isolated from different sources. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53(Pt 1):13–20. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05353-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz CM, Muscholl-Silberhorn AB, Yousif NM, Vancanneyt M, Swings J, Holzapfel WH. Incidence of virulence factors and antibiotic resistance among Enterococci isolated from food. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67(9):4385–4389. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.9.4385-4389.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannu L, Paba A, Daga E, Comunian R, Zanetti S, Dupre I, Sechi LA. Comparison of the incidence of virulence determinants and antibiotic resistance between Enterococcus faecium strains of dairy, animal and clinical origin. Int J Food Microbiol. 2003;88(2-3):291–304. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(03)00191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgogne A, Garsin DA, Qin X, Singh KV, Sillanpaa J, Yerrapragada S, Ding Y, Dugan-Rocha S, Buhay C, Shen H. et al. Large scale variation in Enterococcus faecalis illustrated by the genome analysis of strain OG1RF. Genome Biol. 2008;9(7):R110. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-7-r110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawalec M, Pietras Z, Danilowicz E, Jakubczak A, Gniadkowski M, Hryniewicz W, Willems RJ. Clonal structure of Enterococcus faecalis isolated from Polish hospitals: characterization of epidemic clones. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(1):147–153. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01704-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Garbajosa P, Bonten MJ, Robinson DA, Top J, Nallapareddy SR, Torres C, Coque TM, Canton R, Baquero F, Murray BE. et al. Multilocus sequence typing scheme for Enterococcus faecalis reveals hospital-adapted genetic complexes in a background of high rates of recombination. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(6):2220–2228. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02596-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solheim M, Aakra A, Snipen LG, Brede DA, Nes IF. Comparative genomics of Enterococcus faecalis from healthy Norwegian infants. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:194. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nallapareddy SR, Wenxiang H, Weinstock GM, Murray BE. Molecular characterization of a widespread, pathogenic, and antibiotic resistance-receptive Enterococcus faecalis lineage and dissemination of its putative pathogenicity island. J Bacteriol. 2005;187(16):5709–5718. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.16.5709-5718.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray BE, Mederski-Samaroj B. Transferable beta-lactamase. A new mechanism for in vitro penicillin resistance in Streptococcus faecalis. J Clin Invest. 1983;72(3):1168–1171. doi: 10.1172/JCI111042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vebø HC, Solheim M, Snipen L, Nes IF, Brede DA. Comparative Genomic Analysis of Pathogenic and Probiotic Enterococcus faecalis Isolates, and Their Transcriptional Responses to Growth in Human Urine. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(8):e12489. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride SM, Fischetti VA, Leblanc DJ, Moellering RC Jr, Gilmore MS. Genetic diversity among Enterococcus faecalis. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(7):e582. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen IT, Banerjei L, Myers GS, Nelson KE, Seshadri R, Read TD, Fouts DE, Eisen JA, Gill SR, Heidelberg JF. et al. Role of mobile DNA in the evolution of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Science. 2003;299(5615):2071–2074. doi: 10.1126/science.1080613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Schaik W, Top J, Riley DR, Boekhorst J, Vrijenhoek JE, Schapendonk CM, Hendrickx AP, Nijman IJ, Bonten MJ, Tettelin H, Pyrosequencing-based comparative genome analysis of the nosocomial pathogen Enterococcus faecium and identification of a large transferable pathogenicity island. BMC Genomics. p. 239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bessman MJ, Frick DN, O'Handley SF. The MutT proteins or "Nudix" hydrolases, a family of versatile, widely distributed, "housecleaning" enzymes. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(41):25059–25062. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.41.25059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuteja N, Tuteja R. Prokaryotic and eukaryotic DNA helicases. Essential molecular motor proteins for cellular machinery. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271(10):1835–1848. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04093.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar N, Baghdayan AS, Gilmore MS. Modulation of virulence within a pathogenicity island in vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Nature. 2002;417(6890):746–750. doi: 10.1038/nature00802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride SM, Coburn PS, Baghdayan AS, Willems RJ, Grande MJ, Shankar N, Gilmore MS. Genetic variation and evolution of the pathogenicity island of Enterococcus faecalis. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(10):3392–3402. doi: 10.1128/JB.00031-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepage E, Brinster S, Caron C, Ducroix-Crepy C, Rigottier-Gois L, Dunny G, Hennequet-Antier C, Serror P. Comparative genomic hybridization analysis of Enterococcus faecalis: identification of genes absent from food strains. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(19):6858–6868. doi: 10.1128/JB.00421-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinster S, Furlan S, Serror P. C-terminal WxL domain mediates cell wall binding in Enterococcus faecalis and other gram-positive bacteria. J Bacteriol. 2007;189(4):1244–1253. doi: 10.1128/JB.00773-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siezen R, Boekhorst J, Muscariello L, Molenaar D, Renckens B, Kleerebezem M. Lactobacillus plantarum gene clusters encoding putative cell-surface protein complexes for carbohydrate utilization are conserved in specific gram-positive bacteria. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:126. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierne H, Sabet C, Personnic N, Cossart P. Internalins: a complex family of leucine-rich repeat-containing proteins in Listeria monocytogenes. Microbes Infect. 2007;9(10):1156–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinster S, Posteraro B, Bierne H, Alberti A, Makhzami S, Sanguinetti M, Serror P. Enterococcal leucine-rich repeat-containing protein involved in virulence and host inflammatory response. Infect Immun. 2007;75(9):4463–4471. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00279-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard BD, Gilmore MS. Differential expression of virulence-related genes in Enterococcus faecalis in response to biological cues in serum and urine. Infect Immun. 2002;70(8):4344–4352. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.8.4344-4352.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vebø HC, Snipen L, Nes IF, Brede DA. The transcriptome of the nosocomial pathogen Enterococcus faecalis V583 reveals adaptive responses to growth in blood. PLoS One. 2009;4(11):e7660. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson JC, Colley KJ. Glycosyltransferases. Structure, localization, and control of cell type-specific glycosylation. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(30):17615–17618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Murray BE, Weinstock GM. A cluster of genes involved in polysaccharide biosynthesis from Enterococcus faecalis OG1RF. Infect Immun. 1998;66(9):4313–4323. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4313-4323.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock LE, Gilmore MS. The capsular polysaccharide of Enterococcus faecalis and its relationship to other polysaccharides in the cell wall. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(3):1574–1579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032448299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner J, Wang Y, Krueger WA, Madoff LC, Martirosian G, Boisot S, Goldmann DA, Kasper DL, Tzianabos AO, Pier GB. Isolation and Chemical Characterization of a Capsular Polysaccharide Antigen Shared by Clinical Isolates of Enterococcus faecalis and Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus faecium. Infect Immun. 1999;67(3):1213–1219. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1213-1219.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosink KK, Mann ER, Guglielmo C, Tuomanen EI, Masure HR. Role of novel choline binding proteins in virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 2000;68(10):5690–5695. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.10.5690-5695.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenow C, Ryan P, Weiser JN, Johnson S, Fontan P, Ortqvist A, Masure HR. Contribution of novel choline-binding proteins to adherence, colonization and immunogenicity of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25(5):819–829. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1997.mmi494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillanpaa J, Xu Y, Nallapareddy SR, Murray BE, Hook M. A family of putative MSCRAMMs from Enterococcus faecalis. Microbiology. 2004;150(Pt 7):2069–2078. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27074-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski WJ, Kasper EL, Hatton JF, Murray BE, Nallapareddy SR, Gillespie MJ. Enterococcus faecalis adhesin, Ace, mediates attachment to particulate dentin. J Endod. 2006;32(7):634–637. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nallapareddy SR, Qin X, Weinstock GM, Hook M, Murray BE. Enterococcus faecalis adhesin, ace, mediates attachment to extracellular matrix proteins collagen type IV and laminin as well as collagen type I. Infect Immun. 2000;68(9):5218–5224. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.9.5218-5224.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich RL, Kreikemeyer B, Owens RT, LaBrenz S, Narayana SV, Weinstock GM, Murray BE, Hook M. Ace is a collagen-binding MSCRAMM from Enterococcus faecalis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(38):26939–26945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.26939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebreton F, Riboulet-Bisson E, Serror P, Sanguinetti M, Posteraro B, Torelli R, Hartke A, Auffray Y, Giard JC. ace, Which encodes an adhesin in Enterococcus faecalis, is regulated by Ers and is involved in virulence. Infect Immun. 2009;77(7):2832–2839. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01218-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nallapareddy SR, Singh KV, Murray BE. Contribution of the collagen adhesin Acm to pathogenesis of Enterococcus faecium in experimental endocarditis. Infect Immun. 2008;76(9):4120–4128. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00376-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden SK, Sutton P, Karlsson NG, Korolik V, McGuckin MA. Mucins in the mucosal barrier to infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1(3):183–197. doi: 10.1038/mi.2008.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Styriak I, Ljungh S. Binding of extracellular matrix molecules by enterococci. Curr Microbiol. 2003;46(6):435–442. doi: 10.1007/s00284-002-3879-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall AE, Gorovits EL, Syribeys PJ, Domanski PJ, Ames BR, Chang CY, Vernachio JH, Patti JM, Hutchins JT. Monoclonal antibodies recognizing the Enterococcus faecalis collagen-binding MSCRAMM Ace: Conditional expression and binding analysis. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2007;43(2-3):55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nallapareddy SR, Singh KV, Duh R-W, Weinstock GM, Murray BE. Diversity of ace, a Gene Encoding a Microbial Surface Component Recognizing Adhesive Matrix Molecules, from Different Strains of Enterococcus faecalis and Evidence for Production of Ace during Human Infections. Infect Immun. 2000;68(9):5210–5217. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.9.5210-5217.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu WL, Dan H, Lin M. InlA and InlC2 of Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b are two internalin proteins eliciting humoral immune responses common to listerial infection of various host species. Curr Microbiol. 2008;56(5):505–509. doi: 10.1007/s00284-008-9101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth GK, Speed T. Normalization of cDNA microarray data. Methods. 2003;31(4):265–273. doi: 10.1016/S1046-2023(03)00155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snipen L, Nyquist OL, Solheim M, Aakra A, Nes IF. Improved analysis of bacterial CGH data beyond the log-ratio paradigm. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10(1):91. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer KL, Carniol K, Manson JM, Heiman D, Shea T, Young S, Zeng Q, Gevers D, Feldgarden M, Birren B, High Quality Draft Genome Sequences of 28 Enterococcus sp. Isolates. J Bacteriol. JB.00153-00110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Peterson J, Garges S, Giovanni M, McInnes P, Wang L, Schloss JA, Bonazzi V, McEwen JE, Wetterstrand KA, Deal C. et al. The NIH Human Microbiome Project. Genome Res. 2009;19(12):2317–2323. doi: 10.1101/gr.096651.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huycke MM, Spiegel CA, Gilmore MS. Bacteremia caused by hemolytic, high-level gentamicin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35(8):1626–1634. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.8.1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahm DF, Kissinger J, Gilmore MS, Murray PR, Mulder R, Solliday J, Clarke B. In vitro susceptibility studies of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33(9):1588–1591. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.9.1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moellering RC Jr, Weinberg AN. Studies on antibiotic syngerism against enterococci. II. Effect of various antibiotics on the uptake of 14 C-labeled streptomycin by enterococci. J Clin Invest. 1971;50(12):2580–2584. doi: 10.1172/JCI106758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aakra A, Nyquist OL, Snipen L, Reiersen TS, Nes IF. Survey of genomic diversity among Enterococcus faecalis strains by microarray-based comparative genomic hybridization. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(7):2207–2217. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01599-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice LB, Eliopoulos GM, Wennersten C, Goldmann D, Jacoby GA, Moellering RC Jr. Chromosomally mediated beta-lactamase production and gentamicin resistance in Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35(2):272–276. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.2.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler SM, Foley GE. Studies on the Streptococci (Enterococci) of Lancefield Group-D .2. Recovery of Lancefield Group D Streptococci from Antemortem and Postmortem Cultures from Infants and Young Children. American Journal of Diseases of Children. 1945;70(4):207–213. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1945.02020220008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray BE, Singh KV, Ross RP, Heath JD, Dunny GM, Weinstock GM. Generation of restriction map of Enterococcus faecalis OG1 and investigation of growth requirements and regions encoding biosynthetic function. J Bacteriol. 1993;175(16):5216–5223. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.16.5216-5223.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maekawa S, Yoshioka M, Kumamoto Y. Proposal of a new scheme for the serological typing of Enterococcus faecalis strains. Microbiol Immunol. 1992;36(7):671–681. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1992.tb02070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackermann HW, Caprioli T, Kasatiya SS. A large new Streptococcus bacteriophage. Can J Microbiol. 1975;21(4):571–574. doi: 10.1139/m75-080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domann E, Hain T, Ghai R, Billion A, Kuenne C, Zimmermann K, Chakraborty T. Comparative genomic analysis for the presence of potential enterococcal virulence factors in the probiotic Enterococcus faecalis strain Symbioflor 1. Int J Med Microbiol. 2007;297(7-8):533–539. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob AE, Hobbs SJ. Conjugal transfer of plasmid-borne multiple antibiotic resistance in Streptococcus faecalis var. zymogenes. J Bacteriol. 1974;117(2):360–372. doi: 10.1128/jb.117.2.360-372.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clewell DB, Yagi Y, Dunny GM, Schultz SK. Characterization of three plasmid deoxyribonucleic acid molecules in a strain of Streptococcus faecalis: identification of a plasmid determining erythromycin resistance. J Bacteriol. 1974;117(1):283–289. doi: 10.1128/jb.117.1.283-289.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner P, Smith DH, Beer H, Moellering RC Jr. Recovery of resistance (R) factors from a drug-free community. Lancet. 1969;2(7624):774–776. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(69)90482-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington SM, Ross TL, Gebo KA, Merz WG. Vancomycin resistance, esp, and strain relatedness: a 1-year study of enterococcal bacteremia. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(12):5895–5898. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5895-5898.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manson JM, Keis S, Smith JM, Cook GM. Characterization of a vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis (VREF) isolate from a dog with mastitis: further evidence of a clonal lineage of VREF in New Zealand. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(7):3331–3333. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.7.3331-3333.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

BLAST comparison of E. faecalis genomes. Data from BLAST comparison of 24 E. faecalis draft genomes with the annotated genes of strain V583.

V583 genes which were identified as significantly enriched among CC2-strains in the present study. A list of V583 genes which were identified as significantly enriched among CC2-strains in the present study.

PCR screening. An overview of results from PCR screening of a collection of E. faecalis isolates.

Enrichment analysis of CC6 non-V583 genes by Fisher's exact test. An overview of the presence non-V583 genes in 24 E. faecalis draft genomes CC6 including data from enrichment analysis by Fisher's exact test.

Amino acid alignment of HMPREF0346_1863 in Enterococcus faecalis HH22 and its homologue in E. faecalis TX0104. An amino acid alignment of HMPREF0346_1863 in Enterococcus faecalis HH22 and its homologue in E. faecalis TX0104.