Abstract

Background

Short interstitial telomere motifs (telo boxes) are short sequences identical to plant telomere repeat units. They are observed within the 5' region of several genes over-expressed in cycling cells. In synergy with various cis-acting elements, these motifs participate in the activation of expression. Here, we have analysed the distribution of telo boxes within Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa genomes and their association with genes involved in the biogenesis of the translational apparatus.

Results

Our analysis showed that the distribution of the telo box (AAACCCTA) in different genomic regions of A. thaliana and O. sativa is not random. As is also the case for plant microsatellites, they are preferentially located in the 5' flanking regions of genes, mainly within the 5' UTR, and distributed as a gradient along the direction of transcription. As previously reported in Arabidopsis, a conserved topological association of telo boxes with site II or TEF cis-acting elements is observed in almost all promoters of genes encoding ribosomal proteins in O. sativa. Such a conserved promoter organization can be found in other genes involved in the biogenesis of the translational machinery including rRNA processing proteins and snoRNAs. Strikingly, the association of telo boxes with site II motifs or TEF boxes is conserved in promoters of genes harbouring snoRNA clusters nested within an intron as well as in the 5' flanking regions of non-intronic snoRNA genes. Thus, the search for associations between telo boxes and site II motifs or TEF box in plant genomes could provide a useful tool for characterizing new cryptic RNA pol II promoters.

Conclusions

The data reported in this work support the model previously proposed for the spreading of telo boxes within plant genomes and provide new insights into a putative process for the acquisition of microsatellites in plants. The association of telo boxes with site II or TEF cis-acting elements appears to be an essential feature of plant genes involved in the biogenesis of ribosomes and clearly indicates that most plant snoRNAs are RNA pol II products.

Background

Regulatory sequences constitute a small fraction of eukaryotic genomes that determine the level, location and chronology of gene expression. In parallel to functional studies, computational analysis provides different approaches for scanning genomic sequence to identify those regions predicted to participate in gene regulation [1,2]: (i) sequence analysis of co-regulated genes within a given species, (ii) inter-species sequence comparison of orthologous genes and (iii), database construction and analysis of known transcription-factor binding sites.

Functional studies conducted to identify trans and cis-acting elements controlling the expression of translation factors and ribosomal proteins (rp) in Arabidopsis allowed us to characterize several cis-acting elements. One of them, the telo box (AAACCCTA), was first observed within the promoter of the four Arabidopsis genes encoding the translation elongation factor EF1αpromoters [3,4] and subsequently within a few plant rp promoters [5]. This short motif is identical to the repeat (AAACCCT)n of plant telomeres [6] but differs from long interstitial telomere repeats (ITRs) which are found at discrete intrachromosomal sites in many eukaryotic species [7,8] and probably result from chromosomal rearrangements such as end-fusions and segmental duplications. In contrast to the limited number of ITRs observed in pericentromeric and subtelomeric regions in Arabidopsis [8], a preliminary computational analysis suggested that short telomere repeats (telo boxes) were over-represented at the 5' end of Arabidopsis ESTs [9]. More recently, with the achievement of the Arabidopsis sequencing project, we showed that the occurrence of telo boxes within rp promoters is the rule rather than the exception [10,11]. Telo boxes were also observed in promoters of several protein-encoding genes which, as is the case for rp, are expected to be over-expressed in cycling cells, suggesting that it could be involved in the coordinated expression of this class of genes. Experimental data indicated that the telo box was indeed involved in the expression in cycling cells [11-13]. However, by itself this motif is not able to activate the transcription by RNA pol II but acts in synergy with various cis-acting elements to increase the expression. These cis-acting elements include the TEF1 box identified in promoters of the translation elongation factor EF1α[14], the Trap1 box in the promoter of a rp gene [15] and redundant site II motifs initially characterized in the promoter of the proliferating cellular nuclear antigen gene (PCNA) [16] and subsequently in most Arabidopsis rp genes [11].

In this study, we analysed the distribution of telo boxes within A. thaliana and O. sativa genomes and their association with genes involved in the biogenesis of the translational apparatus. In addition, this analysis revealed a striking analogy with the genomic distribution of telo boxes and plant microsatellites.

Results

Definition of the telo box and distribution in different genomic regions

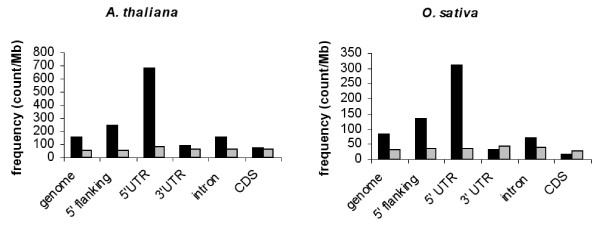

An initial statistical study [9] conducted by using a large set of Arabidopsis ESTs [17,18] and Arabidopsis genes available at this time suggested that the sequence AAACCCTAA corresponding to 1.3 units of the plant telomere repeat AAACCCT [6] was over-represented and preferentially located in the 5' region of genes. The completion of Arabidopsis and O. sativa sequencing means that they can now be subjected to similar but exhaustive analysis. A chi-square test was used to determine whether the observed frequencies (counts) of telobox in the different compartments markedly differ from the frequencies that we would expect by chance. Chi-square statistics for A. thaliana and O. sativa were obtained that clearly indicate that the observed frequencies in each compartment differ markedly from the expected frequencies (Table 1). We also studied the occurrence of seven putative telomere motifs obtained from a circular permutation of the sequence AAACCCTA corresponding to 1.14 telomere repeat units [6]. This study was conducted by using Arabidopsis and O. sativa 5' UTR sequences. The results reported in Figure 1 and Table 1 confirm our previous observations and extend them to a monocot. Among the seven sequences analysed, the motif AAACCCTA (telo box) is over-represented in both Arabidopsis and rice. The use of a control-related sequence (AAACCTCA) enabled us to exclude the base composition as a cause of the over-representation of telo boxes. We characterized the occurrence of telo boxes among the different genomic regions in the Arabidopsis and O. Sativa genomes. Just as a high level of telo boxes was initially observed at the 5' end of Arabidopsis ESTs [9], it was obvious that the frequency of telo boxes was higher within the 5' flanking regions, mainly within the 5' UTRs (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Distribution of telo boxes in A. thaliana and O. sativa genomes

| Genome compartment | Size | Telo counts | Telo Freq. (nb/Mb) | Telo expected | χ2 | P | χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. thaliana | ||||||||

| Genome | 135709386 | 21057 | 155.2 | |||||

| 5'UTR | 3614786 | 2426 | 680.3 | 561 | 6372 | 0.E+00 | 8381 | 0,00E+000 |

| 3'UTR | 6019104 | 527 | 87 | 934 | 186 | 3.E-42 | ||

| Intron | 25425536 | 3829 | 150.7 | 3945 | 4 | 4.E-02 | ||

| CDS | 39588516 | 2966 | 74.9 | 6143 | 2319 | 0.E+00 | ||

| Other | 61061444 | 11309 | 185.2 | 9474 | 646 | 2.E-142 | ||

| O. sativa | ||||||||

| Genome | 378522865 | 30686 | 81.1 | |||||

| 5'UTR | 7907129 | 2463 | 311.5 | 641 | 5289 | 0.E+00 | 13143 | 0,00E+000 |

| 3'UTR | 15330979 | 460 | 30 | 1243 | 514 | 9.E-114 | ||

| Intron | 102300755 | 7367 | 72 | 8293 | 142 | 1.E-32 | ||

| CDS | 91775879 | 1489 | 16/02/10 | 7440 | 6284 | 0.E+00 | ||

| Other | 161208123 | 18907 | 117.3 | 13069 | 4543 | 0.E+00 | ||

Number of telo box motifs in the different compartments (5'UTR, 3'UTR, Introns, CDS) of A. thaliana and O. sativa genomes. A chi-square test was performed to assess deviation from the expected uniform distribution.

Figure 1.

Analysis from a circular permutation of frequencies of plant telomere motifs within 5' UTR regions. The telomere motifs (one telomere repeat unit + one nucleotide) found in A. thaliana and O. sativa are shown in black, a control sequence in grey. A, CTAAACCC and TCAAACCT; B, TAAACCCT and CAAACCTC; C, AAACCCTA and AAACCTCA; D, AACCCTAA and AACCTCAA; E, ACCCTAAA and ACCTCAAA; F, CCCTAAAC and CCTCAAAC; G, CCTAAACC and CTCAAACC.

Figure 2.

Examples of the presence of telo boxes and trinucleotide repeats in 5' UTR of rp genes. Occurrence of both telo boxes (AAACCCTA) and tri-nucleotide repeats (GAA/TTC in Arabidopsis and GCC/GGC in O. sativa) within 5'UTR. The telo boxes are boxed in black, the tri-nucleotide repeats in yellow, the transcription start site in red; the translation ATG codons are in bold and the putative TATA boxes are underlined.

Comparative distribution of telo boxes and microsatellites

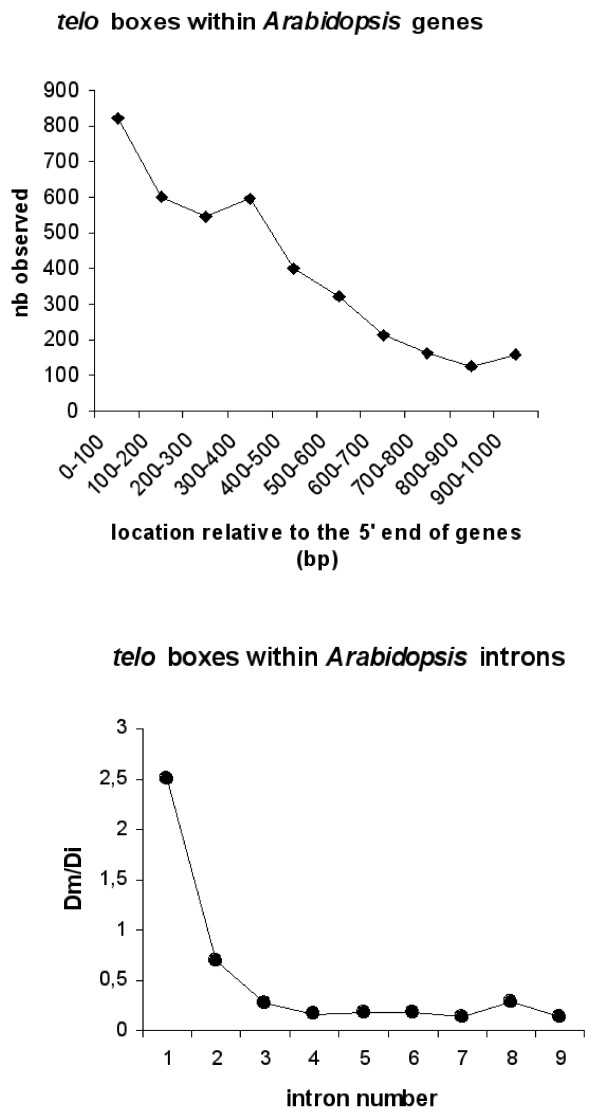

Previous studies have revealed that in Arabidopsis as in O. sativa, microsatellites or simple sequence repeats (SSRs) and pyrimidine patches (Y Patches) are more frequently observed in 5' UTRs than in coding regions or 3' UTRs [19-24]. Among SSRs, tri-nucleotide repeats (TNRs) are more abundant and differentially represented in monocots and dicots. Thus, the TNR (GCC/GGC)n is the most abundant in the 5' flanking regions in O. sativa whereas it is (GAA/TTC)n in Arabidopsis. In contrast, Y Patches which are more frequently found in plant core promoter regions are observed in both Arabidopsis and O. sativa 5' regions [22,23]. The results reported in Table 1 and Table 2 reveal a striking analogy in the genomic distribution of telo boxes, TNRs and Y Patches between 5' UTRs and 3' UTRs in Arabidopsis and O. sativa. The frequency of appearance of telo boxes is 10-20 higher within 5'UTR compared to that observed within 3'UTR. Two relevant examples of such a location of telo boxes and trinucleotide repeats in the 5' flanking regions of Arabidopsis and O. sativa rp genes are shown in Figure 2. Moreover, as has been reported for Arabidopsis microsatellites [19], there is a distribution gradient of telo boxes along the direction of transcription. The telo boxes (which are observed at a lower frequency within Arabidopsis CDS and introns - see Figure 3) are not uniformly distributed. There is a progressive decrease in the number of telo box motifs observed within the first 1000 nucleotides from the 5' end of genes and a higher occurrence of this motif within the first two introns (Figure 4).

Table 2.

Distribution of telo boxes, microsatellites and Y Patch in 5' and 3' UTR in A. thaliana and O. sativa

| Motif | 5' UTR(number) | 3' UTR (number) | 5' UTR frequency counts/Mb | 3' UTR frequency counts/Mb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. thaliana | ||||

| AAACCCTA | 2426 | 527 | 680 | 87 |

| AAACCTCA | 343 | 397 | 95 | 66 |

| (GAA/TTC)6 | 394 | 49 | 109 | 8 |

| (GCC/GGC)6 | 1 | 0 | 0.3 | 0 |

| (Y/R)18 | 5216 | 1448 | 1934 | 322 |

| O. sativa | ||||

| AAACCCTA | 2463 | 460 | 311 | 30 |

| AAACCTCA | 278 | 642 | 35 | 41 |

| (GAA/TTC)6 | 72 | 36 | 9 | 2 |

| (GCC/GGC)6 | 546 | 25 | 69 | 2 |

| (Y/R)18 | 6729 | 1827 | 851 | 119 |

Bytes searched: Arabidopsis 5' UTR, 3614786 bp; Arabidopsis 3' UTR, 6019104 bp; O. sativa 5' UTR, 7907129 bp; O. sativa 3' UTR, 15330979 bp.

Figure 3.

Distribution of telo boxes in different genomic regions in Arabidopsis and O. sativa. The telo box, AAACCCTA, and the related sequence, AAACCTCA, are shown in black and grey, respectively.

Figure 4.

Distribution gradient of telo boxes along the direction of transcription in Arabidopsis. Location of telo boxes within Arabidopsis genes is estimated from the TAIR database (TAIR9 CDS+UTRs+introns datasets); frequency of appearance of telo boxes within Arabidopsis introns from the TAIR9 introns datasets. Dm is the % of motifs found within a given intron relative to the total number of motifs observed within the Arabidopsis introns (TAIR database, introns). Di is the % of introns at a given position (intron 1, 2, 3...) relative to the estimated total number of introns.

Telo boxes in the promoters of plant genes involved in ribosome biogenesis

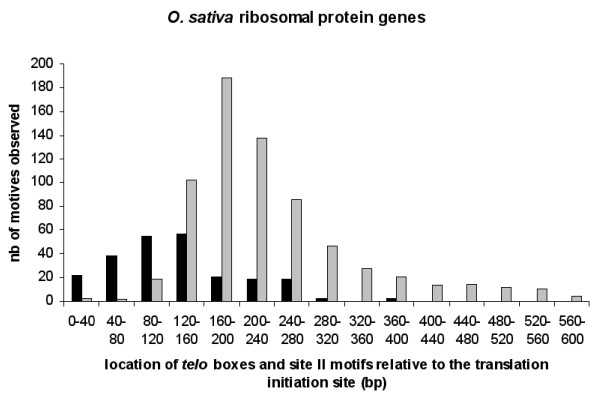

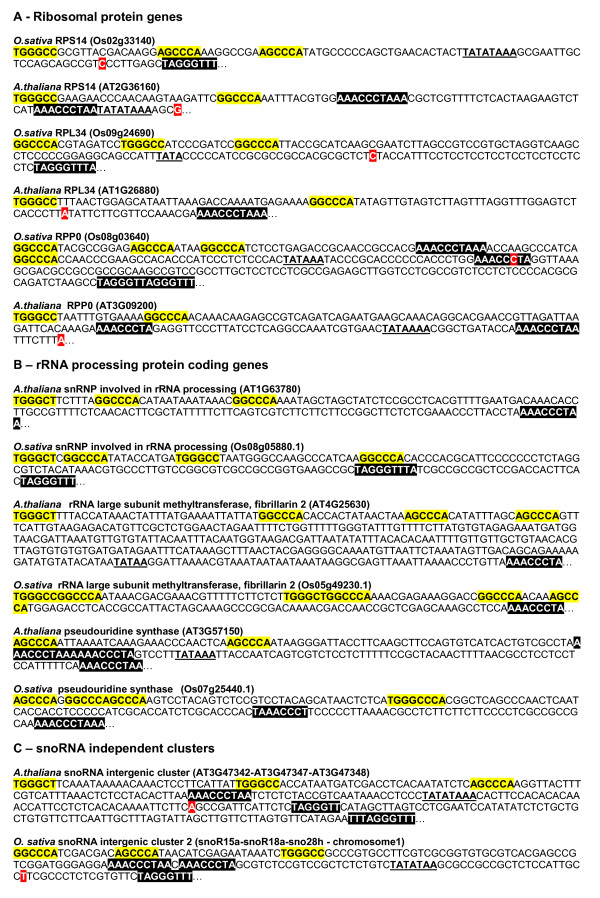

As estimated by using the 'TAIR9 Loci Upstream Sequences -500 bp (DNA)' and 'TAIR9 5' UTRs (DNA)' datasets, the number of Arabidopsis genes harbouring one or several telo boxes within their 5' flanking region or 5' UTRs is 3234 (9.7% of Arabidopsis genes) and 2247 (9.2%), respectively. Among them, we have reported that ribosomal protein (rp) genes constituted an important sub-family showing a specific topological association of telo boxes with redundant site II motifs (TGGGCY) or to a lesser extent with TEF1 box (ARGGRYNNNNNGYA) cis-acting elements [11]. An analysis for functional categorization by loci of Arabidopsis genes showing an association of a telo box with at least two site II motifs confirms this previous observation: the product of 17.9% of these genes was expected to be associated with ribosomes against 2% for all GO annotated Arabidopsis genes. Here we extended this study to the monocot O. sativa by using the 'Ribosomal Protein Gene Database' (RPG) [24]. Out of 252 rice ribosomal protein genes, 209 (83%) contain at least one telo box within their 5' flanking region and 202 (80%) an association of telo boxes with site II motifs or TEF boxes (Additional File 1). Figure 5 shows the topological distribution of these elements. This distribution is similar to that observed for rp genes in Arabidopsis [11]. An illustration of this conserved lay-out within the promoter of Arabidopsis and rice rp orthologous genes is given in Figure 6A, where telo boxes and site II motifs are found within windows between '0 and 280 bp' and '80 and 400 bp' relative to the translation initiation codon, respectively.

Figure 5.

Statistical distribution of motifs in the 5' flanking regions of O. sativa ribosomal protein genes. Statistical distribution of telo boxes (black) and site II motifs (grey) in the 5' flanking regions of O. sativa ribosomal protein genes.

Figure 6.

Topological association of telo boxes and site II motif in 5' regions of known genes. Illustration of the conserved topological association of telo boxes and site II motifs in the promoter of Arabidopsis and O. sativa orthologous ribosomal and rRNA processing protein coding genes and in the 5' flanking regions of Arabidopsis and O. sativa independently transcribed snoRNA clusters. Site II motifs are boxed in yellow, telo boxes in black, the location of TSS in red; putative TATA boxes are underlined.

In addition to ribosomal proteins, the biogenesis of cytoplasmic ribosomes also requires the biosynthesis of 5.8 S, 18 S and 25/26 S rRNAs, a process which is achieved by the transcription of rDNA and by endo- and exonucleolytic cleavages and extensive modifications of an rRNA precursor (pre-rRNA). Small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs), in association with specific nucleolar proteins (SnRNP), are involved in this process.

The occurrence of telo boxes and their association with site II motifs or TEF boxes in the promoter of genes encoding rRNA processing proteins was examined in Arabidopsis. For 49 genes annotated in the TAIR database as encoding a cytoplasmic rRNA processing protein, 46 (92%) contain at least one telo box in the 5' flanking region and 35 (70%) an association between telo boxes and site II motifs or TEF1 boxes (Additional File 2A and illustrations in Figure 6B). The occurrence of telo boxes in the 5' flanking region of O. sativa orthologous genes of the 46 Arabidopsis genes harbouring a telo box was analysed. By using the greenphyl database [25] we identified 37 orthologous rice genes. For 30 of them (81%), at least one telo box was identified within the 1 Kb 5' flanking region and for 25 (68%) an association of telo boxes with site II motifs or a TEF box was observed (Additional File 2B and illustrations in Figure 6B). The same analysis was conducted for snoRNA genes in Arabidopsis and O. sativa. The resulting data are summarized in Table 3. In Arabidopsis there are 71 snoRNA genes annotated in the TAIR database. These snoRNA genes are orphans or associated in clusters. Three of them are nested within introns of genes containing a typical association of telo boxes and site II motifs within their promoters (Additional File 3). For the remaining 40 non-intronic loci, a search for the occurrence of telo boxes, site II motifs and TEF1 boxes was carried out upstream from the 5' end of the far-upstream mature snoRNA. For 37 loci (92%) telo boxes were observed and for 34 (85%) an association of telo boxes with site II motifs or TEF1 boxes (Additional File 3 and illustration in Figure 5C). In O. sativa the analysis was conducted on 109 putative snoRNA loci comprising 67 clusters and 42 orphan snoRNA genes. The detail of this analysis is shown in Additional File 4. As previously reported [26,27], intronic snoRNA loci are more frequent in rice than in Arabidopsis. In the present work they were estimated at 31 (28% of snoRNA loci). 15 of the clusters or orphan intronic snoRNA genes are nested within introns of rp genes showing an association of telo boxes with site II motifs within their promoter. For 10 of the 16 remaining intronic snoRNA genes a similar association was observed. The analysis of 5' flanking sequences of independent snoRNA clusters confirms the data obtained for Arabidopsis: out of 41 independent clusters, 22 (54%) harbour a telo box within the 5' flanking region and 21 (51%) an association of telo boxes with site II motifs (Additional File 5). This conservation is less evident for non-intronic orphan snoRNA genes but remains significant: out of 35 non-intronic orphan genes, 15 (43%) contain a telo box and 14 (40%) an association of telo boxes with site II motifs within the 5' flanking sequences. To summarize, 57% of O. sativa snoRNA putative loci studied in this work contain at least one telo box and 56% an association of telo boxes with site II motifs in their 5' flanking region. As discussed, the loci which are not associated with telo boxes and site II motifs could be transcribed by RNA pol III or pseudogenes.

Table 3.

Summary of the analysis of 5' flanking regions of A. thaliana and O. sativa snoRNA genes

| Analysed (Number) | telo boxes | Associations telo box - sites II |

Associations telo box - TEF |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. thaliana | ||||

| Intronic snoRNA clusters | 1 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Intronic orphan snoRNAs | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Intergenic snoRNA clusters | 17 | 16 | 16 | 1 |

| Intergenic orphan snoRNAs | 23 | 21 | 17 | 1 |

| O. sativa | ||||

| Intronic snoRNA clusters | 25 | 22 | 22 | 1 |

| Intronic orphan snoRNAs | 7 | 5 | 3 | 0 |

| Intergenic snoRNA clusters | 42 | 20 | 19 | 1 |

| Intergenic orphan snoring | 47 | 13 | 8 | 0 |

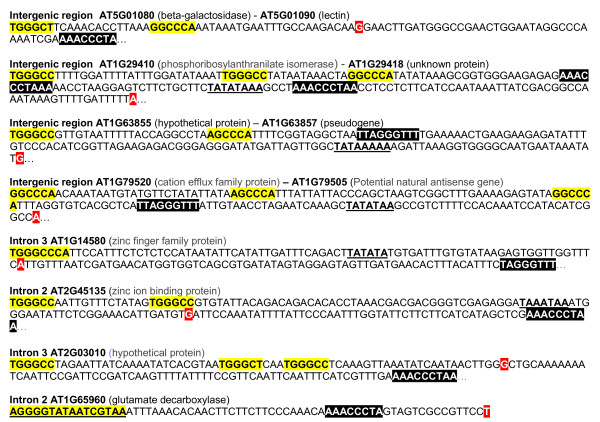

Identification of cryptic promoters by using the conserved topological association of telo boxes with cis-acting elements

As illustrated by the characterization of unknown snoRNA gene promoters, the use of the conserved topological association of telo boxes with cis-acting elements observed within promoters of genes involved in ribosome biogenesis could provide an interesting tool to identify new cryptic RNA pol II promoters and for improving the annotation of plant genomes. A first analysis conducted in Arabidopsis by using a compilation of associations of telo boxes with at least two site II motifs or a TEF box and a BLAST search with the sequences located downstream from these associations in the "A. thaliana GB experimental cDNA/EST (DNA) dataset" allowed us to identify new transcript units. This is illustrated in Figure 7 showing the identification in four intergenic regions and four introns of new transcripts which are not annotated in the TAIR database.

Figure 7.

Use of the conserved topological association of motifs to characterize cryptic RNA pol II promoters. Site II motifs are boxed in yellow, TEF1 boxes in yellow and underlined, telo boxes in black, TSS in red; putative TATA boxes are underlined.

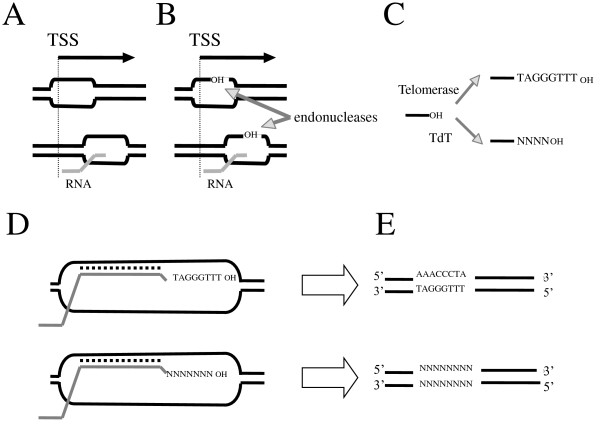

Discussion

One remarkable item of data resulting from this study is the striking similarity observed in the genomic distribution of telo boxes and microsatellites. Their preferential location in 5' flanking regions can be assigned to their role in gene expression as has been reported for both telo boxes [11,12] and microsatellites [28,29]. However, we think that this preferential distribution in 5' regions could also reflect a common process involved in the acquisition of these motifs. We previously proposed a model involving the telomerase and recombination events to explain the spreading of telo boxes within Arabidopsis genome [9]. A schematic representation of this model and of its possible analogy with the acquisition process of microsatellites is shown in Figure 8. It can be summarized as follows: (i) Promoter regions are hot spots for recombination and it is well established that there is a relationship between recombination and chromatin accessibility to nucleases occurring during transcription initiation and elongation processes [30-32], (Figure 8A). (ii) Free 3'OH recombinogenic ssDNA is thus generated, (Figure 8B). (iii) These free 3'OH ends are potential substrates for telomerase which, in the absence of telomere repeats interacting with the telomerase anchor site, could act in a non-processive manner by adding only one telomere motif at the 3' end [33], (Figure 8C). It must be emphasized that, as for rp genes, there is also a strong correlation between cell cycle progression and telomerase expression in Arabidopsis [34]. (iv): The 3' end invasion at homologous open sites (Figure 8D) followed by error-prone DNA repair leads to the acquisition of a telomere repeat unit (Figure 8E). A related process has been suggested for the spreading of microsatellites in the human genome by 3'OH-extension of retrotranscripts [35]. As we suggested for the putative generation of telo boxes driven by the telomerase RNA template, the authors speculate that RNA guides could give rise to specific microsatellite sequences. In a similar manner, the spreading of simple repeated sequences such as Y patches could be achieved by addition of nucleotides to free 3' ends by a terminal transferase (TdT), (Figure 8D and 8E). The occurrence in angiosperms of a TdT activity has been reported in germinating wheat embryos [36]. During V(D)J recombination in mammals, the TdT contribute greatly to the generation of diversity in the immune repertoire and the addition of template-independent nucleotides frequently consists of purine or pyrimidine tracts [37]. The common feature in the hypothetical transcription-associated recombination processes mentioned above is the availability of a free 3' end for TdT, telomerase or other related hypothetical specific RNA-guided reverse transcriptase followed by error-prone DNA repair. In the context discussed here it is interesting to mention that similarly to our data showing a high frequency of telo boxes within 5' UTRs of genes encoding components involved in the biogenesis of ribosomes, 46.5% of translation-related genes in rice contain some microsatellites in their predicted 5' UTRs, (GCC/GGC)n contributing for about half of them [19 and our unpublished data].

Figure 8.

Possible transcription-associated recombination mechanism. A possible transcription-associated recombination mechanism is proposed for spreading of telo boxes, microsatellites and Y patches within plant genomes. (A) open transcription pre-initiation complex and R-loop at promoter-proximal pausing sites; (B) generation of free 3'OH recombinogenic ssDNA by endonucleases; (C) the free 3'OH ends are substrates for telomerase or terminal transferase; (D) 3' end invasion at homologous open sites followed by error-prone DNA repair; (E) acquisition of a telomere repeat unit or new nucleotides. See text for comments. TSS: transcription start site. TdT: terminal transferase.

Biogenesis of ribosomes is a crucial process requiring the coordinate expression of hundreds of genes. In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae this synchronized expression is primarily accomplished at the transcriptional level and mediated through common upstream activating sequences including in most cases Rap1p binding sites (rpg boxes) and, in a small subset of rp genes, Abf1p binding sites [38,39]. In higher eukaryotes little is known about the transcriptional network controlling this regulon [40]. Studies conducted in our group over the last two decades have led to the identification of several transcriptional trans and cis-acting elements which participate in the over-expression of translational factor and rp genes in dividing plant cells [3,11,12,14,41]. The data reported in the present work suggest that the occurrence of telo boxes in the 5' flanking regions of rp genes is the rule not only in Arabidopsis but in angiosperms in general and therefore extend this observation to genes involved in the maturation of pre-rRNA. In agreement with data coming from a genome-wide analysis suggesting that the sequences AAACCCTA and TAGGGTTT are Arabidopsis core promoter elements [22], the majority of telo boxes observed in 5' flanking regions of plant translation-related genes are located within a narrow window located -50 to +50 relative to the transcription start site (TSS). The conservation of a topological association between telo boxes and site II motifs or TEF box cis-acting elements provides insights into the transcriptional regulation process required for the coordinate expression of plant genes involved in ribosome biogenesis. For several aspects, a parallel can be drawn between the putative role of telo boxes in plants and those achieved by the rpg cis-acting element in the yeast S. cerevisiae: (i) the rpg boxes (ACACCCAYACAY) show an homology with yeast telomere repeats (C(1-3)A)n and are both targets for the Rap1p pleiotropic protein involved in telomere metabolism and gene expression [42]; (ii) a common characteristic of yeast genes under the control of rpg boxes is their very high transcription rate during exponential growth. Up to now, the effect of telo boxes on expression was only observed in exponentially-growing cell cultures or in cycling cells of root primordia and young leaves [11-13]; (iii) among the yeast genes up-regulated in an rpg-dependent manner during exponential growth, genes involved in the biogenesis of ribosomes constitute a major class [38,43,44]; (iv) the interaction of Rap1p with the rpg box does not directly act as transcriptional activator but instead as a synergistic element that allows the activation by other regulatory proteins in participating in their recruitment in protein-protein interactions or in destabilizing the DNA duplex [38,45,46]. Similarly, in gain-of-function experiments, the telo box is not able by itself to activate gene expression in transgenic plants but acts in synergy with other cis-acting elements like site II motifs or TEF boxes [11,12]. Taken together, these observations support the hypothesis that there are functional similarities between the roles played by interstitial telomere motifs in plant promoters and those of the rpg box in yeast. We have estimated at about 10% the number of Arabidopsis genes harbouring a telo box within their 5' flanking regions suggesting that this element plays a much more general role than solely in the ribosome biogenesis. An intriguing question which might consequently be addressed concerns the meaning of the involvement in both yeast and angiosperms of interstitial telomere motifs in the expression of a set of genes whose expression is, at least for translation-related genes, correlated to cellular proliferation.

In contrast to that observed in vertebrates, many plant snoRNA genes are found in polycistronic clusters composed of homologous or heterologous snoRNAs [47]. Intronic snoRNA genes are frequently found in the genome of rice [26,27] whereas they are the exception in Arabidopsis [48]. There is currently little information on how the expression of plant snoRNA genes is coordinated with the expression of other components involved in the biogenesis of the translational apparatus. When nested within introns of genes involved in ribosome biogenesis such as fibrillarin SnRNP genes in Arabidopsis or several rp genes in O. sativa the co-expression process appears to be obvious. This co-expression process is much less clear when snoRNAs are expressed from independent promoters in non-intronic genes. Some plant non-intronic snoRNAs are RNA polymerase III products as suggested in Arabidopsis and rice by the characterization of dicistronic tRNA-snoRNA genes [47,49]. However, it remains to assess the proportion of non-intronic snoRNAs that are transcribed by pol III in plants. Our data suggest that, at least in Arabidopsis, this is probably the exception rather than the rule. The remarkable conservation of the topological association of telo boxes with site II motifs or TEF boxes observed in promoters of genes encoding ribosomal proteins or proteins required for pre-rRNA processing as well as within sequences found upstream of non-intronic snoRNA genes, strongly suggests that the association of these cis-acting elements and their interaction with related trans-acting factors might play a fundamental role in their coordinated transcription by RNA pol II. Moreover, we took advantage of the availability of TIGR-CERES data on the sequencing of full length Arabidopsis cDNAs to map the 5' end of several snoRNA precursors (Additional Files 3 and 4). These full-length cognate cDNAs were obtained by the "cap-trapping" method indicating that the identified RNA precursor molecules harbouring snoRNAs are indeed capped and polyadenylated RNA pol II transcripts. Once again, and as for rp genes, a parallel can be drawn between the putative role played by the telo box in plants and those achieved by the yeast rpg box in snoRNA gene expression. In S. cerevisiae the promoters of non-intronic snoRNA genes contain rpg boxes which are required for their full expression [50]. Thus, the analysis of conserved associations of telo boxes with site II motifs or TEF boxes allowed us to characterize new RNA pol II promoters involved in the biosynthesis of snoRNA precursors. A first analysis suggest that such an approach could be generalized to identify unexpected cryptic RNA pol II promoters within plant genomes (Figure 7). It would be of interest to investigate to what extent such promoters participate in the activation of expression in meristematic cycling cells, as is the case for plant rp or pre-rRNA processing genes showing a similar promoter configuration.

Conclusion

The data reported in this work support the model previously proposed for the way telo boxes spread within plant genomes and provide new insights into a putative process for the acquisition of microsatellites in plants. The conserved topological association of telo boxes with site II or TEF1 cis-acting elements appears to be an essential feature of plant genes involved in the biogenesis of ribosomes and clearly indicates that most plant snoRNAs are RNA pol II products. This conserved association could provide a powerful tool to improve genome annotation in characterizing new cryptic RNA pol II promoters.

Methods

Sequence data sources

Analysis of Arabidopsis sequences was carried out using the TAIR9 datasets http://www.arabidopsis.org. The analysis conducted by using the TAIR9 5'UTR (DNA) and the TAIR9 3' UTR (DNA) datasets does not include the sequences of putative introns within the 5' or 3' flanking non coding regions. The Arabidopsis rRNA processing protein and snoRNA genes were obtained from TAIR.

The O. sativa genome annotation data version 5 was downloaded from the Rice Genome Annotation Project database http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/. The "all.UTR" file containing the UTR sequences for 34793 gene models of the 12 pseudomolecules was used. The sequence of 5' flanking regions of rice ribosomal protein gene were extracted from the Ribosomal Protein Gene database http://ribosome.miyazaki-med.ac.jp/. The list of putative rice snoRNA and accession numbers were obtained from the literature [27]. For each rice snoRNA, we extracted the Genbank sequence by using its accession number. All the snoRNA were searched for in the complete genomic sequence of Oryza sotiva by using NCBI Blastn with default parameters. Some of the clusters of snoRNA were obtained from the NCBI nucleotides database and were used to assign snoRNA to clusters. Others were assigned by using their chromosomic location and their positions on the chromosome. 60 clusters (instead of 68 given in Chen et al. [27]) were assigned to chromosomic loci thanks to the list of snoRNA given for each cluster. We also proposed some new clusters. For clusters 35, 36 and 37, it was not possible to assign snoRNA to clusters precisely. Nor was it possible to assign each sequence to a chromosomic region in the complete sequence of Oryza sotiva. Indeed, for some of the snoRNA we did not find significant similarities to anything in the entire genome of Oryza. sativa.

Motifs search

The command line version of the PatMatch software [51] was used to scan the different compartments of the genome for the presence of several nucleotide patterns: telo box (AAACCCTA) and 6 associated permutations of the telo box motif (AACCCTAA, ACCCTAAA, CCCTAAAC, CCTAAACC, CTAAACCC and TAAACCCT); a control sequence (AAACCTCA), and 6 associated permutations (AACCTCAA, ACCTCAAA, CCTCAAAC, CTCAAACC, TCAAACCT and CAAACCTC); the site II motifs (TGGGCY); the TEF1 box (ARGGRYNNNNNGYA); the (GCC)6 and (GAA)6 microsatellite motifs; and the (Y)18 pyrimidine block.

For protein coding genes, a region of 500 nt was scanned upstream of the translation initiation codon. In the case of snoRNA genes, for each cluster found in an ORF, a region of 1000 nt was extracted in the 5' region before the ATG of the host gene. For each cluster found in an intergenic region, 1000 nt were extracted before the beginning of the first snoRNA of the cluster. For individual snoRNA, a region of 1000 nt was extracted just before the beginning of the 5' region of the mature snoRNA.

Chi-square analysis

The expected frequency of telo-box motif in each genome compartment under the assumption of a uniform distribution in the genome was determined as the ratio of each compartment size to the genome size. For each compartment, a chi-square test was performed between observed and expected counts of telo-box motif as compared to observed and expected counts in the rest of the genome. A combined chi-square test was performed as the sum over compartments of the square of the difference between observed and expected counts divided by expected count.

Mapping of cDNA

Putative transcripts located downstream of associations of telo boxes with site II motifs or TEF1 boxes were characterized by using sequences located downstream of these associations, Blastn and A. thaliana GB experimental cDNA/EST or Green Plant GB experimental cDNA/EST datasets.

Authors' contributions

BL designed the study, realized all the analysis on A. thaliana and wrote the manuscript. JFR contributed to search for motifs and their statistical analysis in O. sativa. CG contributed to search for snoRNA and the analysis of their 5' flanking region in O. sativa. All authors contributed to editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

This file contains a table showing in O. sativa the location of telo boxes, site II motifs, TEF1 boxes and transcription start sites (TSS) relative to the translation initiation codon of ribosomal protein genes.

This file contains a table (table 2A) showing in A. thaliana the location of telo boxes, site II motifs, TEF1 boxes and transcription start sites relative to the translation initiation codon of genes annotated in TAIR as encoding protein involved in rRNA processing. In table 2B is shown the occurrence of telo boxes in O. sativa orthologous genes.

This file contains a table showing in A. thaliana the location of telo boxes, site II motifs, TEF1 boxes and transcription start sites of snoRNA precursors relative to the 5' end of the first mature snoRNA in independent clusters, the 5' end of the mature orphan snoRNA or relative to the translation initiation codon when snoRNA genes are nested within a protein coding gene.

This file contains a table showing in O. sativa the location of telo boxes, site II motifs, TEF1 boxes and transcription start sites of snoRNA precursors relative to the 5' end of the first mature snoRNA in independent clusters, the 5' end of the mature orphan snoRNA or relative to the translation initiation codon when snoRNA genes are nested within a protein coding gene.

This file contains a table giving the chromosomic location and positions of snoRNAs.

Contributor Information

Christine Gaspin, Email: Christine.Gaspin@toulouse.inra.fr.

Jean-François Rami, Email: rami@cirad.fr.

Bernard Lescure, Email: bepal.lescure@gmail.com.

References

- Swarbreck D, Wilks C, Lamesch P, Berardini TZ, Garcia-Hernandez M, Foerster H, Li D, Meyer T, Muller R, Ploetz L, Radenbaugh A, Singh S, Swing V, Tissier C, Zhang P, Huala E. The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR): gene structure and function annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008. pp. D1009–D1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bülow L, Engelmann S, Schindler M, Hehl R. AthaMap, integrating transcriptional and post-transcriptional data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009. pp. D983–D986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Axelos M, Bardet C, Liboz T, Le Van Thai A, Curie C, Lescure B. The gene family encoding the translation elongation factor eEF1A: molecular cloning, characterization and expression. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;219:106–112. doi: 10.1007/BF00261164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liboz T, Bardet C, Le Van Thai A, Axelos M, Lescure B. The four members of the gene family encoding the translation elongation factor eEF1a are actively transcribed. Plant Mol Biol. 1990;14:107–110. doi: 10.1007/BF00015660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regad F, Hervé C, Marinx O, Bergounioux C, Tremousaygue D, Lescure B. The Tef1 box, an ubiquitous cis-acting element involved in the activation of plant genes that are highly expressed in cycling cells. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;248:703–711. doi: 10.1007/BF02191710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards E, Ausubel F. Isolation of a higher eukaryotic telomere from Arabidopsis thaliana. Cell. 1988;53:127–136. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90494-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastie ND, Allshire RC. Human telomeres: fusion and interstitial sites. Trends Genet. 1989;5:326–331. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(89)90137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida W, Matsunaga S, Sugiyama R, Kawano S. Interstitial telomere-like repeats in the Arabidopsis thaliana genome. Genes Genet Syst. 2002;77:63–67. doi: 10.1266/ggs.77.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regad F, Lebas M, Lescure B. Interstitial telomere repeats within the Arabidopsis thaliana genome. J Mol Biol. 1994;239:163–169. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandepoele K, Casneuf T, Van de Peer Y. Identification of novel regulatory modules in dicotyledonous plants using expression data and comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R103. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-11-r103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremousaygue D, Garnier L, Bardet C, Dabos P, Hervé C, Lescure B. Internal telomeric repeats and 'TCP domain' protein-binding sites co-operate to regulate gene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana cycling cells. Plant J. 2003;33:957–966. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manevski A, Bardet C, Tremousaygue D, Lescure B. In synergy with various cis-acting elements, plant interstitial telomere motifs regulate gene expression in Arabidopsis root meristems. FEBS Lett. 2000;483:43–46. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)02056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremousaygue D, Manevski A, Bardet C, Lescure N, Lescure B. Plant interstitial motifs participate in the control of gene expression in root meristems. Plant J. 1999;20:553–561. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curie C, Liboz T, Bardet C, Gander E, Médale C, Axelos M, Lescure B. Cis- and trans-acting elements involved in the activation of Arabidopsis thaliana A1 gene encoding the translation elongation factor eEF1a. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:1305–1310. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.6.1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheer I, Ludevid M, Regad F, Lescure B, Pont-Lezica R. Expression of a gene encoding a ribosomal p40 protein and identification of an active promoter site. Plant Mol Biol. 1997;35:905–913. doi: 10.1023/A:1005956601270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosugi S, Ohashi Y. PCF1 and PCF2 specifically bind to cis elements in the rice proliferating cell nuclear antigen gene. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1607–1619. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.9.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höfte H, Desprez T, Amselem J, Chiapello H, Caboche M, Moisan A, Jourjon MF, Charpenteau JL, Berthomieu P, Guerrier D, Giraudat J, Quigley F, Thomas F, Yu DY, Mache R, Raynal M, Cooke R, Grellet F, Delseny M, Parmentier Y, Marcillac G, Gigot C, Fleck J, Philipps G, Axelos M, Bardet B, Tremousaygue D, Lescure B. An inventory of 1152 expressed sequence tags obtained by partial sequencing of cDNAs from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1993;4:1041–1061. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1993.04061051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke R, Raynal M, Laudié M, Grellet F, Delseny M, Morris PC, Guerrier D, Giraudat J, Quigley F, Clabault G, Li YF, Mache R, Krivitzky M, Gy IJJ, Kreis M, Lecharny A, Parmentier Y, Marbach J, Fleck J, Clément B, Philipps G, Hervé C, Bardet C, Tremousaygue D, Lescure B, Lacomme C, Roby D, Jourjon MF, Chabrier P, Charpenteau JL, Desprez T, Amselem J, Chiapello H, Höfte H. Further progress towards a catalogue of all Arabidopsis genes: analysis of a set of 5000 non-redundant ESTs. Plant J. 1996;9:101–124. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1996.09010101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimori S, Washio T, Higo K, Ohtomo Y, Murakami K, Matsubara K, Kawai J, Carninci P, Hayashizaki Y, Kikuchi S, Tomita M. A novel feature of microsatellites in plants: a distribution gradient along the direction of transcription. FEBS Lett. 2003;554:17–22. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)01041-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Yuan D, Yu S, Li Z, Cao Y, Miao Z, Quian H, Tag K. Preference of simple sequence repeats in coding and non-coding regions of Arabidopsis thaliana. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1081–1086. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Xue Q. Tri-nucleotide repeats and their association with genes in rice genome. Biosystems. 2005;82:248–256. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystems.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina C, Grotewold E. Genome wide analysis of Arabidopsis core promoters. BMC Genomics. 2005;6:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, Ichida H, Abe T, Suzuki Y, Sugano S, Obokata J. Differentiation of core promoter architecture between plants and mammals revealed by LDSS analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:6219–6226. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover H, Aishwarya V, Sharma PC. Biased distribution of microsatellite motifs in the rice genome. Mol Genet Genomics. 2007;277:469–480. doi: 10.1007/s00438-006-0204-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conte MG, Gaillard S, Lanau N, Rouard M, Périn C. GreenPhylDB: a database for plant comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008. pp. D991–D998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Liang D, Zhou H, Zhang P, Chen YQ, Chen X, Chen CL, Qu LH. A novel gene organization: intronic snoRNA gene clusters from Oryza sativa. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3262–3272. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CL, Liang D, Zhou H, Zhou M, Chen YQ, Qu LH. The high diversity of snoRNAs in plants: Identification and comparative study of 120 snoRNA genes from Oryza sativa. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2601–2613. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santi L, Wang Y, Stile MR, Berendzen K, Wanke D, Roig C, Pozzi C, Muller K, Muller J, Rohde W, Salamini F. The GA octodinucleotide repeat binding factor BBR participates in the transcriptional regulation of the homeobox gene Bkn3. Plant J. 2003;34:813–826. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooiker M, Airoldi CA, Losa A, Manzotti PS, Finzi L, Kater MM, Colombo L. BASIC PENTACYSTEINE1, a GA binding protein that induces conformational changes in the regulatory region of the homeotic Arabidopsis gene SEEDSTICK. Plant Cell. 2005;17:722–729. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.030130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas A. Relationship between transcription and initiation of meiotic recombination: Toward chromatin accessibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:87–89. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera A. The connection between transcription and genomic instability. EMBO J. 2002;21:195–201. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.3.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drolet M. Growth inhibition mediated by negative supercoiling: the interplay between transcription elongation, R-loop formation and DNA topology. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59:723–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.05006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M, Blackburn EH. Sequence-specific DNA primer effects on telomerase polymerization activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:6586–6599. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.6586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren S, Johnston JS, Shippen DE, McKnight TD. Telomerase Activator1 induces telomerase activity and potentiates responses to auxin in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2004;16:2910–2922. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.025072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadir E, Margalit H, Gallily T, Ben-Sasson SA. Microsatellite spreading in the human genome: Evolutionary mechanisms and structural implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6470–6475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodniewicz-Proba T, Buchowicz J. Properties of a deoxyribonucleotidyltransferase isolated from wheat germ. Biochem J. 1980;191:139–145. doi: 10.1042/bj1910139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauss GH, Lieber MR. Mechanistic constraints on diversity in human V(D)J recombination. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:258–269. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.1.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planta RJ, Gonçalves PM, Mager WH. Global regulators of ribosome biosynthesis in yeast. Biochem Cell Biol. 1995;73:825–834. doi: 10.1139/o95-090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogues H, Lavoie H, Sellam A, Mangos M, Roemer T, Purisima E, Nantel A, Whiteway M. Transcription factor substitution during the evolution of fungal ribosome regulation. Mol Cell. 2008;29:552–562. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Li X. Transcriptional regulation in eukaryotic ribosomal protein genes. Genomics. 2007;90:421–423. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curie C, Axelos M, Bardet C, Atanassova R, Chaubet N, Lescure B. Modular organization and developmental activity of an Arabidopsis thaliana eEF1a gene promoter. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;238:428–436. doi: 10.1007/BF00292002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore D. Telomerase and telomere binding proteins: controlling the endgame. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:233–235. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(97)01082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner JR. The economics of ribosome biosynthesis in yeast. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:437–440. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01460-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieb JD, Liu X, Botstein D, Brown PO. Promoter-specific binding of Rap1 revealed by genome-wide maps of protein-DNA association. Nat Genet. 2001;28:327–334. doi: 10.1038/ng569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tornow J, Zeng X, Santangelo GM. GCR1, a transcriptional activator in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, complexes with RAP1 and can function without DNA binding domain. EMBO J. 1993;12:2431–2437. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05897.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu EY, Morse RH. Chromatin opening and transactivator potentiation by RAP1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5279–5288. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JWS, Echeverria M, Qu L-H. Plant snoRNAs: functional evolution and new modes of gene expression. Trends Plant Sci. 2003;8:42–49. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)00007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JWS, Clark GP, Leader DJ, Simpson CG, Lowe T. Multiple snoRNA gene clusters from Arabidopsis. RNA. 2001;7:1817–1832. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruszka K, Barneche F, Guyot R, Ailhas J, Meneau I, Schiffer S, Marchfeler A, Echeverria M. Plant dicistronic tRNA-snoRNA genes: a new mode of expression of the small nucleolar RNAs processed by Rnase Z. EMBO J. 2003;22:621–632. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu LH, Henras A, Lu YJ, Zhou H, Zhou WX, Zhu YQ, Zhao J, Henry Y, Caizergues-Ferrer M, Bachellerie Y. Seven novel methylation guide small nucleolar RNAs are processed from a common polycystronic transcript by Rat1p and Rnase III in yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1144–1158. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan T, Yoo D, Berardini TZ, Mueller LA, Weems DC, Weng S, Cherry JM, Rhee ST. A program for finding patterns in peptide and nucleotide sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(suppl_2):W262–W266. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

This file contains a table showing in O. sativa the location of telo boxes, site II motifs, TEF1 boxes and transcription start sites (TSS) relative to the translation initiation codon of ribosomal protein genes.

This file contains a table (table 2A) showing in A. thaliana the location of telo boxes, site II motifs, TEF1 boxes and transcription start sites relative to the translation initiation codon of genes annotated in TAIR as encoding protein involved in rRNA processing. In table 2B is shown the occurrence of telo boxes in O. sativa orthologous genes.

This file contains a table showing in A. thaliana the location of telo boxes, site II motifs, TEF1 boxes and transcription start sites of snoRNA precursors relative to the 5' end of the first mature snoRNA in independent clusters, the 5' end of the mature orphan snoRNA or relative to the translation initiation codon when snoRNA genes are nested within a protein coding gene.

This file contains a table showing in O. sativa the location of telo boxes, site II motifs, TEF1 boxes and transcription start sites of snoRNA precursors relative to the 5' end of the first mature snoRNA in independent clusters, the 5' end of the mature orphan snoRNA or relative to the translation initiation codon when snoRNA genes are nested within a protein coding gene.

This file contains a table giving the chromosomic location and positions of snoRNAs.