Abstract

Study Objectives:

To assess hypnotic self-administration and likelihood of dose escalation over 12 months of nightly use of zolpidem versus placebo in primary insomniacs.

Design:

Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trial.

Setting:

Outpatient with tri-monthly one-week, sleep laboratory assessments.

Participants:

Thirty-three primary insomniacs, without psychiatric disorders or drug and alcohol abuse, 32–64 yrs old, 14 men and 19 women.

Interventions:

Participants were randomized to take zolpidem 10 mg (n = 17) or placebo (n = 16) nightly for 12 months. In probes during month 1, 4, and 12, after sampling color-coded placebo or zolpidem capsules on 2 nights, color-coded zolpidem or placebo was chosen on 5 consecutive nights and 1, 2, or 3 of the chosen capsules (5 mg each) could be self-administered on a given choice night.

Results:

Zolpidem was chosen more nights than placebo (80% of nights) and number of nights zolpidem was chosen did not differ over the 12 months. More zolpidem than placebo capsules were self-administered, and the total number of placebo or zolpidem capsules self-administered did not differ as a function of duration of use. In contrast, the total number of placebo capsules self-administered by the placebo group increased across time. The nightly capsule self-administration on zolpidem nights did not differ from that on placebo nights and neither nightly self-administration rates increased over the 12 months. An average 9.3 mg nightly dose was self-administered.

Conclusions:

Zolpidem was preferred to placebo, but its self-administration did not increase with 12 months of use. Chronic hypnotic use by primary insomniacs does not lead to dose escalation.

Clinical Trial Registration:

Safety and Efficacy of Chronic Hypnotic Use; # NCT01006525; http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/

Citation:

Roehrs TA; Randall S; Harris E; Maan R; Roth T. Twelve months of nightly zolpidem does not lead to dose escalation: a prospective placebo-controlled study. SLEEP 2011;34(2):207–212.

Keywords: Primary insomnia, zolpidem, self-administration, chronic nightly use

CONCERNS REMAIN THAT BEHAVIORAL AND/OR PHYSICAL DEPENDENCE DEVELOPS WITH THE CHRONIC USE OF BENZODIAZEPINE RECEPTOR AGONIST hypnotics (BzRAs), the acknowledged drugs of choice in treating chronic insomnia. The concerns arise due to continued reports of behavioral and physical dependence associated with long-term anxiolytic or hypnotic use of therapeutic doses of BzRAs1–3. Among the risk factors identified for BzRA dependence is duration of use, and as might be expected longer use is thought to be associated with greater risk.4 Systematic and prospective information regarding the dependence liability of long-term use of BzRA hypnotics at clinical doses is limited. In population-based studies the majority of persons with insomnia report using hypnotics for two weeks or less, although a small percentage use hypnotics for one year and more.5,6 Importantly, this small percentage accounts for the majority of hypnotic use. Two recent prospective placebo-controlled studies of eszopiclone at clinical doses reported no evidence of physical or behavioral dependence after 6 months of nightly use.7,8 However, neither of these studies directly tested for physical or behavioral dependence.

In short-term studies we have directly tested the behavioral dependence liability of BzRA hypnotics using self-administration methods in which choice of active drug vs placebo, prepared as color-coded capsules, is offered nightly after a sampling night of each of the color-coded capsules. Active drug is chosen over placebo by insomniacs, and the severity of their sleep disturbance is predictive of their hypnotic self-administration rates.9 In these short-term studies, hypnotic self-administration was not associated with dose-escalation over 2 weeks of nightly use,10 did not increase with rebound insomnia,11 and did not generalize to daytime use.12 These short-term study results suggest the hypnotic self-administration of primary insomniacs is therapy seeking behavior and not drug seeking or dependence.

The present, prospective study of primary insomniacs assessed hypnotic self-administration and likelihood of dose escalation over 12 months of nightly use of zolpidem versus placebo. Self-administration and likelihood of dose escalation was assessed in months 1, 4, and 12 of this double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Drug efficacy was assessed in month 8 and will be reported in a separate paper.

METHODS

Participants

Persons 21–70 y old with difficulty falling asleep and/or staying asleep were recruited. Thirty-three men and women between the ages of 32–64 y, meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM IV-TR) criteria for primary insomnia completed the study (see Table 1 for completed participant demographics). A total of 8 participants discontinued the study after signing the consent and receiving ≥ 1 night of medication: 2 from the placebo group and 3 from the zolpidem group (see Table 2) and additionally, 3 participants signed the consent, qualified, and never reported to the sleep laboratory for the first study night. The major reason for discontinuation was non-compliance. All participants were in good physical and psychiatric health based on thorough medical, psychiatric, drug use history, and physical examination, as well as screening blood and urine laboratory analyses which are described below. The Institutional Review Board of the Henry Ford Health System approved the study protocol. All participants provided informed consent and were paid for their participation.

Table 1.

Demographics and drug use history of study groups

| Placebo | Zolpidem | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 16 | 17 |

| Average Age (range) | 50.13 (30–67) | 49.53 (32–64) |

| Gender | Males: 5 Females: 11 |

Males: 9 Females: 8 |

| Insomnia Measures | ||

| Reported Sleep Time (h) | 5.70 ± 1.77 | 5.13 ± 1.07 |

| mean ± SD; median | 5.38 | 5.00 |

| NPSG Sleep Time (h) | 6.00 ± 0.72 | 5.91 ± 0.63 |

| mean ± SD; median | 6.08 | 6.09 |

| SL NPSG (min) ± SD | 51.37 ± 40.46 | 31.67 ± 22.98 |

| (median; range) | (44.25; 6–154.5) | (19.5; 8–93.5) |

| WASO NPSG (min) ± SD | 86.20 ± 29.85 | 92.38 ± 47.28 |

| (median; range) | (82; 57.5–175) | (94; 24.5–162) |

| Age of insomnia onset | 41.40 | 33.75 |

| (median; range) | (45; 18.5–65) | (37; 7–57) |

| Duration of insomnia | 8.72 | 15.56 |

| (median; range) | (5.5; 1–27) | (9.0; 1–54) |

| Self Reported Alcohol and Drug Consumption | ||

| Alcohol (drinks/week: N) | 0–1: 8 | 0–1: 8 |

| 2–6: 1 | 2–6: 0 | |

| 7–14: 7 | 7–14: 9 | |

| Caffeinated Products (drinks/week: N) | 0–1: 5 | 0–1: 7 |

| 2–6: 2 | 2–6: 5 | |

| 7–14: 4 | 7–14: 3 | |

| 15 or more: 5 | 15 or more: 2 | |

| Previous Illicit Drug History | No drug history: 13 | No drug history: 15 |

| Marijuana use ≥ 2 y ago: 2 | Marijuana use ≥ 2 y ago: 2 | |

| Cocaine use ≥ 20 y ago: 1 | Cocaine use: 0 | |

| Current Nicotine Usage | ≤ 10/day: 4 | ≤ 10/day: 4 |

| Non smokers: 12 | Non smokers: 13 | |

NPSG refers yo nocturnal polysomnogram; SL, sleep latency; WASO, wake after sleep onset.

Table 2.

Participants discontinuing after consent and one night of medication

| Placebo | |

|---|---|

| Number withdrawn = 2 | Reason |

| Month 3 | Disputes the amount of taxes taken out of compensation |

| Month 3 | Noncompliance |

|

Zolpidem | |

| Number withdrawn = 3 | Reason |

| Month 4 | Noncompliance |

| Month 6 | Job moved out of state |

| Month 1 Nt13 | Physician prescribed an antidepressant |

Noncompliance: No show for lab visit and/or non responsive to communications.

Experimental Design

The study was conducted as a mixed design, double-blind, placebo-controlled, experiment with a between-group comparison in which primary insomniacs were randomly assigned to use zolpidem 10 mg (5 mg for those > 60 y) or placebo nightly for 12 months. During the 12 months, participants returned to the sleep laboratory for one week long zolpidem vs placebo self administration assessments in months 1, 4, and 12, which constituted the within subjects comparison.

Procedures

General health and psychiatric screening

Respondents to advertisements for persons “with difficulty falling asleep and/or staying asleep” were interviewed by telephone regarding their insomnia, general health, past psychiatric, alcoholism, and drug abuse histories. Those passing the telephone screen were scheduled for a clinic visit during which they gave informed consent, provided a medical and drug-taking history, including prescribed medications, legal and/or illegal recreational drugs, underwent a physical examination, and provided blood and urine samples. Those with any acute or unstable illness including conditions making it unsafe for the person to participate, conditions with a potential to disturb sleep (i.e., acute pain, respiratory disorders), and conditions which could interact with the pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics (e.g., moderate to severe liver disease, heavy smoking) of zolpidem were excluded, as were those with chronic illnesses including renal failure, liver disease, seizures, and dementing illnesses. Participants with psychiatric disorders, anxiety, depression, and schizophrenia disorders, as identified by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR (SCID) were also excluded.

The screening blood and urine laboratory panel for general health also included testing for medications and illegal drugs including but not limited to opiates, benzodiazepines and stimulants. Participants with a history of substance (drug or alcohol) use disorders or current use of central nervous system acting medications at screening were excluded. Participants reporting any use of illegal drugs within the past 2 years also were excluded. Participants who reported consuming > 14 standard (1 oz) alcoholic drinks per week, caffeine consumption > 300 mg/day, and smoking during the night (23:00–07:00) were excluded (see Table 1 for drug use histories).

Sleep disorders screen

Each participant underwent a sleep-wake history, sleep disorders evaluation, and nocturnal polysomnogram (NPSG). Each qualified for a DSM-IVR diagnosis of primary insomnia. As part of the sleep-wake history, participants completed a 2-week sleep diary, which was used to determine their habitual bedtime and the screening NPSG bedtime. For the screening NPSG bedtime, the midpoint of their bedtime reported on the 2-week sleep diary was determined, and 4 h were added to each side of the diary-reported bedtime midpoint to create an 8 h bedtime without disrupting circadian rhythms.

After the screening physical and laboratory tests, the participants underwent the screening 8-h NPSG. In addition to the clinical DSM-IVR primary insomnia diagnosis, all participants were also required to show sleep efficiencies of ≤ 85% (total sleep time/time in bed) and no other primary sleep disorders. Participants with respiratory disturbances (apnea hypopnea index [AHI] > 10) or leg movements (periodic limb movement arousal index [PLMAI > 5]) were excluded from the study.

The standard Rechtschaffen and Kales methods for the electrophysiological recording of sleep were used.13 The recordings obtained from each participant included standard central (C3-A2) and occipital (Oz-A2) electroencephalograms (EEGs), bilateral horizontal electrooculograms (EOG), submental electromyogram (EMG), and electrocardiogram (ECG) recorded with a V5 lead. In addition, on the screening night airflow was monitored with oral and nasal thermistors, and leg movements were monitored with electrodes placed over the left tibialis muscles; respiration and tibialis EMG recordings were scored for apnea and leg movement events and event frequencies were tabulated.14,15 Those with ≥ 10 sleep disordered breathing events or ≥ 10 periodic leg movements with EEG arousals per hour of sleep were excluded. After the screening night, all subsequent recordings excluded the airflow and leg monitoring. All recordings were scored in 30-sec epochs for sleep stages according to the standards of Rechtschaffen and Kales.13 Scorers maintained 90% inter-rater reliability.

Medication preparation

Zolpidem 10 mg, or 5 mg for participants > 60 years old, and placebo was prepared by the HFHS Research Pharmacy in size # 1 capsules with lactose. Participants were instructed to take their designated medication nightly 30 min before bedtime. Capsules were dispensed at monthly clinic visits.

Weekly telephone monitoring

Using an automated voice interactive telephone system participants were instructed to call an 800 telephone number each week on a set day. Failure to call on the set day was followed with a staff-initiated call. These weekly calls initiated a 10-item questionnaire regarding the participant's sleep the past week, which included a report of the number of capsules taken the past week. These reports were confirmed with capsules counts taken at the monthly clinic visits.

Self-administration assessments

For the self-administration assessments of months 1, 4, and 12, each participant spent 3 consecutive nights in the sleep laboratory, the next 3 nights at home and a final night in the laboratory (a total of 7 nights). Nights 1 and 2 were sampling nights during which participants received, on 1 night each, either their assigned medication (i.e., zolpidem at the age-appropriate dose) or placebo and placebo on both nights if assigned to the placebo group. Placebo and zolpidem were color coded. On the sampling nights the order of placebo and zolpidem presentation was counter-balanced as were the colors assigned to placebo and zolpidem. The following 5 nights the participants were asked to choose a capsule color, based on their sampling night experiences (i.e., “I want the blue or red medication”). For the placebo group the choice was between 2 placebos in different colored capsules. Participants were then given the option of taking I, 2, or 3 capsules of their chosen capsule color. For the zolpidem group the capsules were either three 5 mg zolpidem capsules, for a total possible dose of 15 mg on any given night, or 3 placebo capsules. To standardize drug administration and choice procedures, participants received forms on which they were instructed about the sampling medications they were receiving and then choice forms on which they specified the color chosen and the number of chosen capsules they desired on a given night.

The dependent measures for the self administration assessment were the number of active drug choices made for the 5 nights and the average number of capsules (i.e., nightly dose) chosen over the 5 nights. The study was designed to detect effect sizes of 0.60 and greater with a 0.80 power. Given the results of our short-term studies,9–12 we were prepared to detect a 0.50 capsule increase in average nightly dose (i.e., 5 to 7.5 mg or 10 to 12.5 mg, given each capsule was 5 mg) with n = 15–20 per group.

Data Analyses

The weekly self-reports of the number of capsules taken while at home were compiled for each month and expressed as percentages per month. These compliance data were compared between groups with a χ2. For each of the month 1, 4, and 12 self-administration assessments, 3 primary outcome variables were used: (1) the number of zolpidem or placebo choices made (i.e., number of choice nights with a total of 5 possible), (2) the total number of zolpidem or placebo capsules chosen, and (3) given a placebo or zolpidem choice on a given night, the nightly number of capsules taken. The total number of zolpidem vs placebo choices made by the zolpidem group over the 12 months was compared with a χ2. The number of capsules chosen, placebo or zolpidem, was totaled for each of the 3 assessments at month 1, 4, and 12. Mixed design analyses (MANOVAs) were used to compare groups for the total number of placebo capsules chosen with months as a repeated variable. Within the zolpidem group the number of placebo versus zolpidem capsules chosen was compared with MANOVAs, with drug and months as repeated measures variables. The number of placebo capsules chosen by the placebo group was compared to the number of zolpidem capsules chosen by the zolpidem group during the 3 assessments using mixed design MANOVAs, with the 3 assessments as a repeated variable and drug groups as the between-subject variable.

In analyses by nights within each of the 3-month assessments, a nightly number of capsules self-administered was calculated for those nights on which placebo or zolpidem was chosen. The nightly rates of placebo self-administration were compared between groups and the nightly rates of placebo versus zolpidem within the zolpidem group were compared with t-tests done separately for each of the 3 assessments. The absence of sufficient placebo choices within the zolpidem group limited the ability to use months as a repeated variable in a MANOVA. Lastly, since some choice nights occurred in the laboratory (nights 1 and 5) and some at home (nights 2–4), the mean number of zolpidem capsules self-administered on laboratory versus home nights was compared with MANOVAs with months and lab-home as repeated measures.

RESULTS

The demographics, insomnia history, and drug use history of the 2 study groups are presented in Table 1. The groups did not differ in age, but there were more men in the zolpidem group than the placebo group. The groups did not differ in self-reported or NPSG-defined sleep times or the age of onset and duration of their insomnia complaints. They complained, and showed on NPSG, both sleep onset and maintenance problems. These chronic insomniacs had a wide range in age of onset and duration of insomnia. Their self-reported sleep times were consistent with their laboratory screening NPSG-defined sleep times. The groups had similar drug use histories.

Table 3 presents the monthly medication compliance data for the 2 study groups. On weekly telephone interviews, done during non-laboratory weeks, participants reported taking between 73% and 89% of the single nightly capsules each month while at home. The percentages of capsules taken did not vary systematically over the 12 study months, and the groups did not differ in the average percentage of capsules used over the 12 months (placebo: 81% ± 0.04% vs zolpidem: 84% ± 0.03%).

Table 3.

Treatment compliance of study groups by month

| Month |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

| Placebo | 76 | 85 | 82 | 78 | 85 | 73 | 79 | 81 | 82 | 82 | 87 | 85 |

| Zolpidem | 81 | 83 | 88 | 85 | 82 | 77 | 87 | 80 | 84 | 89 | 82 | 83 |

| Total | 79 | 84 | 85 | 82 | 83 | 75 | 84 | 80 | 84 | 86 | 84 | 84 |

Percentage of nights the study medication was taken while sleeping at home as compiled by month from the weekly phone interviews.

Over the 3 one-week laboratory self-administration assessments (months 1, 4, and 12), the zopidem group selected zolpidem (80.3%) more often than placebo (χ2 = 5.37, P < 0.020). The placebo group showed no color preference (i.e., both color-coded capsules were placebo), choosing the red capsule 51% of opportunities and blue 49%. The mean number of nights (out of 5) zolpidem was chosen across months (month 1: 4.4 ± 1.2, month 4: 3.8+1.7, and month 12: 4.2+0.7) did not differ. The number of insomniacs showing a preference for zolpidem, defined as choosing zolpidem on ≥ 3 of the 5 nights, was 16 of 17 in month 1, 13 of 17 in month 4, and 17 of 17 in month 12 (χ2 = 5.77, P = 0.056)

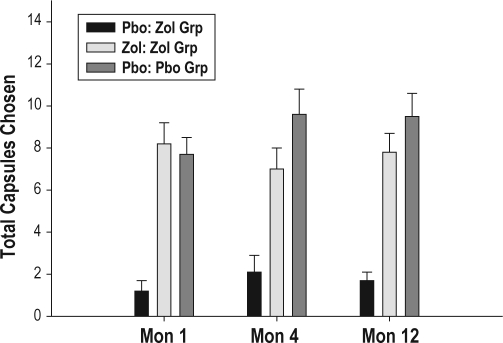

The mean total number of zolpidem and placebo capsules chosen by the zolpidem and placebo groups in month 1, 4, and 12 is presented in Figure 1. Overall, the zolpidem group self-administered more zolpidem capsules than placebo capsules (F = 46.56, P < 0.001). In the zolpidem group, the total number of capsules chosen, whether placebo or zolpidem, did not differ over months 1, 4, and 12. The placebo group was choosing between placebo capsules each night, regardless of capsule color, and the total number of placebo capsules self-administered by the placebo group did increase significantly during both months 4 and 12 from that of month 1 (F = 4.38, P < 0.02).

Figure 1.

Total number of placebo and zolpidem (5 mg) capsules chosen by the Zolpidem group and the total number of placebo capsules chosen by the Placebo group during the 5 choice nights of each month. A total of 15 capsules, 3 per night, was available at each month's assessment. Number of zolpidem capsules chosen by the zolpidem group differed from the number of placebo capsules (F = 46.56, P < 0.001). The number of placebo capsules chosen by the placebo group increased in month 4 and 12 from that of month 1 (F = 4.37. P < 0.02), while number of both placebo and zolpidem capsules chosen by the zolpidem group did not differ over months.

As noted above, over the 1, 4, and 12 month assessments the zolpidem group chose zolpidem an average of 4.1 ± 1.2 of the 5 nights. Thus, the monthly totals of Figure 1 do not reflect the nightly number of capsules self-administrated by the zolpidem group. Table 4 presents the nightly number of placebo and zolpidem capsules self-administered in the 3 assessments and the number of participants making a given choice on ≥ 1 of the 5 choice nights. Thus, for example in month 4 for the zolpidem group (“n” choices = 16) one of the zolpidem participants never choose zolpidem. Within the zolpidem group the nightly number of placebo versus zolpidem capsules self-administered each month did not differ, and both did not differ across the 3 assessments, which is in contrast to placebo group in which the nightly number increased (F = 4.38, P < 0.02) over months. On average the zolpidem group self-administered a 9.1 mg dose nightly in month 1, a 9.4 mg dose in month 4, and a 9.4 mg dose in month 12 (i.e., each zolpidem capsule was 5 mg).

Table 4.

Nightly zolpidem and placebo self-administration

| Month 1 | Month 4 | Month 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zolpidem Group | |||

| Zolpidem Capsules | 1.83 ± 0.78 | 1.88 ± 0.74 | 1.88 ± 0.78 |

| “n” choices | 17 | 16 | 17 |

| Placebo Capsules | 2.16 ± 2.13 | 1.71 ± 0.95 | 2.05 ± 0.78 |

| “n” choices | 6 | 7 | 11 |

| Placebo Group | |||

| Placebo Capsules | 1.54 ± 0.66 | 1.91 ± 0.93 | 1.90 ± 0.87 |

| “n” choices | 16 | 16 | 16 |

Data are the mean ± SD number of zolpidem or placebo capsules taken each night. “n” choices = number of participants choosing zolpidem or placebo on ≥ 1 of the 5 choice nights.

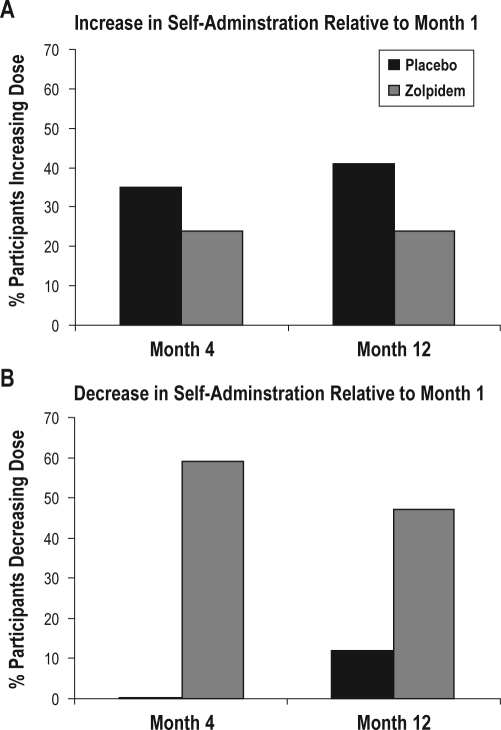

The percent of participants in the zolpidem and placebo groups that increased or decreased, relative to month 1, the number of capsules (i.e., dose) that they self-administered in month 4 and 12 is presented in Figure 2. The percent of participants increasing dose did not differ between the zolpidem and placebo groups and did not change from month 4 to month 12. A significantly greater percent of zolpidem compared to placebo participants decreased the dose they self-administered in month 4 and month 12 relative to month 1 (χ2 = 11.22, P < 0.001).

Figure 2.

The percent of participants in the placebo and zolpidem groups that increased (Panel A) or decreased (Panel B) relative to month 1 the number of capsules (i.e., dose) that they self-administered in month 4 and 12. Percents increasing and decreasing within a group do add to 100% as a percent within each group did not change. A greater percentage of zolpidem versus placebo participants decreased dose in month 4 and 12 (χ2 = 11.22, P < 0.001).

Finally, during each of the 3 assessments the 2 sampling nights, the first choice night, and the fifth choice night were spent at the sleep laboratory, and the 3 middle choice nights were spent at home. Table 5 presents the zolpidem self-administration of the zolpidem group when sleeping in the laboratory versus sleeping at home for each of the 3 assessments. The self-administration rates did not differ when at the laboratory versus at home. These rates also did not differ over the 3 assessments.

Table 5.

Laboratory versus home zolpidem self-administration

| Month 1 | Month 4 | Month 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zolpidem Group | |||

| Lab # Capsules (choice nts 1 + 5) | 1.56 ± 0.96 | 1.41 ± 0.76 | 1.62 ± 0.80 |

| Home # Capsules (choice nts 2 – 4) | 1.69 ± 0.87 | 1.39 ± 0.88 | 1.52 ± 0.90 |

Data are mean ± SD number of zolpidem capsules

DISCUSSION

This is the first prospective study to directly assess the behavioral abuse liability of chronic use of a BzRA hypnotic. The findings from this study demonstrate primary insomniacs prefer zolpidem relative to placebo and the preference does not change over 12 months of nightly zolpidem use. When given an opportunity to choose the number of capsules taken nightly, the nightly self-administered dose of the zolpidem group was comparable to that of the placebo group, but importantly, did not differ over the 12 months. In contrast, the nightly dose of the placebo group increased over the 12 months.

In this first study of its kind, a laboratory based prospective abuse liability assessment of chronic hypnotic use, we chose to study only primary insomniacs for a number of critical and important reasons, which admittedly limits the generalizability of our study results. We chose to study a homogeneous sample without comorbid conditions, given the sample size limitations of a laboratory study, the 2 types of assessment (i.e., physical and behavioral dependence) being conducted, and the potential loss of participants over the 12 study months. We also considered it important to extend our short term studies which were conducted in primary insomniacs. Finally and most importantly, for ethical reasons we could not expose participants with possible risk factors for dependence (see discussion below) to long-term hypnotic use.

We chose to add the additional NPSG criteria of a sleep efficiency ≤ 85% to the DSM-IV-TR primary insomnia criteria for several reasons. First, we wanted to assure that we were studying moderate to severe insomniacs. Also, based on our previous short-term studies, we had found that insomniacs with sleep efficiencies > 85% had a reduced rate of self-administering hypnotics.11 Finally, it is more likely that the moderate to severe insomniac will seek and receive treatment.

These long-term data are consistent with the short-term data previously collected in primary insomniacs. There is a strong preference for active medication, but no dose escalation.9–12 The short-term studies were conducted using triazolam 0.25 mg. We choose to study zolpidem 10 mg in this long-term study as it was the most frequently prescribed hypnotic at the time of the study design. Furthermore, while initially considered safer than the older benzodiazepine hypnotics (i.e., triazolam), case reports regarding zolpidem dependence were appearing in the literature.

Given the reports of hypnotic dependence in clinical populations, the question arises as to whether risk factors can be identified. In a multivariate analysis of 599 patients from general practices (36%), outpatient psychiatric clinics (58%), and self-help groups for patients concerned with addiction (6%), the most important predictors for dependence were dose and duration of use.4 The duration of use in these patient sub-samples ranged from 18–90 months with a mean of 30 months, and the dose ranged from 5–30 mg in diazepam equivalents with a mean of 10 mg. The present study was a 12-month study, shorter than even the shortest duration of use among the patient sub-samples. The mean dose in diazepam equivalents (10 mg) is not that different than the 10 mg zolpidem dose of the present study. However, the highest dose 30 mg was found in the addiction patients.

Among the secondary predictors of dependence risk in the multivariate study was the presence of anxiety and/or depression. This may be an important difference from the present study. In the present study participants were recruited from the general population and carefully screened for psychiatric disorders. Approximately 50% of our study respondents were screened out for psychiatric disorders. Our participants were primary insomniacs without any comorbid disorders. Our participants were also screened for a history of alcoholism and drug abuse. We did allow participants who reported past (> 2 year) occasional illicit drug use (see Table 1). We also screened participants for heavy current alcohol use (see Table 1).

Of interest, the self-administration behavior of the placebo group in the present study is a close replication of our previous short-term study.10 In that study, the number of placebo capsules self-administered increased over the 5 choice night assessment. In the present study, the number of placebo capsules self-administered did not increase within the 5 choice nights, but it did increase across the months of use. We have interpreted this behavior as therapy seeking behavior. That is when given an ineffective hypnotic (placebo) primary insomniacs will increase the dose to obtain relief for their insomnia. In the earlier study, patient self-reports of their self-administration behavior supported this interpretation. Loss of efficacy, or lack of initial efficacy, may be an important clinical predictor of abuse liability for a given patient.

In summary primary insomniacs had a clear preference for zolpidem compared to placebo but do not increase the dose of zolpidem over 12 months of nightly use. The “dose” of placebo was increased in the placebo group over the 12 months.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. Dr. Roehrs has consulted for Evotec and Sanofi-Aventis and has received research support from Takeda. Dr. Roth has served as a consultant for Abbott, Accadia, Acogolix, Acorda, Actelion, Addrenex, Alchemers, Alza, Ancel, Arena, AstraZeneca, Aventis, AVER, Bayer, BMS, BTG, Cephalon, Cypress, Dove, Eisai, Elan, Eli Lilly, Evotec, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Hypnion, Impax, Intec, Intra-Cellular, Jazz, Johnson and Johnson, King, Lundbeck, McNeil, MediciNova, Merck, Neurim, Neurocrine, Neurogen, Novartis, Orexo, Organon, Otsuka, Prestwick, Proctor and Gamble, Pfizer, Purdue, Resteva, Roche, Sanofi, Schoering-Plough, Sepracor, Servier, Shire, Somaxon, Syrex, Takeda, TransOral, Vanda, Vivometrics, Wyeth, Yamanuchi, and Xenoport; has participated in speaking engagements for Cephalon, Sanofi, and Sepracor; and has received research support from Aventis, Cephalon, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Neurocrine, Pfizer, Sanofi, Schoering-Plough, Sepracor, Somaxon, Syrex, Takeda, TransOral, Wyeth, and Xenoport. The other authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

NIDA grant #R01DA17355 awarded to Timothy A. Roehrs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Woods JH, Winger G. Current benzodiazepine issues. Psychopharmacology. 1995;118:107–15. doi: 10.1007/BF02245824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fach M, Bischof G, Schmidt C, Rumpf HJ. Prevalence of dependence on prescription drugs and associated mental disorders in a representative sample of general hospital patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:257–63. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Victorri-Vigneau C, Dailly E, Veyrac G, Joillet P. Evidence of zolpidem abuse and dependence: results of the French Centre for Evaluation and Information on Pharmacodependence (CEIP) network survey. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;64:198–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02861.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kan CC, Hilbedrink SR, Breteier MHM. Determination of the main risk factors for benzodiazepine dependence using a multivariate and multidimensional approach. Comp Psychiatry. 2004;45:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mellinger GD, Balter MB, Uhlenhuth EH. Insomnia and its treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42:225–32. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790260019002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roehrs T, Hollebeek E, Drake C, et al. Substance use for insomnia in Metropolitan Detroit. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:571–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00448-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krystal AD, Walsh JK, Laska E, et al. Sustained efficacy of eszopiclone over 6 months of nightly treatment: Results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in adults with chronic insomnia. Sleep. 2003;26:793–9. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.7.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walsh J, Krystal A, Amato DA, et al. Nightly treatment of primary insomnia with eszopiclone for six months: Effect on sleep, quality of life, and work limitations. Sleep. 2007;30:959–68. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.8.959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roehrs T, Bonahoom A, Pedrosi B, Rosenthal L, Roth T. Disturbed sleep predicts hypnotic self administration. Sleep Med. 2002;3:61–6. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(01)00125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roehrs T, Pedrosi B, Rosenthal L, Roth T. Hypnotic self administration and dose escalation. Psychopharmacology. 1996;127:150–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02805988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roehrs T, Merlotti L, Zorick F, Roth T. Rebound insomnia and hypnotic self administration. Psychopharmacology. 1992;107:480–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02245259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roehrs T, Bonahoom A, Pedrosi B, Roth T. Nighttime versus daytime hypnotic self-administration. Psychopharmacology. 2002;161:137–42. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rechtschaffen A, Kales A. A manual of standardized terminology, techniques, and scoring system for sleep stages of human subjects. Washington D.C.: Public Health Service, U.S. Government Printing Office; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coleman RM. Periodic movements I sleep (nocturnal myoclonus) and restless legs syndrome. In: Guilleminault C, editor. Sleeping and waking disorders: indications and techniques. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co; 1982. pp. 265–295. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bornstein SK. Respiratory monitoring during sleep: polysomnography. In: Guilleminault C, editor. Sleeping and waking disorders: indications and techniques. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co; 1982. pp. 183–212. [Google Scholar]