Abstract

Study Objectives:

To examine how self-reported ratings of sleep disturbance changed from the time of the simulation visit to four months after the completion of radiation therapy (RT) and to investigate whether specific patient, disease, and symptom characteristics predicted the initial levels of sleep disturbance and/or characteristics of the trajectories of sleep disturbance.

Design:

Prospective longitudinal study.

Setting:

Two radiation therapy centers.

Patients:

Patients (n = 82) who underwent primary or adjuvant RT for prostate cancer.

Measurements and Results:

Changes in self-reported sleep disturbance were measured using the General Sleep Disturbance Scale (GSDS). Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale. Trait and state anxiety were measured using the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Hierarchical linear modeling was used to answer the study aims. Self-reported sleep disturbance increased during the course of RT and then decreased following the completion of RT. Predictors of higher levels of sleep disturbance included younger age, higher levels of trait anxiety, higher levels of depressive symptoms, and higher levels of sleep disturbance at the initiation of RT.

Conclusions:

Sleep disturbance is a significant problem in patients with prostate cancer who undergo RT. Younger men with co-occurring depression and anxiety may be at greatest risk for sleep disturbance during RT.

Citation:

Miaskowski C; Paul SM; Cooper BA; Lee K; Dodd M; West C; Aouizerat BE; Dunn L; Swift PS; Wara W. Predictors of the trajectories of self-reported sleep disturbance in men with prostate cancer during and following radiation therapy. SLEEP 2011;34(2):171-179.

Keywords: Sleep disturbance, insomnia, prostate cancer, radiation therapy, hierarchical linear modeling, symptom trajectories

RECENT STUDIES SUGGEST THAT SLEEP DISTURBANCE OCCURS IN 30% TO 50% OF ONCOLOGY PATIENTS, COMPARED TO A 20% PREVALENCE RATE IN the general population.1,2 However, most of these sleep studies were cross-sectional in nature and included patients with a variety of cancer diagnoses. Taken together, findings from these studies suggest that sleep disturbance has a negative impact on patients' functional status and quality of life (QOL). However, additional research is warranted within specific cancer diagnoses to determine how sleep disturbance changes over the course of treatment and what factors predict changes in sleep disturbance.

Prostate cancer is the most common type of cancer in men, with 192,280 new cases diagnosed annually in the United States.3 The disease itself and its associated treatments place men at high risk for sleep disturbance, particularly with bladder irritation and frequent voiding associated with radiation therapy (RT)4,5 and with hot flashes during hormonal therapy.6–8 However, only a limited number of cross-sectional studies have evaluated sleep disturbance in men with prostate cancer. In one of the earliest studies of men treated with radical prostatectomy, 32% of the patients reported sleep disturbance as a clinically significant symptom and 18% met diagnostic criteria for insomnia syndrome.9 Predictors of sleep disturbance included presence of intestinal, urinary, and androgen-blockade related symptoms, pain, and anxiety, as well as being unmarried and not having undergone RT. Predictors of insomnia syndrome included younger age, not having undergone RT, worse clinical prognosis, and the presence of intestinal pain, depressive, and androgen-blockade related symptoms.

In a more recent cross-sectional study,10 the relationships between sleep disturbance and depression and distress were evaluated in a sample of prostate cancer patients who were undergoing a variety of treatments. Over 50% of the patients in this study reported clinically significant levels of sleep disturbance and significant positive correlations were found between the severity of sleep disturbance and depression (r = 0.39, P = 0.005) and distress (r = 0.33, P = 0.02). Findings from both of these studies demonstrate that sleep disturbance is a significant problem in men with prostate cancer. In addition, they provide preliminary evidence of potential predictors that may place men at greater risk for this symptom. However, no studies were identified that evaluated for changes in sleep disturbance in men with prostate cancer prior to and following the completion of a course of RT. Therefore, the purposes of this study, in a sample of patients who underwent RT for prostate cancer, were: to examine how self-reported ratings of sleep disturbance changed from the time of the simulation visit to 4 months after the completion of RT, and to investigate whether specific patient, disease, and symptom characteristics predicted the initial levels of sleep disturbance and/or characteristics of the trajectories of sleep disturbance. These analyses were conducted using a more sophisticated statistical method, namely hierarchical linear modeling (HLM), to account for variability in the number and the spacing of the assessments across individuals.11,12

METHODS

Participants and Settings

This descriptive, longitudinal study is part of a larger study that evaluated multiple symptoms in patients with breast, prostate, lung, and brain cancer who underwent RT.13–15 For this study, 82 men with prostate cancer were recruited who met the following inclusion criteria: adults (> 18 years of age) who were able to read, write, and understand English; had a Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) score ≥ 60; and were scheduled to receive primary or adjuvant RT. Patients were excluded if they had metastatic disease, had more than one cancer diagnosis, or had a diagnosed sleep disorder. They were recruited from RT departments located in a Comprehensive Cancer Center and a community-based oncology program. This study was approved by the Human Subjects Committee at the University of California, San Francisco and at the second study site.

One hundred eighty-eight patients with prostate cancer were approached, and 82 consented to participate in the longitudinal study (43.6% response rate). The major reasons for refusal were: being too overwhelmed with their cancer experience or too busy. No differences were found in any of the demographic or disease characteristics between patients who did and did not choose to participate in this study.

Instruments

The study instruments included a demographic questionnaire, the KPS scale,16,17 the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI),18 the General Sleep Disturbance Scale (GSDS),19 the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D),20 the Spielberg State-Trait Anxiety Inventories (STAI-S and STAI-T),21 a descriptive numeric rating scale (NRS) for worst pain intensity,22 and the Lee Fatigue Scale (LFS).23

The demographic questionnaire provided information on age, marital status, years of education, living arrangements, ethnicity, and employment status. In addition, patients completed a checklist of comorbidities.

The PSQI was administered at baseline. The PSQI consists of 19 items designed to assess the quality of sleep in the past month. The global PSQI score is the sum of the 7 component scores (subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication, daytime dysfunction). Each component score ranges from 0 to 3, and the global PSQI score ranges from 0 to 21. Higher global and component scores indicate more severe complaints and a higher level of sleep disturbance. A global PSQI score > 5 indicates a significant level of sleep disturbance.18 A cutoff score of 8 was found to discriminate poor sleep quality in oncology patients.24 The PSQI has established internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and construct validity.18,24,25 In this study, the Cronbach α for the global PSQI score was 0.72.

To estimate changes in self-reported sleep disturbance, the GSDS was administered at each time point. The GSDS consists of 21 items designed to assess the quality of sleep in the past week. Each item was rated on a 0 (never) to 7 (every day) numeric rating scale (NRS). The GSDS total score is the sum of the 7 subscale scores (quality of sleep, quantity of sleep, sleep onset latency, mid-sleep awakenings, early awakenings, medications for sleep, excessive daytime sleepiness) that can range from 0 (no disturbance) to 147 (extreme sleep disturbance). Each mean subscale score can range from 0 to 7. Higher total and subscale scores indicate higher levels of sleep disturbance. Mean subscale scores ≥ 3 and a GSDS total score ≥ 43 indicate a significant level of sleep disturbance.26 The GSDS has well-established validity and reliability in shift workers, pregnant women, and patients with cancer and HIV.19,27,28 In the current study, the Cronbach α for the GSDS total score was 0.81.

The CES-D consists of 20 items selected to represent the major symptoms in the clinical syndrome of depression. Scores can range from 0 to 60, with scores ≥ 16 indicating the need for individuals to seek clinical evaluation for major depression. The CES-D has well-established concurrent and construct validity.20,29,30 In the current study, the Cronbach α for the CES-D was 0.83.

The STAI-T and STAI-S inventories consist of 20 items each that are rated from 1 to 4. The scores for each scale are summed and can range from 20 to 80. A higher score indicates greater anxiety. The STAI-T measures an individual's predisposition to anxiety determined by his/her personality and estimates how a person feels generally. The STAI-S measures an individual's transitory emotional response to a stressful situation. It evaluates the emotional response of worry, nervousness, tension, and feelings of apprehension related to how people feel “right now” in a stressful situation. The STAI-S and STAI-T inventories have well-established criterion and construct validity and internal consistency reliability coefficients.21,31,32 In this study, the Cronbach α was 0.86 for the STAI-T and 0.91 for the STAI-S.

Worst pain intensity was evaluated using a descriptive NRS that ranged from 0 (no pain) to 10 (excruciating pain). A descriptive NRS is a valid and reliable measure of pain intensity.22 Because the majority of the patients did not have pain (74.4%), for the subsequent longitudinal analyses, pain was recoded as present or absent.

Fatigue severity was measured using the 13-item LFS. Each item is rated using a 0 to 10 NRS, and a total score is calculated as the mean of the 13 items that can range from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating higher levels of fatigue severity. Respondents were asked to rate each item based on how they felt “right now,” within 30 minutes of awakening (i.e., morning fatigue) and prior to bed (i.e., evening fatigue). The LFS has been used with healthy individuals as well as in patients with cancer and HIV.27,28,33 It was chosen for the current study because it is relatively short and easy to administer. The LFS has well established validity and reliability.23,34 In this sample, the Cronbach α for the LFS was 0.95 for evening ratings and 0.96 for morning ratings.

Study Procedures

At the time of the simulation visit that occurred approximately 1 week prior to the start of RT, patients were approached by a research nurse to discuss participation in the study. The simulation is the visit where the patient's treatment plan is formulated, measurements are taken, and the patient's skin is marked in order to insure that the patient is positioned correctly and in the same way for each RT treatment. After patients gave written informed consent, they were asked to complete the baseline study questionnaires. Patients completed the GSDS prior to the initiation of RT, every other week for 6 weeks, at the end of RT, and once a month for 4 months after the completion of RT. Every patient provided data for a minimum of at least 7 of the 9 assessments of self-reported sleep disturbance.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics and frequency distributions were generated on the sample characteristics and baseline symptom severity scores using SPSS Version 15.0. For each of the 9 assessments, a GSDS total score was calculated for use in the subsequent statistical analyses.

HLM, based on full maximum likelihood estimation, was done using the software developed by Raudenbush and colleagues.11 The repeated measures of sleep disturbance were conceptualized as being nested within individuals. Compared with other methods of analyzing change, HLM has 2 major advantages. First, HLM can accommodate unbalanced designs which allows for the analysis of data when the number and the spacing of the assessments vary across respondents. Although every patient was to be assessed on a pre-specified schedule, the actual number of assessments was not the same for all of the patients, because some patients had longer periods of RT and some had scheduling conflicts. Second, HLM has the ability to model individual change, which helps to identify more complex patterns of change that are often overlooked by other methods.11,35

With HLM, the repeated measures of the outcome variable (sleep disturbance) are nested within individuals and the analysis of change in sleep disturbance scores has 2 levels: within persons (Level 1) and between persons (Level 2). At Level 1, the outcome is conceptualized as varying within individuals and is a function of person-specific change parameters plus error. At Level 2, these person-specific change parameters are multivariate outcomes that vary across individuals. These Level 2 outcomes can be modeled as a function of demographic or clinical characteristics that vary between individuals, plus an error associated with the individual. Combining Level 1 with Level 2 results in a mixed model with fixed and random effects.11,36,37

Each HLM analysis proceeded in 2 stages. First, intra-individual variability in sleep disturbance over time was examined. In this study, time in weeks refers to the length of time from the simulation visit to 4 months after the completion of RT (6 months with a total of 9 assessments). Three Level 1 models, which represented that the patients' level of sleep disturbance (a) did not change over time (no time effect), (b) changed at a constant rate (linear time effect), and (c) changed at a rate that accelerated or decelerated over time (quadratic effect) were compared. At this point, the Level 2 model was constrained to be unconditional (no predictors), and likelihood ratio tests were used to determine the best model. These analyses answered the first research aim and identified the change parameters that best described individual changes in sleep disturbance over time.

The second stage of the HLM analysis, which answered the second aim, examined inter-individual differences in the trajectory of sleep disturbance by modeling the individual change parameters (intercept, linear, and quadratic slopes) as a function of proposed predictors at Level 2. Table 1 presents a list of the proposed predictors that was developed based on a review of the literature of sleep disturbance in men with prostate cancer who underwent RT. The predictors are organized using the theory of symptom management (TSM) that served as the conceptual framework for the larger study.38–40 The TSM is a multidimensional model that includes 3 dimensions of symptoms (symptom experience, symptom management strategies, and symptom outcomes). The 3 dimensions of the symptom are influenced by the 3 domains of nursing (person, environment, and health and illness). This study focused on the symptom experience of sleep disturbance within the context of the 3 domains of nursing.

Table 1.

Potential predictors of intercept, linear coefficient, and quadratic coefficient for general sleep disturbance total score

| Potential Predictors | Intercept | Linear Coefficient | Quadratic Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| Person | |||

| Age | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Lives alone | |||

| Marital status | |||

| Education | |||

| Employment status | |||

| Disease and Treatment | |||

| KPS Score | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ |

| Number of comorbidities | |||

| Pretreatment PSA | |||

| Gleason score | |||

| Total dose of RT received | |||

| Hormonal therapy prior to RT | |||

| Symptoms | |||

| Baseline CES-D score | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ |

| Presence of pain at baseline | |||

| Baseline trait anxiety score | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ |

| Baseline state anxiety score | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ |

= From exploratory analyses had a t-value > 2.00.

CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression; KPS, Karnofsky Performance Status, RT, radiation therapy.

To improve estimation efficiency and construct a model that was parsimonious, an exploratory Level 2 analysis was done in which each potential predictor was assessed to see if it would result in a better fitting model if it alone was added as a Level 2 predictor. Predictors with a t-value < 2.0, which indicates lack of significant effect, were dropped from subsequent model testing. All of the potentially significant predictors from the exploratory analyses were entered into the model to predict each individual change parameter. Only predictors that maintained a significant contribution in conjunction with other variables were retained in the final model. A P-value < 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics and Symptom Severity Scores

The demographic, disease, and treatment characteristics of the 82 patients are presented in Table 2. These men with prostate cancer were approximately 67 years of age, were well educated, and had a mean KPS score of 95.7. Most of the patients were married or partnered (69.5%), white (76.8%), and not employed (53.7%). The distribution of clinical stage of disease was 48.8% with T1, 42.5% with T2, and 8.8% with T3. About half (51.2%) of the patients received hormonal therapy prior to the initiation of RT. The mean symptom severity scores for the 82 patients at the time of the simulation visit are listed in Table 2. Baseline subscale and total scores for the PSQI and the GSDS are presented in Table 3.

Table 2.

Demographic, disease, and treatment characteristics and baseline symptom severity scores of the patients (n = 82)

| Characteristic | Mean (Standard Deviation) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 67.1 (7.8) |

| Education (years) | 16.0 (3.2) |

| Karnofsky Performance Status Score | 95.7 (6.9) |

| Number of comorbidities | 4.6 (2.5) |

| Lives alone | 23.2% |

| Marital status | |

| Married/partnered | 69.5% |

| Divorced/separated | 13.4% |

| Other | 17.1% |

| Ethnicity | |

| Black | 18.3% |

| White | 76.8% |

| Other | 4.9% |

| Employed | |

| Yes | 46.3% |

| No | 53.7% |

| Pre-treatment PSA level (ng/mL) | 10.9 (7.9) |

| Gleason score | |

| 5 or 6 | 39.0% |

| 7 | 47.7% |

| ≥8 | 13.4% |

| Mean Gleason score | 6.8 (0.9) |

| Mean hemoglobin level (g/dL) | 14.4 (1.2) |

| Mean hematocrit (%) | 42.3 (3.7) |

| Clinical stage | |

| T1 | 48.8% |

| T2 | 42.5% |

| T3 | 8.8% |

| Time since diagnosis (months) | 8.9 (12.7) |

| Prostatectomy prior to RT | 9.8% |

| Hormonal therapy prior to RT | 51.2% |

| RT treatment plan | |

| Whole pelvis + conformal boost after surgery | 9.8% |

| Whole pelvis + conformal boost | 75.6% |

| Whole pelvis + high dose RT | 4.9% |

| Whole pelvis + seed implant | 9.8% |

| Total dose of RT (cGys) | 6902 (958.2) |

| Mean symptom severity scores at baseline | |

| GSDS score | 33.4 (16.3) |

| LFS score for evening fatigue | 3.5 (2.1) |

| LFS score for morning fatigue | 1.8 (1.8) |

| CES-D score | 5.9 (5.7) |

| Trait Anxiety Inventory score | 31.3 (7.9) |

| State Anxiety Inventory score | 27.8 (7.8) |

CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale; GSDS, General Sleep Disturbance Scale; LFS, Lee Fatigue Scale; PSA, prostate specific antigen; RT, radiation therapy.

Table 3.

Baseline Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) Subscale and Global Scores, and General Sleep Disturbance (GSDS) Subscale and Global Scores of the Patients (n = 82)

| Mean (Standard Deviation) | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| PSQI Scores (range of possible scores) | ||

| Sleep quality (0 to 3) | 0.90 (0.64) | 0 to 3 |

| Sleep latency (0 to 3) | 0.67 (0.77) | 0 to 3 |

| Sleep duration (0 to 3) | 0.86 (0.85) | 0 to 3 |

| Habitual sleep efficiency (0 to 3) | 0.56 (0.86) | 0 to 3 |

| Sleep disturbances (0 to 3) | 1.26 (0.52) | 0 to 2 |

| Use of sleep medications (0 to 3) | 0.44 (0.98) | 0 to 3 |

| Daytime dysfunction (0 to 3) | 0.60 (0.61) | 0 to 2 |

| Global PSQI score (0 to 21) | 5.25 (2.93) | 0 to 14 |

| GSDS scores (range of possible scores) | ||

| Quality of sleep (0 to 7) | 2.0 (1.6) | 0 to 6 |

| Quantity of sleep (0 to 7) | 4.2 (1.1) | 0 to 7 |

| Sleep onset latency (0 to 7) | 1.0 (1.5) | 0 to 7 |

| Mid-sleep awakenings (0 to 7) | 4.5 (2.6) | 0 to 7 |

| Early awakenings (0 to 7) | 1.9 (1.9) | 0 to 7 |

| Medications for sleep (0 to 7) | 0.25 (0.50) | 0 to 2 |

| Excessive daytime sleepiness (0 to 7) | 1.4 (1.3) | 0 to 6 |

| Total GSDS score (0 to 147) | 33.44 (16.31) | 8 to 79 |

Individual and Mean Change in Self-reported Sleep Disturbance

The first HLM analyses examined how level of sleep disturbance changed from the time of the simulation visit to 4 months after the completion of RT. Two models were estimated, one in which the function of time was linear and a second in which the function of time was quadratic. The goodness-of-fit test of the deviance between the linear and quadratic models indicated that a quadratic model fit the data significantly better than a linear model (χ2 = 41.35, df = 4, P < 0.001). In addition, the test of the quadratic coefficient in the quadratic model was significant (t = −4.78, df = 81, P < 0.001).

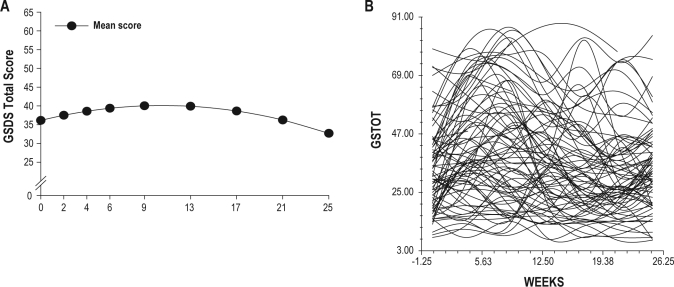

The estimates of the quadratic change model are presented in Table 4 (unconditional model). Because the model had no covariates (i.e., unconditional), the intercept represents the estimated amount of sleep disturbance based on the total GSDS score (36.09) at the time of the simulation visit. The estimated linear rate of change in sleep disturbance for each additional week was 0.72 (P < 0.05), and the estimated quadratic rate of change per week was −0.04 (P < 0.0001). It is important to remember that it is the weighted combination of the linear and quadratic terms that define each curve. Figure 1A displays the trajectory for sleep disturbance from the time of the simulation visit to 4 months after the completion of RT. Sleep disturbance increased over the course of RT (weeks 1 to 9) and then declined after the completion of RT. It should be noted that the mean sleep disturbance scores for the various groups depicted in all of the figures are estimated or predicted means based on the HLM analyses.

Table 4.

Hierarchical linear model for self-reported sleep disturbance

| General Sleep Disturbance Scale (GSDS) Total Score | Coefficient (SE) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Unconditional Model | Final Model |

| Fixed Effects | ||

| Intercept | 36.086 (1.781)* | 36.147 (1.382)* |

| Timea (linear rate of change) | 0.723 (0.195)+ | 0.753 (0.195)* |

| Time2 (quadratic rate of change) | −0.035 (0.007)* | −0.036 (0.008)* |

| Time invariant covariates | ||

| Intercept | ||

| Baseline Trait anxiety score | 0.406 (0.190)+ | |

| Baseline CES-D score | 1.428 (0.293)* | |

| Linear | ||

| Age × time | −0.051 (0.025)+ | |

| Baseline CES-D score × time | 0.102 (0.050)+ | |

| Baseline GSDS score × time | −0.040 (0.016)+ | |

| Quadratic | ||

| Age × time2 | 0.002 (0.001) | |

| Baseline CES-D score × time2 | −0.004 (0.002)+ | |

| Baseline GSDS score × time2 | 0.002 (0.001)+ | |

| Variance components | ||

| In intercept | 199.971* | 99.426+ |

| In linear rate | 0.831 | 0.909 |

| In quadratic fit | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Goodness-of-fit deviance (parameters estimated) | 4046.230 (10) | 3986.372 (18) |

| Model comparison (Χ2 [df]) | 59.858 (8)* | |

P < 0.0001;

P < 0.05.

Time was coded 0 at the time of the simulation visit.

CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression; GSDS, General Sleep Disturbance Scale; LFS, Lee Fatigue Scale; SE, standard error.

Figure 1.

(A) Trajectories of self-reported sleep disturbance measured using the General Sleep Disturbance Scale (GSDS) over the 25 weeks of the study. (B) Spaghetti plot of the 82 patients' individual trajectories of self-reported sleep disturbance using the GSDS over the 25 weeks of the study.

Although the results indicate a sample-wide increase followed by a decrease in sleep disturbance, they do not imply that all patients exhibited the same trajectory. The variance in individual change parameters estimated by the models (variance components, Table 3), suggested that substantial inter-individual differences existed in the trajectory of sleep disturbance that warranted examination of predictors of these inter-individual differences (see Figure 1B).

Inter-Individual Differences in the Trajectory of Self-reported Sleep Disturbance

As shown in the final model in Table 4, the 2 variables that predicted inter-individual differences in the intercept for sleep disturbance were baseline level of trait anxiety (baseline STAI-T score) and baseline level of depressive symptoms (baseline CES-D score). Baseline sleep disturbance (baseline GSDS score) was entered in Level 2 as a predictor of the slope parameters to control for intra-individual differences in sleep disturbance at baseline. The 3 variables that predicted inter-individual differences in the slope parameters for sleep disturbance were age, baseline level of depressive symptoms, and baseline level of sleep disturbance.

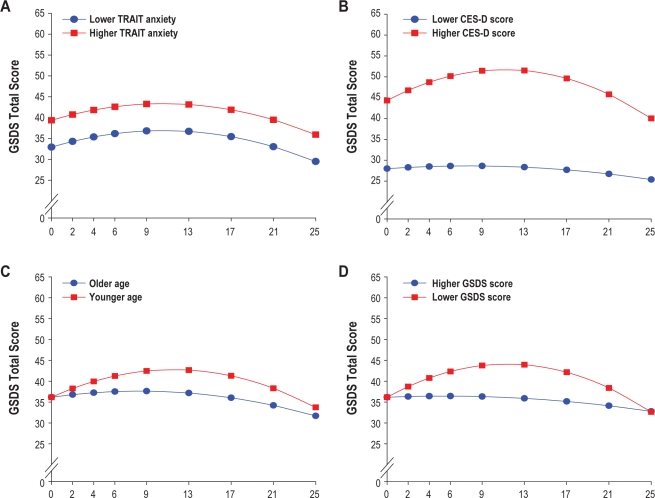

To illustrate the effects of the 4 different predictors on patients' trajectories of sleep disturbance, Figures 2A through 2D display the adjusted change curves for sleep disturbance estimated based on differences in baseline level of trait anxiety (lower/higher trait anxiety calculated based on 1 standard deviation [SD] above and below the mean STAI-T score), baseline level of depressive symptoms (lower/higher CES-D calculated based on 1 SD above and below the mean CES-D score), age (younger/older calculated based on 1 SD above and below the mean age), and baseline level of sleep disturbance (lower/higher GSDS calculated based on 1 SD above and below the mean GSDS score).

Figure 2.

Trajectories of self-reported sleep disturbance measured using the General Sleep Disturbance Scale (GSDS) by level trait anxiety at baseline (A; i.e., lower/higher TRAIT anxiety), level of depression at baseline (B; i.e., lower/higher CES-D score), age (C; i.e., older/younger), and sleep disturbance at baseline (D; i.e., lower/higher GSDS score).

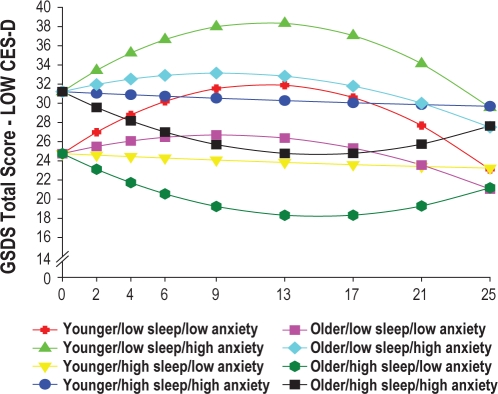

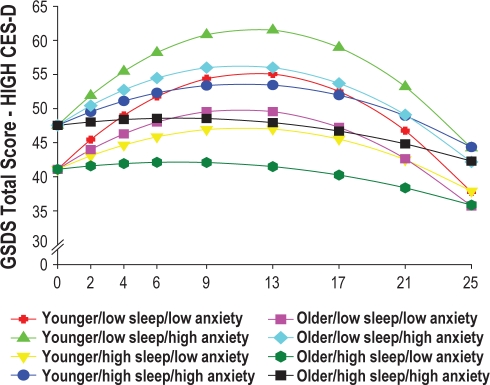

In addition, to illustrate the effects of the different predictors on patients' trajectories of sleep disturbance, Figures 3 and 4 display the adjusted change curves of sleep disturbance that were estimated based on differences in baseline levels of depression (low CES-D and high CES-D, respectively, calculated based on 1 SD above and below the mean CES-D score), as well as age, baseline level of trait anxiety, and baseline level of sleep disturbance. Rather than place 16 trajectories on a single plot, 2 figures were made to illustrate differences in sleep disturbance trajectories based on low (Figure 3) and high (Figure 4) CES-D scores.

Figure 3.

Trajectories of self-reported sleep disturbance measured using the General Sleep Disturbance Scale (GSDS) by lower level of depression at baseline (LOW CES-D) and by age (younger/older), level of sleep disturbance at baseline (low sleep/high sleep), and level of trait anxiety at baseline (low anxiety/high anxiety).

Figure 4.

Trajectories of self-reported sleep disturbance measured using the General Sleep Disturbance Scale (GSDS) by higher level of depression at baseline (HIGH CES-D) and by age (younger/older), level of sleep disturbance at baseline (low sleep/high sleep), and level of trait anxiety at baseline (low anxiety/high anxiety).

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to evaluate for inter-individual differences in self-reported sleep disturbance as well as the predictors of sleep disturbance prior to, during, and after a course of RT in men with prostate cancer. An evaluation of the unconditional model suggests that the severity of self-reported sleep disturbance increased during RT and then decreased following the completion of RT. As shown in Figure 1, when the GSDS scores for the entire sample were considered, the incremental increases in sleep disturbance over time were modest. In addition, none of them reached the clinically significant cutoff > 43 at any time during the six months of this study.

However, the use of HLM, compared to the more traditional statistical approaches that are used to evaluate for changes over time in some dependent variable (e.g., repeated measures analysis of variance), provided evidence of a large amount of inter-individual variability in the trajectories of sleep disturbance in these men with prostate cancer. In addition, the HLM analyses provided some insights into which factors may increase patients' risk for more severe and prolonged sleep disturbance trajectories given their initial status.

Estimated mean sleep disturbance scores at the time of the simulation visit ranged from 7 to 87 (actual scores ranged from 8 to 79) with 24.4% of the patients reporting a score > 43. This occurrence rate of sleep disturbance is slightly lower than previous reports of sleep disturbance, measured using the Insomnia Severity Index, in men with prostate cancer.9,10 The slightly lower rates of sleep disturbance may be related to differences in the self-report measures used across these studies. Based on the HLM analysis, patients with higher levels of trait anxiety and depression reported higher levels of sleep disturbance at the time of the simulation visit. In addition, because HLM has the ability to determine predictors, not only of the intercept but of the slopes of the trajectories of sleep disturbance, younger age as well as lower baseline levels of sleep disturbance, were identified as significant predictors of sleep disturbance.

Consistent with previous reports that used the CES-D10 or the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale,9 higher levels of depressive symptoms at the time of the simulation visit were associated with higher levels of sleep disturbance at baseline, as well as over the entire 6 months of the study (Figure 2B). While the mean CES-D score in this sample of men with prostate cancer was well below the cutoff score of 16, as illustrated in Figure 4, patients with higher CES-D scores (1 SD above the mean CES-D score) were projected to have baseline sleep disturbance scores that were above the clinically meaningful cutpoint for the GSDS. These patients' sleep disturbance scores rose over the course of RT, peaked one month after the completion of RT, and then began to decline gradually over the next three months. While depression has been shown to co-occur with sleep disturbance in the general population41,42 and in patients with cancer,43,44 the mechanisms that underlie these relationships need to be elucidated. Additional research is warranted to determine how depression and sleep disturbance change together over the course of RT.

Anxiety as a predictor of sleep disturbance has not received as much attention as depression in the oncology literature. Consistent with work by Savard and colleagues,9 trait but not state anxiety predicted higher levels of sleep disturbance at the initiation of RT. Trait anxiety scores in this sample of men were near the cutoff for clinically meaningful levels of this symptom.21 In addition, when evaluated as a predictor with depression (see Figs. 3 and 4), younger men with higher levels of trait anxiety had worse sleep disturbance trajectories. Again, research is warranted to determine how anxiety and sleep disturbance change together over the course of RT. In addition, given the deleterious effects of comorbid depressive and anxiety symptoms, even at subsyndromal levels,45 the relationship between these psychological symptoms and sleep disturbance warrant additional investigation.

Again, consistent with findings by Savard and colleagues,9 younger men in this study had higher levels of sleep disturbance. As noted by these authors, while some population-based studies suggest that sleep disturbance increases with age,46,47 other researchers suggests that other factors (e.g., medical and psychiatric disorders) may mediate the relationships between age and sleep disturbance.48 Younger men in this study may have had more trouble adapting to the changes associated with prostate cancer and its treatment that may have resulted in more sleep disturbance. In fact, an evaluation of the impact of all of the predictors on sleep disturbance (Figs. 3 and 4) suggest that in both the lower CES-D and higher CES-D groups, younger men with higher levels of state anxiety, and lower levels of sleep disturbance at baseline had the worst sleep disturbance trajectories. These findings suggest that the relationships among age, anxiety, and sleep disturbance in patients with prostate cancer warrant additional investigation.

A surprising finding from this study was that neither hormonal treatment prior to RT nor fatigue was a significant predictor of sleep disturbance in this sample. Based on an evaluation of patients' responses to the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale, only 32.5% of the sample reported night sweats prior to the initiation of RT (data not shown). In addition, both morning and evening fatigue scores in these patients were in the mild range prior to the initiation of RT. Additional research is warranted to evaluate when and which specific disease and treatment characteristics (e.g., night sweats, urinary symptoms) interfere with sleep so that more targeted interventions can be designed and tested.

Limitations of this study include the relatively small sample size, the single cancer diagnosis, the single gender, the use of only self-report measures to evaluate sleep disturbance, and the lack of a clinical evaluation of anxiety and depression. Therefore, the findings from this study cannot be generalized to cancer patients with different cancer diagnoses who undergo RT or to female patients. However, the focus on a homogeneous sample of patients with prostate cancer allowed for an evaluation of disease and treatment predictors that were specific to this cancer diagnosis. While the refusal rate for this study was relatively high (43.6%), it should be noted that the major reasons for refusal were being overwhelmed or too busy. One can speculate that the patients who refused may have reported even higher levels of sleep disturbance and that the data presented in this paper may be conservative estimates of the trajectories of self-reported sleep disturbance. Information on the use of sedatives and hypnotics is not available. However, based on the PSQI and GSDS medication subscale scores, very few patients reported the use of sleep medications.

Despite these limitations, findings from this longitudinal study suggest that younger men with co-occurring depression and anxiety may be at greatest risk for sleep disturbance during RT. Additional research is warranted on the impact of RT treatment and its associated symptoms (e.g., urinary frequency, urgency) on the trajectories of sleep disturbance and to determine the optimal interventions for these high-risk patients.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Nursing Research (NR04835). Dr. Aouizerat is funded through the National Institutes of Health Roadmap for Medical Research Grant (KL2 RR624130). Dr. Dunn received funding from the Mount Zion Health Fund and the UCSF Academic Senate. Dr. Miaskowski received funding from the American Cancer Society as a Clinical Research Professor. The assistance of the research nurses on the project, Carol Maroten, Mary Cullen, and Ludene Wong-Teranishi, and the support from the physicians and nurses at the study sites were greatly appreciated.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee K, Cho M, Miaskowski C, Dodd M. Impaired sleep and rhythms in persons with cancer. Sleep Med Rev. 2004;8:199–212. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Savard J, Morin CM. Insomnia in the context of cancer: a review of a neglected problem. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:895–908. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.3.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waldmann A, Rohde V, Bremner K, Krahn M, Kuechler T, Katalinic A. Measuring prostate-specific quality of life in prostate cancer patients scheduled for radiotherapy or radical prostatectomy and reference men in Germany and Canada using the Patient Oriented Prostate Utility Scale-Psychometric (PORPUS-P) BMC Cancer. 2009;9:295. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lev EL, Eller LS, Gejerman G, et al. Quality of life of men treated for localized prostate cancer: outcomes at 6 and 12 months. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:509–17. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0493-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engstrom CA. Hot flashes in prostate cancer: state of the science. Am J Mens Health. 2008;2:122–32. doi: 10.1177/1557988306298802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanisch LJ, Palmer SC, Marcus SC, Hantsoo L, Vaughn DJ, Coyne JC. Comparison of objective and patient-reported hot flash measures in men with prostate cancer. J Support Oncol. 2009;7:131–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freedland SJ, Eastham J, Shore N. Androgen deprivation therapy and estrogen deficiency induced adverse effects in the treatment of prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2009;12:333–8. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2009.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Savard J, Simard S, Hervouet S, Ivers H, Lacombe L, Fradet Y. Insomnia in men treated with radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2005;14:147–56. doi: 10.1002/pon.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dirksen SR, Epstein DR, Hoyt MA. Insomnia, depression, and distress among outpatients with prostate cancer. Appl Nurs Res. 2009;22:154–8. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raudenbush S, Bryk A. Hierarchical linear models: applications and data analysis methods. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raudenbush S, Bryk A, Cheong YF, Congdon R. HLM6: hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aouizerat BE, Dodd M, Lee K, et al. Preliminary evidence of a genetic association between tumor necrosis factor alpha and the severity of sleep disturbance and morning fatigue. Biol Res Nurs. 2009;11:27–41. doi: 10.1177/1099800409333871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim E, Jahan T, Aouizerat BE, et al. Changes in symptom clusters in patients undergoing radiation therapy. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:1383–91. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0595-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miaskowski C, Paul SM, Cooper BA, et al. Trajectories of fatigue in men with prostate cancer before, during, and after radiation therapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:632–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karnofsky D. Performance scale. New York: Plenum Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karnofsky D, Abelmann WH, Craver LV, Burchenal JH. The use of nitrogen mustards in the palliative treatment of carcinoma. Cancer. 1948;1:634–56. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee KA. Self-reported sleep disturbances in employed women. Sleep. 1992;15:493–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/15.6.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Measure. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spielberger CG, Gorsuch RL, Suchene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the State-Anxiety (Form Y): Self Evaluation Questionnaire. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jensen MP. The validity and reliability of pain measures in adults with cancer. J Pain. 2003;4:2–21. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2003.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee KA, Hicks G, Nino-Murcia G. Validity and reliability of a scale to assess fatigue. Psychiatry Res. 1991;36:291–8. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(91)90027-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carpenter JS, Andrykowski MA. Psychometric evaluation of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. J Psychosom Res. 1998;45(1 Spec No):5–13. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(97)00298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beck SL, Schwartz AL, Towsley G, Dudley W, Barsevick A. Psychometric evaluation of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;27:140–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fletcher BS, Paul SM, Dodd MJ, et al. Prevalence, severity, and impact of symptoms on female family caregivers of patients at the initiation of radiation therapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:599–605. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee KA, DeJoseph JF. Sleep disturbances, vitality, and fatigue among a select group of employed childbearing women. Birth. 1992;19:208–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1992.tb00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miaskowski C, Lee KA. Pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbances in oncology outpatients receiving radiation therapy for bone metastasis: a pilot study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;17:320–32. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(99)00008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheehan TJ, Fifield J, Reisine S, Tennen H. The measurement structure of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale. J Pers Assess. 1995;64:507–21. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6403_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carpenter JS, Andrykowski MA, Wilson J, et al. Psychometrics for two short forms of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 1998;19:481–94. doi: 10.1080/016128498248917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bieling PJ, Antony MM, Swinson RP. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Trait version: structure and content re-examined. Behav Res Ther. 1998;36:777–88. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kennedy BL, Schwab JJ, Morris RL, Beldia G. Assessment of state and trait anxiety in subjects with anxiety and depressive disorders. Psychiatr Q. 2001;72:263–76. doi: 10.1023/a:1010305200087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee KA, Portillo CJ, Miramontes H. The fatigue experience for women with human immunodeficiency virus. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1999;28:193–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1999.tb01984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee KA, Lentz MJ, Taylor DL, Mitchell ES, Woods NF. Fatigue as a response to environmental demands in women's lives. Image J Nurs Sch. 1994;26:149–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1994.tb00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raudenbush SW. Comparing personal trajectories and drawing causal inferences from longitudinal data. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:501–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li LW. Longitudinal changes in the amount of informal care among publicly paid home care recipients. Gerontologist. 2005;45:465–73. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.4.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li LW. From caregiving to bereavement: trajectories of depressive symptoms among wife and daughter caregivers. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60:P190–8. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.4.p190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Humphreys J, Lee KA, Carrieri-Kohlman V, et al. Theory of symptom management. In: Smith MJ, Liehr PR, editors. Middle range theory for nursing. Second ed. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2008. pp. 145–58. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dodd M, Janson S, Facione N, et al. Advancing the science of symptom management. J Adv Nurs. 2001;33:668–76. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Larson P, Carrieri-Kohlman V, Dodd MJ, et al. A model for symptom management. Image (IN) 1994;26:272–6. [Google Scholar]

- 41.LeBlanc M, Merette C, Savard J, Ivers H, Baillargeon L, Morin CM. Incidence and risk factors of insomnia in a population-based sample. Sleep. 2009;32:1027–37. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.8.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neckelmann D, Mykletun A, Dahl AA. Chronic insomnia as a risk factor for developing anxiety and depression. Sleep. 2007;30:873–80. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.7.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stepanski EJ, Walker MS, Schwartzberg LS, Blakely LJ, Ong JC, Houts AC. The relation of trouble sleeping, depressed mood, pain, and fatigue in patients with cancer. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5:132–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palesh OG, Roscoe JA, Mustian KM, et al. Prevalence, demographics, and psychological associations of sleep disruption in patients with cancer: University of Rochester Cancer Center-Community Clinical Oncology Program. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:292–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.5011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Das-Munshi J, Goldberg D, Bebbington PE, et al. Public health significance of mixed anxiety and depression: beyond current classification. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:171–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.036707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ancoli-Israel S. Sleep and its disorders in aging populations. Sleep Med. 2009;10(Suppl 1):S7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bloom HG, Ahmed I, Alessi CA, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for the assessment and management of sleep disorders in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:761–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02220.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vitiello MV, Moe KE, Prinz PN. Sleep complaints cosegregate with illness in older adults: clinical research informed by and informing epidemiological studies of sleep. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:555–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00435-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]