Abstract

Background

Women with breast cancer are more likely to have a second breast cancer than the general population. However, the biological relationship between primary and second breast cancers is not clear.

Methods

30,617 patients diagnosed with bilateral breast cancers between 1990 and 2007 were identified through 17 cancer registries of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program. Logistic regression with odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) was used to model strength of association in hormone receptor status, grade, and histology between two cancers.

Results

There was a strong association in estrogen receptor (ER) status between two bilateral tumors, with OR of 7.64 (95% CI: 7.00–8.35). The strength of association in ER status depended on the time interval between the first and second tumors and age at diagnosis. The OR was 25.9 for synchronous tumors (within 1 month) and 3.69 for metachronous cases separated by 10 years or longer. The strength of association was stronger for patients with first cancer diagnosed before age 50 (OR=11.7) than after age 50 (OR=5.71). Similar pattern was observed for progesterone receptor, grade, and histologic type but with relatively weaker association.

Conclusions

The strong concordance in hormone receptor status of the primary and second breast cancers suggests that two breast cancers arise in a common milieu and tumor subtypes are predetermined in the early stage of breast carcinogenesis.

Keywords: Breast Neoplasms, Estrogen Receptor, Second Primary Neoplasm, Tamoxifen, SEER program, Molecular Epidemiology

Women with breast cancer have more than a two-fold higher risk of developing a second breast cancer than the risk women in the general population have of developing a primary breast cancer.1, 2 However, the biological relationship between the two breast cancers is not well understood. It is unclear whether the second cancer represents an independent second primary tumor or a sequential event of a primary tumor. Even if the two cancers develop from different origins, they may not truly be independent because they are subjected to similar hormonal, environmental, and genetic influences. Therefore, understanding the relationship between the two tumors has implications in both cancer treatment and understanding of breast carcinogenesis.

Previous studies have evaluated the concordance in hormone receptor between primary and contralateral breast cancers occurring in the same patients.3–11 Many, but not all, studies found a positive association in the level (or status) of estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) between the first primary and contralateral breast cancers. However, the degree of association is yet to be defined. Several factors may affect this association, including time interval between two cancers and tamoxifen treatment. Coradini et al. reported that there was a positive correlation in levels of ER and PR between primary and contralateral breast cancers, and that the correlation for ER levels, but not PR levels, was higher in synchronous than in metachronous breast cancer.8 Gong et al. found that the concordance in PR status was higher in synchronous than in metachronous cancers.9 Swain et al. showed that ER status of primary breast cancer was predictive of ER status of contralateral breast cancer among patients who did not receive tamoxifen, but the association was not statistically significant in patients receiving tamoxifen.10 In contrast, Arpino et al. showed that the ER and PR status of the primary breast cancer did not predict hormone receptor status of contralateral breast cancer among patients treated with or without tamoxifen.6 These inconsistencies in previous studies are probably due to limited sample size, as the sample size ranged from several dozen to several hundred.

Using the large dataset from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registries, we conducted this study in order to give a more concrete answer on the relationship between hormone receptor status of the primary and second breast cancers. Specifically, the study aims to 1) assess the association in morphologic pathologic features (histologic type and tumor grade) and molecular markers (ER and PR) between the primary and second breast cancers; 2) examine the factors that modify these associations; and 3) compare the proportions of ER and PR positivity between the primary and second breast cancers.

METHODS

Since 1990, hormone receptor status has been reported to the National Cancer Institute’s SEER database. In order to have precise estimates of association and sufficient power for subgroup analysis, we utilized data from all 17 SEER cancer registries, which currently represent 26% of the US population.12 Using a unique identifier assigned to each patient, we identified 33,587 patients who had diagnoses of bilateral breast cancers between 1990 and 2007. The majority of these patients have had two diagnoses of breast cancers, 856 (2.5%) had three or more diagnoses of breast cancers. For simplicity of the analysis, we only included the first two diagnoses for patients with more than two diagnoses. In order to avoid the potential metastases to the contralateral breast in patients with stage IV disease, we excluded 3219 patients who had distant metastasis in either of the two cancers and 651 patients who had missing data in metastasis status. These left a total of 30,617 bilateral breast cancer patients in the analysis.

In the present study, four pathologic characteristics are compared between the first primary and second primary breast cancers. These include histologic type, tumor grade, estrogen receptor status, and progesterone receptor status. According to ICD-O-3 histology codes, histologic type was grouped into 9 categories: ductal (8500, 8523); lobular (8520, 8522, 8524); comedocarcinoma (8501); mucinous (8480, 8481); papillary (8503, 8504, 8260, 8050, 8051); tubular (8211); inflammatory (8530); medullary (8510, 8512, 8513, 8514); and others. We also further collapsed histologic type into ductal, lobular, and others. Tumor grade in SEER was categorized into three levels: I, well-differentiated; II, moderately differentiated; III, poor differentiated or undifferentiated. The ER and PR were recorded as positive versus negative.

We explore the following variables as potential factors that modify the concordance in pathologic markers: time interval between the first and second primary breast cancers (<1 month was considered as synchronous), age at first diagnosis of breast cancer, year at first diagnosis of breast cancer, stage of first breast cancer (SEER stage: in situ, localized, and regional), surgery for the first breast cancer (no, lumpectomy, mastectomy), radiation therapy for the first breast cancer, and race (White, Black, Asian, Native American).

Logistic regression with odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) was used to assess the strength of association in hormone receptor status between the two cancers. Here, an odds ratio of more than 1 indicates a positive association. Specifically, the binary ER status of the second cancer was the dependent variable, whereas ER status of the first cancer was the independent variable. To examine the factors that modify the associations, a main effect of a modifier (such as age group) and an interaction of the modifier and ER status of the first cancer were added in the model as independent variables. For synchronous cases, one cancer was randomly chosen as the first cancer. Because odds ratio is a symmetric metric for the strength of association, the order of the first and second cancers does not matter.

The strength of association in histologic type and tumor grade can also be measured using odds ratio, but there are multiple odds ratios because they are nominal or ordinal variables. Taking the 3-category histologic type as example, we can model ductal versus lobular and other types, lobular versus ductal and other types, and lobular and ductal versus other types in three separate binary logistic regressions, yielding three separate odds ratios. As a single, global, odds ratio quantifying the overall strength of an association, is desired, we used a generalized estimating equation (GEE) model with logit link to estimate the overall associations between histologic type and between tumor grade.13 This model essentially combined odds ratios from separate binary logistic regression models listed above. To calculate standard errors, we specified independence working correlation and used the robust (sandwich) variance estimator.

Conditional logistic regression was used to examine the change in proportion of hormone receptor positivity. Only metachronous cases were included in this analysis. We modeled the proportion of positive hormone receptor status as the function of time interval between the first primary and second breast cancer. Odds ratios and 95% CI were calculated from the model, with OR<1 indicating that the hormone receptor positive proportion decreases. Statistical analysis was conducted in Stata 11.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Of 30,617 patients who had bilateral breast cancers between 1990 and 2006, almost all were female (99.7%). The race distribution was 85.0% White, 8.0% Black, 6.6% Asian/Pacific Islander, and 0.3% Native American. The average age was 60.5 years old at first breast cancer diagnosis and 63.1 years old at second diagnosis. For 8,787 (28.7%) patients, the tumors presented synchronous (within 1 month). Among metachronous cases, the median time interval between two cancers was 31 months (interquartile range: 6–70 months). After the first breast cancer, 51.2% of patients underwent mastectomy, 47.5% underwent lumpectomy, and 41.4% received radiation therapy.

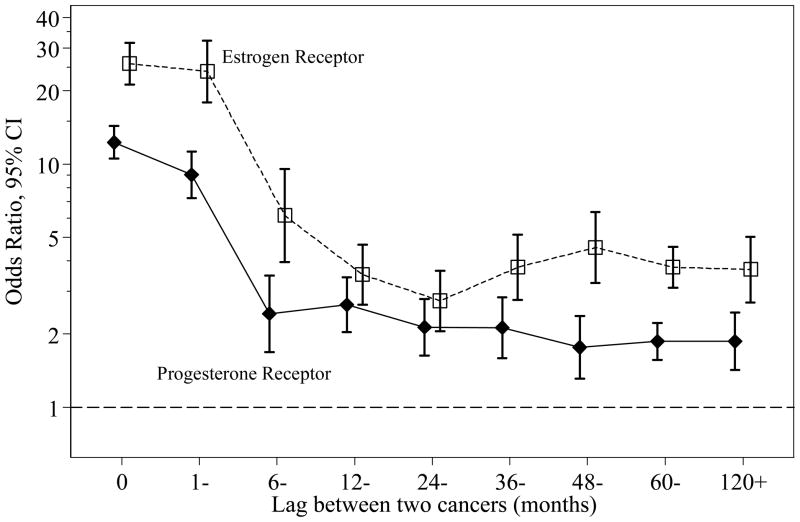

Table 1 cross-tabulates ER status of the first and second cancers, according to time interval between two cancers, and age and stage of the first cancer. There was a very strong association in ER status between two tumors, with OR of 7.64 (95% CI: 7.00–8.35) between the primary and contralateral breast cancer. This association is corresponding to 81% overall agreement: for patients with first cancer being ER positive, the chance that the second cancer is ER positive was 87.5%, compared with 47.8% for patients with first cancer being ER negative. The strength of association in ER status depended on the time interval between the first and second tumors (p<0.0001). As illustrated in Figure 1, the strength of association decreased as the time interval between two tumors increased: the OR was 25.9 for synchronous tumors and 3.69 for metachronous cancers separated by 10 years or longer. Interestingly, the strength of association in ER status between bilateral cancers did not vary after 12 months (p=0.34). The association in ER status also depended on age at diagnosis in patients with bilateral breast cancers (p<0.0001): the OR was 11.7 and 5.71 for patients with first breast cancer diagnosed before and after 50 years old, respectively. This modification effect by age at diagnosis remained significant after adjusting for time interval between two cancers (p<0.0001). We also examined whether year at first diagnosis, tumor stage, surgery, radiation therapy, and race modify the association in ER status and found none of them were significant effect modifiers after adjustment for the aforementioned two modifiers (age and lag time).

Table 1.

Association of estrogen receptor status in patients with two primary breast cancers, SEER 1990–2006

| ER of first cancer | ER of contralateral cancer |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative No. (%) | Positive No. (%) | OR (95% CI) | ||

| All patients | Negative | 1608 (52.2) | 1474 (47.8) | |

| Positive | 1589 (12.5) | 11133 (87.5) | 7.64 (7.00–8.35) | |

| Lag interval | ||||

| < 1 month | Negative | 420 (60.7) | 272 (39.3) | |

| Positive | 262 (5.6) | 4387 (94.4) | 25.9 (21.2–31.5) | |

| 1–5 months | Negative | 190 (56.9) | 144 (43.1) | |

| Positive | 105 (5.2) | 1913 (94.3) | 24.0 (17.9–32.2) | |

| 6–11 months | Negative | 63 (56.2) | 49 (43.8) | |

| Positive | 87 (17.3) | 416 (82.7) | 6.15 (3.96–9.54) | |

| 12–59 months | Negative | 512 (50.0) | 511 (50.0) | |

| Positive | 646 (22.1) | 2273 (77.9) | 3.53 (3.03–4.10) | |

| ≥ 60 months | Negative | 423 (45.9) | 498 (54.1) | |

| Positive | 489 (18.6) | 2144 (81.4) | 3.72 (3.17–4.38) | |

| P for interaction | <0.0001 | |||

| Age at first cancer | ||||

| < 50 years | Negative | 751 (66.9) | 372 (33.1) | |

| Positive | 350 (14.7) | 2030 (85.3) | 11.7 (9.90–13.9) | |

| ≥ 50 years | Negative | 857 (43.7) | 1102 (56.3) | |

| Positive | 1239 (12.0) | 9103 (88.0) | 5.71 (5.13–6.36) | |

| P for interaction | <0.0001 | |||

| Stage of first cancer | ||||

| In situ | Negative | 115 (48.9) | 120 (51.1) | |

| Positive | 106 (9.4) | 1016 (90.6) | 9.19 (6.64–12.7) | |

| Localized | Negative | 952 (51.3) | 905 (48.7) | |

| Positive | 1006 (12.3) | 7177 (87.7) | 7.50 (6.71–8.40) | |

| Regional | Negative | 541 (54.6) | 449 (45.4) | |

| Positive | 477 (14.0) | 2940 (86.0) | 7.43 (6.34–8.70) | |

| P for interaction | 0.49 | |||

ER, estrogen receptor; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

Figure 1.

Association of hormone receptor status by time interval between two bilateral breast cancers.

There was also a strong association in PR status between two tumors, with OR of 4.22 (95% CI: 3.92–4.55) for contralateral pairs (Table 2). The strength of association decreased as the time interval between two tumors increased (Figure 1, p<0.0001): the OR was 12.3 for synchronous cases and 1.87 for metachronous cancers separated by 10 years or longer. The strength of association in PR status between bilateral cancers did not vary after 12 months (p=0.28). The association in PR status between two bilateral tumors was stronger among patients younger than 50 years than among patients 50 years and older (p<0.0001). These results paralleled those seen for ER status, except that the magnitude of associations was weaker for PR status.

Table 2.

Association of progesterone receptor status in patients with two primary breast cancers, SEER 1990–2006

| PR of first cancer | PR of contralateral cancer |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative No. (%) | Positive No. (%) | OR (95% CI) | ||

| All patients | Negative | 2421 (56.7) | 1848 (43.3) | |

| Positive | 2554 (23.7) | 8230 (76.3) | 4.22 (3.92–4.55) | |

| Lag interval | ||||

| < 1 month | Negative | 724 (61.6) | 452 (38.4) | |

| Positive | 458 (11.5) | 3511 (88.5) | 12.3 (10.5–14.3) | |

| 1–5 months | Negative | 316 (56.0) | 248 (44.0) | |

| Positive | 211 (12.4) | 1494 (87.6) | 9.02 (7.24–11.2) | |

| 6–11 months | Negative | 98 (56.0) | 77 (44.0) | |

| Positive | 140 (34.4) | 267 (65.6) | 2.43 (1.69–3.49) | |

| 12–59 months | Negative | 729 (56.4) | 541 (42.6) | |

| Positive | 937 (38.2) | 1515 (61.8) | 2.18 (1.90–2.50) | |

| ≥ 60 months | Negative | 454 (51.1) | 530 (48.9) | |

| Positive | 808 (35.9) | 1443 (64.1) | 1.87 (1.61–2.16) | |

| P for interaction | <0.0001 | |||

| Age at first cancer | ||||

| < 50 years | Negative | 813 (68.9) | 367 (31.1) | |

| Positive | 517 (23.8) | 1652 (76.2) | 7.08 (6.04–8.29) | |

| ≥ 50 years | Negative | 1608 (52.1) | 1481 (47.9) | |

| Positive | 2037 (23.6) | 6578 (76.4) | 3.51 (3.22–3.82) | |

| P for interaction | <0.0001 | |||

| Stage of first cancer | ||||

| In situ | Negative | 186 (58.3) | 133 (41.7) | |

| Positive | 146 (15.5) | 798 (84.5) | 7.64 (5.75–10.2) | |

| Localized | Negative | 1443 (54.6) | 1202 (45.4) | |

| Positive | 1650 (23.8) | 5293 (76.2) | 3.85 (3.50–4.23) | |

| Regional | Negative | 792 (60.7) | 513 (39.3) | |

| Positive | 758 (26.2) | 2139 (73.8) | 4.36 (3.79–5.00) | |

| P for interaction | <0.0001 | |||

PR, progesterone receptor; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

There was a significant concordance in tumor grade between the first and second breast cancers, with a global OR of 2.80 (95% CI: 2.65–2.95) for bilateral pairs (Table 3). The association in grade also depended on the time interval between two tumors (Figure 2, p<0.0001). There was a clear trend of global OR decreasing as the time interval between two tumors increased (p<0.0001) but stabilized after 12 months (global OR around 2.3; p=0.46). Similar to results for hormone receptors, the association in tumor grade between two bilateral tumors was stronger among patients younger than 50 years than among patients 50 years and older (p<0.0001). The strength of association in tumor grade between two bilateral tumors was stronger among patients with metastatic disease than among other patients.

Table 3.

Association of tumor grade in patients with two primary breast cancers, SEER 1990–2006

| Grade of first cancer | Grade of contralateral cancer |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I No. (%) | II No. (%) | III No. (%) | GOR (95% CI) | ||

| All patients | I | 1650 (40.4) | 1633 (40.0) | 803 (19.7) | |

| II | 1926 (22.8) | 4331 (51.2) | 2203 (26.0) | ||

| III | 991 (14.7) | 2273 (33.8) | 3456 (51.4) | 2.80 (2.65–2.95) | |

| Lag interval | |||||

| < 1 month | I | 655 (45.2) | 577 (39.8) | 217 (15.0) | |

| II | 544 (20.1) | 1624 (60.0) | 538 (19.9) | ||

| III | 208 (12.2) | 531 (31.2) | 963 (56.6) | 3.48 (3.21–3.76) | |

| 1–5 months | I | 368 (56.5) | 217 (33.3) | 66 (10.1) | |

| II | 414 (29.2) | 777 (54.7) | 229 (16.1) | ||

| III | 181 (19.7) | 356 (38.8) | 381 (41.5) | 3.12 (2.81–3.47) | |

| 6–11 months | I | 58 (33.9) | 74 (43.3) | 39 (22.8) | |

| II | 111 (28.2) | 178 (45.2) | 105 (26.6) | ||

| III | 73 (23.3) | 102 (32.6) | 138 (44.1) | 1.96 (1.61–2.38) | |

| 12–59 months | I | 339 (32.0) | 450 (42.5) | 269 (25.4) | |

| II | 487 (21.5) | 1011 (44.7) | 762 (33.7) | ||

| III | 294 (13.9) | 693 (32.8) | 1124 (53.2) | 2.44 (2.24–2.66) | |

| ≥ 60 months | I | 230 (30.4) | 315 (41.6) | 212 (28.0) | |

| II | 370 (22.0) | 741 (44.1) | 569 (33.9) | ||

| III | 235 (14.0) | 591 (35.3) | 850 (50.7) | 2.23 (2.02–2.45) | |

| P for interaction | <0.0001 | ||||

| Age at first cancer | |||||

| < 50 years | I | 222 (36.4) | 258 (42.3) | 130 (21.3) | |

| II | 308 (18.9) | 821 (50.3) | 503 (30.8) | ||

| III | 205 (9.4) | 618 (28.2) | 1369 (62.5) | 3.60 (3.27–3.96) | |

| ≥ 50 years | I | 1428 (41.1) | 1375 (39.6) | 673 (19.4) | |

| II | 1618 (23.7) | 3510 (51.4) | 1700 (24.9) | ||

| III | 786 (17.4) | 1655 (36.6) | 2087 (46.1) | 2.44 (2.31–2.59) | |

| P for interaction | <0.0001 | ||||

| Stage of first cancer | |||||

| In situ | I | 204 (40.1) | 195 (38.3) | 110 (21.6) | |

| II | 273 (22.3) | 647 (52.9) | 302 (24.7) | ||

| III | 206 (16.9) | 478 (39.2) | 534 (43.8) | 2.36 (2.11–2.64) | |

| Localized | I | 1163 (39.3) | 1210 (40.9) | 584 (19.7) | |

| II | 1155 (22.8) | 2564 (50.7) | 1341 (26.5) | ||

| III | 457 (14.0) | 1064 (32.6) | 1740 (53.4) | 2.82 (2.65–3.00) | |

| Regional | I | 283 (45.6) | 228 (36.8) | 109 (17.6) | |

| II | 498 (22.9) | 1120 (51.4) | 560 (25.7) | ||

| III | 328 (14.6) | 731 (32.6) | 1182 (52.7) | 3.05 (2.79–3.33) | |

| P for interaction | 0.0008 | ||||

GOR, global odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

Figure 2.

Association of tumor grade and histologic type by time interval between two bilateral breast cancers.

Table 4 cross-tabulates 3-category histologic type between the primary and second breast cancer. There was a significant concordance in histologic type, with a global OR of 3.04 (95% CI: 2.91–3.18). The association in histologic type depended on the time interval between two tumors (Figure 2, p<0.0001): it was higher in tumors separated within 6 months but was stable after 12 months (global OR around 2.3; p=0.39). Furthermore, the association in histologic type was stronger among patients younger than 50 years than among patients 50 years and older (p=0.02). The strength of association in histologic type between two bilateral tumors was stronger among patients with metastatic disease as the first diagnosis than among other patients. The results for 9-category histologic type were similar (results not shown).

Table 4.

Association of histologic type in patients with two primary breast cancers, SEER 1990–2006

| Histology of first cancer | Histology of contralateral cancer |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ductal No. (%) | Lobular No. (%) | Other No. (%) | GOR (95% CI) | ||

| All patients | Ductal | 13368 (69.6) | 3261 (17.0) | 2578 (13.4) | |

| Lobular | 2729 (39.9) | 3430 (50.1) | 686 (10.0) | ||

| Other | 2696 (59.1) | 798 (17.5) | 1071 (23.5) | 3.04 (2.91–3.18) | |

| Lag interval | |||||

| < 1 month | Ductal | 4013 (74.9) | 772 (14.4) | 573 (10.7) | |

| Lobular | 828 (36.5) | 1255 (55.3) | 186 (8.2) | ||

| Other | 593 (51.1) | 187 (16.1) | 380 (32.8) | 5.07 (4.66–5.51) | |

| 1–5 months | Ductal | 1751 (60.5) | 705 (24.4) | 436 (15.1) | |

| Lobular | 486 (27.6) | 1104 (62.8) | 168 (9.6) | ||

| Other | 273 (46.8) | 156 (26.8) | 154 (26.4) | 3.23 (2.90–3.60) | |

| 6–11 months | Ductal | 577 (65.1) | 170 (19.2) | 139 (15.7) | |

| Lobular | 147 (39.3) | 182 (48.7) | 45 (12.0) | ||

| Other | 134 (55.8) | 51 (21.3) | 55 (22.9) | 2.40 (1.99–2.89) | |

| 12–59 months | Ductal | 3808 (68.0) | 919 (16.4) | 874 (15.6) | |

| Lobular | 698 (48.7) | 558 (38.9) | 178 (12.4) | ||

| Other | 891 (63.6) | 205 (14.6) | 305 (21.8) | 2.22 (2.06–2.41) | |

| ≥ 60 months | Ductal | 3219 (72.0) | 695 (15.5) | 556 (12.4) | |

| Lobular | 570 (56.4) | 331 (32.8) | 109 (10.8) | ||

| Other | 805 (68.2) | 199 (16.9) | 177 (15.0) | 2.31 (2.12–2.52) | |

| P for interaction | <0.0001 | ||||

| Age at first cancer | |||||

| < 50 years | Ductal | 3249 (69.8) | 835 (17.9) | 571 (12.3) | |

| Lobular | 566 (35.4) | 899 (56.3) | 132 (8.3) | ||

| Other | 645 (59.9) | 204 (18.9) | 228 (21.2) | 3.33 (3.05–3.63) | |

| ≥ 50 years | Ductal | 10119 (69.5) | 2426 (16.7) | 2007 (13.8) | |

| Lobular | 2163 (41.2) | 2531 (48.2) | 554 (10.6) | ||

| Other | 2051 (58.8) | 594 (17.0) | 843 (24.2) | 2.96 (2.82–3.11) | |

| P for interaction | 0.02 | ||||

| Stage of first cancer | |||||

| In situ | Ductal | 2272 (67.4) | 649 (19.2) | 452 (13.4) | |

| Lobular | 577 (36.7) | 859 (54.7) | 135 (8.6) | ||

| Other | 1053 (58.2) | 339 (18.7) | 417 (23.1) | 2.82 (2.59–3.08) | |

| Localized | Ductal | 7722 (69.9) | 1831 (16.6) | 1498 (13.6) | |

| Lobular | 1410 (43.1) | 1497 (45.7) | 366 (11.2) | ||

| Other | 1327 (59.9) | 370 (16.7) | 518 (23.4) | 2.86 (2.69–3.03) | |

| Regional | Ductal | 3374 (70.5) | 781 (16.3) | 628 (13.1) | |

| Lobular | 742 (37.1) | 1074 (53.7) | 185 (9.2) | ||

| Other | 316 (58.4) | 89 (16.5) | 136 (25.1) | 3.79 (3.46–4.15) | |

| P for interaction | <0.0001 | ||||

GOR, global odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

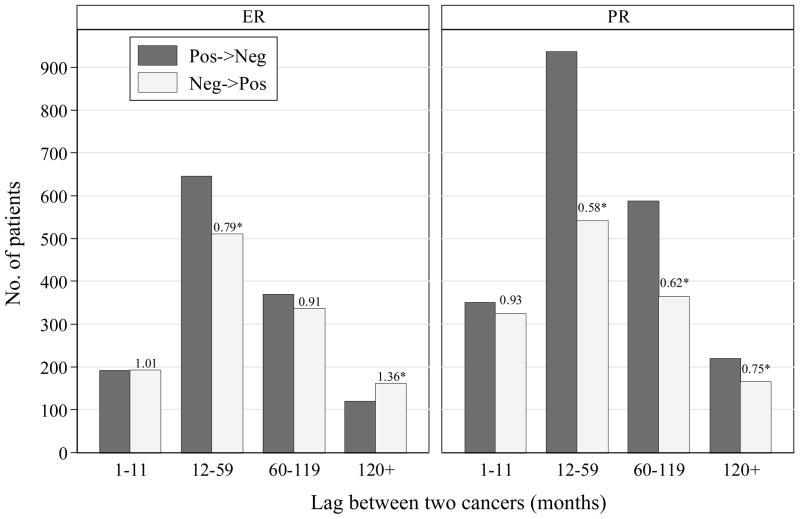

Figure 3 presents the number of patients whose hormone receptor status changed from first to second breast cancer. The comparison of the number of patients whose hormone receptor status changing from positive to negative and the number changing from negative to positive is equivalent to the comparison of hormone receptor proportion between two time points. Both the proportions of ER and PR positivity were the same between two cancers separated by less than 1 year. The ER positivity decreased by 21% (OR=511/646=0.79, 95% CI: 0.70–0.89) in second contralateral breast cancers occurring 12–59 months after the first tumors, and was the same between the first tumors and the tumors occurring after 60 months. The PR positivity decreased by 42% (OR=541/937=0.58, 95% CI: 0.52–0.64) in second contralateral breast cancers occurring 12–59 months after the first tumors, and this reduction remained significant even for contralateral cancer occurring after 120 months.

Figure 3.

Number of patients who changed status of estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor from first to second breast cancer, by time interval between two bilateral breast cancers. The numbers on top of bars are odds ratios for hormone receptor positivity (OR<1 means reduction; star indicates p<0.05).

DISCUSSION

This study investigated a large cohort of patients diagnosed with two breast cancers within a national database and demonstrated a strong concordance in both ER and PR status between a primary and second breast cancers. This results are consistent with those reported from hospital-based series3, 4, 7–10 and hereditary breast cancer patients.5 Weitzer et al. showed that the odds ratio for ER status between primary and contralateral breast cancer was 6.4 for BRCA1 carriers and 9.5 for BRCA2 carriers,5 which are similar to the odds ratio of 7.64 for bilateral breast cancers in our study. Our study also confirmed previous findings that the concordance in ER was stronger in synchronous cancers than in metachronous cancers,3, 5, 8, 11 Thank to the large sample size, this study depicts the relationship between the degree of concordance in ER status and the time interval between two tumors: the association in ER status between two tumors decreased as the time interval between two tumors increased but reached plateau after 12 months. The association was still highly significant even for two tumors separated by 10 years. Our observation of continuous relationship suggests that there is no biological cutoff point for synchronous breast cancer. If we were forced to choose one, we would prefer to 12 months as diagnostic period for a synchronous breast cancer. Note that previous studies have used different diagnostic period for a synchronous breast cancer (0 to 24 months).3, 5, 8, 11 We also demonstrated the strength of association in ER status was stronger among patients younger than 50 years. Very similar patterns were observed for PR status, but the strength of association for PR status was weaker than for ER status overall and in each stratum, reflecting that PR is an ER-regulated gene and that its production depends on estrogen and ER.14

The study also found significant concordance in tumor grade and histologic type between the primary cancer and second breast cancer. However, the strength of association for these two morphologic characteristics was weaker than that for hormone receptors. Similar to hormone receptor, time interval between two tumors and age at diagnosis modified the association in tumor grade.

We found that surgery and radiotherapy had no effect on the association in the four histopathologic characteristics examined in this study. A previous study reported that tamoxifen treatment attenuated the association in ER status between primary and contralateral breast cancer.10 Endocrine therapy was not recorded in the SEER database, so this study can only provide a population-based estimate on hormone receptor concordance in the era of tamoxifen. In the US,, the proportion of adjuvant tamoxifen use in breast cancer patients rapidly increased from 1987 to 1991 and reached about 40–60% in 1999, and patients with ER positive tumors were more likely to use tamoxifen than patients with ER negative tumors.15, 16 In this study, we found the odds of ER or PR positivity decreased by about 21–42% comparing a breast cancer occurring 12–59 months after the first cancer and the primary cancer. These findings may be explained by tamoxifen use in cancer patients because tamoxifen decreases the risk of ER positive breast cancer but does not reduce the risk of ER negative cancer 17, 18.

The findings from this epidemiologic study may shed light on the understanding of breast carcinogenesis, particularly the debate between a monoclonal or multicentric origin of cancer. It is unclear whether the second cancer represents an independent second primary tumor versus a sequential event of a primary tumor. We found there is a clear gradient that the association for all four pathologic features decreased as the time interval between two tumors increased within 12 months but reached plateau after 12 months, suggesting that biological closeness of two tumors is a function of time. We postulate that intramammary spread of a single primary cancer may exist for two bilateral tumors that are clinically manifest within 12 months (synchronous cases).

Can we believe that two cancers developed from different origins are similar? Probably yes. Theoretically, two cancers in a woman are subjected to the same hormonal, environmental, and genetic influences. Empirically, we demonstrated that a strong concordance in hormone receptor, grade, or histologic type exists in subpopulations with less contamination from metastasic disease, such as patients with in situ contralateral cancer. Breast cancer develops from an accumulation of a series of mutations or epigenetic alterations, probably in mammary stem/progenitor cells because these cells have slow-dividing, long-living, and self-renewal properties.19 Several breast cancer molecular subtypes have been proposed based on gene expression profiling, with the ESR gene being a cornerstones of the molecular classification.20 However, it is unclear whether these subtypes have distinct cancer stem cells of their own. Our data support the model that ER positive and ER negative tumors arise from different stem/progenitor cells.21 The study observed that two bilateral cancers occurring 10 year apart are still likely to have the same tumor features, and two bilateral cancers occurring in patients younger than 50 have stronger similarity than bilateral cancers occurring in patients 50 or older. These findings suggest that tumor subtypes as indicated by ER/PR status are established in the early steps of breast carcinogenesis. This predisposition of breast cancer subtypes may be determined by genetic susceptibility and environmental risk factors exposed in early life. For example, BRCA1-related breast cancer was mainly basal-like breast cancer22 and low-penetrant genetic variants were ER-specific.23

To our knowledge, this is the largest study to investigate the concordance in cancer characteristics in patients with two breast cancers. The large sample size not only reconciled the inconsistence in previous studies but also facilitate subgroup analysis to answer several subtle research questions with certainty. Patients were from population-based registries which makes the study findings applicable to general population. However, there are several limitations to our study. First, assays of hormone receptor were not standardized across clinics in SEER although a recent study showed that ER measurement is reliable for SEER registries.24 Nevertheless, the misclassification should be to reduce the strength of true association so we would observe stronger association if standardized assay were available. Second, primary breast cancer rather than recurrent or metastatic breast cancers were presumably recorded in SEER, but it is still possible that some metastatic cancers made it into the registries.

In summary, we observed strong associations in hormone receptor, tumor grade, and histologic type between two bilateral breast cancers of the same patients, which support the model that two tumors arise in a common milieu and tumor subtypes are predetermined in the early stage of breast carcinogenesis. This finding has important implication in the prevention and management of second breast cancers. For a specific individual with initial breast cancer, the risk factors for her second breast cancer may be the same as the first one and a similar systemic management may be used for her second cancer. We also observed a reduction of ER/PR positive proportion for second breast cancer compared with the first one, which may be explained by hormonal therapy for the initial cancer.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Husain Sattar and James Dignam for helpful discussion on breast cancer metastasis and Michelle Porcellino for critical reading of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (R03 CA132143-01A1 and P50 CA125183).

Footnotes

The authors have no financial disclosures.

References

- 1.Bernstein JL, Lapinski RH, Thakore SS, Doucette JT, Thompson WD. The descriptive epidemiology of second primary breast cancer. Epidemiology. 2003;14(5):552–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000072105.39021.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurian AW, McClure LA, John EM, Horn-Ross PL, Ford JM, Clarke CA. Second primary breast cancer occurrence according to hormone receptor status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(15):1058–65. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kollias J, Pinder SE, Denley HE, Ellis IO, Wencyk P, Bell JA, et al. Phenotypic similarities in bilateral breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;85(3):255–61. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000025421.00599.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hahnel R, Twaddle E. The relationship between estrogen receptors in primary and secondary breast carcinomas and in sequential primary breast carcinomas. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1985;5(2):155–63. doi: 10.1007/BF01805989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weitzel JN, Robson M, Pasini B, Manoukian S, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Lynch HT, et al. A comparison of bilateral breast cancers in BRCA carriers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(6):1534–8. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arpino G, Weiss HL, Clark GM, Hilsenbeck SG, Osborne CK. Hormone receptor status of a contralateral breast cancer is independent of the receptor status of the first primary in patients not receiving adjuvant tamoxifen. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(21):4687–94. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Intra M, Rotmensz N, Viale G, Mariani L, Bonanni B, Mastropasqua MG, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics of 143 patients with synchronous bilateral invasive breast carcinomas treated in a single institution. Cancer. 2004;101(5):905–12. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coradini D, Oriana S, Mariani L, Miceli R, Bresciani G, Marubini E, et al. Is steroid receptor profile in contralateral breast cancer a marker of independence of the corresponding primary tumour? Eur J Cancer. 1998;34(6):825–30. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)10121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gong SJ, Rha SY, Jeung HC, Roh JK, Yang WI, Chung HC. Bilateral breast cancer: differential diagnosis using histological and biological parameters. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2007;37(7):487–92. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hym056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swain SM, Wilson JW, Mamounas EP, Bryant J, Wickerham DL, Fisher B, et al. Estrogen receptor status of primary breast cancer is predictive of estrogen receptor status of contralateral breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(7):516–23. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holdaway IM, Mason BH, Bennett RC, Alexander AI, Hahnel R, Kiang DT. Estrogen receptors in bilateral breast cancer. Cancer. 1988;62(1):109–13. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880701)62:1<109::aid-cncr2820620120>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Limited-Use Data. National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch; 2009. pp. 1973–2006. ( www.seer.cancer.gov) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42(1):121–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cui X, Schiff R, Arpino G, Osborne CK, Lee AV. Biology of progesterone receptor loss in breast cancer and its implications for endocrine therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(30):7721–35. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mariotto A, Feuer EJ, Harlan LC, Wun LM, Johnson KA, Abrams J. Trends in use of adjuvant multi-agent chemotherapy and tamoxifen for breast cancer in the United States: 1975–1999. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(21):1626–34. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.21.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mariotto AB, Feuer EJ, Harlan LC, Abrams J. Dissemination of adjuvant multiagent chemotherapy and tamoxifen for breast cancer in the United States using estrogen receptor information: 1975–1999. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2006;(36):7–15. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgj003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, Redmond CK, Kavanah M, Cronin WM, et al. Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: report of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90(18):1371–88. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.18.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cuzick J, Powles T, Veronesi U, Forbes J, Edwards R, Ashley S, et al. Overview of the main outcomes in breast-cancer prevention trials. Lancet. 2003;361(9354):296–300. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12342-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(7):3983–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406(6797):747–52. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dontu G, El-Ashry D, Wicha MS. Breast cancer, stem/progenitor cells and the estrogen receptor. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2004;15(5):193–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foulkes WD, Stefansson IM, Chappuis PO, Begin LR, Goffin JR, Wong N, et al. Germline BRCA1 mutations and a basal epithelial phenotype in breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(19):1482–5. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia-Closas M, Hall P, Nevanlinna H, Pooley K, Morrison J, Richesson DA, et al. Heterogeneity of breast cancer associations with five susceptibility loci by clinical and pathological characteristics. PLoS Genet. 2008;4(4):e1000054. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma H, Wang Y, Sullivan-Halley J, Weiss L, Burkman RT, Simon MS, et al. Breast cancer receptor status: do results from a centralized pathology laboratory agree with SEER registry reports? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(8):2214–20. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]