Abstract

Although normally absent, spontaneous pacemaker activity can develop in human atrium to promote tachyarrhythmias. HL-1 cells are immortalized atrial cardiomyocytes that contract spontaneously in culture, providing a model system of atrial cell automaticity. Using electrophysiologic recordings and selective pharmacologic blockers, we investigated the ionic basis of automaticity in atrial HL-1 cells. Both the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca++ release channel inhibitor ryanodine and the SR Ca++ ATPase inhibitor thapsigargin slowed automaticity, supporting a role for intracellular Ca++ release in pacemaker activity. Additional experiments were performed to examine the effects of ionic currents activating in the voltage range of diastolic depolarization. Inhibition of the hyperpolarization-activated pacemaker current, If, by ivabradine significantly suppressed diastolic depolarization, with modest slowing of automaticity. Block of inward Na+ currents also reduced automaticity, while inhibition of T- and L-type Ca++ currents caused milder effects to slow beat rate. The major outward current in HL-1 cells is the rapidly activating delayed rectifier, IKr. Inhibition of IKr using dofetilide caused marked prolongation of APD and thus spontaneous cycle length. These results demonstrate a mutual role for both intracellular Ca++ release and sarcolemmal ionic currents in controlling automaticity in atrial HL-1 cells. Given that similar internal and membrane-based mechanisms also play a role in sinoatrial nodal cell pacemaker activity, our findings provide evidence for generalized conservation of pacemaker mechanisms among different types of cardiomyocytes.

Keywords: automaticity, pacemaker activity, HL-1 cells, atrial cells, ryanodine receptors

INTRODUCTION

Automaticity, or spontaneous phase 4 diastolic depolarization, is normally a property of myocytes in the sinoatrial node (SAN) and cardiac conduction system. However, in some cases, spontaneous pacemaker activity can also develop in the atrium. There is increasing evidence that abnormal automaticity originating from atrial myocytes plays an important role in the initiation of atrial fibrillation (AF). In humans, repetitive ectopic activity causing atrial tachycardia (AT), and ultimately AF, has been mapped to sites in the right and left atrium, clustering at the origins of the pulmonary veins.1 At these locations, left atrial tissue extends into the pulmonary venous sleeve. Upon isolation, a proportion of pulmonary vein myocytes and atrial-vein preparations demonstrate spontaneous automaticity.2-4 However, this has not been a consistent finding,5,6 hampering investigation of atrial cell automaticity. Thus, the cellular mechanisms that regulate this process are currently not well understood.

Recent work has highlighted the usefulness of atrial cell-based preparations as in vitro models for AF.7-10 Atrial HL-1 cells are a cardiac cell line derived from the AT-1 cell lineage.11 Although they can be serially passaged, these cells retain a differentiated adult atrial cardiomyocyte phenotype, including typical ionic currents required to generate characteristic action potentials.12 Previously, we showed that rapid stimulation of atrial HL-1 cells in culture results in electrical remodeling resembling that observed with AT and AF, with reduced action potential duration (APD) and Ca++ currents,8 as well as conservation of transcriptional remodeling.13 The utility of the atrial HL-1 model system has been confirmed by others, with experimental results that correlate with findings in both human AF and in vivo AT models.9,10

Interestingly, atrial HL-1 cells beat spontaneously in culture in a reproducible manner, providing a unique opportunity to investigate atrial cell automaticity. In SAN cells, the precise mechanisms that initiate automatic activity remain controversial, despite many years of investigation. Extensive studies have elucidated a complex interaction between activity of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) and voltage-gated ion channels/exchangers in the plasma membrane to control pacemaker activity.14 In SAN cells, substantial evidence demonstrates an important role for If, also sometimes termed the pacemaker current, in regulating automaticity.15 Other sarcolemmal currents, including Na+, Ca++, and K+ currents, that are present in pacemaker cells have also shown to modulate beat rate.14 In addition, recent studies have identified local rhythmic Ca++ releases from the SR in late diastole that play a role in the initiation of action potential firing.16,17 In atrial HL-1 cells, multiple ionic currents have been identified by us and others in previous voltage clamp studies. However, the ionic basis for automaticity in this atrial cell model has not been previously investigated. In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that, as for SAN cells, the ionic mechanisms that control pacemaker activity in atrial HL-1 cells include both SR and membrane-based components.

METHODS

Materials

Analytical grade reagents, mibefradil, nimodipine, lidocaine, tetrodotoxin, 8-chlorophenylthio-cAMP (8-cpt-cAMP), forskolin, and 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Ryanodine was obtained from Alexis Biochemicals, while thapsigargin was purchased from Calbiochem. Ivabradine was kindly provided by the Institut de Recherches Internationales Servier (Suresnes, France), while dofetilide was obtained from Dr. Michael Murawsky at Procter & Gamble Pharmaceuticals.

Experimental Preparation

Atrial HL-1 cells were kindly provided by Dr. William Claycomb (Louisiana State University Health Science Center, New Orleans, LA). Cells were cultured under a 5% CO2 atmosphere in supplemented Claycomb medium (Sigma-Aldrich) as previously described.8 Culture dishes (35 mm) were preplated with a sterilized coverslip (22 mm) coated overnight with 0.012 mg/ml fibronectin and 0.2 mg/ml gelatin. Dishes were seeded with HL-1 cells so that ≥ 90% confluency was reached at 96 hr.

Automaticity was investigated using recordings from a cellular syncytium rather than single atrial HL-1 cells based on initial experimental observations. When acutely dissociated, single atrial HL-1 cells did not consistently demonstrate spontaneous beating; in current clamp mode, spontaneous beating did develop in ~65% of cells, with a beat rate of ~60-80 bpm, which was several times slower than that observed for the cellular syncytium (~150-180 bpm). Thus, the phenotype of single cells was markedly disparate from that observed in a multicellular preparation, possibly related to the enzymatic dissociation process required to obtain single cells. In addition, atrial HL-1 cells have well-described gap junctions, with electrical coupling and syncytial beating. Beat rate was essentially identical for multiple cellular recordings obtained in a specific region on a coverslip, regardless of whether cells were “drivers” or “followers” (see Results). Thus, the beat rate recorded from an individual cell in the syncytium reflected the overall beat rate for that group of electrically coupled myocytes.

Electrophysiologic Recordings and Data Analysis

Spontaneous action potentials were recorded at 37°C using the current clamp technique from the cell layer on coverslips perfused at a constant flow rate of 2 mL/min. The extracellular Tyrodes's solution was bubbled with 100% O2 and contained (in mM): NaCl 145; KCl 4; MgCl2 1; CaCl2 1.8; and HEPES 10 (pH 7.4). Data were acquired using the current clamp mode of an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA) connected to a Digidata 1320A interface (Axon Instruments), with a pipette tip resistance of 1.5-2.5 MΩ. The pipette-filling solution contained (in mM): K-aspartate 120; EGTA 10; Na2phosphocreatine 2; Na2ATP 4; NaGTP 2; and HEPES 5 (pH 7.2). Spontaneous action potentials were selected for experimentation based on the following criteria: 1) the resting membrane potential was at least -55mV; 2) the overshoot exceeded 20mV; 3) the rhythmicity was regular; and 4) the spontaneous cycle length was stable for ~5 min. For such cells, spontaneous beat rate remained stable under baseline or control conditions for 34±3 min (202±6 and 200±3 bpm at t=0 and 34 min, respectively; n=12). Data acquisition was performed using pClamp 9.2 (Axon Instruments), with analysis using pClamp 9.2 and Origin 7.5 (Origin Lab Corporation, North Hampton, MA). Action potential duration at 30, 50, and 90% repolarization was determined (APD30, APD50, and APD90, respectively), as well as the time to maximal diastolic potential (MDP), or APD100. Diastolic depolarization time (DDT) was defined as the interval from MDP to threshold of the next action potential. The slope of diastolic depolarization was essentially linear, with a single component, for nearly all recorded action potentials. Therefore, the slope was estimated by dividing the amplitude of depolarization during diastole (diastolic depolarization potential, or DDP) by the duration of diastolic depolarization (DDT).

For whole-cell recordings, single atrial HL-1 cells were isolated from coverslips using a 5 min enzymatic dissociation with 0.05% trypsin-EDTA. Digestion was stopped by adding 0.025% trypsin inhibitor and medium, and the sedimented cells were used for experiments within 6 hours. Ionic currents were recorded at 22-24°C, with signals low-pass filtered and sampled as appropriate for the current under study as previously described.8 To record If, a modified Tyrode bath solution was used that contained (in mM): NaCl 140; KCl 25 (to amplify If); MgCl2 1.2; CaCl2 1.8; HEPES 5; Mibefradil 10μM; nimodipine 2μM; BaCl2 2; and 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) 3μM (pH=7.4); the pipette-filling solution contained: K-DL-aspartate 120; tetraethylammonium (TEA)-Cl 10; CaCl2 5; EGTA-CsOH 11; MgCl2 2; Na2ATP 5; NaGTP 0.4; and HEPES 10 (pH=7.2). To record INa, the external K-free solution contained: NaCl 20; CsCl 110; MgCl2 1; CaCl2 0.1; TEA-Cl 5; HEPES 10; Mibefradil 10μM, nimodipine 2μM; BaCl2 2; 4-AP 3μM (pH=7.4). The pipette solution contains (in mM): K-aspartate 120; KCl 25; MgCl2 1; EGTA 10; Na2 phosphocreatine 2; Na2ATP 4; NaGTP 2 and HEPES 5 (pH=7.2).

For pharmacologic experiments to investigate the role of specific channel complexes in automaticity, spontaneous action potentials were recorded before and every 1 min during exposure of cells to a blocker selective for the current under study until drug-induced changes reached steady-state. For these experiments, the blocker concentration selected was at the initial top of the dose response curve, in order to achieve maximal block while optimizing selectivity. For ivabradine, dofetilide, mibefradil, nimodipine and tetrodotoxin, we generated dose response curves in atrial HL-1 cells8 (see also Figures 4 and 5), while for lidocaine, data obtained from SCN5A currents expressed in mammalian cells were used.18,19 Potent activation of protein kinase A (PKA) was achieved by bath superfusion of 8-cpt-cAMP (200μM), forskolin (10μM), and IBMX (100μM) as described previously.20 Changes in beat rate were characterized as mild (<20%), modest (20-40%), and substantial (>40%).

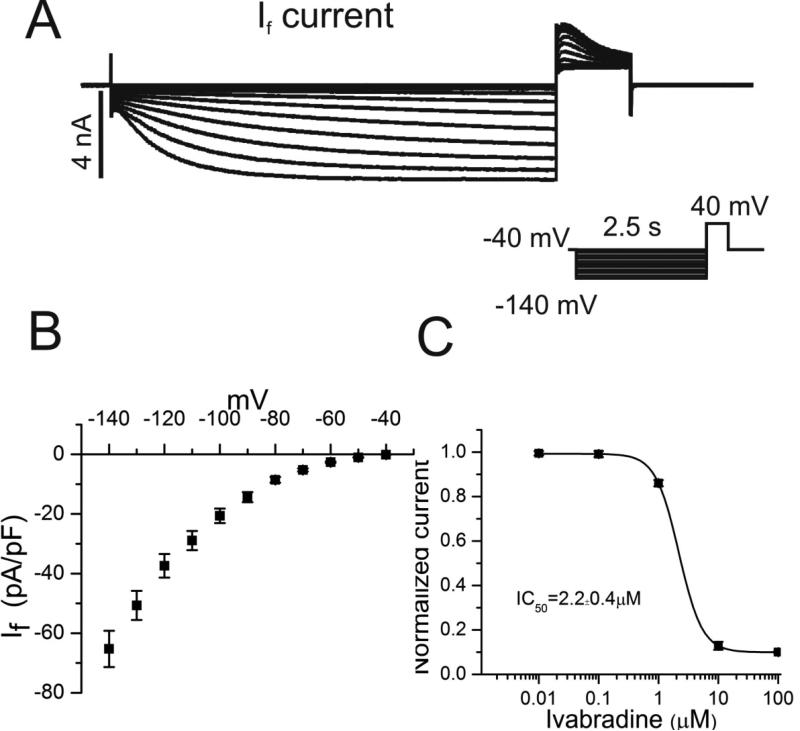

Figure 4. Hyperpolarization-activated pacemaker current, If, in atrial HL-1 cells.

A A family of If currents was recorded using the voltage clamp protocol shown in the inset. B Summary data illustrates the current-voltage (IV) relationship derived from maximal steady-state currents (n=25). C Concentration-response relationship for ivabradine block of tail currents is illustrated (n=7), with an IC50 of 2.2±0.4μM.

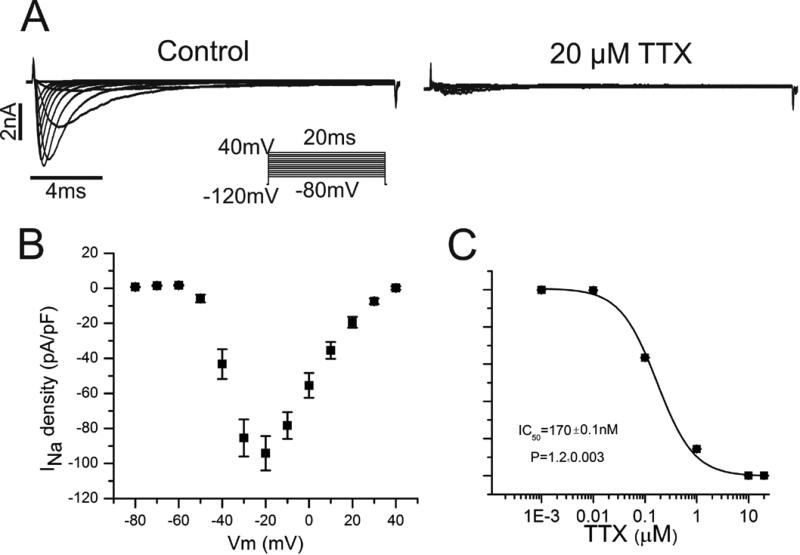

Figure 5. Cardiac Na+ current in atrial HL-1 cells.

A Using the voltage clamp protocol displayed in the inset, representative families of Na+ currents are shown before (left panel) and after (right panel) exposure to tetrodotoxin (TTX) 20μM. B Summary data demonstrates the current-voltage relationship derived from peak Na+ currents (n=10). C Concentration-response relationship for Na+ current block by TTX is illustrated (IC50 170±0.1nM; n=4).

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM, with data from control and post-drug measurements compared using a paired T-test. Analysis of the time-dependent effects of PKA activation on HL-1 cell beat rate was performed using ANOVA for repeated measures. Statistical significance was assumed for P<0.05.

RESULTS

Spontaneous Action Potentials in Atrial HL-1 cells

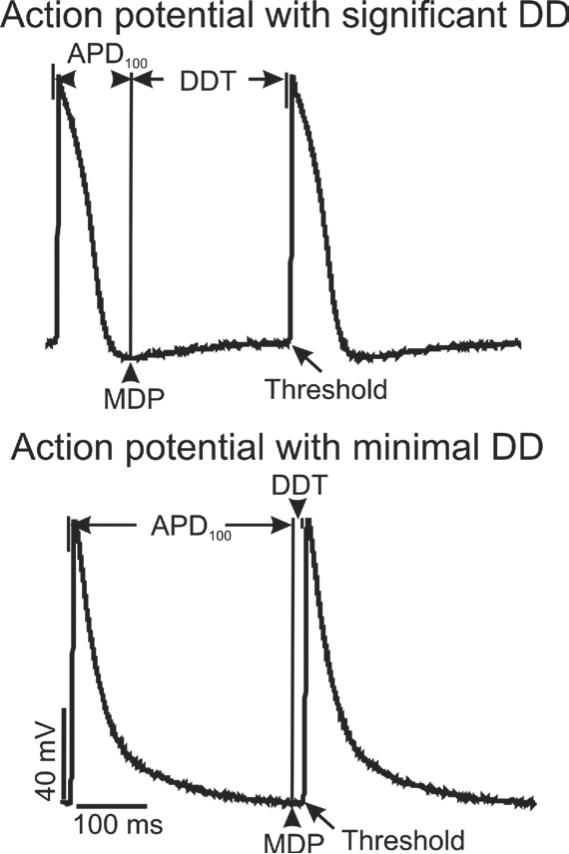

Within a syncytial preparation of atrial HL-1 cells, action potentials were recorded that generally displayed two different morphologies: those with significant or prolonged phase 4 diastolic depolarization (DD), and those essentially lacking DD, for which the maximal diastolic potential (MDP) occurred near threshold (within 20 ms) of the next action potential (Figure 1). These recordings represent cells at or near the leading pacemaker site, or “drivers”, and propagated action potentials, or “followers”, respectively. Consistent with this, the beat rate was essentially identical when recorded from multiple different cells of both morphologies within a specific region on a coverslip, indicative of electrical coupling. Cells that displayed obvious DD were most commonly observed, accounting for the majority of recorded action potentials (68%; n=96 cells total). By definition, they displayed significantly longer diastolic depolarization times (Table; DDT was 194±7 ms, compared to 6±1 ms; P<0.01), while the time required for full action potential repolarization to MDP (or APD100) was greater for cells with minimal DD (Figure 1 and Table; APD100 was 313±8 ms, compared to 139±5 ms; P<0.01). Because the focus of our study was automaticity, only data from cells with significant DD (i.e., those most likely to be at or near the focus driving pacemaker activity) under control conditions are presented below in the Results.

Figure 1. Action potentials in spontaneously-beating atrial HL-1 cells.

A Action potentials were recorded from 2 different cells in a confluent syncytium of HL-1 cells on a coverslip. The beat rate was identical, with some cells demonstrating significant, prolonged phase 4 diastolic depolarization (DD; top panel), while others did not (bottom panel). The time from maximum diastolic potential (MDP) to threshold was the diastolic depolarization time (DDT), while time to full action potential repolarization at MDP was designated APD100.

Table 1.

Action potential characteristics and effects of ion channel blockers on electrophysiologic properties in HL-1 cells†

| CL (ms) | Peak (mV) | MDP (mV) | DDT (ms) | DDP (mV) | Slope (V/s) | APD100 (ms) | APD50 (ms) | Beat rate (bpm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prolonged DD (n=65) | 333±6 | 108±1 | -66±1 | 194±7 | 4±0.2 | 19.8±2 | 139±5 | 34±1 | 180±4 |

| Short DD (n=31) | 319±7 | 111±1 | -63±5 | 6±1**†† | 2±0.2** | N/A | 313±8** | 33±2 | 188±7 |

| | |||||||||

| Control | 318±10 | 108±2 | -68±2 | 200±9 | 5±0.4 | 25.0±2 | 118±5 | 35±3 | 189±7 |

| Ryanodine 30μM (n=14) | 366±20** | 103±3 | -67±2 | 247±9** | 5±1 | 20.2±3 | 119±5 | 32±3 | 164±9** |

| | |||||||||

| Control | 380±27 | 101±3 | -65±5 | 238±7 | 4±0.2 | 16.8±2 | 142±6 | 35±1 | 158±10 |

| Thapsigargin 5 μM (n=7) | 632±19** | 96±4 | -60±4 | 492±19** | 7±1 | 14.2±2 | 140±9 | 35±2 | 95±11** |

| | |||||||||

| Control | 337±26 | 107±3 | -65±3 | 221±15 | 4±1 | 18.1±4 | 116±11 | 39±2 | 178±13 |

| PKA cocktail (n=7) | 157±17** | 106±3 | -65±4 | 43±8** | 4±1 | 93±6** | 114±6 | 38±2 | 382±14** |

| | |||||||||

| Control | 326±15 | 110±2 | -65±1 | 186±14 | 5±0.4 | 26.9±2 | 140±9 | 36±2 | 184±8 |

| Ivabradine 10μM (n=17) | 414±17** | 111±2 | -65±1 | 5±2**†† | 3±0.3** | N/A | 409±16** | 33±2 | 145±10** |

| | |||||||||

| Control | 359±10 | 109±2 | -64±1 | 212±14 | 5±0.6 | 23.6±2 | 147±11 | 35±2 | 167±5 |

| Dofetilide 1μM (n=10) | 619±18** | 99±3** | -62±1 | 240±36** | 3±0.6** | 12.5±2** | 379±33** | 82±10** | 97±6** |

| | |||||||||

| Control | 351±12 | 102±3 | -67±1 | 224±13 | 4±0.2 | 17.9±2 | 127±9 | 36±2 | 171±6 |

| Mibefradil 10μM (n=11) | 435±18** | 96±3 | -64±2 | 291±17** | 4±0.1 | 13.7±2** | 144±9 | 40±2 | 138±7** |

| | |||||||||

| Control | 328±12 | 110±2 | -65±1 | 190±13 | 4±0.5 | 21.1±3 | 138±14 | 35±3 | 183±7 |

| Nimodipine 2μM (n=8) | 377±13** | 104±2 | -63±1 | 244±19** | 4±0.4 | 16.4±5 | 133±17 | 30±3** | 159±10** |

| | |||||||||

| Control | 333±11 | 106±4 | -64±1 | 205±18 | 4±0.8 | 19.5±2 | 128±18 | 25±4 | 180±18 |

| TTX 20μM (n=7) | 561±13* | 89±5 | -58±3 | 463±13** | 6.1±1** | 16.9±2 | 98±17 | 26±5 | 107±20** |

| | |||||||||

| Control | 328±10 | 108±3 | -66±2 | 181±10 | 4.0±0.6 | 15.5±2 | 147±4 | 47±4 | 183±11 |

| Lidocaine 50μM (n=5) | 488±10 | 99±7 | -63±2 | 357±18 | 4±0.8 | 11.3±2 | 131±10 | 41±2 | 123±16 |

CL is cycle length; MDP is maximal diastolic potential; DDT is diastolic depolarization time (from MDP to threshold); DDP is diastolic depolarization potential (change in voltage from MDP to threshold); slope is diastolic depolarization slope, or MDP/DDT; APD100 is the action potential duration from threshold to MDP; APD50 is the action potential duration to 50% repolarization; N/A is not applicable.

P<0.05

P<0.01

Drug exposure (time to steady-state effects) was 36±6 min for ryanodine, thapsigargin and PKA stimulation, and 12±4 min for ion channel blockers.

Denotes “follower” action potential phenotype.

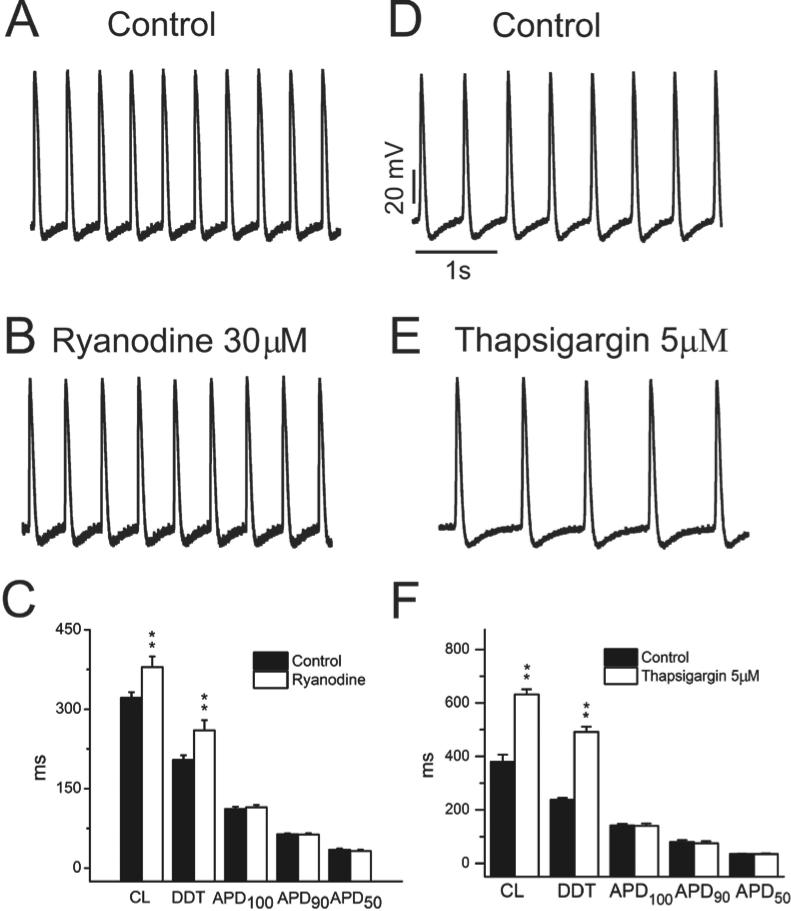

Role of SR Calcium Release

Given that local subsarcolemmal Ca++ release from the SR plays an important role in achieving action potential threshold in SAN cells,14 we examined the effects of ryanodine, which blocks SR Ca++ release through ryanodine (RYR2) receptors, on atrial HL-1 cell automaticity. At a concentration of 30μM, exposure to ryanodine caused a mild decrease in spontaneous beat rate (Figures 2A-2C, Table; from 189±7 to 164±9 bpm [13%] after 30±3 min; P<0.01). This effect was mediated by an increase in DDT, with no effect on APD at any level of repolarization (Figure 2C and Table). To further investigate the role of SR Ca++ release in automaticity, experiments were performed using the SR Ca++ ATPase (SERCA) inhibitor thapsigargin (5μM) to allow depletion of SR Ca++ stores. With exposure to thapsigargin, beat rate was modestly suppressed (Figures 2D-2F, Table; 39±10%; n=7). Taken together, our results demonstrate that SR Ca++ release likely plays a modulatory role in atrial HL-1 cell automaticity.

Figure 2. Effect of ryanodine and thapsigargin on atrial HL-cell pacemaker activity and electrophysiologic properties.

Spontaneous action potentials were recorded before (A) and after (B) bath superfusion of ryanodine 30μM (bottom panel). C Summary data showing the effects of ryanodine 30μM on electrophysiologic parameters are illustrated (n=14; **P<0.01). D-F. Similar data are displayed for thapsigargin 5μM (n=7).

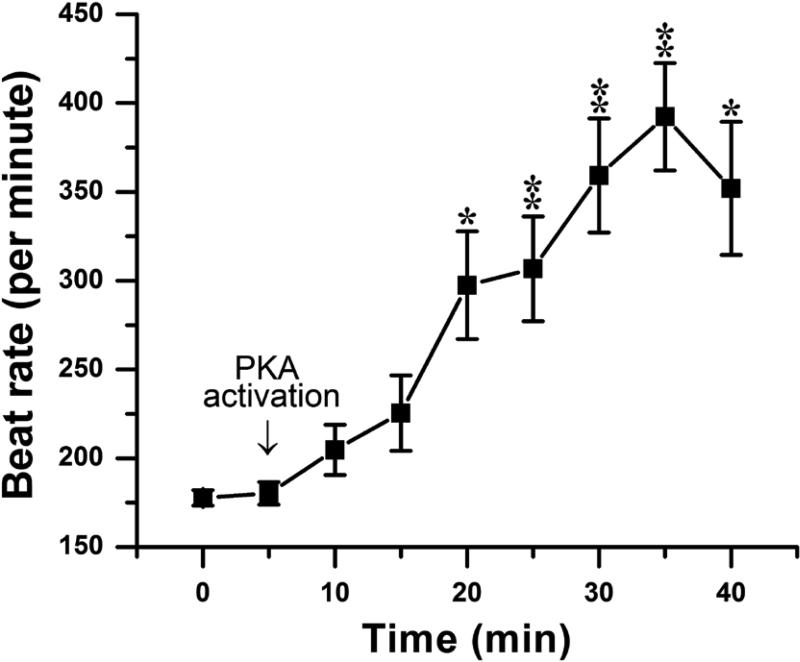

It is well recognized that activation of protein kinase A (PKA) increases automaticity in SAN cells by multiple mechanisms, including enhanced If15 and SR Ca++ release.14,21 To determine whether pacemaker activity in atrial HL-1 cells is similarly regulated, spontaneous action potentials were recorded during PKA activation. Kinase stimulation caused a time-dependent increase in beat rate of 115% (Figure 3; from 178±13 to 382±14 bpm at 35 min; P<0.01), indicating a modulatory effect of PKA activation.

Figure 3. The effect of PKA activation on spontaneous beat rate.

Beat rate is plotted over time, with the addition of PKA activators to the bath indicated by the arrow (n=7; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 compared to pre-drug value).

Identification of Candidate Sarcolemmal Ionic Currents

Because multiple voltage-gated ion channels in the plasma membrane modulate automaticity in SAN cells,14 experiments were performed using voltage clamp techniques to identify specific ionic currents in atrial HL-1 cells that might contribute to this effect. Given its prominent role in SAN automaticity, we investigated the pacemaker current, If, and its pharmacologic sensitivity. Hyperpolarization-activated inward currents consistent with If were identified in approximately one-third of cells (Figure 4A; n=25), as previously reported.22 Current kinetics and voltage dependence of channel activation resembled values obtained for adult cardiomyocytes23 (Figure 4A and 4B), and currents were inhibited by the specific If blocker ivabradine (IC50 2.2±0.4μM; Figure 4C). Studies were also conducted to investigate INa and its pharmacologic properties, which have not been previously explored in atrial HL-1 cells. Our results demonstrated characteristic cardiac Na+ currents and current-voltage (IV) relationship (Figure 5A and 5B), as well as sensitivity to block by tetrodotoxin (TTX) similar to that observed for AT-1 cells24 (Figure 5C).

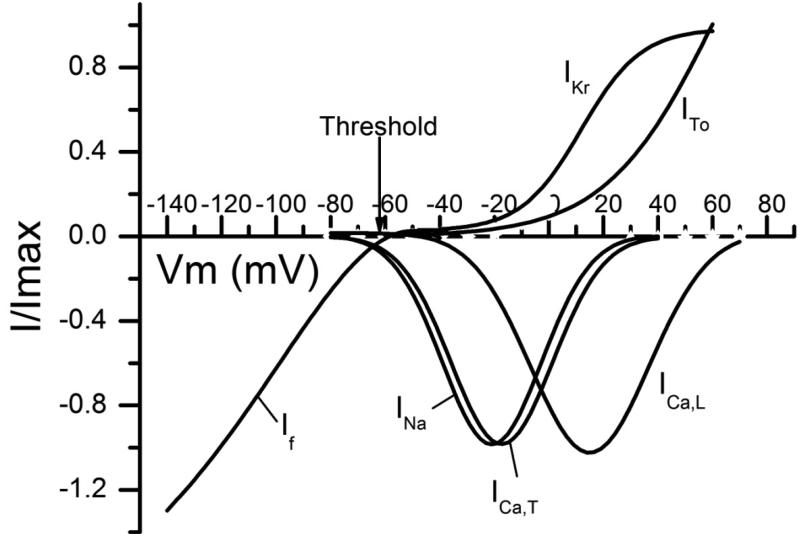

These results were combined with data from our previous work characterizing the voltage-dependent and pharmacologic properties of ICa,T and ICa,L8 in order to examine the potential relationship of individual ionic currents to automaticity in atrial HL-1 cells. Current-voltage relationships were plotted together with the action potential threshold (-61±1 mV; n=137) obtained from current clamp experiments (Figure 6). Given that the maximal diastolic potential in spontaneously-beating atrial HL-1 cells was -66±1 mV (Table), inward currents through If, INa, ICa,T, and possibly ICa,L (all of which are activated in the voltage range of ~ -70 to -60 mV) were identified as potential candidates to modulate diastolic depolarization and therefore beat rate.

Figure 6. Relationship of ionic current activation to threshold in atrial HL-1 cells.

A Using data from voltage clamp experiments, fitted activation curves were generated and plotted for ICa,L, ICa,T, ITo, and IKr,8 as well as If and INa. The threshold for spontaneously-beating atrial HL-1 cells is also indicated (-61±1 mV, n=137).

Role of Specific Ionic Currents in Automaticity

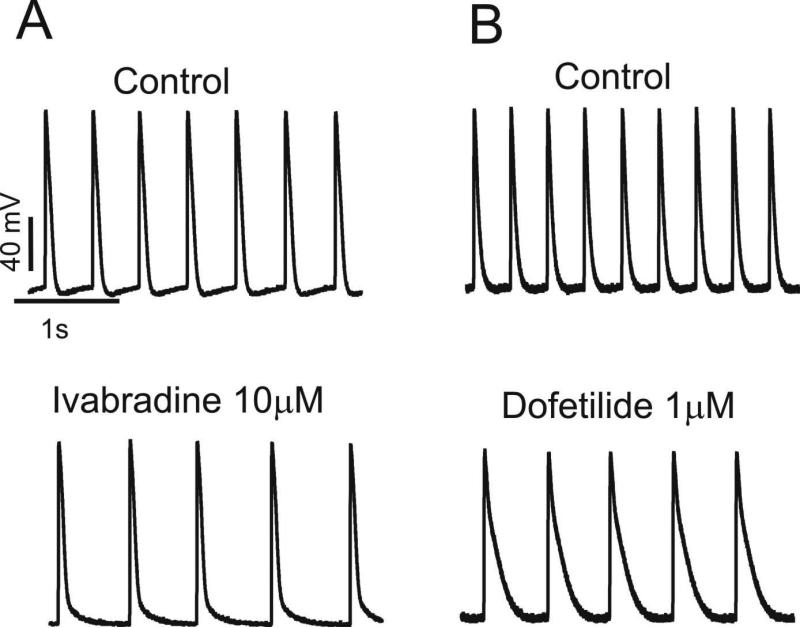

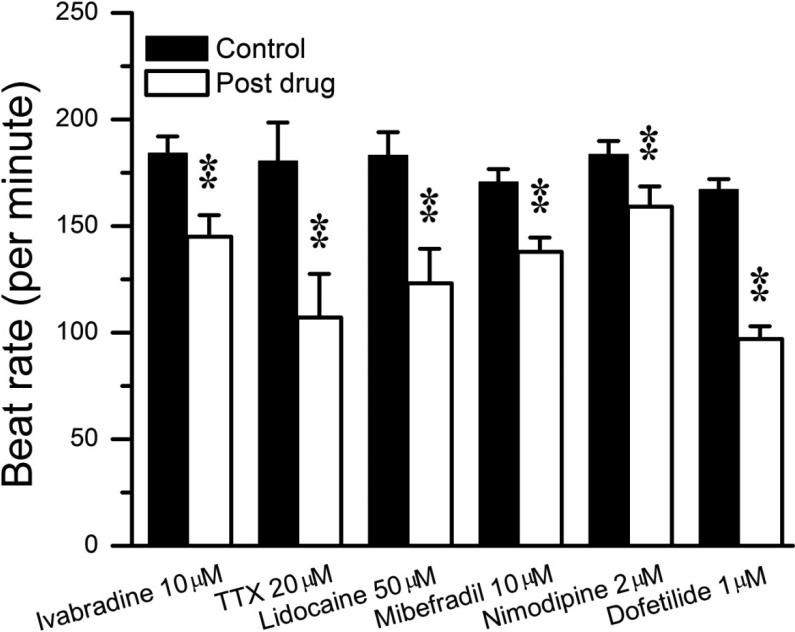

Based on the results shown in Figure 6, selective pharmacologic blockers were employed (as outlined in the Methods) to investigate the role of identified candidate ionic currents in atrial HL-1 cell automaticity. When spontaneously-beating syncytial cells were exposed to the specific If blocker ivabradine, beat rate slowed by 21% (Figure 7A and Table; from 184±8 to 145±10 bpm; P<0.01). Analysis of the recordings revealed that this effect was caused primarily by a significant increase in the diastolic interval, with no effect on APD50 (Table). In addition, there was a change in the action potential morphology from “driver” to “follower”, consistent with a shift in the leading pacemaker site within the electrically-coupled cellular syncytium. This change caused shortening of the DDT (similar to control “follower” cells). These results indicate that, as in SAN cells, If contributes to regulation of atrial HL-1 cell pacemaker activity.

Figure 7. Effects of ivabradine and dofetilide on spontaneous automaticity.

A Spontaneous action potentials were recorded before (top panel) and after (bottom panel) exposure to ivabradine, showing essentially loss of DD with slowing of beat rate for this cell. B Similar data are displayed for dofetilide, which prolonged cycle length by increasing action potential duration.

Tetrodotoxin (TTX) and lidocaine were applied to examine the role of INa on spontaneous automaticity. These Na+ channel blockers caused a modest-substantial reduction in beat rate (Figure 8 and Table; -41% and -33%, respectively). The T-type and L-type Ca++ channel blockers mibefradil and nimodipine had a mild but significant effects to reduce spontaneous atrial HL-1 cell beat rate (Figure 8 and Table; -19% and -13%, respectively). In both cases, this was mediated by slowing of DD, rather than a significant effect on APD.

Figure 8. Effects of blocking inward and outward currents on beat rate in atrial HL-1 cells.

Summary data for beat rate before and following exposure to blockers for If (ivabradine), INa (tetrodotoxin [TTX] and lidocaine), ICa,T (mibefradil), ICa,L (nimodipine), and IKr (dofetilide) are shown (**P<0.01).

Previous electrophysiologic studies have shown that the rapidly-activating delayed rectifier current, IKr, is the major repolarizing outward current in HL-cells.25,26 Inhibition of IKr using the selective blocker dofetilide potently decreased beat rate by 42% (Figures 7B and 8, Table; from 167±5 to 97±6 bpm; P<0.01). However, as expected, the effect was primarily related to prolongation of APD (Table; APD50 and APD100 increased by 134% and 158%, respectively; P<0.01 for both).

DISCUSSION

Although automaticity in cardiac cells has been investigated for decades, the fundamental mechanisms underlying this property have remained controversial.27,28 In spontaneously-beating atrial HL-1 cells, we found that both the RYR receptor inhibitor ryanodine and the SERCA inhibitor thapsigargin slowed automaticity, implying a role for SR Ca++ release in pacemaker activity. Pharmacologic block of multiple candidate sarcolemmal ionic currents also modulated automaticity. Thus, our findings support the concept that both internal and membrane clocks are operative to regulate pacemaker activity in this atrial cell model.

For this investigation, we chose to study HL-1cells because of their phenotypic conservation with mature atrial myocytes, and their reproducible spontaneous contraction under syncytial conditions in culture.11,12,22 Although they are an immortalized cardiac cell line, extensive characterization has shown that atrial HL-1cells are very similar to primary adult atrial myocytes, with expression of mature forms of sarcomeric proteins, atrial granules containing ANP, and typical cardiomyocyte membrane receptors and signaling molecules.11,12 Electrophysiologic properties of AT-1 cells, the lineage from which atrial HL-1 cells are derived, include a variety of typical ionic currents (e.g., INa, ICa,L, and K+ currents), corresponding channel subunits, and electrical coupling through gap junctions.12 We have previously shown that rapid stimulation of atrial HL-1 cells for 24 hr causes shortening of APD and down-regulation of ICa,L.8 This result further supports their phenotypic conservation with adult atrial myocytes, since during AF, rapid stimulation causes remodeling of atrial and pulmonary vein myocytes that increases arrhythmia susceptibility, with a reduction in atrial APD and refractoriness.29-31 Importantly, a particular advantage of this experimental preparation is that beat rate can be assessed in an intact syncytium of cells, thus avoiding exposure to enzyme digestion which could damage membrane proteins (see Experimental Preparation in the Methods).

Over the years, numerous studies have been conducted to investigate the molecular basis for cardiac pacemaker activity. Early theory revolved around the concept that multiple sarcolemmal ion channels functioned together as a membrane “clock” to regulate automaticity, with particular focus on “IK decay”.28 However, the discovery of If attention shifted to this current,32 given that its regional expression and electrophysiologic properties made it an attractive candidate for the “pacemaker current”. However, several lines of evidence have challenged the assumption that If initiates automaticity. Most importantly, pharmacologic and genetic suppression of If causes at most mild-modest slowing of automaticity.28 In SAN cells, If is activated during late repolarization and functions during early-mid DD, modulating beat rate by only up to 20%.14 Genetically-modified mice with either permanent or inducible deletion of HCN isoforms exhibit SAN dysrhythmias, pauses, and/or a depressed response to isoproterenol, but resting heart rate is largely unperturbed.33-35 In humans, oral administration of ivabradine slows heart rate by an average of 6 bpm.36 In atrial HL-1 cells, a previous study demonstrated the presence of If in ~ one-third of cells, composed primarily of HCN1 and HCN2 isoforms.22 Here, we confirmed these results and investigated the sensitivity of If in these cells to the specific blocker ivabradine. With respect to spontaneous automaticity, our results with ivabradine provide additional evidence for involvement of If, with possibly a more dominant role than that observed in SAN cells, given the magnitude of effect that we observed.

More recent studies in SAN cells have spawned a competing theory for the origin of automaticity, namely SR Ca++ release. By combining intracellular Ca++ imaging and electrophysiologic recordings, rhythmic subsarcolemmal Ca++ releases have been identified in late diastole.14 These Ca++ wavelets promote an inward current through Na+-Ca++ exchange to facilitate action potential firing. As in SAN cells, our results support a modulatory role for SR Ca++ release in atrial HL-1 cell automaticity. Both ryanodine and thapsigargin reduced beat rate, albeit these effects were mild-modest. The prominent effect of PKA activation to increase beat rate provides additional evidence for a contribution of SR Ca++ release. While PKA phosphorylates multiple Ca++-handling proteins (including If, L-type Ca++ channels and phospholamban) to enhance SAN cell automaticity, PKA activation has been shown to be obligatory for the occurrence of local SR Ca++ release in pacemaker activity.14,21

Recent data indicate that multiple Na+ channel α-subunit isoforms are involved in regulating pacemaker activity in vivo.27 Moreover, pharmacologic inhibition of Na+ current can reduce heart rate in mice and humans,37,38 and heterozygous SCN5A+/- mice demonstrate bradycardia.39 Our findings in atrial HL-1 cells further support an important role for INa to modulate cardiac pacemaker activity. In addition, the IKr blocker dofetilide also caused potent slowing of atrial HL-1 cell beat rate. These data are not surprising, given that IKr has been shown to be the major repolarizing outward current in atrial HL-1 cells (with detection of mouse ERG40), and dofetilide caused marked APD prolongation. Our findings are consistent with those observed in SAN cells, where “IK decay” remains a major determinant of early DD.14

The action potential upstroke in SAN cells is mediated by ICa,L. Based on activation voltages, inward currents through ICa,T and ICa,L channels also likely contribute to SAN cell pacemaker activity during mid-late and late DD, respectively.14 Genetic inactivation of α1C, α1D, and α1G isoforms has been shown to cause bradycardia in zebrafish and mice.41-43 We and others have identified both L- and T-type Ca++ currents in atrial HL-1 cells,8,44 although their role in automaticity for these cells has not been previously studied. Similar to nodal cells, atrial HL-1 have an unusually high density of T-type Ca++ current, likely mediated by the α1G isoform.45 Our results obtained using mibefradil and nimodipine indicate that ICa,T and ICa,L have relatively mild effects on automatic activity in these cells.

Atrial myocytes that extend into the pulmonary veins are a well-recognized source of rapid ectopic activity that promotes AF. Interestingly, histologic studies reveal evidence for nodal-like cells among pulmonary vein myocytes.46 In addition, like atrial HL-1 cells, T-type Ca++ current is more readily detected in spontaneously-beating pulmonary vein myocytes compared to quiescent cells.3 Evidence to date indicates that multiple mechanisms likely cause rapid ectopic activity in pulmonary vein myocytes, with a probable contribution from enhanced automaticity.4,46 While automaticity has been observed in pulmonary vein myocytes following cell or tissue isolation, this finding has not been consistent, rendering experimentation problematic. For this reason, mechanisms underlying pacemaker activity in pulmonary vein myocytes are presently not well characterized. In preparations that do display spontaneous automaticity, the beat rate is enhanced by interventions that increase intracellular Ca++ concentration, including ouabain and isoproterenol.4,47,48 This is also the case with low concentrations of ryanodine that cause prolonged sub-conductance leak through RYR2 channels.48 As previously shown in SAN cells and in this work for atrial HL-1 cells, these findings are consistent with a modulatory role for SR Ca++ release in pulmonary vein myocyte automaticity.

A limitation of this study is the fact that ion channel blockers cannot precisely isolate the contribution of a specific ion channel complex to the cardiac action potential. While we employed highly-selective blockers at concentrations shown to cause maximal or near-maximal block, other ionic currents may be affected in a non-specific manner. Nevertheless, this approach has proven useful to delineate the complex mechanisms that modulate automaticity in SAN cells. In addition, our data are consistent with the known electrophysiologic features and ionic currents (e.g., the presence of If and ICa,T) that have been characterized in these cells. Another limitation is the fact that whole-cell current data were obtained at room temperature, while action potentials were recorded under more physiologic conditions (i.e., 37°C). It is well recognized that successful voltage control of cardiac Na+ current is difficult to achieve at physiologic and even room temperatures.49,50 As demonstrated in Figure 1, we were able to record satisfactory Na+ currents under our experimental conditions at room temperature. However, this subsequently mandated that all ionic currents be recorded under similar conditions in order to preserve the relative positions of the activation curves shown in Figure 6.

CONCLUSION

In summary, our findings demonstrate a role for both membrane and internal clocks in the generation of spontaneous automaticity in atrial HL-1cells. These clocks likely serve as redundant mechanisms to enable a robust and flexible system to control pacemaker activity. Given that similar mechanisms are operative in SAN cells, and possibly pulmonary vein myocytes, these findings suggest conservation of the molecular mechanisms that generate automaticity in different types of cardiomyocytes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the US Public Health Service (HL55665 and HL071002).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Haissaguerre M, Jais P, Shah DC, Takahashi A, Hocini M, Quiniou G, Garrigue S, Le Mouroux A, Le Metayer P, Clementy J. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:659–666. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809033391003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen YJ, Chen SA, Chen YC, Yeh HI, Chan P, Chang MS, Lin CI. Effects of rapid atrial pacing on the arrhythmogenic activity of single cardiomyocytes from pulmonary veins: implication in initiation of atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2001;104:2849–2854. doi: 10.1161/hc4801.099736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen YC, Chen SA, Chen YJ, Tai CT, Chan P, Lin CI. T-type calcium current in electrical activity of cardiomyocytes isolated from rabbit pulmonary vein. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2004;15:567–571. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2004.03399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wongcharoen W, Chen YC, Chen YJ, Chen SY, Yeh HI, Lin CI, Chen SA. Aging increases pulmonary veins arrhythmogenesis and susceptibility to calcium regulation agents. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:1338–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ehrlich JR, Cha TJ, Zhang L, Chartier D, Melnyk P, Hohnloser SH, Nattel S. Cellular electrophysiology of canine pulmonary vein cardiomyocytes: action potential and ionic current properties. J Physiol. 2003;551:801–813. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.046417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nattel S. Basic electrophysiology of the pulmonary veins and their role in atrial fibrillation: precipitators, perpetuators, and perplexers. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2003;14:1372–1375. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.03445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brundel BJ, Kampinga HH, Henning RH. Calpain inhibition prevents pacing-induced cellular remodeling in a HL-1 myocyte model for atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;62:521–528. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang Z, Shen W, Rottman JN, Wikswo JP, Murray KT. Rapid stimulation causes electrical remodeling in cultured atrial myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;38:299–308. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brundel BJ, Henning RH, Ke L, Van G,I, Crijns HJ, Kampinga HH. Heat shock protein upregulation protects against pacing-induced myolysis in HL-1 atrial myocytes and in human atrial fibrillation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;41:555–562. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brundel BJ, Shiroshita-Takeshita A, Qi X, Yeh YH, Chartier D, Van G,I, Henning RH, Kampinga HH, Nattel S. Induction of heat shock response protects the heart against atrial fibrillation. Circ Res. 2006;99:1394–1402. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000252323.83137.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Claycomb WC, Lanson NA, Jr., Stallworth BS, Egeland DB, Delcarpio JB, Bahinski A, Izzo NJ., Jr HL-1 cells: A cardiac muscle cell line that contracts and retains phenotypic characteristics of the adult cardiomyocyte. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:2979–2984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.White SM, Constantin PE, Claycomb WC. Cardiac physiology at the cellular level: Use of cultured HL-1 cardiomyocytes for studies of cardiac muscle cell structure and function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H823–H829. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00986.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mace LC, Yermalitskaya LV, Yi Y, Yang Z, Morgan AM, Murray KT. Transcriptional remodeling of rapidly stimulated HL-1 atrial myocytes exhibits concordance with human atrial fibrillation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;47:485–492. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maltsev VA, Lakatta EG. Dynamic interactions of an intracellular Ca2+ clock and membrane ion channel clock underlie robust initiation and regulation of cardiac pacemaker function. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;77:274–284. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DiFrancesco D. The role of the funny current in pacemaker activity. Circ Res. 2010;106:434–446. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.208041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bogdanov KY, Vinogradova TM, Lakatta EG. Sinoatrial nodal cell ryanodine receptor and Na+-Ca2+ exchanger: molecular partners in pacemaker regulation. Circ Res. 2001;88:1254–1258. doi: 10.1161/hh1201.092095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bogdanov KY, Maltsev VA, Vinogradova TM, Lyashkov AE, Spurgeon HA, Stern MD, Lakatta EG. Membrane potential fluctuations resulting from submembrane Ca2+ releases in rabbit sinoatrial nodal cells impart an exponential phase to the late diastolic depolarization that controls their chronotropic state. Circ Res. 2006;99:979–987. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000247933.66532.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krafte DS, Volberg WA, Rapp L, Kallen RG, Lalik PH, Ciccarelli RB. Stable expression and functional characterization of a human cardiac Na+ channel gene in mammalian cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1995;27:823–830. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(95)90089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang DW, Nie L, George AL, Jr., Bennett PB. Distinct local anesthetic affinities in Na+ channel subtypes. Biophys J. 1996;70:1700–1708. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79732-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hallaq H, Yang Z, Viswanathan PC, Fukuda K, Shen W, Wang DW, Wells KS, Zhou J, Yi J, Murray KT. Quantitation of protein kinase A-mediated trafficking of cardiac sodium channels in living cells. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;72:250–261. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vinogradova TM, Lyashkov AE, Zhu W, Ruknudin AM, Sirenko S, Yang D, Deo S, Barlow M, Johnson S, Caffrey JL, Zhou YY, Xiao RP, Cheng H, Stern MD, Maltsev VA, Lakatta EG. High basal protein kinase A-dependent phosphorylation drives rhythmic internal Ca2+ store oscillations and spontaneous beating of cardiac pacemaker cells. Circ Res. 2006;98:505–514. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000204575.94040.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sartiani L, Bochet P, Cerbai E, Mugelli A, Fischmeister R. Functional expression of the hyperpolarization-activated, non-selective cation current If in immortalized HL-1 cardiomyocytes. J Physiol. 2002;545:81–92. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.021535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baruscotti M, Barbuti A, Bucchi A. The cardiac pacemaker current. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang T, Roden DM. Regulation of sodium current development in cultured atrial tumor myocytes (AT-1 cells). Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H541–H547. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.2.H541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang T, Wathen MS, Felipe A, Tamkun MM, Snyders DJ, Roden DM. K+ currents and K+ channel mRNA in cultured atrial cardiac myocytes (AT-1 cells). Circ Res. 1994;75:870–878. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.5.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kupershmidt S, Yang IC, Hayashi K, Wei J, Chanthaphaychith S, Petersen CI, Johns DC, George AL, Jr., Roden DM, Balser JR. The IKr drug response is modulated by KCR1 in transfected cardiac and noncardiac cell lines. FASEB J. 2003;17:2263–2265. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1057fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mangoni ME, Nargeot J. Genesis and regulation of the heart automaticity. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:919–982. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lakatta EG, DiFrancesco D. What keeps us ticking: a funny current, a calcium clock, or both? J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;47:157–170. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shinagawa K, Derakhchan K, Nattel S. Pharmacological prevention of atrial tachycardia induced atrial remodeling as a potential therapeutic strategy. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2003;26:752–764. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schoonderwoerd BA, Van G,I, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Van den Berg MP, Crijns HJ. Electrical and structural remodeling: role in the genesis and maintenance of atrial fibrillation. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2005;48:153–168. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rostock T, Steven D, Lutomsky B, Servatius H, Drewitz I, Klemm H, Mullerleile K, Ventura R, Meinertz T, Willems S. Atrial fibrillation begets atrial fibrillation in the pulmonary veins on the impact of atrial fibrillation on the electrophysiological properties of the pulmonary veins in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:2153–2160. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown HF, DiFrancesco D, Noble SJ. How does adrenaline accelerate the heart? Nature. 1979;280:235–236. doi: 10.1038/280235a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Herrmann S, Stieber J, Stockl G, Hofmann F, Ludwig A. HCN4 provides a ‘depolarization reserve’ and is not required for heart rate acceleration in mice. EMBO J. 2007;26:4423–4432. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ludwig A, Budde T, Stieber J, Moosmang S, Wahl C, Holthoff K, Langebartels A, Wotjak C, Munsch T, Zong X, Feil S, Feil R, Lancel M, Chien KR, Konnerth A, Pape HC, Biel M, Hofmann F. Absence epilepsy and sinus dysrhythmia in mice lacking the pacemaker channel HCN2. EMBO J. 2003;22:216–224. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stieber J, Herrmann S, Feil S, Loster J, Feil R, Biel M, Hofmann F, Ludwig A. The hyperpolarization-activated channel HCN4 is required for the generation of pacemaker action potentials in the embryonic heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15235–15240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2434235100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fox K, Ford I, Steg PG, Tendera M, Ferrari R. Ivabradine for patients with stable coronary artery disease and left-ventricular systolic dysfunction (BEAUTIFUL): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:807–816. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baruscotti M, DiFrancesco D, Robinson RB. A TTX-sensitive inward sodium current contributes to spontaneous activity in newborn rabbit sino-atrial node cells. J Physiol. 1996;492(Pt 1):21–30. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lande G, Demolombe S, Bammert A, Moorman A, Charpentier F, Escande D. Transgenic mice overexpressing human KvLQT1 dominant-negative isoform. Part II: Pharmacological profile. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;50:328–334. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00232-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lei M, Goddard C, Liu J, Leoni AL, Royer A, Fung SS, Xiao G, Ma A, Zhang H, Charpentier F, Vandenberg JI, Colledge WH, Grace AA, Huang CL. Sinus node dysfunction following targeted disruption of the murine cardiac sodium channel gene Scn5a. J Physiol. 2005;567:387–400. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.083188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang T, Kupershmidt S, Roden DM. Anti-minK antisense decreases the amplitude of the rapidly activating cardiac delayed rectifier K+ current. Circ Res. 1995;77:1246–1253. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.6.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mangoni ME, Traboulsie A, Leoni AL, Couette B, Marger L, Le QK, Kupfer E, Cohen-Solal A, Vilar J, Shin HS, Escande D, Charpentier F, Nargeot J, Lory P. Bradycardia and slowing of the atrioventricular conduction in mice lacking CaV3.1/alpha1G T-type calcium channels. Circ Res. 2006;98:1422–1430. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000225862.14314.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Platzer J, Engel J, Schrott-Fischer A, Stephan K, Bova S, Chen H, Zheng H, Striessnig J. Congenital deafness and sinoatrial node dysfunction in mice lacking class D L-type Ca2+ channels. Cell. 2000;102:89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rottbauer W, Baker K, Wo ZG, Mohideen MA, Cantiello HF, Fishman MC. Growth and function of the embryonic heart depend upon the cardiac-specific L-type calcium channel alpha1 subunit. Dev Cell. 2001;1:265–275. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xia M, Salata JJ, Figueroa DJ, Lawlor AM, Liang HA, Liu Y, Connolly TM. Functional expression of L- and T-type Ca2+ channels in murine HL-1 cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;36:111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Satin J, Cribbs LL. Identification of a T-type Ca2+ channel isoform in murine atrial myocytes (AT-1 cells). Circ Res. 2000;86:636–642. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.6.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chou CC, Nihei M, Zhou S, Tan A, Kawase A, Macias ES, Fishbein MC, Lin SF, Chen PS. Intracellular calcium dynamics and anisotropic reentry in isolated canine pulmonary veins and left atrium. Circulation. 2005;111:2889–2897. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.498758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wongcharoen W, Chen YC, Chen YJ, Chang CM, Yeh HI, Lin CI, Chen SA. Effects of a Na+/Ca2+ exchanger inhibitor on pulmonary vein electrical activity and ouabain-induced arrhythmogenicity. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;70:497–508. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lo LW, Chen YC, Chen YJ, Wongcharoen W, Lin CI, Chen SA. Calmodulin kinase II inhibition prevents arrhythmic activity induced by alpha and beta adrenergic agonists in rabbit pulmonary veins. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;571:197–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.05.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wendt DJ, Starmer CF, Grant AO. Na channel kinetics remain stable during perforated-patch recordings. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:C1234–C1240. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.263.6.C1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grant AO, Wendt DJ. Block and modulation of cardiac Na+ channels by antiarrhythmic drugs, neurotransmitters and hormones. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1992;13:352–358. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90108-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]