Abstract

Objectives

Assess behaviors of recently HIV-infected men who have sex with men (MSM).

Methods

From 2002–2006 193 recently HIV-infected MSM in the Southern California Acute Infection and Early Disease Research Program were interviewed every 3 months. Changes in HIV status of partners, recent unprotected anal intercourse (UAI), drug use, use of antiretroviral therapy (ART), detectable viral load and partnership dynamics over one year were used to predict recent UAI in a random effect logistic regression.

Results

Over a year significantly fewer partners in the past month were reported (mean 8.81 to 5.84; p<.0001). Percentage of recent UAI with HIV-status unknown last partners decreased from enrollment to 9 months (49% to 27%) and rebounded at 12 months to 71%. In multivariable models controlling for ART use, recent UAI was significantly associated with: baseline methamphetamine use (AOR 7.65, 95% CI 1.87, 31.30), methamphetamine use at follow-up (AOR 14.4, 95% CI 2.02, 103.0), HIV-uninfected partner at follow-up (AOR 0.14, 95% CI 0.06, 0.33) and partners with unknown HIV status at follow-up (AOR 0.33, 95% CI 0.11, 0.94). HIV viral load did not influence rate of UAI.

Conclusions

Transmission behaviors of these recently HIV-infected MSM decreased and serosorting increased after diagnosis; recent UAI with serostatus unknown or negative partners rebounded after nine months, identifying critical timepoints for interventions targeting recently HIV-infected individuals. There was no evidence in this cohort that the viral load of these recently infected men guided their decisions about protected or unprotected anal intercourse.

Keywords: recent HIV infection, post HIVdiagnosis behaviors, HIV positive MSM risk behavior, HIV and substance use

Introduction

Incident HIV infections among men who have sex with men (MSM) in the United States (US) continue to be high 1,2. Individuals with recent or primary HIV infection often participate in risky activities while having high levels of plasma HIV RNA and therefore are highly infectious to others 3–7. Mathematical models of male-to-male sexual transmission of HIV suggest that between 25 and 47% of new infections may be transmitted from those with primary infection 8,9. The latest report from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicates a higher incidence of HIV in the US than previously estimated; with one-third of adults newly diagnosed with a recent infection 10. These studies suggest that early detection of HIV infection and then prevention of unprotected sex among those with recent infection after is likely to be an important component of efforts to control the MSM HIV epidemic in the US.

Our previous research on recently HIV-infected MSM revealed a wide variation in the types of partnerships reported following diagnosis 11, as well as changes in both the number of partner types and risk behaviors practiced with different types of partners12. These findings were limited to the first three months following diagnosis with recent infection. Other research indicates that behavior varies by partner type; more HIV-infected MSM report unprotected anal intercourse (UAI) in stable or main partnerships than in shorter term or less intimate partnerships13–15,16 although the evidence is mixed17. Nevertheless, more than half of transmissions among MSM in the US were estimated to be between main partners 18. Higher transmission of HIV within main partnerships has also been observed among MSM in Europe 19 and more recently among women in Africa 20. However, HIV-infected MSM do appear to adjust their behaviors by the HIV status of their partners; fewer report UAI with sero-discordant than sero-concordant partners reported to be “regular partners” 21. The pattern is less clear for partners referred to as ”non-regular partners”.

Driving HIV transmission among MSM in the US is the interplay between drug use and sexual behavior. Before sex, drug use can diminish the correlation between intimacy and risk behavior within couples, suggesting that drug use affects relationship dynamics 22. Drug intoxication affects individual’s abilities to negotiate and correctly use condoms. In fact, some MSM report using drugs in sexual settings specifically to be able to disregard concerns about HIV transmission23. Among MSM, reported use of stimulants have been associated with incident HIV infection24 and those who report using stimulants during sex are more likely to report high risk behaviors such as UAI25–27. While fewer methamphetamine-using HIV-infected men have reported UAI with HIV-uninfected partners, more reported UAI if the HIV-uninfected or status unknown partners were anonymous partners28.

In Southern California in particular, use of methamphetamine has been demonstrated to be a significant factor driving continuing transmission of HIV among MSM29. Our earlier work demonstrated the association between methamphetamine use, high risk behavior and the acquisition of HIV in this cohort30,31. While it is known how drug use influences HIV acquisition, the role drug use plays in behavior of HIV-infected men who know their status and the status of their partners is less clear.

There has been limited research examining the sexual behaviors and drug use of individuals recently-infected with HIV 30,32,33. We analyzed sexual behaviors and partnering patterns in a cohort of MSM with recent HIV infection during their first year following diagnosis to determine the effects of partner type, partnership stability, partner charactersitics, including serostatus, and drug use on the reported practice of transmission-associated behaviors such as UAI.

Methods

The Southern California Acute Infection and Early Disease Research Program (SC-AIEDRP) recruited, enrolled, and collected biological data on a cohort of recently HIV-infected individuals (infection within the past 12 months), as previously described18;19,34. Between 2002 and 2006, 225 HIV-infected MSM completed baseline questionnaires to assess HIV risk behavior by computer-assisted self- interview (CASI). The men were offered interviews every 3 months in their first year enrolled in the AIEDRP cohort. As previously reported, in this cohort date of infection was estimated from last HIV-negative test result and serology and was a mean of 13weeks (median, 14 weeks) before the baseline study questionnaire was completed; date of HIV diagnosis was established through review of medical records and assigned as the first positive HIV test that was reported to the participant and was a mean of 5 weeks (median, 3 weeks) before the baseline questionnaire was completed31. The results reported in this analysis reflect behavior changes from the date of enrollment, when detailed behavioral data were collected in the baseline questionnaire.

Detailed questions were asked at baseline about last three sexual partners and at follow-up interviews only on the last partner. At all timepoints men were asked to also report in detail about a main partner (if they had one), if he was not reported as a last partner (follow-up), or one of the last three partners (baseline). Information included partner characteristics, types of sexual activity, types of substances used just prior to and during sexual activity at last sex, and types of substances ever used with that partner for baseline, in the last three months and at all follow-up interviews. “Persistent partners” were those partners reported on in a previous interview ascertained in response to a direct question about each reported partner “is this a partner you told us about before” and collection of initials for each partner.

A scale that summarizes the intimacy level of partnerships specific to MSM called the “Partnerships Assessment Scale” (PAS) 35 was included and found to be highly reliable with a Cronbach’s Alpha of >0.94 for each partner type at baseline and during follow-up. PAS is generated by adding 27 binary variables resulting in a minimum score of 0 and maximum of 27. The questions ask about amount and type of contact, knowledge about partner’s life, and social activities conducted with each partner and are assigned a value for each activity with the final score representing a sum of these items. The PAS was analyzed as a continuous variable for associations with risk behavior. We also assessed changes over time in types of partners reported, numbers of partners, and drug use.

Follow-up behavioral data was available for analysis on 193 men and their reports on 1,011 partners during the year following enrollment in the study. Not all data is available for all 1,011 reported partners due to participants skipping questions (i.e. refuse to answer); missing data was not imputed. We compared those who completed only a baseline interview (n=225 provided complete data) to those who completed at least one follow-up interview (n=193) and found the only statistically significant differences were there were more men of “other” ethnicity who reported UAI at baseline and dropped out than who continued. There were no differences within the 193 men by demographic characteristics or risk behaviors including practice of UAI, use of methamphetamines, and numbers of partners between those who stayed in the study for 12 months (n=55) and those who remained for less than 12 months (n=135). Among those completing a baseline and at least one follow-up interview, 597 baseline partners were reported and 414 partners were reported at 3 months or more post-diagnosis; over 98% of reported partners were male. At each follow-up, there were fewer respondents and they provided complete information on fewer partners (Table 1). A total of 562 interviews were collected from a median of 2 follow-up visits. The participants’ viral load and use of antiretroviral therapy (ART) at each visit was acquired from the clinical record of the visit on the date of the behavioral interview (or the most recent prior clinical visit) and was available for 187 of the 193 individuals at baseline and for 554 visit.

Table 1.

Characteristics, behaviors, use of HAART and viral load at each time period.

| Overall | Baseline | Month 3 | Month 6 | Month 9 | Month 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Participants | 193 | 193 | 121 | 106 | 85 | 55 |

| Number of Partners | 1011 | 597 | 133 | 119 | 99 | 63 |

| Reported Partner(s) with recent UAI | 169/356 (47.5%) | 86/187 (46.0%) | 22/42 (52.4%) | 25/51 (49%) | 16/41 (39%) | 20/35 (57.1%) |

| Methamphetamine use at last sex w/partner(s)*** | 163/773 (21.1%) | 120/403 (29.8%) | 14/125 (11.2%)†† | 16/109 (14.7%)† | 8/86 (9.3%)†† | 5/50 (10.0%)† |

| Participants with Detectable Viral Load*** | 450/554 (81.2%) | 184/187 (98.4%) | 103/121 (85.1%)††† | 81/106 (76.4%)††† | 49/85 (57.7%)††† | 33/55 (60.0%)††† |

| Participants currently on HAART*** | 179/554 (32%) | 27/187 (14.4%) | 47/121 (38.8%)††† | 35/106 (33.0%)††† | 43/85 (50.6%)††† | 27/55 (49.1%)††† |

| Reported HIV Infected Partner(s)*** | 213/928 (23.0%) | 72/526 (13.7%) | 44/132 (33.3%)††† | 45/117 (38.5%)††† | 30/97 (30.9%)††† | 22/57 (38.6%)††† |

| Reported HIV Uninfected Partner(s) | 378/928 (41%) | 231/526 (44%) | 47/132 (36%) | 41/117 (35%) | 39/97 (40%) | 20/57 (35%) |

| Mean(SD) PAS for partners: | ||||||

| all partners*** | 12.4(8.3) | 10.3(8.4) | 14.6(8.3)††† | 16.6(8.2)††† | 14.5(8.8)††† | 15.9(9.2)††† |

| reporting no UAI | 15.2(8.0) | 14.3(8.2) | 15.7(7.1) | 17.5(6.9) | 15.9(8.0) | 15.4(9.6) |

| reporting UAI* | 17.0(7.8) | 15.4(7.7) | 16.6(7.6) | 20.3(7.0)†† | 18.3(8.5) | 19.0(7.4) |

| with no reported methamphetamine use*** | 13.1(8.8) | 10.7(8.6) | 14.3(8.1)††† | 17.0(8.0)††† | 14.4(8.9)†† | 15.3(9.1)†† |

| with reported methamphetamine use** | 8.2(7.8) | 6.6(6.7) | 14.0(8.9)†† | 12.3(9.3)† | 12.5(8.9)† | 9.00(10.6) |

| that are HIV-uninfected*** | 15.8(8.1) | 13.5(8.0) | 19.3(6.0)††† | 21.6(5.1)††† | 17.2(7.7)†† | 19.4(8.4)†† |

| that are HIV-infected** | 16.4(7.6) | 13.7(8.0) | 16.9(6.6)† | 17.8(7.2)†† | 18.0(7.8)† | 18.7(7.0)† |

| with unknown HIV status | 6.8(7.0) | 6.4(7.1) | 7.07(6.4) | 8.16(6.4) | 7.11(6.8) | 8.27(8.3) |

Significant linear trend .05*, .01**, <.0001***

Significantly different from baseline value: .05†, .01††, <.0001†††

Analyses were conducted using generalized linear random effects models to account for the correlation among reports from the same individual over time. A random effects logistic regression of reported recent UAI with separate but correlated random effects for baseline and for follow-up was used to assess the association with individual and partner characteristics including PAS, types of partners reported, methamphetamine use, and use of ART. Numbers of partners reported was not significant in bivariate analysis and not included in the final model. As viral load and use of ART are highly correlated, only use of ART was included in the model as it represented the behavioral aspect of medication. Models were fit using SAS Proc Glimmix (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

The men in this cohort had a mean age of 35 years (range at baseline of 19–64), were mostly white (71%) and Hispanic (21%) and were highly educated (88% had at least some college education). They reported a mean of 8.8 partners in the last 3 months at baseline (range 0–30, median 4). Twenty two percent (n=42) had a main partner at baseline but did not report a continuing partner in any follow-up interviews; 29% (n=56) had a main partner at baseline and reported at least one continuing partner in at least one follow-up interview; 32% (n=62) had neither a main partner at baseline nor any main partner reported in a follow-up interview, and 17% (n=33) did not have a main partner at baseline but reported a new main partner in at least one follow-up interview. During the year of follow-up only 3 men reported abstinence in the three months prior to the interview and none reported abstinence at more than one visit or for the duration of the study.

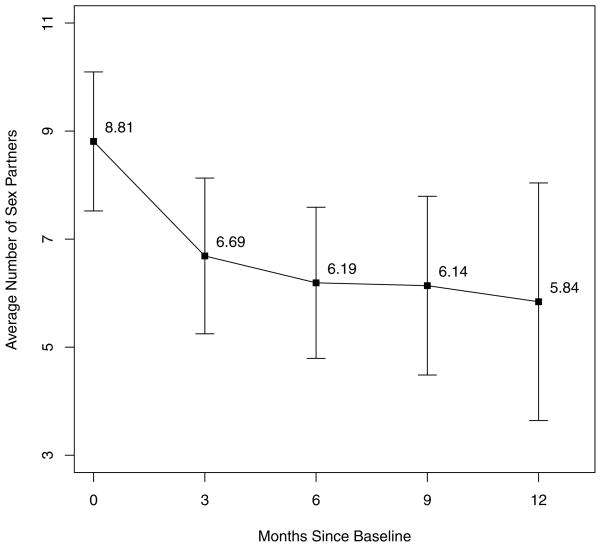

Over the year following diagnosis there was a significant decrease in the numbers of partners reported in the past month from 8.81 to 5.84 mean partners (p < .0001) when time since baseline interview was analyzed as a continuous variable. When time since baseline interview was rounded to the nearest three months (Figure 1), the most significant drop in number of sex partners was shown to occur from baseline to 3 months (Rate Ratio (RR) 0.71, p<.0001, 95%CI 0.65–0.78). Further changes were not significant but showed decreasing trends through month 9: RR 0.97 (95%CI 0.86–1.10) from months 3 to 6, RR 0.88 (95%CI 0.76, 1.02) from months 6 to 9, and RR 1.17 (95%CI 0.98–1.39) from months 9 to 12. Overall a significant decrease of 27% (95%CI 20–32%) was detected from baseline to follow-up in the number of partners reported in the last three months (p=.0005)

Figure 1.

Mean numbers of partners reported in the prior three months over the year following HIV diagnosis:error bars are 95% confidence bounds on the means

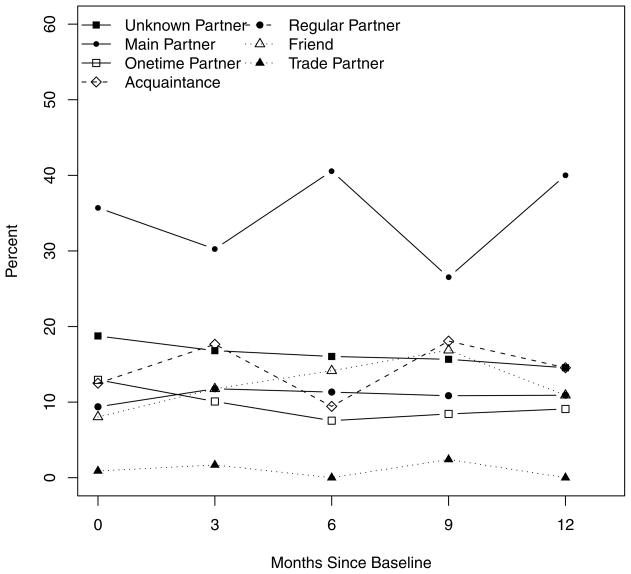

Over the year, more men reported their last partner was a main partner than any other partner type, followed by unknown partners (Figure 2). The percent of men who reported any main partner significantly increased from 20.4% to 47.6% (p<.0001); unknown and one time partners decreased over time (p=.0014 and .0004, respectively). The largest increase in number of MSM reporting main partners occurred between baseline and 3 months (p=.0002), the differences between other consecutive visits were not significant, however, the difference from baseline to follow-up was significant (OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.68, 0.80). Main partners were most frequently the last partner and the proportion of these increased slightly over the year. The percent of last partners who were unknown or anonymous partners decreased slightly over time (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage of HIV positive, negative and unknown status partners of recently infected MSM with whom with they reported recent unprotected anal intercourse: across the first year following HIV diagnosis

Over the year of follow-up, participants reported the HIV status of their partners. Among the 252 main partners with HIV status reported, more than half were reported to be HIV uninfected (56%), a third as HIV positive, and the fewest as HIV status unknown (11%). Among the 646 non-main partners with HIV status reported, about a third were reported as HIV uninfected, almost 20% as HIV positive and almost half reported that they did not know the HIV status of these partners (47%). Overall the percent reporting the use of methamphetamines during last sex decreased, yet UAI increased among those that did report methamphetamine use (Table 1).

During follow-up interviews condom use during anal intercourse with last partner was reported for 414 partners. More men reported not using condoms (i.e. UAI) with an HIV-infected partner at any time point than reported UAI with either an uninfected or status unknown partner. For those reporting UAI with HIV-uninfected partners, there was more UAI with main versus non-main HIV-uninfected partners, with a slight trend toward less UAI; 94% at baseline to 90% at one year versus 62% at baseline to 55% at one year, respectively, For UAI with HIV-uninfected main partners the pattern was the same, 67% at baseline to 64% at one year for main partners and 54% to 38% for non-main partners. For those with partners of unknown HIV status, there were too few reporting main partners to report a trend. UAI with non-main partners of unknown HIV status decreased until 9 months when it increased, 51% at baseline to 40% at 9 months and then 67% at 12 months.

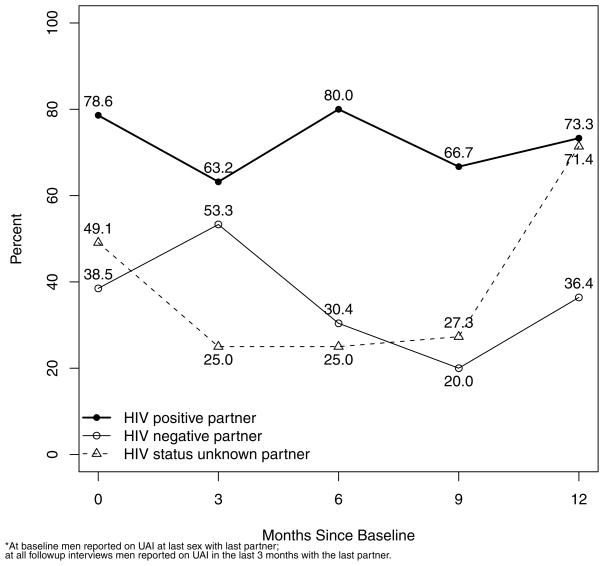

When UAI with last partner was assessed by HIV status of partner the percent reporting UAI at last sex at baseline or since last interview at follow-up with a partner who was HIV-uninfected or unknown with that partner decreased from 42% at baseline to 29% at 6 months, 23% at 9 months but then rebounded at 12 months to 50% (Figure 3). It should be noted that by month 12, UAI was entirely with HIV status unknown partners and none reported with HIV-uninfected partners.

Figure 3.

Percentage of last partners of each partner type reported by MSM with recent HIV infection over the first year following diagnosis

The PAS was administered to provide a quantitative measure of the amount of intimacy within a partnership for each category of partnership asked about. Overall the mean PAS was 12.4 and increased from 10.3 at baseline to 15.9 at one year (Table 1). The minimum, maximum, and mean for main partners were 0, 27, and 22.3, respectively. PAS was significantly lower for those that use methamphetamine with their partner than for non-users (mean PAS of 8.1 vs. 13.1; p<.001). 36. A higher PAS was associated with increased odds of disclosure to the partner of HIV status both at baseline (OR 1.16, 95% CI 1.13, 1.20) and follow-up (OR 1.19, 95% CI 1.12, 1.27).

At baseline almost all participants (98%) had detectable viral load and only 14% had initiated ART. At each timepoint, there was a significant increase in the proportion of those on therapy and without detectable viral load reaching at 12 months 60% remaining with detectable viral load and about half on therapy (Table 1). Over the year 55% (107/193) of individuals never took ART, 13% (26/193) were on ART continuously at every visit at any time point and 99% (192) of individuals had a detectable viral load at any time point. In univariate analysis, there was no significant difference in reports of UAI between those without and with detectable viral load (43.9% of those with no detectable vs. 47.9% of those with a detectable viral load, p-value =.62). Similarly, there was no difference in those reporting UAI by ART usage (49.6% of those not on ART reported UAI vs. 40.2% of those on ART, p=.14).

Based on multivariable analysis over the year following HIV diagnosis, the following were significantly associated with reported UAI: baseline methamphetamine use (AOR 7.65, 95% CI 1.87, 31.30), methamphetamine use at follow-up (AOR 14.4, 95% CI 202, 103.0), HIV-uninfected partner at follow-up (AOR 0.14, 95% CI 0.06, 0.33) and partners with unknown HIV status at follow-up (AOR0.33, 95% CI 0.11, 0.94). PAS score during the year was marginally not significant (AOR 1.04, 95% CI 0.99, 1.09); race/ethnicity and use of ART were not significant.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate how sexual behaviors, partnership status, substance use and partner choices of MSM with recent HIV infection change during the first year following diagnosis. In this cohort, men with recent HIV infection reduced their total number of partners over the first year of infection; with the greatest decrease in the first six months and afterwards declines were minimal although significantly less than baseline. We identify a rebound in unprotected sex with serodiscordant or unknown partners at one year, suggesting that risk reduction in transmission behaviors is not sustained after a year. This replicates an earlier report of such a rebound in risk behavior among a smaller sample of men who seroconverted to HIV in a five city study conducted 1995–98 as the HIVNET Vaccine Preparedness Study 33. Together, these studies suggest little progress in behavioral risk reduction for men new diagnosed with HIV. Moreover, while the change in numbers of partners we report was significant, even with the decrease these recently HIV-infected men still had quite a few partners every few months, most of whom were new partners and over half whose HIV status was negative or unknown during that year. Thus, there is the potential for HIV transmission occurring to many different men during the course of that first year.

Our findings highlight the importance of the first six months after diagnosis as a time when behavior change occurs. It also suggests a need for programs to support the maintenance of such changes after this window of opportunity and particularly after 9 months of follow-up. The choices made by these potentially highly infectious men about the type of sex they practice and with whom they practice it affects their likelihood of transmitting to others. While most of our findings reflect the analysis at the partner level to account for individual differences in behavior across different partners, the level of UAI reported at the individual level in Table 1 (46% baseline and 57% at 12 months)37 is comparable at baseline but higher after a year to that found in a meta-analysis of HIV positive men in the United States. Because our cohort became too small after a year to follow, we cannot tell if this increase in risk is short term or if this reflects recent increases in risk behavior among HIV positive men since 2000 as noted in the review.

The methamphetamine use reported in this sample is of great concern. At baseline, just over one third of the men reported using methamphetamine with a partner at last sex and continually during the year of follow-up with the percentage remaining remarkably stable. For HIV-infected men this suggests that they are not accessing adequate treatment for substance use, illustrating the need for better treatment and services for this problem amongst HIV-infected men. It further highlights the continuing failure in secondary prevention efforts due to the nexus of drug use and HIV risk as the association between methamphetamine use and risky sex has been clearly demonstrated 38–41. These persistently high levels of methamphetamine use are also of particular concern for this population of men with recent HIV infection, as drug use has been shown to be associated with poor adherence to HIV treatment 42,43. The finding that the percent reporting UAI did not diminish significantly over time among methamphetamine users was not surprising but lends support to the urgent need to develop better access to, higher treatment adoption, and more effective substance use treatment for those with HIV.

Overall the partnerships of these recently HIV-infected MSM seemed to stabilize and become stronger (i.e. more intimate as measured by PAS) over the year following HIV diagnosis. Being in a stable partnership has been shown to enhance adherence to medication 22; a potentially important health benefit for men with HIV infection with partnerships. On the other hand, it has previously been shown that those with low intimacy partners are less likely to disclose their HIV status 36. Consistent with this was the significant association between PAS and disclosure we identified both at baseline and follow-up. This suggests that risk reduction interventions for men in non-regular partnerships must address the dynamics of their partnerships to prevent potential transmission. Finally, we also find evidence of sero-sorting among these newly HIV infected men, as the percent of men reporting an HIV-infected partner increased over time, from 14% at baseline to 39% at 12 months.

Although presence of a detectable viral load decreased significantly over the year and use of antiretroviral therapy increased significantly for the men in this cohort, neither had an effect on the reported transmission behaviors. Evidence is growing that use of ART can greatly reduce HIV infectiousness and transmission risk44,45 and some HIV positive men have been reported to increase risk behavior after initiation of ART and establishment of low viral load46, suggesting they may be “compensating” in risk for their reduced infectiousness. However, a recent review of the literature suggests an overall lack of effect of ART use on behavior37; providing support for our findings.

There are limitations to the generalizability of our findings. The culture and specific characteristics of the Southern Californian HIV epidemic may result in different substance use and partnership patterns among those with recent HIV infection than in other locations in the US and internationally. The study also was located at large academic research centers and included those willing to participate in a research study; therefore enrolled individuals may not be entirely representative of those who acquire HIV and are followed in other settings. Additionally, the men in this study were largely White, highly educated, and there were few men less than 30 years of age. If the sample was more diverse, it is possible that we may have observed different changes in partnering patterns. The design of the study questionnaire presented challenges to identifying “the” partnership over time, as we did not collect actual names in order to protect the partner’s identity; instead we collected nicknames or initials and these proved not to be used consistently by respondents. Nevertheless, it was possible to identify which behaviors occur with previously reported partners which were labeled as “persistent partnerships” for the purpose of the analyses. In addition, assumptions about potential transmission to sexual partners is limited by HIV status of partners being based upon participants’ reports, and not otherwise validated. The behavioral data were not linked with changes in the clinical status and medication use of the men over time, analyses which could provide greater insight into the influences on behavior change. Finally, while the loss to follow-up was substantial, there were no significant differences between those who remained on study for 12 months and those who dropped out. It is important to note that the behavioral data were collected as part of an ancillary study to a large clinical study and there were minimal incentives offered to complete behavioral interviews and no intensive retention efforts for behavioral follow-up. Clearly, future cohorts studies need to invest resources and special effort into retention of people with recent HIV infection. These limitations are offset by the uniqueness of having longitudinal data over one year on partnering patterns from a relatively large sample of men with recent HIV infection.

This study contributes unique perspectives about the risk behaviors and sexual partnering patterns of recently HIV-infected MSM. Interventions for such men around the time of diagnosis that address substance use may have great implications for their health status and the course of the HIV epidemic. It is sobering that our findings mirror those of a cohort collected five years previously 33, showing that progress has not been made in changing the transmission behaviors of men after HIV infection. A significant reduction in the numbers of partners and although a rebound in risk, less unprotected anal intercourse with known serodiscordant partners than at baseline; such changes may have an important impact on HIV transmission rates as noted in a review of HIV prevention interventions.

Finally, our findings point to decreases in risk behavior in the months following a diagnosis, and then a rebound in risk behaviors after 9 months, perhaps defining timepoints for ongoing interventions that target risk reduction for HIV-infected individuals.

Table 2.

Odds Ratios and 95% CI for covariates in a multiple logistic random effects model on the reporting of recent UAI with the last or previous partner (n=187 individuals with 228 observations from 195 visits)

| 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR | Lower | Upper |

| Baseline Intercept† | 0.89 | 0.17 | 4.68 |

| Follow-up Intercept† | 0.7 | 0.15 | 3.29 |

| Baseline Methamphetamine use** | 7.65 | 1.87 | 31.3 |

| Follow-up Methamphetamine use** | 14.4 | 2.02 | 103 |

| Partner HIV uninfected*** | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.33 |

| Partner HIV status unknown* | 0.33 | 0.11 | 0.94 |

| Partner HIV infected (reference) | - | - | - |

| PAS | 1.03 | 0.98 | 1.09 |

| Hispanic | 2.6 | 0.86 | 1.83 |

| Other | 0.33 | 0.06 | 1.96 |

| White (reference) | - | - | - |

| Currently taking ARV medication | 0.66 | 0.28 | 1.54 |

significant at .05,

significant at .01,

significant at .001

Baseline intercept is an indicator of the initial visit, Follow-up intercept is an indicator of any visit after baseline.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH/NIAID U01 AI43638 and UARP (CHRP) ID01-SDSU-056.

References

- 1.van Griensven F, de Lind van Wijngaarden JW, Baral S, AG The global epidemic of HIV infection among men who have sex with men. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2009;4:300–7. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32832c3bb3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sullivan PS, Hamouda O, Delpech V, et al. Reemergence of the HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men in North America, Western Europe, and Australia, 1996–2005. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:423–31. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wawer MJ, Gray RH, Sewankambo NK, et al. Rates of HIV-1 transmission per coital act, by stage of HIV-1 infection, in Rakai, Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1403–9. doi: 10.1086/429411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fiebig EW, Wright DJ, Rawal BD, et al. Dynamics of HIV viremia and antibody seroconversion in plasma donors: implications for diagnosis and staging of primary HIV infection. Aids. 2003;17:1871–9. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200309050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pilcher CD, Tien HC, Eron JJ, Jr, et al. Brief but efficient: acute HIV infection and the sexual transmission of HIV. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:1785–92. doi: 10.1086/386333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hollingsworth TD, Anderson RM, Fraser C. HIV-1 transmission, by stage of infection. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:687–93. doi: 10.1086/590501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brenner BG, Roger M, Routy JP, et al. High Rates of Forward Transmission Events after Acute/Early HIV-1 Infection. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:951–9. doi: 10.1086/512088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koopman JS, Jacquez JA, Welch GW, et al. The role of early HIV infection in the spread of HIV through populations. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1997;14:249–58. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199703010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacquez JA, Koopman JS, Simon CP, Longini IM., Jr Role of the primary infection in epidemics of HIV infection in gay cohorts. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1994;7:1169–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.CDC. Trends in HIV/AIDS Diagnoses Among Men Who Have Sex With Men-33 States, 2001–2006. JAMA. 2008;300:497–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorbach PM, Holmes KK. Transmission of STIs/HIV at the partnership level: beyond individual-level analyses. J Urban Health. 2003;80:iii15–25. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorbach PM, Drumright LN, Daar ES, Little SJ. Transmission behaviors of recently HIV infected men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42:80–5. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000196665.78497.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Semple SJ, Patterson TL, Grant I. HIV-positive gay and bisexual men: predictors of unsafe sex. AIDS Care. 2003;15:3–15. doi: 10.1080/713990434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hays RB, Kegeles SM, Coates TJ. Unprotected sex and HIV risk taking among young gay men within boyfriend relationships. AIDS Educ Prev. 1997;9:314–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gross M, Buchbinder SP, Celum C, Heagerty P, Seage GR., 3rd Rectal microbicides for U.S. gay men. Are clinical trials needed? Are they feasible? HIVNET Vaccine Preparedness Study Protocol Team. Sex Transm Dis. 1998;25:296–302. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199807000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brooks R, Rotheram-Borus M, Bing E, et al. HIV and AIDS among men of color who have sex with men and men of color who have sex with men and women: an epidemiological profile. AIDS Educ Prev. 2003;15:1–6. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.1.5.1.23607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Kesteren NM, Hospers HJ, Kok G. Sexual risk behavior among HIV-positive men who have sex with men: a literature review. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;65:5–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sullivan PS, Salazar L, Buchbinder S, Sanchez TH. Estimating the proportion of HIV transmissions from main sex partners among men who have sex with men in five US cities. AIDS. 2009:23. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832baa34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davidovich U, de Wit J, Albrecht N, et al. Increase in the share of steady partners as a source of HIV infection: a 17–year study of seroconversion among gay men. AIDS. 2001;15:1303–8. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200107060-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunkle KL, Stephenson R, Karita E, et al. New heterosexually transmitted HIV infections in married or cohabiting couples in urban Zambia and Rwanda: an analysis of survey and clinical data. Lancet. 2008;371:2183–91. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60953-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bouhnik AD, Préau M, Schiltz MA, et al. Unprotected sex in regular partnerships among homosexual men living with HIV: a comparison between sero-nonconcordant and seroconcordant couples (ANRS-EN12-VESPA Study) AIDS. 2007;21:S43–8. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000255084.69846.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Theodore P, Duran R, Antoni M, Fernandez M. Intimacy and sexual behavior among HIV-positive men-who-have-sex-with-men in primary relationships. AIDS and Behavior. 2004;8:321–31. doi: 10.1023/B:AIBE.0000044079.37158.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKirnan D, Ostrow D, Hope B. Sex, drugs, and escape: a psychological model of HIV-risk sexual behaviours. AIDS Care. 1996;8:655–69. doi: 10.1080/09540129650125371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plankey MW, Ostrow DG, Stall R, et al. The relationship between methamphetamine and popper use and risk of HIV seroconversion in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45:85–92. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3180417c99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colfax G, Coates TJ, Husnik MJ, et al. Longitudinal patterns of methamphetamine, popper (amyl nitrite), and cocaine use and high-risk sexual behavior among a cohort of San Francisco men who have sex with men. J Urban Health. 2005;82:i62–70. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colfax G, Vittinghoff E, Husnik MJ, et al. Substance use and sexual risk: a participant-and episode-level analysis among a cohort of men who have sex with men. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:1002–12. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drumright LN, Little SJ, Strathdee SA, et al. Unprotected anal intercourse and substance use among men who have sex with men with recent HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:344–50. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000230530.02212.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Semple SJ, Zians J, Grant I, Patterson TL. Sexual risk behavior of HIV-positive methamphetamine-using men who have sex with men: the role of partner serostatus and partner type. Arch Sex Behav. 2006;35:461–71. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colfax G, Shoptaw S. The methamphetamine epidemic: Implications for HIV prevention and treatment. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2005;2:194–9. doi: 10.1007/s11904-005-0016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drumright LN, Little SJ, Strathdee SA, et al. Unprotected anal intercourse and substance use among men who have sex with men with recent HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:344–50. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000230530.02212.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drumright LN, Strathdee SA, Little SJ, et al. Unprotected anal intercourse and substance use before and after HIV diagnosis among recently HIV-infected men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:401–7. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000245959.18612.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen SY, Gibson S, Weide D, McFarland W. Unprotected Anal Intercourse Between Potentially HIV-Serodiscordant Men Who Have Sex With Men, San Fransciso. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33:166–70. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200306010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colfax GN, Buchbinder SP, Cornelisse PG, Vittinghoff E, Mayer K, Celum C. Sexual risk behaviors and implications for secondary HIV transmission during and after HIV seroconversion. AIDS. 2002;16:1529–35. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200207260-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gorbach PM, Drumright LN, Javanbakht M, et al. Antiretroviral drug resistance and risk behavior among recently HIV-infected men who have sex with men (MSM) J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47:639–43. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181684c3d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson AM, Copas A, Field J, et al. Do computerised self-completion interviews influence the reporting of sexual behaviours? A methodological experiment. Thirteenth Meeting of the International Society for Sexually Transmitted Diseases Research; 1999 July 11–14; Denver Colorado. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gorbach PM, Galea JT, Amani B, et al. Don’t ask, don’t tell: patterns of HIV disclosure among HIV positive men who have sex with men with recent STI practising high risk behaviour in Los Angeles and Seattle. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80:512–7. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.010918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crepaz N, Marks G, Liau A, et al. Prevalence of unprotected anal intercourse among HIV-diagnosed MSM in the United States: a meta-analysis. AIDS. 2009;23:1617–29. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832effae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Colfax G, Coates TJ, Husnik MJ, et al. Longitudinal patterns of methamphetamine, popper (amyl nitrite), and cocaine use and high-risk sexual behavior among a cohort of san francisco men who have sex with men. J Urban Health. 2005;82:i62–70. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Colfax G, Vittinghoff E, Husnik MJ, et al. Substance use and sexual risk: a participant-and episode-level analysis among a cohort of men who have sex with men. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:1002–12. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ober A, Shoptaw S, Wang PC, Gorbach P, REW Factors associated with event-level stimulant use during sex in a sample of older, low-income men who have sex with men in Los Angeles. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;102:123–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Methamphetamine use and HIV risk behaviors among heterosexual men-preliminary results from five northern California counties, December 2001-November 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:273–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marquez C, Mitchell SJ, Hare CB, John M, Klausner JD. Methamphetamine use, sexual activity, patient-provider communication, and medication adherence among HIV-infected patients in care, San Francisco 2004–2006. AIDS Care. 2009;21:575–82. doi: 10.1080/09540120802385579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hinkin CH, Barclay TR, Castellon SA, et al. Drug use and medication adherence among HIV–1 infected individuals. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:185–94. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9152-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Donnell D, Baeten JM, Kiarie J, et al. Heterosexual HIV-1 transmission after initiation of antiretroviral therapy: a prospective cohort analysis. Lancet. 2010;12:9731. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60705-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fisher M, Pao D, Brown AE, et al. Determinants of HIV-1 transmission in men who have sex with men: a combined clinical, epidemiological and phylogenetic approach. AIDS. 2010;24:1739–47. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833ac9e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stolte G, De Wit JBF, Van Eeden A, Coutinho RA, Dukers NHTM. Perceived viral load, but not actual HIV-1-RNA load, is associated with sexual risk behaviour among HIV-infected homosexual men. AIDS. 2004;18:1943–9. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200409240-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]